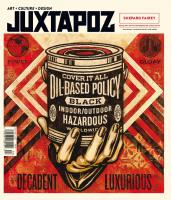

Spring 2021 Juxtapoz

146 32 57MB

English Pages [148] Year 2021

Recommend Papers

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

KAWS: WHAT PARTY is curated by Eugenie Tsai, John and Barbara Vogelstein Senior Curator, Contemporary Art, Brooklyn Museum.

Presented by

Leadership support for this exhibition is provided by the Rockefeller Brothers Fund.

KAWS (American, born 1974). WHAT PARTY, 2020. Bronze, paint. © KAWS. (Photo: Michael Biondo)

On View Now

CONTENTS

Spring 2021 ISSUE 217

32

134

The Vibrant Universe of Yinka Ilori, MBE

10

36

MADSAKI, CalderPicasso, Julie Mehretu, Ken Nwadiogbu and Tokyo Olympic Posters

Editor's Letter

14

Studio Time Ryan Travis Christian’s Suburban Oasis

18

The Report Cut and Sewn with Christopher Martin

22

Product Reviews Brian Calvin, Golden Acrylics and Yinka Ilori Homeware

24

Picture Book Khalik Allah Shows Us the Light

Design

Fashion Alexandra Sipa Crosses the Line

Events

70

Shannon T. Lewis

102

Tiffany Alfonseca

Influences

138

Tony Toscani Reflects and Dreams

Travel Insider The Illumination of Icelandic Isolation

Pop Life

78

Ania Hobson

110

Ryan Travis Christian

54

In Session A Valentine to Columbia College Chicago

56

On the Outside

Sieben on Life Six Pack with Winston Tseng

42

46

136

Openings in Uncertain Times, Part III

140

In Memoriam Robert Williams on the Passing of Van Arno

142

Perspective

86

Amoako Boafo

118

Jason Jägel on the Magic of MF Doom

En Iwamura

Helen Bur’s Lone Wolf Sunset

60

Book Reviews Ramen Forever, Bisa Butler and Miyazaki

6 SPRING 2021

94

Hernan Bas

126

Cathrin Hoffmann

Right: Art by Yusuke Hanai

62 Yusuke Hanai

STAFF

FOUNDER

PRESIDENT + PUBLISHER

ADVERTISING + SALES DIRECTOR

Robert Williams

Gwynned Vitello

Mike Stalter

EDITOR

CFO

Evan Pricco

Jeff Rafnson

ART DIRECTOR

ACCOUNTING MANAGER

Rosemary Pinkham

Kelly Ma

CHIEF TECHNICAL OFFICER

C I R C U L AT I O N C O N S U LTA N T

Nick Lattner

John Morthanos

DEPUTY EDITOR

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Kristin Farr

Sasha Bogojev Ryan Travis Christian Jewels Dodson Kristin Farr Joey Garfield Shaquille Heath Jason Jägel David Molesky Charles Moore Alex Nicholson Evan Pricco Michael Sieben Gwynned Vitello Robert Williams

[email protected]

CO-FOUNDER

Greg Escalante CO-FOUNDER

Suzanne Williams

ADVERTISING SALES

Eben Sterling A D O P E R AT I O N S M A N A G E R

Mike Breslin MARKETING

Sally Vitello MAIL ORDER + CUSTOMER SERVICE

Marsha Howard

[email protected] 415-671-2416 PRODUCT SALES MANAGER

Rick Rotsaert 415–852–4189 PRODUCT PROCUREMENT

John Dujmovic SHIPPING

Kenny Eldyba Maddie Manson Charlie Pravel Ian Seager Adam Yim

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Tiffany Alfonseca Nolis Anderson Sasha Bogojev Peter Döring Joey Garfield Cathrin Hoffmann David Molesky Jahed Quddus Silvia Ros Eric Tschernow Rio Yamamoto

TECHNICAL LIAISON

Santos Ely Agustin

Juxtapoz ISSN #1077-8411 Spring 2021 Volume 28, Number 02 Published quarterly by High Speed Productions, Inc., 1303 Underwood Ave, San Francisco, CA 94124–3308. © 2016 High Speed Productions, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in USA. Juxtapoz is a registered trademark of High Speed Productions, Inc. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission is prohibited. Opinions expressed in articles are those of the author. All rights reserved on entire contents. Advertising inquiries should be directed to: [email protected]. Subscriptions: US, $29.99 (one year, 4 issues); Canada, $75.00; Foreign, $80.00 per year. Single copy: US, $9.99; Canada, $10.99. Subscription rates given represent standard rate and should not be confused with special subscription offers advertised in the magazine. Periodicals Postage Paid at San Francisco, CA, and at additional mailing offices. Canada Post Publications Mail Agreement No. 0960055. Change of address: Allow six weeks advance notice and send old address label along with your new address. Postmaster: Send change of address to: Juxtapoz, PO Box 302, Congers, NY 10920–9714. The publishers would like to thank everyone who has furnished information and materials for this issue. Unless otherwise noted, artists featured in Juxtapoz retain copyright to their work. Every effort has been made to reach copyright owners or their representatives. The publisher will be pleased to correct any mistakes or omissions in our next issue. Juxtapoz welcomes editorial submissions; however, return postage must accompany all unsolicited manuscripts, art, drawings, and photographic materials if they are to be returned. No responsibility can be assumed for unsolicited materials. All letters will be treated as unconditionally assigned for publication and copyright purposes and subject to Juxtapoz’ right to edit and comment editorially. Juxtapoz Is Published by High Speed Productions, Inc. 415–822–3083 email to: [email protected] juxtapoz.com

8 SPRING 2021

Cover art by: Yusuke Hanai, Get Together and We Could Go Higher, Acrylic on paper, 12" x 16.1", 2020

Paco Pomet

Paco Pomet, Hesperides, 2020, Oil on canvas 130 x 170 centimeters

Beginnings April 3 - May 8, 2021

EDITOR’S LETTER

Issue N 217 O

“Shots of the scotch from out of square shot glasses // And he won’t stop ’til he got the masses // And show ’em what they know not through flows of hot molasses..” —MF Doom, “All Caps,” Madvillainy, 2004 Like many people my age, I spent the past New Year’s Eve in a state of grief. It was fascinating to watch the tributes for Daniel Dumile come forth that night; the loss of such a lyrical hip hop genius known to the world as MF Doom obviously struck a chord with a generation of artists and cultural savants. Doom was different in his avant-garde approach to storytelling, his mask rendering him identifiably non-identifiable, the superhero/supervillain persona cloaking his craft with artistic presentation. Artists gravitated to his ability to fashion the rules to create a fantasy world of new possibilities, expanding the horizons of his mastery. He gave creatives hope. That’s what made him a legend. That’s why my peers were, and are, in mourning. This is a new year, and in so many ways, it feels like a fresh start. We didn’t really get a 2020, at 10 SPRING 2021

least in the ways we thought we would. It got us thinking about the ones we lean on, those we look to for inspiration, and that is why our cover by Yusuke Hanai offers reason for hope and support. It is so clear; friends supporting each other in times of trouble. Such directness guides us in leaving the last year (or four) behind. Yusuke is a rare, humble talent who can convey truth for a collective consciousness. This Spring, our quarterly focuses on forthright honesty and a sense of possibility, from Yusuke to Chris Martin, Tiffany Alfonseca to Ryan Travis Christian. I remember the last music review I wrote for my college newspaper. It was Madvillainy, MF Doom and Madlib’s magnum opus, and I gave it a perfect five stars, pronouncing that everything had changed in the world of hip hop. It changed my life. It made me look at an art form that I loved in a new way, injecting hope for a better future for the art that so engrossed me. I want to remember that feeling—today, now—about the potential of art for both the makers and the viewers. We seem to be on the precipice of a new era, a new “Roaring

’20s” is what I heard from a friend, and now like to say to anyone who will listen, confident that this monumentally difficult period of time will usher in a wave of experimentation and creative freedom; a collective sharing of experience and ideas will wash through fine art, music and literature. I’d like to think Juxtapoz is helping to usher in a new era. Our Spring issue has a group of artists from around the world, each reminding me of those feelings I had back in 2004, from Yusuke’s cover image and the portraits of Shannon T. Lewis, to Amoako Boafo’s incredible textures and Cathrin Hoffmann’s reimagination of paint through a digital lens. The Roaring ’20s of a century ago was a time of technological and artistic change, a decade we think of as a monumental shift in the arts. May the 2020s be perceived in the same way. A legend crossed over and helped put the future into focus. Enjoy Spring 2021.

