Ripping England!: Postwar British Satire from Ealing to the Goons 1438467354, 9781438467351

Ripping England! investigates a fertile moment for British satire—the period between 1947 and 1953, which produced the f

420 23 5MB

English Pages 288 Year 2017

Contents

List of Images

Acknowledgments

Introduction

America’s Role

The British Postwar Cultural Milieu

1 A Nation Turns Inward: The Setting of Economic and

Artistic Postwar Britain

The Paradox of the New Jerusalem

Austerity Britain

The Art Scene

The Silent Generation

2 “Fog in Channel, Continent Cut Off”: Postwar British

Filmmakers Look Inward

Ealing

Michael Balcon—A Circle Needs a Center

Postwar English Satire Comes to West London

The English Music Hall Tradition

Boomer Nostalgia

3 The Great Bloodless Revolution: Postwar British Film

and the Ealing Satires (to 1949)

British Film Industry at the End of the War

First, the Old Standards

Ealing Arrives: Ealing’s 1945–55 Drama

versus Comedy/Satire Output

The Ealing Satires

4 The Ealing Satires’ Annus Mirabilus (1949)

5 Ealing at a Turning Point (1949 and After)

Spring, 1951—The Festival of Britain

The End of Ealing

6 The Special Relationship: American Satires of the 1940s

Postwar Atmosphere and

American Satires of the 1940s

Lubitsch’s To Be or Not to Be (1942)

W.C. Fields’s Revolt from the Village

The 1940s Satires of Preston Sturges

The European Émigrés and Late 1940s Satire

in the United States

Billy Wilder, Sunset Boulevard (1949),

and Ace in the Hole (1950)

Bob Hope, The Paleface (1949)

The Melodramatic Satires of Douglas Sirk

7 Postwar Britain Faces Its Subconscious: Spike Milligan

and the Goons’ Postmodern Schizophrenia

The Goon Show’s Weekly Topicality

Getting to the Goons:

Milligan, Secombe, Sellers, Bentine

The Goon Show and

Fighting Auntie’s Staid Dominance

A Militant Satirist’s Personal Psychology

and Anti-Authoritarianism

Milligan Challenges a Changing Culture

with a Surreal, Absurd Satire

Rhetorical Devices in Milligan’s Satire:

Sound, Leacock, and Jazz

Structure and Pace of The Goon Show

The Goons’ Characters and

Their Types Become Postwar Staples

The Definition of Insanity: The Goon Show as

Social/Cultural Criticism and the New Popular Culture

8 The Post-1950s Satire Boom: Satire Explodes into Late

Twentieth-Century British and American Popular Culture

Film: The Boulting Brothers and the End of the ’50s

Carry On, John Profumo, and the

Dawn of the ’60s Revolution

Later Satires of the 1970s and 1980s

Theater and Television

Tunesmiths and Wordsmiths

And Finally, Stand Up! People

Epilogue

Is Satire Conservative?

Better Angels?

Ripping England

Notes

Works Cited

Books

Articles

Websites

Index

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Roger Rawlings

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

Ripping England!

Also in the series William Rothman, editor, Cavell on Film J. David Slocum, editor, Rebel Without a Cause Joe McElhaney, The Death of Classical Cinema Kirsten Moana Thompson, Apocalyptic Dread Frances Gateward, editor, Seoul Searching Michael Atkinson, editor, Exile Cinema Paul S. Moore, Now Playing Robin L. Murray and Joseph K. Heumann, Ecology and Popular Film William Rothman, editor, Three Documentary Filmmakers Sean Griffin, editor, Hetero Jean-Michel Frodon, editor, Cinema and the Shoah Carolyn Jess-Cooke and Constantine Verevis, editors, Second Takes Matthew Solomon, editor, Fantastic Voyages of the Cinematic Imagination R. Barton Palmer and David Boyd, editors, Hitchcock at the Source William Rothman, Hitchcock: The Murderous Gaze, Second Edition Joanna Hearne, Native Recognition Marc Raymond, Hollywood’s New Yorker Steven Rybin and Will Scheibel, editors, Lonely Places, Dangerous Ground Claire Perkins and Constantine Verevis, editors, B Is for Bad Cinema Dominic Lennard, Bad Seeds and Holy Terrors Rosie Thomas, Bombay before Bollywood Scott M. MacDonald, Binghamton Babylon Sudhir Mahadevan, A Very Old Machine David Greven, Ghost Faces James S. Williams, Encounters with Godard William H. Epstein and R. Barton Palmer, editors, Invented Lives, Imagined Communities Lee Carruthers, Doing Time Rebecca Meyers, William Rothman, and Charles Warren, editors, Looking with Robert Gardner Belinda Smaill, Regarding Life Douglas McFarland and Wesley King, editors, John Huston as Adaptor R. Barton Palmer, Homer B. Pettey, and Steven M. Sanders, editors, Hitchcock’s Moral Gaze Nenad Jovanovic, Brechtian Cinemas Will Scheibel, American Stranger Amy Rust, Passionate Detachments Steven Rybin, Gestures of Love Seth Friedman, Are You Watching Closely?

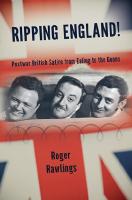

Ripping England! Postwar British Satire from Ealing to the Goons • Roger Rawlings

Cover image credit: The Goon Show on the BBC (1951–60). Image courtesy of Photofest. Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2017 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY www.sunypress.edu Production, Eileen Nizer Marketing, Anne M. Valentine Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Rawlings, Roger, author. Title: Ripping England! : postwar British satire from Ealing to the Goons / Roger Rawlings. Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, 2017. | Series: SUNY series, horizons of cinema | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016056704 (print) | LCCN 2017018251 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438467351 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438467337 (hardcover : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Comedy films—Great Britain—History—20th century. | Ealing Studios—History—20th century. | Comedy films—United States—History— 20th century. Classification: LCC PN1995.9.C55 (ebook) | LCC PN1995.9.C55 R39 2017 (print) | DDC 791.43/617—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016056704 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

List of Images

vii

Acknowledgments

ix

Introduction

1

1

A Nation Turns Inward: The Setting of Economic and Artistic Postwar Britain

11

“Fog in Channel, Continent Cut Off”: Postwar British Filmmakers Look Inward

35

The Great Bloodless Revolution: Postwar British Film and the Ealing Satires (to 1949)

51

4

The Ealing Satires’ Annus Mirabilus (1949)

61

5

Ealing at a Turning Point (1949 and After)

87

6

The Special Relationship: American Satires of the 1940s

115

7

Postwar Britain Faces Its Subconscious: Spike Milligan and the Goons’ Postmodern Schizophrenia

145

The Post-1950s Satire Boom: Satire Explodes into Late Twentieth-Century British and American Popular Culture

177

2

3

8

vi

Contents

Epilogue

203

Notes

213

Works Cited

251

Index

259

List of Images

Figure 1.1

Princess Elizabeth, 1949.

10

Figure 1.2

Clement Attlee, 1950.

16

Figure 1.3

William Beveridge, c. 1950s.

19

Figure 1.4

Kingsley Amis, c. 1950s.

25

Figure 2.1

Michael Balcon, c. 1938.

38

Figure 2.2

Gracie Fields, 1943.

44

Figure 3.1

Hue and Cry (Charles Crichton, 1947).

59

Figure 4.1

Winter, 1947.

65

Figure 4.2

Passport to Pimlico (Henry Cornelius, 1947).

70

Figure 4.3

Whisky Galore! (Alexander Mackendrick, 1949).

73

Figure 4.4

Kind Hearts and Coronets (Robert Hamer, 1949).

81

Figure 4.5

Kind Hearts and Coronets (Robert Hamer, 1949).

83

Figure 5.1

The Lavender Hill Mob (Charles Crichton, 1951).

95

Figure 5.2

The Man in the White Suit (Alexander Mackendrick, 1951).

99

Figure 5.3

The Titfield Thunderbolt (Charles Crichton, 1953).

104

Figure 5.4

The Ladykillers (Alexander Mackendrick, 1955).

111

Figure 6.1

To Be or Not to Be (Ernst Lubitsch, 1942).

