Nysa-Scythopolis: The Southern and Severan Theaters. The Stratigraphy and finds 9789654065962, 9654065967

118 19 18MB

English Pages [289] Year 2015

Cover

Color Page 1

Color Page 2

Front Matter

Contents

Abbreviations

Preface

The Bet She’an Archaeological Project Chronological Chart*

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: The Southern Theater

Chapter 3: The Severan Theater

Chapter 4: The Pottery

Chapter 5: The Glass Finds

Chapter 6: The Coins

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Gabriel Mazor

- Walid Atrash

- Marc Balouka

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

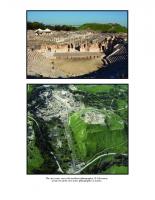

Aerial view of the theater (photographer, D. Silverman); northeastern section of the theater scaena (photographer, G. Laron).

The civic center, view to the northwest (photographer, D. Silverman); aerial view of the civic center (photographer, G. Laron).

IAA Reports, No. 58/1 bet she’an archaeological project 1986–2002 Bet SHE’an III, Part 1

nysa-scythopolis: the Southern and severan theaters Part 1: The Stratigraphy and Finds gabriel mazor and Walid Atrash

With Contributions by Marc Balouka, Lawrence Belkin, Ariel Berman, Avi Katzin, Tania Meltsen, Débora Sandhaus, Tali Sharvit and Tamar Winter

ISRAEL ANTIQUITIES AUTHORITY JERUSALEM 2015

Bet She’an Archaeological Project Publications Israel Antiquities Authority

IAA EXPEDITION DIRECTORS: RACHEL BAR-NATHAN GABRIEL MAZOR

VOL. III: NYSA-SCYTHOPOLIS: THE SOUTHERN AND SEVERAN THEATERS Part 1: The stratigraphy and finds

IAA Reports Publications of the Israel Antiquities Authority Editor-in-Chief: Judith Ben-Michael Series Editor: Ann Roshwalb Hurowitz Volume Editor: Shelley Sadeh

Front Cover: Aerial view, looking southeast (photographer: G. Laron) Back Cover: Severan Theater scaenae frons (T. Meltsen) Frontispiece: G. Laron, D. Silverman Typesetting, Layout and Cover Design: Ann Buchnick-Abuhav Production: Ann Buchnick-Abuhav Illustrations: Tania Meltsen, Natalia Zak, Irina Berin Printing: Art Plus Ltd., Jerusalem Copyright © 2015, The Israel Antiquities Authority, Jerusalem POB 586, Jerusalem, 91004 ISBN eISBN 9789654065962 ~www.antiquities.org.il

In Memoriam

Amir Drori, 1937–2005 Founder and First Director of the Israel Antiquities Authority (1989–2000) Foremost Supporter of the Bet She’an Archaeological Project

Contents

PART 1: THE STRATIGRAPHY AND FINDS (IAA Reports 58/1) ABBREVIATIONS

vi

PREFACE

ix

THE BET SHE’AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT CHRONOLOGICAL CHART

xiii

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

1

CHAPTER 2: THE SOUTHERN THEATER

Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

9

CHAPTER 3: THE SEVERAN THEATER

Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

21

CHAPTER 4: THE POTTERY

Débora Sandhaus and Marc Balouka

189

CHAPTER 5: THE GLASS FINDS

Tamar Winter

207

CHAPTER 6: THE COINS

Ariel Berman

229

CHAPTER 7: ARCHITECTURAL ANALYSIS AND PROPOSED RECONSTRUCTION

Walid Atrash

273

CHAPTER 8: RECONSTRUCTION WORK IN THE SEVERAN THEATER

Lawrence Belkin and Avi Katzin

349

CHAPTER 9: THE ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENTS Appendix 9.1: List of the Architectural Elements

Gabriel Mazor

371 583

CHAPTER 10: THREE MARBLE STATUES FROM THE SEVERAN THEATER

Tali Sharvit

613

PART 2: THE ARCHITECTURE (IAA Reports 58/2)

APPENDIX 1: LIST OF LOCI AND BASKETS

625

vi

Abbreviations

AA AAS AASOR ABSA ACOR ADAJ AJA AnatSt ANES ANRW AS ‘Atiqot (ES) ‘Atiqot (HS) BAR Int. S. BASOR BCH Bet She’an I Bet She’an II BJ BMB BSOAS CAH DaM DOP ESI HA HA–ESI IAA Reports IEJ INJ IstForsch IstMitt JBL

Archaölogischer Anzeiger Les annales archéologiques arabes de la Syrie 1951–1965 Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research Annual of the British School at Athens American Center of Oriental Research Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan American Journal of Archaeology Anatolian Studies Ancient Near Eastern Studies Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt Assyriological Studies English Series Hebrew Series British Archaeological Reports (International Series) Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research Bulletin de correspondance hellénique G. Mazor and A. Najjar. Bet She’an I: Nysa-Scythopolis: The Caesareum and the Odeum (IAA Reports 33). Jerusalem 2007 R. Bar-Nathan and W. Atrash. Bet She’an II: Baysān: The Theater Pottery Workshop (IAA Reports 48). Jerusalem 2011 Bonner Jahrbücher Bulletin du Musée de Beyrouth Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies Cambridge Ancient History Damaszener Mitteilungen Dumbarton Oaks Papers Excavations and Surveys in Israel Hadashot Arkheologiyot (Hebrew) Hadashot Arkheologiyot–Excavations and Survey in Israel Israel Antiquities Authority Reports Israel Exploration Journal Israel Numismatic Journal Istanbuler Forschungen Istanbular Mitteilungen Journal of Biblical Literature

vii JDAI JEA JGS JRA JRS JSP LA LIMC MA MAAR MDAIR MEFRA NEAEHL 5 OCD OIP Öjh PBSR PEFQSt PEQ PUAES PWRE QDAP RB SBF SCI SHAJ ZDPV ZPE

Jahrbuch des deutschen archäologischen Instituts Journal of Egyptian Archaeology Journal of Glass Studies Journal of Roman Archaeology Journal of Roman Studies Judea & Samaria Publications Liber Annuus Lexicon iconographicum mythologiae classicae Mediterranean Archaeology Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome Mitteilungen des deutschen archäologischen Instituts, Römische Abteilung Mélanges de l’École française de Rome, Antiquité E. Stern ed. The New Encyclopedia of the Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land 5: Supplementary Volume. Jerusalem 2008 S. Hornblower and A. Spawforth eds. The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford 1996 Oriental Institute Publications Jahreshefte des österreichischen archäologischen Instituts in Wien Papers of the British School at Rome Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement Palestine Exploration Quarterly Publications of the Princeton University Archaeological Expedition to Syria Pauly-Wissowa, Realencyclopädie der classichen Altertumswissenschaft Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities of Palestine Revue Biblique Studium Biblicum Franciscanum Scripta Classica Israelica Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan Zeitschrift des deutschen Palästina-Vereins Zeitschrift fϋr Papyrologie und Epigraphik

Abbreviations Used in This Volume IAA Israel Antiquities Authority IAHU Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem IDAM Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums UME University (of Pennsylvania) Museum Expedition

ix

Preface

Following the conquest of the East by Alexander the Great, about 30 Greek poleis were founded in Coele Syria by the Ptolemaic and Seleucid dynasties (although for some of them Alexander the Great was referred to as the founder or ktistes). First established as military strongholds and administrative centers, and later refounded as Greek poleis, they became the predominant vehicles by which Greek culture was gradually spread throughout the Hellenized East. Despite relatively wide-scale excavations conducted in most Hellenic cities of the Decapolis, none of them revealed a theater of the Hellenistic period. Edmond Frézouls (1961:68) reached the conclusion that the Hellenic cities in the East, which later became part of the Roman Empire’s eastern provinces, were not truly acquainted with the Greek theater culture (Frézouls 1952a; 1952b; 1959; 1961; 1982). Gideon Fuks, in his work published prior to the wide-scale excavations at Nysa-Scythopolis (Fuks 1983:123–124), suggested that this city might have set a notable exception. It was known to have been founded by Dionysus (Lifshitz 1970:62, n. 3; Di Segni, Foerster and Tsafrir 1996:345– 348), whose cult was strongly associated with the theater culture (Frézouls 1961:68). However, the excavations of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) expedition, conducted in 1986–2002 on behalf of the Bet She’an Archaeological Project at Tel Iztabba, the location of Hellenistic Nysa-Scythopolis, proved otherwise. No clear evidence for the existence of a theater was anywhere revealed (Bar-Nathan and Mazor 1994; for a review of the Bet She’an Archaeological Project, see Bet She’an I). Evidence obtained from seal impressions found during the excavations of Tel Iztabba (Mazor, Sandhaus and Finkielsztejn, in prep.) indicates that the cult of Dionysus, the divine founder of the city, was practiced at Nysa-Scythopolis as early as the Hellenistic period. Its significance at Roman Scythopolis is clearly demonstrated by a number of inscriptions (Di Segni 1997) and the presence of three theaters within the

