Sphaerae Mundi: Early Globes at the Stewart Museum, Montreal 9780773569072

From the Renaissance to well into the nineteenth century, finely crafted, scientifically valuable, and aesthetically sum

125 93 40MB

English Pages 280 [210] Year 2000

Contents

Foreword

Preface

Introduction

An Art Historian's Approach to Globes

CHAPTER 1 Globes from The Netherlands

Introduction

A Pair of Globes by the Blaeu Family: Terrestrial, Circa 1645-48, and Celestial, After 1630

Globes by Gerard and Leonard Valk, Circa 1701-50

Gerard Valk's 1701 Pair of Globes, Reissued Circa 1750

A Valk Celestial Globe, Circa 1745, Set in an Early-Nineteenth-Century Planetarium by A. and J. van Laun

An Anonymous Star Globe, Eighteenth Century

CHAPTER 2 Globes from England

Introduction

A Pocket Globe by Charles Price, Circa 1701

A Pocket Globe by Nathaniel Hill, 1754

John and William Cary's Terrestrial Globe, 1791, in an Early-Nineteenth-Century Orrery by Robert Brettell Bate

An Anonymous Miniature Globe in a Box, with Images of the Earth's Inhabitants, Circa 1825-50

A Terrestrial Globe by Newton, Son & Berry, Circa 1831-33, in an Orrery by Benjamin Martin, Circa 1770

A Pair of Miniature Globes by James Wyld Jr.: Terrestrial, 1839, and Celestial, 1840

CHAPTER 3 Globes from Germany

Introduction

A Terrestrial Globe by Johann Reinhold, Circa 1577-80

Georg Christoph Eimmart's Terrestrial and Celestial Globe Gores, 1705

Franz Ludwig Güssefeld's "Silent Globe," Circa 1792-1805

CHAPTER 4 Globes from Italy

Introduction

Giuseppe de Rossi's 1615 Copy of a 1601 Terrestrial Globe by Jodocus Hondius

A Pair of Matthäus Greuter's Globes: Terrestrial, 1632, and Celestial, 1636

Vincenzo Maria Coronelli's Terrestrial Globe, 1688

A Pair of Globes by Giovanni Maria Cassini: Terrestrial, 1790, and Celestial, 1792

An Anonymous Armillary Sphere, Eighteenth Century

CHAPTER 5 Globes from Sweden

Introduction

Two Terrestrial Globes by Anders Åkerman, Reissued by Fredrik Akrel, 1779 and 1804

CHAPTER 6 Globes from France

Introduction

A Celestial Globe From Blois, 1533, Attributed to the Workshop of Julien and Guillaume Coudray and Jean Du Jardin

Guillaume Delisle's Pair of Globes, 1700, Reissued Circa 1708

A Celestial Globe by Abbé Jean-Antoine Nollet, Circa 1728

Globes by Didier Robert de Vaugondy

A Pair of Globes: Terrestrial, 1773, and Celestial, 1764

A Terrestrial Globe, 1754, Reissued Circa 1773

Ursin Barbay's Glass Terrestrial Globe, 1799

A Pair of Globes by Charles-François Delamarche: Terrestrial, 1801, and Celestial, Circa 1800

Three Armillary Spheres and One Planetarium, Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries

Appendix

Bibliography

Index

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

S

T

U

V

W

Y

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Edward Dahl

- Jean-Francois Gauvin

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

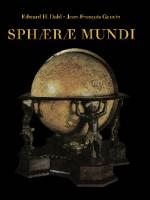

SPHARAE MUNDI

This page intentionally left blank

Edward H. Dahl and Jean-Frangois Gauvin with the collaboration of Eileen Meillon, Robert Derome and Peter van der Krogt

SPHARAE MUNDI Early Globes at the Stewart Museum

SEPTENTRION • McGILL-QUEEN'S UNIVERSITY PRESS

Les editions du Septentrion wishes to thank the Canada Council for the Arts and the Societe de developpement des entreprises culturelles du Quebec (SODEC) for support of its publishing program. We are also grateful for financial support received from the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) for our publishing activities. The Stewart Museum wishes to thank the Quebec Ministry of Culture and Communication, which contributed financial support through its program "Etalez votre science." McGill-Queen's University Press acknowledges the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) for its activities. It also acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for its publishing program. Coordinating Editor: Helene Rudel-Tessier Graphic Design: Folio infographie Photographer: Denis Farley (for the Stewart Museum)

© Les editions du Septentrion www.septentrion.qc.ca English edition co-published by Les editions du Septentrion and McGill-Queen's University Press

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data David M. Stewart Museum Sphaerae mundi. Early globes at the Stewart Museum (French version: Sphaerae mundi. La collection de globes anciens du Musee Stewart.) Includes bibliographical references and index. Co-published by: ISBN 2-89448-159-4 (Septentrion) ISBN 0-7735-2166-6 (McGill-Queen's University Press) i. Terrestrial globes - History. 2. Celestial globes - History. 3. Cartography - History. 4. David M. Stewart Museum, I. Dahl, Edward H., 1945- . II. Gauvin, Jean-Francois, 1969- . III. Tide. GAI95-M66s73 2OOOA

912'.o74'7i428

Legal Deposit - 2nd quarter 2000 National Library of Canada

C00-940844-4

Contents Foreword (Mrs. David M. Stewart)

7

Preface

8

Introduction (Peter van der Krogt)

11

An Art Historian's Approach to Globes (Robert Derome)

25

CHAPTER I

Globes from The Netherlands

67

Introduction A Pair of Globes by the Blaeu Family: Terrestrial, Circa 1645-48, and Celestial, After 1630 Globes by Gerard and Leonard Valk, Circa 1701-50

67

Gerard Valk's 1701 Pair of Globes, Reissued Circa 1750 A Valk Celestial Globe, Circa 1745, Set in an Early-Nineteenth-Century Planetarium by A. and j. van Laun

An Anonymous Star Globe, Eighteenth Century

69 75 77 81

84

CHAPTER 2

Globes from England

87

Introduction 87 A Pocket Globe by Charles Price, Circa 1701 91 A Pocket Globe by Nathaniel Hill, 1754 93 John and William cary's Terrestrial Globe, 1791, in an Early-Nineteenth-Century Orrery by Robert Brettell Bate 96 An Anonymous Miniature Globe in a Box, with Images of the Earth's Inhabitants, Circa 1825-50 98 A Terrestrial Globe by Newton, Son & Berry, Circa 1831-33, in an Orrery by Benjamin Martin, Circa 1770 100 A Pair of Miniature Globes by James Wyld Jr.: Terrestrial, 1839, and Celestial, 1840 102 CHAPTER 3

Globes from Germany

105

Introduction A Terrestrial Globe byjohann Reinhold, Circa 1577-80 Georg Christoph Eimmart's Terrestrial and Celestial Globe Gores, 1705 Franz Ludwig Giissefeld's "Silent Globe," Circa 1792-1805

105 107 no 115

CHAPTER 4

Globes from Italy

119

Introduction Giuseppe de Rossi's 1615 Copy of a 1601 Terrestrial Globe by Jodocus Hondius A Pair of Matthaus Greuter's Globes: Terrestrial, 1632, and Celestial, 1636 Vincenzo Maria Coronelli's Terrestrial Globe, 1688 A Pair of Globes by Giovanni Maria Cassini: Terrestrial, 1790, and Celestial, 1792 An Anonymous Armillary Sphere, Eighteenth Century

119 122 125 131 135 140

CHAPTER 5

Globes from Sweden

143

Introduction Two Terrestrial Globes by Anders Akerman, Reissued by Fredrik Akrel, 1779 and 1804

143 144

CHAPTER 6

Globes from France

149

Introduction A Celestial Globe From Blois, 1533, Attributed to the Workshop of Julien and Guillaume Coudray and Jean Du Jardin Guillaume Delisle's Pair of Globes, 1700, Reissued Circa 1708 A Celestial Globe by Abbe Jean-Antoine Nollet, Circa 1728 Globes by Didier Robert de Vaugondy A Pair of Globes: Terrestrial, 1773, and Celestial, 1764 A Terrestrial Globe, 1754, Reissued Circa 1773 Ursin Barbay's Glass Terrestrial Globe, 1799 A Pair of Globes by Charles-Francois Delamarche: Terrestrial, 1801, and Celestial, Circa 1800 Three Armillary Spheres and One Planetarium, Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries

