Artists of Hawaii: Volume Two 9780824887346

273 34 22MB

English Pages 112 [116] Year 2021

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Francis Haar (editor)

- Murray Turnbull (editor)

- Francis Haar (editor)

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

Artists of Hawaii

Artists of Hawaii Volume Two

Photographs and Interviews by Francis Haar Edited by Murray Turnbull

The State Foundation on Culture and the Arts and The University Press of Hawaii I Honolulu X

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data (Revised) Artists of Hawaii. Vol. 1 has also special title: Nineteen painters and sculptors. Vol. 2: Photos, and interviews by F. Haar; edited by M. Turnbull. 1. Artists—Hawaii—Biography. I. Haar, Francis. II. Neogy, Prithwish. N6530.H3A77 709'.2'2 74-78861 ISBN 0-8248-0338-8 (v. 1) 0-8248-0467-8 (v. 2)

Copyright © .1977 by The University Press of Hawaii All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Manufactured in the United States of America

Contents

Foreword Preface

vii ix

Acknowledgments The Artists

Pegge Hopper

24

Mamoru Sato

Claude Horan

29

Ken Shutt

Erica Karawina

xi

Ruthadell Anderson

3

Ron Kowalke

Jean Williams

49

8

Tetsuo Ochikubo

54

Joseph Goto

14

Vladimir Ossipoff

59

19

Reuben Tarn

42

Joseph Feher

Charles E. Higa

Alice Kagawa Parrott

74

Toshiko Takaezu

36

Kenneth Kingrey

1

69

John Wisnosky

64

79 85 91 96

Foreword

Because Volume 1 of Artists of Hawaii, published t w o years ago, could not possibly encompass all of Hawaii's equally qualified artists and craftsmen, publication of a second volume has always been imperative. The artists for this, the second volume, were nominated, after long and thoughtful consideration, by a broadbased committee of knowledgeable people from Hawaii's art world — a committee appointed by the Board of the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts. Their aim was not only to assure fairness, but to be comprehensive — even, for the time at least, conclusive, for this may well be the last volume of the series. W e fear, however, that w e have again failed to achieve these goals. The cross section of art forms and artists so carefully selected, although representative of the best of Hawaii's artists, is still not truly comprehensive and is far from conclusive. Another of our goals, to demonstrate by photograph and statement that artists born in or living and working in Hawaii for long periods of time reflect in their work some aspects of Hawaii's unique cultural and scenic environment, may also have eluded us. Our editor argues persuasively why regionalism in the arts must be a delusion. And yet there is the im-

pact Isami Doi had on a large number of the younger artists of his time. There is the work of an entire generation of ceramists growing out of the teachings of Claude Horan, which blends the influence of the English and Japanese masters who visited Hawaii at this most receptive period of time, producing a Toshiko Takaezu, among many others. And there was Madge Tennent and there is Jean Chariot w h o devoted their lives in Hawaii to the conversion and adaptation of everything they have achieved in their artistic lives to what they learned, felt and feel, loved and love about Hawaii. And can w e not, indeed, find a subtle flavor in the work of the more mature of Hawaii's artists expressive of the diversity of ethnic background and of the Islands' colorful environment? Thanks to matching grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Hawaii Bicentennial Commission, the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts has been able to help produce a film complementing the t w o books and the artists selected. Here too, Francis Haar, the sensitive and accomplished photographer and filmmaker, developed mere rudimentary suggestions of ideas into a masterful whole. Under his direction the film has been edited into one

one-hour long version, t w o half-hour reels, and a ten-minute mini-film for each of six fields of art. The debt of gratitude w e owe this great and humble artist cannot be adequately described. For more than two years he was totally dedicated to and immersed in the creation of these three correlated projects, working with the artists themselves, the editors of the individual volumes, and the staff and crews of Hawaii Public Television, where he touched, invigorated, and inspired every one involved. W e are proud of Hawaii's artists, those depicted in the books and film, and those many more for w h o m the space was not sufficient. We are also very grateful to all who contributed to those publications — t o o numerous to name individually — a n d to those w h o have helped to make these publications possible. Most particularly, w e thank Governor George R. Ariyoshi, without whose sympathetic understanding and direct help we would not have been able to undertake this work. Alfred Preis Executive Director State Foundation on Culture and the Arts

vii

Preface

The visual arts of the twentieth century have become both diversified and internationalized. Images and forms not only multiply and overlap one another, but do so in such a fashion that there is seldom any local identity. Hawaii offers almost no exception. What artists are doing in Hawaii is much what artists are doing everywhere else, and for much the same reasons. The roots of art spread wide in modern society but are not often deep. The sources of ideas, forms, and feelings, for the artist as for most others, are more often than not to be found in a ubiquity of anonymous experiences that traverse boundaries, sometimes at the cost of understanding, commitment, or feeling directly obtained from personal experience itself. Coca Cola is not the only syrup that appears everywhere. Hawaiian artists have caught up in technical skill with their counterparts elsewhere and are working a la mode, or in most of the current fashions. They have available the same publications and reproductions, the same training, the same ideas as artists anywhere else, and they are just as subject to fashion. Like most others, they are great manipulators and are more apt than not to focus on a world of materiality and objects.

In a number of ways this represents a coming of age for Hawaii. The enormous cultural lag of only fifteen or twenty years ago has been in some measure overcome. Hawaiian artists are not now, as they were then, entirely outside the main stream. If they blow with the wind, they are at least aware that there is a wind blowing. If Hawaiian art today could be characterized in a way that would differentiate it from art in other places, it might be by noting that Hawaiian artists and their audiences tend to perceive that wind as a gentle breeze. Hawaiian art is polite and tasteful. It is seldom disturbing or moving. It knows its place. It does not raise serious questions. It seeks to affirm what we know and to comfort our expectations. It is complacent. At their best, the attitudes that give rise to such art are productive of a kind of restrained elegance, shibui, of a sort to be found most highly developed in an earlier Japan or in France in the eighteenth century. Such art can be pleasant and entertaining, even delightful. It cannot be said to add in any measure to our experience or to acknowledge a world torn in agony. It embellishes but does not illuminate our realities. Hawaii is a pretty place. Its arts are pretty

things in pretty places. That any artists rise above this level is worth our special attention. Some who are represented in this book do so. Perhaps it is in their work that one may find a promise for an internationalized art which will grow deeper roots and thereby a more substantial tree, to bend with the wind while developing a character and identity of its own. It should not be forgotten that Francis Haar was the instigator of this volume and its predecessor, that he conducted the interviews for this one, and, most importantly, that he is in fact one of the artists represented. His photographs tend to be self-effacing on the surface, and are not distinguished by cleverness or mannerisms. They have the rather larger and more enduring qualities of something substantial, and if he keeps himself in the shadow it is only to direct his great competence toward the evocation of character in each of the individuals on whom he focuses his attention. The way in which we understand any of them is thus through the juxtaposition of samples of their own work, phrases of their own making, and the keen eye and responsive vision of Francis Haar. Murray Turnbull

ix

Acknowledgments

I would like first to express my deep gratitude to the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts and its director, Alfred Preis, for making possible the publication of this book. My heartfelt thanks go also to Murray Turnbull for his

work as editor and for his continued encouragement; to Mirella Belshé for her enthusiastic cooperation during interviews with the artists; to Tom Haar, my son, w h o in my place prepared the photographs of the four Mainland

artists and their works and conducted the interviews with them; and to Veronica and Wendell Peacock who carefully transcribed and typed the tape-recorded interviews. Francis Haar

xi

The Artists

Ruthadell Anderson

Erica Karawina

Mamoru Sato

Joseph Feher

Kenneth Kingrey

Ken Shutt

Joseph Goto

Ron Kowalke

Toshiko Takaezu

Charles E. Higa

Tetsuo Ochikubo

Reuben Tam

Pegge Hopper

Vladimir Ossipoff

Jean Williams

Claude Horan

Alice Kagawa Parrott

John Wisnosky

Ruthadell Anderson

Born 21 January 1922, San Jose, Calif. San Jose State College, B.A., 1943; University of Hawaii, M.F.A., 1964. Commission weaver since 1964. Commissions: Bank of Hawaii; Kauai Surf Hotel; Hawaii State Capitol; Kona Surf Hotel; Hawaiian Telephone Co.; First National City Bank, Agana, Guam; Banque de Polynesia, Tahiti; Saipan Continental Hotel; Regent of Fiji Hotel. Exhibitions: Honolulu Academy of Arts, 1967, 1970, 1974, 1975; Hawaii Craftsmen Annual, 1967 (award), 1969 (award), 1970, 1972 (award); Oakbrook, Illinois, 1970; Little Rock, Arkansas, 1966. Citation for Arts and Crafts, Hawaii Chapter, A.I.A., 1971. Collections: Honolulu Academy of Arts; State Foundation on Culture and the Arts; Hawaii D.O.E. Artmobile; private.