city’s civic center. The Northern Theater, located in front of a spacious piazza at the foot of Tel Bet She’an, was partly excavated in various probes by the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University (IAHU) expedition, the results of which have not yet been published (Atrash 2006). The Southern and Severan theaters, the subjects of the current volume, were excavated and researched by the IAA expedition. The Southern Theater was identified during the excavations of the Severan Theater, and is reported here for the first time (see below). The Severan Theater was first surveyed, described and precisely located on the map of the Survey of Western Palestine (SWP), drawn by the team of the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF) in April 1874. Claude Conder and Herbert Kitchener (1882 II:106–107) considered the theater to be “the best preserved specimen of Roman work in western Palestine.” Remarkable features of the theater’s cavea, according to Conder’s description, were the oval recesses half way up the cavea (drawn by Condor, see Condor and Kitchener 1882 II: figure on p. 107). They had been previously observed by William Bankes in 1818, who included them in his relatively accurate plan of the theater (see Segal 1999:51–52, n. 80, Fig. 52), and referred to in other survey reports of the site (Irby and Mangles 1823:301–303; Robinson 1856:326–332; Gúerin 1874:284–298). The Severan Theater was first excavated by Shimon Applebaum on behalf of the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums (IDAM, now the IAA) during the years 1960–1961 (Applebaum 1960; 1961; 1962a; 1962b; 1963:380–383; 1971; 1978:77–97; Applebaum, Isaac and Landau 1978:139–140, n. 13), then again by Avraham Negev in 1962 (Negev 1963). Apart from some brief preliminary reports by Applebaum, no comprehensive, let alone final, report of the excavations was published. Applebaum briefly referred to a full-sized marble statue (Applebaum 1978:96–97), as well as an inscription from the theater (Applebaum, Isaac and Landau 1978). Negev cited

x several inscriptions in a letter to the director of the IDAM (Applebaum 1965:2). A later article briefly discussed the unique acoustic cells (Ovadiah and Gomez de Silva 1981–1982) that were found in the theater. The wide-scale excavations conducted in the Roman city’s civic center during the years 1986–2002 by the IAA expedition, on behalf of the Bet She’an Archaeological Project, resumed the excavations of this theater, which was largely exposed by Applebaum, and which was now fully exposed and researched. An earlier theater, erected in two construction phases, was discovered below the later Severan Theater. As it was buried below the Severan Theater and no continuation was observed between the two, they are dealt with as two separate theaters. In the present report, the earlier theater is termed the ‘Southern Theater’, as opposed to the contemporary Northern Theater, while the later one built over it is termed the ‘Severan Theater’, as it was built during the reign of the Severan Dynasty. During and after the IAA excavations, consolidation work was conducted in the Severan Theater by the IAA preservation team, first directed by Alon BenZvi and later by Evgeny Ivanovsky. Following the consolidation, wide-scale restoration works were undertaken in the aditus maximi, the scaena, the northeastern section of the scaenae frons, the nearby section of the media cavea and its praecinctio, several vomitoria and the theater’s circumference wall, all supervised by the architects Lawrence Belkin and Avi Katzin, who have contributed a chapter to the current report summarizing the consolidation and reconstruction works and their fundamental guidelines (see Chapter 8). The IAA Expedition of the Bet She’an Archaeological Project The staff of the IAA expedition, directed by Gabriel Mazor and Rachel Bar-Nathan, included the following members: Field Supervisors: Walid Atrash (theaters), Jacob Harel, Arfan Najjar, Menahem Arazi, May Gordon and Anat Achiav. Assistant Supervisors: Laura B. Mazow, Eyal Baruch, Wahib Daud, Yael Gorin-Rosen, Yael Kadosh (theaters) and Ilan Pahima. Surveyors: Dan Bahar, Roni Saban, Beni Arubas and Tania Meltsen (plans and figures of theater publication). Photography: Gabriel Laron and Yoram Lahman.

Architectural Elements Recording: Edna Amos, Sara Shor and Tania Meltsen. Pottery Analyses: Mark Balouka, Smadar Shapira, Naomi Amit and Debora Sandhaus. Pottery Drawing: Irina Ledisky-Reznikov. Pottery Restoration: Boris Kats, Frida Raskin and Moshe Ben-Ari. Numismatics: Ariel Berman and Haim Gitler. Metal Laboratory: Ella Altmark. Glass Artifact Analysis: Yael Gorin-Rosen and Tamar Winter. Mosaic Floor Recording: Tamar Shadmy. Epigraphy: Vassilios Tzaferis and Lea Di Segni. Architects: Amnon Bar-Or, Lawrence Belkin, Giora Solar, Peter Bogut, Avi Kazin, Max Tan’ee and Marcel Lubash. Engineers: Jacob Shefer and Abraham Sevilia. Contractors: Yehuda Davidovitch, Habib Gandur and Talal Omar. Preservation: Yevgeni Ivanovitz and Ilan Pahima. Administration: Menachem Efrony, Eyal Eldar and Ronit Eini. The Publication of the Theaters The completion of the excavation of both the Southern and Severan Theaters was followed by research into their architectural units and numerous architectural elements. This was first conducted by Walid Atrash, Amnon Bar-Or and Edna Amos as part of a comprehensive restoration proposal of the scaenae frons of the Severan Theater (Bar-Or and Atrash 1988; Atrash and Bar–Or 1990; Atrash and Amos 1997), and it was continued with analysis of the theater’s architecture and stratigraphy conducted by Walid Atrash and Gabriel Mazor. In 1997, the IAA expedition was granted full publication rights for the excavations of the Severan Theater conducted by Applebaum and Negev. No records of the 1960–1962 excavation by Applebaum exist, apart from some photographs and a few unrecorded pottery finds and coins, nor were any architectural elements recorded, drawn or analyzed. They were found scattered haphazardly in the area north of the theater’s facade wall. Finds from Negev’s excavation were not located in the IAA storage and were presumably lost. They were not published apart from a short note (Negev 1963).

xi These architectural elements were fully processed, and some were included in the restoration work. This report also integrates the pottery and coins from the 1960–1962 excavations, as best as possible in view of the lack of records, with the results of the latest IAA excavations, in order to present a comprehensive final report of the Southern and Severan Theaters of NysaScythopolis. Other studies of the theater include a partial analysis of the scaenae frons friezes published by Ovadiah and Turnheim (1994), although this does not relate to the Severan Theater’s stratigraphy or chronological stages. A thorough analysis of the Severan Theater’s scaenae frons construction stages and a reconstruction of the Severan Theater were undertaken by Atrash (2003; 2006). The extensive use of the northeastern section of the Severan Theater, mainly its eastern aditus maximus and the piazza in its northeastern corner, as the premises for a large pottery workshop during the Umayyad period, has been studied and published (Bet She’an II). The chronology of the site, as established by the IAA expedition, was published in Bet She’an I and slightly revised in Bet She’an II; it is here further adjusted to incorporate the theaters’ phases (see the Bet She’an Archaeological Project Chronological Chart, p. xiii). For general information concerning the Bet She’an Archaeological Project, its expeditions, excavation results, publication methodology, the historical background and related bibliography, see Bet She’an I. The geographical setting and history of Nysa-Scythopolis related to the excavations results also appear in Mazar et al. 2008: 1616–1644. The present volume, Bet She’an III, the final report of the excavations of the Southern and Severan Theaters, is bound in two parts. Part I includes the introduction (Chapter 1) and the stratigraphy of the Southern Theater (Chapter 2) and the Severan Theater (Chapter 3), based on the current and earlier excavation results. This is followed by the finds from the 1986–1990 seasons (integrating the few finds from the 1960–1962 excavations): pottery (Chapter 4), glass (Chapter 5) and coins (Chapter 6). Part II comprises the architectural analysis of both the Southern and Severan Theaters, their architectural stages and restoration, as well as research methodology and comparanda (Chapter 7), the preservation and reconstruction works conducted in the Severan Theater (Chapter 8), the analysis of all the theaters’ architectural elements

(Chapter 9, with its own appendix) and a presentation of three marble statues recovered in the Severan Theater (Chapter 10). Finally, Appendix 1 presents the list of loci and baskets. The plans and sections, figures and plates are all the fruit of the recent research. All the plans, isometric reconstructions and drawings of the architectural elements were meticulously prepared by Tania Meltsen. The Israel Antiquities Authority, our base and research center, and its directors, have granted support to the Bet She’an Archaeological Project. The late Amir Drori, the founder and first director of the IAA, encouraged and supported the Bet She’an Archaeological Project, referring to it as the IAA flagship. Thanks are also due to the late Shuka Dorfman, his successor, for dedicating the Beth She’an Archaeological Project final publications to him. We are thankful to Arthur Segal, who read the manuscript and whose valuable scholarly remarks contributed considerably to the research of both theaters, and to Donald T. Ariel, who greatly aided in the publication of the coins. Thanks are also due to the IAA publication department: to the editor-in-chief, Judith Ben-Michael, to the series editor, Ann Roshwalb Hurowitz, to the volume editor, Shelley Sadeh, and to the publication-office staff. Last but not least, to Tania Meltsen, whose skills and patience perfected all the drawings of the reconstructions, plans, sections, and architectural elements for the final report, and to Gabi Laron for his superb photography. The excavations of both the Southern and Severan Theaters conducted by the IAA expedition followed the monumental work conducted by Shimon Applebaum in the Severan Theater, in whose footsteps we were honored to follow. Our research integrates material that he generously donated and discussed with us, as well as further material that was later donated by his family, after he regretfully passed away. Although the excavation and research of the theater were completed years after it was first revealed by Applebaum, we were always inspired by his archaeological knowledge and experience. We wish this publication to stand as a tribute to his pioneering archaeological work at NysaScythopolis.

