WINTER 2021 JUXTAPOZ

126 4 64MB

English Pages [148] Year 2021

Recommend Papers

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

Amani Lewis

Mr. StarCity Brian Calvin

Brother Vellies

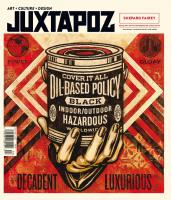

WINTER 2021, n216 USA $9.99 / CAN $10.99 DISPLAY UNTIL MARCH 1, 2021

©2020 Vans, Inc.

CONTENTS

Winter 2021 ISSUE 216

34

134

Darien Birks Makes the Leap

10

38

San Francisco, Brooklyn, San Jose, Toledo, Amsterdam

Editor's Letter

14

Studio Time Ania Hobson’s Interrogation Room

18

The Report Troy Lamarr Chew II’s Award Tour

24

Design

Fashion Brother Vellies Primed for the Pledge

110

Maria Qamar

48

Travel Insider Lowe Mill ARTS in Huntsville, Alabama

A Beautiful Monolith at SCAD

136

Sieben on Life A Six Pack with Scott Bourne

138

Pop Life

Confetti in Cancún with Ana Leovy

Globe x Pantone Colors, ONLY and MadHappy

Steven Sweatpants Defined 2020

Amani Lewis

Influences

54

Picture Book

68

44

Product Reviews

26

Events

86

Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe

118

Trey Abdella

San Francisco, New York, Europe and Beyond

142

Perspective Arinze’s Heart is in Nigeria

In Session

56

On the Outside

94

Danica Lundy

126

Bianca Nemelc

Sickid and the Next Generation of LA Art

60

Book Reviews Paul Whitehead, Lynette YiadomBoakye and Windows on the World

6 WINTER 2021

102

David “Mr StarCity” White

Right: Brian Calvin, Composite Sketch, Acrylic on linen, 30" x 40", 2020. © Brian Calvin, courtesy of the artist and Anton Kern Gallery, New York

78 Brian Calvin

STAFF

FOUNDER

PRESIDENT + PUBLISHER

ADVERTISING + SALES DIRECTOR

Robert Williams

Gwynned Vitello

Mike Stalter

EDITOR

CFO

Evan Pricco

Jeff Rafnson

ART DIRECTOR

ACCOUNTING MANAGER

Rosemary Pinkham

Kelly Ma

CHIEF TECHNICAL OFFICER

C I R C U L AT I O N C O N S U LTA N T

Nick Lattner

John Morthanos

DEPUTY EDITOR

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Kristin Farr

Sasha Bogojev Jewels Dodson Willian Dunleavy Kristin Farr Sarah Hagi Shaquille Heath Ania Hobson Charles Moore Evan Pricco Nathaniel Mary Quinn Michael Sieben Gwynned Vitello Matt Wake

[email protected]

CO-FOUNDER

Greg Escalante CO-FOUNDER

Suzanne Williams

ADVERTISING SALES

Eben Sterling A D O P E R AT I O N S M A N A G E R

Mike Breslin MARKETING

Sally Vitello MAIL ORDER + CUSTOMER SERVICE

Marsha Howard

[email protected] 415-671-2416 PRODUCT SALES MANAGER

Rick Rotsaert 415–852–4189 PRODUCT PROCUREMENT

John Dujmovic SHIPPING

Kenny Eldyba Maddie Manson Charlie Pravel Ian Seager Adam Yim

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Sasha Bogojev Colin Brennan Jessica Foley Dan Kvitka Danica Lundy Grace Miller Alex Nuñez Eddie O’Keife Christopher Sherman Moira Tarmy Austin Willis

TECHNICAL LIAISON

Santos Ely Agustin

Juxtapoz ISSN #1077-8411 Winter 2021 Volume 28, Number 01 Published quarterly by High Speed Productions, Inc., 1303 Underwood Ave, San Francisco, CA 94124–3308. © 2016 High Speed Productions, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in USA. Juxtapoz is a registered trademark of High Speed Productions, Inc. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission is prohibited. Opinions expressed in articles are those of the author. All rights reserved on entire contents. Advertising inquiries should be directed to: [email protected]. Subscriptions: US, $29.99 (one year, 4 issues); Canada, $75.00; Foreign, $80.00 per year. Single copy: US, $9.99; Canada, $10.99. Subscription rates given represent standard rate and should not be confused with special subscription offers advertised in the magazine. Periodicals Postage Paid at San Francisco, CA, and at additional mailing offices. Canada Post Publications Mail Agreement No. 0960055. Change of address: Allow six weeks advance notice and send old address label along with your new address. Postmaster: Send change of address to: Juxtapoz, PO Box 884570, San Francisco, CA 94188–4570. The publishers would like to thank everyone who has furnished information and materials for this issue. Unless otherwise noted, artists featured in Juxtapoz retain copyright to their work. Every effort has been made to reach copyright owners or their representatives. The publisher will be pleased to correct any mistakes or omissions in our next issue. Juxtapoz welcomes editorial submissions; however, return postage must accompany all unsolicited manuscripts, art, drawings, and photographic materials if they are to be returned. No responsibility can be assumed for unsolicited materials. All letters will be treated as unconditionally assigned for publication and copyright purposes and subject to Juxtapoz’ right to edit and comment editorially. Juxtapoz Is Published by High Speed Productions, Inc. 415–822–3083 email to: [email protected] juxtapoz.com

8 WINTER 2021

Cover art: Amani Lewis, A Midnight Woman, Acrylic, screen print, glitter, earth pigment, textile and digital collage on canvas, 52" x 64", 2020, Collaboration with Alissa Ashley and Ebonee Davis

JUST IMAGINE... that since 1955, Liquitex has never stopped evolving. From product innovation to supporting artists around the globe, we break boundaries to help artists find their flow. As we celebrate our 65th anniversary, we’re grateful to the artists who have helped inspire our creative story. Now we’re excited to see how we can be a part of yours.

Soft Body. The Original Fluid Acrylic. First of its kind, Soft Body changed the game for artists everywhere as the original water-based acrylic. Incredibly versatile, use it to paint, pour, glaze or print on almost any surface.

Heavy Body. The Thick Acrylic. Our highest viscosity paint, Heavy Body is satisfyingly rich and smooth. Holds crisp brush strokes and knife marks, ideal for impasto and creating texture.

Acrylic Gouache. The Ultra-Pigmented Matte Acrylic. Our most intense color, Acrylic Gouache gives the ultimate flat matte effect. Permanent and water-resistant, perfect for solid color blocking, layering, illustration, and design.

Acrylic Ink. The Liquid Acrylic. Our lowest viscosity paint, Acrylic Ink is ultra-fluid pure permanent color. No dyes, no fade, perfect for color washes, pouring, pen & ink, and watercolor techniques.

For more information, please visit: www.liquitex.com

EDITOR’S LETTER

Issue NO 216 I remember taking a night train from Paris to Madrid on the night of the 2004 US Presidential election, in my bag a copy of the Gunter Grass’s magnum opus, The Tin Drum, which I’d been slowly reading throughout my trip, searching for find some sort of consolidation with the chaotic early Bush years and Grass’s interpretation of siilar times in WWII Germany. Immersed in this art created and written after such tumultuous years, and The Tin Drum’s maniacal, surreal strangeness has almost come to symbolize what the twentieth century understood about itself. A main character literally steps out of time to observe a monumental shift in humanity, but “remained the precocious three-year-old, towered over by grown-ups but superior to all grown-ups, who refused to measure his shadow with theirs, who was complete both inside and outside,” was about to take on a post WWII world where democracy teetered on the brink of collapse. It is stunning art. I think about this as we, about to publish the Winter issue, are on the precipice of so much apprehension and uncertainty. Or, what is so bizarre, maybe on the brink of a revival, a time 10 WINTER 2021

of ideas, progress and understanding. At the risk of sounding naive, I look at the readers and artists of Juxtapoz who participated in the pages of our 2020 Quarterlies and see a year where we all decided to step out of institutional templates and choose our own version of an ideal world—on our own without a rulebook or permission. I don’t imply identity with Oskar in The Tin Drum, but I recognize the significance, the imperative of art being made in the wake of catastrophic moments. We make the decision to be collectively curious and shape a world of inclusion and new ideas. We aren’t taking night trains across Europe right now, but we do have the opportunity for so many cross-cultural encounters. Winter 2021 cover artist, Amani Lewis, is a brilliant emerging voice who combines so many mediums in their work that we feel like we are going through our own schooling to understand their craft. But one thing is certain: Lewis is part of a new generation of artists for whom collaboration is the lifeblood, inviting us to share their collective practice. Mr StarCity, the NYC-based painter who has channeled infectious love and care for others

into his professional vision, is on the brink of a major moment, soothing many of us along the way. Steven Sweatpants, Aurora James, Trey Abdella, Danica Lundy, Brian Calvin, Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe, Bianca Nemelc, Maria Qamar… these are all fresh thinking artists who exemplify what a new decade will begin to look like in art. Collective mindsets, inclusive visions and a refusal to be predetermined by the past. If you are hesitant about rewriting history or venturing into the vaunted lexicon of Art, we offer that opportunity in these pages. We owe it to our readers, artists and the blueprint that was established in 1994, when Juxtapoz was created as a platform for alternative cultural voices. 2020 might be defined by the pandemic, social unrest and a test of democracy. Join us as we seek to broaden and embolden what the next decade can be. Enjoy Winter 2021.

