No Sundays in the bush : an English jackeroo in Western Australia 1887-1889 9780850912968, 0850912962

135 111 22MB

English Pages [144] Year 1987

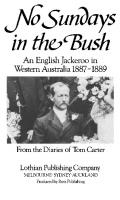

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Page

Contents

Introduction

Part 1 A New Chum

Part 2 To The South

Part 3 An Old Hand

Back Matter

Footnotes

Back Cover

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Tom Carter

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

in the,'Bush An English Jackeroo in Western Australia 1887-1889

From the Diaries of Tom Carter Lothian Publishing Company MELBOURNE· SYDNEY ·AUCKLAND Produced by Ross Publishing

PREVIOUS PAGE:

The author on his wedding day, 1903

First published 1987 Produced by Ross Publishing for Lothian Publishing Company ©Violet Caner, 1987 This book is copyright. Apan from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no pan may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries should be made to the publishers, Lothian Publishing Company Pty Ltd, 11 Munro St, Pon Melbourne, 3207. Carter, Tom, 1864--1931. No Sundays in the bush; an English jackeroo in Western Australia. 1887-1889. ISBN 0 85091 296 2 l. Caner, Tom, 1864--1931- Diaries. 2. Jackeroos- Western AustraliaCarnarvon region- Biography. I. Title.

636.3'0092'4 Designed by Sandra Nobes Photo Research: Jennifer H. Muir Typeset by Meredith Typesetting Printed by Globe Press, Melbourne

Contents Introduction

vii

PART 1 A New Chum

1

PART 2 To The South

37

PART 3 An Old Hand

75

Footnotes

131

Introduction

M

y Father Thomas Carter - always known as Tom Carter- was born at Burton House, Masham, Ripon, Yorkshire, on 6 April 1864, the eldest surviving child of James and Amelia Carter. Burton House, a delightful old stone house, had been the home of the Carter family for several generations. As a child Tom went first to the village school at Masham for a few years and then to Sedbergh School, leaving there in July 1880. One of the Masters there, realising his love of natural history, helped him all he could in this hobby, which lasted throughout his life. After leaving school he worked for several years in Mincing Lane, London, in his Father's office (his Father being an East India merchant), but City life did nor appeal to him. While working there he met some people on a visit from Western Australia; they became close friends and he worked for them when he went there. Their accounts of life in Western Australia inspired him and he decided he must go himself as a 'new chum' to take up sheep farming. He left London in 1886, sailing on the 900 ron Australind, and arrived in the Carnarvon Roads in February 1887. He worked as a 'new chum' for just over two years, returning to England for a short trip in May 1889, and his many and varied experiences during these two years are contained in the narrative he composed from his diaries - most meticulously kept - which appear reproduced in the following pages. Since childhood he had been a keen naturalist, birds being his greatest interest, and Western Australia provided plenty of scope with its unusual bird and animal life and the colourful wild flowers. He visited the islands in Shark Bay many times and in later years had his first sheep station near Point Cloates. He had a small cutter and used to sail along the coast there, and realising the reefs were incorrectly charted, accounted for a number of shipwrecks in that part of the coast. He reported this to the Admiralty and at one time his name appeared on the Admiralty charts for that area - a signal honour. He left Point Cloates about 1903 and returned to England to marry his childhood sweetheart, Annie Ward from Twickenham. Later that year they returned to Perth and settled on a sheep station at Broome Hill, to be called Wensleydale from his childhood days, leaving there in 1914 to return to England to live, although he made several visits to Western Australia afterwards. Tom Carter was of a quiet retiring nature but with a lively sense of humour. He was probably happiest in the country in some quiet spot watching birds

vii

through his spyglass, binoculars being useless as he had been blind in his left eye since birth. In spite of this he was a crack shot and had shot at Bisley. He was rejected for Active Service in 1914 because of this blindness but joined the East Surrey Volunteers. He contributed to various journals and books on the subject of birds whilst living in Australia and also later; his knowledge on the subject was considerable. His childhood spent in Wensleydale in the Yorkshire Dales proved to be of great advantage to him in his travels and experiences in the Bush and he was never at a loss to find a solution to any of the daunting trials which arose constantly and the various contingencies arising which had to be solved. He was a keen horseman and amazing distances had to be travelled in this manner 100 years ago through almost unknown country driving large flocks of sheep through scrub or almost desert areas. There was no doubt Tom Carter loved the life and the challenge it brought. Mention must be made of the Aborigines, many of whom worked for him and well, their knowledge of the land and water holes and poisonous insects or snakes being a great advantage when travelling. Tom Carter had a marvellous collection of Australian specimens of birds and after his death more than 1,000 were given to a museum. He found several unknown birds but his greatest joy was in his discovery of Eremiomis carteri - the Spinifexbird, a beautiful thrush-like bird which is peculiar to NorthWest Australia and the Northern Territory. He died in 1931 after several years of ill health but after a full and most interesting life. Violet Carter Brecon, Wales, 1987

viii

The S.S. Australind on which Tom Carter travelled to Carnarvon in 1887. Carnarvon is situated on ShaTk Bay on the TWTth-west coast of Western Australia.

PARTl

ANew Chum O

ur good little steamer, the Australind, 900 tons, dropped anchor in the Carnarvon Roads at 4 p.m. on the 6th February 1887. The Roads are part of Shark Bay, sheltered by the islands of Dirk Hartog, Bernier and Dorre to the West. A good many residents came out on the sailing lighters to see the first electric-lighted steamer that had visited that coast. Amongst others was J. Brockman, of Boolathana Station, seventeen miles out from Carnarvon. He, being an old friend of Mrs. Gale's, agreed to take me on as 'New Chum', or 'Jackeroo', without wages, as is the custom at first. The usual free and easy concert was held until late at night in the Smoking Room, which I quitted in order to get my two trunks put on one of the lighters. Assisted by the boatswain, I was in the act of lowering one trunk over the vessel's side when someone, whose identity I never discovered, came up and advised me to put my luggage on the other lighter if I wanted to have my belongings taken quickly to the shore. Fortunately for me I followed his advice; when those for the shore went to find their respective boats at 2 a.m. it was discovered that the other lighter was missing, and had evidently had the lines securing her to the steamer maliciously cut. She washed up on the beach about twelve miles North the next morning, and went to pieces. The boat I was in, after bumping over several sandbanks, eventually grounded hard and fast when near the Southern mouth of the Gascoyne River and we all had a long wade to reach the shore, just as day was breaking. We made our way to the Carnarvon Hotel (Townshend proprietor) and succeeded, after some trouble, in awakening the maidservant (Kitty Lingtot) and persuading her to supply us with drinks, after which we found vacant beds and turned in until breakfast.

The Gascoyne Hotel at Carnarvon. Bush hotels in Australia were built to accommodate the large numbers of itinerant workers and travellers mooing through Australia, as weU as off duty station owners, managers and workers.

At that date, Carnarvon contained about one hundred inhabitants, a large proportion consisting of Government officials, the Resident Magistrate (C. D. V. Foss, a son of Colonel Foss, previously Commandant at Fremantle Gaol in the convict days), Land and Water Police, Post Master, Telegraph officials, Schoolteachers and Doctor. Here I may remark that the duel that had been arranged on board the Australind (one of the participants being Dr. Roberts, who had come out to replace the old resident Doctor Shields) did not take place, both men being, as a matter of fact, too shaky for anything of the sort. Dr. Shields spent a good part of the day feeling Roberts's pulse, and murmuring at intervals, in a gratified tone, 'Getting normal- almost normal again'. The township consisted of about a dozen corrugated iron buildings (two of which were 'Hotels') and three general stores, built in dangerous proximity to the South bank of an arm of the great Gascoyne River. Behind the town, at a short distance, was a scrubby, sandy ridge, where numbers of natives camped behind their breakwinds of broken bushes, for they do not trouble to build huts. On the opposite side of the River branch was Babbage Island, mostly low, swampy, and fringed with mangroves. When the River runs, the bulk of the immense volume of water flowing down it reaches the sea by the North Channel, on the North side of Babbage Island. When we landed, the River had not run strongly for some time and was then dry, with the exception of scattered pools. Yankee Town was a small suburb situated on the bank of the River about two miles from Port, consisting then of the houses of two or three settlers. One of them was owned by a burly and genial Scotchman with a large family, and one or two pleasant evenings were spent there in dancing and singing.