I had my first weaving instruction in high school, followed by more classes at the college

level, but I've enjoyed making objects for as long as I can remember. Between 1943 and 1963 I was active in various craft activities and gained a little professional experience in a weaving studio here in Hawaii in the early 1950s. I returned to the University of Hawaii in 1963 to obtain my master's degree in weaving. It was my intention to open my own studio to do commission work after receiving a degree. I felt that there was a growing need for and an interest in such things, both for residential use and for public buildings. Since 1966, when I did my first woven mural for a local bank, I have been kept busier than I sometimes want to be. I feel a lot of it can be attributed to having been in the right place at the right time. At present I am assisted by one other person, but there were times when I had as many as ten people assisting me, for example, when we worked on the murals for the Hawaii State Capitol. I really enjoy the stimulation of working with others. Although there are limitations one must face when working on commission, I find the challenge of real problems exciting. In the

chambers of the Hawaii State Capitol, I was faced with the problem of placing my woven murals on walls that had loudspeakers centered on them. These had to be integrated into the design without changing the acoustics of the chambers. My work has been influenced by the flora in Hawaii, and I often incorporate natural plant fibers in my textiles. At other times my designs are developed from forms found in nature. In some of my commissions, I have been required to develop designs from South Pacific art forms. I try to look at as many examples from a given culture as possible. Then elements are selected and often combined in much larger scale, to create bold and rather simple forms that will carry across a hotel lobby, for instance, but will also have sufficient textural interest and detail if the piece is to be viewed at close range. Most of my work I consider conservative. I usually reject the sensational for more timeless expression. The creative act gives me the most satisfaction. I lose interest in a piece once it is completed.

3

Woven

mural,

untitled

1973 Ghiordes knots, w o o l on linen w a r p , 39' x 32' ( b o t t o m ) x 25' (top) Senate C h a m b e r , Hawaii State Capitol C o m m i s s i o n e d by t h e State of Hawaii

Woven

hanging,

untitled

1970 Double weave, natural plant fibers with wool and synthetic yarns, 4.5' x 10' Garden Cafe, Honolulu Academy of Arts

6

Joseph Feher

Bom 23 April 1908, Miskoltz, Hungary. Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Budapest, 1924-28; Academy of Fine Arts, Florence, 1924; Chicago Art Institute, 1928. Instructor, Institute of Design, Chicago (New Bauhaus), 1942-44; artist-historian, Bishop Museum, 1955-69; Honolulu Academy of Arts: since 1947, instructor, Art School; at present, curator of studio programs and senior curator. Extensive travel, Europe and the Pacific. Numerous commissions include design of Hawaii Statehood Commemorative postage stamp, Bishop Museum exhibit at New York World's Fair, drawings and watercolors for Navy exhibit "Navy in Micronesia"; design and illustration of many books, including Hawaii: A Pictorial History; numerous awards for graphic design; works shown in mainland museums and galleries; represented in many permanent collections.

I often think h o w accidental it was that I came to settle in Hawaii. In the spring of 1934 I started out from Chicago to go to Tahiti, arriving in San Francisco t w o days after the monthly freighter had left for Papeete. Crushed, and too impatient to wait for the next ship, I took the advice of a friend to visit instead Kalapana in the Puna district on the island of Hawaii. Kalapana was beautiful —everything that I

8

was expecting originally of Tahiti. I lived in a little shack near the ocean surrounded by coconut trees. The high tide came up to the house and changed the water daily in the "outdoor bathtub" pool. A t that time Kalapana was a remote and peaceful Hawaiian c o m m u n i t y where more Hawaiian was spoken than English. The only other non-Hawaiian living there was my nextdoor neighbor, Father Everist Gielen, a Belgian priest w h o was in the process of transforming his little church to a "cathedral" by painting oil murals on the w o o d e n walls. I used to keep him company, playing Hungarian songs on a small pump organ, while he painted. Father Everist was a simple, dedicated man w i t h great compassion and love for the Hawaiians, a real " f a t h e r " to the community; taking a sick child to Hilo in his Model T in the middle of the night —or any time —was the kind of service he provided constantly. The people in Kalapana responded to this gentle priest w i t h affection. Life was peaceful there and I thought I would never w a n t to leave, but reality intervened and after eighteen months I w e n t reluctantly back to Chicago. But in the city I never lost the longing to return to Hawaii, and in 1947 the opportunity came to teach at the Honolulu Academy of Arts. I have been a member of its staff ever since.

My association w i t h the Academy has given me a rewarding opportunity to be w i t h people whose interests and aspirations are similar to my o w n . The physical environment and the collections of the Academy have nurtured my pursuits as a teacher and artist through the years. I am ever grateful that forty-two years ago I missed that freighter in San Francisco. It is always difficult for me to talk about my involvement w i t h art. As long as I can remember, the use of the brush and the pencil has been essential to my existence. Drawing or painting is a compulsion for me, at times a result of being hurt or angry, and at times a kind of singing in gratitude for being alive. In painting I have never consciously sought any direction or style, but outside influences no doubt have affected my m o d e of expression. The works of artists of other times and other places have also been my companions and teachers. I have always painted for myself. Maybe that is the reason I've never formulated verbal commentaries. I have not needed justification or explanation. Painting is like a confession between the artist and someone w h o w o u l d understand a painting without verbal explanation.

THE SURVIVAL

OF THE

1971

10

Oil, 30" x 38" Collection of the artist

UNFITTEST

DRAGON

SHIP

1972 Intaglio, 10.75" x 17.5" Honolulu Academy of Arts

ALICE 1952 Charcoal drawing, 20" x 24' Collection of the artist

12

Joseph Goto

Born 1920, Hilo, Hawaii.

h o b b y . I d i d s o m e w a t e r c o l o r . A f t e r the w a r ,

sheet metal w o r k ; it's solid steel. I feel like a

Art Institute of Chicago and Roosevelt University, Chicago, 1947-51.

I w a s a c c e p t e d at the A r t Institute in Chicago.

steel w o r k e r w h e n I'm w o r k i n g w i t h sculpture.

I w a s n ' t very serious w h e n I started. I w a n t e d

I w o r k in steel plate.

Asst. prof, of art, College of William and Mary, 1958-59, Univ. of Michigan, 1959-63, Rhode Island School of Design, 1963-65; lect., Univ. of III., Chicago, 1965; visiting prof., Carnegie-Mellon Univ. 1968, Brandeis Univ. 1970; welder, Tower Iron Works, 1966, 1969. Exhibitions: Frumkin Gallery, Chicago (3); Frumkin Gallery, N.Y. (3); Radich Gallery, N.Y. (3); Pittsburgh Internat'l Exhibition of Contemporary Arts, 1970; Rhode Island School of Design, 1971; Zabriskie Gallery, N.Y., 1973; Honolulu, Canton Art Institute, Storm King Art Center (N.Y.), Kennedy Plaza (Providence)-all 1975. Fellowships: John Hay Whitney Found., Graham Found., Nat'l Council on the Arts, Guggenheim; Rhode Island Governor's Arts Award; College Women Association of Japan, Tokyo.

to be a painter. I w a s majoring in p a i n t i n g and d r a w i n g and m i n o r i n g in p r i n t m a k i n g and ceramics. T h e n I g o t i n t r o d u c e d to steel sculp-

m y potential. I like to relate m y w o r k t o sculp-

ture d u r i n g m y last y e a r — i t g o t m e all excited

ture and not objects. M y c o n c e p t of steel is t o

a b o u t being a sculptor. I had lots of encou-

use it for sculpture purposes and not as indus-

r a g e m e n t ; the M u s e u m of M o d e r n A r t b o u g h t

trial objects. I've w e l d e d industrial objects —

a piece in Chicago and I g o t a grant and a

tanks and s u c h — v e r y beautiful in t h e m s e l v e s .

f e l l o w s h i p . T h a t k e p t m e g o i n g , and I b e g a n to

But they d o n ' t call s u c h t h i n g s s c u l p t u r e ; t h e y

w o r k harder. I w o r k e d in Chicago for a w h i l e

call t h e m w h a t e v e r t h e y are. There's a p u r p o s e

and w o n s o m e prizes. Lots of e n t h u s i a s m and

to t h e m , w h e r e a s m y t h i n g s have no p u r p o s e .

e n c o u r a g e m e n t in Chicago.

