Pineapple Town: Hawaii [Reprint 2020 ed.] 9780520316119

224 76 43MB

English Pages 180 [176] Year 2021

Recommend Papers

![Pineapple Town: Hawaii [Reprint 2020 ed.]

9780520316119](https://ebin.pub/img/200x200/pineapple-town-hawaii-reprint-2020nbsped-9780520316119.jpg)

- Author / Uploaded

- Edward Norbeck

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

Pineapple

Town

HAWAII

Edward Norbeck

Pineapple Town

University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles 195»

HAWAII

University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California Cambridge University Press London, England Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 59-5745 © 1959 by the Regents of the University of California Printed in the United States of America Designed by Ward Ritchie PUBLISHED WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF A GRANT FROM T H E FORD FOUNDATION

I To My Wife

|

Preface

This book is an account of a Hawaiian pineapple plantation and the community in which its employees live. Its aims are not solely descriptive. The company town represents a class of communities with distinctive characteristics. An attempt is made to outline these traits as they are revealed in the pineapple plantation community of Maunaloa, Molokai, and to point out factors which have brought them into existence. The influence of techniques of pineapple husbandry and the demands of industrial employment upon the lives of employees and their families are explored analytically with special emphasis on the changes which time has brought. Observations are made also on the characteristics of Hawaiian pineapple plantation communities as a group. I am well aware that no single pineapple town of Hawaii is truly typical of all. Each is distinctive, but all have much in common. All are "owned" and operated by business corporations, a condition which profoundly affects community life and social relationships. All have been shaped in varying detail but common outline by circumstances peculiar to Hawaii. All have common problems and have been similarly affected by changing socioeconomic conditions of Hawaii and the rest of the world. What is true of Maunaloa is in large measure true of all other Hawaiian pineapple towns. The data assembled here were derived in part from five years of service, from 1938 to 1943, as an administrative employee of Libby, McNeill and Libby, the corporation which operates Maunaloa plantation. During most of this period I lived in Maunaloa or one of two other plantation towns of the corporation on the islands of Oahu and Maui. In the course of my work I visited Maunaloa often, and I resided there continuously for fifteen months during 1940 and 1941. Military service took me away from Hawaii in 1943, and I did not see Maunaloa again until late 1946, when a visit of a few weeks gave me some idea of postvii |

viii |

Preface

war conditions. After an absence of ten years, I next returned to Maunaloa in 1956, during the summer vacation from my teaching duties as an anthropologist at the University of California at Berkeley. Many of the data I have used were gathered by my wife and myself at this time. Some knowledge of plantation communities other than those in which I have resided was gained during the period from 1938 to 1942 by brief visits, often social in nature, to most of the other Hawaiian pineapple towns. In 1956 officials of several plantations were interviewed regarding the industry in general, and factual information on personnel and mechanization was gathered for comparative purposes on four plantations in addition to Maunaloa. Writers of books such as this customarily veil the identity of the community as a means of protecting both the people described and themselves. I have not attempted to do so because no Hawaiian pineapple plantation community can be made truly anonymous. Even a slight knowledge of the Hawaiian Islands makes identification easy. So far as possible, however, the identity of persons mentioned in these pages is concealed. Certainly I shall make no ethical judgments concerning them. The moral attributes of the people described are of concern to the objectives of this study only as they affect relations among the people themselves. Such ethical judgments as appear here are included because they are thought to shed light on attitudes and interpersonal relations. All represent the sentiments of the people themselves and are so identified. For statements that may appear unflattering, I am truly concerned and wish to assure the reader that no censure or condemnation is intended on my part. For errors in fact I offer sincere apologies. I owe hearty thanks to the management of Libby, McNeill and Libby for permission to pursue this study in 1956, for allowing my family and myself to reside in the plantation community, and for providing other useful aid. The privilege of access to records maintained by the plantation on personnel and other matters was particularly helpful, yielding a rapid and rich harvest of vital information which would otherwise have required many weeks of effort to collect. I am warmly grateful to the employees of the plantation and other residents of the community, many of whom were old friends at the time of our residence in 1956, for companionship as well as for patience in answering our many questions. Special thanks are due Mr. and Mrs. Harry W. Larson and Mrs. Sally Sunn for many things. I am indebted to the Committee on Research of the University of California at Berkeley for financial support.