G. Mazor and W. Atrash Jerusalem 2015

xii R eferences Applebaum S. 1960. A Letter to the General Director of the Israel Antiquity Department (IAA Archive). Jerusalem. Applebaum S. 1961. A letter to the General Director of the Israel Antiquity Department (IAA Archive). Jerusalem. Applebaum S. 1962a. Chronique archéologique: Bet Shean. RB 69:408–410. Applebaum S. 1962b. The Roman Theatre of Beth-Shean. In The Beth Shean Valley: The 17th Archaeological Convention. Jerusalem. Pp. 71–73 (Hebrew). Applebaum S. 1963. Where Saul and Jonathan Perished: Beth Shean in Israel. The Roman Theatre Revealed and a Greek Statue Discovered. Illustrated London News March 16, 1963:380–388. Applebaum S. 1965. A Letter to the General Director of the Israel Antiquity Department (IAA Archive). Jerusalem. Applebaum S. 1971. A Greek Statue from Beth-Shean. Museum Haaretz Bulletin 13:11–13 (Hebrew). Applebaum S. 1978. The Roman Theatre of Scythopolis. SCI 4:77–103. Applebaum S., Isaac B. and Landau Y.H. 1978. Varia Epigraphica. SCI 4:139–140. Atrash W. 2003. The Scaena Frons of the Roman Theatre in Scythopolis (Bet She’an): Architectural Analysis and Reconstruction. M.A. thesis. University of Haifa. Haifa (Hebrew). Atrash W. 2006. Entertainment Structures in the Civic Center of Nysa-Scythopolis (Beth-She’an) during the Roman and Byzantine Periods. Ph.D. diss. University of Haifa. Haifa (Hebrew). Atrash W. and Amos E. 1997. The Roman Theater Scaena Frons: Third Interim Report (IAA Internal Report). Bet She’an (Hebrew). Atrash W. and Bar-Or A. 1990. The Roman Theater Scaena Frons: Second Interim Report (IAA Internal Report). Bet She’an (Hebrew). Bar-Nathan R. and Mazor G. 1994. Beth-Shean during the Hellenistic Period. Qadmoniot 107–108:87–91 (Hebrew). Bar-Or A. and Atrash W. 1988. The Roman Theater Scaena Frons: First Interim Report (IAA Internal Report). Bet She’an (Hebrew). Conder C.R. and Kitchener H.H. 1882. The Survey of Western Palestine II: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography and Archaeology. London.

Di Segni L. 1997. A Dated Inscription from Bet Shean and the Cult of Dionysos Ktistes in Roman Scythopolis. SCI 16:139–161. Di Segni L., Foerster G. and Tsafrir Y. 1996. A Decorated Altar Dedicated to Dionysos, the “Founder” from Beth Shean, Nysa-Scythopolis. Eretz Israel 25:336–350 (Hebrew; English summary, p. 101*). Frézouls E. 1952a. Tetri romani dell’Africa francese. Dionisio 15:90–103. Frézouls E. 1952b. Les théâtres romains de Syrie. AAS 2:46– 100. Frézouls E. 1959. Recherches sur les théâtres de l’orient syrien I. Syria 36:203–227. Frézouls E. 1961. Recherches sur les théâtres de l’orient syrien II. Syria 38:54–76. Frézouls E. 1982. Aspects de l’histoire architecturale du théâtre romain. ANRW 11:343–441. Fuks G. 1983. Greece in Palestine: Beth Shean-Scythopolis in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods. Jerusalem (Hebrew). Guérin V. 1874. Description géographique, historique et archéologique de la Palestine I–III. Paris. Irby C.L. and Mangles J. 1823. Travels in Egypt and Nubia, Syria and Asia Minor during the Years 1817–1818. London. Lifshitz B. 1970. Notes d’épigraphie grecque. ZPE 6:62 Mazar A., Mazor G., Arubas B., Foerster G., Tsafrir Y. and Seligman J. 2008. Tel Beth-Shean; The Hellenistic to Early Islamic Periods: The Israel Antiquities Authority Excavations; The Hellenistic to Early Islamic Periods at the Foot of the Mound: The Hebrew University Excavations; The Fortress. NEAEHL 5:1616–1644. Mazor G., Sandhaus D. and Finkielsztejn J. In Preparation. Bet She’an IV: Nysa-Scythopolis: The Hellenistic City at Tel Iztabba (IAA Reports). Jerusalem. Negev A. 1963. Beth-Shean. RB 70:585. Ovadiah A. and Turnheim Y. 1994. “Peopled” Scrolls in Roman Architectural Decoration in Israel. The Roman Theatre at Beth Shean, Scythopolis (Rivista di archeologia, Suppl. 12). Rome. Robinson E. 1856. Later Biblical Researches in Palestine and the Adjacent Regions: A Journal of Travels in the Year 1852. London. Segal A. 1999. The History and Architecture of Theaters in Roman Palestine. Jerusalem (Hebrew).

xiii

The Bet She’an Archaeological Project Chronological Chart*

Stratum

Period

Date

Nature of Settlement, Historical Events and Theater Stages

1

Ottoman

1516–1917 CE

Small village and serai

2

Late Islamic/Mamluk

1291–1516 CE

Sporadic settlement

3

Crusader/Ayyubid

1099–1291 CE

Fortress of Galilee Principality

4

Abbasid/Fatimid

749–1099 CE

Post-749 CE earthquake settlement

5

Umayyad II

697–749 CE

Pottery workshop built within the theater’s premises; destroyed in January 18, 749 CE earthquake

6

Umayyad I

659–697 CE

From the 659 CE earthquake to ‘Abd al-Malik’s reform (697 CE)

7

Arab-Byzantine

634/635–659 CE

From the Arab conquest to the June 7, 659 CE earthquake

8

Byzantine III

550–634/635 CE

Cessation of building inscriptions, city deteriorates

9

Byzantine II

507–550 CE

Second renovation stage of the civic center, reduction in size of the theater and construction of the porticus along the facade

10

Byzantine I

400/404–507 CE

Establishment of Palestina Secunda (400–404 CE)

11

Roman IV

244–400/404 CE

Renovations following the May 19, 363 CE earthquake, reduction in height of the theater’s summa cavea

12

Roman III

130–244 CE

Hadrian’s visit, the Antonine and Severan dynasties; monumentalization of the civic center––construction of the Severan Theater and the later addition of the postscaenium

13

Roman II

31 BCE–130 CE

Imperial planning of the civic center, the Southern Theater: Phase I—Tiberius, Phase II—Flavian

14

Roman I

64/63–31 BCE

Pompey’s conquest, the founding of Roman Nysa-Scythopolis by Gabinius (57–55 BCE)

15

Hellenistic III

108/107–64/63 BCE

Hasmonean destruction

16

Hellenistic II

2nd century BCE

Foundation of the polis by Antiochus IV

17

Hellenistic I

3rd century BCE

Nysa-Scythopolis established as a military stronghold by Ptolemy II

*Revised from Bet She’an II to reflect the most current research

G. Mazor and W. Atrash, 2015, Bet She’an III/1 (IAA Reports 58/1)

Chapter 1

I ntroduction Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

The conquest of Coele Syria by Pompey (64/63 BCE) established a Roman province in a region that was densely settled by Greek cities controlling extensive territories. The Greek poleis of the Decapolis, previously conquered by the Hasmoneans, were seized by the Roman legions and shortly after rebuilt or refounded as Roman cities by Gabinius, the governor of the newly established province (57–55 BCE; Josephus, War I.vii.7; Antiquities XIV.iv.2). In honor of the governor, Nysa-Scythopolis was renamed for a while Gabinia Nysa (Barkay 2003:159). Due to the sense of security granted by the Roman Empire (Pax Romana), Nysa-Scythopolis was transferred from the well-protected mounds (Tel Bet She’an and Tel Iztabba) and refounded in the late first century BCE and early first century CE in the vast area of the ‘Amal basin and its surrounding hills. Evidence for the earliest stage of the Roman city in the first century BCE derives mainly from coins and pottery, while architectural remains are thus far insufficient to reconstruct any significant part of the city plan. On the other hand, the excavation results supply far more data regarding the plan of the civic center in the early first century CE (Plan 1.1). Within the civic center of Roman Nysa-Scythopolis (Roman II; 31–130 CE), the forum was the main focal point of the urban plan, which may have been influenced by city-planning trends customary in the Republican West, and far less common in the East. The forum contained a basilica in its northeastern part and two temples in the southeast. Paved streets surrounded the forum on all four sides, two of which, Pre-Northern Street and Pre-Valley Street, extended further out and led to two of the main city gates, the Caesarea and Damascus Gates (Plans 1.1, 1.2). South of the forum, the Southern Theater was erected. The unique location of the city on a major regional crossroads that linked the flourishing coastal cities with the extensive trade network of Damascus and

