After the Battle The Battle for Magdeberg

THE BATTLE FOR MAGDEBURG — Karel Margry describes how Magdeburg, located on the Elbe river in central Germany, was one o

398 53 24MB

English Pages 56 Year 2018

THE BATTLE FOR MAGDEBURG — 2

JU 52 Crashes at Heraklion — 36

Führerhauptquartier ‘Wolfsschlucht 3’ — 42

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Winston G. Ramsey

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

80>

9

770306 154103

THE BATTLE FOR MAGDEBURG No. 180 £5

NUMBER 180 © Copyright After the Battle 2018 Editor: Karel Margry Editor-in-Chief: Winston G. Ramsey Published by Battle of Britain International Ltd., The Mews, Hobbs Cross House, Hobbs Cross, Old Harlow, Essex CM17 0NN, England Telephone: 01279 41 8833 Fax: 01279 41 9386 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.afterthebattle.com Printed in Great Britain by Warners Group Publications PLC, Bourne, Lincolnshire PE10 9PH. After the Battle is published on the 15th of February, May, August and November. LONDON STOCKIST for the After the Battle range: Foyles Limited, 107 Charing Cross Road, London WC2H 0DT. Telephone: 020 7437 5660. Fax: 020 7434 1574. E-mail: [email protected]. Website: www.foyles.co.uk United Kingdom Newsagent Distribution: Warners Group Publications PLC, Bourne, Lincolnshire PE10 9PH Australian Subscriptions and Back Issues: Renniks Publications Pty Limited Unit 3, 37-39 Green Street, Banksmeadow NSW 2019 Telephone: 61 2 9695 7055. Fax: 61 2 9695 7355 E-mail: [email protected]. Website: www.renniks.com Canadian Distribution and Subscriptions: Army Outfitters/Military Antiques Toronto 1884 Danforth Ave, Toronto, Ontario, M4C 1J4 Telephone: 647-436-0876 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.servicepub.com New Zealand Distribution: Battle Books NZ Limited, P.O. Box 5549 Lambton, Wellington 6145, New Zealand Telephone: 021 434 303. Fax: 04 298 9958 E-mail: [email protected] - Web: battlebooks.co.nz United States Distribution and Subscriptions: RZM Imports Inc, 184 North Ave., Stamford, CT 06901 Telephone: 1-203-324-5100. Fax: 1-203-324-5106 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.rzm.com Italian Distribution: Milistoria s.r.l. Via Sofia, 12-Interporto, 1-43010 Fontevivo (PR), Italy Telephone: ++390521 651910. Fax: ++390521 619204 E-mail: [email protected] — Web: http://milistoria.it/ Dutch Language Edition: SI Publicaties/Quo Vadis, Postbus 188, 6860 AD Oosterbeek Telephone: 026-4462834. E-mail: [email protected]

CONTENTS THE BATTLE FOR MAGDEBURG CRETE Ju 52 Crashes at Heraklion FRANCE Führerhauptquartier ‘Wolfsschlucht 3’

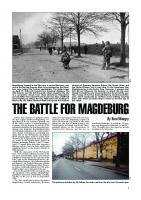

Although the Nazis originally discarded Magdeburg as a ‘Red stronghold’, nonetheless local votes for the NSDAP in Reichstag elections rose from 33 per cent in November 1932 to 41 per cent the following March. Here SA brownshirts proudly march through the city in 1936. The city of Magdeburg is situated on the Elbe river in central Germany. Founded by Charlemagne in 805 AD, it was one of the most important cities in medieval Europe, and a prosperous member of the Hanseatic League. A stronghold of Protestantism, in 1631 it was devastated by Imperial and Catholic League troops who killed 20,000 inhabitants and burned down the city in the notorious Sack of Magdeburg, the worst massacre of the Thirty Years War. Throughout the 17th and 18th century the Prussians rebuilt and enlarged Magdeburg’s fortifications, making it one of the Kingdom’s strongest fortresses, its major component being the great citadel built on Werder, the island that lies in the Elbe across from the Old City. Nonetheless, the city surrendered easily to French troops in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars. In 1866, Prussia halted the further fortification of Magdeburg, allowing the city to expand beyond its ram-

parts. Many of the city gates, bastions and outlying forts were pulled down, their sites released for housing development. The citadel was demolished in 1922-27. With the coming to power of the NationalSocialists in January 1933, Magdeburg, despite its reputation as a ‘Marxist stronghold’, soon embraced the new ideology. In March 1933, two months into the new regime, the Nazis forcibly deposed Oberbürgermeister Ernst Reuter and replaced him with Dr Fritz Markmann, a convinced Nazi. Although Magdeburg was the capital of the Prussian province of Saxony, and by far the most-important city in the region, the NSDAP did not make it their Gau (Nazi Party district) capital, opting instead for its rival city, Dessau. Named Gau Magdeburg-Anhalt, from 1937 it was the fief of Gauleiter Rudolf Jordan, party affairs in Magdeburg itself being overseen by NSDAP-Kreisleiter Rudolf Krause, replaced in December 1943 by Hans Tichy.

2 36 42

Front Cover: A Sherman tank of the 66th Armored Regiment, US 2nd Armored Division, rolls past the bomb-damaged Palace of Justice on Halberstädter Chaussee in Magdeburg on the second day of the battle for the city. The picture was taken by Sergeant Edward M. Du Tiel of the 168th Signal Photo Company on April 18, 1945. Inset: The restored Palace of Justice today. (USNA/Karel Margry) Back Cover: German dead from the 1941 invasion of Crete, including the aircrew and paratroopers lost on May 20, were buried in Maleme War Cemetery. For many years this Bofors anti-aircraft gun – which was the type of weapon used to bring down the Ju 52s – was displayed at the small war museum just outside the cemetery. The museum, exhibiting the private collection of Manolis Paparaftakis, had to close in 2013 and the gun is now in the yard of his house in Maleme village.

Photo Credit Abbreviations: AWM — Australian War Memorial; IGN — Institut Géographique National; USNA — US National Archives.

2

USNA

Acknowledgements: For their valuable assistance with the Magdeburg story, the Editor thanks Thierry van den Berg of Bombs Away Ltd and Martijn Bakker. For help with the ‘Wolfsschlucht 3’ story, the Editor and Jean Paul Pallud extend their gratitude to Marc Doucet, Jean-Paul Brillard and to Jean Pierre Gort of the Hist’Orius association.

A major event in the local Nazi calendar was the festive opening of the Brabag synthetic oil refineries in Magdenburg-Rothensee in July 1936.

USNA

Magdeburg, located on the Elbe river in central Germany, was one of the last big German cities to be captured by the American army before the German capitulation. The battle began on April 17, 1945 and involved two American divisions, the 30th Infantry and the 2nd Armored, which assaulted the city in a concentric attack from three directions. Opposition proved stiffer than expected and it took two days of difficult street-fighting to reduce the city. Well before the landings in Normandy, the Allied Chiefs-of-Staff had agreed the ultimate

division of Germany between Britain, the Soviet Union and the United States, and it was clear to the Americans that Magdeburg lay in the Soviet Zone. However, it appears that this did not influence the decision to attack the city even though it would have to be surrendered at the end of the war. Here, troops of the 41st Armored Infantry, 2nd Armored Division, watch cautiously as civilians come walking towards them with white surrender flags in hand on the first day of the attack.

THE BATTLE FOR MAGDEBURG April 1942 and January 1944, 876 Jews were deported from the Magdeburg region (of whom 360 from the city itself) in nine train transports, the first of them going to the Warsaw ghetto in Poland, four to the Theresienstadt ghetto in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, and the rest to

By Karel Margry Auschwitz-Birkenau. In addition, 470 gypsies were deported to Birkenau on March 1, 1943. Virtually all of the deported people perished in the holocaust.

