Travels in the Tian'-Shan', 1856-1857

Source text translated from https://arheve.org/details/semenov-tyan-shanskiy-pp/puteshestvie-v-tyan-shan-v-1856-1857-god

137 22 816KB

English Pages 214 Year 1946

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Pyotr Petrovich Semenov-Tianshansky

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

TRAVEL TO TIEN SHAN IN 1856-1857 Memoirs Offered to the Soviet reader is the first edition of a complete description of the journey to the Tien Shan by the famous Russian geographer Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov, who later received the addition of Tien-Shansky to his surname, will allow you to read one of the remarkable pages in the development of Russian science. P.P. Semenov was the first of the researchers to penetrate deep into the mountainous country of the Tien Shan, mysterious to his contemporaries. He was the first to draw a diagram of the Tien Shan ridges, explored Lake Issyk-Kul, discovered the upper reaches of the Syr Darya, saw the Tengri-Tag mountain group and the majestic Khan-Tengri pyramid, the first to reach the glaciers originating in the Tengri-Tag group, the first to establish that the Chu River does not originate from Issyk-Kul, as scientists contemporary to Semenov thought, he refuted the opinion of A. Humboldt about the volcanic origin of the Tien Shan, he proved that eternal snow lies on the Tien Shan at a very high altitude, he was the first to establish vertical natural belts of the Tien Shan. Shan, discovered dozens of new plant species unknown to science, and was the first to see living argali. But it is not only the discoveries of new things that put Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov-Tyan-Shansky in the first rank of world scientists. He carried out his expeditions using a completely new method of geographical research. Further we will dwell on it in more detail, but here we will say that this technique was the foundation on which other studies that glorified Russian science, pushing it forward in world geography, relied - Przhevalsky, Roborovsky, Kozlov, Potanin, Pevtsov and others. The circumstances of Pyotr Petrovich’s life were such that a trip to the Tien Shan in 1856-1857. remained his only major field study. Expedition 1860-1861 he failed to implement. But being from 1873 to 1914. chairman of the Russian Geographical Society and being mostly in St. Petersburg, Pyotr Petrovich put his thoughts, his dreams, his aspirations into dozens of distant expeditions, he conveyed his ideas to Przhevalsky, Potanin, Mushketov, Krasnov, Berg and many other researchers of Central Asia and Central Asia, and in their works, to some extent, the broad geographical ideas of Pyotr Petrovich, his organizational talent, his courage, and the indomitable power of scientific generalizations are embodied. P. P. Semenov-Tyan-Shansky, without a doubt, is a classic of Russian geography, and from his works our youth can and should learn the complexity of geographical research, the purposefulness of scientific work, the simplicity and imagery of geographical characteristics, the breadth and boldness of generalizations based on carefully collected factual material. ”Journey to the Tien Shan” is interesting not only for geographers. A wide variety of readers will enjoy reading the wonderful descriptions of the travels of Semenov-Tyan-Shansky. Even before traveling to Tianynan, in 1856, Pyotr Petrovich wrote in the preface to the first volume of “Earth Studies of Asia” by Karl Ritter: “Until domestic scientists put the content of science into the forms of their native language, they will remain a caste alien to domestic development Egyptian priests, perhaps with knowledge and high aspirations, but without a beneficial influence on their compatriots.” “The desire of every 1

scientist, if he does not want to remain a cold cosmopolitan, but wants to live one life with his compatriots, should be, in addition to trying to move human knowledge absolutely forward, also a desire to introduce its treasures into people’s lives.” “Journey to the Tien Shan” was written exactly like that, to enter into the life of the people - in beautiful Russian language, colorful, strong and simple, with clear and deep thoughts. Semenov-Tyan-Shansky’s book inspires love for the homeland, pride in its brave and energetic researchers who were the first to discover to science those wonderful corners of the country where we now observe the intense economic, political, and cultural life of the Soviet people. “Travel to Tien Shan” was written by Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov-Tyan-Shansky already at an advanced age - in the 81st year of his life according to diaries of 1856-1857. During the day of work, P.P. processed a day from his travel diaries. In terms of accuracy and freshness of records, ”Travel to the Tien Shan” is a valuable historical document reflecting the life of Russia almost a hundred years ago. Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov was born in 1827 into the landowner family of the Semyonovs in the Ryazan province. It can be assumed, as, for example, L. S. Berg does, that Semyonov’s passion for travel and love for geography arose in early childhood. This conclusion is suggested by Semyonov’s own memoirs, in which, in the decline of his life, he recalls with deep feeling his childhood impressions of the nature around him, his first survey of a garden, taken at the age of 10, and his first children’s excursions. From 15 to 18 years old, Semenov studied at the military school of guards ensigns and cavalry cadets, where, as in childhood, he was especially interested in natural sciences. After graduating from this school, he abandoned his military career and entered the university as a volunteer. In 1851, Semenov defended his master’s thesis on botany, the material for which he collected in 1849 during botanical research in the black earth provinces. Semenov’s youthful years coincided with a significant event in the history of Russian geographical science. In 1845 the Russian Geographical Society was founded. Among the founders of the society were such major geographers as K. I. Arsenyev, F. P. Litke, I. F. Kruzenshtern, K. M. Baer, A. I. Levshin and others. By the end of the first year of the Society’s activity, there were 144 members. In 1849, young Semenov was elected a member of the Society. All stages of Semenov’s further geographical activity are inseparably connected with the history of the Russian Geographical Society. From 1850 to 1856 P.P. Semenov was the secretary of the physical geography department of the Society, from 1856 to 1860 he was assistant to the chairman and from 1860 to 1873 he was the chairman of this department. In 1873, P. P. Semenov was elected chairman of the Society and remained its leader until the end of his life - 1914, that is, for 41 years. Yu. M. Shokalsky, who became the chairman of the Geographical Society after Semyonov’s death, subsequently wrote about Semyonov: “For us, old workers of the Society, the names “Pyotr Petrovich” and “Geographical Society” are inseparable.” Another major Russian geographer, L. S. Berg, who is currently the chairman of the Geographical Society, spoke about Semenov in almost the same words: “In the minds of our old members of the Society, the Geographical Society and Pyotr Petrovich are inseparable and inseparable concepts, it’s almost synonyms”. There is no doubt that work at 2

the Geographical Society was crucial for the rapid formation of P. P. Semyonov as a geographer. He himself subsequently brilliantly described the significance of such activity in his memoirs about one of the members of the Geographical Society - N.A. Milyutin, whose vigorous activity, according to Semyonov: ”... was for him, one might say, the equivalent of a higher academic education. A whole series of things he heard he in the Society of Scientific Conversations and Communications, personal relations with first-class Russian scientists and the use of an extensive library completely replaced the reading of professorial lectures for him, and his own scientific work undertook helped him to master strict scientific research methods.” These words, with a certain right, could be applied to Semyonov himself, with the difference that his initial activity in the Geographical Society would have to be called not an equivalent (replacement) of academic higher education, but a second specialized education after St. Petersburg University. Already in the first years of P. P. Semenov’s stay at the Geographical Society, a distinctive feature of all his further scientific activities appeared - the remarkable versatility of his scientific interests. Semenov’s first independent works related to various branches of the natural sciences. In his geological work related to European Russia, P. P. Semenov, according to V. A. Obruchev, “for the first time stated the distribution of the central Russian Devonian strip beyond the Don and Voronezh rivers.” In “The Don Flora” Semyonov summarized the results of his botanical research that covered the Don basin. In his work on New California, he gave a geographical description of a vast territory based on the study of literary sources. Semyonov’s speeches at the Russian Geographical Society, his notes and reviews related to a wide variety of issues - from cosmogony to zoological geography. The most significant of Semyonov’s early works, completed before the trip of 1856-1857, is the translation of the first volume of Ritter’s ”Earth Studies of Asia” and the creation of ”Additions” to it. In 1850, the Council of the Geographical Society decided to translate certain parts of Ritter’s “Earth Science of Asia” relating to Asian Russia and the countries adjacent to it. This translation should have been supplemented by new sources accumulated after the publication of ”Earth Studies of Asia”. Translation and addition of parts relating to Southern Siberia and all of inner Chinese Asia was undertaken by Semyonov. A significant part of the translation work was done by him back in 1851-1852. Later the work continued abroad. Semyonov was abroad from 1853 to 1855. At the University of Berlin, he attended lectures by Ritter and Dove, worked a lot on geology, as a student of Beirich and Rose and as an assistant to Beirich in his summer work on geological surveys. During these same years, he made numerous excursions, which were of particular importance in his preparation as a traveler-explorer of mountainous countries. “...I was attracted to the mountains, which I, having fully studied geography in theory, had never seen in my life,” he recalls in his memoirs. Semyonov visited the Harz, Semigorye, and Vosges. In the autumn of 1853, he “traveled a lot on foot in Switzerland, especially in the Bernese Alps and on lakes Thun, Brienz and Vierwaldstedt.” Semenov was in Switzerland for the second time in the spring of 1854. This time he visited Lake Vierwaldstedt and the mountain passes leading to Italy and Wallis: Saint Gotthard, Saint 3