Above: Amani Lewis, Murjoni (NITT edition), Acrylic, pastel, glitter and digital collage on canvas, 56" x 38", 2019

Susan Krueger-Barber (MFA 2017), BIG HEARTED PEOPLE NEED SHARP TEETH, 2017

M FA

LOWRESIDENCY Designed for contemporary artists, writers, educators, and scholars.

Apply Now for Summer 2021 saic.edu/lowres DEADLINE: JANUARY 10

SAIC GRADUATE ADMISSIONS | 312.629.6100 | saic.edu/gr | [email protected]

STUDIO TIME

Ania Hobson A Deeper Interrogation I have been painting for about seven years, changing studio spaces over time. My current studio is on an old American Air Base in Suffolk County in England, where the old runway tracks are now left with the skeletons of old air jets that sit in the middle of nowhere. In the distant surroundings are empty hangers and the old control tower which are the last echoes of their history. My studio space is an old interrogation room which used to hold a two way mirror—where it was all about figuring someone out, provoking and creating anxiety in order to get confessions. We use body language to observe reading into 14 WINTER 2021

people's emotions. I like to think this is how my work is seen... with less of the interrogation aspect. I am a big fan of silent movies where little is said, and I like my work to be seen like this. When I was younger, I used to create comic strips of storylines that I had invented, and I feel like I have reverted back to this now in my work. The characters that I paint are always looking out of the frame, as if the story isn’t finished and there’s more going on outside the scene, rather than in the painting. There’s so much that can be conveyed in an expression; it’s our biggest form of recognizable communication. Especially the

eyes and eyebrows, which are the most prominent features in which we read emotion, which is why I exaggerate them. Emotions are not only worn on our facial expressions, as they also can also trigger emotions; so each painting that I make will carry some feeling that I was experiencing at the time. Everyone reads into expressions differently and this can be a reflection of the person themselves. —Ania Hobson Ania Hobson had a solo show last fall at Catto Gallery in Hampstead, London. @ania_hobson

Above: Self-portrait by the artist

January 9 - February 13, 2021

REPORT

On Award Tour From LA to The Bay, Troy Lamarr Chew II Shines Troy Lamarr Chew II is a precious gem who fittingly paints symbolic glints and sparkling jewels. He won the prestigious Tournesol Award and residency at San Francisco’s Headlands Center for the Arts in 2020, and when the studios temporarily closed, Troy headed back to his LA studio to continue painting for two solo shows, both stunners. Kristin Farr: Tell me about your show at Parker Gallery. Troy Lamarr Chew II: It was titled Fuck the King’s Horses and All the King’s Men. It was inspired by an incident that happened the night I graduated from undergrad. I got beat by the police when I was walking home, and then thrown in jail. They knocked my teeth out, and I was trying to make a show remembering that. I made three paintings in the shape of a grill or a tooth, and each one commemorates the teeth I lost. I was thinking about the fragility of life, and teeth, specifically. The glasslike self-portrait was made at The Headlands center for the arts, right when I had gotten the Tournesol Award. I was thinking about my place in San Francisco, as a black dude, and I was also Uber driving. It was this weird feeling of invisibility in several aspects of my life, so I wanted to recreate that in a painting. 18 WINTER 2021

I’m so sorry that happened to you with the police. You’ve said it was a catalyst. Not to give them any praise, but it woke me up and showed me that I wasn’t living for anything. I was just going with the flow, drinking and going to parties because everyone was, versus thinking for myself and doing what I want. It was a big growing moment, if anything. It’s still a motivator, because, when I see my tooth in the mirror every day, it reminds me to stay in control. It was supposed to take away the shine inside of me, but it really brought it back out. With Fuck the Kings Horses and All the Kings Men, I wanted to make a metaphoric painting to show that the shine is still gonna keep going, whether you knocked my teeth out or not.

that they were knocked out, I see their value even more. I have fake teeth, and I think about having porcelain in my mouth, versus my natural teeth often… but when I put gold in, it’s me choosing it, like a decision I made—not just the porcelain the dentist gave me by default.

You paint light and reflections so well, with the gems, too. What’s the symbolism with jewels? I was thinking a lot about how rappers with diamond or gold teeth use metaphors about how their words are pricey, or the words they say have a price tag.

I was looking at how “grillz” changed throughout time, and even within my own family. My dad has a false tooth in the front, my Granddad has two front false teeth... and they’re gold. Then I have three, so I’m looking at that lineage of the front teeth being replaced. But yeah, hopefully I’m the last one with these false teeth in my family.

It’s hard to vocalize, but also thinking about how my mouthpiece was damaged... putting stones and gold in there is my way of repairing it. That’s the only way to elevate broken teeth. It’s not a regular tooth, it’s gold, it’s a precious metal, so it elevates the tooth to a whole other level. But now

Teeth are significant. They’re used to identify people and all that. I was kinda thinking about that in the painting with the red stones. It has ancient skulls on it, linked to Mayan and Egyptian culture. They used stones to make their teeth beautiful, but the gold was typically a form of dentistry. Bridges were made with gold wire or gold plating to keep the teeth together.

Amen. I always thought it was interesting that the most common dream across all cultures is about losing teeth. The teeth not being perfect, or the front of your face not being “presentable,” that is scary to people,

Above left: Three Crowns (8), Oil and acrylic on canvas, 40" x 46", 2020 Above middle: Three Crowns (7), Oil and acrylic on canvas, 36" x 42", 2020 Above right: Three Crowns (9), Oil and acrylic on canvas, 40" x 46", 2020

REPORT

especially when thinking about the pain. It makes me think of the tooth fairy or even Humpty Dumpty, and how he got cracked and nobody could fix him. All the king’s horses and all the king’s men tried to put him together again… But I feel there’s a line in that story that they’re not telling us. He didn’t just fall and nobody could fix him. That story had to be about fragility of life, or teeth at least. But that missing piece of the story reminds me of the police or authority figures covering something up and reporting it differently. You paint figures in a lot of different ways. I’m kind of a different painter with each series. There’s a series I have called Out The Mud, where I’m working with West African cloth. These cloths are usually understood from generation to generation within Afrian culture, and are typically passed down. But since I’m not a part of that culture anymore, I’m searching for that connection. I kind of let the cloth speak to me.

I recreate the cloths, then fill in the fabric with something that I think parallels black culture in America—just searching for the similarities and differences within the two cultures. I also don’t like to show the faces in the Out the Mud paintings because it’s more about the situation. I want the audience to fill it in—if you don’t know the situation, it could be anybody... it could be you. Tell me about the other self-portrait where you are more vaporous. Invisible Man. I was thinking about the invisibility of being in the art world and in San Francisco. You could come to my shows and not even know I’m the artist. There’s been so many times where people talk to me like I’m anyone else at my show, and they might say the paintings are cool, and then after I say thank you, they’re like, “Oh, you did this?” But then, I was an Uber Driver, and people would hop in, and ask if I’m Troy, then almost instantly

Above left: Fuck the King’s Horses and All the King’s Men, Oil on canvas, 36" x 48", 2020 Above right: For Free, Oil on canvas, 2018

put in their headphones. It was like I wasn’t being seen, but, I was, at the same time. That’s why I made it like a glass invisible man, something you can see, not totally invisible, but you can see through it if you choose to, or not. You think a lot about words in your work. Language is the biggest thing in my practice because it’s all a story to me. I’m trying to convey an idea to you, and I’m trying to get it off as clear as possible, even though I know everybody will have their own interpretations. I have an idea I’m trying to get across, and I do that through my visual language. Your Slanguage paintings are like riddles with research. It’s like when you listen to hip hop. Some lyrics go over your head, and you don’t know what they’re saying, but sometimes you do. Listening to more of that music, it can help explain itself, like context clues, but it goes deep sometimes.

