Beyond Hawai'i: Native Labor in the Pacific World 9780520967960

In the century from the death of Captain James Cook in 1779 to the rise of the sugar plantations in the 1870s, thousands

222 33 5MB

English Pages 320 [317] Year 2018

Contents

Maps

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1. Boki’s Predicament: Sandalwood and the China Trade

2. Make’s Dance: Migrant Workers and Migratory Animals

3. Kealoha in the Arctic: Whale Blubber and Human Bodies

4. Kailiopio and the Tropicbird: Life and Labor on a Guano Island

5. Nahoa’s Tears: Gold, Dreams, and Diaspora in California

6. Beckwith’s Pilikia: “Kanakas” and “Coolies” on Haiku Plantation

Epilogue: Legacies of Capitalism and Colonialism

Appendix

Notes

Glossary

Bibliography

Index

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Gregory Rosenthal

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

Beyond Hawai‘ i

This page intentionally left blank

Beyond Hawai‘ i native labor in the pacific world

Gregory Rosenthal

university of califor nia pr ess

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2018 by Gregory Rosenthal Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Rosenthal, Gregory, 1983– author. Title: Beyond Hawai‘i : native labor in the Pacific world / Gregory Rosenthal. Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Identifiers: lccn 2017056075 (print) | lccn 2018003856 (ebook) | isbn 9780520967960 (epub) | isbn 9780520295063 (cloth : alk. paper) | isbn 9780520295070 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Indigenous labor—History. | Hawaiians—Pacific Area— History. | Hawaii—Emigration and immigration—History—18th century. | Hawaii—Emigration and immigration—History—19th century. Classification: lcc hd8930.7 (ebook) | lcc hd8930.7 .R67 2018 (print) | ddc 331.6/2969009034—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017056075 Manufactured in the United States of America 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

18

con t en ts

Maps vi Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 • Boki’s Predicament 16 Sandalwood and the China Trade 2 • Make’s Dance 48 Migrant Workers and Migratory Animals 3 • Kealoha in the Arctic 82 Whale Blubber and Human Bodies 4

Kailiopio and the Tropicbird 105 Life and Labor on a Guano Island •

5 • Nahoa’s Tears 132 Gold, Dreams, and Diaspora in California 6 • Beckwith’s Pilikia 166 “Kanakas” and “Coolies” on Haiku Plantation Epilogue 203 Legacies of Capitalism and Colonialism Appendix 209 Notes 211 Glossary 267 Bibliography 271 Index 295

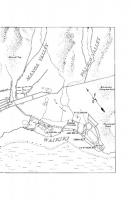

Wainwright Cape Hawaii

Point Barrow

Bering Sea Northwest Coast California (see California map) Hawai‘i (see Hawai‘i map) Guangzhou

New England

Baja Mazatlán California San Blas

Howland Island Baker Island Jarvis Island

P A C I F I C O C E A N

map 1. Map of the Pacific World, showing places mentioned in the text. Map by Bill Nelson.

P A C I F I C O C E A N

KAUA‘I NI‘IHAU O‘AHU

Honolulu

MOLOKA‘I Lāhainā LĀNA‘I

Ha‘ikū MAUI

KAHO‘OLAWE

P A C I F I C O C E A N

Hilo HAWAI‘I

map 2. Map of the principal Hawaiian Islands, showing places mentioned in the text. Map by Bill Nelson.

Vernon Coloma Sacramento San Francisco

P A C I F I C O C E A N

Santa Rosa Island

San Diego

map 3. Map of California, showing places mentioned in the text. Map by Bill Nelson.

ack now l e dgm en ts

This book would not have been possible without the assistance of countless friends, colleagues, and mentors. I began the research for this book nearly a decade ago under the mentorship of Christopher Sellers at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. Chris taught me to see history through intersecting lenses of environment, labor, class, health, and the human body, all in transnational perspective. Jared Farmer, Iona ManCheong, and Jenny Newell rounded out my dissertation committee. All three are phenomenal scholars (of the U.S., China, and the Pacific, respectively) who guided my research at crucial moments. The entire history faculty at Stony Brook was supportive and inspirational, providing an intellectual home over six years of tremendous growth and change. They also provided financial support through teaching appointments, assistantships, and funds for conference travel and research. Fellow graduate students—particularly Bill Demarest, Raquel Alicia Otheguy, and Carlos Gómez Florentín—also provided a social environs for this ever-commuting comrade, both on the LIRR train and in New York City. Thank you, as well, to Michael Zweig, who hired me to work at the Center for Study of Working Class Life. Since moving to Virginia my colleagues at Roanoke College have been unequivocally supportive and encouraging as I have finished this project. Thank you particularly to current and former chairs Jason Hawke and Whitney Leeson, as well as Dean of the College Richard Smith. The department and the college have provided funds for me to attend conferences and conduct additional research in Hawaiʻi. This book is the product of Roanoke’s supportive research environment. I have also benefited from the tremendous mentorship, comradery, and criticism of colleagues from across the United States and the world. These ix

include, in no particular order, Seth Archer, Larry Kessler, Hiʻilei Julia Hobart, Laurel Turbin Mei-Singh, Ted Melillo, Lissa Wadewitz, Ben Madley, Bathsheba Demuth, Thomas Andrews, David Chang, Greg Cushman, Doug Sackman, David Chappell, Ty Tengan, Josh Reid, Anna Zeide, Marika Plater, Kristin Wintersteen, Frank Zelko, Kieko Matteson, Kara Schlichting, Catherine McNeur, Melanie Keichle, Kendra SmithHoward, and so many others. I am particularly grateful to David Igler and Ryan Tucker Jones, both of whom carefully read and provided extensive feedback on the entire manuscript in its penultimate form. In Hawaiʻi, thank you to the East-West Center; the Hamilton Library at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, particularly librarians Dore Minatodani and Kapena Shim; the Hawaiʻi State Archives; the Bishop Museum; the Hawaiian Mission Children’s Society; and the Hawaiian Historical Society. Mahalo nui loa to Manuwai Peters, Pōmai Stone, Puakea Nogelmeier, and Richard Keao NeSmith for their assistance with Hawaiian-language learning, translations, and proofreading. Thank you to Nora, Josh, and Safiya, for friendship. In California, thank you to The Huntington Library; The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley; and the California Historical Society. Thank you to the Berkeley YMCA, and to Lynn and Marjeela, for friendship. In New England, thank you to the Massachusetts Historical Society; the Houghton Library at Harvard University; the Baker Library at Harvard Business School; and Mystic Seaport. Thank you to Steve Trombulak for hiring me as a visiting instructor at Middlebury College. Thank you to Anne and Davida, for friendship. In New York, thank you to the New York Public Library and the NewYork Historical Society. Special thanks to the people’s library—the Brooklyn Public Library—where I wrote this final draft. Thank you to Free UniversityNYC comrades, and to Conor, Michael, Lyra, and Ruby for friendship. Particularly great gratitude goes to Caroline, my brother James, and my parents Robin and Kimmo. In Virginia, big shout out to my queer family, especially Rachel. I have received generous financial support from the American Council of Learned Societies, the American Historical Association, The Bancroft Library, The Huntington Library, the New England Regional Fellowship Consortium, the State University of New York at Stony Brook, and Roanoke College. x

•

Ac k now l e d g m e n t s

At the University of California Press, thank you to my editor Niels Hooper, assistant editor Bradley Depew, project editor Kate Hoffman, and marketing manager Jolene Torr. Thank you also to copyeditor Kathleen MacDougall, cartographer Bill Nelson, and indexer François Trahan. It has been a pleasure and a privilege to work with you all. This book is about migrant workers and global capitalism. It is dedicated to my parents, grandparents, great-grandparents. My ancestors came across the Atlantic Ocean on boats. They were diasporic seeds, brave sojourners, working class heroes. This is for them.

