The Vortex That Unites Us: Versions of Totality in Russian Literature 9781501769405

The Vortex That Unites Us is a study of totality in Russian literature, from the foundation of the modern Russian state

121 60 1MB

English Pages 228 Year 2023

Contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction: The Totalities of Russian Literature

1. Versions of Possession: Ghost, Demon, Idea, Discourse

2. The Epidemic: The Infectious Imagination of Leo Tolstoy

3. The Panorama: World Literature and Universal Language

4. The Orchestra: Dictation and Dictatorship

5. The Market: Humbert Humbert as Mad Man

Afterword

Notes

Index

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Jacob Emery

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

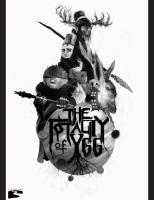

THE VORTEX THAT UNITES US

A volume in the NIU Series in

Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies Edited by Christine D. Worobec For a list of books in the series, visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu.

THE VORTEX THAT UNITES US

V E R S I O N S O F TOTA L I T Y I N R U SS I A N L I TE RAT U R E

J acob E mery

NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY PRESS AN IMPRINT OF CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS Ithaca and London

Copyright © 2023 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. First published 2023 by Cornell University Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Emery, Jacob, 1977– author. Title: The vortex that unites us : versions of totality in Russian literature / Jacob Emery. Description: Ithaca [New York] : Northern Illinois University Press, an imprint of Cornell University Press, 2023. | Series: NIU series in Slavic, East European, and Eurasian studies | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2022048218 (print) | LCCN 2022048219 (ebook) | ISBN 9781501769382 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781501769399 (epub) | ISBN 9781501769405 (pdf ) Subjects: LCSH: Russian literature—Themes, motives. | Russian literature—History and criticism. | Whole and parts (Philosophy) in literature. | Ideology in literature. Classification: LCC PG2986 E64 2023 (print) | LCC PG2986 (ebook) | DDC 891.709—dc23/eng/ 20221121 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022048218 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/20220 48219

C o n te n ts

Acknowledgments vii

Introduction: The Totalities of Russian Literature

1

1. Versions of Possession: Ghost, Demon, Idea, Discourse

22

2. The Epidemic: The Infectious Imagination of Leo Tolstoy

59

3. The Panorama: World Literature and Universal Language

84

4. The Orchestra: Dictation and Dictatorship 115 5. The Market: Humbert Humbert as Mad Man

141

Afterword

168

Notes 171 Index 207

A ck n o w le d gm e n ts

Chapter 1 includes parts of several previously published articles, which have been substantially reworked and mixed in with new material: “Repetition and Exchange in Legitimizing Empire: Konstantin Batiushkov’s Scandinavian Corpus” (Russian Review, October 2007); “Between Fiction and Physiology: Brain Fever in The Brothers Karamazov and Its English Afterlife,” written with Elizabeth F. Geballe (PMLA, October 2020); “Sigizmund Krzhizhanovksy’s Poetics of Passivity” (Russian Review, January 2017), and “A Clone Playing Craps Will Never Abolish Chance: Randomness and Fatality in Vladimir Sorokin’s Clone Fictions” (Science Fiction Studies, July 2014). A partial version of chapter 2 was previously published as “Art Is Inoculation: The Infectious Imagination of Leo Tolstoy” (Russian Review, October 2011). A partial version of chapter 4 was previously published as “Keeping Time: Reading and Writing in Conversation about Dante” (Slavic Review, Fall 2014). And a partial version of chapter 5 was previously published as “Humbert Humbert as Mad Man: Art and Advertising in Lolita” (Studies in the Novel, Winter 2019). I am grateful to those journals for permission to reuse this material and to their editors, staff, and peer reviewers for improvements made along the way. I would like to thank Amy Farranto and everyone at Northern Illinois/ Cornell University Press, including the anonymous reviewers, for helping shepherd this book to press; my mentors—Julie Buckler, Tomislav Longinović, Stephanie Sandler, Marc Shell, William Mills Todd III, Justin Weir, and my late advisor Svetlana Boym—for their patience and support; my colleagues at Indiana University, especially Elizabeth F. Geballe, Herbert Marks, Eyal Peretz, and Russell Valentino, who provided stimulating discussions and penetrating critiques throughout the writing of this book; Alex Berg, Ian Chesley, Rebecca Cravens, David Damrosch, Caryl Emerson, Ilya Kun, Natalia Kun, Robert Latham, Mark Lipovetsky, Ainsley Morse, Eric Naiman, Nariman Skakov, Alexander Spektor, Dennis Yi Tenen, and Julia Vaingurt, each of whom improved this book through some combination of comments, conversation, and intellectual generosity; Ilya Bendersky, David Gramling, Olga Hasty, Colleen McQuillen, Harsha Ram, and Tatiana Venediktova, who invited me to share early vii

vi i i

A c k n ow le d g m e n ts

versions of this work at the Tolstoy Museum, the ACLA meeting at New York University, Princeton University, the University of Illinois at Chicago, the University of California at Berkeley, and the Moscow State University Summer School in the Humanities; and the audiences at t hose talks for their attention and response. This work was partially funded by the Davis Center at Harvard University, Indiana University’s College Arts and Humanities Institute and Russian and East European Institute, and by Indiana University Research through the Grant-in-Aid Program, all of which provided material support at various stages. Thanks as ever to my students, my apologies to everyone I have forgotten in this all-too-brief list, and one final thank-you to Amy and Otis, whom I never forget.

THE VORTEX THAT UNITES US

Introduction The Totalities of Russian Literature

One thing that distinguishes art from other forms of knowledge is that an artwork’s formal features mark it off as a complete object from the larger world that it represents or even, paradoxically, seeks to contain. The philosopher Bruno Latour has decried the metaphoric frameworks he calls “panoramas”—capacious interpretive paradigms such as “modernity” or “globalization”—as false totalities that give up nuance and accuracy for scope and simplicity.1 Whatever the value of this attitude in the social sciences, it is simply not relevant to the totalities represented in and by aesthetic objects. The avant-garde poet Velimir Khlebnikov’s 1920 poem “The One, the Only Book” depicts the whole world as a vast text, with rivers laid across the landmasses like threads “marking the place / Where the reader rests his gaze.”2 From this panoramic perspective, all the planet’s regions and its people—“Race of Humanity, Reader of the Book”—are united by their inclusion in the sacred volume of creation “whose cover bears the creator’s signature / The sky-blue letters of my name.”3 The world appears h ere as a version of Khlebnikov’s own oeuvre and its persistent efforts to discover the master rhythm of history, to identify a vantage point from which to take in all the earth, and to forge the universal language of concepts that Khlebnikov proposes in his manifestoes and grasps at in his poetic practice: “the new vortex that unites us, the new integrator of the human race.”4

1

2 I n t r o d u c t i o n

Innovative and idiosyncratic as Khlebnikov’s project is, it belongs to an extensive tradition of texts that swell from totalizing metaphors of a literary cosmos. In the culminating image of Dante’s Divine Comedy, the narrator attains to the pinnacle of heaven, where he achieves a similar metafictional vision of “the scattered leaves of all the universe / bound with God’s love into a single book.”5 Here, too, the commonplace metaphor of the total book represents the universe as a utopian totality gathered together in a meaningful pattern by a transcendent power; in the same stroke, Dante makes a grandiose claim that the poetic text before us is commensurate with all of creation. Of course, contemporary audiences are unlikely to extend any more literal truth value to The Divine Comedy’s cosmology than they do to Khlebnikov’s assertion that he is the author of existence. In both cases, the poem’s panoramic ambitions are compelling primarily because they speak to a claim to gather the world, if only by means of allegory, into the self-enclosed totality of the artwork. In this book, I offer a conceptual anthologizing of the Russian canon through the theme of totality. I do not pretend to exhaust the theme of totality in Russian-language literature; the “One State” of Eugene Zamiatin’s dystopian novel We, to name just one prominent example, is absent from the following chapters. Nor do I desire to reduce totality’s many manifestations across the longue durée of Russian culture to a single claim about Russia’s essential character or historical destiny, although I discuss numerous claims of the sort as they crop up in the following pages. Still less do I argue that Rus sian totalities are somehow more total than universalizing ideologies originating elsewhere, such as Christianity or positivism.6 Rather, I am interested precisely in Russian literature’s teeming and paradoxical diversity of totalities. This book treats in turn a poetics of possession (in authors who sketch out a historical trajectory running loosely from Russian Imperial Romanticism to post-Soviet postmodern fiction); the all-encompassing emotional community implied by Leo Tolstoy’s epidemic metaphor of artistic experience as an “infection”; the panoramic text of the world envisioned by Khlebnikov and other representatives of the early Soviet avant-garde; the continuous cultural tradition that is guaranteed, in the writings of the dissident poet Osip Mandelstam, by the orchestral metaphor of a common time enforced by the conductor’s baton; and the global market for cultural goods in the English-language writing of Vladimir Nabokov, whose fictional worlds, capable of both giving plea sure and entrapping unwary victims, come uncannily to mimic the logic of totalitarian regimes. The stakes and orientation of art’s totalizing dimension shift radically across these texts and the distinct historical moments in which they originate. Despite these diverse guises and ideological thrusts, a recurrent set of intertex-