T h e y just sit there. I try to g e t as far a w a y as I

From Chicago I w e n t to Virginia to teach.

can f r o m industrial things.

I t a u g h t there for a year and then w e n t t o the

C u t t i n g t h e steel is like carving, as in the

University of M i c h i g a n . From M i c h i g a n I c a m e

Matisse and Picasso c u t o u t s . It's not mechani-

to Rhode Island.

cal. It's not a logical t h i n g t h a t y o u learn; it

I think w h a t m a d e m e g o into steel sculp-

c o m e s f r o m long experience. It's the feeling of

ture is t h a t I had a b a c k g r o u n d in steel w o r k .

being right, b u t not the right calculations.

I w o r k e d for the A r m y Engineers a n d the Red

goes b e y o n d calculations, and so y o u c a n ' t repeat it.

During the w a r I w e n t t o t h e H o n o l u l u

Hill u n d e r g o u n d project. I k n e w s o m e t h i n g

A c a d e m y of A r t s a n d s t u d i e d d r a w i n g . I w a s

a b o u t rigging and steel w o r k . M y last sculpture

interested in art b u t not s e r i o u s l y — j u s t as a

is steel w o r k . It's not w e l d e d s c u l p t u r e ; it's not

14

T h e reason for s w i t c h i n g f r o m small steel sculpture t o large scale is t h a t I w a s not using

It

It gives m e a g o o d feeling t o build t h i n g s .

NO. 4, TOWER-1 RON 1960-1966 Welded steel and stainless steel, 9 1 " 16

Collection of the artist (Photo by Tom Haar)

NO. 5, TOWER-1 RON

1968 Cor-Ten a n d stainless steel, 17 t o n s W Q E D Building, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

(Photo

by Tom

Haar)

17

Charles E. Higa

Born 1 February 1933, Honolulu, Hawaii. University of Hawaii, 1951-55; New York University, 1955-56. Instructor of drawing-painting-ceramics, McKinley High School, Honolulu; Outstanding Secondary Educator, Hawaii, 1974; Teacher of the Year, 1970; Outstanding Young Educator, Hawaii, 1967. One-man shows: Berlin, Germany, 1958; Honolulu, 1961-74; Canada, 1965; Watercolor USA, 1963, 1965, 1967; Northern Illinois Crafts Invitational, 1970; The Excellence of the Object, American Crafts Council Exhibit, 1969; Crafts IV, Southwest Regional, California, 1968. Permanent collections: Honolulu Academy of Arts; Honolulu Advertiser; State Foundation on Culture and the Arts. SFCA sculpture commissions: Honolulu Airport Terminal; Chemistry Building, Univ. of Hawaii.

As long as I can remember, I was always drawing, doodling, and involved with doing something with my hands. I don't know why; I just enjoyed it. It was just scribbling sometimes, but mostly it was drawing; and I was reprimanded for it all the time. I think it was because I loved to draw and was intrigued with people and their lives that I did well in my studies. I remember in the seventh grade I would relive, just by drawing, the grandeur of

Rome, the ancient Greeks, and conquests of great personalities. In science classes I drew leaves and all kinds of things. I was visually oriented, and that is how I learned. I was not good in mathematics. Math was just numbers and meant nothing to me because I could not figure it out visually. It did not attract me because the human side of it was missing. It was mechanical, it was not alive. I studied advertising art at the University of Hawaii, although I had a fine-arts background. I went to New York and received my graduate degree. It was there that I realized the exceptional quality of the education I had received in Hawaii. The two most influential people in my art have been Kenneth Kingrey and Jean Chariot. Kingrey showed me how to develop ideas and their relationships to the world around us, and Chariot awakened me to my presence in art through his excellence in art history. However, all I have come into contact with share this credit. I went into the army and was stationed in Berlin. It was there that I started painting to occupy my free time, especially during the winter when the weather was so cold. My painting technique began there. As soon as I got out of military service, I started my teach-

ing career. I was fortunate in having had such excellent teachers, who were also great human beings. It was inevitable that I try to be like them. I was never so excited about art as I was in teaching. I returned to New York and began my work for a doctorate while working with an advertising agency. This ambition was replaced by an urge I could not explain. I was bored in advertising art, and I wanted so much to paint and work with people rather than to bury my nose in books. I returned to Hawaii to teach and to create. It was because of teaching that I began working in ceramics. I realized that it was an excellent meeting ground for all people, and had been since the dawn of history. Most of all, it was a human-involved thing that brought people together either by common needs or uses. This is universal. Teaching is entirely another challenging experience. It is a continuous giving. This continuous giving must relate, assimilate, and develop within the realm of human experience to be meaningful. It has given me strength in art. The more I taught, the more my own work improved. And I will continue to teach, for it means being around human minds which continually nourish and replenish the energies within me to create.

19

ONE-TWO-THREE

EQUINOX

1975

1973

Ceramic, 1 9 " x 9 "

Ceramic, 1 2 , 5 " x 1 3 " x

W a s h i n g t o n Place, H o n o l u l u

Collection of t h e artist

C o l l e c t i o n of the State F o u n d a t i o n o n C u l t u r e a n d t h e A r t s

MILKY

22

WAY

MIDNIGHT

1974

1973

Ceramic, 15.5" diameter

Ceramic, 16" x 9.5" x 5 "

C o l l e c t i o n of the artist

C o l l e c t i o n of the artist

Pegge Hopper

Born 7 June 1935, Oakland, California. Art Center College, Los Angeles, 1953-56. Mural designer, Raymond Loewy Associates, New York, 1957; Principal Artist, La Rinascente department stores, Milan, Italy, 1961-63; art director, Lennen & Newell Advertising Agency, Honolulu, 1967-69; at present, painter and freelance designer, Honolulu. One-man shows: The Foundry, Honolulu, 1971; Downtown Gallery, Honolulu, 1972, 1974. Best-inshow. Artists and Art Directors Club Annual Show, 1968. Permanent collections, Hawaii: Contemporary Arts Center of Hawaii, State Foundation on Culture and the Arts, Castle & Cooke Ltd., Pacific Club, Waialae Country Club. Mural Commission: State Foundation on Culture and the Arts, for Honolulu Community College.

I have always been intrigued with the design possibilities of the human body. To me it contains everything —the beauty, mystery, and potential of line, color, and form. Everything I enjoy doing is somehow related to it. Why Hawaiian women? I think it was fate that brought my husband and me to Hawaii and exposed me to their beauty: the mass and strength of their bodies, the color of their skin, the shapes of their noses and mouths. Their

24

unhurried, unaffected attitude also greatly appeals to me. The large strong body suggested and simplified by the bright muumuu: it all came together somehow. I guess I try to create a personality, a strong personality as well as a strong visual statement.

I am concerned and fascinated with visual tensions —tensions you can feel when you try to fit a large, life-sized body into the confines of a canvas. As I sketch and search for ideas I imagine feeling the pressures and spaces on my own body. I think of the feeling as a moment in time, a moment between movements. Drawing is the essence. I drew all through school, somewhat neglecting my other studies. When I finally went to Art Center College in Los Angeles I felt like the ugly duckling turned into a swan. I could finally draw all day long and not get into trouble for it. I worked very hard for three and a half years. I had two fine teachers who opened up to me the world of the old masters and of fine draughtsmanship — Lorser Fietelson and Harry Carmean. From them I discovered the infinite possibilities of the human form. I went into commercial art after leaving school and did department store murals in New York and posters and fashion illustration in Milan, Italy, for two years, and then was an

art director for a Honolulu advertising agency. From these experiences, and because I've lived with a fine graphic designer for eighteen years, I have developed an interest in graphics. I found that the simplicity of line, form, and color that had the strong visual impact necessary for successful graphic design was very exciting, and these two elements, drawing and graphics, have become my main concern. When I start a painting I feel great hope and exhilaration. However, the end result is never the masterpiece I'd visualized in my mind's eye. So I agonize, but only briefly. I cannot rework extensively. I have to move on. I dread confronting a past painting; it's like seeing yourself in a movie. I know it won't live up to my expectations of what I want to see. I care very much that my work be of what I call "good quality" and "meaningful." However, these are such subjective terms that, if I think too often about how "good" my work is, I get very confused. I have given up comparing myself with others; I guess you reach a point in your life where you have to accept what you've become. You must open yourself up to yourself and not be afraid of what you see. I hope I will see a long, productive life, one in which I don't get in the way of realizing my full potential.

