Initiation and Mystagogy in Thomas Aquinas: Scriptural, Systematic, Sacramental and Moral, and Pastoral Perspectives (Thomas Instituut Utrecht) 9042941278, 9789042941274

On what grounds could Aquinas's interpretation of Isaiah be called mystagogical? How does he account for growth in

131 24 2MB

English Pages 364 [365] Year 2019

ABBREVIATIONS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

1. Aquinas’s Prooemium to his Commentary

2. Aquinas on Isaiah 50-53

3. Aquinas on Isaiah 64-66

3. The Role of Others on the Way to Faith: The Thomistic Version of Mystagogy

4. Some Final Thoughts on Aquinas’ Reference to Physics VIII

5. Interpretation of the Case Study

INDEX THOMISTICUS

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Hjm Schoot (editor)

- J Verburgt (editor)

- J Vijgen (editor)

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

INITIATION AND MYSTAGOGY IN THOMAS AQUINAS Scriptural, Systematic, Sacramental and Moral, and Pastoral Perspectives

HENK SCHOOT, JACCO VERBURGT and JÖRGEN VIJGEN (EDS.)

THOMAS INSTITUUT UTRECHT – PEETERS LEUVEN

INITIATION AND MYSTAGOGY IN THOMAS AQUINAS

Publications of the Thomas Instituut te Utrecht (Tilburg School of Catholic Theology, Tilburg University, Netherlands) New Series, Volume XIX Editorial Board Prof. dr. H.W.M. Rikhof, Prof. Dr. H.J.M. Schoot, Prof. dr. R.A. te Velde Managing Editor Prof. Dr. H.J.M. Schoot Previously published in this Series: Vol. I

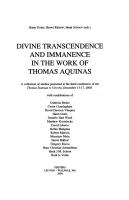

Henk J.M. Schoot, Christ the 'Name' of God. Thomas Aquinas on Naming Christ, 1993 Vol. II Jan G.J. van den Eijnden ofm, Poverty on the Way to God. Thomas Aquinas on Evangelical Poverty, 1994 Vol. III Henk J.M. Schoot (ed.), Tibi soli peccavi. Thomas Aquinas on Guilt and Forgiveness, 1996 Vol. IV Harm J.M.J. Goris, Free Creatures of an Eternal God. Thomas Aquinas on God’s Infallible Foreknowledge and Irrisistible Will, 1996 Vol. V Carlo Leget, Living with God. Thomas Aquinas on the Relation between Life on Earth and ‘Life’ after Death, 1997 Vol. VI Wilhelmus G.B.M. Valkenberg, Words of the Living God. Place and Function of Holy Scripture in the Theology of St. Thomas Aquinas, 2000 Vol. VII Paul van Geest, Harm Goris, Carlo Leget (eds.), Aquinas as Authority. A Collection of Studies presented at the Second Conference of the Thomas Instituut te Utrecht, December 14-16, 2000, 2002 Vol. VIII Eric Luijten, Sacramental Forgiveness as a Gift of God. Thomas Aquinas on the Sacrament of Penance, 2003 Vol. IX Mark-Robin Hoogland c.p., God, Passion and Power. Thomas Aquinas on Christ Crucified and the Almightiness of God, 2003 Vol. X Stefan Gradl, Deus Beatitudo Hominis. Eine evangelische Annäherung an die Glückslehre des Thomas von Aquin, 2004 Vol. XI Barbara Roggema, Marcel Poorthuis, Pim Valkenberg (eds.), The Three Rings. Textual Studies in the Historical Trialogue of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, 2005 Vol. XII Fáinche Ryan, Formation in Holiness. Thomas Aquinas on Sacra doctrina, 2007 Vol. XIII Harm Goris, Herwi Rikhof, Henk Schoot (eds.), Divine Transcendence and Immanence in the Work of Thomas Aquinas, 2009 Vol. XIV Matthew Kostelecky, Thomas Aquinas’s Summa contra Gentiles: a mirror of human nature, 2012 Vol. XV Kevin E. O’Reilly, o.p., The Hermeneutics of Knowing and Willing in the Thought of St. Thomas Aquinas, 2013 Vol. XVI Harm Goris, Lambert Hendriks, Henk Schoot (eds.), Faith, Hope and Love. Thomas Aquinas on Living by the Theological Virtues, 2015 Vol. XVII Harm Goris and Henk Schoot (eds.), The Virtuous Life. Thomas Aquinas on the Theological Nature of Moral Virtues, 2016 Vol. XVIII Anton ten Klooster, Thomas Aquinas on the Beatitudes. Reading Matthew, Disputing Grace and Virtue, Preaching Happiness, 2018

HENK SCHOOT, JACCO VERBURGT AND JÖRGEN VIJGEN (EDS.)

INITIATION AND MYSTAGOGY IN THOMAS AQUINAS Scriptural, Systematic, Sacramental and Moral, and Pastoral Perspectives A collection of studies presented at the sixth conference of the Thomas Instituut te Utrecht (Tilburg University), December 13-15, 2018.

with contributions of Bai Ziqiang Marta Borgo Anton ten Klooster Matthew Levering William C. Mattison III Conor McDonough op Kevin O’Reilly op Paul M. Rogers Piotr Roszak Randall B. Smith Daria Spezzano Rudi te Velde Jacco Verburgt Jörgen Vijgen Jeffrey Walkey Thomas Adam Van Wart PEETERS LEUVEN – PARIS – BRISTOL, CT 2019

A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

© Stichting Thomasfonds - Utrecht ISBN 978-90-429-4127-4 eISBN 978-90-429-4128-1 D/2019/0602/107 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm or any other means without written permission from the publisher.

ABBREVIATIONS WORKS OF THOMAS AQUINAS Cat In Joh Comp Theol Contra Imp De Car De Causis De Malo De Perf De Pot De Spe De Spir Creat De Uni Int De Ver De Virt In I Cor In Col In De An In De Div Nom In De Trin In Eth In Gal In Hebr In Is In Job In Joh In Matt In Phys In Psalmos In Rom In Sent QD De An Quodl ScG STh Super Decr

Catena aurea in Ioannem Compendium Theologie Contra Impugnantes Dei cultum et religionum Quaestio disputata de caritate Super librum De causis Quaestiones disputatae de malo De perfectione spiritualis vitae Quaestiones disputatae de potentia Quaestio disputata de spe Quaestio disputata de spiritualibus creaturis De unitate intellectus contra Averroistas Quaestiones disputatae de veritate Quaestiones disputatae de virtutibus Super I Epistolam ad Corinthios Super Epistolam ad Colossenses Sententia Libri De Anima Super librum Dionysii De divinis nominibus Super Boetium De Trinitate Sententia Libri Ethicorum Super Epistolam ad Galatos Super Epistolam ad Hebraeos Expositio super Isaiam ad litteram Expositio super Job ad litteram Lectura super Ioannem Lectura super Matthaeum Sententia super Physicam Postilla super Psalmos Expositio super Epistolam ad Romanos Scriptum super libros Sententiarum Quaestio disputata de anima Quaestiones de quolibet Summa contra Gentiles Summa Theologiae Expositio super primam et secundam Decretalem

a ad cap co d obj q qc s.c.

articulus answer to objectio caput corpus articuli (=responsum) distinctio objectio quaestio quaestiuncula sed contra

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION A Variety of Perspectives on Initiation and Mystagogy in Thomas Aquinas Henk Schoot, Jacco Verburgt and Jörgen Vijgen................................... 9 PART I: SCRIPTURAL PERSPECTIVES Mystagogy and Aquinas’s Commentary on Isaiah: Initiating God’s People into Christ Matthew Levering ................................................................................. 17 Thomas Aquinas on Mystagogy and Growing in Faith Piotr Roszak ......................................................................................... 41 ‘Putting on’ the Lord Jesus Christ: Thomistic Reflections on Kenosis and the Christ Hymn as a Model for Mystagogical Formation Jeffrey M. Walkey ................................................................................. 61 PART II: SYSTEMATIC PERSPECTIVES Confortat et Excitat Intellectum Addiscentis: A Note on Aquinas’ Aristotelian Conception of Teaching Jacco Verburgt ..................................................................................... 83 Aquinas on the Linguistic Intelligibility of the Mystically Ineffable Thomas Adam Van Wart..................................................................... 105 The Trinity’s Mission as the Highest Form of Both Divine Pedagogy and Human Knowing: A Retrieval of St. Thomas Bai Ziqiang ......................................................................................... 123 From Sacrament to Reality: Aquinas on the Mystagogy of the Holy Spirit Daria Spezzano .................................................................................. 137 The Dual Aspect of Faith’s Instinct: A Thomistic Introduction to the Sensus Fidei Paul M. Rogers................................................................................... 159