Bernard, Grimsel, Furku and others, making all his journeys on foot, without a guide, with a compass and Baedeker” and often traveling up to 50 miles in one day. In 1854, Semenov observed the eruption of Vesuvius, which, even before its eruption, made 17 ascents. During his stay abroad, Semyonov continued to work on the “Additions” to the “Geography of Asia”. Karl Ritter, “having met me, fell in love with me extremely as his translator and commentator, and sent to me everyone interested in the geography of the walled Chinese Empire and Central Asia in general, telling them that I was more familiar with the current state of geographical information about these parts of Asia, than himself,” this is how Semenov later recalled these years. In the spring of 1855, Semyonov returned to Russia. In St. Petersburg he completed his work on the ”Additions” and published several articles on various topics. The publication of the first volume of ”Earth Studies of Asia”, with additions written by him, was published in 1856, Semyonov provided an extensive ”Translator’s Preface”, remarkable, in particular, because it outlined Semyonov’s views on geography and gave a definition of geography as a special science. In the ”Translator’s Preface” Semyonov presented his views on geography, as an already established scientist to a large extent. This, in the most general terms, is the biographical outline that must be kept in mind when speaking about the formation of Semyonov as a geographer in the first years of his literary and geographical activity, preceding his trip to the Tien Shan. 1856-1857 occupy a very special place in Semenov’s geographical activities. These are the years of his famous journey, which marked the beginning of subsequent expeditions to Central Asia by a galaxy of remarkable Russian traveler-geographers of the second half of the 19th century: Przhevalsky, Roborovsky, Kozlov, Potanin, the Grumm-Grzhimailo brothers and others. The information about the Tien Shan that European geographical science had at its disposal by the middle of the 19th century is well characterized in a few words by G. E. Grumm-Grzhimailo: “By the fifties of the last century, the entire amount of European information about the Heavenly Ridge of the Chinese was provided by Ritter’s Asia, and clearly - d’Anville’s maps in Klaproth’s later revision. This knowledge, if not equal to zero, was insignificant...” How insignificant this knowledge was can best be seen from a simple listing of the materials on which geographers based their descriptions and cartographic images of the Tien Shan. Let us use a brief enumeration of them made by Semyonov himself in one of his articles about the Tien Shan: “... the facts developed... by the best scientists of our century were meager and insufficient; they were recorded randomly and fragmentarily by people who passed through these countries not with scientific purposes and even completely alien to science, such as, for example, Chinese travelers, mainly from the Buddhist missionaries of the 4th-7th centuries, and bypass officials of modern times, and Russian-Tatar merchants who followed with their caravans for trading purposes two specific routes - to Little Bukharia or Kashgaria. Only the Chinese commission of the 18th century for cartographic survey of Xi-Yu (or western lands) during the reign of KyanLun, which determined even one astronomical point on Lake Issyk-Kul, could have been somewhat more scientific in nature, because in ”It was headed by European Jesuit missionaries. However, these latter, as far as I know, did not 4

leave any of their own reports about their routes near the Tien Shan system, and their maps, except for astronomical points, are based on the dry, unfounded routes of their Chinese assistants.” The greatest interest from Chinese sources was the evidence of a 7th century traveler. Xuan-tsang, who crossed the eastern Tien Shan from south to north through Musart, the valley of Lake Issyk-Kul and entered the valley of the Chu River. Xuanzang gave a brief, but for his time very meaningful and truthful description of the nature of the Tien Shan. About Lake Issyk-Kul, for example, Xuan-tsang wrote: “From east to west it is very long, from south to north it is short. It is surrounded on four sides by mountains, and many streams gather in it. Its waters have a greenish-black color and its taste is both salty and bitter at the same time. Sometimes it is calm, sometimes the waves are raging on it. Dragons and fish live in it together.” Of all the Chinese sources, descriptions of Xuan-tsang, as Krasnov aptly put it, “are the first and only source that is trustworthy and characterizes in detail the nature of the country.” Other original sources were distinguished not only by the extreme paucity of factual material, but also by its unreliability. “Mysterious Tien Shan” - this expression was as widespread in relation to the Tien Shan as the expression “terra incognita” in relation to Central Asia. Humboldt developed the theory of Tien Shan volcanism. The Tien Shan, according to Humboldt, was supposed to represent a high snowy ridge with alpine glaciers on its peaks and fire-breathing volcanoes located along the entire ridge, from Turkestan to Mongolia. The idea of the Tien Shan expedition arose in Semenov on the eve of his trip to Europe. He himself writes about this in the first volume of his memoirs: “My work on Asian geography led me... to a thorough acquaintance with everything that was known about inner Asia. I was especially attracted to the most central of the Asian mountain ranges - Tien Shan, which had not yet been touched by a European traveler and which was known only from scanty Chinese sources... To penetrate deep into Asia to the snowy peaks of this inaccessible ridge, which the great Humboldt, based on the same meager Chinese information, considered volcanic, and bring him several samples from the fragments of rocks of this ridge, and home - a rich collection of flora and fauna of a country newly discovered for science - this was what seemed the most tempting feat for me.” Semyonov considered his subsequent studies in geography and geology, excursions in the glacial regions of Switzerland and the study of Italian volcanoes primarily as preparation for a future trip. ”P.P. Semenov, preparing for the planned trip, paid special attention to the study of the most ancient (Paleozoic) formations, the distribution of which he expected in Central Asia, as well as to the petrographic study of crystalline rocks, but, bearing in mind Humboldt’s assumptions about the distribution of volcanic rocks and phenomena in the Tien Shan, considered it necessary to go to Italy in the fall of 1854, and stayed there for several months to study volcanic rocks and phenomena in the vicinity of Naples, where Vesuvius was erupting at that time” - this is how Semenov’s preparation for his trip is described in “History half a century of activity of the Russian Geographical Society.” During his stay in Berlin, Semyonov informed Humboldt and Ritter about his planned trip to the Tien Shan. Both of them, as Semyonov recalls, blessing him on the diffi5

