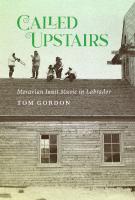

Called Upstairs: Moravian Inuit Music in Labrador 9780228018353

A story of cultural agency and the emergence of Inuit voices across 250 years of a musical tradition. Called Upstairs

110 84 19MB

English Pages [461] Year 2023

Called Upstairs: Moravian Inuit Music in Labrador

Cover

Half Title Page

Series Editors

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Contents

Preface: Called Upstairs

Acknowledgments

Audio Examples and Musical Scores

Chapter 1: Backstories

Chapter 2: Hymns from a Feeling Heart

Chapter 3: “The Seed of Music Takes Root”

Chapter 4: Trumpets on the Roof

Chapter 5: Taima … Nala …: Music and Leadership

Chapter 6: Reading by Ear: Memory, Literacy, Aurality, and Transmission

Chapter 7: The Inuit Voice in Moravian Music

Glossary of Musical Terms

Tables and Figures

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Tom Gordon

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

c a l l e d u p s ta i r s

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 1

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

McGill-Queen’s Indigenous and Northern Studies (In memory of Bruce G. Trigger)

John Bor rows, Sar ah Carter, and Arthur J. R ay, Editors The McGill-Queen’s Indigenous and Northern Studies series publishes books about Indigenous peoples in all parts of the northern world. It includes original scholarship on their histories, archaeology, laws, cultures, governance, and traditions. Works in the series also explore the history and geography of the North, where travel, the natural environment, and the relationship to land continue to shape life in particular and important ways. Its mandate is to advance understanding of the political, legal, and social relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, of the contemporary issues that Indigenous peoples face as a result of environmental and economic change, and of social justice, including the work of reconciliation in Canada. To provide a global perspective, the series welcomes books on regions and communities from across the Arctic and Subarctic circumpolar zones.

96 Plants, People, and Places The Roles of Ethnobotany and Ethnoecology in Indigenous Peoples’ Land Rights in Canada and Beyond Edited by Nancy J. Turner 97 Fighting for a Hand to Hold Confronting Medical Colonialism against Indigenous Children in Canada Samir Shaheen-Hussain 98 Forty Narratives in the Wyandot Language John L. Steckley 99 Uumajursiutik unaatuinnamut / Hunter with Harpoon / Chasseur au harpon Markoosie Patsauq Edited and translated by Valerie Henitiuk and Marc-Antoine Mahieu 100 Language, Citizenship, and Sámi Education in the Nordic North, 1900–1940 Otso Kortekangas

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 2

101 Daughters of Aataentsic Life Stories from Seven Generations Kathryn Magee Labelle in collaboration with the Wendat/ Wandat Women’s Advisory Council 102 Aki-wayn-zih A Person as Worthy as the Earth Eli Baxter 103 Atiqput Inuit Oral History and Project Naming Edited by Carol Payne, Beth Greenhorn, Deborah Kigjugalik Webster, and Christina Williamson 104 Ǫ da gaho dḛ:s Reflecting on Our Journeys Gae Ho Hwako (Norma Jacobs) and the Circles of Ǫ da gaho dḛ:s Edited by Timothy B. Leduc 105 Called Upstairs Moravian Inuit Music in Labrador Tom Gordon

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

Called Upstairs

Moravian Inuit Music in Labrador

Tom Gor don

McGill-Queen’s University Press Montreal & Kingston | London | Chicago

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 3

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

© McGill-Queen’s University Press 2023 ISBN 978-0-2280-1677-9 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-2280-1678-6 (paper) ISBN 978-0-2280-1835-3 (ePDF) Legal deposit second quarter 2023 Bibliothèque nationale du Québec Printed in Canada on acid-free paper that is 100% ancient forest free (100% post-consumer recycled), processed chlorine free This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts. Nous remercions le Conseil des arts du Canada de son soutien. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Title: Called upstairs : Moravian Inuit music in Labrador / Tom Gordon. Names: Gordon, Tom, 1946– author. Series: McGill-Queen’s indigenous and northern series ; 105. Description: Series statement: McGill-Queen’s Indigenous and Northern series ; 105 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 2023013176X | Canadiana (ebook) 20230131778 | ISBN 9780228016779 (cloth) | ISBN 9780228016786 (paper) | ISBN 9780228018353 (ePDF) Subjects: LCSH: Moravian Church—Newfoundland and Labrador—Labrador—Music. | LCSH: Inuit—Newfoundland and Labrador—Labrador—Music. | LCSH: Missions— Newfoundland and Labrador—Labrador. Classification: LCC ML3172 .G662 2023 | DDC 781.71/460097182—dc23

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 4

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

Dedicated to the memory of Karrie Obed (1959–2017) Inuk, Teacher, Musician

d

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 5

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 6

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

Contents Preface: Called Upstairs

ix

Acknowledgments

xxi

Audio Examples and Musical Scores

xxv

1 Backstories

3

2

Hymns from a Feeling Heart

3

“The Seed of Music Takes Root”

109

4

Trumpets on the Roof

167

5

Taima … Nala …: Music and Leadership

227

54

6 Reading by Ear: Memory, Literacy, Aurality, and Transmission

271

7

The Inuit Voice in Moravian Music

297

Glossary of Musical Terms

345

Tables and Figures

351

Notes

357

Bibliography

399

Index

413

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 7

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 8

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

Preface m Called Upstairs I was around thirteen years old when they told me to – when one of the chapel servants told me to go upstairs in church. I think it was on Easter. Easter morning. It was on a Sunday, I think.1

Aside from the fact that he was only thirteen years old when he was called “upstairs,” tenor Karrie Obed’s invitation to join the Nain choir followed a protocol that had been in place for close to 150 years. His was a calling in both the literal and the altruistic senses of the word. A calling to play a vital role in the spiritual and celebratory life of his community; a calling to be a steward of a unique tradition; a calling to leadership both in the choir loft – upstairs – and in the community as a whole. Soprano Mary Andersen referred to it as “being elected in.” Bass Julius Ikkusek declined his call several times for fear that he couldn’t live up to the standard of conduct required. When he finally answered the call in his late twenties, he knew he had to live a life equal to the station. For the next fifty-plus years he would be a mentor, a model, and a leader, as well as a bearer of a musical tradition that had come to represent Inuit of Labrador. Admittedly a colonial imposition from the arsenal of Christianizing tools brought by Moravian missionaries, this tradition of choral and instrumental music would become a beloved symbol of community, a vehicle for spiritual and aesthetic expression, and, perhaps ironically, an instrument for Inuit agency. This tradition is most tellingly explored through the stories of those who received “the call” – that is, the lives and achievements of those musical stewards who provided leadership not only in the choir loft and the band but also in the community as a whole. For most of a century the story of that developing tradition was recorded largely by the colonizer, the Moravian missionaries. Inevitably these early versions of the stories were coloured by the missionaries’ viewpoint. In the later nineteenth century, the teller of the stories gradually shifted from the missionaries to Inuit musicians themselves. Only then did Inuit perspectives start to emerge clearly. With the emergence of Inuit voices the tradition itself began its transformation from a foreign artistic and spiritual practice into a cultural expression reflecting Inuit aesthetic, spiritual, and communal values.