Why Aquinas does not have a Mystical Theology: Dionysian Mystagogy versus Thomistic Science Rudi te Velde ...................................................................................... 171 PART III: SACRAMENTAL AND MORAL PERSPECTIVES Per fidem et fidei sacramenta: Baptism and Faith in the Theology of St.Thomas Aquinas Conor McDonough OP ...................................................................... 191 ‘I Believe! Help My Unbelief!’: A Thomistic Account of Growth in Faith and Charity William C. Mattison III ...................................................................... 205 Patiens Divina in the Summa Theologiae: A Key to Understanding Thomas’s Experience during Mass at the Chapel of St. Nicholas, Naples, on 6 December 1273 Kevin O’Reilly OP .............................................................................. 225 Meekness, Justice and Piety: The Moral Transformation of Sophie Scholl Anton ten Klooster .............................................................................. 251 Mystagogy and Sin: Thomas Aquinas on the Relation between Luxuria and the Spiritual Life Jörgen Vijgen ..................................................................................... 273 PART IV: PASTORAL PERSPECTIVES Aquinas’ Academic Sermons between Theory and Practice Marta Borgo ....................................................................................... 295 Initiating Young Friars into a Culture of Preaching: The Connections between Thirteenth Century Preaching and Biblical Commentary Randall B. Smith ................................................................................. 323 On the Authors ................................................................................... 351 Index Nominum.................................................................................. 353 Index Thomisticus ............................................................................... 357

A VARIETY OF PERSPECTIVES ON INITIATION AND MYSTAGOGY IN THOMAS AQUINAS Henk Schoot, Jacco Verburgt and Jörgen Vijgen

The sixth international conference of the Thomas Instituut te Utrecht (Tilburg University), held in December 2018 in Utrecht, was devoted to the theme of Initiation and Mystagogy in Aquinas, approached from different perspectives.1 There were two reasons for adopting this theme. The first reason was that of the two research programs we have at Tilburg School of Catholic Theology, one is entitled ‘Initiation and Mystagogy in the Christian Tradition.’ This research program is primarily focused on the Church Fathers, but we were convinced that it would be fruitful to address the topic of initiation and mystagogy within the work of Aquinas as well. The second reason is related to this. For our past two conferences were devoted to virtue: the first to the theological virtues, and the second to the relationship between acquired and infused moral virtues. We could not find the time to discuss Aquinas’ thoughts on growth in virtue, on exercising virtue, on progressing on the way of faith, hope and love. The theme of initiation and mystagogy gives us this very opportunity. Most of us who are acquainted with the study of the work of Thomas Aquinas, however, will admit that the theme of Initiation and Mystagogy is a surprising and challenging one. Apart from his writings on the Eucharist, Aquinas’ work on the sacraments, a context in which initiation and mystagogy are very relevant, is rather understudied. For instance, it is hard to find any specialised study on Aquinas’s thoughts on the sacrament of baptism, written in the last sixty years or so.2 Why is that 1 The preparation of the conference as well as the publication of this volume was contributed to financially by the Diocese of Haarlem-Amsterdam, the Tilburg School of Catholic Theology as well as the Stichting Thomasfonds and a few other foundations, for which we are most grateful. 2 There are happy exceptions to this rule. See Michael Dauphinais, ‘Christ and the Metaphysics of Baptism in the Summa Theologiae and the Commentary on John’, in Matthew Levering and Michael Dauphinais (eds), Rediscovering Aquinas and the Sacraments. Studies in Sacramental Theology (Chicago/Mundelein, Illinois: Hillenbrand Books, 2009) 14-27; Etienne Dumoulin, La Théologie du Baptême d’après saint Thomas d’Aquin (Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, 2015).

10

INTRODUCTION

the case? It seems that here we have another example of a mechanism that is rather well-known in theology. The mechanism is that theologians could not or did not want to differentiate between Thomas Aquinas on the one hand, and Neo-Thomism and Neo-Scholasticism on the other. Theologians did not always turn to Aquinas himself in their efforts to resource theology. It was Joseph Ratzinger who voiced this perspective in an address that was published in 1972. 3 The address is on the relationship between baptism and the wording of the faith. Central to this paper is the position that during the second millennium, any relationship between baptism on the one hand and the wording of faith on the other was lost. He expresses as his view that baptism has deteriorated into a ritual which is all too objective, and that faith seems to have become rather static, existentially irrelevant, and not even a prerequisite for a fruitful baptism. Ratzinger even advocates the abolishment of the very distinction between validity and licitness, in this case of baptism, a distinction which is at the origin of the Catholic participation in the ecumenical movement. This pessimistic view of Ratzinger (there is no way out, he says) might be a major reason behind the abandonment of the study of Aquinas on the sacrament of baptism, or, more probably, might express a widely shared view among theologians at the time.4 One can illustrate this well, when one compares the treatment of baptism in a neo-thomist manual on the one hand, and the Catechism of the Catholic Church of 1995 on the other. There are five considerable differences between the catechism and the manual written by Franz Diekamp.5 In the catechism (1) The distinction between matter and form has disappeared. (2) Instead of prooftexting the reader is acquainted with the salvation historical background of baptism. (3) There is hardly a mention any more of the validity of baptism (only in 1306) and no mention of licitness at all, whereas instead there is talk about the recognition of baptism of non-Catholics. These three are instructive indeed, but the last two are even more telling: 3 ‘Taufe und Formulierung des Glaubens’, Didaskalia II (1972), 23-34. Also published in G.L. Müller (Ed), Joseph Ratzinger Gesammelte Schriften Vol. 9/1: Glaube in Schrift und Tradition: Zur Theologischen Prinzipienlehre (Freiburg etc: Herder, 2016), pp. 462-475. 4 An echo of this may be found in the Introduction of Levering and Dauphinais, Rediscovering Aquinas and the Sacraments, p. x. 5 Theologiae Dogmaticae Manuale (Paris etc.: Desclée & Sociorum, 1933-), Vol. IV (1946) pp. 81-109. Catechism of the Catholic Church, nrs. 1213-1284. One has to bear in mind, though, that there is a major difference between both genres of texts, and that there were more manuals than the one by Diekamp only.

INTRODUCTION

11

(4) There is a new section, in comparison with Diekamp, on the liturgical celebration of baptism. This new section on the liturgy of baptism is divided in two parts. The first part is devoted to initiation, the second to mystagogy (sic). The first part addresses what is essential for becoming a Christian, and mentions the catechumenate, which was restored by Vatican II. The second part discusses the way in which the celebration of baptism is in fact an initiation into Christian mystery, and it explains the different elements of the celebration itself. It is rather surprising to recognize here the theme of this conference, Initiation and Mystagogy. It raises the question: what would Aquinas say on this? (5) A last interesting point of difference is intriguing as well, but even harder to interpret. Diekamp’s treatment of baptism discusses the person who receives baptism last. The one baptised enters the discussion only after the discussion on the minister of baptism is finished. The Catechism of the Catholic Church turns it around; it discusses first the one to be baptised, and the minister of baptism only after this. That procedure of course reflects the new emphasis Vatican II places on the common priesthood of all who are baptised, distinguishing it from the ministerial priesthood. Many research questions follow from these points of comparison. For instance: does Aquinas indeed leave the catechumenate out of his discussion of baptism? The answer is: no, he does not, he discusses it, and considers it convenient that catechetical instruction precedes baptism.6 Is Aquinas aware that baptism is a sacrament of faith, and thus that baptism and faith are inherently connected to each other? The answer is: yes.7 How does Aquinas consider the right sequence of the receiver and the minister of baptism? Interestingly enough, Aquinas changes his views on this. In his commentary on Peter Lombard he follows the same procedure as the catechism: first the receiver and then the minister. But in the Summa Theologiae he reverses the order.8 Why? Aquinas does not explicitly say why he chooses this sequence, so more research is needed on this issue. The example of baptism may serve as pars pro toto, as an example of how the development of theology in the second half of the twentieth century can provide us with new perspectives on the thought of Aquinas, and invites us to read his texts anew, and bring them to life. That

6

STh III, q. 71 a. 1. STh III, q. 68 a. 8. See Dumoulin, La Théologie du Baptisme, on the relationship between baptism and preaching. 8 STh III, q. 67 is on the ministers of baptism, q. 68 on the recipients. The reverse order can be found in In IV Sent d. 5 and d. 4 respectively. 7

12

INTRODUCTION

is what those who contributed to the conference and wrote essays for this volume have done. Because the essays address a wide array of themes and attest to a variety of perspectives, the volume is divided into four parts: (I) Scriptural, (II) Systematic, (III) Sacramental and Moral, and (IV) Pastoral perspectives. The remainder of this introduction offers a brief synopsis of each of the essays. Part I: Scriptural Perspectives In the first part, three papers discuss our topic from the perspective of Thomas’ biblical exegesis. On the basis of the claim that Christian mystagogical text leads its readers into the mysteries of God and Christ, by reflecting upon the liturgy and upon the New Testament in light of the Old (and vice versa), Matthew Levering argues that Thomas sees the prophet Isaiah as a mystagogue and the purpose of the book Isaiah to lead God’s people into the hidden mysteries of God and Christ. A careful analysis of selected chapters from Thomas’ commentary on Isaiah shows, moreover, that Thomas sees his own work as having such a mystagogical purpose. Such a mystagogical reading of the Old Testament is closely related to the often employed distinction between implicit and explicit faith, between the faith of the minores and of the maiores. Piotr Roszak addresses this distinction in his paper, in which he, drawing heavily on Aquinas’ biblical commentaries, discusses Thomas’ account of the dynamics of the growing in faith and the role of the affective dimension of faith in transitioning to the fullness of faith. Jeffrey Walkey argues that for Thomas the Christ hymn of Philippians 2 is also a model for the Christian life because it speaks to the importance of imitating Christ’s humility and obedience, including the assurance that like Him we will be vindicated and exalted by God. This becomes especially apparent in Aquinas’ explicit use of the hymn in his questions on martyrdom and religious life and its implicit presence in his inaugural lectures. Ultimately, Walkey argues, just as Christ’s kenosis leads to His exaltation, so too, our analogous kenosis in mystagogical formation through imitation of Christ can lead to glory. Part II: Systematic Perspectives The systematic part opens with Jacco Verburgt’s essay on the Aristotelian features of Aquinas’ conception of teaching, especially in light of two present-day teaching and learning models, namely the transmission model

