Attlee 0297779931, 9780297779933

214 49 29MB

English Pages 630 [321] Year 1982

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Kenneth Harris

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

ATTLEE Kenneth ·Harris

W eidenfeld and Nicolson London

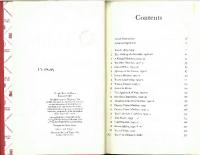

Contents

List of illustrations

vzz

Acknowledgements

zx

Youth, 1883-1905

I

2

The Making of a Socialist, 1906- 18

2I

3

A Rising Politician, 1919-22

4I

4

The New Member, 1922-4

5

Out of Office, 1925-30

57 69

6

Minister of the Crown, 1930-1

85

7 Labour Divides, 193 1-3

8

To the Leadership, 1933-5

93 III

9

Taking Charge, 1935-7

I23

10

Attlee At Home

I40

11

The Approach of War, 1937-9

12

Patriotic Opposition, 1939-40

I49 I66

13

Member of the War Cabinet, 1940-2

I79

14

Deputy Prime Minister, 1942

196

15

Deputy Prime Minister, 1943-4

208

16

The End of the Coalition, 1944-5

234

First published in Great Britain by George Weidenfeld and Nicolson Ltd 91 Clapham High Street London SW4

17

Into Power, 1945

255

18

Cold Warrior, 1945-9

Designed by Myles Dacre

19

Home Affairs, 1945-6

20

Year of Crisis, 194 7

332

(...2 1 The End of Empire: India

355

©

1982 Kenneth Harris Reprinted .1982

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Copyright owner.

ISBN 0

297 77993

I

Printed by Butler & Tanner Ltd Frome and London

~"

292

./

3I7

CONTENTS

388

22

The End of Empire: Palestine

23

A Man and a Leader, 1945.:..51

24

Consolidation or Advance? 1948-9

25

Struggling On, 1950

26

Downhill, 1951

442 468

27

Containing the Storm

495

28

Bevan or Gaitskell?

5 15

29

The Last Years

544

Epilogue

565

. /

•

Appendix I

Memorandum on British Industry, July 1930

Appendix II

Memorandum on British Military Failures, July 1942

Appendix III

The Reorganization of Government

Appendix IV

Attlee's Style of Government

Sources Index

Illustrations

401

419

570

Henry Attlee With his brothers Laurence and Tom Jn his first term at Northaw Place At Haileybury, aged 16 (BBC Hulton Picture Library) In his first term at University College, Oxford (BBC Hulton Picture Library ) With members of the Haileybury Boys' Club, Stepney (BBC Hulton Picture Library) With the staff of Toynbee Hall, Whitechapel Captain Attlee in 1915 Mayor Attlee of Stepney walking to Downing Street in 1920 (BBC Hulton Picture Library ) Attlee announces his engagement to Violet Millar (Barratfs Photo Press ) Under-Secretary of State for War, 1924 With the other members of the Simon Commission, 1928 Addressing a Labour Party rally in Hyde Park (BBC Hulton Picture Library) Attlee's brother Tom Vi The annual family holiday in North Wales, 1938 (Fox Photos) At home with the family, 1940 (BBC Hulton Picture Library) -At the Labour Party Conference, 1945 (BBC Hulton Picture Library) The Leader of the Opposition sets out for the Potsdam conference (BBC Hulton Picture Library) Victory in the 1945 General Election (BBC Hulton Picture Library ) With Ernest Bevin, en route for Potsdam (BBC Hulton Picture Library) Attlee and his Cabinet in 1945 (Barratt,s Photo Press) Attlee and Sir Stafford Cripps (Keystone Press; Labour Party Photograph Library, Attlee and Hugh Dalton (Labour Party Photograph Library) The Cabinet Room, 10 Downing Street Attlee visits his constituency during the 1950 General Election A warm greeting from President Truman (Labour Party Photograph Library) Aneurin Bevan, 1952 (Labour Party Photograph Library) · Sam Watson and Hugh Gaitskell, 1955 (Labour Party Photograph Library) Earl Attlee with his daughter, Lady Felicity Harwood (BBC Hulton Picture Library ) The Attlees with one of their grandchildren Attlee and Churchill in conversation (Camera Press; Labour Party Photograph Library) Attlee in 1966, the year before he died (photo by Jorge Lewinski)

Acknowledgements

I owe an outstanding debt of gratitude to my friend Oliver Coburn, who helped me to find material for this book, advised me how to use much of it, but, alas, did not live to see its completion. I must thank Lord Weidenfeld for his patience in waiting for this book to be delivered. His editorial colleagues Robert Baldock and Benjamin Buchan have been most helpful. I am also indebted to John Turner, Lecturer in History at Bedford College, University of London, for his assistance in editing down the lengthy original MS. Heather Adlam and Gloria May helped with res.earch and the organization of the documents. My considerable debt to the authors of books relating to Attlee or to the period is recorded in Sources at the back of the book.

1 Youth,

1883-1905 I

Jn 1883, the most destructive of the critics ·of capitalist society died and the most constructive of its critics was born. Marx died in March, Keynes was born injune. On 3Januaryofthe same year, in Putney, at 'Westcott', 18 Portinscale Road , the first British Labour prime minister to form a majority government came into the world: Clement Attlee. No bells rang, no portents blazed across the sky. There was no great excitement in Portinscale Road in a household which had already seen six babies into the world - this undersized little boy, the fourth son, would be the seventh child out of eight. Life at 'Westcott' went on much as usual that day, except for the mother, Ellen Attlee. The father, Henry Attlee, arrived at his solicitor's office in the City to begin his day's work at his accustomed hour. · The Attlee family had lived in Surrey for many generations, the name occurring in English medieval records in the twelfth, thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Since genealogy was a family hobby we know a good deal about them. Bernard, an elder brother, the family's amateur archivist, prepared table after table, tree after tree, so that the family papers are a forest of them. Clem took a hand in later life - in his seventies he carefully penned a set of trees on the back of a First World War officer's map which ran into five hundred items. The derivation of the name is probably 'At the Lee', becoming 'Att-Lee' - 'lee' or 'lea', an Anglo-Saxon term, meaning a clearing or a meadow. There is a Great Lee Wood at Effingham, a small village near Darking, Surrey, in pretty rolling wooded countryside just off the main road running southwest from London to Portsmouth, twenty miles as the crow flies from the Houses of Parliament. This was the original Attlee country. The Attlees believed they took their name from this wood, and that the family home was Lee House of the Manor ofLa Lee or La Leigh,just outside the village.

YOUTH

1883-1905

By 1722, when John Attlee, 'churchwarden', man of property and repute, was born, the Attlees had migrated every bit of four miles, southeast across the wooded hills from Effingham, and were well established as millers, merchants and farmers at Rose Hill, now on the southwestern perimeter of the town ofDorking. Clement Attlee's grandfather, Richard, born in 1795, was a very able man. Ifhe had inherited a good start in life, which is not at all certain, he certainly made the most ofit. There were ten children. Richard took two of the seven boys into the family corn mill, set up two as brewers, allowed the fifth to follow his bent and become a clergyman, and articled Henry, the future prime minister's father, to a firm of solicitors in the City of London called Druce's, with offices at IO Billiter Square, EC3. Henry, born in 1841, found himself at sixteen able to embark at his father's expense on a career which, if unexciting, combined the maximum of expectation with the minimum of risk. From then on he was expected to stand on his own two feet and prosper, and so he did. He became senior partner of his firm, he educated eight children and made them all financially independent at the age of twenty-one, and he rose to the top of his profession, becoming President of the Law Society in 1906. He earned every penny he spent, and died worth £70,000 in 1908. Henry Attlee was a hard worker. As they grew older his children felt he worked too hard. Every night after dinner he retired to his study and worked. His holiday was limited as though by statute to a fortnight in the year. The day he died at his desk of a heart attack, he had travelled up to London from Putney as he had travelled day in day out for just over half a century, slogging away with that amalgam of Christian sense of duty and respect for material success which was the ethos of the Victorian middle class. At his memorial service they sang his favourite hymn, 'Fight the Good Fight'. Henry was of middle height, very upright, with light-blue eyes that had fire in them. As a young man he was handsome, lean, with a fine head, strong chin with a slightly protruding lower jaw, Byronic brown hair, and a beard. In later life, as his hair thinned and his beard grew, he resembled a composite of Lord Salisbury and William Morris. His temperament was interesting, if only because Attlee inherited some of it. He was never cross - the children never saw him show ill temper - but this was much more due to self-control than natural equanimity. In a letter to his son Bernard, Henry says: 'You inherited from me a baddish temper but it seems to me you have quite conquered it.' Henry could never put his work aside for long, and he took it very seriously. When the children went up to bed they would hear him behind the closed door of his study arguing al~ud with himself the briefhe was to submit the following day.

