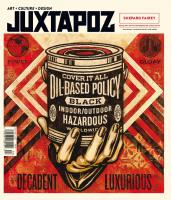

Summer 2021 Juxtapoz

150 110 67MB

English Pages [148] Year 2023

Recommend Papers

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

ART: JAHMAL WILLIAMS PHOTO: PEP KIM LOCATION: PILGRIM SURF SUPPLY 68 N. 3RD ST, BROOKLYN, NY.

CONTENTS

Summer 2021 ISSUE 218

38

134

The Earth Connections of Wing Yau

10

44

Asian Art Museum, SCAD FASH, La Luz de Jesus, Hashimoto Contemporary, Beyond the Streets

Editor's Letter

16

Studio Time

Fashion

Influences Robert Williams on the Legacy of S. Clay Wilson

Lindsay Gwinn Parker’s Northeast Epicenter

48

18

Art Trekking Through the California Desert

The Report

54

24

Maud Madsen Shares the Prize at NYAA

James Jarvis, Spray Cans and Skate Decks

26

Picture Book Vasantha Yogananthan’s A Myth of Two Souls

34

78

MADSAKI

110

Lucia Hierro

In Session

136

Sieben on Life A Six-Pack with Nathaniel Russell

Travel Insider

Nam June Paik at SFMOMA

Product Reviews

Events

138 86

Cristina BanBan

118

Ludovic Nkoth

Pop Life Los Angeles, NYC and London

142

Perspective Rights to the Ephemeral

56

On the Outside How Bristol Changed Underground Culture Forever

94

Hilary Pecis

126

Phlegm

60

Book Reviews Gary Panter, Joe Conzo and Punk in Austin

Design Nicole McLaughlin is the Ultimate Make-Do

102

Khari Turner

70

Jenna Gribbon

6 SUMMER 2021

Right: Danielle Mckinney, Sweet Sixteen, Acrylic on canvas, 24" x 20", 2020. Image courtesy of the artist and Night Gallery.

62

Danielle Mckinney

STAFF

FOUNDER

PRESIDENT + PUBLISHER

ADVERTISING + SALES DIRECTOR

Robert Williams

Gwynned Vitello

Mike Stalter

EDITOR

CFO

Evan Pricco

Jeff Rafnson

ART DIRECTOR

ACCOUNTING MANAGER

Rosemary Pinkham

Kelly Ma

CHIEF TECHNICAL OFFICER

C I R C U L AT I O N C O N S U LTA N T

Nick Lattner

John Morthanos

DEPUTY EDITOR

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Kristin Farr

Sasha Bogojev Kristin Farr Doug Gillen Shaquille Heath Jamie Hombré Wez Lundry Charles Moore Alex Nicholson Evan Pricco Charlotte Pyatt Michael Sieben Liz Suman Gwynned Vitello Robert Williams

[email protected]

CO-FOUNDER

Greg Escalante CO-FOUNDER

Suzanne Williams

ADVERTISING SALES

Eben Sterling A D O P E R AT I O N S M A N A G E R

Mike Breslin

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Brian Blueskye Sasha Bogojev Megan Cerminaro Bryan Derballa Foto Gasul Laura June Kirsch Fanny Latour Lambert Danielle Mckinney Chris Rudz Liz Suman

MARKETING

Sally Vitello MAIL ORDER + CUSTOMER SERVICE

Marsha Howard

[email protected] 415-671-2416 PRODUCT SALES MANAGER

Rick Rotsaert 415–852–4189 PRODUCT PROCUREMENT

John Dujmovic SHIPPING

Kenny Eldyba Maddie Manson Charlie Pravel Ian Seager Adam Yim TECHNICAL LIAISON

Santos Ely Agustin

Juxtapoz ISSN #1077-8411 Summer 2021 Volume 28, Number 03 Published quarterly by High Speed Productions, Inc., 1303 Underwood Ave, San Francisco, CA 94124–3308. © 2016 High Speed Productions, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in USA. Juxtapoz is a registered trademark of High Speed Productions, Inc. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission is prohibited. Opinions expressed in articles are those of the author. All rights reserved on entire contents. Advertising inquiries should be directed to: [email protected]. Subscriptions: US, $29.99 (one year, 4 issues); Canada, $75.00; Foreign, $80.00 per year. Single copy: US, $9.99; Canada, $10.99. Subscription rates given represent standard rate and should not be confused with special subscription offers advertised in the magazine. Periodicals Postage Paid at San Francisco, CA, and at additional mailing offices. Canada Post Publications Mail Agreement No. 0960055. Change of address: Allow six weeks advance notice and send old address label along with your new address. Postmaster: Send change of address to: Juxtapoz, PO Box 302, Congers, NY 10920–9714. The publishers would like to thank everyone who has furnished information and materials for this issue. Unless otherwise noted, artists featured in Juxtapoz retain copyright to their work. Every effort has been made to reach copyright owners or their representatives. The publisher will be pleased to correct any mistakes or omissions in our next issue. Juxtapoz welcomes editorial submissions; however, return postage must accompany all unsolicited manuscripts, art, drawings, and photographic materials if they are to be returned. No responsibility can be assumed for unsolicited materials. All letters will be treated as unconditionally assigned for publication and copyright purposes and subject to Juxtapoz’ right to edit and comment editorially. Juxtapoz Is Published by High Speed Productions, Inc. 415–822–3083 email to: [email protected] juxtapoz.com

8 SUMMER 2021

Cover art: Danielle Mckinney, The Secret Garden, Acrylic on canvas, 16" x 20", 2021. This work is based on a photograph by Fanny Latour Lambert.

EDITOR’S LETTER

Issue NO 218 I doubt I’m the only one who has ever daydreamed their life into some sort of movie scene just before the ending credits are run. I think it’s natural for a “a dreamer,” a category in which I most certainly belong, to imagine oneself in a story of importance, or at least of narrative significance. I think of this in being so drawn to the cinematic romanticism in Danielle Mckinney’s paintings. As a viewer, you are able to recognize yourself in her scenes. A record player is subtly heard in the distance, cigarette smoke lingering over you, nothing too loud in this solitary tableau. These paintings slowly stroll through the frame, ever so quietly. That she called her recent solo show Saw My Shadow, is a nod to both existence and individuality, as well as the overwhelming sense that the female characters share the same sounds, drifting into the dream with the viewer. A book critic rightly assessed that Hemingway "impersonated simplicity," and that, too, perfectly reflects Mckinney. Fulsome with details and profound color use, these works also impersonate simplicity, revealing universal moments of respite, veins of religion and the expression of what it is we see in ourselves— importantly, our ideal selves. This is a painterly issue and, as it turns out, quite cinematic. Mckinney, Jenna Gribbon, MADSAKI, Hilary Pecis, Cristina BanBan, Khari Turner, to name a few of the artists in the Summer Quarterly, provide vignettes where the stories just flow off the canvas. MADSAKI reveals a world of childhood repression, BanBan weaves in and out of conversations of time, and Gribbon graciously invites you into intimate, personal moments of her life. How interesting that, over the course of the last few months, conversation about selling the digital art of our times has overwhelmingly owned the contemporary art dialogue, and we are nurtured by daydreams and classic cinematic expression. One night, like most of us, I was glued to Instagram, transfixed and maybe hoping for inspiration. I admit that, more and more, it rarely arrives in a digital scroll. But one work in particular, The Secret Garden, seen on our cover this issue, emerged onto my feed, almost jarring in its intensity and gaze. The book, the red fingernails, this look of wisdom… maybe even a little annoyance at being interrupted. One of my 10 SUMMER 2021

favorite paintings is Will Barnet’s Woman Reading, and it brought up the emotions of seeing that work for the first time. We've all had the moment, immersed in a good read, when someone voices an untimely inquiry, and you throw that look. It's the essence of that individuality Mckinney channels in her works. Here, that daydream is… broken. And now her character studies the viewer. I find this image as the perfect backdrop for these times, this year in particular. We have been in the midst of an arrival of the future that was promised for decades, and over the past few months has become a study in economics and collective consent. We speak of digital art sales

more than we speak of the essence of art. But The Secret Garden is the antithesis. Undeniably seductive, that look in the painting is one of contentment with pace and place. That knowing look staring back at you. The soundtrack and ending credits start rolling in this film in my head, and I don't want to forget what a good painting does to the soul. A piercing gaze from behind the fold of a book, it's impersonating simplicity, and that’s damn good. —Evan Pricco

Above: Danielle Mckinney, Morning Sun with Marlboro, Acrylic on canvas, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist and Night Gallery.