Above: Art by Yusuke Hanai, Untitled, Acrylic on canvas, 25" x 25", 2019

www.onlyny.com

STUDIO TIME

Ryan Travis Christian In the Land of Hughes My studio is in my home in the greater Chicagoland area, west of the city. Our house is tucked away in a little cul-de-sac in a small tract built in the 1970s that butts up against the Fermilab territory (Google it). It’s a nice place. Cheap, too. Ivan Albright grew up here. There’s lots of forest preserve surrounding us too, so that makes it peaceful.

14 SPRING 2021

I’ve settled into a spare room of our house for drawing purposes and work on paintings down in the garage. The drawing room is outfitted with our works on paper collection, and the walls are entirely covered floor to ceiling. There’s a drawing table obviously, a couch for visitors, and an adjacent table with a turntable, SP404, sound system and laptop. I have four windows that look out onto our street, and during the summertime, you can hear children playing outside. It’s comforting.

The garage is cold, dirty, unremarkable, and mainly used in the fair weather seasons. I spend most of my mornings having coffee, listening to music and picking away at drawings. Then I will usually head to the garage, paint throughout the day, hang out with the family, then return to drawing until bedtime. Come by if you are ever in the neighborhood. —Ryan Travis Christian Read Ryan’s full interview on page 110

Above: Photo by Joey Garfield

Sebastie

n Boilea

u (aka M r. D) @mrd198 7

JUST IMAGINE… That over 30 years, Sebastien Boileau has never stopped evolving.

By disregarding traditional ‘art rules’, Sebastien toes the line between experimentation and life experience, taking his work to the walls, streets, studio, and everywhere in between.

As we celebrate artists around the world, we’re proud to be a part of Sebastien’s creative story. Now we’re excited to see how we can be a part of yours.

REPORT

Christopher Martin The Bare and Bold Truth As a tattoo and textile artist, Christopher Martin is importantly guided by the tradition of folk art. His reverence for text, appreciation for the history of his material and careful collection of imagery are powerful reminders of how folk and outsider art traditions can be reinvented for new generations, new eras. What speaks to me about Martin’s work is the stark, blunt immediacy that challenges the weight of our world with naked solidarity. On the eve of his solo show at Hashimoto Contemporary in San Francisco, the North Carolina-born, Bay Areabased Martin talks frankly about Southern folk art traditions, race in America and exclusion within the tattoo community. Evan Pricco: I wanted to start with how and where you collect some of your imagery. There is a historical weight in the imagery, but your remix and reimagining of tapestries, banners, and sewing impart elements of folk traditions. Part of me is wondering about the genesis, but also, about where the research materials come from. Christopher Martin: Where I’m from, storytelling is a big tradition within the South. I try to capture this folklore through my art and learning more about what inclusivity means in America. By using variations of cotton in my work, both paper and fabric, I’m paying homage to the history that is connected to farming and free labor, which plays deeper into the narrative of my roots while being a free black man today. Also, music is inherently woven into our culture, so I've naturally gravitated to the blues. I love discovering stories through music because the lyrics are anecdotes of slavery and the south. I think a huge part of 2020 and the reexamination of race came from so many people discovering the nuances of racism. But you were already creating this work, which is not a reaction to 2020; happily, the audience reaction has probably evolved. Can you talk a little bit about that? How have you witnessed the response to your work? Have you ever read a book or watched a movie from an earlier place in life and have a completely different experience once you revisit it years later? That material never changes, we do. There's definitely a shift amongst black artists like myself and our audiences—such as gaining a boost 18 SPRING 2021

Above: I’ve Been Drinking Tears for Water, Cut and sewn tapestry, 41" x 75.5", 2019

REPORT

of followers on Instagram and brands wanting to collaborate more on “new” initiatives that support diversity and inclusion. Prior to the climate of 2020, I invested time creating and sharing this narrative, so it's hard to decipher if people genuinely appreciate the work I make or are just using me as a tool for validation of their agenda. I've always had this really deep love for textile art, but to be honest, it's definitely a tradition that I've had to really, really try and study. There are always amazing stories of textiles within Outsider Art, and then you have someone like Bisa Butler who is actually re-inventing quilts and their inherent stories. Where and when did

you start to feel excited about the possibilities of textiles and sewing as part of your practice? I was interested in making sustainable clothing for myself when I was in high school, and that later expanded into a homegrown brand with my Mom. I gained confidence in textiles when she gifted me my first sewing machine and taught me the basics. Before moving to California, I took the old tablecloth fabrics that were just sitting in my parents’ basement. They were a perfect size, but I didn’t know what I was going to do with them. One of my first banners was an image of a ball and chain for a group show called Black Mail

Left: If You Dont Belong Here Dont Be Long Here, Ink on paper with hand-carved wooden arrow, 42" x 91" x 33", 2020 Right: Portrait by Suzette Lee

in San Francisco. Prior to that, I never had any experience on how to actually make banners— it was instinctive, and I really enjoy the idea of layering fabric to tell a story. My banners were hitting different than my prints for a few reasons: the storage was easier to maintain because I could roll them up, the banners naturally gained more attention because of their size, plus I really enjoy seeing my work on a larger scale. And a simple question, why black and white? I love the simplicity because it's the strongest contrast while being easy on the eyes as it plays JUXTAPOZ .COM 19

REPORT

into the clash between black and white people in America. I also appreciate a strong design that is bold and graphic without any distracting colors.

an art to communication, and sometimes you just gotta tell it like it is like, “Here, let me actually spell this out for you.”

Where do these lines come from in the textbased work? Initially, it was from blues songs and documentaries, but it's evolving into everyday conversations that I hear. I’m starting to reference lines from hip hop songs these days. They still have that same oppressive feel as the blues, but more gritty and unapologetic.

There’s always a healing aspect when putting out a piece of art because a lot of me is so invested. But I think there is something special with an element of text because there’s another level of vulnerability. The messages change depending on the theme and context of the show I’m in. Every viewer has a different take-away from the quotes based on their life experience.

What is so incredible about the text work is how naked it is, if that makes sense? Like these powerful words left to just be the whole art piece. It's so damn effective. Did it take you time to realize that the words were the art? Did you feel vulnerable leaving them alone? I archive interesting quotes and phrases from conversations, books, music, etc. I usually write them down, never having any intention for them in my work. Back in 2019, my friend asked me to partake in a duo art show titled Love Letters From a Runaway Slave—this was the perfect time to use these phrases I had collected and curate them.

We can't go through an interview without talking about life in 2020. For many artists, hunkering down and working is their ideal life to begin with. But everyone is different, and America has gone through so many "lives" this year. How was it for you? With all of the calamities in the year, I was confronted with racial bullshit within the tattoo community. I left the last tattoo shop that I worked at because of a racially charged incident that originally started off problematic for other reasons. The challenges black people face in business are not unlike the problems we face in the world, period, which largely involves the constant fight for respect and equality across the board.