2

The Port of Carnarvon, with the pearling fleet at anchor.

A few days were spent here before Brockman left for his Station. One afternoon, in company with J. Bussel from Margaret River, South-West Australia, I walked out to the River bed proper, above tidal influence; this is about one mile from the township. There were steep banks of clay or sand about twelve feet high to the River bed, which is formed of deep, coarse sand and gravel and is about a third of a mile wide, with islands of some size in places. A fringe of large white gum trees lined each side of the River, their pure white trunks and green tops having a pleasing effect. Great flocks of white cockatoos (Cacatua sanguinea) 1 assembled in the trees near pools of water - many of which are permanent - and we shot several of them. These birds have to be stalked with a considerable degree of care, as one or more sentinels are always on the alert. The idea is to approach so as to be able to fire a raking shot along a branch crowded with cockatoos, when ~rhaps a dozen birds might fall to a shot. The large kingfisher (Dacelo leachii) also occurs plentifully along the River banks. They resemble, but are not so large as the laughing jackass of the Eastern colonies (D. gigas) 3 and are most in evidence at daybreak and sunset, when a family party, uttering their loud cackling notes, enlivens the silence of the bush. We waited at one pool until the moon was well up and succeeded in shooting a couple of ducks. Returning to the pool we halted at my friend's camp where he was engaged with a mate in sinking a well for the Roads Board, and I had my first bush supper of salt mutton, damper and tea. I recollect well the mutton contained numbers of the small red ants which make life so often miserable when camped out. Besides their bite, they possess a very pungent and disagreeable taste and smell.

3

~.

.. -

... _..

~ . ~ ..-.-~... , .... ~

- *

-

: . -.

...

"':---

.....

Baston's and Co., store owners and shipping agents, were the commercial heart of Carnarvon. A bullock team and wagon await a load for the long road south.

My two trunks had been landed at the end of a short jetty (Baston's) in front of the town, and lay there exposed to public view until I got someone to carry them to the Hotel. Inside one of them, on top of clothing etc., lay about three pounds of tobacco obtained on the steamer. I wondered if the Customs would search the luggage, but they did not trouble about it. At the end of three or four days we started out to Boolathana. Brockman and Mr. Foss drove in the former's buggy, and a son-in-law, C. Ridley, took turn about to ride a horse or go in the buggy. The road crossed the River (at an island) a little above where it divides into the two branches. A few months previously, a party of surveyors who were surveying the route of the telegraph line then being constructed to Derby in the North, were camped on the island when the River ran a banker. The party were obliged to take refuge in the gumtree branches, whence they were rescued by rowing boats after a very unpleasant night- only to find afterwards when the water subsided that a great deal of their stores and equipment was lost. The leader of this party, Price, was attacked a few miles from this spot by some of the Chinamen employed in clearing the scrub from the line of telegraph. They surrounded him armed with knives and tomahawks, but were so eager to kill him that they hindered one another. Joe Scott, a man employed as teamster for the survey party, ran to his tent, and returning with a rifle picked off four of Mr. Price's assailants, enabling him to escape although badly mauled and cut. The Government afterwards awarded £20 to Scott for his

4

Boolathana Station, near Carnarvon, was Tom Carter's first place of employment. He at first received no wages 'as was the custom'.

'

presence of mind and courage and he remarked he would willingly shoot every b----- Chinky in the country at the same terms. Just under the North bank of the River was a permanent pool of water known as Yanget Pool- from the bulrushes growing~-it, the native name the Mission then of which is yan get. On the bank above the Pool st recently started by the Revd Gribble for the natives; b . through ill-judged means and exaggerated reports he sent to newspapers etc., he was boycotted by the settlers, and had to leave Western Australia after losing a libel case concerning the Mission and its management. After leaving the River the road runs through typical North-West country - hard clay flats dotted with the low saltbush, cotton bush, blue bush etc., and in places rather thicker scrub growing to twelve or fifteen feet. Almost all the bushes are readily eaten by sheep or large stock, and are the main feed supply after the grass and annual herbage has dried off and been eaten down, or blown away by the winds. Low ranges of red sandhills occur at intervals, usually running from about South-West to North-East, the South-West wind being the prevailing one. There is no timber, excepting on the margins of pools, creeks and rivers, and that is almost entirely white gum. Claypans are a great feature of this district; they are almost perfectly level, of hard clay, often circular and of considerable area. After rains, they hold from two to six inches of water. We arrived at the Boolathana Station about sundown. It was a low, onestoreyed, stone house built by Charles Brockman, a pioneer of this district. The natives caused much trouble at that time and many white men were killed, some by having their heads cut off, or battered in with tomahawks as

5

Stockmen crossing the Gascoyne River.

they slept; others were speared. In many cases these outrages were unprovoked (except in so far as the pioneers were trespassers) and they led to rough retaliation in return. Naturally, the house was not built without intervals away looking after the sheep and stock. Returning to his masonry work after one such absence, Brockman found the natives had broken into the store room, looting precious rations. One of the ringleaders named Charlie - a young fellow afterwards notorious for many villainies - was attired in a white shirt and silk hat, and between intervals of playing a stolen accordion, harangued the admiring crowd of blacks, declaring he was 'Boss now'. This same native caused an excitement a few weeks after my arrival at Boolathana: he picked up a couple of baits (pieces of meat poisoned with strychnine and laid for the benefit of wild dogs or dingoes) out on the run and, arriving at the natives' camp near the house, presented them to his Father, an aged man, for his supper. Of course the poor old 'governor' was soon in violent convulsions, and messengers ran post-haste to the house for remedies. These were administered in the shape of chunks of black fig tobacco swallowed by the patient who, after vomiting several times, recovered. When the young would-be parricide was questioned as to his motive, he callously replied, 'He too much old beggar, what for him nothing dead'. just below Boolathana Station was a gully, apparently an old by-wash or side channel of the Gascoyne River. This had been dammed across close to the house and, throwing the water back, formed a splendid pool about two miles in length, a quarter of a mile wide and probably fifteen feet in depth

6

in places. Many ducks and wild fowl visited it. The morning after my arrival, I put together my 380 rifle and walked down to the pool for a trial shot. There were two cockatoos walking near the edge of the water and, waiting until they crossed one another, I fired and killed them both. On the far side of the pool from the homestead was a considerable thicket of wampoo and wattle bushes. A species of wallaby was abundant in it, and many times I shot four or six there within an hour or so, with the rifle. A couple of years afterwards, not one could be seen. I think sheep constantly feeding about drive away almost all the smaller bush fauna. After a few days I was driven about five miles out to Coorooboodgo, where an old shepherd, R. Shaw, was attending to some flocks of lambing ewes. Owing to the dry season feed was very scarce, and the unfortunate sheep and lambs were having a very bad time - as was also the shepherd. For the first time I now commenced to rough it. As the only object is to keep off the sun's rays, Shaw had a hut formed by bushes under the shade of a white gum. A native was told of to make a similar screen for me by cutting down the centre bushes in a thick patch. He carefully cut a large yellowish mass, the size of a man's head, from the top of one bush, and showed it to me after cautioning me not to touch it. It was the 'nest' of a colony of large hairy caterpillars; the slightest touch causes the hairs to stick in one's skin and bring on instant irritation lasting for some days. Any place where the caterpillars have crawled is full of shed A sta!ion homestead in the nor!h-wes!