There was anxiety in his personality - he fussed when there was a train to be caught - and he was self-critical. Henry Attlee was distinctly - some of his friends and relatives thought embarrassingly - interested in politics. Though his parents and family were loyal Conservatives, Henry Attlee was a committed Liberal. Gladstone was his idol. He was a Home-Ruler and a pro-Boer. Considering his times and his background, his views were radical. He did not proselytize, but he did not dissimulate. In his earlier years he canvassed for his old friend Bryce, later ambassador to Washington. ·Indeed, a moment came when Henry's friends thought he would stand for Parliament. His senior partner, old Druce, dissuaded him, by arguments of which we have no record. Thereafter Henry withdrew from the front line of the Liberal Party's battle, without ceasing to be active in supp9rt. His friend Haldane, later lord chancellor, interested him in education. Henry joined the governing bodies of several schools, including Hailey bury, where he later sent his sons. In 1870 Henry Attlee, then lodging in London, married Ellen Bravery Watson, the niece ofa miller who was one of his father's Darking friends. They were married at her family's church, St Anne's in Wandsworth, when he was twenty-eight and she was twenty-three. Ellen was an attractive woman. She was not beautiful but her face was strikingly warm and sensitive, with brown eyes which Clem inherited. Like Henry she had good carriage, and was a vigorous walker. She adored her husband, lived for her children, and was a most affectionate and perceptive mother. Like Henry she believed in discipline for children, but discipline inculcated through the desire to imitate good examples. Both were Christians by religion and philanthropists on . principle. Whereas Henry was a Liberal, Ellen was a Conservative. There was never any political discussion between Ellen and her husband, at any rate not in front of the children. She knew all about his controversial views, opinions different from those of nearly everybody they knew. She seemed to think it best to keep the conversation off these matters. When subjects like Home Rule for Ireland came up in Attlee's infancy, he remembered well, his mother changed the subject very quickly. Ellen had inherited a love of the arts and literature from her father. Thomas Watson had been born in Soho, where his father had a very successful medical practice. After tutoring for various prosperous families he took advantage of his private income to become secretary of the Art Union of London, which published reproductions of good pictures at moderate prices. His wife died in her thirties. Ellen was the eldest child, and the burden of bringing up the other five children fell on her. They lived at the Gables, on Wandsworth Common, a mile from Putney - a power-house stands on the site today. Her father was a most lovable man.

2

3

YOUTH

1883-1go5

Photographs of him show youthful dark eyes gleaming benevolently from under a fine white-haired brow. Watson was particularly interested in the 'modern' paintings of his time, and Ellen was reared a disciple of the Pre-Raphaelites. It was to give pleasure to Ellen that Henry Attlee bought so many paintings; to please himself he bought books, only a few of which he had time to read. When they married, Henry and Ellen decided to live somewhere near grandfather Watson. Putney was attractive, had easy access by train to London, and was less than a mile from Wandsworth. Only six miles from the centre of London, Putney was then almost a village, with few roads built up apart from the High Street, leading to the new stone bridge which spanned the Thames en route for London. There were market gardens between Putney and Wandsworth, which, though bigger than Putney, was also still a small country town, the green fields stretching almost up to the High Street. They made their first home there in Keswick Road, in a house which Henry renamed 'Westcott', after the name of the village in which the family mills were located. Later they moved to 18 Portinscale Road, off Keswick Road, only a few yards away. Henry also named this house 'Westcott'. The Attlees were very conscious of the family's associations. When Clement Attlee built his own house at Prestwood, near Great Missenden, he called it 'Westcott'. Henry's 'Westcott' was a large, ugly, comfortable house with a front gate and a short drive wide enough to admit 'carriages'. On the ground floor was a dining room, a drawing room, a study and a full-size billiard room. Upstairs there was a bathroom, a lavatory, a day nursery, used also as a schoolroom, a night nursery for the three small children, large bedrooms for the mother and father, for the two elder boys and for the two elder girls, a small bedroom and a spare room and a box room. Henry put down a tennis court. Apart from this he did little to add to the amenities of life as his fortunes progressed, nor was he inclined to spend money to increase his social status. He needed servants, and employed a cook, a housemaid and a parlour maid full time; the gardener and the governess came in daily. Throughout his life he never kept a carriage. When the weather was tolerable he walked to the station. When it was wet he hired a cab. Clem always gave the impression that his childhood was very happy, and very much spent in the bosom of the family. This was true of all his brothers and his sisters, but particularly of him. For some reason he was not allowed to go to school until he was nine. His other brothers began at private schools in Putney when they were much younger. Clem got his first lessons from his mother. He could have done much worse. She spoke French, some Italian, was extremely well read, played the piano and sang agreeably, painted watercolours, and knew a great deal about

design. Adoring her, Clem lapped up her culture with delight, and spent several childhood years being educated at home with his sisters. Henry Attlee did not care for boarding schools for girls, though when they got older he sent them all to finishing schools on the Continent. Attlee may have been kept at home because he had a lengthy illness, of which he had a shadowy recollection, chicken pox perhaps, from which he took a long time to recover. According to his younger brother Laurence, he was taught at home so long because he was undersized or because he was so painfully shy. As a boy, he was very conscious of his small physique, especially when Laurence, eighteen months younger, overtook him in height and weight. It was a rare case - the older brother wore the younger one's cast-off clothing. The little Clement grew up as something of a solitary in this brood of happy extroverts. When the rest of them were climbing trees or scaling walls he would lie reading on the. lawn or indoors on a sofa. Though shy in varying degrees, none of the other brothers or sisters was so afflicted as Attlee. In later life, he felt that their shyness was his beloved mother's fault. 'She was too essentially a family woman and had, I think, a certain jealousy of the family showing independence and seeking friends outside the circle. This attitude tended to make us self-conscious and shy.' The others certainly did not suffer from what his sister Mary recorded as his· 'violent fits of temper'. These were so serious that his mother had to train him out of them. 'She was so successful that, ifhe saw her coming, he would bury his head in a chair. This was known as "Clem 'pen ting", or in ordinary language, "Clem repenting". I have never seen my brother in a temper in his adult life. He is an extraordinarily quiet and controlle,d person and very, very discreet.' The remarkable Ellen seems to have developed one of the most effective assets of the prime minister to be, and to have provided most useful early training for a future leader of the Labour Party. The family day was regular. They rose at seven; family prayers with the servants present' at 7.30: the Lord's Prayer, a short lesson from the Bible lasting for five to ten minutes, a short prayer. Grace at the breakfast table, then unfettered chatter. Henry would not say a great deal - much of the time his face would be behind The Times. Ifit were a fine morning Clem might walk down to Putney station with him, Henry wearing frock coat and top hat, to catch the nine o'clock train to Fenchurch Street station. Lessons would begin after breakfast, starting with a session with the Bible. 'Ours was a deeply religious home,' recorded Mary; 'we all knew the Gospels and the Acts by heart.' This was not regarded as formal study but extracurricular, a labour oflove. They did the Gospels and the Acts in term time, the Psalms in the holidays. Each child had his or her own Bible, and would take it in turns to read a verse until the reading was complete.