STUDIO TIME

Lindsay Gwinn Parker A Live/Work in New Hampshire My studio has been in my apartment for the past few years. Initially, it was a choice made out of necessity— it was less expensive and more convenient to paint at home than to rent a separate space that I may not even have the time to use on a regular basis. During lockdown, at the beginning of the pandemic, I found myself, like so many, unemployed with significantly more time to paint, so I felt very fortunate to have my studio in my apartment at that point. The space itself is a 10’ x 10’ corner room with two windows, so it stays pretty bright there all day. This works well for me because my preference is to paint by daylight. One of the greatest advantages of having my studio in my home is being able to roll out of bed in the 16 SUMMER 2021

morning, walk a few steps across the apartment and begin painting. On the other hand, one of the greatest disadvantages is having to meticulously avoid making a mess so that I will get my security deposit back when I decide to move again. To avoid covering the room with paint splatter, I’ve layered canvas drop cloths on the floor and lined the walls with plastic sheets. Instead of using an easel, I lay the canvas on a flat surface so that when painting with diluted acrylic, it won’t drip down the canvas. With larger canvases, I paint them while sitting on the floor, and with smaller works, I lay them on a makeshift table that consists of a large wood panel resting on storage bins which contain old artwork and art supplies.

In the past, I’ve rented studio spaces from dilapidated, partially repurposed mill buildings that were very hot in the summer, poorly heated in winter and very inconveniently located. I definitely prefer to work from home—there’s no commute, there’s more control over the temperature of the studio, and I can stay in my pajamas as long as I want! —Lindsay Gwinn Parker Parker was the winner of the Liquitex x Juxtapoz Announce 6-Week Virtual Residency contest held in 2020 and run in 2021. @artandfavor

JUST IMAGINE… That Sadé DuBoise is a painter, an explorer, and a visual storyteller.

By perfectly blending nature and portraiture, Sadé captures the duality of beauty and strength of her experience living in the Pacific Northwest.

As we celebrate artists around the world, we’re proud to be a part of Sadé’s creative story. Now we’re excited to see how we can be a part of yours.

REPORT

Nam June Paik Traveling Electronic Superhighways Expect no gossamer pastel butterflies or smoldering dark portraits at SFMOMA’s Nam June Paik retrospective, but do expect to marvel at his brand of exquisite, which will be on display in over 200 works made over a five-decade career. Declaring that “Nature is beautiful, not because it changes beautifully but simply because it changes,” the mercurial Korean artist was a trained classical pianist—who later became friends with Yoko Ono. He envisioned and engineered the fusion of multimedia and multiculturalism, predicting, in 1974, in his own words, “electronic superhighways.” I spoke with Rudolf Frieling, Curator of Media Arts. Gwynned Vitello: What were your goals in organizing this show? Rudolf Frieling: From a curatorial perspective, we felt it was time, 20 years after his last US retrospective, to introduce this global visionary to a younger generation and highlight an artist 18 SUMMER 2021

who has consistently challenged our definition of art through technology and his practice across all media. From an institutional perspective, it may be surprising that he has never had a major survey on the West Coast. On top of that, we’d all be hard pressed to find an artist who has addressed and lived such a transnational and global life as Nam June Paik. Lastly, SFMOMA has had incredible fortune in acquiring a major body of work covering all periods of his life so we can tell his many stories within the strong presence of our collection. “The culture that’s going to survive in the future is the culture that you carry around in your head.” How do you present the work with that in mind? Did he show his work frequently, and how? Fellow curator Sook-Kyung Lee from Tate Modern and I were eager to pursue a balanced perspective on Paik’s work, focused not only on his pioneering role in championing technology

in art, but also emphasizing the the importance of artistic collaboration, as well as the ongoing dialogue between Eastern and Western legacies throughout his career. We were inspired by his many memorable quotes and aphorisms that bridge the gap between cultures in surprising, humorous, and at times, mysterious ways. His writings, recently published in English for the first time, show the wit and spirit of a Fluxus artist, as well as a knowledgeable and avid reader of philosophies and histories. What Paik does best—to give an example—is to jump from the figure of a ninja to the properties of a satellite and find that they basically do the same, that is, reduce distances. Paik was always able to “open circuits” technically and intellectually in his associative thinking across cultures and categories. Visitors will enjoy and remember this irreverent, yet caring approach to culture, from The Beatles to cybernetics, to the writings of Eastern philosophers.

Above: Nam June Paik lying among televisions, Zürich, 1991; © Timm Rautert

REPORT

How will you stage the entrance to the show in order to engage visitors? I’m glad you’re referencing what I’ll call his verbal pronouncements, which are very helpful in understanding the work. We will feature Paik’s words, often illuminating how music and its traditions continued to be a foil for his entire career. Highlighting his thinking, music and other ways of performing, but also his artistic persona as a multilingual Korean artist in the West are key to our approach. Another is to foreground his firm foundation in the history of music and what he calls his “action music,” a way of always coming back to musical influences, John Cage being the most obvious. He considered his own work—in his own words—“not not music.” His nephew, Ken Hakuta, felt that imperfection was part of the art, and in fact, Paik said, “When too perfect, lieber Gott bose [God is not amused].” How did he evolve from young classical pianist to participant in the Fluxus movement? As you point out, he didn’t mind imperfection, he even cherished it, and was keen on producing new work—”I go where the empty roads are.” The way that he embarked on a trajectory of exploring opportunities, from early video technology, to analog synthesizer, to laser technology, was his way of making a name for himself. That said, he never forgot that an artist can never walk alone, especially with technology. He was eternally grateful to both his circle of friends, including the Fluxus artists, but also Charlotte Moorman,

John Cage and Joseph Beuys, and also his long friendship with Japanese engineer Shuya Abe. As Paik put it, “In engineering, there is always the other…” meaning you cannot do it alone. How will you incorporate music in restaging 1963’s Exposition of Music—Electronic Television? We dedicate an entire gallery to the groundbreaking show, though not a restaging, as that would take up an incredibly large space and necessitate securing many more very fragile loans. Think of it as a cross section of the most important aspects. We will be as interactive as we can, given the constraints of the pandemic. “Foot-Switch” can fortunately be activated by foot and “Random Access” will be experienced via museum staff. In an adjacent space, we’ll show an excerpt of the historic Stockhausen happening, titled “Originale,” a wild event which originated in a collaboration with painter and salon hostess Mary Bauermesiter, later restaged in New York, again with Paik playing a seminal role as “action performer.” How will you show TV Buddha, and did he practice Buddhism? The artist created a whole series of different TV Buddhas over a period of almost 20 years, but we will show the 1974 iconic original in the first gallery as a nod to the importance of Buddhism as a reference point for Paik. He did not practice it as a religion or meditative practice until a 1996 stroke, but rather valued its influence the same as he would reflect on the legacy of Johann Sebastian Bach and Western classical music.