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 9

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

pr e fac e

x

Just as the Moravians could not escape their own objectives and the assumptions that informed them as they chronicled the story of Inuit Labrador, I too must acknowledge that I have inevitably brought my own assumptions to this telling. I am a white male, an academic trained in historical musicology, and a competent keyboard player. I am fully aware that this is not my story. I believe it would be better told by an Inuk musician and steward of this tradition. Sadly there are few left to tell their story. Over the twenty years since I first began research on Moravian music in Labrador, many of the stewards of this tradition have died. Much of their knowledge and many of their stories have passed with them. I have concluded that if this compelling story of adaptation, agency, and the power of cultural expression is to be recognized, I must share what I’ve learned. While much of the documentation of this tradition was produced by the missionaries, I believe that my understanding of it has been shaped by the extraordinary musicians who determinedly maintained the tradition across the first two decades of the twenty-first century. In order to contextualize my understanding, I will insert myself here briefly. As a meat-and-potatoes music historian, I like paper. I trust it. Over time it gives off clues that figure and then reconfigure in my mind. I cut my research teeth in the Stravinsky archives tracing circuitous routes through his sketchbooks, puzzling over how he got to the avant-garde discoveries of his early twentieth-century masterworks. So it’s no surprise that, when I stumbled upon a cache of some 20,000 unexamined pages of music manuscript on the north coast of Labrador, I felt a sense of new purpose entering my life. Those sheets of paper comprise the repertoire of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century choral anthems introduced to Labrador Inuit by Moravian missionaries early in the nineteenth century. Within half a century the students became the mentors and the choir lofts in Nain, Hopedale, Hebron, and Okak had become the domain of Inuit organists and choirmasters. These skilled musicians assumed responsibility for the annual cycle of sung anthems originally penned in faraway Europe by composers like Mozart, Haydn, and Mendelssohn, together with a legion of lesser-knowns. These same Inuit musicians also became the scribes for this repertoire, copying and recopying the choral and orchestral parts when original copies wore out. The story of Inuit agency in the shaping of the performance practice of this music is one that revealed itself across those sheets of paper. What the copyists transcribed was the music as performed, not as originally written. And what was performed increasingly distanced the music from its European sources to an essential form that reflected Inuit aesthetic values. For almost a decade I spent several weeks each summer digitizing and cataloguing these sheets of paper. My summer “digitizing holidays” in the North

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 10

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

xi

pr e fac e

also introduced me to the people who remain the stewards of these sheets of paper. They were naturally curious – and not a little apprehensive – about what I was doing. I found myself drawn slowly into relationships with them. Fixated as I was on the paper, it belatedly dawned on me that I might learn more from the musicians who continued to use that paper – the organists, choristers, and violinists who maintained the tradition of performing from these manuscripts. And after years of seeing me arrive in town, root around in their choir lofts, and enthuse about what I was seeing, these Inuit musicians began to wonder if there mightn’t be something I could do to assist them in maintaining traditions that were being threatened. Cautiously we started collaborating. First, they gently corrected my gaze, which was focused on the “art music” part of the repertoire almost to the exclusion of what to them was its core: the ancient hymns sung congregationally in four-part harmony. Most importantly, they pried me away from the paper and toward their voices, reminding me that the music was in what was sung, not in what was on the paper. While the urge to document and perform my little forensic experiments on the paper never vanished, I began to shift my attention to this music as a practice. It meant sitting in the congregation through dozens of sung services: listening, recording, reflecting on what I heard both from the choir and from the congregation. It meant combing the audio archives of the local radio station, where Moravian hymns continue to top the charts – the most requested genre on call-in shows. With guidance from my more experienced colleagues, I developed an approach to an ethnographic study in what had by now become Nunatsiavut – the self-governing Inuit territory of Labrador. I prepared for a four-month residency in Nain, the northernmost Labrador Inuit community and the one with the most active continuing musical traditions. I timed my residency so that it would coincide with the musically rich seasons of Advent and Christmas. The first pillar of the methodology was to be interviews, and I developed a series of questions for Inuit musicians and church leaders aimed at defining musical preferences, transmission practices, music literacy, training, and the meaning and impact of the music. The second pillar of my methodology was observation. I had become a churchgoer of unprecedented faithfulness and was no less regular in attending community celebrations and feasts. After each event I dashed back to my laptop and set down my observations and reflections. Fortunately the length of my residency was making me a fixture in the community. After the last boat left and I was still there I started becoming part of the landscape. My uncanny resemblance to another jolly-shaped, silverbearded white guy as Christmas approached lent me an undeserved popularity at December community gatherings. That’s when my own “call upstairs” came.

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 11

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

pr e fac e

x ii

Starting from the rehearsal for the first Sunday in Advent, I joined the choir as an apprentice in the bass section, alongside the Elder Julius Ikkusek. For the next two months I learned from him and the other senior members of the choir. It was really only after I’d been called upstairs that the more insightful answers to my awkwardly formed interview questions and the meaning of my observations started to come into view. Julius took his role as mentor seriously, and I found myself in the position of choir apprentices from generations long ago. I learned the same way he had learned. Julius assumed that I did not read music, and indeed, I did not read music in the way that he and the other members of the choir did. At each rehearsal and service I stood close by Julius, holding the manuscript score from which both of us would sing. With his right hand Julius would finger the notes as he sang them into my ear. With his left hand he counted the beats – every beat. I learned that music reading in the Nain choir was a hybrid affair: pitch might be suggested by the contour of the line on the page but was largely a function of aural memory; rhythm was read – with great concentration. In addition to learning to read music experientially, my apprenticeship provided me with a deeper understanding of the aesthetic preferences of Inuit musicians. As we rehearsed one anthem or another, choir members freely exchanged observations. Elaborate, ornamented baroque anthems and arias in minor mode were described by Beni Ittulak, the choir’s lead soprano, as “right German” – a derogation seconded by other choir members. At the same time, classic arias from the age of Mozart, set in a high tessitura, unrelentingly tonal and repetitive, were singled out as favourites. So too were mid-nineteenthcentury anthems in the style of Mendelssohn. The warmest feelings were reserved for the sentimental concoctions of the Victorian hymnodists, collectively referred to as “Sankeys.” A patchwork of tastes emerged, one that sanctioned simple textures in major mode and straight-ahead rhythms, rooted in ancient Moravian chorales. When a more complex composition garnered favour, its performance practice stripped it of excess vocal embellishment and reduced rhythmic complexity to its lowest common denominator. My paper trail discoveries were being corroborated by current practice. The copyists’ recomposition was indeed a reflection of aesthetic preference. A few days after Nalujuk’s Night,2 I returned south. By that time, I had established relationships with many of the musicians on the Labrador coast. Both during our formal interviews and in less formal interactions, many expressed concerns about the future of their tradition. The brass bands had already died out in all the Nunatsiavut communities. Only the Nain choir continued to perform the entire cycle of Moravian anthems, and few members

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 12

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

x iii

pr e fac e

of that ensemble were under the age of sixty. Was there anything we could do together to secure its future? Our first response was to try to document the tradition in a way that would be meaningful to the Inuit musicians and their communities. I approached Nigel Markham, a filmmaker with a thirty-year history of making thoughtful and reflective films in the North. After a series of community consultations, we developed a project to film the Inuit musicians of the Labrador coast during Passiontide and Easter of 2011. Into the mix we added a group of graduate students and recent graduates, whom the Inuit musicians mentored in their musical traditions. Elders were able to exercise their roles as transmitters of tradition. The lead singers of the Inuit choirs were able to perform with augmented resources. There were opportunities to reflect. The experience was exhilarating at every level. Before releasing Till We Meet Again: Moravian Music in Labrador, we undertook a screening tour of the communities where the film had been shot. Our goal had been to turn a mirror on a tradition before it died. In the town hall forums that followed the screenings, we found we had accomplished much more. In each community, the conversations following the screening followed three paths: a deep sense of pride in the recognition that extraordinary musicians were living in their communities; an understanding that this music – foreign though it may have been in its origins – was a product of their own creative activity; and a desire to rescue these traditions before they were lost forever. Establishing as a first goal the revival of the brass bands was easily agreed upon. Their absence was sorely felt in each community. The bands had played a ceremonial role in calling the people together on occasions of celebration; they were a symbol of community. There was also the pragmatic consideration that these bands’ historical repertoire – four-voiced chorales – would be mastered with relative ease, even by beginners. It looked like a feasible “win.” With the goal set, Tittulautet Nunatsiavuttini – Nunatsiavut Brass Bands3 was created with the object of reviving brass bands in Nunatsiavut communities. In August 2013, twenty-four aspiring brass band players from all Nunatsiavut communities gathered in Hopedale for a week-long intensive brass band workshop with facilitators who had already participated in the film project. The participants ranged in age from thirteen to well over fifty and everything in between. By week’s end they were ready for a concert of Moravian melodies in which all twenty-four participants played. At the end of the workshop, each community took home a quartet of new instruments as part of a grant from the International Grenfell Association. A group website offered lively exchange throughout the fall, and scores for Christmas repertoire were exchanged. Around the holidays, posted pictures