ATB

Rather than making it a political centre, the new regime advanced Magdeburg as a spearhead of its war economy. Already one of the oldest centres of manufacturing in Germany, the city became a true hub of the armaments industry, the most important production sites being the Braunkohle-Benzin AG (Brabag) refineries in the north-western town district of Rothensee, producing synthetic fuel for the Wehrmacht; the Junkers MZM aircraft engine works in nearby Neue Neustadt; the Krupp-Gruson heavy machinery works in the south-eastern district of Buckau, producing PzKpfw I and IV tanks, StuG IV assault guns and other armoured fighting vehicles, and the Polte small-arms munitions factory in the western district of Wilhelmstadt. With the expansion of the Wehrmacht from 1935 onwards, military presence in the city grew considerably, large new barrack complexes being built on the east side of the Elbe, such as the Hindenburg-Kaserne, the Adolf-Hitler-Kaserne, the General-von-Hippel-Kaserne, the Luitpold-Kaserne military hospital and the Flak-Kaserne Neue Prester, as well as a Luftwaffe airfield. By 1939, some 20,000 soldiers were stationed in the city. Due to the growth of the war industry and the expansion of the garrison, Magdeburg’s population increased considerably, reaching 336,000 on the eve of war in September 1939. The Nazi racial persecutions decimated Magdeburg’s Jewish community. Between

The picture was taken on Alt Salbke, the main road into the city from the south-east. 3

USNA

Magdeburg suffered heavily under the Allied bomber offensive, being the target of over 40 RAF and USAAF raids. The most-destructive of these was the RAF raid on the evening of AIR RAIDS ON MAGDEBURG Magdeburg was one of the German cities that suffered most heavily under the Allied air offensive. In anticipation of a bomber war, and following Hitler’s decree on air raid protection of October 1940, the city authorities had built 13 large air raid bunkers (three of them hospital bunkers) but these could only accommodate less than two per cent of the population — making Magdeburg one of the worst supplied with bomb-proof shelters of all the big German cities. In addition to the bunkers for the general public there were special air raid shelters for industrial workers in the grounds of the main factories, most of them built later in the war. The first British attack occurred on the night of August 22/23, 1940, when ten Wellingtons from RAF Bomber Command scattered bombs all over the city, killing three people and wounding seven. (These bombers must have been widely off course for their official target that night was the Ruhr industrial area over 300 kilometres away!) Bomber Command’s first ‘official’ attack on Magdeburg was two weeks later, on the night of September 3/4, when a small number of Blenheims dropped a few bombs on the city. Three equally small raids followed in October, November and (another stray one) December. Although Magdeburg was high on the list agreed by the British Air Ministry in January 1941 of the 17 main oil targets in Germany to be destroyed by bombing, there were just three attacks on the city that year — in April (a stray one), July and August — and then not a single one for the next two and a half years. The first main raid to Magdeburg was on the night of January 21/22, 1944, when 648 bombers — 421 Lancasters, 224 Halifaxes and three Mosquitoes — were despatched to 4

January 16, 1945 which created a firestorm that destroyed 90 per cent of the inner city. By April 1945 the Dom cathedral stood among a sea of ruins.

the city. Although this was the largest raid in number of aircraft to Magdeburg of the entire war, it was singularly unsuccessful. Some of the main-force aircraft released their bombs early; the Pathfinders failed to concentrate their markers, and the Germans made effective use of decoy markers, causing most of the bombing to fall outside the city. Worse for the RAF, Luftwaffe night-fighters and Flak shot down 57 of the aircraft, 8.8 per cent of the force — Bomber Command’s heaviest loss of the war so far (exceeded only by the 79 aircraft lost over Leipzig a month later and the 96 over Nuremberg in March). In Magdeburg, 112 people were killed, at least 270 wounded and 1,000 made homeless. The US Eighth Air Force had joined the Allied bombing campaign in August 1942 but the first American raid on Magdeburg did not occur until February 22, 1944 — a month after the botched RAF strike — when 15 B-17s of the 1st Bomb Division dropped 42 tons of bombs on the target. This was the start of a whole series of American raids, the Eighth returning once in April, twice in May, June and August each, three times in September and once in October. These attacks invariably aimed at the city’s industrial targets — the Brabag oil plant in Rothensee, the Junkers aircraft engine works in Neustadt, the Krupp-Gruson tank factory in Buckau and the Polte munitions factory in Wilhelmstadt — and the Reichsbahn marshalling yards, but also caused extensive damage elsewhere in the city. The heaviest attack during this period was that of August 5, when 180 B-17s of the 3rd Bomb Division let loose 432 tons, killing 693 people, wounding 881 and making 13,000 others homeless. By far the most-destructive attack on Magdeburg was that on January 16, 1945. First, at mid-morning, 122 B-24s of the 2nd

Air Division dropped 236 tons of bombs on the Krupp factory and Rothensee oil plant. Then in the evening, 371 aircraft of Bomber Command’s Nos. 4, 6 and 8 Groups — 320 Halifaxes, 44 Lancasters and seven Mosquitoes — unleashed a rain of high-explosive bombs, incendiaries and aerial mines over the entire city, the carpet-bombing causing a firestorm that laid most of the inner city in ashes. Between 2,000 and 2,500 people were killed and 11,221 wounded and two-thirds of the population lost their homes. Seventeen of the bombers were lost. Raids were considerably stepped up in the first two weeks of February, five large USAAF daylight raids by several hundred B-24 heavies being alternated with nighttime attacks by much smaller forces of Mosquitoes. March saw one large USAAF raid by 219 B-24s and five nightly visits by Mosquitoes. In all, between 1940 and 1945, Magdeburg was the target of 41 bombing raids, 22 of them by the USAAF and 19 by the RAF. The near-incessant bombing of the 1944-45 period caused large numbers of the population to be evacuated or seek shelter elsewhere and by April 1945 only 90,000 people remained in the bomb-blasted city. By war’s end, 90 per cent of central Magdeburg lay in ruins. Numerous historical buildings, churches, schools, hospitals, administrative offices and business premises had been wrecked or gutted by fire. Of 106,733 homes, 40,667 (38 per cent) had been destroyed and 31,744 (30 per cent) heavily damaged, making 190,000 people homeless. Bombs had killed at least 6,000 civilians (1.7 per cent of the population — a figure that does not deviate much from that of other large German cities) and wounded 15,000 more.

CONQUER. THE STORY OF THE NINTH ARMY

MAGDEBURG

The operation that would lead to the capture Magdeburg began on April 10, when the US Ninth Army unleashed the divisions of its XIII and XIX Corps in a rapid eastward drive to the Elbe river. Their hoped-for ultimate objective was Berlin, less than 100 kilometres on, but it was not to be. THE ALLIED ADVANCE ON MAGDEBURG The operation that resulted in the American capture of Magdeburg was part of the very last Allied offensive of the campaign in the West. In the last week of March 1945, following their crossings of the Rhine river, the Allied armies began the envelopment of the Ruhr industrial area, with the US First Army, south of the Ruhr, breaking out of the Remagen bridgehead and the US Ninth Army in the north doing the same from its bridgehead south of Wesel. On April 1, Easter Sunday, the pincers snapped shut when armoured columns of the US 2nd Armored Division (from the Ninth Army) and 3rd Armored Division (from the First Army) met at the town of Lippstadt, northwest of Paderborn. Almost all of Heeresgruppe B, plus the south wing of the 1. Fallschirm-Armee — over 300,000 men — had been trapped in the Ruhr Pocket. On April 4, the Ninth Army, which had operated under command of Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery’s British 21st Army Group since December 1944, was returned to the US 12th Army Group. General Omar N. Bradley’s command now comprised four field armies — a powerful force of more than 1,300,000 troops. With these, Bradley was now to launch a new Allied main effort aimed at splitting Germany in two by linking up with the Soviet Red Army advancing from the east. The principal role in the new offensive was assigned to the First Army in the centre, a thrust directly east on Leipzig to be followed by a crossing of the Elbe east of there. The Third Army, on the right flank, was to aim for Chemnitz but be prepared to turn to the southeast later. The Ninth Army, on the left flank, was to seize a bridgehead over the Elbe near Magdeburg, and — as Bradley’s formal order of April 4 put it — ‘be prepared to continue the advance on Berlin or to the north-east’.

From this order, the Ninth Army commander, Lieutenant General William H. Simpson, and many of his subordinates construed that the Ninth Army had drawn the choice objective, the ultimate prize of the war, Berlin. They were unaware that General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, had already decided to forego a drive on the German capital and leave its capture to the Russians. The Ninth Army comprised three corps, two of which could be deployed for the eastward drive (the third formation, the XVI Corps, was engaged in mopping up the Ruhr Pocket): Major General Alvan C. Gillem’s XIII Corps (with the 5th Armored and 84th and 102nd Infantry Divisions) on the left and Major General Raymond S. McLain’s XIX Corps (with the 2nd Armored and 30th and 83rd Infantry Divisions) on the right. Advancing north of the Harz Mountains, which would form a natural boundary with the First Army on its right, the Ninth could advance across favourable terrain, an avenue of low, rolling country providing ready access to Magdeburg and the Elbe. By April 6, the Ninth Army had crossed the Weser river — the largest river between the Rhine and the Elbe and about midway of the two — and its lead formation, the 2nd Armored Division, had reached another stream 30 kilometres on, the much-smaller Leine river. General Bradley had designated this river as a stop line along which the First and Ninth Armies would first draw abreast before starting their final drive together. Thus, the 2nd Armored was ordered to halt so that the other formations of both armies could catch up. Although obligated to pause, the eager 2nd Armored made sure to seize bridges across both the Leine and another river 15 kilometres farther east before coming to a full halt east of Hildesheim the next day, April 7.