7

hairs and if once they get into one's blanket, it may as well be burnt. After rain or before, these caterpillars hook on to one another, and form crawling strings composed of perhaps two hundred caterpillars, processionary. We were, of course, now on the regulation bush fare- damper, mutton and tea. Damper is made of flour (baking powder, soda or occasionally Eno's Fruit Salt being added to lighten it if one is luxuriously inclined) mixed with water which is gradually poured in the centre of the mass of flour. It is kneaded to the consistency of fairly stiff dough, and shaped into a round form. A bag laid on the ground (which is the usual thing on which to make damper) is sprinkled with dry flour and the round lump of dough placed on it and pressed out by the hands into a flat cake about two inches thick. The camp fire, which has previously been tended into a brisk blaze, now has the top part of unburnt sticks and coals put on one side. The heap of hot ashes beneath is carefully opened out in the centre until the opening will admit the unbaked damper, which is now dropped in, taking care that there is a layer of ashes between it and the ground. The ashes previously put on one side are now carefully raked evenly over the damper with a stick, and it is left to cook. Usually it will require to be opened out and turned over after about twenty minutes, according to the size of the bake, but if there is a good accumulation of ashes it will cook through without turning, and be better for it. After taking out of the fire, it only needs the fine wood ashes dusted or brushed from it with a bunch of leafy twigs, a bag, one's hat or saddle cloth - whichever happens to be nearest to hand. Good damper is very fair eating, and is much better to carry when travelling than bread, especially on horseback. It is best to keep a damper standing on its edge while it is hot, as otherwise it will go 'sad'. On a camp like this the man in charge kills his own mutton, keeping a portion - as much as he thinks will not go bad before he can eat it. This portion in summer is usually nil, as a sheep killed at sundown may be green next morning. The rest of the meat is salted and hung up in a bag to drip, and to keep the ants off it. Every bushman carries a quart pot which is placed on the fire at meal time; according to taste a pinch or handful of tea is added when the water boils, and the pannikin at once lifted off the fire. Sugar is added or not, according to individual taste, and the tea drunk without milk. If one has fresh meat, a few slices are cut off the joint and grilled on carefully selected and levelled hot coals, 'while the billy boils'. If one is in a regular camp, one may possess the luxury of a gridiron made of fencing wire, or even attain to the heights of frying in a frying pan or camp oven. These latter cannot be carried when one is travelling with one horse. The three flocks of sheep at the camp were shepherded by black shepherds - usually a man and his woman or gin. The woman usually does most of the shepherding, the man hunting for wallabies, rats and snakes and helping her to drive the sheep back to camp at night. The lambing ewes were, of course, in need of the greatest attention. Every morning, as soon as it was light enough to see, Shaw, myself and three or four natives went over to where they were camped and proceeded with great care to 'draw out' the lambs dropped the previous night, with their mothers. It was not always easy, as often the mother would prefer to keep with the flock and leave the lamb. Frequently the lamb would be left alone, and we

8

had to pick out the mother from the flock of about a thousand which were not in a yard but in the open, and moving about. When a ewe is about to lamb she usually tries to get to the outside of the flock, and it is much better not to yard them when lambing unless wild dogs are about. The day's 'drop' of lambs are put with their mothers in charge of a native - usually a woman, as being more reliable - and kept by themselves for two or three days; by then they should be fairly strong on their legs and fit to run with the older lambs. There is always, too, the mob of strong lambs which feed further away, so a man in charge of a lambing camp may have perhaps ten or twelve different lots of ewes and lambs to superintend, and to count at least twice daily; what with having to cook his meals and see that all the different lots are watered twice a day without getting 'boxed up' (i.e. mixed), he has enough to do. We had two wells at which to water the sheep, about a quarter of a mile apart. The wells were shallow, the water being only about six feet from the surface of the ground. Water is drawn by a long gum sapling (lever) working in the fork of a large limb set upright in the ground. The bucket hangs by a rope or a long, thin stick at the small end of the lever, and the other end of the lever has a weight attached, heavy enough to raise the bucket out of the well (after it has been dipped full of water) just high enough to allow of the water being tipped out into the long length of troughing. With the exception of having to pull down the lever-end by the rope until the bucket reaches the water in the well, there is little exertion in drawing the water. The principle Shearing time a! a nonh-wes! srarion

9

is that of the oriental shadoof, used for irrigation. The troughs are made of white gum trees, hollowed out and put end to end. A ewe with lamb at foot, living on dry feed, will easily drink two gallons of water when brought to the trough. After a short time the mobs of sheep, by travelling in and out between camp and the wells, destroyed all the dry grass and herbage around, and lambs began to die and ewes to forsake their lambs; we had to cut down some of the edible bushes so that the starving sheep could eat the top leaves. By dragging the bushes into position, we made small yards to hold a few ewes and their lambs, but soon these means failed and we had to kill the lambs as soon as they were born, and bum them in heaps, as the ewes got too weak to be able to rear them; it was better to sacrifice the lambs than to lose both ewes and lambs. Numbers of the great wedge-tailed eagles (the eagle-hawks of the colonists) 4 also appeared and killed, especially, numbers of lambs, and to get rid of them we poisoned the carcases of dead lambs with strychnine. One day I was hidden under a bush, watching a poisoned carcase with many eagles feeding from it. Before long, five of them began to show effects of the poison in their drooping wings and staggering gait. Two of them flapped to a lower limb of a white gum tree, and after much wobbling, fell to the ground. I then came up and, wishing to make skins of some, selected two of the finest of the (apparently) dead birds; grasping their legs above their formidable talons, I slung them over my shoulder and started back to the camp. I had not gone far, however, before one of the birds began to struggle and work its claws, which did no harm, but when its beak began to work on my rear I thought it time to drop the bird and kill it outright, before proceeding further. I may here mention that three or four years previously Brockman had started out with another man, Lowe, to examine the country further North. They failed to find water at Yalobia- having a bad native for guide- and reached the Minilya River, eighty miles North of the Gascoyne, without getting any water on the way; they also failed to find any water or any of the good pools near where the Minilya Station was afterwards built. After looking around, Lowe went mad and, taking the horses with him, left Brockman. The man never returned, and after waiting a few days at a very small 'dub' of muddy water that he found, Brockman decided to attempt to return alone. Shooting an emu with his revolver, he cut off a supply of meat and started back South, there being no road of any description. How long his walk lasted he never knew, but he eventually landed up- crawling on hands and knees - at the Coorooboodgo well, where we now had our camp. A man called Charles Wheelock happened to be there; he would not allow Brockman to drink his fill (which would probably have proved fatal}, but laid him in the trough and let his skin soak in water until his dreadful thirst was somewhat assuaged. I have heard the story from Brockman himself, who related how he travelled mostly by night to avoid the heat and how, in the latter stages of exhaustion he was tantalized - but yet urged to further efforts by visions of running brooks, and dainty feasts just beyond them. The following day John Brockman got horses and returned to Minilya to find Lowe; though the horses died of thirst and were never seen again, the dead body of Lowe was found near the River about twenty-five miles above the Station site.

