A Companion to Pietro Aretino (The Renaissance Society of America, 18) 9789004348059, 9789004465190, 9004348050

An interdisciplinary exploration of one of the most prolific and controversial figures of early modern Europe. This volu

325 65 6MB

English Pages 624 [623] Year 2021

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Marco Faini

- Universities of Venice and TorontoPaola Ugolini

- University at Buffalo

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

A Companion to Pietro Aretino

The Renaissance Society of America texts and studies series

Editor-in-Chief David Marsh (Rutgers University)

Editorial Board Anne Coldiron (Florida State University) Paul Grendler, Emeritus (University of Toronto) James Hankins (Harvard University) Gerhild Scholz-Williams (Washington University in St. Louis) Lía Schwartz Lerner (cuny Graduate Center)

Editorial Assistant Colin Macdonald (Renaissance Society of America)

volume 18

The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/rsa

A Companion to Pietro Aretino Edited by

Marco Faini Paola Ugolini

leiden | boston

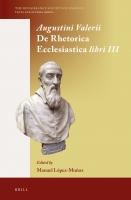

Cover illustration: Portrait of Pietro Aretino, 1545. Artist: Tiziano Vecellio (1488/90–1576). Palazzo Pitti, Galleria Palatina, Room of Venus, inventory number 1912 n. 54. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Faini, Marco, editor. | Ugolini, Paola, 1974- editor. Title: A companion to Pietro Aretino / edited by Marco Faini, Paola Ugolini. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2021] | Series: Renaissance Society of America texts and studies series 2212-3091 ; volume 18 | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Identifiers: lccn 2021018976 (print) | lccn 2021018977 (ebook) | isbn 9789004348059 (hardback) | isbn 9789004465190 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Aretino, Pietro, 1492-1556–Criticism and interpretation. | lcgft: Literary criticism | Essays. Classification: lcc pq4564 .c66 2021 (print) | lcc pq4564 (ebook) | ddc 858/.309–dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021018976 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021018977

Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill‑typeface. issn 2212-3091 isbn 978-90-04-34805-9 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-46519-0 (e-book) Copyright 2021 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill nv incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Hotei, Brill Schöningh, Brill Fink, Brill mentis, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Böhlau Verlag and V&R Unipress. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Requests for re-use and/or translations must be addressed to Koninklijke Brill nv via brill.com or copyright.com. This book is printed on acid-free paper and produced in a sustainable manner.

For our parents: Adriana Sandrini, Maria Concetta Montermini, Franco Ugolini

∵

Contents Acknowledgments xi List of Figures xii Timeline: Pietro Aretino in Context Bibliographical Abbreviations xx Notes on Contributors xxii

xv

Introduction 1 Marco Faini and Paola Ugolini

part 1 Selfhood and the Public Sphere 1

Inventing the Celebrity Author Raymond B. Waddington

2

Aretino at Home 44 Harald Hendrix

19

part 2 Criticism and Satire 3

“Pietro Aretino, the Ferocious Prophet,” and Pasquino Chiara Lastraioli

73

4

Aretino and the Court Paola Ugolini

5

Two or Three Things I Know about Her: Aretino’s Ragionamenti Ian Frederick Moulton

91

113

viii

contents

part 3 Arts 6

Aretino and the Painters of Venice 137 Philip Cottrell

7

Veritas Odium Parit: Uses and Misuses of Music in Aretino’s Sei giornate 170 Cathy Ann Elias

part 4 Literary Genres 8

Pietro Aretino, Poet 189 Angelo Romano

9

“A Knot of Barely Sketched Figures:” Pietro Aretino’s Chivalric Poems 202 Maria Cristina Cabani

10

Aretino’s Theater 237 Deanna Shemek and Jane Tylus

11

Pietro Aretino: Attributed Works Giuseppe Crimi

271

part 5 Religion 12

Aretino’s “Simple” Religious Prose: Literary Features, Doctrinal and Moral Contents, Evolution 303 Élise Boillet

13

The Three Hagiographies: Writing about Saints in the Age of the Council 329 Paolo Marini

ix

contents

14

The Figurative Rhetoric of Pietro Aretino’s Religious Works Augusto Gentili

370

15

The Imitation of Pietro Aretino’s Vita di Maria Vergine and Umanità di Cristo in Italy after the Council of Trent 409 Eleonora Carinci

part 6 Networks 16

Aretino as a Writer of Letters Paul Larivaille

435

17

Pietro Aretino and Publication Brian Richardson

18

Aretino as a Target for Criticism, and His Enemies from Berni to Muzio 497 Paolo Procaccioli

464

part 7 Afterlife 19

Aretino’s Troubled Afterlife Harald Hendrix Bibliography 545 Index of Names 586

529

Acknowledgments The authors wish to thank Ingrid De Smet, Craig Kallendorf, Andrew Serio, Maureen Jameson, Colleen Culleton, the two anonymous reviewers, and, at Brill, Eleonora Dragoni, Arjan van Dijk, and Ivo Romein.

List of Figures 1.1 1.2

1.3

1.4

1.5

2.1 2.2

2.3 2.4 2.5

2.6 6.1 6.2 6.3

The woodcut author portrait of Aretino designed by Titian for his first book of letters, January, 1538. Image courtesy of The British Library Board 27 The medal of Aretino with a reverse of a satyr kneeling before the seated figure of Truth. Artist unknown, cast bronze, 59mm., ca. 1536. Private collection 33 Medal of Aretino with reverse of a phallic satyr head. Inscription “All in all and all in every part.” Artist unknown, cast copper, 42 mm., ca. after 1543. Private collection 34 Francesco Salviati, woodcut author portrait of Pietro Aretino, La Vita di Maria Vergine, Marcolini, Venice, 1539. This example is taken from the comedy La Talanta, Marcolini, March 1542. IC5. Ar345.542t. Houghton Library, Harvard University. 37 Alex Shagin’s commemorative medal of Aretino, 2006, struck bronze, 46mm. The reverse combines Marcolini’s pressmark, Truth, the Daughter of Time, with the modern technology Aretino would have used to confirm the truth of his celebrity. Photograph by Kiet-le 43 Ca’ Bolani, Canal Grande, Venice (photo by the author) 52 The lay-out of Aretino’s apartment in Ca’ Bolani, as reconstructed and reproduced in Juergen Schulz, “Houses of Titian, Aretino and Sansovino”, in Idem, Titian, His World and His Legacy, ed. David Rosand (New York, 1982), p. 85 55 Tintoretto, The Contest between Apollo and Marsyas, oil on canvas, 139.7×240cm, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT. Inv. 1950.438 60 Enea Vico, Portrait of Antonfrancesco Doni, 153×112mm, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Arts, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 53.600.849 62 The lay-out of Aretino’s apartment in Palazzo Dandolo, as reconstructed and reproduced in Juergen Schulz, “Houses of Titian, Aretino and Sansovino”, in Idem, Titian, His World and His Legacy, ed. David Rosand (New York, 1982), p. 88 69 Anselm Feuerbach, Der Tod des Pietro Aretino, oil on canvas, 267.5×176.5cm, 1854, Basel, Kunstmuseum Basel 70 Titian, Self-Portrait, c. 1562, Berlin, Staatliche Museen, oil on canvas, 96×75cm 142 Titian, Pietro Aretino, 1545, Florence, Galleria Palatina, Palazzo Pitti, oil on canvas 1.08×0.67cm 143 Gian Paolo Pace, Giovanni dalle Bande Nere, 1545–1546, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, oil on canvas 0.90×0.97cm 147