THE GERMAN SITUATION The entrapment of all of Heeresgruppe B and two corps of the 1. Fallschirm-Armee in the Ruhr Pocket had produced a huge breach in the German front. Except for local defence forces, there were virtually no troops left between the newly-created 11. Armee of General der Infanterie Otto Hitzfeld, assembling near Kassel in the south, and the remnants of the 1. Fallschirm-Armee under General der Infanterie Günther Blumentritt in the north — a yawning gap of over 100 kilometres. To plug the hole, Hitler on April 2 ordered the creation of a new army, the 12. Armee, to assemble in the Harz Mountains and from there drive to the relief of Heeresgruppe B in the Ruhr Pocket. The new command was to consist of four corps headquarters, to be withdrawn from the east, and nine divisions. In most cases named after heroes from German history, these divisions were to be formed primarily of young men from officer cadet schools, replacement training centres and the Reichsarbeitsdienst (Reich Labour Service). Most divisions would have no tanks, very little transport, only a few assault guns, and hardly any artillery. Moreover, most of the training establishments from where the troops were to come were located east of the Elbe and the troops would need time to reach the Harz. As commander of the new army Hitler on April 6 appointed General der Panzertruppen Walter Wenck. Although it looked impressive on paper, Wenck’s army was mostly a grandiose delusion in Hitler’s mind, with little base in reality. Meanwhile, Magdeburg was preparing for defence. Military command of the city was originally in the hands of the WehrmachtKommandant, who was subordinated to Wehrkreis III, the home army district. However, on March 13, Hitler appointed Generalleutnant Adolf Raegener to the position of Kampfkommandant (Combat Commander) of Magdeburg with orders to defend the city to the last. Raegener was a 40-year-old veteran officer, who had lost a leg on the Eastern 5

ATB

Left: Kampfkommandant (Combat Commander) of Magdeburg was Generalleutnant Adolf Raegener. A professional soldier since the age of 18, he had served as a battalion commander in Poland in 1939, a regimental commander in Belgium and France in 1940 and as commander of Infanterie-Regiment 9 in Russia until he was severely wounded before Moscow in December 1941, causing him to lose a leg. After recovery, he served as army instructor until late 1944 when he volunteered

more than rifles, Panzerfäuste and machine guns. However, their defence positions were boosted by a considerable number of 88mm and 20mm Flak guns taken from the city’s fixed anti-aircraft batteries, and for artillery support Raegener could call on five battalions of field howitzers stationed east of the Elbe, grouped under an artillery commander, Major Werner Pluskat. Also east of the Elbe, available as back-up reserve, stood Kampfgruppe Burg, made up of recruits from the Sturmgeschütz-Schule (assault gun training school) at the town of Burg. Commanded by Major Alfred Müller, it had a few assault guns and was about 1,500 men strong. Raegener set his troops to work on digging field works and trenches and erecting roadblocks on all main roads entering the city from north, west and south, the latter protected by the 88mm and 20mm Flak guns in an anti-tank role. All the Elbe bridges were prepared for demolition. Meanwhile, the burgomaster, Dr Fritz Markmann, and the civilian authorities set up their headquarters in the large air raid bunker at the Nordfriedhof cemetery. The atmosphere in the city was tense. Small detachments of SS men roamed the streets, keeping an eye on the morale of the troops and looking out for deserters. They also manned checkpoints on the bridges.

THE NINTH ARMY REACHES MAGDEBURG For two days, April 8-9, the divisions of Ninth Army stood waiting, straining at the bit to resume the eastward drive. The release order arrived late on the 9th, and the following morning, April 10, the formations of both the XIII and XIX Corps struck out for the Elbe. Because the army group’s orders indicated that the eventual goal was Berlin, all units took off with a special fervour, an exceptional zeal to get to the river first. From the start, the attack was a headlong dash, hardly a pursuit, for there was nothing really to pursue. Like most of the 12th Army Group, the men of the Ninth Army found they were striking into a vacuum. In the XIX Corps’ zone, the motorised infantry of the 83rd (‘Thunderbolt’) Division, commanded by Major General Robert C. Macon, on the south flank, achieved the furthest penetration, covering 35 kilometres to reach the towns of Lautenthal, Goslar and Vienenburg. In the centre, the 2nd Armored (‘Hell on Wheels’) Division, led by its tempestuous commander, Major General Isaac D. White, pushed out from north and south of Hildesheim with two combat commands abreast. Combat Command A (CCA), on the left, after moving 20 kilometres, ran into strong opposition from anti-aircraft guns arrayed to protect the Reichswerke Hermann

ATB

WILLIAM VANDIVERT

Front and in the previous weeks had been commander of the beleaguered ‘Festung’ (Fortress) Küstrin on the Oder river. Setting up his headquarters in the Encke-Kaserne in western Magdeburg, Raegener on April 7 declared the city a ‘Festung’ too. The forces at his disposal represented a mixture of proper military units and last-hour improvised outfits. The Wehrmacht troops included Festungs-Regimenter 48 and 49, each with two battalions; Pionier-Bataillon 4, with three companies; the Ersatz-Abteilung (replacement battalion) of Infanterie-Regiment Bernburg; Landesschützen-Bataillon 704 (elderly guard troops), and one company of Hungarian troops. The last-hour levy comprised a motley collection of paramilitary units: a company of OT-Regiment 116 (Organisation Todt construction workers); a Reichsarbeitsdienst battalion; 800 boys and teenagers from the local Hitlerjugend-Bann 26; and the Magdeburg Volkssturm (home guard), made up of male civilians up to the age of 65, many of whom had been forcibly rounded up NSDAP officials. Further to all that, the Polizeipräsident (Chief of Police) of Magdeburg, SS-Gruppenführer Andreas Bolek, mobilised the entire city police force in what was known as Polizei-Regiment Bolek. In all, Raegener’s garrison numbered between 2,000 and 4,000 men, for the most part poorly trained and armed with little

to return to active duty, being appointed commander of the Warthe river defence sector and then of Festung Küstrin before being sent to Magdeburg on March 13, 1945. Right: On April 13, Raegener and his staff moved their headquarters to the General-Hippel-Kaserne on General-Ludendorff-Strasse in the Herrenkrug district on the east bank of the Elbe. Today, the former military barracks on what is now named Breitscheid-Strasse houses part of the Magdeburg-Stendal High School.

Left: Taking the lead in the XIX Corps drive, the 2nd Armored Division covered the 140 kilometres to Magdeburg and the Elbe in just two days. One of the stations along its headlong dash was the small town of Osterwieck, south-east of Braunschweig, which was taken on the run by Combat Command B 6

on April 11. Surprised by the sudden arrival of the enemy, the population was out on the streets in no time. Right: Time has stood still in the picturesque streets of Osterwieck, this being the corner of Mittel-Strasse and Rosemarien-Strasse in the centre of town.

ATB

Left: That same evening, CCB’s southern column reached the town of Schönebeck on the Elbe, ten kilometres south of Magdeburg. A column of tanks commanded by Major James Hollingsworth made a run for the bridge but the Germans Göring steel plant at Salzgitter, south-west of Braunschweig, but in a brief action the onrushing tankers and armoured infantrymen destroyed or captured a total of 67 guns. Combat Command B (CCB) had an easier time, advancing for over 30 kilometres against almost no opposition, clearing the town of Ohlendorf. On the corps’ north wing, the 30th (‘Old Hickory’) Division, under Major General Leland S. Hobbs, also drove ahead vigorously, gaining between 20 and 30 kilometres and coming within six kilometres of the city of Braunschweig. The following day, the advance continued with even greater success. April 11 was a banner day for the 2nd Armored Division, the unit achieving the furthest advance on a single day in its entire history. Rolling forward with CCA on the right and CCB on the left, the division sped towards the Elbe in four great columns, each of them preceded by small detachments of armoured scout cars and Jeeps from the divisional 82nd Armored Reconnaissance Battalion. The advance was particularly striking in the zone of Combat Command B. Led by Brigadier General Sidney R. Hinds, and comprising the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 67th Armored Regiment, Companies B and G of the 41st Armored Infantry Regiment, the 78th and 92nd Armored Field Artillery Battalions and detachments of tank destroyers and engineers, the command broke free. Both commanders and men had only one thing on their mind: to get a bridge across the Elbe. Jumping off at 0630 hours in two columns, progress was rapid from the start. The righthand task force, led by Colonel Paul A. Disney, CO of the 67th Armored Regiment, attacked from near Gross Döhren and drove eastwards almost unimpeded. Sweeping aside the defenders of road-blocks with blasts from their tank guns, surprising Volkssturm defenders who could only throw down their arms and gape in bewilderment, the task force raced on relentlessly. Near Anderbeck, they encountered a 1,700man German column marching alongside the road which surrendered without putting up a fight. Driving on to Klein Oschersleben, the force stopped for two hours to re-service their vehicles, resuming their eastward march at 1700 hours. CCB’s left-hand column attacked from Schladen, destroyed an enemy lorry convoy a half hour later and continued eastward, meeting almost no opposition. The first real fight occurred 45 kilometres from the start line, at the town of Oschersleben, home of the AGO aircraft factories. Here an enemy

turned to fight and, although the Americans got to within a few metres of the span, they had to fall back in the face of determined enemy fire. The bridge was blown before a new attempt could be made. Right: The rebuilt bridge today.