Introduction

3

tual references, cultural touchstones, and theoretical concepts link t hese texts and my readings. Aspirations to aesthetic totality become readily allied with other totalizing intellectual currents such as the totalitarian state, Enlightenment reason, globalization, or Christian universalism. Literary texts propagandize such discourses, of course, but it is more essential that totalizing ideologies find analogues in literary form. A humanity united in and transfigured by art is a central feature of utopian aesthetics since at least the French Revolution, whose democratic ideals and transformative potential inspired Friedrich Schiller’s Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man. Schiller’s book describes “the realm of aesthetic semblance” through a series of political meta phors, casting the artistic impulse as an “executive power” whose jurisdiction includes all of human experience, from unconscious physiological response (the “blind compulsion” of natural impulse) to self-aware rational intent (“the point where reason governs”).7 Despite Schiller’s egalitarian ideals, interpretations of the aesthetic as an irresistible force communicated through the artist and welding the audience into a single unit governed by a single visionary conception can carry fascistic implications. A persistent formation that constitutes an important through line in this book triangulates political organization with artistic genius and aesthetic response. In this scheme, an inspiration that partakes at once of artistic vision and utopian politics descends on and possesses the artist, who manifests that impulse in an artwork; the public, falling u nder the artwork’s spell, is moved to share in a common experience that implies a community of feeling. In the formation of this ambiguously poetic and political totality, we can discern two complementary movements that work together to bind discrete elements (whether words or persons) into a whole (whether a text or a polity). On the one hand, totality requires some expansive mechanism that spreads through space and time, a principle of transmission made manifest as imperial conquest, infectious spread, textual dissemination, or commercial networks of exchange. On the other hand, totality requires some unifying principle that gives shape to artistic material and compels e very element that falls into its field of force to articulate the pattern that it perpetuates and universalizes: artistic genius, ghostly possession, literary tradition, or totalitarian authority. Harsha Ram has identified both movements in Khlebnikov’s work, which vacillates between the two “equally utopian impulses” of “outward expansion, from the erasure of national boundaries to the final goal of planetary liberation,” and of “closure . . . an impregnable island ruled by a ‘laboratory for the study of time.’ ”8 A similar opposition underlies Vladimir Papernyi’s hypothesis—itself a totalizing narrative that encompasses Russian cultural history in a self-perpetuating cyclical logic—that Russian culture alternates between the expansive and egalitarian

4 I n t r o d u c t i o n

“Culture One” and the centralizing and hierarchical “Culture Two.”9 The emblem of the latter is Boris Iofan’s plan for the Palace of Soviets, a massive “perfect architectural construction,” capped by a three-hundred-foot-tall statue of Lenin, that was to bring about the culmination of architecture itself, “so that in the future t here would be only endless reproductions of this model.” In Papernyi’s analysis, the Stalinist skyscrapers that ring the proposed site of this unbuilt structure are earthly echoes of an ideal image but at the same time harbingers of a return to Culture One, since the shift in emphasis “from the planning of this model to its multiplication” means “the decline of hierarchy and a return to horizontal expansion.”10 In the more abstract terms popularized by Roman Jakobson, we might think of t hese two impulses as the “metonymic axis,” involving relationships of contiguity and causality, and the “metaphoric axis” of similarity and identity.11 Like Papernyi, Jakobson sees cultural history as oscillating between these two poles: thus, the realist novel, essentially metonymic in its linked plot events and plethora of ancillary details, follows on a Romantic literat ure of allegory and is itself succeeded by the explicitly metaphorical Symbolist movement.12 He acknowledges that both processes are always at work, however, and suggests that literat ure is the result of their patterned interaction. An essay by Gérard Genette, which decomposes the g rand synthetic images that encapsulate Marcel Proust’s aesthetic project into the intricate systems of coincidence that motivate them, illustrates how the one principle gives rise to the other. “It is metaphor that recovers Lost Time,” Genette concludes, “but it is metonymy that reanimates it, sets it in motion, which delivers it to itself.”13 Following Genette, Paul de Man has suggested that any passage that is “ordered around a central, unifying metaphor” can be analyzed into a set of transfers and juxtapositions.14 “The inference of identity and totality that is constitutive of meta phor is lacking in the purely relational metonymic contact,” de Man points out, and yet upon close inspection, “the assertion of the mastery of metaphor over metonymy owes its persuasive power to the use of metonymic structures” through which a unified pattern comes to dominate the entire text.15 A literary totality thus emerges from a collocation of individual transfers, each one communicating an impulse that binds the myriad atoms of the text together into a coherent form. This originary impulse is readily imagined as an essentially citational authority, akin to past usage or l egal precedent, whose force determines the meaning of words and application of laws in the present moment. In authors’ aspiration to write a total text, they seem to echo another, prior utterance—a “voice which traverses them without belonging to them,” in Avital Ronell’s phrase.16 Because this animating genius remains ex-

Introduction

5

ternal to the artwork it inspires, totality is close to the Gothic and elegiac modes in which the trace of a lost origin haunts the present. The inspiration visited on Romantic poets as they wander country churchyards and contemplate ruins reflects this understanding of cultural authority. So do Soviet materialist conceptions of capital as “dead labor, which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labor”: this formula, from the pen of Karl Marx, manifests the Gothic scheme as a structure of economic and political alienation.17 Even texts that seem to oppose centralized authority conjure up some compensatory figure that promises to bind the text, and the totality of culture, into a w hole. The dissident martyr Osip Mandelstam’s last essay, Conversation about Dante, likens culture to a flock of birds that has settled down on grain strewn in the shapes of letters, so that they collectively spell out a preexisting text that none of them individually intends or understands. In Mandelstam’s conception, a writer is like a “scribe who is obedient to the dictation” of a transcendent force that is interpretable as poetic inspiration but also as political tyranny.18 (The poet disappeared into Stalin’s camps not long a fter he wrote these words.) In a 2000 book subjected to a public desecration and legal persecution by allies of Vladimir Putin, Vladimir Sorokin evokes a similar scene: a multitude of torchbearers floating down a river, disposed so as to spell out a propaganda message in letters of fire for the audience gathered on the embankments.19 Casting human bodies as an artistic or quasi-artistic medium, such images allude to an avant-garde aspiration to work not in representations but in the material of life itself. As the 1913 Futurist manifesto “Why We Paint Ourselves” proclaims, “We have joined art to life. . . . Life has invaded art, it is time for art to invade life.”20 By annulling the boundary between life and art, the w hole world was in this view to become subject to the dynamic, creative process that radical artists called zhiznetvorchestvo, or “life creation.” In Boris Groys’s intentionally provocative account, the avant-garde mind-set was internalized by the Soviet leadership, which became “a kind of artist whose material was the entire world.”21 “Mankind w ill educate itself plastically, it w ill become accustomed to look at the world as submissive clay for sculpting the most perfect forms of life,” writes Leon Trotsky in his Literature and Revolution.22 In a striking illustration of the tendency that Groys calls the “total art of Stalin [Gesamtkunstwerk Stalin],” Trotsksy projects that “the entire economic, social, and everyday life of the nation” was to be “subordinated to a single planning authority commissioned to regulate, harmonize, and create a single w hole out of even the most minute details”—the fulfillment, on the grandest possible canvas, of an aesthetic ideal, into whose vortex life and art alike were to be drawn.23