list of figures 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 6.10 7.1

7.2

14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 14.8 14.9 14.10 14.11 14.12 14.13

xiii

Tintoretto, The Miracle of the Slave, 1548, Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia, oil on canvas 415×541cm 150 Titian, Ecce Homo, 1543, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, oil on canvas 242×361cm 151 Tintoretto, Apollo and Marsyas, 1545, Hartford, Wadsworth Athenaeum, oil on canvas 139.7×240.3cm 153 Giovanni Britto, Titian, 1550, London, British Museum, woodcut 41.5×32.2cm 156 Andrea Schiavone, The Judgment of Midas, 1548–1550, The Royal Collection/ Her Majesty the Queen, oil on canvas 167.6×197.7cm 159 Bonifacio de’ Pitati, The Massacre of the Innocents, 1536, Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia, oil on canvas 199×180cm 162 Lorenzo Lotto, St Nicholas Altarpiece, 1527–1529, Venice, Santa Maria dei Carmini, oil on canvas 335×188cm 165 Philippe Verdelot, “Divini occhi sereni”, bars 1–4. Di Verdelot. Tutti li madrigali del primo, et del secondo libro a quattro voci (Venice: A. Gardane, 1556) 20 181 “Alma mia fiamma”, Text by Pietro Aretino and music by Tommaso Bargonio. Antonfrancesco Doni, Dialogo della musica, ed. G. Francesco Malipiero (Vienna-Londra-Milano, 1965), 78–82: 78–81 185 Titian, The Sacrifice of Isaac, Venice, Santa Maria della Salute, sacristy 374 Titian, The Sacrifice of Isaac, detail. Venice, Santa Maria della Salute, sacristy 377 Tintoretto, The Sacrifice of Isaac. Venice, Scuola Grande di San Rocco, sala superiore 378 Jacopo Bassano, The Adoration of the Shepherds. Hampton Court, Royal Collection 380 Jacopo Bassano, The Rest on the Flight into Egypt. Milan, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana 381 Jacopo Bassano, The Last Supper, detail. Rome, Borghese Gallery 382 Titian, The Crowning with Thorns. Paris, Musée du Louvre 383 Titian, The Crowning with Thorns, detail. Paris, Musée du Louvre 385 Head of Nero. München, Staatliche Antikensammlungen 385 Gillis Sadeler after Tiziano, Nero. Rome, Gabinetto Nazionale delle Stampe 386 Titian, Penitent Magdalene. Saint Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum 389 Titian, Penitent Magdalene. Naples, National Museum of Capodimonte 390 Workshop of Francesco Mezzarisa (after Francesco Salviati), Crucifixion with Mary Magdalene. London, British Museum 393

xiv 14.14 14.15 14.16 14.17

14.18 14.19 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4

19.5

19.6 19.7

list of figures Workshop of Francesco Mezzarisa (after Francesco Salviati), Crucifixion with Mary Magdalene, detail. London, British Museum 394 Tintoretto, The Probatic Pool, detail. Venice, Church of San Rocco 396 Tintoretto, The Probatic Pool, Venice, Scuola Grande di San Rocco, sala superiore 398 Lamento di quel tribulato di Strascino Campana Senese, sopra el male incognito (Venice, Niccolò Zoppino e Vincentio compagni: 1521), title page. Venice, Biblioteca Marciana 401 Tintoretto, Mary at the Jordan River meditating on the past, detail. Venice, Scuola Grande di San Rocco, sala inferiore 405 Tintoretto, Mary at the Jordan River meditating on the future, detail. Venice, Scuola Grande di San Rocco, sala inferiore 406 Pierre Aretin, Trois livres de l’humanité de Iesu Christ, [transl. Jean de Vauzelles] ([Lyon], 1539) 533 Quattro comedie del divino Pietro Aretino (London, 1588) 534 Nicolas Poussin, Massacre of the Innocents, oil on canvas, 146×171cm, ca. 1626, Musée Condé, Chantilly 536 [Francois-Felix Nogaret], L’Aretin françois, par un membre de l’Académie des dames, Larnaka [= Bruxelles?], [1792], title page, with the accompanying lines: “A tous les vits le con donne des loix, / Des voluptés c’est la source féconde. / Vits, couronnez le con, ce roi des rois, / Et que le foutre à chaque instant l’inonde.” Courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale Paris 539 The actor Léon Lemadre as Pietro Aretino in the play Pierre d’Arezzo by Dumanoir and Dennery (Paris, 1838). Courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale Paris 541 Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, L’Arétin et l’envoyé de Charles Quint, oil on canvas, 41,5×32,5cm, 1848, Musée des Beaux Arts, Lyon, inv. 2013.1.1 542 Anselm Feuerbach, Der Tod des Pietro Aretino, oil on canvas, 267.5×176.5cm, signed and dated 1854, Kunstmuseum Basel, deposit of the Gottfried Keller Foundation 1895, inv. 209 543