Panzerfaust knocked out a self-propelled howitzer of the 92nd Armored Artillery Battalion and the Germans formed a new defensive line outside the town even though a platoon of Company D, 67th Armored Regiment, had already driven past. Continuing to the local airfield, the tankers shot down three aircraft and captured 17 FW190 fighters on the ground. After a half-hour artillery fight, the German defenders faded away and the march continued. In late afternoon a small group of armoured cars, half-tracks and Jeeps from the 1st Platoon, Company C of the 82nd Armored Recon Battalion, scouting out ahead of CCB’s northern column and led by the battalion adjutant, 1st Lieutenant Harold Douglas, reached the south-western outskirts of Magdeburg. Pushing a patrol into the suburb of Gross Ottersleben, the platoon startled German civilians and soldiers who were out on the street. Attempting to clear the way, the Americans let loose a high burst of machine-gun fire and the result was pandemonium. Women screamed and fainted; shoppers dived for cover in fearful groups or threw themselves flat on the ground, and German soldiers ran in confusion, firing wildly. Lacking the strength to hold the position, the platoon managed to push through the built-up area and emerge in open terrain at the far end. As they skirted round the southern edge of Magdeburg, continuing their eastward probe to the Elbe, they came upon the airfield that lay immediately south of the city. Swinging onto the runway, the armoured cars charged down long rows of parked fighter aircraft, shooting them up with their machine guns. Two planes came in to land and were destroyed as soon as they touched down. However, the Germans soon rallied and responded with heavy Panzerfaust and 20mm fire, pinning down the American platoon. Lieutenant Douglas radioed for help from CCB’s armour and artillery. The SP howitzers responded but the tanks of the 1st Battalion, 67th Armored Regiment, were stopped at the west end of Magdeburg by the German defenders who were now alert and were unable to relieve the stricken platoon. They finally escaped after dark, losing two half-tracks and two Jeeps and suffering some casualties. At 1700 hours sirens wailing in Magdeburg warned the population that the enemy stood before the gates of the city. Grabbing a few necessities, the civilians sought shelter in cellars and basements, many seeking refuge in one of the city’s air raid bunkers.

As CCB’s northern column was being halted on the outskirts of Magdeburg, the command’s southern column was still advancing and approaching the Elbe at the town of Schönebeck, ten kilometres to the south. When the lead tanks topped a rise overlooking the town, Major James F. Hollingsworth, the commander of the 2nd Battalion, 67th Armored Regiment, saw through his binoculars that the road bridge was still standing and that the Germans were using it to evacuate their own armour. He quickly hatched a plan with two of his company commanders, Captain James W. Starr and Captain Jack A. Knight. In the fading light, Hollingsworth led his battalion down to the road junction where the German columns turned east for the Schönebeck bridge. There, Starr’s tanks peeled off and blocked the road coming up from the south, while Hollingsworth and Knight’s company joined the tail of the enemy column heading for the bridge. The ruse could have paid off had it not been for some German artillery mounted on flatcars in the nearby railway yards, whose gunners spotted the American tanks and opened up on them. Thus alerted, a German Panther tank in front of Hollingsworth turned its turret towards the rear, taking aim at his Sherman, but his gunner, Staff Sergeant Clyde W. Cooley, fired first, blowing up the panzer which smashed into a wall and erupted in fire. Squeezing past the flaming wreck, and firing in turn at the rear of each enemy vehicle and then edging past the burning hulks, the Shermans smashed into Schönebeck. Here the tanks got involved in a chaotic battle with Germans firing Panzerfäuste from house windows. By now it was dark but, with many buildings ablaze, the scene was brightly lit as if in daytime. As his tanks pressed on to the bridge, Hollingsworth saw that the approach to it was barricaded with road-blocks through which the armour would have to zigzag in order to reach the span. Jumping from his tank to reconnoitre the ground, the major was wounded in the face by shrapnel. Undaunted, calling the riflemen from Company G, 41st Armored Infantry, forward, he led them onto the bridge approach and towards the roadblocks, all the while exchanging fire with the German defenders. Wounded a second time by a bullet in the left knee, Hollingsworth still carried on but to no avail. The enemy fire was too heavy and he was forced to order a withdrawal — less than 15 metres from the bridge. The following morning at 0830, before a new infantry attack could reach the bridge, the Germans demolished it. 7

USNA

Advancing on a parallel course further north, the 30th Division made slower progress, being held up by the necessity to take the town of Braunschweig that lay in its path. However, by April 13, they too were well on their way to the Elbe, this picture of infantrymen riding on a Sherman tank of the supporting 743rd Tank Battalion being taken in the village of Born, 37 kilometres west from Magdeburg.

BRIDGEHEAD ACROSS THE ELBE Early on April 12, Combat Command B tried to negotiate a surrender with the German authorities in Magdeburg, sending a party under a white flag into the city. They met with the Chief of Police, SS-Gruppenführer Bolek, who however flatly refused the ultimatum. When the talks failed, General White, the 2nd Armored Division commander, ordered his units to complete the sealing-off of Magdeburg, the idea being to prevent enemy troops in the city from attacking south along the west bank and thus interfere with the building of a bridge across the Elbe. The previous day, while CCB had raced ahead and secured positions on the outskirts of Magdeburg and on the Elbe, the division’s two other combat commands had followed suit but in a slower tempo. Combat Command A, led by Brigadier General John H. Collier, had spent most of April 11 mopping up the Salzgitter area south of Braunschweig. Now, acting upon General White’s order, it set out for Magdeburg. Attacking from near Wolfenbüttel at 0615, its left-hand column, known as Task Force A, by noon had covered 32 kilometres and secured the town of Helmstedt. On exiting the town, they encountered enemy small-arms and Panzerfaust fire which took considerable time to overcome. Nonetheless, by nightfall they had covered another 40 kilometres and reached positions north of Magdeburg, where despite intense fire from enemy anti-tank guns located on the east bank of the Elbe, they took up positions around the town of Barleben. CCA’s right-hand column, Task Force B, had a relative easier time, meeting almost no opposition throughout the day, and by evening had reached positions on the western edge of Magdeburg, near the suburbs of Olvenstedt and Diesdorf. Meanwhile, Combat Command R, the division’s reserve component led by Lieutenant Colonel Russell W. Jenna, moved to 8

surround the south-western and southern portions of the city, reinforcing the thin line held by the 82nd Armored Reconnaissance Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Wheeler G. Merriam). By nightfall on April 12, the 2nd Armored Division had effectively isolated Magdeburg, blocking all roads north, west and south of the city. Now CCB had its hands free to attempt a river crossing. Earlier that day, CCB forces had combed the Elbe bank, eliminating opposition and looking for a suitable bridging site. Three options were found: an old ferry site in the village of Westerhüsen, just south of Magdeburg; a barge-loading site north of Schönebeck; and a place just south of the destroyed Schönebeck bridge. Since fighting was still raging at the latter town, the ferry site was chosen. At 2100 hours that evening, using assault boats and DUKW amphibious trucks hastily brought forward, two battalions — the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 41st Armored Infantry Regiment — slipped quietly across the sprawling Elbe at Westerhüsen. Not a shot was fired from the far shore. Before dawn on April 13, the 3rd Battalion of the 30th Division’s 119th Infantry (on attachment to the 2nd Armored Division) crossed into the bridgehead as well, bringing the

ATB

Early in the day, 2nd Armored Division Headquarters had lost all contact with Combat Command B and throughout the day it had no idea of its actions or progress. The first news of its exploits to reach them was a laconic message sent by Colonel Disney from Schönebeck, which arrived shortly after 2000 that evening and electrified everyone: ‘We’re on the Elbe’. In an unparalleled armoured dash, CCB had covered 92 kilometres, 117 when measured by road, in just 14 hours.