cult path, “did not hide their doubts about the possibilities of penetrating so far into the heart of the Asian continent.” However, Semyonov was determined to achieve his goal. Returning to Russia, he completed the publication of the first volume of ”Geography of Asia” and received the consent of the Council of the Geographical Society to equip him for an expedition ”to collect information about those countries to which the next two volumes of Ritter’s Asia, already translated by him, belong, namely the volumes relating to Altai and Tien Shan,” he himself later wrote. Without directly informing anyone of his intention to penetrate the Tien Shan, Semyonov indicated that in order to add to the Geography of Asia, he needed to personally visit some of the areas described in the volumes he translated. At the beginning of May 1855, Semyonov went on an expedition. In June he was already in Barnaul. The reader will see a detailed description of the progress of the expedition after reading this book. However, to characterize the corresponding geographical generalizations of Semyonov, it is necessary to briefly dwell on individual stages of his journey. Initially, Semyonov expected to carry out research in Altai during the summer of 1856 and only then head to Issyk-Kul. However, a three-week illness in Zmeinogorsk forced him to limit his travel through Altai to an overview of its western outskirts in order to be able to penetrate Issyk-Kul during the fall. He visited the Ulbinskaya and Ubinskaya valleys, the most important mines, and, having climbed one of the highest squirrels near Riddersk - Ivanovsky, headed through Semipalatinsk to the Vernoye fortification, built shortly before his trip (the present city of Alma-Ata). “I slowly drove through the entire vast and interesting country from Semipalatinsk to the Kopal Fortification, stopping wherever the interests of the science of geology required it. In two places I managed to climb the tops of high mountains, close to the limits of eternal snow and covered with eternal snow spots, namely in the chain Karatau near Kopal itself and in the Alamak chain, far beyond Kopal near the Koksu River...” wrote Semyonov in his first letter sent to the Russian Geographical Society. From Verny, Semenov made two trips to Issyk-Kul. On his first trip, passing through the mountain passes of the Trans-Ili Alatau, he reached the eastern tip of Issyk-Kul. The route of his second trip to the western end of the lake passed through the Kastek Pass and the Buam Gorge. In his second letter sent to the Russian Geographical Society after completing this route, Semenov wrote: “My second big trip to the Chu River exceeded my expectations with its success: I not only managed to cross the Chu, but even reached Issyk-Kul this way, that is, its western extremity, on which no European has yet set foot and which has not been touched by any scientific research.” Before the onset of winter, Semenov still managed to visit Gulja and then again, passing through Semipalatinsk, he returned to Barnaul in November 1856. In the spring of 1857, Semenov again arrived in Vernoye together with the artist Kosharov (an art teacher at the Tomsk gymnasium), whom he invited to participate in the expedition. This time the goal of the expedition was to fulfill Semenov’s cherished desire - to penetrate deep into the Tien Shan mountain system. Having left Verny, Semenov reached the Santash plateau, from where the expedition moved to the southern shore of Issyk-Kul. Having reached the Zaukinskaya Valley, Semenov crossed the Terekey-Alatau 6

and through the Zauku Pass reached the source of Naryn. “Before the travelers spread out a vast plateau-syrt, on which were scattered small semi-frozen lakes, located between relatively low mountains, but covered on the tops with eternal snow, and on the slopes with the luxurious greenery of alpine meadows. From the top of one of these mountains, the travelers saw very clearly flowing from the syrt lakes spread out at their feet, the upper reaches of the tributaries of Naryn, the main source of which was located to the east-south-east from here. Thus, for the first time, the sources of the vast river system of Yaxartes were reached by a European traveler,” wrote P. P. Semenov in ”The History of Half a Century activities of the Russian Geographical Society”. From here the expedition set off on its return journey. Soon Semyonov made a second, even more successful ascent to the Tien Shan. This time the expedition route went in a more eastern direction. “Climbing along the Karkara River, a significant tributary of the Ili River, and then along Kok-Dzhar, one of the upper rivers of Karkara, the traveler climbed to a pass of about 3,400 meters, separating Kok-Dzhar from Sary-Dzhas...”. This difficult path, unknown to any European explorer of Asia, led Semenov to the heart of the Tien Shan - to the Khan Tengri mountain group. Having visited the sources of Sary-jas, Semenov discovered the vast glaciers of the northern slope of Khan Tengri, from which Sary-jas originates. One of these glaciers was subsequently named after Semenov. On the way back to the foot of the Tien Shan, Semenov took a different road, following the valley of the Tekesa River. That same summer he explored the Trans-Ili Alatau, visited the Katu area in the Ili Plain, the Dzhungar Alatau and Lake Ala-kul. Completion of the expeditions of 1856-1857. Semenov visited two mountain passes of Tarbagatai. It is well known that the correct choice of route is of paramount importance for the scientific value of geographical expeditions in unexplored countries. Semyonov’s research in the Tien Shan shows his remarkable ability to choose routes that are most valuable geographically. The most significant feature of these routes is that almost all of them passed primarily across the direction of the mountains, and not along the relatively more convenient longitudinal valleys for the traveler. One of the Tien Shan researchers at the end of the 19th century. Friedrichsen rightly notes that the expeditions of Semenov (and subsequently Severtsov) provided, thanks to this choice of route, mainly across mountain ranges, extremely valuable material about the configuration of the mountains. In “The History of Half a Century of Activities of the Russian Geographical Society,” Semenov evaluates his travels as “an extensive scientific reconnaissance of the northwestern outskirts of Central Mountainous Asia.” He pointed out the reconnaissance nature of his research back in 1856, describing his visit to the western tip of Issyk-Kul. “Of course, this trip, made with speed, forced by the dangers and hardships surrounding me, can only have the character of scientific reconnaissance, and not scientific research; but even in this form it will not remain without results for the geosciences of Asia.” It is quite understandable that the conditions in which these short-term trips with the Cossack detachment took place in completely unexplored areas did not make it possible to make comprehensive long-term observations. However, the results that were achieved by Semenov in his expeditions were the greatest contribu7

tion to world science. After returning from the expedition, Semenov wanted to begin scientific processing of the materials from his trip, intending to publish a full report about it in two volumes with drawings and maps. In addition, he proposed to the Geographical Society a plan for a new trip to the Tien Shan in 1860 or 1861. The results of this expedition, which included in its route (in its main version) two crossings of the least accessible ridges of the Tien Shan, were supposed to surpass, in their scientific significance, the results of the expedition of 1856-1857. Semyonov himself rightly pointed out in his memoirs: “The expedition project was set up by me as broadly as the later projects of the bold expeditions of HM Przhevalsky.” Before leaving for the expedition, Semenov expected to finish developing a report on his trip and publishing it. All these plans, however, remained unfulfilled, since the Council of the Geographical Society did not have funds at that time either for the proposed publication or for supporting a new expedition. “... Litke did not find it possible to equip the grandiose expedition I proposed, not only in 1859 and 1860, but generally in the near future,” recalls Semyonov. In this regard, Semyonov abandoned his original intentions. Official duties (work on the editorial commission for the reform of 1861) significantly distracted him in the future from the development of the collected materials. Only 50 years later, when compiling his memoirs, in 1908, he fully described all stages of his journey in the second volume of his memoirs, which for the first time in this edition, 90 years after the journey, are open to the reader. Until this publication, only articles published by Semyonov in various years covered some of the most important scientific results of his expeditions. In 1858, Semenov published two reports on individual stages of his journey. One of them was read by Semenov at a meeting of the Russian Geographical Society and then published in the form of an article in the Bulletin of the Russian Geographical Society. The article contains a detailed description of the expedition route from the Santash plateau to the Zaukinsky pass and to the Naryn River in 1857. In addition, it gives a brief description of the Dzungarian and Trans-Ili Alatau. Another article (more detailed) was published in ”Petermanns Mitteilungen”. The first part of it consists of 4 chapters containing a general overview of the countries visited (Chapter 1), characteristics of the Dzhungar Alatau (Chapter 2), Trans-Ili Alatau (Chapter 3) and the Tien Shan itself and the Issyk-Kul plateau (4 -i chapter); the second part is a reprint of the report read by Semenov at the meeting of the Geographical Society, with minor changes. In 1867, Semyonov published in the “Notes of the Russian Geographical Society” a description of his trip to the western tip of Issyk-Kul in 1856. This article also contains a statement of observations he made in the Trans-Ili Alatau in August 1857. At the end of the article, Semyonov gives a detailed geographical characteristics of the Trans-Ili Alatau. The latest of his published articles, based on materials from the trip, appeared in 1885 in “Picturesque Russia” under the title “Heavenly Ridge and the Trans-Ili region.” In addition to these articles, Semyonov used the materials of his observations in the appropriate places of the Geographical-Statistical Dictionary and additions to the third volume of ”Earth Studies of Asia” (dedicated in large part to the description of the Altai and Sayan mountain systems). He also dwells on some 8