JUXTAPOZ .COM 19

REPORT

I’m researching from the beginning of hip hop to now, so that’s almost 50 years worth of words. It’s a lot of music to listen to, but I feel like I have to do the research to learn, and that is listening to music. Let’s talk about your latest show at Cult Exhibitions. Yadadamean, that show was all about the slang created in the Bay Area, so it’s a lot of E-40, B-Legit, Mac Dre and Too Short references—all the words they created that are now popular within hip hop culture and American culture. I typically group the words based on topic, then put all the ones that relate into one painting—looking at it as a visual lexicon. Cheese, bread, paper—all words for money created in the Bay Area. Weed references they made—crutch, broccoli, cauliflower, Girl Scout cookies… You hear 20 WINTER 2021

them say it in the songs, but you gotta use them context clues to fill in the blanks, especially because some of that music was made 20-ish years ago. There’s a lot of wordplay that was created right here in the Bay, and a popular weed company called Cookies comes out with different strains that are sweet-related, and that’s more slanguage that gets put into the culture, and into one of my paintings. Once a rapper says it in their songs, it’s everywhere. I listen back to who said things first; it’s a lot of hours of listening to music. 420, also coined in the Bay. I have something in Yadadamean referencing that too. What other cross-cultural connections stand out to you?

There’s a connection that Black people have to Africa that is obvious, but it also needs understanding. The way we dance, for instance, or even the way I paint, I see connections, because the traditional African cloths are also paintings. They were painted with natural materials from the Earth, just like oil paint comes from the Earth. The cloths are just like the paintings we look at that are worth millions of dollars. It’s all painted on cotton, it all comes from the Earth, both are the same thing, you know? That’s why I put them both on the same picture plane—now which one is worth more? I’m trying to bring them to the same level. Troy’s latest solo show, Yadadamean, is on view at Cult Exhibitions through the end of 2020. His solo show at Parker Gallery was on view in September.

Above: Ball Street Journal, Oil on Canvas, 48" x 36", 2020

REVIEWS

Things We Are After Fresh and On Deck

Only NY Highland Fleece Brr... winter. What is Chicago in December is San Francisco in July, but wherever there’s a chill, Only NY has you covered. The team at Only creates some of the best pieces for these colder months, and they regularly start and close the year with some classic drops. For this season, they have redesigned their signature fleece with some new features, including new chest pocketing and essential heat-retaining microfiber lining. We have our eyes on the new colorways: the Highland Fleece comes in Stone, Leopard, and Olive. Something tells us that Leopard print is going to go fast... onlyny.com

Darien Birks x Madhappy Capsule Collection Back in 2018, the olden days, when we used to travel for Basel Week, Jux deputy editor Kristin Farr wandered into the Wynwood pop-up of Madhappy. Now, she is one of their biggest collectors and loves the Local Optimist line best. Featured in this issue, illustrator Darien Birks [see page 34], created Madhappy’s first collab capsule, BUDDY, a good acquisition to start your collection. The quality is beyond primo and, most importantly, you will be in support of a company that raises mental health awareness alongside their positively positive gear. madhappy.com

Globe x Pantone® Color of Year Dipped Deck Box Set This is such a perfectly smart and simple idea, so it’s hard to believe we’ve never seen a skate deck in this guise. Having admirably functioned as an art piece on many walls over the years, the aesthetic becomes uniquely important depending on how you like to design your home, so Globe Skateboards has come up with a very modern approach by teaming with Pantone® colors. A special Pantone Color Of The Year Dipped Deck Box Set, featuring 5 limited edition 8.25" decks, each paint-dipped in the official Pantone Color Of The Year and engraved with color name and Pantone number has been released twice this year. The current Box 02 set features 2010 Turquoise, 2009 Mimosa, 2006 Sand Dollar, 2002 True Red and 2000 Cerulean Blue, created in an edition of 200. globebrand.com

24 WINTER 2021

PICTURE BOOK

26 WINTER 2021

Above: Curfew, New York, New York, June 2020

PICTURE BOOK

Steven Sweatpants Back to Basics “This is the first night that the city had established a curfew. I remember my mom telling me to watch my back when I went out that night. I didn’t know what to expect. The commute from Bed Stuy to uptown felt faster than ever. My palms were lightly sweating and my thoughts were moving faster then the train. But when I finally got out, and saw the thousands of humans in unison, I felt immediately at ease. My soul was blanketed with conviction and reassurance that we were in this together. The further we walked into the night, the stronger we grew as movement. The closer the clock moved towards curfew, the more empowered we all felt. While I was walking in the crowd and documenting for The New Yorker this summer night, I literally walked into a car. It was somehow masked in the center of the crowd, just creeping at a slow speed but with allies in the whip in solidarity. Me and the brother made direct eye contact with each other, and he sat on top of the car and slowly raised his fist. That moment felt like the definition of what it not only felt to be out that night, but how we will define our generation’s stance on the black experience.” —Steven Sweatpants

Ask Steven “Sweatpants” Irby how he got his start as a photographer, and he’ll describe a brief stint working at GameStop in the early years of Instagram. A customer entered the East Flatbushborn, Queens-raised photographer’s store, mentioned the app, and the street photographer knew he’d stumbled upon something that would deeply impact his life. He started documenting his neighborhood via iPhone, bought an old Canon Rebel XSN film camera for fifteen dollars, and the rest is history. The iPhone and film combination helped to get his foot in the proverbial door, and today Sweatpants shoots digitally more often than not—generally with his Sony a7R III. The cofounder of Street Dreams magazine is signed to Sony as part of the Alpha Collective, which, with a sly smile he admits, consists mostly of his friends. Aside from that, he explains that Sony cameras offer an ideal blend of speed and light. Sweatpants also loves his Contax T2, a 35-millimeter film camera he can slip into

Above: Steven Sweatpants, Bedford Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, Photographed by Jessica Foley

his pocket when needed. The street photographer doesn’t have opposing gear, and that’s the way he likes it. “I love being quick and nimble. I don’t mind moving when I take my photos.” It’s an approach that’s rooted in the ideals behind punk rock and hip hop—a clear, unadulterated take on what’s really happening out in the world. When the artist got his start, his sole purpose was to capture his neighborhood. He set out to take control of the narrative and tell an objective story. “For every single photo we take in the street photography community,” he says, “we’re documenting what’s really happening.” The overarching goal is simplicity—that is, in the sense of going back to basics. There’s a beauty in the simple things, Sweatpants explains: a father and son playing basketball in the park, intimate moments that may seem small in the grand scheme of the world—yet these are the moments the artist hopes to bring back to the forefront of our lives.