We can't take for granted the power that words yield. For example, we’ve seen the media twist headlines over and over again in ways that can be hurtful to our community. There is definitely

I feel blessed to now work at Tres Leches Studio, a community of like-minded creatives in the

tattoo industry. There’s an invaluable peace of mind working in a QTBIPOC space. This industry has proven time after time, that white folks in particular have invoked a lot of trauma. It’s important to detach yourself to heal and focus on your own personal growth. Black liberation has nothing to do with equality. I’m not interested in being equal with the oppressor. We need to create, build and nurture our own structures and radicalize the notion of for us, by us. The revolution starts with self, what we practice and consume and how we take care of ourselves. For the solo show at Hashimoto this spring, is this what you are working on? These conversations and dynamics? I've been building a large body of work based on African American traditional tattoo imagery for a while now with banners and flash paintings. The work for this show focuses on sailor tattoos by referencing traditional flash, dissecting it, and inserting black culture. Christopher Martin’s solo show at Hashimoto Contemporary in San Francisco will be on view from March 6—27, 2021. @chrispymartin

20 SPRING 2021

Bottom left: Hand Painted Flash, Ink on paper, 2020 Top right: A Love Deeper Than the Atlantic Ocean, Cut and sewn tapestry, 31" x 52", 2018

REVIEWS

Things We Are After Chromatic Cravings

Yinka Ilori Homeware Collection Yinka Ilori’s new homewares collection transcends design symbolism to tell a story, in this case, the story of London’s Royal Docks and its import history with products like pineapples and rum from the Caribbean. In the exquisite Tibetan wool rug, an Ope (pineapple in the Nigerian Yoruba language) flourishes, and in the Omi (water) cushion, flow the wavy blue lines of the River Thames. You can learn more about the inspiration on page 32 in our design feature, and about Yinka, who reflects, “It’s weird having my homewares at home!” He goes on to express his hope that the collection brings a moment of joy and happiness. Mission accomplished. yinkailori.com

Meet Brian Calvin Project By AllRightsReserved “I firmly believe that artists don't need to deal with things directly to create these pathways for people to imagine a world that's more like what they want,” Brian Calvin told us, and this bares fruit in his first limited bronze sculpture in partnership with AllRightsReserved’s MEET PROJECT. Calvin’s paintings often germinate with an eye or mouth, blooming into fantasy images that frequently portray women. Luminous colors, springing from his California roots, dominate the Plant Life sculpture, where Calvin fuses eye and mouth, abstraction and figuration, to create a heavenly hybrid. ddtstore.com

22 SPRING 2021

SoFlat Matte Acrylic Colors by GOLDEN Most of us have settled in quite comfortably, nesting within our studios to do some solid work, and it appears there may be a few more months of such solo, uninterrupted experimentation. That means sourcing new materials, and a lot of creative friends have been raving about SoFlat Matte Acrylic Colors by GOLDEN, a paint that helps artists create immersive fields of color without the distraction of texture and glare. Maxing a pure color effect and perfect leveling is mandatory for so many painters, and this is the absolute top of the game. goldenpaints.com

PICTURE BOOK

Khalik Allah Showing Us the Light For Khalik Allah, photography is a spiritual endeavor, a conscious marriage of street and self, a quest to elevate both. It is also inherently lyrical, and like a preacher improvising a sermon, a musician in the zone, or poet freestyling off the dome, there’s something mystical and transcendent in the execution. That’s not to say it isn’t firmly grounded in this reality, in the actuality of life at 125th and Lexington in Harlem where much of his work is focused. Cycles of addiction, poverty, and suffering haunt the darkness of this nightscape but the camera is an instrument beholden to the light. Allah has referred to what he does as “camera ministry,” and he applies the salve literally, ushering people out of the shadows and into the light to take a portrait. “When you focus on the light in another, you reinforce it in yourself,” he explains. “And really, that's what I'm striving to do. I'm trying to reinforce my own knowledge of self, which is essentially light. Spirit is light.” He is a filmmaker as well, practicing his craft in a manner inseparable from his photography. Watching his films is a dreamlike experience delivered in part by an audio track divorced from the visuals. The effect is initially disorienting but serves to sharpen focus on the images and sounds in a way it could not effect otherwise. Unable to assign words to faces, the anonymity of the deeply personal conversations takes on the shape of shared experience, and separated from the aural, the visual is heightened in style and effect, akin to spending time with a photograph. Allah’s voice from behind the camera becomes a signature presence as he guides us through the streets. Engaging with new and familiar faces, we listen as he experiments, teaches, learns and reflects. Process becomes product, and where the artist begins and the work ends are almost indistinguishable. “I believe that the art is equally about the artist as it is about what the artist is depicting. This practice of photography has a lot to do with perception. It's not an objective practice… and I'm about being real and allowing people to understand me.” Allah is self taught and builds from personal experience. Every interaction is an opportunity for knowledge. In one of his earliest films, Urban Rashomon (2013), he introduces us to Frenchie, a mentally ill man who becomes a friend and continual subject. At this particular moment, Frenchie is high on K2 (synthetic marijuana), making incoherent noises, drooling to the ground, and posing for Allah’s camera. The scene is uncomfortable and feels a little problematic. But as the film proceeds, and even more so in its follow up, Antonyms of Beauty (2013), he explores an evolving, personal relationship, creating a complex portrait of a man most of us might choose to walk past. Their bond deepens, and as Allah’s practice matures, he lays bare the human habit of conscious and unconscious tendencies towards judgment and bias. “We’re not these bodies that we inhabit,” says Allah. “But my goal as a photographer is to go beyond that. I'm trying to take images like psychic x-rays. I'm trying to deliver a person's soul. I'm trying to go beyond just the physical and I think that all good photography does that.” —Alex Nicholson Khalik Allah is a Magnum nominee and is represented by Gitterman Gallery in New York. His films Urban Rashomon, Antonyms of Beauty, Field Niggas, and Black Mother are available to stream on the Criterion Channel. His latest, IWOW (I Walk on Water), will be released this Spring. khalikallah.com

24 SPRING 2021

PICTURE BOOK

All images: © Khalik Allah/Magnum Photos, courtesy Gitterman Gallery Above: Sapphire, Lexington Avenue, 2014

JUXTAPOZ .COM 25

PICTURE BOOK

Dialogue from the film Field Niggas (2015) Woman: [Referencing the camera] “Can I ask you a question... without this?” Allah: “Nah, this is me. Come on, you know you can open up to me." Woman: “Do I look alright?” Allah: “Listen, you look like you could be doing a little better, know what I’m saying? You look

26 SPRING 2021

like this. It doesn’t matter how the fuck you look because I’m seeing you behind the body. You gotta remember one thing, you’re not the body.” Woman: “What do you see?” Allah: “I see light. And that’s the truth about you. That’s the truth about me.”

Above: Frenchie, 4-5-6 Station, 125th Street, 2014

PICTURE BOOK

Top: Untitled, Lexington Avenue, 2019 Bottom: Untitled, 125th Street, 2018

JUXTAPOZ .COM 27

PICTURE BOOK

28 SPRING 2021

Top: Untitled, 125th Street, 2019 Bottom: Untitled, 125th Street, 2014

PICTURE BOOK

“What I want to do is help the world to be a kinder place. And also to dismiss the illusion that these black neighborhoods ought to be feared. These are the most brutalized and the most depressed neighborhoods, and the people, even after having gone through these things, are still full of love. You always got knuckleheads and you’ve got people that are into some nonsense, but the average person just wants to live and be happy, you know?”

Above: Frenchie with Hoodie, 2013

JUXTAPOZ .COM 29

DESIGN

Yinka Ilori, MBE Bow Down, Regardless Yinka Ilori’s eye-vibing public installations caught the attention of Her Majesty The Queen this year. She bestowed upon him the elusive title of MBE, a high-ranking award for outstanding achievements and lasting impact, remarkable for a millennial presenting critique of the same monarchy officially crowning him a Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire. Pay attention. You are now in the presence of—His Excellency.

Did she notify you by phone? I got an email from the government or Royal Family team, asking to confirm it was me, mentioning something special they wanted to give me. I thought, gosh, have I paid my taxes? I responded saying, “Yes, I’m Yinka,” and then they went quiet for about two weeks, so I called and asked them if I was in any trouble. They said, “No, no, it’s good news. Please wait.” And then I got their next email and thought, bloody hell, an MBE? Pretty nice.

Kristin Farr: Hello, Chairman, MBE. How must I now address you? Yinka Ilori: [Laughing] I’m just a local lad, you know? I’m the same person. I’m more excited about meeting the Queen. I get to go to Buckingham Palace. When the Queen gives you the award, you can’t turn your back as you walk away. I’ve got to remember that, you know? I’m forgetful. I might take the medal and run. So many rules!

And well-deserved. Your friend, another Yinka [Shonibare], also an MBE, has spoken about the irony of receiving the award from the very empire he’s scrutinizing. [Laughing] His work talks a lot about the monarchy and post-colonialism and stuff like that.