120

Figure 6.2

The Paleface (Norman Z. McLeod, 1948).

140

vii

viii

Illustrations

Figure 7.1

The Original Goons with Michael Bentine, c. 1951. 151

Figure 7.2

The Goon Show on the BBC (1951–60).

163

Figure 7.3

Later Milligan, with Peter Sellers in The Great McGonagall (Joseph McGrath, 1975).

175

Figure 8.1

Withnail and I (Bruce Robinson, 1987).

189

Figure 8.2

Mark E. Smith and The Fall, 1980s.

194

Acknowledgments

When I first started thinking about postwar British satire about ten years ago, there wasn’t even an entry in Wikipedia for Ealing studios, let alone the Goons. The idea for this work began during my PhD studies at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, still—after so many political attempts to strip it of its mission or forcing it to operate on a perennial shoestring—one of the great public institutions in the nation. I especially am indebted to my directors of that time, Luke Menand, Morris Dickstein, Norman Kelvin, and most of all, the incomparable and hilariously brilliant Peter Hitchcock. Also deserving thanks is Professor Robert Pattison, who made pragmatic and stylistic suggestions. Thanks to Dr. Robert Eisinger for his continual encouragement, and to the many graduate and undergraduate students who endured my prattling on about the genius satirists working in Britain after World War II. I am grateful to various libraries, institutes, and their diligent worker-bees: the BBC and the BFI in London; the Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center; the Bobst Library at NYU; the library at the CUNY Grad Center in New York; and the librarians at Florida Atlantic University, all of whom were most valuable in tracking down books and obscure material that helped shape the ideas found here. Also, many thanks to my inspirational colleagues at PBSC and YipTV.com. Kudos must also be extended to the head editor at SUNY Press, James Peltz, for his constant encouragement, and James’s assistant Rafael Chaiken, and Senior Production Editor Eileen Nizer, who answered many questions patiently and precisely along the way. Most of all, a shout out unquestionably to the head editor of the Horizons of Cinema series, the ingenious Murray Pomerance, whose work I have admired from afar for many years, and who saw the value in the thesis from the beginning. Murray pushed and pushed until the chapters pleased what the Peer Reviewers might flag as lacking, what the marketplace needed,

ix

x

Acknowledgments

and what would make this an original piece of work. His own irreverent and feisty punk rock attitude was a welcome shot of adrenaline again and again the whole way through. And finally, to my supportive family, and above all my dad, Walter Edward Rawlings (1930–2014), who turned me on to so many of these works, and made sure that the postwar British satirists, and their incessant questioning of often undeserved British purloined privilege and their finger-on-the-pulse reflections of changing national mores, were a major part of my upbringing. This book is dedicated to him.

Introduction What we in hindsight call change is usually the unexpected swelling of a minor current as it imperceptibly becomes a major one and alters the prevailing mood. —Morris Dickstein

•

HIS IS A STUDY OF POSTWAR BRITISH film satire. It is purposefully a comparison study. It asks the long overdue question, “Compared to the major postwar filmmaking cinemas, Italian, French, Scandinavian, and, yes, American, why hasn’t British film of the same period been equally considered as a major contributor?” Ripping England! briefly considers those other various European outputs and holds them against the British satires. It then compares them further to the American ones being made simultaneously. The postwar British satires hold up more than well against the work of their other Western counterparts. Everyone knows of Europe’s postwar cinematic miracles. They have been written about extensively. Italian filmmakers sought to document the war’s devastation through a new genre of neorealism using stock footage, off-the-cuff on-location shooting, and whatever raw film stock they could get their hands on. They gave us such classics as Roberto Rossellini’s Open City (1945) and Vittorio De Sica’s The Bicycle Thieves (1948). In 1945 France celebrated liberation with the release of Marcel Carné’s The Children of Paradise and Jean Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast. Ingmar Bergman’s debut as a film director came in 1946 with Crisis. After the destruction of World War II, Italy, France, and northern Europe built on their existing cultures of cinema

T

1

2

Ripping England!

to produce innovative films that reflected their societies’ reconstruction and renovation. The filmmakers contributed to what would be recognized as a new wave in cinema, and ultimately, a new Europe in a modern world. The same process occurred in Britain, but the British cinematic miracle is little discussed and often unacknowledged. Reduced to making “support the war-effort” propaganda and documentaries during the war, British filmmakers also started afresh after 1945, first by going back to their literary classics, from Shakespeare to Dickens, but then, more importantly, as they got further away from the traumas of war, to their national tradition of satire. Though respected by Hollywood, critics, and the public for the intensity and zaniness of their characters and narratives, the postwar British comedies weren’t mere “comedies” but great achievements of high satire—key cultural documents in understanding a new England facing a new world. Ripping England! will investigate the work of certain writers, filmmakers, and performers working in postwar England, and identifies the period between 1947 and 1953 as a particularly fertile moment for British satire—a time when British cultural identity was redefining itself amid a socioeconomic landscape of loss of empire, crippling rationing, and Labour’s newly implemented welfare state. This book will look at the too often neglected miracle of postwar British cinema and popular culture.

America’s Role After World War II, all Europeans and European filmmakers were dependent on America in some way, either financially or aesthetically. Italian and French directors still looked to emulate the style and structure of American films. Neorealism wanted to be a new genre, but its ashcan grittiness had already been popularized by the American social realist (I’m a Fugitive from a Chain Gang) and films noir (The Maltese Falcon) movements in the years leading up to U.S. entry into the war in 1941. The Children of Paradise aspired to be a French Gone with the Wind, and later the French New Wave auteurs revered the Hollywood cartel. For the British and their popular culture, there was a special relationship with America. In the political and economic aspects of this consociation, the British were subservient, like the other Western European societies wrecked by the war, but in their cinema and popular culture, they did like the French and Italians and cultivated their own cultural sensibilities on the root stock of American money and production. Especially in film, they more than held their own, as a comparison of British and American satires will show.

Introduction

3

Did postwar America actually understand these satirical works that French critics (who most certainly did not understand them) labeled, in a Franco-centric anti-Anglo-Saxonism, “small” films? Not really. During the 1930s and through the war years, there essentially were only four types of “England” known to Americans, all of them somewhat mythological: • Ye Merry Olde England of Friar Tuck and Robin Hood. • The England of Shakespeare, Dickens, Sherlock Holmes, and the Bröntes. • The English historical dramas (Henry VIII; Mary, Queen of Scots), and the family sagas (How Green was My Valley; Wuthering Heights) often created by classical American Hollywood directors like John Ford and William Wyler. • And finally, the England that gallantly pulled through the war (Foreign Correspondent; Mrs. Miniver). It was a very narrow and myopic comprehension. There were British directors (Alfred Hitchcock, Frank Lloyd, Edmund Goulding, and Robert Siodmak–technically German, he had learned the craft with Hitchcock at Ufa, but like Hitch he worked in England before fleeing to the states) and actors (Ronald Coleman, C. Aubrey Smith, Laurence Olivier, Robert Donat, Cary Grant, Madeleine Carol, Charles Laughton, Vivian Leigh, and Joan Fontaine; Errol Flynn was Australian) already working in Hollywood–some had gotten their start in silents, but most were there mainly because Hollywood turned to more posh, clearly-enunciating English voices as sound entered the picture in the late 1920s. Before the war, MGM was the most Anglophelic studio making a calculated stab at “costumes and classics/castles and castes” Brit-centric fare as it depended on English-speaking foreign box office to round out their revenue. This was seen in such films as Mutiny on the Bounty (1933), Alexander Korda’s The Private Life of Henry the Eighth (1933), the Euro flair of their “tiffany” stars like Greta Garbo, and of course, the melodramas produced by Sidney Franklin, including Goodbye Mr. Chips (1939); the other successful film before the war was Noel Coward’s Cavalcade (Frank Lloyd, from Fox, 1932). These films illustrated the difference between “British” film and British film—idealized Hollywood representations that sought to fulfill audience expectations about England vs. the more prosaic truth—exactly what Ealing and the Goons would change after the war.1 Until then, Americans still thought of England in stereotypes.

4

Ripping England!

