Therapist Toolkit

Therapist Toolkit $245.00

128 87 60MB

English Pages [805] Year 2020

Licensure Agreement

Part 1: Assessment Tools

Table of Contents for Part 1

Assessment Tests without Answer Sheets

Pre-Therapy Testing

Depression Checklist

Anxiety Inventory

Relationship Satisfaction Scale

Assessment Tests with Answer Sheets

Depression Check list

Anxiety Inventory

Relationship Satisfaction Scale

Empathy Scale

Patient's Therapy Session Evaluation

Brief Assessment Tests For Indiviuals with Disabilities

Depression Checklist - brief version

Anxiety Inventory - brief version

Relationship Satisfaction Scale

Empathy Scale

Assessing Self-Defeating Attitudes and Beliefs

The Initial Evaluation

The Final Evaluation

DSM-IV Diagnosis

Table of Contents for DSM-IV Survey

Part 2: Treatment Tools

Table of Contents for Part 2

Overview of Part 2

How to Use the Forms & Charts for Treating Mood Problems

How to Use the Forms & Charts for Treating Relationship Problems

Summary of Cognitive Therapy Interventions

THE Forms & Charts for Treating Mood Problems

The Daily Mood Log / Triple Column

Self-Defeating Beliefs

Your Thoughts and Your Feelings

Unhappy Stick Figure

Five Steps for Feeling Good

How to Use the CBA

How to Use the Pleasure Predicting Sheet

Daily Activity Schedule

Anti-Procastination Sheet

Decision Making Form

THE Forms & Charts for Treating Relationship Problems

Relationship CBA

Revise Your Communication / Relationship Journal

Memos to Orient New Patients to Therapy

Concept of Self-Help

Make Therapy Rewarding and Successful

Specialized Memos

The Anti-Hopelessness Memo

Part 3: 1997 Upgrade

Table of Contents for Part 3

In a Hurry? Read This!

Description, Scoring and Psychometric Properties

Depression

Anxiety

Anger

Relationship Satisfaction Test

Empathy & Patient Satisfaction Scales

Full Scales

New, Experimental Scales (1997)

Answer Sheets for New Scales (1997)

Chart Records

References

Appendix

Part 4: 2016 Upgrade

Assessment Tests for Adults & Teens

Assessment Tests for Children & Adolescents

Assessment Tests for Medical Settings

Cognitive Behavior Therapy Tools

Interpersonal Therapy Tools

Memos & Administrative Tools

Motivational Tools

Other - Order forms, etc.

Reading Lists

Tools for Supervision and Teaching

Tools in Foreign Languages

French

Russian

Spanish

Two-Sided Color Cards

Common Self-Defeating Beliefs

Recovery Circle

50 Ways to Untwist Your Thinking

Perfectionism CBA

Love Addiction CBA

Why People Resist Change

Blame CBA

EAR

Feeling Word Chart

12 GOOD Reasons NOT to

Bad Communication Checklist

EAR Checklist

Depression Recovery Map

Anxiety Recovery Map

Anger Recovery Map

Habit / Addiction Recovery Map

5 Steps in Agenda Setting

Writings & Excerpts

Acceptance and Commitment In CBT

Selecting the Most EffectiveTechniques for Your Patients

Interpersonal Techniques

Suicide Assessment and Prevention

Suicide Assessment Interview

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- David Burns

- Commentary

- decrypted from 3B542D5E0676F14698E8A2D8DCBD5503 source file

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

Licensure Agreement This license gives you permission to print the materials from this PDF for use in your psychotherapy practice. The materials are intended for use only by qualified mental health professionals. This license does NOT give you the right to reproduce these materials for other purposes including research, books, pamphlets, articles, video or audio tapes, handouts or slides for lectures or workshops. Electronic reproduction is not permitted. You will need the separate Electronic Tool Package & License. Please visit www.FeelingGood.com to purchase. Reproduction on the Internet is not permitted. Permission to use or reproduce these materials for any other purpose must be obtained in writing from David D. Burns, M. D.

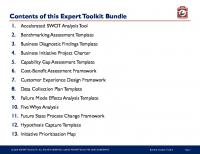

What is Included in this Therapist’s Toolkit 2020 Edition! The materials from the 400+ page 1995 Original Edition plus the upgrades from following years up until 2018. There are bookmarks for easy navigation. Look for the bookmark icon in your PDF reader app to open the navigation pane.

1995 Therapist's Toolkit Part 1 - 145 pages Assessment tools include tests for depression, anxiety, relationship satisfaction, and therapeutic empathy, along with answer sheets and scoring keys; Self-Defeating Beliefs Scale; Clinician's History form (brief and complete versions); Speedy Screening System for DSM-IV (Axes I and II); Patient's Evaluation of Therapy; and Termination Summary.

Part 2 - 129 pages Individual therapy tools include the Summary of Cognitive Interventions, Daily Mood Log with instructions, Checklist of Cognitive Distortions, Troubleshooting Guide, How to Untwist Your Thinking, Cost-Benefit Analysis (three types with instruction sheet), Daily Activity Schedule, Anti-Procrastination Sheet, and the Decision Making Form (with instruction sheet). Also included are The Concept of Self-Help Memo, How to Make Therapy Rewarding and Successful, The Anti-Hopelessness Memo, progress notes, medication records, Clinician's Data Sheet, and more. Interpersonal therapy tools include the Relationship Cost-Benefit Analysis (with instruction sheet), Revise Your Communication Style (with instructions), Good vs. Bad Communication, Bad Communication Checklist, Five Secrets of Effective Communication, Feeling Words Chart, 12 Barriers to Self-Expression, and 12 Barriers to Listening.

Part 3: 1997 Upgrade - 150 pages Includes new and improved assessment tools for: Anxiety Disorders: Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder, Agoraphobia, OCD, Social Phobia, PTSD Depression: Burns Depression Checklist (25-item and 5-item versions, plus assessment of suicidal urges) Relationship Problems: Relationship Satisfaction Scale (5-item version), Anger Scale, (Violent Urges Scale) Therapy Session Evaluation: Empathy Scale, Helpfulness of Session (5-item and fulllength versions) Positive Emotions: Happiness, Self-Esteem, Intimacy, Productivity, Playfulness, Freedom from Fear, Hope, Spirituality (eight 5-item scales) Self-Help Report: For tracking patients' self-help activities and psychotherapy homework Convenient Chart Records: Makes it easy to record scores and review changes over time And morel As noted, most scales come with a choice of time perspectives ("indicate how have you been feeling over the past week" vs. "indicate how you are feeling at this moment"). Many scales are available in two lengths. The full-length versions have superb reliabilities (typically 95% or better) and are suitable for comprehensive assessment. The brief, 5-item scales also have outstanding reliabilities (typically 90% or better) and are suitable for tracking symptoms on a session-by-session basis. Many scales are also formatted in large typeface to help individuals with impaired vision or reading difficulties.

Part 4: 2016 Upgrade – 376 pages The 2016 Upgrade contains 2005, 2007, 2010, and many other upgrades! It contains wonderful instruments you can use in your clinical work, including the new and improved Daily Mood Log, the new and improved Brief Mood Survey with individual and group scales, scales in Spanish, the Pain Scale, instruments for children, scales to use in medical settings, a therapy supervision scale, the 50 Ways to Untwist Your Thinking, and much more.

Plus 2016 Upgrade

2016 Upgrade Assessment Tests for Adults and Teens Assessment Tests for Children and Adolescents Assessment Tests for Medical Settings Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) Tools Interpersonal Therapy (IPT) Tools Memos and Administrative Tools Motivational Tools Other – Order Forms, reading list Reading Lists Tools for Supervision and Teaching Tools in Foreign Languages Two-Sided Color Cards Writings and Excerpts from Dr. Burns Therapy Ebook

Licensure Agreement By David D. Burns, M.D.

