British Satire, 1785-1840, 5-Volume Set 9781851967292, 9780429348143

This set offers a representitive collection of the verse satire of the Romantic period, published between the mid-1780s

225 7 58MB

English Pages 2172 [2177] Year 2022

Main Cover

Volume 1

Cover

Half Title

Title

Copyright

Contents

List of illustrations

Acknowledgements

General Introduction

Editorial Principles

Introduction

‘The Holy Fair’ (1786)

‘A Specimen of Modern Female Education’ (1788)

‘The Lady and the Doctor; An Anecdote’ (1788)

‘Sweet Meat Has Sour Sauce’ (1788)

‘Pity for the Poor Africans’ (1788)

‘A Poem, On the Supposition of an Advertisement Appearing in a Morning Paper, of the Publication of a Volume of Poems, by a Servant Maid’ (1789)

‘A Poem, On the Supposition of the Book Having Been Published and Read’ (1789)

‘Song, by Mr. Paine’ (1791)

‘Ode to Burke’ (1792)

‘Burke’s Address to the “Swinish Multitude”’ (1793)

‘King Chaunticlere; or, The Fate of Tyranny’ (1793)

The Pernicious Effects of the Art of Printing Upon Society, Exposed (c. 1793–94)

‘Wonderful Exhibition. Signor Gulielmo Pittachio’ (1794)

‘No. II. More Wonderful Wonders!!!’ (1794)

‘Wonderful Exhibition!!! Positively the Last Season of His Performing’ (1795)

‘Fire, Famine, and Slaughter: A War Eclogue’ (1798)

‘The Laird o’ Cockpen’ (c. 1798)

‘When Klopstock England Defied’ (c. 1797–1800)

‘The Mistletoe, A Christmas Tale’ (1799)

‘The Confessor, A Sanctified Tale’ (1800)

‘A Poet’s Epitaph’ (1800)

‘To Matthew Dodsworth, Esq. On a Noble Captain’s Declaring that his Finger was Broken by a Gate’ (1802)

‘Badinage. On Recovering from a Bad Fit of Sickness at Bath’ (1802)

‘Ambubaiarum Collegia, Pharmocopolæ’ (1803)

‘A Farce in One Act, Called THE INVASION OF ENGLAND’ (1804)

‘An Ensorian Essay on Something, Meaning Any Thing, and Proving Nothing’ (1812)

Eighteen Hundred and Eleven, A Poem (1812)

‘The Triumph of the Whale’ (1812)

‘Recreation’ (1816)

‘Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream’ (1817)

‘To Belinda’ (1818)

‘Rights of Women. Answer to Florio’ (1818)

‘An Ode to the Ladies on their Alledged Rights’ (1818)

‘A Scene from the New Tragi-Comedy entitled the “Undebauched Royalists”, or, The Reformers Routed’ (1819)

‘The Peterloo Man’ (1819)

‘Sonnet: England in 1819’ (1819)

‘A New National Anthem’ (1819)

‘Non Mi Ricordo!’ (1820)

‘The Irish Avatar’ (1821)

‘The Magic Lay of the One-Horse Chay’ (1824)

‘Specimens of a Patent Pocket Dictionary’ (1824–25)

‘Ode to Mr. Graham, The Aeronaut’ (1825)

‘An Address to the Very Reverend John Ireland, D.D. Charles Fynes Clinton, LL.D. Thomas Causton, D.D. Howel Holland Edwards, M.A. The Bishop of Exeter. Wm. H. Edward Bentinck, M.A. James Webber, B.D. William Short, D.D. James Tournay, D.D. Andrew Bell, D.D. George Holcombe, D.D The Dean and Chapter of Westminster’ (1825

‘Discovery of Another Poet’ (1825)

‘The March of Intellect: A New Song (1825)

From The March of Intellect: Fashionable, Mechanical, Philosophical, Philanthropical, Professional, Political (1829)

‘Song: Child, is thy father dead?’

‘Burns, from the Dead’

‘The Jacobin’s Prayer’ (1830)

The March of Intellect, A Comic Poem (1830)

‘A Notabil Ballad of ye Downefall of Kynges’ (1831)

‘A New Song, to be Sung by All Loyal and True Subjects’ (1832)

‘My Very Particular Friend’ (1834)

‘A Governess Wanted’ (1838)

‘The Wonderful Pill’ (1837)

‘The Fine Old English Gentleman. New Version. To be Said or Sung at All Conservative Dinners’ (1841)

Explanatory Notes

Volume 2

Cover

Half Title

Title

Copyright

Contents

List of Short Titles

Acknowledgements

Introduction

From Criticisms on the Rolliad (1784–85)

From The Pursuits of Literature (1794–97; 1798)

The Unsex’d Females (1798)

From All the Talents; A Satirical Poem (1807)

From The Epics of the Ton (1807)

From The Simpliciad (1808)

From English Bards and Scotch Reviewers (1809)

From The Modern Dunciad, A Satire (1814)

From Sir Proteus: A Satirical Ballad (1814)

From Christabess (1816)

From Oedipus Tyrannus, or, Swellfoot the Tyrant (1820)

From Peter Bell the Third (1819)

From Letters to Julia, in Rhyme (1820; 1822)

From The Cap and Bells, or The Jealousies (1819)

From Don Juan (1819–24)

From Khouli Khan (1820)

The Vision of Judgment (1821)

From The Tour of Doctor Syntax in Search of a Wife (1821)

From The Mohawks: A Satirical Poem with Notes (1822)

From The Age Reviewed (1827)

Explanatory Notes

Volume 3

Cover

Half Title

Title

Copyright

Contents

List of short titles

Acknowledgements

Introduction

‘The Lousiad, an Heroi-Comic Poem’ (1794–96)

‘Epistles from Bath; or Q.’s Letters to His Yorkshire Relations’ (1817)

‘The Queen’s Matrimonial Ladder, A National Toy, with Fourteen Step Scenes; and Illustrations in Verse, with Eighteen Other Cuts’ (1820)

‘The Press, or Literary Chit-Chat. A Satire’ (1822)

‘The Illiberal! Verse and Prose from the North!!’ (1822)

Explanatory Notes

Volume 4

Cover

Half Title

Title

Copyright

Original Title

Contents

Dedication

List of Short Titles

Acknowledgements

Introduction

A Note on the Text

Biographical Directory

The Satires of William Gifford

The Baviad; A Paraphrastic Imitation of the First Satire of Persius (1791)

The Mæviad (1795)

‘Imitation. Dactylics. Quintessence of all the Dactylics that ever were, or ever will be written’ (1797)

‘Imitation of Bion. Written at St. Ann’s Hill’ (1798)

‘Epistle to Peter Pindar’ (1800)

Satires on William Gifford

Modern Manners: A Poem. In Two Cantos (1793)

Out at Last (1801)

‘Lines on “The Baviad” and “The Pursuits of Literature”’ (1797; 1806)

Ultra-Crepidarius: A Satire on William Gifford (1823)

‘The Heroes and Heroines of the Baviad’: An Anthology of Della Cruscan Verse

‘Dedication’ and ‘Preface’ to The Florence Miscellany (1785)

‘Madness’ (1785)

‘To Wm. Parsons Esq.’ (1785)

‘To Mrs Piozzi, in Reply, Written on the Anniversary of her Wedding 25 July 1785’ (1785)

‘To May’ (1787)

‘To Melissa’s Lips’ (1787)

‘Address to Benedict’ (1787)

‘The Adieu and Recall to Love’ (1787)

‘To Della Crusca: The Pen’ (1787)

‘To Anna Matilda’ (1787)

‘To Della Crusca’ (1787)

‘To Anna Matilda’ (1787)

‘Elegy, Written on the Plain of Fontenoy’ (1787)

‘Stanzas to Della Crusca’ (1787)

‘To Anna Matilda’ (1787)

‘To Della Crusca’ (1787)

‘To Anna Matilda’ (1788)

‘Sonnet. On an Air Balloon’ (1788)

‘The Slaves. An Elegy’ (1788)

‘The African Boy’ (1788)

‘The Interview’ (1789)

‘To Leonardo’ (1789)

‘To Her Whom I Saw Weep’ (1789)

‘To the Nightingale’ (1789)

The Laurel of Liberty: A Poem (1790)

Ainsi va le Monde (1790)

‘To Laura’ (1790)

‘The Voice we Love’ (1790)

‘The Invitation. To Delia’ (1790)

‘Henry Deceived’ (1790)

‘To Emma’ (1790)

from The New Cosmetic, or the Triumph of Beauty, A Comedy (1791)

‘Epilogue, Written by Miles Peter Andrews, Esq. and spoken by Mrs Mattocks’ (1791)

Ode for the fourteenth of July, 1791, the day consecrated to freedom: being the anniversary of the revolution in France (1791)

‘Ode To Della Crusca’ (1791)

‘Rinaldo to Laura Maria’ (1791)

‘To the Muse of Poetry’ (1791)

‘Echo to Him Who Complains’ (1791)

‘Epilogue’ to The Rage (1795)

‘Epilogue’ (1797)