of the results of his observations in the Tien Shan in the preface to the second volume of Geography of Asia. Moving on to Semyonov’s works dedicated to the Tien Shan, let us first note some characteristic features of him as a traveler, a collector of primary geographical material, which largely determined the features of his corresponding geographical works. In Semenov’s various works one can find a number of places in which he expresses his understanding of the tasks of a traveler-explorer of little-known countries: “The explorer of unknown countries, in a difficult struggle with obstacles and hardships, has to deal with determining latitudes and longitudes, plotting on a map a visual survey of the route traveled, trigonometric or barometric determination of the heights he encountered, observations of the temperature of air and water, the overstretch and fall of the rock layers he encountered, the selection of their samples, the collection of plants and animals he encountered, observations of the influence of the surrounding nature and climate on organic life, questioning of natives and observations over their way of life, morals, customs and the influence of local conditions on them, recording everything they saw and heard in short diaries.” This is what P.P. Semenov said in his speech about HM Przhevalsky (1886). Semyonov also spoke about the qualities that a traveler should have in the preface to the fourth volume of ”Earth Studies of Asia.” He defined the work of travelers (and local observers) in this preface as the initial production of all the basic data serving a complete geographical knowledge of the country. To produce such data, according to Semenov, “local observers and researchers require special training in one of the specialties included in the cycle of geographical sciences, or at least greater observation, as well as the ability and skill in collecting information on this subject, and from the traveler, moreover, courage, bravery, the ability to endure hardships, resourcefulness, etc.” Particularly interesting in the above comments are indications of the versatility of observations that a traveler of that era had to engage in. Such versatility was not characteristic of all outstanding travelers who were Semyonov’s contemporaries. About the three largest African travelers of the second half of the 19th century - Livingston, Stanley and Barth, Joseph D. Hooker (also a famous traveler) rightly wrote: “Livingston and Stanley were brave pioneers, but they only managed to map the paths they had traversed for study nature did nothing. After the well-deserved Barthes it was even necessary to send another traveler to plot his routes on the map.” Unlike the mentioned travelers, P.P. Semenov was a traveler of a different type. “Uniting in his person a geologist, a botanist and a zoologist,” he was an example of a comprehensively prepared scientifically, a researcher who was able not only to visit, but, in the apt expression of G. E. Grumm-Grzhimailo, “to conquer for science the most interesting in oro - and hydrographically part of the Central Tien Shan.” With all the diversity of his research, Semenov, as a traveler, was not just a geologist, botanist, entomologist, etc., but first of all a geographer. His geological and botanical studies, height measurements and determinations of the distribution of eternal snow were not isolated observations, but were united by a geographical approach and pursued the task of collecting material for the general geographical characteristics of the studied areas. In the above enumeration of the main geographical data, Semy9

onov does not dwell on the question of which of them are the most significant for the geographical characteristics of the area and which issues should be primarily focused on by the traveler. This issue, however, was of particular importance in his own expeditions of 1855-1857. due to the extremely short period of observation to which he was forced to limit himself. In this regard, his letter sent from Semipalatinsk to the Geographical Society after the end of the expedition, in which he highlights the most significant objects of his geographical research, is very valuable for characterizing Semenov as a traveler. “My main attention was paid to the study of mountain passes, since their height determines the average height of the ridges, and the cross-section of the geographical profile and structure of mountain ranges, not to mention their importance as routes of communication between neighboring countries. Finally, I paid no less attention to study of the general features of the orographic and geognostic structure of the country and the vertical and horizontal distribution of vegetation,” wrote Semyonov in this letter. Thus, in addition to the topographical basis of the geographical study of the area, Semyonov especially emphasizes “the study of the general features of the orographic and geognostic structure of the country” and the distribution of vegetation. Semyonov considered the study of vegetation to be a particularly important task for a geographer. In this regard, he shared the views put forward at the beginning of the 19th century. Humboldt. Already in his message “On the importance of botanical and geographical research in Russia,” made at the Geographical Society in 1850, Semenov developed in detail the idea of the importance of studying vegetation, the influence of vegetation cover “on the physiognomic characteristics of each country.” In the first geographical descriptions of Semyonov, vegetation did not occupy a particularly significant place. This is explained by the fact that when developing other people’s research, Semenov was faced with the scarcity of material available about vegetation. “It is impossible to draw general conclusions from these still incomplete facts; we must limit ourselves to only a cursory overview of the vegetation of the country,” he wrote in his “Description of New California...”. Even more meager material was available at that time about the vegetation of Manchuria and the Amur region, to which his subsequent physical and geographical descriptions were devoted. But on his journey through the Tien Shan, Semenov could pay special attention to the vegetation cover of the areas under study. A collection of up to 1,000 plant species was one of the results of his journey. Another, no less important result was systematic records of the nature of the vegetation of the areas lying on the route of the expedition. In addition to vegetation, the traveler’s primary attention was drawn to orography in its connection with the geological structure of the area. In this respect, Semyonov was significantly ahead of the geographical science of the time to which his expedition belonged. This merit of Semyonova is noted by Yu. M. Shokalsky: “In those days... the geographical study of the earth’s surface reigned, and it is completely clear why, first of all, mathematical geography, that is, the creation of a map of the area being studied, this indispensable basis for any geographical study... The geological structure of the surface of a given area and its connection with its geomorphological character were just beginning to be clarified in the works of A. Humboldt.” “There 10

is no doubt,” writes Shokalsky, “that it was Pyotr Petrovich’s geographic talent that suggested to him what was then unclear to many, even outstanding figures in the field of geography.” The routes of Semenov’s Tien Shan expeditions for the most part passed through areas where nature, almost untouched by human influence, retained its natural appearance. It is therefore quite understandable that, while listing in the letter we cited above the issues that were at the center of his attention, Semyonov does not name issues related to human geography and the influence of man on nature. However, whenever there was an opportunity for this, Semyonov observed with particular interest the economy and life of the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz - the inhabitants of the Tien Shan, trying not to miss the most insignificant fact. In his reports, he describes in detail his visits to Kyrgyz settlements, individual meetings with Kyrgyz people along the expedition route, etc. Attention to issues of human geography has been characteristic of Semyonov the traveler from the very beginning of his geographical activities. Recalling in his memoirs his first travels around Europe, Semyonov writes about how he climbed the peaks of Semigorye, “paying equal attention to their volcanic rocks (trachytes) and to the remains of medieval castles on their peaks.” Describing, further, a visit to the Vosges, he notes: “I was attracted there, as in the Harz, not only by geological goals, but also by the desire to get acquainted with the economic life of peasants in France.” Having later become the head of the Geographical Society and the organizer of the largest Russian geographical expeditions, Semyonov constantly emphasized the importance of research in these travels into the relationship between man and nature. He formulated this very clearly in the preface to Potanin’s book about his journey along the Tangut-Tibetan outskirts of China and Central Mongolia. Semyonov points out in this preface that the expeditions of the Geographical Society “were not limited to geodetic surveys and orographic determinations, which can only serve as a framework for the scientific study of the country. Being under the leadership of such people as HM Przhevalsky, they paid special attention to the study of the nature of the country, its vegetation cover , the interesting world of animals living on its surface, and finally, on the distribution over this surface and the relationship to the earth of its ruler, man, who has subjugated the forces of nature.” This general characteristic given by Semyonov to Russian expeditions to Central Asia retains its significance in relation to his own Asian travels. Noting the main characteristic features of Semenov as a traveler, we will point out another distinctive feature of the observations he made. A significant place in Semyonov’s descriptions of the routes he traveled is occupied by descriptions of individual landscapes presented in figurative, artistic language. Semenov’s desire to reproduce in his notes the characteristic features of the general appearance of the areas lying on the route of the expedition can be considered one of the significant features of him as a traveler. Semyonov attached no less importance to artistic sketches of landscapes for subsequent scientific development. We have already mentioned that he specially invited the artist Kosharov to participate in the expedition. Semyonov paid great attention to Kosharov’s works. “The artist P. M. Kosharov provided an invaluable service to my expedition,” he wrote in a letter to the Geographical Society and at the end of the same 11