Left: Self-Portrait, 2005; San Francisco Museum Modern Art, Phyllis.Wattis Fundfor Major Accessions; © Estate of Nam June Paik; photo: Katherine Du Tiel Right: PeterMoore, Charlotte Moorman with TV Cello and TV Eyeglasses, 1971; Peter Wenzel Collection, Witten, Germany; © 2021 Barbara Moore / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY, Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

TV Garden makes me wonder about his reflection, “Nature is beautiful, not because it changes beautifully, but simply because it changes.” He was no Thomas Kincaid, but did ever flirt with pretty, peaceful, or even comfortable? I wouldn’t say “pretty” because he just loved making things imperfect, odd, weird, or using objects in some state of disrepair. I can see a lot of “peaceful” moments, though, thinking about “TV Buddha” or “One Candle.” Whatever one’s personal response, it will invariably be colored by the experience of Paik’s sense of humor. Replacing the TV program with a burning candle is smart, deep and witty. His art is also challenging, noisy and loud, so you will never feel “comfortable” for very long while walking through the exhibition. Will your presentation of two robots, one dedicated to composer John Cage and another to choreographer Merce Cunningham, be unique to this show? Yes, the pairing will be unique to SFMOMA’s presentation, the main reason being that most of these sculptures don’t like to travel! With two of them already in US collections, and one being local, it makes sense for each touring venue to “localize” their presentation. We were thinking in pairs throughout the show, however, since the artist called the series a “family of robots.” I’m particularly happy about our opportunity to show two sculptures dedicated to partners in life and art, Cage and Cunningham, who were like family to Paik. Lifelong friendships and collaborations

JUXTAPOZ .COM 19

REPORT

are a theme throughout, also exemplified by Charlotte Moorman and Joseph Beuys. Will there be a reference to the cellist in the show, and can you say more about her influence? Far from being a performer hired to execute his works, Charlotte Moorman was one of his most important collaborators and will be celebrated in her own gallery. She claimed co-authorship of many of their performances, embracing the conscious breaking of conventions and boundaries. She was the driving force of the New York Avant Garde Festival in the ’60s and ’70s, risking her career as a classic cellist, but gaining a place in art history. A fearless rebel w ay before the sexual revolution took center stage, Paik felt indebted to Moorman until her death in 1991. For all his belief in collaboration, I’m curious about his observation that, “The only way to win a race is to run alone.” Can you clarify, especially since he believed that art was for everyone, and I don’t think of him as competitive. Instead of competitive, I would call him ambitious and curious, but also collaborative and forward thinking. Paik realized early on that he was neither a gifted composer or musician, so he was looking for a way to forge his own path, to find the “empty road.” In 1963, he was the first artist to literally open up the closed circuits of electronic television. As a pioneer, you’re pretty much on your own, but later on, his energy and ambition made massive satellite projects happen because he was a connector and networker. In his friendship with Joseph Beuys, you’ll find he was humble enough to take a step back and be a supporting performer, as in “Coyote III'' from 1986. Does Sistine Chapel close the show, and how much space will you devote to it ? What inspired the installation, and can you describe it in words? Sistine Chapel precedes the final gallery that we call “Self Portrait,” but it’s arguably the culmination of this retrospective. The restaging of this enormous, immersive environment in close dialogue with Paik’s longtime assistant and now curator of the estate, Jon Huffman, was realized for this exhibition as an expression of Paik’s ambition in terms of scale but also as a way of showcasing his way of constantly remixing his own material. It’s a giant Paik Remix and smart way of showing that the 1993 Sistine Chapel was based on the circulation of images like Venice, the site of its premiere, offering a rich history of global commerce as a context. Paik didn’t mind a lineage connecting him to Marco Polo, the difference being that Paik could deal in immaterial goods, images thrown against the walls and ceiling in an unruly, riotous way, unlike the seamless simulations of virtual immersive environments

20 SUMMER 2021

that have populated the commercial and corporate world in the last decade. He so much believed in the ideal of cultural free trade, in telecommunication crossing timelines and geography. How would he gauge the success of current technology companies? Paik would probably assess companies to the extent that they would help him realize his own projects. But, jokes aside, he was a firm believer in two-way participation and engagement, who sadly passed away in 2006 before social media really took off. He would have loved to create his own channels with feedback. He openly acknowledged that America had “corrupted”

him and that his minimal days were over. He integrated Japanese commercials without closed captions in his first TV broadcast “Video Commune” in 1970. Again, he just loved to break rules and I have a hard time imagining him going along with a corporate agenda. If a company wanted to engage with him on a marketing level, they would probably end up doing marketing for him, not the other way around. He understood branding like no one else. Community for him meant sharing the same space and tools, not necessarily the same messages. Nam June Paik will be on view at SFMOMA through fall 2021.

Top: Sistine Chapel, 1993 (installation view, Tate); Courtesy the Estate of Nam June Paik; © Estate of Nam June Paik; Photo: Andrew Dunkley © Tate Bottom: TV Garden, 1974–77/2002 (installation view, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam); Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf; © Estate of Nam June Paik; Photo: Peter Tijhuis

Laure MaryCouégnias Escape Lane

The Visitor, 2021, Oil on canvas 110 x 160 centimeters

June 26 - July 31, 2021

John Greenwood I’ve got a Massive Subconscious

Watch out for the Little People, 2021, Oil on canvas 30 x 40 centimeters

REVIEWS

Things We Are After Summer Skates

HUF x James Jarvis Collection Even when he’s not making drawings or paintings about skateboarding, Londonbased artist James Jarvis is talking about it. Whether encapsulating the element of spontaneity, freestyle or literary depictions of skating, Jarvis wields a poetic touch in showcasing the unlimited possibilities of sport and culture. That he has teamed up with HUF, another visionary who shared these touchstones so closely, seems perfect. Over a collection of apparel, decks and accessories, Jarvis created the art based from Keith Hufnagel skate photos, a harmonious marriage that captures the essence of what made HUF so special, and what makes Jarvis an elegant ambassador. Drops June 10, 2021. hufworldwide.com

Beyond the Streets Spray Can Skate Deck It’s summer, and we encourage the kids to get out and play a little. At a distance, of course. One of our favorite pastimes is looking back on tools of the trade from generations before, and Beyond the Streets has always made a point of chronicling spray cans and paint through the decades. Through classic Rust-Oleum, Krylon and even some more obscure brands, BTS went through the collection and are releasing a new skate deck wallpapered in cans. Makes sense; the history of art from the streets for you to make your own art on the streets. Or put it on your wall… beyondthestreets.com

24 SUMMER 2021

1XRUN x Montana Cans Special Edition Spray Can At its core, 1XRUN is about encouraging and facilitating street art and graffiti cultures around the world. And of course, making it all collectible. Now we get to celebrate the Detroit print house. In commemoration of their 10-year anniversary, 1XRUN has teamed up on a collaboration with Montana Cans and Blick Art Materials for a special spray can release. The cans will be available in June at Blick stores and online at www.dickblick.com. 1xrun.com

PICTURE BOOK

26 SUMMER 2021

PICTURE BOOK

Vasantha Yogananthan A Myth of Two Souls Upon first setting foot in India at the age of 25, French photographer Vasantha Yogananthan had already determined that he would devote the next decade to creating a comprehensive photographic interpretation, resulting in seven books, in celebration of the ancient Sanskrit epic, The Ramayana. The text weaves exemplary tales of young prince Rama’s childhood, a forced exile with his wife Sita, her kidnapping by the demon Ravana, the subsequent war, and their triumphant return home to a complicated reign. The saga has maintained great importance in both religious and secular life since its origins in the 5th century BCE, the stories retold across South Asia and recounted in almost every medium, from painting, sculpture, and dance, to film, comic books, and video games. Inspired by the eclectic range of visual iterations and intrigued by the problems that storytelling presents within photography, Yogananthan sought to depict the story within images of normal daily life. “I was very much looking to find fiction within the realm of reality,” he says. “But in a sense, you’re looking for something that you will never find. You will never find fiction as-is within the reality that you’re experiencing on an everyday life basis.” In India, land informs myth, and myths inform the land. Like the millions who travel to sacred sites every year in search of meaning and understanding through experience of place, Yogananthan’s envisioning of ancient stories within the landscapes and people of presentday India led him on an unusual pilgrimage as he tracked stories of The Ramayana across the subcontinent. Deeply influenced by film, Yogananthan understood that the still image couldn’t render narrative as viscerally as cinema but was dedicated to viewing the parameters in gauging how photography might succeed in meeting such a challenge. “[That] was at the very core of the project,” he says. “It frames what you

All images: Courtesy of Vasantha Yogananthan and Assembly Above: Seven Steps, Janakpur, Nepal, 2016

can and cannot do.” Over time, such constraints led to greater experimentation. After abandoning his initial documentary-style approach, he found freedom of vision in large and medium-format cameras that required patience but fostered more intimate connections with the people and places. Recognizing that the act of shooting and the more analytical process of understanding what he was doing needed space from one another, he balanced month-long trips to India with longer periods home in the studio, continually finding ways to discover a new approach for each trip. “It was a back and forth between conceptualizing very precisely the project and the idea and then, in the field, being very loose with how I would approach the places and the people I’d meet.” Early on, he began collaborating with Jaykumar Shankar, a painter skilled in the rare art of hand-coloring black and white photographs. As Yogananthan searched for pictures lingering between fiction and reality, Shankar’s colors further imbued the scenes with an atmosphere of fantasy, the final images hovering between moments invented and moments found. In the last several books, including the final chapter, Amma, to be released this year, Yogananthan began painting and manipulating many of the images himself, diving into a world of colors, shapes, and brush strokes that fuse myth and reality. As those stories of the past are revealed within these images of the present, the future is born in the imagination. —Alex Nicholson In September 2021, Chose Commune will release the culmination of Vasantha Yogananthan’s A Myth of Two Souls, bringing together seven books and prints in a very special edition box set available exclusively through Assembly in the United States. vasanthayogananthan.com

JUXTAPOZ .COM 27

PICTURE BOOK

“The link between photography and painting was one of the first interesting parts of the project. The last eight or nine years for me were quite interesting, researching what color photography could be and the use of painting of the photographs, always looking forward to the studio process as a second look on the photographs you’re taking.”