By the time America joined the war at the end of 1941, two long years of constant combat had exhausted the British people fighting off invasion. Soon more than two million Americans were stationed in England alone, albeit on bases that were made to feel homelike—American outposts with baseball diamonds and canteens serving American food and products—islands within an island. Though mixing with average Britons, these Americans were sheltered, too. America and Britain tried to understand each other better. Edward R. Murrow reported on British life as the war geared up, and Alistair Cooke was sent to tour rural America and send his reports back to explain that strange land to the former mother country.2 The two English speaking countries were foreign to one another and would only really get to know each other in the aftermath of war through their popular cultures, especially their satiric films. By the 1960s, both countries’ satiric offerings would create one of the great transatlantic cultural exchanges of the twentieth century, without each really acknowledging it as being so. That would come later, with Beyond the Fringe, the satires the Bronxborn Kubrick made in England (Lolita and Dr. Strangelove), the American director Richard Lester’s Beatles’ films, and eventually Monty Python and its American conjunction Saturday Night Live (created by a Britishinspired Canadian, Lorne Michaels) in the States. A few points are clear: • At the time, America certainly recognized oddball characters from her own tradition of regionalist humor (Mark Twain/Damon Runyon), so they would’ve mostly “got” the capricious denizens in Lavender Hill Mob and Ladykillers, though the Scots in Whiskey Galore! may have been much more of a challenge, as they still are today (Trainspotting; Death at a Funeral; My Name is Joe). • More sophisticated eccentrics such as Dennis Price in Kind Hearts and Coronets or Alec Guinness in Our Man in Havana probably only appealed to upscale, cosmopolitan sensibilities in large cities like New York and Chicago who sought out such quixotic fare. • The Goons, however, would not have been understood by Americans in the 1950s at all; instead they were laying the groundwork for Beyond the Fringe and the Pythons that came in with the anything-goes 1960s (The Goons’ foremost talent, Peter Sellers, would be the secret-weapon star

Introduction

5

of both of Kubrick’s early 1960s English-American satires). But Americans would have been used to comedians who had honed much of their craft in England and Europe, such as Charlie Chaplin, Cary Grant, Jack Benny (he was stationed overseas during World War I), and Bob Hope (Hope was born in Eltham, London, in 1903; many of his early World War II USO appearances brought him back to England in the 1940s). • The more esoteric or high-brow satire (the kind later institutionalized in publications such as Private Eye) really was an English thing—an English scheme. Even today, after all the transatlantic exchanges of English Premier League (EPL) soccer matches, Downton Abbey, Masterpiece Theatre, and BBCAmerica, smaller English/Scottish films still have had a hard time reaching anything more than a cult audience—think Steve Coogan/Rob Brydon in the Trip films, cross-dressing comedians like Eddie Izzard, or artistic geniuses like Mark E. Smith of The Fall. Most British actors and artists today, if they are recognized at all, are known usually because they are cast in major roles in big-budget superhero films (Christian Bale/Tom Hardy, etc.) or in Game of Thrones, or by audiences now used to their seasonal doses of Helen Mirren, Dame Judy Dench, Maggie Smith, the Redgraves, Colin Firth, Hugh Grant, and Emma Thompson, especially when they play English royalty, which is catnip to American audiences’ fetish for crowned heads come Oscar time. In sum, it is true that most Americans were still not really familiar with English quirks and idiosyncrasies in the late 1940s (though some of the troops would become accustomed to them). The British films of this era were, to outsiders, exotic and peculiar, one reason they were called “little.” And they were new stories often about working- and middleclass lives struggling to survive in the new Age of Austerity—people who today are the Brexiters, who regularly read The Daily Mail, who those in the press label “little Englanders.” At the same time, the American satires of the period (of W.C. Fields, Jack Benny, Preston Sturges, and Bob Hope) were just as strange, and just as culturally significant, to British audiences. British and American comedies and satires explained each nation to the other in a detailed (not to mention brilliantly hilarious) way. Taken together,

6

Ripping England!

these British and American satires would help forge a shared Englishspeaking postwar mentality that buttressed the special relationship. To understand this relationship better, included here is a chapter on what America was doing in a similar vein at the same time as the British satires.

The British Postwar Cultural Milieu Much has been written about the Angry Young Men (John Osborne, Alan Sillitoe) and the Movement writers (Philip Larkin, Kingsley Amis) of the mid-1950s; but the satiric artists and filmmakers discussed here were making their commentaries earlier, in the immediate aftermath of the war’s end. Possibly one of the reasons the postwar satires have been overlooked is what Ben Shephard describes as the “goodie-goodie” problem of history: It raises what the writer Gitta Sereny has called the “goodiegoodie” problem. How, in our modern culture—where evil is sexy, goodness is dull, and organized goodness is dullest of all—can we find a way to make organized altruism interesting? The selling of Hitler was in the hands of Joseph Goebbels, Albert Speer, and Leni Reifenstahl, who created an iconography which still pervades popular mass culture today [see The Daily Mail and Fox News]; whereas the selling of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (and the humanitarian ideal it stood for) was entrusted to the National Film Board of Canada, whose feeble efforts to create an imagery of international brotherhood and cooperation are long forgotten.3 This historical problem is the same problem the British comedies have had in gaining respect. They seem on the surface frivolous, but really are the veridical representations of the British people and their humorist ethos imbedded in their popular culture of the late 1940s and early 1950s. But if the task is daunting, it is also necessary if history is to consist of more than “the mass killers of our time—crazed despots, the perverted henchmen, their army chiefs” and do justice to their opposites, “the healers who spent themselves in trying to prevent or redress the deliberate inhumanity of those with the power to hurt.”4

Introduction

7

Even today, the History (sometimes referred to as the “Hitler”) Channel and its cognates show rerun after rerun of the evil deeds of the mid-twentieth century, while the great humanitarian efforts go far less heralded.5 Writing about Eric Auerbach’s affinity for reality-based fiction (Mimesis, 1953), Arthur Krystal notes that “Auerbach tended to undervalue the comic and, consequently, gave short shrift to both Dickens and Thackeray.”6 The Ealing/Goons satires have suffered a similar fate; they have not been taken seriously by historians or analysts of the period who have been too intimidated by the giants of French, Italian, and Scandinavian postwar cinema to admit so. They should be. Earlier British upheavals had produced consonant eruptions of British satire. After the revolutions of the seventeenth century, Butler, Dryden, Swift, and Pope used satire to address the social trauma and define a new age. Revolutions in America, France, and industrial society were followed by the satires of Austen and Byron. After World War II and the end of empire, with a furiously changing national mood and economic situation, the Brits again turned to satire to understand where they were and what they might become. The first chapter of this book provides the historical background against which British satire flourished in the wake of war—the international and domestic crises the Attlee/ Labour administration consistently faced, and the plans the government was making to make sure safety nets were put in place for all her subjects, from full employment to health care for all. Some would be successful, some not so much. Chapter 2 explores how the new, younger artisans working at Ealing turned inward, not concerned with what their counterparts on the continent—the Italian neorealists, the French tradition of Qualitiers, the Scandinavian existentialists—were proposing about the medium. Instead, they sought to bring British topical stories to the quickly shrinking-fromthe-Empire island nation, and did so through a dogged work ethic, which placed less emphasis on proposing new theories about the cinematic medium than reflecting the postwar austerity-laden atmosphere. For this reason, as well as not being as melancholically inclined, the British satires have been ignored by critics and academics who pined for the European movements that shaped their formative years. Britain was more idiosyncratic and self-reliant. Its own tradition of music hall and satire provided their artistic model for soul searching. The remaining chapters seek to show how the British satires of the late 1940s and early 1950s were a highly original, authentic, indigenous response to a nation’s critical identity crisis. Chapters 3, 4, and 5 concentrate on the Ealing satires, especially the great year 1949, when Ealing truly hit its stride with three masterpieces: Passport to Pimlico, Kind

8

Ripping England!

