The Letters of Thomas Carlyle to His Brother Alexander, with Related Family Letters [Reprint 2013 ed.] 9780674333291, 9780674331709

208 85 19MB

English Pages 843 [848] Year 1968

Preface

Contents

Introduction

Letters

I. Apprenticeships, 1819-1825

II. Unions and Reunions, 1825-1834

III. Letters Across the Solway, 1834-1843

IV. Letters Across the Atlantic, 1843-1881

Short Titles and Abbreviations

Glossary of Selected Scotticisms and English Dialectals

Index

Recommend Papers

![The Letters of Thomas Carlyle to His Brother Alexander, with Related Family Letters [Reprint 2013 ed.]

9780674333291, 9780674331709](https://ebin.pub/img/200x200/the-letters-of-thomas-carlyle-to-his-brother-alexander-with-related-family-letters-reprint-2013nbsped-9780674333291-9780674331709.jpg)

- Author / Uploaded

- Thomas Carlyle (editor); Edwin W. Marrs

- Jr. (editor)

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

THE LETTERS OF THOMAS CARLYLE TO HIS BROTHER ALEXANDER

THOMAS

CABLYLE

ALEXANDER CABLYLE

The Letters of Thomas Carlyle to His Brother Alexander WITH RELATED FAMILY LETTERS

Edited by Edwin W. Marrs, Jr. THE BELKNAP PRESS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1968

© Copyright 1968 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Distributed in Great Britain by Oxford University Press, London Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 68-21978 Printed in the United States of America

To Mrs. Ernest D. Clump, Mrs. John A. Carlyle and the Memory of My Father

PREFACE

of the letters in this collection in February 1819, when he was twenty-three and groping about in Edinburgh for the work suitable to his talent and temperament. Alexander was then twenty-one and still farming at Mainhill, their father's rented farm sixty miles south of Edinburgh in the border country of Scotland. Carlyle wrote his last letter to his brother in February 1876, two weeks before Alexander died at Bield, his own farm on the Niagara Peninsula in Canada. The merits of the letters individually and as a collection are clear. Almost every one of Carlyle's letters to Alexander is an example of what a fine letter should be — spontaneous, candid, full, and containing such vivid descriptions of person and place as to make the reader see with the writer. Carlyle's London carman, for example, who "with his huge slouch hat hanging halfway down his back, consumes his breakfast of bread and tallow or hog's lard, sometimes as he swags along the streets, always in a hurried and precarious fashion, and supplies the deficit by continual pipes and pots of beer," appears to swag by us. Our visions of the "miserable goggle-eyed scarecrow" figure of Bulwer-Lytton or of "Holborn in a fog! with the black vapour brooding over it, absolutely like fluid ink," approximate Carlyle's by the power of that vision and his word. Carlyle's ability to capture the whirl of the passing scene for Alexander with the force that he used to revivify the past for all men makes this collection of letters as remarkable as a chronicle in little of its epoch as The French Revolution or Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches are in large of theirs. As such it contributes to our understanding of the period in which Carlyle lived. The collection is also remarkable for its frank disclosure of Carlyle's feelings and contributes to our understanding of Carlyle himself. In his preface to the New Letters of Thomas Carlyle, Carlyle's nephew C A R L Y L E WROTE THE FIRST

vili

PREFACE

Alexander explained that he had included a large number of the letters Carlyle wrote after his wife's death as evidence that Carlyle bore even his greatest loss with a reasonable share of equanimity. Considering that Carlyle's letters and not his gloomy Journal entries reflect his prevailing state of mind, we should, he concluded, judge that state of mind mainly by his letters and recognize it as at least more sanguine in its outlook than we customarily believe it was. The letters in this collection support the younger Alexander Carlyle's conclusions in spite of their abundant concern with the real and imaginary illnesses of their writer. They have additional value in their open and copious expression of feeling, and in this regard are distinguished from the letters Carlyle wrote to Goethe, Emerson, Mill, Sterling, and Browning. Only to his wife and to his brother John did Carlyle express himself in his letters as freely as he did to Alexander. The collection is uniquely remarkable for its conclusive statement of Carlyle's capacity for fraternal love. He showed his love for Alexander in many of the letters he wrote either to or about him, by the frequency with which he wrote and the moral and financial support he gave to him, by accepting support from him in return, and by graphically bringing to him the sophisticated worlds from which Alexander was isolated and their own rustic world of Annandale after hard necessity had forced Alexander to leave it. Carlyle declared what Alexander meant to him in a number of places in and out of these letters, but never more eloquently than in his last letter in this collection, written to Alexander's son Thomas shortly after Alexander's death: "There never was a kinder Brother than he from his earliest years, and without break through life was to me. True as steel he ever was, and with a fund of tenderness, strange in one of so fiery a temper; a man of infinite talent, too, had it been developed by friendly fortune; I never knew a more faithful, ingenious and valiant man. He was, withal, the first human being I ever came to friendship and familiarity with in this world; and our hearts were knit together by a thousand ties. Very beautiful, very sad and tender are the endless recollections I have of him, which must continue with me as companions while I live. No doubts similar thoughts dwelt in his mind about me, and it seems were even present with him." The collection is finally remarkable for its delineation of the faith-

Preface

ix

ful, ingenious, valiant Alexander, his character and his struggles, and many of the thousand ties that bound brother to brother all their lives. The history of the letters that Alexander received and saved, some for fifty-seven years, is reasonably clear. After his death they passed to his eldest son, Thomas. Probably soon after Carlyle's death Thomas sent them to London to his cousin Mary Aitken Carlyle, editor of Scottish Song: A Selection of the Choicest Lyrics of Scotland ( London and Glasgow, 1874), wife of Thomas' brother Alexander, and Carlyle's companion and amanuensis during his last years. At her request Charles Eliot Norton edited a selection of them and the other letters she had collected, and in 1886 he published part of her collection as the Early Letters of Thomas Carlyle, 1814-1826. He followed it in 1888 with the Letters of Thomas Carlyle, 1826-1836. Mary's husband, Alexander, carried on after Norton and in 1904 published the New Letters of Thomas Carlyle. Alexander then returned Thomas' letters to him in Canada, where with rare exception they have remained ever since, first in the care of Thomas, then his children, and most recently his grandchildren. Seven years ago Mrs. Ernest D. Clump, of Paris, Ontario, Thomas' only surviving daughter and the sole survivor of her generation of Carlyles, showed me the two hundred Carlyle and Carlyle family letters in her trust and gave me, with the kind approval of her relatives in Canada, permission to publish them. At the same time Mrs. John A. Carlyle, also of Paris, widow of Mrs. Clump's brother, arranged permission for me to publish the forty-five letters the younger Alexander had given to her husband, who had left them to his son, Hugh M. Carlyle. From the collections of Mrs. Clump and Mrs. Carlyle, I have taken all of Carlyle's letters and all except three of the letters written by other members of his family. Through the generosity of the trustees of the National Library of Scotland and the John Rylands Library I have been able to include five more letters from Carlyle to Alexander and a fragment of a sixth, to which I did not assign a number and which is not counted in my computations below; a postscript from Carlyle to his sister Jean that completes a letter from Alexander to Carlyle, which because of their dates and an intervening letter I had to count as two separate letters; and a selection of the letters from

X

PREFACE

Alexander to Carlyle. Those, plus the fourteen published Carlyle letters to Alexander whose holographs I have not been able to recover, brought the total collection to 271 letters. It includes 243 from Carlyle, 9 from Alexander, 18 from other members of the family, and one from William Hone. Of the 243 from Carlyle, 222 are to Alexander and 21 to other members of the family. Of the 243 from Carlyle, 126 are published here for the first time and 97 of the remainder appear for the first time in their entirety. The 222 from Carlyle to Alexander are, so far as I am aware, every extant letter from the one brother to the other. In editing the letters, I have observed several principles: 1. I- have identified the writer of a letter only when he was not Carlyle and the addressee only when he was not Alexander. 2. I have given the location of a holograph letter only when the letter is not held by Mrs. Clump or her nephews and nieces in Canada or by Mrs. Carlyle or her two children. 3. In the cases where I have been unable to recover the holograph letter to a published text, I have noted that fact, the source of my text, and any instance where my treatment of the body of the letter departed from the previous editors. Any ellipses in such a letter are the former editor's. 4. In cases where an extant holograph letter has been published in the Early Letters, the Letters, or the New Letters, I have noted the fact, but not that it may appear elsewhere as well. If no publication information is given, it indicates that the letter is previously unpublished. 5. I have tried to provide a text that is faithful to the holograph letters. Thus, I have retained the misspellings and, within angled brackets, the cancellations that convey an original meaning that was altered. I have deleted canceled misspellings, words out of order, and portions of words. I have used ellipses to indicate where a word or passage is illegible or has been torn away, and placed square brackets around my insertions. 6. At the same time I have tried to provide a text that is readable. Thus, I have silently omitted the occasional word or two at the bottom of a sheet that the writer repeated at the top of his next one, lowered all superior characters and interlinear readings, expanded such