28 SUMMER 2021

Above: Magic Fishes, Kanyakumari, Tamil Nadu, India, 2013, Black and white C-print hand-painted by Jaykumar Shankar

PICTURE BOOK

Above: Demigod, Kulasekharapatnam, Tamil Nadu, India, 2019

JUXTAPOZ .COM 29

PICTURE BOOK

30 SUMMER 2021

Above: Ghost Dog, Kulasekharapatnam, Tamil Nadu, India, 2019

PICTURE BOOK

“You leave to a place with an idea of what you’d like to shoot or what you’d like a project to be about, or to look like, and then, when you’re there, the process was to forget about that initial idea and try to be as free as possible during the picture-making process. Then, only after getting back, do you connect the dots.”

Above: Twin Wings, Valmiki Nagar, Bihar, India, 2014, Black and white C-print hand-painted by Jaykumar Shankar

JUXTAPOZ .COM 31

DESIGN

Make Do Nicole McLaughlin’s Movement For Circularity A friend slid into my DMs with a few of Nicole McLaughlin’s crafty and practical inventions, and we were instantly in love: Sharpie earrings, bread mittens, practical high heels with a built-in lint roller, a beanie made of tennis balls—the artist’s concoctions combine humor, fashion, and above all else, a lucid and lively plea for sustainability. Describing her practice, McLaughlin has a sourcing strategy: “Making do with what we have.”

You may be surprised to learn that some of her creations are made of food, which afterwards, conscientious to the core, she enjoys as a doubly sustaining meal.

What’s been the most thrilling dead stock material to work with? I'm currently collecting mini display tents, and I'm obsessed.

Kristin Farr: How do you categorize your work? Nicole McLaughlin: My work sits somewhere between design and art, but it's mainly a vehicle used to push forward a message around sustainability and upcycling.

Tell me about your workshops and movement for sustainability. Workshops are not only vital to help raise awareness around sustainability, they’re also my passion. I can't wait to be able to travel safely and start doing them again.

While a Carhartt-head or Gorp-core fan might covet her work’s singularity, McLaughlin is not focused on fashion but concerned with exploring industrial paradigm shifts. The broader field wants more, with her collaborative energy in highdemand by the brands indoctrinated in the very systems she critiques. These opportunities already demonstrate the changes she seeks.

I was marveling at your Crocs collab, and then suddenly, you were working with Hermès. Tell me about your recent brand collaborations. They range from brand partnerships to social media, magazines, to charities. I recently did an auction to raise money for Women Win and have one upcoming with JanSport to benefit the Slow Factory Foundation.

34 SUMMER 2021

What are your thoughts on how to change the future? Every little step does matter. It's just about getting everyone to take that first step. How did you engage with apparel and accessories as a kid?

DESIGN

I wasn't a sneakerhead growing up. I was more focused on the outdoors, activities, tinkering, and objects. My grandpa was an engineer, my mom is an interior designer, and my dad is a carpenter. They nurtured a greater understanding and appreciation for making, so, in turn, such objects grew into what you see now. The time I spent in my grandfather's workshop, tinkering away, laid the foundation for who I am today. It was the freedom and trust he gave me to make and explore that has helped me keep that childlike sense of wonder that I still possess. Do you consider the mass-production of any of your pieces? Mass production is tricky. I think any brand that is sustainable or trying to be sustainable struggles with numbers, production, manufacturing, resources, etc. My focus is on researching and trying to find solutions to work with what we have. Did the time spent at home during the pandemic affect your process in significant ways (besides incorporating sanitizer?) It made me more resourceful and reaffirmed my belief that I could make do with what I have.

What kind of production tools do you work with? I have a JUKI sewing machine, Global Industrial machines, a flatbed, a surger, and a lot of other things. But sometimes, I go back to where it all started—with my hot glue gun and X-Acto knife. What’s your favorite snack? Smart Foods White Cheddar Popcorn. I saw the binder of sauce packets you referenced to make the condiment shorts. Tell me more about your laboratory research tools. I get ideas from what I have. I'm fortunate to have a materials library, but I think anyone can relate when it comes to sauce packets. They've become a staple during the pandemic. Are you your own model? I am, but that's because I work alone. However, I rarely show my face; the focus should always be the work. What’s your theme song for 2021 so far?

I've been listening to Dance Gavin Dance's discography. They help keep the energy levels up. Why is humor important in life? Humor is essential. It makes things easier to digest and is a great icebreaker when delving deeper into more serious topics, like sustainability, upcycling, and waste. Are there brands you’d like to work with that you haven’t yet? I'm open to working within any industry. My goal is about circularity, and that's something all fields could benefit from. What are the steps needed to achieve circularity, and how do you build it into your process? The first step to working towards circularity is the understanding that it's not easy to achieve. It requires constant researching, resources, patience, and perseverance. However, a good first step is to be aware of your consuming habits. It's about JUXTAPOZ .COM 35

DESIGN

what you think you need versus what you have, and how to maximize the latter. My upcycling process focuses on creating circularity. I try to avoid using new materials and focus on what’s available, and create from there. I don't have to look hard for materials because what I use is often readily discarded. What concerns you most about the lack of sustainability, and how do you suggest people shift their everyday patterns? I think the main concern is the amount of waste that is still being generated and how little change is actually being implemented, knowing how rapidly climate change is happening. When it comes to consumption patterns, those habits are incredibly difficult to break. You have to start small and work your way up. We need to address the unwillingness of a lot of brands that do not speak up about sustainability. Even when they're trying to do something positive, like an eco-friendly capsule collection, they avoid making it a more significant talking point as a means of shying away from the accountability to do more within that space. But they don't realize that these are the small steps we need to achieve a better future. In these 36 SUMMER 2021

instances, I hope they understand that optimism is vital. You have to have hope in what you do and what you see, and the actions you take to achieve change. What has been your most ambitious or precarious project? The bread vest, for instance, required a lot of work. Food projects are often tricky. They have to be assembled such that I can eat them afterward, so I don't use glue. And sometimes they can take a long time to construct. I think people underestimate how much time goes into each piece. Do you keep all of your creations in an archive, or recycle them for new work? I have a few pieces that I've kept to archive, but most of my work is deconstructed almost the next day to use the materials on other projects. Have you worn any of your inventions in a practical way? I've worn some of them, but I'm pretty low-key when it comes to fashion. Do you make objects for your own house? I do make pieces to use at home, mostly furniture. nicolemclaughlin.com @nicolemclaughlin

Fill your space with authenticated, limited-edition artwork by the most exciting names in contemporary art. Join our global community of artists, curators, fans and collectors. www.1XRUN.com