the wealthy poleis of Arabia (Roll 2002), lent the city immense strategic importance and economic prosperity, which reached its zenith in the second century CE. The urban planning of the city’s civic center during the second century CE, best termed ‘From Function to Monument’ (Plan 1.3; Segal 1997), was architecturally characterized, as in most poleis in the provinces of the Roman Empire, by its remarkable new imperial architectural design and baroque decor, as reflected in its colonnaded streets and monumental public buildings. The ‘monumentalization’ of the city landscape was a consequence of Hadrian’s tour to the region (128–132 CE), in which he presumably visited Nysa-Scythopolis, and was further advanced by his successors, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius, and even more so by Septimius Severus toward the end of the century. In all the cities of the eastern provinces, intensive urbanization was everywhere marked by the Flavian architectural renaissance, characterized by its monumental and exquisitely decorated public buildings. Colonnaded streets adorned by nymphaea and propylaea, temples and shrines dedicated to the imperial cult, such as caesarea, kalybe structures and altars, public halls including odea, theaters, hippodromes, amphitheaters and other entertainment facilities, as well as thermae, city gates, bridges and roads, were erected, establishing the Roman imperial koine (Plan 1.3; Fig. 1.1). In the early second century CE, the quarries of superb-quality limestone in the Gilboa Mountains were extensively exploited to supply the flourishing city of Nysa-Scythopolis. At the end of the century, architectural elements carved of marble and granite imported from Asia Minor and Egypt further enriched the city’s grandeur. The civic center of NysaScythopolis was graced with a monumental, richly adorned, baroque-oriented appearance (Lyttelton 1974) that characterized the city throughout the entire Roman and Byzantine periods.

2

Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

9

12 16

15 11

5

8

2 13

6

1 10 3 4

14

‘Ain el Mel`ab 7

‘Ain el-Malhah

0

1. Forum 2. Basilica 3. Forum Temple I 4. Forum Temple II 5. Temple(?) 6. Bathhouse 7. Southern Theater 8. Public Halls

9. Temple of Zeus Akraios 10 Street of the Forum Temple 11. Pre-Monument Street 12 Pre-Northern Street 13 Pre-Palladius Street 14 Theater Street 15 Shops 16 Pre-Valley Street

Plan 1.1. Nysa-Scythopolis: civic center of the first century CE.

100 m

3

Chapter 1: Introduction

4

17

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6.

Civic Center 7. Southeast (Gerasa) CityNysa-Scythopolis: Gate 13. Hellenistic City Plan 1.2 city plan Tel Bet She’an 8. Samaritan Synagogue 14. Eastern Bridge (Jisr el-Maktu’a) 1. Civic center 8. Samaritan synagogue 15. Western bridge Northeast (Damascus) City Gate 9. Church of Andreas 15. Western Bridge 2. Tel Bet She’an 9. Church of Andreas 16. Eastern cemetery Northwest (Caesarea) City Gate of the Martyr 16. Eastern Cemetery (Tell el-Hammam) 3. Northeast (Damascus) city10. Church gate 10. Church of the Martir (Tell el-Hammam) Southwest (Neapolis) City Gate Monastery of Lady Mary 17. Cemetery 4. Northwest (Caesarea) city11 gate 11. Monastery of Lady Mary 17. Cemetery South (Jerusalem) City Gate 12. Northern Cemetery 18. House of Kyrios Leontis

19. Circular Piazza 20. Bathhouse 21. Mosque 21. Mosque 22. Crusader fortress 22. Crusader Fortress 23. Turkish serai 23. Turkish Serai 24. Amphitheater 24. Amphitheater (Hippodrome)

5. Southwest (Neapolis) city gate 12. Northern cemetery 18. House of Kyrios Leontis second centurypiazza CE. 6. South (Jerusalem) city gatePlan 1.2. 13.Nysa-Scythopolis: Hellenistic citycity plan of the 19. Circular 7. Southeast (Gerasa) city gate 14. Eastern bridge 20. Bathhouse (Jiser el-Maktu’a)

(hippodrome)

4

Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

1. Forum 14. Valleyplan Streetof the second century 20. Temple Plan8. Caesareum 1.3. Nysa-Scythopolis: civic center, CE of Zeus Propylaeum 2. Basilica 9. Temple of Zeus Akraios 15. Street of the Eastern Thermae 21. Valley Sreet Propylaeum 3. Forum Temple I 10. Street of the Forum Temples 16. Western Thermae 22. Monument of Antonius 10. Street of the Forum Temples 18. Caesareum propylaeum 1. Temple ForumII 4. Forum 11. Street of Monuments 17. Thermae Propylaeum 23. Altar 11. Street of Monuments 19. Forum propylaeum 2. Basilica 5. Temple(?) 12. Northern Sreet 18. Caesareum Propylaeum 24. Nymphaeum 12. Northern Street19. Forum Propylaeum 20. Temple of propylaeum 6. Eastern ThermaeTemple 13. Palladius Street 25. Zeus Northern Theater 3. Forum I 7. Severan Theater Temple II 13. Palladius Street 21. Valley Street propylaeum 4. Forum

14. Valley Street 22. Monument of Antonius 5. Temple (?) Plan 1.3. Nysa-Scythopolis: civic center of the second century CE. 15. Street of the Eastern thermae 23. Altar 6. Eastern thermae 16. Western thermae 24. Nymphaeum 7. Severan Theater 17. Thermae propylaeum 25. Northern Theater 8. Caesareum 9. Temple of Zeus Akraios

Chapter 1: Introduction

5

Fig. 1.1. Nysa-Scythopolis: aerial view of the Roman–Byzantine civic center, looking southwest.

Four designated complexes (the hippodrome, the odeum, and the Severan and Northern Theaters) comprised the entertainment facilities of NysaScythopolis during the late second to early third centuries CE (Roman III). South of the civic center, a 270 m long, 67 m wide hippodrome was constructed (see Plan 1.2). Its cavea was partly built over a fill within its perpendicular walls and partly over vaulted substructures with entering vomitoria. The beatenearth floor of the arena was surrounded by a high wall decorated with a colored fresco depicting hunting scenes. Two tribunalia marked the center line of both longitudinal cavea sections, and a vaulted room below the northern tribunal may have accommodated a shrine.

Within the second-century civic center, a caesareum was erected upon a wide, leveled plateau, and a small odeum was built along its southern porticus (Bet She’an I). This small, theater-like, roofed auditorium had an ima cavea of 14 rows of seats furnished with profiled, white-limestone seats that accommodated an audience of c. 600 people. Its limestone-paved orchestra was entered via its aditus maximi and it had a narrow pulpitum and a high scaenae frons with three entrances from the porticus of the caesareum. It may have functioned as a bouleuterion, and the hall to the west of it, presumably a library, may have served as the municipal archive.

6

Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

Two theaters adorned the civic center in the late second century CE (Roman III). The Severan Theater, built over the earlier Southern Theater to the south of the forum, was founded partly upon the slope of the southern hill and partly over a vaulted substructure. Its orientation due north does not fit the setting of the forum; both complexes, separated by a street and a considerable difference in elevation, retained their separate architectural and functional diversities. The Northern Theater, partially revealed by the IAHU expedition (Arubas 2006:48–58; Atrash 2006:68–71; Arubas, Foerster and Tsafrir 2008:1641), was built into the southwestern slope of Tel Bet She’an and therefore faces southwest, an uncommon direction for a theater. It was relatively small and its cavea, not accommodated with vomitoria, was entered via the aditus maximi. Its southern facade was adorned by a porticus postscaenium (Atrash 2006: Fig. 240) that finds its best parallel in the northern theater at Gerasa (Clark et al. 1986:205–230, Fig. 1). The Northern and Severan Theaters of Nysa-Scythopolis were connected by a 170 m long colonnaded street (Palladius Street) with piazzas at both ends, creating a well-balanced urban plan (see Plan 1.3) that continued well into the Byzantine period (Plan 1.4), although the Northern Theater was dismantled during the late Byzantine period (Stratum 8, Byzantine III). Most of the entertainment facilities of Roman Nysa-Scythopolis were still functional throughout the entire Byzantine period (Byzantine I–III), although the nature of the performances conducted in them obviously underwent considerable changes over time, as paganism gave way to Christianity. Late in the Roman period, the summa cavea and porticus of the Severan Theater collapsed as a result of the earthquake of 363 CE and when reconstructed, the scaenae frons

was reduced in height. The scaenae frons was again reduced in height in the early sixth century CE. Despite its repeated reduction in size during the Byzantine period, the theater’s northern facade was enriched by a monumental porticus and a vast piazza, with a nymphaeum in front of it. The media cavea seems to have been removed during Stratum 8 (Byzantine III), and by the end of the Byzantine period, only the ima cavea was still functional. The Northern Theater apparently suffered constructional problems following the earthquake of 363 CE, and was finally dismantled in the sixth century CE (Byzantine III), apart from its southern facade, which remained to adorn its piazza. The odeum was active until the mid-fifth century CE, when it was dismantled along with the entire caesareum compound. In the framework of the Bet She’an Archaeological Project, the IAA excavations were conducted within the Southern and Severan Theaters and the surrounding area. Fortunately, the northeastern part of the Severan Theater had not been excavated by Applebaum in 1960–1962, enabling the IAA expedition to excavate here the Islamic phases (Strata 7–2) and the consecutive stages of the Severan Theater during Roman III–IV and Byzantine I–III (Strata 12–8). During excavation of the foundations of the eastern aditus maximus and the hyposcaenium, the presence of the earlier Southern Theater was revealed. Its construction phases are dated within the first century CE (Roman II, Stratum 13), and it was later completely covered by the Severan Theater. Subsequent probes conducted in other locations in the Severan Theater further confirmed the existence of the Southern Theater and its dating. Additional excavation and probes were undertaken, as required, to clarify stratigraphic or architectural problems during the complex architectural analysis.