4

5

YOUTH

After the Bible readings, the secular education of the future prime minister began. His mother's greatest love was poetry, and Clem followed her into Idylls of the King as a duckling its mother into water. For him poetry became a natural element. He learned it easily and recited it without inhibition. At five years old, he could spout short poems by Wordsworth and chunks of Tennyson. The lines 'My strength is as the strength often Because my heart is pure' were, when he was eighty-four, · the earliest he could remember learning. When he was a little older, he took lessons with his sisters' governesses. One of them was French. From her he learned to recite the Fables of La Fontaine with an admirable French accent, which, 'with other nonsense, was speedily knocked out of me when I went to school'. Another Attlee governess, Miss Hutchinson, had formerly been employed by Lord Randolph Churchill to instruct the young Winston. She had made it clear to the Attlees that educating Winston had had its problems. On one occasion at the Churchill home a maid had gone into a room to answer the bell, to be informed by the infant Winston: 'I rang. Take away Miss Hutchinson. She is very cross.' In the holidays, or on Saturdays, there was a Bible reading after breakfast, but no lessons. The children then went off to the garden to play cricket, to swing, to walk in the fields, or play hide-and-seek. In summer, there was hay-making in the fields behind the house. Their mother would have lunch with them, and afterwards, if it was fine, they would go for a walk, over to Kew perhaps - for strawberry teas - or across to Wandsworth, to grandfather Watson's. Ifit was wet Clem might take out his stamp collection. If he tired of stamps he went back to his books. The children would reassemble for the evening meal. Henry would be there; he would take a single glass of claret and encourage the children to talk. Then he would retire to the study. Afterwards the children would play draughts, make up verses, play paper games like 'consequences', all organized and supervised by the ever-present mother. Bedtime was 9.30, a liberal hour in those days for children under ten. It was indeed, considering the period, a very tolerant, permissive home; the little Attlees had more freedom than most children of Victorian families. They also had more self-discipline. Their neighbours said: 'The Attlee family was brought up not to waste a minute.' Boys and girls were taught to be careful of their clothes. The servants did not do any mending. Mother and girls mended the boys' clothes and darned their socks. They made their brothers' shirts for them when they went away to school, and their pyjamas for them when they went to Oxford . Though they sewed and stitched, the girls were not encouraged to think of themselves as seamstresses: Henry set them essays on subjects like 'How to Govern an Island'. They were expected to be as knowledgeable as their brothers and to be able to run a home as well.

6

1883 - 1905 Attlee's brother Laurence has admitted wryly that the childhood of the Attlees is a story almost too good to be true. None of the children got into scrapes. They did not fight. They did not steal the farmer's apples. The father and mother were never tense with one another. A cross word between them would have struck the children as inconceivable. They were as considerate to the servants as to their children. They did not gossip, they did not criticize their neighbours. They were a very selfsufficient family, an inward-looking group of outward-looking individuals. They rarely went out, because to be at home was more amusing. The tone was set by the ambition of the two elder boys, which was to grow up to be like their father, and of the three younger boys, which was to be like their elder brothers. Yet the home of these paragons was always full of laughter. There was no sabbatical silence on the walk across the common to Hinkson Vale Church on a Sunday morning. Only Clem seems to have had difficulty in adjusting himself to the Anglican ambience which pervaded 18 Portinscale Road. In his childhood it was not so much the Christianity but the church services that put him off. He could not, at his age, refuse to attend without upsetting the other members of the family. So, not in spirit, but in the flesh, he was always on church parade. Sitting bored in church, unable, under the eyes of the congregation, to use pencil or paper, he would survey the big west window, and in his mind disassemble and then reconstruct the patterns of its many-coloured glass, or plan routes by which he might climb from the floor to the roof. In the summer of l 892 Clement, at nine years of age, still undersized and now much smaller than his younger brother, was judged big enough to go away to school. Tom, his elder brother, was at Northaw Place, a preparatory school for thirty-five boys at Potters Bar, Hertfordshire, run by the Reverend F. J. Hall, an old friend of the Attlee family. Hall ran the school with an assistant, another clergyman, the Reverend F. Poland. Academically Northaw left something to be desired. Hall and Poland had two great interests: a moderate one in the Bible, and a fanatical one in cricket. To his own subject, . mathematics, Hall attached very little importance, and even less to Latin and Greek. Like many boys who had been at Northaw Place, Attlee left with a great knowledge of cricket statistics and a vast accumulation of names, dates and places to be found in the books of the Old Testament. He knew so much about the Old Testament at this time that he was assumed by those who knew no better to be 'religious-minded'. In an examination set by the bishop he passed top of the diocese, and there was talk of him possibly 'having a vocation'. The teaching may have been bad at Northaw, but the boys were extremely well looked after and all were very happy. Clem settled down well. Though he was still light and small for his age, he got his rugger

7

YOUTH

colours early. He was never much good at cricket - he described himself as 'a good field, nothing of a bowler and a most uncertain bat' - but provided a boy turned out for the game and subscribed to the doctrine of the straight bat, the Head and his assistant were not censorious about the number of runs he failed to score. Since nobody bothered him with Latin and Greek he could go on reading poetry and history. He thought in later life that he must have seemed a bit of a prig to other boys, but they gave no sign of thinking so. He blushed a good deal in those days, but nobody mocked at this, dismissing it lightly with: 'Now you've made him smoke.' Elder boys were encouraged to protect the younger ones. Sitting alone at tea on his first day, looking rather sorry for himself, he was observed by an older boy, Hilton Young, later Lord Kennet, and a Labour minister of health, who, seeing that Attlee had no jam for his bread, gave him some from his own pot. New boys were officially assigned to older boys who were to act as guardians to them. Attlee's first charge, at the age of thirteen, was a new boy aged nine, called Williamjowitt, 'nice, bright, clever little chap. Never gave me any trouble.' Fifty years later Jowitt became lord chancellor in the first postwar Labour government. In the beginning of the spring term of r 896, when he was thirteen, Attlee left Northaw and went to Haileybury College, founded by the East India Company to educate men for service to the Empire. Many old Haileyburians had done well in the Civil Service, but on the whole it had not been a particularly successful school, ·and at the time he went there it was short of pupils. The headmaster, Edward Lyttelton, later to become headmaster of Eton, dealt with the problem partly by reducing the fees, and partly by slowing down the rate at which boys passed through the school, with the result that the lower forms included a large proportion of sixteen- and seven teen-year-olds. Henry Attlee sent his sons to Haileybury partly because its fees were low, partly because Hall, the master of Northaw, had earlier on taught mathematics at Haileybury, and recommended it to him. Conditions there were spartan. Attlee wrote in his autobiographical notes:

whole bad ... no one was considered anything unless he was good at games ... Lyttelton, a great man in his way, was a hopeless headmaster.

There were only two baths for eight boys, the rest using zinc 'toe pans'. Our sanitary needs were supplied by three rows of earth closets .... Many of the · form rooms opened straight on to the quadrangle. In winter one was either frozen or roasted according to one's geographical position between the fire and the door. Forks and spoons were washed by being thrown in a large tub of hot water and stirred with a brush .... The general arrangements were very rough. Lower boys had to pig it in the form rooms or class rooms where there was no privacy and a good deal of opportunity for bullying. The food was extremely bad at first but improved later. It was disgustingly served. I can clearly remember thinking often that one of the blessings of leaving would be decent food properly served .... The teaching was on the