INSANE51

WAYNE WHITE

BEN FROST

MR ANDRÉ

SHEEFY

FASHION

Wing Yau Earth Connection The four carved granite faces of Mount Rushmore may claim status as the world’s largest, but other forms of sculpture carry their own weight, remarkable texture, subtle meaning and private statement. Wing Yau creates moonbeams from seedlets of pearls and drops of rainbow from the confetti of opals she carefully sources. Her jewelry sculptures reflect a connection to the people and country of provenance, to her team and finally, to those who choose her pieces from Wwake to create their own expression. Gwynned Vitello: You almost made a 360, in starting art school to study sculpture and then shifting to making jewelry. What did the younger Wing Yau have in mind when enrolling at the Rhode Island School of Design? Wing Yau: This question brings back waves of nostalgia! I graduated after studying sculpture at RISD and wanted to make art in my studio—but honestly had no direction. In school we learned to weld and cast metal to make larger scale sculptures and how to make video art with equipment from the school. After graduation, it was like a plug was pulled, no studio and the tools I needed to make what I’d made before. I knew how to work with my hands, so my work shrunk and I worked out of my bedroom with textiles, clay and wax. These sculptures became wearables, then became jewelry—which I hear has been a natural transition for a lot of sculptors! Studying sculpture gave me a full understanding of the soldering process and casting within jewelry, and ultimately to become a better designer and communicator. It’s not just magic—there’s a lot of practical problem solving in building sculpture, but I think it’s fun being both problem solver and artist! How was life as an aspiring studio artist? Sculpture can be a commercial and arcane challenge, so I’d like to hear about your personal experience. I hit a wall immediately in moving back home where I had no artist community. Yes, we should make work for ourselves, but so much of my motivation was engaging with others, and I lost that and my studio when I moved. My work had to change, and I had to be okay with that. After finishing internships at NYC galleries, I ended up working as a barista, hoping to meet some “cool” artist types. Nerdy, I know, 38 SUMMER 2021

but I’d wear what I made in hopes of garnering “feedback”. Having just graduated, there was nothing to lose –– and this was my only audience! It was impactful on the work in realizing that the pieces should be smaller to be more precious, intimate and relatable. They retained an artistic element in texture and shape, but I was really invested in how familiar materials could spark inspiration and, ultimately, make a meaningful connection with others.

The delicate gold jewelry, eachpiece like a little sculpture, opened doors for me. Were there childhood and family memories that contributed to your themes and fascination with jewelry? Does this play into the name of your company? The irony is that my parents showed no interest in jewelry! We have multiple generations of immigrants, which means lots of the

Above: Wing Yau, the designer and founder of WWAKE, wearing her own designs.

FASHION

heirlooms were left behind with their former lives, so there’s really no family precedent! Most inspirational was my mom’s fantasy of becoming an anthropologist, thus her passion for collecting masks, sculptures, weavings, and sand paintings from faraway places. When I was younger, jewelry was a small way to start my own collection. Hand carved wooden earrings and homemade necklaces woven from beads were an inexpensive way to remember where I’d been. The purchase would always be a simple, meaningful memory, and so, a meaningful collection.

jewelry, not sculpture, but don’t feel comfortable buying gold rings that don’t have gemstones, feeling they lack “perceived” value. Getting that feedback was jarring, but it did make me think. I personally didn’t like wearing gemstones, so this was a real design challenge. In September 2013, I released a small fine jewelry extension featuring opals and hints of diamonds in the delicate silhouettes of my debut project that allowed the stones to sing with a clean, graphic tone. This clicked and the collection was picked up by so many stores that I was overwhelmed with orders! Everything

I design to mimic this ease. To me, WWAKE is about gestures, exploring an idea over and over, not necessarily reinventing myself, but getting deeper with every layer. Each piece is a little thought that in combination reads as a poetic whole (a collection!) The name WWAKE is a metaphor, like a wake in the body of a water where little gestures create the whole. Also, it marked the end of my studio practice as it was (awake) and so marked a new beginning (awakening). If it sounds cheesy, it felt appropriate. Maybe WWAKE is about hope and being ok with change. What was the first piece that caught on and what materials? Were you surprised at the development? My first project was called Closer, an investigation of trade materials––silk, cotton textile necklaces, bronze, silver, and bits of gold. I liked that these materials had a loose sense of history before I even manipulated them into sculpture. I was proud of that first collection, which had Sheila Hicks-inspired textile pieces, and metal bracelets that stacked and were literally embedded with my fingerprints, as well as little gold earrings and rings that captured simple shapes I made, all the materials soft and touched with respect for a tender, gestural collection. That said, stores came back and they were, like, people love the metal pieces because, well, they look like

snowballed, and though I kept experimenting, WWAKE’s fine jewelry is really what grew the brand into being identified as gemstone pieces with a careful sense of proportion. I never imagined being a fine jewelry designer, but my approach to materials is to always let the material speak for itself. Gold and gemstones have a rich history, and using these materials opened a new vista. Society values gold, so people are at ease looking at my designs and feel comfort in integrating them into their lives. That’s a really powerful thing. When I started making wearables, I was making jewelry with “non-traditional” materials and felt limited in connecting with others. I do make traditional jewelry rooted in the experimental, and it’s subtle, but I feel motivated by the very real impact it can have.

I imagine a jewelry designer working alone. Was yours a solo effort in the beginning? Oh my gosh, absolutely! I learned early on that I need time alone to incubate with my ideas. I didn’t set out to make a business or a brand; WWAKE developed naturally from my love for having a studio practice. I started WWAKE in my bedroom in 2012 and relished every minute. Mornings I would talk to store owners and do visual research online, then spend the afternoon making each piece by hand, on my own. I still love working with my hands. Before shifting gears from computer work to making pieces, I’d draw for an hour to meditate (highly recommend!) and then design late into the evening. It was the perfect artistic balance. Twice a year, I’d go to New York for bursts of social time: selling the collection to stores, meeting other designers and spending time with my longdistance boyfriend at the time. Within the year, however, all of this needed to change. No matter how much I loved making the pieces myself, it was impossible, as stores were clamoring for their orders. WWAKE grew from a one-woman show to a two-person team, and now we’re a team of 21 in the New York jewelry district. It’s wild how things change, but I’m proud that each step has been organic. I thought you started out in New York. How did you find your current space and what makes it function for you? I started WWAKE in my hometown of Vancouver, Canada. I couldn’t get a job in New York, so I went back and forth between the two cities, mostly working out of my bedroom. I don’t need an elaborate set up for my work—usually just a sketch pad, some clay for 3D sketches, and a

Lower left: The Pearl Cluster Earrings, featuring Australian opals, American River pearls, and recycled diamonds and gold. Center: A collection of opals from the designer’s mineral collection Upper right: The Small Medallion Four Stone Necklace and The Three Step Necklace

JUXTAPOZ .COM 39

FASHION

wall where I can pin my ideas. When I finally immigrated to New York and got a Brooklyn studio, I think I had four things: a single jewelry pin, a hand file, a handheld grinder from my undergrad in sculpture, and a table. It was ridiculously simple and I got a lot done with those items. Our current space was the photography studio of my dear friend and collaborator Shay Platz, who had to move out of the city soon after I arrived. I took her space, made it a home and, over time, we’ve filled it with lush greenery and mineral specimens to make it an inspiring showroom. We’ve also built out a proper jewelry studio where five jewelers work on production and samples so I can stay close to how my jewelry is made. It’s amazing to work with other jewelers, solving problems that would otherwise remain abstract, to define and maintain quality as we strengthen our designs. We keep our jewelers’ process in mind, and an in-house studio gives us control in the sourcing of materials, rather than relying on a contracted jeweler for supply. Fabled stories are attached to stones like the Star of India and Hope Diamond, as you said, we all have our own modest memories, right? What’s your philosophy about our relationship with jewelry, which might be even deeper after all this isolation? Wow, yes, exactly. We see a lot of people buy jewelry for important milestones or investment simply because the materials stand the test of time. While clothes wear down overtime, I believe jewelry wears in with memories and reminds us of who we are. I think of heirlooms as relics of time, intended to last for generations, even after we’re gone. What do we imagine the future as, though? Who are we while making the decision to commemorate ourselves with these pieces? Do you have a piece you wear everyday? Yes, our Letter Necklace. It’s like a little loom with freshwater pearls and is inspired by the textile weavings of Sheila Hicks, who was my first inspiration for WWAKE. This piece has come full circle for me. You have branched out a bit, haven’t you? Tell us about CLOSER, how it evolved and what’s different about it. CLOSER is our sister collection. I like to call it the anti-WWAKE collection because it’s large, sculptural, pieces, the opposite of WWAKE’s airy silhouettes. But it does stem from the same philosophy of exploring the material with your hands: Each piece is a sheet of silver meticulously folded by hand, with an intention like origami. Each has a careful sense of proportion, reminding 40 SUMMER 2021

me of my very first collection, rooted in tenderness and touch, so CLOSER is an homage. At first I was surprised that performance art was another focus of your undergrad, but now that we’ve talked, I realize that it’s actually an aspect of your design process. I’m really wowed that you can see that connection! My undergrad sculpture and video performance work (which should never be seen by any human ever again!) was an ongoing study of connecting with an audience through my materials. I was interested in breaking the fourth wall and having the audience fall into the piece: subjects would make eye contact

with the camera, and the voiceovers would place the viewer as director; meanwhile, video installations would live stream the viewer back into the sculpture itself. (This sounds creepy now that I write it!) I was also interested in the power dynamics between director, cast, and audience. Looking back, this was an abstraction of what I do with WWAKE—where jewelry is the connecting point. I’m very interested in the transparency of it all. I think it’s interesting to share how things come to be and invite everyone involved to participate. Visit wwake.com to learn more about WWAKE’s sustainability and sourcing.