strength there to three battalions; but no anti-tank guns, tanks or tank destroyers made it across. Judging the water near both riverbanks too shallow for vehicular ferries, the supporting engineers of the divisional 17th Armored Engineer Battalion concentrated instead on bridging the river. Construction started at 2245 but was slow in the dark, and sporadic German shelling soon interfered. With the coming of daylight the shelling increased, much of it deadly air bursts from the big antiaircraft guns at Magdeburg. The 2nd Armored’s artillery tried to neutralise the fire and the engineers laid out smoke-pots to screen the bridging site but neither effort had much effect. Call after call went back for fighter-bombers to attack the enemy artillery positions, but the race to the Elbe had carried the advance almost out of range of the Allied airfields and none showed up. Noticing that the shells came in singly, not in salvos, Colonel Disney (who had crossed to the east bank to take charge of the bridgehead force) suspected that the fire was directed by an artillery observer hidden nearby and he ordered an immediate search of the houses overlooking the river. However, nothing was found and the firing continued, deadly and accurate. Shortly after, Disney was severely wounded by shrapnel and evacuated. Despite the shelling, the engineers by midday had advanced their pontoons and treadway tracking to within 25 metres of the far shore. Then came an avalanche of shells that completely wrecked what had been built. Abandoning the site as too dangerous, the 2nd Armored’s commander, General White, directed the three infantry battalions to move after nightfall — in effect, to attack — upstream approximately five kilometres to a point opposite the demolished bridge at Schönebeck, there to form a semicircular bridgehead while a new attempt at bridging was undertaken. As daylight approached on the 14th, the 3rd Battalion, 119th (Lieutenant Colonel Carlton E. Stewart), and part of the 3rd Battalion of the 41st Armored Infantry (Lieutenant Colonel Arthur J. Anderson) were inside the village of Elbenau, about three kilometres from the river, while the 1st Battalion of the 41st (Lieutenant Colonel John W. Finnell) had cleared the riverside village of Grünewalde, immediately across from Schönebeck. Other elements were digging in on open ground to anchor the flanks. That was the situation when, in the haze of dawn, a battalion of Division ‘Scharnhorst’ — one of the divisions of Wenck’s new 12. Armee — supported by eight tanks and assault guns from

Today just a quiet little village on the B71 Haldensleben-to-Gardelegen road.

began ferrying the first vehicle across: a bulldozer to be used to shave the far bank. However, as the ferry neared the far shore, a concentration of German artillery fire severed the cable, making the ferry careen downstream in the swift current. To General Hinds on the east bank, this was the end. Aware of the plan to send CCR into the 83rd Division’s bridgehead and acutely conscious of the crisis in his own bridgehead, the failure to get tanks across, and the lack of air support, he gave the order to withdraw. Returning to the west bank, he reported his decision to his division headquarters where, in the absence of General White, he talked with the Chief-of-Staff, Colonel Gustavus A. West. General White later concurred in the order, as did the corps commander, General McLain. By late afternoon, most of the surviving infantrymen had been ferried back across the river in DUKWs in orderly fashion except for the men of Captain Leslie E. Stanford’s Company L, cut off and hiding in cellars in Elbenau. These men finally learned of the withdrawal when their artillery forward observer established radio contact with an artillery liaison plane. The forward observer called for a blanket of artillery fire on Elbenau to catch the Germans in the open. When the fire lifted, some 60 men made a break for the river. As tanks and tank destroyers fired from the west bank to cover their with-

drawal, fighter-bombers of the XXIX Tactical Air Command with auxiliary fuel tanks in place of bombs finally arrived to strafe German positions. Most of the 60 men returned safely. Through the night and the next day other survivors trickled back from the east bank, including one group of 30. Final losses totalled 330; of those only four were known killed and 20 wounded, the rest were missing, presumed captured. Although the 2nd Armored had lost its bridgehead across the Elbe, that of the 83rd Division at Barby still stood strong, and the troops there had high hopes that they would soon be sent on a final dash to Berlin. However, it was not to be. On the 15th General Simpson flew to General Bradley’s headquarters in Wiesbaden to present his plan for a drive to Berlin. After listening carefully, Bradley said he would have to telephone General Eisenhower for a decision. Being informed of the 83rd Division’s success at the Elbe, Eisenhower asked Bradley what he thought it might cost to break through from the Elbe and capture Berlin. Bradley estimated 100,000 men. Simpson overheard Bradley’s end of the conversation: ‘All right, Ike’, Bradley said, ‘that’s what I thought. I’ll tell him. Goodbye.’ To the utter disappointment of Generals Simpson, McLain and White and everybody else in Ninth Army, there was to be no drive on Berlin.

ATB

the Sturmgeschütz-Schule Burg and halftracks with towed guns launched an unexpectedly fierce counter-attack. Catching the American infantrymen in the process of setting up their bridgehead and still with no anti-tank defence other than bazookas, the Germans rapidly cut off the 119th Infantry’s Company L in Elbenau. The panzers then began systematically to reduce the defenders in the open, blasting individual foxholes one by one. In the confusion, a score of Americans surrendered. The Germans put them in front of their tanks, forcing them at gunpoint to shield their continuing advance. The bridgehead began to break apart. Looking for ways to help his beleaguered men, General White looked south. There, late on the 12th, General Macon’s 83rd Division — dubbed the ‘Rag Tag Circus’ by war correspondents because of its extensive use of captured German vehicles, military and civilian — had reached the Elbe eight kilometres upstream from Schönebeck at the town of Barby. The following day, its 329th Infantry Regiment had sent two battalions across the river in assault boats and established a second bridgehead, meeting no fire of any kind. Out of range of the enemy’s artillery at Magdeburg, the divisional engineers by nightfall had three ferries running and by 0730 on the 14th completed a treadway bridge (named ‘Truman Bridge’ after their new Commander-in-Chief, President Harry S. Truman, President Roosevelt having died the day before). With another infantry regiment and supporting armour crossing into the bridgehead, the 83rd felt confident they had opened a gateway to Berlin, now just 90 kilometres away. Noting the contrast between the two bridgeheads, General White early on the 14th ordered his reserve combat command into the 83rd’s bridgehead to immediately attack down the river’s east bank and relieve the besieged men at Grünewalde and Elbenau. General Jenna’s CCR moved out early in the afternoon, but hardly had the attack begun when word came to call it off. So desperate had the situation become in CCB’s little bridgehead that Colonel Anderson, commander of the 3rd Battalion of the 41st, in mid-morning returned to the west bank in a DUKW to report his battalion lost. He had seen his companies overrun, many men surrendering, and had only 15 men left. The CCB commander, General Hinds, now went into the bridgehead to survey the situation for himself. Engineers at the river had in the meantime been constructing a ferry, using a guide cable to anchor to the east bank, and at noon

USNA

Right: Despite the loss of the bridge at Schönebeck, the 2nd Armored Division speedily established a bridgehead across the Elbe, putting three infantry battalions across at the village of Westerhüsen during the night of April 12/13. Engineers of the 17th Armored Engineer Battalion immediately began construction of a pontoon bridge, necessary in order to get tanks and anti-tank guns across to support the infantry. Although this picture, taken by Signal Corps photographer Sergeant Lou Lindzon the following morning, gives the impression of tranquillity, work on the bridge was in fact constantly being interrupted by heavy shelling from German 88mm guns. In fact, a few minutes after Lindzon took this picture, the bridge, which by then had progressed to within 25 metres of the far shore, was wrecked by a salvo of shells, causing the Americans to abandon the site and try again a few kilometres upstream. However, the Germans attacked the flimsy bridgehead before a bridge could be completed, routing the American infantry and forcing the 2nd Armored to give up its bridgehead.

Tranquillity has returned to the old ferry site at Westerhüsen. 9

ATB

The brickyard has gone but this is the same view today, looking north into Barleben on Breiteweg.

ATB

USNA

SET-PIECE ATTACK ON THE CITY With Berlin cancelled, the only combat assignment remaining for Ninth Army’s XIX Corps was to capture Magdeburg, the last sore point left along its entire Elbe front. The reduction of a major city is an infantry job, so General McLain assigned the mission to the 30th Division. In the past few days, while the 2nd Armored and 83rd Divisions had been fighting south of Magdeburg, General Hobbs’s division, operating on the corps’ northern flank and with just two of its organic regiments on strength (the 119th Infantry was detached to the 2nd Armored Division), had been engaged in clearing the city of Braunschweig, well over 80 kilometres to the rear. It took most of two days, April 11-12, before the garrison capitulated. Leaving two battalions behind to mop up, the remainder of the division pushed on eastwards in two motorised regimental columns. The next day, April 13, they reached the Elbe north of Magdeburg, the 117th Infantry on the left occupying the riverside towns of Logätz and Loitsche and the 120th Infantry on the right relieving the 2nd Armored’s CCA around Barleben. In preparation for the assault on Magdeburg, units were reshuffled. First, on April 14, parts of CCA assumed responsibility for the south-western and southern portions of the line around the city, relieving CCR and freeing the latter to move down to Barby to reinforce the 83rd Division’s bridgehead. Then on April 14-15, the 119th Infantry was inserted to take over the south-western portion. Finally, on April 16, the 117th Infantry moved down from the Elbe to occupy the sector northwest of Magdeburg previously held by CCA. At the same time, the 30th Division’s artillery arrived to reinforce the 2nd Armored’s guns in their task of shelling the German defences and firing counterbattery missions.