letter he indicated: “much that is not conveyed in words, but only in drawings, would have been lost for me without Kosharov’s accompaniment.” . Semyonov himself did not make sketches, but his descriptions of types of terrain, including both the traveler’s immediate first impressions and the results of his subsequent geographical observations, combine scientific accuracy of the image with expressiveness, not much inferior to an artistic sketch of the landscape. Let us note in conclusion that mountainous countries especially attracted Semenov due to the variety of types of nature found in them. This is best evidenced by his letter to the Geographical Society, written by him after the end of the Tien Shan expedition. “Neither the monotonous Siberian lowland, from the Northern Ocean to the Irtysh and from the Urals to Altai, devoid of any relief and not representing in its immeasurable space any mountain uplifts or outcrops of hard rock, nor the region of the Siberian Kyrgyz, faithful to the same type, from the Irtysh to the Chu and from Ishim to Balkhash, rich only in low mountain elevations, far from reaching the limits of eternal snow, cannot attract the special attention of a geographer and geologist-traveler. Only high mountainous countries that extend beyond the borders can be particularly interesting and fully worthy of a long-distance and independent expedition eternal snow and representing the greatest variety of relief, geognostic structure, irrigation, climates, etc.” In the preface to the second volume of Geography of Asia, Semyonov highlighted some “of the most general results” of his journey. “These results relate,” he pointed out, “to three very important questions” for the geosciences of Asia, namely: a) the height of the snow line in the Heavenly Ridge, b) the existence of alpine glaciers in it, c) the existence of volcanic phenomena in it.” First Semyonov examines these questions in particular detail in response to the doubt expressed by Humboldt regarding the possibility of such a significant height of the snow line in the Tien Shan, which Semyonov determined during the expedition (from 3,300 to 3,400 meters). Pointing out the approximate nature of the results he obtained, since the determination of altitudes was made by the boiling point of water, Semyonov notes that Humboldt’s objections are not directed at the inaccuracy of the observation method (which he himself used during his American trip), but “belong to the field of comparative geography.” In his comments, Humboldt came to the conclusion that the results obtained by Semyonov were dubious, comparing the height of the Tien Shan snow line determined by Semyonov with the height of the snow line in the Pyrenees and Elbrus (approximately at the same parallels), as well as in Altai (approximately at the same parallels). the same meridians). In answering these objections, Semyonov, like Humboldt, uses the comparative method, applying it, however, much more correctly than was done by Humboldt in his critical remarks. Semenov also compares the height of the snow line in the Tien Shan, determined by him, with the height of the snow line in ridges lying 1) approximately on the same meridians and 2) approximately on the same parallels. Semyonov takes the corresponding figures from Humboldt’s own work “Central Asia”. Let us briefly summarize Semenov’s reasoning. On the same meridian with the Heavenly Ridge the snow lines are located: In Altai (Tigerets squirrels) at 51° N. w. 2,000 meters. On the northern slope of the Himalayan ridge at 32° N. w. 4,730 meters. The Heavenly Ridge ex12

tends in the part visited by the expedition between 41 and 42° N. sh., therefore, just halfway between Altai and Himalayan. Taking the average between the mentioned figures, we obtain the height of the snow line for the Heavenly Ridge at 3,370 meters. In the same parallel zone with the Sky Ridge, snow lines are at the following altitudes: In the Pyrenees (between 42=30’ - 43=N) 2,550 meters. On Elbrus and Kazbek in the Caucasus Range (43° N) 3,080 meters. On Ararat (under 39’ N latitude) 4,030 meters. In the Rocky mountains of North America (at 43° N) 3,550 meters. “Humboldt, in his explanations of my letter to Ritter, points exclusively to the Pyrenees and Elbrus. As for the former, they cannot be taken into account at all when determining the height of the snow line in the Heavenly Ridge, being in a humid coastal climate, where the snow line should be ”incomparably lower than in the continental climate of inner Asia. But the Caucasus represents a better subject for comparison, if used with due caution.” Semyonov points out that the height of the snow line on Elbrus and Kazbek lies at 3,080 meters at a latitude 1 1/2° more north than in the Tien Shan, and in a climate incomparably more humid. On Ararat, where the climate is much drier and the latitude is 2 1/2° more southerly, we find the height of the snow line to be 4,030 meters. If between Elbrus and Ararat there were mountains that, relative to the dryness of the surrounding atmosphere, were intermediate between Elbrus and Ararat, and in their astronomical position lying on the same parallel with the Heavenly Ridge, then the height of the snow line in these mountains would be determined at 3420 meters. Semyonov further explains in detail the reason for the significant height of the Tien Shan snow line, pointing out that this height depends on the characteristics of the geographical location and climate of the Heavenly Range. “The unusual dryness of the atmosphere of the Heavenly Range in comparison with the atmosphere of Altai and the Caucasus” is correctly indicated by Semyonov as the main reason for the difference in the height of the snow line in these mountain systems. Semenov also finds confirmation of the correctness of his determination of the height of the Tien Shan snow line in a few height measurements made by other observers in Dzungaria (trigonometric determinations by Fedorov in Tarbagatai and barometric observations by Schrenk in the Dzungarian Alatau). Semyonov’s polemic with Humboldt about the height of the snow line of the Tien Shan is based primarily on a comparison of the height of the snow line of various mountain systems around the globe. In this case, Semyonov gave an example of the application of the comparative method in geography, outstanding for his time, applying it in relation to the Tien Shan with greater perfection than was done in the critical remarks of Humboldt himself. In addition to determining the height of the snow line, Semenov especially highlighted the discovery of the glaciers of the Tien Shan and the absence of volcanoes and volcanic rocks in those parts of the Tien Shan that were visited by the expedition. With the discovery of the Tien Shan glaciers, Semenov confirmed the assumptions of Ritter and Humboldt, made on the basis of Chinese sources. With indications of the absence of volcanoes in the areas he explored and the considerations expressed on this occasion, Semenov, according to Mushketov, “laid the first fruitful doubt about the validity of the volcanic nature of the Tien Shan.” In 1842, Schrenk pointed 13

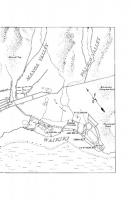

out that the Aral-Tyube island on Lake Ala-Kul is not a volcano, as Humboldt assumed. Schrenck’s research was confirmed in 1851 by Vlangali. Schrenk and Vlangali did not express, however, any general conjectural conclusions about the volcanism of the Tien Shan. The credit for the first indication of the doubtfulness of Tien Shan volcanism belongs to Semyonov. In the preface to the second volume of ”Earth Studies of Asia” Semyonov wrote. “The result of all my intensified searches was that I absolutely did not find any volcanoes, or true volcanic phenomena, or even volcanic rocks in the Sky Ridge.” Mount Kullok near Lake Issyk-Kul, as well as the group of Katu hills in the Ili Valley, turned out, according to Semyonov’s research, to represent “nothing volcanic.” With his characteristic caution in general conclusions, Semyonov wrote in the same preface that “the hints of Asians about phenomena that may seem volcanic should be accepted by scientific criticism with great caution, because many of them have already turned out to be unfounded. I will also note,” Semyonov pointed out, - that the impression made on me personally by Dzungaria and the Tien Shan arouses in me some doubts about the existence of volcanoes in this part of Asia, and, in any case, I, as the only eyewitness of the Heavenly Ridge, cannot accept the reality of these volcanoes as an axiom, not requiring no confirmation or evidence. This conviction is one of the important, although, of course, negative, results of my journey.” Thus, Semyonov for the first time rebelled against Humboldt’s opinion on the volcanism of the Tien Shan. Semyonov’s ideas about the orography of the parts of the Tien Shan he studied are visible from the schematic sketch of the orographic lines of the Dzungarian Alatau and Tien Shan attached to one of his articles. The division adopted by Semyonov and the terminology he established were significantly more accurate compared to earlier divisions. Semenov proposed the names of the “Dzhungar” and “Trans-Ili” Alatau for the corresponding ridges. Semenov was the first to draw attention to the connection of the Trans-Ili Alatau with other ridges of the Tien Shan, pointing out that “the Trans-Ili Alatau, with its distant extensions to the east and west, undoubtedly forms the advanced chain of the Tien Shan, from which it differs very little in its geognostic composition ”. Among the shortcomings of Semenov’s terminology is his exclusion from the geographical nomenclature of the Kyrgyz names Terskey-Alatau and Kungei-Alatau for the corresponding ridges. Subsequently, the name Trans-Ili Alatau remained behind the ridge designated by Semenov as the northern chain of the Trans-Ili Alatau. Behind the ridge, called by Semenov the southern chain of the Trans-Ili Alatau, its successful popular name later remained - Kungei-Alatau. A significant amendment made by later researchers to Semyonov’s orographic scheme was the establishment of an arched shape of the Tien Shan ridges, depicted by Semyonov himself with straight lines. Later studies supplemented this scheme with new ridges and showed the absence of the intersection of the two axes of uplift in the Dzhungar Alatau, as assumed by Semyonov. In addition to the above considerations about the snow line and volcanism of the Tien Shan, Semyonov’s main generalizations, based on the materials he collected, are contained in his descriptions of the Trans-Ili Alatau and Issyk-Kul. The description of the Trans-Ili Alatau is the most significant summary characteristic in articles 14