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 13

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

pr e fac e

x iv

and short videos documented each community’s Christmas performance. The following Easter at 5:30 in the morning, the Nain Brass Band greeted the rising sun from the village cemetery, reviving a centuries-old tradition that had been abandoned twenty years before. Workshops continued in each of the following two years. In the summer of 2014, five members of the Nain Brass Band travelled to Herrnhut, Germany – the world headquarters of the Moravian Church – to participate in an international Moravian Brass Band Festival. It was the first time in 250 years that Inuit had travelled to the mother church. Two years later the band recorded, edited, and released its self-titled cd.4 In the years since, there’s scarcely a gathering or community event in Nain today that doesn’t feature the band as a musical emblem of people coming together. Over the past few years we’ve collaborated to issue three more recordings of new and archival performances by Inuit musicians.5 In the fall of 2019 a new community initiative, Community Music Literacy in Coastal Labrador, was launched to train new organists, choir members, and instrumentalists. The Covid-19 pandemic threw a wrench in the roll-out of this project; however, by early winter 2021 online workshops had engaged participants from all four Moravian Inuit communities in Labrador. The slowdown in active engagement wrought by the pandemic also provided me with the opportunity to reflect on what I had learned about Moravian Inuit music and the various ways in which I had learned it since I was first seduced by the prospect of unlocking the mysteries of those music manuscripts almost two decades ago. What began as an archival documentation project has morphed into something else. In a very real sense it has crossed the border into something that looks and feels more like a collaboration for community engagement. But in a no less real sense I feel as though I’ve gained a deeper understanding of Moravian Inuit music through each of these experiences – an understanding that the paper alone, however cool and empirical it might be, could never have brought me. The result is this book. The book has three sections. The first chapter lays out the backstories of Labrador Inuit, the Unitas Fratrum (commonly known as the Moravian Church), and the point at which their stories intersect, a series of first encounters that led to an intermingled history of now more than 250 years. It concludes with an overview of some of the lasting consequences of what was a colonial relationship. The subsequent three chapters examine the origins and development of the three principal genres of music that would become the core of Moravian Inuit music in Labrador. Chapter 2 explores Labrador Moravian hymnody, a repertoire of more than 1,200 hymns sung in four-part harmony in Labrador Inuktitut. Initially drawn from the voluminous corpus of chorales in the

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 14

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

x v

pr e fac e

Protestant tradition, as sanctioned and codified by the Moravians over the course of the eighteenth century, the Labrador Inuktitut hymn repertoire was expanded with the addition of a large number of evangelical hymns known as “Sankeys” beginning in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The story of Labrador Inuit hymnody will be traced along the trajectories delineated by handwritten and printed hymnals from 1780 to 2005, as well as through observations about and reflections on hymn-singing made by Inuit, Moravians, and others who witnessed the tradition evolve over the same period. The emergence of a tradition of choral anthems sung by trained choirs with soloists and accompanied by string players and organ is taken up in chapter 3. This is a story told first in the letters and reports of missionary mentors across the nineteenth century, but more concretely documented in approximately 20,000 pages of music manuscripts held in the choir lofts of churches in Nain, Hopedale, Hebron, Makkovik, and Okak. These manuscript sheets chart not only the arrival and introduction of a tradition of concerted choral singing, but also, and even more significantly, the transformation of the imported choral music from its European sources into an expression of Inuit cultural identity. Chapter 4 relates the story of the arrival in Labrador of the distinctive Moravian tradition of brass bands as a public and extra-liturgical expression of Christian faith. By the middle of the nineteenth century Inuit musicians had adopted the practice of playing four-part chorales out-of-doors to summon the community to festival celebrations. The Labrador bands also participated in the Moravian traditions of announcing the Resurrection in the graveyard at sunrise on Easter Sunday morning and raucously welcoming the New Year at the midnight Watchnight service. And they would “play in” the arrival of visitors by ship and “play out” their departure, as well as play to celebrate an Elder’s auspicious birthday. Over time, the brass band became the voice of the community, heralding key moments of Inuit life along the northern coast of Labrador. Chapters 2 to 4 are inevitably shaped by Moravian documentary sources. It is difficult to escape the colonial hand and eye when recounting how missionaries introduced the music for the first hundred years. Missionaries oversaw the establishment of Moravian music traditions. They chose the genres and repertoire and dictated their uses. They acquired and distributed musical instruments. They taught Inuit to sing in harmony, to play the organ or the trombone. They were the curators and mentors of an imposed tradition. However, by the last quarter of the nineteenth century, a shift was taking place in the stewardship of the music traditions introduced by the Moravians. By the 1870s and 1880s, Inuit organists, choristers, band leaders, and musicians not only had acquired a mastery of these music traditions but also had begun

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 15

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

pr e fac e

xvi

to assume autonomy over them. Chapters 5 to 7 refocus the discussion from the introduction and development of the tradition in the hands of missionaries to its reconceptualization and transformation by Inuit musicians. The result is an expressive form that can no longer be heard as European, but rather is an expression of Inuit cultural identity. Chapter 5 focuses on Inuit leadership itself, specifically leadership first assumed at the organ bench, in the choir loft, and from within the band. Many of the music leaders from the end of the nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth assumed broader leadership roles across their communities. Theirs was an organic type of leadership, emerging through a communal acknowledgment of competence and growing by consensus. The authority for this form of leadership was seated in the community. It contrasted and often conflicted with the leadership model encouraged by the missionaries, which had been delimited by Christian moral principles and was inevitably hierarchical. I elaborate on the Inuit form of leadership in this book by sketching the profiles of a number of musician/leaders. Some largely conformed to missionaries’ expectations; others rebelled against them. Most found a personal path that upheld their integrity as Inuit while mediating the requirements of leadership imposed by colonialism. All found ways to repurpose their experiences as leaders within the microcosm of the choir or the band to serve their communities in other, often critical ways. Inuit traditions of oral transmission are counterpointed in chapter 6 with the missionaries’ introduction of a written form of Inuktitut and their encouragement of literacy. The well-practised memories of storytellers and an aural acuity that allowed Inuit to quickly master European music were exploited by the Moravians as they introduced their music traditions. While the vast repertoire of Moravian hymn tunes could be acquired by rote, the more complex repertoire of anthems required the ability to read musical scores. Having been nurtured among choir members and instrumentalists during the middle half of the nineteenth century, the ability to read music was embraced selectively and pragmatically by Inuit musicians. Under the mentorship of Inuit organists and bandleaders, a hybridized form of music literacy evolved in the twentieth century. This genre of reading music “by ear” came to represent further evidence of Inuit agency and ownership of their adopted practice. Once Moravian music had become the “soundtrack” to Labrador Inuit settlements, once it had become integrated into the rhythm of daily domestic life, once it had come under the stewardship of Inuit music leaders, once its continuance came to rely on the mentorship of Inuit master musicians, a distinctly Inuit Voice could be observed in Moravian music as practised in Labrador. The final chapter considers how Inuit musicians have imbued this music with their own