Purchase of the Therapist’s Toolkit and / or the EASY Diagnostic System provides you with a license to photocopy the materials for use in your clinical practice. The license does NOT give you the right to reproduce these materials for other purposes including research, books, pamphlets, articles, video or audio tapes, handouts or slides for lectures or workshops. Electronic reproduction is not permitted. Reproduction or illustration on the Internet is not permitted. The Therapist’s Toolkit and EASY Diagnostic System are intended for use only by qualified mental health professionals. The license is limited to the clinician who purchased the Therapist’s Toolkit and does not extend to additional clinicians. Licenses cannot be sold or transferred to other individuals. However, licenses for additional therapists who practice together at the same location can be purchased for a modest fee. This gives additional therapists the right to use and photocopy the treatment and assessment tools in the Therapist’s Toolkit and / or the EASY Diagnostic System. Permission to use or reproduce these materials for any other purpose must be obtained in writing from David D. Burns, M.D.

Assessment Tests for Adults and Teens

1. Initial Diagnostic Assessment. Did you complete a comprehensive Axis I and Axis II diagnostic survey at the initial evaluation? 2. Clinical History. Did you flush out hidden agendas or conflicts of interest that could sabotage the treatment? Did you assess the patient's motivation and make him or her accountable? Did you ask about disability evaluations or legal entanglements, such as lawsuits, that could bias this patient's response to the treatment? Have you conceptualized the problem properly? 3. Psychotherapy Homework. Did the patient fill out the "Concept of SelfHelp Memo," along with the Self-Help Contract? Is the patient willing to do psychotherapy homework consistently between sessions? 4. Session-by-Session Testing. Do you track changes in symptoms at every therapy session, using instruments that accurately measure depression, suicidal urges, anxiety, anger, and relationship satisfaction? 5. Therapeutic Empathy. Do you have a vibrant, trusting therapeutic alliance? Does the patient feel accepted and cared about? Does the patient rate you on the Therapeutic Empathy scale after every session to indicate how warm, respectful and understanding you were? Are you getting scores of 20? 6. Therapeutic Helpfulness. Does the patient rate you on the Therapeutic Helpfulness scale after every therapy session? Does the patient feel that your interventions are relevant and helpful? 7. Agenda Setting. Invitation: Have you asked if the patient wants something more than listening and support? Specificity: Have you pinpointed one specific moment the patient wants help with? Conceptualization: Have you conceptualized the problem as an individual mood problem, relationship problem, or habit / addiction? Motivation: Have you explored Outcome and Process Resistance? Is the patient ready to change and willing to work hard, if you agree to help him or her with this problem? 8. Methods. Are you using a variety of techniques that specifically target this patient's problem? If it's an individual mood problem, are you using the Daily Mood Log and Recovery Circle, and "failing as fast as you can"? If it's a relationship problem, are you using interpersonal techniques, such as the Revise Your Communication Style form? Total

* Copyright © 2003 by David D. Burns, M.D.

2—Yes

1—Unsure

0—No

Therapist's Report Card* Instructions. Therapeutic failure usually results from the therapist errors listed below. Think of a patient you're stuck with and use checks () to indicate how well you're doing in each category.

Scoring Key: Therapist's Report Card Score

Grade

Interpretation

16

A+

Awesome! Few therapists do this well.

14 – 15

A

Very good. There's only a little bit of room for improvement.

11 – 13

B

Decent, but there are some problem areas to work on.

8 – 10

C

Not so good. There are lots of areas that need work.

4–7

D

Hmmm. What a can I say? Well, the good news is that the reasons for the therapeutic failure should be obvious, and there's lots of room for improvement!

0–3

F

Heck, we've all got to start somewhere. Furthermore, you've done an honest job of pinpointing the reasons for the therapeutic failure. There's nowhere to go but up!

Your Name:

Date:

Total

Total

Total

Total

Total

Total

Total

Total

4—Extremely

3—A lot

2—Moderately

1—Somewhat

0—Not at all

After Session 4—Extremely

3—A lot

How depressed do you feel right now? 1. Sad or down in the dumps 2. Discouraged or hopeless 3. Low self-esteem, inferiority, or worthlessness 4. Loss of motivation to do things 5. Loss of pleasure or satisfaction in life

2—Moderately

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how you're feeling right now. Please answer all the items.

1—Somewhat

Brief Mood Survey*

0—Not at all

Before Session

How suicidal do you feel right now? 1. Do you have any suicidal thoughts? 2. Would you like to end your life? How anxious do you feel right now? 1. Anxious 2. Frightened 3. Worrying about things 4. Tense or on edge 5. Nervous How angry do you feel right now? 1. Frustrated 2. Annoyed 3. Resentful 4. Angry 5. Irritated

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10.

Total

4—Extremely

3—A lot

2—Moderately

1—Somewhat

0—Not at all

4—Extremely

3—A lot

Positive Feelings: How do you feel right now? I feel worthwhile. I feel good about myself. I feel close to people. I feel I am accomplishing something. I feel motivated to do things. I feel calm and relaxed. I feel a spiritual connection to others. I feel hopeful. I feel encouraged and optimistic. My life is satisfying.

2—Moderately

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how you're feeling right now. Please answer all the items.

0—Not at all

Positive Feelings Survey*

1—Somewhat

Your answers on the following items will tend to be the opposite from your answers on the negative mood items above.

Total

* Copyright 1997 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2010.

Please fill this out BEFORE and AFTER the session. Thank you!

Page 1

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Therapeutic Empathy My therapist seemed warm, supportive, and concerned. My therapist seemed trustworthy. My therapist treated me with respect. My therapist did a good job of listening. My therapist understood how I felt inside. Total

6. 7. 8. 9. 10.

Helpfulness of the Session I was able to express my feelings during the session. I talked about the problems that are bothering me. The techniques we used were helpful. The approach my therapist used made sense. I learned some new ways to deal with my problems. Total

Satisfaction with Today's Session 11. I believe the session was helpful to me. 12. Overall, I was satisfied with today's session. Total Your Commitment 13. I plan to do therapy homework before the next session. 14. I intend to use what I learned in today's session. Total Negative Feelings During the Session 15. At times, my therapist didn't seem to understand how I felt. 16. At times, I felt uncomfortable during the session. 17. I didn't always agree with my therapist. Total Difficulties with the Questions 18. It was hard to answer some of these questions honestly. 19. Sometimes my answers didn't show how I really felt inside. 20. It would be too upsetting for me to criticize my therapist. Total What did you like the least about the session?

What did you like the best about the session?

*

Copyright © 2001 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2004.

4–Completely true

3–Very true

Please answer all the items.

2–Moderately true

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how you felt about your most recent therapy session.

1–Somewhat true

Evaluation of Therapy Session*

0–Not at all true

Please fill this out AFTER the session. Thank you!

Your Name:

Date:

Please complete the following surveys BEFORE and AFTER the session. Then complete the survey on the back AFTER the session. Thank you!

Total

Total

1. Communication and openness 2. Resolving conflicts 3. Degree of affection and caring 4. Intimacy and closeness 5. Overall satisfaction Total

* Copyright 1997 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised 2010, 2011.

Total

4—Extremely 6—Very Satisfied

1—Moderately Dissatisfied

0—Very Dissatisfied

After Session

6—Very Satisfied

5—Moderately Satisfied

4—Somewhat Satisfied

3—Neutral

2—Somewhat Dissatisfied

Use checks () to indicate how you feel about this relationship. Please answer all 5 items.

1—Moderately Dissatisfied

How angry do you feel right now? 1. Frustrated 2. Annoyed 3. Resentful 4. Angry 5. Irritated

Put the name of an important relationship in your life:

0—Very Dissatisfied

Relationship Satisfaction * Total

3—A lot

Total

Before Session

Total

2—Moderately

1—Somewhat

0—Not at all

4—Extremely

3—A lot

2—Moderately

1—Somewhat

0—Not at all

4—Extremely

Total

How anxious do you feel right now? 1. Anxious 2. Frightened 3. Worrying about things 4. Tense or on edge 5. Nervous

5—Moderately Satisfied

Total

I feel worthwhile. I feel good about myself. I feel close to people. I feel productive. I feel motivated to do things. I feel calm and relaxed. I feel a connection to others. I feel hopeful. I feel encouraged and optimistic. My life is satisfying.

4—Somewhat Satisfied

Total

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10.

3—Neutral

Total

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how you're feeling right now. Please answer all the items.

After Session

2—Somewhat Dissatisfied

Total How suicidal do you feel right now? 1. Do you have any suicidal thoughts? 2. Would you like to end your life?