7

Chapter 1: Introduction

Plan 1.4 Nysa-Scythopolis:9. civic center, plan 1. Forum Byzantine Building 2. Basilica 10. Round Church 11. Street of Monuments 1. Agora 3. Theater Street 10. Round church 4. Theater piazza Street 2. Basilica 5. Temple(?) 11. Street of12. Northern Monuments 13. Palladius Street 3. Theater Street Street Street 6. Eastern Thermae 12. Northern14. Valley 4. Theater piazza 13. Palladius Street Street 7. Severan Theater 15. Silvanus 8. Caesareum 16. Western Thermae 5. Temple (?) 14. Valley Street

of the Byzantine period Propylaeum 17. Thermae 18. Sigmae

19. Forum Propylaeum 19. Agora propylaeum 20. Round Church Propylaeum 20. Round church propylaeum 21. Valley Street Propylaeum 21. Valley Street propylaeum 22. Monument of Antonius 22. Monument of Antoninus 23. Altar 24. Nymphaeum 23. Altar 24. Nymphaeum 6. Eastern thermae Plan 1.4. 15. Silvanus Street Nysa-Scythopolis: civic center of the Byzantine period. 7. Severan Theater 16. Western thermae 8. Caesareum 17. Thermae propylaeum 9. Byzantine building 18. Sigmae

8

Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

R eferences Arubas B. 2006. The Impact of Town Planning at Scythopolis on the Topography of Tel Beth-Shean: A New Understanding of Its Fortifications and Status. In A. Mazar. Excavations at Tel Beth-Shean 1989–1966 I: From the Late Bronze Age to the Medieval Period. Jerusalem. Pp. 48–58. Arubas B., Foerster G. and Tsafrir Y. 2008. Hellenistic to Early Islamic Periods. NEAEHL 5:1636–1641. Atrash W. 2006. Entertainment Structures in the Civic Center of Nysa-Scythopolis (Beth-She’an) during the Roman and Byzantine Periods. Ph.D. diss. University of Haifa. Haifa (Hebrew). Clark V.A., Bowsher J.M.C., Stewart J.D., Meyer C.M. and Falkner B.K. 1986. The Jerash North Theatre, Architecture

and Archaeology 1982–83. In F. Zayadine ed. Jerash Archaeological Project 1981–83. Amman. Pp. 205–302. Lyttelton M. 1974. Baroque Architecture in Classical Antiquity. London. Roll I. 2002. Crossing the Rift Valley. The Connecting Arteries between the Road Network of Judaea/Palaestina and Arabia. In P. Freeman, L. Bennett, Z.T. Fiema and B. Hoffmann eds. Limes XVIII (Bar Int. S. 1084 I). Oxford. Pp. 215–230. Segal A. 1997. From Function to Monument: Urban Landscapes of Roman Palestine, Syria and Provincia Arabia. Oxford.

G. Mazor and W. Atrash, 2015, Bet She’an III/1 (IAA Reports 58/1)

Chapter 2

The Southern Theater Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

Introduction The presence of an earlier theater, whose remains had been sealed by the foundations of the later Severan Theater built upon it, was unknown to Applebaum during his excavations in 1960–1962. The first evidence of the Southern Theater of Stratum 13 was revealed during restoration works in the eastern aditus maximus of the Severan Theater and its adjoining northeastern cavea segment. The eastern aditus maximus, while mostly preserved, including a substantial section of the western part of its barrel vault, was leaning dangerously to one side, and the adjacent cuneus of the ima cavea had partly collapsed. Reconstruction work aimed to repair the theater’s foundations, where presumably its constructional problems existed, and to rebuild the entire northeastern part of the Severan Theater, reusing its original masonry. To this end, the eastern aditus maximus walls and vault were dismantled, while marking every stone in the process. When the Severan Theater foundations were reached, remains of earlier walls appeared under the floor foundation of the eastern aditus maximus and in the core of its southern wall. Further excavations below the collapsed northeastern section of the cavea exposed other earlier walls buried beneath it. In addition, excavations under the pulpitum pavement within the hyposcaenium down to the foundations revealed a solid platform that predated the Severan Theater. All these remains pointed to the existence of an earlier theater, presumably of the first century CE (Roman II, Stratum 13). In our quest after the nature, dimensions and type of this earlier theater, several probes were opened, first in the orchestra, then in several vomitoria, and finally in the core of the southern wall of the western aditus maximus. The accumulated data of these excavations, although fragmentary, left little doubt that beneath the Severan Theater were substantial remains of an even earlier theater, subsequently termed the Southern Theater. Two phases were clearly observed, both of

which are attributed to Stratum 13, the first during the first quarter and the second during the fourth quarter of the first century CE. In most places, the builders of the Severan Theater, during the late second and early third centuries CE, covered over the Southern Theater units, sometimes founding new walls upon the earlier foundation platforms. As the Severan Theater foundations penetrated deeply, and as this later complex could not be removed, only limited probes could be executed and no clean and conclusive loci of the Southern Theater phases were obtained. Thus, the dating of the Southern Theater’s phases is based mainly on its relative stratigraphy, architectural analysis, the nature of its masonry and the study of some of its architectural elements that were uncovered in foundation fills of the Severan Theater (see Chapter 9). The remains of the Southern Theater were revealed in excavations below the hyposcaenium, aditus maximi, the orchestra and Vomitoria 10–11 and 14–15 of the Severan Theater (Plan 2.1) Their locations are therefore described according to the Severan Theater units in which they were revealed, although these do not correspond to the Southern Theater units in either of its phases (see Plan 3.1). The following report describes all the remains revealed during the excavations that can be attributed to the Southern Theater. The theater was founded in Phase I, and in Phase 2, it was enlarged (for the architectural analysis of both phases, see Chapter 7).

The Southern Theater: Phase I Beneath pavement remains and foundation layers containing clay pipes and a drainage channel in the western part of the eastern aditus maximus, a corner of two walls (W2205, W2206) was revealed, preserved to eight courses high, forming a well-constructed foundation platform (-155.32/-158.22; Plans 2.1– 2.3; Fig. 2.1). Wall 2205, running east–west, was first exposed in a 13 m long section, and two more

10

Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

W2109

1

4

W2160

W2206

2

W2205

W2221

5

Vomitorium 2

4

W2191 W2192

W2190

rium 3 Vomito

W2194

3

Vomitorium 18

Vomit or

ium 17

Vomit or

ium 16

2

4 ium

Vo m

Vo m

ito

14

riu

m

15

m

m

riu

ito

riu

ito

13

12

Vomi torium 8 Vomito rium 9

m

m Vo

m Vo

W70727

ito

riu

11 rium

to Vomi

Severan Theater

644

Southern Theater Phase II

W70

10

Southern Theater Phase I

W70643

20 m

0

25

W706

W70617

Vomitorium

Vo mi tor Vo mi ium tor 6 ium 7

W

60

76

tor mi 5 Vo ium tor i m Vo

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Proscaenium Hyposcaenium Scalarium I Cuneus 1 Aditus Maximi Orchestra

Plan 2.1. Southern Theatre: Phases I and II (superposed on the plan of the Severan Theater).

sections of it were later revealed to the west under the orchestra pavement (see below), thus reaching a length of 24 m (see Plan 2.3). At its eastern end it created a corner with W2206, of which a 2.6 m long stretch was revealed running southward, where it passed under the southern wall of the aditus maximus (W2194). Wall 2206 was preserved up to 10 courses high (-154.65; Plan 2.2: Section 1-1; Fig. 2.2). A narrow trench along W2205 was excavated in a compacted fill of

basalt stones and gray soil (L1267). At level -158.22, a foundation layer of small to medium-sized basalt stones was reached. As the area of the probe was too narrow for deeper excavation, the foundation trench could not be exposed and the date of the foundation layer could not be confirmed. Both W2205 and W2206 were meticulously constructed of well-cut and dressed basalt stones laid in alternating courses of headers and stretchers (see Fig. 2.1). The masonry courses were

Chapter 2: The Southern Theater

Fig. 2.1. Southern Theater, Phase I: Wall 2205 and its corner with W2206, looking south.

c. 0.35 m high and stepped, each course protruding c. 4 cm from the one above it. The inner core of the corner was constructed of medium-sized, roughly cut basalt stones set in hard, light gray mortar. Under the aditus maximus floor, the corner was preserved to 2.54 m high, and under W2194, to a height of 3.27 m When the foundation of the aditus maximus’ floor of the Severan Theater was built, which incorporated pipes and a drainage channel, the upper courses of W2205 and W2206 were partly dismantled. A probe was opened in the northeastern corner of the Severan Theater orchestra (L1069). At a level of -154.93 (see Plan 2.3), the upper courses of the westward continuation of W2205 further west were exposed. Another probe along the northern face of W2205 in this location (L50645) revealed its foundations resting upon the bedrock. Four stepped, well-cut and dressed basalt masonry courses, each about 0.3 m high, of the wall were revealed. The foundation course of W2205 is higher in the orchestra probe, indicating that the bedrock rose from east to west. This foundation course was built into a foundation trench hewn into bedrock, and protruded some 0.25 m from the outer face of the superstructure. Some fragmentary Roman-period sherds were revealed in the foundation trench (L1072).