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 16

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

x v ii

pr e fac e

voices. Even as they conserved an adopted tradition, Inuit musicians exerted agency in reconceptualizing this received music to reflect their own musical and aesthetic sensibilities in the way they reinterpreted and performed it. This agency that can be heard (and seen) in the handful of works composed by Inuit musicians in the Moravian style. It is equally evident in the many Moravian works recomposed by organists, instrumentalists, and choirmasters across a century and a half of practice. This Inuit Voice in Moravian music is ultimately defined across five broad categories, which can be summarized as follows: a pure and powerful vocal timbre, a reduction of the musical object to its essence, an attraction to harmonic resonance, the creation of a kind of temporal stasis, and a foregrounding of narrative qualities in the music. Many of these characteristics echo traits that were already present in Inuit music before the time of contact with the Moravians. Ultimately, the purpose of creating and expressing community links the music practices of Labrador Inuit across pre-contact and Christian periods. I hope this book will be of interest to a wide readership among Inuit and Indigenous people and their allies, as well as among researchers across a breadth of fields ranging from anthropology to Indigenous studies to music and ethnomusicology. In the interest of attracting a wide readership, I have chosen, as much as possible, to maintain an approach similar to storytelling. So the narrative that follows is not suffused with critical theory. My goal here has not been so much to interpret as to allow the story to tell itself, although my own conclusions about what this story means are inescapable. Also, in the interest of keeping the discussion accessible to people with diverse backgrounds, I have tried to avoid excessively technical discussions of the music. Some music analysis has been essential to delineate the Inuit Voice, particularly in discussions in chapter 7. With these technical discussions, I have attempted to make clear the impact and meaning of the analytical detail as it defines Inuit agency in reshaping Moravian music. Inevitably I use some terms that are not part of common parlance that are useful in describing music and musical structures precisely. Where these terms are specific to the immediate discussion (e.g., katatjaq or Singstunden), I have defined them where they occur. For more generic musical terms (e.g., metre, polyphony, etc.), I have supplied a brief glossary. My sources for constructing the story of Moravian Inuit music have included archival and documentary materials as well as interviews with tradition-bearers, oral traditions, observation, and participant-action research. The principal documentary sources consulted were produced by the Moravian Church, especially by its London-based missionary arm, the Society for the Furtherance of the Gospel (SFG). The Moravians and the SFG documented their

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 17

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

pr e fac e

x v iii

mission activity voluminously in various publications, the most important of which is the Periodical Accounts,6 which was issued continuously from 1790 to 1970. While I have quoted extensively from the Periodical Accounts, the bias of the source must be kept front and centre. Missionaries’ reports and letters about their activities in Labrador and other fields have been told exclusively from their own perspective. Their unquestioned certitude in the value of bringing Christianity to Inuit informs every word they set to paper. The moral superiority assumed by the Moravians often (but not always) is reflected in language that reveals a paternalistic and patronizing attitude toward Inuit among some of the missionaries. Similarly, it must be acknowledged that the sfg’s underlying motivation in publishing the Periodical Accounts was obviously, if tacitly, to attract financial support for its mission activities. Substantially more than a grain of salt needs to season many of these accounts. Nevertheless, I felt it was useful to cite these original sources extensively and without mediation. I have not repeated identifications of bias or cultural insensitivity in presenting these citations. I trust the reader to recognize the bias in language and the underlying assumptions it betrays. While my principal documentary resource has been the Periodical Accounts, I have been fortunate to have access to some primary source materials in the Moravian archives in Herrnhut, Germany, and Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Access to these materials would have been impossible without the unstinting support provided by my colleague Dr Hans J. Rollmann, whose encyclopedic knowledge of the Moravian record as it pertains to the Labrador missions is equalled only by his generosity in sharing his knowledge. Additional information has been incorporated from other mission publications, including the Nachrichten aus der Brüder-Gemeine,7 Moravian Missions,8 and Labrador Moravian – Moraviamiut Labradorime.9 Nevertheless, the primary source for this study is the music itself, both in the form of the approximately 20,000 pages of handwritten music manuscripts contained in the choir collections in Nain, Hopedale, and Makkovik and in the 500 or so audio recordings I have been able to access in the archives of the Oĸâlaĸatiget Society in Nain and several private collections. This material told its own story objectively and with revealing detail. In addition to the information revealed by successive generations of music manuscripts, the bounty of marginal notes in printed hymnals, scraps of paper containing service orders, orphaned instruments in cupboards – all these brought insights into the lives this music lived. The audio recordings, of course, gave voice to what notations on paper could only suggest. These audio recordings sounded the reality of the music, at least as it has lived across the last seventy years, and

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 18

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

xix

pr e fac e

echoed with a far more distant past. Those echoes, together with a substantial archive of photographs maintained by the Moravians,10 other visitors to the coast, and Inuit photographers themselves, provided the first point of access to the people who maintained this tradition. It was those people and the privilege of coming to know them over two decades that has most profoundly shaped my understanding of Moravian Inuit music in Labrador. They shared their understandings of, experiences in, commitment to, and love for this music in the course of numerous interviews and informal exchanges. I was able to supplement the insights they shared with a large collection of oral histories, particularly those in the invaluable quarterly publication Them Days.11 During extended residencies in Makkovik, Hopedale, and especially Nain, I was able to observe Labrador Inuit making music together and to observe the role this music played in community life. I experienced this as I stumbled behind the brass band in the snow in the pre-dawn of Easter Sunday morning or when pulling out all the stops on the organ at precisely midnight on 31 December to jolt the congregation awake to welcome the New Year with a boisterous rendition of “Jêsus tessiunga.” I learned the most in the projects we undertook together: documentary film and recordings, workshops, development of online resources. Called participant-action research in academic circles, these were in reality community initiatives to which colleagues and I were able to bring supportive resources. What we were able to contribute to these projects was minuscule compared to what we have taken away as understanding of this music and its meaning and importance in the lives of many Labrador Inuit. Finally, it is important to acknowledge that between the time the research for this work was begun (in 2003) and now, Labrador Inuit have achieved full self-determination. Indigenous title was affirmed in an agreement between Nunatsiavut and the governments of Canada and Newfoundland and Labrador on 1 December 2005. This was a proud and noble achievement, the result of the persistent and focused efforts of Labrador Inuit across more than forty years of negotiations. Part of that process entailed civil action against the Moravian Church, which held historic title to vast parcels of Inuit land, including most of the settled communities. In the course of these long-fought legal battles, the church’s role in the colonization of Labrador Inuit was seen by many as detrimental to Inuit agency and culture. The church’s participation in the forced resettlement of communities like Hebron and Okak and its role in establishing and administering residential schools compounded justified sentiments among many Labrador Inuit that it had been an oppressive force in their society that had done irreparable harm to countless individuals and communities. A decade and a half have passed since the creation of Nunatsiavut. As the now fully

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 19

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

xx

pr e fac e

functioning Indigenous government is approaching its early maturity and as distance grows from many of the painful realizations that surrounded the march to self-determination, some of the legacies of the 250 years of the Moravian presence in Inuit Labrador are becoming easier to acknowledge and accept. These include language preservation, universal literacy, leadership development, and music. For many Nunatsiavummiut, their Moravian faith and the traditions and practices that support it remain defining elements of their identity.

c It is necessary to include a word about usage. I have maintained the original vocabulary and orthographies in all citations. This includes the term “Eskimo” (and “Eskimoes” or “Esquimaux”), which was universally used to refer to Inuit until the latter half of the twentieth century. The term is a vestige of the colonial process of naming people, as well as an offensive misnomer that has been denounced by Inuit. In the citations, there are occasional uses of derogatory colonial labels like “pagan” and “heathen.” I have maintained all original uses so as not to disguise the bias embedded in the citation. In my own writing I have endeavoured to use respectful terminology, adhering to contemporary style guides for Indigenous writing.12 Orthography is a complex issue here, beginning with the word for the language of Inuit. Throughout I have employed the standardized English spelling “Inuktitut,” which is also currently used by the Nunatsiavut government. Labrador Inuktitut as a written language was initially devised by Moravian missionaries. Prior to their arrival, no written form of the language existed. As they had done previously in Greenland, the missionaries transcribed Inuktitut as they heard it. What they heard was filtered through their phonetically conditioned ears as (mostly) native speakers of German. Not until well into the Moravians’ second century in Labrador did any of the missionaries have linguistic training. They sometimes heard consonants that didn’t exist (especially “r”). They also heard variants of vowel sounds that may have been more imagined than real. With few exceptions, I have used the orthography as found in my sources. This can result in multiple spellings of the same name or title within a single paragraph. The notation [sic] is used sparingly, chiefly in cases where confusion might appear. Although there is, at present, a strong movement to harmonize Inuktitut writing systems across the circumpolar world, standardized orthography remains a work in progress even within Labrador Inuktitut itself, let alone across the numerous regional dialects of the Inuit Nunangat.