Timeline: Pietro Aretino in Context 1492

Pietro Aretino is born in Arezzo in the night between April 19 and April 20 to Margherita (Tita) Bonci (Del Boncio) and (probably) Luca di Domenico Gherardi. Some scholarly sources report his father’s name as Luca Del Tura. 1506–1507 Aretino moves to Perugia. 1512 January: he publishes his first work, the Opera nova, a collection of poems (Venice, Nicolò Zoppino). The title page hints at Aretino’s apprenticeship as painter: the author calls himself “Pietro pictore Aretino” (Pietro painter from Arezzo). 1516/17 After a sojourn in Siena, he moves to Rome, where he enjoys the patronage of Agostino Chigi and of Pope Leo x (Giovanni de’ Medici). He makes the acquaintance of writers and artists such as Giulio Romano, Sebastiano del Piombo, and Raffaello. 1517 October: start of the Protestant Reformation. Many among Aretino’s friends and acquaintances will (at least partially) sympathize with Reformed ideas. It is not unlikely that Aretino himself at some point subscribed to Reformed views. 1521 December 1: Pope Leo x dies. Aretino writes a number of pasquinades on the occasion of the conclave; his reputation as a satirical poet seems to be already well established. 1521–1522 He publishes the Lamento di uno cortigiano, a satiric capitolo on courtiers. 1522 January 9: election of Adrian vi (Adriaan Florensz, 1459–1523); the new papacy marks a dramatic change as Adrian is known for his austerity and does not tolerate the laxity of the papal curia. July: Aretino leaves Rome and travels around Central Italy (Arezzo, Firenze, Bologna). A printed pasquinade, the Lamento de m.o Pasquino per la partenza de la corte, fato con le cortigiane di Roma […] (post April 27, 1522) alludes to an aggression against Aretino. From July he is in Bologna. 1523 February: Federico Gonzaga, marquis of Mantua, invites Aretino to join him at court. March: he sends to Rome a new, long Pasquinade, the Confession of master Pasquino (Confessione di maestro Pasquino). The pope tries to have him arrested. Probably to avoid the arrest, in spring he joins the condottiero Giovanni dalle Bande Nere in Reggio Emilia: they become close friends. September 14: Adrian vi dies.

xvi

1524

1525

1526 1527

1530 1531

timeline: pietro aretino in context November 26: Clement vii (Giulio de’ Medici) is elected pope. Aretino, who hoped in vain to obtain benefits from him, will later attack him with a violent sonnet (Sett’anni traditori). He spends the spring and part of the summer with Giovanni dalle Bande Nere. October: he returns to Rome. November: he is appointed Knight of Rhodes. December: Aretino hopes to foster his role within the curia and as an arbiter of international politics by publishing a canzone in praise of the pope, Laude di Clemente vii. He also publishes an exhortation to peace directed to Charles v and Francis i: Esortazione de la pace tra l’imperadore e il re di Francia. Between December 1524 and January 1525 Aretino writes and publishes a canzone in praise of Gian Matteo Giberti (Canzone in laude del Datario). In January he is introduced to the king of France, Francis i. Most likely in the first months of the year Aretino composes the Sonetti sopra i xvi modi. He probably had them printed in 1537, although the only extant printed copy bears a later date. February 25: Charles v defeats the French army of Francis i at Pavia. Also in the first months of the year Aretino writes his first comedy, La Cortigiana (Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Florence, ms. Magliabechiano vii 84). July 28: Achille della Volta wounds Aretino in an ambush. It is said that the instigator was the powerful cardinal Giovanni Matteo Giberti; recent scholarship tends to dismiss this hypothesis. September: Pietro Bembo publishes the Prose della volgar lingua (Venice, Giovanni Tacuino). October 13: Aretino leaves Rome headed for Mantua; once again, he joins the camp of Giovanni dalle Bande Nere. November: Giovanni dalle Bande Nere dies; the following month Aretino establishes himself in Mantua. Aretino begins writing Marfisa, a chivalric poem dedicated to Federico Gonzaga. March: Aretino moves to Venice; his residence will be the palace of Domenico Bolani on the Canal Grande. May 6, Sack of Rome. Aretino writes one of his most ferocious pasquinades, the frottola titled Pas vobis, brigate; he also writes a long canzone titled Deh avess’io quella terribil tromba and a capitolo titled Italia afflitta. In Bologna Clement vii crowns Charles v king of Italy. Aretino breaks off connections with Federico Gonzaga. A young poet, Antonio Brocardo, attacks Pietro Bembo. Aretino writes a series of sonnets against him that allegedly drive him to commit suicide. Aretino will long boast about

timeline: pietro aretino in context

1533

1534

1535

1536

1537 1538

1539

xvii

this episode, although he will also write a series of sonnets on the death of the young poet. February: Aretino publishes the comedy Il Marescalco. Francis i presents Aretino with a heavy gold chain. Alvise Gritti, brother of Andrea (doge of Venice and protector of Aretino) invites him to join him in Constantinople. Aretino apparently gives serious thought to this possibility but eventually declines. April: he publishes the Ragionamento della Nanna e della Antonia, fatto in Roma sotto una ficaia. The title page shows it to be printed in Paris instead of Venice (where most likely Marcolini printed it). Along with the 1536 Dialogo this work is known as Le sei giornate. June: he publishes La Passione di Giesù con due canzoni, una alla Vergine, et l’altra al Christianissimo. The canzone to the Virgin Mary will be republished separately at some point prior to 1538 in a revised version under the title Canzona alla Vergine Madre. August: he publishes a revised version of the comedy Cortigiana. October 13: election of Paul iii (Alessandro Farnese). November: he publishes I sette salmi della penitenzia di David. May: Aretino publishes I tre libri della humanità di Christo, a revised and expanded version of the 1534 Passione. He publishes the first three cantos of his chivalric novel Marfisa, and the first two cantos of another ultimately unfinished chivalric romance D’Angelica due primi canti, also known as De le lagrime d’Angelica. Publication of Dialogo, nel quale la Nanna il primo giorno insegna a la Pippa sua figliuola a esser puttana. Aretino, who had long been a supporter of the French party, turns to the Imperial side (upon receiving a pension of two hundred ducati). January: Aretino publishes the Stanze in lode di Madonna Angela Sirena. The beautiful engraving on the title page is attributed to Titian. January: Francesco Marcolini prints the first book of Aretino’s Letters. It is a groundbreaking publication, the first collection of letters of a living author in the vernacular. Aretino publishes Il Genesi con la visione di Noè (also with Marcolini). Marcolini prints the Ragionamento nel quale […] figura quattro suoi amici, che favellano de le Corti del Mondo, e di quella del Cielo. He undergoes a trial for blasphemy and (possibly) sodomy; he is forced to leave Venice temporarily. January: publishes a capitolo to Charles v on the death of the Duke of Urbino Francesco Maria i Della Rovere: A lo imperadore ne la morte del duca di. October: La Vita di Maria vergine appears in print.