Fig. 2.2. Southern Theater, Phase I: Wall 2206 runs under W2194, looking south.

11

12

Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

0

4

1

m

W2196 L60636 W2205 -154.96

-158.22

Aditus maximus

W2206

2

L1267

-155.32

W2191

L1253

L1257

W2190

2

W2192

W2194

-149.00

-149.85

1

L1240 L1281 -154.76 -150.55

-148 W2191

-150 -152

W2190

L1240 L1253 L1257 L1281

W2194

W2196

-154 -156

Southern Theater Phase I

W2206

1-1

W2205

-158 -148

Southern Theater Phase II Severan Theater

W2191 W2192

-150 W2194

-152 -154 -156

W2205 W2206

2-2

Plan 2.2. Southern Theater: Phase I and II wall remains within the eastern aditus maximus of the Severan Theater.

0

W2046

4 m

L50645

-156.95

Orchestra

W2109

L1124

L1072

-154.93

W2160

L1114

-157.10

W2205 -155.32

Hyposcaenium

W2190

Acoustic Cell

W2191

Severan Theater

Southern Theater Phase II

W2192

Aditus Maximus

Southern Theater Phase I

W2206

Plan 2.3. Southern Theater walls: Phase I and II wall remains under the eastern aditus maximus, orchestra and hyposcaenium of the Severan Theater.

W2079

Chapter 2: The Southern Theater

13

14

Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

Fig. 2.3. Southern Theater, Phase I: Wall 2205 exposed in a probe at the center of the orchestra, looking south. Fig. 2.4. Southern Theater, Phase I: Severan Theater cavea collapse removed, revealing earlier walls, looking south.

Fig 2.5. Southern Theater, Phases I and II: Wall 2190 in the rear and W2191 in front, under the Severan Theater ima cavea, looking south.

Another probe conducted along the central axis line of the orchestra (L50639) revealed the continuation of W2205 further west. Construction of the Severan Theater’s central drainage channel cut W2205, which was otherwise well preserved (-156.15). Four courses of fine basalt masonry of W2205, each about 0.3 m high, were exposed in the probe (see Plan 2.3; Fig. 2.3). The 0.8 m wide space between W2205 and the Severan Theater proscaenium wall (W2046) was excavated

throughout, revealing a foundation (L50645) containing no diagnostic pottery. The northeastern segment of the ima cavea of the Severan Theater collapsed during the earthquake of 749 CE. Prior to restoration work, the collapsed layer, composed of hard-limestone cavea seats and their basalt stone foundation, was removed and the fill below was excavated (Fig. 2.4). Within the fill, two walls were revealed, W2190 in the south and W2191 in the north

Chapter 2: The Southern Theater

(see Plan 2.2: Section 1-1; Fig. 2.5) and the area in between the walls, 0.75–0.90 m wide, was excavated. The upper part of the fill was sealed by a layer of small and medium-sized basalt stones set in hard gray mortar (L1240). Under it, soft-limestone architectural elements were embedded in a compact fill (L1281), including two joining fragments of a Corinthian capital (A40627, A40628), a fragment of an Ionic capital (A40630), a fragment of an architrave (A40632) and three column drums (A40642–40644), all presumably originating from the Southern Theater’s scaenae frons columnar facade. The fill and its embedded architectural elements were removed (L1257) and a foundation layer of small basalt stones set in dark gray mortar was exposed (L1253) and further excavated in a limited area (-154.35/-154.56). This foundation layer seems to have been attached to W2190 in the south and extended under W2191; its northern continuation was cut by the later W2194. No pottery was associated with the foundation layer, thus no data confirmed the dating of the walls (see Plan 2.2: Section 1-1). Wall 2190 of Phase I was preserved in a 2.7 m long segment and 0.4 m of its (unknown) width was exposed. It had a basalt stone foundation with a relating floor foundation at level -154.76. The superstructure was built of well-cut and dressed, softlimestone masonry, and preserved to a height of 4.21 m (-150.55) at its eastern end. The upper courses of the wall sloped down from east to west and its uppermost course sloped toward the north and seems to have been the springer course of a sloping barrel vault. The northern wall of the Southern Theater’s eastern aditus maximus was apparently dismantled entirely when the eastern aditus maximus of the Severan Theater was built. It is reasonable to assume that the northern wall of the Southern Theater’s aditus maximus in Phase I was erected over W2205 and W2206. That would determine the width of the Southern Theater’s aditus maximi, although no remains of its superstructure were preserved.

The Southern Theater: Phase II The excavations of the hyposcaenium of the Severan Theater revealed several renovation stages of the drainage system and the system of supporting arches under the pulpitum floor. In the lowest layer of the hyposcaenium, a c. 6.5 m wide foundation platform (W2109) was revealed along the east–west axis of

15

Fig. 2.6. Southern Theater, Phase II: foundation W2109 under the Severan Theater pilasters, looking south.

the hyposcaenium at level -156.95/-157.10 (see Plans 2.1, 2.3). It was constructed of well-cut and dressed basalt stones in its southern face, while its northern side rested against bedrock and its inner core contained small to medium-sized, cut but not dressed basalt stones in hard, dark gray mortar (Fig. 2.6). Although the flat surface of the foundation platform (W2109) was revealed, there were clear indications that it originally reached somewhat higher, and that about three of its upper courses had been later dismantled. This foundation platform was reused for the arch system of the Severan Theater’s hyposcaenium that was built over it in Stratum 12 (see below; see also Chapter 7). The excavation of the cavea foundation of the Severan Theater and its eastern aditus maximus walls

16

Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

revealed two components of the Southern Theater that are related to Phase II, the southern wall of its eastern aditus maximus (W2191) and sections of its cavea circumference wall (see below W2192 = W60762/ W70617, W2221). Wall 2191 was preserved in a segment 13 m long, 1.2 m wide and 4.91 m high, its upper course reaching level -149.85 (see Plan 2.2: Section 1-1). It was connected in the east to W2192 that protruded northward some 0.4 m from their connection line, and its stepped courses declined toward the west. Wall 2191 had two basalt stone foundation courses and its superstructure was built of soft-limestone masonry. It had a well-built northern face and a broken southern one, presumably as it was originally built into the cavea core of the Southern Theater in Phase II and was not meant to be seen. The wall was built over the Phase I foundation and upon the southern wall (W2190) of the eastern aditus maximus of the Southern Theater in Phase I, which was obviously buried beneath its cavea. As a result of the earthquake of 749 CE, a c. 6.6 m wide section of the basalt stone face of W2194 of the Severan Theater eastern aditus maximus collapsed, presumably at a weak spot. Behind the collapsed masonry face, the inner core was exposed (see Plan 2.2: Section 2-2), revealing a segment of an earlier wall that had been integrated into the inner core of the later wall. This was the northeastern corner of W2192, 2.4 m wide (Fig. 2.7), which continued further south within the ima cavea foundation core. It was built of mediumsized to large stones in dark gray mortar to a height of 4.6 m. The lower courses of W2194 covered the lower part of W2192, but it most certainly continued further down, presumably to the upper level of W2206 (-154.65) and thus its preserved height reached 9.43 m. The currently exposed lower three courses (1.05 m high) were constructed of well-dressed basalt masonry in alternating courses of headers and stretchers and they shared the same height and construction method as those of W2205 and W2206. The upper courses (3.55 m high) of the wall were built of well-cut and smoothly dressed soft-limestone (nari) masonry of varying heights (0.37–0.97 m) that were presumably plastered. As they were covered by the later aditus maximus wall, they were relatively well preserved (see Fig. 2.7). The northwestern end of the semicircular circumference wall of the Southern Theater cavea in Phase II (W2221) was also observed within the core

of the southern wall of the Severan Theater’s western aditus maximus, whose outer face had partly collapsed as well (see Plan 2.1; Fig. 2.8). Since the collapse of this wall face was not as severe as that of the eastern aditus maximus, only the upper part of W2221 was partly exposed. However, its width, height and construction technique were undoubtedly the same as those of W2192. Based on the assumption that W2192 and W2221 were the two northern ends of the Southern Theater’s semicircular circumference wall of its cavea in Phase II, two probes were conducted along its assumed route in two of the Severan Theater’s vomitoria (Plan 2.4:2, 3). In the northern part of Vomitoria 14–15, W60762 was revealed under the floor (-146.83) as it ran across both passages (L70614). Its exposed segment, 6.85 m long and 1.7 m wide, ran under the side walls of the vomitoria as it continued in both directions (Fig. 2.9). It was built of small to medium-sized basalt stones, mostly laid in headers, with an inner core of small stones held in hard, dark gray mortar. It was also revealed under Vomitoria 10–11 (W70617) as it continued westward (see Plan 2.4:3). As the plan of these walls was drawn, it became obvious that all of these wall segments (W2192, W60762, W70617 and W2221) were part of one semicircular wall that surrounded the ima cavea of the Southern Theater in Phase II. In the fill over W60762 (L70614), Roman, Byzantine and Mamluk pottery was recovered, along with two coins of the third century CE (Coin Cat. Nos. 84, 165) and one of the Mamluk period (Coin Cat. No. 825). Attached to W70617 on both its southern and northern faces in Vomitoria 10 and 11, scanty remains of perpendicular foundation walls were revealed (L70651). In the east, W70644, preserved in an 8.2 m long section, ran north–south perpendicular to W70617 (Figs. 2.10, 2.11). Parallel to it, 2.4 m to the west, a 3.5 m long section, 2.3 m wide, of W70643 was attached to W70617; it ran across the vomitorium connecting passage. Wall 70625, 3 m long, continued W70643 northward (see Plan 2.4:3: Section 1-1; Fig. 2.12). All of these walls were reused as foundation courses of the vomitoria walls of the Severan theater, and they were all covered by the floor foundations of the vomitoria. In the south, 8.3 m from W70617, another semicircular wall (W70727) was found (L70756), presumably the semicircular perimeter wall of the Southern Theater’s summa cavea in Phase II (Fig. 2.13). It was 2 m