6 I n t r o d u c t i o n

From Point of Origin to Point of Sale The seminal literary instance of “life creation” is the opening sequence of Alexander Pushkin’s 1833 poem The Bronze Horseman, which mythologizes Rus sia’s passage from provincial backwater to global modernity through Peter the Great’s foundation of a new capital on the shores of the Baltic. For Groys, the scene is the locus classicus of Russian totalitarianism and codifies its “myth of the demiurge, the transformer of society and the universe.”24 In the poem’s iconic first lines, the tsar stands “on the shore of the desolate waves [pustynnykh voln]” where he intends to build the city that will bear his name.25 In the lack of distinction between land and w ater, the gloomy chaos of moss and fog suggests the uncreated world at the opening of Genesis, “without form, and void [pustoi]”; it is the godlike tsar who is “full of sublime thoughts [dum velikikh poln],” pregnant with the city that he will make to “rise from the mire” on this spot.26 Created with a word of command resembling the divine performative “let t here be light,” Peter’s brilliant new capital is the product of a language that does not just represent but makes the world. The mythopoetic word of the tsar is at once aesthetic and political—the creation of a luminously beautiful thing and the exercise of authoritarian power. In the main plot of Pushkin’s poem, a statue of the tsar seems to become animated and to persecute the lowly clerk who dares to defy his legacy; Petersburg and its inhabitants are haunted by the tsar’s implacable ghost, which compels them to live according to his tyrannical vision. Peter’s center of empire is paradoxically situated on that empire’s margins, on land recently seized from Russia’s “haughty neighbor” Sweden. The native Finnish fisherman, “the sad stepchild of nature,” is silently effaced in favor of the Russians, who are apparently nature’s true inheritors.27 When the boom of the ice breaking up in the river during the spring thaw joins with the boom of the cannon from the Petropavolvsk fortress to celebrate “the gift of a son to the house of the tsar / Or a victory over the enemy,” the principle of filiation and the natural world’s benediction of Russia’s imperial designs are plain.28 The idea that the tsar has imposed his creative vision onto the blank slate of nature gives way to images suggesting that Peter is himself an instrument of nature or of some historical destiny that nature represents. On this inauspicious spot, “Nature . . . has fated us,” Peter muses, “to cut a window onto Eu rope.”29 These lines, as well known as any in Pushkin’s oeuvre, clash with the divine performative “let there be light.” The architectural metaphor implies that light is not created by fiat but is accessed by opening a window onto the West and its Enlightenment culture, commensurate with the physical trade routes that are to integrate Russia into the global economy. “Every nation’s

Introduction

7

flag will visit” the “new waves” leading to this new city, the poem prophesies; the landlocked empire’s newly established port w ill attract and organize the universe around it, so that “ships / in a mass from every end of the earth / stream to our rich wharfs.”30 St. Petersburg is an emblem of centralized imperial power, achieved through the compulsive vision we have identified with metaphoric totality, but at the same time it represents Russia’s integration into, even subjection to, the expansive historical forces that spread modernity and revolution around the globe. These tropes, and the tension between them, are not original to Pushkin. He draws on commonplaces already established by Mikhail Lomonosov in his 1761 “Peter the G reat: A Heroic Poem,” which repeatedly depicts the tsar on a foggy shore devising some visionary infrastructure project, and in a 1755 panegyric that praises Peter for opening the gates of Russia onto the “ebb and flow of the expansive Ocean” to let in commerce, arts, and science.31 “The expansive Rus sian state, in this resembling the world as a whole, is practically surrounded by great seas,” writes Lomonosov, whose “waves groan beneath the weight of the Russian fleet” as Russian flags disperse on voyages of colonial exploration.32 Konstantin Batiushkov, in his 1814 “Walk to the Academy of Arts,” painted a similar scene of a silent, swampy “desolation [pustynia]” in which Peter “spoke— and Petersburg rose out of the wild swamp,” a “wonder” of civilization destined to “overcome nature itself ” and gather to its bosom a cosmopolitan “mixture of all nations.”33 According to the semiotician Yuri Lotman, Petersburg has since its foundation served as a “culture generator,” in which “different national, social and stylistic codes and texts confront each other” across centuries of Russian history: autocracy and freedom, Russia and the West, center and periphery, nature and culture, primordial water and hewn stone, a “utopian ideal city of the future” and yet “the terrible masquerade of the Antichrist.”34 Russia’s window onto Enlightenment humanism and secular rationality is at the same time a signal instance of Russia’s brutal history of forced l abor, a fragile capital of the uncanny built by serfs and enslaved prisoners of war at terrific h uman cost. Marshall Berman describes St. Petersburg as the inaugural scene of peripheral modernity—a partial integration into the protean flux of capitalism, whose attendant inequalities and incitements have become our common condition across the planet.35 According to Nikolai Gogol’s own (very suspect) testimony, the plot of his 1842 satire Dead Souls, another seminal work from the formative period of modern Russian literature, originated with Pushkin, who donated it to him as a sort of sacred trust.36 This monstrously funny picaresque novel, about a con man buying up the titles to deceased serfs in order to mortgage them for their paper value and invest the funds in real estate, stages a very different intersection of

8 I n t r o d u c t i o n

global commerce and national destiny. It was to be the opening salvo of a national epic whose three projected volumes, modeled a fter the three parts of Dante’s Divine Comedy, would deliver Russia from the hell of serfdom through a purgatory of self-reflection and into a paradisiacal destiny. The project can be seen as one episode in the history of art’s effort, over the course of the nineteenth century, to take religion’s place as the unifying force of European culture. In a central scene, the novel’s antihero, Chichikov, reads through the bills of sale for dead serfs and, carried away by a sort of inspiration, begins to paint verbal pictures resurrecting them. In his reverie, he imagines a runaway who has found work as a Volga barge hauler and breathlessly evokes the stevedores who “noisily pour peas and wheat into the deep vessels, pile up sacks of oats and groats”— the collective produce of Russia, gathered with the melting of the spring ice and hauled away to global markets.37 “All as one,” Chichikov apostrophizes this phantasmal mass of workers, “you’ll buckle down to toil and sweat, pulling the rope to the strain of a single song endless as Rus.”38 The barge that gathers together Russia’s wealth is a microcosm of the nation as a w hole; the “single song endless as Rus,” to whose rhythm Russia moves through slavery and corruption to its salvific destiny, is its artistic analogue and a metaphor for Gogol’s own novel. For the nineteenth-century ethnographic critic Alexander Veselovsky, the popular chorus was a spontaneous collective expression, whose dissolution into distinct genres like the epic and lyric was a symptom of society’s fragmentation into distinct classes.39 In the triumphal final scene of Gogol’s novel, the fraudster’s carriage becomes assimilated to this collective song. Chichikov’s three speeding horses, which “have heard from on high the familiar song,” are compared to the Christian trinity and to the “divine miracle” that is Russia’s destiny.40 The spiritual cargo of “souls” that the carriage conveys to the afterlife replaces the material cargo of peas and buckwheat that the barge carries to foreign markets; the millenarian hymn from on high replaces the work song of the laboring masses. Described as a “wind” by which Russia is “all-inspired by God,” this “song from on high” draws on commonplaces of the soul as an animating breath blown into m atter. Its “inapprehensible mysterious force [tainaia sila]” expresses Russia’s “unembraceable space,” in which a “boundless thought is destined to be born” that will paradoxically “embrace” the narrator himself: “reflecting itself with terrible force in my very depths; by an unnatural power [neestesvenoi vlast’iu] have my eyes been illumined.”41 This illumination is different in kind from that offered by Enlightenment reason. By claiming to “reflect” the supernatural totality of this song in the depths of his own self, the narrator audaciously represents Dead Souls to its reader as a spiritual vessel transporting the nation to salvation.