xviii

timeline: pietro aretino in context

1540

Publishes his four capitoli “Allo Albicante”, “Al Duca di Fiorenza”, “Al Prencipe di Salerno”, “Al Re di Francia”. He publishes his (ultimately unfinished) parodic chivalric novel Li dui primi canti di Orlandino. December: Vita di Catherina vergine. Niccolò Franco publishes his Sonetti contra Pietro Aretino con la Priapeia. March: publication of the comedies Lo Hipocrito and Talanta. July 21: Paul iii establishes the new Roman Inquisition. August: Francesco Marcolini prints the second book of the Letters. Publishes the Vita di san Tomaso signor d’Aquino. Dialogo […] nel quale si parla del giuoco con moralità piacevole (also known as Carte parlanti) appears in print. July: outside Peschiera, on the Lake Garda, the emperor Charles v invites Aretino (following the duke of Urbino Guidubaldo ii Della Rovere) to ride at his right: it is a great sign of distinction. October: Aretino publishes Il capitolo et il sonetto in laude de lo imperatore, et a sua maestà da lui proprio recitati. Aretino publishes the Strambotti a la villanesca along with a reprint of the Stanze in lode di madonna Angela Sirena. February: publication of the third book of the Letters. End of May: he publishes his last comedy, Il filosofo. The play was originally composed in 1544. October: he publishes his only tragedy, L’Horatia. April: he writes and possibly publishes a capitolo in praise of Guidubaldo ii Della Rovere, duke of Urbino, along with a sonnet in praise of his wife Vittoria Farnese. His daughter Austria is born. Probably publishes the parodic chivalric novel Astolfeida. February 7: election of Julius iii (Giovanni Maria Ciocchi del Monte). The new pope was born in a small town near Arezzo; Aretino hopes to be elected cardinal. The pope appoints him knight of St. Peter. The city of Arezzo appoints him Gonfaloniere. He publishes the fourth and fifth book of the Letters. April: he publishes an encomiastic capitolo in praise of the pope along with one in praise of Catherine of France: Ternali in gloria di Giulio terzo pontifice cristianissimamente magnanimo, et della maestà de la reina cristianissima. July: he collects in a volume a selection of letters addressed to him: Lettere scritte al signor Pietro Aretino. Gathers in a volume Genesi, Umanità, and Salmi (Venice, heirs of Aldo). He moves to the house of Leonardo Dandolo, on the Riva del Carbon.

1541 1542

1543

1544 1546

1547

1548 1550

1551

timeline: pietro aretino in context 1552

1553 1555 1556 1557

1559 1741

xix

May/October: Libro secondo delle lettere scritte al signor Pietro Aretino. He publishes with the heirs of Aldo Manuzio a volume containing La vita di Maria Vergine, di Caterina santa e di Tomaso Aquinate beato. He accompanies Guidubaldo Della Rovere on a trip to Rome, hoping in vain that the pope will appoint him cardinal. April 9: election of Marcellus ii (Marcello Cervini); the new pope dies on May 1. May 23: election of Paul iv (Gian Pietro Carafa). Aretino dies on October 21 in his home in Venice. Gabriele Giolito de’ Ferrari publishes the sixth and last book of Aretino’s Letters; it bears a dedication to the duke of Ferrara Ercole ii d’Este. It was probably prepared by Aretino around 1553–1554. Aretino’s opera omnia are put on the Index of Forbidden Books. The Brescian scholar Giammaria Mazzuchelli publishes the first “modern” biography of Aretino; a revised version appears in 1763.

Bibliographical Abbreviations Quotations from Aretino’s works are normally taken from the Edizione Nazionale delle Opere (Rome: Salerno Ed., 1992–) and given in abbreviated form, listed below. Poesie varie i Pietro Aretino, Poesie varie, t. i, ed. Giovanni Aquilecchia-Angelo Romano (Rome, 1992). Poemi cavallereschi Pietro Aretino, Poemi cavallereschi, ed. Danilo Romei (Rome, 1995). Lettere i Pietro Aretino, Lettere, t. i, ed. Paolo Procaccioli (Rome, 1997). Lettere ii Pietro Aretino, Lettere, t. ii, ed. Paolo Procaccioli (Rome, 1998). Lettere iii Pietro Aretino, Lettere, t. iii, ed. Paolo Procaccioli (Rome, 1999). Lettere iv Pietro Aretino, Lettere, t. iv, ed. Paolo Procaccioli (Rome, 2000). Lettere v Pietro Aretino, Lettere, t. v, ed. Paolo Procaccioli (Rome, 2001). Lettere vi Pietro Aretino, Lettere, t. vi, ed. Paolo Procaccioli (Rome, 2002). lsa i Lettere scritte a Pietro Aretino, ed. Paolo Procaccioli (Rome, 2003). lsa ii Lettere scritte a Pietro Aretino, ed. Paolo Procaccioli (Rome, 2004). Teatro i Pietro Aretino, Teatro, t. i: Cortigiana (1525 e 1534), ed. Paolo Trovato, Federico Della Corte (Rome, 2010).

bibliographical abbreviations

xxi

Teatro ii Pietro Aretino, Teatro, t. ii: Il Marescalco. Lo Ipocrito. Talanta, ed. Giovanna Rabitti, Carmine Boccia, Enrico Garavelli (Rome, 2010). Teatro iii Pietro Aretino, Teatro, t. iii: Il Filosofo. L’Orazia, ed. Alessio Decaria, Federico Della Corte (Rome, 2005). Opere religiose i Pietro Aretino, Opere religiose, t. i: Genesi. Umanità di Cristo. Sette Salmi. Passione di Gesù, ed. Élise Boillet (Rome, 2017). Opere religiose ii Pietro Aretino, Opere religiose, t. ii: Vita di Santa Maria Vergine. Vita di Santa Caterina. Vita di San Tommaso, ed. Paolo Marini (Rome, 2011). Operette politiche e satiriche i Pietro Aretino, Operette politiche e satiriche, t. i: Ragionamento de le corti. Dialogo del giuoco, ed. Giuseppe Crimi (Rome, 2013). Operette politiche e satiriche ii Pietro Aretino, Operette politiche e satiriche, t. ii, ed. Marco Faini (Rome, 2012).

Other Abbreviations Cinquecentenario Pietro Aretino nel cinquecentenario della nascita, atti del Convegno di Roma-ViterboArezzo 28 settembre–1 ottobre 1992, Toronto 23–24 ottobre 1992, Los Angeles 27–29 ottobre 1992 (Rome, 1995). dbi Dizionario biografico degli Italiani (Rome, 1960–).