INTRODUCTION

13

and the facilitation model. By way of a close reading of the relevant texts and their Aristotelian sources, he argues that for Aquinas teaching is in a robust Aristotelian sense an activity of leading, or initiating in the sense of causing or enabling a learning process to begin and develop, especially in terms of a student’s intellectual capacities. Thomas Adam Van Wart challenges the assumption in modern thought that ineffability and intelligibility are ultimately opposed to each other. Instead, he argues that Thomas’ distinction between first and second order intentionality, the res significata and the modus significandi, allow for him to speak intelligibly of the ineffable God with whom he seeks mystical union with perfect logical coherence. Moreover, these distinctions also facilitate that union by adding greater clarity to the depth of the very mysteries we are called to contemplate. Ultimately, the mystically ineffable comes about precisely by way of the linguistically intelligible and they are therefore not opposed but complementary. The contribution of Bai Ziqiang connects Thomas’ two accounts of the divine persons’ new mode of presence through the invisible missions (that is, the ontological presence of the Scriptum and the intentional presence of the Summa) with his views about human pedagogy in order to show how divine pedagogy and human knowing are actually one in the human person who develops being an imago Trinitatis. He makes it clear that, for Thomas, divine initiation and mystagogy in the highest form is a divine work that, at the same time, involves an active role of human beings. Daria Spezzano focuses on the threefold role of the Holy Spirit in sacramental initiation. The Holy Spirit is first cause of baptism by applying Christ’s Passion to each individual, and so conforming them to the love and obedience of Christ Crucified. To the Spirit is appropriated the work of deification, the gift of a participation in the divine nature. The Holy Spirit is the primary mystagogue in the sacraments, especially through the Spirit’s gift of understanding by the internal guidance of the faithful who are entering into the mystery of salvation. The path of sacramental initiation, according to Spezzano’s reading, is a Spiritenabled and Spirit-led journey from knowledge of the sacramentum to union with the res. Paul Rogers argues that Thomas’ instinct of faith offers a superior approach for integrating belief in both its personal and communal aspects which has important implications for the doctrine of the sensus fidei namely in sofar as it prevents an overemphasis of either its personal (sensus fidelis) or ecclesial (sensus fidelium) dimensions. Engaging with the International Theological Commission’s 2014 ‘Sensus Fidei in the Life of the Church’ and the twentieth-century theologian Pierre Benoit,

14

INTRODUCTION

he argues in favor of ‘ecclesial instinct’ that must operate in tandem with the individual’s instinct of faith in order to do justice to both the individual’s act of faith and the Church’s role in bringing this individual’s act to birth and subsequently in nurturing it. In the final contribution of this systematical part Rudi te Velde argues that Thomas does not have, in the Dionysian sense, a ‘mystical theology’ as integral part of his theological project. On the basis of a discussion of the place of the treatise On Mystical Theology in the theological program of Dionysius and an examination of a number of references in Aquinas’ writings to Dionysius’ treatise, te Velde describes Dionysius’ project of theology as an upward journey through a complex dialectic of affirmations and negations, which culminates in the final negation of a mystical theology, a union with God in ‘unknowing’, in which all mediation of language and thought is left behind. This ‘being united with God as unknown’, Te Velde argues, does not lead to a distinct mystical theology, as the culmination of the via negativa, in Thomas’ reception of Dionysius. The reasons are that Thomas rejects the Neoplatonic transcendence of the One beyond Being (and thus beyond thought), and that the apophatic dimension of On Mystical Theology is integrated as part of the structural mediation of the threefold way according to which God is knowable to us (namely, causality, negation, and eminence). Part III: Sacramental and Moral Perspectives The third part deals with sacramental and moral perspectives. Connor McDonough’s contribution addresses the objection that the emphasis on the power of the sacraments of the New Law to confer grace on the recipient as seen in Catholic, and especially Thomistic, accounts of the sacraments risks downplaying faith as the factor which incorporates us into the Body of Christ. Focusing on the manner in which Thomas relates faith and baptism, the author, however, argues that Thomas refuses the post-Reformation disjunction, affirming both the necessity of baptism and the reality of pre-baptismal life in Christ. William C. Mattison addresses the tension between Thomas’ claims that a person can grow in virtue such as faith and charity, and nonetheless that a person with faith and charity does all one does for the sake of God as last end. In other words, given what Aquinas says about faith and charity, how can one possess them and yet also grow in them? The author focuses on charity’s role as form of the virtues in ordering acts of all the virtues toward God as last end and argues that the distinction

INTRODUCTION

15

between actual and habitual is key to how one can possess charity, how there can nonetheless be room for its growth, and how that growth occurs. Kevin O’Reilly addresses Thomas’ understanding of ‘the experience of Divine things’ (patiens divina) and in particular with regard to the relation between the gift of wisdom and the theological virtues of faith and charity. The objective constitution of the gift of wisdom is necessarily rooted in Scripture and Tradition as well as being ecclesial in character. The subjective experience of Divine things, however, admits of different degrees according to the intensity of faith and charity – and therefore of wisdom – that inform the life of the believer. All this is exemplified in a particular way in Thomas’ understanding of the celebration of the Eucharist and his mystical experience towards the end of his life. Anton ten Klooster discusses the case of young German resistance activist Sophie Scholl to illuminate the notion of conversion, as well as to better understand how grace perfects nature. In his study of Scholl’s transformation from being a loyal subject of the Nazi regime to being an active opponent of it, he pays close attention to the alignments Aquinas makes between moral virtues, gifts of the Holy Spirit, beatitudes and fruits of the Holy Spirit in order to understand how Scholl’s virtues are the work of the Spirit. As such, the case of Scholl offers valuable insights on how moral theology can benefit from making use of moral examples such as that of Scholl. In the final contribution in this section Jörgen Vijgen discusses the sin of lust (luxuria) in Thomas’ writings and argues that it presents a principal obstacle in a mystagogical engagement with Christ Incarnate and its continuation in a life of faith, guided by the Holy Spirit. Starting from a discussion of the biblical context in Galatians 5:19-21, he analyses Thomas’ arguments for equating concupiscence with the immoderate desire for bodily pleasures in general and sexual pleasures in particular, emphasizing the largely Aristotelian basis for such an equation. These insights are crucial for understanding Thomas’ reflections on the features and effects of the sin of lust as instrumental in leading to a false vision of the truth and in one’s inability to grasp a correct vision of it. Vijgen argues that Thomas gives a coherent account of the gravitational pull of sexual lust and its corrupting influence on reason and will – consisting primarily in the vices of folly and blindness of mind as obstacles to the reception of grace.

16

INTRODUCTION

Part IV: Pastoral Perspectives The final part of this volume basically deals with Thomas Aquinas as Dominican preacher. Marta Borgo takes the latest volume of the Leonine edition containing Thomas’ sermons as starting point to investigate how Thomas describes the art of preaching and its requirements as regards both the preacher and the audience. Relying on philological and historical insights, she describes the nature of preaching as a kind of prophecy, that is to say, as an interpretation of the revealed Word. His sermons also reveal the intellectual and moral prerequisites of the audience, following the example of Christ as a foundational model. Randall Smith complements Borgo’s contribution in sofar as he argues that young prospective preachers learned to preach not only by listening to preaching but also by the way they were actually being taught the Scriptures. He shows that throughout Thomas’ biblical commentaries, we repeatedly find passages that employ one or more of the methods commonly used in thirteenth century sermo modernus-style sermons. As such, much of the content of these commentaries was delivered with an eye for its use in preaching. Thus, this volume ends where it began, namely with the perspective of reading Scripture.