149 152 154 162 167 167 174 176 178 184

Appendix

190

Bibliography

194

Index

200

Foreword

E

ARLY GLOBES combine science and art. A passion for them came naturally to my husband, who was fascinated with the world around him, cared deeply for his country and its history. He marvelled at how successive discoveries only sharpened the thirst for knowledge. In 1968 we acquired the first globes for the Stewart Museum: a pair of terrestrial and celestial globes by Matthaus Greuter, the first important globe maker in Italy. The terrestrial globe, dated 1632, clearly shows New France and the town of Quebec, using the maps that the great explorer Samuel de Champlain had published in 1613. The oldest globe in the collection is also one of the most spectacular, in itself a work of art. Made in the French royal town of Blois in 1533, this celestial globe was completed just two years before Jacques Cartier ascended the St. Lawrence River to the site of present-day Montreal. I well remember our sense of awe as we saw the Blois globe for the first time. After all these years, it has not lost any of its lustre. The globe collection has continued to grow. For their scientific importance, aesthetic quality, rarity and diversity, globes from several countries and different periods have been acquired. The materials used in these works are various, from exotic woods to hand-blown glass. And globes in all sizes have been added, from a gentleman's pocket-sized globe to Vincenzo Coronelli's terrestrial globe of 1688 — my personal favourite — which has a diameter of 108 centimeters, or three and a half feet. Armillary spheres and planetaria are included in the collection because of the way they help explain the functioning of the universe. Globes do not travel easily, but books do. For their contributions to this book, Spheres Mundi, its coauthors, Edward Dahl, an early cartography specialist formerly at the National Archives of Canada, and Jean-Frangois Gauvin, our curator of scientific collections, have our sincerest thanks. To Eileen Meillon, the museum's map curator and librarian, goes our warm acknowledgement of her gifts of knowledge and assistance. Also crucial to the writing of this book were Peter van der Krogt, a map and globe historian at the University of Utrecht, and Robert Derome, professor of art history at the Universite du Quebec a Montreal. Denis Farley undertook the challenge of painstakingly photographing all the globes so that we could delight in superb reproductions of these works of art and science. Essential to the success of a project of this magnitude was the teamwork of the entire staff at the Stewart Museum. We are delighted to thank them here. The globe collection is one of the centrepieces of the Stewart Museum, which is dedicated to furthering knowledge of the history of the New World. Today, at the dawn of a new millennium, they let us see and celebrate how far we have come in understanding our universe. I hope you will take much pleasure in the pages of this book and become as excited as I remain at both the exceptional beauty and the wealth of geographical information found on the globes at the Stewart Museum. Mrs. David M. Stewart, President The Stewart Museum

Preface

F

EW CURATORS have had the privilege of spending a year immersed in a collection of early globes — studying them, mounting an exhibition, and writing a book about them. But that is how this present work came about. To a few of us, it was no secret that the Stewart Museum had quietly built a substantial collection of globes from about 1530 to 1850, but the extent and richness was still a surprise. The collection was larger and the pieces more complex and less well known than we had originally thought. And the Stewart Museum's broad collections of globe-related material — rare books published by the globe makers, engravings, paintings, along with terrestrial and celestial cartography — enabled us to look at the globes in a larger context. Our study expanded in scope well beyond our original plan. Our aim was to write a book that would be informative for people interested in early globes, but also in related matters such as exploration and mapping, astronomy and celestial charting, antique objects made of diverse and at times exquisite materials, and in the decorative aspects of such early artifacts. We have grouped the globes by their six European countries of origin and devoted a chapter to each country. The chapters open with an introduction to the globe production of that country, followed by an analysis of each individual globe in the collection. We have kept bibliographical and descriptive details to a minimum (the Stewart Museum welcomes further inquiries). Authorship, dates, the construction of the globe itself, the sources used to create the map image, and the globe's place in the history of globe making are dealt with. Seldom does a globe not have some especially intriguing elements, and these we have described and explained. For each terrestrial globe, we have emphasized the cartography of New France, Canada and North America as part of our contribution to what has already been written about these globes. Throughout this project, Eileen Meillon, the Stewart Museum's map curator and librarian, has been a valued collaborator. She researched and wrote the text and captions concerning the Coronelli globe, translated, edited, and proofread texts, tracked down references and copies of the literature, along with many other essential tasks. For the past year, our friend Peter van der Krogt, one of the world's leading specialists in early globes, has been an advisor. His good nature, enthusiasm and generosity with his knowledge throughout the project and during a visit in The Netherlands and in Montreal greatly assisted (and reassured) us on many important points. We are pleased that he has written the introductory essay on early globe history for this book. Robert Derome, an art historian, likewise added a significant dimension to our project. His innovative essay examines the intrinsic link between the decorative arts and globes, a subject little studied, perhaps because globes are traditionally found in libraries and archives, or in history and science museums rather than art galleries. This project benefitted from the help of many collaborators. We would like to thank the following: Goran Baarnhielm (Stockholm); Thierry Bois d'Enghien (Stewart Museum, Montreal); Caroline Bongard (Paris); Jacinthe Bussieres (Montreal); David Coffeen (New York); Elly Dekker (Linschoten, The Netherlands); Johannes Dorflinger (Vienna); Markus Heinz (Berlin); Catherine Hofmann (Paris);

Jason C. Hubbard (Amsterdam); Jan Mokre (Vienna); Heather Murray (Montreal); Carol Urness (Minneapolis); Auguste Vachon (Ottawa); and David Woodward (Madison). Robert Derome, who tapped the knowledge of a wide group of specialists while preparing his essay would like to thank the following: Marc Andre Bernier (Montreal): Peter Bonekamper (Berlin); Fabrizio Bonoli (Bologna); Liliane Caron (Quebec); Bernard Deloche (Lyon); Pieter den Hollander (The Netherlands); Michel Descours (Lyon); Elisabeth Dravet (Clermont-Ferrand, France); Barbara Fischer (Hamburg); Klaus-Dieter Fritzsch (Langwedel, Germany); Sheryl Wilhite Garcia (Houston); Bruno Guignard (Chateau de Blois); Claudette Hould (Montreal); Guido Jansen (Amsterdam); Fennelies Kiers (Amsterdam); Thomas Kloti (Berne); Robert Molle (France); Isabelle Vazelle (Paris); Patrick Vyvyan (Santiago de Chile); Klaus-Peter Wessel (Germany); and Peter Wingfield-Stratford (Oxford). Finally, both the inspired editorial contribution of Josee Lalancette and Helene Rudel-Tessier and the contagious enthusiasm and dedication of our publisher, Denis Vaugeois, encouraged us on days when we feared our energies would expire before the project was completed. His conviction that this would be his most outstanding book of the year sustained us. Globes are complex artifacts, the product of dedicated intellectual effort and skilled and creative artisans. Not enough has been written about early globes, and although significant scholarship has been published, we will feel amply rewarded to learn that our iniative contributes to a fuller understanding and appreciation of these magnificent works.

Introduction PETER VAN DER KROGT*

A Globe according to the Mathematical Definition, is a perfect and exact round Body, contained under one surface. Of this form (as hath been proved) consists the Heavens and the Earth: and therefore the Ancients with much pains Study and Industry, endeavoring to imitate as well the imaginary as the real appearances of them both, have Invented two Globes; the one to represent the Heavens, with all the Constellations, fixed Stars, Circles, and Lines proper thereunto, which Globe is called the Celestial Globe; and the other, with all the Sea Coast, Havens, Rivers, Lakes, Cities, Towns, Hills, Capes, Seas, Sands, &c. as also the Rumbs, Meridians, Parallels, and other Lines that serve to facilate [sic] the Demonstration of all manner of Questions to be performed upon the same: and this Globe is called the Terrestrial Globe.