Preface

xi

awkward abbreviations as cd, wh, d°, &, EdinT, bror, tho*, added a few marks of punctuation to clarify confusing passages, and followed the American rules governing pointing about close-quotation marks. 7. For the sake of uniformity and a pleasing appearance, all letters have been standardized in the placement of heading, salutation, body, complimentary close, signature, and postscripts. The complimentary close has been run into the body of the letter after its final sentence to avoid diverting the reader's eye from the letter proper and because it was a practice Carlyle himself observed in over half of his letters. The postscripts have been placed at the ends of the letters, and in some instances of necessity in an arbitrary order, regardless of where they appear on the original. 8. To keep both the number and bulk of the notes to a minimum, I have identified only at their first instance unfamiliar persons, places, publications, events, and quotations, and with the exception of the quotations have noted what I could not identify. For the same reasons I have cited only H. D. Traill's edition of the Critical and Miscellaneous Essays and Collectanea Thomm Carlyle, 1821-1855, ed. Samuel Arthur Jones (Canton, Pa., 1903), as secondary sources for Carlyle's critical essays and established a glossary of selected Scotticisms and English dialectals. The short titles and abbreviations I have used in the notes are listed at the end of the book. It is my pleasure to acknowledge those who helped me. Clearly I owe an exceptional debt to Mrs. Clump and Mrs. Carlyle. Although they have my personal thanks, I hope that this book, on which they too worked to display accurately their magnificent family letters, more adequately expresses my gratitude. Cecil Y. Lang's presence and counsel have been vital. His enthusiasm and encouragement inspired me to begin, and his exemplary scholarship and patient instruction guided me to the end. Charles Richard Sanders opened to me his fund of knowledge of Carlyle and, to the extent that he could without violating in any way his many trusts, his monumental collection of the Carlyles' correspondence. I owe Professor Lang and Professor Sanders much more than thanks, but it is all I can give them here. I also thank Florence Blakely, Mary Canada, Mary Frances Morris,

xii

PREFACE

and Emerson Ford of the Duke University Library; Louise McG. Hall, Dorothy Daetsch, Eileen Mcllvaine, Pattie B. Mclntyre, and Joan Beaird of the University of North Carolina Library; Pauline L. Ralston and Marion L. Mullen of the Syracuse University Library; Eric von Brockdorff and Georgia O'Brien of the Colgate University Library; Jonathan Addelson of the Boston Athenaeum; the staffs of the Library of Congress, the Yale University Library, the Dartmouth College Library, and the Harvard College Library; and, for their expert clerical and editorial assistance, Janet Edwards and Linda Greene. In England I am indebted to F. N. L. Poynter and Sue Goldie of the Wellcome Historical Medical Library and Honorary Editor and Editor of Medical History; Thomas Ashworth, Chief Librarian, the Central Library, Bolton; the staffs of the British Museum, the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, and the Cambridge University Library; D. W. Kennedy of the British Linen Bank, London; M. Godfrey of the Public Records Office, London; the office of the Ministry of Defense, Whitehall; the Town Clerks' offices of Manchester and Workington; and Janetta Taylor of the University of Hull and assistant to Professor Sanders. To Carlyle's own countrymen I am under special obligation. There were no lengths to which they did not go to answer my many questions. Among those most helpful were Allan Cunningham, formerly Lord Provost, Ecclefechan, and kinsman of the Nithsdale poet whose name he bears; Mrs. S. M. McLean, Honorary Secretary of the Carlyle Society and County Librarian, the Ewart Public Library, Dumfries; George D. Grant, Town Clerk, and James A. Stewart, Town Clerk Deputy, Dumfries; A. E. Truckell, Curator, the Burgh Museum, Dumfries; and George Gilchrist, Registrar, Annan. I am heavily and pleasantly obliged to David D. Murison, Editor, the Scottish National Dictionary; James S. Ritchie, Assistant Keeper of Manuscripts, the National Library of Scotland; Charles W. Black, City Librarian, the Mitchell Library, Glasgow; Charles P. Finlayson, Keeper of Manuscripts, and S. M. Simpson, the Edinburgh University Library; W. S. Taylor, City Librarian, Dundee; the staffs of the Kirkcaldy Public Libraries; Walter J. Chinn of the Clydesdale Bank, Limited, Glasgow; C. M. Kerr of the British Linen Bank, Dumfries; Oliver and Boyd, Limited; Hugh D. L. Simpson, Town Clerk, Moffat; and H. Reynold

Preface

xiii

Galbraith, Town Clerk, and the Reverend Mr. John Johnston of St. Peters Manse, Inverkeithing. I am grateful to Syracuse University, the Colgate University Research Council, and the University of Pittsburgh for their financial aid; Duke University for a fellowship and teaching appointment in 19631964, which afforded me the opportunity to work with Professor Sanders; and Gordon N. Ray, who helped to make that opportunity possible. For her years of assistance I am most grateful to my wife, Perthenia. E. W. M., Pittsburgh, Pa. November ig6y

JR.

CONTENTS

Introduction

ι

Letters I II

APPRENTICESHIPS, 1 8 1 9 - 1 8 2 5

21

UNIONS AND REUNIONS, 1 8 2 5 - 1 8 3 4

III

LETTERS ACROSS THE SOLWAY,

1834-1843

IV

LETTERS ACROSS THE ATLANTIC,

1843-1881

I97

337 549

Short Titles and Abbreviations

797

Glossary of Selected Scotticisms and English Dialectals

800

Index

806

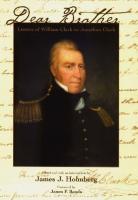

ILLUSTRATIONS

Thomas Carlyle From a photograph by Elliott and Fry Studio, London, in the possession of Mrs. Ernest D. Clump

ii

Alexander Carlyle From a photograph by J. N. Edy & Co., in the possession of Miss Ethelwyn Carlyle

ii

Map of Dumfriesshire

17

Carlyle Genealogy

18

Welsh Genealogy

19

Facsimile of Letter No. 201

617

THE LETTERS OF THOMAS CARLYLE TO HIS BROTHER ALEXANDER

INTRODUCTION

the Carlyles were originally English, took their name from the Cumberland town of Carlisle, and crossed over into Annandale in the fourteenth century with David Bruce, David II, king of Scotland. Nicholas Carlisle, an antiquary and assistant librarian to King George III, traced Carlyle's descent back through Sir John Carlyle, first Baron Torthorwald, to William of Cairlyle, who married Margaret Bruce, sister of Robert de Bruce VIII, king and liberator of Scotland. The Torthorwald title lapsed, the estates were lost in lawsuits, and Sir John's descendants eventually settled and for three generations farmed a poor plot at Burrens (or Birrens), the site of the old Roman station in Middlebie parish, Dumfriesshire. Carlyle himself tells us tradition also has it that once "in times of Border robbery, some Cumberland cattle had been stolen and were chased; the trace of them disappeared at Burrens, and the angry Cumbrians demanded of the poor farmer what had become of them? It was vain for him to answer and aver (truly) that he knew nothing of them, had no concern with them: he was seized by the people, and despite his own desperate protestations, despite his wife's shriekings and his children's cries, was hanged on the spot! The case even in those days was thought piteous; and a perpetual gift of the little farm was made to the poor widow as some compensation. Her children and children's children continued to possess it; till their title was questioned by 'the Duke' (of Queensberry) and they (perhaps in my great-grandfather's time, about 1727) were ousted" (Reminiscences, 1,27). TRADITION HAS IT THAT

Thus, it was about the time of the death of Carlyle's great-grandfather John Carlyle (1687-1727), the remotest ancestor Carlyle would lay positive claim to, that his family moved into Middlebie village, where John Carlyle's widow, the former Isabella Bell (1687-1759), struggled tò raise their two sons. Francis (1726-1803), the younger, became a shoemaker and traveled for work deep into England. One