Hearts & Coronets, and Whisky Galore! Then later, early 1950s film texts considered here include The Man in the White Suit (1951), The Lavender Hill Mob (1951), The Titfield Thunderbolt (1953), and The Ladykillers (1955), among others. To put the British experience in perspective, Chapter 6 looks at American satires doing similar work for American culture and society at the time, from the sophistication of Ernst Lubitsch/Jack Benny, Eddie Cline/W.C. Fields, Preston Sturges, and to the European exiles such as Lubitsch, Billy Wilder, and Douglas Sirk, who fled European destruction to live and work in Hollywood, whilst still producing serious critiques of postwar American life. The British satirists concentrated on their own uptight little island, but would’ve been somewhat aware of these dark and funny American films because of the unique nature of film distribution, the shared language, and the “special relationship” Churchill described in his “Iron Curtain” speech of 1946.7 Chapter 7 unpacks the amazing work of the militant satirist Spike Milligan, along with the versatile performers Peter Sellers and Harry Secombe and their BBC radio program, The Goon Show, which was also at its most prolific during this period. The final chapter discusses later English satires inspired by these postwar artists, including works from Beyond the Fringe, the Beatles’ mid1960s films (A Hard Day’s Night and Help!) and the Kubrick-in-England Anglo-American satires, to later satires on TV (Monty Python), in print (Private Eye, founded in 1961), on film (Withnail and I), in music (The Fall), and on stage (Bill Hicks). Satire became the dominant genre in both Britain and the United States in the entertainment industries after the great upheaval. These ingenious satirists questioned the moral certainties and absolutes of those (often insular) groups that held sway and power for so long in both countries, from the religious and political to the hidebound “preservationist” societies. The British satires of the late ’40s and early ’50s held up a mirror to an England rife with change, helping to codify who they were and where they were headed as a newly inward-turning island culture. As Morris Dickstein explains in the quote that starts this section, these shifts often occur imperceptibly, and Britain’s artists and filmmakers didn’t realize it at the time, but they were changing and affecting their culture and society irreversibly through their uniquely indigenous and subsequent pasquinades. Our hope is that readers will come away with a new appreciation of how the postwar British satirists and artists negotiated the cataclysm of the late 1940s and early 1950s through humor and militant irony. As a final note, “Ripping England! ” has multiple meanings. The title denotes the fact that there arose in the aftermath of the war a new

Introduction

9

satiric movement that tore old England a new one. It is also meant as a signpost—that this study will document the sheering away of the old world from the new. And, most importantly, the title signifies the divide between those who pined for tradition and those who wanted to move on and gain a new place in a culture that had for so long closed them out. “Ripping England” is meant as a not-so-gentle jesting of the moorings that were coming loose from their bearings in a midcentury England forever changing, for better or for ill.

Figure 1.1. Princess Elizabeth, 1949, two years before her ascension. Photofest.

1 A Nation Turns Inward The Setting of Economic and Artistic Postwar Britain

But while they speed the pace of legislation With sleepless ardour and unmatched devotion, The lower strata of the population Appear to have imbibed a soothing potion; Faced with the mighty tasks of restoration The teeming millions seem devoid of motion, Indifferent to the bracing opportunity Of selfless service to the whole community. It is as if the Government were making Their maiden journey in the train of State, The streamlined engine built for record-breaking, Steaming regardless at a breakneck rate, Supposing all the while that they were taking Full complement of passengers and freight, But puffing on in solitary splendor, Uncoupled from the carriages and tender. —from “Let the Cowards Flinch,” published in The New Statesman by Sagittarius (pseudonym for Olga Katzin), October 1947

•

11

12

Ripping England! HE WAR’S END BROUGHT JUBILATION

T

and relief. But it also brought new cultural and economic monsters for Britain: postmodernism and the end of empire. The elements of prewar modernism—Freud, Darwin, relativity, fragmented sense of self, an obsession with the capacities of language, and the introduction into the marketplace of new technologies such as airplanes and radios—had transformed Western and world culture. The new postwar period was shaped by its own preoccupations and technologies, which included everything from the atomic bomb and antibiotics to computers and the search for a solution to the mystery of heredity in the structure of DNA. This time the fate of the planet was at stake, not just vagaries of economic or psychological structures. This was a new age and a new world where cause-and-effect were practically simultaneous. For the theorist/geographer David Harvey, the struggle between utopian visions and dystopian realities of the mid–twentieth century was due to what he calls the “Space-Time Compression,” brought on, invariably, by capitalism and its push for faster modes of production and transportation: I use the word “Compression” because a strong case can be made that the history of capitalism has been characterized by a sped-up pace of life, while also overcoming the spacial barriers so that the world seems to collapse inward on us. As space appears to shrink to a “global village” of telecommunications and “spaceship earth” of economic ecological interdependencies, and as time-horizons shorten to the point where “the present” is all there is (the world of the schizophrenic), so we have to learn how to cope with an overwhelming sense of compression of our spacial and temporal worlds.1 Under the influence of what is now labeled High Modernism or Postmodernism, this newly sped-up world collapsed the imperial boundaries Britain had long sustained into a messy global conflation. Or as Jameson put it, Taken together, all of these perhaps constitute what is increasingly called postmodernism. The case for its existence depends on the hypothesis of some radical break or coupure, generally traced back to the end of the 1950s or the early 1960s. As the word itself suggests, this break is most often related to notions of the waning or extinction of the hundred-year-old modern movement (or to its ideological or aesthetic repudiation). Thus, abstract expressionism in painting, existentialism in philosophy, the final forms of representation in the novel, the

A Nation Turns Inward

13

films of the great auteurs, or the modernist school of poetry (as institutionalized and canonized in the works of Wallace Stevens): all these are now seen as the final, extraordinary flowering of a high modernist impulse which is spent and exhausted with them.2 So, the arts, too, began to shift to capture this unwieldly new historical and cultural paradigm, and within them would be seen new aesthetic preferences: for more outrageous and farcical structures, for fragments over wholes (including the idea of the joke without a punchline), for an incessant reliance on irony and pastiche, and for a distrust of catharsis, closure, and even critical analysis of its own relentless force. What it is called matters less than its 24/7 psychotic pop-culture dominance. Today it is simply known as hegemony, but before 1939, England had a long history of cultural imperialism.3 To take but one example, the forcing of the English language onto cultures that came under the spreading empire as the English establishment attempted to eliminate all non-English languages within the “British Isles” cohort (Welsh, Irish, and Scottish Gaelic) by outlawing them or otherwise marginalizing their practitioners.4 By the nineteenth century, the British imperial system extended around the globe. It was a legacy that vexed postwar Britain. Besides a tattered empire, postwar Britain also faced a financial catastrophe that was its most immediate reality. In 1945, after six years of war, to those in tune to economics or politics, British hegemony was mortally impaired, even if their cultural dominance appeared, especially to the British themselves, to continue unabated. “England as a great power is done for,” sighed Evelyn Waugh into his diary in 1946. “The loss of possessions, the claim of the English proletariat to be a privileged race, sloth and envy, must produce increasing poverty . . . until only a proletariat and bureaucracy survive.”5 Paul Addison adds that, When the Marxist left and radical Right emerged in the 1970s there was one point on which they were agreed: that many seeds of decline were planted in the immediate postwar years. According to the Marxist left, this was because socialism and the class struggle were betrayed. According to the radical Right, it was because free market forces had been stultified by the Welfare State and the managed economy.6 Whichever view is correct, and it is probably some combination of the two, the new Attlee government, and politicians in general, wanted to maintain the image of Rule Britannia, even as the nation felt its decline more and more each day.

14

Ripping England!

Led by the United States, the victorious Allies formed the United Nations in 1945, and the 1947 American Marshall Plan (or the European Recovery Plan, as it was known overseas) was another calculated strategy to sustain America’s newly gained upper hand at Britain’s expense.7 The plan offered billions in aid to countries that maintained (mostly) democratic governments and (mostly) political allegiance to the United States to prevent them from drifting into the communist orbit. Many nations insisted on reinforcing or reviving their distinct cultural identities, complaining that in fashion, advertising, and mass media, among other areas, Europe was becoming a colony of the States. The domination of American film offers a good example of how the United States prevailed culturally and financially in these years. The lending of Marshall Plan funds was carefully tied to acceptance of the Motion Picture Export Association of America’s (known as the Blum-Byrnes agreement) terms of American film as the best form of propagandic defense against communist and fascist tendencies. Also, the major European filmmaking countries began to reestablish their industries, using American film and culture as influence for their styles. Godard would categorize the postwar climate as “Coca Cola and Marx.” He wasn’t far off: the two products that were nonnegotiably attached to the Blum-Byrnes/Marshall Plan funds were Coca Cola and American movies; no two products would be more effective in spreading American-style democracy, the thinking went.8 And this demand was also made on America’s closest ally, Britain. But after victory, Britain and her people were too caught up in the triumph and the utopian ideals of the coming New Jerusalem to notice such incursions. In Britain, it would be the postwar satirists who would have to point out the truth to them, laughingly.