32 SPRING 2021

Yours, too. Yeah. It’s a weird one. I got a lot of mixed reviews

from people wondering if I’d take the award, since many artists and musicians have turned it down. I was of two minds when I found out, and the first people I told were my family, who were extremely excited. Growing up where I did, in Islington, North London, there was no one with a title like MBE or OBE, or any Sirs. I think of my parents and their journey, where they’ve come from and what they gave up. I had to think of the bigger picture. I hope it paves ways, or provides inspiration for the next generation of young black kids who look like me. That, to me, is very, very important. I will always talk about my culture and identity in my work, and that’s not going to change, with or without an MBE. There is some talk about changing the “empire” bit to something else—just take out the word empire, you know? The empire has done a lot of painful stuff, and I try to talk about these things in my work; subjects that are awkward, or painful

DESIGN

to speak about, but turn them into positivity and celebrate my culture—whether it’s being British, or a Black British, or being proud to be a Black African. When I was young, being Nigerian wasn’t cool or celebrated. No one wanted to be African. So, when I have an opportunity to celebrate my blackness, every day, I am going to do that. The media and society portray Africa as full of corruption and poverty, but they never want to show the goodness and beauty of the continent and what is there—culture, sunshine, beautiful people, so much heritage and things I discover when I travel to Nigeria. Growing up, it felt like when you were outside of your house, you were British, and when you were at home, you’re Nigerian. You couldn’t celebrate both; there was no middle meeting point. It was one or the other at certain times. We were lucky because my mom and dad made sure we knew who we were and where we came from. We ate

Nigerian food and they’d speak to us in Yoruba. I’m always grateful. They’d say, “We don’t care if you’re born here. You’re Nigerian and that’s it.”

the anger into my work and celebrate my culture as much as I can, and I do it in a way that’s very unapologetic. It’s who I am.

When did you first travel to Nigeria? I was 10 or 11 years old, and it was my parents’ first time back after being in London for so long, this time with their children, and taking us to see their parents, nephews, cousins, and other family. It was quite a special moment.

Unapologetically bold. Tell me about the names of the designs in your new collection. I’ve got a huge archive of patterns I’ve created over the years, through travel, just walking around London or talking to people. I’m always taking stuff into my head and then putting it into sketches and patterns. This collection was inspired by my visit to London City Airport, and its history of the Royal Docks, and what it was used for in those times. It was a place where people imported things like rum from the Caribbean, or elephants for circus fairs, that kind of thing.

They had left somewhere they’d known their whole life to start a family in an unfamiliar place, which is new and scary, and I’m grateful. When the BLM movement happened recently, my mom told me about moving to London, and how she and my brother went to view an available house. When they arrived, the person told them no Blacks were allowed and shut the door on them. When you hear those stories and know what they’ve been through, it makes you angry. I pour

Looking back at that, and knowing Britain wasn’t built by just Brits alone, but by all different people and cultures, I was looking at the cultural exchange that the British people have with other countries. JUXTAPOZ .COM 33

DESIGN

The print that’s called Omi Omi means “water, water.” The blue squiggly lines represent the Thames and the water surrounding the Royal Docks. There’s an oval shape mimicking rum barrels that came from the Caribbean, through the Royal Docks and were sold here in the UK. There is always a message, meaning and story behind my work. I noticed another abstracted symbol in the rug… The pineapple. Yes! It comes from the Royal Docks shipping in fruit and veg from different countries, like bananas and pineapples, because we can’t grow those here, can we? No, we can’t! Ope means pineapple, and is again paying homage to everything that is imported from different parts of the world. You sourced Dutch Wax print fabric in your early work, and the story of that textile industry is such a cultural phenomenon. It was a huge part of my upbringing and it wasn’t until Uni that I discovered it’s not from Africa. It’s produced in The Netherlands by a company called Vlisco, but they make their money off West Africa— Nigeria, Ghana—they are the biggest consumers and buyers. When I discovered that, I thought, bloody hell, this is crazy. There’s no link between them at all, but Vlisco is making money off my peeps, you know? But I also love the fact that Nigerians made it their own. It was something they could identify with West Afridan culture. At a wedding or church service, or any special occasion, people wore it as a collective. It allowed them to take over public space, in halls, or churches or corner shops, and when they walked in, people were already wanting to speak to them and engage with their culture, and understand what they’re wearing and why. I love that fabric can give people a sense of belonging, and that’s what the prints did. I identify Dutch Wax prints with happy memories and positive times within my life. The prints have meanings and messages, and it’s powerful that fabrics can talk to you; there is a hidden message in those textiles that can be found without even speaking to the person wearing it. Not a lot of people are aware of the Dutch Wax history, and it’s messy, so that’s why I’m trying to design my own prints now, and tell my own story. People have been asking to buy my textiles by the meter, so that’s something I might do next year. It’s worth noting that Vlisco originally appropriated their style from Indonesian designers, so the plot is thick. From you, 34 SPRING 2021

I learned about Swiss Voile lace, a textile detailed for the Gods. Swiss Voile lace is crazy. When we were young, my mom and dad would have friends come ’round and sell them the lace from Switzerland, or the best jewelry from Dubai. Socializing was quite a big thing for my parents, and all the men wanted their wives to be to have the best Swiss Voile lace or the 24 karat gold from Dubai. It was really a serious thing, going to a party, because everyone wanted to be the best, and they’d spend 800 quid on the 6-yard Swiss Voile lace with amazing weaves and really small diamantes all over, so that when the camera guy shines his light, you’re blinging. It’s a proper, proper thing. An early career catalyst was the discarded chairs you would find and redesign, the reason you’re the self-described Chairman. I noticed some had their backrests removed, and I know each chair is a story about a person you know... The chairs started in Uni and paved the way for my career to move into design. I was the guy who loves and collects chairs, and “re-loves” them, and tries to tell a narrative within them. Most of the chairs do have backrests, and all have their own parable narrative. One from the If Chairs Could Talk collection speaks of this young guy I went to school with. He didn’t really have a backbone. He

was always the person who could never say no, and found himself in a lot of trouble when he was always saying yes because he wanted to fit in. The backrest is there, but in a position that isn’t really comfortable. The chairs have common themes about identity, culture, hierarchy and status, and they’re embedded with a parable. You need to read the parable over and over to understand the messages, just like a book, even though some are only one sentence. They come from my parents, who told them to us growing up. With the chairs, what I tried to do was ease the audience into my work and world with the colors and patterns, so the first thing they’d do is smile. And that makes them feel more comfortable, and then, when they understand the parable, that’s where the idea and thought process of the chair’s meaning comes through. It’s a bit more than a colorful chair. It has a message and meaning. For me, the first thing is to engage with an automatic smile, where you’re smiling without even knowing it. It’s like when you’re on the bus and you laugh to yourself. We’ve all done it. You’re not going mad, even if people might think you are. And that’s what my work does to you. yinkailori.com

Introducing SoFlat, a paint that helps artists create immersive fields of color without the distraction of texture and glare. The paint has a flowing consistency, offering exceptional coverage and a leveling capability as it dries. This unique combination of qualities can only be found in SoFlat Matte Acrylic Colors. Learn more at goldenSoFlat.com.