MYSTAGOGY AND AQUINAS’S COMMENTARY ON ISAIAH: INITIATING GOD’S PEOPLE INTO CHRIST Matthew Levering

Introduction During the early medieval period, in the Greek East at least, the term ‘mystagogy’ could be applied to a variety of theological genres. For example, Photios’s Mystagogia was written to demonstrate the erroneous character of the doctrine of the filioque. Photios’s mystagogy aims to correct Latin theologians who have gone astray and who need to be reintroduced to the divine mystery of the Holy Spirit. Thus, Photios tells his putative Augustinian opponent who has blasphemed against the Holy Spirit, ‘If on the one hand you have committed the unforgivable sin, then I must refute, convict and overturn every one of your earthly doctrines. But if you simply need your sight healed, then I must go before you and cure you from the same vessel of truth, which allays pain and cleanses illness.’1 Leading his opponents (and his readers) into the divine mystery of the Holy Spirit, Photios describes his highly doctrinal text as a ‘mystagogy’ because it seeks to heal the Latin theologians of what he considers to be their rationalistic misapprehension of the Spirit. Photios’s Mystagogia would not today be understood as an exemplar of ‘mystagogy.’ Today, the term generally evokes the catechetical practice of the fourth-century Fathers, or the mystical treatises of various saints and doctors of the Church.2 Gregory of Nyssa’s Life of Moses stands as a prominent example. After an introduction, the Life of Moses briefly sketches the biblical narrative about Moses’ life, and 1

Saint Photios, The Mystagogy of the Holy Spirit, trans. Joseph P. Farrell (Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 1987), §31, p. 75. 2 For further discussion of patristic understandings of mystagogy, see Christoph Jacob, ‘Zur Krise der Mystagogie in der Alten Kirche,’ Theologie und Philosophie 66 (1991), 75-89; Enrico Mazza, Mystagogy: A Theology of Liturgy in the Patristic Age, trans. Matthew O’Connell (New York: Liturgical Press, 1989). For a translation of patristic mystagogy (as popularly understood, often in sharp contrast to scholastic and neo-scholastic theology—with Bonaventure seen as a laudable thirteenth-century exception because of his mystical writings) into a contemporary Rahnerian and liberation-theology key, see David Regan, C.S.Sp., Experience the Mystery: Pastoral Possibilities for Christian Mystagogy (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1994).

18

MATTHEW LEVERING

then moves from this historia to the theoria or ‘spiritual meaning of the Scriptural narrative,’ which involves the soul’s ascent to God through Christ, the sacraments, and the ascetic life 3 Another important ‘mystagogical’ work is Cyril of Jerusalem’s ‘Mystagogical Catecheses,’ delivered to newly baptized Christians whom Cyril seeks to lead into the ‘spiritual and heavenly Mysteries’ of the Christian faith.4 Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite’s The Ecclesiastical Hierarchy provides a further example, deeply influential in both East and West. In contemplating the nature and role of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, PseudoDionysius undertakes the following task: ‘Our hierarchy consists of an inspired, divine, and divinely worked understanding, activity, and perfection. With the aid of the transcendent and most sacred scriptures, I must demonstrate this to those who have been initiated in the sacrament of the sacred mystagogy by our hierarchy’s mysteries and traditions.’5 In a footnote to this passage, Paul Rorem explains that when PseudoDionysius uses the word ‘mystagogy,’ he has in view ‘guidance into something mysterious or secretly revealed.’6 Another expert on the works of Pseudo-Dionysius, Alexander Golitzin, affirms that the Ecclesiastical 3 Abraham J. Malherbe and Everett Ferguson, ‘Introduction,’ in Gregory of Nyssa, The Life of Moses, trans. Abraham J. Malherbe and Everett Ferguson (New York: Paulist Press, 1978), 1-23, at p. 3. For further insight into Gregory of Nyssa’s mystagogy, see for example Johan Leemans, ‘Bible, Rhetoric and Theology: Some Examples of Mystagogical Strategies in St. Gregory of Nyssa’s Sermons,’ in Seeing Through the Eyes of Faith: New Approaches to the Mystagogy of the Church Fathers, ed. Paul van Geest (Leuven: Peeters, 2016), 105-23; Piet Hein Hupsch, ‘Mystagogical Theology in Gregory of Nyssa’s Epiphany Sermon In diem luminum,’ in Seeing Through the Eyes of Faith, 125-36. For Gregory, as Leemans says, mystagogy enables believers to enter ‘deeper and deeper into a relationship with God’ through a ‘salvific process of deification’ (‘Bible, Rhetoric and Theology,’ p. 123). Hupsch appreciates the role of ‘Gregory’s Christological explanation of Scripture’ (‘Mystagogical Theology in Gregory of Nyssa’s Epiphany Sermon In diem luminum,’ p. 136). 4 Cyril of Jerusalem, ‘Mystagogical Catechesis I: On the Rites before Baptism,’ in Cyril of Jerusalem, St. Cyril of Jerusalem’s Lectures on the Christian Sacraments: The Procatechesis and the Five Mystagogical Catecheses, trans. R. W. Church, ed. F. L. Cross (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1986), 53-58, at p. 53. See also such studies as Michiel Op de Coul, ‘The Lenten Lectures of St. Cyril of Jerusalem: From Pedagogics to Mystagogy,’ in Seeing Through the Eyes of Faith, 485-99; Pamela Jackson, ‘Cyril of Jerusalem’s Use of Scripture in Catechesis,’ Theological Studies 52 (1991), 431-50. 5 Pseudo-Dionysius, The Ecclesiastical Hierarchy, in Pseudo-Dionysius, The Complete Works, trans. Colm Luibheid with Paul Rorem (New York: Paulist Press, 1987), 195-259, at p. 195. 6 Ibid., p. 195 n. 3. See also Maximus the Confessor’s Mystagogia, ed. Christian Boudignon (Turnhout: Brepols, 2011); as well as Andrew Louth, ‘Mystagogy in Saint Maximus,’ in Seeing Through the Eyes of Faith, 375-88.

MYSTAGOGY AND INTERPRETING ISAIAH

19

Hierarchy is not only the ‘core and pivot of the Dionysian system,’ but also that Pseudo-Dionysius’s entire corpus, written for monks, was intended to function ‘as a deliberately progressive ‘mystagogy,’ that is, as at once the explication of and the entry into the one and unique mystery, Christ.’7 According to the liturgical theologian Goffredo Boselli, interpreting the Old and New Testaments together is inevitably mystagogical. Through the prophets of Israel, God teaches his people divine mysteries that become clear in and through Jesus Christ. Boselli directs attention to Ephesians 1:9, where Paul praises God for making ‘known to us in all wisdom and insight the mystery of his will’; and Boselli also points to Matthew 13:11, where Jesus tells his disciples that ‘[t]o you it has been given to know the secrets [ȝȣıIJȒȡȚĮ] of the kingdom of heaven’ (Mt 13:11; see also Mk 4:10 and Lk 8:10). Ultimately, says Boselli, ‘The risen Christ himself must be the exegete of his mystery hidden in the Scriptures,’ as when on the Road to Emmaus the risen Christ ‘interpreted to them in all the Scriptures the things concerning himself’ (Lk 24:27).8 The Augustine scholar William Harmless has added that, for Augustine, it would not be appropriate to focus solely upon the liturgy as the locus of mystagogy. Rather, since Augustine holds that the true mystery is God, Augustine looks not only to the liturgy but also, and primarily, to Scripture. Harmless sums up Augustine’s view: ‘Both the liturgy and the scriptures have ambiguities and a dense symbolic compression, and so both need to be de-encrypted. Such de-encryption is precisely the task of the mystagogue.’9

7

Alexander Golitzin, Mystagogy: A Monastic Reading of Dionysius Areopagita, ed. Bogdan G. Bucur (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2013), p. xxxvi. 8 Goffredo Boselli, The Spiritual Meaning of the Liturgy: School of Prayer, Source of Life, trans. Barry Hudock (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2014), p. 9. Boselli underlines the fact that Scripture is therefore interpreted preeminently in the liturgy: ‘every time that the church breaks the bread of the Word it is Christ himself who is the exegete of his mystery contained in the Scriptures’ (ibid., 10). As the ultimate interpreter of the prophetic texts of Israel’s Scriptures, Christ shows how they are fulfilled. For a contrasting historical-critical view of prophetic texts, see Martti Nissinen, ‘What Is Prophecy? An Ancient Near Eastern Perspective,’ in Inspired Speech: Prophecy in the Ancient Near East: Essays in Honor of Herbert B. Huffmon, ed. John Kaltner and Louis Stulman (London: T. & T. Clark International, 2004), 1637. 9 William Harmless, ‘‘Receive today how you are to call upon God’. The Lord’s Prayer and Augustine’s Mystagogy,’ in Seeing Through the Eyes of Faith, 349-73, at pp. 359-60.