Appendices

1. ‘Proceedings of the Trial of Robert Faulder, Bookseller, (one of FORTY against whom Actions were brought for selling the Baviad), for publishing a Libel on John Williams, alias Anthony Pasquin, Esq.’ (1800)

2. A Letter to William Gifford, Esq. From William Hazlitt, Esq. (1819)

Explanatory Notes

Volume 5

Cover

Half Title

Title

Copyright

Contents

List of Short Titles

Acknowledgements

A Note on the Text

Introduction

From Epistles, Odes, and Other Poems (1806)

‘Epistle VI. To the Lord Viscount Forbes’

‘Epistle VII. To Thomas Hume, Esq. MD’

Corruption and Intolerance: Two Poems. With Notes, Addressed to an Englishman by an Irishman (1808)

The Sceptic: A Philosophical Satire. By the Author of Corruption and Intolerance (1809)

From The Examiner (1812)

‘Letter from ——— to ———’ [‘Parody of a Celebrated Letter’]

From The Morning Chronicle (1812)

‘Anacreontic: To a Plumasier’

‘Extracts from the Diary of a Fashionable Politician’

‘The Insurrection of the Papers. A Dream’

‘The Sale of the Tools’

Intercepted Letters; or, The Twopenny Post-Bag. To which are added, Trifles Reprinted. By Thomas Brown, the Younger (1813)

From The Morning Chronicle (1813)

‘LAW on our side’

‘Reinforcements for Lord Wellington’

From The Morning Chronicle (1814)

‘The Two Veterans’

From The Morning Chronicle (1815)

‘Epistle from Tom Crib to Big Ben’

From The Morning Chronicle (1816)

‘Fum and Hum, the two Birds of Royalty’

The Fudge Family in Paris. Edited by Thomas Brown, the Younger (1818)

From The Journal of Thomas Moore (1983)

‘Beware, ye bards of each degree’ (1818)

Tom Crib’s Memorial to Congress. With a Preface, Notes, and Appendix. By One of the Fancy (1819)

Fables for the Holy Alliance (1823)

From The Times (1826)

‘An Amatory Colloquy Between Bank and Government’

‘The Sinking Fund Cried’

‘All in the Family Way. A New Pastoral Ballad’

‘Ode to Sir T——s L—thb——ge’

‘The Millenium’

‘The Three Doctors’

‘A Vision. By the Author of Christabel’

‘A Dream of Turtle. By Sir W. Curtis’

‘Corn and Catholics’

‘Literary Advertisement’

From The Times (1827)

‘The Slave’

‘A Pastoral Ballad’

‘Wo! Wo!’

From The Times (1828)

‘The “Living Dog” and the “Dead Lion”’

‘Dante Redividus’

‘The Brunswick Club’

From The Times (1830)

‘Alarming Intelligence—Revolution in the Dictionary—One Galt at the head of it’

‘Advertisement’

From Memoirs, Journal, and Correspondence of Thomas Moore (1835–56) ‘Thoughts on Editors’ (1831)

From The Times (1832)

‘Tory Pledges’

‘Song of the Departing Spirit of the Tithe’

From The Times (1833)

‘Paddy’s Metamorphosis’

‘Love Song’

From The Irish Melodies, No. 10 (1834)

‘The Dream of Those Days’

The Fudges in England: being a sequel to the ‘Fudge Family in Paris’ . By Thomas Brown, the Younger, Author of the Twopenny Post-Bag’, etc., etc. (1835)

From The Morning Chronicle (1836)

‘The Boy Statesman. By a Tory’

‘Anticipated Meeting of the British Association in the Year 2836’

From The Monthly Chronicle (1838)

‘Announcement of a new grand Acceleration Company for the promotion of the Speed of Literature’

From The Morning Chronicle (1838)

‘Grand Dinner of Type & Co.’

‘Some Account of a New Genus of Church-man, called the Phill-Pot’

‘Songs of the Church. No. I. “Leave Us Alone”’

‘Songs of the Chuch. No. II’

From Bentley’s Miscellany (1839)

‘Thoughts on Patrons, Puffs, and Other Matters’

From The Morning Chronicle (1839)

‘New Hospital for Sick Literati’

From The Morning Chronicle (1840)

‘An Episcopal Address on Socialism’

‘Latest Accounts from Olympus’

Explanatory Notes

Index

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Steven E. Jones

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

BRITISH SATIRE 1785–1840 Volume 1 Collected Satires I: Shorter Satires

BRITISH SATIRE 1785–1840 General Editor: John Strachan Consultant Editor: Steven E. Jones Volume Editors: Nicholas Mason David Walker Benjamin Colbert John Strachan Jane Moore

BRITISH SATIRE 1785–1840 Volume 1 Collected Satires I: Shorter Satires

Edited by Nicholas Mason

First published 2003 by Pickering & Chatto (Publishers) Limited Published 2016 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX 14 4RN 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © Taylor & Francis 2003 All rights reserved, including those of translation into foreign languages. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or inany information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION DATA

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

A catalogue record for this title is available from the Library of Congress ISBN-13: 978-1-85196-729-2 (set) Typeset by JCS Publishing Services

DOI: 10.4324/9780429348143

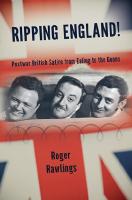

Figure 1: Seymour, ‘Poetry’, from The March of Intellect (1829) Source: Robert Seymour, The March of Intellect: Fashionable, Mechanical, Philosophical, Philanthropical, Professional, Political, London: Thomas M’Lean, 1829.

CONTENTS List of illustrations

xi

Acknowledgements

xiii

General Introduction by John Strachan

xv

Editorial Principles

xxvii

Introduction by Nicholas Mason

xxix

Robert Burns ‘The Holy Fair’ (1786)

1

Helen Leigh ‘A Specimen of Modern Female Education’ (1788) ‘The Lady and the Doctor; An Anecdote’ (1788)

11 15

William Cowper ‘Sweet Meat Has Sour Sauce’ (1788) ‘Pity for the Poor Africans’ (1788)

16 20

Elizabeth Hands ‘A Poem, On the Supposition of an Advertisement Appearing in a Morning Paper, of the Publication of a Volume of Poems, by a Servant Maid’ (1789) 23 ‘A Poem, On the Supposition of the Book Having Been Published and Read’ (1789) 26 John Wolcot (‘Peter Pindar’) ‘Song, by Mr. Paine’ (1791) ‘Ode to Burke’ (1792)

30 33

Thomas Spence ‘Burke’s Address to the “Swinish Multitude”’ (1793)

37

John Thelwall and Daniel Isaac Eaton ‘King Chaunticlere; or, The Fate of Tyranny’ (1793)

41

Daniel Isaac Eaton (‘Antitype’) The Pernicious Effects of the Art of Printing Upon Society, Exposed (c. 1793–94)

47

vii

British Satire 1785–1840, Volume 1

Anon. (attrib. to Robert Merry and Joseph Jekyll) ‘Wonderful Exhibition. Signor Gulielmo Pittachio’ (1794) ‘No. II. More Wonderful Wonders!!!’ (1794) ‘Wonderful Exhibition!!! Positively the Last Season of His Performing’ (1795)

56 62 63

Samuel Taylor Coleridge ‘Fire, Famine, and Slaughter: A War Eclogue’ (1798)

68

Carolina Oliphant (Lady Nairne) ‘The Laird o’ Cockpen’ (c. 1798)

74

William Blake ‘When Klopstock England Defied’ (c. 1797–1800)

77

Mary Robinson ‘The Mistletoe, A Christmas Tale’ (1799) ‘The Confessor, A Sanctified Tale’ (1800)

81 87

William Wordsworth ‘A Poet’s Epitaph’ (1800)

90

Anna Dodsworth ‘To Matthew Dodsworth, Esq. On a Noble Captain’s Declaring that his Finger was Broken by a Gate’ (1802) ‘Badinage. On Recovering from a Bad Fit of Sickness at Bath’ (1802)

95 98

George Canning ‘Ambubaiarum Collegia, Pharmocopolæ’ (1803)

102

Anon., from The Anti-Gallican; or Standard of British Loyalty, Religion and Liberty ‘A Farce in One Act, Called THE INVASION OF ENGLAND’ (1804)

109

Anon., from The Scourge ‘An Ensorian Essay on Something, Meaning Any Thing, and Proving Nothing’ (1812) 112 Anna Laetitia Barbauld Eighteen Hundred and Eleven, A Poem (1812)

118

Charles Lamb ‘The Triumph of the Whale’ (1812)

130

Jane Taylor ‘Recreation’ (1816)

134

John Keats ‘Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream’ (1817)

140

Anon., from The Black Dwarf ‘To Belinda’ (1818) ‘Rights of Women. Answer to Florio’ (1818)

143 147

viii

Contents

‘An Ode to the Ladies on their Alledged Rights’ (1818) ‘A Scene from the New Tragi-Comedy entitled the “Undebauched Royalists”, or, The Reformers Routed’ (1819) ‘The Peterloo Man’ (1819)

147 149 153

Percy Bysshe Shelley ‘Sonnet: England in 1819’ (1819) ‘A New National Anthem’ (1819)