W

ITH THESE LINES, the great English mathematician and globe maker Joseph Moxon (1627-91) introduces the opening secdon (titled "What a Globe Is") of his treatise, A Tutor to Astronomic and Geographic; or, an easie and speedy way to know the use of both globes, coelestial and terrestrial, published in London in 1670 (first ed., 1659). Moxon's title page claims that his work in six books, "sold at his shop ... at the signe of Atlas," teaches the rudiments of the subject "more fully and amply than hath yet been set forth either by Gemma Frisius, Metius, Hues, Wright, Blaew, or any others that have taught the Use of the Globes," and all this "so plainly and methodically that the meanest Capacity may at first reading apprehend it, and with a little practice grow expert in these Divine Sciences." In this early period, globes were used mainly as aids for calculations and observations in astronomy, whereas in later years, the conformity of the map image with reality became important. Terrestrial globes have a great advantage over flat ("normal") maps since it is impossible to represent the spherical Earth on a flat map without distortion. For small areas,

The Farnese Atlas on preceding page — see Figure 3, page 16

* Map Historian, Explokart Research Program, University of Utrecht, The Netherlands

Introduction

11

even small countries, these distortions are negligible, but for maps of large parts of the world or of the entire Earth, they are significant. The nature of the distortions depends on the method by which the sphere is projected on a flat surface. Some projections cause a change in the shape of an area whereas others change the relative size. For example, in certain projections Greenland appears as large as South America whereas, in reality, the latter is eight times larger. On a globe, such distortions do not occur. A globe provides an almost ideal image of the location and the size of different regions of the planet. The main disadvantage of globes is that they are difficult to handle. A terrestrial globe with a diameter of 31 centimetres (12 inches), the most common size, has a scale of 1:40,000,000, one centimetre equalling 400 kilometres (i inch to 625 miles). In order to obtain a larger scale, the diameter becomes so large that the globe is almost impossible to manipulate. As with the terrestrial globe which shows a representation of the Earth, it is the celestial "sphere" that is shown on the celestial globe. Today we know that the sky is not spherical and that the stars are situated at vast distances from each other even if, viewed from the Earth, they

«>2Turor/0Adronomierf» 460 ff., 497 ff.; Lamb and Collins 1994, 32.

An Art Historian's Approach to Globes 25

Mass-produced or individually made?

Figure 7. The Atlas universel was a major work of the Robert de Vaugondys, father and son, the latter being the author of three globes discussed in chapter 6. This engraved frontispiece appears to be a proof copy before letters: the empty cartouches would contain the table of contents and the publisher's address. We see the chariot of Helios (the Sun) crossing the firmament. On each side are the four continents, armed and surrounded with symbols of their power, and products cultivated on their lands. Below, several cherubs surround a celestial globe. (Gilles Robert [1688-1166] and Didier Robert de Vaugondy [1123-86]. From Atlas universel, Paris, 1151. Copper engraving [proof before letters]; image: 41.4 x 21 cm. Stewan Museum — 1910.3022)

26

SPHLEILE MUNDI

The most interesting decoration is that found on the grand globe stands executed as individual pieces for the aristocracy. The Coronelli globe at the Stewart Museum (fig. 77) is one of these, not only because of the globe itself (of which many copies were produced after the original, commissioned by Cardinal d'Estrees for Louis XIV) but also because of the richly ornate stand with its four caryatids. Several of Coronelli's globes are housed in magnificent settings. The Stewart Museum's Reinhold globe (fig. 62) might have been classified as a unique creation in this class had it not lost most of its upper portion; what remains, however, is of astonishing beauty and technical artistry. The armillary sphere produced at Blois in 1533 (fig. 92) is another impressive piece, as are the stands made by G. Anceau for Robert de Vaugondy's globes (figs. 105 and 106; see also fig. 7) and the magnificent artifacts of the Blaeu family (figs. 38 and 39). Objects such as these are clearly far superior to mass-produced items in the magnificence of the materials and richness of ornament. Most stands and bases, however, fall into the category of the serially produced, both in their methods of manufacture and sale. Globes themselves became serially produced from early in the sixteenth century, when printing allowed multiple copies to be made and sold. This standardization was much influenced by early-seventeenth-century manufacturers in The Netherlands, who set up huge workshops where stands and bases for globes were manufactured in large numbers, the most common type being that with four columns and a central pivot. Nevertheless, some serially made items at the Stewart Museum stand out for their beauty (Benjamin Martin's orrery, fig. 58), their materials (Ursin Barbay's glass globe, fig. 112), or a naive approach reminiscent of folk or primitive art (as in the stands for Giovanni Maria Cassini's globes [figs. 83 and 84] and the pseudo-Italian armillary sphere [fig. 87]). Miniature globes have a fairy-tale look, like toys. The stands for the Swedish globes (fig. 89) share a particular style of moulding in the columns. Manufacturers, patrons and owners A study of the habits of those who commissioned and owned these globes is needed. It is quite likely that globes lacking stands, or with simple stands, could later have been refurbished with more elaborate or costly mountings. Often all we can do is hypothesize, since most of these pieces are unsigned, except for the two stands by G. Anceau for Robert de Vaugondy's globes. The study of the provenance of objects which identifies earlier owners helps art historians identify a particular style that can be linked to the original patron at a given point in time. Unfortunately, in most cases a museum's records do not enable us to establish the object's provenance and history. Although some of the globes themselves provide information — occasionally even the coats of arms of former owners — this informa-

tion cannot provide the date of the stands, since so many copies of the globes were reissued. There are indeed instances where an original stand dates not from the original printing of the globe but from its reissue several decades later. Dating and history Dating globe furniture involves studying the technical characteristics of its production, its state of preservation (including alterations made over the years), and finally the imprecise information afforded by stylistic variations as one "period" flows into another. The most popular styles even reappear in later eras and in different countries. The first thing to note is how conservative in taste most serially made globe stands are; they belong to a sort of international style from no particular time or place. Since few works provide enough information for them to be assigned to a precise style or era, information from other sources is needed. The study of dated illustrations in books, atlases and engravings helps throw more scientific light on models, shapes and styles.

Conservation2 Any analysis of a globe's engraved image must take into account its state of preservation. The upper part has often been damaged, faded by light (as found on the globe reissued by Fredrik Akrel, fig. 89) or affected by dry air and handling (as found on the globes of the Blaeu family, figs. 38 and 39). Rarely does one find original protective covers, as on Gerard Valk's celestial globe of 1707 in the Austrian National Library in Vienna, the Stewart Museum's globe by Ursin Barbay (fig. 112), or the fabric covers depicted in a 1610 print by J. Woudanus of globes at the Leiden University Library. Usually it is the better-preserved lower part of the globe that provides the best evidence for an aesthetic or stylistic study. Many early globes have been damaged and crudely repaired (the globes at the Stewart Museum by the Valks [figs. 43 and 44], by Akrel [fig. 89], and by Cassini [figs. 83 and 84]), while in other cases improper conservation work was done, leaving the yellowed varnish (fig. 29) unevenly distributed (as seen on Robert de Vaugondy's circa 1773 reissue of his 1754 globe, fig. 109). The state of preservation of the stands also provides information which helps determine their dates and their relationship with the globe, as well as to discern later modifications or retouchings. Manufacturing techniques The single most important element in evaluating a globe's stand is the manufacturing technique: vital information is provided by types of wood, the assembly, varnishes and colours. Most globe stands are lacquered or varnished, while others bear more elaborate decoration (Robert de Vaugondy, figs. 105 and 106) or carving (Coronelli, fig. 77). With plainer

The constellation of Virgo engraved on Blaeu's celestial globe. Damage caused by excessive dryness and handling is noticeable. (Willem Jansz. Blaeu [15111638], Celestial globe; detail of the constellation Virgo, circa 1645-48) Reproduction of figure 42, page 13.

2. Van der Krogt 1993, 243; Allmayer-Beck 1997, 118.

An Art Historian's Approach to Globes 27

Figure 8. For his globes, Guillaume Delisle collaborated with several highly qualified artists who had worked with important engravers during the age of Louis XIV. The constellation Aquarius shows the delicateness of the engraving and watercolour done by Charles Louis Simoneau, from a family of artists and engravers, pupil of Noel Coypel and Guillaume Chasteau, rival of Poilly, and Academician in 1710. Note the fine green and soft rose watercolours in the context of scientific cartography without decoration. (Charles Louis Simoneau [1645-1128], Celestial globe; detail of the constellation Aquarius. Watercoloured engraving. Stewart Museum — 1991.24.2)

28

SPELEILE MUNDI

types of globe stands a careful study needs to be made of the assembly and mouldings. Systematic photographic cataloguing of globe furniture of all periods worldwide would show that as decorative art objects these pieces are closely linked with the globes themselves. Stands cast in metal can at times be identified from the signatures (Blois, fig. 92; Reinhold, fig. 62; and Martin, fig. 58). It would be interesting to know why the Cassini globes (figs. 83 and 84) are so much heavier than other globes. Materials and styles A purely chronological approach would rate the Stewart Museum's two oldest globes very highly: one from Blois, the other by Reinhold. The fact that these metal globes were crafted by hand contributes to their outstanding style and beauty. Although the Reinhold globes were serially produced in only a few copies, they are not uniform in the way globes using printed paper gores and produced in large numbers inevitably are. We find a certain repetition of shapes in Reinhold's work as the result of using moulds for some details, but it remains true that at that time the art of metal engraving had not yet developed into an industrial process. Many engraved globes show a high degree of style and craftsmanship:

examples are those by Blaeu, Coronelli, Simoneau (for the globes of Guillaume Delisle, figs. 95 and 96; see also fig. 8) and Arrivet (for the globes of Robert de Vaugondy). A "globographer" noted for his use of glass was Ursin Barbay, who established new standards of technique and refinement in its use. Wood, however, remained the most widely used material for globe bases, in a range of shapes and styles.