Introduction

9

The introduction to the 1940 edition of Gogol’s collected works admires the author’s “tremendous ability to create works that reflect ‘all of Rus.’ ”42 Over the course of Gogol’s narrative, each financial transaction with another eccentric landowner in the picaresque series that makes up the book is a partial step toward this evocation of “all of Rus.” The deeds of sale accumulating in Chichikov’s ledgers, the barge laden with Russia’s collective produce, the work song of its myriad haulers, the chorus that is a spiritual echo of the work song—all these increasingly bold and spiritualized images, religious, political, economic, and aesthetic, require us to perceive Gogol’s novel as a more perfect member of the same series. A compulsive, utopian, total text emerges from a snowballing cascade of individual transfers. For Georg Lukács, the novel is the literary form that “seeks, by giving form, to uncover and construct the concealed totality” immanent in the fragmentation of modern life, an effort he investigates particularly among the Russians.43 “In order to create a real totality such as Gogol’s authentically epic intention demanded,” Lukács suggests, it would have been necessary to provide a positive counterweight to the satire; this was beyond the author’s powers.44 Overcome with fanatic piety, Gogol burned the manuscript of the second volume of Dead Souls and starved himself to death in penance for writing the first one. The tragic end to the author’s life highlights the stakes of his ambition. In a preface to the first and only published volume of Dead Souls, Gogol styles the work as a collective utterance of the nation. He asks the reader to bring to mind “his entire life and all the p eople with whom he had met, and all the events that had taken place before his eyes, and everything that he had seen for himself or heard from anyone e lse, . . . to describe all this just as it appears in his memory, and to send me e very page as he writes it” for inclusion in f uture installments of an infinitely capacious book.45 Gogol carries on this insane but not wholly facetious invitation for six pages. At first blush a gag in the vein of Laurence Sterne, his jocular proposal that his readership convert their lives into narratives and send them in to be gathered between the covers of a book can also be seen as literalizing the collective utterance set forth in the imagery of the barge hauler’s song, the millenarian hymn, or indeed the ownership deeds gathered in Chichikov’s portfolio.46 These universal texts produced by a collective author are the counterpart to a collective readership like the one imagined by Vissarion Belinsky in his famous open letter admonishing Gogol’s turn to religious conservatism. “I do not represent a single person in this respect but a multitude of men, most of whom neither you nor I have ever set eyes on, and who, in their turn, have never set eyes on you,” warns Belinsky, echoing his long-standing conviction that a Russian public would discover itself as “something unified, a single living personality

10 I n t r o d u c t i o n

developing historically” through its encounter with its reflection in Russian liter ature.47 Belinsky’s Hegelian notion of a people becoming a unity by internalizing its represented image persists in statements of the Bolshevik period. Anatoly Lunacharsky, the first Soviet commissar of education, announced in the article “On the P eople’s Festivals” that if the “masses” w ere to achieve consciousness, they must “become a spectacle for themselves.”48 The ideal was put into practice, at least in an embryonic form, by Alexander Medvedkin’s “cinema train,” a traveling film studio that shot footage of workers in the morning, edited it in the afternoon, and screened the completed film in the evening in the mess hall.49 In this ideal circuit of production and consumption, the workers who starred in the film were at the same time the market that consumed it.

A Braid of Totalities In The Bronze Horseman and Dead Souls, major works by the two towering figures of the golden age of Russian literature, totalizing figures spread across frontiers and guarantee the coherence of the globe; they reshape the f uture in the image of an inexorable destiny and ensure the continuity of history. Received wisdom, often an Orientalist received wisdom, has long foregrounded a totalizing element in Russian culture more generally.50 Russia’s political traditions are steeped in tyranny; its intellectual history is studded with visions of planetary socialism, universal language, and cosmic conquest. Even the canonical realists, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, instill their texts with grandiose suggestions of final judgment or emotional collective: Dostoevsky speaks passionately of “Russia’s striving toward its ultimate goals of worldwide and international universality,” Tolstoy of art “uniting all the most varied men in one feeling” and making sensible an “eternal and infinite harmony.”51 Alongside Groys’s “total art,” we can readily find scholarly accounts of a “global ethic,” a “universal siblinghood,” or a culture that “saw itself as the inheritor of all the traditions of mankind” and “wanted to possess everything.”52 Again, my objective is not to argue for any one of these ideologies, and my readings are meant to be exemplary rather than exhaustive. Still, it may be useful at the outset to rehearse in brief several distinct but interweaving traditions of totality that are sustained across t hese centuries of literature and to note their points of relevance to the authors whom I treat in detail in the chapters that follow. One of the most formidable of these totalizing traditions descends from the previously discussed myth of St. Petersburg, founded by imperial fiat on a swampland recently wrested from the Swedish Empire and symbolizing the inauguration of the modern autocratic state. James Billington connects

Introduction

11

St. Petersburg’s geometric grids of streets and canals to a fantasy of comprehensive Enlightenment rationality and cites a 1694 poem on geometry by Peter the Great’s childhood tutor, Karion Istomin: “geometry has appeared, / land surveying encompasses everything. / Nothing on earth lies beyond measure ment.”53 The menacing aspect of cartography’s alliance with state power is evident in a quip made by Vladimir Putin, a baldly imperialist ruler who has styled himself as Peter’s successor, as he presided over a 2016 awards ceremony at the Russian Geog raphical Society: “Russia’s borders never end!”54 Andrei Bely’s 1913 novel Petersburg, which contains an elaborate restaging of Pushkin’s Bronze Horseman, describes St. Petersburg as an emanation of its founder’s brain— an abstract idea spreading endlessly through real matter, so that “the entire spherical surface of the planet should be embraced, as in serpent coils, by blackish gray cubes of houses.”55 The idea of a blank globe populated by angular geometry is central to avant-garde practices like the Suprematist painting of Kazimir Malevich, whose squares and triangles can be read as images of a utopian f uture world that has transcended organic forms. In the 1836 Apology of a Madman, Pushkin’s friend Petr Chaadaev describes Russia in similar terms as a “blank sheet of paper” on which Peter I inscribes the name of “Europe and the West,” thereby creating a Western civilization in an empty space with no history of its own.56 Chaadaev’s Philosophical Letters lays out in detail the mimetic rivalry between Russia and the West. Since Russia has been “isolated . . . from the universal development of humanity,” Chaadaev argues, it must cleave to the example of Europe, whose civilization is “animated by the vivifying principle of unity”; by emulating the historical development of the West, Russia w ill participate in its millenarian end, at which “all hearts and minds will constitute but one feeling and one thought, and all the walls which separate peoples and communions will fall to the ground.”57 Anticipating elements of Vladimir Lenin’s theory that colonial expansion inaugurates a “world system” of exploitation and hence a genuinely global chapter in human history, Chaadaev perceives imperialism as an ultimately progressive force, insofar as it gathers peripheral nations into this one stream of events.58 The spread of Enlightenment rationalism is in Chaadaev’s view fundamentally mystical; its “divine origin” is indicated precisely by the “aspect of absolute universality which allows it to penetrate people’s souls, . . . to possess souls without their being aware of it, to dominate them, to subjugate them, even when they most resist it.”59 Chaadaev’s formulas resonate widely in Russian intellectual history and in my own readings. His historical logic, in which submission to an original animating force unites far-flung regions in a single narrative, is central to the ideological construction of a shared identity with the Scandinavian colonies, “fated