JUXTAPOZ .COM 27

PICTURE BOOK

28 WINTER 2021

Above: Juneteenth 2020, Brooklyn, New York, June 2020

PICTURE BOOK

“I think it’s really important to show just the most humane, simple human interactions,” he continues. “People are so caught up in all the complicated issues that are in the world right now, but if you can get this right, maybe you can get the other stuff right.” In an introspective take on his craft, Sweatpants goes on to explain that he wants people from all backgrounds to view his photographs. On the one hand, he doesn’t want to bring his community down, but on the other, he doesn’t want viewers to stereotype Black people. How can his approach— no matter what outsiders say about street photography—not be a form of fine art in this way? Street photography may seem chaotic to some, but he is living proof of its intentionality. Energy is critical to the artist’s methods. There’s a sense of taking in the energy of the day or the moment. On Juneteenth this year, Sweatpants remembers the minute that demonstrators reached the Williamsburg Bridge, he thought to himself, “Is it actually about to happen?” And so the bridge was barricaded, and the artist got in position— anticipating whatever might come next. “I’m not the kind of guy to think I’m going to stumble upon the work,” he says. This combination of adaptability and purpose culminated in the artist’s iconic Juneteenth 2020 image. What’s in a name? Ask the artist about his alias, and he’ll credit his mother. When the photographer was a kid, the “Sweatpants” moniker often came down to his having to do chores—or really anything he didn’t want to do. Sweatpants would make excuses, claim he was too comfortable to get up and work, and somehow evade his daily tasks. In a way, it was empowering: He’d put on a pair of sweatpants, play a video game, start drawing to make up his graffiti name, because everyone in Queens was doing that at the time. “My mother looked at it almost as my superpower,” he explains. “Like I needed those sweatpants so I could be empowered.” That’s the beauty in the artist’s nickname. Yes, Sweatpants likes to be comfortable—but he wants those around him to experience the same thing. This, he explains, is a key element of his personality. In fact, the artist aims to inspire comfort in all his work, in his artistry, in his Instagram captions, and in his overall personality. The oft-overlooked attire that’s inspired his name is, in fact, multifaceted and very much on-brand. To this end, Sweatpants complements his street photography with striking black-andwhite portraiture. He inspires the sense of comfort as a creative director, crafting intimate images of figures like Dapper Dan and Derrick Rose. Viewers might take note of the change

of scenery, but they’ll quickly recognize the artist’s signature candid style. “I’m the kind of photographer who really works off energy, and it’s incredible to meet someone who has a really kind and empathetic kind of energy,” he says of his experience photographing Rose in Detroit. The images he captured of the basketball pro

Above: I’m still sick I couldn’t get any chicken from that dude name Gus, Detroit, February 2020

mean a great deal to the artist, and with the COVID-19 pandemic thrown into the mix, they’re all the more impactful. Sweatpants, one might argue, is largely an autodidact. He’s learned a great deal from experience—and the artist is more than willing

JUXTAPOZ .COM 29

PICTURE BOOK

30 WINTER 2021

Above: To whomever is bumping Jodeci mad loud on my block, I respect you, New York, New York, October 2018

PICTURE BOOK

to share key takeaways with his audience. His Ted Talk, “Don’t Live to Pay Your Rent,” honors his artistry, and though he was “nervous,” at the time, there’s a sense of authenticity (and a series of emotional stories) you won’t want to miss. “I had to put those stories at the forefront, and I didn’t want to screw it up,” he discloses. Sweatpants explains that even if the content didn’t get a million plays, his goal was to offer something people could walk away with—to offer something they could take home and apply in their own lives. And then there’s Street Dreams magazine: the artist’s baby, so to speak, for the last six or seven years. He can’t help but laugh that it took a couple of Canadians to help him launch a magazine dedicated to the New York street photography scene. What started with a creative team appreciating his captions from another corner of the continent led to an outdoor meeting at the Williamsburg Bridge,

Above: My grandma knows how to slap box, Havana, Cuba, April 2017

and the publication took off! Sweatpants and his co-founders discussed the concept, started shooting, and got to talking about launching a Tumblr page featuring the artist’s photographs. The idea was to go digital from there—but the team’s digital dream went to print just 48 hours later. They printed only 100 or so copies of their first issue, but things took off relatively quickly. Reed Space, Jeff Staple’s legendary street wear store (unfortunately, now closed) showcased the artist’s photographs in issue 003, with rooms packed to capacity and lines snaking around the corner outside. Sweatpants can’t help but seem a little dumbfounded by the growth of his project. Consistency is a common thread in the artists’ work, and, “We’ve been able to really keep it going and keep it consistent. We’ve been able to build an agency.” Radio shows, podcasts, an issue of Street Dreams dedicated exclusively to his co-founders’

native Vancouver—Sweatpants and his team are branching out, strategizing, and endlessly appreciative of the opportunity they’ve been afforded. Because, ultimately, the artist’s objective is to take back the narrative of his community—to fill a void for the middle ground and give the pretentiousness linked to so much of the art world a much-needed overhaul. “This is the best way that punk rock and hip hop vibe comes into play,” he says. “This is for the people— and I’ve always had that as my backbone.” This certainty has given Sweatpants a sense of purpose. It’s also helped him sharpen his muscles and develop his eye for photography. And by truly engaging with his community in this way, Sweatpants reveals that street photographers can come together and document what’s really happening out in the world—in real time. —Charles Moore @stevesweatpants

JUXTAPOZ .COM 31

photography by Chris Behroozian

Dropbox.Design

DESIGN

Nothing But The Hits Darien Birks Pivots From Nike His portrait of a suave figure in a powerful puffer coat was all we needed to see. The stylistic, pop illustrations of Darien Birks had us hooked before we even learned of his many influential years as art director at Nike. Recently he’s leaned into a full-court-press on personal work and illustration,

resulting in excellent early stats. His distinctive new zine visualizes this pivot and is aptly titled Knew Normal. Basketball is integral to his work, and when asked about his favorite players, he pays respect, “Each of their stories is something that I have applied to my journey as a creative.”

Kristin Farr: How did you end up as an illustrator after working for Nike and making music as The Stuyvesants? Darien Birks: In 2011, I was living in Brooklyn, freelancing as a designer. I was asked by a friend who was working at Nike to submit some of my work. It involved branding for a few NBA athletes. The team at Nike liked my work, and eventually they asked me to come out to Portland and meet them. I was happy with what I was doing at the time and wasn’t immediately ready to uproot and move across the country, so I sat on the thought for a couple months—ultimately, it was too good of an opportunity to pass up. While at Nike, I was learning a lot of new things that I didn’t already have in my toolkit. I was expanding my knowledge base within my industry and sharpening up my craft. However, going to work isn’t enough for me, I needed to keep growing in other ways. So I began illustrating after work, on weekends, just to stay curious, and to see where it could go. Working on our album covers for The Stuyvesants was another outlet that helped me get back into illustrating. When I left Nike in early 2020, I had a goal to push my illustration just as much as my art and design direction. I no longer wanted to do one thing, so I took a risk on myself and moved full steam ahead. How does your love for basketball go beyond work? I am a major lover of sports. I played sports as a kid, and I play to this day. Mainly basketball, but I grew up playing football, baseball, and a little golf as well. Sports culture is everything to me, both on and off of the playing field. I’m interested in the stories, the athletes, the team history, everything. I love sports talk radio, podcasts, magazine articles, and books. I text sports trivia back and forth with certain friends regularly, just to stay up on our sports knowledge. It’s a real thing for me. I definitely have always admired my sports heroes through portraiture, or through creating a signature shoe for them. As a kid, I would sketch for hours, drawing shoes and athletes. I loved drawing the jerseys, and trying to get as close to an athlete’s likeness as possible. That was my haven, my escape, my therapy. I had no idea that it

34 WINTER 2021

Above: Bubble Goose, Digital artwork, 2019

DESIGN

was shaping what I would become as an adult. It’s extremely ironic to me.

human and feel this just as much as we do. I hope it gets more momentum.

This was an impactful year in basketball, with the NBA strike and the loss of Kobe Bryant. How do you feel about it all, and how did you end up working in this field you’ve always admired? Basketball has been through so much this year. I’ve never witnessed this many things happening at once, within the same season. It has truly been crazy to see.

Losing Kobe felt unreal. He was young, and beginning a new chapter in his life postbasketball. He did a lot for the evolution of the game, and that effect is carrying on within the players that he inspired. He’s gone, but Kobe will never be forgotten.