ac k now l e d g m e n t s

•

xi

This page intentionally left blank

Introduction what does globalization look like? How does capitalism feel? To the sandalwood cutter, it was 133 pounds of wood strapped on his back, stumbling down a steep mountain path on his way to the sea. To the whale worker, it was bruises on his body; it was the songs he sang about whales, warships, and about coming up short. Kealoha felt it trembling under his skin; it was cold and unforgettable. Kailiopio heard it in the millions of birds screaming and cawing above his head. To the gold miner, it was hunger and embarrassment. Nahoa felt it in the warm tears streaming down his face. The plantation worker felt it in his stomach, in the strange foods that he ate. Hawaiian workers experienced globalization and capitalism in their bodies. In the century from the death of Captain James Cook in 1779 to the rise of the sugar plantations in the 1870s, thousands of Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) men left Hawaiʻi to work on ships at sea and in nā ʻāina ʻē (foreign lands). Through labor, these men bridged islands and continents; they wove together a world of economic, demographic, and ecological exchanges; and they wrote about their experiences abroad in Hawaiian-language newspapers that traveled home and back out again across a transoceanic diaspora. Hawaiian men extracted sea otter furs, sandalwood, bird guano, whale oil, cattle hides, gold, and other commodities. The things they made and the stories they told traveled to every corner of the Pacific Ocean, from China in the west to the equatorial Line Islands in the south to Mexico in the east to the Arctic Ocean in the north. This is the story of the rise and fall of the Hawaiian worker in the nineteenth century. It is a story of transoceanic capitalist integration, and the story of how the world’s greatest ocean became a “Hawaiian Pacific World”—the world that Hawaiian labor made. 1

Historians of Hawaiʻi and the Pacific have tended to ignore this narrative: how Hawaiʻi’s integration into a global capitalist economy in the nineteenth century was propelled by the labor of thousands of Native men who left Hawaiʻi in pursuit of wages and opportunity abroad. Historians have long focused on the complex relations among aliʻi (chiefs) and haole (foreigner) elites, consequently sidestepping investigations of the makaʻāinana (commoners), the indigenous workers and their experiences of capitalism.1 Labor historians have written at great length about Hawaiʻi’s immigrant work force, including Chinese, Japanese, Portuguese, and Filipina/o workers, but less is known about Hawaiʻi’s indigenous workers, including those Native men and women who left Hawaiʻi to pursue work on ships at sea and in foreign lands.2 Pacific World historians have traced the movement of ships, goods, plants, animals, and diseases across the vast ocean, but Native workers are rarely accounted for as agents peopling those diasporas and traveling those circulations.3 This book is a study of the formation of Hawaiʻi’s indigenous working class in an era of early capitalist expansion and globalization. Here, Hawaiian migrant workers take center stage. Through both work and words, Hawaiian labor linked disparate peoples, places, and processes together, making the Pacific into a “world.”

the “kanaka” body Hawaiian workers were known as “kanakas.” The term kanaka (singular) / kānaka (plural) is Hawaiian for “person” or “people.” In the nineteenth century, Europeans and Euro-Americans circumscribed this term’s meaning to more specifically refer to a Native Hawaiian male worker. By the end of the century it was used throughout the Pacific World to refer to all manner of Pacific Islander workers. The “kanaka” represented a racialized, classed, and gendered body, the creation of a Western capitalist imagination that saw the world’s peoples as pools of labor fit for the global economy.4 Eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Hawaiian leaders seem to have occasionally used kanaka as a term designating a male servant to an aliʻi, which perhaps informed how and why outsiders began to use this term.5 Some Hawaiians also seemingly embraced the term kanaka and their application of the term may have informed Euro-American understandings.6 More frequently “kanaka” was used by outsiders as a derogatory label. The idea of the kanaka in the nineteenth century was born of the marriage of a Western capitalist 2

•

I n t roduc t ion

political economy with indigenous Hawaiian paradigms of class, labor, and personhood.7 Beginning in the 1810s and 1820s, capitalist and Christian values combined to engender a new body discourse in Hawaiʻi. The large size of many aliʻi bodies in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was, for many Hawaiians, an indigenous expression of mana (divine power); one’s corporeality marked his or her legitimacy to rule over the people and the land.8 A rival discourse developed under capitalism in which strong, lean, and muscular male bodies were valued as commodities in the global labor marketplace. Foreign employers and missionaries alike saw the body not so much as an expression of spiritual power (mana) but of labor power. An indigenous system of corporeal class politics based on fatness was replaced by a new regime of fitness.9 At least three racial stereotypes defined the kanaka body in the Western mind. To many employers and other foreigners, Hawaiians were an “amphibious” race, “nearly as much at home in the water as on dry land.”10 This meant that Hawaiian workers were seen as particularly fit—that is, suitable or adaptable—for labor in marine and maritime work environments. Th is racial imaginary—certainly influenced by foreigners’ surprise at Native bathing, surfing, and fishing cultures—influenced Hawaiian work experiences all across the Pacific, where workers were frequently charged with labors that involved swimming, diving, and boating.11 Second, Hawaiians were considered innately indolent. Many foreigners blamed this on the climate, thereby racializing tropicality as the combination of listless bodies with an enervating environment.12 This discourse of tropical indolence legitimated Christian missionaries’ efforts to destroy indigenous systems of labor and domestic production; only capitalism could turn so-called lazy kanakas into industrious citizens. Employers likewise reasoned that indolence had to be driven out of the kanaka; left to his own devices, he simply would not work.13 Third, the kanaka body was seen as a diseased body. By mid-century, both aliʻi and influential foreigners were consumed by a discourse predicting apocalyptic population decline. True, Hawaiians were dying at an alarming rate from foreign epidemics, but the racialization and commodification of the kanaka also framed disease as a market liability.14 One of the reasons why the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi eventually turned to importing foreign labor was the government’s belief that the Native kanaka would not survive long enough to sustain the economy and preserve the lāhui (nation).15 All told, the presumed brute strength and “amphibious” dexterity of Hawaiian male I n t roduc t ion

•

3

workers made the kanaka an attractive worker, while his simultaneous penchant for indolence and susceptibility to disease made him a less than ideal partner in global commerce. Yet for the kanaka himself, being a worker in the capitalist economy was not so much about the raced, classed, and gendered limitations of his body, or the inherent strengths or weaknesses of his corporeal nature. To him, work was about survival, and also about working-class power and possibility in a world suddenly turned upside down. Against narratives of indigenous rootedness in ka ʻāina (the land)—narratives that privilege stories of demographic and environmental collapse, victimization, and dispossession—we might follow an approach first charted by Epeli Hauʻofa and since developed by Kealani Cook, David A. Chang, and others, to tell stories of indigenous routedness on the ocean. Rather than facing colonization and in situ victimization, thousands of Hawaiian workers challenged their Native leaders and the state as well as haole employers and imperial usurpers alike by moving their bodies along pathways opened up by globalization. Movement, migration, and mobility were not signs of defeat for the Hawaiian people but rather historical examples of working-class agency in Hawaiʻi and beyond.16 These stories have the power to “re-member” Hawaiian working-class men to nineteenth-century history. Against the debilitating, emasculating discourse of the deformed kanaka body—which Ty P. Kāwika Tengan has shown can be re-membered through indigenous articulations of Native masculinities—and the “dismembered” Hawaiian body politic (ka lāhui)— building on Jonathan Kay Kamakawiwoʻole Osorio’s terms—this book’s narrative of Hawaiian migrant labor is the story of physically capable and cosmopolitan workers who created a transoceanic diaspora spreading out across the world’s greatest ocean, bringing Hawaiʻi into the global economy and forever reshaping Hawaiian history, politics, and culture.17 Yet these men are routinely left out of narratives of the Hawaiian nation and Hawaiian history, and this omission has grave consequences. If that which made the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi a wealthy, cosmopolitan state on the nineteenth-century world stage was not its leaders, but rather its workers, how might this story influence current-day anticolonial strategies against U.S. empire? If labor, not land—people, not plantations—are central to Hawaiian history, how might working people, including diasporic off-Island Hawaiians, take center stage again in the Hawaiian lāhui?18 And what about women? Thousands of Hawaiian male migrant workers were supported at home by mothers, wives, sisters, cousins, and daughters. 4