2

INTRODUCTION

black morning, a story goes, he awoke perhaps in Bristol with his money gone and the taste of his indulgences of the night before on his tongue. He threw himself out of bed, broke his leg in the process, and then and there resolved to make a better life for himself. He enlisted on a man-of-war, helped to put down a mutiny, was rewarded with the command of a revenue cutter that worked the Solway, and in time married Sarah Bell ( 1 7 1 5 - 1 7 7 6 ) and retired a respected man in Middlebie. Thomas (1722-1806), the older brother, a tough, fiery, irascible man, became a carpenter and at first went down into Lancashire. But he was in Ecclefechan in 1745 when the Highlanders came through to fight the Pretender's forces along the border, and he was among them in Dumfries on their return. After that he worked at his trade in Middlebie, but eventually gave it up to farm Brownknowe, near Burnswark Hill. He married Mary Gillespie (1727-1797), who was from or near Dryfesdale, and by her had three daughters and four sons. James, Thomas' second son, was Carlyle's father. He was born at Brownknowe in August 1758 into the poverty his father had known as a boy and improvidently chosen not to correct as a man. So James and his brothers had to learn as their father before them how to knit and thatch and hunt to keep body and soul together. His education was the slightest. He may have spent three months in a school, perhaps not that. John Orr, at once a religious man and a drinker, a shoemaker and a schoolmaster at Hoddam (or Hoddom), used to visit Brownknowe and while there tutor James in arithmetic, writing, and other practical disciplines. Robert Brand, James's maternal uncle, filled him as he himself was filled with religion. But it was James's own natural intelligence and possibly the examples both good and bad his father set for him that instructed him finally in his conduct in this world. It was his nature to accept without question his religious teachings and be able to operate successfully under them throughout his life. It was his nature to be curious about life's significant elements and to pass by unheeded all its hateful trifles and the clamor of public opinion. And it was his nature to know his duty and do it. He believed passionately in the Calvinist doctrine of the divine propriety of work and passed his belief on to his sons. He also passed on to them his respect for intellectual force and, to one in particular, his natural eloquence.

Introduction 3 Carlyle's description of his father's style might well be a description of his own. It was, Carlyle wrote, a "bold glowing style . . . flowing free from the untutored Soul; full of metaphors (though he knew not what a metaphor was), with all manner of potent words (which he appropriated and applied with a surprising accuracy, you often could not guess whence); brief, energetic; and which I should say conveyed the most perfect picture, definite, clear not in ambitious colours but in full white sunlight, of all the dialects I have listened to. Nothing did I ever hear him undertake to render visible, which did not become almost ocularly so" ( Reminiscences, I, 5 ). It is strange that a man who cared as James did for the poetry of truth and could find it in all the disparities of life and articulate it with clarity could find no truth in poetry. But he found it idle and accordingly judged it criminal, even the poetry of Burns, his coeval. About 1773, after the family had left Brownknowe for Sibbaldbyside, a farm in the Dryfe valley near Lockerbie, William Brown came down into Annandale and met and married James's eldest sister, Fanny (1752-1834). Brown gathered his four brothers-in-law about him and taught them his masonry trade. They banded together, appointed James as their head, and as a kindred respected by both those who liked them and those who feared them became the most skillful, most trustworthy, best-rewarded masons in the district. The brothers plied their trade up and down the Annan valley, James and Brown once in Nithsdale, and in 1791 settled in the eastern Annandale village of Ecclefechan. Here James built his arched house and in the year of his settlement married his distant kinswoman Janet Carlyle. She bore him one son, John (1792-1872), before she died on September 11, 1792. James entrusted the raising of the boy to his father-in-law, called Old Sandbed after his farm above Dumfries and Kirkmahoe, and continued on alone in the two-room apartment on the second floor of the arched house. It was probably in the winter of 1794-1795 that he met Margaret Aitken, who was, in her son's words, "a woman of to me the fairest descent, that of the pious, the just and wise: . . . to us the best of all Mothers, to whom for body and soul I owe endless gratitude" ( Reminiscences, I, 42). She was born September 30, 1771, at Whitestanes, Kirkmahoe, Dumfriesshire. At the time James and Margaret met, John,

4

INTRODUCTION

her father, was a widower, probably, and a bankrupt farmer out of Nithsdale, and Margaret was serving in the house of her aunt Mrs. John Bell (d. 1800) of Townfoot, Ecclefechan, to help out. James and Margaret were married March 5, 1795, and moved into the arched house. On December 4 of the same year she gave birth to Thomas. On August 4, 1797, the couple had their second child, Alexander. Within this or early in the next year the family moved across Pepper Field to the original of the "roomy painted Cottage" of Sartor Resartus, where they lived for the next seventeen years and where James and Margaret had seven more children: Janet, born September 2,1799; died February 8,1801. John Aitken, born July 7, 1801; died at his sister Jean s home in Durafries September 15, 1879. Margaret, born September 20, 1803; died of consumption at her father's farm, Scotsbrig, June 22, 1830. James, born November 12, 1805; died at Pingle Farm, Canonbie, May 5, 1890. Mary (Mrs. James Austin), born February 2, 1808; died at The Gill, Cummertrees, April 6, 1888. Jean (Mrs. James Aitken), born September 2, 1810; died at The Hill, Dumfries, July 27, 1888. Janet, called Jenny (Mrs. Robert Hanning), born July 18, 1813; died in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, December 1897. James had his savings and work enough in those early years to provide comfortably for his growing family. In consequence, Carlyle's boyhood in Ecclefechan was distinctly unlike what his father's and forefathers' had been. He could run about the village at will, observe the artisans at work through their open doors, watch the passing wagons and the changing of horses on the coaches from London and Glasgow, attend the weekly markets and annual fairs. There were woods and streams and fields he could explore, and he could visit his grandfather Thomas. On occasion Old Sandbed would bring John to visit him. He could recall throwing his little brown stool at his half brother in a moment of rage one of those times, breaking it, and suffering for perhaps the first time "the united pangs of Loss and Re-

Introduction 5 morse" ( Reminiscences, I, 45 ). He could recall his father and mother returning from Dumfries and bringing for him and Alexander their first new halfpence. He could recall the death of his infant sister Janet and his mother's attendant grief, and his uncle John's funeral "and perhaps a day before it, how an ill-behaving servant-wench to some crony of hers, lifted up the coverlid from off his pale, ghastly-befilleted head to show it her: unheeding of me, who was alone with them there, and to whom the sight gave a new pang of horror" ( Rem-

iniscences, I, 33 ). Most vividly he could recall attending sermon at the Ecclefechan Meeting House. The seceders from the Established Kirk are essentially advocates of a stricter adherence to the original government of that Kirk, the Church of the Reformation. Carlyle explained that "A man who awoke to the belief that he actually had a soul to be saved or lost was apt to be found among the Dissenting people, and to have given up attendance on the Kirk" ( Reminiscences, II, 1 1 ) . One who bolted from the Establishment, from its officialities, stipends, and practice of forcing settlement of ministers on the people, was Adam Hope, English master at the Annan Academy and a Calvinist through and through. Before Carlyle's time he had collected others of a like mind about him and organized them into the Annan Burgher Congregation. They built a meeting house in Ecclefechan and chose for their minister John Johnstone (1761-1812), the most nearly perfect priest Carlyle ever knew. From a distance of sixty years or more Carlyle could remember seeing Adam and his followers, who had walked their six miles from Annan, and some pious Scots weavers, who had walked their sixteen from Carlisle, listening to the Reverend Mr. Johnstone while their coarse plaids dripped from the hooks in the rear of the little building. "Rude, rustic, bare," Carlyle called it, "no Temple in the world was more so; — but there were sacred lambencies, tongues of authentic flame from Heaven, which kindled what was best in one, what has not yet gone out" ( Reminiscences, II, 15 ). James Carlyle desired to raise a son worthy of a university education, and Thomas showed early promise of fulfilling that desire. By the time he was five his father had taught him how to figure and his mother had taught him how to read. Shortly after the turn of the century. they enrolled him in the Brickhouse School in Ecclefechan,