The players sitting out to observe social injustice, systemic oppression, and inequality was great to see. I think there should be more of it. There are so many things going on in the world that are more important than sports—it’s telling that even the greatest athletes feel the same—after all, they’re

Above: Pegged, Digital artwork, 2020

I ended up working in the basketball category at Nike through creative leads David Creech and Michael Spoljaric. They both knew that I was a huge basketball fan, and that I was at a point in my career where I was ready for something new within the organization. Basketball at Nike was going through a shift, a reset in a sense, and they were looking to build a new team. Those

guys hand-picked me for the role and the rest was history. I had my best years at the company working in basketball, it was truly a dream job. What projects with Nike are you most proud of? If I had to choose a few—I’d say launching the NBA x Nike partnership, KD 11 (Kevin Durant), Hyperdunk Flyknit, Free Trainer 3.0, Kyrie 5 (Kyrie Irving), Nike Adapt 2.0, Zoom Freak 1 (Giannis Antetokounmpo), 2016 Olympics, and Hypercool. I’m sure I’m forgetting something, but those are the first that come to mind. I was admiring your Kevin Love logo with the tree. Can you share the backstory? I spent the majority of my years at Nike creating athlete logos. Our creative director at the time (and close friend of mine), Michael Spoljaric, JUXTAPOZ .COM 35

DESIGN

would create these friendly competitions between our design team. He would make us all create logos and pin them up—and we would pick the best logos that way. The Kevin Love situation was a bit different, because they wanted us to speak with the athlete first, so he appointed me to hop on the phone with Kevin and discuss his logo. We had a great conversation and I was super excited to get started on the mark. He wanted it to be about his roots in Oregon, his family, something timeless, and to subtly incorporate his style of play. The tree represents both the Douglas fir, Oregon’s state tree, as well as family (as in family tree). I wanted that to be the foundation of the mark, as it was for Kevin himself—so it’s placed directly in the center. The K and the L point in opposite directions as Kevin is a two-way player who can score and pass the ball, rebound and defend. I used tall and bold letters to reference his stature at 6’ 10”. It was a lot of fun creating the logo, and the most rewarding part is that Kevin loved it. 36 WINTER 2021

How do you describe your personal style, or styles you’re attracted to? It’s not photo real, but it’s not over-abstracted, and it usually focuses on themes based in pop culture. Fashion, music, sports, politics, that type of thing. I’m attracted to work of the same sort, among other things, but the work of Barkley Hendricks, Emory Douglas, Kadir Nelson, Amy Sherald and Kerry James Marshall, among others, are huge influences for me and my work. I liked your recent capsule collection with MadHappy. What other projects are coming up? The MadHappy work was a lot of fun, and I was thrilled to create their very first illustrated product drop. More importantly, I like what they stand for, being a voice for mental health awareness. I recently finished up a collaborative project with Apple, which focused on young African Americans stepping into power for a new collection of movies on the AppleTV app. Also just finished up a project with Spotify, designing the cover art for a new podcast, Resistance, which launched in October.

What’s something you’ve recently seen out in the world that made you want to draw it immediately? The most recent thing that I spotted that had me anxious to get home and recreate it was noticing the creative masks that people are wearing during this pandemic. It started with simple medical masks, but then, all of a sudden, the masks became really unique and interesting once people realized that this isn’t going away any time soon; so the masks have been way more creative these days. It inspired me to create these super interesting masks on fictional characters, making them all different, with funky patterns and such, giving the subjects different expressions in the eyes—leaving the viewer wondering what they’re thinking. I haven’t fully illustrated them yet, just quick sketches for fun at this point. I want to expand on it to document this time in our lives. Darien Birks’s Knew Normal zine is available now at FiskGallery.com @DarienBirks TheStuyvesants.com.

Above left: Vdot, Digital artwork, 2019 Above right: No Debate, Digital artwork, 2018

Midnight Adventure Abby Jo Turner ‘18

CHANGE THE WORLD WITH YOUR DESIGNS. Apply your passion for storytelling and the visual arts in Columbia College Chicago’s Illustration programs. Develop your artistic skills through studio classes and critiques with a dedicated faculty of professional illustrators and learn to make an impact with your distinct style. colum.edu/apply

FASHION

Aurora James and Brother Vellies Primed for the Pledge Maybe she was born for the role, but the founder of Brother Vellies and the 15 Percent Pledge is named Aurora, the mythical goddess who traveled from east to west announcing the dawn. As a young designer captivated by fashion’s ability to “help us escape to a magical place,” Aurora James sought to represent an inclusive worldview of beauty. Traveling in Africa, committed to promoting artisan work, after meeting the crafters who make “vellies,” the local leather walking boots, she created a pipeline to market their goods. As Brother Velllies became a model of ethical production and sustainability, Aurora saw an opportunity to encourage fairness and the future by asking retail companies to pledge that 15% of their products be produced by Black businesses. New beginnings can make very fashionable, equitable endings. Gwynned Vitello: Now that you have established the 15 Percent Pledge, what is the status and what has been the biggest, and maybe unforeseen, challenge? Aurora James: What an incredible journey this past five months has been. I think we have all learned so much about our World, our country, each other and our collective pain. All of this learning is important so we can then focus on our progress, how we can march confidently forward, together, in the direction of change. I am incredibly proud of the companies that have committed early to the 15 Percent Pledge. This benchmark was a very foreign idea when I introduced it, but it resonated with people, and I have no doubt that it will eventually be the norm in the country. Retailers like Sephora, Macy’s and MedMen are at the precipice of change, not just in their stores but in their industries. I am incredibly proud of Vogue and Yelp, who were our first publishing and tech companies to figure out how they could pledge, and the progress has been wonderful to watch. I must say, for every commitment we announce, there are a handful that never make it there. It takes bravery to publicly commit to such a big step. When I launched the 15 Percent Pledge, I estimated most retailers to be around 7-9% shelf space, but only after investigating did we realize that most sat between 1-2%. We never ask anyone to do it 38 WINTER 2021

Above: Portrait by Grace Miller All other photography: By Christopher Sherman

FASHION

overnight, it’s a multi-year process with a multiyear plan. The painful reality is that not every retailer is willing to commit to Black businesses in such a meaningful way. Back people in this country are worthy of long-term commitments and a true seat at the table. Not only have you founded a business that, since its genesis, has grown organically in terms of

its mission, but you’ve challenged a business model. Do you feel torn between being the CEO/ CFO and being the creative director? I wouldn’t say I feel torn but the dichotomy is alive and well inside of me. It’s hard in a day to flip from some of the emotionally intense conversations we have at the 15 Percent Pledge, to then design a beautiful pair of shoes at Brother Vellies, then run numbers on the business to then return home and

work on writing my book and also be a great friend, lover and daughter. We are all balancing so much, so I would be lying if I said it was easy. But no, that’s not usually when I feel torn. I feel torn over minutia— white lilies or blush peonies, almond or oat milk. I am shockingly decided over the larger issues in life. That said, in your current role, you do both, in that you give others the opportunity to make a JUXTAPOZ .COM 39

FASHION

What role does fashion play now, whether we are homebound or venturing out? Think of how Hollywood put on these extravaganzas so people daydream, or Jimi Hendrix wearing thrift store velvet jackets and scarves, or even little kids dressing up. I think everyday fashion is shapeshifting. It feels to me that women are looking more to themselves versus outside sources on what to wear. I also truly believe that people are rethinking their spending and which companies and brands they’re comfortable investing in. We’re all getting a little more thoughtful about what we “need.”

living creatively. I mean, for you, fashion is not just throwing on sweats, but it’s also not wearing the latest trend. I read an interview with Amy Sherman Palladino, who created Mrs. Maisel, and who, incidentally, is a dancer. Of her art, she said, “When you’re a dancer, it’s not just in class or when you’re in performance; when you’re home, your body is your instrument.” Do you feel similarly about creativity and fashion? What a lovely statement. I am in the midst of a very deep love affair with the people of this planet. I want to learn everything about them and I want to see them thrive and be free. Brother Vellies and the 15 Percent Pledge are an expression of that. How can we all just live our lives doing what we want to do, existing in the pursuit of happiness. When your best friend laughs—do you know that sound? I want to hear that and feel that every day I am on this planet. My Mother was adopted at birth, and she told me that, as such, anyone I meet on the street could be my very close relative. You, Gwynn, could be my cousin. I feel that deeply, the connectivity. I am an only child and my Mother is the only blood relative I know. But somehow I feel like I come from the world’s largest family. Being raised in Toronto must have played a part in your worldview, as it is considered one of the world’s most cosmopolitan cities, and Canada has a reputation for being so darned… nice, producing so many comedians and always ranking high in quality of life surveys. Yes, it absolutely influenced my outlook. They say America is a cultural melting pot, but Canada is a cultural mosaic. The idea is that we retain

more of our heritage and traditions. Growing up, I remember celebrating many different holidays and religious occasions. It was par for the course. We were curious about each other and respectful of each other’s cultures. I miss that. But I’m excited to instill that in my future children. I read that you were named after Aurora (my mother and sister-in-law’s name, by the way) from Sleeping Beauty. My favorite outfits in the movie were not the “transformational” ball gowns, but the black peasant laced corset and brown skirt. Neutral but perfect for wandering around a haunted forest. Everyday clothing can be a fantasy right? Absolutely, much of this life has felt like a fantasy. Some of the most shy pieces I have designed have taken me furthest off-road to the largest adventures. I’m thinking specifically of our Fall/ Winter loafers. The animal prints and woven textures of your shoes and accessories are wearable and adaptable, but not like some monochromatic, uniform line of clothing. Did you intend your pieces to be, say, neutrals with possibilities? My intention really is to design things that people will fall in love with and own forever. And I mean it when I say forever. There is symbolism and thought behind so much of the collections. I often think of my shoes as an extension of me, part of my DNA, and the clothes work around them. So, yes, in a sense, they are all neutral in the way that a redhead is neutral. Or shocking blue eyes are too; it’s just part of you.