12 I n t r o d u c t i o n

by nature” to be the site of the Russian imperial capital. His appreciation for Enlightenment universality coexists with a desire for some spiritual principle in the world beyond the “mechanical force of its own nature”; the same tension is picked up in Dostoevsky’s opposition of neurological and spiritual explanations of h uman consciousness.60 The first entry in Tolstoy’s diary, written in 1847, is consistent with Chaadaev’s conception of a natural law from which individuals and nations fall away when they substitute “artificial reason” for “that portion of universal reason which was imparted to us in the beginning.”61 (Both authors probably derive the idea from Rousseau.) Just as Chaadaev counsels his reader to recognize that “the law which we make for ourselves is derived from the general law of the world,” Tolstoy admonishes himself, “form your reason so that it corresponds with the whole, with the source of all things, and not with the part, with human society; then your reason w ill flow into that same w hole.”62 Chaadaev’s notion of an “initial impulse” that acts on “the whole universality of beings” is one tributary of Mandelstam’s hypothesis of an “impulse [tolchok]” that penetrates into the bodies of writers and readers in order to make Logos sensible as aesthetic experience.63 In Mandelstam’s 1915 essay “Petr Chaadaev,” he links Dante to Chaadaev in their “profound, ineradicable demand for unity,” that “sacred bond and succession of events” that is the synthesizing principle in human history as in poetic texts.64 The same ideas resurface in his last essay, the 1933 Conversation about Dante. Chaadaev valorizes the West as the home of unity, but his embrace of a reason higher than Enlightenment rationality endeared him also to Slavophile thinkers who repudiated the West as a false totality. In a 1923 essay titled “The Tower of Babel and the Confusion of Tongues,” the linguist Nikolai Trubetskoi rails against the Enlightenment’s atomizing analytic logic and insipid internationalism. In the leveling “universal human culture” imagined by Esperantists and communists, he argues, “logic, rational science, and material technology will always prevail over religion, ethics, and aesthetics, so that in this culture the intensive development of science and technology would inevitably be connected to a regression in the spiritual and moral sphere” and w ill lead to a monotonous 65 and static world culture. Trubetskoi’s position is adapted from Dostoevsky’s anti-Enlightenment retelling of the Babel legend, found in the oft-anthologized section of The Brothers Karamazov called “The Legend of the G rand Inquisitor.” Interpretations of this parable w ere frequently colored by Dostoevsky’s programmatic statements on Russia’s destiny to “unite humanity” and “speak the final word of the great, general harmony, of the ultimate brotherly assent of all peoples to the law of Christ’s gospels.”66 The tale became a touchstone in discussions of Russia’s historical telos and its eschatological visions took on a special pertinence in the years just before and after the Russian Revolution. Vasili Roza-

Introduction

13

nov’s influentially reads the “Legend of the Grand Inquisitor” as announcing Russia’s messianic destiny to unite humanity under the mantle of Orthodox faith, whose capacious universalism Rozanov contrasts to Protestant and Catholic efforts to reconcile worldly power and heavenly justice by regularizing relations between church and state.67 True Christianity, for Trubetskoi, is a dynamic “ferment that is introduced into cultures of the most different kind” and does not preclude diverse national expressions within the framework of a common truth: the notable example is Russia’s rejection of Western Enlightenment in favor of its germane brand of Christian mysticism.68 Best remembered as a structural linguist who, together with his collaborator Roman Jakobson, revolutionized phonology, Trubetskoi attempts to reconcile national difference with Christian universalism through a linguistic analogy. He compares a planet united in Christ to a grouping of languages that share common features through their mutual interaction rather than through any genetic link—the so-called linguistic alliance (iazykovoi soiuz), to which linguists typically refer through Trubetskoi’s German calque Sprachbund. His concrete example is the alteration and omission of root vowels, which constitutes a common morphological principle in adjacent but genet ically unrelated languages of the Semitic, Hamitic, northern Caucasian, and Indo-European language families, including Russian. Trubetskoi illustrates this principle through the series “soberiu—sobrat’—sobirat’—sobor,” Russian words derived from a single combination of prefix and root meaning “bring together.”69 The last member in Trubetskoi’s series, sobor, is Russian for “cathedral” and suggests the related sobornost’, a word that in Slavophile writings designates a conception of spiritual community, upheld by conservative thinkers as a model for Russia’s political constitution. As in the Sprachbund, Trubetskoi suggests, the capacious house of God accommodates the various utterances of e very nation without flattening their distinctive traits. Trubetskoi’s series of words that are distinguished by their root vowel recalls sequences in Futurist verse like Vladimir Mayakovsky’s “Grib / Grab’ / Grub / Grob,” which uses vowel alteration to draw together etymologically unrelated words meaning “Mushroom / Steal / Rude / Grave” into a text that generates a meaningful pattern from phonetic coincidence.70 Early essays by Roman Jakobson and Viktor Shklovsky w ere devoted to the incantatory poetic experiments of Velimir Khlebnikov, the greatest master of such phonetic patterning, whose work arguably served as the crucible of Formalist literary theory and then Structuralist phonology. In the Structuralist account, every utterance is pronounced within a common grid of differential phonetic features—providing, as Boris Gasparov has argued, a universal language of linguistic theory that compensates for the lack of a universal language in practice.71 Trubetskoi’s vision of the

14 I n t r o d u c t i o n

universal ethical framework of Christianity can thus be identified with the universal framework of Structuralist linguistics that Trubetskoi helped to devise. The system espoused by Dostoevsky, Rozanov, and Trubetskoi exists on a continuum with the political ideology of Eurasianism, which takes nomadic peoples inhabiting the frictionless expanses of the steppes as a model of international coexistence that would be qualitatively different from the homogenizing positivism of the West. Versions of the idea, often noxious ones, retain currency in Russia’s ethnonationalist political discourse today. The Kremlin apologist Dmitri Trenin, writing in April 2022, not long after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, opposes the culture of the West, which he takes to be imperial or national in character, to the “civilizational state” of Russia, in which “multitudinous ethnicities, cultures, . . . creeds,” and other “elements of diverse origin come together in organic unity and equality,” thanks to the “rigid core and flexible frame” provided by the supervening power of the absolutist state.72 Trubetskoi’s basic framework is here rendered ideological cover for territorial aggression. The Russian avant-garde, frequently primitivist in its orientation, readily accommodated Eurasianist attitudes. Benedikt Livshits’s memoir The One-and- a-Half-Eyed Archer offers as Russian Futurism’s central emblem a steppe warrior at the vanguard of a Scythian horde, “atavistic layers streaming with the blinding light of prehistory,” racing westward “with his face turned backward and with just half an eye squinting at the West.”73 A draft manifesto by Khlebnikov, “An Indo-Russian Union,” asserts, “Our path leads from the unity of Asia to the unity of the stars, and from freedom for the continent to freedom for all of Planet Earth.”74 As this quote implies, Khlebnikov’s fascination with the nomadism of the past is compatible with visions of a liberated f uture humanity undertaking to shape itself and its social and physical environment by science fictional means. For the Futurists, everyday life (byt) was to be overcome by the transformative technologies of modernity, which make h uman life available to the artist as the ultimate medium. A commitment to life creation was perhaps most expansively expressed by the Cosmist philosopher Nikolai Fedorov, for whom humanity’s “common task” of overcoming death and resurrecting everyone who ever lived would necessitate a space program to track down the atoms of our ancestors that had chanced to escape Earth’s orbit. Terraformed planets would accommodate the multitudes of risen dead. “Governed by all the resurrected generations, these worlds w ill be, in their wholeness, the creative work of all generations in their totality, as if of a single artist.”75 For Fedorov, the regathered family of humankind was to realize the Christian community of sobornost’ as a futuristic utopia of immortals, inhabiting the universe that they had rendered a perfect work of art.