Above: The Cloud Earrings, made with pearls grown from the last American pearl farm.

robertsprojectsla.com

FIRST PLACE

Eustache Usabimana

“From Outer Emotions to Life” $15,000 GRAND PRIZE AND $10,000 DONATION IN HIS NAME TO UNICEF

A HIGHLY CREATIVE ART CONTEST HOSTED BY

3RD PLACE Vicktor Antonov “Princess Kaguya”

2ND PLACE Cecilia Granata (Ceci) “Space Oddities”

5TH PLACE Rosenfeldtown “Galactic Beads”

4TH PLACE Jerryk Gutierrez “A Gift From Beyond”

SEE THE FINALIST GALLERY OF 150 AT

NATURALCANNABIS.COM and HIGHARTGALLERY.COM

INFLUENCES

A Remembrance of S. Clay Wilson Robert Williams on the Passing of an Underground Legend It would certainly be fitting to offer the late artist, cartoonist, painter, writer and philosopher, S. Clay Wilson the greatest respect that is due to him, his station and his many, many supporters. Having over fifty years to his credit as one of the internationally revered Zap comic book artists and underground cartoonists, he will surely be missed. With these memorial platitudes said, we can dig a little deeper into the legacy that has been left by the self-proclaimed demon draftsman of the Barbary Coast. To put it plainly, Wilson was the most overt and outrageous artist and cartoonist of the last half of the twentieth century—period! Wilson was to the narrative arts what thermonuclear explosions were to July Fourth fireworks. If you are a well-mannered 44 SUMMER 2021

artist and have been raised in a warm, caring and conscientious family environment, your demeanor might exclude you from knowledge of the likes of S. Clay Wilson. However, if your disposition has compelled you to search out more ribald visual stimuli, and you are cursed with adventurous, investigated skills, you most certainly have made the acquaintance and appreciated Wilson’s cast of imaginative cartoon characters such as The Checkered Demon, StarEyed Stella, Captain Pissgums, Ruby the Dyke, as well as an assortment of rotting punk zombies who are too inordinate to bequeath with names. It might be of interest to understand that between the late ’60s and early ’80s it has been estimated that some 400 young newsstand

All images: Courtesy of Fantagraphics Books, excerpted from the Complete Zap Book series

INFLUENCES

JUXTAPOZ .COM 45

INFLUENCES

dealers and bookstore clerks were arrested and jailed for selling underground comix—this with participating artists such as Robert Crumb, Art Speigalman, Gilbert Shelton, Spain Rodriguez, Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, myself, and of course, the eminently profane S. Clay Wilson. Many more artists were on the list but we all paled by comparison to Wilson. The movement was gigantic at the time, and Zap comix alone has issues that sold over a million print copies. Wilson boltered his own bohemian authenticity by conducting himself much like his own cartoon creations. To put it politely, he was a “recreational dissipator” with a keen proclivity for habitual drinking and drug use. His heroes were famous beat poet barflies, some with whom he collaborated, such as Charles Bukowski, William S. Burroughs, in addition to lesser luminaries. Everybody in the underground community knew Wilson personally. Many people saw him 46 SUMMER 2021

"To put it politely, he was a "recreational dissipater" for the imaginative genius he was, but a sizable amount of folks couldn’t stand him. His accident and death came as no surprise. He took a bad fall during a drinking spree, injured his head and survived in medical limbo for nearly 12 years. His beautiful and talented wife Lorraine Chamberlain remained devoted, steadfastly staying by his side until he passed away. Wilson lived in the manner in which he created— another swig is never enough! The art world owes a lot to Wilson, an enormous amount, though regrettably, the current generation of artists aren’t going to honor that debt. But I do think history will. If you are interested in more information

about Wilson and seeing his art, seek out the beautiful set of books just made available by Fantagraphic Books publishing company. This is an unequivocal must for any underground collector. You assuredly have not heard the end of this character. Good-bye, Wilson, and tell the Devil I’ll be along a little later. —Robert Williams, March 15, 2021 Fantagraphics has a selection of books and collections featuring the works of S. Clay Wilson. fantagraphics.com

TRAVEL INSIDER

Inside Out Art in Real Life in the Coachella Valley Hot, brown desert stretches into the horizon. Craggy, snow-kissed mountains jut into a blue swimming pool sky. Behind us, massive white turbines slice through the air—their rhythmic rotations kicking up dust devils that begin at our feet and waft upwards into our mouths. Hair whips in the wind, and a Jeep that matches the sky holds court in the foreground.

We are still miles from our destination—a massive, scavenger-style exhibition spread across the arid Mojave near Palm Springs, California, known as Desert X. It’s the first day of what ostensibly began as an assignment to cover the first major outdoor art exhibit since BC, but quickly turned into an adventure ignited by discovering art in unexpected places.

From another camera angle, we might have been art influencers pulling over to the “soft shoulder” (a term we’d later learn) of the road for a selfie, except that my friend Jess and I are on all fours (all eights?), chest deep in sand, shoveling out the undercarriage of her early2000s SUV like dogs digging for a bone. There is an actual dog, an 11-year-old cockapoo named Charles, inside the car looking, eyeing us with proper skepticism.

The Great Artdoors Whether you call it Land Art, Earth Art or site-specific work, art that exists outdoors is as old as time. The singular power of wide-open spaces as blank canvas has spurred countless works—entire communities, even—representing a diverse range of points on the high-low spectrum, from refined, heavily funded projects to ethereal outsider art. Examples include Robert Smithson’s seminal Spiral Jetty in Utah and

48 SUMMER 2021

Storm King Center in Upstate New York, both seminal patrons of the outdoor arts. Here in southern California, you’ll find Leonard Knight’s Salvation Mountain, Slab City’s East Jesus, Noah Purifoy’s Desert Art Museum and the Bombay Beach art community. A biennial exhibit launched in 2017, Desert X is a relatively new addition to that canon, but its third edition arrives at the beginning of an important cultural shift as most of the population has spent the better part of a year indoors surrounded by screens, internalizing a constant stream of the horrible and the beautiful. Art has not escaped the scourge of Covid’s IRL casualties. Barring an early wave of “online viewing rooms” (websites) and the occasional by-appointment gallery visit, most folks have not experienced physical art in a meaningful way since last March.

Above: Desert X installation view of Eduardo Sarabia, The Passenger. 2021. Photography by Lance Gerber. Courtesy the artist and Desert X

TRAVEL INSIDER

And now, at the exact moment the real world is beginning to open back up, the virtual world, which art lovers have been forced to consume, has reached a fascinating boiling point in the form of the $69M sale of a non-fungible token, or NFT— art that, literally, is not real. Collectively, all of these factors set the perfect stage to, well, make people want to go outside. So that’s what I did. 33.4803.3, -116.32230: Ace Hotel, Palm Springs My escapade begins on a hot Saturday morning at the Ace Hotel in Palm Springs, the official hub of Desert X, where Jess and I follow a path of pink arrows to an information booth stationed next to the bowl of hipster soup that is the swimming pool. This year’s edition, I learned, was co-curated by Neville Wakefield and César GarcíaAlvarez, and features installations by 12 artists representing 8 countries and a range of disciplines. Although more physically modest

than previous iterations, the third Desert X is special in that the organizers were able to execute a large exhibit, supporting artists in the middle of a challenging pandemic, as well as create an opportunity to view art safely and admission-free at a time when people are hungry for a shared cultural experience. “We have spent months seeing the pandemic as statistics and charts that dehumanize an embodied experience,” says García-Alvarez. “We need to have experiences that speak to our fears and desires that have shaped how we’ve navigated the past year. There are not many things that bring us closer to these big questions and to those, both like us and unlike us, than art.” Desert X began with the goal of exploring the relationship between art and the desert. But it has always been as much about the active process of viewing the work, which requires downloading an interactive app that points to each location. A scavenger hunt in the sun!