Lyttelton was in many ways a very liberal man. In the late nineties his school reflected the general climate of opinion in Britain, which was imperialistic and very anti-Boer. Lyttelton, however, was pro-Boer, and on this and other issues stood against the currents of emotion in his own school. In rgoo, when the news of the reliefofLadysmith came through, the school expected a half-holiday. To its disgust, Lyttelton - pro-Boer _ refused to grant it. The boys mutinied, cut their classes, and marched in procession through the nearby towns of Hertford and Ware. Though no devotee of corporal punishment, in an age when it was regarded as an integral part of the public school education, Lyttelton decided on this occasion to administer it. To cane the small boys he felt would be unfair - they had been misled by their seniors. To cane the upper school, on the other hand, with its large complement of prefects, might undermine the school's internal discipline. To ask masters to punish transgressions at which he suspected they had connived would be equally invidious. So the Canon took his coat off and thrashed the middle third of the school himself: seventy-two boys. 'A fine physical feat' was Attlee's judgement. 'And without doubt the proper thing to do.' An enthusiastic anti-Boer and imperialist, he was one of the seventy-two, 'but the Canon was tiring when he got to me .... It was just as well - he had a lovely wrist.' Attlee kept all his school reports. The last of them, written when he was eighteen, was the best. His housemaster's assessment of him was: 'He thinks about things and forms opinions - a very good thing .... I believe him a sound character and think he will do well in life. His chief fault is that he is very self-opinionated, so much so that he gives very scant consideration to the views of other people.' There was nothing spectacular about his schooldays. He got no house colours, he won no prizes. Haileybury did not bring him out. Games worship was at its height there in those days, and being still small in body, and not good at games, his 'inability to excel increased a natural diffidence'. His time at Haileybury 'was enjoyable on the whole though there were periods of black misery'. There was bullying, and being small he suffered his share ofit; but it was his incapacity, through size and shyness, to make a mark that made him feel frustrated. The one exception to his failures was the cadet corps. He was an outstandingly good cadet, and enjoyed it very much: the drill and discipline put his deficiencies at a discount, and like many lightweights he found the military routine an opportunity to equalize with bigger-bodied men. He left the school intellectually immature and underdeveloped. Though he was generally well read, he had not thought about what he had imbibed. He knew little of the social or

8

9

YOUTH

1883 - 1905

economic side of history, and of science he was completely ignorant. On the bottom of the Haileybury report were five divisions - Good, Moderate, No Complaint, Indifferent and Bad, with a space in each division for the headmaster to sign. For the whole time he was at Haileybury Attlee scored only 'No Complaint', except for the last term's report, in rgor, when he rose to a 'Moderate'. Attlee's only original thinking at Haileybury was about religion. He came to the conclusion that he did not believe in God. He fully shared his parents' sense of moral and social responsibility, with its emphasis on a high standard of duty towards the poor and sick; this feeling became, as it did for other Attlee children, the basis of his future socialism. But he could not share their fundamentalist belief that to question faith was a sin. He did not in consequence feel any sense ofrevolt; the subject simply bored him. He pondered the matter when the time came to be confirmed, and decided that: 'So far as I was concerned it was mumbo-jumbo. It worked for many of those I most liked and admired, so it was nothing to laugh at or asperse. But it meant nothing to me one way or the other.' At sixteen, long before he knew what the word meant, he became an agnostic. For the rest of his life his closest friends were Christians, and a large number of them were Anglican clergymen. But Attlee himself'could not take it'. He had no wish to disturb his parents, and to other people, he assumed, his opinion did not matter. So characteristically he went through the motions of being confirmed, and thenceforward did not give God or the Life Everlasting very much thought. At home by now he was regarded as much the most studious of the Attlee brothers. Laurence was impressed by the amount of voluntary reading he did at school - 'at least four books a week, good books, not thrillers or adventure stories' - and the enthusiasm with which he maintained this rate at home during the holidays. 'It wasn't so much the amount he read but the amount he could remember.' But Laurence's most significant recollection of him at the time was of his interest in politics. In spite of Ellen's resolution to prevent political arguments breaking out, there was much talk of politics in the Attlee household. The talk was of parliamentary politics rather than of major social and economic problems which might raise questions about the basis of society. The Attlee parents accepted society basically as they found it. They revered men like Wilberforce and Shaftesbury, were prepared for reforms, accepted the need for change, but trusted much in the inevitability of human progress. As Attlee put it: 'The capitalist system was as unquestioned as the social system. It was just there. It was not known under that name because one does not give a name to something of which one is unconscious.' Nor did the duty of succouring the poor entail liking, let alone admiring, the working classes. One of Attlee's earliest memories

was of walking with brothers and sisters on the rocks in the Isle of Wight. 'Look at those little kids walking on the rocks,' somebody shouted in a cockney accent, to which Bernard replied: 'Essence of vulgarity'; which, Attlee noted, 'we thought a very fine retort.' Patriotism was taken for granted. Even some of the pro-Boers were more concerned about England Jetting down her own standards than about what was being suffered by the Boers. At home, at Haileybury and at Oxford, Attlee breathed the same welcome air of!oyalty to, and pride in, Queen and Country. It was in his lungs, from the days of his first memory of the outside world - going out of the house on to the porch to hang up flags to celebrate the Queen's birthday. Henry Attlee was not averse to encouraging his children in political discussion, provided it took place within this unquestioned framework; so much so that, according to Mary, 'Our friends used to say that when the little Attlees went to a party, their first words were "Are you Oxford or Cambridge, Liberal or Conservative?"', the first question referring to the Boat Race, its juxtaposition with the second being some indication of the depth at which politics were being discussed. Clem's political education at this time consisted of the political cartoons in the family's collection of bound volumes of Punch. 'He would lie on a sofa and pore over it for hours while the rest of us were on bicycles or playing family cricket.' Laurence's other main recollection is of Clem's readiness to argue 'not merely to give you his own views but to take yours to pieces. He was really quite an argumentative boy, and most of all he liked to argue about politics. Not so much about policies, but about the personalities. He could be very cutting about them, and very funny.' Arguing about politics was his way of self-expression. 'It struck us all - it made him quite a character. And though he was. shy and tongue-tied with outsiders, he wasn't backward in coming forward within the family, the study and in class.' Perhaps he was finding a field in which his small size and shyness did not prevent him from excelling, and perhaps a sense of physical inadequacy gave a sharpness to his view and an edge to his tongue. Nevertheless, his shyness persisted. Ifhe and Laurence went out together, on a walking tour or a trip to the Hook, it was Laurence the junior brother who did the talking, took the tickets and booked the rooms. 'When we went into our hotel, and I went up to the desk to register, Clem hung back.'

IO

When the time came for him to go up to University College Oxford, O ctober rgor, he had a stroke of luck which so much enabled him cope with his shyness that he iooked back on his three years there among the happiest of his life. He spent his first year sharing 'digs' I I

in to as in

YOUTH

1883 - 1905

'The High', a few yards from the college, with 'Char' Bailey and another old Haileyburian, George Way. Charles Bailey had been his best friend at school, and it was because Char went to 'Univ' that Attlee decided to go there. He had plenty of other company. His elder brother Tom was in his third year at Corpus Christi College, and Bernard, who had recently been up at Merton, was now the vicar ofWolvercote, a mile or so away. The eldest brother, Robert, now in the family law firm, had left many friends at Oriel, with invitations to 'drop in on Clem'. Life was very enjoyable. His total bill for tuition, food and board came to about £roo a year, but his father had given him a comfortable allowance of £200 a year. In his second year he was moved into college. His rooms were in the right-hand corner of the first quadrangle, on the first floor of the staircase nearest to the Shelley memorial. Bailey had rooms immediately below him. 'I rather took advantage of Clem's good nature,' Bailey recorded.