10

The most noticeable bird at Coorooboodgo was a honeyeater, afterwards described as a new species, Ptilotis carteri 5 ; its lively notes were heard at first daybreak. White cockatoos were also numerous, and the pretty, crested bronzewing pigeons6 used to visit the troughs in numbers for water. After some weeks there we had visitors in the shape of teams calling, as the Carbadia well, a few miles away on the Minilya road, had gone salt. On one occasion I walked in to Boolathana Station, carrying my two eagles' skins as I feared some of the skin beetles (Dermis) would get into them if they lay about in the open. The hairy grubs of this beetle are very destructive to sheepskins, or any other specimens. Arriving at the Station I found no one there except an old American black, Fisher, who had been a slave, then a sailor and a whaler, and subsequently had 'done time' for bushranging in the Eastern colonies. The old villain declared he had nothing to cook except bread and tea, upon which he fed me, though I afterwards found out he was eating poultry and eggs himself. Next day on awakening I found I had a bad attack of ophthalmia (sandy blight of the colonists) and could not bear any light- not even the striking of a match to have a smoke - and had to lie in a darkened room for two days until Brockman returned from Port and put my eyes right with eye water. No one accustomed to living in the bush travels without this, as one is liable at any time to get the 'blight' either from flies, or dust, or intense heat radiated from the ground. Unless prompt measures are taken permanent injury to the eyesight- or even blindness- will result; I knew several cases of the sight of one eye being lost, and one case of total blindness. Retribution overtook this black cook very shortly afterwards. He was acting cook on the Gascoyne River at one of Mr. R. E. Bush's stations and apparently died in a fit, as the mailman calling there found him lying outside, with the fowls eating the maggots off what was left of his body. I stayed a week or two at the house until my eyes were strong again. Meanwhile, as the lambing at Coorooboodgo was over, Bob Shaw went to Port where, as was usual in such cases, he had a wild bout of drinking and was found there and driven out by Brockman's brother Ned. Shaw was in the habit of carrying his bottle of strychnine for dogs, etc. in his trouser pocket and on the way out, when he wanted to smoke, he found his pipe was in the same pocket as the poison. Not knowing the cork had come out of the bottle, he filled his pipe and tried to smoke, but after several attempts discovered the stem of the pipe was blocked by grains of strychnine. The shock somewhat sobered him, but no ill results followed. He passed the night at the Station but next morning was missing, which caused alarm, as from his manner we had imagined he was beginning to show delirium tremens (jimjams). Not knowing what might have happened to him, ]. Brockman drove out with a blackfellow and followed his tracks which led them to his old camp at Coorooboodgo. Brockman stayed with him for a day or two but became alarmed as Shaw had a grudge against him and began to threaten him. (Shaw, in a former similar bout at Port, had cut his own throat - nearly cutting the windpipe - and then charged another man with doing it.) Brockman became rather nervous, and drove in to ask if I would go out and stay with Shaw! This I consented to do; as I had previously made a great impression on him

11

by offering him the loan of my netted hammock to sleep on as he had bad rheumatism and sciatica, I hardly thought he would injure me. Accordingly, Brockman drove me out with half a bottle of whisky which I had strict orders to dole out to Shaw (a nip only, night and morning) to 'straighten' him up: a case of 'the dog that bit him'. Shaw insisted on my having a nip with him that night, and I well remember that one of the large, savage bulldog or sergeant ants chanced to have got into the pannikin and gave me a very severe bite in the mouth - my first. Shaw was very queer next day, and when the natives came for their meals, insisted in wrapping up each one's portion in paper and tying it round with string. At night I heard him talking much to himself, and before lying down on his blanket he arranged an axe, tomahawk, pickaxe and loaded gun at his head in case, as he said, Brockman or anyone else came up at night. After he had turned in, I slept some little distance away from him. Next morning he insisted on my writing down a statement full of the most outrageous stories respecting people who, he said, had been at his camp that night. A team called the next day, driven by G. J. Grierson; after seeing Shaw, Grierson called me to one side and asked me if I knew Shaw was stark mad. I said I was quite aware of it, but did not think he would harm me. Grierson said he would not camp with him for any sum of money, and left. However, Shaw was all right again within a week. Soon after this little episode Grierson called again. He took me out with him about a mile higher up the gully or creek where we camped at a spot where he had a contract to sink a well at a 'soak' - in the banks where the natives used to get water. The two wells at Coorooboodgo had begun to fail a little: all the sheep watering there, and the teams carting water away for the long waterless stage on the Minilya road (sixty miles), was a great strain, and Brockman began to be afraid they might fail altogether. So we started to sink a hole about five feet by four feet in the bed of the creek, just opposite the natives 'soak'. ('Soak' is a term used to indicate where water occurs but not permanently in any great quantity.) After sinking about three feet the water came in fast, necessitating constant baling, and we had to erect a lever and fork to keep it down so that the pick and shovel could keep working. We then made the 'box'- formed of four strong corner pieces of timber with side planks of six inches by one inch nailed on- and lowered it down the hole. The man inside kept excavating, and as he cleared away the earth from the under edges of the box, it gradually sank. That night we turned in feeling confident there would be a good supply of water, but next morning, after baling out all the water accumulated during the night hours we found that no more came in as the supply was exhausted. So we laboriously levered and parbuckled the heavy box out again to save the timber, packed up, and returned to the Coorooboodgo camp. I found this well-sinking was done on Easter Sunday- 'no Sunday in the bush'. Soon after this a light thunder shower fell, and Shaw took a flock of sheep to a claypan about two miles distant that had collected a little water. The sheep refused to drink the water in it - which was muddy as usual - being used to the clear water from the wells, and he had to bring them back. Sheep are often very dainty about water; if taken from clear water to muddy they will refuse to drink it, even, at times, vice versa.

12

A north-wesrem riveT during the dry season.

As the feed around Coorooboodgo camp was now finished and a great proportion of the edible bushes had been cut down, Shaw decided to ease the wells by sending one flock of about a thousand to Yandoo well, about two miles higher up the creek from where we were camped. A native (Neddy) and his woman (Badja) were to be the shepherds; a few 'loose' natives (not employed) having turned up, they were persuaded to carry my few belongings and rations to the new camp for a stick or two of tobacco and some tucker. Thus, for the first time, I was quite 'on my own'. On arriving at the well I found the water was about sixty feet from the surface, and had to be drawn up in a ten gallon drum by a windlass with handle at each end. My belongings were placed under the shade of a large white gum about one hundred yards from the well. They consisted of: a small leather valise with a few spare shirts, socks and pair of pants; a blanket; a doublebarrelled gun brought from home; and spare pairs of boots. My stores and cooking gear consisted of: my own tin pannikin (or 'quart pot' as it holds a quart); the usual quantity of tea (drunk at each meal); a bag containing a little salt mutton; another bag with some flour and a small amount of tea, sugar and tobacco; an empty flour bag on which to mix up my damper; and an old bucket in which to boil my salt mutton. It is surprising, at first, to find out what a lot of things one can do without when one has to, and how civilization entails the use of many superfluities. Like all bushmen I carried a sheath knife on my belt, from which also hung a leather pouch to hold my day's store of tobacco, matches, my pipe and a pocket knife with which to cut up the hard, black figs of tobacco for the pipe;

13

another small pouch on the belt holds one's watch. Regular clothing is a pair of light boots, socks (or not, according to taste), a pair of white cotton moleskin trousers and flannel or cotton shirt - the former is much the best - and a broad-brimmed, soft, felt hat. I also owned the luxury of a netted hammock brought from home. This was the cause of much scoffing among the regular hands as being a very superfluous comfort, but I hung it from a lower limb of the tree and found it useful to keep my little stock of things in (as ants did not readily get on it), and afterwards, as will be related, useful to sleep in. The troughing at Yandoo well was not long enough to meet the requirements of a thousand sheep, being about forty feet instead of a hundred feet in length. When a mob of sheep comes in for their daily drink, the first lot to line the troughs will finish all the water already drawn beforehand. The other sheep, crowding and jostling behind them, prevent the first lot backing out and getting away when they have drunk their fill. When they do get out and leave room for a few of the second lot to get in, the troughs are dry, and only a fortunate few nearest the well (where the water is poured into the troughs from the bucket) have a chance of getting a decent drink; those at the far end of the troughs find no water gets down there at all. If no more troughs can be obtained at the Station, the way to remedy this is to stop the flock of sheep some distance from the well, and let only two or three hundred come in at one time and drink their fill. When they are satisfied ('choked off'), one then 'cooees', or shouts to natives left with the main flock, and they cut off another mob of sheep to come in to drink until all are satisfied. This method is better for the sheep and means less work for those drawing water. When sheep only get a sip now and again, they never seem to be satisfied, and there is always a cloud of choking dust stirred up all round. Many sheep in the jostling, frantic crowd go down and are trampled under, and they smother very quickly unless got up and carried out into the open. One person really is required to walk up and down the troughs among the struggling sheep to keep them in some degree straight, and to allow those who have been drinking to get out. They at once seek the nearest shade of tree or bush and lie down (lay up, colonial) until about 4 p.m. when it is cooler, and they are driven away by shepherds to feed until sundown. Long lengths of troughing prevent this, and when sheep are loose in paddocks (instead of being shepherded) they come in themselves in small mobs. Many sheep always drink at the same part of the troughing every time they come in, and until they can get in to drink at that one particular spot, refuse to drink. In the same way, sheep in a driven flock usually have their own places, in front or rear, right or left flank etc. To one unversed, all sheep seem much alike, but a good man (shepherd) gets to know by sight an amazing proportion of the individual sheep in his flock. Before I had been many days at Yandoo well, I discovered that the supply of water in the well was not good, that is, it did not flow in rapidly to replace that drawn out for sheep. The depth of water in the well was about seventeen feet, and after watering the thousand sheep there was very little left. The native and I used to fill the troughs every evening ready for next day, but although the troughs did not leak to any extent, they were always empty next