Before Session Positive Feelings Survey*

3—A lot

2—Moderately

1—Somewhat

0—Not at all

After Session 4—Extremely

3—A lot

How depressed do you feel right now? 1. Sad or down in the dumps 2. Discouraged or hopeless 3. Low self-esteem, inferiority, worthlessness 4. Loss of motivation to do things 5. Loss of pleasure or satisfaction in life

1—Somewhat

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how you're feeling right now. Please answer all the items.

0—Not at all

Brief Mood Survey*

2—Moderately

Before Session

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Therapeutic Empathy My therapist seemed warm, supportive, and concerned. My therapist seemed trustworthy. My therapist treated me with respect. My therapist did a good job of listening. My therapist understood how I felt inside. Total

6. 7. 8. 9. 10.

Helpfulness of the Session I was able to express my feelings during the session. I talked about the problems that are bothering me. The techniques we used were helpful. The approach my therapist used made sense. I learned some new ways to deal with my problems. Total

Satisfaction with Today's Session 11. I believe the session was helpful to me. 12. Overall, I was satisfied with today's session. Total Your Commitment 13. I plan to do therapy homework before the next session. 14. I intend to use what I learned in today's session. Total Negative Feelings During the Session 15. At times, my therapist didn't seem to understand how I felt. 16. At times, I felt uncomfortable during the session. 17. I didn't always agree with my therapist. Total Difficulties with the Questions 18. It was hard to answer some of these questions honestly. 19. Sometimes my answers didn't show how I really felt inside. 20. It would be too upsetting for me to criticize my therapist. Total What did you like the least about the session?

What did you like the best about the session?

*

Copyright © 2001 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2004.

4–Completely true

3–Very true

Please answer all the items.

2–Moderately true

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how you felt about your most recent therapy session.

1–Somewhat true

Evaluation of Therapy Session*

0–Not at all true

Please fill this out AFTER the session. Thank you!

Depression 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

4—Extremely

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how depressed, anxious or angry you've been feeling over the past week, including today. Please answer all the items.

3—A lot

0—Not at all

Brief Mood Survey*

2—Moderately

Date: 1—Somewhat

Name:

Sad or down in the dumps Discouraged or hopeless Low self-esteem, inferiority, or worthlessness Loss of motivation to do things Loss of pleasure or satisfaction in life Total Items 1 to 5 Suicidal Urges

1. Have you had any suicidal thoughts? 2. Would you like to end your life? Total Items 1 to 2 Anxiety 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Anxious Frightened Worrying about things Tense or on edge Nervous Total Items 1 to 5 Anger

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Frustrated Annoyed Resentful Angry Irritated Total Items 1 to 5

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Communication and openness Resolving conflicts and arguments Degree of affection and caring Intimacy and closeness Overall satisfaction Total Items 1 to 5

* Copyright 1997 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2002.

6—Very

5—Moderately

4—Somewhat

3—Neutral

2—Somewhat

1—Moderately

Instructions. Use checks () to show how satisfied or dissatisfied you feel in your closest personal relationship. Please answer all 5 items.

Satisfied

Dissatisfied

0—Very

Relationship Satisfaction*

Scoring Keys* Depression, Anxiety, Panic, and Anger Scales

Relationship Satisfaction Scale

Score

Interpretation

Score

Satisfaction

0

no symptoms

0 - 10

extremely dissatisfied

1-2

borderline

11 - 15

very dissatisfied

3-5

mild

16 - 20

moderately dissatisfied

6 - 10

moderate

21 - 25

marginal

11 - 15

severe

26 - 28

moderately satisfied

16 - 20

extreme

29 - 30

Extremely satisfied

Therapeutic Empathy Scale* Score

Satisfaction Level

20

Excellent

19

Surprisingly, this score indicates a failure in the therapeutic alliance.

15 - 18

Not so good

10 - 14

Marginal at best

5-9

Poor

0-4

Alarming

*

Interpretation Good job! The patient appears to be very satisfied with the warmth, trust, respect, and understanding that she or he experienced during the session. A 19 seems excellent, and most therapists would be thrilled with it, but there’s a problem that needs to be addressed. It can be hard for patients to criticize therapists, and you won’t know the extent of the difficulty until you talk it over with your patient. The failure could be mild, moderate, or even severe. There’s definitely room for improvement. Scores of 18 always indicate fairly significant failures of therapeutic warmth, trust, or understanding. Scores of 15 are quite low. There are substantial and potentially serious feelings of dissatisfaction in more than one area. There are severe problems in many areas of the therapeutic alliance. Scores this low are unusual. This score nearly always indicates extreme problems in warmth, trust or understanding that need to be addressed immediately.

Copyright © 1997 by David D. Burns, MD. Revised, 2010.

Brief Mood / Survey Keys

Page 1

Scoring Key: 5–Item Depression, Anxiety, and Anger Tests Score

Interpretation

0-1

Few or no symptoms: the best possible score

2-4

Borderline symptoms

5-8

Mild symptoms

9 - 12

Moderate symptoms

13 - 16

Severe symptoms

17 - 20

Extreme symptoms

2–Item Suicidal Urges Test Item 1

Elevated scores on this item are not unusual. Most depressed patients have some suicidal thoughts or fantasies at times.

Item 2

Here, any elevated score is dangerous. This item assesses suicidal urges. You will need to do a careful suicide assessment, and may need to hospitalize the patient if he or she seems in danger of a suicide attempt.

Anyone with significant symptoms of depression, or suicidal or violent urges, should see consultation immediately with a mental health professional.

Score

5–Item Relationship Satisfaction Test (RSAT)

0-5

Extremely dissatisfied

6 - 10

Moderately dissatisfied

11 - 14

Somewhat dissatisfied

15 - 18

Neutral

19 - 22

Slightly satisfied

23 - 26

Moderately satisfied

27 - 28

Very satisfied

29 - 30

Extremely satisfied

Brief Mood / Survey Keys

Page 2

Scoring Key: Evaluation of Therapy Session Positive Feelings (Items 1 – 5) Score

Interpretation

20

Outstanding — excellent job!

19

There's a problem that should be explored.

17 - 18

Fair — but considerable room for improvement.

15 - 16

Poor — The patient doesn't feel supported or understood.

11 - 14

Warning — The patient seems very dissatisfied.

0 - 10

Extreme problems in the therapeutic alliance.

Scale

Helpfulness of the Session (Items 6 – 10)

Satisfaction with Today's Session (Items 11 – 12)

Your Commitment (Items 13 – 14)

Negative Feelings During the Session (Items 15 – 17)

Difficulties with the Questions (Items 18 – 20)

Interpretation You do not need to interpret the total score on this scale. However, the patient's responses will clearly indicate how helpful the session was. You can encourage the patient to explain which techniques were the most and least helpful. Toward the beginning of therapy, scores on this scale may indicate that the interventions are only somewhat or moderately helpful. This is normal. Once you develop a collaborative relationship, and find methods that lead to improvement, your scores will increase. It's much easier to get "perfect" scores on the Positive Feelings subscale than on the Helpfulness subscale. Again, the total score does not need interpretation, but the specific responses will clearly show how satisfied the patient felt. The responses will indicate whether patients intend to do psychotherapy homework and whether the session will have an impact on their lives. Any score of 1 ("Somewhat true") or above indicates that the patient had some negative feelings during the session. You need to explore these reactions using the Five Secrets of Effective Communication. Any score of 1 ("Somewhat true") or above indicates that the patient had trouble answering some of the items openly and honestly. If you simply ask them which items they had the most trouble with, nearly all patients will tell you! You need to be especially concerned if they had trouble with the suicidal urges questions. If patients had trouble answering the suicidal urges items honestly on the Brief Mood Survey, you will need to do a careful suicide assessment immediately. The patient may need an emergency intervention, such as hospitalization, to prevent a suicide attempt.

Brief Mood Survey / Scoring Keys

Page 1

Scoring Key: 5–Item Depression, Anxiety, and Anger Tests Score

Interpretation

0-1

Few or no symptoms: the best possible score

2-4

Borderline symptoms

5-8

Mild symptoms

9 - 12

Moderate symptoms

13 - 16

Severe symptoms

17 - 20

Extreme symptoms

2–Item Suicidal Urges Test Item 1

Elevated scores on this item are not unusual. Most depressed patients have some suicidal thoughts or fantasies at times.