Beerbohm's ,Zuleika Dobson, published in 1911, gives some impression, for all its fantasy, of how the undergraduates were treated, and behaved, as a class apart. Though he assumed in a desultory kind of way that he would follow his father and become a lawyer, he decided to read History. While, as Attlee says in his autobiography, he 'did not read for schools with any great assiduity', according to Charles Bailey he 'worked pretty hard', and 'would have got a first if he had not done so much miscellaneous reading'. He went on with his poetry and read widely in English literature. As his special period he took Italian History 1495-1512, for which he learned Italian. Only one of his tutors made any impact on him Ernest Barker. 'He made his history live because he cared about the people in it.' It was not Barker's Liberal views that impressed him but his attractions as a teacher. He liked his north-country accent, his good looks and his enthusiasm for his calling. . Attlee showed little sign of political interests at this time. He was very easygoing, 'quite prepared to take life comfortably and as it came'. He reacted emotionally only when 'those damned radicals' were praised. 'I remember being quite surprised when an East End person said what a good chap Will Crooks was, while I was quite shocked at an educated man expressing admiration for Keir Hardie.' He may have exaggerated when he said in his autobiography that at Oxford he adopted 'a common pose of cynicism', but spoke the truth when he said he 'gave no real thought to social problems'. Some of his friends at Oxford were already interested in settlements in the East End of London sponsored by the university. Alec Paterson, the future prison reformer, then a close Univ friend , held meetings for undergraduates. Clem went to several, listened politely but doodled sketches of other undergraduates, and worked out ways of climbing the chapel roof. His views on party politics if vague were right-wing Tory. The Liberals he regarded with contempt - 'waffling, unrealistic have-nots who did not understand the basic facts oflife'. Only the Tories were fit to govern. They understood men, they understood power. Power had come to fascinate him, largely through his study of the Renaissance. The Italian princes of the fifteenth century thrilled him. He was intrigued by their unsentimental view of human nature. Perhaps he also enjoyed their contrast with his father's political opinions, which he thought dangerously radical - when a North Welsh quarry-owner imposed a lockout in the course ofa dispute on wages, and Henry subscribed to a fund established to support the locked-out workers, young Attlee 'was shocked'. In fact, he 'had fallen under the spell of the Renaissance. I admired strong, ruthless rulers. I professed ultra-Tory opinions.' This did not incline him to join the University Conservative Club any more

I wasn't very well off. If I had people coming to lunch I used to send my scout up to pinch Clement's silver. He never minded. He breathed out loving kindness. He may have learned from me to be a little less shy. I thought him insignificant until I got to know him - terribly shy - when a blood came into the room he'd twitch with nervousness. But when you got to know him you realized his selflessness; and others came to know it, showed it, and Clem became less shy.

In his second year, Char was elected a member of Vincent's, a club for outstanding undergraduates, with a strong contingent of sportsmen. He went up to give the news to Clem: 'I didn't know I was so' popular.' Replied Clem: 'I always knew you were a "blood".' The friendship of this attractive, successful and much respected 'blood' might well have given Attlee confidence. His second year at Oxford was 'the happiest and most carefree of my life'. He lost some of his shyness. He found that 'athletic excellence was not necessary to becoming accepted' and that he now 'played games well enough to get exercise and amusement'. Nor was it necessary to be a brain. 'Excluding a few outsiders, everybody knew everybody.' No cliques, no rowing set or football set, or barriers between intellectuals and athletes - the categories overlapped. 'I knew practically everybody in college, most of them very well.' He was proud of being a member of Univ during a golden age. In Clem's first year, two out of the three presidents of the Union were Univ men, the college was Head of the River, and housed the captains of the university rugger and soccer teams. Its corporate spirit was high. His happy college life was lived in a most agreeable university setting. Oxford itself was then 'unspoilt'; the town, dominated by the university, existed to serve the university's needs. 12

nm JO

n:nu

YOUTH

1883-1905

than to join any of the religious or do-goading societies, some of which even the 'blood' Bailey patronized. Though he read a great deal in the Union he rarely went to hear debates; the thought of having to make a speech on the paper would have cost him a week's sleep. He did make one speech in a debate while up at Oxford, in the intimate, informal atmosphere of the college's debating society, controlling his shyness sufficiently to defend Protection against Free Trade. He found the Shakespeare Reading Society, which he helped to form, much more congenial. For the most part, Attlee's Oxford was a social interlude rather than an intellectual adventure. Tennis on the Univ or Corpus courts. Playing hockey for the college. Squash. Watching rugger or soccer, hands in pockets on the touchlines. Sitting back in a deckchair, watching cricket, hands clasped at the back of his neck, straw hat tilted forward on his brow, the brim almost resting on the bowl of his pipe, eyes half closed in the Oxford sun. Walks along the river to Wolvercote with brother Tom to see Bernard, back through Long Meadow. Games of billiards - 'the only game I was proficient at - I was brought up at the billiard table'. He got his half-blue for billiards, and when Univ beat BNC in the university championship, Clem won his only prize at school or Oxford - a billiard cue. Sailing on the river in winter, or punting up the Cherwell in the spring; rambling excursions to surrounding villages on Sunday afternoons. Tea with dons and local vicars. Books. In his last two terms he worked very hard indeed - eight hours a day he reckoned. As his final examinations approached in the June of 1904, Ernest Barker told him he might get a first. He got a second. 'I was quite content.' If he had got a first, he would have stayed up, and tried to become a Fellow of some college. 'I've no regrets, but in fact it's been the second-best thing,' he said in his old age. 'If I could have chosen to be anything in those days I'd have become a Fellow of Univ'. Now that it had come to choosing a career, 'my general idea was to find some way of earning my living which would enable me to follow the kind of literary and historical subjects which interested me.' He chose the Bar. Towards the end of his time at Oxford he had become interested in politics, not as a process so much as a spectacle, as theatre rather than the struggle for power. If somehow he could acclimatize himself to speaking in public, the Bar would give him argumentation to his heart's content, and once established at the Bar, he says in his autobiography, 'there was a possibility of entering politics, for which I had a sneaking affection'. Ifhe had had one eye on emulating Ernest Barker, he now had half an eye on F.E. Smith. So, the future prime minister came down from Oxford not very different from the schoolboy who had gone up three years before. He came down with much the same interests as those with which he had gone up,

more knowledge, a half-blue at billiards, a passion for pipe-smoking, and many friends. He had discovered what scholarship and the life of the mind was about. He had met a number of men who he believed were 'good'. He left Oxford 'with an abiding love for the city and the University and especially for my own College'. The small circle of the Oxford men who knew him would have endorsed the report of his Haileybury form master - 'A sound character and should do well in life.' Pressed, they might have doubted if he "would do as well in life as his father. Outside that small circle nobody had noticed him. One of his tutors, Johnson of All Souls, wrote a brief general reference for him: 'He is a level-headed, industrious, dependable man with no brilliance of style or literary gifts but with excellent sound judgement.'

II

In the autumn of 1904, at the age of twenty-one, Attlee entered the Lincoln's Inn chambers of Sir Philip Gregory, one of the leading conveyancing counsel of the day, with a high reputation as a teacher. Gregory made his pupils work. He was soon pleased with Attlee. He found him 'very intelligent and industrious ... promise of considerable ability'. Attlee was not so pleased with Gregory - 'Task master - drove you to death'. Gregory, a master of the art of drafting documents, believed in putting his pupils mercilessly through this particular mill. In after life Attlee was grateful to him for this mental discipline, a corrective after the discursive treatment he had found encouraged by the Oxford History School. The skill in reading and drafting quickly which Gregory taught him 'came in very useful later'. At the time, he responded gamely to the pressure and passed his Bar examinations well by the following summer. His father, pleased with this beginning, took him into the family business, now Druces and Attlee, to 'derive from a spell in our firm a comprehensive knowledge of what happens at the solicitor's end of the Bar'. Henry so far succeeded that his son made up his mind after four months with Druces and Attlee that the solicitor's end of the Bar was not for him. What conservatism there was in Henry's temperament expressed itself in the appearance and organization of his office. There were files, but no filing system: when documents were required, it was the function of the clerk, the ingenious but much harassed Mr Powell, to produce them, relying on his powers of recollection to decide where the papers had last been seen. There were no typewriters: Henry thought they corrupted good handwriting. There was a telephone, but it was to be used only for the making of appointments, or in case of fire. The rooms were dingy, dark and dusty. Young Attlee's assignment was to sit at a