Contents I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX

Introduction The Plantation The Community The Filipinos The Japanese Haoles and Cosmopolitans Community Social Relationships Technological and Social Change Summary and Conclusions Index

1 16 41 57 86 105 117 134 152 157

IX

Illustrations (following page 114)

Family group, three generations At the beach, summer educational program Newly planted fields Planting Mechanical harvester Mechanical harvester showing conveyer belt Houses in Filipino Camp House on "The HillI»

|

Maps

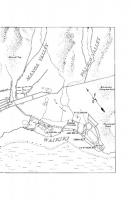

The Hawaiian Islands Island of Molokai The Community of Maunaloa

3

11 44

XI

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Tables

Year-round employees, Maunaloa plantation Literacy and years of education of hourly employees Age of hourly employees Marital status of male Filipino employees Racial-cultural composition of Maunaloa Cosmopolitans of Maunaloa Parentage of Cosmopolitan children Ancestry of Cosmopolitan children Cosmopolitan unions Plantation production Minimal and maximal numbers of hourly employees, 1936-1956 12 Annual hours worked by hourly employees

xii |

26 28 30 30 41 112 112 113 115 138 139 140

I

Introduction

Little about the Hawaiian pineapple plantation may be called truly indigenous. The crop is an alien from South America; most of the employees are recent migrants from other lands or the offspring of unions between immigrants and native Polynesians; and operation of the plantations follows precedents long established in other parts of the world. Even the soil, treated for years with foreign nutrients and other chemicals, may hardly be described as aboriginal. But nativeness in human culture is everywhere relative, a composite derived from many sources and molded into distinctive form. The Hawaiian pineapple plantation and the community associated with it are surely indigenous in the sense that their duplicates may not be found elsewhere. They have a unique flavor arising from the local conditions under which they emerged and grew. The pineapple industry of Hawaii has had only a brief history, but today it represents a level of scientific and commercial development of horticulture seldom reached elsewhere. Pineapples were introduced to Hawaii early in the nineteenth century, but commercial cultivation and canning did not begin until much later, just after the turn of the twentieth century. Growth of the industry under the impetus of an expanding world market was rapid, and pineapple production had become large-scale by the third decade of the century. By this time the success of pineapple as an industrial crop had attracted the attention of mainland fruit-packing corporations, which established plantations in Hawaii during that decade. Second only to sugar in importance in the economy of the Islands, the annual Hawaiian production of pineapples comprises about threefourths of the world total. The annual gross revenue exceeds $100,000,000, derived from the cultivation of approximately 73,000 acres. The industry provides year-round employment for about 6,000 regular em1 I

2 |

Introduction

ployees and 4,000 intermittent employees. During the summer months, an additional 10,000 or more persons are engaged. Thus the peak employment is approximately 20,000 workers. Pineapples are raised on fourteen plantations on the islands of Oahu, Maui, Kauai, Molokai, and Lanai, and canned on the islands of Oahu, Maui, and Kauai, each of which has three canneries. Fruit raised on Molokai and Lanai is shipped by barges to Honolulu for canning. Plantations are owned and operated by nine corporations, two of which are mainland concerns and account for over 40 per cent of the total annual production. All corporations, Hawaiian and mainland, jointly support an extensive program of cooperative agricultural research carried out by the Pineapple Research Institute, which is staffed by highly trained specialists. Reported to have an annual operating budget of about $1,000,000, it is one of the largest, privately financed agronomical research institutes in the world. At the beginning of the twentieth century the incipient industry was faced with the problem of developing techniques of husbandry to allow extensive and profitable cultivation. This problem was quickly met under the economic conditions of the time. Profitable techniques of pineapple culture were developed early, and the market continued to expand. The subsequent history of plantation husbandry has seen much change and development, with both the Pineapple Research Institute and the independent research of plantation companies contributing to the solution of problems as they arose. Improved technology has averted at least two imminent crises, the second of which led eventually to profound social changes in the plantation communities. In the late 1920's the industry was threatened by a serious disease of pineapple plants called mealy bug wilt. The Pineapple Research Institute developed measures of control in time to avert catastrophe, and mealy bug wilt is no longer considered a serious problem. A second threat emerged at the end of World War II. Faced with swollen production costs and heavily increased competition from foreign pineapple and mainland fruits, the industry found itself in a critical position. Hourly rates for laborers had mounted steadily, from 25 cents in 1939 to a minimum of $1.24 for adult males in 1956. Virtually all raw materials and machinery were imported, and the industry's own product had to be exported at high rates of ocean freight.

•B

a

S TS M

o

Z> < X

ui

![Hawaii: Islands under the Influence [Reprint ed.]

0824815521, 9780824815523](https://ebin.pub/img/200x200/hawaii-islands-under-the-influence-reprintnbsped-0824815521-9780824815523.jpg)