•

I n t roduc t ion

Furthermore, hundreds of women worked on ships and abroad as migrant laborers. Some were prostitutes, some were domestic servants, others worked side-by-side with men doing the same labor yet not always receiving the same wages.19 Moreover, many historians have noted the incredible stories of female leaders in nineteenth-century Hawaiʻi who ruled as queens and princesses, prime ministers and regents. Titles shifted over time, but women always took a leadership role in the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi. European and Euro-American observers often wrote about Hawaiʻi as a nation of women.20 Yet sometimes this discourse was problematic. When foreigners wrote of Hawaiʻi as a seductive land luring colonists in to “have” her, they feminized the nation and the people; colonialism thus became an exercise of exerting one’s white heteronormative masculinity and patriarchy over a nation seen as submissive, feminine, and in need of protection. Attendant with this discourse, as Adria Imada has shown, was the imperial parading of Hawaiian women as representatives of the docile and welcoming (with aloha, of course) colonial subject body. Native scholars Ty P. Kāwika Tengan and Isaiah Helekunihi Walker have also shown how this discourse worked to erase Hawaiian men from narratives about Hawaiʻi. They were seen as superfluous, even dangerous, to the colonial project of making Hawaiʻi into a paradise (as defined by the colonizers). To this day, many Hawaiian working-class men feel sidelined from the dominant colonialist narratives of their nation and their history.21 In this book, Hawaiian men take center stage alongside a rigorous gender analysis that explores how Western discourse emasculated men as “kanakas,” and how Hawaiian men fought back against this talk through their courageous stories of work, migration, and sacrifice upon the ocean and across the world.

a hawaiian pacific world Hawaiian labor made the Pacific into a “world.” They did this by weaving a web of interconnections across the vast ocean—connections that had never before existed. Over the past decade, historians have debated the concept of a Pacific World. Is, or was, the entire ocean ever a coherent, integrated space? Did people in the nineteenth century see themselves as living and laboring in such a world? What forces make for such a world—the movement of labor, capital, and material, or the transmission and sharing of stories, songs, and culture? Some scholars posit that rising empires are the agents that historically I n t roduc t ion

•

5

connected disparate peoples and places together, calling the Pacific at times a Spanish Lake or referring to it, in the age of British and American imperialism, as an Anglophone Pacific World.22 Scholars of Asian migrations and diasporas have countered with the study of the transpacific—the worlds made, imagined, and populated by Asian workers, diasporic literatures, and counterhegemonic claims on imperial oceanic space.23 Both of these approaches, however, wholly dismiss Pacific Islander peoples and indigenous perspectives on the ocean. Some scholars have used environment and ecology to argue for a Pacific World, proposing variously that tectonic plates or tsunamis or the extraction of natural resources have geographically placed the ocean’s many peoples upon a singular stage.24 Economic arguments paint the Pacific World as a “sector” of the global economy, or as a “primal site” of globalization. In this vein, transoceanic maritime trade with China made the Pacific into a world.25 But then there are sectors within the sector; scholars have written of the Eastern Pacific and the Northern Pacific as unique arenas of economic and cultural activity.26 Indigenous scholars, on the other hand, have used Native languages and literatures to propose uniquely non-Western ways of conceptualizing the ocean. Historian Damon Salesa has mapped the “native seas” of pelagic fishing and maritime networks, while Hawaiian scholar B. Pualani Lincoln Maielua has celebrated the “situated knowledge” of a canoe’s-eye view of the world.27 The term Hawaiian Pacific World, as used in this book, is an attempt to build upon the aforementioned approaches while also making three important new contributions: first, this book argues that labor was the glue that held the Pacific Ocean together. Workers, in both body and mind—real people moving through ocean space and thinking about the world beyond Hawaiʻi— were essential agents of transoceanic integration. The Pacific became a “world” to Hawaiians through Native workers’ migrations, their labors abroad, and the stories and songs that they shared back home about their experiences. To argue otherwise—that Western explorers, the movement of ships, climatic or ecological pressures, the spread of disease, or other factors brought the world to Hawaiʻi—is to deny the agency of the thousands of Native men who traveled to distant corners of the ocean and the surrounding continents and carried aspects of the world beyond Hawaiʻi back home with them in their words, in the things they made, and in their altered bodies. Second, the term Hawaiian Pacific World denotes an explicitly national conceptualization of oceanic space, time, and belonging. Pacific World historians have shied away from nationalism. Acknowledging that important 6

•

I n t roduc t ion

events occur both below and above the level of the nation-state, and worrying, rightly so, of any interpretation that “elides native histories and reifies imperial agendas,” scholars have instead called for transnational or “translocal” approaches to the study of the ocean.28 But such approaches may effectively deny the national claims of indigenous peoples who have long understood their engagement with the world as a crucial aspect of their nation’s story. Furthermore, transnational approaches may give the impression that the ocean is, or was, a neutral space or empty stage upon which diverse peoples have historically come into contact. But, as David Chang has argued, Hawaiians, for example, have long understood the Pacific Ocean as a known realm. They peopled the ocean with their bodies as indigenous explorers, claiming the ocean as a space of Hawaiian storytelling integral to larger narratives of national identity and belonging.29 To say that there was a Hawaiian Pacific World, therefore, is to contend that Hawaiian national history goes beyond the borders of the archipelago, including the supranational spaces lived in, embodied, and transformed by migrant workers and diasporic Islanders. Th is book therefore presents a national history of Hawaiian engagements with global capitalism. The setting? A large swath of the Pacific Ocean and the surrounding continents, what I call the Hawaiian Pacific World. Finally, this conceptualization is grounded in both theories of historical materialism as well as the study of culture. To argue that only material linkages, economic and ecological, made the Pacific a world would deny the importance of Hawaiian workers’ own words, through letters home as well as through stories and songs, in making the world beyond Hawaiʻi legible to other Hawaiians. To argue, oppositely, that only intellectual and cultural understandings of oceanic space and time prove the existence of a larger world is to deny the monumental impact of global capitalism on Hawaiian minds, bodies, and movements. Trade networks, commodity chains, labor migrations, and capital flows, in addition to ocean currents, island ecologies, mineral deposits, and animal habitats all have materially shaped the geography of the world that Hawaiian workers came to know as theirs: a world they lived and labored in and brought home to Hawaiʻi. Specific contours of this Hawaiian Pacific World are explored in the chapters that follow. Hawaiian workers moved their bodies north, south, east, and west. Whale workers brought Hawaiian words with them to Alaska and Russia, then returned to Hawaiʻi with songs about ice and snow as well as a penchant for whale blubber and strong drink. Gold miners in California I n t roduc t ion

•

7

subscribed to Hawaiian-language newspapers, writing letters to editors, then finally receiving their words in print weeks or months later as these newspapers arrived in the mountains of North America. Hawaiian sandalwood cutters came to see the exchange-value of their toil in the fine Chinese cloths and furniture items in a chief ’s home in Honolulu. Through labor, workers set a Pacific World in motion. They were also one of the most literate working classes in the world. They uniquely wrote about their experiences abroad, and read their comrades’ words and stories in Hawaiian-language newspapers that were printed in Honolulu and shipped out across the ocean, wherever ships sailed. As Hawaiian scholar Noenoe K. Silva has shown, this was a diaspora of newsprint as much as a diaspora of people. Th rough the circulation of stories and songs, in print as well as through oral cultures, Hawaiians came to see themselves as part of a transoceanic diaspora.30 Workers’ words are crucial to this transoceanic imagining of diasporic Hawaiian space. Indigenous newspapers and Hawaiian-language geography textbooks, as demonstrated by David Chang, mapped out the ocean as a bounded and known world. To some it was ʻĀinamoana, literally “ocean land.”31 Other people experienced their own Pacific Worlds. There was no one common sense of oceanic space or transoceanic integration shared by all Pacific peoples, indigenous or foreigner. Yet it is also possible to speak of the ocean as an increasingly integral part of the larger processes of globalization. The Hawaiian Pacific World was influenced by forces not just beyond Hawaiʻi, but beyond the Pacific. Capital flowed into Pacific industries from Boston, New York, and London. Specie from Latin America exchanged hands on Hawaiian shores. Consumers in China and the United States touched and tasted Hawaiian-made products. Scholars have traced the emergence of a “world economy” in the early modern era, prior to the period of Hawaiʻi’s integration into that economic system.32 By the nineteenth century, global capitalism had expanded to yet new frontiers, forcing open distant markets and recruiting workers among indigenous societies in Africa, North America, and in Oceania, including Hawaiʻi.33 Globalization did not, and will not, homogenize the world’s peoples into one culture. Rather, contacts and confluences among local and global forces create hybridity as well as “friction.”34 Hawaiians influence the world just as the world influences Hawaiian society. The history of how Native Hawaiians engaged in (and against) the global capitalist economy can tell us something about how globalization was experienced in local, national, and regional contexts, from the 8