YOUTH

r883-r905

small table and take notes while the partners interviewed their clients. This made him 'feel self-conscious and foolish. And terribly bored. I spent much of the time doodling - mostly dragons, breathing fire and smoke.' At the beginning of rgo6, he 'transferred at my own request' and was sent as a pupil to Theobald Mathew. Mathew, a friend of Attlee's father, was a remarkable man, already an outstandingly good barrister and an authority on the Commercial Court. He kept his legal work within carefully chosen limits; he never took silk, and arranged his affairs so that he had time to wine, dine, write and become one of the great wits of his generation. Attlee found Mathew's chambers most congenial. He was very taken with Mathew's wit, which mocked the pompous and de~ bunked the great, but was utterly free of malice. In March rgo6 he was called to the Bar. His career thereat lasted less than three years. He had appeared in court on only four occasions, once at Maidstone and three times in London. He had earned about fifty pounds. When he came down from Oxford in r904, he continued to receive the annual allowance his father made him when he was at Univ: £200 a year. Like the eldest son, Robert, now a solicitor in the family business, and Tom, studying to be an architect, he lived at his parents' home. The tedium of the Bar apart, he seemed to find post-Oxford life comparatively agreeable. 'When my brother came down from Oxford,' recorded Mary, 'he became something of a man about town. He was passably good,looking, paid attention to his clothes, and enjoyed theatres and town life.' He lived the life ofa gentleman, and a gentleman, in his view, was what he was and should continue to be. He took his claret glass to his lips the long way, and set it down the shortest, and always spared a second or two to appreciate the bouquet. Sometimes he whiled away part of the morning by going some way to the City on foot. Sometimes, in the spring and early summer, he walked the whole seven miles from Portinscale Road to Billiter Square. Occasionally on a warm day in high summer he travelled to his briefless chambers by pleasure steamer from Putney to the Temple. There were congenial outlets for unused mental energy. On Wednesdays there would be a jolly lunch with a group of Tom's friends from Corpus, who had formed a discussion club which met at the Cottage Tea Rooms in the Strand. There was the Hazlitt Essay Club which invited poets and writers on the way to fame to read and talk about their work. In the evenings there were institutions like the Crosskeys, a literary club at Putney, which met for discussions, readings and debates. There were frequent trips to the continent with his parents or his parents' friends. Now and again he would go on a walking tour with one or another of his brothers. For several weekends he took out the expensive gun which his father had bought him and went down to the shoot which Henry shared

with friends in Sussex, until he found that shooting bored him. He learned to ride a horse - he came to ride quite well - and was on the point of buying a hack when he discovered that riding bored him too. Billiards fascinated him. When he returned home early from an empty day in chambers, he went straight to the billiard room, and potted patiently on his own, steadily improving at 'the only game in which I have shown any proficiency'.

r6

r7

In October r905, a year after leaving Oxford, 'an event occurred which was destined to alter the whole course of my life'. His brother Laurence decided to pay a visit to the Haileybury Club in Stepney, and asked Clem to go with him. He decided he would go. He owed the club a visit _ indeed he should have visited it before. He owed to his family and his Alma Mater, if not a genuflection, a respectful nod in that direction. Their mother was now a district visitor in one of the worst slums in London. An aunt was managing a club for factory girls in Wandsworth. Robert was working two nights a week at a mission in Homsey. Tom was helping at a working men's hostel in Haxton. Attlee decided he would go and look the place over and see, as he drily put it fifty years later, 'if the angels were wasting our parents' hard-earned money'. Stepney, in dockland, was reputed to be the roughest and least lawabiding borough in London. The Hailey bury Club was in Durham Road. Whereas some of the East End clubs had been established on a religious basis, Haileybury House, in spite of its physical proximity to Stepney Church, and the Christian convictions of most ofits Haileyburian helpers, was a secular institution. In essence, it was for the poor boys what the public school's Officer Training Corps was for the rich. Notwithstanding the avowed military character of its organization, the club's objects were social and educational. It, and similar clubs founded by other schools, aimed to give London boys that side of school life which education by the state did not provide. The motto of the Club was the Haileybury motto: Sursum Corda . . The Haileybury Club was 'D' Company of the rst Cadet Battalion of the Queen's (Royal West Surrey) Regiment. Membership of the club, for London working boys of from fourteen to eighteen years of age, was on condition ofjoining this junior section of the Territorial Army; the adults running the club took Volunteer Commissions in the TA, and acted as company officers. There was always a waiting list; very few boys left until they were forced to do so by the age limit. The club was open five nights a week. Wearing uniform gave these ragged boys a pride in their appearance which they had never previously been able to enjoy. The discipline braced them, the team work gave them a sense of belonging. It was the dread of having to give this up through the ultimate sanction of expulsion

um .iC fl 3HJ

ERSITI NGHM

urn Lu 113HJ

YOUTH

1883-1905

which was the basis of the club's discipline. Boxing, gymnastics, shooting, single-stick, swimming, the week's camp in the summer at the seaside improved their health. Many boys left the club to join the Regular Army. The manager of the club, Cecil Nussey, a fine scholar and outstanding athlete, made his mark with Attlee, who left that night in a thoughtful mood. He liked the look of the lively but earnest lads whose lives, according to Nussey, were being transformed by the fellowship of the club. 'Good show, that,' he said. 'Might look in from time to time.' From then he went every week. Five months later he took a commission as an officer of 'D' Company - second lieutenant. He was now committed to a share in the responsibility of running the club, and to be on parade at least once a week. What began as duty became a pleasure. 'I had always been painfully shy,' he wrote, 'and it took me some time to settle down, but East London boys are very friendly." He enjoyed the club's activities: the drilling on spring evenings in the gardens of the rector of Stepney, going into barracks at Kingston for a few days at Easter and Whitsun - and marching down there over Wimbledon Common singing lustily; summer Saturday nights in bell tents, in a field lent by the rector ofChislehurst; the August camp at Rottingdean. It gave him the security in which he could unbend. His daily work had not been giving him satisfaction, had been diminishing his small stock of self-confidence. Now he had a sense of purpose. He began to sense that the boys liked and respected him. He was complimented on his efficiency. His parents were pleased that their son was doing something voluntary and useful. He felt a filial satisfaction in moving in the family tradition of social service. · Eighteen months after Attlee became an officer of the club, Nussey asked Attlee ifhe would take over as manager. Attlee felt apprehensive, but when Nussey insisted on the difficulty the club would be in if Attlee refused, he agreed to carry on until somebody else could be found. This meant living on the club premises. He and his family assumed that he would stay there for a year or so at the most, and, having done a stint of duty long enough to be consistent with the social obligation of an Old Haileyburian and a young Attlee, resign and return. In fact, he left home for good, to live seven years at the club, for fourteen years in the East End. . The Haileybury Club manager drew 'a salary of fifty pounds a .year. He was a Stepney resident: he encountered not only the boys who came to the club, but the boys who did not. He met their parents, visited their homes, saw how the poor lived. The effect on the erstwhile young Tory Imperialist was profound. In his first year, the inexperienced Attlee had to cope virtually single-handed, since there was a shortage of Old Haileyburian help. Attlee, however, was already displaying his gift for estab-

lishing discipline. In his first annual report he noted briskly: 'There has been a marked improvement, a few expulsions having a salutary effect.' But his reports are more interesting for what they record of his first vision of how poor, uneducated, uncultured boys, given half a chance, would give, not take, in fellowship:

18

A word of praise is due to those boys who give up their time to helping the smaller ones; it is no small sacrifice for a boy who has worked from six in the morning to six at night to hurry his tea and come to the Club to look after and instruct small boys ... [and] there is no doubt that the small boy, though very amusing, is also exceedingly irritating .... I have been particularly struck by the many instances of unselfishness shown by the [elder] boys; for instance, a corporal of the Band, which at that time contained so many seniors that promotion was blocked, offered to resign his muchcoveted stripes in order to give another boy who had been working well a chance of promotion ... I remember taking the Club's football t~am by local train to play an 'away' match. Young Ben had come straight from work with his week's money - a half-sovereign - and somehow he had lost the gold coin. There was no hesitation amongst the boys. Jack said, 'Look, a tanner each all round will make 'alfofit.' They readily agreed, yet probably that 'tanner' was all that most of them would have retained for themselves from their wages.