155 157

William Hone ‘Non Mi Ricordo!’ (1820)

160

George Gordon, Lord Byron ‘The Irish Avatar’ (1821)

171

John Hughes ‘The Magic Lay of the One-Horse Chay’ (1824)

179

Horace Smith ‘Specimens of a Patent Pocket Dictionary’ (1824–25)

185

Thomas Hood and John Hamilton Reynolds ‘Ode to Mr. Graham, The Aeronaut’ (1825) 201 ‘An Address to the Very Reverend John Ireland, D.D. Charles Fynes Clinton, LL.D. Thomas Causton, D.D. Howel Holland Edwards, M.A. The Bishop of Exeter. Wm. H. Edward Bentinck, M.A. James Webber, B.D. William Short, D.D. James Tournay, D.D. Andrew Bell, D.D. George Holcombe, D.D The Dean and Chapter of Westminster’ (1825 211 Anon., from The Globe and Traveller ‘Discovery of Another Poet’ (1825)

215

Anon. (attrib. Theodore Hook) The March of Intellect: A New Song (1825)

219

Robert Seymour From The March of Intellect: Fashionable, Mechanical, Philosophical, Philanthropical, Professional, Political (1829)

224

Ebenezer Elliott ‘Song: Child, is thy father dead?’ ‘Burns, from the Dead’ ‘The Jacobin’s Prayer’ (1830)

229 232 233

W[illiam] T[homas] Moncrieff The March of Intellect, A Comic Poem (1830)

237

Anon., from The Prompter ‘A Notabil Ballad of ye Downefall of Kynges’ (1831)

250

ix

British Satire 1785–1840, Volume 1

John Wilson (‘Christopher North’) ‘A New Song, to be Sung by All Loyal and True Subjects’ (1832)

255

Maria Abdy ‘My Very Particular Friend’ (1834) ‘A Governess Wanted’ (1838)

261 264

George Cruikshank and Anon. ‘The Wonderful Pill’ (1837)

267

Charles Dickens ‘The Fine Old English Gentleman. New Version. To be Said or Sung at All Conservative Dinners’ (1841)

273

Explanatory Notes

277

x

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1: Seymour, ‘Poetry’, from The March of Intellect (1829) Source: Robert Seymour, The March of Intellect: Fashionable, Mechanical, Philosophical, Philanthropical, Professional, Political, London: Thomas M’Lean, 1829. frontispiece Figure 2: Gillray, ‘Anti-Saccharrites’ (1792) Source: The Works of James Gillray, from the Original Plates, London, Henry G. Bohn, 1851, plate 78.

22

Figure 3: Spence, cover from Pigs’ Meat (1794) Source: Frontispiece to Pigs’ Meat; or, Lessons for the Swinish Multitude, 2nd edn, London, T. Spence, 1794.

36

Figure 4: Gillray, ‘Doctor Sangrado Curing John Bull of Repletion’ (1803) Figure 5: Gillray, ‘Physical Aid’ (1803) Source: The Works of James Gillray, from the Original Plates, London, Henry G. Bohn, 1851, plates 274 and 275.

100 101

Figure 6: Cruikshank/Hone, ‘The Doctor’ from Man in the Moon (1820) Source: William Hone and George Cruikshank, The Man in the Moon, London: W. Hone, 1820, p. 20–21.

107

Figure 7: Gillray, ‘The King of Brobdingnag and Gulliver’ (1803) Source: The Works of James Gillray, from the Original Plates, London, Henry G. Bohn, 1851, plate 286.

108

Figure 8: Cruikshank, ‘The Prince of Whales’ (1812) Source: The Scourge, III, May 1812, p. 345.

129

Figure 9: Cruikshank, frontispiece to Non Mi Ricordo (1820) Figure 10: Cruikshank, ‘The Fat in the Fire’ from Non Mi Ricordo (1820) Figure 11: Cruikshank, ‘What are you at?’ from Non Mi Ricordo (1820) Source: William Hone and George Cruikshank, ‘Non Mi Ricordo!’, 5th edn, London, W. Hone, 1820, pp. frontispiece, 11, and 14.

159 169 170

Figure 12: Seymour, ‘Church Philanthropy’ from The March of Intellect (1829) 226 Figure 13: Seymour, ‘Philanthropy in Ireland’ from The March of Intellect (1829) 227 Figure 14: Seymour, ‘West India Philanthropy’ from The March of Intellect (1829) 228 Source: Robert Seymour, The March of Intellect: Fashionable, Mechanical, Philosophical, Philanthropical, Professional, Political, London: Thomas M’Lean, 1829. xi

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many students and colleagues deserve thanks for helping bring this volume to frui tion. I owe a particular debt to the four research assistants who have worked with me on this project, Matt Squires, Heather Robison, Paul Westover, and Jamie Davis. Without their assistance, I might very well still be in the microfilm room, scrolling through old newspapers trying to hunt down obscure references. I am also grateful to John Strachan and Mark Pollard for their editorial feedback and their assistance in locating source material. John deserves special thanks for introducing me to many of the texts ultimately included in this anthology and guiding this volume along from start to finish. My institution, Brigham Young University, has been remarkably generous in sup porting this project. In addition to the feedback and encouragement I have received from my colleagues in the English Department and the College of Humanities, I have also benefited from significant research funding. The staff at BYU’s Depart ment of Special Collections has also been consistently helpful. I am particularly grateful to them for both granting permission to print most of the images in this volume and helping to prepare these graphics for publication. Finally, as in most things, my greatest debt is to my wife, Stacie, and my children, Sam, Anna, and Michael, who after long days in the archives have offered a welcome return to the twenty-first century.

xiii

GENERAL INTRODUCTION

The period that we now label ‘Romantic’ was an age of great satire. Indeed, the late Georgian age has a valid claim to be seen as the greatest period of satire in English cultural history. An epoch which can boast the talents, amongst many others, of Jane Austen, Lord Byron, George Cruikshank, Benjamin Disraeli, Maria Edgeworth, William Hone, Thomas Hood, Theodore Hook, William Gifford, James Gillray, Thomas Moore, the circle of brilliant Tory wits around The Anti-Jacobin (George Canning, George Ellis, Gifford and John Hookham Frere) and, later, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine (James Hogg, John Gibson Lockhart, William Maginn and John Wilson), Thomas Love Peacock, Thomas Rowlandson, Thomas Spence and John Wolcot (‘Peter Pindar’) has only the early eighteenth century to rival it as an age of satire. Despite the elliptic tendency in much literary history to omit satirical poetry, if not the novel, from accounts of late eighteenth and early nineteenth century writing, the satirical urge was widespread in the Romantic period. And much of the age’s satire is compelling, a body of often brilliant, provocative and controversial poetry. Late Georgian satire has much to say about the social, political, and literary context in which it was written. Satire became a crucial site in which to debate the turbulent politics of a society in crisis in the 1790s and in the post-Napoleonic age. Ideologically partisan satire was a significant political vehicle, used to great effect from the right (in the likes of Gifford, T. J. Mathias, Blackwood’s and John Bull) and the left (in such figures as Spence, Byron, Shelley, Hone and Moore). The most significant political issues and events of the day (the French Revolution, Pittite authoritarianism, the Napoleonic wars, the Regency, the Queen Caroline crisis, the state of Ireland, agitation for Reform) resound through the satirical writing of the day. As well as being ideologically significant in terms of the geopolitics of the age, satirical writing of the period also provides illuminating social commentary on English life in the period, addressing, for instance, the position of women and the campaign for the abolition of slavery, as well as offering a fascinating insight into the manifold preoccupations of fashionable life. And satire in the Romantic period, as it had since the days of Persius and Horace, also possessed a literary-critical function: contemporary literary satires on the likes of Wordsworth and Coleridge or Keats and Hunt are important and revealing critical documents. Despite its contemporary importance, verse satire of the Romantic period, Byron apart, languished in an ill-merited neglect for most of the last century. While late Georgian graphic satire, in all its pungent brilliance, remained fixed in the critical xv

General Introduction

consciousness, its verse equivalent lingered in the shadows. Some critical attention was paid to the satirical work of canonical poets, notably Shelley, and to The AntiJacobin and the Blackwood’s circle (although the two journals often appeared cast in the role of critical anti-heroes hissing in the wings at the Lakers and the Cockney School). Romantic period satire deserved better, and in the 1990s there was a welcome revival in critical recognition and respect for the genre with the publication of several important monographs.1 That being said, textual scholarship has lagged critical attention; this is the first scholarly edition of Romantic period satire. The vast majority of the poetry included in the edition has not been edited or annotated before, and these volumes aim to let late Georgian satirical poetry speak again. For in all of its modes and tempers, this contentious, vigorous, and frequently excellent body of verse has much to offer.