©2021 Golden Artist Colors, Inc., 188 Bell Road, New Berlin, NY

FASHION

Alexandra Sipa Through the Wire Encountering a spring-loaded tangle of wires, the most productive performance I can achieve is shoving the curly mass back into a cavity with hopes it stays out of sight. Where most see snakes on a plane, Alexandra Sipa envisions purpose and possibility. What she makes is repurposed, beautiful, a blend of old and new. All the good stuff. Gwynned Vitello: Central Saint Martins in London is such a highly regarded school. What were your expectations when you were accepted? Is your current work a departure from what you first had in mind? Alexandra Sipa: I wanted to go to CSM since I was 12 but, at the time, was attending an arts-focused high school in Bucharest, Romania. Going abroad to study was a big financial commitment and risk, especially with the job insecurity in creative fields. However, when I learned about CSM, I knew it offered the best education and environment possible to achieve my dreams. I wanted to go desperately. So much has happened over the last four years at Saint Martins that I could not have imagined. 36 SPRING 2021

What makes this school so special is the unique mix of people, personalities and backgrounds. The most important thing we learn at CSM is that to succeed in this industry and in life you need to value yourself—where you come from, who you are, and what you do. Attitude, social structure, ambience—how was the adjustment moving to London? I used to be very shy, so my first year was tough. I already knew English, but it’s one thing to be textbook fluent and another to effortlessly express your personality in a second language. It’s almost like I had to get to know myself again in a different language. Things got easier after the first few months. I was lucky to meet some amazing people who made me feel at home. It also helped when I finally was able to understand British accents! When you hatched the idea for lace wiring, were your family and teachers surprised or skeptical, or was something so novel kind of expected of you? It’s funny you ask because my tutors were in

complete disagreement. When I first started making the waste wire lace, one of them really loved the idea and encouraged it wholeheartedly, while the other was skeptical and not convinced. That was my second year before interning in the industry. When I returned in 12 months for the final year, my unconvinced tutor slowly warmed to the idea, as I had improved and refined it. That’s the great thing about having two opposing perspectives: one to push and challenge me to make my ideas better and someone supportive no matter what. I’m incredibly grateful to have been taught by Anna-Nicole Ziesche and Heather Sproat, the two BA Womenswear tutors at CSM. Once you latched on to the idea, what was most challenging about actually producing a garment? What properties of the material are difficult and which are inherently advantageous? The time-intensive nature of the lacing process was initially most challenging; however, I soon became more efficient, and making the lace became second nature. The process feels meditative now. After mastering the fundamental

Above: Alexandra Șipa wearing Lace Rings, Photo by Lucas Roth Baker

FASHION

lace stitch and technique, finishing the wire garments to a luxury standard is the difficult part, and it varies from piece to piece. For example, for the A-line lace dress from my graduate collection, I adapted the Romanian tech nique of point lace to finish the entire bottom, hiding any loose wiring and creating decorative oval petals. The challenge is to find aesthetic solutions to practical issues so it is wearable, comfortable, and beautiful. The lace dress has taken the longest of the pieces so far, about 1000 hours across a few months. Unless deliberately undone stitch-by-stitch or cut with scissors, the wire lace textile is essentially indestructible, and including the dress and ruffle coat, can be folded, bent, or reshaped, yet easily molded back to its original shape. What did the first design look like, and was it easy to proceed to the next shape or type of garment? The first time I tried making a garment out of wires, three years ago, was not what I imagined at all. It didn’t look polished or close enough to a lace fabric, but I really loved doing it and saw potential.

Above: Front and back of Discarded Electrical Wires Lace Dress

When I decided to revisit the wire lace idea during my final year, it took a lot of additional research and practice to get the wires to mimic the softness of traditional lace. The techniques I use are part YouTube, books, and happy accidents, but my lacemaking dexterity improved in a few months. As with sewing a garment made out of fabric, I began to create a “sewing plan” for each wire lace garment made, starting with the lace dress at the beginning of my final year. I consider everything: the direction of the lace, where it starts and ends, how to make it comfortable and easy to wear, whether finishings will be hidden or part of the design. It all impacts how the garment will look and feel in the end. I tend to be pretty impatient, so this collection really forced me to rein it in and be organized. If I see a mass of wire or tangled chains, I shudder and go into a panic. What is your process, starting with collecting the components and then making something? Do you have a piece or shape in mind, and can you complete a garment on your own? Ha ha, my boyfriend, Lucas Baker, has the same

reaction. When we buy or collect discarded wires, we try to get as much as we can carry, especially during the pandemic with the sporadic lockdowns. So we almost always have a substantial amount of wire in our flat ready for new projects. Since I began experimenting with my wire lace technique three years ago, I've sourced the majority of my wires from an electronic waste recycling center in East London and also from my uncle's construction sites in London and around my mom's home in Bucharest. I know exactly what I’m making before I begin a piece, usually sketching it and deciding the colors first. As I can’t cut it up or unravel it when it’s finished, I must be very precise when I start. I make patterns for each piece, just as for fabric garments, and I stick to them very closely. Each has different challenges, so it’s a process of constant design problem-solving when I try something new. I’ve completed all of the wire lace garments so far without professional help. Lucas, who is also my business and creative partner, and my mother both

JUXTAPOZ .COM 37

FASHION

assisted in making the wire lace in Spring 2020; however, I make the majority of the lace by hand without any machines.

colors are twisted together evenly in the electric cables, brown and white wires remained unused after the dress was finished. I made the lace ruffle coat next, using almost exclusively brown and

I wonder what it feels like against the skin. As long as all wire ends start and finish purposefully to avoid direct contact with the skin, the garments are very smooth and comfortable, which is very important. For example, the wire lace bras are very pleasant to wear, even on bare skin, despite maybe appearing uncomfortable. The lace feels plasticky against the skin and almost like soft armor. How does color play into your creations? Does it dictate what you make? I’m very inspired by my grandma’s home in Bacau, Romania. It is such a creative, colorful place. Every time I visit, there’s something changed around the house, something moved or repainted. Her faded, painted fence with endless colors revealed through the cracks inspires the painterly way I combine colors in my wire lace pieces. For my graduate collection, my color choices were motivated equally by aesthetics and the pursuit of wasting as little as possible. I first made the A-line lace dress, my dream dress, bright and colorful, a nod to its feminine, playful silhouette. As all

trash and completely altering a material’s purpose. I think it’s more interesting to create beautiful clothes out of the unordinary. It forces consumers and those uninterested in fashion to reconsider repurposing in their careers and everyday lives. I hope to inspire people to explore ways to address other types of waste through design. I’ll keep experimenting with how far I can take the electrical wires lace textile, looking into producing it with a machine and further expanding its application beyond garments. I really want to explore more techniques and dive into the craft fully.

white wires for a subdued colorway reflective of the powerful, almost intimidating silhouette of the coat. Nevertheless, the colors of wires I have do not dictate what I make. Has working with wire inspired you to craft with other unexpected materials? Yes! I definitely plan to upcycle more alternative materials. I like the idea of creating luxury out of

How often do you go back home to Romania, and does its history and culture influence your designs? I usually go home a few times a year, but with the pandemic, I only went during the summer when cases were low in Europe. I really wanted to spend a few weeks during Christmas, but flights were cancelled when cases skyrocketed because of the new variant. I plan to split my time between Romania and the UK, producing collections and pieces in Romania In my work, I look at contemporary Romanian culture, trying to show a very specific perspective and humor, rather than something traditional. I really wanted to show the subtleties that people who grew up in Romania recognize instantly. I am really inspired by the contrast between heightened austerity and extreme femininity in Romania. The aesthetic of Bucharest is a mix of French architecture, grey Brutalist apartments, and mega Communist structures, like the Palace of Parliament. The women are usually very careful about appearance, getting all dressed up for a supermarket trip and loving an ultra glamorous, feminine look. The materials in my graduate collection connect to things that I love or bring joy. The wire garments, featuring Romanian lace techniques and motifs inspired by my grandma’s doilies and tablecloths, look like her faded fence with endless colors revealed through the cracks. Beach towels, typically found for sale on sides of the road and seen on truck drivers’ seats, remind me of Romanian humor and kitschy Eurotrash songs that make me laugh; and the fabrics from Bacau are reminiscent of the love I always find there. Most of the fabrics I use have a Romanian attitude—nonchalant, humorous, adaptable. Since you embrace kitsch as a favorite expression of art, it’s fair to say that you like fashion to be fanciful and playful, right? Yes, I absolutely love fashion for its whimsy, although I also like it to be sexy sometimes, eerie other times. I’m young and still learning what

38 SPRING 2021

Top center: Blooming Flower Stud Earrings Left: Making of Discarded Electrical Wires Lace Vest