•

I n t roduc t ion

shores of Honolulu outward to the far corners of what was then the Hawaiian Pacific World.

hawaiian capitalism Historians have long studied capitalism as a unique mode of production, the way that capital moves across space, transfigures peoples’ sense of time, and drives workers off the land and into new relations of production. Narratives of primitive accumulation, the globalization of labor flows and markets, and the dispossession and proletarianization of indigenous peoples are commonplace themes in nineteenth-century world history.35 As Hawaiians became “enmeshed in the capitalist net” of the global economy, to use Lilikalā Kameʻeleihiwa’s words, how did indigenous workers and consumers experience this brave new world? What were the unique features of Hawaiian capitalism?36 The dominant narrative of capitalism in Hawaiʻi focuses on changes in ka ʻāina (the land). Westerners colluded with Native leaders to push through land reforms in the 1840s that privatized millions of acres of the former commons, thereby dispossessing the makaʻāinana, the “people of the land.” This land was initially distributed among the aliʻi only, but soon much of it ended up in the hands of foreign owners. By turning the land into a commodity, Hawaiians lost their land and thereby lost their sovereignty.37 Or so the story goes. This narrative is not false, but there is more. While Hawaiʻi’s capitalist class sought to “free” the land—that is, to convert it into private property— they also simultaneously pushed for “free” trade and “free” labor. Western powers such as the United States and Great Britain employed gunboats to coerce states from the Qing Empire in China to the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi to open their ports to foreign commerce. So-called free trade led to the decline of indigenous industries, such as the production of kalo (taro) and kapa (cloth), while consumer debts fostered by increasing global commerce linked both individuals and states to the demands of foreign creditors.38 The dehumanization of the kanaka body, on the other hand, with Christian missionaries seeking to kill the Hawaiian but save the man, and employers’ belief in the nature of Hawaiian men as fit workers, also directed capitalism upon the human body.39 Workers experienced capitalism in intimate, personal ways, from the changing rhythms of working days and seasonal voyages to the changing meanings of once-familiar plants such as sandalwood and sugarcane.40 I n t roduc t ion

•

9

Indeed, capitalism conditioned workers’ environmental experiences in revolutionary ways.41 In addition to seeing native plants such as sandalwood and sugarcane transformed by their own hands into globally circulating commodities, Hawaiian laborers also engaged in new relationships with Pacific Ocean animals.42 Migrant workers’ hunt for wages actually turned them into real live hunters. Yet, animals were not just passive victims; they actively disrupted capitalist production through their movements and actions. In Pacific Ocean industries such as whaling and guano mining, human and animal labor collectively co-made the environment as a “workscape,” a fluid and dialectical interface of human and nonhuman inputs.43 Hawaiian migrants also caused environmental damage through their work. Their impact on local environments threatened floral and faunal habitats, disrupted other Native peoples’ lifeways, and even endangered their own ability to exit the wage economy and live off the land and the sea as a commons. Capitalism in Hawaiʻi disrupted and displaced Native Hawaiian relationships with ka ʻāina, but on the flip side it opened the door for common Hawaiians to develop cosmopolitan environmental experiences. Hawaiian migrants accumulated environmental knowledge and wisdom about the wider world that made them ambassadors for sharing stories and songs about the rare and raw natures that flourished beyond Hawaiʻi.44 But how Hawaiians became migrant wage workers in the first place was a messy process. Hawaiian proletarianization came about only in complex ways.45 As early as the 1810s, some Hawaiians worked for wages while others engaged in corvée labor. Some provided labor to aliʻi as hoʻokupu (tribute) while others labored independently for their own wealth. Some Hawaiians signed contracts aboard foreign ships and even worked overseas for foreign corporations. Hawaiian whale workers often labored for a combined share of total profits as well as a cash advance and sometimes wages for certain work but not for others. These complex entanglements of different modes of production and different relations of production, sometimes in the same places at the same times, marked Hawaiian capitalism as a bottom-up process of increasing engagements with the global economy rather than a top-down process imposed by elites or outsiders upon the people. There was no one moment when Hawaiian commoners became wage workers, and no one factor that propelled them into new forms of labor. In fact, many Hawaiian men sought out these opportunities. Capitalism was certainly embraced by some Hawaiians from the highest chief down to the lowliest worker, while it was also resisted in extraordinarily creative ways, on ships and on plantations all 10

•

I n t roduc t ion

across the Pacific World. Workers lived capitalism in their bodies, in their diets, in the things that they made and they consumed, and in the stories and songs that they told about a changing world.

on sources and ethics In the 1820s, Christian missionaries from New England brought the printed word to Hawaiʻi. In the 1830s they began to print the Islands’ first Englishand Hawaiian-language newspapers. Mission schools trained Hawaiians in ka palapala, reading and writing. Many Hawaiian workers learned to read and write, and their words not only helped to make a Pacific World in the nineteenth century, but they are also crucial tools for reconstructing Hawaiian history in the twenty-first century. The government-run newspaper Ka Hae Hawaii (1856–1861) was the first paper to regularly feature letters to the editor by Hawaiian authors. The independent newspaper Ka Nupepa Kuokoa (1861–1927) also regularly featured letters to the editor. These Hawaiian-language letters, written for and published in Honolulu newspapers, are one of the few means available for reconstructing the lives of Native Hawaiian migrant workers in the nineteenth century. From California to equatorial guano islands to wherever ships sailed, Hawaiians abroad frequently sent letters home to let family and friends know about their work experiences. These letters to the editor capture nineteenth-century migrant laborers telling their story in their own words, a rare documentary source for any time period or place, much less nearly two centuries ago at the onset of global capitalism’s influence in the Pacific World. These letters are complemented by archival sources that more often portray foreigners’ points of view. Sometimes records such as ships’ logs, work contracts, and government censuses do not record much beyond the existence of a certain number of “kanakas” at any given place at any time. All available sources—from workers’ writings to Hawaiian-language songs to ships’ logs to employers’ diaries and government reports—are used in this book to tell the story of the thousands of Native men who worked in the global capitalist economy. This book includes numerous Hawaiian-to-English translations. The act of translating from one language to another necessarily alters the meanings and messages embodied in words. Especially in the case of Hawaiian-language letters, essays, and songs, any translator is apt to completely miss the kaona I n t roduc t ion

•

11

(the hidden meaning) of the words and what they meant at the time, if not also what they might mean to ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language) speakers today. I am blessed to have had the guidance and encouragement of several gifted teachers in the Hawaiian language. They have patiently read and assisted with these translations. Still, English-language translations do not do justice to Hawaiʻi’s nineteenth-century writers, and I therefore include in the backnotes the original Hawaiian text to accompany each and every English translation. All errors and misrepresentations are entirely my own. I first traveled to Hawaiʻi in 2010 as a doctoral student looking for an interesting topic for my dissertation. I spent three days in Honolulu, visiting ʻIolani Palace and the Bishop Museum, and walking around Honolulu’s streets, my head pulsing with thoughts about sandalwood, China, the ocean, history. What was I looking for? I was determined to find an actual sandalwood tree. I spent four days on Kauaʻi looking for one. I was naïve, but more than that, I was reenacting colonialism. Here I was, a white person from the East Coast of the United States, bumbling my way through a foreign land looking for something that I could “sell” as a research project. I did not find an actual sandalwood tree, but I did find a story that propelled me to write this book. I have always wondered whether this is actually my story to tell, and if I am to tell it, how should it be told? Several years ago, a friend from Hawaiʻi told me about kuleana, a Hawaiian word that means both “privilege” and “responsibility” but cannot be reduced to either translation. She said that I needed to figure out what my kuleana was in regards to this project. She, as well as others, pointed me to the critical work of scholars such as Haunani-Kay Trask, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, and Julie Kaomea, who have all called for the decolonization of research and writing about Hawaiʻi and the Pacific.46 Here goes: I am not Hawaiian. I am not from Hawaiʻi. As a haole from the mainland, I see that my kuleana is the “privilege” to think and write about the Pacific from the outside looking in, to imagine creative and alternative interpretations to dominant discourses; my kuleana is to bring outside concerns, methodologies, and research questions to bear upon local and indigenous stories, to offer new ways of seeing and to give voice to concerns that may or may not resonate with current stakeholders in the archipelago. These are all privileges that come with great responsibilities. My kuleana is also my “responsibility” to understand that outsider historians for centuries have committed discursive violence against Hawaiians, labeling and interpreting their bodies and behaviors and falsely claiming to speak for them on the privileged academic 12