I Though the fact is not evident from many twentieth-century literary histories, satire is a principal literary form of the late Georgian period. As Marilyn Butler once dryly remarked, ‘The so-called Romantics did not know at the time that they were supposed to do without satire’.2 Indeed, all of the canonical literary figures of the period, Wordsworth included, wrote satire and, in Byron, even the most restrictive canon of Romantic poetry, the so-called ‘Big Six’, includes a figure of the greatest satirical virtuosity. ‘We hate poetry that has a palpable design upon us’ wrote John Keats in 1818.3 But the poet was not always faithful to such baldly idealist principles, and though his satirical oeuvre is not large, and though his work in the genre is insignificant when compared to that of his great contemporaries Byron and Shelley, even Keats worked in the designing literary art of satire, comedy possessed of a moral purpose. The Romantic period was saturated in satire. The age saw a torrent of occasional satire: squib, pasquinade, ad hominem parody and lampoon in broadside, newspaper column and literary journal. The political, social and literary issues of the day resound though the age’s satire. And the age was listening. As Gary Dyer has written, ‘among the six canonical Romantic poets only Byron had more readers than “Peter Pindar”’.4 Despite, or probably in a certain measure because of, his Whiggism and scandalous nose-thumbing of the royal family, Wolcot enjoyed huge popular success in the Romantic period. And he was not alone; Gifford’s The Baviad went through ten new and revised editions in twenty years, Moore’s The Fudge Family in Paris was reprinted nine times within twelve months of its first appearance, and in various forms, over fifty editions of Hone and Cruikshank’s The Political House that Jack Built were published. Caricaturists, satirical pamphleteers, broadsheet balladeers and lampoonists fed the taste for satire, and anonymous satires, from the left and the right, became a staple of daily newspapers. Broadsheet, handbill and unstamped newspaper squibs brought satire to those without the means to buy a tax-paying newspaper. The likes of Thomas Moore and Leigh Hunt developed reputations as xvi

General Introduction

feared newspaper satirists, and it did not seem beneath their dignity for S. T. Coleridge, Charles Lamb, P. B. Shelley and Lord Byron to contribute satirical verse to daily and weekly newspapers. As well as quotidian occasional satire, the Romantic period saw the continuance of the eighteenth-century tradition of the book-length literary satire spanning Pope’s The Dunciad through to Churchill’s The Times, in the classical satires of the 1790s of Gifford and Mathias through to Byron’s ’prentice work in English Bards and Scotch Reviewers, or, indeed, in the mutated form of Don Juan. As well as collections of shorter satires and comic annuals containing satirical verse, hundreds of satirical books, from pamphlet-length squibs to poems as long as The Pursuits of Literature, appeared in the Romantic period. As Dyer notes, ‘About thirty satirical poems appeared in 1812 [alone], a year for which J. R. de J. Jackson’s bibliography Annals of English Verse, 1770–1835 lists only 134 volumes of original poetry’.5 Authors continued to employ the traditional models borrowed from classical satire, the Juvenalian, Horatian and, increasingly important in Romantic period prose satire, the Menippean modes, but there was also a stream of experimental work, especially in partisan satire using parodic models (as in the pamphlets of Hone and Cruikshank which develop the earlier, shorter work such as that of Spence and the ‘Signor Pistachio’ broadsides attributed to Robert Merry). Such satirists mixed their media, fusing graphic and literary satire and employing parodic models derived from popular culture rather than more elevated literary forms. That said, the ancient satirical modes did not disappear in the Romantic period. Horatian satire was by no means moribund; in the work of N. T. H. Bayly and Henry Luttrell the form had powerful advocates well into the 1820s. Indeed, in the brilliant metapoetical posturings of Wolcot in the 1790s and in the remarkable fusion of Ansteyan manner and metre with combative oppositionalism evident in the work of Thomas Moore in the Regency period and beyond, contemporary satirists took Horatian poetry in new and innovative directions during the Romantic period. The Juvenalian manner was also of great importance in the late Georgian age. Though the form best characterised the 1790s in the work of William Gifford and T. J. Mathias, there are examples of the sustained classical satire throughout the period, from William Gifford’s The Baviad (1791), printed at the period’s cusp, to Robert Montgomery’s The Age Reviewed (1827), published near its close. One of the most significant Juvenalian satirists of the first decade of the nineteenth century was the twenty-one year old Lord Byron, whose English Bards and Scotch Reviewers owes much to the ‘first satirist of the age’, William Gifford. Byron began his satirical career by copying Gifford, and ended it by imitating, and of course transcending, Gifford’s Anti-Jacobin colleague John Hookham Frere, whose use of ottava rima, colloquialism, comic feminine rhymes and improvisational manner in Whistlecraft was borrowed wholesale in Beppo and beyond. Byron engaged closely with his contemporaries, participating fully in a tradition which was still vibrant and innovative. The antediluvian critical notion that Byron’s work in satirical modes was either regressive or a conscious piece of attitudinising eccentricity is contradicted by the existence of a significant body of contemporary satirical writing. xvii

General Introduction

Satire did not die with Alexander Pope only to be resuscitated by a Byron in combative anti-Romantic mode, raking in the ashes of a dead tradition. Satire never went away, and the masterpiece of Romantic period literary satire, Don Juan, is part of a still healthy and lively satirical tradition. Like George Canning, William Gifford and Mary Robinson before him, Byron appealed to the shade of Pope in order to address the problems of the present more directly. Looking back to the eighteenth century allowed Lord Byron to talk about the nineteenth. Indeed, after the French Revolution of 1789, satire became, if anything, more important in English society than it ever had before, important in a way inconceivable to our modern world. To the Whig or radical, the codified nature of much satire allowed a measure of outspokenness in a society where free speech was severely restricted (as the trial of William Hone in 1817 demonstrated, it was notoriously difficult to prosecute for the publication of a satire). It is not insignificant that Leigh Hunt was imprisoned for seditious libel for an outspoken prose leading article on the Prince Regent rather than for publishing Charles Lamb’s ‘The Triumph of the Whale’, which makes the same points in satirical verse. And Hunt himself, on his release from prison, felt able to lampoon the Regent in a stream of verse satires published in The Examiner over the decade after his release from gaol. A measure of obliquity, however vestigal, became a useful prophylactic against imprisonment. It also facilitated the acidulous character assassination frequently employed in literary and graphic satire of the period. Indeed, satire is one of the few cultural forms that can seem less unbuttoned two hundred years ago than it does today. Few modern satirists mindful of laws concerning personal libel would, like the then Whig satirist George Ellis in the Probationary Odes for the Laureateship (1785), allege that the Prime Minister (William Pitt) was an alcoholic homosexual whose sexual partner was a member of his cabinet, himself a future Prime Minister (Lord Liverpool). Satire became a principal vehicle for Whig and radical oppositionalists alike in the Romantic period, whether in traditional verse satire (in the Whig satirists Moore and Byron or in the radicalism of Hunt and Shelley), or in mixed-media form (from the broadsides of Thomas Spence in the 1790s to the work of Hone and Cruikshank in the 1810s). Satire and opposition went hand-in-hand in the Romantic period. However, if satire was an important plank in Whig and radical rhetoric, it was no less important to the forces of reaction. Satire is a promiscuous muse and overarching critical debate as to whether or not satire is innately ‘conservative’ or ‘radical’ during the period is best avoided. Satire consorted with the Tory establishment during the Romantic age, and often in brilliant and compelling ways; it is notable that an important part of the Tory government’s attack upon what it saw as an overly liberal press consensus during the 1790s was to fund and sponsor the brilliant satirists of The Anti-Jacobin,6 three of whom were Tory parliamentarians. Indeed, William Pitt is said to have contributed to the newspaper’s satirical manifesto, ‘New Morality’. The Quarterly Review, the voice of early nineteenth-century Toryism was edited by that iconic figure of Romantic period literary satire, William Gifford, and the most brilliant satirical journal of the period, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine espoused an iconoclastic brand of mordantly effective satire and ultra-Toryism. xviii