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 20

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

Acknowledgments The story told on these pages belongs to those who told it to me, to those who shared their knowledge and experience, and to those whose generosity permitted me to learn from observing and participating with them in making their music. Among these I am most especially indebted to the stewards of the Moravian Inuit music tradition whom I met and have collaborated with over the past many years. These include all the members of the Nain choir, but most particularly the late tenor Karrie Obed, who opened my ears through his performances and my heart through his friendship, as well as soprano Beni Ittulak, who is tireless in her efforts to honour the legacy of her ancestors. I have been privileged also to work with soprano Deantha Edmunds in her crusade to bring the legacy of this music to larger audiences. Sadly, in 2022 there are no longer any tradition-bearing organists left on the Labrador coast. I was extremely fortunate to have been able to learn at the side of several truly great ones, including David Harris, Sr, John Jararuse, Simeon Nochasak, and Paul Harris, as well as string player James R. (“Uncle Jim) Andersen. The import of this music tradition in the lives of Labrador Inuit was opened to me through the wisdom shared by a large number of Elders and chapel servants whose lived experience as Moravian Inuit and deep knowledge of its practice in their language lifted my understanding beyond the music to its spiritual and cultural meaning. Among these are Johannes Lampe, Gordon Obed, Sr, Rose Pamak, Rita Andersen, Sarah Townley, Sophie Tuglavina, and Angus Andersen. In each of the Moravian communities of Labrador I was made welcome by numerous congregants and community members. The list is too long to enumerate, but I must single out a few. In Makkovik, I found ready assistance and encouragement from Joan and John Andersen and Natalie Jacques. In Hopedale, I was generously supported by Nicole Shuglo, Sarah Jenkins, Marjorie Flowers, and Martha Winters-Abel. And in Nain, Fran Williams, Dave Lough, Darlene Howell, and Joan Dicker were among the many who extended great kindness to me. I also owe a great debt of gratitude to the entire staff at the Oĸâlaĸatiget Society for the generous access provided to their extensive audio archives. When I began this work I had little knowledge of the Moravian Church and even less of its extraordinary history on the north coast of Labrador. My guide in learning this side of the story has been my exceptionally generous colleague at Memorial University, Hans J. Rollmann. Hans’s dominating presence in

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 21

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

ac k now l e d gm e n t s

x x ii

the bibliography appended to this work barely hints at the truly encyclopedic knowledge he has of the Moravian presence in Labrador. His generosity in showing me how to access records, but especially in responding to my every question, has been incredible. I am also deeply indebted to colleagues who encouraged this adventure and embarked with me on it. To Tim Borlase, who literally introduced me to this music tradition and to many of its stewards, and especially to Mark David Turner, who engaged completely with our several projects and, once Tittulautet Nunatsiavuttini was launched, assumed responsibility for responding to the communities to revitalize the brass band movement, I owe a debt of gratitude for their encouragement, wisdom, and commitment. I am equally grateful to Nigel Markham, whose earned trust among Labrador Inuit and brilliant work on the film Till We Meet Again was the catalyst for all the subsequent collaborative community ventures. Other indispensable co-adventurers include choral conductor Kellie Walsh, organist and music educator David Buley, and brass gurus Terry Howlett and Stephen Ivany. I have been greatly assisted by several institutions that preserve and promote Moravian music and culture. Among these are the Moravian Music Foundation and its extremely helpful staff: Nola Reed Knouse, Gwyn Michel, and David Blum. I have also been kindly assisted by staff at the Moravian Archives in Bethlehem, pa, including Thomas McCullough and Paul Peucker, as well as at the UnitätsArchiv, Herrnhut, especially Olaf Nippe. I am also grateful to Hannie Hettasch Fitzgerald, daughter of the last Moravian missionary at Hebron, for opening her personal archives to me. At Memorial University’s Queen Elizabeth II Library I was given generous access to the holdings of the library’s Archives and Special Collections and the expertise and resources of its Centre for Newfoundland Studies (cns). Other academic colleagues from Memorial University who have given me extremely useful advice include Beverley Diamond, Lisa Rankin, Jane Leibel, and Nancy Dahn. In the course of many years of digitizing, cataloguing, and deciphering music manuscripts I have benefited enormously from many student research assistants. Most immediately I wish to thank Eric Taylor Gomes Escudero, who has provided invaluable assistance in preparing the manuscript for this book. Going back further, I was very expertly assisted with the digitizing and cataloguing of manuscripts by several generations of Inuit student assistants. These include Lena Onalik (now archaeologist for the Nunatsiavut government), Carolyn Nochasak in Nain, and Kendra Jacques in Makkovik. In addition there was, over the years, a veritable army of student assistants who undertook the raw work of transcribing manuscript parts using music notation software until

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 22

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

x x iii

ac k now l e d gm e n t s

the entire Labrador anthem repertoire had been produced in modern editions. Among these students were Sean Rice, Michael Bramble, Anthony Payne, and Vanessa Carroll. As multifaceted as this research and engagement program has been, it would have been impossible without financial support from a wide range of institutions. I was fortunate to receive several research grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, as well as additional funding through “Tradition & Transition,” the sshrc-funded partnership between the Nunatsiavut government and Memorial University. My home institution, Memorial University of Newfoundland, has provided support in a variety of ways over two decades, with enabling funding for various aspects of the project coming from the Bruneau Centre for Excellence in Choral Music; the Research Centre for Music, Media, and Place; and Memorial’s Office of Public Engagement. Certain elements of the project have also benefited from funding awards made directly to Labrador Inuit communities by the International Grenfell Association and the Newfoundland and Labrador Arts Council. McGill-Queen’s University Press has been an active supporter of this project from Mark Abley’s first encouragement to develop the manuscript a decade ago to the timely and expert guidance Filomena Falocco’s marketing team. In between the book has benefited immeasurably from Jonathan Crago’s gentle editorial hand and wise and well-considered advice, as well as Kathleen Fraser’s thoroughly professional stewardship as it has moved through all stages of production. I am equally indebted to Matthew Kudelka, whose insightful copy editing brought greater clarity to my text, and to Tim Pearson for creating a thoughtful and useful index. To everyone at mqup who coaxed and nurtured this project into being, my sincere gratitude. Finally, but not least, I wish to thank Mary O’Keeffe for two decades of support and encouragement as she shared me with this project. Parts of chapters 5 and 7 were previously published in Newfoundland and Labrador Studies and Newfoundland Quarterly1 and are reproduced here with permission.

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 23

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 24

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

Audio Examples and Musical Scores Much of the discussion, particularly in chapters 4 and 7, centres on Moravian Inuit music as performed. Thus access to recordings of these performances has been provided on a website to clarify and enhance these discussions, as well as provide an opportunity to hear several generations of Labrador Inuit musicians. For those who also read music, full scores of many of the works discussed are provided on the accompanying website: https://collections.mun.ca/digital/collection/calledupstair.