20

MATTHEW LEVERING

From the above, it should be clear that the work proper to ‘mystagogy’ is relatively broad in scope. It involves leading people into the divine mysteries, above all God and Christ; and its tools include reflection upon the liturgy and upon Scripture in its two-Testament unity. Given this background, in the present essay I argue that, without needing to employ the term (and without being familiar with the patristic use of the term, as Rudi te Velde has shown10), Aquinas conceives of the prophet Isaiah as a ‘mystagogue.’ Put simply: guided by the Holy Spirit, Isaiah aims to lead God’s people into the hidden mysteries of God and Christ. Although Aquinas’s Commentary on Isaiah is a literal one,11 I further suggest that Aquinas’s own work of commenting upon the biblical book of Isaiah has the mystagogical purpose of leading believers into the full mystery of Christ. Although Aquinas differentiates clearly between his own work and the inspired words of a biblical author, Aquinas’s understanding of the exegetical task means that as Isaiah needed the Holy Spirit in order to prophecy, so also Aquinas the exegete needs the Holy Spirit, gifting him with faith and wisdom, in order to understand the deeper meaning of Isaiah’s inspired words. 12 By (in different ways) interiorly instructing Isaiah and Aquinas in their knowing of Christ, the Holy Spirit can be said to act as the divine Mystagogue. Aquinas’s Expositio Super Isaiam ad Litteram can of course be analyzed fruitfully from other angles.13 Furthermore, I agree with Joseph 10

See Rudi te Velde’s essay in the present volume. For the dating of his commentary to the period after his return to Paris from Cologne (1252-1253), see Jean-Pierre Torrell, O.P., Initiation à saint Thomas d'Aquin. Sa personne et son oeuvre, 2nd ed. (Paris: Cerf, 2015), p. 445. See also, for a slightly earlier dating, the discussion in James A. Weisheipl, O.P., Friar Thomas d’Aquino: His Life, Thought, and Works, 2nd ed. (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1983), pp. 117-21 and 479-81. Aquinas’s commentary on Isaiah is a ‘cursory’ commentary focused on the literal sense and not attending carefully to every verse, even though it still manages to take up 256 pages in the Leonine edition. It is a much shorter commentary than Aquinas’s full-length commentaries, such as his exposition of the Book of Job. For further background, see Jean-Pierre Torrell, O.P. and Denise Bouthillier, ‘Quand saint Thomas méditait sur le prophète Isaie,’ Revue Thomiste 90 (1990), 5-47. 12 On sacra doctrina and the light of faith, see Aquinas, STh I, q. 1; II-II, q. 1. The grace of the Holy Spirit ‘causes faith not only when faith begins anew to be in a man, but also as long as faith lasts’ (II-II, q. 4 a. 4 ad 3). 13 For example, I do not here explore the medieval structure of Aquinas’s commentary. In this respect, Joseph Wawrykow has pointed out that there exists an ‘autograph’ copy of Aquinas’s commentary with jottings in Aquinas’s own hand. The jottings ‘are called ‘collationes’ by Jacobino d’Asti, who in the late thirteenth century prepared a legible copy of the entire work. Each collatio is made up of a number of members (three, four, or more), each member being a phrase or sentence by Thomas 11

MYSTAGOGY AND INTERPRETING ISAIAH

21

Wawrykow that ‘[p]referring other genres, Aquinas has not written any treatises in spiritual theology’—even if Aquinas’s writings are ‘helpful to those pursuing God.’ 14 Nonetheless, I hope that my application of ‘mystagogy’ to Aquinas’s approach to Isaiah’s prophetic book may deepen our appreciation of what Aquinas is doing for his readers and what Aquinas thinks Isaiah is doing. I set forth the twofold ‘mystagogy’ of Isaiah and Aquinas in concert15 by exploring three sections of Aquinas’s commentary: his Prooemium or Preface (very briefly), his commentary on Isaiah 50-53, and his commentary on Isaiah 64-66. Although Aquinas does not intentionally conceive of his commentary as ‘mystagogical’ or describe Isaiah as a ‘mystagogue,’ my argument is that the reality conveyed by these terms, in their broad sense, is profoundly present in his commentary. 1.

Aquinas’s Prooemium to his Commentary

Aquinas constructs his Prooemium around Habakkuk 2:2-3, which he suggests mirrors the virtues of Isaiah’s inspired text. 16 In the Vulgate followed by an apt biblical citation’ (Wawrykow, ‘Aquinas on Isaiah,’ in Aquinas on Scripture: An Introduction to His Biblical Commentaries, ed. Thomas G. Weinandy, O.F.M. Cap., Daniel A. Keating, and John P. Yocum [London: T. & T. Clark International, 2005], 43-71, at p. 50). Wawrykow is indebted to P.-M. Gils, ‘Les Collationes marginales dans l’autographe du commentaire de S. Thomas sur Isaie,’ Revue des sciences philosophiques et théologiques 42 (1958), 253-64. See also the essay by Randall Smith in the present volume. Regarding the biblical concordance (and other tools) in use in Aquinas’s day, Wawrykow directs attention to M. A. Rouse and R. H. Rouse, Authentic Witnesses: Approaches to Medieval Texts and Manuscripts (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1991), chs. 6-7. The enrichment brought by the collations has been shown most clearly by Denise Bouthillier in her essay ‘Le Christ et son mystère dans les collationes du super Isaiam de saint Thomas d’Aquin,’ in Ordo sapientiae et amoris. Image et message de saint Thomas d’Aquin, ed. Carlos-Josaphat Pinto de Oliveira (Fribourg: Éditions Universitaires, 1993), 37-64. See also Bouthillier’s ‘Splendor gloriae Patris: Deux collations du Super Isaiam,’ in Christ among the Medieval Dominicans, ed. Kent Emery, Jr. and Joseph Wawrykow (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1998), 139-56. Torrell cites volume 28, p. 20* of the Leonine edition to this effect in his Saint Thomas Aquinas, vol. 1: The Person and His Work, trans. Robert Royal (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1996), p. 35. 14 Joseph Wawrykow, ‘Aquinas and Bonaventure on Creation,’ in Creation ex nihilo: Origins, Development, Contemporary Challenges, ed. Gary A. Anderson and Markus Bockmuehl (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2018), 173-93, at p. 186. 15 See J. Ross Wagner, Heralds of the Good News: Isaiah and Paul in Concert in the Letter to the Romans (Leiden: Brill, 2002). 16 For a more detailed analysis of the Prooemium, see Wawrykow, ‘Aquinas on Isaiah,’ 45-48.

22

MATTHEW LEVERING

version of Habakkuk 2:2-3, these verses are different enough to make a modern translation unhelpful. The Vulgate version reads: ‘Write the vision and lay it out on tablets that he who reads it might run through it, for as yet the vision is a great way off and shall appear at the end.’17 Aquinas sets out to explain why this vision describes the prophecy of Isaiah. For my purposes, it will suffice to indicate briefly the two ways in which Aquinas, in his Prooemium, shows that Isaiah is a true ‘mystagogue’—although Aquinas does not use this term. First, the one primarily guiding the writings of Isaiah is not Isaiah himself. Instead, Isaiah is being taught by the Holy Spirit, which explains how he can perceive divine mysteries. Aquinas remarks that ‘the author of Holy Scripture is the Holy Spirit.’18 To support this point, Aquinas quotes 1 Corinthians 14:2, which affirms that one who speaks by the Holy Spirit speaks ‘mysteries.’ 19 In short, the Book of Isaiah is a book of divine ‘mysteries.’ In order to set forth these mysteries, the Holy Spirit inspires the prophet Isaiah and guides the resulting Book of Isaiah. Second, Aquinas praises Isaiah’s writing abilities in terms that call to mind a good ‘mystagogue.’ Isaiah excels at using ‘figures’ or symbolic images drawn from ‘sensible things.’ 20 Like every good mystagogue, Isaiah draws us from sensible things to divine mysteries. Writing before the time of Christ, Isaiah deftly leads the reader to Christ. In Aquinas’s view, the Mosaic law’s deepest intentions needed clarification by the prophet, because, having been written ‘by the finger of God,’ ‘Scripture is deep and obscure and full of many mysteries.’21 17 The parallel RSV of Habakkuk 2:2-3 reads, ‘Write the vision; make it plain upon tablets, so he may run who reads it. For still the vision awaits its time; it hastens to the end.’ 18 Thomas Aquinas, Expositio super Isaiam ad Litteram, trans. Joshua Madden (Lander, WY: Aquinas Institute of Wyoming Catholic College, n.d.), available at https://aquinas.cc/173/513/~182; Preface. The online Latin/English text does not include paragraph numbers. 19 See Piotr Roszak, ‘The Place and Function of Biblical Citations in Thomas Aquinas’s Exegesis,’ in Reading Sacred Scripture with Thomas Aquinas: Hermeneutical Tools, Theological Questions and New Perspectives, ed. Piotr Roszak and Jörgen Vijgen (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2015), 115-39. Roszak observes, ‘Biblical citations appear in Aquinas’s commentaries in order to reveal the wider historical context and connect events with each other as the main hermeneutic assumption is the existence of the one salvation plan’ (ibid., 128). See also Roszak’s ‘Collatio sapientiae: Dinámica participatorio-cristológica de la sabiduría a la luz del Super Psalmos de santo Tomás de Aquino,’ Angelicum 89 (2012), 749-69. 20 Aquinas, In Is Prooemium. 21 Ibid.

MYSTAGOGY AND INTERPRETING ISAIAH

23

Specifically, Isaiah’s task is to help people to believe in Christ. Aquinas argues that the subject matter of the Book of Isaiah ‘is principally the appearing of the Son of God,’ and he connects this with the place of Isaiah in the liturgy (Advent).22 With regard to the mystery of Christ, Aquinas notes that Isaiah teaches not only about Christ’s earthly appearing, but also about two other appearings of Christ. These two are Christ’s appearing to those who believe in him (an appearing through the faith of the Church) and Christ’s appearing in glory at the eschaton. These two appearings, of course, are inextricably related to his historical appearing in the flesh. The task of the mystagogue is to initiate God’s people into these three appearings. In order to investigate how Aquinas considers Isaiah to have accomplished this task, the remainder of this essay focuses on Aquinas’s commentary on Isaiah 50-53 (Christ’s cross and resurrection, to be believed by faith) and on Isaiah 64-66 (eschatology). 2.