•

I n t roduc t ion

stage. My kuleana is to respect and pay witness to the historic and contemporary wrongs that have been (and are) committed against Hawaiian people, by academics and by others, including the maintenance and perpetuation of U.S. colonialism and the denial of legitimate Hawaiian claims to self-determination.

the story Chapter 1 begins with the story of the opening of a trans-Pacific triangular trade in the 1780s among the United States, China, and Hawaiʻi. Boki was an aliʻi (ruling chief) and kiaʻāina (governor) of Oʻahu who in the 1820s became obsessed with the sandalwood trade and the riches flowing into Hawaiʻi from the Qing Empire of China. The story of Boki’s predicament— how to ensure enough indigenous sandalwood supply to keep pace with Hawaiian leaders’ increasing consumption of foreign goods and their debts owed American merchants—is our entryway into understanding the emergence of the Pacific World as an integrated segment of the global capitalist economy, and one in which Hawaiian workers took center stage. In the 1840s, Western concepts of free labor and free trade revolutionized the transPacific economy with the imposition of treaty port restrictions on the Qing Empire following the Opium War (1839–1842) and the imposition of a freelabor ideology in Hawaiian land and legal reforms. By 1850, the Māhele— a process of land privatization and redistribution—had dispossessed the majority of Hawaiʻi’s indigenous people, leading many to seek work abroad or on foreign ships. Chapter 2 begins with the story of Make, a Native Hawaiian whale worker on an American ship in 1850. Make was just one of thousands of Hawaiian men who served on foreign whaling vessels in the nineteenth century. As the global whaling industry emerged in the period from 1820 to 1860, transoceanic economic and ecological factors conditioned Hawaiian workers’ experiences of both whales and the ocean. Movement and mobility are key to understanding the “whale worlds” inhabited by both Hawaiian workers and migratory whales. Hawaiian migrant workers were modern-day “whale riders.” Their experiences of ocean space and ocean time were influenced not just by global economic and ecological forces, including the geographical distance of the commodity chain from production to consumption, but by the nature of the ocean itself. Our story continues by following the movement I n t roduc t ion

•

13

of workers from Hawaiʻi to New England and beyond; the movement of whales from feeding grounds to breeding grounds; and the movement of whale parts from sites of production to sites of consumption in the United States. From 1848 to 1876, most Hawaiian whale workers toiled in the icy climes of the Arctic Ocean. Chapter 3 begins with the story of Kealoha, a Hawaiian whale worker who in the 1870s lived among the Inupiat of Alaska’s North Slope for over one year. Bodies—both cetacean and human—are a central category of analysis for understanding Hawaiian experiences of Arctic whaling. In the Arctic Ocean, Hawaiian men interacted not only with ice, wind, cold, and snow, but also became intimate with whale anatomy as well as their own bodies through work. European and Euro-American discourses on the kanaka body held that Hawaiian men were not fit for work in nontropical climates, but Kealoha and thousands of other Native men challenged these racialized ideas, proving their fitness and their manliness in the “cold seas” of the North. Another front of extractive industry in the 1850s and 1860s was guano mining. Kailiopio was one of approximately one thousand Native Hawaiian men who worked on remote equatorial Pacific Islands mining bird guano. Chapter 4 bridges themes in animal studies and the history of the body to explore the guano workscape. The guano island work environment was a hybrid world made and maintained interdependently by both human and avian actors. Millions of nesting seabirds, and their engagements in transoceanic work—connecting distant feeding grounds with local breeding grounds—constituted the nature of Hawaiian migrant workers’ experiences of this remote world. Meanwhile, the California Gold Rush opened up yet another front in the Hawaiian migrant experience. Eighteen-year-old Henry Nahoa wrote a letter home from California’s Sierra Nevada mountains in the 1850s to express his “aloha me ka waimaka [aloha with tears]” to family members in Hawaiʻi. Nahoa was not alone in his tears: at least one thousand Hawaiians migrated to California in the period before, during, and after the Gold Rush. Chapter 5 explores workers’ experiences in Alta California from the 1830s to the 1870s. During this time, men like Nahoa lived and labored under Spanish, Mexican, and U.S. rule. They worked in sea otter hunting, cattle hide skinning, gold mining, and urban and agricultural work, from the coasts to the sierras to cities and farms. Nineteenth-century California was an integral part of the Hawaiian Pacific World. 14

•

I n t roduc t ion

Native workers returning to Hawaiʻi in the second half of the nineteenth century found an almost unrecognizable economy and environment. Following the Māhele, Euro-American settlers had made Hawaiʻi their home and were intent on reorganizing labor and land to serve global capitalism. Chapter 6 examines the rise of the sugar plantation system in Hawaiʻi, and how Hawaiʻi’s sugar history—so often linked with histories of U.S. empire— was actually part of the same trans-Pacific story of oceanic industrialization through sandalwooding, whaling, guano mining, and gold mining. But the new migrant workers at this time were not Hawaiian kanakas, they were Chinese coolies. George Beckwith’s plantation at Haʻikū, Maui, is used as a case study for exploring the intersections and entanglements of Hawaiian and Chinese labor in this period. By 1880, Chinese and other non-Natives outnumbered Hawaiian workers in the sugar industry, and across the Pacific World the collapse of extractive industries such as whaling, guano mining, and gold mining left Hawaiʻi’s diasporic working class disjointed and disempowered. The end result was the dismemberment of the Hawaiian working class. In the Epilogue to this book, I consider how the story of the rise and fall of Hawaiʻi’s indigenous workers—and the diasporic, migratory nature of their experiences—revolutionizes what we think we know about the place of Hawaiʻi in the Pacific, and the place of the Pacific in the world. I also raise questions about what this story can contribute to twenty-first-century struggles over capitalism and colonialism in Hawaiʻi as well as across our globalizing world.

I n t roduc t ion

•

15

on e

Boki’s Predicament sandalwood and the china trade

french captain auguste duhaut-cilly could not believe his eyes. He was standing inside Boki’s home in Honolulu. From the outside it was humble, built “of wood and straw,” and “quite the same as all other houses in the town of Honolulu.” But “the interior,” he continued, “carpeted with mats like the others, differed only in its European furniture, standing in every corner and mixed with the native furniture. Nothing could have been more strange than to see a magnificent porcelain vase of French manufacture paired with a calabash, a work of nature,” or to see “two hanging mirrors with gilded frames meant to display beauties in their most elegant toilette but reflecting instead dark skin half covered with dirty tapa cloth.”1 In other words, Boki’s hale (house) was full of stuff—Native stuff, foreign stuff, simple stuff, exotic stuff. Just one year later, Boki was off on a fantastical adventure. In 1829 he outfitted two ships with nearly five hundred men and set sail from Honolulu to Eromanga, an island in the New Hebrides Islands (today’s Vanuatu), thousands of miles to the south. Boki’s intended goal was to harvest Eromangan sandalwood. Sandalwood paid for all the nice things that Boki had in his home. But Boki never made it back home. Some speculated that his ship was lost at sea; others that he had fled to live out his years in exile.2 Boki faced an awful predicament. He and the other aliʻi (chiefs)—the men and women of Hawaiʻi’s ruling class—had purchased so many goods from foreign ships and foreign merchants that they now owed tremendous debt to American creditors. The U.S. Navy had just recently sailed a gunship into Honolulu Harbor to support American private business, coercing the Hawaiian government to give up their wood. Everybody wanted sandalwood. Throughout the 1820s, Boki and the other aliʻi forced thousands of Hawaiian men to cut wood in 16

the mountains on every Hawaiian Island, and still they were not able to pay off their debts. Only by conquering and colonizing a foreign land, and by taking their wood, he reasoned, could the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi free itself from the grasp of American economic predation and imperialist maneuvering. This was Boki’s predicament. But more broadly, it is also the story of how capitalism came to Hawaiʻi. This narrative involves thousands of actors spanning the globe. It pairs northern Chinese fur consumers with southern Chinese merchants in the great emporium of Guangzhou (Canton). It matches European and Euro-American ships and their crews to the men and women of Hawaiʻi who willingly and often unwillingly fed appetites for exploitation. The narrative also involves thousands of Hawaiian workers, accustomed to an indigenous political economy based on agricultural and household production, who now sailed away on ships at sea, lived and worked abroad in foreign lands, and climbed into the mountains of their own land to cut down trees so that other people could buy mirrors and porcelain vases. This is the story of how Hawaiian land and labor became part of the Pacific World, linked to the global economy through ships, salt, sea otters, and sandalwood, and through the labor of thousands of Hawaiians who by the second half of the nineteenth century had become “free,” a landless proletariat set adrift upon the ocean to find work wherever they could.