40 WINTER 2021

Can you explain what went through your mind when you saw velskoen walking shoes and met the people who made them? What was the thought process that led you to consider helping them sell directly to a wider group of customers? I just thought it was the true example of traditional design. It’s the ancestor of the modern day desert boot. I looked at the shoe they were making and thought it would do well with people in New York, and that maybe by working with these amazing people, we could keep traditional African design practices alive while creating and sustaining artisanal jobs. I started selling these in a booth at the Hester Street Market on the Lower East Side. I wasn’t sure if they would catch on, but I would sell out pretty quickly. A woman who had bought a few pairs over the course of some weeks came by and asked if I had a website—it turned out she was from the New York Times! I quickly made a website and launched my first collection in Spring 2013.

FASHION

What was and is our impression of New York and the industry, any disappointments? I spent time in New York as a teenager. I remember spending an entire day photographing the Alice in Wonderland statue in Central Park just a few months before the Twin Towers collapsed. When I initially moved to New York, I lived in a one bedroom apartment with two other people. But, no, I was never disappointed by New York. Yes, I have been disappointed by people at times. The fashion industry is full of an incredibly vibrant and talented cast of characters in this city. They make for the best, and also the worst of times. But let’s face it, “worst” is a very relative term. And fashion moves quickly, so there is no time to wallow. Chop chop. Then let’s move on to the goods. What fabrics do you particularly like? Are there any new materials you’d like to work with? And, now that you’ve grown bigger, how do you find artisans? I still love working with various materials, but it’s important to me that we use those that are local as much as possible. At our core, you’ll find vegetabletanned leathers. We’ve used soling from recycled tires in the past, we use hand-carved wood from Kenya, floral dyed feathers, along with a collection of other byproduct materials sourced from farmers across the globe. In the beginning, I was able to travel back and forth to Africa frequently, and I would just go to the local market and use whatever was available. We strive to lessen the impact of our production practices by always asking questions and making changes each season. We try not to over order and only order quantities we think we can sell. Somehow, I think your appreciation of process might guide your desire to open brick and mortar stores. Is this still your intention, and why do you think it’s important? A store space is inspiring to me because it can act as a living, breathing brand experience. We have one store in Brooklyn right now which is as manic as my mind. It’s really fascinating. Sometimes it’s totally calm and airy, and people walk in and want to curl up and sleep. Other times, it’s entirely chaotic, which is great. I don’t like retail experiences that are cookie cutter. If I’m working on a new collection, I want you to be able to walk into the space and feel that. Maybe I’m listening to a song on repeat. Maybe I’m burning sweetgrass. Because my studio is upstairs from the store, that connectedness is alive and well. I am going to be writing my book mostly in Los Angeles, so I’ve been considering opening a second store and office out there. We will see, won’t we? Can you tell me about any budding new artists, any new designs you’re excited about? I just went over to view the new Theaster Gates exhibit at the Gagosian, Black Vessel. It’s his firstever solo exhibition in New York. It’s incredibly

powerful. Of course, I’m always excited about what Jordan Casteel is doing, and last year’s Simone Leigh exhibit at the Guggenheim was really inspiring. Hugo McCloud’s portraits from plastic bags are also incredibly powerful. And a man very close to me is releasing another album soon, which I am incredibly excited about. I hate to say it, but sometimes the most beautiful things tend to emerge from the darkest hours. And I must admit, it has been a little dark when I’ve turned my flashlight off this past four years.

As someone who has carved her own path, do you have any advice for folks who may not have an MBA or MFA, but who want to make a difference? Find out what is important to you and make sure to stay true to that. Put trust in yourself and just keep working at it. Sometimes your best mode of transportation is a simple leap of faith. And if all else fails, I will still love you. brothervellies.com 15percentpledge.org

JUXTAPOZ .COM 41

www.onlyny.com

INFLUENCES

Ana Leovy Confetti in Cancún Ana Leovy’s glass is half full, effervescent with bubbles, ready to toast the day and share the good news. Maybe on a solo stroll, maybe with friends and neighbors, the message is clear in her ripe gouache and acrylic pictures. Follow the light like a sunflower, lounge proud with purpose. A tropical storm delayed our conversation, but didn’t dampen her spirits. Gwynned Vitello: Your work has real vibrancy and immediacy, so I can see how you got lots of work as a graphic designer. The paintings kind of burst and sing, but I guess you felt boxed in doing corporate work. Tell me about your transition to full-time painting. Ana Leovy: Thank you! Painting has always been my passion, and, as a kid, I always dreamed of being a painter. I initially wanted to major in visual arts, but ended up going for a “safer” choice and studied graphic design, out of my fear of not being able to have a successful career, of not 44 WINTER 2021

making a living. Although it was not my dream job initially, I don’t regret choosing graphic design as a career. I ended up loving it and I’m grateful because it gave me so many tools I use today. I started transitioning to full-time painting about three years ago. I’d been working as a designer in an ecommerce start-up in Mexico City, completely fed up with the routine and the long commute. It was a good job, but I felt like there was something missing and it felt wrong to stay there any longer. I decided to move to Barcelona and did a masters in graphic design applied to illustration. I think that was my true beginning! My love for design grew while discovering creative sides within illustration. Spain was particularly special to be because I was surrounded by people who lived off art and inspired and pushed me to do the same. I had lots of spare time between classes, so that allowed me to get back to my sketchbook and let it all out. It was very cathartic.

So who or what inspires you? Are most of the subjects interpretations of yourself, as well as fictional characters, famous folks and friends? They are definitely extensions of myself, of my thoughts and emotions. These characters are not normally based on anyone in particular, unless it is a commissioned work, where I’ll get asked to do a representation of a real person. But to be completely honest, doing this makes me a bit nervous. Even though I am not aiming to be realistic with my style, the fact that there are actual people involved reduces my creative freedom, in a way. So I have avoided this sort of work lately, focusing more on personal pieces, where my characters are completely made up. Don’t get me wrong! I also get lots of satisfaction when doing commissions based on existing people. I love how intimate and meaningful this is, but I also think it’s important to step back every now and then and continue this exploration on

Above: Smoking Area, Gouache on paper, 31" x 23", 2020

INFLUENCES

my own so that my work evolves. What ignites my inspiration constantly changes, but lately I find myself needing to portray social scenes like groups of people dining together, dancing, kissing, hugging, simple activities we all took for granted and were taken away. I guess I am craving all of that. Nostalgia is very present in my work. I think there is a lot of beauty in sadness. Rumor is that you practice blind contour drawing. True? How much of that comprises your practice, and does that mean you don’t do rough sketching? I think blind contour practice influenced my distorted traces and how I play with shapes and proportion. But I do it more as a personal exercise to relax my hands and mind. My current figures are a bit more planned and defined, so there is a sketching process involved, for sure.

choosing color, it isn’t something I do consciously, but I lean more towards colorful palettes because their variety brings out a whole new meaning and resonates more with what I want to say. It’s important to me to showcase diversity within my characters, and I don’t feel I have that ability when using only black and white. I also find color very compelling, how it can speak to everyone in a different way and have so much impact.

color. It’s funny because sometimes the concept behind my work is not very cheerful, even though my selection of paint seems to say the exact opposite. I enjoy playing with this juxtaposition because I believe that there are so many hues in feelings and how each one of us sees the world. Certainly, when I find myself down, color gives me positive energy, and hopefully this happens to other people as well when they see my work.