Anthems Ahâ ĸ Ahâ ĸ Gûdibta iglunga (1910) by Natanael Illiniartitsijok

Audio performed by the Nain Moravian Choir (2004). Courtesy of the Oĸâlaĸatiget Society Broadcaster and the Nain Moravian Church Choir. Score based on parts in the manuscript collection of the Nain Moravian Church. Hosiana Jêsus nakudlarpok/Hosianna, gelobet sey der da kommt (1765) by Christian Gregor

Audio sung by Nain Moravian Choir from 1966 recording by Joe Goudie. Courtesy of the Oĸâlaĸatiget Society Broadcaster and the Nain Moravian Church Choir. Score based on parts in the manuscript collections of the Nain, Hopedale and Makkovik Moravian churches. Jêsub nia ĸone nêrpa/Jesus neigte sein Haupt (ca. 1766) by Christian Gregor

Audio performed by Deantha Edmunds, soprano soloist; the Newfoundland Symphony Orchestra, Kellie Walsh, conductor; Lady Cove Women’s Choir & Newman Sound Men’s Choir on 3 March 2018. By permission of performers. Score based on parts in the manuscript collections of the Hopedale and Makkovik Moravian churches.

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 25

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

au dio e x a m pl e s a n d m usic a l s c or e s

x x v i

Kuvianak Bethaniab iglunga/O Bethania, du Friedenshütte (ca. 1750) by Johann Daniel Grimm

Audio performed by Regina Sillitt, soprano soloist with the Nain Moravian Choir, 1971. Courtesy of the Oĸâlaĸatiget Society Broadcaster and the Nain Moravian Church Choir. Score based on parts in the manuscript collection of the Nain Moravian Church. Kuvianak nerringijavut/O angenehme Augenblicke (ca. 1800) by Joseph Jackson

Score based on parts in the manuscript collections of the Nain, Hopedale and Makkovik Moravian Churches. Piulijivut ivsornaitotojotit/Heilge Ruhe der entschlafnen Glieder (1783) by Christian Ignatius La Trobe

Audio performed by Karrie Obed, tenor with the Nain Choir and the Innismara Vocal Ensemble (2011). Recorded for the film Till We Meet Again; Moravian Music in Labrador. Courtesy of the artists and Nigel Markham, producer. Score based on parts in the manuscript collections of the Nain and Makkovik Moravian Churches. Upkuaksuit angmasigik/Macht hoch die Thür, die Thor macht weit by John Gambold, Jr

Audio performed by the Makkovik Inuit Choir (1959). Courtesy of the Oĸâlaĸatiget Society Broadcaster and the mcnl. Score based on parts in the manuscript collection of the Nain and Hopedale Moravian Churches.

Brass Bands Melodie 83f, “Jesus, meine Zuversicht”

Audio performed by the Makkovik Brass Band, ca. 1960. Courtesy of the Hettasch Family Collection, asc. “What a Friend We Have in Jesus” by Joseph Medlicott Scriven

Audio performed by the Makkovik Brass Band, ca. 1960. Courtesy of the Hettasch Family Collection, asc.

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 26

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

x x v ii

au dio e x a m pl e s a n d m usic a l s c or e s

“Vesper Hymn” by Dmitry Bortniansky

Audio performed by the Makkovik Brass Band, ca. 1960. Courtesy of the Hettasch Family Collection, asc. Christmas hymns:

a) Melodie 14b, “Lobt Gott, ihr Christen allzugleich;” b) Melodie 61, “Lobe den Herren, den mächtigen König der Ehren;” c) “Napartole/O Tannenbaum;” d) “Sorutsit/Ihr kinderlein kommet;” and e) Melodie 160, “Was Gott thut, das ist wohlgethan.” Courtesy of Dr Maija Lutz. Audio performed by the Nain Brass Band on Christmas morning, 1978. Melodie 68, “Seelen Bräutigam, Jesu, Gottes Lamm”

Audio performed by Nain Brass Band, 1989. Courtesy of the Hettasch Family Collection, asc. Melodie 71b, “Lord, who Didst Sanctify”

Audio performed by Nain Brass Band, 1989. Courtesy of the Hettasch Family Collection, asc. “Aggakka tigulugit tessiunga/So nimm denn meine Hände”

Audio performed by Nain Brass Band, 1989. Courtesy of the Hettasch Family Collection, asc.

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 27

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

au dio e x a m pl e s a n d m usic a l s c or e s

x x v iii

Hymns “Ernîk erligidlarpagit,” composer unknown

Audio a) sung by the Nain Choir, 2000; b) performed by the Nain Brass Band, n.d. Courtesy of the Oĸâlaĸatiget Society Broadcaster and the Nain Moravian Church Choir. Score manuscript in the hand of Levi Nochasak. “Iniksalik/Yet there is room,” (1875), by Ernst Wilhelm Woltersdorf and Dora Rappard

Audio sung by the Nain Choir from 1966 recording by Joe Goudie. Courtesy of the Oĸâlaĸatiget Society Broadcaster and the Nain Moravian Church Choir. Score (1963) manuscript facsimile in the hand of Rev. Siegfried Hettasch. Courtesy of the Agvituk Historical Society, Hopedale. “Takkotigilarminiptingnut/God be with you till we meet again,” (1890) by Jeremiah Rankin and William Tomer

Audio sung by the Hopedale Moravian Choir and the Innismara Vocal Ensemble (2011). Recorded for the film Till We Meet Again; Moravian Music in Labrador. Courtesy of the artists and Nigel Markham, producer. Score based on parts in the manuscript collection of the Nain Moravian Church.

Other “ĸôb sennianut ingito ĸ /An einem fluss, der rauschend schoss” (ca. 1816) by Wilhelm Erk

Audio sung by Christina Kojak (1978). Courtesy of Dr Maija Lutz. Score from Imgerutsit nôtiggit 100, #89

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 28

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

c a l l e d u p s ta i r s

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 1

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 2

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

1

Backstories

I. Introduction The only thing the backstories of Inuit of Labrador and the Moravian Church really share is a point in time. Thule-culture Inuit, the direct ancestors of the present-day Nunatsiavummiut,1 arrived on the Labrador Peninsula sometime during the fifteenth century as part of a centuries-long eastward migration across what is now the Canadian Arctic. Unitas Fratrum – the Unity of the Brethren, more commonly known as the Moravian Church – split off from Catholicism around the same time, in the mid-fifteenth century. Adhering to the teachings of the martyred priest Jan Hus, Unitas Fratrum became what is widely regarded as the first Protestant church. Both groups originated in a process of leaving. Three hundred years later, they found each other, forging an unlikely, imbalanced, yet enduring association. It was in 1752 that Labrador Inuit and the Moravians encountered each other for the first time.2 That initial encounter ended catastrophically for the Moravians, but the missionaries persisted, and by the end of the eighteenth century they had established a presence among Labrador Inuit. Inuit and the Moravians developed a symbiotic relationship that would endure for more than 200 years and that continues to resonate powerfully in the Nunatsiavummiut identity today. Make no mistake: it was a colonizer/colonized relationship. In the key respects – economic, civic, moral, and cultural – the missionaries held the balance of power. Yet Inuit circumvented the annihilation of agency through a variety of forms of defiance and resistance, feigned assimilation, and adaptation. The two groups did share one common trait. Both were, in different ways, subsistence cultures: Inuit literally so, for they were shaped by the need to extract a life, livelihood, and, inevitably, an identity from the environment that surrounded them. The Moravians, on the other hand, were spiritually a

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 3

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

figure 1.1 Bishop L.T. Reichel, map of Moravian Labrador, 1871.