14

morning- which meant extra work filling them again. The native was the first to discover that a mob of horses running in the bush used to come in at night and drink the water we had laboriously drawn up, so we decided to fill the troughs early in the morning when one could watch that the horses did not drink the water, or 'swamp it' (colonial), before the sheep came in. The second night after this decision I had a scare: I was sound asleep on my usual bed- 'the big floor with the blue curtains' (i.e. the bare ground) - when an unusual sound woke me with a start. I saw myself surrounded by large forms of some sort, and something that I imagined was a wild black was stooping over me almost touching my chest. As I jumped to my feet the forms around me scattered with a great noise, and in a few moments I realised that the mob of horses had come to the well and, apparently finding no water, had come to me, and one had his nose almost touching me as I lay asleep. I had put two sheepskins on the ground under my blankets as I thought they would tend to soften the bumps a little: this was the means of my receiving another scare. I was roughly awakened one night by something actually jumping on my chest, and staying there. I grabbed as many of its legs as I could from under the blanket and, getting my head clear, found I had caught a fair-sized lamb - not a native dog as I had imagined. The lamb had lost its mother and the flock, and being attracted by the smell of the sheepskins, had evidently smelt about and then jumped onto me. Another night I was severely bitten by a large centipede in two places near my right elbow, and my arm swelled badly and was very painful for some time. I shall have the marks of the bites as long as I live. Shaw got his stores from the station, and was supposed to supply me with the same flour, sugar and tea as they had at the station. However, he sent me a little rice in place of the flour, which was sheer laziness as the station was only seventeen miles from Port. I was supposed to kill my own sheep for myself and the native shepherds but, as no salt had been sent out, it was useless killing as only a quarter could be eaten before the rest went bad. This I found out after killing a couple of wethers, and for some days the only meat I had was the parrots or cockatoos that fell to my gun. All this time I had had no letters or news from home, as all of them had been directed to the base where I had originally landed. Brockman had promised to bring them right out to me as soon as they came, and day after day after my work was done, I would walk down the track which led to the Station, hoping to see the dust announcing the approach of the Station buggy; but no letters came until I had been in the bush for about three months, and then they were casually sent out to Shaw's camp by a passing team. How I enjoyed them when I got them! On my first arrival at Yandoo there was a small pool of muddy water about one quarter of a mile from the well, left from the thunder shower previously mentioned. It was too muddy even for the sheep, and emus used to water at it - but I had not enough bush lore to succeed in shooting one, as it is necessary to make a bush screen near the pool and be absolutely invisible, or they will not approach within sight. After working a while at this well, the man shepherd Neddy concluded water-drawing was hard work (it was!) and, telling his woman to stop with the sheep, went in to Carnarvon for a holiday. Luckily, J. Grierson, who was

15

sinking a well at Cooralya for R. Cleveland some miles beyond Yandoo, called with his team. He knew I could not draw the water single-handed, as one man must hold the windlass steady when the bucket arrived at the top, while another (myself) landed the bucket onto the edge of the well, ready for emptying into the tr.oughs, and he told his native- a lazy old villain- to stay and help me until someone was sent out to me from Boolathana where he was calling. I had noticed for some days that the water was acquiring an increasingly rank taste and smell, and next morning a sheep's ear and part of a scalp came up in a bucket; I thought it time to get out the putrefying carcase (which I could see floating in the water below) before it burst and sank in the well. Accordingly, I told the native to get into the bucket and I would lower him down, but he steadfastly refused to do anything of the sort. As I would not trust him to lower me single-handed, I got a light line from Grierson's cart which he had left at the well and, making a noose at one end, lowered it down the well, making the other end fast above. Then I let out all the rope off the windlass and went down it, hand over hand. The first part was all right as the well was timbered some fifteen feet from the top and I could get toehold between the timbers, but when I got below the timbers where the sides of the well were smooth greasy sandstone, I wondered if I could manage to climb up the rope again without any assistance from foothold on the sides. However, I wanted that sheep out of my only drinking water, and I went down, got the noose at the end of the light line round the carcase, and shouted to the native to haul it up. This he did - the foul drippings falling all over me until he got it to the top. Then I went up, hand over hand, and was almost exhausted on reaching the top again. Two days after, the same rope broke when lowering the empty drum, so I had to send Grierson's native straight in to the station for new rope and a bucket. Grierson sent out two five gallon drums and a strong, willing native (Shark Bay Billy), who was a great improvement on the two previous natives. The two five gallon drums, being fixed one at each end of the windlass rope, made much easier work as the empty bucket going down helped materially to pull up the full one. Billy borrowed my gun one day and shot a fine emu at the little pool of muddy water and, to my surprise, quite a number of natives (of whose neighbourhood I was unaware) turned up to help eat it. One morning, while I was having my solitary and meagre breakfast, two gaunt dingoes (wild dogs) trotted up and calmly sat down about fifty yards away from me, surveying the scene; but when I moved to reach for my gun they rapidly cleared out. At last, after many weary weeks, a local thunderstorm brewed up and we had a heavy shower of rain. As the bulk of it apparently fell a little distance East of Yandoo, Shaw sent a native out on horse to report. He returned saying the rain had been heavy, filling the clayholes and claypans for some distance, and making a small gully run; but a mile away not a drop of rain had fallen. Shaw immediately started to move all sheep towards the water. None of the surrounding country had the boundaries of the various blocks of leasehold land surveyed and this particular portion was claimed both by Boolathana Station

16

and by its neighbour, Brick House Station. In this case the Boolathana sheep arrived first, and stopped there, but when the land was surveyed some time after, this portion was decided to be on Brick House run. All land in this district, and the North-West proper, was leased from the Government for twenty-one years. The smallest block allowed to be taken up was 20,000 acres, and the rent was 10/- a thousand acres per annum for the first seven years of the lease, 12/6d for the second seven years, and 15/for the third, with an option of renewing the lease. After the heavy losses sustained by squatters in the drought of 1889, 1890 and 1891 (the first experienced in Western Australia), the Government agreed to allow the rent to remain at 10/- until the termination of the leases which all expired in 1907. In order to form an average sized station one required from 200,000 to 500,000 acres, and as the maximum number of sheep that could be safely run on land there was roughly one sheep to ten acres, these were just nice comfortable runs. This seems to speak badly for the land, but it was not the fault of the land, or feed grown, but the irregularity of the rainfall which was quite uncertain; twelve months without rain being nothing unusual - only a dry season, not a drought. After winter rains, a dense growth of annual herbs, grass, everlastings, vetches etc., all of splendid fattening qualities, grew rapidly to the height of six or ten inches; on hot weather setting in they rapidly withered, breaking off with the wind and disappearing in a marvellous manner. These annuals never shot (i.e. the seeds did not germinate) no matter how much rain fell in the summer, which seems remarkable. The summer rains Country near Carnarvon three months after a drought, with abundant growth.