6

INTRODUCTION

where Tom Donaldson, a young Edinburgh man, instructed him. In 1802, when Donaldson transferred to a school in Manchester, James transferred his son to the Hoddam School about a mile away. By the summer of 1803 the boy had mastered the rudiments of English composition and, with the help of the Reverend Mr. Johnstone and his son, Latin as well. He learned to read Horace and Virgil with a facility exceptional for one his age and took delight in translating the inscriptions on the Roman remains at Burrens and Burnswark. Within two more years he had become aware of the song of poetry and was soon reciting from Campbell, Cowper, and Burns. When his instructors at the Hoddam School reported him prepared in arithmetic, English composition, and Latin, his parents decided he should go on to the Annan Academy for a course of study that would prepare him for Edinburgh University and the ministry. They made arrangements for his weekday board and room with his mother's aunt Barbara, the wife of Marion Waugh, bailie and cobbler of Annan. On May 26, 1806, his spirits at once cast down at parting with his mother and home and raised aloft at the prospect of the venture, he and his father set out. What they found upon their arrival, an event that in retrospect proved premonitory of the unrest Carlyle encountered in Annan, he later wove faithfully into the fabric of Sartor Resartus: "Well do I still remember the red sunny Whitsuntide morning, when, trotting full of hope by the side of Father Andreas, I entered the main street of the place, and saw its steeple-clock (then striking Eight) and Schuldthurm (Jail), and the aproned or disaproned Burghers moving-in to breakfast: a little dog, in mad terror, was rushing past; for some human imps had tied a tin-kettle to its tail; thus did the agonised creature, loud-jingling, career through the whole length of the Borough, and become notable enough. Fit emblem of many a Conquering Hero, to whom Fate (wedding Fantasy to Sense, as it often elsewhere does) has milignantly appended a tinkettle of Ambition, to chase him on; which the faster he runs, urges him the faster, the more loudly and more foolishly! Fit emblem also of much that awaited myself, in that mischievous Den; as in the World, whereof it was a portion and epitome!" (pp. 82-83). The mischievousness resided in the persecution the precocious boy suffered from his more common schoolfellows. It lasted until his second year, when

Introduction

η

one day, violating a promise he had made to his mother not to fight, he slipped off his clog and gave the biggest and most annoying of his tormentors a blow that sent the bully sprawling in a mudpuddle. From then on he was left alone. Of his teachers he wrote only of Adam Hope, whom he admired to the extent that he made him, in the Reminiscences, II, 6-7, the subject of one of his most memorable and sympathetic protraits, and one Morley from Cumberland, who taught him arithmetic, algebra, and geometry. He received from others some small instruction in geography and Greek and some considerable instruction in Latin and French. He taught himself a smattering of Hebrew. He read every book he could get his hands on, and he got them mainly from a circulating library operated by John Maconachie, an Annan cooper, whom Carlyle immortalized in Sartor Resartus (p. 84) as Hans Wachtel. Maconachie also boarded many of Adam's pupils in his home, and Carlyle used to attend the periodic discussions Maconachie conducted on all the important biographies, geographies, histories, and novels published by then. It was perhaps at this time that Carlyle became aware of the world of history through William Robertson's ( 1721-1793) The History of the Reign of the Emperor Charles V, 3 vols. ( 1769). It was at this time that he discovered the art of Smollett through Roderick Random and Humphry Clinker. Carlyle's gloomy academy life came to a close in 1809. For his father, who never earned more than £, 100 a year in his lifetime, the decision to send him on to Edinburgh was a serious one. There were no scholarships, fellowships, grants, or interest-free loans then that a boy could try for; no dormitories, fraternities, or clubs of any sort he could live at; no college dining hall where he could purchase a reasonably good meal for a reasonable price. Edinburgh University had been established only as a place where boys might come to learn. How they managed past that was not its concern. Each November the majority of its eleven hundred students, for the most part the most promising sons of Scots tradesmen and farmers, walked from their homes to the city, sought their cheap rooms, made their arrangements at the university, and girded themselves to subsist for the next six months largely on the oatmeal, eggs, butter, and potatoes the carriers would bring them from their parents. During the term they stud-

8

INTRODUCTION

ied, found amusement primarily among themselves, and, if they could, tutored to ease the burdens they had placed on their fathers. When the term ended in April they walked their various distances home to help out there for the next six months. But the reports from Annan were all favorable and James and Margaret had not for a moment failed to see their son's superior qualities. So on the dark, frosty morning of November 7, 1809, they walked him through Ecclefechan and set him on his way with Thomas Smail, who had attended the university the year before and was to become a Burgher minister in Galloway. The two trekked through Moffat and Ericstane, the wearisome Smail usually leaving the younger boy alone with his reflections in the silent countryside. They made twenty miles a day, arriving in Edinburgh on the afternoon of November 9. Carlyle found lodging in Simon Square, had a bite of dinner, and at Smail's insistence sallied out in the shortening day to see the city and observe the proceedings in Parliament's Outer House. The sights and sounds that met him then from within that immense candlelit hall thronged with spectators and lords of the law, with court criers screeching like birds from their nest-like stalls high up on the walls, with black-gowned advocates pleading their cases before red-robed judges, must have come back to him when he was briefly tempted to study the law nine years later. Within a day or two Carlyle entered his name in the university's matriculation album. In his first year we know he attended Professor Alexander Christison's Latin class and Professor George Dunbar's class in Greek. We also know he became disappointed with Christison and in time with most of his professors. But what he felt he was missing in the classroom he tried to acquire in the books he borrowed from the university and private suscription libraries and from discussions with the friends he made—students like himself who came from simple, rustic backgrounds. One was George Johnstone, who was graduated in medicine in 1822, was living in Marsden in 1825, and had established a medical practice in Liverpool by 1831. A second was Robert Mitchell (1795?-1836) from Hutton and Corrie parish, Dumfriesshire. He was graduated M.A., taught at Kirkmichael for a year, tutored the children of Mr. Napier of Linlithgow for another, and then for seven years those of the Reverend Dr. Henry Duncan ( 1774-1846), minister at Ruth-

Introduction

9

well, founder of the first savings bank, publisher of the Dumfriesshire Journal, and founder and publisher of the Dumfries and Galloway Courier. Mitchell was made rector of the Kirkcudbright Grammar School in 1821 and classics master of the New Edinburgh Academy in 1824, where he taught until his death. He is said to have written Outlines of Ancient and Modern Geography, which is listed in the catalogues, but anonymously and without a date. A third was James Johnstone (d. 1837) from Bogside, a small farm establishment near Ecclefechan. He was perhaps Carlyle's second cousin. By 1814 he was tutor to the children of the Churches of The Hitchill, a farm near Cummertrees, whose dwelling house Carlyle's father had built. Mr. Church was steward of the Queensberry estates; his wife was Ruskin's greataunt. In 1819 Johnstone sailed to Nova Scotia and returned in 1821. By 1823 he was tutor to the children of General M'Kenzie of Broughty Ferry, Dundee, and by October 1825 was a schoolmaster at the Haddington Parish School. Thomas Murray ( 1792-1872) from the parish of Girthon, Kirkcudbrightshire, whom Carlyle met on the road to Edinburgh in 1810, was a fourth friend. By his own early example he was one of the first to foster in Carlyle the possibility of living by literature. He contributed to David, later Sir David, Brewster's ( 1781-1868) Edinburgh Encyclopaedia, the Scots Magazine, the Dumfries and Galloway Courier, and in 1822 published The Literary History of Galloway: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time. In 1818 the presbytery of Wigtown licensed him to preach, but after a short period he gave it up, moved back to Edinburgh, for a while took in students, and in 1841 established the printing firm of Murray and Gibb. Carlyle made other friends, but these four have particular significance in these letters. In the session of 1810-1811 Carlyle enrolled for logic, Greek, and mathematics, the last under John Leslie ( 1766-1832), who was the one teacher able to inspire Carlyle and in whom Carlyle recognized and admitted as having an element of genius. Leslie for his part had noticed Carlyle's ability and secured for him an elderly gentleman to tutor this year and perhaps the next. By the end of this school year his earnings allowed him the luxury of coach fare as far as Moffat, where he found and henceforth would find Alexander waiting to escort him home. In 1811-1812 he enrolled for the third year in Greek, substituted