about the Tien Shan. The Trans-Ili Alatau was studied by Semenov in more detail than other parts of the Tien Shan system. In one of his articles, Semenov wrote: “Two trips in 1856 to both ends of Lake Issyk-Kul, despite the unfavorable conditions for scientific research in which they were carried out, had already sufficiently familiarized me with the orographic structure of the TransIli Alatau, but especially the information my knowledge about the orographic structure and geognostic structure of the Trans-Ili region expanded during quite long and numerous trips in this ridge during 1857, when I tried, especially in the eastern, safer part of the Trans-Ili Alatau, to cross both chains of it in all possible accessible ways mountain passes...” A description of the Trans-Ili Alatau was made by Semyonov in his articles of 1858 and 1867; with some changes caused mainly by the popularity of the publication, it was repeated in “Picturesque Russia” in 1885 and, finally, given in this edition. Let us indicate the main points of this description, using a detailed article published by Semenov back in 1867. Semenov describes the Trans-Ili Alatau from the confluence of the KarKara River with the Kegen River to the Buam Gorge, noting that the rise of the Trans-Ili Altau is not limited to the indicated limits. Initially, Semenov’s description outlines the general view of the Trans-Ili Alatau from the Ili River. “If you look at the Trans-Ili Alatau from the Ili River,” writes Semyonov, “it appears to rise as an extremely steep wall, without any foothills, and its wavy ridge does not represent deep cuts, but is only very elevated in the middle, where it completely crosses the snow line and gradually and symmetrically lowers on its two wings, which do not reach the snow line and do not carry eternal snow even on individual peaks. It is remarkable that from the Ili picket the shapes of the snow ridge in the middle of the Trans-Ili Alatau, with the transparent atmosphere of Central Asia, in the rays of the sun are for the most part completely clearly visible ”, while the insignificant buttresses and foothills of the ridge completely merge with each other, which further gives the ridge the appearance of a wall suddenly rising from a completely horizontal plane. As you approach the ridge, its foothills also become noticeable, however, completely insignificant in comparison with its colossality.” . In the following presentation, Semenov gives a brief summary of his observations on the orography and geological structure of the Trans-Ili Alatau. The orographic structure of the Trans-Ili Alatau is characterized, according to Semyonov, by clearly expressed symmetry. The mountain range consists of two main parallel ridges, which Semenov denotes by the names of the northern and southern chains. These chains are connected by a mountain knot, which seems to block off a deep longitudinal valley dividing both ridges into two longitudinal valleys of the Kebina and Chilika rivers, converging at their peaks and located in the same line. On both sides of the highest point of the ridge, the ridge of the Trans-Ili Alatau bears eternal snow, and then, to the east and west, it gradually decreases below the snow line. “It is also remarkable that the northern and southern chains slightly and gradually diverge or are separated from one another at their eastern and western extremities, and intermediate and parallel ridges with the mountain ranges move into the extremities of the longitudinal valley separating them and thus expanding...” The geological characteristics of the Trans-Ili Alatau include data on the petrographic compo15

sition of the rocks, their stratigraphic relationship and the tectonic structure of the ridge. The most detailed data are on the petrographic composition of the rocks. The greatest expert on the geology of Central Asia, I.V. Mushketov, fully included this description in the first volume of his “Turkestan”. Semenov notes in this description the difference between the longitudinal valleys of the Trans-Ili Alatau, composed predominantly of sedimentary rocks, and parallel chains, composed of predominantly crystalline rocks. Semenov’s ideas about the tectonics of the Trans-Ili Alatau are visible from the following quote: “The fall of the layers of sedimentary formations in the longitudinal valleys of Kebin and Chilik is synclinic, that is, obviously, these layers were raised by the simultaneous uplift of two parallel ridges. The intermediate ridge - Dalashik entirely consists of sedimentary formations, of which the layers form an anticlinical fold formed in the middle of the longitudinal valley and parallel to the crystalline ridges.” Semenov concludes his general review of the orography and geology of the Trans-Ili Alatau with the following general conclusion: “From all of the above it follows that the Trans-Ili Alatau is divided according to its relief into three components: 1) a northern chain with foothills; 2) longitudinal valleys with intermediate ridges and plateaus and 3) southern chain.” Semenov gives each of the components he identified a separate orographic characteristic. He characterizes the northern chain as “... a continuous ridge, in its middle part rising beyond the boundaries of the eternal snow, with very minor notches in this part, but descending in both wings and, finally, broken through in the eastern part by a transverse valley or the Chilika crack.. ”. This decrease is illustrated by the change in the height of the mountain passes, which decrease on both sides of the Talgar Peak - the highest point of the northern chain, located in its middle part. Semenov takes the average height of the ridge to be 2,450 meters, obtaining it by dividing the sum of the heights of the mountain passes he measured by their number. Of the morphological features of the ridge, Semenov further notes the transverse valleys along which mountain streams descend to the northern slope of the northern chain, and points out the features of the foothills. Semenov gives a similar characteristic for the southern chain, noting some of its orographic features. Of particular interest to us is the characteristics of the system of longitudinal valleys of the Trans-Ili Alatau. A significant place in this description is given to the question of the genesis of Chilik, located east of the turn between the lowered northern and southern chains of the Jalanash plateau. This plateau is composed of thick layers of loose conglomerate, which is underlain by mountain limestone. “The three Merke rivers flowing through the plateau, as well as Karkara and Kegen at their confluence, and Charyn, formed from this confluence, dug such deep channels for themselves that the valleys of these rivers cut into the main plateau to a depth of 200 meters and eroded the sediments to solid rock, which on the second Merka consists of mountain limestone with its fossils.” “This terribly rugged terrain,” points out Semyonov, “serves as the main obstacle on the best road from Verny to Issyk-Kul...”. Semenov explains the origin of the modern relief of the plateau as follows. Initially, in place of the plateau there was a deep intermountain basin: ”... at a time when this basin was still closed, it had to be filled with boulders and erosion brought 16

into it by numerous mountain streams, until the filling of the basin raised the level of the formed lake and did not force its waters to break through and merge to the northern side, where the Chilik and Charyn rivers are currently breaking out. Since then... the Merke rivers had to dig deep channels for themselves in the smooth plateau, the constituent parts of which presented too few obstacles to the eroding force mountain stream, which little by little deepened its bed in the loose rock and finally reached the solid mountain rocks. The connected rivers also broke through the stone ridge hidden under sediments at the bottom of the Charyn valley, which forms in a deep gorge, at the confluence of the Merke rivers Charyn, beautiful and picturesque rapids and a noisy current known as Ak-Togoy, that is, a white stream, because all the water of Charyn turns here into silvery foam and water dust.” Concluding the characterization of the orographic structure of the Trans-Ili Alatau by comparing the height of the Trans-Ili Alatau with the Alps, Pyrenees and the Caucasus, Semyonov moves on to a consideration of plant zones. In the Trans-Ili Alatau they distinguish the following zones: steppe, extending “at some distance from the foot of the Trans-Ili Alatau at an absolute altitude of 150 to 600 meters,” cultural or garden, which “extends not only at the very foot of the Trans-Ili Alatau, but also rises to its foothills and into its valleys to the lower limit of coniferous forests...” - that is, to an altitude of 1,400 meters on the northern and 1,500 meters on the southern slope of the Trans-Ili Alatau; the third zone, which can be called the coniferous forest zone, as well as subalpine, extends from 1,300 - 1,400 meters to the limits of forest vegetation, that is, 2,300 - 2,450 meters; the fourth zone, alpine, extends from the upper limit of forest vegetation, that is, 2,300 - 2,450 meters, to the snow line, that is, 3,200 - 3,300 meters. This zone is divided into the lower alpine, or zone of alpine shrubs, and the upper alpine, or zone of alpine grasses; “the fifth zone is the zone of eternal snow...”. Semenov’s characteristics of individual zones were well summarized in Lipsky’s famous work on the flora of Central Asia. Let us indicate Semenov’s main conclusions regarding the zones he identified, following partially Lipsky’s presentation. The vegetation of the steppe zone differs, according to Semyonov, in its originality in comparison with Europe. Not only the composition of the flora is original, numerous salt marsh plants, tamarix, astragalus Hedysorum, Alhage, Halimodendron, Ammodendron and others, but also the absence of crowding. “Nowhere do the plants form a continuous turf, but grow... at a fairly large distance from one another, so that the soil is mostly exposed in the gaps...”. In the steppe zone, two regions (tiers) can be distinguished. The first with saxaul and other characteristic Aral-Caspian plants, as well as local species. The second is characterized by wormwood (Artemisia spp.) and contains a greater admixture of European species than the first area. Concluding the characteristics of the steppe zone, Semyonov points to the characteristics of its climate and rivers and its economic importance. “The climate and soil of the steppe zone are characterized by unusual dryness. Rivers flowing in noisy mountain streams through three zones lying above the steppe, reaching this last one, quickly decrease in volume and soon stop flowing completely, forming a series of reaches or lakes with brackish water, and then partly absorbed into the soil, partly transformed into vapor 17