Mural,

untitled

1975 Acrylic, 23' x 41' Honolulu Community College Library Commissioned by the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts

26

Drawing,

untitled

1975 Pen and ink, 8 " x 1 0 " Collection of the artist

27

Claude Horan

Born 29 October 1917, Long Beach, Calif. San Jose State College, B.A., art; Ohio State University, M.A., art. Instructor, arts and crafts, Fremont Union High School, California, 1942-46; instructor, ceramics, San Jose State, 1944; started ceramics (1947) and glass blowing (1968) programs at Univ. of Hawaii; at present, professor of art, Univ. of Hawaii. Exhibited in most national juried and invitational ceramics shows; represented U.S. craftsmen in t w o traveling exhibits in major museums of western Europe. Permanent collections: Smithsonian Institution; Museum of Contemporary Crafts, N.Y. Numerous architectural ceramics for public and private buildings in Hawaii, and commissions for State Foundation on Culture and the Arts (with wife, Suzi Pleyte).

I came into art through the back door. Going to college was the furthest thing from my mind while in high school. Swimming, playing water polo, surfing were my life in those days. I used to hang around the advertising room, where all the high school "wheels" would congregate and paint posters and draw cartoons and signs for the coming football games. This was my introduction to a somewhat informal art group. Because of my swimming ability I received a quite minimal scholarship to Fullerton Junior

College, a veritable powerhouse in water polo and swimming circles. Needless to say, I took the easiest courses I could to pass and stay eligible. While life-guarding in Venice, California, I met t w o or three fellows w h o persuaded me to go to San Jose State and swim and play water polo for them. Major? Art — c i n c h courses — n o h o m e w o r k — easy to keep eligible for sports! So on to San Jose State. But after majoring in art I felt guilty and changed my major to physical education. Then came ceramics — n o h o m e w o r k — j u s t make pots. In fact, when I first started working on the potter's wheel, I treated it like another competitive activity. Me against the wheel, striving for perfection, as I had done with my swimming strokes and surfing techniques. My interest in ceramics slowly pushed aside my water activities and soon I was concentrating on it full time. At this stage I became aware of the ceramics environment I was in, and that working in clay was no longer just a physical thing for me. So I left physical education and finished my B.A. degree with a major in art. I was very fortunate to have Dr. Herbert Sanders for my undergraduate courses in ceramics. His stressing of fundamentals for beginning potters I still agree with today, and in fact I feel it is one of the strong points of my own teaching philosophy. My work in those days (1942-1944) was fairly tight, academically sound pottery. Even so, I never really was interested in making

utilitarian ware. As far as I was concerned, everything I made was a decorative piece, sculptural, or whatever you may want to call it. I was mainly interested in the form of the object. My breaking away from traditional pottery came when I started teaching at the university in Hawaii. On the mainland I had noticed, in quite a few ceramic departments, that most of the student work resembled their instructors'. This was one thing I didn't want to happen here. So, as soon as a student mastered the fundamentals, I "encouraged" him to break all of the so-called rules of working with the clay and to explore its unlimited possibilities, to push back the limitations imposed by the materials and production techniques available. This worked well, not only for the students but for me as well. Soon I started to do more and more sculptural forms, both representational and abstract, using wheel-throwing techniques along with hand-building. I started doing architectural ceramics, which got me into making decorative tiles. Most of these were either outdoors or in the bottom of swimming pools; so I started working with stoneware majolica glazes in order to develop some bright colors that could compete with the Hawaiian clear blue skies and multicolored flowers. I also have enjoyed doing outdoor sculpture for children to lounge around on, again using bright majolica glazes. No matter how satisfied I have been with work once c o m p l e t e d — t h e 29

challenge met and conquered — t h e r e always seems to be a letdown. Quite recently I have been experimenting with throwing shapes on the wheel and then dropping them to obtain some unexpected

30

forms. This has led to making murals by dropping the pot-forms on a previously rolled out slab of clay, and then doing some beating, or "adjusting," of the shapes until I feel it satisfactory. There is no doubt about it; I am

strongly influenced by the technique and the materials I am using. I have just started making these so-called dropped forms, and I can't wait to see where it will take me next.

SEA

SERPENT

1976 Ceramic, 3' x 14' Red Hill Elementary School, Oahu Commissioned by the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts

DAMN THE SEAGULLS, DON'T FLY

IT'S A GOOD THING

COWS

1976 Ceramic, 2' x 3' Collection of the artist

33

Erica Karawina

Born 25 January 1904, Germany. Study tours in Europe and Asia. Numerous one-man shows in East Coast galleries and museums. Permanent collections: Library of Congress, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Metropolitan Museum, Worcester Fine Arts Museum, Colorado Springs Art Center, Addison Gallery, Museum of Modern Art, Honolulu Academy of Arts, Tennent Art Foundation, private. Architectural stained glass in Hawaii: Waioli Chapel, Wesley Methodist Church, St. Andrew's Priory Chapel, Holy Family Church, Punahou School Chapel, Manoa Valley Church, Epiphany Episcopal Church, State Office Building, Advertiser News Building (all in Honolulu); Commissioned Officers' Club, Pearl Harbor; Mililani Memorial Park Chapel; Olive Methodist Church, Wahiawa; Liliuokalani Church, Haleiwa; St. Anthony's Church, Kailua; All Saints Columbarium, Kauai; and others.

My natural love of art was nurtured by my parents, who took me with them to see the great art museums and cathedrals of Europe. My training was as an easel painter and printmaker, and I was happy in this work until, many years ago, I was introduced to stained glass in the studio of the late Charles J. Con-

36

nick in Boston. When I saw those stacks of beautiful glass, I knew immediately that that was what I wanted to do. And I have worked with stained glass ever since. I had several good instructors, but the teachers who influenced me most were the unknown artists of the early Gothic period, the creators of the gemlike stained-glass windows, the mosaicists, and the Byzantine icon painters. A great stained-glass window might be compared to a symphony. It requires the effort of many people: there are the people w h o do the layout, others w h o draw the cartoons, and then cutters, painters, and finally the leaders, who put the whole thing together with lead carries. This method has not changed for centuries. Now I design primarily for faceted glass. This is a newer method in which w e use oneinch-thick glass embedded in cement. W e do not paint on this glass, nor do w e hold the pieces together with lead. Instead, w e place them in a mold and cast them in cement. The first time I saw this type of glass was at Raincy, near Paris, where Perret built his first modern church in concrete and glass. I promised myself then that some day I would work in this medium. But my migration with my husband from New England to China, and a whole world war intervened, and it was not until w e

finally settled in Hawaii that I was able to work again with stained glass. In making stained glass I literally paint with light. In choosing colors, am I influenced by nature? Yes, a lot. There is a sort of osmosis; you just about absorb it, especially in Hawaii. Light, of course, is very important. Surface light, for instance, can literally destroy the best stained glass. I do not need direct sunlight, although I would like it. The play of clouds and moving trees makes for fascinating variations, and the glass begins to come alive. It is never a static thing; on the contrary, it is kinetic without any mechanical contrivance. And that, to me, is the beauty of it. That, and the very glassiness. This may be the reason why I am impressed with raindrops, rainbows, running streams, and waterfalls. It has something to do with moving light. How do I begin a large commission? The architect usually suggests that I study the site and the blueprints. This is the ideal way. But often I am called in afterwards, which is much more difficult and causes technical problems. I have enormous respect for architecture. I feel very strongly that stained glass should be coordinated with a building and that I must work closely with the architect. Only after I know the type of building, the kind of light exposure, and the function of the room do I begin to design.

MMWiS •'

imtat

JSWWMW-

; •

s§»-r « m

«¡£t

&

igsi®

Iii

HI

j f l L

3I

J

* "

i

D

i

f

i

*aaSBt

i f - r «

SBB9E üSäSSi

vaasxsa

,„,„„

*! ! S » r O i l I S i f f f "

p

4

^S

«TAX»

;f V-^Ss® psabASff^iK ;

8

SMSblUi Hips? •I" 4 —

«

-aa^artÖÄte"^

t

ipr

W

T 8 8 ®

* «

;

-Vi. SV •* l-é . '

1

• .

'

-

,-f^

>>

f

£

W i s

/v-i

. » *

m

•

*

-

* ;

V ?

_-Ä-JSS&ü

i „ J§| .

'•'TfflT*":.'-

'

W

W

W

»

-

!