The Paradox of the New Jerusalem Even though he hoped to continue a Coalition government, at least until the war in the East was over, Churchill called a national election for July 5, 1945; the results were not released until July 26, 1945, and Clement Attlee won in a Labour romp.9 It was the first general election in over ten years and the first noncoalition government in over five. A number of shifts factored in to the move toward Labour. Martin Pugh writes, Between the outbreak of war in September 1939 and the general election of July 1945 political fortunes in Britain changed drastically in favour of the Labour Party . . . The result was essentially a defeat for the Conservative Party rather than Churchill; for the Conservatives were labeled the “Guilty Men”

A Nation Turns Inward

15

whose pursuit of appeasement had left the country unprepared for war . . . Moreover, the Labour Party could no longer be written off as dangerous or unfit to govern as in the 1930s. Its (Labour’s) leading figures, particularly Attlee, Morrison and Bevin, had served with distinction in the wartime coalition since 1940 . . . in short the mood of 1945 was very close to what one historian has called “Mr. Attlee’s Consensus.”10 Not only was there a rejection of the Conservative stance that many felt led to war in the first place, but there was also a new generation who had been born after World War I and came of voting age during the Depression. In other words, an entirely new electorate: In addition the electorate had changed considerably since the last election in 1935. As many as one in five electors were voting for the first time, and of these 61 per cent are estimated to have supported the Labour Party—a reflection, no doubt, of their education during the depression and the rule of National Governments.11 And Ross McKibbin notes: The second, in many ways the most attractive explanation, simply does away with the problem of “conversion” (did people change their political allegiances during the war?) by arguing that Labour’s victory was the delayed effect of generational and demographic change. It suggests that those who voted Conservative in 1935 mostly continued to do so, [but] by 1945 Labour was supported by a new cohort of voters who were politically socialized by the interwar years . . . In other words, a high proportion of those voting in 1945 reached political maturity after the Labour Party had become the second party of state.12 Further, it might have been the newly implemented mandatory educations in the armed forces that turned the younger cohort toward Labour: A once popular version of the “wartime-change” explanation of the Labour victory was the radicalization of the armed forces; an assumption that there was something about military experience which radicalized men and women in ways life did not do for those still on the civvy street.13

16

Ripping England!

For all its ills, war throws disparate groups together. And disparate groups learn about the world much faster and to accept human differences much better, which is hardly “radicalization.” However, what was more surprising was that Labour had even moved past the Liberal Party in stature and influence for the first time in its history. By the Second World War Labour had emerged as the standard-bearer of the key elements in radical Victorian politics: it incorporated Gladstonian tradition in foreign affairs; it was a party of causes; it maintained libertarian principles; and it propagated improvement through social reform.14 By the end of the 1930s, Labour had secured much more support from the middle classes, especially in regions such as the Midlands, Yorkshire, Manchester and Liverpool, East Anglia, Scotland, and, not least of all, the many soldiers from all over Britain who were now stationed or chose to permanently live in London. Churchill lost not because Britain wasn’t thankful; he lost because of these undeniable mitigating factors.

Figure 1.2. Clement Attlee, 1950. Architect of postwar England’s New Jerusalem. Photofest.

A Nation Turns Inward

17

Additionally, and probably most importantly, he lost because of what Labour had been promising since even before the war, in which the working masses were pledged a newly prosperous and “accountableto-all” Britain. This would be England’s New Jerusalem.15 Whereas 1940–45 in France demonstrated the bankruptcy of France’s institutional culture and intensity of her internal divisions, in Britain it signaled the vindication, almost the apotheosis, of the institutional and national consensus that the victory of the Labour Party in the general election of 1945 seemed to many foreign observers an almost revolutionary event. In reality it marked the strength of the institutional consensus in Britain at the same time as it created a new set of policy priorities that would become the guiding maps of the postwar order. . . .”16 Britain faced a paradox: the people wanted to “get back to normalcy” as the war wound down, but also to “Never Again!” (Attlee’s renowned platform in 1945) return to how things were before the war in the era of the Great Depression and almost zero social services for the masses who had helped keep Britain intact. Attlee’s high-wire act had to span this double-bind throughout his years in office, from 1945 to 1951.17 The “New Jerusalem” Welfare State was the result of William Beveridge’s white paper issued in the winter of 1942–43, which identified five “Giant Evils” in society: SQUALOR, IGNORANCE, WANT, IDLENESS, and DISEASE (they always appeared in CAPS), and a series of changes were put in place to deal with them.18 “The Beveridge Report” sold more than 100,000 copies in its first month alone, astonishing numbers for a very poor population of only forty-six million in 1943–44; but people wanted to know what their future might look like in a new Britain that would finally take care of all her own, no longer just the privileged few. The eventual magisterial account [by Ministry of Health head Richard Titmuss], Problems of Social Policy (1950), would make canonical the interpretation that there had indeed been a seachange in the British outlook—first as the mass evacuation of women and children from the main cities brought the social classes into a far closer understanding than there had ever been before, then as the months of stark and dangerous isolation after Dunkirk created an impatient, almost aggressive mood decrying privilege and demanding “fair shares” for all. Between them [Titmuss’s assessment, who

18

Ripping England! began it in 1942, and Beverage’s report], according to the Titmuss version, these two circumstances led to a widespread desire for major social and other reforms of a universalist, egalitarian nature.19

The report revealed that the government had at last recognized the responsibility to care for its people “from the cradle to the grave” (or, as some preferred, “from the womb to the tomb”). The proposed changes promised a government commitment to health (DISEASE)—in 1948 the National Health Service was created; education (IGNORANCE)—from 1944 the Butler Act raised the school-leaving age to fifteen and guaranteed education for all; employment (IDLENESS)—guaranteed “full” work; housing (SQUALOR)—Labour passed the Town and Country Planning Act in 1947; and social security (WANT) for the elderly and infirm—the National Insurance Act of 1911 was greatly expanded in 1946 (The National Health Service Act).20 These may have seemed like new ideas to voters in 1945, but Pugh also suggests that thoughts about managing the economy in good times and bad had begun in fact after World War I. In the immediate aftermath of 1918 even socialists often regarded wartime controls as a unique experiment rather than as a pointer to future strategy. . . . However, by 1923, in the face of mounting unemployment, the ILP was in retreat from guild socialism, and began to concentrate upon the techniques for managing the economy. The ILP’s [Independent Labour Party] Socialist programme of 1923 displayed an underconsumtionist approach in the emphasis it laid upon raising and stabilizing the demand for products of industry by a more equal distribution of incomes. Indeed the ILP had already begun to study Keynesian ideas to some effect: it identified a scientific credit policy as the means of moderating the fluctuations in the economy; and unemployment was ascribed basically to inadequate purchasing power which was itself a consequence of insufficiency of bank loans. Thus, state management of banks and credit seemed to the ILP crucial for economic planning; and the extension of control over other industries was similarly seen in the light of what each would contribute to costs, prices, production levels and so forth.21 Managed economies were clearly now possible after the visibly successful fiscal stewardship by America and Britain during the war.

A Nation Turns Inward

19

Figure 1.3. William Beveridge, c. 1950s. Eradicator of England’s five “Giant Evils.”