USNA

Right: The operation to capture Magdeburg began on April 17, the 30th Division and part of the 2nd Armored Division planning a concentric attack into the city from three sides. Here men of the 120th Infantry Regiment form up in the town of Barleben, a few kilometres north of the city. They are on the main road at the southern end of town, the gate on the right being the entrance to the local brickworks. The photo was taken by Tec/5 Harry E. Boll of the 168th Signal Photo Company.

Left: Tec/5 Boll followed the 120th Infantry as they moved into the attack from Barleben. This shot was taken on the main road just outside the town. An M10 tank destroyer of Company B of the 823rd Tank Destroyer Battalion stands in the road, while infantrymen observe Magdeburg being 10

bombed in preparation of the assault. Right: The railing seen on the right in the wartime picture (next to the crop mark) belongs to a culvert leading a small stream underneath the road, and this pinpoints the exact spot where the photo was taken.

USNA USNA

ATB

Above: Boll’s next shot was taken a few metres on and shows the infantry advancing over the open fields to the left of the main road. The Jeep and the group of officers standing by the ‘Magdeburg 7 km’ sign can also be seen in the previous picture. Note the smoke from the preparatory bombing rising in the distance. Though powerful, the air strike did not have the desired effect since most of the bombs fell on the inner city and failed to hit the German defences on the outer rim. Right: The same spot on Barleber Chaussee. Magdeburg has grown so much that the sign now says it is just two kilometres away.

Above: A few hundred metres on, the troops cross the Hannover-to-Berlin Autobahn. Right: Today a viaduct carries the Barleber Chaussee across the A2/E30 motorway.

ATB

Meanwhile, there had been developments on the German side too. On April 13, Kampfkommandant Raegener and his staff moved their headquarters to east of the Elbe, setting up shop in the General-von-HippelKaserne in the Herrenkrug district. SS-Gruppenführer Bolek withdrew to the east bank as well, ordering most of his police force to follow him. Seeking equal safety, the local NSDAP-Kreisleiter, Oberbannführer Tichy, moved his headquarters to a building of the Hubbe & Farenholtz oil and butter factory in Friedrichstadt, also on the east side of the river. 11

USNA

USNA

the Line of Departure and the second, moving forward with the riflemen under cover of this smoke, quickly set up their mortars in positions from where they could cover the remaining distance up to the near edge of Magdeburg. Right: From their dugouts, the mortarmen observe the white smoke effectively hiding the city from view.

Moving up beyond the smoke-screen, Boll pictured tank destroyers of Company B, 823rd TD Battalion, approaching the

northern edge of Magdeburg. Smoke from the bomber attack is still rising up from the city.

USNA

Left: To provide cover for the infantrymen as they advanced over the several kilometres of exposed open terrain, 81mm mortars laid down a smoke-screen in front of the advancing troops. As the mortars’ range was not sufficient to cover the entire distance, the mortar teams were split up in two echelons. The first fired a screen about two-thirds of the way from

Right: Part of the open ground has been developed since the war but the fields to the right of the Barleben road still remain. 12

ATB

That same April 13, the SS evacuated the Jewish slave-workers employed at the Polte munitions factory on Polte-Strasse in the Wilhelmstadt district. The 3,000 women and 500 men, locked up in a satellite camp of Buchenwald concentration camp across the road from the factory, were marched out of the city under guard from SS, Volkssturm and Hitlerjugend. As they were taking a rest at the Neue Welt sports stadium on Reichspresidenten-Strasse, east of the Elbe, the column came under fire from US artillery. A panic broke out whereupon the guards shot 42 of the prisoners before driving the rest eastwards on a death march to Sachsenhausen and Ravensbrück concentration camps.

The day before, April 12, the Germans had begun demolition of the city’s Elbe bridges. The first to go up, at 1100 that morning, was the Adolf-Hitler-Brücke, the southernmost of the three road bridges in the city. Next, at 0638 on the 13th, the German engineers blew the Autobahn-Brücke, the big span on the four-lane Hannover-to-Berlin motorway just north-east of the city. Three days later, at 2230 on the 16th, they demolished the Strom-Brücke, the northernmost road bridge in the city (which had already been damaged by US artillery). Now just three spans remained: the HindenburgBrücke road bridge, the Eisenbahn-Hubbrücke (vertical-lift railway bridge) and the Herrenkrug railway bridge. When General Hobbs, the 30th Division’s commander, received the order for the capture of Magdeburg late on the 15th, this at first seemed like a fairly easy mission to accomplish and the initial plan was for the 120th Infantry to attack the city alone from the north while the other units of the division and the 2nd Armored Division contained the rest of the city perimeter. Although the earlier attempt — by CCB on April 12 — to induce the German garrison to surrender had failed, there was still some hope that the Germans could be convinced to give in, and at noon on the 16th a party led by Major Ezekial L. Glazier, the 120th’s regimental intelligence officer, went forward to find out. The party, driving into the city from the north down Reichsstrasse 81 with white flags flying on its three Jeeps, was stopped at a German road-block and, after some telephoning, two of the party — Major Glazier and 2nd Lieutenant John G. Gerl, the Assistant Regimental Operations Officer — were blindfolded and driven to the headquarters of General Raegener in the General-von-Hippel-Kaserne on the east bank of the Elbe. There they were met by Oberst Cobalt, Raegener’s Chief-of-Staff, who informed them that his general was not authorised to discuss surrender terms. The American parleys sensed that many of the Germans wished to capitulate but Cobalt’s reply was supported by the strong roadblocks they had seen and the presence of SS troops among those guarding the perimeter. Their mission unsuccessful, the Americans were escorted back to the road-block and sent on their way back to their own lines. Plans were changed: instead of one regiment, the entire 30th Division and a part of the 2nd Armored would now attack, and not just from one side but from three sides at the same time. Also, the ground assault was to be preceded by a heavy air strike, planned and organised by Brigadier General Richard E.

W. SHOAF

Right: Once inside the built-up area, the Americans met unexpectedly fierce opposition at road-blocks manned by a mixture of Wehrmacht troops, Volkssturm and Hitlerjugend. Moving up UmfassungsStrasse in the Neue Neustadt district, an M10 from the 3rd Platoon, Company B of the 823rd TD Battalion, in support of Company L of the 120th Infantry, was knocked out and set ablaze by a Panzerfaust fired by a Hitlerjugend teenager, which killed two of its crew, Corporal David Paiz and Gilbert Borel, and wounded three others. One of them, Sergeant Walter S. Clark, died the following day. Unfortunately, Umfassungs-Strasse has seen too many alterations since the war to warrant a reliable comparison.

Armour and infantry move up past the Sankt-Martins-Kirche on the corner of DräseckePlatz and Salzwedeler Strasse in the Neue Altstadt district. This picture comes from the scrapbook of Staff Sergeant W. Shoaf of Company I, 3rd Battalion, 120th Infantry.

ATB

Right: Heavily damaged by wartime bombing, St Martin’s Church stood until 1959 when the municipal authorities blew up the ruins, replacing it with a bland apartment block. However, the fence of the parish-house across the street, with its well-recognisable stone posts, remains to confirm the comparison. 13

ATB

With additional dock facilities built elsewhere, the Handelshafen today stands largely abandoned. However, the large warehouse and grain silo seen at its southern end have been completely rehabilitated and are today part of a science and research centre of Magdeburg University.

ATB

OLDHICKORY.COM

Nugent, the commander of the XXIX Tactical Air Command (the component of the US Ninth Air Force supporting the Ninth Army). Nugent intended to not only use all of his command’s 375 fighter-bombers (five groups), but in addition called on the Ninth Air Force to lend the support of its medium bombers. Because of the complete lack of medium bomber targets anywhere else along the Western Front, Major General Hoyt Vandenberg, the Ninth Air Force commander, decided to place the entire strength of his 9th Bombardment Division — 11 groups of B-26 medium bombers, 350 aircraft in all — at the disposal of the Ninth Army and XXIX TAC for the Magdeburg operation. The air plan called for the fighter-bombers to attack the city immediately before and after the assault by the mediums. The strike preceding the bombers was intended to make the defenders keep their heads low and thus prevent them from observing that parts of the American ground forces were pulling their forward units back to a safe distance from the bomber zone. The fighter-bomber strikes following the medium bombing were to maintain pressure on the enemy and allow the ground forces to regain the vacated positions prior to going into the assault. There was even hope that the air attack might deflate German morale enough to cause them to capitulate. General Hobbs issued his orders for the attack, Field Order No. 70, at 0200. The air strike was to begin at 1045 and the ground attack was to start at 1315.

W. SHOAF

Right: A few blocks further on, the troops reached the Handelshafen, the commercial port basin in the Neue Altstadt, one of several harbour inlets of the Elbe river in Magdeburg. As the GIs move along the western quay, they can see the span of the Hindenburg-Brücke in the far distance still intact. The last road bridge left over the Elbe in Magdeburg, it will be blown in the Americans’ face the following afternoon. This is another photo from the scrapbook of Sergeant Shoaf.