I find color to be some sort of personal diary, so things I can’t say with shapes or words, I say with

How does place play a part in your work, starting with going to school in Spain and

This way of drawing fascinated me since the first time I learned about it back in high school art. I love the element of surprise, not knowing how it will turn out when you finally look at a page that was blank a moment ago. It also helps me be more present, even if it’s just for a couple of minutes, to observe a real life object and all its details. We don’t take time for observation now, always going at such a fast pace and with so much content constantly thrown in our faces. I really struggle with the amount of screen time I am using per day, especially since quarantine, and it makes me very anxious. I’ve been doing a little exercise for a couple of weeks, doing a quick contour selfportrait drawing in the mornings as soon as I walk up. It helps me start off my day more relaxed. Do people sit for your portraits, and when they do, are they seeking a certain look? When I do portraits of real people, it’s never face to face. The majority of my clients are international, so they send me photos and we have tons of conversations that will help me capture their essence. Since I am a realistic artist, I focus more on the personalities, their likes and signature traits. Have you consciously made a self-portrait? Aside from the contour drawing experiment I’ve been doing (and old school projects) I haven’t done any self-portraits, though I definitely see myself reflected in some of the women I paint. I guess that’s inevitable! I may do it as an exercise at some point, but at the moment, it isn’t interesting to me. I like it when the characters are not so real so that anybody can relate. Do you ever do black and white? Does it work for you at all? I did some charcoal and pencil drawings when I was younger, and I still enjoy them because black and white is very romantic somehow. When

Above: Life is a party, Gouache on paper, 23" x 31", 2020

JUXTAPOZ .COM 45

INFLUENCES

then going back home to Mexico? How has the transition been from Mexico City to Cancún? I’m someone who gets bored easily when I spend too much time in the same place, so I tend to move around a lot to spice it up. I am very lucky because I can take my work almost anywhere I go, so travel helps when I am feeling stuck or anxious. I’ve lived in many places, but I think Spain was the turning point. I was doing my Masters, which was really exciting, and it was also the first time I lived completely on my own. This meant plenty of time for myself, so I learned and focused on my creative side more than ever, which led me to where I am today. I was also impacted by the lifestyle and surroundings. I was able to walk everywhere (love walking!), go to parks or cozy cafes to sketch, read and listen to music. I felt so free and inspired! When I came back to Mexico City, I was not able to do that. It just wasn’t a place where I felt comfortable walking alone as a woman. I will always be fond of it; I still like visiting, I have lots of friends there and it’s quite fun! But I chose Cancún for a different quality of life and to be close to my family. That said, moving from the city to the beach has not been super easy, let me tell you. I do not enjoy sweating constantly or sharing my apartment with spiders. The humid temperature actually affects my work as I’ve had to learn to adjust and paint faster so that materials don’t dry up before I’m done. I also cannot store a huge stock of art supplies because the consistency changes. I’m learning little things along the way, but overall, I do feel happier for now. What are your feelings on living and working in the studio, in terms of scheduling, lighting, atmosphere? At the moment, I’m working from home where I have a studio and do everything. I'm definitely needing to have more space for the larger paintings, but I’m still a bit hesitant to have a studio separated from my home. I like that I can wake up very early and go straight to my art room, or even when I can’t sleep. I guess I’ll always have a space for this even if I move outside of my apartment. What part of graphic design work do you especially miss? Branding! Particularly naming, playing with words. Creating the logo, choosing typography, color palette and everything in the process is seeing an idea come to life. I don’t think people give design the credit it deserves. I think painting will always be a part of your artistic life, but I can imagine you designing clothes or living spaces. Ooh, I actually was debating between graphic, fashion or interior design before going to university. I find them all very appealing, so who 46 WINTER 2021

knows? I am definitely open when it comes to new areas where I can explore my creativity. I don’t ever think I would leave painting by choice though. Maybe I would do a capsule thing or collaboration, but I don’t dare want to deal with all the rest. You are such a social person, so I think that making art is definitely a kind of dialogue for you. What’s your favorite aspect of the creative process? It’s hard to narrow it down, but I even get excited from just choosing the materials, and the process

of painting is soothing and energizing at the same time. But there is no better feeling than knowing that somebody out there has connected with your work. This morning I went for a doctor’s appointment and while chatting with a lady at the counter (whom I’d never seen before) she noticed my name and said, “Oh, I have one of your paintings in my house.” What? The world is so small. I love it. @analeovy

Above: Summer Fling, Gouache on paper, 14 "x 19", 2019

ChiCago’s premier urban-Contemporary art gallery

MIAMI IN CHICAGO WINTER GROUP SHOW | DEC 1 - 26, 2020 MARTIN WHATSON | MAU MAU | ALEX FACE COLLIN VAN DER SLUIJS | JOSEPH RENDA JR. MYSTERIOUS AL | DAVID HEO

vertical gallerY 1016 N. Western Ave. Chicago, IL 60622 | 773-697-3846 | www.verticalgallery.com

TRAVEL INSIDER

Lowe Mill Arts An Art Pilgrimage in Huntsville, Alabama Back in sepia-toned times, it began as a textile mill and was later a shoe factory. Since 2001, this cavernous brick building has been home to a tech town’s arts/culture heartbeat. Nineteen years later, organizers tout Lowe Mill as The South’s largest privately owned arts center. It’s located in a soulful working class neighborhood, on the west side of Huntsville, a North Alabama city known for aerospace engineering that helped NASA put men on the moon with 1969’s Apollo 11 mission. Huntsville is also famously home to Space Camp, where generations of kids, including those of celebs like Tom Hanks and Bruce Springsteen, come to indulge astronaut daydreams. The past several years, Huntsville has attracted bold

48 WINTER 2021

font endeavors like the FBI, Blue Origin and Facebook to locate here. The city is about about an hour’s drive from Muscle Shoals, and the fertile recording studio scene that birthed classics by the likes of Aretha and The Stones. In Huntsville, there are local gems for food, drink, art, entertainment and shopping-scattered around town, particularly on the west side and downtown. But if your time is limited, you can get all those things at one address: 2211 Seminole Drive, aka Lowe Mill. Being a former large scale production site for consumer goods has advantages, particularly when it comes to parking. Lowe Mill has no shortage of that. However, this being pandemic-

stained 2020, you won’t be able to drive onto the lot without a mask, as Lowe Mill stations an employee at the former guard gate to check for them. Inside the actual building, the ceilings are high, so combined with masks and surrounded by visitors who tend to respect social distancing, I feel safe tooling around for an hour or two. Inside Lowe Mill, exposed wizened brick walls contribute to the vibe. Looking out across the back parking lot, you can see verdant Monte Sano Mountain slumbering in the background. Lowe Mill likes to emphasize its arts and entertainment, but commerce provides one of the facility’s greatest anchors. Vertical House Records is located in an outbuilding on the grounds’ east side. In 13 years, owners and married couple Andy and

Above: Lowe Mill ARTS & Entertainment complex

TRAVEL INSIDER

Ashley Vaughan have built up Vertical House from a 200 square foot space inside Lowe Mill to their current aircraft hangar-esque digs. Here you can sift through 25,000 used and new records, ranging from classic (James Brown, T. Rex, Fleetwood Mac) to contemporary edge (Courtney Barnett, Thom Yorke, Sheer Mag) to local heroes (Brittany Howard, Jason Isbell, Phosphorescent). Other music-heads points of interest at Lowe Mill include local luthier Danny Davis’ fine handmade acoustic guitars at Tangled String Studios and Patrick’s Nickel’s downhome instruments at Cigar Box Guitar Store.