Item 2

Here, any elevated score is dangerous. This item assesses suicidal urges. You should seek consultation with a mental health professional immediately.

Anyone with suicidal or violent urges should see consultation immediately with a mental health professional.

Score

5–Item Relationship Satisfaction Test (RSAT)

0-5

Extremely dissatisfied

6 - 10

Moderately dissatisfied

11 - 14

Somewhat dissatisfied

15 - 18

Neutral

19 - 22

Slightly satisfied

23 - 26

Moderately satisfied

27 - 28

Very satisfied

29 - 30

Extremely satisfied

Brief Mood Survey / Scoring Keys

Page 2

Scoring Key: Evaluation of Therapy Session Positive Feelings (Items 1 – 5) Score

Interpretation

20

Outstanding — excellent job!

19

There's a problem that should be explored.

17 - 18

Fair — but considerable room for improvement.

15 - 16

Poor — The patient doesn't feel supported or understood.

11 - 14

Warning — The patient seems very dissatisfied.

0 - 10

Extreme problems in the therapeutic alliance.

Scale

Helpfulness of the Session (Items 6 – 10)

Satisfaction with Today's Session (Items 11 – 12)

Your Commitment (Items 13 – 14)

Negative Feelings During the Session (Items 15 – 17)

Difficulties with the Questions (Items 18 – 20)

Interpretation You do not need to interpret the total score on this scale. However, the patient's responses will clearly indicate how helpful the session was. You can encourage the patient to explain which techniques were the most and least helpful. Toward the beginning of therapy, scores on this scale may indicate that the interventions are only somewhat or moderately helpful. This is normal. Once you develop a collaborative relationship, and find methods that lead to improvement, your scores will increase. It's much easier to get "perfect" scores on the Positive Feelings subscale than on the Helpfulness subscale. Again, the total score does not need interpretation, but the specific responses will clearly show how satisfied the patient felt. The responses will indicate whether patients intend to do psychotherapy homework and whether the session will have an impact on their lives. Any score of 1 ("Somewhat true") or above indicates that the patient had some negative feelings during the session. You need to explore these reactions using the Five Secrets of Effective Communication. Any score of 1 ("Somewhat true") or above indicates that the patient had trouble answering some of the items openly and honestly. If you simply ask them which items they had the most trouble with, nearly all patients will tell you! You need to be especially concerned if they had trouble with the suicidal urges questions. If patients had trouble answering the suicidal urges items honestly on the Brief Mood Survey, you will need to do a careful suicide assessment immediately. The patient may need an emergency intervention, such as hospitalization, to prevent a suicide attempt.

Brief Mood / Survey Keys

Page 1

Scoring Key: 5–Item Depression, Anxiety, and Anger Tests Score

Interpretation

0-1

Few or no symptoms: the best possible score

2-4

Borderline symptoms

5-8

Mild symptoms

9 - 12

Moderate symptoms

13 - 16

Severe symptoms

17 - 20

Extreme symptoms

2–Item Suicidal Urges Test Item 1

Elevated scores on this item are not unusual. Most depressed patients have some suicidal thoughts or fantasies at times.

Item 2

Here, any elevated score is dangerous. This item assesses suicidal urges. You will need to do a careful suicide assessment, and may need to hospitalize the patient if he or she seems in danger of a suicide attempt.

Anyone with significant symptoms of depression, or suicidal or violent urges, should see consultation immediately with a mental health professional.

Score

5–Item Relationship Satisfaction Test (RSAT)

0-5

Extremely dissatisfied

6 - 10

Moderately dissatisfied

11 - 14

Somewhat dissatisfied

15 - 18

Neutral

19 - 22

Slightly satisfied

23 - 26

Moderately satisfied

27 - 28

Very satisfied

29 - 30

Extremely satisfied

Brief Mood / Survey Keys

Page 2

Scoring Key: Evaluation of Therapy Session Positive Feelings (Items 1 – 5) Score

Interpretation

20

Outstanding — excellent job!

19

There's a problem that should be explored.

17 - 18

Fair — but considerable room for improvement.

15 - 16

Poor — The patient doesn't feel supported or understood.

11 - 14

Warning — The patient seems very dissatisfied.

0 - 10

Extreme problems in the therapeutic alliance.

Scale

Helpfulness of the Session (Items 6 – 10)

Satisfaction with Today's Session (Items 11 – 12)

Your Commitment (Items 13 – 14)

Negative Feelings During the Session (Items 15 – 17)

Difficulties with the Questions (Items 18 – 20)

Interpretation You do not need to interpret the total score on this scale. However, the patient's responses will clearly indicate how helpful the session was. You can encourage the patient to explain which techniques were the most and least helpful. Toward the beginning of therapy, scores on this scale may indicate that the interventions are only somewhat or moderately helpful. This is normal. Once you develop a collaborative relationship, and find methods that lead to improvement, your scores will increase. It's much easier to get "perfect" scores on the Positive Feelings subscale than on the Helpfulness subscale. Again, the total score does not need interpretation, but the specific responses will clearly show how satisfied the patient felt. The responses will indicate whether patients intend to do psychotherapy homework and whether the session will have an impact on their lives. Any score of 1 ("Somewhat true") or above indicates that the patient had some negative feelings during the session. You need to explore these reactions using the Five Secrets of Effective Communication. Any score of 1 ("Somewhat true") or above indicates that the patient had trouble answering some of the items openly and honestly. If you simply ask them which items they had the most trouble with, nearly all patients will tell you! You need to be especially concerned if they had trouble with the suicidal urges questions. If patients had trouble answering the suicidal urges items honestly on the Brief Mood Survey, you will need to do a careful suicide assessment immediately. The patient may need an emergency intervention, such as hospitalization, to prevent a suicide attempt.

4—Extremely

3—Very

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how depressed, anxious or angry you've been feeling recently. Please answer all the items.

2—Moderately

Brief Mood Survey*

1—Somewhat

Date: 0—Not at all

Your name:

Depression 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Sad or down in the dumps Discouraged or hopeless Low self-esteem, inferiority, or worthlessness Loss of motivation to do things Loss of pleasure or satisfaction in life Total Anxiety

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Anxious Nervous Worried Frightened or apprehensive Tense or on edge Total

1. 2.

Suicidal Urges Do you have any suicidal thoughts? Would you like to end your life? Total Anger

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Frustrated Annoyed Resentful Angry Irritated Total

Total

* Copyright © 1997 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised 2005.

6—Very

4—Somewhat

3—Neutral

2—Somewhat

1—Moderately

Please answer all the items. 1. Communication and openness 2. Resolving conflicts and arguments 3. Degree of affection and caring 4. Intimacy and closeness 5. Overall satisfaction

0—Very

Put the name of someone you care about here: Use checks () to indicate how satisfied or dissatisfied you feel about this relationship.

Satisfied

Dissatisfied

5—Moderately

Relationship Satisfaction Test*

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

4—Extremely true

3—Very true

2—Moderately true

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how much you agree with each of the following statements. Please answer all the items.

1—Somewhat true

Brief Mood Survey (cont'd)*

Page 2

0—Not at all true

Brief Mood Survey

Special Experiences I sometimes hear voices that others do not seem to hear. Others can read my mind or insert thoughts into my mind. I believe that people are trying to control me with electricity, radio waves or other forces. I believe that people can hear my thoughts. I've been receiving special messages from the radio or TV. Total Feelings of Mistrust

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

I believe that people are plotting against me. I believe that people are saying bad things about me. I believe that people are out to get me. I believe people want to harm me or take advantage of me. I believe that people are spying on me or trying to find out about my private life. Total

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Feelings of Superiority I sometimes feel far more brilliant and intelligent than others. I sometimes feel like I have special powers. I sometimes feel like a Messiah or a God. I sometimes feel far superior to others. I sometimes receive special messages from God.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

The doctors and nurses seem warm, supportive, and concerned. The doctors and nurses seem trustworthy. The doctors and nurses treat me with respect. The doctors and nurses do a good job of listening. The doctors and nurses understand how I feel inside. Total

* Copyright © 1997 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised 2005.