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 4

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

5

bac k st or i e s

subsistence culture. Every aspect of life was determined by their desire and need to know their Christian God. These divergent forms of subsistence culture defined the expectations that both groups brought to the relationship. Inuit looked to the Europeans with the expectation that their seemingly abundant access to non-subsistence food sources and manufactured goods could supplement Inuit reliance on hunting and gathering. Additionally, the accumulation of European goods confirmed social and political hierarchies among Inuit. The missionaries came with the express purpose of Christianizing Inuit, imposing their culture of spiritual subsistence. Both sets of expectations were met, though with varying degrees of satisfaction and success. At the same time, the missionaries came to acknowledge their dependence on Inuit to mediate what was, to the Europeans, a very hostile environment. And Inuit adopted and assimilated aspects of European lifeways that they regarded as improvements to their way of life. To better understand this relationship and, in particular, the role that music played in it, it will be useful to explore the backstories that brought Inuit and the Moravians to the point of their encounter. Like every aspect of the relationship, there will be an imbalance in the evidence that can be brought to bear in understanding this background. The Moravians were diligent – perhaps even obsessive – chroniclers. Their story, even during more than a century of an underground existence, has been narrated in detail. Prior to the arrival of the Moravians, Labrador Inuit were not a literate society. Their written record begins with the Moravians and was recorded – and inflected – through Moravian eyes and ears. Pre-contact records of Labrador Inuit are found in scattered, emerging, and incomplete testaments from material culture, or they come to us through Oral Tradition, which, by Western scientific standards, has tenuous links to the present and may have been unreliably recorded by non-Inuit. The imbalance between these sets of records is especially relevant with respect to music. Music is the most ephemeral form of expressive culture. Before the age of recorded sound, we have scant information about what any music actually sounded like. In musically literate cultures, notation, together with organology, treatises on performance practice, and critical writing, offers the possibility of reconstructing a facsimile of what music from a certain time and place might have sounded like. But for pre-literate societies, the evidences are few, restricted to archaeological finds of musical instruments and traditional practices that appear to have been carried forward with minimal interruption. So as evidence is brought forward from these records it will need always to be assessed in light of who created the record and to what purpose. As with all music, what is not on the page is as important as what is.

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 5

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

c a l l e d u psta i r s

6

When Labrador Inuit and Moravian missionaries came together across a series of first encounters that stretched over almost two decades, their differences were far more pronounced than their similarities. Language, lifeways, belief systems and values, social structures – all reflected widely disparate histories and cultures. But a common bond – one that would establish a basis for communication and trust between them – was the role that music played in both cultures as a vehicle for communication, social interaction, and personal and cultural expression. In the pages that follow, I will sketch the background and contexts for Labrador Inuit and the Unitas Fratrum leading up to their first encounters, with particular focus on the role music played in both societies and as a foundation for intersection.

II. Labrador Inuit The history of human habitation on the Labrador Peninsula reaches back at least seven millennia. The northern branch of the Maritime Archaic people, a First Nations population from the south, was established on the Labrador Straits by around 7,000 years ago, as evidenced by the rich burial site at L’Anse Amour. From there they migrated northward as far as Saglek and Ramah Bays, developing sophisticated technologies utilizing the unique deposit of chert at Ramah Bay. Archaeological evidence confirms that Maritime Archaic people were distributed along the entire coast of Labrador until around 1500 bc, when they began encountering competition for resources from the Pre-Inuit culture, newly arrived from the north.3 The Pre-Inuit culture, remotely related to but distinct from the ancestors of present-day Labrador Inuit, appears to have originated in Alaska a little over 4,000 years ago. Their migration across the Canadian Arctic seems to have followed a trajectory similar to that of the subsequent Thule culture; they arrived in northern Labrador at Saglek Bay around 1800 bc. The early Pre-Inuit culture experienced rapid population growth in Labrador (and on the island of Newfoundland) around 1000 bc, possibly due to the disappearance of the Maritime Archaic people. However, the population declined again around 200 bc and was gradually replaced by a related but more sophisticated culture commonly referred to as Dorset. These people, who may have originated around the mouth of Hudson Bay, developed technologies that continue to define important aspects of Inuit material culture, including sleds and soapstone lamps, as well as tools that favoured harvesting from the sea. The Dorset culture was widely distributed across both Labrador and the island of Newfoundland

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 6

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

7

bac k st or i e s

until around 1,000 years ago, disappearing first from Newfoundland and then gradually from the coast of Labrador. Their archaeological record on the Labrador Peninsula ends around 1500 ad.4 The history of the other long-standing Indigenous population of Labrador, the Innu, is murkier. Unlike the Maritime Archaic, Pre-Inuit, and Dorset cultures, which were built on harvesting from the sea and thus tended to hug the coasts, the Innu are a nomadic people who live most of the year deep in the interior of the Quebec/Labrador Peninsula. In warmer months they would visit coastal areas to fish and hunt marine mammals. Given the vastness of this territory and the nomadic life of the Innu, their archaeological record is thin. They may be descendants of people who arrived on the Quebec/Labrador Peninsula from the north about 9,000 years ago, and they likely traversed huge territories with connections to numerous other cultures. Archaeologists have documented habitation sites dating from around 2,000 years ago that may reflect the culture of direct ancestors of the contemporary Innu.5 With the arrival of the Thule-culture Inuit, the ancestors of Innu abandoned their activities on the coast except for occasional trading excursions.6 Although forced to settle in two permanent communities in the twentieth century, many Innu continue to utilize the vast landmass of the peninsula. Thule-culture Inuit, the direct ancestors of the modern-day Nunatsiavummiut, began their migration around a thousand years ago from the western Arctic toward the Atlantic, accelerating their movement during the thirteenth century. As the migration continued eastward, Thule settlement of Greenland began around 1500. Other migrants hung a right at Baffin Island, moving southeast to Cape Chidley and eventually spreading southward along the Labrador coast. The arrival of the Thule culture along the Labrador coast probably occurred during the fifteenth century with a pre-contact presence in Saglek Fjord. Inuit exploration and settlement farther to the south (e.g., at Avertok at modern-day Hopedale) dates from the post-contact period. This migration to points farther south likely occurred very rapidly to afford Inuit easier access to European goods.7 As their migration extended farther south, Labrador Inuit became one of the few Inuit groups in Canada to venture below the tree line. Consequently they came into early contact with other Indigenous groups, as well as the first European arrivals on the Labrador Peninsula, including Basque whalers and British traders like George Cartwright.8 By the early eighteenth century, Labrador was nominally under the control of the British and Newfoundland governments and had become the stage for sometimes violent conflict between Inuit and seasonal fishermen. For more than 600 years the descendants of Thule-culture Inuit have adapted their culture to live in harmony with the environment of Labrador’s Atlantic coast –

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 7

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

c a l l e d u psta i r s

8

Figure 1.2 An Inuit drum (qilaut).

an environment harsh and generous in equal measure. Thule culture developed an extensive hunting-tool industry utilizing bone, antler, and ivory. With highly sophisticated technologies that allowed them to exploit the riches of the sea, Inuit lived semi-nomadically, rarely venturing far from access to the marine mammals – especially ringed seals – that provided food, clothing, and shelter. Thule winter houses were generally round, easily identified by stone circles and whalebone supports, with raised stone sleeping platforms and at least one lamp stand. Seasonally they moved from winters at the edge of the ice to summer fishing camps deeper in the fjords. Over the ice they could travel great distances with dog teams and komatiks (sledges); on the water, umiaks (women’s boats) transported families and goods, while the agile qajaq (kayak) served as a superior hunting vessel.9 The documentation of pre-contact Thule expressive culture is scattered and thin, drawn chiefly from archaeological finds such as carvings and other non-utilitarian artifacts as well as captured or described oral traditions of storytelling. This evidence is often speculative at best and only rarely specific to Inuit of Labrador.10 Archaeologist Peter Whitridge has provided a concise overview of the archaeological proofs of music practice among Inuit of Labrador at the point of contact.11 Among the sound-producing instruments commonly found across all recent Inuit cultures are bullroarers, buzzers, and drums. The last-named is the most ubiquitous and considered by some to be the only Indigenous Inuit instrument. The Inuit drum (qilaut) typically consisted of a slender circular or ovoid