As it turned out, there was no need for their sacrifice. Attlee assured them that if they searched the railway compartment thoroughly they would find the lost half-sovereign. They searched, and found it: he had slipped it behind a cushion when none of them was looking. Such opinions about loyalty, unselfishness and a sense of duty within a group influenced his conduct in his later life. As party leader he expected politicians to behave at least as well as the lads of the Haileybury Club; and if they did not he believed in 'a few expulsions having a salutary effect'. His annual reports on the activities of the club are curious reading. At times he makes the club sound more like a TA Headquarters than a YMCA. True, there is always a brief commendation of the loyal Miss Elliott who 'has continued to hold her voluntary class in the elements of religion on Monday nights'. But the tone of the reports is essentially military: The New Year brings with it several changes of personnel: HTH Bond has been appointed Adjutant to the Battalion, and his new duties will necessarily prevent his assisting in the work of the Company and the Club. Three years ago we were able to get a Haileyburian to take on a Company that was in danger of dissolution, and now, once more, it is a Haileyburian that helps the Battalion in its time of need.

The most interesting feature of his annual reports, however, is the light they throw on his progress towards socialism. Some of his predecessors

19

YOUTH

11111 .:I fl 31l

were content to try to alleviate effects rather than come to grips with causes. But Attlee, his natural impatience and realism mobilized against the laissez-faire and sentimentality of his father's generation, wanted not relief but reform. In his first report he analysed the particular social evil which faced the managers of East End boys' clubs - 'The abuse of boy labour and the consequent waste of good material, that is always going on in our great cities.' It was not enough for the managers of the club to point out the evils. As 'keepers of the School's conscience [theyJ should try to point out the underlying causes and possible preventions ... ' He begins with a description of the abuses of casual labour similar to one by Nussey three years earlier, but whereas Nussey had simply described the evils, Attlee went much further, and took to task a committee, of which Nussey had been a member, for publishing a report which 'revealed an extraordinary failure to realize that anything beyond sympathy was necessary to cope with these problems': Now it is very easy to be sentimental over hard cases, and it is possible to do something to assist individuals, but it appears to me that we want a great deal more than sentiment and individual charity: we want knowledge and we want thought. There is plenty of excellent feeling on such subjects as boy labour, sweating and infant mortality; but as there is far too little consideration as to the causes of, and the connection between these phenomena . . . '

Within a few months of taking up residence, he had seen the light: 'From this it was only a step to examining the whole basis of our social and economic system. I soon began to realize the curse of casual labour. I got to know what slum landlords, and sweating, meant. I understood why the Poor Law was so hated. I learned also why there were rebels.' · ·The slums, the suffering, the poverty were not the necessary consequence of the character of the poor. Given opportunities even remotely comparable to those of the boys who went to Haileybury, the Limehouse lads respond~d. Most of the poor were poor because they were being exploited by the nch. The message for the well-to-do should not be just 'help the poor who are always with us' but 'get off the people's backs'. By the time Attlee had written that report for the Haileybury Council he had become a socialist.

20

2 The Making of a Socialist, 1906-18

I

At the weekends Attlee went home to Putney. So did Tom, his favourite brother and mentor, now also living five nights a week in the East End. Tom was a deeply convinced Christian, and he had been strongly influenced by the social and political ideas of the Reverend F. D. Maurice, the Christian Socialist. Tom worked at the Maurice Hostel in Roxton. At these weekends during his first few months as manager of the Hailey bury Club, Attlee spent much time with Tom, the talk in the early weeks being not about political ideology but on mundane matters, such as drains. Attlee was anxious to do well at the club, but was very conscious of his lack of practical knowledge. Tom, on the other hand, was very practical. He knew all about bricks and mortar, roofs, windows and rising damp. When Attlee decided that Haileybury House needed more fresh air, Tom drew up the plans for a new ventilation system and superintended its i?stallation. Talk moved from how to repair the dub-house to the question of how to reform society. By this time Tom had become a great reader of Ruskin and Morris, finding in them an amalgam of those ar.tistic, religious and political ideas which were germinating in his own mmd. What he found he imparted to his brother. Hours of Sunday talk on the banks of the Thames at Putney, and frequent late-night discussion over their pipes under the sooty eaves ofHoxton, made another convert. Attlee started to read. Soon 'I too admired those great men, and came to understand their social gospel.' The conversion of Attlee from a middle~class, rather unreflecting Conservative into a dedicated socialist politician owed much to his brother Tom and the books to which Tom introduced him, and later, much to the Stepney branch of the Independent Labour Party. The F. D. Maurice who had so much inspired Tom advocated radical social change based on the application of Christian principles to secular 21

THE MAKING OF A SOCIALIST

rgo6 - r8

life, accepting the term 'Christian Socialism' as necessary 'to commit us to the conflict which we must engage in sooner or later with the un-social Christians and the un-Christian socialists'. He rejected secular socialism and state collectivism, and made his starting point the responsibility of the individual. Rather than aiming to introduce new forms of social organization he called on employer and public, as individual Christian believers, to transform the status and treatment of the worker. To understand Attlee's socialism, however, one must begin with Carlyle. His study of Chartism published in I 839 thundered out the warning that 'if something be not done, something will do itself one day, and in a fashion that will please nobody.' England's disgrace was the unbearable life of the poor: 'The sum of their wretchedness merited and unmerited welters, huge, dark and baleful, like a sunken Hell, visible there in the statistics of Gin.' Carlyle offered little by way of a practical programme, but Attlee responded readily to his call that men should rise to their responsibilities, act, and not speculate, do, and not talk. He was struck by the directness with which Carlyle addressed himself to the middle class, implying that only an enlightened, dynamic middle-class minority could make the first bold swerve off the headlong path which led to the abyss. Above all, Attlee responded to Carlyle's indignation, what Chesterton called his 'divine disgust'. But it was Ruskin, through Unto This Last, who did more than anyone to lay the foundations of Attlee's socialism: 'it was through this gate I entered the Socialist fold.' Ruskin had achieved a vast influence as an art critic when, then in his early forties, he published in I853 in the second volume of his Stones of Venice a chapter entitled 'On the Nature of Gothic Architecture; and herein one of the true functions of the workman is art'. In this he extolled those architectural styles which were most compatible with the welfare of the workman, praising the Gothic and condemning the art of the Renaissance. If this was odd as· architectural criticism, it was nevertheless an intoxicating social commentary. Ruskin insisted that society must be rescued from the economic ideas of the commercial middle classes, so that the lot of the working classes could be improved: 'Government and co-operation are in all things the L.aws of Life; anarchy and competition the Laws of Death.' Ruskin venerated Carlyle as his master, but improved on his master's work by offering at least something of a practical programme. In the preface to Unto This Last, published in I862, he made four proposals. There should be 'training schools for youth established, at Government cost, and under Government discipline'. There should be 'also entirely under Government regulation, manufacturies and workshops for the production and sale of every necessary oflife, and for the exercise of every useful art. And that, interfering no whit with private enterprise, nor

setting any restraints of tax on private tr;ade, but leaving both to do their best, and beat the Government if they could.' Thirdly, 'those who fell out of employment should be re-trained at the nearest Government school, and if unemployable ... be looked after at the State's expense.' Ruskin's fourth proposal was that 'for the old and the destitute, comfort and home should be provided .... H ought to be quite as natural and straightforward a matter for a labourer to take his pension from his parish, because he has deserved well of his parish, as for a man in higher rank to take his pension from his country, because he has deserved well of his country.' Ruskin foresaw not a socialist but a welfare state. Ruskin's disciple, William Morris, was the third formative influence on Attlee's socialism. Morris's contribution was to see that the social problem - poverty - and the aesthetic problem - desiccation - had been created by the same force, the Industrial Revolution. This had released forces of greed, cruelty and selfishness which had rendered society ugly in aspect and materialistic in outlook. Art, being an expression of everyday life, was creative only where everyday life was creative, and everyday life could not be creative for the community when many of the people who lived in it had not enough to eat. The first step therefore was to re-humanize everyday life, warped and corrupted by the Industrial Revolution, and restore it to health in a reconstructed society. In his analysis of the consequences of industrialization, Morris had much in common with Marx; and in the early I88os, when he reached his conclusions, he saw the Social Democratic Federation, a league of London working men's clubs with a distinct Marxist tendency, as the best instrument of great social change. He joined the Federation in 1883, but left it the next year to help found the Socialist League, whose journal, Commonweal, he founded, financed and managed. He preached revolution, and was arrested in I885 at a revolutionary meeting in the East End, though in later life he preferred to believe that the road to socialism lay not through revolt but through the education of public opinion. It is not easy to reconcile the aesthetic and the Marxist sides of Morris's socialism. Attlee studied enthusiastically How We Live and Might Live, A Factory as it Might Be, and Useful Work and Useless Toil; but in later life he remembered the Utopian studies News From Nowhere and A Dream of John Ball as his favourite books. News From Nowhere expresses Morris's yearnings for a life that was simple, clean and colourful. For many of the chapters the Narrator sculls leisurely for miles along the sunny upper reaches of the Thames, accompanied by the beautiful Ellen, 'light-haired and grey-eyed, but with her face and hands and bare feet turned quite brown with the sun'. There are salmon in the Thames. Flowers abound.