4—Completely true

3—Very true

2—Moderately true

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how well these statements describe your feelings about your experiences on the inpatient unit. Please answer all the items.

1—Somewhat true

Therapeutic Empathy Scale*

0—Not at all true

Total

1. Sad or down in the dumps 2. Discouraged or hopeless

4—Extremely

Please answer all the items. Depression

3—A lot

Instructions: Put a check ( ) after each item to indicate how you've been feeling over the past week, including today.

2—Moderately

Brief Mood Survey*

1—Somewhat

Page 1 0—Not at all

Brief Mood Survey Example plus Scoring Keys

3. Low self-esteem, inferiority, or worthlessness 4. Loss of motivation to do things 5. Loss of pleasure or satisfaction in life

Total Items 1 – 5

17

Suicidal Urges 1. Do you have any suicidal thoughts? 2. Would you like to end your life?

Total Items 1 – 2

2

Anxiety 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Anxious Frightened Worrying about things Tense or on edge Nervous

Total Items 1 – 5

16

Anger 1. Frustrated

2. Annoyed

3. Resentful

4. Angry

5. Irritated

Total Items 1 – 5

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Communication and openness Resolving conflicts and arguments Degree of affection and caring Intimacy and closeness Overall satisfaction

6—Very

5—Moderately

4—Somewhat

3—Neutral

2—Somewhat

1—Moderately

Instructions: Place a check ( ) in the box that best describes how satisfied you feel in your closest personal relationship. Please answer all 5 items.

Satisfied

Dissatisfied

0—Very

Relationship Satisfaction*

16

Total Items 1 – 5

* Copyright 1997 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2002.

17

4–Completely true

3–Very true

Please answer all the items.

2–Moderately true

Instructions: Put a check ( ) in the box that indicates how you felt about today’s session.

1–Somewhat true

Evaluation of Therapy Session*

Page 2

0–Not at all true

Brief Mood Survey Example plus Scoring Keys

Positive Feelings 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

My therapist seemed warm, supportive, and concerned. My therapist seemed trustworthy. My therapist treated me with respect. My therapist did a good job of listening. My therapist understood how I felt inside.

Helpfulness of the Session 6. 7. 8. 9. 10.

I was able to express my feelings during the session. I talked about the problems that are bothering me. The techniques we used were helpful. The approach my therapist used made sense. I learned some new ways to deal with my problems.

Satisfaction with Today's Session

11. I believe the session was helpful to me. 12. Overall, I was satisfied with today's session. Your Commitment 13. I plan to do therapy homework before the next session. 14. I intend to use what I learned in today's session.

Negative Feelings During the Session 15. At times, my therapist didn't seem to understand how I felt. 16. At times, I felt uncomfortable during the session. 17. I didn't always agree with my therapist.

Difficulties with the Questions 18. It was hard to answer some of these questions honestly. 19. Sometimes my answers didn't show how I really felt inside. 20. It would be hard for me to criticize my therapist.

What did you like the least about the session?

What did you like the best about the session?

* Copyright © 2001 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2002.

Brief Mood Survey Example plus Scoring Keys

Page 3

Scoring Key: Brief Mood Survey Score

5–Item Depression, Anxiety, and Anger Tests

0-1

Few or no symptoms: the best possible score

2-4

Borderline symptoms

5-8

Mild symptoms

9 - 12

Moderate symptoms

13 - 16

Severe symptoms

17 - 20

Extreme symptoms

2–Item Suicidal Urges Test Item 1

Elevated scores on this item are not unusual. Most depressed patients have some suicidal thoughts or fantasies at times.

Item 2

Here, any elevated score is dangerous. This item assesses suicidal urges. You will need to do a careful suicide assessment, and may need to hospitalize the patient if he or she seems in danger of a suicide attempt.

There are two additional assessment devices for suicidal urges in the Therapist's Toolkit. One is a two-page form that you fill out while interviewing the patient. You ask about urges to live, urges to die, degree of hopelessness, level of planning and preparation for a suicide attempt, presence or absence of deterrents, etc. In addition, there's a two-page self-assessment test the patient can fill out. These instruments may assist you in your evaluation of suicidal urges.

Score

5–Item Relationship Satisfaction Test (RSAT)

0-5

Extremely dissatisfied

6 - 10

Moderately dissatisfied

11 - 14

Somewhat dissatisfied

15 - 18

Neutral

19 - 22

Slightly satisfied

23 - 26

Moderately satisfied

27 - 28

Very satisfied

29 - 30

Extremely satisfied

Brief Mood Survey Example plus Scoring Keys

Page 4

Scoring Key: Evaluation of Therapy Session Positive Feelings (Items 1 – 5) Score

Interpretation

20

Outstanding — excellent job!

19

There's a problem that should be explored.

17 - 18

Fair — but considerable room for improvement.

15 - 16

Poor — The patient doesn't feel supported or understood.

11 - 14

Warning — The patient seems very dissatisfied.

0 - 10

Extreme problems in the therapeutic alliance.

Scale

Helpfulness of the Session (Items 6 – 10)

Satisfaction with Today's Session (Items 11 – 12)

Your Commitment (Items 13 – 14)

Negative Feelings During the Session (Items 15 – 17)

Difficulties with the Questions (Items 18 – 20)

Interpretation You do not need to interpret the total score on this scale. However, the patient's responses will clearly indicate how helpful the session was. You can encourage the patient to explain which techniques were the most and least helpful. Toward the beginning of therapy, scores on this scale may indicate that the interventions are only somewhat or moderately helpful. This is normal. Once you develop a collaborative relationship, and find methods that lead to improvement, your scores will increase. It's much easier to get "perfect" scores on the Positive Feelings subscale than on the Helpfulness subscale. Again, the total score does not need interpretation, but the specific responses will clearly show how satisfied the patient felt. The responses will indicate whether patients intend to do psychotherapy homework and whether the session will have an impact on their lives. Any score of 1 ("Somewhat true") or above indicates that the patient had some negative feelings during the session. You need to explore these reactions using the Five Secrets of Effective Communication. Any score of 1 ("Somewhat true") or above indicates that the patient had trouble answering some of the items openly and honestly. If you simply ask them which items they had the most trouble with, nearly all patients will tell you! You need to be especially concerned if they had trouble with the suicidal urges questions. If patients had trouble answering the suicidal urges items honestly on the Brief Mood Survey, you will need to do a careful suicide assessment immediately. The patient may need an emergency intervention, such as hospitalization, to prevent a suicide attempt.

Brief Mood Survey Example plus Scoring Keys

Page 5

Depression 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

4—Extremely

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how depressed, anxious or angry you've been feeling over the past week, including today. Please answer all the items.

3—A lot

0—Not at all

Brief Mood Survey*

2—Moderately

Date: 1—Somewhat

Name:

Sad or down in the dumps Discouraged or hopeless Low self-esteem, inferiority, or worthlessness Loss of motivation to do things Loss of pleasure or satisfaction in life Total Items 1 to 5 Suicidal Urges

1. Have you had any suicidal thoughts? 2. Would you like to end your life? Total Items 1 to 2 Anxiety 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Anxious Frightened Worrying about things Tense or on edge Nervous Total Items 1 to 5 Anger

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Frustrated Annoyed Resentful Angry Irritated Total Items 1 to 5

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Communication and openness Resolving conflicts and arguments Degree of affection and caring Intimacy and closeness Overall satisfaction Total Items 1 to 5 * Copyright 1997 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2002.

6—Very

5—Moderately

4—Somewhat

3—Neutral

2—Somewhat

1—Moderately

Instructions. Use checks () to show how satisfied or dissatisfied you feel in your closest personal relationship. Please answer all 5 items.

Satisfied

Dissatisfied

0—Very

Relationship Satisfaction*

Therapeutic Empathy 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

My therapist seemed warm, supportive, and concerned. My therapist seemed trustworthy. My therapist treated me with respect. My therapist did a good job of listening. My therapist understood how I felt inside. Helpfulness of the Session

6. 7. 8. 9. 10.

I was able to express my feelings during the session. I talked about the problems that are bothering me. The techniques we used were helpful. The approach my therapist used made sense. I learned some new ways to deal with my problems.

11. 12.