General Introduction

George Ellis after his conversion from Whiggism, Viscount Palmerston before his conversion to Whiggism, Benjamin Disraeli, John Hookham Frere: satire and Tory parliamentary politics are intimately entwined in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. The Romantic age remains the only period within literary history to have a satirist of genius – George Canning – as one of its Prime Ministers. Satire and conservatism went hand-in-hand in the Romantic period. Satire of the Romantic period is also an important literary-critical discourse. From satirico-didactic survey poems in the manner of The Dunciad (English Bards and Scotch Reviewers, The Age Reviewed and so on), to sustained satirical campaigns against unwanted poetical innovation (Gifford on the Della Cruscans, The Anti-Jacobin on the ‘New School’ of Southey and Coleridge, Byron’s ambivalent relationship with Wordsworth), to lampoons which settle old scores in ad hominen personal satire (Gifford on Wolcot, Wolcot on Gifford, Hunt on Gifford, Moore on Hunt, just about everyone on Southey), satire was a forum for passionate debate as to the literary spirit of the age, and contemporary satires on the ‘Lake School’ or the ‘Cockney School’ (themselves near-satirical labels) are important critical documents. The literary criticism of the day is closely mirrored in satire: Byron’s review of the Poems in Two Volumes as ‘not simple but puerile’ is complemented by English Bards and Scotch Reviewers’ attack on Wordsworth’s dullness. Often literary criticism and satire and parody form a kind of hermeneutical pincer movement. Indeed, on many occasions satire leads literary critical debate, as per The Baviad’s assault on the Della Cruscans or The Vision of Judgment’s attack on the hapless Southey’s laureate poem. From The Baviad onwards, each new literary movement within the Romantic period was greeted by vigorous satirical nosethumbing. Often satire, to use Byron’s phrase, saw itself as a ‘county physician’ purging the body of contemporary literature. As Steven E. Jones has written, the ‘satiric violence’ so often manifest in Romantic period writings ‘reflects an emerging consensus that the poetry they attacked – sentimental, Della Cruscan, Cockney, Lake School, Satanic school – was part of a dangerous new epidemic, but one that might still respond to the harsh treatment of satire’.7 Certainly satire was quick to identify the spirit of the age, and to a degree might be said to have contributed to the formation of the Romantic canon. Significantly, the first identification of a nascent ‘NEW SCHOOL’, with its political liberalism, self-conscious provincialism, sympathy for the poor and dispossessed and fondness for innovation is The Anti-Jacobin’s in November 1797. And satire shaped Wordsworth’s reputation, from the supposed idiotic driveller who appears in satire on the Poems in Two Volumes to the arcane prosing metaphysician evident in that which appears after the publication of The Excursion. All this is not to say that satire is only reactive, or lacking in imaginative power; few writings in the Romantic period match the ingenuity, innovativeness and energy of Byron, Canning, Hone or Moore at their best. Not all satire in the period addresses itself to the literary spirit of the age or profound issues of state. Satire is also a mode of social commentary, providing a real insight into English society in the late Georgian period. Romantic period satire offers us intimate access into the epiphenomena of fashionable life: men and women’s fashions, dining, shopping, drinking, gambling, blackmail, trends in the xix

General Introduction

theatre and music and so on. The dress code at Almack’s, the vogue for hot air ballooning, the ingenious advertising methods of quack doctors; the social minutiae of the age resounds through its satirical writing. Historians and literary critics have consistently engaged with such works of graphic satire as Cruikshank’s ‘Fashionables of 1817’, but caricature’s literary equivalents, Bayly’s Epistles from Bath or Luttrell’s Letters to Julia, and many of the squibs gathered in the first volume of this edition, are ignored. In both its graphic and its literary forms, satire is an invaluable vade mecum to the social ephemera of the age, and it is high time that verse satire on fashionable life was given its due importance. Late Georgian satirical writing also frequently addresses such important humanitarian and social issues as the campaign for the abolition of slavery and the position of women. A significant strand within abolitionist rhetoric in the late eighteenth century is poetical, whether satirical or non-satirical, and the edition includes examples of anti-slavery verse by William Cowper and Edward Jerningham. Satire on the blue-stockings, in the manner of Pope, continued apace, sometimes wry and affectionate Leigh Hunt’s Blue-Stocking Revels (1837)), sometimes vitriolic (The Baviad). And the emergence of the radical female jacobin provoked a good deal of rancorous Tory satire in the manner of Richard Polwhele’s The Unsex’d Females. A Poem (1797), much of which fastened delightedly on William Godwin’s unfortunately over-candid memoir of his late wife. Satire became a significant place in which to debate women’s rights and duties, amongst women as well as amongst male authors. As the first volume of this edition demonstrates there is a significant body of satirical poetry written by women in the period on the issue of how women and girls should behave, a kind of satirical conduct literature. This is not to say that female authors confined their satire to the purely domestic scene (and even here parallels are often made between domestic life and wider society). Satirists such as Mary Robinson, Lady Anne Hamilton and Anna Letitia Barbauld dealt with the same large political and social themes which their male counterparts addressed: European politics, high society, and the failings of the House of Hanover.

II British Satire 1785–1840 republishes a wealth of rare and often hitherto unedited satirical material and provides, for the first time, the necessary annotation and explanatory material necessary to a full appreciation of the complexities of Romantic period literary satire. The edition offers a representative collection of verse satire from the mid-1780s to the mid-1830s, offering a balance between literary and social satire, between radical and conservative political satire, between the Juvenalian and the Horatian manner and between classical satire and other formal modes. Despite the fact that the Romantic period saw an abundance of satirical poetry and the contemporary importance of that body of work, there has never been an anthology of Romantic period verse satire and this is the first collection in the field. xx

General Introduction

The edition is in five volumes: three volumes of Collected Satires and two single author editions devoted to the two figures who, after Byron, best represent Romantic period verse satire: William Gifford and Thomas Moore.8 Volume 1, Collected Satires I: Shorter Satires, edited by Nicholas Mason, anthologises a wide range of satirical poems, essays, squibs, and prints from the Romantic age. As such, it offers a survey of late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century satirical traditions previously unavailable to students of the period. Perhaps the volume’s greatest strength lies in the diversity of its selections, as it demonstrates how satire was creatively and effectively employed by male and female, rich and poor, conservative and radical alike. The volume also illustrates how satirical trends like the mock broadside, the punladen spoof, and the Juvenalian jeremiad evolved between 1785 and 1840. In selecting authors, Mason has included several ‘major’ Romantic poets along with political firebrands, famed comedians, and, perhaps most significantly, a wide variety of satirically-minded women. The impressive collection of texts from this latter group should once and for all debunk the old myth that the realm of the satirist was no place for proper ladies. Volume 2, Collected Satires II: Extracts from Longer Satires, edited by David Walker, draws upon a neglected but rewarding body of Romantic period comic writing, the book-length satires discussed above. The Romantic period saw a plethora of sustained, book-length satires and this volume offers representative extracts from these writings. It features literary satire, including, for instance, Mant’s assault on the Lake Poets, The Simpliciad, Polwhele’s onslaught on female intellectuals, The Unsex’d Females, Combe’s satire on the vogue for the picturesque, The Three Tours of Doctor Syntax, the Morgans’ attack on Blackwood’s, The Mohawks, and Peacock’s lampooning of Byron and Coleridge, Sir Proteus. It also addresses political satire (Ellis’s second attack on Pitt in the Criticisms on the Rolliad, Shelley’s on the Regent in Oedipus Tyran nus, Barrett’s on the short-lived coalition which followed the death of Pitt, All the Talents) and social satire (Luttrell’s Horatian satire on fashionable life, Letters to Julia, and Montgomery’s vituperative Juvenalian assault upon it, The Age Reviewed). Volume 3, Collected Satires III: Complete Longer Satires, edited by Benjamin Colbert, contains complete facsimiles of five satires written between 1785 and 1822, selected to illustrate both the major genres of satiric production in the period and the interplay between them. Redressing the tendency among modern readers to downplay the comic genius of John Wolcot (‘Peter Pindar, Esq.’), the volume opens with the first scholarly edition of The Lousiad: an Heroi-Comic Poem (5 Cantos, 1785–95), the cornerstone of Wolcot’s phenomenal success. Like many of his best satires, The Lou siad turns its razors against George III, who appears as a bumbling belligerent, outraged at the discovery of a louse on his dinner plate. The King orders that his cooks submit to having their heads shaved. They resist, and the scene is set for epic conflict between crown and kitchen. The facsimile reproduces the poem’s first collected edition (1794–96), revealing a complex Wolcot who seriously flirted with ultra-radical politics despite the great personal danger of doing so in a climate of reactionary legislation. Wolcot’s 1796 revisions to Canto 5 introduce outspoken Jacobinical passages that helped to dictate the terms by which ‘Peter Pindar’ was xxi