A W A K E A - N O O N

1976 Faceted glass, detail Kalanimoku (Hawaii State Office) Building

39

^

•

jh

••

m

Vtfft-VWV • • f i . " '

KAKAHIAKA-MORNING

40

Translucent-glass mosaic murals. 1976

AWAKEA-NOON

Faceted glass, each mural 11' x 64'

AUINALA-AFTERNOON

Kalanlmoku (Hawaii State Office) Building

PO —NIGHT

Commissioned by the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts

»W '.".

'"ii•

••"¡PBIlfl

••!»

ft

Kenneth Kingrey

Born 23 D e c e m b e r 1913, Santa A n a , Calif. U.C.L.A.: B.Ed., 1940; M . A . , 1942. Asst. prof, of art (design), U.C.L.A., 1 9 4 0 - 4 7 , 1 9 5 1 - 5 3 , 1966; prof, of art, Univ. of Hawaii, 1 9 5 0 - 1 9 5 1 , 1 9 5 3 - ; p r o g r a m c h a i r m a n , design, 1950-51 (initiated program), 1 9 5 3 - 7 0 . M e m b e r : Nat'l Society of Literature and the Arts, Hawaii Artists League, A d I n f i n i t u m , Hawaii Council for Culture a n d t h e A r t s , Jean Chariot Foundation, T e n n e n t A r t Foundation. A d v i s e r : Statuary Hall C o m m i s s i o n , Honolulu Council f o r Culture a n d the Arts. J u r o r , n u m e r o u s art exhibits, Hawaii, 1 9 5 0 - 7 6 . Listed in: Who's

Who in American

of International

Biography.

Art,

Dictionary

A w a r d s (book design): A m e r i c a n Institute of Graphic A r t s (2), W e s t e r n B o o k s (6), A m e r i c a n Association f o r State a n d Local History. Publications: Local, national, international.

The Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore w r o t e , " G o d finds himself in creating." I w o u l d humbly add, " T h e artist in creating finds God and himself." There are t w o basic motivating forces in m y life: one is spiritual and the other is perceptual, taking its f o r m in the visual arts. In the formal sense I a m a professor of art, t h o u g h I do not believe one can teach art. One can, however, open up vital creative channels of selfdevelopment in the student and help him achieve, more effectively and rapidly, unreal-

42

ized aesthetic goals. Therefore, m y primary vocation is creative teaching. Basic training in design at the college level becomes primarily a matter of investigation so that the student may develop a highly active sense of creativity and an urge to experimentation and original expression. He is encouraged to observe, analyze, interpret w h a t he sees; to delve into the nature of things; to open his eyes to deeper meanings; to investigate the fundamental processes of visualization, its expression and control, and, at the same time, to attempt to create new images and symbols. Professionally, I am a comprehensive designer, by w h i c h I mean I a m engaged in many areas of design: graphic, interior, exhibition, industrial, and, in a limited sense, architectural. I have acted as designer and/or art consultant for individuals as well as for both private and governmental organizations. The w o r d art is often misused and misunderstood. It has nothing to d o w i t h materials, media, or limitations — t h e s e are merely vehicles for creating art. The w o r d art, w h e t h e r in reference to a painting or a graphic design, implies the existence of certain basic requirements; it implies that a w o r k meets the standards of aesthetic integrity. Jacques Maritain, in his Creative Intuition in Art and Poetry, said: " I t is in the useful arts that w e may discover the most obvious and typical characteristics of art insofar as it is art, and its most universal significance as a root ac-

tivity of the h u m a n race. In prehistoric ages, it seems that the search for beauty and adornment was contemporary w i t h the search for contriving tools and weapons. The fine arts, f r o m the very fact that they belong in the generic nature of art, participate in the law of the useful arts." Giorgio Vasari, contemporary of Michelangelo said of the painter Giotto, "Certainly it was nothing short of a miracle that Giotto should have w o r k e d to such purpose that design was revived to a vigorous life by his means." A t a later time he said of Michelangelo, "Buonarroti criticized Titian's methods, praising him a g o o d deal and saying he liked his coloring and style but that it was a pity good design w a s not taught at Venice f r o m the first." These observations clearly suggest that " d e s i g n " and " p a i n t i n g " were not separate categories of activity during the Renaissance. Picasso, in 1923, w r o t e , " D r a w i n g , design, and color, are understood and practiced in the same spirit and manner that they are understood and practiced in all other schools." Perhaps the difference b e t w e e n the professions of design and painting may be described as a difference in the nature of their limitations — t h o s e of design being externally imposed, functional, or objective; those of painting being self-imposed, expressive, subjective. Such distinctions are significant but are not naturally exclusive. Even externally imposed limitations

may be met in expressive and subjective ways. Therefore, I do riot believe that in practice and in process "designing" and "painting" are essentially different, but, rather, represent variations in preferred activity by the same generic personality — t h e artist. As a bachelor's degree candidate at U.C.L.A., I majored in design, which included the professional specializations already mentioned, as well as costume design and set

design for theatre. Upon graduation I accepted a teaching fellowship there while working for a master's degree, and was responsible for three courses in graphic design. I was then invited to join the full-time art faculty. Over a period of ten years I created an extensive program and major in graphic design, which became the largest major in the art department. In 1950-1951 I initiated a new program in design at the University of Hawaii, after which I returned to U.C.L.A. for two more years. I re-

joined the University of Hawaii faculty in 1953 and continued to develop the new major program, which included a graphic emphasis, and intermediate and advanced courses in design theory applicable to all the visual arts, both in the undergraduate and graduate programs, where the student measures himself according to his needs —professional as well as otherwise.

43

Sanctuary design, St. John Apostle and Church, MiMani Town, Oahu

Evangelist

1973 Architect: Vladimir Ossipoff and Associates

45

Flora Pacifica

1970, Sixth

Ethnobotanical

Exposition

An exposition presenting a cross-section of the histories, culture, and plant life of Pacific Basin communities, to show the relationship of Pacific man to the plant life of his environment

Design Coordinators: Kenneth Kingrey, Bruce Hopper General Manager: James C. Hubbard Photographer: Jerry Chong Honolulu International Center (now Neal Blaisdell Center)

Ron Kowalke

Born 8 November 1936, Chicago, III. Art Institute of Chicago; University of Chicago; Rockford College, Illinois; Cranbrook Academy of Art, Michigan. Instructor, N. Illinois University, 1960; instructor, Swain School of Design, 1961; professor of art, Univ. of Hawaii, 1969-. Exhibitions: Brooklyn Museum; Royal Academy of Arts, Netherlands; Associated American Artists Gallery, N.Y.C.; Rockford College; San Diego Museum; Auckland City Art Gallery, New Zealand; Honolulu Academy of Arts; Contemporary Arts Center of Hawaii, Honolulu. Permanent collections: Metropolitan Museum of Art; Museum of Modern Art; Library of Congress; Honolulu Academy of Arts; State Foundation on Culture and the Arts; Boston Museum of Fine Arts; Gavett-Brewster Gallery, New Zealand.

I started art school on a bet. I had no intentions of going to a professional art school after high school. I was going to work in a factory or a commercial art studio. But when a friend

bet that I couldn't get in, I applied at the Art Institute of Chicago and was accepted. That changed my whole life. I didn't have much of an academic background in high school, so I was really rather intimidated when I went there with students from all over the world. We'd sit and have coffee and they'd be talking about literature, psychology, and politics, and I didn't know what they were talking about. So it finally occurred to me that I really didn't know very much about the outside world. After two years at the Art Institute, I transferred to a liberal arts college because I knew that I didn't need more studio training as much as I needed academic training. There I got involved in political science, international relations, psychology, drama, and literature courses, and then put the two together somehow and began painting subjects based on literary themes. I finally figured out that you can't be just a studio artist and rely totally on your hands and your eye — y o u also have to refer to your intellect. I began using the academic as a source of inspiration for my pictures and I've been doing it ever since. I'm working all the time but not necessarily

in the studio. I'm thinking about picture making. You work every day and you keep getting closer and closer to the center of that subconscious, mysterious limbo of creative energy, and then when you get there, it happens! I often imagine myself to be my regular physical self painting, and all of a sudden, just as in the ghost movies where you have a kind of shadowed, superimposed image, another image emerges and that image does the painting. And when it's finished and I come back, that other self disappears — a n d then it's time to take out the garbage and manage the other mundane things of life. What you must do to paint landscape is to go beyond what you see ordinarily. You're going to have to see up and down and sideways and get inside the subject and then look out from it. I try to have the viewer become part of the landscape. The landscape is then like an environment in which the viewer is the prime concern and the painting is background. You must truly get involved in the water and the land and the mountains and the sky to transcend the common and the mundane, to go beyond the surface reality. You transcend your ordinary self.