Globes and the arts3 A magnificent series of colour photographs of superb decorative art in which globes are included appears in the works of Fauser, Hofmann, Pelletier and Lippincott. These include the Farnese Atlas (a marble nude supporting a celestial globe; see fig. 3 in the present work), exquisite creations from Tehran, along with images of globes in many other mediums and in paintings by great masters such as Jan Vermeer (The Astronomer) and Hans Holbein (The Ambassadors). These masterpieces provide much material for art historians.

Four-column stands with a central pivot 4

1616-51 — A Monk and His Globe, Attributed to Jan van de Venne ' The globe stand with four columns or legs and a central pivot was the most common style, as can be seen in this painting (fig. 9) attributed to Jan van de Venne, born in Mechelen about 1592, and formerly known as the Pseudo-Van de Venne. He was accepted in 1616 as a free master in the Brussels guild and died before 1651. This genre scene was acquired by the Stewart Museum in 1981 from A. Staal, Amsterdam, and came from the art dealer Jacques Goudstikker, whose gallery at 458 Herengracht, Amsterdam, had been in business since 1927. His large art collection was looted by the Nazis during World War II. Goudstikker died in 1940, on his way to South America via England. The painting, which at the time was listed in his inventory book, bears on the back the label of the accountant Polak, who worked until 1941 for Alois Miedl, the Goudstikker company's new director. The depicted scene brings us back to Jan Vermeer's masterful painting, The Geographer. Van de Venne is known for other scenes of trades such as that of the tooth-puller and the writer at work. In the Stewart Museum's painting, we see a scholarly monk in his simple cell with its few sticks of furniture, bent in meditation over a globe, whether celestial or terrestrial is not apparent. The basic archetypal elements defining this most widespread type of globe stand, which can have many variants, are: •

a rounded base mounted on ball-shaped feet, from which rise four round columns of simple construction, each resting on a small square socle;

(Vincenzo Coronelli [1650-1118], Terrestrial globe; detail of the dedication cartouche, 1688) Reproduction of figure 80, page 133.

3. Fauser 1973; Hofmann 1995; Pelletier 1998; and Lippincott 1999. 4. Foucart 1978; De Maere 1994, 1:407 and figs. 1206-8; Den Hollander 1998; Dubois 1998.

An Art Historian's Approach to Globes 29

Figure 9. This oil on 'wood belongs to a very popular seventeenthcentury style of painting in Flanders and The Netherlands catted "genre," which used classic archetypal figures belonging to the collective imagination and therefore immediately recognizable by all. Here, a monk in his austere study leans on a globe, his hands joined, meditating on science or perhaps on the state of the Earth or the heavens. (Jan van de Venne [circa 1592-before 1651], A Monk and His Globe. The Netherlands, circa 1616-51. Oil on wood; 33.5 x 26.5 cm. Stewart Museum - 1981.10.6)

• • •

a central pivot carrying the meridian ring that enables one to change the inclination of the globe and to remove it from its stand; a horizon circle with two slots to hold the meridian ring; a knob that sets the meridian ring at the North Pole and may also be used as a dial.

The stand for De Rossi's 1615 globe (fig. 69) represents a variation on the typical design. It may have been made at any period, since this design was on the market for many years. The beautifully shaped cross-bar is more finely carved than many other common stands. Seventeenth century — The Blaeu family5 (figs. 38 and 39)

(Giuseppe de Rossi ffl. circa 1615], Terrestrial globe, 1615) Reproduction of figure 69, page 122.

30

SPELER.E MUNDI

The simple elegance of the Blaeu stands is entirely appropriate to the aristocratic and scientific image of the globe itself. Several features of these stands are quite remarkable: the unusual style of the columns; the impressive architectural structure of their base with moulded panels; the

elegance of the mechanical support structure highlighted by the simple but refined style of woodwork using various sorts of woods, all somewhat wormholed now. Peter van der Krogt states that globes were always sold in pairs "like a left shoe and a right shoe," and were almost always made at the same time, regardless of what dates appear on either globe. The date of 1630 on the Blaeu celestial globe refers to the period when the positions of the stars were valid, a date usually close to that of the first printing. The dating of the terrestrial globe to about 1645-48 is based on an examination of the geographical information. Historical records show that these globes were still being made for sale in the eighteenth century. The two identical stands, therefore, must be dated after 1645-48, and were probably made after the death of the father, Willem Jansz. (1571-1638) and during the directorship of his son Joan (1598-1673), after the death of the other son, Cornelis (1610-42). The very architectural classical style of these stands can also be seen in the portrait of Mercator and Hondius dating from 1613 (fig. 10), which

Figure 10. These engraved portraits are of Gerard Mercator and Jodocus Hondius, two famous map and globe makers from the Low Countries. Four globes and an armillary sphere are represented, along with maps, atlases, books and related instruments. (Jodocus Hondius Junior [1593-1629], Gerardus Mercator...ludocus Hondius.... Amsterdam, 1613; reprinted 1619. Copper engraving; image: 44.5 x 53.0 cm. Stewart Museum — 1995.111.1)

5. Van der Krogt 1993, 509-15.

An Art Historian's Approach to Globes

31

shows two globes with stands of the four-column type, together with an armillary sphere flanked by two other globes with very plain bases, like those used by Coronelli. 1688 — Vincenzo Maria Coronelli6 (fig. jy)

Figure 11. Coronelli was an exceptional artist and engraver. While in Augsburg in 1686, Coronelli drew this colossal baroque silver ornamental piece made by Christofano Treflero (or Tefleo) and Christofano Rad in 1683. Highly decorated, it serves to support a miniscule armillary sphere above a small celestial globe. Coronelli republished this engraving in his Epitome cosmografica of 1113. (Vincenzo Coronelli, Globe celeste, e sfera armillare, Di Christoforo Tefleo fabbricata in Augusta nel 1683. In Viaggi..., 1697, vol. 1, facing p. 162. Copper engraving; image: 17 x 13 cm. Stewart Museum — E-1691)

6. Hire 1704; Allmayer-Beck 1997, 72, 216; Bobinger 1969, 58 and fig. 13; Coronelli [1693 (1701)] 1969, xv, fig. 6 a-c and n.p.; Wallis and Pelletier 1980. 7. Allmayer-Beck 1997, 64; Pelletier 1998, 98 and fi g- 39-

32

SPILEILE MUNDI

In engraved portraits, Vincenzo Coronelli (1650-1718) is seen with terrestrial and celestial globes on typical four-column stands. The stands that have survived are outstanding for their craftsmanship and beauty, which is perhaps surprising from a Franciscan, a member of an order noted for its asceticism and vows of poverty. Coronelli's gift for draughtsmanship is apparent in the high-quality prints illustrating his books, demonstrating his taste for luxury and the baroque (fig. n). The richness of many of the stands made for his globes is due to various circumstances. To begin with, his work was of exceptionally high quality and his globes were very large, designed for a clientele of monarchs and wealthy nobility; in addition, the stands made by the craftsmen in his workshop were exceptionally well carved. The wealthy individuals who could afford to buy a Coronelli globe could also afford to give this jewel a proper setting in a library, a study or a cabinet of curiosities. Clients such as these had a voice in the selection of the craftsmen who created truly remarkable stands for these larger-than-average globes. The Stewart Museum's Coronelli globe displays all of these characteristics. The base, apparently repaired recently, supports four caryatids and a central decorative motif, both parts being old and showing damage caused by woodworms. The caryatids, human figures with black skin, wear brown slave collars around their necks and black or gold painted palm-leaf skirts with gold and coloured sashes (fig. 12). The four different faces could represent the points of the compass, the continents, the winds or the seasons. Their white turbans with coloured marbling have a diamond motif in the centre which is painted red in the case of the two figures with red-and-green scrolled rear supports, and white for the pair resting on blue-and-yellow painted supports. The red support is the most veined in order to resemble marble. The attractive central decorative element is highlighted in gold leaf on a red ochre size. The use of caryatids or human-shaped stands was common from the sixteenth to the twentieth century. 1700, reissued circa 1708 — Guillaume Delisle7 (figs. 95 and 96) From the eighteenth century on, the French were especially concerned with quality in globe stands and map printing. Delisle's stands display an elegant old-fashioned Louis XIII style of cabinetwork, perhaps going back to a surmised French tradition dating from early in the seventeenth century, the period when it was the Dutch makers who dominated the market in globes. Some of Delisle's known stands were in the ponderous