ships, salt, and sea otters Some say that Captain Cook discovered Hawaiʻi in 1778. But it was also the other way around. Hawaiians discovered the world. By 1800, Hawaiians had met people and consumed goods from China, North America, Europe, and Latin America, and some had even traveled to these places to see it for themselves. After Hawaiians killed Cook in 1779, his crew continued onward, selling sea otter furs that they had harvested on the northwest coast of North America at the great emporium of Guangzhou (Canton), the main commercial entrepôt of the Qing Empire.3 Within one decade, multiple ships of European and American origin began visiting Hawaiʻi as part of a new transPacific fur-and-tea trade among China, the northwest coast of North America, Hawaiʻi, and points Atlantic.4 These ships called at Hawaiʻi in order to procure “refreshments”: fresh fruits, fresh water, and fresh bodies— women for sexual pleasure and men for manual labor. s a n da lwo od a n d t h e c h i n a t r a de

•

17

Foreigners visiting late eighteenth-century Hawaiʻi encountered a unique land, with a distinctive mode of production. Hawaiians structured relationships of land and labor according to indigenous economic values and longstanding religious and cultural traditions. In eighteenth-century Hawaiʻi there were, broadly speaking, two major socioeconomic classes. Relations of production were divided among makaʻāinana (commoners) and aliʻi (chiefs). The makaʻāinana lived on the common lands of ahupuaʻa, pie-cut-shaped districts, in which commoners had access to the resources of upland forests, lowland valleys (suitable for agriculture), and near-shore fisheries. Hawaiians’ bodily labor was not, however, directed solely toward subsistence, as commoners were also required to periodically give hoʻokupu (tribute) to aliʻi who, on their behalf, maintained proper relations with nā akua (the gods) who, in turn, ensured the fertility of the land. This circular process—what historian Lilikalā Kameʻeleihiwa has called mālama ʻāina (care for the land)—was dependent upon the pono conduct of all parties. Pono, a salient concept in Hawaiian political economy, is often translated as “just” or “proper,” but it also implies a state of balance that can be both ecological as well as bodily. It refers to things being the way they are supposed to be. In summary, the key peoples in Hawaiʻi’s indigenous economy were the two classes, makaʻāinana and aliʻi, and a key moral value was pono, the “right conduct” that governed relations of production between classes as well as relationships among ka ʻohana (the family), ka ʻāina (the land), and ke kino (the body).5 Commoners’ tribute most often took the form of corvée labor. Aliʻi periodically requisitioned labor for building fishponds or heiau (temples) or to serve as foot soldiers in intra-Hawaiian wars. In the nineteenth century, under the rule of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi (until government reforms in the 1840s), makaʻāinana were required to pay a labor tax that built upon this tradition of hoʻokupu. Penal labor was also a feature of early Kingdom rule. Hawaiian commoners were often forced—either as corvée or as convicts—to labor in state-owned industries such as sandalwood harvesting or at the royal salt works at Āliapaʻakai, Oʻahu.6 By the beginning of the nineteenth century, traditional labor practices and class relations were already changing. Two commodities irrevocably changed Hawaiʻi’s place within the global economy. One was found in abundance in Hawaiʻi: salt. The other was only available thousands of miles away: the fur of the sea otter (Enhydra lutris). In many ways, trade in sea otter pelts is what made the Pacific World go round in the late eighteenth century.7 The players in this grand dance were manifold. There was the Qing Empire. They 18

•

B ok i ’s Pr e dic a m e n t

were at the powerful, strategic epicenter of the fur-and-tea trade. The Qing had what everyone else in the world wanted: tea. In return, there were a few things that they would accept from foreign traders but many that they would not; sea otter furs were a rare desired item. Two other major players, Great Britain and the United States, were compulsively addicted to tea (and to sugar, too, altogether creating a veritable maelstrom of Atlantic and Pacific economic conjunctures: tea, sea otter furs, African slavery, Hawaiian labor— all part of a grand narrative of globalization in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries). To get Chinese tea, British and American merchants extracted ginseng from northeastern American forests, sea otter furs from northwestern American bays and coves, sandalwood from Pacific Islands, and so on.8 The Russian empire was also a player in this grand dance: they sold mammalian furs to the Qing as early as the seventeenth century. In the eighteenth century, the Russian empire expanded across the Pacific Ocean into uppermost North America. They extracted sea otter furs from the North Pacific, just as the British and Americans did in the Columbia River region. Russians, Brits, and Americans even variously (and tenuously) worked together at times to get sea otter furs to market.9 All of these world powers—China, Russia, Britain, the United States— were simultaneously dependent on Hawaiʻi. There were no sea otters in Hawaiian waters, but Hawaiʻi had provisions. To get sea otter furs across the great ocean, foreign traders needed a midway rest stop: they needed a place where they could acquire fresh fruits and vegetables, fresh water, and labor. The late eighteenth-century trans-Pacific fur-and-tea trade was intimately dependent on Hawaiian labor and Hawaiian resources. Some Hawaiian migrant workers traveled to the northwest coast of North America to assist with the sea otter hunt, while others simply sought ways to accumulate wealth via the provisioning of biological and mineral resources to passing ships. Toward the end of the eighteenth century, almost every European or Euro-American vessel crossing the ocean between the Americas and China alighted in Hawaiʻi. By one scholar’s reckoning, as many as forty-five ships visited Hawaiʻi in the years between 1786 and 1800.10 Hawaiian workers traveled abroad on some of these ships. For example, while stopped in the Islands in January 1808, John Suter of the ship Pearl reported recruiting six Native men to go with him to the northwest coast of North America to hunt sea otters: “I Ship’d one man, at the Islands, Six of the Natives. I arrived on the Coast the 18th of Feby.” John C. Jones, U.S. consul to the Hawaiian Kingdom, wrote from Honolulu in 1821 that “all s a n da lwo od a n d t h e c h i n a t r a de

•

19

vessels on the [northwest] coast now have got double crews,” referring to the equal recruitment of Hawaiians alongside Yankee seamen aboard sea otter hunting ships. “The Brig Frederick, Capt Stetson sailed from here yesterday, who came to these Islands from the Coast, for the purpose only of getting more men for himself & Capt Clark, he has taken away about twenty” Hawaiian men. These Hawaiian workers in the early decades of the nineteenth century were the first significant wave of labor to expand the reaches of the Hawaiian Pacific World.11 In Hawaiʻi, the indigenous political economy was also transformed as Hawaiians began to produce the Islands’ first export commodity. The significance of salt was directly related to the sea otter fur trade. Salt was absent—at least in easily extractable crystalized form—from the coasts inhabited by sea otters. Geography thus inconvenienced those who would seek to preserve sea otter skins and turn them into dollars and cents, but this haphazard geography was a boon for Hawaiians. Traders alighting in Hawaiʻi found tons of salt for the taking. In the coming decades, Hawaiian aliʻi ordered salt extracted and piled up at Kawaihae on Hawaiʻi Island and at Āliapaʻakai near Honolulu on Oʻahu.12 As a commodity, Hawaiian salt was alienated from the ʻāina and from the Hawaiian labor that extracted it. It was buyable, sellable, exchangeable. Its value was determined, in part, by the cost of its production but also by the ups and downs of Hawaiʻi’s unprecedented relationship to a global capitalist economy. In all these ways, the story of salt prefigures the story of sandalwood. Salt provided eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century Hawaiians with some sense of what it might feel like to link their labor and environment to the supplies and demands of a global marketplace. Indeed, demand for Hawaiian salt was dependent on the success of sea otter harvests along North American shores and on the consumption patterns of Chinese fur wearers in northern China. The triangular nature of this trade prefigured the triangular nature of sandalwood production, distribution, and consumption. Salt, also like sandalwood, was a source of economic power for the Hawaiian ruling class. By 1802, John Turnbull, visiting Hawaiʻi, noted that salt was becoming scarce and expensive. “The natives,” having recognized the advantages of this scarcity, “learned to affi x a proper value to the productions of their country.”13 Much of Hawaiʻi’s salt exports came from one site on Oʻahu, a place about four miles west of Honolulu Harbor that the haole called “Salt Lake” and Hawaiians called Āliapaʻakai (literally, “salt encrustation”). In 1824, EuroAmerican missionary Charles Stewart visited the site, describing “a lake or 20