Aquinas on Isaiah 50-53

The background to Isaiah 50 is the human need for deliverance from sin, death, and the powers of evil. God has promised in chapter 49 that he will redeem his people from this devastating triumvirate. Aquinas argues that in chapter 50, Isaiah leads his audience into this mystery of divine redemption. Isaiah 50:1 makes clear that Israel has indeed been divorced and sold by God, due to its sins. But this is not to be the final word. Isaiah (or God through Isaiah) recalls God’s power over creation, as manifested in God’s ability to ‘dry up the sea’ and to ‘clothe the heavens with blackness’ (Is 50:2)—which Aquinas interprets as two references to miracles that God performed for Israel during the Exodus. In light of these pointers, Aquinas understands the next line— ’The Lord God has given me the tongue of those who are taught’ (Is 50:4)—as a description of Isaiah the mystagogue (my term). It is not Isaiah who teaches, but rather it is the Lord: ‘For the Lord God helps me […] He who vindicates me is near’ (Is 50:7-8). Relying upon the divine Mystagogue, Isaiah will initiate the people into the mystery of redemption, while also proclaiming judgment upon the unrepentant, who will ‘lie down in torment’ (Is 50:11). Isaiah’s audience, Aquinas notes, is burdened by three things: hopelessness, fear at the strength of their enemies, and fear of punishment. In response, Isaiah encourages the people of Israel to recall God’s wondrous power: ‘Look to Abraham your father and to Sarah who bore 22

Ibid.

24

MATTHEW LEVERING

you’ (Is 51:2). Isaiah is here referring to the miracle of Sarah’s conception, which, given Sarah’s extremely advanced age, could not have occurred by natural causes. Aquinas invokes other biblical passages that complement and deepen the mystery taught in Isaiah 51:2: Genesis 18:11 (the original miracle of Sarah’s conception), Romans 4:19 (Paul’s commentary on this episode), and Ezekiel 33:24 (prophetic commentary on what God has done for Abraham). In Isaiah 51:3, ‘the Lord will comfort Zion,’ the prophet further encourages Israel to rely upon God’s power. Aquinas understands that Isaiah 51:4 refers to Cyrus of Persia and to his ‘command […] concerning the deliverance of the people.’23 At the same time, however, the ‘light to the peoples’ (Is 51:4), who is the deliverance of God, is Christ. Aquinas confirms this by citing Isaiah 9:2, which in the Vulgate version states that the ‘light is risen.’24 Aquinas also contends that Isaiah 50:5’s phrase ‘the coastlands [Vulgate: islands] wait for me’ refers to the nations, so that the audience intended prophetically by Isaiah is not only Israel but the Church of Jews and Gentiles. After commenting on God’s power to save (Isaiah 51:6-8), Aquinas turns back briefly to Isaiah 51:3, where God promises to make Israel’s ‘desert like the garden of the Lord.’ In the Vulgate version, the promise states that God will ‘make its desert as a place of pleasure [quasi delicias], and its solitude as the garden of the Lord.’ Both the RSV version that I have quoted and the Vulgate version are a clear reference to the primordial paradise. Aquinas recognizes that the goal of the coming redemption, which will never end (see Is 51:8), is not simply a political restoration brought about by Cyrus, let alone a new watering of the arid parts of the land of Israel, but rather eternal (paradisal) life in Christ. This is the mystery into which Isaiah is initiating his audience. In this regard, Aquinas comments that ‘the saints have a twofold delight,’ namely, glory and grace.25 Believers will see and delight in God ‘in perfected love, in abundant refreshment, in prominent authority.’26 Even now, believers in Christ experience the grace of God, an experience that involves perceiving God’s truth, loving good works, possessing virtue, and having peace of heart. Isaiah points to this mystery by pledging the coming of God’s everlasting salvation and evoking the joy and paradisal state of the

23

Aquinas, In Is cap LI. Ibid. The parallel RSV text of Isaiah 9:2 reads that ‘those who dwelt in a land of deep darkness, on them has light shined.’ 25 Ibid. 26 Ibid. 24

MYSTAGOGY AND INTERPRETING ISAIAH

25

land of Israel in that day. Aquinas adds cognate passages from Job, the Psalms, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, and Isaiah 58. Isaiah 51 proceeds to beg the Lord to remember his power to act, as seen in his work of creation and in his prototypical saving act of liberating Israel from Egyptian slavery. Aquinas employs a text from Ezekiel 29 in order to link God’s piercing of the ‘dragon’ (Is 51:9) with God’s conquest of Pharaoh and with God’s making ‘the depths of the sea a way for the redeemed to pass over’ (Is 51:10). For Isaiah, the purpose of these images is to point back to the Exodus and point forward to the new Exodus, the eschatological restoration of Israel in which everlasting peace will reign: ‘And the ransomed of the Lord shall return, and come to Zion with singing; everlasting joy shall be upon their heads’ (Is 51:11). This mystagogical move—leading his audience from God’s past saving act to its full reality in a future, definitive work of redemption—enables Isaiah to center attention upon the fundamental mystery of the saving God who loves Israel: ‘the Lord, your Maker, who stretched out the heavens and laid the foundations of the earth’ (Is 51:13). It is in this context that Israel should understand the judgment that has come upon it in the Babylonian exile. Isaiah states that although this judgment, as ‘the cup of his [God’s] wrath,’ has indeed wreaked ‘devastation and destruction, famine and sword,’ in the near future God’s salvation will lift up his people, and God’s judgment will fall upon his people’s oppressors (Is 51:19). Aquinas understands this promise to be about a literal return from Babylonian exile and a restoration of the actual city of Jerusalem, although he notes that the restoration will also have a moral dimension in that ‘the poor in the land’ will now be cared for. 27 This will be accomplished by God through Cyrus’s command; and punishment will come upon Babylon because of its idolatry and its failure to recognize God’s power to deliver his people. Aquinas interprets Isaiah’s prophecy, ‘for eye to eye they see the return of the Lord to Zion’ (Is 52:8), as meaning not only that the people of Jerusalem will see the captives returning from exile, but also that Jerusalem will put on ‘beautiful garments’ (Is 52:1), namely, good works, virtues, and freedom from worldly care and from sin.28 In commenting upon the first twelve verses of Isaiah 52, Aquinas sticks largely to the historical event of the Persian conquest of Babylon and the return of the exiles due to the command of Cyrus. Yet, Aquinas considers that for Isaiah, this event is a mystagogical preparation for 27 28

Aquinas, In Is cap LII. See ibid.

26

MATTHEW LEVERING

entering into the divine mystery of ‘the deliverance of the nations from slavery to sin, wrought by the Son of God.’ 29 In Aquinas’s view, therefore, Isaiah’s clearest teaching on Christ begins in Isaiah 52:13. Christ will be God’s ‘servant’ in his human nature’; he will be ‘exalted’ in his divine power to work miracles; he will be ‘lifted up’ in his Ascension; and he ‘shall be very high’ when he sits at the right hand of the Father (Is 52:13). Isaiah knows these things because Christ the Mystagogue teaches them to him. By contrast, Aquinas knows them because Jesus Christ has indeed come in the flesh and they have been proclaimed by the Church of which Christ is the living Head. Both Isaiah and Aquinas, however, know not only Christ as ‘lifted up’ and ‘very high,’ but also as teaching the crowds in his public ministry and as marred by his Passion. The people will be ‘astonished’ by Christ’s teaching and miracles, but his appearance will be ‘marred’ by his Passion, and ‘his form’ (Is 52:14) will seem to be ‘without beauty.’30 Leading his audience deeper into the mystery, Isaiah ‘prophesies deliverance’—but not a merely political deliverance and not solely the deliverance of Israel. 31 The deliverance will involve ‘the remission of sins.’32 Aquinas is helped here by the Vulgate translation of a Hebrew verb whose meaning is obscure—translated by the RSV as ‘startle’ (Is 52:15) but by the Vulgate as ‘sprinkle.’ The translation ‘sprinkle’ allows Aquinas to make connections to the forgiveness of sins through baptism, which he links with the cultic sprinkling of the blood of sacrificial animals in covenant renewal (he cites Hebrews 10:22). When Isaiah foretells that ‘kings shall shut their mouths because of him; for that which has not been told them they shall see, and that which they have not heard they shall understand’ (Is 52:15), Aquinas takes this to apply to the conversion of the Gentile nations to Christ.33 Isaiah continues to initiate his audience into the mystery of Christ by probing the depths of Christ’s humility. Christ conceals his divine majesty: ‘he had no form or comeliness that we should look at him’ (Is 53:2). This concealment is meant to draw us into the mystery of God, who comes to us in humility rather than in power. Why is Christ ‘a man of sorrows,’ so much so that he is ‘as one from whom men hide their faces’ (Is 53:3)? In Isaiah 53:4-6 we learn that the servant ‘has borne our griefs’ and ‘was wounded for our transgressions’ and ‘bruised for our iniquities’ 29