10

INTRODUCTION

Professor Thomas Brown's (1778-1820) course in moral philosophy for logic, and returned to mathematics under Leslie. Influenced by Leslie and at an age when the tangibility of fact and law would be more appealing than the elusiveness of the less demonstrable disciplines, geometry understandably rose before him "as the noblest of all sciences" (Froude, I, 26). He studied it fervently and in 1812 took the dux prize for his achievements. He continued with Leslie in 1812-1813. That year he also took chemistry, which he called the "most brilliant and fascinating of the physical sciences" (Espinasse, p. 207), and John Playfair's (1748-1819) course in natural philosophy. He completed his arts curriculum in April 1813, and over the summer must have considered his future. Although his parents from the beginning had set their hearts on his becoming a minister, Carlyle was never in the least enthusiastic about it. He was now seriously doubting he could ever find a fit place for himself in a church that as he saw it did not believe its own formalism. He had three choices open to him: he could try to put aside his doubts and return to Edinburgh as a divinity student for the four more years of study that would lead to orders and a church appointment; he could become a rural divinity student and as such have only to read an independently prepared discourse once a year for six years in Divinity Hall to achieve the same ends; or he could give up the idea of taking orders altogether. Wishing neither to disappoint his father and mother nor to rush toward a final resolution, he chose the middle course. He nevertheless returned to Edinburgh in the fall, hoping to pay his expenses by tutoring, and attended Professor Robert Jameson's (1774-1854) natural history course. Murray wrote in his Autobiographical Notes . . . , ed. John A. Fairley (Dumfries, 1 9 1 1 ) , that he was successful in finding employment as a private teacher and that he continued to read avidly — Shakespeare and the other English poets and Alexander Chalmers' fortyfive-volume edition of the British Essayists "without interruption" (p. 21). Of the living writers he preferred Byron and Scott and thought Waverley the best novel published in thirty years. In the late spring of 1814 Carlyle heard of an opening for a mathematics teacher at the Annan Academy and decided to compete for it. He appeared for an examination before Thomas White, a mathematician and rector of the Dumfries Academy, and was selected. He went

Introduction

11

to work immediately and performed his duties well. But before his two years there were over he grew to hate Annan and was well on his way to hating teaching. He felt uncomfortable, out of place, and excepting Mr. Church and the Reverend Dr. Duncan, into whose households Johnstone and Mitchell introduced him, made no new friends and out of shyness and pride sought none. His only attraction to Annan was the relief his £60 or £ 7 0 of yearly salary gave his generous father. In spite of his loneliness and his proximity to home he seems to have stuck to his work until near the end of the year. But shortly before Christmas he journeyed to Edinburgh with Mitchell to deliver his first discourse, a trial sermon on the uses of affliction from Psalm 119:67, stayed a week visiting friends, and spent the first few days of the new year in Ecclefechan with his family before returning to Annan. With Thomas now earning his own way and Alexander able to help out, with a yearning to return to the land particularly of late years when "universal Poverty and Vanity made show and cheapness . . . be preferred to Substance" ( Reminiscences, I, 49), James Carlyle laid down his mason s tools and moved his family to Mainhill, a high wind-swept farm two miles northwest of Ecclefechan. He took the lease of it at Whitsunday 1815 from General Matthew Sharpe (d. 1845), laird of the Hoddam estates, M.P. for Dumfries from 1832 to 1841, and the brother of Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe ( 1781?-1851), the life-long friend of Scott. The farmhouse was a low, one-story, whitewashed cottage, whose three ceilingless rooms all had to serve as bedrooms for its nine regular occupants and for Carlyle when he was home. The borders of the farmyard were marked by the house itself, a stable, a cowbyre, and a combined wash house and dairy. Mainhill would be the family's home for the next ten years, where James and Alexander especially would eke a hard living out of the wet clayey soil, where Mrs. Carlyle and her daughters would tend the poultry and cows and take their turns in the fields at harvest time, and where Carlyle would spend his vacations and study German and complete his translation of Wilhelm Meisters Apprenticeship. But for the present Carlyle attended to his duties in Annan and worked on his second exegesis, a discourse on the question of natural religion. He went to Edinburgh just before Christmas to read the paper, undoubtedly enjoyed the compliments he received on it, and with a free

12

INTRODUCTION

mind visited again his college friends for a week before returning to the routine of schoolmastering. Before he left Edinburgh he met the man who became his closest friend. Edward Irving, a brilliant student and teacher, the inspired minister of Hatton Garden Chapel and founder of the Holy Catholic Apostolic Church, who was excommunicated first by the London presbytery for his approval of the "tongues" and later by the Church of Scotland for heresy, was born August 4, 1792, to Gavin Irving, a prosperous Annan tanner, and Mary Lowther Irving. As a boy Irving attended a school managed by Margaret Paine, a relative of Thomas Paine, and from there went to the Annan Academy. He joined Adam Hope's band of seceders on their Sunday walks to the Ecclefechan Meeting House, where, Carlyle later conjectured, he must have often enough sat with him. In 1805 he entered Edinburgh University, and in April or May 1808, the year before he was graduated M.A., returned to Annan to pay his respects to his old teacher. Adam introduced him to Carlyle's Latin class: "We were all of us attentive with eye and ear, — or as attentive as we durst be, while, by theory, 'preparing our lessons.' Irving was scrupulously dressed, black coat, ditto tight pantaloons in the fashion of the day; clerical black his prevailing hue; and looked very neat, self-possessed, and enviable: a flourishing slip of a youth; with coal-black hair, swarthy clear complexion; very straight on his feet; and, except for the glaring squint alone, decidedly handsome. We didn't hear everything; indeed we heard nothing that was of the least moment or worth remembering. . . . Shortly after . . . he courteously (had been very courteous all the time, and unassuming in the main), made his bow; and the interview melted instantly away. For seven years I don't remember to have seen Irving's face again" ( Reminiscences, II, 17-18). Carlyle heard, however, how Irving distinguished himself as a student at Edinburgh and as a teacher from 1810 to 1812 at Haddington and afterwards at Kirkcaldy. By June 1815 Irving had completed his studies as a rural divinity student and was licensed to preach at Kirkcaldy, but for the time being he chose to remain a schoolmaster. That year he also chose to spend his Christmas holidays in Edinburgh. One evening Carlyle was sitting in the Rose Street rooms of

Introduction 13 John Waugh, the son of Marion and Barbara Waugh, his predecessor at the Annan Academy and now a medical student at the university, when Waugh's friend Nichol (or Nicol), a mathematics teacher in Edinburgh, and Irving stepped in. Carlyle and Waugh welcomed the party, but what started out to be a pleasant evening began to turn the other way when Irving started asking Carlyle a number of questions about certain events of Annan society. Carlyle grew uneasy from his inability to answer and annoyed by Irving's conscious air of superiority. Soon Irving became annoyed as well and gruffishly blurted out, "You seem to know nothing!" Carlyle, his dander well up, exploded, "Sir, by what right do you try my knowledge in this way? Are you grand inquisitor, or have you authority to question people, and cross-question, at discretion? I have had no interest to inform myself about the births in Annan; and care not if the process of birth and generation there should cease and determine altogether!" Nichol, who would be put out of business by such a phenomenon, added that that would never do for him, and the ensuing laughter relieved the tense atmosphere. Although Irving did not hide his wounded feelings from Carlyle for the short while the evening lasted, neither he nor Carlyle ever brought up afterwards this small unpleasantry of their first meeting. Nor was there, Carlyle concluded, ever "another like it between us in the world" ( Reminiscences, II, 23-24). In spite of Irving's success in Kirkcaldy, a number of his patrons resented his severe ways with their children. The upshot was they decided to buy off the headmaster of a second school, put Irving there, and apply to Professors Christison and Leslie, who had sent them Irving, for a replacement. Christison and Leslie recommended Carlyle and at the same time suggested he go over to Kirkcaldy on his vacation in August to take a personal view of things. Unexpectedly he had to go in July to express his condolences to Adam Hope on the death of Mrs. Hope. Irving was there on the same mission, and in his generous welcome and offer of future hospitality Carlyle found promise for a future friendship. He also found promise in Kirkcaldy and accepted the town council's proposal of a one-year conditional appointment at £80 annually. He gave Annan notice and left to spend a few weeks with his family. He left Mainhill November 13 for ten