and thus flowing into the dry, hot summer atmosphere of the steppe strip. Few high-water rivers, such as the Ili, make an exception to the general rule, moistening their banks with their constant flow. Due to such physical properties ”It does not have any amenities for colonization in the steppe zone. But for the economic life of the native nomadic Kirghiz, the steppe zone is extremely important, since here they have the best wintering grounds and good pasture throughout the short and very little snow winter of this zone.” The cultural, or garden, zone occupies the foothills and foothills of Alatau to the lower limit of coniferous forests. Of the fruit trees in this zone, Semenov points out “wild apple, apricot or wild apricot, and in the western Tien Shan - pistachio tree and walnut.” Among other trees, Semenov names Populus laurifolia, Populus tremula, Betula davurica, Acer semenovi, Sorbus aucuparia, Prunus padus, Crataegus pirmatifida; in addition, a number of shrubs (more than 30 are listed). The flora of this zone contains more than 60% of Central European species. Between the Asian species there are elements of the Siberian-Altai (21 listed), Aral-Caspian (23) and Dzungarian floras proper (more than 30 listed). The cultural zone is distinguished by great conveniences for arable farming and gardening and extraordinary fertility, but only under one condition, namely the possibility of artificial irrigation (irrigation). ” Turning to the question of the significance of the zone for Russian colonization, Semenov points out the difference in those foothills within its are located below the snowy or high parts of Alatau and are distinguished by fertility due to the abundance of water brought by mountain streams from these zones, and dry foothills located where the mountain ridge decreases. The coniferous forest zone is characterized by the predominance of spruce Picea schrenkiana; deciduous trees include poplar, aspen, birch, rowan and others. Among the shrubs listed by Semenov (24), 7 species of Lonicera were named. As in the cultural zone, in the coniferous forest zone there are more than 60% of European species; in the upper parts of the zone there are alpine and polar types (17 listed); of the other 40% Asian, more than half belong to plants of the Siberian north, Altai-Sayan, and partly polar (38 are listed); in addition, Caucasian (10 indicated), Himalayan (5) and local Tien Shan (26). The economic importance of this zone for Russian colonization is determined by its forests, which provide building material and fuel. In some places the zone acquires a subalpine character: forests are replaced by subalpine meadows interspersed with rocks. These meadows are important for the Kyrgyz summer migrations. The alpine zone is divided into the lower alpine, or alpine shrub zone, and the upper alpine, or alpine grass zone. Alpine shrubs belong to a small number of species (12 are listed). The absence of Rhododendron is remarkable, due to the dry climate. There are more than 25% of European plants in this zone, mainly of the alpine-polar type (23 listed), a few plants belong to the Central European ones (10), most are characteristic of the alpine zone, Altai-Sayan flora and polar Siberia (about 50 listed), several Himalayan ( 4); a number of plants belong to the Tien Shan flora proper (30). The zone is rich in excellent meadows and pastures and is therefore of great economic importance for the summer migrations of the Kyrgyz. “The zone of eternal snow also has a very large, although only indirect economic significance, since only in those foothills 18

of the ridge above which there is a zone of eternal snow is the cultural zone rich, irrigated and quite capable of irrigation, and therefore, for arable farming, gardening and colonization ”. This is how Semenov ends his description of the last zone he identified, Alatau. Much more concise, due to the smaller amount of data, is the characteristics of the basin of Lake Issyk-Kul. Before turning to Semenov’s description of the Issyk-Kul basin, we point out that one of the main results of Semenov’s trip to the western end of the lake can be considered the establishment of the existing relationships between Lake Issyk-Kul and the Chu River. Until Semenov’s expedition, the dominant view among geographers was that the Chu River flows from Issyk-Kul. During his trip, Semenov first established that the Chu is a continuation of the Kochkura River (according to Semenov, the Kochkar or Koshkar River. Ed.), flowing from the Tien Shan mountain valley west of Issyk-Kul. Semenov’s observations established that the Chu, before reaching Issyk-Kul, turns sharply in the opposite direction from the lake, crashing into the mountains rising on the western side of Issyk-Kul and, finally, bursts into the Buam Gorge. Having reached the swampy area located at the very turn of the Chu River, Semenov discovered a small river connecting the Chu with Issyk-Kul. “...This river, due to its shallowness and insignificance, is called Kutemaldy,” Semyonov later wrote in an article about the trip, “that’s what, at least at the present time, the hydrographic connection of the Chu River with Lake Issyk-Kul, which was previously geographers (Ritter and Humboldt) took it as the source of the Chu River.” In characterizing the Issyk-Kul basin, Semenov used the results of his observations to resolve the question of the origin of the existing relationship between the Chu River and Issyk-Kul and the genesis of the Buam Gorge. Let us dwell on certain aspects of the description of the Issyk-Kul valley. Just as in the description of the Trans-Ili Alatau, we find here the initial description of the external appearance of the area, as it appears when viewed directly by the observer. In the subsequent presentation, as well as in the description of the Trans-Ili Alatau, where available data allows, Semyonov highlights the issues of the genesis of modern relief and hydrographic network. Thus, noting that the Issyk-Kul valley is surrounded on all sides by terraces composed of conglomerates, which rise significantly above the modern level of the lake, he draws the following conclusions: “Since these conglomerates are in an inappropriate (discordant) bedding with the Paleozoic rocks of the Tien- Shan and Alatau, and since the same conglomerates form the bottom of the lake, where I happened to observe it, I believe that these conglomerates are the sediments of the lake itself. In this case, the distribution of these conglomerates throughout the entire lake basin to a significant height above the current level of the lake sufficiently indicates that in former times the lake occupied an incomparably more extensive surface.This opinion can be confirmed by the very formation of the Buam Gorge, the origin of which cannot be attributed to the breakthrough of too little significant for that Koshkar, but can only be explained by the breakthrough of the waters of the whole the Issyk-Kul basin, the level of which should have quickly decreased after such a breakthrough. Thus, for a long time after this breakthrough, the Chu River could have been the drainage of the Issyk-Kul, until a decrease in its level finally stopped this flow, after which 19