FASHION

I like, but I think great designers are capable of doing all of the above, which is what I aspire to. Your accessories are a lot of fun. What accent piece did you make first, and what else are you planning? The first accessory I made was a four-finger massive wire lace ring. It was beautiful but not the most practical! I think almost anything can be made out of the wire lace textile, so I have lots of small pieces in mind, including bags, necklaces, and earrings. On the flip side, sustainability is not a frivolous topic, and you’ve addressed issues of waste, but also about the sustainability of workers. Explain how your process takes ethical matters into consideration? By using discarded wires, my practice inherently offers opportunities to consider and improve multiple aspects of sustainability, namely economic and social factors. Because the material is upcycled, its cost is very low, the bulk of spending can shift to the production workers, in my case, the lacemaker. Therefore, workers can receive most of the profits from the sales. Fashion needs to become more sustainable from the inside out, not only in the materials but also in ethical treatment and compensation for workers in the production and design chain. Now, it’s just Lucas and me, but hopefully, we’ll be able to hire full-time lacemakers and expand our artisanal team soon. Waste should be seen as an opportunity to discover new techniques. As my practice is rooted in creating luxury products out of local waste sources, my collection tackled one of the fastest growing sources in electronic waste, which amounted to 50 million tons in 2020. We hope to inspire and drive change through creativity and ingenuity Sustainability is simply about having compassion for yourself and others, within and outside of one’s community, and for future generations. There are less wasteful and harmful alternatives to so many of life’s pleasures that people continue to ignore or delay. Beautiful art and fashion does not need to be created as we always have; change is possible and necessary. Between E-commerce and covid, the fashion industry is operating in a new landscape. What other changes and challenges do you see overall, and any particular to what you want to do? On increasingly larger scales, sustainability will continue to grow at a rapid pace. The industry is aware of the urgency for change due to the climate emergency and the increasing demand from consumers for more sustainable options and transparency. Companies are beginning to recognize the business opportunity in a circular

Above: Discarded Electrical Wires Lace Ruffle Coat

fashion industry. Three out of five clothing items, or over one hundred billion US dollars of fashion textile material, goes to landfills every year. This is a major opportunity. Nevertheless, sustainable consumption is the most significant factor when it comes to creating a more sustainable industry, which, in many ways, is evolving far more quickly than sustainable production innovations. The secondhand clothing market and rental services are growing rapidly. As I did in my graduate collection, Lucas and I will continue to source secondhand and vintage

clothing to upcycle it into new, innovative garments for upcoming collections. Since your work is inherently sculptural, do you ever think of making purely conceptual pieces? You’re so young, there are a lot of life strands ahead of you. Definitely! I am currently working on a few projects that are just that. The beauty of this waste wire lace technique is that it allows us to explore other areas beyond fashion, like product and interior design. alexandrasipa.com

JUXTAPOZ .COM 39

@brassworksgallery

@brassworksgallery

1127 SE 10th Ave • Suite 220 • Portland OR 97214

INFLUENCES

Tony Toscani What a Day for a Daydream “I need to put everything on hold for about a year,” Tony Toscani told me when we met at his Brooklyn studio early in 2020 and talked about life, art practice, and plans for the future. After cleaning the cyber dust from that conversation, put on hold like so many in 2020, we started looking back at Tony’s work and how his engrossed characters feel so relevant, his solitary “daydreamers” more relatable. Distanced from anyone in their proximity or captured alone at an unspecified location, their distractions consume them to the point of being subsumed by their bodies, heads literally lost in thought. While we did enjoy visiting their melancholic vibe back in the day, the images now resonate with a whole new level of touching intensity. Sasha Bogojev: I want to start off with the limbs… Tony Toscani: How they’re exaggerated and such? Well, I think at first it was definitely not planned.

42 SPRING 2021

A serendipitous mistake? It was kind of like a mistake, but more like a technical decision. I used to be way faster than I am now at painting. I slowed down a lot, but when I was really fast, I would kind of find an image and then work it out. I got really attracted by these tiny head figures because it really related to our current time where people are just kind of distracted a lot. They tend to be more distracted by phones or media or peer pressure, or try to fit into some social clique. So, people started using their awareness a lot less and their bodies a lot more because they still had to go on doing normal things in their everyday life, like going to the bathroom, eating, working, and sleeping. So, to me, it’s kind of like the human evolution in 2000 years, what we would all end up looking like. Yeah, I was going to call it an “alternative evolution.”

Right, and that’s why they tend to look like giants, as well. So, when I was working with that fast technique, it started building on this quirk of exaggerated limbs and these tiny heads. Which was funny because, I didn’t know, but a lot of people started emailing me and telling me that that’s a syndrome that a lot of people actually had. They kind of are in a state where they see their limbs extend more than they actually are. It’s called Alice in Wonderland syndrome. But I never knew this and I just recently found that out and it just came from my quirk of doing a fast technique that spiraled into a concept. The characters seem to be fashioned in a simplified way in terms of the spaces and the outfits they’re in. Is that on purpose? I think I’m trying really hard not to be too detailed in the sense that this is a specific person, or a specific place. I don’t want to say this is New York or

Above: Portrait by Sasha Bogojev

INFLUENCES

this is America. It could be anywhere in the world and anybody. They are meant to look average. What about the concept of time? I don’t think time really applies because it could be hundreds of years ago. Some things like a phone end up in an image, but I don’t really put details into the phone, because I don’t want it to be too stuck in a specific time. I don’t want it to have an iPhone symbol or anything like that, but have it just be a black brick. Same with the coffee mugs and computers. I don’t want to give people too many exact answers that they need to follow. I want them to have their own idea of what it could be. Whatever they can relate to, they can put it in that place, whether it is a book or something else. And what type of emotion do you think of when you make the work?

Well, our current state of melancholy and apathy is my biggest influence. I actually call these guys the “Daydreamers.” They are kind of a metaphor for our society. How we see ourselves in real life. Not how we imagine ourselves, like through social media. In reality, we are all united by our melancholy. Are you working from reference photos or do you have people model for your work? I use myself as a model at times. They all kind of have my face a little bit. Even the women, since I am a Mediterranean-looking person who’s white or beige-ish. But that’s only because I don’t know how to paint figures that well. So I have to kind of look at myself and see how my shadows look and how my fingers look, what color I should use and whatnot. That’s the reason why they look the way they do, because I don’t look at any pictures, or

Left: Extension, Oil on linen, 14" x 28", 2018 Right: Melancholy, Oil on linen, 24" x 30", 2018

print out any images or that kind of stuff. I have to use myself, look at myself in a mirror or something. And when you compose them, when you put them in these positions, is it derived from any particular references? No, most of the time I draw from my imagination, like a rough stick figure, and then it gets limbs, and it gets a head, and, once I rework that drawing over and over and over, then I transpose it onto a canvas. That canvas sometimes changes or it doesn’t change. But, roughly, that is the kind of drawing I come up with in my head, because these aren’t exactly fixed to places. They kind of have places; for example, this one reminds me a lot of where I grew up, with trees in the background behind a lake. And this is kind of like the gallery that I work at, but it’s very rough. I try not to show JUXTAPOZ .COM 43

INFLUENCES

44 SPRING 2021

Above: Social Anxiety, Oil on linen, 38" x 46", 2019

INFLUENCES

any details. Even with windows, you just see a blue space. No bars or anything, mostly because I don’t really have anything to reference. It’s too difficult to try and be realistic. That is why I like them to be more of a representation of that thing rather than being realistic. Apparently, for you, the process is as important as the result because you’re constantly developing technique and developing yourself. All the time. I feel like every painting has a slightly different technique. Is that satisfying or does it get frustrating? It’s always frustrating. It’s never exactly what I want it to be, but I have come to this agreement with myself that if it’s at least 70% or 80% of what I want, that’s enough for me. But it doesn’t always work out that way. I used to make a painting every day, one painting a day because I was really fast. And now it takes me about a month just to finish one work. Do you need a lot of focus when you work, and how does that work since you share the workspace with your wife, Adehla Lee? With these works, I do. My wife and I figured out a way. It was really difficult at first, but we somehow manage. We actually met at grad school. We went to grad school in New York at SVA, the School of Visual Arts, and our studios were completely separate. Even though you were in a place with 10 other studios around you, no one really bothers you. So, in a way, we’re kind of used to it now. And then when we moved in together, it was just hard because our studio was also our home, so we also had to figure out our eating situation, our cleaning situation and so on. But we have a rhythm down now and it works out perfectly. It doesn’t sound like there are podcasts, reruns of shows or favorite movies in the background for you? No, this is the most active it gets—my little ambient compositions and stuff. Adehla sometimes turns on podcasts, but not when she’s really focused, it’s more like when she’s drawing or sketching out something. But when she’s focused, it’s curtains closed, completely locked into the place, and at six o’clock—it’s dinner. And do you collaborate? Not in a sense that you work together, but do you give suggestions to each other? All the time. We talk about art all the time. Every day. Does it get spicy? At times, but in a good way. I feel like she’s always been my best teacher. I always realized