late-Louis XIV style with four legs ending in fat scrolls, scrolled crossbars and a central flaming urn support. The very handsome base, by an unknown cabinetmaker, is well made. The construction consists of a three-section cross with two struts and a turned and moulded central plate which is attached to the cross-shaped base by wood tenons inserted from below. The central pivot is attached to the plate by a wooden thread which is in perfect condition. The legs are turned in various designs. Note the interesting motif of an inverted pear, found in other works by this anonymous cabinetmaker. The central pivot is also pear-shaped, but not inverted. The red edge of the wooden horizon circle is characteristic of Delisle's work, and indeed of later French craftsmen in the field, including Robert de Vaugondy and Charles-Francois Delamarche. The diagram showing a cross section of the horizon circle demonstrates the technique used and the repainting that has been done (fig. 13). On the upper part of the circle the wood has been covered with white size-like plaster, to which the printed paper has been stuck with a glue, now yellowish. The red colour extends below the edge of the horizon circle and about a centimetre underneath, the rest being roughly covered with a greenishblue colour. The lighter tones of red are retouchings, clearly visible under ultra-violet light. The black colour showing through here and there is the undercoat of varnish applied directly to the wood. The Rotterdam Maritime Museum owns a Valk globe (Mi680) whose stand has been stripped of its paint. The red colour has penetrated deep into the wood, indicating a rougher technique than that used for Delisle's globe furniture.

paper

original paint white size and glue wooden horizon circle

wooden moulding white size later paint and original red paint

Figure 12. The stands for Coronelli globes are often spectacular. This one has large human figures that could represent the cardinal points, the continents, the winds or the seasons. The figures are lightly clothed with loin-cloths and turbans with a red or white diamond motif at the centre. Behind them, to assure their stability, are supports in blue, yellow, red and green, with veins imitating marble. (See enlarged reproduction of this image on page 24, and pages 118 and 131 for the entire globe.) (Vincenzo Coronelli, Terrestrial globe, 1688)

retouching | white lines represent cracks

Figure 13. This cross section (not drawn to scale) of a horizon circle shows the sophisticated techniques for finishing the wood on the stands of Delisle's globes, along with subsequent alterations related to their state of conservation. (Guillaume Delisle, Terrestrial globe, circa 1708. Stewart Museum — 1991.24.1. See also figs. 17, 95, and 96)

An Art Historian's Approach to Globes

33

1701, reissued circa 1750 — Gerard and Leonard Valk (figs. 43 and 44) Seen from above, the stands of the Valks' globes at the Stewart Museum give the impression of being well made in a traditional manner; from below, however, a lowering of standards is apparent in the materials, the streamlining of old, well-tried methods, the thinness of the woods and the plainness of the basic construction. These stands are not in fact very sturdy. The bright red of the horizon circle is a repainting, under which can be glimpsed the deeper red of the old paint. Is there perhaps a French influence here? Valk is known to have kept in touch with the latest scientific publications of the Academic royale des sciences.

1779 — Reissue by Fredrik Akrel of the 1762 globe by Anders Akerman* (fig. 89) A very small stand of great elegance, made with considerable skill in a sober style based on the quality of materials and construction, was created for this Akerman globe reissued by Akrel. The slots into which the meridian ring is to be inserted is slanted, as is that for the central support. The stand consists of three kinds of varnished wood: light-coloured for the platform, dark for the columns and medium for the lower part. An unusual half-sphere motif crowns the finely curved columns, wider at the top than at the base; this is characteristic of the Swedish style and of Akerman's successors. In a self-portrait dated 1758, Anders Akerman depicted his globes, large, medium, and small (fig. 14). The particular style of stand with curved legs derived from a simplified form of French Louis XV furniture is clearly visible.

Figure 14. This self-portrait shows either shelves in a library or in the shop of a cartographer and "globographer," with several examples of different sizes of globes depicted. Akermari's inventive and sophisticated work was taken up by his successors, Frederik Akrel and E. Akerland (see fig. 18), who established the stylistic characteristics original to Sweden in making their products. (Anders Akerman, Self-portrait, 1158. Engraving; image: 10 x 8 cm; see Bratt 1968, fig. 10. Courtesy of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Library.)

8. Bratt 1968, figs. 10 and 12. 9. Dubois 1998.

34

SPILEILE MUNDI

Eighteenth century — Anonymous, Prance, A Scholar in His Study9 (fig. 15) This painting provides very little information: no date, no signature, unknown sitter, provenance unknown before Jean Palardy asked Max Stern to evaluate it when it was given to the Stewart Museum in 1986. The very noticeable crescent Moon seen between the clouds through the window seems to point to a portrait of an astronomer, as in the famous work by Jan Vermeer. But the compass, the design of a triangle on the paper sheet and the globe might also refer to a French ingenieur geographe. The library is one of a scholar in the eighteenth-century sense of the word. The books in the library are by French writers. One work in two volumes is by Jacques Ozanam (1640-1717), a French mathematician elected to the Academic royale des sciences in 1701. The "T[ome]. V is that of a work by Jean-Charles de Folard (Avignon, 1669-1752), a French soldier and writer on military affairs who was publishing in the 17205 and 17305. Another volume is the work of Jean Millet (Grenoble, 1600-75), the poet and actor, and Volume "I" or "III" is by Sebastien Le Prestre, marquis de Vauban (1633-1707), an architect who specialized in fortifica-

Figure 15. This French scholar could be either an astronomer or a French ingenieur geographe. His wide learning is shown by his library containing works of military architecture, mathematics and poetry. The French authors of these works were all active at the end of the seventeenth and the beginning of the eighteenth centuries leaving little doubt as to the origin and date of the oil painting. The subject, who holds a compass with which he draws a triangle on a sheet, touches a blue-green globe which may be terrestrial or celestial. The stand with four turned columns rests on a sturdy square base represented in a visual foreshortening that distorts the perspective. (Anonymous, France, eighteenth century, A Scholar in His Study. Oil on canvas; 89 x 76 cm. Stewart Museum — 1986.8.1)

tions. This eclectic collection of books not only demonstrates that its owner was a cultivated man of varied interests, but enables us to attribute the painting to a French artist active in the mid-eighteenth century. The very particular look of the sitter, together with the precise titles of the books, suggest that this was a real though unidentified person. The man dominates the picture face on, his eyes wide and his left arm resting casually on the globe, the hand enlarged by the perspective in contrast to the right hand which holds a compass. The table with crossbow legs is in the Louis XV style of the mideighteenth century, a period when French taste leaned toward trompe 1'oeil painting for surfaces and textures, as in the imitation marble of the table. The sitter's clothes are of the period. There is nothing to indicate the precise date of the globe, nor whether it is terrestrial or celestial. The stand, of the four-column type, is unusual and surprising, with its sturdy deep square base which appears to be rectangular because of the distorted perspective.

An Art Historian's Approach to Globes

35

Figure 16. Globe stands are rarely signed. Those of Robert de Vaugondy are an exception in having the signature of a cabinetmaker, although his life and work are not known. The excellent quality of the workmanship shows that the unknown "G * ANCEAU" was a remarkable craftsman. He was a member of the Jurande des menuisiers ebenistes (cabinetmakers guild) as shown by the initials "JME," proudly engraved twice on the horizon circles. (G. Anceau for Robert de Vaugondy, Stand for the celestial globe. Stewart Museum — 1992.25.2)