In any case, the New Jerusalem was an ambitious plan and a noble gift to the heroic nation, but, there was one problem: the continuing belief that Britain could still afford to maintain a worldwide empire. After the high cost of the fight with the Axes, including the huge debt in loans owed to the United States, and the impossibly exorbitant cost of sustaining overseas territories that no longer brought wealth back to the island nation, there were less than zero resources left to pay for the New Jerusalem. Even before 1945, the British Empire had begun its transformation into a Commonwealth. The (white) colonies of Canada (1867), Australia (1901), New Zealand (1907), and the newly created Union of South Africa (1910) became federated self-governing Dominions.22 After the war, Britain’s heavy war debts created a climate within both the public and policy elites that was increasingly doubtful of the continued benefits of the remaining imperial possessions.23 The Indian Independence Act of 1947 was the biggest pillar to fall, as it partitioned the colony into two newly free nations, India and Pakistan, creating its own set of political quandaries and challenges, but it wasn’t the only one. The skeptical British historian Correlli Barnett has explained away this decline as the British simply ignoring what it took to maintain dominance in world industry:

20

Ripping England! Britain has been a nation blinded by pride (of being a world power) to the signs of decay at the technological roots of its strength . . . a (clear demonstration of how) a nation will cling to the political and economic faiths of the past.24

Britain may have been blinded by past glories, but despite the march toward state-sponsored support for all its citizens, and even with the new Labour change of government, the British people and its political classes were still very cautious about implementing the new schemes immediately, and it took every bit of the six years Labour was in power to fully do so. To argue that taking a Scandinavian course, and settling for a prosperous, inward-looking northern existence, was a runner in 1945–51 is to succumb to another set of delusions. The whole weight of British history and recent experience was against that—not to mention urgent necessities and inescapable responsibilities with which the Attlee Government was confronted.25 These would include sticky situations in the Middle East (most notably what to do about Palestine and the possible creation of the Israeli state), the currency dilemma, and, by 1950, Korea. The British still thought that they were entitled to some postwar spoils, but they weren’t. However misguided it may appear now, they thought they had won. Unlike General de Gaulle, Attlee and Bevin found vacant seats waiting for them at Potsdam. Britain was one of the victor states occupying the territory of her former enemies; a Permanent Member of the Security Council with the power of veto; still head of a large empire with widespread possessions; well ahead of any other state except the two superpowers in military, industrial and technological resources. Her interests and responsibilities were worldwide, at least as wide as those of either Russia or America. For her to abandon these, or even seriously reduce them, at short notice was out of the question. Apart from its effect abroad, it would have been a blow to national morale that no newly elected government could be expected to strike after a war from which Britain [after all] had emerged victorious.26

A Nation Turns Inward

21

This was the basic paradox facing postwar Britain: it wanted to be a twentieth-century northern European welfare state and at the same time a nineteenth-century global power. (Pugh even suggests that the real visionary of England’s decline had been Conservative leader Stanley Baldwin (Earl of Bewdley), who was thinking such thoughts even before he became Prime Minister in the mid-1930s.)27 The end of empire resulted in postwar Britain living through an anxious and uncertain time where fundamental economic difficulties and social dissatisfactions overtook so much of the early postwar hope, whose own “new” order would become persistent and unrelenting austerity.

Austerity Britain Britain’s biggest problem was its currency and trade imbalance, an economic cataclysm not waiting to happen, but happening now; it was the most sobering meaning of the term “aftermath.”28 From 1947 to 1949, the United Kingdom had an international trade deficit of almost £300 million. This doesn’t sound like very much to us today, but for the late ’40s, and for an empire that was used to being a worldwide creditor, it was seemingly intractable.29 Two-thirds of Britain’s prewar international trading partners were in rubble or had turned to the United States, many of its patents had been sold off to pay for the war, and its military, especially its mighty navy, was decimated. But the biggest shock to their system was the instant canceling of Lend-Lease (the program put into place in early 1941 by FDR that had allowed him to “rent” materiel goods to Britain without violating the Congressional ban on sending aid to either side of any international conflict) by Roosevelt’s successor Harry Truman on August 25, 1945.30 We were, in short, morally magnificent but economically bankrupt, as became brutally apparent eight days after the cease-fire in the Far East when President Truman severed the economic lifeline of Lend-Lease without warning. Lend-Lease, “the most unsordid act in the history of any nation” as Churchill called it, was negotiated in the early months of 1941, well before the United States had entered the war. “Unsordid,” the beginning may have been, but the end of Lend-Lease was undeniably brutal. . . . Material already in transit would have to be paid for straight-away and an audit would have to be drawn up of all unconsumed Lend-Lease items in Britain. “Thus,” as Sir Alec Cairncross starkly recalled, “what had provided the

22

Ripping England! United Kingdom with roughly two-thirds of the funds needed to finance a total external deficit of £10,000 million over six years was withdrawn unilaterally without prior negotiation.”31

It was an instantaneous blow that would resonate for an entire decade, if not more—at the very least, until Attlee and his ministers agreed on devaluing sterling in 1949.32 The contrast of the GDP before and after the war paints the “hard numbers” picture: if it had been growing by 4.64 percent in 1939 (and that was still in The Great Depression), by 1949 it was only .102 percent, and still just 1.6 percent in 1955.33 Literally all resources were expended on paying down the foreign debt, and keeping the pound down to sell goods for export. And to make matters worse, the United States then insisted that sterling (a major worldwide currency before the war) be fully convertible to dollars by 1947. So, Britain embarked upon a postwar export drive, which was only possible at a price of a fairly hard life for most people. One sign of the times was the frequent use of billboard hoardings encouraging the British worker to ‘work or want,’ a message which the average British worker was only too aware of, and yet did not want to hear, after so many years of hardship and deprivation. The stringencies of postwar food rationing were all too obvious at the time, as was the acute shortage of housing, clothing, furniture, and in fact, consumer items of any type.34 Consumer items? Even if your average Briton could afford a new gadget or “consumer item,” Britain could only look, not have. For example, in 1946, people who were eager to see new designs and the new use of materials developed during the war applied to less belligerent ends queued for hours to get into the “Britain Can Make It” exhibit at the Victoria and Albert Museum. It was a sign of the times that most of the consumer items on display at the V & A were stamped “EXPORT ONLY,” so that the popular press quickly renamed the show “Britain Can’t Have It.” There were many stories in the press at the time about the day-to-day grind of having to face shortages of all kinds. The Christmases of 1945 and 1946, for example, were marred by the absences of anything very much to serve as presents.35

A Nation Turns Inward

23

Bare cupboards and empty stockings were to be Britain’s spoils of war; on top of that, 1946 and 1947 would be two of the coldest winters in British history.36 The renowned Annals historian Fernand Braudel has observed, “Towns are like electric transformers. They increase tension, accelerate the rhythm of exchange and constantly recharge human life.”37 If this is true, then life in London during and at the end of the war was intensified tenfold; and by the end of the decade, though the government was in better shape financially, average people in the street still did not feel it themselves. “What do you consider to be the main inconveniences of present day living conditions?” Mass-Observation asked its regular, largely middle-class panel in autumn 1948. The male replies tended toward terseness—Lack of Homes, Food Rationing, High Cost of Living, Insufficiency of Commodities causing Queueing, Crowded Travelling conditions, Expenses of Family Holidays’ was an engineer’s top six—but the female responses were more expansive. “1. High cost of living,” declared a housewife. “This means a constant struggle to keep the household going and there is very little left over for the ‘extras’ that make life.” 2. Cutting-off electric power in the morning (usually just before 8 o’clock). 3. Shortage of some foods, particularly butter, meat and sugar . . . [M-O next asked, “Had attitudes changed toward clothing, etc.?”] “Yes,” replied one jaundiced housewife. “I used to look upon ‘making do’ and renovating as a national duty and make a game of it. Now it is just a tiresome necessity.”38 The pictures of “miserable Britain” were implanted in minds around the world by these stark observations found in newspapers and magazines in the postwar years. But even more vividly, the postwar satirists also helped shape and cement those images with their barbed and sapient portraits.