I believe the session was helpful to me. Overall, I was satisfied with today's session.

13. 14.

I plan to do therapy homework before the next session. I intend to use what I learned in today's session.

15. 16. 17.

At times, my therapist didn't seem to understand how I felt. At times, I felt uncomfortable during the session. I didn't always agree with my therapist.

Satisfaction with Today's Session

Your Commitment

Negative Feelings During the Session

Difficulties with the Questions 18. 19. 20.

It was hard to answer some of these questions honestly. Sometimes my answers didn't show how I really felt inside. It would be too upsetting for me to criticize my therapist.

What did you like the least about the session?

What did you like the best about the session?

*

Copyright © 2001 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2003.

4--Completely true

3--Very true

Please answer all the items.

2--Moderately true

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how you felt about your most recent therapy session.

1--Somewhat true

Evaluation of Therapy Session*

0--Not at all true

Page 2

Depression 1. Sad or down in the dumps 2. Discouraged or hopeless 3. Low self-esteem, inferiority, or worthlessness 4. Loss of motivation to do things 5. Loss of pleasure or satisfaction in life

Total Items 1 to 5 Suicidal Urges 1. Do you have any suicidal thoughts? 2. Would you like to end your life? Total Items 1 to 2 Anxiety 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Anxious Frightened Worrying about things Tense or on edge Nervous Total Items 1 to 5 Anger

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Frustrated Annoyed Resentful Angry Irritated Total Items 1 to 5 Violent Urges

1. I’ve had thoughts or fantasies of hurting people. 2. I’ve had the urge to do something harmful or violent. Total Items 1 to 2

* Copyright 1997 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2002.

4—Extremely

Please answer all the items.

3—A lot

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how you've been feeling over the past week, including today.

2—Moderately

Brief Mood Survey*

1—Somewhat

Date:

0—Not at all

Name:

Therapeutic Empathy 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

My therapist seemed warm, supportive, and concerned. My therapist seemed trustworthy. My therapist treated me with respect. My therapist did a good job of listening. My therapist understood how I felt inside. Helpfulness of the Session

6. 7. 8. 9. 10.

I was able to express my feelings during the session. I talked about the problems that are bothering me. The techniques we used were helpful. The approach my therapist used made sense. I learned some new ways to deal with my problems.

11. 12.

I believe the session was helpful to me. Overall, I was satisfied with today's session.

13. 14.

I plan to do therapy homework before the next session. I intend to use what I learned in today's session.

15. 16. 17.

At times, my therapist didn't seem to understand how I felt. At times, I felt uncomfortable during the session. I didn't always agree with my therapist.

Satisfaction with Today's Session

Your Commitment

Negative Feelings During the Session

Difficulties with the Questions 18. 19. 20.

It was hard to answer some of these questions honestly. Sometimes my answers didn't show how I really felt inside. It would be too upsetting for me to criticize my therapist.

What did you like the least about the session?

What did you like the best about the session?

*

Copyright © 2001 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2002.

4--Completely true

3--Very true

Please answer all the items.

2--Moderately true

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how you felt about your most recent therapy session.

1--Somewhat true

Evaluation of Therapy Session*

0--Not at all true

Page 2

4—Extremely

3—A lot

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how depressed, anxious or angry you're feeling right now, at this moment. On the Suicidal Urges scale, indicate how you've been feeling recently. Please answer all the items. Depression (How do you feel right now?)

2—Moderately

Brief Mood Survey*

1—Somewhat

Date:

0—Not at all

Name:

1. Sad or down in the dumps 2. Discouraged or hopeless 3. Low self-esteem, inferiority, or worthlessness 4. Loss of motivation to do things 5. Loss of pleasure or satisfaction in life Total Items 1 to 5 Suicidal Urges (How have you felt recently?) 1. Do you have any suicidal thoughts? 2. Would you like to end your life? Total Items 1 to 2 Anxiety (How do you feel right now?) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Anxious Frightened Worrying about things Tense or on edge Nervous Total Items 1 to 5 Anger (How do you feel right now?)

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Frustrated Annoyed Resentful Angry Irritated Total Items 1 to 5

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Communication and openness Resolving conflicts and arguments Degree of affection and caring Intimacy and closeness Overall satisfaction Total Items 1 to 5 * Copyright 1997 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2002.

6—Very

5—Moderately

4—Somewhat

3—Neutral

2—Somewhat

1—Moderately

Instructions. Use checks () to show how satisfied or dissatisfied you feel in your closest personal relationship. Please answer all 5 items.

Satisfied

Dissatisfied

0—Very

Relationship Satisfaction*

Therapeutic Empathy 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

My therapist seemed warm, supportive, and concerned. My therapist seemed trustworthy. My therapist treated me with respect. My therapist did a good job of listening. My therapist understood how I felt inside. Helpfulness of the Session

6. 7. 8. 9. 10.

I was able to express my feelings during the session. I talked about the problems that are bothering me. The techniques we used were helpful. The approach my therapist used made sense. I learned some new ways to deal with my problems.

11. 12.

I believe the session was helpful to me. Overall, I was satisfied with today's session.

13. 14.

I plan to do therapy homework before the next session. I intend to use what I learned in today's session.

15. 16. 17.

At times, my therapist didn't seem to understand how I felt. At times, I felt uncomfortable during the session. I didn't always agree with my therapist.

Satisfaction with Today's Session

Your Commitment

Negative Feelings During the Session

Difficulties with the Questions 18. 19. 20.

It was hard to answer some of these questions honestly. Sometimes my answers didn't show how I really felt inside. It would be too upsetting for me to criticize my therapist.

What did you like the least about the session?

What did you like the best about the session?

*

Copyright © 2001 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2002.

4--Completely true

3--Very true

Please answer all the items.

2--Moderately true

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how you felt about your most recent therapy session.

1--Somewhat true

Evaluation of Therapy Session*

0--Not at all true

Page 2

1. Sad or down in the dumps 2. Discouraged or hopeless 3. Low self-esteem, inferiority, or worthlessness 4. Loss of motivation to do things 5. Loss of pleasure or satisfaction in life Total Items 1 to 5 Suicidal Urges (How have you felt recently?) 1. Do you have any suicidal thoughts? 2. Would you like to end your life? Total Items 1 to 2 Anxiety (How do you feel right now?) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Anxious Frightened Worrying about things Tense or on edge Nervous Total Items 1 to 5 Anger (How do you feel right now?)

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Frustrated Annoyed Resentful Angry Irritated Total Items 1 to 5 Violent Urges (How have you felt recently?)

1. I have thoughts or fantasies of hurting people. 2. I have the urge to do something harmful or violent. Total Items 1 to 2

* Copyright 1997 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2002.

4—Extremely

3—A lot

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how depressed, anxious and angry you're feeling right now, at this moment. On the Suicidal and Violent Urges scales, indicate how you've been feeling recently. Please answer all the items. Depression (How do you feel right now?)

2—Moderately

Brief Mood Survey*

1—Somewhat

Date:

0—Not at all

Name:

Therapeutic Empathy 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

My therapist seemed warm, supportive, and concerned. My therapist seemed trustworthy. My therapist treated me with respect. My therapist did a good job of listening. My therapist understood how I felt inside. Helpfulness of the Session

6. 7. 8. 9. 10.

I was able to express my feelings during the session. I talked about the problems that are bothering me. The techniques we used were helpful. The approach my therapist used made sense. I learned some new ways to deal with my problems.

11. 12.

I believe the session was helpful to me. Overall, I was satisfied with today's session.

13. 14.

I plan to do therapy homework before the next session. I intend to use what I learned in today's session.

15. 16. 17.

At times, my therapist didn't seem to understand how I felt. At times, I felt uncomfortable during the session. I didn't always agree with my therapist.

Satisfaction with Today's Session

Your Commitment

Negative Feelings During the Session

Difficulties with the Questions 18. 19. 20.

It was hard to answer some of these questions honestly. Sometimes my answers didn't show how I really felt inside. It would be too upsetting for me to criticize my therapist.

What did you like the least about the session?

What did you like the best about the session?

*

Copyright © 2001 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2002.

4--Completely true

3--Very true

Please answer all the items.

2--Moderately true

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how you felt about your most recent therapy session.