14

INTRODUCTION

days in Edinburgh, then crossed over to Kirkcaldy, took up residence in the Kirkwynd near the house in which Adam Smith wrote his Wealth of Nations, and on November 25, 1816, opened his school. Carlyle spent most of his free time that winter either with Irving or using his library. One high point of the season was Alexander's coming to stay with him and attending his school. Another occurred in March, when while with Irving in Edinburgh he allowed his "last feeble tatter of connection with Divinity Hall affairs or Clerical outlooks . . . to snap itself, and fall definitely to the ground." Dr. William Ritchie (1747-1830), professor of divinity at Edinburgh from 1809 to 1828 and minister of the High Church of St. Giles from 1808 to his death, was not at home when Carlyle called to enroll again. "Good," he exclaimed, "let the omen be fulfilled!" (Reminiscences, II, 39). Spring and summer brought with them long walks with Irving along the Kirkcaldy beaches at twilight, rambles in the neighboring woods, strolls to Dysart and Wemyss, and a memorable Saturday pilgrimage to Dunfermline to hear the Reverend Dr. Thomas Chalmers (1780-1847) preach the next day. Once they struck out for Ben Lomond to see the military tents and equipment of a trigonometrical survey, another time to Inchkeith with Irving's assistant Donaldson, a nephew of Professor Christison. Over the August vacation, with one Pears, a schoolmaster at Abbotshall, and James Brown, Irving's successor at Haddington, they went on a walking tour to the Trossachs and Loch Katrine, Carlyle and Brown breaking off there for Loch Lomond, Tarbet, Roseneath, and Greenock. The two parties met up at Glasgow, where Irving and Pears had gone directly, and went by canal boat to Paisley. Pears left for Dunse and home; the other three went on to see Robert Owen's model school at New Lanark and descend into the mines at Lead-hills. Once in Annandale, Irving struck off for his father's house, Carlyle and Brown for Mainhill. Finding Mrs. Carlyle ill, Brown went immediately away. In September, after their mother had recovered, Alexander drove his brother as far as Moffat, and within two days Carlyle was back at his desk. Although the society of Kirkcaldy was more attractive to Carlyle than that of Annan had ever been, he and Irving preferred to enter into little of it. Some friendly households they did join, however. One was William Swan's (d. 1833), yarn merchant, shipowner,

Introduction 15 bank agent, and provost from 1814 to 1815, 1820 to 1821, 1830 to 1831, whose son Patrick Don (1808-1889) was Carlyle's student and later became provost himself and preserved his old classroom as a memorial to his teacher. Another was the Reverend Mr. John Martin's, whose daughter Isabella was engaged to Irving. A third was Mrs. Elizabeth Usher's (1759-1838), widow of the Reverend Mr. John Usher (d. 1799) and aunt and foster mother of Carlyle's first love. Margaret Gordon (1798-1878), perhaps one of the originals for Blumine of Sartor Resartus, was one of Irving's former pupils, and he introduced Carlyle to her in the fall of 1818. She was, Carlyle recalled, "of the fair-complexioned, softly elegant, softly grave, witty and comely type, and had a good deal of gracefulness, intelligence and other talent. Irving too, it was sometimes thought, found her very interesting, could the Miss-Martin bonds have allowed, which they never would. To me, who had only known her for a few months, and who within a twelve or fifteen months saw the last of her, she continued for perhaps some three years a figure hanging more or less in my fancy, on the usual romantic, or latterly quite elegiac and silent terms, and to this day there is in me a goodwill to her, a candid and gentle pity for her, if needed at all" (Reminiscences, II, 57-58). The relationship might have amounted to more than it did had it not been for her aunt's insistence that she dissociate herself from one with such limited outlooks. In March 1820, when Carlyle came up from Edinburgh to call, she reluctantly bade him goodbye. Mrs. Usher shortly took her to her mother in London, and four years later she married Alexander Bannerman (1788-1864) of Aberdeen, who became M.P. for Aberdeen and governor of Newfoundland. Also in the fall of 1818 the Kircaldy episode for both Carlyle and Irving came to a close. They were sick to death of teaching and resolved to give it up at all costs. Irving made plans to go to Edinburgh and try for an appointment in the church. Carlyle decided to return to the university, possibly to study law. In August they made a last walking tour together, this time through the Peebles-Moffat moor country to Mainhill. Carlyle apparently did not mention his plans to his parents while he was home, but in haste wrote his father of them when upon his return to Kirkcaldy September 2 he found that an incompetent had enticed away many of his pupils. As James Carlyle

l6

INTRODUCTION

had quietly respected his son's decision when he declined further study toward the ministry, so now he respected this step and at least did not voice his disapproval. Carlyle got away from Kirkcaldy sooner than he expected to and by November 27 was writing Mitchell from his small room in Davie's lodging, 3 South Richmond Street. Although the dyspepsia he suffered from for the rest of his life had now come upon him and he was otherwise beginning what he later called his "four or five most miserable, dark, sick, and heavy-laden years" (Reminiscences, II, 59), for the moment he was buoyant. He had his savings of £.70 and knew he could find a pupil or two to augment it if it came to that. He believed himself capable of literary hack work at least and to that end had secured from the Reverend Dr. Duncan letters of introduction to Brewster and Bailie Waugh of Edinburgh, who was making plans even then for his short-lived New Edinburgh Review. And he had Irving, who had taken rooms on Bristo Street, and other friends for company. Leslie advised him toward engineering, but he chose instead to enroll in Professor Jameson's course in mineralogy and consider the law a little further. He spent Christmas with Irving in Fifeshire, and about a month after his return wrote the first letter in this collection to Alexander at Mainhill.

•S co ε .JS* ω

• A á l i

«

-g ' co J2

S 5

A I », ¡8

ε s

-ìà

- I S £ S

H tfr 2

< 8

O) 10 < 'S 2• s ; Η ι

_ in «ç; " -— « β ä t- M j l , Λ -H

¡3 H

S! M Oi

Ê S

8 I (Ν «i Ä

I «s îï S bo S s

5

ta

ä oí ^ # 1 7 6 4 . 2 6 3 ; November 1, 1823, from Belcat Hill, MS: N L S # 1764.267. 5. Auld Reekie has for long been the nickname of Edinburgh. 6. Boyd, who was to publish John Carlyle's Paul and Virginia, from

the French of St. Pierre, and Elizabeth, by Madame Cottin. New Trans-

lations. With Prefatory Remarks by }. McDiarmid (1824). See Edwin W. Marrs, Jr., "Carlyle, Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, and Madame Cottin," Victorian Newsletter (to be published).

• Carlyle amplified his way of life at Kinnaird during the months that followed in a fragment of reminiscences published in EL, p. 275: "I lodged and slept in the old mansion, a queer, old-fashioned, snug enough, entirely secluded edifice, sunk among trees, about a gunshot from the new big House; hither I came to smoke about twice or thrice in the daytime; had a good oak-wood fire at night, and sat in a seclusion, in a silence not to be surpassed above ground. I was writing Schiller, translating Meister; my health, in spite of my diligent riding, grew worse and worse; thoughts all wrapt in gloom, in weak dispiritment and discontent, wandering mournfully to my loved ones far away; letters to and from, it may well be supposed, were my most genial solacement. At times, too, there was something of noble in my sorrow, in the great solitude among the rocking winds; but not often." He asked the Bullers for a respite from that regimen and solitude, took his leave July 11, attended to some business in Edinburgh, and within the week was home and spreading freely among his family his earnings of £.300. He returned refreshed August 21 and went eagerly back to work. His only interruption occurred from October 17 to 19, when Irving and the former Isabella Martin, his bride of five days, visited him as they passed through the region on their wedding trip. By October 21 he had started the second part of the Schiller essay, and on November 24 completed it. As busy as he was he took the time to answer a letter from Alexander. ·

148

APPRENTICESHIPS

44· Kinnaird House, 2d November 1823 My Dear Alick — Having an hour and a half at my disposal today, and an opportunity of conveyance, I hesitate not, though rather stupid, to sit down and send you some inkling of my news. This is the more necessary, as it seems possible enough that ere long some change may take place in my situation; of which I would not have you altogether unapprised. Your little fragment of a letter was gratifying by the news it brought me that you are busy in your speculations, lucky hitherto, and bent on persevering. I cannot but commend your purpose. There is not on the earth so horrible a malady as idleness, voluntary or constrained. Well said Byron: "Quiet to quick bosoms is a hell." 1 So long as you are conscious of adding to your stock of knowledge or other useful qualities, and feel that your faculties are fitly occupied, the mind is active and contented. As to the issue of these traffickings, I pray you, my good boy, not at all to mind it. Care not one rush about that silly cash, which to me has no value whatever, except for its use to you. Pride may say several things to you; but do you tell her she has nothing to meddle or make in the case: I am as proud in my own way as you; but what any brethren of our Father's house [may possess] I look on as a common stock, mine as much as theirs, from which all are entitled to draw, whenever their convenience requires it. Feelings far nobler than pride are my guides in such matters. Are we not all friends by habit and by nature? If it were not for Mainhill, I should still find myself in some degree ahne in this weary world. Jack's German "all goes well" 2 appeared on the newspaper last but one: I have vainly sought for it on the last. I suppose he is gone to Edinburgh, or just going; and I hope ere long to have that solacing announcement repeated more in detail. I understand the crop is now in the yard; I trust that it bids fair to produce as it ought; that you have now got in the potatoes also, and made your arrangements for passing the winter as snugly as honest hearts and active hands may enable you. Above all, I trust that our dear Mother and the rest are