17

(thunderstorms) caused the permanent-rooted grasses to grow at a wonderful pace, and they did not blow away with the wind like the annuals. These permanent grasses did not grow nearly so tall, or as quickly, with the winter rains, both air and ground being then comparatively cold. It did not take us very long to get all the sheep and our gear moved to where the shower had been. Oh! What a treat it was to smell damp earth and see bright green vegetation springing up like magic and little pools and dubs of water all round - how different from the blinding hot glare from the previous bare, dusty, red-hot ground! Birds of all sorts appeared at once, and were in full song and building their nests within a few days. This appears to be a very wise provision of nature, instinct or intelligence, on the part of the birds, as the majority of small birds breed only after rain when a plentiful supply of food is assured for their young. Emus also follow this rule in a great measure, and in dry seasons apparently do not lay at all. Eagles, hawks, cockatoos and parrots have a more regular laying season, to which they adhere irrespective of seasons; the warbling grass parakeet 7 breeds any time of the year after rain. Our new camp was quite luxurious with plenty of green feed for the surviving ewes and lambs and no water to draw. The thing we, especially Shaw, felt most was that we were still without any sugar, but after a week a supply reached us and the old man at once sat down by the bag and ate sugar in handfuls until he was satiated. It seemed to me the amount of sugar (usually a handful) that is generally put in the quart pot of tea at each meal and the frequent A beautiful pool

18

at

WiUiamsbury Station is enjoyed lry

two

visitors.

extra quarts drunk between meals in hot weather or after an unusually dusty spell of work, was the source whence we derived most of our support and nutriment, as there is not much in damper and salt meat. As there was really no actual work to be done, I put in a good part of my time walking round with my gun, procuring a few skins and eggs. One day Shaw sent me, with a native to show the way, about seven miles over to a large pool, Tirigie, which he thought might now hold water, but we found it dry and no water on the way, and arrived back at the camp very thirsty. A good many bush natives now camped with our native shepherds and, as usual, owned a number of mongrel dogs, many of them a cross with dingoes, which cross is more prone to worry and chase sheep than even the dingo itself. So we planned a raid on them one moonlight night. Shaw took my doublebarrelled 12 inch gun and I had my 450 Colt revolver. There was great excitement at the camp when we arrived and began to drop the dogs. Shaw got three, and I got five out of my six shots, which was a good night's shooting. We kept watch at our camp the rest of the night as the blacks were very cross, and threatened to spear us. They would sooner lose their babies than their dogs; when blacks are travelling and the women run short of water and are carrying infants, they will sacrifice the children before the dogs. They argue the dogs catch game and act as sentinels, whereas infants are only an encumbrance. We had not been at this camp very long when I received orders from &olathana to bring one flock in to the Station, which I did with two black shepherds. We camped on the road one night, and the only incident of note was an exciting hunt of a large, poisonous snake by the black shepherd. He eventually speared it in some scrub, after it had turned and attacked him several times. When we arrived at the house we found no rain had fallen there. Clarence Spencer, Mrs. Gale's brother, had recently arrived from the South-West to learn the management of sheep, and we started off to the coast to Beejaling (about 20 miles West) where Neddy Brockman was camped with two flocks of later-lambing ewes. It was late before we left the house, and most of the way traversed in the dark. A vast area of salt marsh extends from the North bank of the Gascoyne River, not far from the sea, up to Cape Farquhar, about ninety miles North. It is mostly level and bare, with a hard baked crust a few inches thick covering unknown depths of salt mud ooze. In places the marsh is twenty or more miles in width; at any rate it is so wide one cannot see across it, even from the summit of considerable hills. A great part of it is absolute ooze, or quicksand, and quite impassable even for dogs, as once anything gets down into the tenacious mud it cannot get out again. The natives are much afraid of venturing on any part that is not known to be hard, and declare huge snakes or monsters inhabit the mud, seize one's legs and drag one down. It is dangerous to take horses over even the hardest parts until constant traffic has beaten the crust into a compact mass, and even then it may break through at any time. When the Minilya and Lyndon Rivers are in flood, they empty on the North end of this vast marsh and not in the sea, and the whole of the marsh is a vast impassable lake, or swamp. The large majority of 'lakes', as marked on

19

maps in the interior of Australia, consist of these treacherous salt marshes, such as Lake Wey in Western Australia, Lake Eyre in South Australia etc. Wonderful mirages of green trees, islands and landscapes are almost always to be seen on them unless the sun is not shining, which rarely happens. We safely crossed the narrow arms of the marsh on the track to Beejaling with a native guiding us, and after a light supper at the small corrugated iron hut in which Neddy Brockman was camped, turned in. Next morning I was up early and went down to the beach, a hundred yards away. It was a beautiful clear sea with surf breaking on the beach, and on the reefs further out to sea. High, steep sandhills up to one hundred feet in height extended as far as one could see North and South, formed of very white fine sand with patches of thick, bright green scrub, very stiff and matted in growth. Just opposite the camp was a vast expanse of absolutely bare white sand, sand drift, and at the foot of it near the sea was Beejaling well, which held a magnificent supply of good water about three feet from the surface. These sand drifts (which occur at intervals along a great portion of the West and South coasts of Australia) almost always indicate a supply of good water of shallow depth, usually on the sea side of the drift and frequently within one hundred yards of the sea. Many unfortunate persons, especially shipwrecked seamen unused to the country, have lost their lives from thirst when they have been actually walking over good water hidden below the barren-looking white sand. We found this clean white sand was good for cooking damper; if a large fire was made on the surface, the sand beneath became hot enough to cook a damper buried in it, without waiting for the usual accumulation of ashes to form. The dampers so cooked were not burnt or charred, and required little cleaning after taking out; certainly a fair proportion of sand adhered to the outside but, according to many medical experts, we should all eat a certain amount of fine grit to aid digestion. All along these coast hills grew great bunches of the succulent milk bush, one of the most valuable and fattening fodder plants that grow in Australia. It grows very locally, usually near the coast, and being entirely composed of leafless green stalks growing as thickly as possible and full of a thick, white, intensely bitter juice which oozes out freely as soon as stock bite off the ends, it very soon 'bleeds' its strength away if eaten of much, and becomes a heap of withered stalks which never shoot again. Sheep and bullocks eat it greedily and do not require water when feeding on it, but horses refuse it absolutely. It is an invaluable standby for dry seasons, but as sheep will not leave off eating it as long as any part remains green, it has no chance of growing, and rapidly dies off and disappears as soon as the country is regularly stocked. The sheep at Beejaling had been sent there to recuperate on the luscious milk bush which causes ewes to have a good supply of milk, among other good qualities. Sheep shepherded on milk bush will not leave it, or wander away any distance, and give the shepherds absolutely no trouble - if put on it, 'dog poor' will be fat within a month. The morning after arrival some trouble was caused by almost all the lambing ewes (which were camped at night in the open near the well) having 'drawn off', or gone away, during the night. As it happened to be a 'heavy drop' night, about ninety newly-hom lambs were left motherless at the camp, but