General Introduction

appreciated or vilified thereafter, not least by William Gifford, Wolcot’s most trenchant ideological rival in the 1790s. Widely recognised and lionised as the chief opposition satirist of his age, Wolcot enjoyed the friendship of William Godwin and Mary Robinson, and the admiration of Leigh Hunt and Shelley, as well as a rising generation of radical satirists who borrowed his nom de plume to fight new battles. With the notable exception of William Hone and George Cruikshank’s The Queen’s Matrimonial Ladder (1820), none of the other satires in Volume 3 enjoyed the success of The Lousiad. Yet they do offer an intriguing overview of the styles and subjects of satire during the glory years of ‘second generation’ Romanticism, 1817– 22. Nathaniel Thomas Haynes Bayly’s Epistles from Bath; or Q’s Letters to His Yorkshire Relations (1817) is a Neo-Horatian satire on Bath society and fashion, one of the best examples of a sub-genre derived from Christopher Anstey’s perennially popular New Bath Guide (1766) – and a useful companion to Jane Austen’s satiric Bath novel, Northanger Abbey, published the same year. Hone’s and Cruikshank’s The Queen’s Mat rimonial Ladder, A National Toy, with Fourteen Step Scenes; and Illustrations in Verse, with Eighteen Other Cuts (1820), on the other hand, is a mould-breaking, radical satire on George IV’s divorce proceedings against Queen Caroline, the one public event that galvanised the reform movement in the aftermath of Peterloo. Basing their design on a children’s toy, Hone and Cruikshank produced a multi-media pamphlet that belittled the new King with coarse graphics, jeering verses, and their own ‘National Toy’, a pasteboard ladder depicting George’s Hogarthian ‘progress’ of infamy. Volume 3 also includes two rare satires that, in different ways, take on the populist tendencies of literary culture: James Harley’s Neo-Juvenalian conversation satire, The Press, or Literary Chit-Chat (1822), with its synopsis of recent publications, authors, and controversies, and the Menippean interlude, The Illiberal! Verse and Prose from the North!! (1822), at once a parody and satire on Byron, Shelley, and Leigh Hunt’s infamous but short-lived journal, The Liberal, or Verse and Prose from the South (1822–23). Both works are inflected by a high-Tory obsession with the pernicious influence of Cockney rhymesters on the precincts of high culture, ambivalently represented by that most enigmatic Romantic persona, Lord Byron. Volume 4, Gifford and the Della Cruscans, edited by John Strachan, combines William Gifford’s twin satires, The Baviad (1791) and The Mæviad (1795), acerbic but compelling assaults upon the Della Cruscan school of poetry, with an anthology of Della Cruscan poetry. Gifford, born into poverty and former apprentice cobbler, was enabled by patrons to proceed to Oxford, eventually becoming an important satirist and journalist (he was editor of two of the most important periodicals of the Romantic period, The Anti-Jacobin, or Weekly Examiner and The Quarterly Review). Gifford was known in his day as the foremost classical satirist, a consensus exemplified in Byron’s eulogistic references in English Bards and Scotch Reviewers, tributes made all the more impressive inasmuch as they come from a liberal Whig to an unflinching ultra-Tory. Modern readers have been less forgiving of Gifford’s combative antijacobinism and of the bludgeoning meted out to his satirical victims (as if ad hominem character assassination is acceptable when it proceeds from the pen of a Hazlitt or a Hunt, both of whom were expert exponents of the literary scalpel, but beyond the xxii

General Introduction

pale when it is from a Gifford or a Wilson). But we should not let ourselves be blinded to the power of Gifford’s performance. With the publication of The Baviad and The Mæviad Gifford became the iconic figure of Tory satire in the Romantic period, and, with his editorship of The Quarterly, the iconic figure of early nineteenthcentury literary Toryism as a whole. However, despite its political and literary significance, there is no modern edition of Gifford’s poetry, and this is the very first scholarly edition of Gifford’s troubling, mordant masterpieces. One problem which faces the modern reader of Gifford is the fact that there is no contemporary edition of his satirical targets, and Volume 4 also includes the first anthology of the Della Cruscan school, that remarkable cultural phenomenon that enraptured fashionable English life in the late 1780s and early 1790s. The Della Cruscan coterie, the most important of whom were Hannah Cowley (‘Anna Matilda’), Robert Merry (‘Della Crusca’) and Mary Robinson (‘Laura Maria’), with their poetry of highly-wrought and self-consciously artificial sentiment, was an important staging-post in the development of English Romanticism and Romantic period women’s writing, and here a representative selection from the poetry of what might be called their house journals, The World and The Oracle, is given alongside Gifford’s critique of their work. Gifford was not, as critical commonplace has had it, taking a sledgehammer to a nut; his assault is upon a significant avant-gardist literary movement. Gifford recognised the importance of the Della Cruscan project, and the very venom with which he treats it betokens that importance. The volume also includes Gifford’s ad hominem attack on John Wolcot, the Epistle to Peter Pindar (1800), a document unparalleled in the period for satirical ferocity (with the possible exception of Wolcot’s cloacal reply, Out at Last! (1801)). Additionally, it incorporates several important satirical responses to Gifford: Wolcot’s Out at Last!, but also Mary Robinson’s Modern Manners (1793) and Edward Jerningham’s ‘Lines on “The Baviad” and “The Pursuits of Literature”’ (1797; 1806). Finally, Volume 4 also features important contextual documents in its two appendices: the proceedings of the unsuccessful libel case brought against The Baviad by one of its principal victims, John Williams (‘Anthony Pasquin’), the ‘Proceedings of the Trial of Robert Faulder, Bookseller … for publishing a libel on John Williams alias Anthony Pasquin’ (1800) and, one ‘good hater’ savaging another, William Hazlitt’s compelling invective A Letter to Wil liam Gifford, Esq., from William Hazlitt, Esq. (1819). Volume 5, The Satires of Thomas Moore, edited by Jane Moore, collects the verse satires of Ireland’s most popular national poet. Although Moore is primarily remembered today as the poet of the Irish Melodies, and, perhaps, as the author of the National Airs or the biographer of Byron, he was celebrated during his own lifetime as an outstanding Whig satirist. His contemporaries knew him as much for his political satires and newspaper squibs as for his songs, and from 1812 he became the unofficial laureate of the Whig opposition. Moore discovered his mature satirical voice in the humorous but ideologically combative squibs which he began publishing in The Morning Chronicle in 1812 as a direct consequence of the decision by the Prince of Wales, upon assuming his full powers as Regent, to retain the Tory government. The squibs Moore wrote for the Chronicle and, later, for a while, The Times, xxiii

General Introduction

kept his name at the centre of public debate and won him the admiration of his great contemporaries, Byron, Hazlitt, Hunt, and Shelley, who applauded his light, rapid humour and lilting anapaests, a combination that was as important to Moore’s development as the discovery of ottava rima and the improvisational manner was for his fellow Whig poet Lord Byron. Moore was also the author of several significant book-length satires, attaining national and international recognition with such works as Intercepted Letters; or, the Twopenny Post-Bag and The Fudge Family in Paris, which fuse Horatian epistolary social satire with combative liberal politics. Moore’s verse satires fall into three categories: the Juvenalian satires in heroic couplets of his mid-twenties, written between the years 1804 and 1812; the Horatian satires of his maturity, written in the looser anapaestic measure; and the short topical verses mentioned above. Volume 5 gives all the major satires in full, from the early anti-American satires collected in Epistles, Odes, and Other Poems (1806) to the classical satires Corruption and Intolerance (1808) and The Sceptic (1809) to the later Horatian satires: Intercepted Letters; or, the Twopenny Post-Bag (1813), The Fudge Family in Paris (1818), Tom Crib’s Memorial to Congress (1819; reprinted here in full for the first time), Fables for the Holy Alliance (1823) and The Fudges in England (1835). A full and representative selection of the occasional satire from the newspapers and periodicals is also included. The vast majority of the poetry in this edition has never been edited or annotated before, a consequence of the neglect of the period’s satirical heritage evident until the 1990s. Indeed, even where there are twentieth century editions of the writings collected in this set, as in the case of the 1910 Oxford edition of Moore edited by A. D. Godley, the reader is left to deal with poetry which is highly contextually allusive without the aid of headnotes or explanatory editorial annotation. Appreciation of Moore, as of much Romantic period literary satire, has been hampered by his densely allusive literary manner. Whilst some of the most memorable and engaging satirical works of the period require little editorial explanation, much satire is so intricately rooted in its own time that reading it without assistance is like reading Pope’s The Dunciad without annotation. Consequently, this edition provides detailed annotation and individual headnotes to each satire. These are especially necessary, given that this body of work, subtly intimate as it is with contemporary political and literary intrigues, is frequently reliant upon a knowledge of particular circumstances and contexts (literary, political and social) which often need to be restored for the modern reader. Reading the ad hominem, opportunistic or politically engaged satire of the period without annotation can be a frustrating experience and this edition provides the reader with the contextual knowledge needed to remove that frustration. It restores the resonances and subtleties of Romantic period satire, letting it speak clearly once again. John Strachan

xxiv

General Introduction 1 Marcus Wood’s Radical Satire and Print Culture 1790–1822, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1994, Gary Dyer’s British Satire and the Politics of Style, 1789–1832, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1997, Steven E. Jones Shelley’s Satire: Violence, Exhortation and Authority, De Kalb, Northern Illinois University Press, 1997 and the same author’s Satire and Romanticism, New York, St Martin’s Press, 2000. 2 Marilyn Butler, ‘Satire and the Images of the Self in the Romantic Period’, in English Satire and the Satiric Tradition, ed. Claude Rawson, Oxford, Basil Blackwell, 1984, p. 209. 3 Keats to J. H. Reynolds, 3 February 1818. 4 Dyer, British Satire and the Politics of Style, p. 12. 5 Ibid., p. 12. 6 For The Anti-Jacobin, see volume 1, The Anti-Jacobin, of Parodies of the Romantic Age, ed. Graeme Stones and John Strachan, 5 vols, London, Pickering & Chatto, 1999. 7 Jones, Satire and Romanticism, pp. 7-8. 8 The two volumes complement each other well. They illustrate the political range: Gifford positioned on the right, Moore on the left. The satirists are active in the two periods of great satirical productivity: Gifford in the 1790s, Moore in the post-Napoleonic period. Their manners are also diverse (Gifford invariably Juvenalian; Moore predominantly Horatian) as are their metres (Gifford using the Popean couplet of English classical satire; Moore moving from heroics to his later iambic and anapaestic tetrameters).