Introduction

15

Fedorov’s transhumanist philosophy was widely influential in the avant- garde but also among major cultural figures including Dostoevsky and Tolstoy as well as scientists like Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, innovator of rocketry, hero of Soviet science, and Cosmist visionary in his own right. Tsiolkovsky’s fantasies of an engineered Earth and extraterrestrial colonies w ere readily assimilable to the march of human progress and technological perfectibility cheered on by Soviet ideology.76 The comic writers Ilya Ilf and Evgenii Petrov memorably parodied these cosmic ambitions in their 1928 satire The Twelve Chairs, whose rakish antihero inveigles a Volga backwater to fund a chess tournament that will make the village into the center first of Europe, then the world, and finally “the Universe”: as “chess logic” becomes an “applied science,” the con man projects, it w ill facilitate communication with other worlds and culminate in an “interplanetary chess congress” about eight years hence.77 In a more sober vein, Anatoly Lunacharsky conceives the Soviet economy as an ideal form of poetic activity, whose “task” is to apply the “general laws of artistic taste . . . to a mechanized industry even more colossal than it is now, to the construction of life and the everyday world.”78 Leon Trotsky, in the final utopian pages of his Literature and Revolution, projects a life “saturated with consciousness and planfulness,” in which “Soviet society w ill command nature in its entirety,” razing mountains and moving rivers and transforming even human biology, so that “social construction and psycho-physical self-education” will become the sphere in which “all the vital elements of contemporary art” are brought to their apex.79 Able thanks to genetic engineering and biological manipulation to survive in the ocean deeps and other novel habitats, humanity will accede to its inevitable inheritance of the world as a w hole. The biological metaphor extends to various fantasies of a communist society as a collective body. Alexander Bogdanov, cofounder of the Bolsheviks, espoused mass blood transfusions as a “comradely exchange of life” through which society’s members would share vital resources and resistance to disease; Aleksei Gastev, a proletarian poet and Soviet theorist of labor management, proclaimed a new labor culture to be achieved by “inoculating” workers with the “bacillus” of scientifically organized labor.80 Pronouncements of this kind are fodder for Boris Groys’s aforementioned argument that the avant-garde enthusiasm for infusing art into life was of a piece with the massive construction projects of Joseph Stalin and Peter the Great. Groys’s broad brush homogenizes the complex currents of modernist culture, but the prominent strain in the avant-garde that “claimed universality and the ability to organize the entire world” remains undeniable.81 Futurist artists thrilled to the idea of incorporating space and time into a visionary aesthetic plan. Their academic counterparts, the Formalists, defined art as the subjection of everyday

16 I n t r o d u c t i o n

phenomena to artistic principles of organization, implicating literary theory in the same effort to render life “material for a structure of sounds or a structure of images.”82 In the essay “Government and Rhythm,” Osip Mandelstam compares his poetry to exercises in collective rhythmic gymnastics—an anticipation of a society harmonized on the physiological level by artistic structure or, perhaps, a rehearsal for totalitarian control.83 More cynically, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita makes available the justification that its pedophile narrator’s c areer results in a “work of art.”84 By analogizing Humbert Humbert’s power over his preteen captive with his narrative manipulations and ultimately the author’s own rhetorical power over the reader, Nabokov tests the theory that poetic language is not just abstract representation but an exertion of authorial control over an embodied audience that reacts physically to the text.

The Medium of Totality Across this survey of aggrandizing discourses, the body remains the medium of totality, inspired by artistic vision and controlled by authoritarian w ill. In an essay on the origin of language, the eighteenth-century philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder compares the physiology of our savage ancestors to a musical instrument that, when stimulated by the noise of thunder or the call of a beast, instinctively reproduces the sound.85 This primal “imitation of resounding, acting, stirring nature” becomes the raw material of poetry, gathering “the sounds of the w hole world” into a grandiose “vocabulary of the soul which is simulta neously a mythology and a wonderful epic of the actions and speakings of all beings!”86 Through a natural reflex, the body’s sensory apparatus registers an experience of the world and projects it back out into the world in an integrated and universalized form. Herder’s view of the body as an aesthetic medium that translates the potential totality of nature into the determinate totality of myth is typical of the German philosophical idealism of his day. However, Herder’s scheme also anticipates materialist theories of aesthetic response, in which the stimulation of sensory nerves elicits affective response. “What used to be called, metaphorically, movements of the psyche materialized as circuits of nervous energy and reflex automatism,” writes Ana Hedberg Olenina in her book Psychomotor Aesthetics.87 “New studies revealed vast areas of behaviour that lay beyond conscious control. Feeling, action, thought, and other familiar functions dissolved into neurological mechanisms, and further, into chemical and electrical signals between cells.” She cites an 1863 article by the physiologist Ivan Sechenov, which draws a direct line between the “external manifestations of brain activity that we denote through words such

Introduction

17

as spiritedness, passion, derision, sadness, joy, e tc.” and the “mechanical movements” performed by “the musician’s or the sculptor’s hand creating life.”88 The audience for this art is, by the same logic, a potential collective that might be moved by a common stimulus. In the 1921 book Collective Reflexology, Vladimir Bekhterov assimilated the neurological substratum of social life to Soviet ideologies of mass action. Writing of the “collective personality [kollektivnaia lichnost’]” that forms in crowds, Bekhterov suggests that psychological states are “reflected externally in the changes of the face, gesture, and posture. This movement spreads, reaching other persons and evoking in them the same movements.”89 Bekhterov provides the collective audience imagined by Gogol and Belinsky with a physiological basis. This mechanistic view of art turns out to be curiously compatible with Romantic doctrines of art as an act of genius—a transcendent inspiration that possesses the body of the artist and passes on, through the artwork, to the p eople. The basic model can be traced back at least to Plato’s Ion dialogue, which conceives poetry as a divine force that is communicated from the gods to the poet to the rhapsode to the audience, lessening in intensity but not in kind as it affects an ever-greater number of people.90 Mandelstam alludes to Ion explicitly in his essay Conversation about Dante, which calls for a new science of poetry, a “reflexology of speech,” inspired in part by Bekhterev’s theory.91 In another essay, “Word and Culture,” Mandelstam describes the synesthetic “ringing mold of form which anticipates the written poem” and the transcendental inheritance communicated by “the sound of the inner image, . . . the poet’s ear touching it. . . . In sacred frenzy poets speak the language of all times, all cultures. Nothing is impossible.”92 The manifestoes of the Futurists likewise blur mystical and mechanistic explanations of the artistic impulse, citing religious glossolalia as a precedent for their experiments with the nonsignifying poetic language that they called “zaum,” a neologism that Paul Schmitt has deftly rendered as “beyonsense.”93 According to Aleksei Kruchenykh and Velimir Khlebnikov, an originary impulse distinct from the literal meaning of the words is transmitted through the poetic medium, its sounds or even its written letters. “Our handwriting, distinctively altered by our mood, conveys that mood to the reader indepen dently of the words,” so that “when a piece is copied over, by someone e lse or even by the author himself, that person must reexperience himself during the act of recopying, otherwise the piece loses all the rightful magic that was conferred upon it by handwriting at the moment of its creation, in the ‘wild storm of inspiration.’ ”94 Spanning the origin of the artwork in a poetic tradition and its endpoint in an audience, inspiration and dictation imply a larger aesthetic totality that exceeds any given artwork or artistic experience.

18 I n t r o d u c t i o n

Formalist theorists who worked on zaum cite scientific arguments that “the mimetic or representational aspect of the word has to do with the movement of the organs of speech, as well as accompanying facial and bodily gestures”; since an audience listening to a poem w ill unconsciously mime its pronunciation, even zaum poetry “can contain an element of mimesis.”95 The artistic inspiration that possesses the body of the artist thus corresponds to a symmetrical gesture in which the audience is bodily possessed by the artwork. Since this model takes emotional states to be essentially physiological, “the act of absorbed listening is also an act of empathy, in which the interlocutor is literally being moved.”96 As evidence for the physiological tendency in early Soviet reception studies, Olenina cites Sofia Vysheslavtseva’s call for “a typology of poetic styles based on how intensely they engage the reader’s body” and Sergei Eisenstein’s proposal to record spectators watching close-ups of expressive faces and then to compare the two film reels in order to measure the “contagiousness” of the stimulus.97 The Czech Structuralist Jan Mukařovský theorizes the phenomenon by proposing the body as the ground and medium of aesthetic experience.98 Recent work on “body genres” like melodrama, horror, and pornography, which oblige the consumer to physiologically experience the tears, terror, or tumescence represented in the work, lend suggestive force to t hese ideas.99 Whereas chapters 2–5 of this book treat individual authors or movements, chapter 1 treats the trope of possession across the w hole of modern Russian lit erature, from the early Romantic poetry of Konstantin Batiushkov to the con temporary fiction of Vladimir Sorokin. In Batiushkov’s Scandinavian elegies, the ghosts of Viking skalds dictate verses to their supposed successor, a Russian soldier poet who sojourned in Finland as a member of the occupying Russian Army. The structure of possession, in which the wellspring of Russian poetry seems to be located in the Scandinavian past, is superimposed on the structure of empire, which constructs its capital, St. Petersburg, in the newly acquired territories at its northwestern periphery. In my reading of Dostoevsky’s novels, the demonic figures that visit Ivan Karamazov and Nikolai Stavrogin, which are interpretable e ither as unclean spirits or as hallucinatory symptoms of misfiring nerve cells, mark the conflict between the irreconcilable universalizing ideologies of Orthodox mysticism and Enlightenment reason. A dystopian allegory by the early Soviet writer Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky, in which a global economy is achieved through a transmitter whose wireless signals innervate the muscles of the world proletariat—obliging the workers to carry out a general economic plan despite themselves—probes the limits of the materialist position. Krzhizhanovsky’s larger concern, however, is with the ambitions of art to exert itself on its audience, and his scenario of historical development through totalitarian