20

the natives rounded up the flock and brought them back, and before noon we had almost all the lambs mothered. A day or two afterwards Spencer and myself started off with a mob of strong lambs and ewes to camp at Cooranderra well, a few miles North of Beejaling. We had a light spring dray with two horses to carry camp gear, tools, troughs, etc. and left towards evening, the cart travelling along the beach to avoid the heavy going through the sandhills where there was no track. The rising tide forced the cart to keep up near the high tide mark where the sand is dry and the going heavy, so slow progress was made and dark set in long before we were near the well. The beach turning into rough rock and boulders, we were obliged to leave it altogether. We somehow managed to get the cart over the first row of sandhills without capsizing, with both of us having to pull hard on the top rail of the cart on the high side to keep it from rolling over and over down the beach again. When we revisited the place again next morning we wondered how we had safely got up without any accident- it was a place no sane driver would think of attempting in daylight. Guided by our native we soon after reached the well, and found it was made of sheets of corrugated iron put down perpendicularly and was consequently only two feet square and of unknown depth. However, we badly needed a drink, and I volunteered to go down the well with an old kettle we had to get water. As soon as I got inside with my feet on the pieces of wood that acted as braces to the comer timbers, these pieces of wood collapsed, having been destroyed by white ants, and I fell to the bottom (fortunately only ten or twelve feet distant and covered by a few inches of water). Next morning we proceeded to clean out the well, fix the trough we had brought with which to water the two horses, and form our camp. The sheep were to go without water and depend entirely on the milk bush - there would not have been nearly enough water in the well to water fifty sheep had they required it. There was little to do at this camp, and I spent a good deal of time fishing off the ledges of rocks on the beach which ran out into deep water: with a native woman's wana or six-foot fighting 'quarter staff' for a rod, a short line and piece of land crab or dead lamb for bait, I had very good sport, a species of rock cod averaging three to five pounds being readily caught with other species. One day while fishing I observed a large, yellowish animal, about seven feet in length and shaped somewhat like a thickset seal, swimming and playing near the shore, attended by a young one about three feet in length which at times suckled the mother. The animal was quite strange to me, and having my 450 revolver I fired two or three shots into it and it sank, apparently dead, much blood coming from it. On my return to camp I found Neddy Brockman, and on my describing the animal, he at once said it was a dugong. When the natives were told they became wildly excited, and all those not working at the time ran wildly down to the beach about half a mile distant, but they failed to find the dead body as the water went down to a considerable depth sheer off the rocky ledges. The dugong which inhabits the Indian Ocean is much valued as food both by natives and white settlers, as large masses of good, coarse meat resembling beef can be cut from it between the ribs and tail, without any bone. The meat covering the ribs is streaked fat and lean, and when well-cured is equal to

21

prime bacon. The oil obtained from the fat is tasteless and odourless, very good for frying in cooking or pastry, and also is reputed to be more efficacious than cod liver oil in pulmonary affections, and much more pleasant to take. The bull dugong weighs twelve hundredweight or more, and possesses two tusks of ivory, about nine or ten inches in length. The meat from the males is coarser than that from the females, the latter being from six to seven feet in length and weighing from four to six hundredweight. They1ive on various species of seaweed, especially a bright green variety with rounded leaf growing on the ocean bed, but I shall have more to say of these shy and inoffensive mammals when writing of my time at Point Cloates. As usual, we ran out of sugar, and I walked down to Beejaling one day to see if Neddy Brockman could spare us a few pounds, which he did - three pounds. When walking back along the beach the first heavy winter shower came on, and although I stuffed the sugar in the breast of my shirt, it was very syrupy on arrival at camp. I well remember this occurred on the 22nd June, Jubilee Day. I may not have made it very plain, but Beejaling and our camp lay on the strip of coastal sandhills between the salt marsh and beach. This land extended right through to Cape Farquhar, and at that time was almost unknown. I believe the only man who had travelled right through was Charles Brockman, who nearly lost his life and suffered much through want of water, although he was accompanied by a native. There was no sand water between Cooranderra and Boolbardi, North of Cape Farquhar, and the heavy sand, high hills and scrub made travelling difficult. One of his horses died and, when apparently in sight of Yalobia Hill below which was a good supply of water, Brockman retraced his steps. Natives did not camp on this strip of coast except after heavy rains when they get a supply of water for a few weeks out of cavities in the rocks filled by rain. Police Constable W. Turner was, I believe, the second man to go through here when searching for traces of a schooner supposed to have been wrecked in 1888. About 1903 C. Fane got water by sinking a well through rock, and the country was stocked with sheep. Leiopa Leiopa ocellata ('mallee hen' of the colonists, ngow of the Aborigines) used to breed near Beejaling, and also in quantities near Cape Farquhar according to the natives. A full account of their wonderful egg mounds will be given further on. One day while out I picked up a boobook owl (Ninox novae~ee/andiae), whose head, lying near the body, had apparently been struck off by a falcon or a hawk. There being no timber along the coast, the wedge-tailed eagles had to build their nests on the summits of high bushes. I found one such large structure about eight feet from the ground, but the natives got the eggs before me; two is the usual clutch. Emus also resorted to the smaller 'islands' on the marsh to lay, and the natives took several clutches of eggs in May. One night, after Spencer and I had turned in, we were aroused by great shouting and excitement at our native shepherds' camp a short distance away. On walking over, we found the woman holding their mongrel dog in her arms, and crying bitterly; it expired as soon as we arrived. It appeared a large snake had come up to the camp fire, bitten the dog and then disappeared down a hole in the ground near the man's head.

22

He endeavoured to dig it out, but lost the run of the hole and, of course, the snake. These natives camp and sleep behind the shelter of a semi-circular wall of broken bushes about two feet in height which serves simply to shelter them from the wind; the bushes are moved if the wind alters, so that the natives, and the main fire, are always on the lee side of the bushes. They generally keep two or liluee smaller fires in front of their bodies and behind their backs if the nights are cold, as they often are in the winter. The sand where their bodies repose is dug out and thrown outwards to the inside of the bushes, forming a ridge about six or ten inches in height, which serves them as a pillow. No matter how strong a wind is blowing, perfect shelter is formed for anyone lying down by these primitive means. After two or three weeks at this camp, Neddy Brockman decided our sheep were beginning to want water. Showers of rain had now fallen at the station and telling us to bring our sheep back to Beejaling, preparatory to returning to Boolathana, he started away from there with his flocks. There was no mistake about the sheep wanting water and I went on ahead and filled the troughs ready for the arrival. The shepherds let the whole flock 'string in' when the rear of the flock was still some distance away. The consequence was that they drank all the water in the troughs, began to crowd, and some of the weak ones were going down and starting to smother. I had to leave the waterdrawing to try and extricate the fallen sheep and, while I was doing so, the flock became so frantic that through an awkward bump I fell myself, and got below the struggling thirst-maddened sheep. It was with the greatest difficulty I got out again, and might have fared badly if the old shepherd had not come in and managed to drive away a part of the flock. Several sheep were dead when we eventually got them out of the muck. We found there had been a sad mishap at Beejaling. Neddy Brockman had a fine cart mare there for drawing the spring cart. She was hobbled, as usual, and had a yearling foal running with her. Apparently she had started to return to the Station and tried to cross the marsh off the regularly-used small, beaten track. The treacherous crust broke under the weight, and the native sent out next morning to bring her in found her buried in the horrible ooze up to her withers; all our attempts to extricate her failed, so a bullet ended her struggles. The foal, which had been standing near her, was with great difficulty driven away from its dead mother. One day, some of the young native boys at the camp had conceived the bright idea of riding races on a few rams, and one boy who fell off his steed had most of his front teeth knocked out when the ram put its foot in his mouth as it passed over him. Charles Spencer now started in to the Station, leaving me to bring back the sole remaining flock of sheep now left at Beejaling. An old pony, Chubby, the regular knockabout station hack, was left for me to ride, and to carry my blanket etc. As ~sua!, the flock of sheep got away at daylight, and I followed a short distance behind leading my pony, as he had a good load of one thing and another. The sheep ran gaily across an arm of the marsh about a quarter of