xxv

EDITORIAL PRINCIPLES

This edition reprints satirical writings published between 1785 and 1840. Unless otherwise stated, the copy text is the first published version of each item. Authorial notes appear as footnotes on the bottom of the page; editorial notes appear as explanatory notes at the back of each volume. In the text itself, the following aspects have been retained: the use of large and small capitals; the use of italics; spelling, including archaic spellings. The texts have been altered in a number of ways to conform to the Pickering & Chatto house style: initial double quotation marks have been changed to single inverteds; quotation marks have been removed from around indented quotations; footnotes have been standardised to a system of asterisks, daggers and so on; the use of full stops after abbreviations has been dropped when the abbreviation ends with the final letter of the original word (‘St’ for ‘St.’ and ‘Dr’ for ‘Dr.’). Obvious errors in spelling, punctuation and typography have been silently corrected. Each work is furnished with an explanatory headnote and comprehensive annotation in the form of endnotes. Headnotes give details of first publication and contextualize each item. Explanatory endnotes provide information about proper names, quotations, obscure words, and foreign phrases (with the exception of those in French). The abbreviation DNB in an endnote indicates that an article on the person concerned will be found in the Dictionary of National Biography. Cross-references within a volume, and to other volumes in this edition, are given as upper-case (‘Vol.’) with Arabic numerals (‘1’) through (‘5’). References to all other editions are given as lower-case ‘vol.’. John Strachan

xxvii

INTRODUCTION

As the first collection of its kind, this anthology aims to reflect the richness and diversity of British satire from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. While it is impossible to represent the entire scope of satirical writing from an era in a single volume, I have tried to select texts that touch on a wide range of issues and speak from a variety of perspectives. Thus, in the pages below, we hear from Paineites and Burkeans, feminists and misogynists, evangelicals and sinners. In tone, the texts range from ecumenical to chauvinist, wistful to blustering, Horatian to Juvenalian. And chronologically, the volume moves from the French Revolution and the rise of Pittite conservatism, through the Napoleonic wars and the Regency period, and into the Reform agitation of the 1820s and 1830s. In selecting texts, I have tried to mix traditional canonical voices with those of lesser-known writers. This is the rare anthology where inclusion of all six ‘major’ Romantic poets might actually seem ground-breaking, since satire has traditionally been held as anathema to High Romanticism.1 Most readers will probably have little difficulty envisioning Blake, Byron, and, perhaps, Shelley in such a volume; but, on the surface, the other three poets don’t seem to fit. I have, therefore, purposely included satirical poems by Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Keats to challenge this perception and, above all, to bolster the argument, made most recently by Steven Jones,2 that satire is not nearly as incompatible with Lake School or Keatsian Romanticism as we have generally assumed. Another conscious choice I have made in compiling this edition has been to represent women authors more fully than they generally have been in previous collections of comic or parodic literature.3 While lamentable, the scarcity of women writers in earlier anthologies is in ways understandable, since historically satire, parody, and comedy have been viewed as predominantly male pursuits. It would be difficult to quantify exactly how often women writers employed satire in their work and whether they indeed turned to satire considerably less frequently than their male counterparts. The works of Jane Austen, Maria Edgeworth, and several other novelists of the period certainly prove that women could excel as satirists. But, as Gary Dyer’s extensive bibliography of Romantic-era satire suggests, women writers generally seem to have shied away from the types of political and personal raillery that characterized the writing of popular male satirists like ‘Peter Pindar’, Lord xxix

British Satire 1785–1840, Volume 1

Byron, and Thomas Moore.4 This is particularly true with poetry, a mode in which society expected women to model sensibility, domesticity, and morality, not resentment and spleen. It would be a mistake, however, to assume that women’s verse of the Romantic era was altogether satire-free. As this anthology tries to establish, a number of women poets turned a critical eye on the world about them, using satire as a tool to expose society’s flaws. Many of these women, such as Helen Leigh, Carolina Oliphant, and Anna Dodsworth, wrote primarily for their families, taking as their subjects local events or private jokes within their social set. Others, such as Jane Taylor and Maria Abdy, aspired to reach a larger audience, satirizing courtship rituals, gossip, balls, and other common aspects of middle- and upper-class women’s experience. In rare instances, some women were even emboldened to write satire on the institutions of church or state, as is the case in two of the poems below: Mary Robinson’s ‘The Confessor’, a pointed critique of clerical misconduct, and Anna Laetitia Barbauld’s Eighteen Hundred and Eleven, an elegy forecasting the seemingly imminent demise of the British Empire. Along with beginning to map out a tradition of women’s satire, another major aim of this anthology is to recover now-obscure texts that in their day had a major impact on public opinion and political policy. Many of the satirists anthologised below ranked among the age’s most widely read authors. John Wolcot (pseud. ‘Peter Pindar’), for instance, was immensely popular in the final decades of the eighteenth century and was largely responsible for fixing in the public’s mind the image of George III as a blundering and absent-minded but strangely endearing fool. Following Wolcot’s lead, several other late-eighteenth-century satirists took aim at political figures, with the seemingly scandal-proof prime minister, William Pitt the Younger, serving as a favourite target. Selections in this volume that lampoon Pitt and his repressive policies include Daniel Isaac Eaton’s pamphlet The Pernicious Effects of the Art of Printing Upon Society, Revealed, Coleridge’s eclogue ‘Fire, Famine, and Slaughter’, and the anonymous ‘Signor Gulielmo Pittachio’ broadsides.5 That radical satirical texts such as these proliferated in the 1790s and again in the late 1810s says much about both the nature of satire and the political climate of these years. In periods of heightened official paranoia and repression, when opponents of the government regularly found themselves in prison, at the gallows, or aboard a ship bound for Australia, satire proved an ideal medium for taking swipes at the nation’s leaders with relative impunity. A favourite ploy, for instance, in radical journals of the 1790s like Thomas Spence’s Pigs’ Meat and Eaton’s Politics for the People was the Swiftian tactic of ironically adopting the voice of a staunch loyalist to expose just how narrow-minded and reactionary the policies of the current administration had become. This type of satire would remain popular into the new century, as evidenced in such texts as Charles Lamb’s ‘Triumph of the Whale’, a mock panegyric on the profligate and obese ‘Prince of Whales’, and the Black Dwarf ’s ‘The “Undebauched Royalists”’, a one-act play where the instigators of the Peterloo massacre unwittingly condemn themselves through their own words. From time to time, the xxx

Introduction

government would prosecute the authors or publishers of such satires, as was the case when the crown arrested Eaton for circulating John Thelwall’s ‘King Chaunticlere’ fable. But, as a general rule, the satirist enjoyed much greater immunity from treason charges than the straightforward polemicist. Tellingly, when Leigh Hunt was convicted of sedition in 1812, it was not for his role in publishing satires like ‘Triumph of the Whale’, but for his direct and open editorial assaults on the Prince Regent’s morals. While in recent decades radical satire has attracted considerable scholarly attention,6 relatively little notice has been paid to conservative contributions to the genre. Whether accurate or not, there seems to be a sense that, with a few noteworthy exceptions, the Tory satire of this era lacked both the creativity and popular appeal of the radical tradition and is, therefore, less interesting two centuries later. It is important, however, not to lose sight of how extensively satire was used by all political factions. Thus, I have tried to include texts that represent the types of satirical arguments political moderates and conservatives were wont to make. In the ‘Song, by Mr. Paine’, for instance, we get a glimpse of the deep suspicion even a moderate like Wolcot felt toward Paine and his fellow republicans. In the Anti-Gallican’s ‘Invasion of England’ broadside, we witness the John Bull tradition in its purest form, contrasting British manliness with French foppery and taunting the puny Napoleon to dare set foot on British soil. And in the selections from Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine (‘The Magic Lay of the One-Horse Chay’ and ‘A New Song, to be Sung by All Loyal and True Subjects’), we see Tory writers impressively employing the tools of satire to promote the ideals of Burkean conservatism. Given the preponderance of powerful political satire from this era, it would have been easy to fill this entire volume with such texts. I have tried, however, to adequately represent other branches of the age’s satire, such as the social, literary, and religious, as well. As the selections that follow will reveal, few subjects or areas of society were off-limits to the satirist. An especially popular target was the hypocrisy of institutions or individuals, particularly the church and its ministers. That the keepers of Christ’s flock are failing to live up to their charge is a favourite theme throughout this volume, receiving its most extensive treatment in Burns’s ‘The Holy Fair’, Robinson’s ‘The Confessor’, and Reynolds’s ‘Address to the Dean and Chapter of Westminster’. Literary figures also receive their comeuppance at several points below. Wordsworth is cast as a mirror image of the provincial poetaster ‘Dr Marshall’ in the anonymous ‘Discovery of Another Poet’; the German nationalist poet Klopstock is the subject of a scatological hex in Blake’s ‘When Klopstock England Defied’; and virtually every prominent figure in literary London is reduced to size in Hood’s ‘Ode to Mr. Graham, the Aeronaut’. A few final explanations for what follows. As will become readily apparent upon scanning this volume, most of its texts are in verse. The simplest explanation for this is that, by definition, this volume’s aim is to sample from the age’s ‘shorter’ satires. Obviously, then, all of the prose satire found in Romantic-era novels and much of that in the era’s magazines and literary reviews falls outside the length limitations xxxi