Left: While the 120th Infantry attacked from the north, the 117th Infantry pushed into the city from the north-west. Here a column of troop-laden trucks passes the junction of Weissengrund and Helmstedter Chaussee in the suburb of Olvenstedt. 14

The German defenders had sealed off this commune with two road-blocks protected by three 88mm guns, one of which was emplaced at this junction. Right: The same junction today, looking south. The column was returning from the city centre.

USNA

For lack of an upstairs window we had to take our comparison from ground level.

ATB

USNA

APRIL 17 By the morning of Wednesday, April 17, the 30th Division and part of the 2nd Armored stood poised in a semicircle around Magdeburg, ready to launch a concentric attack into the city. In the north was the 120th Infantry (Colonel Branner P. Purdue). The regimental objective was the northern section of the city, which included the districts of Neue Neustadt, Kolonie Eichenwetter, Alte Neustadt and Nordfront. For armoured support they would have the Sherman tanks of Companies B and C of the 743rd Tank Battalion and tank destroyers of Company B, 823rd Tank Destroyer Battalion. In the north-west stood the 117th Infantry (Colonel Walther M. Johnson), with Company A of the 743rd Tank Battalion and Company A of the 823rd TD Battalion in support. Their task was to drive through the suburb of Olvenstedt, take the town district of Wilhelmstadt and capture the heart of the city, the Altstadt.

took this picture on Halberstädter Chaussee at its junction with Diesdorfer Graseweg in the suburb of Ottersleben. Smoke from the preparatory bombing is rising from the city as tanks from the 1st Battalion, 66th Armored Regiment, accompany the infantry forward.

ATB

The 30th Division’s third regiment, the 119th Infantry, drove into the city from the west and south-west, its right-hand 1st Battalion operating under command of Combat Command A of the 2nd Armored Division. Accompanying the latter force was Signal Corps photographer Sergeant Edward M. Du Tiel, who

Left: More troops of the 119th Infantry moving forward in Ottersleben. They are on Schlageter-Strasse (named after the Nazi Party martyr Albert Leo Schlageter), which is the street running behind the buildings on the right in the previous picture. Right: Schlageter-Strasse is today named Bebel-Strasse.

With this part of Germany having changed from Kaiserreich to Weimar Republic to Third Reich to German Democratic Republic to Bundesrepublik, all in the course of one century, it is no wonder that numerous streets in Magdeburg have seen their name changed several times over the decades. 15

WILLIAM VANDIVERT

Just over to the right of the Lindenhof lay a quarters known as the SA-DankopferSiedlung (SA Thankoffering Settlement). Designed by the architectural firm of Baumann & Runge and built in 1937-38, it had been commissioned by the SA-Hauptamt (SA Main Office) in Munich to accommodate families of ‘alte Kämpfer’ (early members of the Nazi Party’s Sturm-Abteilung) and First World War veterans. Here the armoured infantry, covered by machine guns from their M5 half-tracks, approach the south-western corner of the settlement.

ATB

WILLIAM VANDIVERT

In the west was the 119th Infantry (Colonel Russell A. Baker). The regiment had only two of its organic battalions on hand; the 1st Battalion, although in an adjacent sector on the right, was detached to the 2nd Armored’s CCA. The 119th’s mission was to take the western town district of Diesdorf, a task in which it would be assisted by the 2nd Battalion of the 66th Armored Regiment (on loan from CCA) and Company C of the 823rd Tank Destroyer Battalion. Standing ready along the south-western and southern part of the line was Brigadier General Collier’s Combat Command A, comprising the 1st Battalion of the 119th Infantry and the 2nd Battalion of the 41st Armored Infantry, supported by the armour of the 1st Battalion of the 66th Armored Regiment. Put under command of the 30th Division for the operation, they were to attack and capture the south-western borough of Sudenburg and the southern districts of Lindenhof, Hopfengarten and Buckau. The air preparation, planned to start at 1045, was held back because of excessive ground haze and finally went in at 1145. Coming in wave after wave, a total of 350 medium bombers dropped 775 tons of high explosive on the city. The three-hour air

the war and were typical examples of Nazi housing estates. Vandivert’s first shot showed Shermans of the 66th Armored Regiment with armoured infantry riding on the decks rolling forward to the Werksiedlung (factory settlement) am Lindenhof. This was an area of two-storey tenement blocks built especially for the workers of the nearby Krupp-Gruson tank factory. Note the smoke from the pre-assault bombing rising above the houses. These particular blocks stood along what is today Marderweg.

WILLIAM VANDIVERT

The attack from the south was carried out by the 2nd Battalion of the 41st Armored Infantry Regiment of the 2nd Armored Division. Accompanying the unit into battle was William Vandivert, a veteran war photographer from Life magazine, whose series of exposures gives a remarkable close-up view of the advance. The company that Vandivert followed into action had as its first objective two residential areas immediately east of the Leipziger Strasse thoroughfare. Both of these had been built shortly before

Left: As the troops close in, they appear to meet little opposition. Right: A few new houses have been built on the outer 16

edge of the commune since the war but this is the exact same view today.

ATB

Naturally, the name SA-Dankopfer-Siedlung had to go after the war and the quarters is today known under the more-neutral name Siedlung Fuchsbreite. Also, all the street names were changed in 1950, and Marienbader Strasse is today called Bienenweg. reached the first main intersection in Neue Altstadt, that of Lübecker Strasse with Hundisburger Strasse/Kastanien-Strasse. Here, small-arms fire, an occasional Panzerfaust, and 20mm fire forced the men to take cover and the advance slowed considerably. Another road-block at the next crossroads

(Lübecker Strasse/Neuhaldensleber Strasse), covered by two 88mm guns, practically brought the battalion to a standstill. Company L’s forward platoon became isolated, and a platoon leader and several squad leaders got killed or wounded before contact could be regained. The supporting armour

ATB

WILLIAM VANDIVERT

strike appeared to have little effect, primarily because it was aimed at the already wellbombed centre of town and not at the enemy defensive positions, which were scattered in a deep belt around the outskirts. As the last of the B-26s departed, the American divebombers and artillery took over, hitting known German battery positions, fuel dumps and other targets. Postponed by the belated air strike, the ground attack did not jump off at the same time everywhere, CCA already starting at 1445 but the 30th Division not until 1510. Just before it was about to begin, the American commanders learned that there were large chemical warehouses in the city but it was too late to equip the men with gas masks. The 120th Infantry in the north had formed up in the town of Barleben. Start line of the attack was the Hannover-to-Berlin Autobahn, some two kilometres distant from the northern edge of Magdeburg. Colonel Purdue planned to attack into the city with only one battalion up front, the 3rd (Major Chris McCullough), with the 1st and 2nd Battalions grouped behind and ready to assist. However, the regiment would start the assault by taking two intermediate objectives: Company K of the 3rd would advance to a point, code-named ‘Harold’, about a kilometre south of the Autobahn and just short of the built-up area, where it would halt for a few minutes and carry out a final reconnaissance for the battalion’s main attack into the city. At the same time, further on the left, Company G of the 2nd Battalion would advance to capture objective ‘Teen’, the cluster of railway tracks running through the north-eastern suburb of Rothensee, in order to secure the regiment’s left flank. The attack went off to a good start. At 1510, Company K crossed the Autobahn and, moving across the flat open ground, protected by smoke-screens laid down by supporting 81mm mortars, within half an hour reached ‘Harold’. There was a brief halt while the rest of the 3rd Battalion, with a platoon of tanks and one of tank destroyers, came forward along the exposed main road from Barleben. Meanwhile, on the left, Company G secured ‘Teen’ without meeting much resistance. Now, all was ready for the main attack into the city At 1545, while smoke from the bombing still curled up from the skyline, the 3rd Battalion moved off, with Company L on the right of the main road and Company I on the left. There was no opposition until the troops

WILLIAM VANDIVERT

Right: Having entered the built-up area, the riflemen proceed north up the first street, Marienbader Strasse. The house on the right, with the electricity post in front, is the same one as seen in the centre of the previous shot.

Left: Meanwhile, another platoon moved to clear the southern part of the settlement, turning the corner of Marienbader Strasse and Brüxer-Strasse. The houses in the background

stand on Ascher-Strasse. Another fire from the bombing rages in the far distance. Right: Brüxer-Strasse is today Libellenweg and Ascher-Strasse is now named Grillenstieg. 17

WILLIAM VANDIVERT

Right: Moving up with the platoon, Vandivert pictured them passing AscherStrasse. Comprising a grid of three eastwest and five north-south streets, the whole SA settlement contained 153 family homes, most of them rented houses and just four privately owned. They included several types of standardised designs (socalled Einheitstypen), about half of them for single families, the rest for two families. The houses on this side of AscherStrasse were all Einheitstyp AET 73.