10. Verlet 1982; Pedley 1992, frontispiece and pp. 46-47; Pelletier 1998, 99 and fig. 40.

36

SPH^ILE MUNDI

1764 and 1773 — G. Anceau for Didier Robert de Vaugondy10 (figs. 105 and 106) When these globes first appeared in 1751, they probably had rococo stands such as those portrayed in volume V of the plates in Diderot's Encyclopedic accompanying Robert de Vaugondy's articles on geography and globes, or like the globe once belonging to the Marquise de Pompadour, with its rococo tripod stand with thick scrolled legs and claw-andball feet, and with crosspieces heavily ornamented with carved garlands. The celestial globe represents the second version, 1764; the terrestrial is the third version, from 1773. Since globes were almost always sold in pairs, this one must have been mounted on its stand after 1773 (the date of the last publication), in a transition style that appealed to the Marquise de Pompadour. French styles had evolved considerably over the quarter century, and this stand shows signs of an emerging classical revival, quite different from the Louis XV style of 1751. The signature engraved on the celestial globe, more legible than that on the terrestrial, reads "G * ANCEAU" and twice "JME," the monogram of the cabinetmakers guild (fig. 16). What strikes one first about these stands is the deep black lacquer richly decorated with gold-leaf flower garlands and perhaps also coloured gold, that brings out the rectilinear elegance of the legs' smooth tapering in towards the base. Here the delicate ornamentation of garlands, possibly roses, is somewhat damaged. The grooved central pivot supporting the globe is longer than that of any other globe stand in the collection. The Bibliotheque nationale de France has a globe with a similar stand, but of a design in which the flowers and foliage curl around the legs rather than being arranged in a straight line from top to bottom. The construction of the stands at the Stewart Museum is of thick solid wood on a cross-shaped base. The skillful woodwork is evident from below in the angled design at the centre of the cross, leaving room for the pin supporting the thick grooved central pivot. Some woodworm damage can be seen in the unpainted underside of the wood. One of the four ball

feet has been shortened for stability. There is a fifth one aligned with the central pivot, but it does not touch the ground, being turned differently, like a spindle with a wider core and a longer top designed to steady the long grooved central pivot that it holds in place. The lower surface of the horizon circle was varnished carelessly and shows areas where the red size applied to the vertical components splashed before the lacquering was done. The capitals of the columns are chamfered in the centre to allow the globe to rotate; the chamfering was crudely done with a large chisel. The edges of the meridian ring are painted dark red on a white base; the pink tone over the original white ground seems to be a repainting, perhaps over dark blue or grey. Circa 1800 and 1801 — Charks-Frangois Delamarche (figs. 114 and 115) The stands of the Delamarche globes at the Stewart Museum display elegant turned legs more slender at the base and swelling into a double curve at the top. The central pivot is a shortened version of the same shape. The matte black lacquer is enlivened with flower garlands in gold dust. The edges of the horizon circle have been daubed recently with red paint, covering yellowed stains on the white size. The underside was never painted. But the engraving on the horizon circle is well preserved. The slot for the meridian ring has been repaired and possibly enlarged,

Figure 17. We do not know whether Charles-Francois Delamarche had the stands for his globes made in his workshop, or if like Robert de Vaugondy, he subcontracted this work to specialized craftsmen. This detail from the horizon circle allows us to appreciate both the quality of the engraving as well as certain aspects of its fabrication and conservation: repairing of and enlarging the split that holds the meridian, as well as the colouring where a part of the engraving is missing, and then a recent painting in red of the intersection with the border. (Terrestrial globe. Stewart Museum — 1999.8. See also figs. 13, 114, 115)

An Art Historian's Approach to Globes 37

since the joint has been painted in trompe Poeil the width of the ring to disguise the fact that part of the print is missing (fig. 17). 1804 — Reissue by Fredrik Akrel and E. Akerland of the 1759 globe by Anders Akerman (fig. 89^)

Figure 18. The study of the undersides of globe stands provides important information about fabrication techniques, the quality of materials selected by the artisan, and the cabinetmaker's quite sophisticated techniques of assembly. Such information makes it possible to determine whether a stand is contemporary with the globe or not, as well as to identify repairs, modifications or additions. A better definition of styles and structural variations of each of the globe makers' workshops is then also possible. This photograph shows the exceptional quality of Swedish stands, both in style as well as in their fabrication and assembly techniques. (E. Akerland, Detail from the underside of the stand, 1804. Stewart Museum — 1993.53.2. See also figs. 14 and 89)

11. Allmayer-Beck 1997, 53, 99-100, 159. iz.Fauser 1973, 164-67; Guye and Michel 1970, 6668; Bassermann-Jordan 1972, 363; Myers and Halan 1975; Develle 1978, 17-20, 83-84, 203-4, 2I4'32; Helft 1980, 241-75; Glutton 1982, 20-22; Guerrier 1988, 77-78, 95-96; Beck 1993; Delahaye and Hurtel 1994; Roth 1999.

38

SPELEILE MUNDI

This stand is of fine workmanship in a style similar to those made by Akerman. The sides (inside and out), the underside of the horizon circle and the lower supports for the legs are painted in a handsome dark red directly onto the wood (there is no retouching apparent, and the wood shows through where the light coat of paint has been rubbed away). The horizon circle is laminated with small strips of wood in varying widths. The legs and central pivot are painted black. The grooved columns taper towards the base, with an inverted half-sphere in the upper half of each one. The lower part of the support is reinforced by a wooden octagon and four corner-pieces at the centre of the cross (fig. 18).

Triangular stands Although more rare, triangular and tripod bases were used from the sixteenth to the late-nineteenth century.11 1533 — Blots, Workshop ofjulien and Guillaume Coudray and Jean Du Jardin12 (fig. 92) The beauty of this magnificent piece, the oldest in the collection, is part and parcel of its history, its function and its symbolism. The marks on one of the three branches of the base have not yet been fully deciphered: "[an etched mark, B or 3 or m or n ?] / BLOIS [punchmark in relief in a rectangle] / 1533 [incised work]" (fig. 93). Bruno Guignard, assistant curator of the clock collections at the Chateau de Blois, is puzzled by these inscriptions. Not only is the spelling modern (until the late-sixteenth century the usual form was "BLOYS"), but objects in bronze were very rarely punchmarked; the goldsmiths and clockmakers of Blois tended to sign their works, even the smallest, but almost never dated them. Therefore, Guignard concludes that this globe stand is either highly unusual or a fake. The spelling may be due to the fact that French orthography at the time was not yet standardized. Develle has taken this view, pointing out the existence of "three small sixteenth-century clocks with no maker's name but bearing the engraved factory mark BLOIS [sic] enclosed inside a square or forming a circle." The second clock was seen in 1885 in the collection of Baron Jerome Pichon, a notorious forger who "left behind notebooks giving an account of his work and methods," but who also owned legitimate masterpieces. The third clock, "in the Foulc Collection in Paris, bears the mark BLAIS [sic]." So here we find yet another variant — without a "Y," and with an "A" in place of an "O."

Would a forger choose an unusual spelling or fake an obscure and as yet undeciphered inscription? It is possible, for Pichon did create fictitious hallmarks. But the three we see here look old and authentic: by their imprint neither too soft- nor too hard-edged; by their even wear with respect to the patina (which is seldom the case with fakes); by the carefulness of the punchmarking and the absence of any distortion on the other side of the surface. Pichon's forgeries are recognizable by a clumsy cobbling together of components from different periods with modern additions: such is not the case with this celestial globe. The hypothesis that the globe and its base are two separate pieces brought together later is untenable, given the characteristics in common — of technique, imagery, and style — that make this a unified work. It displays the finish and sophistication to be expected of a notable Blois workshop carrying out commissions for Francois I at the height of the Renaissance, and is indeed a characteristically Renaissance piece. Jean-Francois Gauvin has identified the 1515 Albrecht Diirer woodcut on which the depiction of the constellations is based: 1533 is therefore a likely date, since engraved sources after 1536 show the newly discovered Antinous constellation (see fig. 94). Louis XII was born in Blois and had granted the guilds of the city freedom to follow numerous crafts without the formalities of apprenticeship and the creation of a masterwork. This policy made it possible for many craftsmen to purvey luxury goods such as clocks and silver and gold plate to the court. Many of these artisans were still active under Francois I when he had a new wing added to the chateau between 1515 and 1524. From 1529 to 1536, however, the king spent progressively less time in Blois (an average of 7.5 days a year instead of 33.5), and in 1534 he had an inventory of the palace tapestries drawn up before having them brought to Paris. There may well have been other inventories of valuable artifacts, including perhaps this celestial globe, which we ascribe to the Blois workshop of Julien and Guillaume Coudray and Jean Du Jardin. The royal clockmaker Julien Coudray, one of the world's first watchmakers, made Blois famous for the craft. He was, according to a contemporary, "a brilliant man who knew a great deal about many things." Between 1504 and Coudray's death in 1530, both Louis XII and Francois I commissioned "one of the most skillful craftsmen in the world" to make "globes or clocks of the movement of the heavens ... with which, by means of an ingenious mechanism, one might follow the movement of the stars and their progress through the signs of the zodiac." Coudray made a specialty of this particular branch of clockmaking. After viewing the cabinets in the library of the Chateau de Blois, Cardinal Louis of Aragon wrote of "a magnificent astrolabe of impressive size showing the entire cosmos," and of "a most ingenious clock that registers a number of astronomical phenomena." An inventory of 1544 describes what seem to be armillary spheres or planetaria: "a system of planets of nine moving circles with a movement of seven brass wheels,"

The puzzling signature of the globe from Blois has not yet given up all its secrets: "[a B or 3 or m or n etched with a burin] / BLOIS [punchmark in relief in a rectangle] /1533 [incised]". Several historical facts permit us to attribute it to the famous workshop of Julien and Guillaume Coudray and Jean Du Jardin who made this city famous at the beginning of the sixteenth century. This object is the only globe that remains from this remarkable workshop. (Blois, Workshop of Julien and Guillaume Coudray and Jean Du Jardin, Celestial globe, 1533. Gilded copper, bronze and brass) Reproduction of figure 93, page 153.