The Art Scene The received wisdom of the late 1940s was that, after the “People’s War,” the landslide victory of the Labour Party in the General Election of 1945, and the establishment of a welfare state, a newly democratized British society was set to rid itself of inequalities and class divisions for good. But instead, without the common cause of winning the war, Britain

24

Ripping England!

reverted to the peacetime Darwinian class-based conflagrations, and in the arts, too, the growing other classes now demanded their fair share. Indeed the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts was created (albeit, voluntarily) in 1940 (which would become the permanent Arts Council by 1943, whose first chairman was John Maynard Keynes), and it brought various performers and musicians to factory towns during the war years to supply culture around the country. It was a big hit, and its budget grew every year, especially after its most successful sponsoring of Spanish paintings in the freezing, heat-starved winter of 1946–47 when thousands lined up to view the exhibition. And so, As Paul Addison wrote, “the temporary wartime bridge between the arts and the masses was in fact crumbling.” [It would no longer be temporary; art-going would become a permanent norm after the war]. Inevitably the arts based themselves after 1945 on a regular constituency of enthusiasts.39 Many budding Brits who grew up in the postwar period and benefitted from the 1944 Education Act felt that the old prewar upper classes still maintained their privileged position as they commanded the social and cultural high ground; these newly educated young strivers were determined to challenge that. The Arts Council helped level the field, but this is also where and why the postwar satirists would announce their own presence on the scene independently as they thrived on this contrast between the glittering pretense of mass culture and the shabby reality of a class-bound educational system. In the literary world, for example, Kingsley Amis, who did National Service in the peacetime army, gave his Lucky Jim protagonist Jim Dixon a university post at a time when provincial colleges were mostly third-rate Oxbridge wannabes. As David Lodge describes: In 1954 it was acclaimed as marking the arrival of a new literary generation, the writers of the 1950s, sometimes referred to as the “Movement” or “The Angry Young Men.” These were two distinct but overlapping categories. The Movement was a school of poetry, of which Philip Larkin was the acknowledged leader, and to which Amis himself belonged, along with other academics like John Wain, Donald Davie and D.J. Enright . . . They consciously set themselves to displace the declamatory, surrealistic, densely metaphorical poetry of Dylan Thomas and his associates with verse that was well-informed, comprehensible, dry, witty, colloquial and down-to-earth.40

A Nation Turns Inward

25

The Angry Young Men, a journalistic term originally coined in an article in The Spectator, grouped together a number of authors and/or their fictional heroes of the 1950s who were vigorously pissed off with life in contemporary Britain. They would include John Osborne/Jimmy Porter (Look Back in Anger, 1956; The Entertainer, 1957), Alan Sillitoe/ Arthur Seaton (Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, 1959; The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, 1959), John Braine/Joe Lampton (Room at the Top, 1957) and Kingsley Amis’s Jim Dixon.41 At the same time, as Lodge explains above, The Movement was less a school of poetry than a motley group of language-soaked exceptionally literate outsiders with like-minded sensibilities rebelling against posh posturings and “high language,” who sought to use street idioms and slang to replace the turgid old boys’ stodgy verbiage.42 For them (or in reality), it was an updating of Wordsworth’s romantic manifesto celebrating the more authentic language of the common man; but for postwar Britain, it was a highly charged conceit.

Figure 1.4. Kingsley Amis, c. 1950s. Anti-Establishment street-speaking snark. Photofest.

26

Ripping England!

Although these writers “arrived” in the mid- to late 1950s (Lucky Jim was published in 1954), their education and careers had begun in the late ’30s, but then had been inevitably interrupted or in some cases delayed by the war, making their formative years really the later ’40s. In Jim, though no dates are specifically mentioned in the text, Amis’s satire is clearly a novel about the late ’40s and the shadows of the war, and certainly cannot be set later than 1951 since a Labour government is still in power.43 The grounding of the novel itself, too, is clearly that of socialist, “austerity” Britain, “when a young university lecturer might plausibly possess only three pairs of trousers, live in a lodging house, surrendering his ration book to his landlady, not even dream of owning a car, and keep anxious count of his cigarette consumption, not on health grounds, but on financial ones.”44 John Osborne (1929–1994), Alan Sillitoe (1928–2010), and John Braine (1922–1986) had similar mid1950s publications with similar late-1940s contexts. This was Britain’s new Silent Generation artistic contribution.

The Silent Generation If good news was almost ubiquitous from the advancements of the Allied militaries from late 1942, right up until the end of the war (barring the blip of the Battle of the Bulge), after the initial high of the win, a psychological depression took over both Britain’s (even as the economic one continued) and America’s subcultures (where the economic one had ended): Churchill hollered about impermeable iron curtains; ominous atom bombs were detonated on remote atolls and Russian wastelands; and American (and British) commie hunters made daily headlines shouting their (often unfounded or unproven) accusations. The 1950s are thought of as such a wonderful prosperous time in both the United States and the United Kingdom (certainly Reagan and Thatcher would paint them that way), while the noirish late ’40s, filled with such hard times and incessant anxiety, so often get overlooked.45 This is unfortunate, for the arts were going through a great Renaissance in both republics. In the United States, even an artist such as Jackson Pollock was already doing his splatterings while the war was still being fought (he created Mural for Peggy Guggenheim in 1943, long before his move with Lee Kraisner to the Long Island Springs locale—a village adjacent to East Hampton—in November of 1945), with its mythical “epiphanic moments” about the magic wand of “the drip,” and was almost completely finished with his Zen-impulsed mizzles by 1951 (the same year the Ealing satires would be winding down, and the Goons

A Nation Turns Inward

27

just gearing up). The critic Manny Farber was already on to the jittery affect of Pollock’s painting, writing in The New Republic in 1945, “the paint is jabbed on, splattered, painted in lava-like thicknesses and textures, scrabbled, made to look like smoke, bleeding, fire, and painted in great sweeping continuous lines.”46 Action was the new generation’s word of the day—Action Painting, Action Writing, action, action, action at all costs, including for the government to take action and individuals to take action in their own lives. Just as the line and the brushstroke begged to be free, so too did the English language, and the new (Silent Generation) artists would attempt this for them. And in England the new satirists rose to the task, siring their greatest and most important work at the latter end of the shadowy 1940s. In the United Kingdom and the United States, the late 1940s are the great years for these satirical masterworks, not the 1950s Restoration of Churchill’s glorious return or the beaming war-hero Eisenhower’s vistas of 1950s television, Technicolor, Elvis, and Playboy magazine. The mid- to late 1940s was the more precise period that influenced and formed such amazing personalities who came of age at that moment, members of the cohort known as the Silent Generation (born somewhere between 1924 and 1943, give or take a year or two): in music with John Lennon (1940)/Paul McCartney (1942), Mick Jagger/Keith Richards (both 1943), Ray Davies (1944), and Jimmy Page (1944); letters with John Osborne (1929), Alan Sillitoe (1928), Philip Larkin (1922), Kingsley Amis (1922), and John Braine (1922); and the groundbreaking drollery of Spike Milligan (an honorary Silent, 1918), Peter Sellers (1925), and Tony Richardson (1928) in the UK. Meanwhile, a similar phenomenon was brewing in the States with the Silents of Miles Davis (1926), John Coltrane (1926), Elvis Presley (1934), the Everly Brothers (1937, ’39), and Bob Dylan (1941) in its popular music, and Lenny Bruce (1925), Mel Brooks (1926), Mort Sahl (1927), Mike Nichols (1931) and Elaine May (1932), Woody Allen (1935), George Carlin (1937), and Richard Pryor (1940) in the new radical comedy in the United States; along with the new generation of “angry” young English actors such as Albert Finney (1936), Vanessa (1937) and Lynn (1943) Redgrave, Malcolm McDowell (1943), and Alan Bates (1944), and the new American “Method” actors Montgomery Clift (1920), Marlon Brando (1924), Paul Newman (1925), Marilyn Monroe (1926), James Dean (1931), and Jack Nicholson (1937). In other words, those artists who gave the Silent Generation its not-sosilent voice. Generations are writ with “real-world-events,” narratives creating tropes and characteristics that lend themselves to studies in mass

28

Ripping England!