•

B ok i ’s Pr e dic a m e n t

pond, in which large quantities of salt are continually forming.” The abundant salt crystals sparkling on the lake’s surface seemed like “a frozen pond” to this New Yorker’s eyes. Upon reaching Salt Lake, Stewart was able to reach down and pick up crystals from among the “twigs, grass, and pebbles, over which the water had flowed.” He mused of the minimal labor needed for resource extraction: “From this natural work alone, immense quantities of salt might be exported.”14 But by the 1820s, Hawaiians were not just extracting salt from Āliapaʻakai; they were producing it. “The natives manufacture large quantities from sea water by evaporation,” Stewart wrote. “There are in many places along the shore, a succession of artificial vats of clay for this purpose, into which the salt water is let at high tide, and converted into salt by the power of the sun.” To make so much salt required massive amounts of human labor. Stewart did not report on how many workers produced salt at Āliapaʻakai, but later sources from the 1830s through the mid-nineteenth century describe makaʻāinana labor in the thousands (as many as two thousand workers in one instance) working in and around the lake making crystals for export to passing ships. By 1840, according to Charles Pickering who visited the Islands with the U.S. Exploring Expedition, a scientific endeavor, “Salt is now exported to Chili, to Oregon, Kamtchatka & the Russian settlements, and some to California.” Salt connected Hawaiʻi with every corner of the Pacific World.15 Hawaiʻi’s emergence as a center of trans-Pacific trade in furs and salt was built upon more than just economic and ecological change. Political transformations also facilitated a change in the mode of production and helped to align Hawaiian labor and resources with the global economy. One man, Kamehameha (r. 1795–1819), almost singlehandedly did all of this: unifying the Hawaiian archipelago; promoting international trade; and encouraging increased economic production throughout the Islands. He was able to do this partly due to strong networks with foreign traders as well as through the acquisition of foreign goods, including European ships and arms. In other words, labor and nature from Hawaiʻi not only supported the growth of trans-Pacific capitalism in the late eighteenth century, but trans-Pacific capitalism supported the foundations of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi (c. 1810) and the creation of a modern nation-state in the middle of the Pacific Ocean in the early nineteenth century.16 Kamehameha made the trans-Pacific economy work for him. By generously giving fresh food and water to passing European and Euro-American s a n da lwo od a n d t h e c h i n a t r a de

•

21

ships, he was able to acquire a wealth of foreign goods, including military technologies. Kamehameha, more so than any other Hawaiian, mastered the art of this exchange. He captured European and American ships, and even more importantly, captured haole labor, making two foreigners—John Young of England and Isaac Davis of Wales—his “white aliʻi.” With foreign labor, ships, and guns, and an army of makaʻāinana foot soldiers, Kamehameha solidified monarchical rule over the islands. New relationships forged between Hawaiians and the global marketplace helped Kamehameha accumulate mana (divine power). As mōʻī (monarch) over a nascent empire, Kamehameha claimed the ʻāina and its productions and the labor upon it all as his own. He furthermore placed a royal kapu (“taboo”; restriction) on trade so that he alone held the reins over Hawaiian participation in the global economy. By uniting the islands, Kamehameha not only founded a monarchy, but also a monopoly.17 Of course, various actors on all sides challenged Kamehameha’s monopolization of land and labor. Foreign traders often sought to play island rulers off of one another, albeit largely unsuccessfully. Makaʻāinana also resisted. Sometimes they engaged in illegal trade with foreigners, such as when Isaac Iselin of New York visited Hawaiʻi in 1801 and purchased “116 prime hogs— at $2—piece” from “the King of the Isles” (Kamehameha), but also discreetly purchased pearls from unnamed “Sandwich Islanders” and other goods from American merchants living and working on the beach. Iselin’s exchanges document that not every Hawaiian (or foreigner) obeyed Kamehameha’s kapu on trade.18 Six years later, Iselin returned to Hawaiʻi. “I hope we shall anchor in 25 days from this, and find an ample supply of those excellent refreshments that have been so much extolled by many circumnavigators.” Twenty years after the beginning of the trans-Pacific fur-and-tea trade, by 1807, the world— including Iselin—knew of Hawaiʻi and its “excellent refreshments.” Sailors longed to stop there to dally with Native women. Captains sought to anchor there to refuel provisions of fresh food and water. Ships from Britain, France, the United States, and Russia sought salt there, and Hawaiian salt was put to use curing animal products across the great ocean, from Kamchatka to Alaska to California to Tahiti. Almost everything ended up in the market at Guangzhou. From 1786 to the 1810s, the Hawaiian Islands moved to the rhythms of this new trans-Pacific economy. In the words of historian Nicholas Thomas, Hawaiʻi had become the most important “staging post” in the entire Pacific Ocean. The archipelago’s abundant arable land and 22

•

B ok i ’s Pr e dic a m e n t

makaʻāinana labor, plus Kamehameha’s centralization of power, resulted in the production of enormous quantities of provisions for visiting ships. Hawaiʻi’s economy was growing. By the 1810s, foreigners had discovered yet another good besides sea otter furs that Chinese merchants in Guangzhou were willing to buy. As it happened, this thing grew abundantly in the forests of the Hawaiian Islands: sandalwood.19

of materiality and mana According to trans-Pacific trader James Hunnewell, Boki was a thief. On December 17, 1817, he noted in his journal that he “had some visits from the natives but no trade Bokee stole a peace [piece of] shirting.” Two days later: “recovered the peace of shirting stolen by Bokee.” Several months later, Hunnewell accused Boki of also supporting thievery among the commoners. “I find the indian that stole our Goods Is liberated and what is more taken into favour by the head chief of the Land (Bokee).” As we have seen, Boki loved stuff, and he tried to pay for it all with sandalwood. Captain Isaiah Lewis of the ship Arab noted such an arrangement in April 1820, writing to a subordinate that he had “Govn Pocka’s [Boki] written promise” that “5892 ½ Piculs” of sandalwood will be “delivered, on or before the 1st day of November next ensuing to you as my agent & the same promise specefies that it shall be of merchantable quality.”20 The trade of sandalwood for clothing, sandalwood for furniture, and sandalwood as credit not only signaled Hawaiʻi’s emergence within global capitalism, but also pointed toward massive transformations in the ways that people thought about stuff. The materiality of sandalwood was highly mutable: it was a tree; it was labor; now it is incense; now it is debt. For many Hawaiians it was tied to the concept of mana (divine power). Objects had mana, and wearing and owning fine things—particularly foreign and exotic items—was an expression of one’s own mana. Within capitalism, however, things also had an exchange-value. One mana-rich object could, strangely, be equal to so many sticks of sandalwood, or equal to so many dollars. Hawaiian mana thus came into conflict with Western concepts of value. Transformations in materiality and mana are one of the early ways that Hawaiians experienced capitalism.21 Hawaiian sandalwood—seven species in all—thrives in a variety of habitats. It grows in differing soil compositions, varying quantities of rainfall, and s a n da lwo od a n d t h e c h i n a t r a de