Above Couple In Bed, Oil on linen, 20" x 20", 2019

the parts of me that I have to fix, and her getting spicy or something like that is a perfect way of seeing what’s wrong with my work, or what’s wrong with how I see something. Because, when I first started painting, I was, in a way, very ignorant. I used to think, “Oh, I am the best artist. I can do this, I can do that, I can do whatever I want. It’s a free-for-all.” But she was, like, “Are you really looking at your paintings? You have too much of that ego part.” And then I started realizing, “Oh wow, now I really know I know nothing.” Because once I started realizing what she was saying, it started to compute, and then I took a step back and understood there was this ignorance that I was kind of trapped in. So, I love her feedback—on everything! She’s always been the best at that. And not only is she an amazing artist, she’s one of my favorite artists, so when it comes from a place of experience, it means a lot more to me—which is great, because, during every single meal, we talk about the stresses of art and how we can improve.

Turned out 2020 was a perfect year to take off. How did that work out for you? Unfortunately, the tragic coincidence just happened to work out that way. It’s pretty ironic. I desperately needed time and I found myself having all the time in the world. It was definitely a year of mixed emotions and tragedy. I had all this spare time to work on improving my skills and make more work. But it was also a time when everything got harder, not just for me but for everyone. Just going grocery shopping felt like work. It definitely took a toll on my painting. I also changed my technique quite a bit since the old one was requiring me to pull all-nighters, which later snowballed into severe insomnia. So the year seemed to be filled with tons of hard work and sleepless nights. It is kind of odd to say this now, but I feel like I am finally starting to get a handle on this new technique. But we will see. @tonyytoscani

JUXTAPOZ .COM 45

TRAVEL INSIDER

The Land of Fire and Ice David Molesky Travels to Iceland In the back courtyard of my favorite cafe in San Francisco, I heard a familiar intonation and, curious, asked if they were speaking Icelandic. “What, do you recognize my accent from a Sigur Rós video?” challenged one of the men, who was mildly surprised when I replied, “No, I lived there.” Intrigued, the Icelanders prodded me into sharing the story of living in Reykjavík’s former city library when it was owned by the painter Odd Nerdrum and how conversation evolved into a studio visit and a sale—making me the only non-Icelandic artist in the young businessman’s growing art collection. Years later, during the autumn of 2019, the collector and his wife visited me in Brooklyn and purchased another painting, Unfinished Breakfast. They also asked to put a large painting on hold for purchase the next year. Even as the world entered lockdown, they kept their word. The plan was for 46 SPRING 2021

me to transport the oversized, rolled-up canvas on the plane and then come to paint in their summer cabin, comfortably nestled within the mythical landscape of Iceland. Getting There One slight hurdle: due to the pandemic, US passport holders were not permitted into Nordic and EU countries. Luckily, a good friend had a contact working at the Icelandic Ministry of Foreign Affairs who took my case, and after a few months of processing, I was issued a letter permitting a narrow window of time to enter the country. Boston was the only airport offering service to Iceland, so in the company of a sparse, few fellow travelers, I passed through an empty TSA checkpoint, and then after a requisite 5 1/2 hours of direct-to-video movies, stumbled into Keflavik airport, ushered into a cubicle and assaulted with a cotton swab shoved up my nose. Welcome to Iceland.

After two hours of traversing ice and snow with the hum and crackle of spiked tires and gusts of wind that jolted the vehicle sideways, my driver delivered me, in the shadow of darkness, to the cabin. It was 9:30 am. A faint ink color swathed the sky where the sun would emerge two hours later. In the winter months, our star only makes a low arch above the horizon before dropping back down again, a bit clockwise from where it rose. This scarcity of light can deflate you like a wilted flower, so a gulp of Vitamin D supplements helps tremendously, as well as a diet of fatty fish which Iceland supplies in abundance. A silver lining to this pervasive dimmer switch are day-long sunrise/sunsets. If they can make their way through the variable atmospheres, the rays shift prismatically to every color of the rainbow. On rare occasions you can witness other strange phenomena such as sundogs, ice halos,

All photos: By David Molesky

TRAVEL INSIDER

polar stratospheric clouds, and on clear nights, the aurora borealis. Golden Circle The geothermally heated public pools and rustic “hot pots” scattered through the landscape make it possible to enjoy some sun outdoors even when it's literally freezing. Just a stone’s throw away from the cabin are some great options. The town of Flúðir is home to the Secret Lagoon, a natural hot tub the size of a pond. In the tiny village adjacent is Hrunalaug, a primitive hot spring tucked into the hillside at the end of a short hiking trail. Year round greenhouses also harness these geothermal vents. At Friðheimar in Reykholt, the largest producer of tomatoes in Iceland, you can bask in the warm humidity of the restaurant inside the greenhouse while enjoying their world famous tomato soup. To the North, along the road that leads into the highlands, are two famous natural wonders, Geysir

(the etymological source of the word geyser) and Gullfoss (golden falls) which is basically the Niagara of Iceland. Proceed west in the direction of Reykjavík to discover Þingvellir National Park, which boasts a huge lake and a canyon that physically manifests the North American and European tectonic plates moving away from each other. This area is also the founding site of the oldest operating parliament in the world—the Alþingi, which relocated to Reykjavík (smokey bay) in 1843.

taxes to him. Most of the vikings rejected Harold and battled him without success. In 874 AD, they began a 600 mile retreat due west, along with their livestock, sailing and rowing boats across the Atlantic Ocean to settle the shores of Iceland. The challenges and conflicts of their migration were passed down through generations of oral tradition and dutifully written in runic characters in the 13th century. (For a cinematic view of viking life, check out the cult classic When the Raven Flies.)

Viking Settlement In the Middle Ages, independent seafaring people from Western Norway had a summer tradition of sending their young men out across the sea—usually to Ireland and Scotland—with the goal of bringing back treasures and wives (in no particular order?) You want vikings, you get vikings. In the mid-800s, a warlord named Harold, in attempting to unify the Norse clans under his control, demanded that everyone pay tribute

To ensure the right people came to Iceland (the nice land), someone had the clever idea to name the land covered with ice Greenland and the land with green forests and pasture Iceland. For those who came to Iceland, the law stated that you could claim as much land as you could walk the perimeter of in one day—not always easy in the lumpy mosscovered lava fields. Amazingly, the settlement of Iceland did not involve the displacement of any native peoples, only the foxes and mice who, it is

JUXTAPOZ .COM 47

TRAVEL INSIDER

assumed, drifted over on ice. Apparently at that time, the land was covered in forest, but little did the settlers know that these trees were old growth. They looked just like young trees in Norway because the severe weather and wind stunted their growth. Eventually, the newcomers used all of the trees as firewood, and without shelter and root structures, powerful winds blasting off glaciers blew the topsoil into the ocean, making farming even more impossible. Things got grim and then even worse as the ash from volcanic eruptions caused a mini ice age. Huddling together into smaller crevices in their mud huts, they resorted to burning manure from livestock. To prevent starvation, nothing was wasted. Every part of the sheep was eaten and there was never a by-catch, thus the taste for debatably appetizing traditional delicacies such as skata or hákarl, the infamous rotting piss shark. Reaching a ripe old age was nearly impossible. Life itself required a determined blind optimism. If you didn’t have that, your chances of survival were basically zero. This very attitude, established by experiences of the early settlers, is fundamental to the Icelandic mentality. Their national motto “Þetta reddast” translates to “it will work out.” Landlocked and living in poor conditions, the scattered 48 SPRING 2021

settlements were vulnerable. A few centuries after the settlement, Iceland was first colonized by Norway and ultimately ended up under Danish rule through blue blood marriages in Scandinavia at the time. The Danes were harsh and confiscated many of Iceland’s most valuable possessions, including its self-esteem and confidence. From Third World to First World In May of 1940, Allied Forces led by the British temporarily occupied Iceland, forestalling the Nazis who had recently conquered Denmark and Norway. Although not welcomed at first, it turned out to be a godsend for Iceland, previously one of the poorest countries in Europe. It wasn’t uncommon for people born in the ’30s to be raised in the same kind of mud huts dating to centuries prior. In 1944, Iceland declared independence and took ownership of the airports that had been used as refueling stations for aircraft coming over from America. Although Icelandic engineers were aware of the potential for geothermal energy, its use didn’t become widespread until the oil crisis of the 1970’s. Just a minimal amount of drilling untapped an unlimited source of volcanic-level heat, giving Iceland full energy independence.