Notes on Contributors Élise Boillet is a cnrs researcher at the Centre d’études supérieures de la Renaissance of the University of Tours (France). She is the author of a monograph on Aretino’s biblical works (L’Arétin et la Bible, Genève, 2007) and has provided the critical edition of these texts for the “Edizione Nazionale delle Opere”. She is also the author of several papers on Renaissance Italian writings on the Psalms. She has co-edited several collections of essays related to European and Italian biblical literature and culture, also providing an important bibliographical tool in this field (E. Ardissino, É. Boillet, Repertorio di letteratura biblica a stampa in italiano (ca 1462–1650), Turnhout [in press]). She has recently directed a research project on religious practices and the European urban space in the modern era (eudirem, https://eudirem.hypotheses.org/, 2016–2019). Maria Cristina Cabani is Professor of Italian literature in the Department of Philology, Literature, and Linguistics at the University of Pisa. She has participated in the organization of international conferences and exhibits. She has been part of the committee for the organization of the exhibit Orlando furioso 500 anni (Ferrara, Palazzo dei Diamanti, 2016). She has organized and edited the proceedings of the conferences Alessandro Tassoni, poeta erudito, diplomatico nell’Europa dell’età moderna (2016) and Luigi Pulci, la Firenze laurenziana e il Morgante (2018). She is a member of the Accademia di Scienze, Lettere e Arti of Modena. Her main research interests are chivalric literature, epic poetry, and mock-heroic poetry from the fourteenth to the seventeenth century. She has also published numerous studies on mock-heroic poetry. Her publications include Costanti ariostesche, Pisa, 1990, Fra omaggio e parodia. Petrarca e il petrarchismo nel Furioso, Pisa, 1990, Amici amanti. Coppie eroiche e sortite notturne nell’epica italiana, Napoli, 1996, La pianella di Scarpinello. Tassoni e la nascita dell’eroicomico, Lucca, 1999, L’occhio di Polifemo. Studi su Pulci, Tasso e Marino, Pisa, 2005, Eroi comici, Bari-Brescia, Pensa, 2010, Ariosto i volgari e i latini suoi, Lucca, 2016. Eleonora Carinci earned her Ph.D. from the University of Cambridge. Recent positions include a Society for Renaissance Studies Rubinstein fellowship and a postdoctoral fellowship at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice within the erc Starting Grant “Aristotle in the Italian Vernacular: Rethinking Renaissance and Early Modern Intellectual History”, led by Marco Sgarbi. Her publications include a articles

notes on contributors

xxiii

and chapters focusing on various authors including Vittoria Colonna, Chiara Matraini, Moderata Fonte, Lucrezia Marinella and Camilla Erculiani, as well as a modern edition of Camilla Erculiani’s Lettere di philosophia naturale (Agorà & Co 2016). She is the editor of the English translation of Erculiani’s work, forthcoming in “The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe” series (Iter-acmrs 2019). She is currently working on a book on Felice Rasponi (Classiques Garnier 2021). Philip Cottrell is a lecturer in art history at University College Dublin and has a particular interest in sixteenth-century Venetian painting. He has published several articles in The Burlington Magazine, Art Bulletin, Venezia Cinquecento and Artibus et Historiae as well as essays and entries in several international exhibition catalogues and book anthologies. Alongside Peter Humfrey, he is the co-author of a forthcoming monograph on Bonifacio de’ Pitati. He has also published on a variety of other topics, including the work of Leonardo da Vinci, Caravaggio, the funeral monument of John Donne, and art collecting in nineteenth-century Britain. He has just completed a database project with the National Portrait Gallery, London, involving the digitization of the sketchbooks of its founding director Sir George Scharf. Giuseppe Crimi is Associate Professor of Italian at the Università Roma Tre. His research interests revolve mainly around Dante, comic poetry, games and literature, popular print as well as Pietro Aretino and sixteenth-century culture. He has edited Pietro Aretino’s Ragionamento de le corti and Dialogo del giuoco for the Edizione nazionale delle opere di Pietro Aretino (Operette politiche e satiriche, vol. 1 [Rome, 2013]) is currently working on the edition of the works attributed to Pietro Aretino for the “Edizione nazionale”. He is co-director of the journal L’Ellisse. Studi storici di letteratura italiana. Cathy Ann Elias is a Professor in the School of Music at DePaul University, a Distinguished Professor in the Honors College, and a Fellow in the Department of Catholic Studies. Concurrently she is completing a M.A. in Divinity at Catholic Theological Union. Her research covers a wide range of topics. Articles include “Claudio Baglioni, the Apollo of musica leggera” in Musica pop e testi in Italia dal 1960 a oggi (2015), “Sercambi’s Novelliere and Croniche di Lucca as evidence for musical entertainment in the 14th-Century” in The Italian Novelle (2002), “Erasmus and the Lying Mirror: More Thoughts on Imitatio and Mid SixteenthCentury Chanson Masses” in The Journal of the Alamire Foundation (2016), and

xxiv

notes on contributors

“Liberation Theology: Affirmation and Homage in Three Brazilian Masses” in Christian Music in the Americas (2021). She is completing an edition of Antonio Buonavita, Il primo libro de madrigali a quattro voci (1587) and Il primo libro de madrigali a sei voci (1591) for the American Institute of Musicology. She is also working on editions, Salvatore Di Cataldo, Tutti i principii de’canti dell’Ariosto posti in musica (1559) and Madrigali di Pietro Havente Libro I (1556). Marco Faini is Marie Skłodowska Curie Fellow at the Universities of Venice and Toronto. He was Andrew W. Mellon at Villa I Tatti. The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, Research Associate at the Department of Italian, University of Cambridge, and Stipendiat at the Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel. His research interests revolve around unorthodox literature and its connections with religious dissent (Teofilo Folengo, Pietro Aretino, Anton Francesco Doni); sixteenth-century devotional literature; private devotion in early modern Italy. He is currently working on a book project on doubt in Italy in the first half of the sixteenth century, tentatively entitled Standing at the Crossroads. Cultures of Doubt in Early Modern Italy. Augusto Gentili was professor of Art History of the Veneto at the University La Sapienza, Rome (1983–1997) and of History of modern art at the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice (1997–2013). He works on fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Venetian painting with an interdisciplinary approach based on history and iconology in this context. He is currently working on documents, sources, and contexts related to Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese. He has a special interest in problems of theory, methodology, and history of artistic historiography. He has published monographs on Carpaccio, Lotto, and Titian and more than 200 articles and short monographs on painting from Venice and the Veneto from Mantegna to Veronese, and a collection of essays La bilancia dell’arcangelo. Vedere i dettagli nella pittura veneziana del Cinquecento (Rome 2009 and 2011) and a major monograph on Titian (Milan, 2012). He was the founder and served as director and editor of the journal Venezia Cinquecento until 2015 when after twenty-five years it ceased publication. Harald Hendrix is Professor and chair of Italian Studies at the University of Utrecht, and served as director of the Royal Netherlands Institute in Rome (2014–2019). With a combined background in Cultural History, Comparative Literature and Italian Studies, he has published widely on the European reception of Italian Renais-