1--Somewhat true

Evaluation of Therapy Session*

0--Not at all true

Page 2

Brief Pain Test* 1.

Please circle the number that shows how much physical pain you feel RIGHT NOW? 0 none

2.

3

4

5 6 moderate pain

7

8 intense pain

9

10 worst

1

2 a little pain

3

4

5 6 moderate pain

7

8 intense pain

9

10 worst

Please circle the number that shows how strong your physical pain feels RIGHT NOW? 0 none

4.

2 a little pain

Please circle the number that shows how severe your physical pain is RIGHT NOW? 0 none

3.

1

1

2 a little pain

3

4

5 6 moderate pain

7

8 intense pain

9

10 worst

9

10 worst

What degree of physical pain are you experiencing RIGHT NOW? 0 none

1

2 a little pain

3

*

4

5 6 moderate pain

7

8 intense pain

Copyright © David D. Burns, M.D., 1999

Scoring Key Brief Pain Test Score

Pain Level

0

no pain

1-4

minimal

5 - 12

mild

13 - 24

moderate

25 - 36

severe

37 - 40

extreme

Pilot study at Stanford inpatient unit, N = 95: Reliability Cronbach's coefficient alpha: 99% Convergent Validity Correlation with McGill Pain Questionnaire (15-item test): r(95) = .88 (p < .0001) Correlation with McGill Pain Questionnaire (single pain intensity item): r(95) = .99 (p < .0001) Discriminant Validity Correlation with Brief Depression Test (5-item test): r() = .xx (p < .0001) Correlation with Brief Anxiety Test (5-item test): r() = .xx (p < .0001) Correlation with Brief Anger Test (5-item test): r() = .xx (p < .0001)

Chart Record*

Medication

Dose

Side Effects

Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session

1 Copyright © 2004 by David D. Burns, M.D.

Page 1

# Refills

Medication Record

# Prescribed

Commitment Negative Feelings Difficulties

Satisfaction

Helpfulness

Evaluation of Session

Empathy

Relationship Sat.

Anger

Anxiety

Date of Session

Suicidal Urges

Brief Mood Survey

Depression

Client's Name

Chart Record*

Medication

Dose

Side Effects

Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session

1 Copyright © 2004 by David D. Burns, M.D.

Page 2

# Refills

Medication Record

# Prescribed

Commitment Negative Feelings Difficulties

Satisfaction

Helpfulness

Evaluation of Session

Empathy

Relationship Sat.

Anger

Anxiety

Date of Session

Suicidal Urges

Brief Mood Survey

Depression

Client's Name

Chart Record*

Medication

Dose

Side Effects

Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session

1 Copyright © 2004 by David D. Burns, M.D.

Page 3

# Refills

Medication Record

# Prescribed

Commitment Negative Feelings Difficulties

Satisfaction

Helpfulness

Evaluation of Session

Empathy

Relationship Sat.

Anger

Anxiety

Date of Session

Suicidal Urges

Brief Mood Survey

Depression

Client's Name

Chart Record*

Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session

1 Copyright © 2004 by David D. Burns, M.D.

Page 1

Difficulties

Negative Feelings

Commitment

Satisfaction

Helpfulness

Empathy

Evaluation of Session Relationship Sat.

Anger

Anxiety

Date of Session

Suicidal Urges

Brief Mood Survey

Depression

Client's Name

Chart Record*

Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session

1 Copyright © 2004 by David D. Burns, M.D.

Page 2

Difficulties

Negative Feelings

Commitment

Satisfaction

Helpfulness

Empathy

Evaluation of Session Relationship Sat.

Anger

Anxiety

Date of Session

Suicidal Urges

Brief Mood Survey

Depression

Client's Name

Chart Record*

Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session Before Session After Session

1 Copyright © 2004 by David D. Burns, M.D.

Page 3

Difficulties

Negative Feelings

Commitment

Satisfaction

Helpfulness

Empathy

Evaluation of Session Relationship Sat.

Anger

Anxiety

Date of Session

Suicidal Urges

Brief Mood Survey

Depression

Client's Name

Date of Session

*

Copyright © 2004 by David D. Burns, M.D. Difficulties

Negative Feelings

Commitment

Satisfaction

Brief Mood Survey

Helpfulness

Empathy

Before Session

Relationship Sati'n.

Anger

Anxiety

Brief Mood Survey

Suicidal Urges

Depression

Relationship Sati'n.

Anger

Anxiety

Suicidal Urges

Depression

Client's Name

Chart Record * After Session Evaluation of Session

Date of Session

*

Copyright © 2004 by David D. Burns, M.D. Difficulties

Negative Feelings

Commitment

Satisfaction

Brief Mood Survey

Helpfulness

Empathy

Before Session

Relationship Sati'n.

Anger

Anxiety

Brief Mood Survey

Suicidal Urges

Depression

Relationship Sati'n.

Anger

Anxiety

Suicidal Urges

Depression

Client's Name

Chart Record * After Session Evaluation of Session

Date of Session

*

Page 1

Copyright © 2004 by David D. Burns, M.D.

# Prescribed / # Refills?

Side Effects

Evaluation of Session

Dose

Medication

Difficulties

Negative Feelings

Commitment

Brief Mood Survey

Satisfaction

Helpfulness

Empathy

Relationship Sat

Anger

Anxiety

Suicidal Urges

Depression

Client's Name

Chart Record * Medication Record

Date of Session

*

Page 2

Copyright © 2004 by David D. Burns, M.D.

# Prescribed / # Refills?

Side Effects

Evaluation of Session

Dose

Medication

Difficulties

Negative Feelings

Commitment

Brief Mood Survey

Satisfaction

Helpfulness

Empathy

Relationship Sat

Anger

Anxiety

Suicidal Urges

Depression

Client's Name

Chart Record * Medication Record

Date of Session

*

Page 1

Copyright © 2004 by David D. Burns, M.D.

Difficulties

Negative Feelings

Commitment

Satisfaction

Brief Mood Survey

Helpfulness

Empathy

Before Session

Relationship Sat

Anger

Anxiety

Brief Mood Survey

Suicidal Urges

Depression

Relationship Sat

Anger

Anxiety

Suicidal Urges

Depression

Client's Name

Chart Record * After Session Evaluation of Session

Date of Session

*

Page 2

Copyright © 2004 by David D. Burns, M.D.

Difficulties

Negative Feelings

Commitment

Satisfaction

Brief Mood Survey

Helpfulness

Empathy

Before Session

Relationship Sat

Anger

Anxiety

Brief Mood Survey

Suicidal Urges

Depression

Relationship Sat

Anger

Anxiety

Suicidal Urges

Depression

Client's Name

Chart Record * After Session Evaluation of Session

Fantasies 1. Sometimes I think about getting high. 2. Sometimes I daydream about getting high. 3. Sometimes I fantasize about using drugs or alcohol. 4. Sometimes I crave drugs or alcohol. 5. Sometimes I feel tempted to use drugs or alcohol. Total Items 1 to 5 Urges 6. Sometimes I have the urge to use drugs or alcohol. 7. Sometimes I really want to use drugs or alcohol. 8. Sometimes I really want to get high. 9. Sometimes it’s hard to resist the urge to use drugs or alcohol. 10. Sometimes I have to struggle with the temptation to use drugs or alcohol. Total Items 6 to 10

* Copyright 1998 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2002.

4—Completely true

3—Very true

2—Moderately true

Please answer all the items.

1—Somewhat true

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how much each statement describes how you have been feeling in the past week, including today.