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 8

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

9

bac k st or i e s

grooved wood, bone, or baleen frame, ranging widely from 25 to 70 centimetres in diameter, over which a thin sheet of gut or hide was stretched. The drum was held by a short bone or wood handle attached to the frame, and the underside of the frame - not the taut skin - was beaten with a bone or wood baton to produce the tone. Archaeological evidence of drum rims can be dated to as far back as 4,500 years ago. The drum was still central to Inuit religious practice and artistic performance in the early contact era.12 Also observed on the Quebec/Labrador Peninsula is the tautirut, a primitive string instrument with one to three strings that existed in various forms across the Arctic. In addition to evidence provided by a dozen or so examples found in archaeological sites,13 these instruments were observed by early Europeans on the Labrador coast. Tautirut were usually played on the lap with a sinew-strung bow. They may have been modelled on or inspired by instruments introduced by whalers, like the Norse fidla or the kit violin (or pochette). However, the near universality of some form of stringed instrument across the Arctic suggests the likelihood of a pre-contact existence.14 Although there is no physical evidence, Oral Tradition and chronicles of early-contact observers provide evidence of rich and varied forms of singing and vocal expression. Whitridge catalogues these to include “various genres of Inuit singing, often self-accompanied by drumming and dancing, and including formal song ‘duels’, angakkuk (shaman) ceremonial [songs], personal performances at festivals and other social gatherings, and a distinctive genre of vocal play and performance called katatjak or throat singing.”15 Both katatjak and drumming have experienced revivals in recent decades in the context of a burgeoning nationalism and pride in pre-contact Inuit expressive culture. Performances of music were often associated with activities in Inuit qaggiq16 (ceremonial house). A qaggiq was a large, non-domestic structure in Inuit winter settlements. Its functional descriptions include: “ceremonial house, club house, communal house, dancing house, feasting house, festival house, meeting house, men’s house, pleasure house, singing house, social house, and quasiceremonial gathering place.”17 Typically qariyit were constructed in winter settlements where larger numbers of families gathered to celebrate and share a particularly bountiful hunt, especially if a whale had been harvested. Early contact descriptions of qaggiq activities offer insight into some of the forms and functions of music in Labrador Inuit society predating the arrival and adoption of European music. One such description dates from 1777, when Moravian missionary Christian Lister visited a large qaggiq (4.9 metres high by 21 metres round), about 55 kilometres southeast of Nain. Inside the ceremonial house, Lister observed the performance of a game in which the boastful hunter sang of his prowess:

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 9

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

c a l l e d u psta i r s

10

Then a man begins and strikes the string with his stick, and then all the men try with their sticks to hit one of those holes of the bone that hangs in the middle, and in one or two minutes someone will have hit one of the holes. When that happens they all shout as loud as they can, and then all the men sit down on the bench, which is round the house and made of snow, except the man that has hit the hole in the bone. He steps forward and if he is a married man his wife or if he has more than one wife these, together with all the women present, follow him in procession several times round the house. He sings with all his might whatever he can about seals, reindeer, foxes, etc. and then all the men and boys stand up and kiss the man and the women as they please. In this manner he goes slowly 4 or 5 times round the house. Then he goes again to the string and sings again as before, till he has finished his song all the women standing round him.18 The association of singing with communal gathering and social interaction is the common theme running through early contact accounts. Whether in ceremony, celebration, sport, or other forms of communal recreation, singing and music occupy an essential position. Perhaps most emblematic of this association for the long-standing relationship between Labrador Inuit and the Moravians is the account of a meeting between Jens Haven and the angakkuk Seguliak. Haven made the first of several preliminary voyages across the Atlantic with the intention of establishing a mission among Labrador Inuit. A Dane who had already spent four years among the Greenlanders in establishing the Moravian mission at Lichtenfels, Haven spoke the Greenlandic dialect of Inuktitut. Haven’s first actual encounter with any Labrador Inuit occurred on Quirpon Island in the Strait of Belle Isle between Newfoundland and the south coast of Labrador. His diary for 6 September 1764 recorded the meeting: Someone came and asked whether I could dance and had a drum. I said “no.” He asked if I could sing, I said “yes.” He said he would sing something for me, I said “do so.” He starts to jump and dance and sang with it. I could not understand anything except “our friend has come, which makes us happy.” This he repeated often, and when he was finished, he said that I should answer him. I sang with a fond heart: “Naleganga,” or, “Lord Sabaoth.”19 They listened and when I was finished they told me: “we are without words.”20

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 10

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

Figure 1.3 An early nineteenth-century depiction of Jens Haven conversing with Inuit at Nain, Labrador, by British artist Maria Spilsbury, ca. 1819.

The symbolic import of singing, drumming, and dancing as a central element to confirm a relationship is powerful testament to music’s importance in the ceremonial and communal ethos of Inuit culture. Haven’s first-hand account recognizes the significance of formalizing a social contract through a musical exchange. Seguliak’s opening questions carry the implication that the worth of a man will, in part, be judged on his ability to dance, drum, and sing. Jens Haven makes no judgment about Seguliak’s performance except to note the relative unintelligibility of the words, likely a result of differences between the Labrador and Greenlandic dialects of Inuktitut. What he does clearly understand is that the angakkuk’s song was an expression of joy at his arrival. Haven’s language suggests that the performance was foreign to his sensibilities, but he fully understood its intent. Haven records that Inuit, for their part, were speechless in the face of this first confrontation with Moravian hymnody, a reaction that could be interpreted any number of ways.

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 11

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

c a l l e d u psta i r s

12

This same encounter is retold in a history of the Moravian missions in Labrador on the occasion of the centenary of the settlement at Nain. Here the anonymous writer editorialized the performances of both Seguliak and Haven, foregrounding a bias against Inuit singing that had become pervasive throughout Moravian depictions of Inuit before the saving graces of Christianity and Western culture. The retrospective writer’s account of the very same meeting is characterized by highly prejudicial language. “Among them was Seguliak, the angekok or sorcerer, who seemed to have the authority of a chief. He was particularly friendly. Once when they began a dance in honour of their guest, accompanying it, in true heathen fashion, with terrible noises, Br. Haven sang a hymn in Greenlandic, whereupon they instantly ceased, and listened attentively to the end.”21 The characterization of Inuit music as “terrible noises” had become a cliché across the Moravian chronicles and among those observers who sympathized with the missionaries’ mandate to civilize Inuit. Among its earliest appearances was in the account of a shamanistic divination ceremony observed by the missionary Johann Schneider at a winter encampment at Niatak on 31 January 1773.22 Overnighting with a group of Inuit hunters who had been unable to hunt seals because of heavy squalls, Schneider witnessed a summoning of Torngak by a female shaman, Sattugana: But in the evening when we had lain down, we also had to find out how the Prince of Darkness still reigns among these people and performs his work among them … All the lamps were then extinguished and the house made pitch dark. Then she began to invoke her torngak with deep sighs and groans and noises until she began to eject words, sometimes with a loud sharp voice,23 then again with a terribly gruff deep voice so that the house could have shaken. And when she was a little quiet, the people here and there called out to her or asked what the torngak was saying. And thus she began again in the above manner until the torngak had hit upon her meaning. Then all the people began to sing on one pitch according to the heathen manner of the Greenlanders. When the song had ended, the torngak continued as before in the meantime was accompanied by the people with a song. Finally there occurred a terrible bang as if the house were to collapse, since she presumably had beaten against a stretched skin with a stick.24 After this she came down from the berth into the house with her torngak, waved around as with a whip, hit here and there, went to the entrance of the house, stamped her feet, made a horrible noise, brought forth peculiar voices.25

MQUP.Gordon (Called Upstairs).TEXT.PRINT.REVISED.indd 12

2023-02-15 2:18 PM

13

bac k st or i e s