49

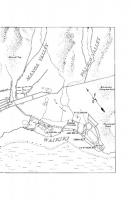

WAIMANALO

BLUES

1975 Oil, 4 8 " x 6 0 " C o l l e c t i o n of t h e S t a t e F o u n d a t i o n o n C u l t u r e a n d t h e A r t s

COMPUTER-SCAPE

NO. 1

1975 Pastel d r a w i n g , 2 0 " x 2 6 " Collection of Mr. and Mrs. J o h n Belshé, W a s h i n g t o n , D.C.

Tetsuo Ochikubo

Born 29 July 1923, Waipahu, Hawaii. Died 26 October 1975. Fellowships: John Hay Whitney, 1957; John Simon Guggenheim Memorial, 1958; Tamarind Lithography, 1961. Assoc. prof, of art: Syracuse Univ., 1964-74; Univ. of Hawaii, Hilo, 1974-75. National Endowment for the Arts, Artist in Residence, Hawaii, 1972. Awards: Columbia Museum of Art, S.C., 1957, 1959; Boston Printmakers, 1959; Munson William Proctor Institute, N.Y., 1970; State of Hawaii Commission, 1973, 1974, 1975; Honolulu Academy of Arts, 1974. One-man shows: Krasner Gallery, N.Y. (7), 1958-71; Print Club, Penn.; Syracuse University, 1964; Contemporary Arts Center of Hawaii, 1973. Permanent collections: State Foundation on Culture and the Arts; Honolulu Academy of Arts; Library of Congress; Cincinnati Art Museum; Albright Gallery; Chrysler Museum.

54

In the olden days, if you were going to be an artist you would starve; so my mother didn't want me to be a fine artist. [After the war] I worked as a commercial artist; then I went to Chicago and New York to study fine art. I painted every day, about sixteen hours a day. My wife worked, and so I didn't. As weeks went by I would put less time in my painting because I would get exhausted; so I thought I would do something physical to relax my mind. I started to do carpentry work —fixing furniture —[and then turned to printmaking]. An artist should do everything he wants to do. When he gets up in the morning and says, "I want to do a sculpture!" he should be able to go out and do a sculpture. Next morning he can say, "I don't want to do sculpture, I want to print," and then be able to do printing. I don't classify myself as an abstract artist. If the feeling is abstract, then yes, I am painting

abstract — t h e feeling and subconscious emotions are slowly pushed out. Whenever I have an idea, I put it down on paper. I see rocks and tree formations. I get a lot of ideas from nature. I enjoy printmaking, but it's all physical labor once the design is made, and then I don't have any pleasure in it. My favorite way of printmaking is lithography, sometimes combined with etching. Black-and-white is one thing, but multicolor is much more exciting, especially with color graphs. You can cut out shapes and put them together like a jigsaw puzzle. I feel I understand the East and the West. Now my influence is very Oriental. I am very inclined to Oriental philosophy.

This interview was made only a few months before the artist's death on 26 October 1975. The transcript of the taped interview was edited by the artist's widow.

MIDNIGHT

SUN

1968 Print, 12" x 18" Collection of the artist's family

EXODUS 1966 Black a n d w h i t e print, 1 3 " x 1 9 " C o l l e c t i o n of the a r t i s t ' s f a m i l y

57

Vladimir Ossipoff

Born 25 November 1907, Vladivostok, Russia. Tokyo Foreign School, American School in Japan, Tokyo, 1915-23; University of California, Berkeley, B.A., architecture, 1931. Employed in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Honolulu; licensed as registered architect in Hawaii, 1933, and in own practice since that time; present firm name: Ossipoff, Snyder, Rowland and Goetz. Visiting critic, Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y., 1958, 1962. President, Engineering Society of Hawaii, 1946; president, Hawaii Chapter, American Institute of Architects, 1942, 1965; Fellow, A.I.A., 1958; board of directors, A.I.A., as director of Northwest Region, 1973-75. Honor awards: Hawaii Chapter, A.I.A.; American Society of Landscape Architects; House Beautiful; Architectural Record.

I was sketching in a garden in Tokyo w h e n my mother looked over my shoulder and suggest-

ed that I become an architect. I guess I said, " W h y not?" My aim hasn't changed since. That was back in 1921. I lived in Japan for many years during my youth. The Japanese simplicity, economy, strength of design, and preference for the use of natural materials — t h e w a y the Japanese create their gardens — a l l this has helped to shape my aesthetic development in a subconscious way. Japanese architecture, I think, is better suited to Hawaii, where indooroutdoor living is possible all year around, than to Japan itself. Nature and architecture become inseparable. A n architect from Ceylon once said that in his country the ideal house is an " u m b r e l l a " w h i c h protects the dweller f r o m both sun and rain. This is a distillation of an idea to its simplest expression, and I like it. A house in Hawaii w o u l d do well to observe this simple dictum. Hopefully, good buildings solve problems of visual and social appropriateness, problems of function, site, structure, comfort, materials,

budget, laws, and regulations — a n d withal are dependent upon teamwork and the quality of execution. The very limitations, on the other hand, are a challenge. A great example, the challenge of a most difficult site w i t h a mountain of regulations that w o u l d completely hamstring a less competent architect, is the addition to the National Gallery of Art, presently under construction in Washington, D.C. The constraints imposed by the narrow triangular site and the Capital's regulations are resulting in w h a t probably will be this country's most exciting building for the exhibition of art. Every building should be functional for its users. I don't believe in the sometime popular and perverse adage that "function follows f o r m . " Monuments are the sole exception; their function, through their form alone, is to affect the viewer visually. There, the form can dominate. In all other cases where the form dominates and function must bend to the form, the building most probably malfunctions.

59

House

of Dr. Linus C. Pauling,

Jr.

1956 R e d w o o d a n d local basalt Tantalus, Honolulu

61

Livingroom, house of Dr. Linus C. Pauling, Jr. 1956 Tantalus, Honolulu

62

Alice Kagawa Parrott

Born 12 February 1929, Honolulu, Hawaii. University of Hawaii, 1948-52; Cranbrook Academy of Art, Mich., 1952-54. Instructor of crafts, University of New Mexico, 1954-56; artist in residence, Maui, Hawaii, 1972. Travel to Mexico and Guatemala, 1958. One-man shows: Museum of Contemporary Crafts, N.Y., 1963; Roswell Museum, 1968; Contemporary Arts Center of Hawaii, 1973. Permanent collections: Victoria and Albert Museum; Museum of Contemporary Crafts; Roswell Museum; Museum of Albuquerque; University of Nebraska; University of Texas; Wichita Art Association; State Foundation on Culture and the Arts, Hawaii; Honolulu Advertiser; Hawaii D.O.E. Artmobile; Honolulu International Airport; Maui Community College; Maui County Bldg.

I consider both Hawaii and Santa Fe as my home. I choose to live and work in Santa Fe because of its climate, its Indian and Spanish cultures, and its relatively small population. I live in an adobe house, part of which is a hundred years old. I like the mountains of both

64

Santa Fe and Hawaii. I enjoy living in an area where I can look out and see mountains. In New Mexico I do miss the Pacific Ocean, but only a few miles outside the city there are endless views of the desert and mountains that are uncluttered with homes and skyscrapers. I am constantly searching for colors and designs to use in my tapestries and rugs. I see designs in the Southwest desert landscapes and in the lush foliage of the islands of Hawaii. I am inspired by ancient textiles, the Southwestern Indian art, and my Japanese and Hawaiian heritage. I have gained much from my friend Lenore Tawney, and from my teachers, Hester Robinson, Marian Strengell, Mabel Morrow, Trude Guermonprez, Glen Kaufman, and Kay Sekimachi. Weaving has gained tremendous popularity and recognition in the past ten years or so. Many young people are interested in learning to weave and I get inquiries for apprenticeship nearly every week. Weaving is no longer merely t w o dimensional but is large, daring, imaginative, and sculptural. I am overwhelmed. I weave on t w o looms, a 100-inch-wide, four-harness Leclerc that has been reinforced with steel on front

and back beams for use in weaving large rugs and tapestries, and a 45-inch, four-harness Gilmore jack-type loom for smaller pieces and for double weaves. I begin my weaving by first making many, many sketches. I trace my design to graph paper and also to a piece of cardboard. I glue yarns that I intend to use in the weaving on the cardboard sketch. The graph paper and cardboard yarn sketch are my guides. Weaving is tedious, but I do all my own weaving because I like to be able to control it. Sometimes I change some of the colors or design as I weave, and as the weaving gets rolled on the cloth beam, I wonder how the whole piece will look after it is finally unrolled. Even with all this preparation, I find flaws in nearly all of my work. I keep trying to perfect it with variations of an idea. I am sure that I will continue to do this as long as I weave. I think my Oriental background comes through in colors and when I do nonobjective pieces. I have always wanted to do a weaving based on Haleakala. I get the same type of spiritual feeling when I'm looking down Haleakala Crater or looking at ancient American Indian cliff dwellings at Acoma or Canyon de Chelle.