Ibid. Ibid. 31 Ibid. 32 Ibid. 33 For a fuller discussion of the themes of this paragraph, see Gregorio Guitián Crespo, La mediación salvífica según santo Tomás de Aquino (Pamplona: EUNSA, 2004). 30

MYSTAGOGY AND INTERPRETING ISAIAH

27

so that ‘upon him was the chastisement that made us whole’ and ‘the Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all.’ In all this, says Aquinas, Christ’s profound humility enables him to reveal the saving ‘arm of the Lord’ (Is 53:1) in conquering sin. Christ also reveals himself to be truly the ‘young plant’ and the ‘root out of dry ground’ (Is 53:2). Aquinas explains that the ‘plant’ is the ‘rod’ by which God conquers, strengthens, and guides his people, as described in various psalms and elsewhere; and the ‘root’ is none other than ‘[t]he root of wisdom—to whom has it been revealed?’ (Sir 1:6).34 This root is the mystery in its greatest depth. As the ‘arm of the Lord,’ Christ scourges the demons, supports the weak, and defends the faithful - and does so by dying for us.35 Aquinas discusses Isaiah 53:4-6 in light of Romans 3:22, Romans 5:10, and 1 Peter 2:24-25. These passages underscore that we are all sinners, deserving of the punishment of death, and Christ freely and lovingly undergoes the penalty of sin (death) for us. Christ undergoes not just any death, but the most shameful death, enduring bitter physical, mental, and emotional suffering. The purpose of this was to restore humans, who had turned away from God and foundered in a state of injustice, to communion with God, so as to make Christ the instrument of ‘an outpouring of graces: from his fullness we have all received grace (Jn 1:16).’36 In Christ, then, who is the humblest and most humiliated of men, the divine mystery of grace—truly efficacious forgiveness for our pride—is present. The cross of Christ leads us into the mystery of divine love. Again, Aquinas thinks that Isaiah, as a mystagogue, knows all this and is initiating his Israelite audience (as well as later believers such as us) into the mystery. He thinks that Isaiah points not only to Christ’s cross but also, in a more veiled way, to the reality of Christ’s resurrection and Christ’s divinity. For example, given that the Vulgate version of Isaiah 53:8 reads ‘he was taken away from distress and from judgment [de angustia et de iudicio sublatus est],’ Aquinas finds in the phrase ‘taken away’ a sign of ‘the resurrection’ of Christ.37 Resurrection takes Christ away from both the distress of death and the mistaken judgment of the Romans and the Jews. Isaiah 53:8 describes ‘his generation, who 34

See Aquinas, In Is cap LIII. See ibid. 36 Ibid. See Mateusz Przanowski, O.P., ‘Formam servi accipiens (Phil 2:7) or Plenus gratiae et veritatis (Jn 1:14)? The Apparent Dilemma in Aquinas’ Exegesis,’ in Towards a Biblical Thomism: Thomas Aquinas and Renewal of Biblical Theology, ed. Piotr Roszak and Jörgen Vijgen (Pamplona: EUNSA, 2018), 119-33. 37 Aquinas, In Is cap LIII. The RSV translation of Isaiah 53:8 reads, ‘By oppression and judgment he was taken away; and as for his generation, who considered that he was cut off out of the land of the living, stricken for the transgression of my people?’ 35

28

MATTHEW LEVERING

considered that he was cut off out of the land of the living.’ Aquinas finds here a veiled reference to the mystery of Christ’s divinity, since Christ’s ‘generation’—in one meaning of the word—is both ‘eternal as from the Father (without a mother), or temporal as from a mother (without a father),’ and both his eternal and temporal natures are important for the redemptive power of his cross, due to ‘the dignity of the one who suffered.’38 In addition, Aquinas sees in Isaiah 53:8, which in his Vulgate version includes the phrase ‘for the wickedness of my people I have struck him,’ a reference to the Father’s permitting Christ to suffer on the cross. The Trinity’s love stands at the center of this mystery, since the Father, Son, and Spirit eternally will that the suffering of the incarnate Son, in solidarity with sinners, should bring about the redemption of humankind.39 Aquinas thinks that a veiled presentation of Christ’s resurrection also appears in Isaiah 53:10-11. In these verses Isaiah prophesies that ‘when he makes himself an offering for sin, he shall see his offspring, he shall prolong his days [Vulgate: ‘he shall see a long-lived seed’]; the will of the Lord shall prosper in his hand; he shall see the fruit of the travail of his soul and be satisfied.’ This certainly seems to be a reference to further earthly life. Yet, how could it be further earthly life if the servant has been ‘cut off out of the land of the living’ and buried (Is 53:8-9)? Even so, it does seem to be a prolongation of earthly life. Aquinas accepts that it is such a prolongation, but in a different sense than—lacking a perception of the mystery—we might suppose. Namely, the risen Christ will see ‘his offspring’ (Is 53:10) since ‘even to the end of the world, sons shall be regenerated to him by the power of his death.’40 In this sense, Christ’s historical act of dying will continue to bear fruit on earth that Christ himself, at the right hand of the Father, will see. Aquinas draws a connection here to Christ’s words in John 12:24: ‘unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it bears much fruit.’41 Similarly, when Isaiah 53:10 states that ‘the will of the Lord shall prosper in his hand,’ Aquinas interprets this verse by recalling Paul’s

38

Aquinas, In Is cap LIII. See my Engaging the Doctrine of Creation: Cosmos, Creatures, and the Wise and Good Creator (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2017), chapter 7, especially my response (admittedly overly brief) on p. 284 n. 35 to the concerns raised by Nicholas E. Lombardo, O.P., The Father’s Will: Christ’s Crucifixion and the Goodness of God (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013). 40 Aquinas, In Is cap LIII. 41 See ibid. 39

MYSTAGOGY AND INTERPRETING ISAIAH

29

teaching that ‘this is the will of God, your sanctification’ (1 Thess 4:3).42 God’s will prospers on earth when believers are sanctified by Christ. Along these same lines, when Isaiah 53:11 teaches that ‘he shall see the fruit of the travail of his soul and be satisfied,’ Aquinas identifies this fruit to be the conversion of the nations. In sum, Aquinas reads the passage that begins at Isaiah 52:13 and continues through Isaiah 53 as teaching about the mystery of Christ. Although Aquinas does not call Isaiah a ‘mystagogue,’ Isaiah’s task as Aquinas understands it is to initiate the Israelites into the mystery of Christ crucified and risen. Along with Christ, the Holy Spirit is the Mystagogue who teaches Isaiah. Just as Isaiah leads the Israelites into the mystery of Christ—a mystery found fully in the New Testament but which is intelligible only in light of the Old Testament—so also in his own day Aquinas, in his commentary, has the mystagogical task of helping to lead those who belong to Christ and who are being sanctified in Christ into Christ’s mystery as taught by Isaiah.43 3.

Aquinas on Isaiah 64-66

Now let me turn to Isaiah 64-66, which, in Aquinas’s view, instructs the Israelites about the restoration of Israel (from Babylonian exile) and about the mysteries of Christ, culminating in the eschatological consummation. Building upon the deeply moving lament found at the end of chapter 63, Isaiah 64 begins with Isaiah’s urgent prayer, invoking God’s aid: ‘O that thou wouldst rend the heavens and come down, that the mountains might quake at thy presence… to make thy name known to thy adversaries, and that the nations might tremble at thy presence!’ (Is 64:1-2). Commenting upon these verses, Aquinas suggests that the prophet has in view the incarnation of the Son of God. Aquinas says that it is ‘as if’ Isaiah is pleading with God ‘that you [God] would lay aside your glory, despising majesty to assume flesh.’44 Aquinas supports this interpretation by citing a similar passage whose mystagogical import leads into mystery of the incarnation: ‘Bow thy heavens, O Lord, and come down!’ (Ps 144:5).45 Aquinas adds that ‘the mountains’ that would quake at God’s presence can be understood to be ‘the mighty and the lofty,’ whom Christ 42

See ibid. See the dissertation of M. H. Guerra Pratas, El valor revelador de la historia según santo Tomás de Aquino (Rome: Athenaeum Romanum Sanctae Crucis Facultas Theologiae, 1990). 44 Aquinas, In Is cap LXIV. 45 See ibid. 43