Inside Lowe Mill’s three-floored main building, you’ll find more than 150 spaces and around 200 artists, makers and sellers. Seven galleries featuring regional artists dot the hallways. Recent exhibits there include Paul Cordes Wilm’s’ popfolk mischief, Phoebe Burns’ dreamy mixedmedia and DaNeal Eberly’s sensual brushstrokes. The galleries are set up in corners and main corridors, between them, punctuating the studios which house painters, sculptors, photographers, jewelers, fiber artists, furniture makers and beyond. During opening night events, art

Top left: Vertical House Records Top right: Galleries Bottom left and right: Studio work Middle left: Tangled String Studios

enthusiasts intermingle with featured creatives and learn what sparks their work. With all this gazing and perambulating to do, fuel is key. For a liquid “go,” Piper & Leaf does soft-bliss flavored hot and cold teas and a minty take on straight-up iced tea, as well as iced and hot coffees. For a little more kick, check out Irons Distillery’s silky small batch whiskeys. Victuals-wise, onsite food trailer Chef Will the Palate’s vegetarian entrees have enough oomph to satisfy even carnivores. Sweet teeth must seek Pizzelle’s Confections, JUXTAPOZ .COM 49

TRAVEL INSIDER

for clever chocolates, candies, mini-cakes and homemade ice cream. Other Lowe Mill food go-to’s include Pofta Buna savory crepes, Suzy’s Pops frozen delights, Happy Tummy’s myriad wraps and, until they close at the end of this year, Mountain Valley’s sublime sourdough-crust pizzas. Gamers get served here too. Timbrook Toys builds and sells a fun, easy-to-learn board game called Hedge Lord. Cozy arcade Hale Electronics boasts a deft mix of classic pinball and video games, perfect for a mid-visit Lowe Mill timeout. There’s also a billiards table in a roomy corner on the first floor. During the fall and spring, Lowe Mill’s Concerts on the Dock, held on the site’s former loading dock, are Friday night fixtures for Huntsville live music fans. The free concert series hosts rising local and regional talents, including Birmingham R&B faves St. Paul & The Broken Bones. In the covid era, Lowe Mill got creative to keep the music flowing, pivoting to drive-in, with Concerts in the Car. During non-pandemic times, Lowe Mill also hosts indoor shows, in their First Floor Connector 50 WINTER 2021

space or an upstairs Studio Theatre, by the likes of Los Angeles punk icons X and bands from Single Locks Records, a nifty Muscle Shoals indie label co-founded by John Paul White. In addition to music and visual art, Lowe Mill hosts events built around film, comedy, poetry, pop culture, fashion and storytelling. Not to mention a vibrant Day of the Dead party. Lowe Mill is open 12 – 6 p.m. Wednesday to Thursday, 12 – 8 p.m. Friday and 10 a.m. – 6 p.m. Saturday. For those looking for afterhours action, nearby Campus No. 308, housed in a former middle school, is home to Huntsville’s two biggest breweries, Straight to Ale and Yellowhammer, as well as scrappy local music bars, Lone Goose Saloon and, simply dubbed, The Bar, and Earth and Stone’s fab-fresh pizza. Further eats can be found down Governors Drive at Stovehouse, a well-curated food garden with everything from ramen to barbecue. If you’re in need of pregame caffeine or postgame brew, Gold Sprint Coffee is just a few blocks from Lowe Mill and pours craft bevs, a cycling-centric space that also hosts occasional art exhibits and

indie rock. A DIY/all-ages music venue dubbed Trash Bone just opened up around the corner. Lowe Mill is one of the first things many Huntsvillians recommend for out-of-towners to check out. One of the most endearing things about Lowe Mill, despite being a frequent tourist destination, is that locals still love it too. It’s also equally accessible to hipsters and strollers. As a Huntsville native and longtime resident, it’s where I go to feel transported from the everyday but don’t have time to travel. Or just to get an eyeful of inspiration. Or pick up a tasty treat or new jams. For first time visitors, the Lowe Mill website and social media is a good way to see what’s shaking or upcoming. You can scout out studios and shops you want to make sure and see while there. But the only real way to experience Lowe Mill is to wander around and explore it in person. You’ll make a new memory or find a keepsake to bring back home for someone special. Or, more than likely, all the above. —Matt Wake lowemill.art

Top left: Lowe MIll water tower Top right: Chef Will the Palate food truck Bottom right: Concert posters Bottom left: Irons Distillery

IN SESSION

SCAD Ervin A. Johnson’s #InHonor Project .Before completing his second bachelor’s degree in photography and an MFA at the Savannah College of Art and Design, Ervin A. Johnson graduated from the University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign with a degree in Rhetoric—which we can broadly define as the use of speech and its ability to create knowledge and use it persuasively. Imagine applying such aural and visual skills to make art, to look out at the world, look within and follow that with a universal language. SCAD Art Sales, a consultancy program offered to students, submitted Johnson’s series, Monolith, to Photo London Digital, the first online international photography fair. Monolith is the third part of a larger series titled #InHonor, a project Johnson admits had been percolating inside for years. The Trayvon Martin 54 WINTER 2021

case lit the powder keg and gave him the impetus to make art that he felt would make a difference. “How could I be more vocal and contribute to this movement and honor this multifaceted thing that exists in the art world, in the real world, on social media, which is why it’s called #InHonor. The project is really about bringing the work to the people it’s made for. It’s meant to be shared online, because I felt like I wasn’t visible for a long time, and I want it to help others feel visible.” Trayvon, the Black Kid in the Gray Hoodie, as well as Kids Driving While Black have all been “painted” in broad strokes, but not heard, much less represented. Johnson took multiple photos, then digitally and physically collaged facial parts to present them as one face. Broad or aquiline noses, hooded or deep-set eyes, dark or light skin, each has a special smile or frown, but each shares a kinship. By sharing the series online, Johnson uses

the rhetorical power of social media to recognize and usher respect to the individual, as well as express affinity with the group. While this is a pretty close to perfect example of an artist experimenting (successfully) in multimedia projects, it also illustrates the opportunities found in a school like SCAD, which, in its photography school alone, offers a panorama of technical classes, from camera systems to lighting styles, from photojournalism to fashion, and real mentoring from faculty. In a time when many of us are re-examining career— and community—there’s hope, there’s buoyancy in seeing Ervin A. Johnson looking inside and sharing his wisdom. That’s Art. —Gwynned Vitello www.scad.edu ervinajohnson.com

Above left: Monolith #25, Photographic mixed media, 16" x 20", 2019 Above right: Monolith #38, Photographic mixed media, 8" x 10", 2019

ON THE OUTSIDE

Sickid The New Folk Sickid is a young, Los Angeles-based graffiti artist and painter, best known for littering LA with an ever-changing cast of cartoon characters and situations, most notable for his work on billboards. His fine art painting includes Angeleno folk art, comics and the irreverent, as well as subjects in a more autobiographical realm. His depiction of scenes growing up around the Catholic Church, the naive painting styles of immigrant neighbors, street characters, and other untrained and raw influences hat also hint at a style influenced by the likes of Neckface and Barry McGee, and has evolved into a uniquely vibrant, colorful universe of its own. He debuted at Superchief Gallery LA in July 2019 with his first exhibition, Smile! You're on Camera, followed by a second solo show with them in Miami in December 2020.

56 WINTER 2021

William Dunleavy: When did you get interested in making art, and how have you seen yourself and your style change since you started out? Sickid: I don’t know. I don’t want to say it was when I was born, but for sure when I was a little kid, I was interested in art. I was always into cartoons, and redrawing them. I liked drawing stuff from Cartoon Network, Dexter, Jimmy Neutron, the Simpsons, and Powerpuff Girls. “Him” from Powerpuff Girls definitely made me sexually confused. As a kid, I loved drawing wrestlers and toys, so I guess that was really my first form of art. I started finding artists I liked around middle school, and it blew my mind that people could do it for a living. That it could be a job was really baffling to me. Then I ended up going to a performing arts high school in LA where they were more focused on music and theatre. But

I went into the visual art department, and that was super good for me developing as an artist. I did a lot of finding myself artistically by mimicking other people’s shit and thinking about who I am, and what kind of communication I wanted to put out in the world. I think that once I finally started to become comfortable with myself and learn that I don’t necessarily need validation from people, it kind of changed into a more “me” type thing. I’m still bad at describing my style and all, but it felt way more authentic once I stopped caring. I don’t feel like I need to describe it for it to be valid. If the work speaks in its own language clearly, then it’s good. Wrestling has seemed to play a big role in your life. Yeah, it played a huge role for me. My older siblings were into it, and some of my earliest

Above: Portrait by William Dunleavy

ON THE OUTSIDE

memories are from wrestling. Like, wrestling is literally the first thing I can remember in life. That, and I grew up playing with wrestling toys and shit. Sometimes, when I get tired from working in the studio painting and stuff, or get down on myself, I’ll listen to wrestling promos to get hyped up. It’s like a self-motivational tool for me. Basically, what I’m saying is Eddie Guerrero is the shit. RIP What’s the meaning behind the name—you think you’ll keep it when you get older? The origin behind my name is that it came from a sophomore in my high school when I was a freshman. He used to bully me and stuff, and I hated going to school because of this motherfucker because he was so mean. He would talk shit about my drawings in art class, and talk shit to me about my outfits and shit like that. He was a Jehovah’s