Now, homes are heated and electricity is generated for peanuts, with enough energy left over to outsource energy-intensive industrial projects like aluminium smelting. Influx of Tourism When I returned to Iceland for the first time in 11 years, I was surprised by the mass of foreigners. Tourism had just become the top industry, surpassing the position held by fisheries for a millenium. With a citizenry of only 350,000, half of whom live in Reykjavík, Iceland became flooded with 2.3 million tourists that year. Now, with borders closed to the US and very little travel coming from Europe, it's been a pleasure to return to the natural attractions that are blissfully less crowded than in decades. I’ve enjoyed spending my pandemic winter in Iceland, the only country outside of the US where I have felt truly at home. With my three month tourist Schengen visa soon to expire, I’m making plans to stay longer: I applied for an extended visa, and have been accepted to the Akureyri Art Museum residency on the north coast. And so I begin the next chapter of my personal Icelandic Saga. I’ve heard springtime on the arctic circle is magical. —David Molesky

IN SESSION

Mel Valentine Columbia College Chicago “When it came time to pick a college, I was super torn between biology studies and art,” says Mel Valentine. “I ended up going to community college for two years to prep for a biology degree, but every day when I got home, all I wanted to do was draw.” Valentine, who was born in Miami, attended seven different elementary schools before her family settled down, and so, was prepped to pivot and travel through the States searching for the right institution when she made the choice to study art at Columbia College Chicago. “My first week I attended the Illustration Student Group on campus, and honestly, never looked back. It was so freeing to meet so many incredible people my age making art that was very different from each other’s. I eventually became the president of the club, and it was an incredible experience helping new students feel a sense of community the way I needed to feel when I first came to Columbia.” 54 SPRING 2021

Founded by two women in 1890, Columbia is located in South Side Chicago and is known for its industry-canny teachers, a network connecting it to Chicago’s cultural ecosystem. In fact, school President Kwang-Wu Kim, a trained concert pianist and Philosophy undergrad, describes the urban institution as “revenge of the fringe.” For example, comedian and SNL star Aidy Bryant, actress and producer Issa Rae, and now, Who Am I? illustrator Mel Valentine. Valentine’s autobiographical piece addresses having to hide her identity, and she is gratified that so many fans related for different reasons. “With Comics, I love the ability to create anything I can possibly think of with zero limitation. I always describe it as making a dream movie with an infinite budget, and where everything I could possibly want exists and is at my disposal. I love being able to tell stories

exactly how I want to tell them with characters I know others can connect to.” We love to shout out places and people happily making art, and Mel’s is a great story. “I feel infinitely lucky to have come to Columbia. The illustration professors are all passionate people who love what they do. The advice and attention I received was out of this world. Chris Elio, Chris Arnold, Cheri Charlton, Jeremy Smith and Ivn Brunetti all helped me become the artist I am today. I also love Chicago so very much; the art scene here is incredible in so many ways, and the comic community here is so rich, diverse and friendly.” An inspiring start for spring! —Gwynned Vitello melvalentinev.com colum.edu

Above: Who Am I, Digital Illustration, 2019

Hunter Potter I’ll Wake Up Older

Hunter Potter, Football Season Is Over, 2020, Acrylic and spray paint on canvas, 72 x 96 inches

February 20 - March 27, 2021

ON THE OUTSIDE

Lone Wolf Sunset Up High With Helen Bur Meeting Helen Bur at the Artscape mural festival in Sweden was memorable in itself. I had borrowed her 60-foot boom lift as we anticipated her arrival. The night she flew into town, as I handed over the keys, I asked if she needed a video projector to sketch her mural on the massive 4-story wall that awaited. The way she looked at me—with this wisdom her eyes carry—I might as well have asked if she painted with noodles instead of brushes. She wasn’t judging the use of projectors, or critical of the question, but she’s clearly a purist, a magician with no need for technical support. Purists don’t use projectors, but they do pack Swiss army knives. Helen is one of the most powerful and resourceful muralists in the game. She paints like a new old 56 SPRING 2021

master, one with a more humble and empathetic voice. We recently mused over all we took for granted back then, traveling the world and making monumental paintings alongside new friends. Her articulation of our recent global lockdown experience is a needed reminder, so poignantly true: “When you’re wrapped up in expecting one thing, then you’re thrown off the boat, treading water. You’re gently reminded never to take anything for granted, to adapt and accept the gift of the unexpected and how that grows you as a person.” Kristin Farr: Is there a tension or difference you feel between your studio paintings and public murals? Helen Bur: There is definitely a wavering tension created in the shift between these two spaces.

The occupied space, the historic context and the awareness of who will be consuming the work each carry their influence. Leaving art school, you have this institutionalised and educated language. A canvas holds the whole history of art; almost everything that can be painted has been. That’s not the case with walls, you’re occupying a space in the sketchbook of the hoi polloi—everyone can doodle and consume regardless of language, but also everyone is talked to and visually impacted, whether they choose to be or not. Both spaces come with their own freedoms and to some extent, responsibility. It’s a matter of treading carefully between creating poetic or provocative work without it becoming exclusionary. I’m always trying to

Above: The Place That Makes You, Parenti, Calabria, Italy, for Gulia Urbana Festival, 2020

ON THE OUTSIDE

bridge the gap of language so the work I create can exist across these two spaces; but I think that often means it carries a tension and becomes the misfit in either room. How many murals have you painted, and what do you love most about painting in public? Hmm, it must be a good pocket full or two by now… maybe around fifty or sixty, and with the littlest ones, somewhere in the hundreds. The adrenalin and fresh air, the offerings, encounters, characters, insects, birds, sunsets from the top of the cherry picker—I really sound like a terrible romantic, huh? But it’s truly beautiful to be a street worker, surrounded by life, living. All things that are especially enticing right now in their impossibility as I sit in the UK’s third lockdown…

painting. I have such a long way to get to where I want with it. The work is currently fairly narrative driven, so it’s about retaining that whilst also pushing the language of the material itself. One of the painters I am in love with is Cecily Brown. You really have to work to find the figures lost in the paint, it’s almost like those magic eye books! Right now I'm in this purgatory between learning and unlearning the language of realism, always trying to loosen up, always accidentally overworking. Anyone can paint a finger with enough strokes, but the holy grail is to paint it with one. Talk about the circle, the hoop. What does this signature symbolize for you or others? The circle is this wonderful symbol that holds a real fist full of symbolic meaning in different cultures; on the one hand, it’s wholeness, oneness, totality, eternity, perfection. And on the other

hand, it’s repetition, constriction, confinement. So, broadly, it holds this duality and polarity that have always dominated the themes in my work. I also love how it simply interrupts the image. I try to intentionally depart far enough away from a natural situation that it sits on this sort of pre-surrealistic armchair. Like a little glitch of an uncomfortable or unpalatable thought, and how it might look if you could embody it. It’s enlightening to think about how you are portraying unsaid feelings. How do you find your subjects? Are they often real people, or amalgamations of those you meet or see? They are always real (as far as I know!) Friends, family, whoever is around me at a specific time. Usually, the concept is coincidental to the person, and the figures are mostly intended to be universal, symbolic, rather than a portrait of the sitter.