Introduction

19

technologies updates the Petersburg myth, in which an idea is imposed by fiat on the material of the world. Finally, in the oeuvre of the postmodern writer Vladimir Sorokin, discourse itself appears in a series of materialized hypostases— cakes of excrement, blocks of ice, lard, or nails—which penetrate into the body and subject it to a hallucinatory experience that partakes at once of the aesthetic and of the political. Sorokin depicts totalizing historical ideologies like Stalinism as mere effects of discourse, which can be mobilized and contained within aesthetic structures. The remaining chapters focus on specific authors and movements across the loosely defined modernist period: Tolstoy, the avant-garde, Mandelstam, and Nabokov. In each case, verbal artworks are analogized with some coercive force that acts on the body. Tolstoy’s aesthetic theory, the major focus of chapter 2, holds that “art is infection” and that “the degree of infectiousness is the only measure of the value of art.”100 Imagining humankind as an epidemiological community that shares a common set of circulating microbes, Tolstoy argues that the spread of infectious diseases restores interconnectedness to a humanity fractured by exploitation. “Illness is given to man as a beneficial indication of the fact that his whole life is bad and that it must be changed,” he writes in his diaries.101 A sick tailor might infect the man who buys a germ-ridden suit, or an ailing chambermaid might pass on germs to those who sleep in the beds she makes. Metaphors of contagion, which run through Tolstoy’s work in every genre, encourage us to reconcile his fictional representations of emotional states with his theory of art’s unifying power. Since artworks are aesthetic vectors that transmit infectious feelings, they offer humanity the opportunity to merge into a single emotional community. Chapter 3 turns to the Russian avant-garde, whose manifestoes describe a universal language, capable of exerting a compulsive force upon its audience, as a necessary corollary of a planetary communism. From the Babel-like heights of this poetic idiom, according to authors like Velimir Khlebnikov and Aleksei Kruchenykh, the w hole world might be grasped as a single poetic intuition that is at the same time a radical political and economic integration. Valorizing lyric verse rather than narrative prose and a panoramic vision of the globe rather than a networked economic globalism, Futurist experiments with universal language represent a historical corrective to notions of world literature generated within the horizon of global capitalism—an “off-modern” version of world literat ure, to use Svetlana Boym’s phrase for the myriad potential paths suggested by modernist authors but never realized in practice.102 Insofar as the phonetic experiments of the Futurist poets w ere instrumental in the development of the Structuralist linguistics of Roman Jakobson—which served as the “common language” for transatlantic literary scholarship in the

20 I n t r o d u c t i o n

years after World War II—then literary theory itself, much of which developed from or in opposition to Structuralism, can be seen to refract the grandiose ambitions of the Futurists.103 The poet Osip Mandelstam, the subject of chapter 4, professed a “nostalgia for world culture” shortly before he fell victim to the Stalinist purges of the 1930s.104 Mandelstam’s enigmatic late essay Conversation about Dante exploits ambiguous figures of aesthetic inspiration and political tyranny, identifying poetry’s effect on its readership with totalitarian control over the citizenry. A demonstration of and meditation on reading, Mandelstam’s essay addresses perennial problems of our relationship to the authority of writing and the preservation of literary culture through time, largely through a cluster of meta phors around the central image of a conductor’s baton. For Mandelstam, the baton is a central authority that imposes harmony on the orchestra’s cacophony of instruments. The visible instrument of musical measure, the movements of the baton symbolize the undulating line of script traced by the writing pen, which is realized as waves of sound when the poem is read out loud. Mandelstam’s philosophy of notation and performance parallels his effort to reconcile the political and poetical functions of written authority, largely through allusions to scenes in Dante’s Paradiso that compare the power of a dictating muse or a divine creator to the power of kings and tyrants. The metaphorical image of a body caught up in an artistic structure and compelled to act out its commands is realized in Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita through its much-discussed intersection of the aesthetic and the ethical. As I describe in chapter 5, Nabokov translates totalitarianism into the atomized and individualistic sphere of postwar consumerism in the United States. It has gone strangely unremarked that Humbert is not just a madman, the criminal author of a memoir written as a psychiatric patient, but an adman, whose travels with his pubescent captive are bankrolled in part by his sinecure as a writer of advertising copy for perfumes. Advertising, which like art asks its audience to suspend disbelief in a fictional world, is a quasi-aesthetic genre that has to do precisely with the rhetoric of behavior and the ability of words and images to influence action; Lolita’s agonistic mimicry between art and advertising partakes of the techniques of the artist but also the function of the tyrant. In Humbert, who is artist and adman and tyrant rolled up into one, Nabokov accomplishes the transplantation of a Russian problematic of totality into the open markets of the West and the tawdry contingent worlds promised by its consumer goods. Fifty years later, the containment of the world within the single shared horizon of the global market seems at last at hand—even if writers lack as yet the ability to represent that entanglement as anything but conspiracy or to en-

Introduction

21

vision its destiny as anything save catastrophe. At the same time, the irredentist aggression of Putin’s Russia and its recent invasion of Ukraine have reasserted a totalizing imperial vision that, militating against the liberal order, threatens to decimate Russia’s intelligentsia, vitiate its culture, and tarnish the claims to wider relevance of literature in Russian. T hese two versions of totality, both of them timely and pressing, are obviously incompatible with one another; something like a Bakhtinian conflict of irreconcilable ideologies or German Romantic conceptions of dynamic becoming within the infinite chaos of the ungraspable universe might comprehend them in a single theoretical model, but only at the cost of their specificity. A totalizing gesture in a literary text, however, even when it echoes one or another historical ideology, has a purpose beyond adequacy to the world that encompasses the artwork or anything in it. My three-year-old son, who as yet knows nothing of my research but enjoys taking my thickest books off the shelves to judge their bigness, recently volunteered while engaged in this activity, “I have a book, and it is seven hundred four thousand four thousand and sixteen pages long. I actually wrote it. And it is called Everything in the World Is in This Book.” His claim is equivalent to the infinitely capacious volume conjectured by Dante, or by Khlebnikov, or by any number of others. If “genius is nothing but childhood recovered at will,” as Charles Baudelaire remarks, then this child’s fantasy of a universal text speaks to the fundamental impulse to create an all-inclusive artwork that my own book, somewhat more modestly, tracks across two centuries of Russian liter ature.105 The determinate content of t hese literary universes is highly variable and with the flux and churn of history can be made to coincide with one or another political ideology. We can analyze nonetheless a tradition of totality, manifested in the rhetorical techniques of contagion and compulsion, and the related aesthetic of bodily possession, through which artworks imagine themselves as drawing in their audience and encompassing the w hole of space and time.