1823, Kinnaird House

149

enjoying that first of blessings, bodily health, without which spiritual contentment is a thing not once to be dreamed of. As for us of Kinnaird, we are plodding forward in the old inconstant and not too comfortable style. The winter is setting in upon us; these old black ragged ridges to the west have put on their frozen caps, and the sharp breezes that come sweeping across them are loaded with cold. I cannot say that I delight in this. My "Bower" is the most polite of bowers, refusing admittance to no wind that blows from any quarter of the ship-man's card. It is scarcely larger than your room at Mainhill, yet has three windows and of course a door; all shrunk and crazy: the walls too are pierced with many crevices; for the mansion has been built by Highland masons, apparently in a remote century. Nevertheless I put on my gray duffle sitting jupe; I bullyrag the sluttish harlots of the place, and cause them make fires that would melt a stithy. Against this evil, therefore, I contrive to make a formidable front. . . . I believe I mentioned to Jack that they had printed a pitiful performance of mine, Schiller's "Life," Part I., in the London Magazine; and sent very pressingly for the continuation of it. In consequence, I threw by my translation, and betook me to preparing this notable piece of Biography. But such a humour as I write it in! . . .3 What my next movements may be, I am unable to say positively. I must have my Book (the translation) printed in Edinburgh, but first it must be ready. It is not impossible that I may come down to Mainhill for a couple of months till I finish it. Perhaps after all I may give up my resolution and continue where I am, though on the most solemn deliberation, I do not think such a determination can come to good. Next time I write you will hear more. Anyway you are likely to see me ere long: I must be in Edinburgh shortly, to arrange with Brewster and others. Whether I leave this place finally or not, I have settled that poor Bardolph4 must winter at Mainhill. A better pony never munched oats than that stubborn Galloway. But they are hungering him here; he gets no meat but musty hay and a mere memorial of corn every day; so he is very faint and chastened in spirit compared with what he was. Out upon it! the spendthrift is better than the miser; anything is better. . . . I meant to write to my Father; but this stomach has prevented me.

150

APPRENTICESHIPS

Give my kindest love to him and our good Mother, and all the souls about home. Tell my Mother to take no anxiety on herself about me, lest anything serious happen to me: at present, two weeks of Annandale air would make me as well as she has seen me for many years. Good-night, my dear Alick! My candle is ht, yet I have not dined, the copper captain being out riding. Write to me the first moment you have, and advise Jack to do it if with you still. — I am, always your faithful Brother, T. Carlyle MS: unrecovered. Text: EL, pp. 290-293. 1. Byron, Childe Harold's Pilgrimage III.370. 2. That is, "ganz wohl," written on the cover. This manner of letting the recipient of the paper know the condition of the sender the family normally accomplished by a system of strokes drawn under the address: two meant "all is well"; three, "got your letter." 3. Norton's omission here would seem to be the following, which is published in Froude, I, 203-204: "This blessed stomach I have lost all patience with. . . . The want of health threatens to be the downdraught of all my lofty schemes. My heart is burnt with fury and indignation when I think of being cramped and shackled and tormented as never man till me was. 'There is too much fire in my belly,' as Ram Dass said, to permit my dwindling into a paltry valetudinarian. I must and will be free of these despicable fetters, whatever may betide. . . . I could almost set my house in order, and go and hang myself like Judas. If I take any of their swine-meat porridge, I sleep; but a double portion of stupidity overwhelms me, and I awake very early in the morning with the sweet consciousness that another day of my precious, precious time is gone irrevocably, that I have been very miserable yesterday, and shall be very miserable to-day. It is clear to me that I can never recover or retain my health under the economy of Mrs. Buller. Nothing, therefore, remains for me but to leave it. This kind of life is next to absolute starvation, only slower in its agony. And if I had my health even moderately restored, I could earn as much by my own exertions." Ram Dass is unidentified. 4. Who was "bought for me at Lilliesleaf Fair by my dear Brother Alick" (Reminiscences, II, 109).

1823, Kinnaird House

151

45· Kinnaird House, 25th November, 1823 My dear Alick, I need not say with what pleasure I received your kind and spirited and affectionate letter. It is sweet to me to hear that you are all as you should be; sweet to know that you all truly sympathize with me in my afflictions, tho' it be little in your power or in human power to help them. You said you would come for the pony at a moment's warning: I am going to take you at your word. Before you can read this notice, I am on the road for Edinburgh, where I shall be waiting to receive you, and deliver up this faithful steed into your hands. Jack told me you had got another galloway; a circumstance that made me pause in my intention of sending this Bardolph down to winter with you; but I reflected that perhaps it might be easy for you to sell the present one, and reinstate Dolph in his rights and privileges of carrying [you] up and down the country in your trafficking expeditions, and so working for his oats and hay as he is in duty bound. If it is not so, you may let me know by letter while I am in Edinburgh; in which case I may perhaps take the beast with me again — that is if I return myself. There was a Notary Public at Broughty-ferry, when I was down seeing Johnstone — wanting to buy it, being struck by the freedom of its paces as he saw me riding it about. The Landlord of the Inn there, a hash if there is one, said it was a "virry fine beast Sir"; and as for the saddle — that could not be matched in Angus. The truth is, however, I want to see yourself in Edinburgh, that the whole three of us may hold solemn council on what is farther to be done not with the horse alone, but with his rider. The Bullers and I have had some farther conversation on the subject of my going or staying: they are to give me a letter to George Bell,1 the celebrated Surgeon in Edinburgh, who is maturely to investigate the state of my unfortunate carcass, and see if nothing can be done to aid me. By his advice I must in some degree be guided in my future movements. They are anxious of course that I should return; but fully prepared for my quitting them should that seem necessary; they have in full written by my advice to Dr Brewster about providing them a succès-

152

APPRENTICESHIPS

sor, and it is one of my engagements to communicate with Brewster on this point. I do not think it likely that he will find any suitable person; in which case, should I retire from duty, the young men here must go to Cambridge or some other such seminary. They are all veiy kind to me here, and would do any thing to make me comfortable, and take me back on almost any terms. I confess I am greatly at a loss what to do; and for that cause if there were no other, I am ill at ease. That some change must be made in my arrangements is clear enough: at present, I am bowed down to the earth with such a load of woes as keeps me in continual darkness. I seem as it were dying by inches;2 if I have one good day, it is sure to be followed by three or four ill ones. For the last week, I have not had any one sufficient sleep; even porridge has lost its effect on me. I need not say that I am far from happy. — On the other hand, I have many comforts here; indeed I might live as snugly as possible, if it were not for this one solitary but all-sufficient cause. I know also and shudder at the miseries of living in Edinburgh, as I did before; this I will not do. "On the whole," as Jack says, it is become indispensible that I get back some shadow of health. My soul is crippled and smothered under a load of misery and disease, from which till I get partly relieved, life is burdensome and useless to me. We must all consult together, after I have heard the opinion of the "Cunning Leech," 3 who I suppose will put me upon mercury; and see what is to be done. If I were well, I fear nothing; if not, everything. You need not think from all this that I am dying; there does not seem to be the slightest danger of that: I am only suffering daily as much bodily pain as I can well suffer without running Wud. So having finished this "Life of Schiller Part. II." and sent it off to London yesterday, I determine to set off for Edinburgh on Thursday morning; I shall be there on Friday. It must be owned, My dear Brother, this is a confused enough piece of business, and described with equal perplexity. Nevertheless, you will not fail to make the best of my scrawl — which I write after dinner (when I am always sickest) and in hourly expectation of the Post. If you cannot well be spared at present, write to me in Edinburgh without loss of time, and I will either go back with the horse, or bring it down to you myself, or send it by Frank Dickson, who is

1823, Kinnaird House

153

to meet me in the City. Jack's Lodgings you know are at 35. Bristostreet. If you come in person, you must travel by the Coach. Your best plan is to mount early on Saturday morning, and overtake the vehicle at Moffatt: you will get in by that means for twelve or thirteen shillings — for which I shall gladly be in your debt. Jamie may accompany you so far, or come up after you to take back the horse you ride on. You will find us at Bristo street waiting for you. If you cannot come till Monday or later, it makes no kind of matter; I shall not be gone at any rate till the end of the week: only by that means, I should get less of your company. — Tell our Father and Mother how it stands; but forbid them to concern their minds about me; for this is only a temporary misfortune, which I shall yet gloriously triumph over. I have been a wae sight to them, first and last; but it shall not always be so. Present my kindest affection to all. Write to me if you think it best not to come; if otherwise, come — with your great-coat and spurs. I am ever your faithful Brother, T. Carlyle I have a tremendous shag-greatcoat of Charlie's to ride in. — Tell my Mother. The ride will almost mend me, I know. I have written to Jack just now to expect [me]. On Thursday-night, I shall likely stay with Will. Bretton,4 who has a spare bed. Published in part: EL·, pp. 295-296. 1. ( 1 7 7 7 - 1 8 3 2 ) , who is mentioned in the DNB under the name of his more distinguished father, Dr. Benjamin Bell ( 1 7 4 9 - 1 8 0 6 ) , an authority on ulcers. 2. Matthew Henry, Commentaries, Psalm LIX. 3. Cf. Butler, Hudibras I.ii.245. 4. Unidentified, but there is a farm called W[est?] Bretton one and one-half miles southwest of Kirtlebridge.