the former tributary of the Issyk-Kul, and then the Chu Koshkar River, became its source . This latest decline of Issyk-Kul can only be attributed to the fact that the tributaries of the lake, becoming scarce in water due to the rise of the snow line in a drier and drier continental climate, do not compensate for the amount of water lost by evaporation.” Semyonov devotes the final part of the description of the Issyk-Kul basin, as well as the final parts of the characteristics of the zones of the Trans-Ili Alatau, to the question of the opportunities provided by the area for farming. This is, in general terms, the content of the two most significant geographical characteristics of Semenov in his articles on the Tien Shan. The geological, botanical and other information contained in them was repeatedly used by later researchers. These characteristics, however, have great geographical value not only as a source of the first scientific information about the Tien Shan, but also as outstanding examples of primary data development for their time. Let us dwell on some of Semenov’s particular conclusions, which were of particular importance for subsequent researchers of the Tien Shan, and the assessment of his development of geological and botanical data by the latest researchers. Among the most important conclusions of Semenov, based on geological materials, are his conclusions about the genesis of the conglomerates of the Issyk-Kul basin and the Jalanash plateau, the origin of the Buam Gorge, as well as his explanation of the relationship between the Chu River and Issyk-Kul. The conglomerates described by Semenov for the Issyk-Kul basin and the Jalanash plateau are widespread in the longitudinal valleys of the Tien Shan. Their widespread distribution was already established in the works of researchers who visited the Tien Shan in the coming decades after Semenov’s expedition. Semyonov’s assumption that the conglomerates of the Issyk-Kul basin ”are the essence of the sediment of the lake itself” turned out to be as fruitful as his explanation of the origin of the Jalanash conglomerates. Using the example of Jalanash, Semenov gave an explanation for the formation of thick strata of conglomerates, suitable for many longitudinal valleys of the Tien Shan. As we saw above, according to Semenov, there was a lake in an initially closed mountain basin. As a result of the breakthrough of the lake’s waters and its descent, a smooth plateau was formed, which was later cut by deep river beds. Two decades later, I. V. Mushketov, in a report on his trip in 1875, wrote about the longitudinal valleys of the Tien Shan: “Almost everywhere, new lake sediments are observed in them, expressed as horizontal conglomerates and sandstones, which is why one can think that these valleys once formed large reservoirs or mountain lakes. Subsequently, these reservoirs dried up for the reason that the water accumulated in them constantly eroded the neighboring mountains, and finally made its way through one of the neighboring ridges, which was less resistant than others to its destructive force. The water, having found a way out , constantly deepened the newly formed channel and gradually flowed down this channel, draining the reservoir.” Issyk-Kul, according to Mushketov, as well as the existing lakes Son-kul, Sairam-nor, Chatyr-kul and others, “in many ways resemble these dried-up reservoirs; at Son-kul you can see with your own eyes how every year the From the lake, the only river Kodzherty-su is constantly deepening its bed, which, perhaps, will subsequently 20

spill out into the entire Son-Kul lake, as many others like it have already spilled out.” Similar thoughts about the ancient lakes of the Tien Shan were expressed by many later researchers. Krasnov gave numerous examples confirming the instructions of Semenov and Mushketov. Semenov associated the formation of thick strata of Tien Shan conglomerates (including lake conglomerates) with the activity of mountain streams. The Jalanash basin, according to him, was filled up as a result of this activity with sediments of sand, clay and boulders. This explanation was also repeatedly confirmed by later researchers of the 19th century. and has not lost its meaning today. “P.P. Semenov was the first to give, confirmed after I.V. Mushketov, an explanation of the origin of these formations. He considers them to be the results of the deposition of pebbles and other products of destruction brought by mountain streams and deposited in the valleys and foothills,” Krasnov wrote in his work about the Tien Shan. Agreeing with this idea of Semyonov, Krasnov complements it with the consideration that in the era of the formation of these sediment layers, the amount of snow that supplied these waters, rolling boulders, was greater, and the snow line descended. “In the Issyk-Kul valley, as indeed elsewhere in the Tien Shan, the denudation activity of mountain streams is very important,” L. S. Berg later wrote in his famous work on Issyk-Kul. Pointing out that the shores of Issyk-Kul and Chu “in some places, over a considerable distance, are covered with a mass of large pebbles carried out from the mountains in the spring by mountain streams and streams,” L. S. Berg, like previous researchers of the Tien Shan, refers to the classic example of P. P’s explanation Semenov formed the Jalanash conglomerate. The most significant addition to Semenov’s explanation of the formation of conglomerates in the part of the Tien Shan he studied can be considered the indications of later researchers on the role of the destructive work of insolation and wind in the formation of Quaternary deposits of the Tien Shan. There are also indications of the glacial origin of some conglomerates (the work of L. S. Berg). The development of geological data on the conglomerates of the Issyk-Kul basin was used by Semenov for geographical conclusions about the development of the Chu river system and the origin of the Buam Gorge. The resolution of the issue of the relationship of the Chu River to Issyk-Kul was one of the important results of Semenov’s expedition. The relationships between the Kochkura, Chu and Kutemaldy rivers established by Semenov’s observations were explained differently by different researchers. Venyukov and Severtsov, who visited IssykKul after Semenov, considered Kutemaldy to be Kochkur’s sleeve. Golubev and Kostenko assumed that Kutemaldy is an aryk. I.V. Mushketov joined the views of Semyonov, who mistook Kutemaldy for the former source of the river. Chu. A critical summary of these and later hypotheses was made by L. S. Berg in his work on Issyk-Kul. A comparison of various hypotheses of later researchers with the views first expressed by P. P. Semenov on the origin of the relationships between the Chu River and Issyk-Kul that he established testifies to Semenov’s great scientific insight. An assessment of these views “from the point of view of the modern theory of the evolution of river arteries” was recently given by Ya. S. Edelshtein, who pointed out that a possible addition to Semyonov’s hypothesis is the assumption of the river interception of Kochkur by the Chu River, 21

as a result of which the Kochkur River, which previously flowed into the lake Issyk-Kul was intercepted by the top of the Chu River and began to give its waters to the Syr Darya basin. “...We must not forget,” adds Edelyntein, “that these ideas, so familiar to us now, about the development of neighboring river systems did not yet exist in science at that time.” The question of the origin of the Buam Gorge, closely related to the problem of the evolution of the Chu river system, was also resolved by later researchers in the spirit of the views first expressed by Semyonov. “... The Buam Gorge is a typical breakthrough valley...” points out the largest researcher of Issyk-Kul, L. S. Berg. According to Berg, “in the era of a more significant spread of glaciers in the Tien Shan, Lake Issyk-Kul stood much higher than now. At that time, the Chu River flowed into the lake, overflowed it and gave it a source through the ridge in the place where the Buam Gorge is now located. Over time, the Chu, gradually deepening its channel, dug the Buam Gorge; at the same time, carrying away more and more waters of Issyk-Kul due to the deepening of the source, the Chu significantly lowered the level of the lake, and finally, due to still unknown reasons, it completely stopped flowing into it.” Mushketov and others also joined Semenov’s view of the Buam Gorge as a valley dug by the flowing waters of Issyk-Kul. We have given examples of Semenov’s development of geological data about the Tien Shan. A general assessment of this development can be found in I.V. Mushketov, Friedrichsen, K.I. Bogdanovich, Merzbacher, V.A. Obruchev, Ya.S. Edelshtein and others. Most later geological researchers note the role of P.P. Semenov as the first scientific explorer of Central Asia and indicate that his discoveries laid the foundation for the subsequent study of the Tien Shan system. A similar assessment can be found both in the works of Russian geologists and in Western European literature. For example, Friedrichsen at the end of the 19th century. wrote that Semyonov, thanks to his geological knowledge and insight, already in 1857 laid the foundation for our modern knowledge of the Tien Shan and created the foundation on which further solid construction became possible. No less significant in his works on the Tien Shan were Semyonov’s phytogeographical conclusions, based on the botanical materials he collected. The botanical research of P. P. Semenov received well-deserved appreciation in the works of A. N. Krasnov, V. I. Lipsky, V. L. Komarov and others. The main one of Semyonov’s phytogeographical generalizations was his proposed scheme of zones of the Trans-Ili Alatau. In his major work on the flora of Central Asia, V.I. Lipsky pointed out that Semyonov gave “the first botanical and geographical picture of Central Asia, which can still serve as a model...” (Written in 1902, almost half a century after Semyonov’s travel .) This assessment is undoubtedly fair. Before Semenov, the most significant conclusions about the vertical zonation of Central Asia were made by A. I. Shrenk as a result of his famous expedition of 1840-1842. But A. Schrenk died without having time to fully process the materials he collected. Schrenk’s report on his first trip contained interesting data on changes in the vegetation of the Dzhungar Alatau depending on altitude. However, this report did not create a developed scheme of vertical vegetation zones in relation to the Dzhungar Alatau. The patterns of vertical distribution of vegetation in the mountainous regions of Central Asia were first established by Semenov in 22