C h a p te r 1

Versions of Possession Ghost, Demon, Idea, Discourse

Avital Ronell’s book on the afterlife of Goethe in German letters describes a “primary gap between the text and the source,” across which the deceased author, “amplified by myth and biography,” continues uncannily to dictate writings to his inheritors “through more or less conscious channels of transmission and by means of a remote control system.”1 Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky’s 1927 novel The Letter Killers Club (which Ronell could not have known) also begins by evoking Goethe’s omnipresent and determining influence on German literature.2 The discussion of literary influence in the first pages of the book foreshadows a literal technology of bodily control in the science fiction dystopia that makes up its longest and most central chapter. The first experiments with Krzhizhanovsky’s imagined “remote control system” involve writing to dictation; in its final form, the technology makes all the world into a vast text, controlled by a central authority and articulated in h uman flesh. The present chapter treats the Gothic motif of possession in four touchstone moments in Russian literary history: the elegies of Konstantin Batiushkov, written against the backdrop of the Napoleonic wars and Russia’s colonial expansion; the zenith of realism in the novels of Dostoevsky; Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky’s fantastic tales, which refract the tense coexistence of high modernism and communist revolution in the 1920s; and the transgressive metafiction of Vladimir Sorokin, penned in the Soviet Union’s chaotic after22

V e r si o n s o f P oss e ss i o n

23

math. All these authors resort to a metaphoric formulation akin to Ronell’s: a transcendental force of inspiration possesses the artist, dictates the work, and passes through the artistic medium into a public. Because the process constitutes a body politic united by the compulsive force of the artwork, it implies dictatorship as well as dictation. Finally, romantic notions of artistic genius participate in each text in an inexorable and all-encompassing historical logic, eschatological or cyclical, which finds voice in the artwork as its animating force. The same dynamic underpins works treated in detail in f uture chapters, which also turn to supernatural possession as a figure for discourse. Anna Karenina, as she reads on the train, finds herself succumbing to an arcane force that drives her to Vronsky and to her fate as the heroine of a tragic romance; her counterpart, Konstantin Levin, experiences his attraction to Kitty not as love but as “some external power that has seized [him].”3 Ultimately this force can be read as the plot of the book, which conducts the characters to their fated end and frequently finds supernatural expression in something that is not quite ordinary language—for example, in Anna’s ominous foreshadowing dreams of a peasant mumbling French, a dream that Vronsky unaccountably shares, or when the charlatan mystic Landau falls into a trance and ventriloquizes arcane powers that deny Anna her divorce. If Tolstoy’s monument of realism is haunted by Gothic tropes that convey the determining power of discourse, the theme of possession is more evident yet in Aleksei Kruchenykh’s suggestion that zaum is akin to the spiritual visitations of religious ecstasy, in Osip Mandelstam’s theory of dictation across cultural epochs, or in Nabokov’s Lolita, whose narrator utilizes incantatory language to possess his fictional victim as well as the actual reader. In the Russian context, scholarly attention to the Gothic has gravitated to the St. Petersburg myth, to the imperial periphery, and to the unsettled legacy of the Stalinist repressions—concrete situations in which historical traumas have created a world that cannot digest its origin, and have thus doomed the f uture to endless repetition of an uneasy past.4 However, the Gothic can also be expressive of the citational structure that is an ineluctable function of discourse in general, and which this chapter delineates in four loosely linked readings of otherwise divergent texts.

Language and Landscape: Batiushkov’s Ghosts The early Romantic poet Konstantin Batiushkov is best known for his free translations of Western and classical poetry and for his essays in defense of

24 C h ap t e r 1

light verse, but another thread in his c areer leads to ancient Scandinavia. Contemporaries like Vladimir Dal’, Vasily Zhukovsky, Faddei Bulgarin, and Evgeny Baratynsky also wrote Ossianic poems and Scandinavian travelogues, but Batiushkov’s engagement with the theme represents a uniquely intricate and uniquely fraught instance of the so-called Northern Vogue.5 His adaptations of poems by Évariste de Parny or Friedrich von Matthisson, reimagined as the words of a long-dead skald, give voice at once to a studied literary model and to a fantasy of spontaneous northern genius; he reconfigures his Western originals as a possessing force emanating from the ancient North. Batiushkov’s elegies are further complicated by the fact that the author served with the Rus sian troops occupying Finland in the 1809 war. The Viking ghosts possess and inspire the Russian soldier-poet in the instant that the Russian occupies the land where the skald is buried; like the pagan predecessor he ventriloquizes, the lyric speaker is an agent of both poetic prowess and military might. A rich ideology of empire emanates from this marriage of literary succession and military conquest. Batiushkov draws on Romantic notions that the peoples of northern Europe could achieve the cultural heights of the ancients only by tapping into their youthful vitality and developing their own cultural forms. He constructs for Russia—a peripheral country whose claim to Euro pean modernity rested in part on its digestion of the Swedish Empire—a source of inspiration in a primeval northern poetry, something like the “barbarian lyre” that Alexander Blok evokes in his poem The Scythians.6 This myth of shared origin sharply distinguishes Russian poetry on Scandinavian themes from verses dealing with the eastern and southern colonies and gestures toward a synthesis of two of the most fruitful directions in scholarship on the period. The first of t hese, outlined by authors like Dmitri Sharypkin, Iury Levin, and Otto Boele, demonstrates the necessity of considering an opposition between North and South, “inherent in Preromantic literature in general and Gothic literature in particular,” alongside the more conventional dichotomy of East and West.7 The second direction, pioneered by Monika Greenleaf ’s Pushkin and Romantic Fashion and Harsha Ram’s The Imperial Sublime, demonstrates the dialectic between the elegy as a genre and the expansion of the Russian imperial state, through which, as Ram puts it, “the romantic artist becomes an ambiguous third element in the otherwise binary conflict between the colonizer and the colonized.”8 Greenleaf claims that “the poet’s mourning implicitly lays claim to his poetic inheritance: he establishes himself as the next living link in the elegiac tradition.”9 Batiushkov’s self-identification with skaldic poetry additionally suggests a mythology of political legitimacy. Valeria Sobol’s recent book Haunted Empire, which stresses the “blurring of boundaries between the colonizer and the col-

V e r si o n s o f P oss e ss i o n

25

onized” in the Baltic territories, describes the historical mythologies that trace the foundation of the Russian state back to the Rurikid dynasty of Finland, thanks to which the conquest of Russia’s northwestern frontier could be made to seem “a legitimate return of Riurik’s homeland to the Russian Tsar.”10 Discussing M. N. Murav’ev’s historical romance Oskol’d in an 1814 essay, Batiushkov admires its “inspired skalds with golden harps,” whose “songs of battle and heroism” compel a troop of Varangian warriors to abandon their fishing nets and undertake the expedition to Constantinople that will culminate in the foundation of Kievan Rus.11 Associated simultaneously with poetry and military conquest, the skald “reminds us of Lomonosov,” Batiushkov asserts, “the f ather of Russian verse . . . who has earned the attention of later generations not only through his poetic talents, his incredible labors and successes in the arts and sciences, but through his very life, filled, if I may use this expression, with poetry.”12 The Viking is transformed from an emblem of Rus sia’s distant past into the very personification of Russia’s entrance into cultural modernity: the polymath genius Mikhail Lomonosov, who discovered the chemical law of mass conservation, founded a glass factory, systematized Rus sian versification, and himself wrote heroic poems on Russia’s military campaigns in the Baltic. By linking Lomonosov to the Rurikid Vikings, Batiushkov imagines for modern Russian verse deep historical roots in an invented skaldic tradition. The Viking bard’s role as a rhetorical figure for the contemporary issues of Russian poetry motivates Batiushkov’s programmatic poem Dream, originally composed between 1802 and 1805 and published in its final form in 1817. In this paean to the lyric imagination, the skald appears as a figure for the Romantic poet himself, the dreamer of the poem’s title: В полночный час Он слышит Скальдов глас In the midnight hour He hears the voice of the skalds and is transported into a fabric of images drawn from Nordic mythology.13 The same verses are inserted into Batiushkov’s 1809 Excerpt from the Letters of a Rus sian Officer about Finland, which frames them as the runic inscription on a Viking burial marker, brought to life through the creative fantasy of the Russian warrior-poet who is the Scandinavian bard’s successor.14 Among Batiushkov’s many Scandinavian texts, which pepper the decade of his greatest productivity, the Excerpt, composed while Batiushkov was stationed on the Gulf of Bothnia, is uniquely illuminating.15 Certainly it was the most influential, as it remained

26 C h ap t e r 1