SEA AND

SHORELINE

1974 Wool and linen, tapestry weave, 4.5' x 6.5' Honolulu International Airport, Governor's Lounge

66

MILAGROS

("Little

Miracles")

1971 Rya knots, slits, and tapestry techniques using wool (some of it dyed with chamiza flowers and aniline dyes), silk, and cotton; 26" x 37" Collection of the artist (Photo

by Tom

Haar)

Mamoru Sato

Bom 15 April 1937, El Paso, Texas. University of Colorado, M.F.A., 1965. Visiting artist, summer session, University of Colorado, 1967, 1974; Associate professor of art, University of Hawaii, 1965-. Extensive travel throughout the United States and Japan. One-man shows: Girma's Art Gallery, Honolulu, 1966, 1969; Contemporary Arts Center of Hawaii, Honolulu, 1968; University of Colorado, Boulder, 1968; D o w n t o w n Gallery, Honolulu, 1976. Permanent collections: State Foundation on Culture and the Arts; Honolulu Academy of Arts; Honolulu Advertiser; Hawaiian Federal Savings and Loan Association; University of Colorado; James Michener; Hayashida Hotel, Kagoshima, Japan.

In college I majored in aeronautical engineering for the first three years. During the last year, I started taking courses in business and art because I really didn't find what I wanted in engineering. I didn't like being a plug-in type of person, looking up formulas, plugging in data to come up with answers. I wanted the freedom to do more thinking on my own. I finally went full-time into art, and it took t w o more years to complete my undergraduate degree at the University of Colorado, followed by another two years for my master's degree. I think most of my work revolves around ideas or concepts. The technique that I use keeps changing, depending on what I'm trying to present. I think the tall brown pieces were done as a result of my living in a high-rise building. My foam pieces are more like landscapes, I suppose. They are an attempt to pre-

sent the natural processes of erosion and the upheaval and lowering of the earth's surface. I don't mean them to be sensuous at all. Sometimes I do things almost as a challenge. I have been trying to explore the possibilities in the use of resin. While polyester and epoxy resins are beautiful materials in themselves, they can look very cheap if not used properly. Also their use involves a very slow process, and so for a while I used stretched vinyls instead, as a reaction against all the tedious work and polishing. This material provides an almost immediate way of obtaining the finished surface. The tactile part of a form is very important. There are a lot of things you can't really see, but sometimes you can touch and feel the imperfections or the quality in a piece.

69

THREE AND

THREE

1973 Polyester a n d e p o x y resin, 1 9 " l o n g C o l l e c t i o n of t h e artist

Ken Shutt

Born 12 December 1928, Long Beach, Calif. Pasadena City College, Pasadena, Calif.; Art Center School, Los Angeles; Chouinard Art Institute, Los Angeles. One-man shows; Southern California, 1961, 1962, 1963; Honolulu, 1967, 1972, 1974. Public works and commissions: Oahu — Sea Life Park; American Savings & Loan Assn. Building; Honolulu Advertiser; Waialae Country Club; State Foundation on Culture and the Arts; Hawaii Public Television Building; Hawaii Air Academy; Waialua High School; Honolulu Zoo. Maui— Maui Surf Hotel; Harbor Lights Condominium. Hawaii— Laupahoehoe High School (SFCA commission); Honokaa Library.

My formal education was in design and painting, and so I derive a lot of my sculptural composition ideas from my painting background. I'm a builder. I think in terms of sculpture by addition. I am concerned with the play of light and shadow on the surface of the sculpture, but I am more concerned with working to a strong silhouette. My sculpture is open, and I

74

try to make the space around and through it an essential part of the composition. In my wood sculpture, the structure is an integral part of the content. On the one hand you have the story-telling quality of the sculpture, and on the other, the structure that is holding it together. One is not superimposed on the other. I don't think of the design as such. The design begins to evolve through the necessity of expressing the content of the sculpture. I always try to get a sculpture up in the air so that it is skybound rather than earthbound. I want the center of content, the interest areas, to be away from the base point and up above eye level where it can be totally involved in space. With the epoxy resin sculpture, the same thinking prevails, but because of its light qualities I am not so concerned with the structural elements. The exciting thing about the resin is the wide latitude of structural possibilities. I can cantilever, I can suspend masses on very fine pinning points, I can use threadlike substances to build large, strong forms. I think the epoxy medium is very compatible with

wood. The wood creates a predominantly geometric shadow pattern, where the resin can create a more softly contoured play of light. The attack of nature in a tropical environment has always interested me. What I am trying to express is this quality of change. The sculpture is not finished until the elements have begun to change it. I want to build sculpture to reflect the environment it is in. A sculpture may be placed in a certain relationship to the sun, with the colors reflecting the way the sun moves across the sky; it is nature making a painting on the sculpture, which becomes totally a part of its environment. Yet sometimes I find it hard to accept the idea of something not built to last for centuries. It hurts a little bit to know that the object may not last forever. I'd like one to last a thousand years, but you sort of trade off. Sculptures are vulnerable, but the change that they go through is exciting, and that is the trade-off. Innovation is not an end in itself with me. I want to go along in my own direction and grow as much as I can in terms of my own art.

MOKUALI/ 1975 Koa w o o d and epoxy resin, model, 36" high Collection of the artist

KONOHIKI 1974 Redwood and epoxy resin, 9' high Collection of the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts

77

Toshiko Takaezu

Born 17 June 1922, Pepeekeo, Hawaii. Education: Honolulu Academy of Arts; Univ. of Hawaii; Cranbrook Academy of Arts, Mich. Teaching positions at several institutions; since 1966, at Princeton University. One-man shows: Univ. of Wisconsin; Hecksher Museum, Huntington, N.Y.; Cleveland Institute of Art; Memphis Art Academy; Vanderbilt Univ.; Contemporary Arts Center of Hawaii; Honolulu Academy of Arts. Invitationals: Johnson Wax Traveling Show; Brussels World's Fair; Smithsonian Institution; USIA World Exhibits. Public collections: Smithsonian Institution; Cleveland Museum of Art; Cranbrook Museum of Art; Museum of Contemporary Crafts, N.Y.; Everson Museum, Syracuse; Newark Museum; Baltimore Museum; New Jersey State Museum; Toledo Museum, Ohio; Honolulu Academy of Arts; State Foundation on Culture and the Arts.

In my high school years I had already a kind of general interest in art and poetry. After graduation I w e n t to the Honolulu Academy of Arts, where I wanted to study sculpture. Later I was thinking that w i t h sculpture I w o u l d not have much future in Hawaii, and also, because it is a very demanding field, I couldn't commit myself entirely to it. A t this time Claude Horan came to Hawaii as an instructor in ceramics. He was a great inspiration; he got me so enthused about pottery that I decided to enroll in

the art department at the University of Hawaii to study w i t h him. I was still thinking that one day I might go back to sculpture. But I got so involved in pottery that I gave my whole energy and attention to this field, and I realized that sculpture could be incorporated in my ceramics also. Continuing my studies, I w e n t to Cranbrook Academy of Arts, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, where I was fortunate to find another excellent teacher, Maija Grotell. She emphasized the importance of personal expression and helped her students to find their o w n identities. W e are all unique individuals, and this should be expressed in our w o r k , she used to say. The three years of study at Cranbrook prepared me to receive a teaching job at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. My interest in the Oriental cultural tradition originated in my o w n family life —celebrating Girls' Day and Boys' Day w i t h festive dress and flying carps. Later I learned to love the Haiku poetry of Basho, Japanese music, and classical Japanese films. In 1955 I visited Japan to try to get a deeper understanding of my ancestors' traditional arts. I found that ceramics is a very significant field of art in the Orient. I was fortunate to work w i t h Toyo Kaneshige, master potter, considered a living national treasure. I also visited Okinawa and worked w i t h folk potters to learn about their fascinating tradition. I went to study tea cere-

mony w h e n I realized that in order to make good tea bowls manual skill is not enough. One must turn inward and try to develop inner human (spiritual) qualities for this w o r k . After my return from the Orient, I tried to incorporate and synthesize the subtle Eastern tradition w i t h a more personal expression of our world here in the Occident. Fortunately, I have lots of energy, and so I can also do weaving and painting, which are my second interests. But w i t h clay I am really fascinated. It is alive and responsive to my touch and feeling. I really do not need to force the clay; I feel how it responds to my hands. There is an interplay between the clay and myself. A piece usually starts w i t h an idea, but during the w o r k process, the clay has much to say. The firing can contribute a lot to our work. As w e have no absolute control, an unexpected, controlledaccidental element enters. Many times it can add a lot, and it is the most exciting m o m e n t always — t h e opening of the kiln. Do I consider myself an artist, or a craftsman? I do not think you can call somebody an artist because he or she paints, sculpts, or makes pots. Artist is a qualitative term; an artist is a poet in his or her medium. Someone w h o produces a good piece that contains some mystery, a quality inexpressible by words, is an artist. Working w i t h clay is a great joy for me. Both the work process and the final, com-