154

APPRENTICESHIPS

46.

From James Carlyle, Margaret Aitken Carlyle, and Alexander to Carlyle Mainhill, 28th December 1823 Dear Son — I have taken the pen in my hand to write a few lines to you to tell you how I come on, but indeed I, for some years, have written so little that I have almost forgotten it altogether, so I think you will scarce can read it, but some says that anything can be read at Edinburgh,1 so I will try you with a few lines as is, and if it is not readable I will try to do better next time. I begin then with telling you the state of my own health, which I am glad to say is just as good as I could wish for at my time of life, though frailty and weakness which goeth along with old age is clearly felt to increase; but what can I say? that is natural for all mankind. But I must not leave this subject that way, but tell you that I have not as yet taken the cold that I was troubled with in some former winters; and that I can sleep sound at night and eat my meat and go about the town,2 and go to the meeting house on the Sabbath Day, so that I have no reason for complaint. I go on next to tell you about our Crop, which doth not turn well out, but our Cattle is doing very well as yet, and we do not fear to meet the Landlord against the rent day. I was down at Ecclefechan this day, and was very glad to find a letter3 in the office from you, as we were beginning to look for one, and Sandy was preparing a letter for you, and we thought best to join our scrawls together. If there is any news, I leave that for Sandy to tell you all these things, and I will say no more at this time, but tell you that I remain, dear son, your loving Father, Jas. Carlyle Dear Tom — I need not tell you how glad I was to receive your kind letter, for I began to be uneasy. . . . O my dear Son, I have many mercies to be thankful for, and not the least of these is your affection. We are all longing for February, when we hope to see you here, if God will. Do

1823, MainhiU 155 spare us as much time as possible when you come down; in the meantime let us be hearing from you often. — Your affectionate Mother, Margaret Carlyle My dear Brother, As the great end of writting, namely the telling you of our welfare, is already attained by the mutual exertions of our Father and Mother the rest which remainith is of course of little importance and either may or may not be forthcomming as occassions serve. But I am unwilling that the sheet should go undarkened at least while I have the power of filling it; caring little in what manner so it be done at all. And first by way of endeavouring to gain this desirable end let me try to shape some sort of answer to your last letter which has been in our possession for nearly a fortnight now. I need hardly say how much we were pleased to hear of your safe arrival 4 at Kinnaird again in spite of all the little mishaps which ever and anone thwart the projects of the traveler. Your private idea of the fatal and fruitless passion of my old coach companion poor little Fyffe towards a nameless Damsel, is I can assure you perfectly in unison with my own. Scarcely had we passed only a few minits together when this very idea struck me, tho' I knew nothing of his history; and his interrogations and continual talking about "Miss Jane Welsh" served powerfully to confirm it. I had moreover shrewdness enough to gather that he regarded you as his deadlist rival, but with what propriety I could not say. And now as to this "wild scheme" of farming I realy know not well what to say, there is so much might be said on both sides of the question (as the old woman of the Howecleugh5 remarks when her child is hard beset in argument). In the first place we are all of us tired of living on this wild hill — our Father as much as any of us. And in the next place where shall we go to be better or rather have within ourselves the means of going, that is to say of taking a larger and far better farm. The answer is short and would to a vain man be painful to utter. We have not. But have not I as much? you would say to me I know well were you hearing this. You have and much more too thank Heaven; and also what is of more importance you have the goodness of heart or rather the wild and ex-

156

APPRENTICESHIPS

travagant generosity to lend it to us were we requiering it. But on the other hand there is something even in the mere idea of borrowing which tends in my opinion to lesson a man in his own estimation: not to speak of the great and mortifying risk of being unable to pay the thing when it might be wanted. And at any rate borrowing to any great extent is I suspect incompatable with the rules of friendship and independence of character. And moreover how is it certain that we should become either better or happier from having a drier and warmer situation to live on with perhaps less to live upon. We might appear better men in the eyes of our neighbours indeed because they thought us richer and be better able also to give you that accomodation withal which we would so gladly render were it in our power. But at best it is only in these critical times like a leap in the dark. And the Carnival project is still more uncertain. It is like leaping in black darkness where pitfals and quagmires abound if I may be allowed to say so. You know well my dear Brother that I would gladly go anywhere between the farthest nook of the Orkney's land to the Lizard Point6 again were it to serve you. But your present engagements are of a fluctuating a nature, and at farthest only of short duration, that peradventure in a short time it might cost you more pain to leave me like an alien turning the clod to [fi] 11 the hungry maw of some voracious miner in Cornwal, than it gave you pleasure at first on making me a farmer there. Here is an uncommon "lash" of nonsense for you destitute almost of meaning or visible motive unless indeed it show you how willingly I would add to the comfort and respectability of this farming of which I am proud of being a member, and also how unequal to the task I am; a thing which you knew somewhat before. Peace! Peace! I had many things to tell you and have now you see little room to tell them in. Schiller's Life and Cobbet's Economy7 you shall hear about next time. Did you notice in the paper 8 what horrible work has been carrying on among the dead here. The ringleader of those villans is one Bazel or Basie Forsyth an ugle thief hash this day as ever the Blessed Sun rose upon. He is fled. We are thankful to learn that you are again begun to sleep at night — even with the aid of drugs. Dolph is getting into excellent heart and will carry you in spring like the wirlwind. Your trusty Brother Alexr Carlyle

1824, Kinnaird

House

157

MS: Mr. and Mrs. Carlyle's portion of the letter, unrecovered. Text: EL, pp. 300-301. Alexander's portion of the letter, N L S # 1763.92-93. The last two lines of Mrs. Carlyle's note, from the word "possible" on, are on this MS. 1. "A neighbour's remark, after being unable to decipher what he himself had written, 'Let it go; they can read anything at Edinburgh' " (EL, p. 300). 2. See glossary. 3. See EL, pp. 299-300. 4. On December 10. See EL, p. 298. 5. A farm in St. Mungo parish, Dumfriesshire. 6. Carlyle apparently had mentioned the Bullers were considering going to Cornwall. 7. Cottage Economy; Containing Information Relative to the Brewing of Beer, Making of Bread, Keeping of Cows, Pigs, Bees, Ewes, Goats, Poultry . . . (London, 1822). 8. The Dumfries Weekly Journal of January 27, 1824, carries an account of the illegal disinterment of bodies in Ecclefechan. I was unable to locate the earlier report Alexander possibly referred to here.

47· Kinnaird House, 13th Jany, 1824 My dear Alick, I meant to have written sooner, but put it off till I should have more leisure, or something more interesting to communicate; and, as often happens in such cases, I am at last obliged to write when more hurried than ever, and considerably duller than I have been for a week. My silence I hope has given you no uneasiness; it ought not, if you kept in mind the maxim which I gave you some time ago, always to believe me well unless you heard the contrary. In fact there is or has been very little change in my health; I am better and worse just about as I used to be. I cannot say that I relish their mercury; and for the tobacco, which I have not touched for six weeks, there seems to be no great benefit attending this sort of abstinence.1 On the whole, however, one way or another, I think I have slept somewhat better and been less wretched for the last month than formerly. Here it is quite impossible that I should ever recover; but with better arrangements, I still have hopes.

158

APPRENTICESHIPS