psychology and behavior. These Silents grew up being first conscious of the Great Depression, then the long traumatic years of World War II, the 1950s “culture of conformity,” the 1960s revolutionary tumult, and the 1970s malaise. In both America and Europe, many of their fathers fought in the war and, if they survived, often wanted to restart their lives anew—new education/new job (the GI Bill/the new European policy and promise of “full employment”), new wife/new house in the suburbs (1946 still holds the record for most divorces in American history/a rebuilt subsidized Western European welfare state)—almost to the point of ignoring those children born in the late 1920s to early 1940s, during the horrible years. In fact, many worked to forget them, as they wanted to forget the Depression, leaving heavy psychic scars. The arts, and especially the cinema, both mirrored the Silents’ lonely situation and provided a means of addressing it. Because of the postwar 1940s and ’50s Red Scare, the Silents in both the United Kingdom and the United States had to be secretively inventive in their protests, disguising their anger by speaking in code: painting abandoned representation for abstract expression; in acting they used their “Anger” and “Method,” turning inward to articulate these cultural frustrations; in theater, allegories were the strategy of choice (The Browning Version (1948); Separate Tables (1955); The Love of Four Colonels (1951); Crucible (1953); Streetcar (1947); Waterfront (1954—based on the “Crimes on the Waterfront” investigative journalist series from 1947 by Malcolm Johnson); music literally became silent (John Cage’s 4’33”) or wildly unwieldy—bebop, jazz solos, rock and roll scat (“Bebop a lulu”/“Womp-bomp-a-loom-op-a-womp-bam-boom!”) and British Skiffle; poetry and the novel spoke in tongues or hyperbolic run-on asymmetrical non-iambic verse; and criticism shifted inward, too, with the “close reading” and anti-contextual turn (from I.A. Richards and Charles Kay Ogden to F.R. Leavis and Cleanth Brooks). Much of this would have been absorbed by the other Silents who had also lived through these hardscrabble, harrowing experiences (most of the Ealing artists were too young to have fought in the war, and Spike Milligan, Harry Secombe, and Michael Bentine in the Goons were only slightly older than Sellers). The British (and American) Silents were definitely not so guarded, or so silent.47 Obviously, a key trait all these Silent artists have in common is a stubborn and fierce independence, but also a reaction to their late 1940s circumstances. Code, but also satire, became their wall of psychic defense. And so, for Amis, the original inspiration for his antipathy was a glimpse of what was then University College, Leicester, in 1948, when he was visiting Philip Larkin who was a librarian there:

A Nation Turns Inward

29

Jim is ill-at-ease and out of place in the university because he does not at heart subscribe to its social and cultural values, preferring pop music to Mozart, pubs to drawing rooms, non-academic company to academic. . . . When he loses his university job, however, Jim resignedly prepares to take up school teaching (at his own school), as if there were no alternative. A huge portion of the first generation humanities graduates in the 1940s and 50s went into educational careers not because they had a vocational call; but because entry to the other liberal professions—administrative civil service, the foreign service, law, publishing, etc.—was still controlled by the public-school-Oxbridge-old-boy network. They were the ideal readers of Lucky Jim.48 Much has been made of how these Angry Young Men and Movement poets critiqued and deconstructed British life under the new postwar realities of the Welfare State. But they were of the 1950s and it was years before, in the late ’40s, that the artists explored here, the satirists of Ealing and the Goons, had long been making their commentaries on new Britain, using the more immediately accessible, “hot” popular culture mediums of film, radio, and print.49 It may have been a bleak and terrible time, but the arts became a new addiction to this new generation, and in a population of just forty-six million, more than thirty million continually went to the pictures each week, newspaper competition and circulation increased threefold, and radios were always on in English homes.50 It was a thriving time for old media, and the satirists would conquer all three. Even in the fashion-world changes were happening head-spinningly fast. Indeed, it was the arrival in February of 1947 of Parisian swirling skirts with their “Renoirish curves and flounces . . . below waist and bustle which brought the phrases ‘Tizer’ and the ‘New Look’ into common usage in Britain,” as Harry Hopkins put it, even borrowing that title for his evocation of early postwar British life. At what was basically merely a return to traditional feminine lines was indeed a remarkable tribute to the grip which the puritan discipline of Austerity and Fair Shares had gained in our island life. The chorus of disapproval grew as it became known that the new fashion required thirty or forty metres of material, not to mention new corsets, still firmly classified by the Board of Trade as “luxury garments.” . . . The Government was rumoured to be considering legislating against the new skirt length.51

30

Ripping England!

But, some bureaucrats supported the New Look shift in attitude. In the meantime Sir Stafford Cripps, made an appeal for moderation, receiving emphatic support from Miss Mabel Ridealgh, MP for North Ilfords. “The New Look,” declared Miss Ridealgh, “was too reminiscent of the caged-bird attitude. I hope fashion dictators will realize the new outlook of women and give the death blow to any attempt at curtailing women’s freedom.”52 Needless to say, the shock of 1947 became the fashion of 1948, even if it had a suspiciously French tilt. This was just the moment the English satires were being forged, a genre requiring some clarification.

Satire and the New Film Setting In the arts, “genre” traditionally divides into various kinds or “types” (e.g., literature, film, music, painting, sculpture, performance, etc.) according to criteria particular to that form. Literary variations split between poetry and prose; poetry might thus branch off into epic, lyric, and dramatic, while prose might be cleaved into fiction and nonfiction. Obviously, these can be further partitioned ad libitum.53 Satire, then, is both a literary and/or artistic technique that attempts to ridicule its subject as a means of provoking change or preventing it. In either case, its ultimate goal is the same as rhetoric itself, to “persuade” its audience to a certain point of view by exposing the object of attention it is attacking as weak and irrational, or maybe even dangerously damaging to the health of the community at large. James Sutherland explains: What distinguishes the satirist from most other creative artists is the extent to which he is dependent on the agreement or approval of his readers. If he is to achieve this catharsis for himself, he must compel his readers to agree with him; he must “persuade” them to accept his judgment of good and bad, right and wrong; he must somehow inoculate them with his own virus. In actual practice, a minority of his readers probably already agree with him; the great majority are either quite indifferent and must be aroused, or they are actively hostile and must be converted.54 Satire is the most effective form of persuasion (no wonder the great British nineteenth-century satirist Jane Austen named her narrative study

A Nation Turns Inward

31

as such); it is the ultimate form of rhetoric. In Gilbert Highet’s comprehensive study of satire, The Anatomy of Satire, still the standard work, he describes the rhetorical devices that are used in this superior act of persuasion. Any author who often and powerfully uses any number of the typical weapons of satire—irony, paradox, antithesis, parody, colloquialism, anticlimax, topicality, obscenity, violence, vividness, exaggeration—is likely to be writing satire.55 Furthermore, Highet defines satire as “a playful distortion of the ‘familiar.’ ” Dr. Johnson, in the Dictionary, called it, “a poem in which wickedness or folly is censured.”56 In The Battle of the Books, Dryden followed Horace when he wrote, “Satire is to tell the truth, laughing,” while Pope in The Dunciad said it is to “Damn, with faint praise.” Bakhtin noted in The Dialogic Imagination that satire is the most democratic form of art/ literature because it is multivoiced, where everybody has agency.57 For Northrop Frye, satire differentiates itself from comedy by being a mythos of winter—as opposed to summer’s sweeter jesting (which is comedy’s seasonal mythos)—for its militant irony: “its moral norms are relatively clear, and it assumes standards against which the grotesque and absurd are measured. It is the mythical pattern of experience because it attempts to give form to the shifting ambiguities and complexities of unidealized existence.”58 What they’re all trying to lovingly, but maybe a bit overpedantically say is: rhetoricians love to study satire because it is the most powerful, and so, persuasive force of all literary genres. Satire differentiates itself from comedy in other ways, too. Though both expose and ridicule human folly, and both use similar rhetorical devices, the basic difference between comedy and satire is the difference between the optimist and the crank: comedy is social, it is uniting, and it usually ends in a wedding. But satire is lethal, it seeks to destroy, to burn away the rot of what it sees as the virus decaying society; thus, this often ends in the blowing up of the world so a newer, purer one may be born.59 Satire is disuniting and antisocial, and though a bit of an exaggeration, it is also often delivered by a lone screaming prophet-madman out to change the world and its ills. Satire came in a great variety of modes in the long eighteenth century. If Horace, Persius, and Juvenal were classical models, Rabelais and Cervantes were Renaissance models of burlesque in fiction, and Bacon and Hobbes Enlightenment models for a general satire of human knowledge. Later, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, British satire included the highbrow yet provincial novels of Austen, the

32

Ripping England!