79

pleted piece make me happy. I like also to teach; I think teaching can be an art, too. The hardest part is to teach a beginner. But in another sense it is also easy because beginners

80

are not formed yet; Jthey are free. We must teach them to see, to experience, to touch, and to get involved in and excited by the medium and the material. Only this way, with

their own interest and their own effort, can they develop themselves. In art you can give guidance only. You can teach technique, but technique alone is not art.

YUME 1970 82

Stoneware, 18.5" Honolulu Academy of Arts

NIGHT

FORMS

1974 S t o n e w a r e plaque, 1 2 " x 1 2 " Collection of t h e artist

(Photo by Tom

Haar)

83

Reuben Tarn

Born 17 January 1916, Kapaa, Hawaii. University of Hawaii, 1933-38; graduate study, Columbia University, New School. Instructor, Brooklyn Museum Art School; professor, Queens College, Oregon State University; Guggenheim Fellow; lecturer on art. In Who's Who in America. One-man shows (26 from 1940): Honolulu Academy of Arts; California Palace of the Legion of Honor; Portland Museum; Wichita Art Association: University of Nebraska; Philadelphia Art Alliance; Coe Kerr Gallery, N.Y.C.; and others. Public collections (35): Museum of Modern Art; Metropolitan Museum; Smithsonian Institution; Whitney Museum; Brooklyn Museum; Des Moines Art Center; Dallas Museum; Newark Museum; Tel Aviv Museum; State Foundation on Culture and the Arts; Universities of Illinois, Nebraska, and Michigan; and others.

My life as an artist in New York City, and the ideas and interests and the search that propel and inform my w o r k , all have their beginnings in Hawaii. Growing up on Kauai gave me an abiding sense of place that was to chart my life as a landscape painter. My hometown, Kapaa, lying on the coastal plain between the reef-shadowed bay and the foothills of Nonou, is sand country that is edged w i t h the red of the weathering upland. Beyond the red plateau is a great landscape of mountains, cliffs, gulches, valleys, rivers, falls, rain forests, rain-

bows, sun-in-rain, and even a surreal Sleeping Giant. School, a mile from home, stood on a very high hill overlooking the sea. From the summit, on clear days, w e could see Oahu. I grew into an awareness of the vastness of oceanic space, distances that harbored other islands and other coastlines. From the ocean sprang squalls that w o u l d pelt the hillside and create new raw gullies at our very feet. W e witnessed erosion, not in terms of textbook eons, but as instant geology. On a grander scale w e could see Waialeale, baring its serrated crest in those rare moments w h e n the layers of cumulus would part. W h e n w e learned that this mountain was the wettest spot on earth, w e felt a sense of pride, as if to be told that the gods of the elements had chosen our island for their home. On the dry leeward side of the island one could see from the dunes of Mana the oldest islands of the a r c h i p e l a g o - K a u l a , Niihau, and Lehua —rising dimly from the long horizon, hinting at still earlier islands, n o w only submerged shoals and atolls. One acquired a sense of geologic time —an awareness of land as dynamic presence, ephemeral entity, omnipotent, mystical, and beautiful. This was my heritage: the spirit of place. I began a landscape painter's life of the pursuit of place, first of the shores of home, the mountains and headlands of north Kauai, and then of the other islands.

My growing curiosity of the geography of places across the sea eventually led me to the northern California coast, to Cape Cod, the coast of Maine, the Nova Scotia region, the Canadian Rockies, the coast of Alaska and the Yukon, and to the coastline and lava fields of Oregon. Each place has its o w n geomorphology, and I look upon these landscapes as variations of the earth's crust, w i t h the Hawaiian Islands providing the basic vocabulary of landforms through which other earth structures can be perceived and understood. One place was especially fascinating to me —Monhegan Island, fifteen miles off the Maine coast. Here I built a studio home, and here my wife and I spend four or five months every year. The spruce forests, headlands, and tides of this island have been major subject matter in my work for more than twenty years. The confluence of Atlantic w i n d and ocean currents and the processes of the weathering of rocky promontories provide the basic theme, but unlike the rich, warm, red and burnt sienna colors of Hawaii, here it is cold gray gneiss and granite. The sky can be opaque w i t h fog for weeks on end, and your palette runs to Payne's gray and lots of white for fog, sea, and spindrift. Last summer, from my island in Maine, I found the nebula of Andromeda in the northeast sky, its configuration like a swirl of reefs in the sea. It was an astounding visual and emotional experience for me, and it seemed as

85

if things had come full circle with me, because many years ago when I first saw an obscure reef at Wailua in the pale evening light, the coral heads, lava rocks, and flotsam were spinning in the eddies and swirling like magical stars. Someday I'll try to paint Andromeda. Over the years I've painted many oils of reefs; one of them, "From Reefs to Morning," celebrates a morning at Wailua, and several recent paintings, called "Island Endings," are about Monhegan's low-tide ledges. I've painted Anahola Mountain in several large oils and many small acrylic watercolors on paper. That mountain is becoming my favorite subject, so

86

grand is its display of the geologic processes that formed the islands. Through my work I want to say: Look at this earth of ours. It's ours to know and enjoy. Don't take it for granted. It isn't just background. It isn't just scenery. And don't despoil it. Each time I return to Hawaii I am struck anew by the enormity of this theme of earth. I am numbed by its immediacy. I am challenged by the myriad possibilities for composition and re-presentation in paintings, and by the multiplicity of motifs. The last time I was there I focused on the lava flows on the slopes of Mauna Kea, the incredible phenomenon of

Haleakala with its rifts, cones, and aa outcroppings, and the grand spread of landscape forms of Kauai, from the swift vertically of Hanakapiai to the gentle streams of Kawaihau. And someday I'd like to do a painting of the redness of Moloaa. As a New Yorker, I have lived in what is the art center of the w o r l d — a stimulating and enriching world, its vitality crackling in explosions of styles, modes, dogma, politics, and quick changes. But I derive more stimulus for my work from that other world, where change means the cycles of weather, and style is the look of the land.

THE FAULTING 1966 Oil, 48" x 52" Collection of the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts

THE LA VA AGES

OF

KAUAI

1975 Oil, 4 4 " x 5 0 " Coe Kerr Gallery, N e w Y o r k City

Photo

by Tom

Haar)

Jean Williams

Born 10 September 1916, Honolulu, Hawaii. Lecturer in art, Univ. of Hawaii, 1965-73; special project in art, Univ. of Hawaii, 1975; workshops, all islands, 1967-75; Hawaii D.O.E. Artmobile, 1974; weaving instructor, Bishop Museum 1970-, Honolulu Community College, 1976. One-man shows: Honolulu Academy of Arts, 1970; Contemporary Arts Center of Hawaii, 1976. Invitationals (1966-73): Fullerton Jr. College; Florida State Fine Arts; Hawaii-50th State, Atlanta; Wichita National; The Excellence of the Object, American Craftsmen's Council; Univ. of Northern Illinois; Univ. of New Mexico Art Museum. Permanent collections: State Foundation on Culture and the Arts; Honolulu Academy of Arts; Wichita Art Museum; Museum of Contemporary Crafts, New York.

I got started in weaving a long time ago. My husband was in the military and was being transferred to Japan in April of 1950. I was to follow with the children as soon as a place could be provided for us to live. But the Korean conflict changed all that. Not knowing how long I was going to be alone made me very depressed. Going back to school seemed