Chapter 2: The Southern Theater

17

Fig. 2.8. Southern Theater, Phase II: Wall 2221, the circumference wall, integrated into the core of the Severan Theater’s western aditus maximus wall, looking southwest.

Fig. 2.7. Southern Theater, Phase II: the northeastern corner of W2192, looking south.

Fig. 2.9. Southern Theater, Phase II: Wall 60762, the Southern ► Theater’s circumference wall, under the foundations of the Vomitoria 14–15 passages, looking east.

wide, built of large, well-cut basalt stones in the same technique as the other walls of the Southern Theater, and its upper level was -145.99. All these walls were preserved up to two, 0.4 m high courses; the first course, protruding c. 0.15 m from that above it, was embedded into a foundation trench and held in hard, dark gray mortar. Attached to them were scanty remains of pavement foundation layers, presumably of the Southern Theater’s vomitorium floor (-146.18), which was somewhat lower than the side-wall foundations of the Severan Theater’s vomitorium and ran below them. The fragmentary remains of the pavement foundation were discerned in both Vomitoria 10 and 11, and they

18

Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

10 m

0

1

Scalarium I

1

W2192

W2191

Cuneus 1

0

2

2

m

3 2

1

1 W7064

1 rium 1 Vomito 25 W706

0

W70617

44

W70640

-146.18 7

W7072

-146.83

W6

076

2

m

-145.99

1

L70614

2

L70651

L70756

Vomitorium 15

0

m 10

2

u Vomitori

W70642

Severan Theater

W706

W70643

-146.83

Phase II

W70639

3

Vomitorium 14 W70641

W70640

-145 -146

W70727

W70643

W70617

W70625

-147 -148

1-1 Plan 2.4. Southern Theater walls: Phase II wall remains under Severan Theater units: (1) scalarium I and Cuneus 1; (2) Vomitoria 14–15; (3) Vomitoria 10–11.

m

Chapter 2: The Southern Theater

Fig. 2.11. Southern Theater, Phase II: a section of W70644 under the later vomitorium wall, looking east.

Fig. 2.10. Southern Theater, Phase II: two basalt courses of W70644 under the later vomitorium wall, looking north.

Fig. 2.12. Southern Theater, Phase II: Wall 70625 built over bedrock, extended northward to the later vomitorium foundations, looking north.

Fig. 2.13. Southern Theater, Phase II: the circumference wall (W70727), looking west.

19

20

Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

were observed to the north of W70617, reaching the western, inner face of W70625 further north. Below it was a compact fill of basalt stones and soft-limestone chips mixed with crumbled travertine, but no pottery. All these foundation walls of the Southern Theater were built of smaller basalt masonry than those of the Severan Theater, they were constructed into foundation trenches hewn into the sloping bedrock of the northern hillside, and they were all superimposed by the Severan Theater vomitorium walls (W70639, W70641 and W70640). Assuming that these were the Southern Theater’s vomitorium and circumference walls in Phase II, its plan and dimensions could be reconstructed (see Chapter 7).

Concluding R emarks Although the remains of the Southern Theater were by their nature fragmentary, revealed mainly in investigative probes of limited scale, the probes were located throughout the theater, thus yielding the widest possible evidence and detailed data for clarifying its plan, construction phases and date. The largest segments were exposed under the eastern aditus maximus and the attached cavea section of the Severan Theater, where important evidence of its plan in both phases was obtained. This enabled us to choose the optimal locations for additional probes in order to further clarify the details of the plan and the phases of the Southern Theater (see Plan 2.1; see Chapter 7). It is clear from the excavation results that the theater had two phases, although their dating could not be confirmed. As all the fills covering these remains resulted from the construction of the Severan Theater, the pottery recovered in them could not aid in their dating. The reuse and integration of the earlier foundation platform in the hyposcaenium of the Severan Theater further prevented any precise dating. The probes in the orchestra and the vomitoria contributed important architectural data of the Southern Theater’s plan in both phases, though not of its date. Furthermore, foundation trenches and floor foundations clearly associated with the Southern Theater yielded no datable pottery or coins. All that can be established

is that below the Severan Theater rested the remains of the Southern Theater, which clearly reflected two phases. The first had an ima cavea, while a summa cavea was added in the second phase, which enlarged both the aditus maximi and the scaena. Stratigraphy could only furnish a terminus ante quem, as both phases of the Southern Theater clearly preceded the Severan Theater built above. It can be reasonably assumed that the second phase of the Southern Theater was active until it was covered by the Severan Theater, and that the Southern Theater was erected in the first century CE as part of the civic center, although it is separate from the forum in both orientation and levels. The softlimestone architectural members that were found in the fills and were presumably part of the architectural decor of the scaenae frons of the Southern Theater are further analyzed in Chapter 9. The use of soft limestone as the preferred material for architectural members and wall masonry was observed elsewhere in the site, for instance in the forum basilica and temples dated to the first century CE. In the early second century CE, the Gilboa Mountain quarries were exploited, and the superb hard limestone that was quarried there became the preferred material for masonry and architectural elements, ultimately replacing the soft limestone, the use of which was reserved for very specific requirements such as marble-faced walls and plastered barrel vaults of thermae. Therefore, it seems clear that the wall masonry and soft-limestone architectural elements of the Southern Theater, in both its phases, must be dated to the first century CE. The assumed dating of their architectural style became crucial to a more precise dating of the Southern Theater phases. In Chapter 7, the fragmentary evidence from the excavations is assessed and related to the dating of the soft-limestone architectural elements. The construction of Phase I seems to date to the reign of Tiberius (14–37 CE), while Phase II, in which the theater was enlarged, is dated to the Flavian period (69–96 CE). The overall architectural analysis of the Southern Theater is presented and set within the typology of first century CE theaters in the region, which seems to validate the dating of its phases to the early and late quarters of the first century CE.

G. Mazor and W. Atrash, 2015, Bet She’an III/1 (IAA Reports 58/1)

Chapter 3

The Severan Theater Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

Introduction Excavations of the Severan Theater, first conducted by Applebaum in 1960–1962 and continued by the IAA expedition in 1986–2002, have uncovered the entire complex (Fig. 3.1; Plan 3.1). The current report follows the customary architectural division of Roman theaters into four subcomplexes: the scaena, the cavea, the aditus maximi and the orchestra. These major subcomplexes are in turn further divided into their specific units and subunits (see below),1 and the description and stratigraphic analysis of the theater complex follows this division. In each unit, the report begins with the

Severan construction stage of Stratum 12 (Roman III) and follows the unit’s renovation stages through Strata 11–9 (Roman IV–Byzantine II) and occasionally into Stratum 2 (Late Islamic/Mamluk period; Table 3.1). In the absence of a detailed stratigraphic report of Applebaum’s work, the meager data extracted from his preliminary reports, either published or in the IAA archives, are presented together with the research work of the IAA expedition. Applebaum’s observations regarding the dating of various construction stages of the theater are presented in full, and discussed whenever the new data raise questions concerning his conclusions.

Fig. 3.1. Severan Theater, looking northeast.

22

Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

Table 3.1. Subcomplexes and Units of the Severan Theater: Construction (+) and Renovation (++) Stages Subcomplex/Unit

Stratum 12

Stratum 11

Proscaenium

+

++

Pulpitum and Hyposcaenium

+

++

Stratum 10

Stratum 9

Scaena ++

Hyposcaenium approaches and staircases

+

Corridor and tunnel east of the hyposcaenium

++?

Pulpitum flanks Scaena’s central drainage system

+ +

++

Hyposcaenium drainage system Scaenae frons Scaenae frons podium

+ +

++

++ ++

+

Versurae

+

Postscaenium foundation

+

Postscaenium and entrances

+

++? ++?