notes on contributors

xxv

sance and Baroque culture, on the early-modern aesthetics of the non-beautiful as well as on the intersections of literary culture, memory and tourism. Recent book publications include Writers’ Houses and the Making of Memory (New York 2012), Dynamic Translations in the European Renaissance (Rome 2011), The Turn of the Soul. Representations of Religious Conversion in Early Modern Art and Literature (Leiden-Boston 2012), The History of Futurism: Precursors, Protagonists, Legacies (Lanham MD 2012), Cyprus and the Renaissance, 1450–1650 (Turnhout 2013), and The Idea of Beauty in Italian Literature and Language (Leiden-Boston 2019). Paul Larivaille has for thirty years taught Italian Literature at the University of Paris x Nanterre. He is a member of the scientific committee of the Edizione Nazionale delle Opere di Pietro Aretino and of the Edizione Nazionale delle Opere di Niccolò Machiavelli. His studies focus mainly on Italian civilization in the sixteenth century. He has published several essays and translations and a biography of Pietro Aretino (Rome 1997). His publications include: Pietro Aretino fra Rinascimento e Manierismo, Rome 1980; Poesia e ideologia: letture della «Gerusalemme liberata» (Naples 1987); La vie quotidienne en Italie au temps de Machiavel (Paris 1989, prize of the Académie française 1980); La Pensée politique de Machiavel. Les discours sur la première decade de Tite-Live (Nancy 1982); L’ Érotisme discret de l’Arioste et autres essais sure le «Roland furieux» (Lille 2010); Letture machiavelliane (Rome 2017); Roberto Ridolfi, Vie de Machiavel, traduction par. P.L. (Paris 2019). His editions include: L’Arioste, Satire / Les Satires, texte italien établi par Cesare Segre, édition bilingue, notes de Cesare Segre et P. L., traductions de P.L. (Paris, 2014); La Veniexiana / La Comédie vénitienne, texte établi par Emilio Lovarini, introd. trad. et notes de P. L. (Paris, 2017). Chiara Lastraioli is Professor of Italian Studies at the Centre d’Etudes Supérieures de la Renaissance and in the Faculty of Languages and Literatures at the University of Tours. Her teaching and research explore the relation of Italian and French Renaissance Literatures to theology, propaganda, book trade, and the history of scholarship. She has published numerous essays on Renaissance authors and printers, as well as a monographic volume on Pasquinate, grillate, pelate e altro Cinquecento librario minore. She is also the coordinator of the program Bibliothèques Virtuelles Humanistes, co-editor of the review Italique, of the book collections Savoir de Mantice and Travaux du Centre d’études supérieures de la Renaissance, and the principal investigator of the project editef on “Italian Books and Book Collections in Early Modern French Speaking Countries.”

xxvi

notes on contributors

Paolo Marini is Associate Professor of Philology of Italian Literature at Università della Tuscia. He has worked mainly on Renaissance literature. He has published critical editions of works by authors such as Ludovico Ariosto, Bernardo Bibbiena, Benvenuto Cellini, Ludovico Dolce, and Girolamo Ruscelli as well as essays on these writers. In 2010 he edited the collection of studies Saggi aretiniani by Alessandro Luzio (Manziana, Vecchiarelli). He has published Pietro Aretino’s Opere religiose (vol. 2: Vita di Maria Vergine / Vita di santa Caterina / Vita di san Tommaso, Roma, 2013) for the Edizione Nazionale delle Opere di Pietro Aretino. He is currently working on a critical edition of Dolce’s lyric poetry and of Bibbiena’s correspondence. Ian Frederick Moulton is President’s Professor of English and Cultural History in the College of Integrative Sciences and Arts at Arizona State University. He has published widely on the representation of gender and sexuality in early modern European literature. His most recent book is Love in Print in the Sixteenth Century: The Popularization of Romance (Palgrave, 2014). Paolo Procaccioli is Associate Professor of Italian at the Università della Tuscia. He has worked mainly on vernacular literature in the Renaissance, focusing in particular on the critical interpretations of Dante’s works, on parodic texts, on the novella tradition after Boccaccio, and on the “irregular” literature of the sixteenth century. He has worked on Cristoforo Landino, Pietro Aretino, Anton Francesco Doni, Ortensio Lando, Francesco Marcolini, Girolamo Ruscelli, Ludovico Dolce, and has published critical editions and commented editions of their works. In collaboration with the international group of scholars affiliated with the research group Cinquecento Plurale, he has organized numerous conferences and seminars on Renaissance culture. He has edited Aretino’s six books of Letters as well as the two volumes of Lettere scritte a Pietro Aretino for the Edizione Nazionale delle Opere di Pietro Aretino. Brian Richardson is Emeritus Professor of Italian Language at the University of Leeds and a Fellow of the British Academy. His research interests centre on the history of the Italian language and the history of the circulation of texts in manuscript, in print and orally in late medieval and Renaissance Italy. His publications include Print Culture in Renaissance Italy: The Editor and the Vernacular Text, 1470–1600 (1994), Printing, Writers and Readers in Renaissance Italy (1999), Manuscript

notes on contributors

xxvii

Culture in Renaissance Italy (2009), Women and the Circulation of Texts in Renaissance Italy (2020) and an edition of Giovan Francesco Fortunio’s Regole grammaticali della volgar lingua (2001). Angelo Romano received a fellowship from the cnr (National Center for Research) to study with Giovanni Aquilecchia in London, where he specialized in sixteenth-century Italian literature. Together with Aquilecchia he has published the first volume of Aretino’s Poesie varie for the Edizione Nazionale delle Opere di Pietro Aretino (Rome, 1991). His research interests cover the Cinquecento (Pasquinesque satire, Pietro Aretino, Ludovico Dolce) as well as the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Vincenzo Monti). His research presently deals with literature and the Reformation. He has devoted studies to Olimpia Morata and Celio Secondo Curione and has organized the edition and translation of Curione’s Pasquillorum tomi duo (with Damiano Nevoli) as well as of his Araneus (1540–1544). Deanna Shemek is Professor of Italian and European Studies at the University of California, Irvine. She is author of Ladies Errant: Wayward Women and Social Order in Early Modern Italy (1998) and of In Continuous Expectation: Isabella d'Este's Reign of letters (2021). She has published essays on Aretino, Ariosto, Boccaccio, and others. Her collaborative editing includes Phaethon’s Children: The Este Court and its Culture in Early Modern Ferrara (2005), Writing Relations: American Scholars in Italian Archives (2008), and Itinera chartarum: 150 anni dell’Archivio di Stato di Mantova (2019). She edited and co-translated Adriana Cavarero’s Stately Bodies: Literature, Philosophy, and the Question of Gender (1995). Her edition and translation of the Selected Letters of Isabella d’Este (2017) won the Society for the Study of Early Modern Women’s 2018 prize for translation. She co-directs idea: Isabella d’Este Archive, an online project for study of the Italian Renaissance: http://isabelladeste.web.unc.edu Jane Tylus is Andrew Downey Orrick Professor of Italian and Professor of Comparative Literature at Yale University, where she also has a teaching appointment in the Divinity School. Recent books include Siena, City of Secrets (2015), the coedited Cultures of Early Modern Translation (with Karen Newman, 2015), and The Poetics of Masculinity in Early Modern Italy and Spain (with Gerry Mulligan, 2011), a translation and edition of the complete poetry of Gaspara Stampa (2010), and Reclaiming Catherine of Siena: Literature, Literacy, and the Signs of Others (2009), which received the Howard Marraro Prize for Outstanding Work