An Art Historian's Approach to Globes 39

and another "composed of seven-faced brass globes, most of them without tables and movements." Coudray created many other mechanisms, including clocks "with figures" as well as "astronomical" clocks specifically for churches. He "was able to execute the most advanced mechanisms then known." Coudray continued to live in Blois, "with many companions working with him and under his supervision." He had a tremendous influence in this field but did not follow the court in its progress from place to place. His heirs — Guillaume Coudray, also a scholar and dedicated researcher, and Jean Du Jardin — carried on his work in Blois as clockmakers to the king from 1530 to 1547 and probably until their deaths, the dates of which are not known. This globe seems to be the only object extant from this famous workshop, except for the "remains" of the clock from the former bell tower of the church of Saint-Martin in Vendome executed by Guillaume Coudray, which bears the date 1533 "with an inscription" on one of the decoys. Guillaume Coudray and Jean Du Jardin would therefore have made this celestial globe in 1533, or have finished, punchmarked and/or dated the object made by their master before his death in

!530-

This splendid masterpiece from the Renaissance merits detailed studies that would disclose some unknown aspects of its signature, materials, fabrication, use and history. Its importance would be increased because of the prestige of Blois, city of the chateau of Louis XII and Francois I, as well as the legendary workshop ofjulien and Guittaume Coudray and Jean Du Jardin, inventors of the first watches, makers of globes, astrolabes and mechanical clocks for churches, such as that found at Venddme signed by Guittaume Coudray the same year that this celestial globe was produced. (Blois, Workshop of Julien and Guillaume Coudray and Jean Du Jardin, Celestial globe, 1533. Gilded copper, bronze and brass) Reproduction of figure 92, page 152.

40

SPH.SILE MUNDI

The artifact is made of copper and gilded brass, and possibly some bronze in the casting of the base, in which can be seen a number of small air-holes resulting from the process. A laboratory analysis of the exact composition of the alloys in similar objects from the same period would provide useful information. The openwork globe with its incised ornament of constellations is made up of two halves joined by small screws attached to a reinforcement inside. The columns and the central support are fixed with nuts and bolts. A hole in another branch of the base probably held an ornamental element or an instrument such as a compass. Noteworthy is the magnificent but restrained moulding of the base and the especially elegant and effective design of the curved template. The square socles rise to a rounded column ornamented with toruses, scotias and a central motif made up of five palm leaves. The base of the circular central column is embellished with tiny square corbels repeated above, just below the globe support. The tops of the three columns, composed of nude male putti with a pronounced contmpposto, each support one of the six half-meridians attached to the horizon and fixed at their head by screws. The three other half-meridians are decorated by an ornamental star at the level of the heads of the putti, giving unity to the design and a pleasing balance. Each putto holds a shield of a different size and shape, decorated with oblique stamped stripes in a wavy or chequered pattern, resting on the ground. Two putti hold their shields with the left hand, their right hands resting on their hips. The third, the one above the signature on the base, holds his shield with his right hand and holds his left arm up towards the globe with his hand open (fig. 19), indicating a link between the hallmark "BLOIS," the city where Coudray had set up his workshop specializing in

Figure 19. The sophisticated details of this exceptional object allow us to penetrate its deepest mysteries with symbolic interpretation. During the Renaissance, Francois I liked to be surrounded by scholars from all disciplines. This pagan world of terrestrial and intellectual enjoyment is shown to us in a small detail of one of the three putti who is lifting his left arm towards the celestial sphere while the other two are in a traditional contrapposto position, also called "weight shift" in English (www.anlex.com). This detail, far from being trite, allows us to relate the world of scientific discoveries and astronomical techniques and the arts with that of astrological interpretation and alchemy. This putto makes the bridge between the signature of BLOIS and the date of 1533, situated at his feet, with the celestial globe above his head. Note that the left arm, here flung out, is that of the heart, of passion and of magic. (Blois, Workshop ofjulien and Guillaume Coudray and Jean Du Jardin, Celestial globe, 1533. Gilded copper, bronze and brass. See fig. 92, p. 152)

An Art Historian V Approach to Globes 41

clockwork movements representing the heavens, and the "astrology" depicted on the globe, pointed out by the left hand, symbolizing the heart, passion and magic. Eighteenth century — Robert Brettell Bate (fig. 55) and Benjamin Martin (fig. 58) Although produced by a more mechanized process, these three-legged orreries with their sophisticated design bear witness to an interesting shift in style. Martin's books published in 1759 and 1762 show the simultaneous use of a very ornate rococo style and a restrained neoclassicism in

Figure 20. Anonymous, The Stellated Planetarium shewing the Inferior Planets, Direct, Stationary & Retrograde among the Fix'd Stars by B. Martin, 1159. Engraving; image: 16.8 x 14 cm. Martin 1759, facing p. 89. Stewart Museum — G-1159. Figure 21. Anonymous, A New Orrery by Clock-Work Engraving; image: 18.4 x 12 cm. Martin 1162, Plate V facinv p 186 Stewart Museum — G-1162.

42

SPH.EILE MUNDI

both his orreries and his armillary spheres. It is therefore quite difficult to date his work precisely, since he employed several different styles at the same time (figs. 20 and 21). He even combined French design (Louis XV style) with English (lion-paw feet). However, by around 1800, rococo was no longer fashionable (although it would again become so in midnineteenth-century England under the title of "rococo revival"). Circa 1815-30 —Abraham and Jacob van Laun^ (fig. 47) This stand, so much more impressive than the little globe it supports, is similar in shape to the typical model of a pedestal table transformed into a scientific instrument. The original globe dated from 1745, but the brass stand was manufactured about 1815-30, probably at about the same time as the elegant marquetry-work table embellished with the signs of the zodiac and the names of the months in various colours and textures of woods. The triangular base with its large claw feet and grooved shaft is probably of a later date. It is clumsily attached to the table and is of greatly inferior workmanship and materials.

Monopode stands There is little to say about monopode or pedestal stands with a turned stem from the point of view of beauty or style, since they are common everywhere, in all periods. 1577-80 —Johann Reinhold "from Lofinitz"1* (fig. 62) Although it is quite small, the terrestrial globe by Johann Reinhold (circa 1550-96), the second oldest in the collection, is remarkable not only for its workmanship and beauty but also because it is the only known piece of the craftsman's output on which the signature is followed by the town name of Lofinitz: "made by Joannes Reinhold who comes from or from near LOES NIZA [translated from the Latin]" (fig. 63). A certain Johann Reinhold was certainly born there in 1556, as were the children born of his marriage to Maria Foerster on 24 September 1581: Barbara, born i January 1582, and Hanfi born in 1589 and married to Dorothea Schmidt on 6 November 1614. It is not easy to reconcile this information with the family history of the Augsburg clockmaker of the same name, also a maker of globes, who, according to Bobinger (1969), was born in Legnica, Poland, but had a different wife and children. The first written evidence of Reinhold's residence in Augsburg is his application to the guild in 1577. Describing himself as "apprentice clockmaker of Lofinitz," he attests that he has worked as such in Augsburg for the past ten years with several masters and fellow apprentices. This globe therefore dates from this period, that is, from 1577-80. As he was not yet a master clockmaker, it is understandable that he signs his work with the name of the city of Lofinitz where he was an appren-

In spite of its very small size this terrestrial globe by Johann Reinhold, the second oldest globe in the collection, is remarkable for its technical and aesthetic qualities, but also for the signature, the only one of his works to identify the city of Lbfinitz: this globe ''''has been made by loannes Reinhold who comes from, or near LOES NIZA [translated from Latin].'" (Johann Reinhold, [Legnica, circa 1550-1590 Augsburg], Detail from an engraved plate under the terrestrial globe. Gilded bronze, wood, glass. Stewart Museum — 1987. 15.1) Reproduction of figure 62, page 107.