30

MATTHEW LEVERING

conquers. 46 The trembling nations may similarly refer to the Gentile nations who convert at the preaching of Christ. With regard to Isaiah 64:3—‘when thou [God] didst terrible things which we looked not for, thou camest down, the mountains quaked at Thy presence’—Aquinas recognizes this to be most likely a reference to Mt. Sinai and the Exodus. He suggests that Isaiah is calling upon God to redeem Israel from Babylonian exile just as God redeemed Israel from Egyptian slavery. Commenting on Isaiah 64:5-6, he cites Job twice in describing God’s anger at Israel’s sins; much like Job sitting among the ashes, Israel is in exile. The prophet begs for mercy by reminding God that ‘thou art our Father; we are the clay, and thou art our potter; we are all the work of thy hand’ (Is 64:8). Aquinas recalls a similar use of the clay/potter analogy in Jeremiah 18, as well as Job 10:9, where Job calls upon God to ‘[r]emember that thou hast made me of clay.’ Aquinas notes Isaiah’s appeal to the deplorable state of God’s city Jerusalem, now in ruins, and of God’s own house, the Temple, now burnt down (see Isaiah 64:11). Aquinas places this entire lament, which he perceives to be rooted firmly in Israel’s history, under the sign of Isaiah 64:4, where we read that there is no God but God and that God blesses those who are faithful to him. Aquinas comments that the blessing that God works for his faithful is eternal life. The prophecy of Isaiah thus cannot be simply about the restoration of the kingdom of Israel or of the city of David with its Temple. With reference to Isaiah 64:11’s description of the burntdown Temple as Israel’s ‘holy and beautiful house,’ Aquinas points to Christ’s promise in the Gospel of John about the eschatological ‘house’ of God: ‘In my Father’s house are many rooms; if it were not so, would I have told you that I go to prepare a place for you?’ (Jn 14:2).47 Likewise, quoting from Christ’s eschatological parable of the sheep and the goats, Aquinas states that God gives the blessed ‘a kingdom of eternal honor: come, blessed of my Father, receive the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world (Mt 25:34).’48 Aquinas also associates eternal life with ‘a table of divine refreshment’ and ‘a lamp of everlasting light,’ in both cases citing psalms.49 Aquinas comments upon the temporal rewards that God promises to his ‘servants’ (Is 65:8) by noting that these rewards involve both

46

Ibid. See ibid. 48 Ibid. 49 Ibid. 47

MYSTAGOGY AND INTERPRETING ISAIAH

31

‘preservation from evil’ and ‘encouragement in the good.’50 He thinks of the reward of preservation from evil as encompassing ‘the race of the Jews,’ whom God wills to keep ‘for a blessing.’51 The reward includes ‘the multiplication of their offspring’ and ‘the restoration of their ancestral inheritance.’52 Likewise, commenting on Isaiah 65:11-15 with its portrait of the punishment of the wicked Israelites, Aquinas cites Deuteronomy, Jeremiah, Proverbs, Psalms, and Wisdom. The wicked will suffer in history, and those who are faithful will be rewarded with the end of the Babylonian exile, among other things. Thus, Aquinas does not move too quickly toward the eschatological future. Nor does Isaiah, since Isaiah talks about eating, drinking, singing for joy, blessing God, dwelling in the land with flocks and herds, and other earthly activities. Indeed, Aquinas accepts that Isaiah 65:17 refers to ‘new helps from heaven’ and ‘new favors from the earth’ — in other words, to new earthly flourishing for Israel’s people, crops, flocks, and herds.53 Isaiah 65:17 is often interpreted as an eschatological promise: ‘For behold, I create new heavens and a new earth.’ Aquinas thinks that indeed the verse may lead into the mystery. It may intend to refer to ‘the day of judgment, when the world shall be renewed for the glory of the saints.’ 54 Here Aquinas cites Revelation 21:4-5, and he could equally—or better—have cited Revelation 21:1, ‘Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth; for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea [symbolizing chaos] was no more.’ But in general, Aquinas inclines toward interpreting Isaiah 65:17, and the remainder of Isaiah 65, in terms of earthly restoration and blessing. This may seem surprising, given Aquinas’s insistence earlier that Isaiah knows the mystery of Christ’s cross and resurrection and its saving effects. Yet, it is not surprising given the promise of restoration from Babylonian exile and the earthly images found in Isaiah 65, including God’s rejoicing in the restored condition of Jerusalem and the gift of long life, houses, and vineyards to its inhabitants. When Isaiah says that the returned exiles ‘shall build houses and inhabit them; they shall plant vineyards and eat their fruit’ (Is 65:21), it is no wonder that Aquinas takes this to describe the historical return from exile, even if it also is a sign that leads toward the mystery of eschatological new creation. Aquinas considers that in a ‘mystical’ sense—but not in the literal sense (unlike 50

Aquinas, In Is cap LXV. See also, for the pairing of ‘preservation from evil’ and ‘furtherance in the good,’ Aquinas, STh III, q. 1 a. 2. 51 Aquinas, In Is cap LXV. 52 Ibid. 53 Ibid. 54 Ibid.

32

MATTHEW LEVERING

the passages about Christ in Isaiah 52-53, which Aquinas read in the literal sense)—Isaiah’s prophesy that there shall not be ‘an old man who does not fill out his days’ will be fulfilled in the eschatological ‘heavenly Jerusalem,’ where ‘all their days shall be fulfilled, for none shall die.’55 Even the final verse of Isaiah 65, an eschatological verse if there ever was one—‘The wolf and the lamb shall feed together, the lion shall eat straw like the ox; and dust shall be the serpent’s food. They shall not hurt or destroy in all my holy mountain, says the Lord’ (Is 65:25)—receives a temporal interpretation from Aquinas. He interprets the wolf and the lamb feeding together to mean simply that ‘those who had previously been tyrants and evildoers shall dwell with others in peace.’56 This pattern continues in his commentary on chapter 66, Isaiah’s final chapter. Chapter 66 opens with the Lord’s words that he is the Creator of all and that his blessing will be bestowed upon a person who ‘is humble and contrite in spirit, and trembles at my word’ (Is 66:2). With regard to the Lord’s words about his creative power and his transcendent claim upon all things, Aquinas takes the opportunity to offer some metaphysical clarifications regarding the Creator-creature distinction. God ‘fills all things’ rather than being confined to one Temple, and creatures ‘participate in his goodness.’ 57 Here Aquinas cites some instructive passages from the Old and New Testaments about God’s relation to the Temple: 1 Kings 8:27, Jeremiah 23:24, and Acts 17:24. Isaiah 66:3-5 describes God’s rebuke of sinners who pretend to honor him while at the same time committing idolatrous abominations. In commenting on these verses, Aquinas sticks to the Old Testament, rather than drawing upon the New for support. Beginning in verse 7, Isaiah 66 turns to the blessings coming upon the righteous Israelites, above all, the restoration of the exiles to Jerusalem. Here Aquinas offers a ‘mystical’ interpretation. Commenting upon Isaiah 66:7, ‘Before she was in labor she gave birth; before her pain came upon her she was delivered of a son,’ Aquinas does not think that Isaiah intends literally to teach Mary’s painless and miraculously virginal childbirth. But he states that ‘[m]ystically, this is understood of the labor of the Blessed Virgin, and of the labor of the Church in the conversion of the faithful’ through which children of God are born spiritually.58 With regard to the literal meaning of the text, does Aquinas still think that Isaiah, in these two final chapters, is initiating God’s people 55

Ibid. Ibid. 57 Aquinas, In Is cap LXVI. 58 Ibid. 56

MYSTAGOGY AND INTERPRETING ISAIAH

33

into the mystery of Christ? Certainly, Aquinas’s mystagogical task here requires more effort than he needed for Isaiah 52-53. It is his task to read the Old and New Testaments together and to show how the whole of Scripture teaches about the mystery of Christ. To accomplish this task, Aquinas more frequently has to read the text of Isaiah ‘mystically’—an approach that, after all, befits the labor of a mystagogue, and that requires being taught by the Spirit (and by the risen Christ). Even so, Aquinas still sees important glimmers of the mystery in the literal sense of Isaiah’s own prophecy. As noted above, he allows that Isaiah 65:17 may refer to the eschatological consummation in Christ. Similarly, when commenting on Isaiah 66:9, ‘shall I bring to the birth and not cause to bring forth?’ (in the Vulgate version, ‘shall I not myself bring forth?’), he suggests that this bringing forth may be the act of ‘gathering the Jews and converting the faithful’ and may even have to do with the eternal generation of the Son.59 The work of ‘gathering the Jews’ has an eschatological resonance to it, and Aquinas notes that God ‘promises immeasurable consolation to those who are gathered.’60 Regarding this ‘immeasurable consolation,’ Aquinas cites eschatologically resonant passages from Song of Songs, the Gospel of Matthew, and Job. Aquinas includes in the literal sense of Isaiah 66:10-14 ‘participation in glory,’ ‘an overflowing bestowal of peace,’ ‘a full reception of comfort,’ seeing ‘the good things given by God,’ seeing ‘the divine essence,’ and living ‘in the resurrection.’ 61 Thus, for Aquinas, Isaiah the mystagogue has a clear perception of the components of eternal life in Christ. Isaiah 66:10-14 describes the triumphant restoration of Jerusalem, so that its people ‘may drink deeply with delight from the abundance of her glory’ (Is 66:11) and so that ‘[y]ou shall see, and your heart shall rejoice; your bones shall flourish like the grass’ (Is 66:14). Rather than simply applying this to the Jews’ return from Babylonian exile, Aquinas argues that Isaiah has in view the eschatological Jerusalem. Aquinas also notes that the images of Jerusalem receiving the ‘wealth of the nations’ (Is 66:12) and of Jerusalem as a mother who nourishes and cares for her children can mystically be applied to the work of the apostles who bring the nations to Jerusalem.62 Aquinas continues this approach in commenting upon Isaiah 66:15-16, which describe the day of the Lord’s wrath against sin: ‘For behold, the Lord will come in fire, and his chariots like the storm-wind, 59

Ibid. Ibid. 61 Ibid. 62 Ibid. 60

34

MATTHEW LEVERING