“At a time when most art institutions remain shuttered or operating at a greatly reduced capacity,” says Wakefield, “a non-prescriptive, self-guided show that occupies open spaces has allowed Desert X to be one of the first significant shows to open here in the U.S. and, for artists and audiences alike, signals a return to the kind of experiences we have all so sorely missed.” 33.775917, -116.368694: The Passenger We begin by navigating Eduardo Sarabia’s The Passenger, an arrow-tip shaped maze made from petates, rugs woven from palm fibers. The installation is inspired by a fitting trope for the first stop on a desert journey, as we’re greeted by a chatty masked docent who asks us to channel the pilgrimages our ancestors endured on the Oregon Trail as we amble through the maze “in our cute shoes with our cute dog.” Feeling dutifully respectful of our ancestors and in full agreement that Charles is very cute, we look askance at our humble, scuffy shoes and work our way to the center of the maze, where we soak up sweeping views of the desert from

Top left and right: Desert X installation view of Zahrah Alghamdi, What Lies Behind the Walls. 2021. Photography by Lance Gerber. Courtesy the artist and Desert X Bottom: Desert X installation view of Xaviera Simmons, Because You Know Ultimately We Will Band A Militia. 2021. Photography by Lance Gerber. Courtesy the artist and Desert X

JUXTAPOZ .COM 49

TRAVEL INSIDER

some bleachers and smile at a local motorcycle club gleefully posing for group photos. Coordinates Unknown: Sky Valley This brings us to the digging. What would cause someone to spend the bulk of the first day of a work assignment in a ditch on the side of a highway? It certainly made sense at the time. Who wouldn’t be curious and make a quick stop to examine a fallen, strangely beautiful turbine propeller the size of a small airplane? Unfortunately, what starts as an exercise in seeking out art in unexpected places can turn into an unsuccessful exercise in offroading. This impulse, combined with some deceivingly soft sand and a refusal to call AAA, will result in 45 minutes of digging. 33.964250, -116.484250: Morongo Valley Hot and dirty but free, we picked up some Red Vines, a bag of ranch Doritos and a roadie michelada to fuel a short drive to What Lies Behind the Walls by Saudi Arabian artist Zahrah Alghamdi. After a windy, quarter-mile hike into the desert, we’re rewarded with one of Desert X’s most impactful installations, a monolithic sculpture constructed from layers of fabric and cement that smell like dirt but look like the tower of mattresses in The Princess and the Pea. Recognizing the similarities between the California and Saudi Arabian deserts, the piece

50 SUMMER 2021

illustrates the relationship between the art and the land through a unique combination of scent, texture and ideas. It’s hard to imagine this installation existing anywhere else.

the Desert X “pit stop,” which is a Gucci- and North Face-sponsored dome minus a door, serve a valuable purpose by supporting a cultural moment, they don’t exactly feed the soul. So I stay.

34.15660549168434, -116.493103231107: Pioneertown Tired from digging, we abandon plans for a sunset session at the Integratron sound bath for more micheladas at the famous Joshua Tree watering hole, Pappy & Harriet’s. In addition to knoshing on a delicious pile of nachos, art shows up in the form of a local band and the unexpected opportunity to hear live music for the first time in over a year. After a few drinks with Jess and a few dances with Charles the dog, I return to my car and drive alone to Palm Springs just as the setting sun transforms the Joshua Trees into silhouettes.

33.822172517037764, -116.54223719952763: Downtown Palm Springs, Part II I spend the next few days trying to surrender to the journey instead of planning the destination by beginning with relocating to what seems to be the only available accommodations in Palm Springs, a Tiki-themed suite at the Caliente Tropics Hotel. Other than a sleepless night caused by a large animal under my bed that turns out to be a sprinkler hitting the side of the building, it's a lovely place to stay, particularly after 2-3 magic mushroom gummies and a dirty martini from Melvyn’s steakhouse.

33.822172517037764, -116.54223719952763: Downtown Palm Springs For the next two days, I explore Desert X alone. Standout artists include Xaviera Simmons, who created a series of billboards on Gene Autry Trail that fuse text and imagery into a challenging meditation on race. Being in the desert, while interacting with art in a community of people committed to understanding and imagination, strips away a few layers of covid debris from my psyche. But the more time I spend outdoors, the freer I want to feel. And though things like

33.92524869574892, -116.54478514971049: North Palm Springs The highlight of phase two of the adventure is a birthday celebration for my friend Steve Hash, an artist who makes beautiful sculptures of ghosts from concrete and terry cloth towels. The evening, fueled by copious amounts of tequila, includes a clever scavenger hunt led by Steve’s daughter, an impromptu jam session during which I learn to play three notes on the electric guitar, and a delicious seafood dinner, marred only by a crabclaw induced cut on my thumb.

Left top and bottom: Desert X installation view of Xaviera Simmons, Because You Know Ultimately We Will Band A Militia. 2021. Photography by Lance Gerber. Courtesy the artist and Desert X Right: Oasis of Eden Hotel, Yucca Valley, California. Photo by Liz Suman

TRAVEL INSIDER

The less I plan the trip, the more fun it becomes. The more fun it becomes, the longer I want to stay. The longer I stay, the more I realize that art experienced in this way makes me realize the important synergy of moment and place. This is true whether it's a sculpture by a blue chip artist, a living room hit with an explosion of birthday balloons after a few glasses of tequila, or the broken propeller of a turbine. 34.12013805923302, -116.43446540227208: Oasis of Eden, Yucca Valley It’s the day before I head home to Los Angeles, and a Spring Break-fueled shortage of hotel rooms in Palm Springs leads me to Yucca Valley, a partially-gentrified hipster outpost of Palm Springs located near Joshua Tree (and Pappy & Harriet’s). Specifically, to a kitschy themed hotel called the Oasis of Eden that’s exactly charming (and clean) enough to warrant a one-night stay. I am ensconced in the “Swimmers Paradise” room, where I enjoy a two-hour session in my red en suite Jacuzzi beneath a ceiling wallpapered in a cloud-speckled sky that reminds me of that first day of the Big Dig.

Above: All photos from Kenny Irwin Jr’s RoboLights by Brian Blueskye

33.83205792395526, -116.53540433296668: Robolights, Movie Colony, Palm Springs My last stop is the best. Nestled in a community of mid-century modern mansions in the Movie Colony section of Palm Springs. Robolights is the outdoor art antithesis to the polished, hypercurated Desert X. The brainchild of a primarily self-taught artist named Kenny Irwin Jr., Robolights is a sprawling compound of fantastical creations the artist began building in 1986 on the four-acre plot surrounding his childhood home. The living installation, which Irwin Jr. works on between 8-10 hours a day, consists of a dense maze of interlocking pathways bordered by artworks made from found or donated objects that he has transformed into a psychedelic Wonkaland set to a soundtrack of campy classical music. There are 50-foot-tall robots, hot pink giraffe bots, a Christmas sleigh overtaken by a deranged Easter Bunny, post-apocalyptic “nuclear elves” prancing across a tennis court, and a village made entirely from microwaves.