13. Van der Krogt 1993, 364 ff. 14. Bobinger 1969, 58-59 and fig. 8; FamilySearch 1999.

An Art Historian's Approach to Globes 43

Figure 22. Six globes by Reinhold and Roll are known, two of which consist only of the celestial globe. (Georg Roll, [Legnica 1546-1592 Augsburg], Johann Reinhold, [Legnica, circa 1550-1590 Augsburg], Celestial and terrestrial globes, 1583-84. Bronze, gilded copper, partially painted silver, wood, iron for the mechanism, H. 54 cm. Courtesy of the Kunsthistorisches Museum KK 584, Vienna)

44

SPH&RJE MUNDI

tice. The inscription "A. LOES NIZA" indicates, therefore, Reinhold's own provenance and not the place of manufacture of the globe. This piece represents his earliest signed work. His clock of 1580 is signed from Augsburg. A work of 1583 (Hayden Planetarium, New York) bears an inscription which indicates his professional status: "The clockmaker and craftsman Johann Reinhold made this very useful new kind of astrolabe, with many features, and it has therefore recently been accepted by the guild at Augsburg [translated from the Latin]." In 1584 Reinhold became master of "small clockmaking" in Augsburg, married, and began to prok duce a series of globes in association with Georg Roll (1546-92). Six of these, signed by one or both of the partners, were produced along the same lines and present the same sort of ornament. Four are complete, comprising a stand with a small terrestrial globe together with an imposing four-legged baroque stand holding a large celestial globe, some (in Vienna, Dresden, Paris, and St. Petersburg) are topped by an armillary sphere or a female figure. Of the other two (in London and Naples), only their celestial globes remain. The one at Greenwich is different, being supported by human figures. Was the Stewart Museum's Reinhold globe designed as it stands, or is it missing its celestial globe (fig. 22)? i The base of the Stewart Museum's globe rests on a mercury-coated metal plate composed of two parts sol. dered together (the long- line of solder is apparent underneath the plate when it is lifted from its wooden base). The superb carving of the foliated scrolls (fig. 23), similar to that on Reinhold's clocks, includes a compass in the centre and a hand. Note the four Suns with axis lines, figures and vertical pointers, one of which is broken. The chiselling on the cornerpieces has a different style. Long lists of placenames are also engraved. The four slotted pins, one of which is broken, would have supported the four feet of a missing upper section containing a celestial globe. The exquisite craftsmanship of the piece is apparent in the small silver plate above the globe (fig. 24) with its coloured enamel inlay (gold, green and purple) of seven flowers: two large purple and gold ones, separated on one side by two gold clover leaves, and on the other by four-petalled flowers of various colours (gold, green, purple, and one missing) and a five-petalled flower. The globe is engraved with splendid depictions of ships and sea monsters (fig. 25).

1632 and 1636 — Matthaus Greuter in Rome (figs. 71 and 72) There is no information to confirm that these monopode stands are contemporary with the globes they support. The absence of any printed paper glued to the horizon circles suggests that they are of fairly recent manufacture, possibly from the nineteenth century. The crude woodwork is painted dark red. The meridian ring of the celestial globe is in poor condition. Circa 1773 — Reissue of Robert de Vaugondy's 1754 terrestrial globe (fig. looj A larger market for French products led to the development of less costly globe furniture and armillary spheres in which papier mache was much

Figure 23. Admire the magnificent scrolled chasing and chiselling, similar to that of his clocks, here with a compass in the centre and a pointer hand. Also notice the four suns with the sundials, hours and gnomons, one of which is broken. The tooling on the corner-pieces has been done with a different method. Long texts with lists of place-names are engraved with punches. (Johann Reinhold, [Legnica, circa 1550-1590 Augsburg], Detail from an engraved plate under the terrestrial globe. Gilded bronze, wood, glass. See fig. 62, p. 107)

An Art Historian's Approach to Globes 45

Figure 24. The dial engraved on top of Reinhold's globe, finely done in silver with inlaid coloured enamel (gold, green and purple), is decorated with seven flowers: two large purple and gold, separated on one side by two three-leaved clover leaves and on the other by two flowers with four petals of different colours (gold, green, purple and missing) as well as another flower with five petals. (Johann Reinhold, [Legnica, circa 1550-1590 Augsburg], Detail from the terrestrial globe. Gilded bronze, wood, glass. See fig. 62, p. 107)

46

SPH^ILE MUNDI

used — for example, by Robert de Vaugondy and Delamarche. Robert de Vaugondy's medium-sized globe rests on a monopode base of dark wood under which one can see traces of the concentric lines of the turning process. The four supporting arms, the horizon circle and the meridian ring are of papier mache; the layers of cardboard can be seen in the slots of the horizon circle. All edges inside and out are covered with several coats of red paint on a white size. 1790 and 1792 — Giovanni Maria Cassini (figs. 83 and 84) The naive, crude, primitive-art aspect of these stands is most apparent in the rough construction of laminated boards visible under the base, the black-and-orange decoration, the cutout folds on the base, the imitation brown marble baluster and green marbled volutes. The quality of this is

far from the standard four-column stand for another globe by the same cartographer dated about 1790, which is owned by the Museo della Specola in Bologna. 1799 — Ursin Barbay at Montmirail (fig. 112) The monopode wood support of this glass globe is striking in its simplicity, providing a perfect contrast to the globe itself, the luminescent qualities of which reflect the ocean-dominated surface of the "blue planet." The interior of this sphere of translucent blue glass is unpolished. The continents are shown on printed paper glued to the surface. The horizon and the meridian, as in other French globes of the period, are of papier mache. A cover of transparent glass with a wooden knob forms a protective shell. Turner (1996) describes the achievements of the glassblowers

Figure 25. Reinhold's globe is engraved with several magnificent figures of ships and marine monsters. The excellent quality of this hand engraving makes this an exceptional object. (Johann Reinhold, [Legnica, circa 15501590 Augsburg], Detail from the terrestrial globe. Gilded bronze, wood, glass. See fig. 62, p. 107)

An Art Historian's Approach to Globes 47

who made globes and orreries, one of the foremost being Ursin Barbay, who published a book on the subject in 1817. Barbay made armillary spheres and "universal spheres" consisting of up to four glass concentric spheres. He was also the inventor of the "agnomonic" globe.

Miniature globes Tiny globes are personal, private pleasures, like childhood toys, simply to be played with. The pocket globes made by Charles Price (fig. 52) and Nathaniel Hill (fig. 53) come in their own cases covered with shagreen, the skin of certain sea creatures (shark or ray) specially treated to cover cases, scabbards or the hilts of swords. This tough, black, fine-grained "leather" has been tailored to a spherical shape. Two slots at the poles may indicate that the globes used to be mounted on supports.

1839 and 1840 —James Wyld Jr. (fig. 60) Ursin Barbay ys globe shows his mastery of an unusual material, glass, but this is also an example of the difficulty in conserving antique globes. The cover is a great help since the upper part of globes made from engraved paper gores have often deteriorated because of light, handling, abrasion and accidents. (Ursin Barbay, Terrestrial globe, 1799. Glass, paper, wood, metal. Stewart Museum — 1993.48.1) Reproduction of figure 112, page 176.

15. Maurice and Mayr 1980, 80 and fig. 28; Bennett 1997; Bud and Warner 1998, 283°16. King 1978, 26 and figs. 2.11-2.12); Maurice and Mayr 1980, 80 and fig. 28; Coronelli 1697, 163; Coronelli 1713, i: facing p. 162, and 372. See also fig. 10 in the present chapter.

48

SPH^R^I MUNDI

Ornament is kept to a minimum in these charming little globes in order not to distract from the cartographic information about the Earth and the heavens. The plain monopode base with turned stems is as modest as the beaded border surrounding the cartouches.

Armillary spheres15 These fascinating and complicated objects, whose Latin name means "bracelet," belong to the category of mathematical instruments and depict the universe by means of several rings or circles superimposed on each other and which follow the path of the stars (equator, ecliptic, tropics). In Ptolemy's system the central sphere is the Earth; this is the "anthropocentric" universe also known as the zodiacal universe. The universe of Copernicus (1473-1543) was Sun-centred, while that of Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) used "equatorial" coordinates. By moving the rings the user could calculate the movements of the heavenly bodies for purposes of teaching or research. The armillary sphere, a cumbersome instrument, was replaced by other instruments. The armillary sphere is an ancient invention, used in Greece from the third century B.C. and in China from the Han dynasty (207 B.C.-A.D. 220). It became popular in the West by providing a "geocentric" view of the universe as reformulated by Ptolemy (second century A.D.). Johannes Regiomontanus (1436-76) was one of the first documented makers of armillary spheres. Dating armillary spheres16 None of the Stewart Museum's armillary spheres can be dated exactly, but the museum's early books, prints and atlases provide dated illustrations showing the developments in the shape and style of the stands.