British Satire 1785–1840, Volume 1

of this particular volume. Another reason for verse’s predominance here is that it remained the primary vehicle for satire well into the early 1830s, a fact that is born out in Dyer’s bibliography. That said, I have tried to balance the verse selections below with memorable examples of Romantic-era prose satire. The prose texts in this volume range from the mock polemic (Eaton’s The Pernicious Effects), to the mock broadside (the ‘Pittachio’ and ‘Invasion of England’ squibs), to the comic dictionary (Smith’s ‘Specimens of a Patent Pocket Dictionary’). Other noteworthy examples include Thelwall’s beast fable, ‘King Chaunticlere’; Hone’s spoof on the Queen Caroline trial, ‘Non Mi Ricordo!’; and the mock review ‘Discovery of Another Poet’ from the Globe and Traveller. I have also included several cartoons and caricatures in an attempt to emphasize the close relationship between the graphic and print satire of this era. Not only did cartoonists and literary satirists tend to share the same general subjects, but they also worked in unison quite regularly. Among the more fruitful collaborations showcased in this volume are those between James Gillray and George Canning (the ‘Doctor Addington’ satires) and William Hone and George Cruikshank (Non Mi Ricordo! and ‘The Doctor’ from Man in the Moon). These are powerful instances of cross-textuality, as in all these cases neither the written nor the visual satire is nearly as effective without its companion piece. Finally, in keeping with the general editorial guidelines for this series, I have used the first published edition as the copy-text for almost every entry. In those few instances when the text in this volume differs from the first published edition, I have tried to make clear my rationale for doing so. Except where noted, all formatting, spelling, and punctuation are reproduced exactly from the original text, with only the long ‘s’ and quotation marks having been modernized. Nicholas Mason

1 In a frequently cited passage from Natural Supernaturalism, for instance, M. H. Abrams hesitates to group Byron among the major Romantics ‘because in his greatest work he speaks with an ironic counter-voice and deliberately opens a satirical perspective on the vatic stance of his Romantic contemporaries’ (Natural Supernaturalism: Tradition and Revolution in Romantic Literature, New York and London, Norton, 1971, p. 13). 2 Steven E. Jones, Satire and Romanticism, New York, St Martin’s, 2000, pp. 1–4. 3 One need only skim modern anthologies of comic, satire, and parodic verse to sense how commonly women writers have been excluded from these categories. Of the thirty-six signed entries in Kent and Ewen’s Romantic Parodies, 1797–1831, London and Toronto, Associated University Press, 1992, only two are by women. This exact same two-out-ofthirty-six ratio is found in the non-anonymous entries between Samuel Johnson and Robert Browning in The Oxford Book of Comic Verse, ed. John J. Gross, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1994. Even more relevantly, The Oxford Book of Satiric Verse, ed. Geoffrey Grigson, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1980, includes twenty-five non-anonymous authors between Johnson and Dickens, none of whom are women. xxxii

Introduction 4 Dyer’s forty-page bibliography of Romantic-era satire is included at the end of British Satire and the Politics of Style, 1789–1832, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1997. For Dyer’s reflections on women’s exclusion from the tradition of formal verse satire, see pp. 7, 54, 150–51. 5 For a history of the production and reception of radical broadsides during the 1790s, see John Barrell’s introduction in Exhibition Extraordinary!! Radical Broadsides of the Mid 1790s, Nottingham, Trent, 2001. 6 See Dyer, British Satire and the Politics of Style; Marcus Wood, Radical Satire and Print Culture 1790–1822, Oxford, Clarendon, 1994; and Michael Scrivener, Poetry and Reform: Periodical Verse from the English Democratic Press 1792–1824, Detroit, Wayne State University Press, 1992.

xxxiii

ROBERT BURNS

‘The Holy Fair’ (1786) [First published in Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, Kilmarnock, John Wilson, 1786, pp. 40–54. Since its initial publication in the 1786 Kilmarnock edition of Robert Burns’s (1759–96; DNB) poetry, ‘The Holy Fair’ has remained one of the poet’s most popular works with critics and general readers alike. According to a manuscript note, the poem was composed in 1785, and most Burns scholars agree that he probably wrote it sometime following the Mauchline communion held in August of that year.1 That the poem made it into the Kilmarnock edition is noteworthy primarily because of the number of early Burns satires that were consciously omitted from this collection. Whereas poems like ‘The Holy Tulzie’, ‘Address to Beelzebub’, and ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’ were presumably excluded because of the personal and potentially offensive nature of their satire, Burns and his publisher seem to have felt ‘The Holy Fair’ was amiable enough to be published without risking widespread reprisals from its satirical targets. In many respects, ‘The Holy Fair’ is heavily indebted to centuries-old traditions of Scottish poetry. Its portrayal of the revelry and ritual of a popular celebration, for instance, hearkens back to sixteenth- and seventeenth-century festival poems such as ‘Peblis at the Play’ and ‘Chrystis Kirk on the Grene’. Even more directly, the poem builds upon Robert Fergusson’s ‘Leith Races’, a 1773 poetic portrait of holiday festivities in the country outside Edinburgh. A glimpse at the opening stanza of ‘Leith Races’ suggests how extensively Burns borrowed, both formally and thematically, from Fergusson’s poem: In July month, ae bonny morn, Whan Nature’s rokelay green Was spread o’er ilka rigg o’ corn To charm our roving een; Glouring about I saw a quean, The fairest ’neath the lift; Her een were o’ the siller sheen, Her skin like snawy drift, Sae white that day. 1

DOI: 10.4324/9780429348143-1

British Satire 1785–1840, Volume 1

Burns also took from ‘Leith Races’ his allegorical plot device, adapting Fergusson’s encounter with ‘Mirth’ into his own adventures with ‘Fun’, ‘Hypocrisy’, and ‘Superstition’. It would be a mistake, though, to see ‘The Holy Fair’ as little more than a skilful imitation or reworking of its poetic models. In many respects, the poem is the classic Burnsian satire, painting vivid pictures of communal life in late eighteenthcentury Ayrshire. Setting the poem at the annual Mauchline communion allows Burns to survey the heterogeneity of local culture, as gathered together on one plot is an eclectic mix of Calvinist firebrands, moderate moralists, well-to-do farmers, and village ‘swankies’ and ‘jades’. Ostensibly, the thousands who throng to Mauchline do so to receive the sacrament and hear the word of God. Burns, however, is more interested in divisions among the assembled than any unity of purpose. At the most basic level, the poem divides the godly from the carnal, cleverly employing zeugmas (‘Here, some are thinkan on their sins, / An’ some upo’ their claes’) and cutting back and forth between the pulpit and the ale-house to emphasize the diversity of the congregation. Burns is also interested in the fissures within these respective groups, devoting large sections of the poem to the tensions between conservative, ‘Auld Licht’ Calvinists and their moderate, ‘New Licht’ colleagues. Although ministers on both sides of this divide are open to his mockery, Burns clearly sympathizes with those who offer a gospel of love rather than damnation. By the late eighteenth century, ‘Auld Licht’ ministers had become a minority in the Scottish kirk, yet in Mauchline they maintained a powerful grip on the church and the community. As something of a free-thinker and a notorious fornicator, Burns regularly found himself at odds with the local church elders, on more than one occasion being subjected to public humiliation and punishment for his dalliances with village lasses. In some respects, then, ‘The Holy Fair’, like ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’ and other poems from this period, is Burns’s revenge upon those who, in his assessment, showed greater devotion to the gospel of Calvin than that of Christ.2 Equally important in the poem, however, is its exploration of the basic internal struggles between soul and body, principle and hypocrisy, trained behaviour and natural instinct. In the process of exploring these tensions, Burns turns traditional religious poetry on its head. As David Daiches has pointed out, ‘Instead of starting from the natural and physical and moving up to the ecstatic and divine, Burns starts from the coldly theological and moves rapidly down to the physical and the earthy’.3 The result is a text that, like its author, longs for the religious ideal but in the end seems powerless before the inescapable charms of brandy and ‘Houghmagandie’.]

1 For a general textual history of ‘The Holy Fair’, see James Kinsley’s commentary in The Poems and Songs of Robert Burns, 3 vols, Oxford, Clarendon, 1968, vol. 3, pp. 1093–96. Kinsley’s excellent edition has served as a highly useful resource while preparing my own 2

Burns (‘The Holy Fair’) annotations of Burns’s text. For the sake of the reader’s patience, I have included glosses on Burns’s Scots as marginals on the page of the text rather than in endnotes. 2 Alan Bold’s A Burns Companion, New York, St Martin’s, 1991, contains an informative overview of Burns’s religious background and attitudes, including his quarrels with the ‘Auld Licht’ elders of Mauchline. See pp. 89–99. 3 David Daiches, Robert Burns, New York, Macmillan, 1966, p. 123.

3

A robe of seeming truth and trust Hid crafty observation; And secret hung, with poison’d crust, The dirk of Defamation: A mask that like the gorget show’d, Dye-varying, on the pigeon; And for a mantle large and broad, He wrapt him in Religion. HYPOCRISY A-LA-MODE.1