According to Irwin Jr., Robolights isn’t a choice. He sees his creations in his dreams, resulting in work and identity that are synonymous: “It’s physiologically intertwined in my physiology. A cat is born to meow but it doesn’t know why it’s born to meow—it just meows… I don’t really know why I was made to be an artist, I just know that I was born that way.” I learned about Robolights on a lark, from a friend of Jess’s who stopped for an impromptu hello while we were eating dinner in Palm Springs earlier in the week. I couldn’t believe I had never heard of something close by that had existed for so long. So, on my last night in the desert, I text the artist from the red jacuzzi on impulse, driven by the same question that landed Jess and me in the ditch eight days earlier. And, of course, the answer is the same anytime Irwin Jr. is asked to explain what impels his art: “Why not?” —Liz Suman

JUXTAPOZ .COM 51

IN SESSION

New York Academy of Art and the Chubb Fellowship Maud Madsen Shares her Prize “We would sometimes have summer days when it was light outside until well after 11:00 pm,” Maud Madsen recalls about growing up in the northern reaches of Edmonton, Canada, where the nearest city, Calgary, was a three-hour drive away. After an unsatisfying stint at the University of Alberta, followed by a job there as a student recruiter, Madsen decided to give herself a second chance and headed to the eastern seaboard, enrolling at the New York Academy of Art, which focuses on rigorous technical training with an emphasis on figurative and representational art. “I fell in love with the city and what the school had to offer. When I first arrived, I wanted to make work about the body and body dysmorphia. My time at the Academy had a huge impact on my work. I was constantly being pushed by advisors to consider both the formal and conceptual aspects of my work. And my peers were probably the most influential on my practice—exposing me to new artists and modes of working.” 54 SUMMER 2021

What next? There’s a shortage of de Medicis ready to support future Michangelos. And what are the chances of snagging a solo show at age 24 like Keith Haring, boosted by the patronage of the trendy Tony Shapiro gallery? As it turns out, NYAA, co-founded by artists like Andy Warhol who appreciated the school’s mission to teach traditional skills, left an endowment and maybe an inspiration for the Chubb Group, which annually offers three exceptional grad students a substantial fellowship, juried by the likes of Peter Saul and Rachel Feinstein, which includes studio space, an exhibition opportunity, access to studios, galleries and critics, as well as living expenses. One of the 2021 fellows is Maud Madsen, who described experiences, ranging from the daunting, “doing weekly critiques with first and second year students… I wanted to make it worth their time by providing thoughtful and insightful feedback,” to the surprising, when, “I didn’t realize how much I would enjoy being

a teaching assistant… it’s fun to both be able to learn alongside the students and be able to share my knowledge,” to the gratifying, citing “the dedicated studio time. I would just spend it getting better with painting and challenging myself to work larger than I was previously comfortable with. I’ve really enjoyed getting to know the other two fellows, Lydia Baker and Lujan. It’s really been helpful to navigate everything post-graduation with those ladies.” This is a great opportunity for everyone involved with NYAA, and who wouldn’t want to win a prize like this? —Gwynned Vitello Maud Madsen is currently preparing drawings and paintings for her solo project with Marianne Boesky Gallery in November, 2021. @newyorkacademyofart @maud_madsen

Above: Maud Madsen, Perky, Acrylic on linen, 40" x 30", 2020

Street Show

@brassworksgallery

@brassworksgallery

ON THE OUTSIDE

The New Vanguard The Unique History of Bristol’s Underground Culture Accessing music digitally is practically instantaneous. Not so with vinyl, which takes a minute or two as you take the record out of its sleeve, put it on a turntable, pick up the needle and cue it to listen. Often it’s the record sleeve we connect with first. Cover art offers a clue, a sign, a portent of what is to come and, for many, an element as cherished as the music it represents. I’m part of a generation that adored this side of vinyl culture. The sleeve design would often be the first place I’d engage, looking at the images adorning the store’s walls and flicking through the contents of the record shop. In the ’80s and ’90s, the DIY music scene in Bristol was synonymous with a home-grown 56 SUMMER 2021

visual culture. Countless flyers for music events, parties and jams would feature work by local street and graffiti-inspired artists. As the Bristol DJs, promoters and music fans from these events started releasing records, this relationship between image and sound, between visual artists and recording artists progressed symbiotically. During the years I was running Hombré Records, I wanted the label’s sleeve art to advance the attitude, feel and flavour of our music, just like the many record sleeves, posters, flyers and graphic art that had inspired me. “I really like the cover” was the reaction I loved hearing. I was lucky enough to have a body of artist friends to go to, so when the music started to find me,

creating the cover art was feasible too. Hombré ran from 1997 to 2005, but with Bristol being Bristol, it’s just one of many stories where audio meets visual. Spending days stage diving to Bristol bands like The Seers and distracted by the emergence of rave culture, the proliferation of Bristol Sound in the late ’80s and early ’90s largely passed me by. But as a record buyer, and native of the city, I was well informed by the art on the streets and its relationships—flyers that indicated something distinctly urban, influenced by New York hip hop, was brewing. As it came to pass, this energy joined with Bristol’s existing reggae, sound system and post-punk scenes to become globally recognised.

Above: 3D and Z Boys, Head Spin, 1983, Bristol © Beezers Photos

ON THE OUTSIDE

Seeing the video for Wishing on a Star and an interview on TV with Fresh 4 made me aware that producers in Bristol were doing something special. I’d heard The Wild Bunch play at a local skateboard park and started putting two and two together, plus my cousins, Sam and Benji Tonge (who promoted and DJ’d as Primetime) were really involved. Break looped, cover versions of songs I knew by the likes of SOS Band, Chaka Khan and Isaac Hayes became the norm. Diverse musical sources from dub, post punk, jazz and disco—music as well as lyrics—were being appropriated from the records and tracks, influencing the local scene. And the cover art was pretty good too! To my mind, the convergence of sound system culture, informed by the city’s AfroCaribbean community and events like St Paul’s Carnival, the post-Pop Group work of Mark Stewart with The Maffia, Rip Rig + Panic; then Gary Clail and DJs/producers like Milo, Nelly Hooper; Flynn from Fresh 4, and the consistent presence of Rob Smith and Ray Mighty are the antecedents. I never tire of hearing Smith & Mighty’s cover of “Walk on By” or looking at the use of bold font, black and white tone and ‘Three Stripes’ logo on the sleeve (surely referencing their sound system of the same name—as well as hip hop’s obsession with Adidas?)

to find the right way of acknowledging the Bristol flavour in it all, whilst adding to the story. Cult genre movies, like Kung fu and Westerns were always a thing back then. Banksy’s The Mild Mild West— with its desert dry sarcasm and prominent place in Bristol’s Stokes Croft area—twinned with the Wild West (of England) and cowboy signaling of The Wild Bunch, influenced me to choose the name Hombré, that and the Elmore Leonard novel, as well as Paul Newman’s film of the same name. For anyone who knows the Bristolian / West Country way of speaking—I decided an acute accent on the ‘e’ was necessary, to avoid Bristolians

pronouncing it “Hom-brurrr!” Banksy was a good friend at the time, and someone I recognised as very entrepreneurial, so I was fortunate that Riski Bizniz from One Cut was a big fan and wanted his art on the cover of their releases. Banksy would send me faxes with ideas for One Cut covers. Adorned with tongue-in-cheek comments, they would feature sharks, military vehicles, speakerboxes and megaphones. Banksy’s ongoing spirit of generosity and instinct to support Bristol makers saw him continue to supply artwork for One Cut’s Hombré releases despite becoming better known. This visual dimension to the Bristol scene kicked off around the time Banksy and Inkie—artists

Once Daddy G, Smith & Mighty and seminal singer Carlton had masterminded the first Massive Attack release, and the street art that defined the Wild Bunch aesthetic had segued into Blue Lines, it was impossible not to feel immensely proud and excited that this music had turned into something truly unique on a global scale and, best of all, was being made in my home city. Totally homegrown! A few years on, my affinity with Bristol culture was re-kindled when I started to release records under my own steam. And I knew from the outset I wanted visuals alongside the sounds. I wanted

Left: Aspects Revenge of the Nerds Design by Phil@Azlan, artwork by Mr Jago, 1999 Center: Atari Safari Bionic Genius Design by Phil@Azlan, artwork by Will Barras, 1999 Right: One Cut Records ‘Commander’. Design Phil@Azlan, artwork by Banksy, 1998 Lower right: Wall Posse B-Girl, 1986, St Pauls Carnival, Bristol. © Beezers Photos

JUXTAPOZ .COM 57

ON THE OUTSIDE