ATB

edged into alleys and side streets to escape the 88mm fire but still suffered losses: moving up Umfassungs-Strasse, an M10 tank destroyer from 3rd Platoon, Company B of the 823rd TD Battalion, in support of Company L, was knocked out and set ablaze by a Panzerfaust, killing two of its crew, Corporal David Paiz and Gilbert Borel, and wounding three others, one of whom, Sergeant Walter S. Clark, died the following day. At one point, the tanks of 3rd Platoon, Company B, 743rd, were held up by a stone

ATB

WILLIAM VANDIVERT

Right: Looking south on Grillenstieg today.

Left: Proceeding deeper into the settlement, the same platoon moves up Karlsbader Strasse. All rented houses in the settlement had an attached stable for small animals and a hayloft. 18

Evidence of Germany’s preparation for war was that about a quarter of them were fitted out with an inbuilt air raid shelter. Right: Karlsbader Strasse is today called Wespenstieg.

WILLIAM VANDIVERT ATB

As the platoon reaches the end of the street, they take cover against snipers.

The house they are crouching outside is an Einheitstyp BET 1, of which there were only two in the whole settlement, at the northern end of Karlsbader Strasse/Wespenstieg. Unfortunately, the house in Vandivert’s picture — No. 1 — has been replaced by a modern house, so we have taken our comparison at No. 2. observed targets and to block intersections after they had been passed. By 2115 hours, the 120th Infantry had cleared most of the Neue Neustadt district and reached an east-west regimental phase

line code-named ‘Pork’. Here, the 1st and 3rd Battalions halted and took up defensive positions for the night. Casualties had been considerable, the 3rd Battalion alone having lost 23 men.

ATB

WILLIAM VANDIVERT

wall and a Sherman tankdozer was called forward to push it over, allowing the armour to break into a street. However, once there, the tanks found themselves without any infantry protection. The platoon commander, Lieutenant Carroll E. Hibnes, jumped from his tank in order to contact the riflemen, but he was shot in the back by a sniper. Medics evacuated him to the rear. The infantry were at last contacted and the tank platoon split in two sections, each advancing down a different street. With the 3rd Battalion meeting heavier resistance than expected, Colonel Purdue at 1650 ordered the 1st Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Ellis W. Williamson) to deploy to the right of the 3rd. This battalion had been following behind the 3rd, its Company A riding on the decks of the Shermans of Company C, 743rd, and its Company C moving abreast on the left of the road. Accordingly, Company A dismounted at ‘Harold’ and from there moved south in two columns along different streets about half a kilometre apart, the Mittelweg and the Lerchenwuhne. Behind each column followed a reinforced company — Company C with two platoons of tanks on the right and Company B with one platoon of tanks on the left. As they probed forward, the lead 2nd Platoon encountered a road-block consisting of a dozen wagons piled on top of each other. The platoon leader, Lieutenant Walter T. Johnson, led his men around the barricade and returned to report it unoccupied whereupon two tanks were sent forward to break through the obstacle. However, just then two Panzerfaust projectiles were fired. One of them disabled the lead Sherman with a hit through the turret, the penetration wounding the tank commander, 1st Lieutenant Bernard W. Fruhwirth, and the cannoneer, Pfc Robert G. Andrews, and killing the gunner, Corporal Richard E. Davis. The explosion of the other Panzerfaust wounded Lieutenant Johnson. Despite the heavy enemy fire, two medics, Pfc Herman Gershon and Herbert F. Schain, ran forward under a Red Cross flag and brought the wounded men to safety. Fighting around the road-block continued into dusk. Combing through the rubble, searching large apartment houses room by room, and mopping up was a laborious process and took time. Artillery, which had showered the city heavily in the days preceding the attack, was of little use in the close-quarter fighting, and 60mm and 81mm mortars proved the most-effective weapons to support the infantry. Another problem was that the direction of attack was often contrary to the direction of streets, necessitating numerous changes in direction, forcing one unit to hold while another moved rapidly in an arc. It was difficult to manoeuvre tanks and tank destroyers to give close support, and their role was mostly limited to laying fire on

Left: Having reached the northernmost diagonal street, Gablonzer Strasse, the GIs cautiously proceed through the gardens. Note the

damage to the roofs from shelling and bombing. Right: Seven decades later the street is named Hamsterbreite. 19

ATB

WILLIAM VANDIVERT

Left: Having cleaned out the SA settlement, the 41st Armored Infantry moved into the next neighbourhood, Hopfengarten, an area of more-luxurious villas and tenements, where they met stiffer opposition. Vandivert pictured a GI guarding five captured Germans sitting, as he noted in his caption, ‘in the lee of

Right: Taken in the same district, this is Hopfenbreite (formerly Cäcilien-Strasse), just past its intersection with LärchenStrasse, looking south-west. The house with the curved roof on the left survives to confirm the comparison. 20

methodically cleared the area. By 2100 hours they had reached their objective, the line of the Sedan-Ring, about two kilometres inside the built-up area, and there consolidated positions for the night.

WILLIAM VANDIVERT

1st Platoon of the supporting Company C, 823rd, destroyed one of the guns, expending ten HE rounds on the target. Steadily pushing forward, through the residential streets of the Hermann-Beims-Siedlung, the battalion

Finishing up his coverage of the day, Vandivert pictured a Sherman of the 66th Armored Regiment rolling through an area heavily affected by the preparatory bombing and shelling.

ATB

Colonel Johnson’s 117th Infantry, attacking from the north-west with the 1st Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Robert T. Frankland) on the right and the 2nd (Lieutenant Colonel Ben T. Ammons) on the left, pushed into Olvenstedt and, using the Olvenstedter Chaussee as it main axis, drove forward into Wilhelmstadt. As elsewhere, the Germans defended with what they had, road-blocks built around machine guns and anti-tank guns, and snipers hidden in the rubble, armed with rifles and Panzerfäuste. Wagons or tramcars filed with dirt were used to block roads. Not all defences had been completed before the assault began and in some places the Americans overran labour details still working on anti-tank ditches and road barricades. At the road-block on Olvenstedter Platz, Hitlerjugend teenagers came rushing out towards the Americans, firing wildly until they were mowed down. An M10 from Company A of the 823rd TD Battalion engaged an enemy 88mm antitank gun, needing four high-explosive rounds to finish it off. A Sherman from 2nd Lieutenant Donald L. Mason’s 1st Platoon of Company A, 743rd tanks, moving up with the 1st Battalion, knocked out another. Steadily, the regiment drove forwards from one phase line to the next. At 1650, Colonel Johnson committed the 3rd Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Samuel T. McDowell), ordering it to secure the left flank behind the 2nd Battalion and send out patrols to contact the 120th Infantry. By nightfall, the forward battalions had reached phase line ‘Jig’, about halfway through the Wilhelmstadt district, and settled down for the night. Colonel Baker’s 119th Infantry Regiment, attacking from due west, jumped off at 1515 with its 2nd Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Hal D. McCown) and 3rd Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Stewart’s unit, hardly recuperated from its difficult time in the Westerhüsen bridgehead three days earlier). Side by side, they pushed forward through the Diesdorf suburb, meeting only slight resistance. However, as they moved through the large Westfriedhof cemetery south-east of there, they encountered stubborn resistance from road-blocks manned by Volkssturm and Hitlerjugend troops armed with Panzerfäuste and small arms and covered by three 88mm guns. An M10 tank destroyer from the

a house about 100 feet from a street-fight’. The man on the right is a Luftwaffe soldier. Right: It took some time to find the spot, but the prisoners were sitting on the corner of Birkenweg. The view is looking across a diagonal street, Lindenweg, into Rüsternweg.

10

1

9

2

15

11

12 16

8

13 17 14

3 7

5 4

6

Wartime Allied map of Magdeburg showing the main locations in our story. [1] Barleber Chaussee. [2] Olvenstedter Chaussee. [3] Halberstädter Chaussee. [4] Leipziger Strasse. [5] SA-DankopferSiedlung. [6] Schönebecker Strasse. [7] Krupp-Gruson tank factory.

[8] Polte munitions factory. [9] Junkers aero engine factory. [10] Brabag synthetic oil refineries. [11] Hindenburg-Brücke. [12] Strom-Brücke. [13] Hubbrücke. [14] Adolf-Hitler-Brücke. [15] General-von-Hippel-Kaserne. [16] Dom cathedral. [17] Justizpalast. 21

Right: While one part of the 41st Armored Infantry struck at the SA settlement and Hopfengarten, two kilo metres further east, on the other side of the Leipzig-to-Magdeburg railway line, another part of the regiment attacked into the city from the south-east. Their axis of advance was the main road which led into the city from Westerhüsen. Accompanying this force was Signal Corps photographer Sergeant Lou Lindzon, who took this picture of an M8 light tank with a public address speaker mounted on its turret to call for surrender of the enemy troops. By this stage of the war, such tactics were often used, soldiers of German descent being used to broadcast the messages.

USNA