Cavea Balteus

+

Ima cavea

+

Praecinctio

+

Media cavea

+

Vomitoria and acoustic cells

+

Summa cavea

+

Ambulacrum podium

++

++ ++

+

Aditus Maximi Eastern staircase

+

Eastern aditus maximus

+

Western aditus maximus

+

Orchestra

+

Applebaum presented a general field plan of the theater, which forms the basis of all our plans in this work. However, he did not prepare any detailed plans or sections of the theater’s subcomplexes and units. In the framework of the IAA expedition, these were remeasured and new plans and sections were drawn up according to the theater’s development stages (Plans 3.2–3.36). Applebaum’s photographs, whenever available, are integrated into the report, although most of the accompanying photographs were taken by the IAA expedition, and these thoroughly record the entire theater. Of the 1140 architectural elements that were recovered from the theater, over two-thirds (758; see Appendix 9.1:A6001–A6864) were found by Applebaum where they had collapsed over the pulpitum and the orchestra in the earthquake of 749 CE. As no detailed records of this collapse layer were made, the

++

++

++ ++

++

++

++

only available data must be extracted from Applebaum’s photographs. The remaining elements (382; see Appendix 9.1) were excavated by the IAA expedition in the theater and the civic center, and their find spots are accurately recorded in the report and in Appendix 9.1. Analysis of the pottery, glass artifacts and coins recovered in the theater by the IAA expedition accompany this excavation report. Unfortunately, artifacts found by Applebaum have been mostly lost and only occasionally were they mentioned by him. Those that were located in the IAA storehouses have been incorporated in the discussions here. The theater’s subcomplexes will be described as they were left by Applebaum, followed by some preservation works conducted by architect Max Tan’ee of the National Parks Authority in 1964–1965. The IAA expedition conducted further excavations in the

23

Chapter 3: The Severan Theater

26

10

A 7

8

6

5 3

9

22b

C

2

3

4 1

15 14

19

25

18

13

C

14

24 14 12

14 14

13

13

19

14

14 13

18 19

14

11

22a

19

13

14 19

9 15

D

13

23

18

8

7

13

13

19

18

16 19

19

19 18

B

18

18

18

17

0

A. Scaena 1. Proscaenium 2. Pulpitum 3. Pulpitum Flanks 4. Hyposcaenium 5. Scaenae Frons 6. Valvae Regiae 7. Hospitalia 8. Versurae 9. Itinera Versurarum 10. Postscaenium

20

21

20 m

B. Cavea 11. Balteus 12. Ima Cavea 13. Cunei 14. Scalaria 15. Tribunalia 16. Praecinctio 17. Media Cavea 18. Vomitoria 19. Acoustic Cells 20. Ambulacrum 21. Summa Cavea

C. Aditus Maximi 22a. Eastern Aditus Maximus 22b. Western Aditus Maximus 23. Western Staircase

D. Orchestra 24. Orchestra 25. Bisellia 26. Forum Temple II

Plan 3.1. Severan Theater subcomplexes and units.

scaena and versurae, which yielded stratigraphic data that clarified the construction stages and their dating.

The theater is presented by units within subcomplexes (Plan 3.1).

24

Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

Scaena The theater was constructed during the Severan Dynasty (193–211 CE). Shortly after its completion, sometime during the first half of the third century CE, the complex suffered serious constructional problems, as revealed in the aditus maximi and the scaena. The ima cavea, founded on the hill slope and over the buried remains of the Southern Theater, began to slide down the hill. In order to stop the slide, a huge wedge-shaped foundation was constructed deep into bedrock in front of the scaenae frons, and a postscaenium was constructed above it. New versurae were built and connected to the scaenae frons, which was somewhat shortened in the process. Also shortened in these reparations were the proscaenium and the pulpitum. The postscaenium’s flanking corridors were connected to the aditus maximi and the caveae sections, and the northern sides of the ima, media and summa caveae, as well as the upper porticus, were integrated with the versurae. As we do not know if the original scaena of the Severan period in Stratum 12 possessed a postscaenium, and as both the original construction and the reparation works were consecutive in date, presumably executed by the same architect and builder, they are considered as technical phases of the single original construction stage (Stratum 12). The scaena, 93 m long and 23 m wide, located to the north of the orchestra, included the pulpitum, which was the focal point of the scaena, bordered by the scaenae frons columnar facade in the north, the proscaenium in the south and both versurae in the east and west (see Plan 3.1), while the postscaenium stretched to the north of the scaenae frons and its inner corridors––northern, eastern and western––bordered the scaenae frons and the versurae. During Roman IV and Byzantine I–II (Strata 11– 9), the scaena underwent major renovations. It was lowered by a third following damages inflicted by the earthquake of 363 CE (Stratum 11), and again by another third in the early sixth century CE (Stratum 9). Throughout this span of time, however, the scaena retained its basic plan and components. The theater served as an active auditorium until Byzantine III (Stratum 8) and was later reused during Umayyad II (Stratum 5) as part of a large pottery workshop, some installations of which were found over its eastern

section (see Bet She’an II). In the earthquake of 749 CE, the scaenae frons collapsed over the pulpitum and orchestra (Figs. 3.2, 3.3), while the rest of the theater was hardly damaged. Applebaum reported the existence of Islamic-period buildings erected over the ruined scaena, dated generally to Strata 4–2. He dismantled them entirely and left no records, plans or photographs of their remains. The scaena was excavated by Applebaum, apart from its eastern part that was uncovered by the IAA expedition. The hyposcaenium was partly excavated by Applebaum and further exposed by the IAA expedition.

Proscaenium Stratum 12 The proscaenium wall (W2046) extended from east to west in front of the pulpitum (Plan 3.2). Its original length could only be estimated (see Chapter 7), as it was shortened later in Stratum 12 (see below). It was built of three masonry types (Fig. 3.4). Its foundation, 1.8 m wide, consisted of four basalt courses, 2.16 m high, the lowest foundation course protruding some 0.10 m on both faces. Over the foundation courses, a 0.25 m high, hard-limestone course was laid, its upper surface serving as the floor of the proscaenium niches. Above this course, the upper part of the wall, constructed of soft limestone (nari), was narrower, 1.6 m wide. Of its four original courses, two were preserved to a height of 0.71 m. In the lower course, basalt corbelling slabs were inserted into its northern face, opposite the line of abutments in the hyposcaenium (Fig. 3.4) that carried the supporting wooden beams of the pulpitum floor (see below). The southern face of the proscaenium was adorned with alternating niches, six rectangular and five semicircular. Remains of marble slabs and metal (bronze and lead) clamps indicated that the walls and floors of all the niches were covered with marble slabs. The upper surface of the wall, at the level of the pulpitum pavement, was paved with marble slabs with a plain cornice profile that followed the outline of the niches. Five fragments of these marble slabs were found (A6673a–e), although not in situ. The proscaenium was somewhat better preserved at either end than in its central part. In the center, a poorly preserved, semicircular niche divided the wall into two symmetrical sections with slight differences in niche sizes. The niches are described from east to west (see Plan 3.2; Fig. 3.5).

Chapter 3: The Severan Theater

Fig. 3.2. Severan Theater: 749 CE earthquake collapse of scaenae frons over pulpitum and orchestra, looking north.

Fig. 3.3. Severan Theater: 749 CE earthquake collapse of scaenae frons over western pulpitum, looking west.

25

W2088 W2114

Severan Theater

Southern Theater Phase II

W2101 -153.21 L1102

-154.11

W2102

11

-159

-158

-157

-156

-155

-154

-153

-152

-151

10

9

7

W2046

W2046

L1190 L1143

0

6 5

W2156 W2160

-154.30

4 m

3

L1296

4

L1128

W2109

2

L1140

W2204

L1142 L1187 L1195 W2079 L1263

1

W2056

W2109

L1142 L1187 L1195 L1263

W2160

-158.28

L1143 L1190

L1171

-158.28

1-1

T6

-153.00

Plan 3.2. Severan Theater: scaena in Stratum 12.

8

L50648

W2079

1 1

W2202

W2201

W2144

W2196

26 Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

Chapter 3: The Severan Theater

Fig. 3.4. Severan Theater: the inner face of proscaenium W2046 with inserted corbelling stones, after reconstruction (1987–1989), looking southwest.

Fig. 3.5. Severan Theater: the proscaenium niches, looking northeast.

27

28

Gabriel Mazor and Walid Atrash

Niche 1: Rectangular niche (0.60 x 0.92 m), 1.25 m west of W2204, preserved to a height of 0.71 m with remains of a marble-slab floor (-154.26). Niche 2: Semicircular niche (D/R 1.15/0.50 m), 1.25 m from the former, two courses preserved (-153.59/ -154.31) with mortar remains (Fig. 3.6). Part of the marble floor of the niche was found in situ (-154.20). A fragment of a rectangular marble slab (0.11 × 0.75 m, 2 cm thick) bears the remains of a two-line inscription, the upper of which has six letters, 4 cm high; the lower has nine letters, 5 cm high: …∆] ΤΟΝ ΤΟ ΤΙΜΟΘΕΟΥ [Τ …Timoteus... At the beginning of the inscription, a decorated leaf was carved, whose roundness fits the niche’s contour (Fig. 3.7). Niche 3: Rectangular niche (0.75 × 0.90 m), 1.15 m west of the former, one course of its wall preserved (-153.80/-154.30).

Fig. 3.6. Severan Theater: the proscaenium, Niche 2 with remains of marble-slab floor, looking north.