•

23

at elevations ranging from valley floors to mountainsides. Generally, sandalwood thrives throughout the middle-elevation regions of the Hawaiian Islands and up to a maximum elevation of 2,500 feet above sea level. One of the reasons for the tree’s success in so many habitats is its method of nutrition. As the tree grows it develops what are called haustoria, parasitic siphons that penetrate the roots of other neighboring plants. These haustoria suck out water and nutrients from other plants to feed the sandalwood. When a sandalwood tree reaches fifteen years old, on average, its inner core begins a transformation into what is called heartwood. Following this stage, the sandalwood produces approximately one kilogram of heartwood annually. On average, a tree is ripe with fragrant heartwood by its thirtieth year, but this moment is only marked by those humans who would use it for oil. Untouched, a sandalwood tree will continue to grow as high as eighty feet tall or for one hundred years.22 Before the nineteenth century, Hawaiians utilized sandalwood in a variety of ways. They applied ʻiliahi (sandalwood) powder to treat dandruff and eradicate head lice, and they mixed it with liquids to treat genital diseases. Most importantly, they used it as a perfume. Sandalwood’s fragrance was well known to early Hawaiians and they acknowledged this characteristic by sometimes referring to the wood as lāʻau ʻala, or “fragrant wood.” Used as a perfume, the heartwood of the sandalwood tree was ground into powder or into chips that were applied to kapa cloth. The finest kapa were perfumed by hammering the sandalwood powder or chips into cloth, releasing fragrant oil onto the kapa, or by marinating sandalwood chips in vegetable oil and then applying this aromatic spread to the material. The application of sandalwood oil also served to waterproof the fabric.23 Samuel Manaiakalani Kamakau, perhaps the most famous Hawaiian historian of the nineteenth century, proudly proclaimed of precontact Hawaiians that “my people were fond of honors, fond of fine things, fond of things to be proud of, fond of bedecking themselves, fond of fragrant things, of kapa that were perfumed.”24 But kapa was only one of many items that were perfumed, and sandalwood was only one source of ʻala, or fragrance, in Hawaiian material culture. Other sources include the fruit of the mokihana plant; maile leaves; puaniu (coconut flowers); ʻolapa bark; the flowers and sap of kamani; the leaves of lauaʻe (a fern); ʻawapuhi (wild ginger) root; the leaves and root of kūpaoa (a type of tree, but the Hawaiian word kūpaoa can also refer to any “strong permeating fragrance”). Many of these plants, especially those with fragrant flowers, are still used in making lei (flower necklaces). Fragrances, even today, hold great significance in Hawaiian culture. 24

•

B ok i ’s Pr e dic a m e n t

Sandalwood has an equally long history in China. The use of incense in China dates back as early as the Zhou Dynasty (1045–256 BCE), while the consumption of sandalwood incense probably originated with the arrival of Indian Buddhism during the first centuries of the Common Era.25 The earliest Chinese sandalwood consumers most likely adopted Indian Buddhist ideas about sandalwood as much as they adopted the foreign wood itself. These ideas may have included the belief that sandalwood smoke had the ability to create a favorable environment, known as a xiangshi, or “incense room,” for the earthly manifestation of the Buddha. Although this particular belief has roots in Indian Buddhism, it was also practiced in China.26 Foreign traveler W. W. Wood, exploring the cities and landscapes of China’s Pearl River Delta in the late 1820s, noticed all around him a sustained interest in incense consumption among the Chinese, despite the modernizations and commercializations of Chinese life and consumer habits during the Qing dynasty. Wood was astounded by the size of the “idolatry” industry that supported incense consumption throughout the Guangzhou area. By rough estimate, Wood suggested that the Pearl River Delta region alone employed 2,000 “makers of gilt paper”; 400 “shrinemakers”; about 10,000 “makers of candles”; and at least 10,000 “makers of jos-stick,” or incense.27 “Part of the market purchases of a Chinese,” Wood remarked of Guangzhou consumers, are “the odiriferous matches, oil, and small sacrificing candles made of wax filled with tallow, and having a wooden wick.” These “odiriferous matches” that Wood noticed in the markets of Guangzhou were incense. Many were likely made of powdered Hawaiian tanxiang (Chinese for “sandalwood”). When Wood documented religious rituals practiced by Chinese consumers, he specifically noted the role of incense in the material cultures of both elites and commoners. In the homes of the wealthiest Chinese, he noted “an ancient copper censer, for burning sandal wood, or odiriferous matches . . . constitute the most frequent decoration of the oratories or small temples, which are placed at the entrances of houses, and in the chambers.” Not just confined to the wealthy few, however, “the superstitions with regard to evil spirits, are very prevalent among all classes,” Wood noted, “and no house or boat is seen at night undefended by small odoriferous matches.” As Wood walked the city streets he found that “every evening are bunches of jos-stick stuck about the doorways [of homes], and the light carefully attended to which burns in the small temple or oratory with which every Chinese house is provided, under the idea that these ceremonies will prevent the ingress of evil spirits.”28 s a n da lwo od a n d t h e c h i n a t r a de

•

25

Wood’s comments point to yet further meanings embodied in the fragrance of incense. While the use of sandalwood, in particular, may have been confined to wealthier classes of Chinese consumers, both elites and even common sampan residents (boat-dwelling people) appear to have used incense in similar ways: to ward off “evil genii” and “evil spirits.” Elites and commoners alike carefully placed incense sticks at doorways and at entrances, barring the entrance of angry or inauspicious supernatural beings into their places of home and rest. Incense sticks were also lit at even the smallest altars, within the home or in the temple or on the sampan. Chinese incense consumption appears to have been unusually egalitarian and incredibly profuse. Whether understood as a medium for recapturing the Buddha or as protection against evil spirits or simply as part of ancestor worship, the act of burning incense had profound meanings in Chinese material culture. This material culture was the driving force behind Chinese incense consumption, and hence sandalwood consumption. Furthermore, Chinese consumers and the religious beliefs and practices that informed their consumption were correspondingly an indirect force behind transformations in the Hawaiian countryside thousands of miles away. The meeting place of Hawaiian sandalwood and Chinese consumers, where Hawaiian ʻiliahi became Chinese tanxiang—where sandalwood shifted hands and meanings—was China’s Pearl River Delta. Here, the landscape itself seemingly memorializes a long history of buying, selling, producing, and consuming aromatics. Traveling north up the delta, sailors saw Xiangshan, or the “fragrant hills,” to their west. To their east they saw an island called Xianggang, or the “fragrant port” (Hong Kong). Deep in the hull of their own ships emanated the odor of tanxiang, “fragrant sandalwood.” These words all utilize the Chinese character xiang, which has two meanings, “fragrance” and “incense.” This dual meaning appropriately signifies the long-term historical interrelationship between consumer demands (for fragrance) and the actual consumption of material resources to satisfy those demands (such as incense) in Chinese history. The Hawaiian wood that regularly arrived in the Pearl River Delta in the early nineteenth century was part of this history of converting exotic aromatic materials into commodities essential to the maintenance of Chinese material culture.29 Chinese incense consumers frequently chose from among a global selection of imported aromatic woods.30 During the early nineteenth century, British East India Company ships and private British vessels brought to Guangzhou sandalwoods from India, Bengal, and elsewhere in South Asia 26

•

B ok i ’s Pr e dic a m e n t

40,000

American ships Private British ships British East India Company

35,000

Total weight in piculs

30,000 25,000 20,000 15,000 10,000 5,000

5 –1 18 7 18 –1 18 9 20 –2 18 1 22 –2 18 3 24 –2 18 5 26 –2 18 7 28 – 18 29 30 – 18 31 32 –3 3 16

18

3

–1 14

18

1

–1 12

18

9

–1 10

18

7

–0 08

18

–0

–0 04

18

18

06

5

0

figure 1. Sandalwood Imports at Guangzhou, 1804–1834. Source: Charles Gutzlaff, A Sketch of Chinese History, Ancient and Modern; comprising a Retrospect of the Foreign Intercourse and Trade with China (New York: John P. Haven, 1834), vol. II, appendices II–IV, VI–XI. Compiled by the author.

and Southeast Asia, while American ships transported sandalwood from Fiji, the Marquesas Islands, and Hawaiʻi. By the early 1820s, however, Hawaiian sandalwood was practically the only wood carried by American ships, and at the same time, American trading companies were the leading exporters of sandalwood to China. Chinese incense consumers were therefore increasingly purchasing Hawaiian wood in the 1820s. This all explains Hawaiian sandalwood’s materiality, but what of its mana—its power? If the makaʻāinana experienced sandalwood in the forests, and Chinese consumers experienced it through the consumption of incense, then Hawaiian aliʻi experienced it through its mutability—its ability to become something else: a chair, a vase, a ship. Workers and consumers experienced sandalwood as a material thing, but aliʻi primarily experienced the wood’s exchange-value, its exchangeability for other goods in the global marketplace. When Samuel Hill went to the Pacific aboard the Ophelia in 1815, his employers told him to collect whale teeth along the way, for aliʻi loved s a n da lwo od a n d t h e c h i n a t r a de

•

27