23

a mile wide; I followed what seemed an old foot pad, thinking it would be safe as I could see old horses' footprints on it, but about halfway across I saw where a previous horse had broken through the surface, and unfortunately I turned off the track. The next moment poor old Chubby broke through and went down to his saddle flaps. I relieved him of his load and saddle as quickly as possible, meanwhile cooeeing loudly to the natives for help. Some of them came back a little and then, seeing the state of affairs, sat down and began crying and howling, throwing handfuls of sand over themselves (a sign of lamentation), and begging me to come away at once before the monster living underneath pulled me down too. By this time the hole in the marsh was enlarging with the horse plunging and breaking down more crust with his forefeet, and I went thigh-deep in the mud below, dropping the horse's bridle. I managed to get out and, running across to the natives, succeeded in persuading two of the men to break off some armfuls of thick, scrubby samphire bush which always grows near the edge of marshes. Returning with them we got some of the bush under the pony's feet, and after much plunging he got out on the harder crust (which luckily supported him), trembling violently and coated with sticky salt mud - as were my legs too. I was careful to keep to the old track for the rest of the way, and very glad to be clear of the last piece of marsh. Had Chubby been a heavy horse he would have followed the fate of the mare, whose remains were in sight some little distance away. We arrived at Boolathana the next day to find the country beginning to look green with grass and weeds growing after the showers. All the claypans and crab holes held water, so there was no more water-drawing until the next summer set in. I used to carry out rations for the shepherds and still being somewhat of a New Chum, I did not always find it very easy to follow up the tracks of the flock that had gone out from a camp to feed that morning - perhaps two or three miles away in the thickets etc. - as the whole ground was a labyrinth of sheep footprints and tracks. It was necessary to deliver the rations into the hands of the shepherds themselves, as passing natives might get them if left at their camp. One two or three occasions I came across the flock scattered about feeding, but could not see the shepherds, and cooeed without avail until I discovered they were purposely hiding to see if I could find them. I soon put a stop to this little form of joke by taking their rations back again, and the man shepherd came in one night very indignant because that 'fool New Chum no find me'. From then on, however, the shepherds would be seated on the top of a prominent sandhill to catch my eye. The regulation week's ration was one and a half pounds of flour, one and a half pounds of meat, a quarter ounce of tea, a quarter ounce of tobacco and two ounces of sugar per day for each, the tobacco being optional. The natives almost invariably ate the whole of the week's supply within one or two days of receiving it, and then depended on what game the men could spear or secure, or the berries and roots etc. gathered by the women. If any other natives were near, it was a point of honour to invite them to help finish up the rations 'quick fellow'. Owing to the rain there was not much work to be done, and I had a good deal of spare time which I employed in bird's-nesting. Hawks were very common, especially the brown hawk8 which is of a tame sluggish nature and feeds

24

largely on lizards. The native name is kerra-jinga, probably derived from its loud querulous cry frequenrly urrered while on the wing ( rwo birds or often more circling round and round each other at a great elevation, crying out all the time) and also at sundown when a pair make a great fuss before setrling down to roost. The natives have a peculiar superstition about the cry of this bird: on hearing it the women shake their breasts as they say otherwise they would have no milk if they brought forth a child. The eggs are three or four in number laid in a flattish nest, usually built in the limbs of a gurntree. I found a nest of the wedge-tailed eagle, built in a small isolated white gum surrounded by thicket, and on three different occasions I disturbed the bird from the nest which contained no eggs. On the third occasion I shot at the bird as she left the nest, feeling sure it must contain eggs, bur it did not and the bird either forsook the nest or died from the shot. The nest was about twenty feet from the ground. In a large white gum, close to the Minilya road where a good many teams passed, I found another nest but a native shepherd rook and ate the eggs, much ro my disgust. The prerry litrle kestrel 9 was also a common species, laying five or six eggs in the decayed timber inside a hollow tree limb. I only found one nest of the sparrow hawk 10 , built on a horizontal white gum limb about twenty feet from the ground. Fairy martins (Hirundo ariel) built their peculiar, retort-shaped, mud nests under the house veranda; there was also a colony of them about four miles distant at Cardabia Creek, many nests being built on the steep shady bank hanging over a pool of water - and rwo or three were built on the trunk of a white gum tree also hanging over the water, a situation which I never observed again. I well recollect getting half way up to a hawk's nest, situated near the rop of a lofty gurntree, only to find that hundreds of the large fierce sergeant or bull ants (bulldogs) were in possession of the trunk and limbs, and gave me many painful bites before I reached the ground again. Brockman asked if I would like to go on board the Australind again and meet old friends as she was due in port soon, and I gladly accepted his offer of a horse on which ro ride. The Australind had been very unlucky in her first year on the coast. The first time she carne our of Frernanrle she ran down the schooner Annie Usle which was riding at anchor at night. This cost the owners about £2,000 in compensation. Then, I think on her next trip, she lay alongside Geraldton Wharf to take in cargo, trusting to her shallow draught, but when she tried to get under way she was hard and fast aground, and a great deal of her cargo had ro be discharged into lighters before she floated. These, and other lirrle mishaps, cost Messrs. Bethel Gwynne & Co. a great sum of money, so much so that as Mr. C. Bethel himself told me afterwards it was decided at the Annual Meeting of Directors to rake her off the coast of Western Australia; Mr. Bethel pleaded to give her another chance, and she had no more bad luck and paid handsomely. Well, I duly rode inro Carnarvon, and spent a very pleasant evening on the old boar meeting Mr. and Mrs. C. Bethel and all the old officers. We had a sing-song with 'Auld Lang Syne' to end. Spencer had come into Carnarvon to ride out an old white mare that had got away from the station, and been running wild for many years. He tried ro ride her first in front of Mr. Campbell's house at Yankee Town; as soon as he mounted she prornprly backed

25

on to the veranda, and wiped him off her back with the roof. After trying a few more times, he decided to lead her out to the Station and re-break her in there. It had rained heavily the previous night, and rained again steadily the next night - about two inches in all. This welcome winter rain usually falls at least once in winter- usually in July - and helped by other showers causes a plentiful growth of feed. We had to take back the Boolathana buggy from Port, and started out with the old white mare towing astern of it. We wanted to get away quickly as it was possible the Gascoyne River might run, and we should be unable to cross it. However, it had not, and we got well on our way until we came to the large clay flats that extend for miles to the head of the Boolathana pool. These flats were covered with water from six to twelve inches deep, and of course no signs of the road or track could be observed except at long intervals where a piece of high ground was out of the water, and we had to steer as straight a course as we could from one of these ridges to the next where the road appeared. Consequently, the wheels frequently got into clay holes two or three feet deep, and we had to proceed at a walk, not arriving at the Station until sundown. One could see what enormous quantities of water are drained off these flats as the water cannot soak through the clay. The gully leading into the Boolathana pool was now a fair-sized river. The Gascoyne River in my experience has more than once come down in flood (run a banker, colonial), and then run strongly for weeks after, without any rain or even clouds having been observed from the lower settled parts: heavy rains falling in the interior, perhaps 600 or 800 miles from the mouth of the River on the immense open clay flats towards the head of the River, accounted for this. Bets were made at the Station as to the hour when the pool would be filled, but no one could claim the bet, or state the exact time, as the second night after our return we were all aroused from our sleep by a deep, mighty roar. Running down to the huge dam that blocked the end of the pool about one hundred yards below the house, we found that it had been carried away, and a raging torrent was pouring through the gap with all the summer store of water making its way to the sea. The mistake was in allowing the water to run over the dam itself: this was formed of clay in which there was a large proportion of sand and it began to be eaten away as soon as the water trickled in. It should have been faced with stone or, better still, a 'bywash' provided at one end, paved with stone, to allow the surplus water to escape. This was done some years later when the Station changed hands. As soon as the flats had drained a little, we started to tail the lambs of the more recently dropped (born) lots. The operation is simple and speedy: two or three lamb catchers are appointed to each operator; the lambs when caught are held against the shoulder of the catcher, one of whose hands (the right) holds the right fore and hind legs of the lamb, doubled up, his left hand holding the legs of the left side; the lamb is then rapidly castrated and, if a male, ear-marked and tail cut off. It is surprising how many a smart man will get through in an hour, if the catchers do not keep him waiting. If the lambs are of good size and condition the tails are very palatable grilled on hot coals after being cleaned by the simple process of squeezing off the skin

26