22

nm ..i "' 1 31'

THE MAKING OF A SOCIALIST

1906-18

There is no sound of engines, no smell of oil, no dust. It is a land of'work which is pleasure and pleasure which is work'. So read, and re-read, Attlee. And as he raised his eyes and looked out of his little bedroom in the Haileybury Club on to the sooty slates of the slums of Stepney, he pondered the message in Ellen's sad last parting look toward the dreamer as he turned back into the past:

they knew little about the ILP, which they thought was the preserve of the working class; they knew the Fabian Society was middle class like themselves. So in early October l 907 they went to the Fabian Society headquarters in the Strand, and applied to join. They attended their first Fabian meeting a few days later. 'The platform seemed to be full of bearded men. Aylmer Maude, William Saunders, Sidney Webb and Bernard Shaw. I said to my brother, "Have we got to grow a beard to join this show?" ' The Fabians were not all bearded. H. G. Wells was there, 'speaking with a little piping voice, he was very unimpressive'. Shaw and Webb got higher marks; the former 'confident and deadly in argument; Webb, lucidly explanatory'. He was not quite sure what to make of them. 'My impression was a blurred one of many bearded men talking and roaring with laughter.' But he was now committed. 'In two years the rather cynical Conservative had been converted into an unashamed enthusiast for the cause of Socialism.' The Fabians provided Attlee with the bridge by which he crossed to socialism. No sooner was he on the other side than he began to feel uncomfortable. It was not that the Fabians had taken him too far but because they would not take him far enough. The society had been founded in 1884 by Beatrice and Sidney Webb, Graham Wallas, Bernard Shaw and other young middle-class intellectuals. Its original intention was not to create a new politicial party but to permeate the Tory and the Liberal parties and persuade them to carry out reforms which would lead to the evolution of a socialist state whose main feature would be the collective control of the economic forces of society, 'in accordance with the highest moral possibilities'. Attlee had been drawn to it by the Webbs' explicit sympathy with the aesthetic origins of socialism, and by the Fabians' emphasis on practical measures ofimprovement, 'gas and water socialism'. But once a Fabian, he found that though his new colleagues wanted to give the working man a society fit to live in, they did not consider that he could provide the leadership to produce it. This patronizing attitude offended him. Life in Stepney had already convinced him that given the chance the working class would be fit to govern, and moreover that it had virtues and values which were in some respects superior to those of the middle-class Fabians. The alternative for a non-trade unionist in the Labour Party was the Independent Labour Party. This body had been founded in 1893 in Bradford, extending its influence rapidly in industrial centres. Its leading figure was Keir Hardie, a Scottish collier who had taken a prominent place in the 'new unionism' of the l 88os which for the first time enlisted unskilled workers in trade unions in large numbers. A Liberal until l 887, Hardie had decided that in the interests of the working class the trade unions must break from the Liberals and put into Parliament Labour

Go back and be happier for having seen us, for having added a little hope to your struggle. Go on living while you may, striving, with whatever pain and labour needs must be, to build up little by little the new day of fellowship, and rest, and happiness.

His favourite passage, though, came from A Dream

of John Ball:

Forsooth, brothers. Fellowship is heaven and lack of fellowship is hell: fellowship is life, and lack of it is death: and the deeds ye do upon the earth, it is for fellowship's sake that ye do them.

Morris was above all an artist. He saw life in aesthetic terms, of beauty and ugliness. Mankind should seek what was beautiful, in art, in nature and in human relationships. The ideal society was one in which everything that was made was 'a joy to the maker and the user' and in which all men could enjoy life at work as well as at leisure. A society in which ill-fed, ill-housed men joylessly manufactured ill-conceived, ill-designed commodities, to be sold to indiscriminating consumers for the profit of some tasteless tycoon, was a society at death's door. The aestheticism and fellowship which Morris preached were essential to Attlee's conversion to socialism. II

EllSIT

GU.'

Within a year of starting work at Haileybury House the Attlee brothers had come to the conclusion that individual action was not enough. They must act politically. Which was the party to join? Certainly not the Conservative Party: it was the Conservatives who owned the Stepney slums and exploited its casual labour. It was the Tories who brewed the beer which drugged and demoralized the working man and perpetuated the system which dragged him down. The Liberal Party was equally repugnant. It stood for the laissez-faire of the landlords, industrialists and businessmen, against whom Carlyle, Ruskin and Morris had inveighed. This left the Labour Party, which had been formed in I goo as the Labour Representation Committee, a coalition of groups to get 'Labour' representatives elected to Parliament. To join it, one had to become a member of one of the participating organizations: a trade union, the Fabian Society, or the Independent Labour Party. The Attlees were not members ofa trade union and did not consider themselves eligible for membership;

THE MAKING OF A SOCIALIST

I906 - I8

representatives to bring about the emancipation of the worker by a socialist programme, beginning with the nationalization of the railways and the banks. The ILP was distinctive in i:he coalition known as the Labour Party. Unlike the majority of trade unions, it was avowedly socialist; unlike the Fabians, it was boldly committed to the moral leadership of the working class. Early in January I908 Attlee was discussing the shortcomings of the Charity Organization Society with an East End wharf-keeper, Tommy Williams, who had described how the cos had refused to help the parents of a boy in the Haileybury Club. 'They believe in charity,' said Williams, 'but I am a Socialist.' 'I don't believe in the cos either,' Attlee replied. 'I am a Socialist.' 'If you're a Socialist, join the ILP,' said Williams. Attlee went to the next meeting of the Stepney ILP and joined. Sitting round a stove in a small, grim East London church hall, with a dozen working men, he suddenly, and for the first time, felt in his element. ' I knew at once this was the right show for me.' Attlee did not become a martyr when he joined the ILP, but he 'occasioned a certain amount of comment' among family and friends. To , become a Fabian was one thing: to join the party of the militant working class was another. His mother heard the news with good-natured resignation. Henry outwardly remained his tolerant self, but, he confided in Laurence, 'I wish I were a younger man. I'd argue it out with him, and knock all that nonsense out of his head.' Attlee was acutely aware of his parents' real feelings. Years later, in The Labour Party in Perspective, he wrote: 'Anyone who has been brought up in a conventional home will know the difficult adjustment necessary for the member of the family who chooses another faith.' Attlee joined the Stepney branch of the ILP because he felt morally obliged to associate himself openly with the only men who had organized to bring about the order of society he himself had come to believe in. He did not see himselfas a political activist, but this was what he immediately became. In January I908 the Stepney branch of the ILP numbered sixteen. All were members ofa trade union, so he immediately joined the only one for which he was eligible, the National Union of Clerks. At the time he joined the Stepney ILP he was the only member of it who was not fully employed, who had enough spare time for political activities during the day. Within a few weeks, somewhat to his embarrassment, he was asked to act as its branch secretary. This meant not only organizing ' branch meetings, and keeping the minutes, but also standing in for speakers who failed to turn up to proselytize on street corners. The idea of mounting the soapbox to indict the leaders of his own class did not appeal to him, and the thought of speaking in public he found alarming. But, again, he felt he must show the courage of his convictions.