0—Not at all true

Cravings and Urges to Use*

Therapist Instructions for the Cravings and Urges to Use Scale This scale was designed for individuals receiving treatment for alcoholism or substance abuse. It's based on the assumption that the patient is trying to achieve total abstinence. Ask your patients to fill out the test each week, along with the other selfassessment tests to monitor progress. These may include the Brief Mood Survey and the Evaluation of Therapy Session form. You will notice the items don't ask about whether or not the patient actually used drugs or alcohol. They simply ask whether the patient was struggling with temptation. If the patient indicates that he or she did feel tempted to use drugs or alcohol, you can say that it's not surprising, since the urges to use drugs or alcohol can be so strong. Then you can say something like this, "I can imagine it was pretty tempting to give in to the urges. Sometimes it can be hard to resist these temptations. How many times did you use during the week?" In other words, you want to give a non-judgmental message that will make it easy for the person to own up to their substance abuse, so you can work on it in therapy. Once they've owned up to having strong urges, it becomes much easier to own up to using drugs or alcohol. You could also quantify the patient's responses along the following lines, but this type of interpretation is not really necessary for clinical use of the scale: Interpretation Score

Fantasies: Items 1 - 5

Urges: Items 6 - 10

0

No temptation

No urges

1—2

Occasional temptation

Slight urges

3—5

Significant temptation

Significant urges

6 — 10

Moderately strong temptation

Moderately strong urges

11 — 15

Very strong temptation

Very strong urges

16 — 20

Overwhelming temptation

Overwhelming urges

Please fill this out before and after the session. Thank you!

Brief Mood Survey* Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how you're feeling right now. Please answer all the items.

How depressed do you feel right now? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Before Session

After Session

0—Not at all 1—Somewhat 2—Moderately 3—A lot 4—Extremely

Date:

0—Not at all 1—Somewhat 2—Moderately 3—A lot 4—Extremely

Name:

Sad or down in the dumps Discouraged or hopeless Low self-esteem Worthless or inadequate Loss of pleasure or satisfaction in life Total

Total

Total

Total

Total

Total

Total

Total

How suicidal do you feel right now? 6. Do you have any suicidal thoughts? 7. Would you like to end your life?

How anxious do you feel right now? 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Anxious Frightened Worrying about things Tense or on edge Nervous

How angry do you feel right now? Frustrated Annoyed Resentful Angry Irritated

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Communication and openness Resolving conflicts and arguments Degree of affection and caring Intimacy and closeness Overall satisfaction Total

* Copyright 1997 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2010.

Total

5—Moderately 6—Very

4—Somewhat

Satisfied

3—Neutral

2—Somewhat

1—Moderately

Dissatisfied

0—Very

6—Very

5—Moderately

4—Somewhat

Please answer all 5 items.

After Session

Satisfied

3—Neutral

Use checks () to indicate how satisfied or dissatisfied you feel about this relationship.

2—Somewhat

Put the name of a family member here:

Before Session Dissatisfied

1—Moderately

Relationship Satisfaction*

0—Very

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Please fill this out before and after the session. Thank you! Relationship Satisfaction*

Before Session Dissatisfied

After Session

Satisfied

Dissatisfied

Satisfied

Total

5—Moderately 6—Very 5—Moderately 6—Very

4—Somewhat

Satisfied

3—Neutral

2—Somewhat

1—Moderately

0—Very

6—Very

5—Moderately

4—Somewhat

Dissatisfied

Communication and openness Resolving conflicts and arguments Degree of affection and caring Intimacy and closeness Overall satisfaction Total

After Session

Communication and openness Resolving conflicts and arguments Degree of affection and caring Intimacy and closeness Overall satisfaction Total

* Copyright 1997 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2010.

Total

5—Moderately 6—Very

Satisfied

4—Somewhat

2—Somewhat

1—Moderately

Dissatisfied

0—Very

6—Very

5—Moderately

4—Somewhat

Satisfied

3—Neutral

Please answer all 5 items.

2—Somewhat

Use checks () to indicate how satisfied or dissatisfied you feel about this relationship.

1—Moderately

Put the name of a family member here:

Total

Before Session Dissatisfied

0—Very

Relationship Satisfaction*

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

4—Somewhat

After Session

Satisfied

3—Neutral

Please answer all 5 items.

2—Somewhat

Use checks () to indicate how satisfied or dissatisfied you feel about this relationship.

1—Moderately

Put the name of a family member here:

Total

Before Session Dissatisfied

0—Very

Relationship Satisfaction*

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

3—Neutral

2—Somewhat

1—Moderately

0—Very

6—Very

5—Moderately

4—Somewhat

3—Neutral

Communication and openness Resolving conflicts and arguments Degree of affection and caring Intimacy and closeness Overall satisfaction

3—Neutral

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

2—Somewhat

Please answer all 5 items.

1—Moderately

Use checks () to indicate how satisfied or dissatisfied you feel about this relationship.

0—Very

Put the name of a family member here:

Please fill this out after the session. Thank you!

1. 2. 3. 4.

Therapeutic Empathy The therapist seemed warm, supportive, and concerned. The therapist treated me with respect. The therapist did a good job of listening. The therapist understood how I felt inside.

5. 6. 7. 8.

Your Participation I talked about the problems that are bothering me. I was able to express my feelings during the session. I participated actively in the session. I worked on my problems during the session.

Total

Total Helpfulness of the Session 9. 10. 11. 12.

The techniques we used were helpful. I learned some new ways to deal with my problems. The approach we used made sense. What I learned in today's session will be useful. Total Support of the Session

13. I felt close to my family members. 14. Family members were warm, supportive, and concerned. 15. I felt accepted by the other family members. Total Satisfaction with Today's Session 16. Overall, I was satisfied with today's session. Total Your Commitment 17. I plan to do therapy homework before the next session. 18. I intend to use what I learned between sessions. Total Difficulties with the Questions 19. It was hard to be completely honest on this survey. 20. It would be too upsetting for me to criticize the therapist. Total What did you like the least about the session?

What did you like the best about the session?

* Copyright © 2001 by David D. Burns, MD, Revised 2010

4--Completely true

Please answer all the items.

3--Very true

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how you felt about today’s session.

2--Moderately true

Evaluation of Family Therapy Session*

1--Somewhat true

Date:

0--Not at all true

Name:

Please fill this out BEFORE the group begins. Thank you!

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

4—Extremely

3—A lot

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how depressed, anxious or angry you're feeling right now, at this moment. On the Suicidal Urges scale, indicate how you've been feeling recently. Please answer all the items. Depression (How do you feel right now?)

2—Moderately

Brief Mood Survey*

1—Somewhat

Date:

0—Not at all

Name:

Sad or down in the dumps Discouraged or hopeless Low self-esteem, inferiority, or worthlessness Loss of motivation to do things Loss of pleasure or satisfaction in life Total Items 1 to 5 Suicidal Urges (How have you felt recently?)

1. Do you have any suicidal thoughts? 2. Would you like to end your life? Total Items 1 to 2 Anxiety (How do you feel right now?) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Anxious Frightened Worrying about things Tense or on edge Nervous Total Items 1 to 5 Anger (How do you feel right now?)

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Frustrated Annoyed Resentful Angry Irritated Total Items 1 to 5

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Communication and openness Resolving conflicts and arguments Degree of affection and caring Intimacy and closeness Overall satisfaction Total Items 1 to 5 * Copyright 1997 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2002.

6—Very

5—Moderately

4—Somewhat

3—Neutral

2—Somewhat

1—Moderately

Instructions. Use checks () to show how satisfied or dissatisfied you feel in your closest personal relationship. Please answer all 5 items.

Satisfied

Dissatisfied

0—Very

Relationship Satisfaction*

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

4—Extremely

3—A lot

2—Moderately

Instructions. Use checks () to indicate how depressed, anxious or angry you're feeling right now, at this moment. On the Suicidal Urges scale, indicate how you've been feeling recently. Please answer all the items. Depression (How do you feel right now?)

1—Somewhat

Brief Mood Survey*

0—Not at all

Please fill this out AT THE END of the group. Thank you!

Sad or down in the dumps Discouraged or hopeless Low self-esteem, inferiority, or worthlessness Loss of motivation to do things Loss of pleasure or satisfaction in life Total Items 1 to 5 Suicidal Urges (How have you felt recently?)

1. Do you have any suicidal thoughts? 2. Would you like to end your life? Total Items 1 to 2 Anxiety (How do you feel right now?) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Anxious Frightened Worrying about things Tense or on edge Nervous Total Items 1 to 5 Anger (How do you feel right now?)

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Frustrated Annoyed Resentful Angry Irritated Total Items 1 to 5

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Communication and openness Resolving conflicts and arguments Degree of affection and caring Intimacy and closeness Overall satisfaction Total Items 1 to 5 * Copyright 1997 by David D. Burns, M.D. Revised, 2002.

6—Very

5—Moderately

4—Somewhat

3—Neutral

2—Somewhat