xxviii

notes on contributors

in Italian Studies from the Modern Language Association. She has been General Editor for the journal I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance since 2013. Tylus is currently at work on a monograph, “Saying Good-bye in the Renaissance: Meditations on Leavetaking,” and a collection of essays on music and translation. She is an honorary member of the Accademia degli Intronati, Siena. Paola Ugolini is Associate Professor of Italian at the University at Buffalo (suny). She is the author of The Court and Its Critics. Anti-Court Sentiment in Early Modern Italy (University of Toronto Press, 2020) and the co-editor and co-translator (with Molly M. Martin) of Veronica Gambara: Complete Poems (University of Toronto Press, The Other Voice, 2014). She has also published articles on early modern satires, on Ludovico Ariosto, Matteo Bandello, and on Gaspara Stampa. Raymond B. Waddington is the author of five books, three on Aretino, eighty articles, and co-editor of three books. He has been awarded fellowships by the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Foundation for the Humanities. He was senior editor of The Sixteenth Century Journal for eighteen years. Waddington’s 2004 book Aretino’s Satyr received the Modern Language Associations’ Scaglione Prize for Italian Studies, and translated into Italian (2009). He is professor emeritus at the University of California, Davis.

Introduction Marco Faini and Paola Ugolini

1

Who Was Pietro Aretino?

In 1647, Girolamo Ghilini (1589–1668), a historian, canon, and a member of the famous Academy of the Unknown (Accademia degli Incogniti) of Venice, devoted to Pietro Aretino a short biographic profile in his Teatro d’huomini letterati (A theatre of learned men). Aretino’s biography immediately preceded that of Pietro Bembo (1470–1547), the ‘other Pietro,’ so as to signal their mutual relationship, despite the gaping cultural and social differences that existed between them. In the concluding section of his biography of Aretino, Ghilini recalled how Aretino, after his death in 1556, was buried in the now demolished church of San Luca. To his tomb a Latin epitaph was appended proclaiming how Aretino had badmouthed everyone except for God, for he had never known Him. In order to make clear to everybody who the buried man was, a vernacular version was also added to the monument: Qui giace l’Aretin amaro tosco Del sem’human, la cui lingua trafisse Et vivi, et morti; d’Iddio mal non disse Et si scusò co ’l dir: “Io no ’l conosco”. (Here lies Aretino, bitter poison / Of the human seed, whose tongue pierced / The living and the dead; he never badmouthed God / Of which he apologized saying: “I do not know Him”). As Ghilini comments, this epitaph “goes around even in the mouth of commoners”.1 This ironic epitaph hinted at Pietro Aretino’s status as an irreverent mouthpiece for anything that stood against morality, and also as an atheist and a libertine. The first line plays on a pun between tosco (poison) and Tosco (from Tuscany, since Arezzo, Aretino’s birthplace is in Tuscany). The epitaph became a proverb of sorts, and is also known in other versions—with the first line reading “poeta Tosco” (Tuscan poet) instead of “amaro tosco.” Francesco Domenico 1 Girolamo Ghilini, Teatro d’huomini letterati […] (Venice, Guerigli: 1647), 192. For a discussion of a slightly different version of this epitaph, see also Harald Hendrix’s essay “Aretino’s Troubled Afterlife.”

© koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2021 | doi:10.1163/9789004465190_002

2

faini and ugolini

Guerrazzi reports it in this form in a nineteenth-century text, where it is quoted as being the product of the sixteenth-century historian Paolo Giovio, and the result of a contest between him and Aretino.2 Intriguingly, despite the lack of sources attesting to its authenticity (Guerrazzi’s claim itself is not supported by sixteenth-century sources), the epitaph has struck the modern imagination, to the point of being believed as the original epitaph engraved on Aretino’s tomb, or even to have been dictated by Aretino himself. However, Ghilini did not indulge in the lurid details of Aretino’s biography, which appealed so much to many of his contemporaries—a heavy burden of often apocryphal episodes that has long prevented an unbiased approach to Aretino’s work. His short biographical profile is sober and balanced; he certainly remembers the prohibition of Aretino’s oeuvre by the Inquisition (in 1559) and that he was famous for his scurrilous writings. He also adds, however, that his “sacred and spiritual works” are “all replete with great beauty and doctrine, and show his marvelous intelligence, most apt to every literary enterprise.”3 The anecdotes concerning Aretino’s epigraph are representative of the reputation that this prolific and multi-talented author has enjoyed throughout the centuries, and of the challenges that an analysis of his life and works still presents. Called both divine and infamous, known as a court poet, a pimp, a chronicler, and a pornographer, Aretino has successfully outwitted attempts to integrate his life and works into a coherent narrative. In addition, Aretino was also the first known author to have made a living through his writing, thus prefiguring the modern notion of author. Born in 1492 to a humble cobbler, Pietro “from Arezzo” (hence Aretino) climbed the social ladder in unprecedented ways. Forty years of literary activity made him into a tireless innovator of literary genres and a point of reference for the Italian and European cultural scenes. The very year of his birth seems to represent a sort of sign. In the year 1492, the death of Lorenzo the Magnificent marked the beginning of the end of the so-called ‘freedom’ of Italy. In the opening page of his History of Italy, Francesco Guicciardini nostalgically described the long-lasting period of peace between Italian states that had fostered an unprecedented cultural and artistic development. This condition came to an abrupt end, as is well known, in 1494, when the French army led by Charles viii invaded Italy, thus marking the beginning of the ‘Italian wars’ that came to an end only in 1559. At the same time, the early 1490s saw the (often premature) deaths of some of the most notable Italian humanists:

2 Francesco Domenico Guerrazzi, Scritti (Florence, 1948), 188. 3 Ghilini, Teatro, 192.

introduction

3

Politian (1454–1494), Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494), Ermolao Barbaro (1454–1493), Giorgio Merula (1430–1494). The sudden disappearance of an entire generation of humanists caused in their contemporaries a sense of loss that is evident in numerous documents; at the same time, it exposed unforeseen spaces for emerging writers. The model of the “letterato cortigiano,” or the courtly writer, became quickly problematic for the generations of writers born in the 1470s and 1480s who all seem to show some degree of discomfort towards it. Pietro Bembo (1470–1547) was never the kind of humanist and civil servant that his father Bernardo (1433–1519) was. Ludovico Ariosto’s ambivalence towards the Ferrarese court is well known (Ariosto was born in 1474); and it is almost superfluous to recall the complicated relation between Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) and the Medici. While the court as a cultural model embodied in the several minor courts of Italy retained some of its attractions, it soon became apparent that other, more effective means were available to writers who wanted to make a living out of their talent. These means were connected with the booming print industry that determined a cultural shift. The increasing demand for books by an ever-widening audience caused the vernacular to take the place of Latin. Writing in a pleasant, accessible vernacular became key to editorial success, and a proper humanistic background was no longer a necessary pre-requisite for a literary career. Pietro Bembo, who had a traditional training in Latin and Greek chose to write mainly in the vernacular, eventually becoming the ‘legislator’ of the Italian language. Aretino, who was born less than a generation after Bembo, no longer felt the need for a humanistic education. On the contrary, he always boasted of his lack of classical studies as a sign of distinction: the extraordinary gifts received by Nature more than compensated for the lack of a bookish culture that he perceived more as an obstacle than an advantage. Aretino made his debut as a painter, as declared in the title page of his first printed work, the Opera nova (1512), an attempt at Petrarchan poetry, by “Pietro painter from Arezzo.” Aretino always enjoyed styling himself as a connoisseur and a collector. His works and letters are replete with references to artists, works of art, and artefacts of all sorts.4 The sculptor Jacopo Sansovino (1486– 1527) and Titian (1488/90–1576) were among his closest friends but one should not forget his intimate friendship with Raphael (1483–1520), Giulio Romano (1499[?]–1546), as well as his turbulent relationship with Michelangelo (1475– 1564). Aretino always prided himself on his understanding of art although he

4 Lara Sabbadin, Materiali per lo studio della produzione di beni suntuari documentati nelle opere di Pietro Aretino e ‘dintorni’ (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Padua, 2013).

4

faini and ugolini

probably never achieved major accolades as a practitioner. In a letter to the sculptor Simone Bianco in May 1548 he wrote that, according to Sansovino and Titian, if he had been as good a sculptor or painter as he was a sharp critic, he would have been superior to many of those who are “inferior to no one.”5 At some point around 1516, Aretino moved to Rome where he discovered the secret to his originality as a writer thanks to the recently established vogue of satirical poems known as pasquinades.6 The biting satire of the pasquinades and the mask of Pasquino first gave Aretino a taste of fame. Aretino was able to turn an anonymous and conventional poetic mode into a personal language, and made it his trademark. Although the origins of Aretino’s myth as a Pasquinesque poet are murky, and scholarship is still grappling with the blurry corpus of his satirical writings, to his contemporaries Aretino and Pasquino became almost synonyms. Aretino cunningly exploited the flow of satirical poems attached to the Roman statue known as ‘Pasquino’, and the peculiar nature of a literary genre in which the notion of authorship was weak to say the least. Appropriating other authors’ compositions, as well as neglecting to acknowledge some of his own (at some point he claimed to have written hundreds of poems of which he had no memory), Aretino was able to create the mask of an author equally able to praise and please his patrons, and to threaten and destroy them.7 However, the language of the pasquinades and the mask of Pasquino soon became too small for Aretino. Yet his use of his literary works to ask for favors, and even to blackmail potential and ongoing patrons became the formula of his international success, for better or worse. The intrigues of the Roman papal court that were the subject of Aretino’s pasquinades became also the theme of his first comedy, meaningfully titled La cortigiana (The Courtesan; 1525). Aretino’s tumultuous days in Rome came to an end shortly after the publication of his controversial pornographic sonnets 5 Lettere iv, 394–395. 6 On this genre see Operette politiche e satiriche ii. See also: Valerio Marucci-Antonio MarzoAngelo Romano (eds.), Pasquinate romane del Cinquecento (Rome, 1983); Valerio Marucci (ed.), Pasquinate del Cinque e Seicento (Rome, 1988); Antonio Marzo (ed.), Pasquino e dintorni. Testi pasquineschi del Cinquecento (Rome, 1990); Chrysa Damianaki-Paolo Procaccioli-Angelo Romano (eds.), Ex marmore. Pasquini, pasquinate, pasquinisti nell’Europa del Cinquecento, Atti del Colloquio internazionale Lecce-Otranto 17–19 novembre 2005 (Manziana, 2006); Chiara Lastraioli, Pasquinate, grillate, pelate e altro Cinquecento librario minore (Manziana, 2012); Gennaro Tallini, “ ‘Iste omnes lacerat’: Antonio Lelio e la metamorfosi di Pasquino: critica politica e satira umanistica contro Leone x nel primo Cinquecento Romano,” in Paola Baseotto-Omar Khalaf (eds.), Voci del dissenso nel Rinascimento europeo (Mantua, 2018), 177– 201. 7 See Marco Faini, “ ‘E poi in Roma ognuno è l’Aretino’: Pasquino, Aretino and the Concealed Self,” Renaissance and Reformation, 40 (2017): 161–185.

introduction

5

known as I modi (The Positions) based on a series of engravings by the artist Giulio Romano.8 An assassination attempt in 1525, allegedly (but unlikely) perpetrated on behalf of the powerful Cardinal Giovanni Matteo Giberti, gives a sense of the threat posed by Aretino as well as the measure of his fame. Aretino was forced to leave the city—sparing himself the dramatic experience of the Sack of Rome—and took refuge at the Gonzaga court in Mantua. The “scourge of princes” (as Ludovico Ariosto defined him in the Orlando Furioso) thus found himself in the difficult position of court poet. In 1527 Aretino moved to Venice and became a protégé of Doge Andrea Gritti. The years spent in Venice, especially the 1530s, were a turning point in Aretino’s career. Thanks to the possibilities offered by the print market, Aretino was finally able to stop depending on patronage and to make a living from his literary works. It was in Venice where Aretino became the first author in the modern sense, turning the figure of the writer into a salaried professional. After seeking the patronage of the Medici popes (Leo x and Clement vii) in Rome, Aretino was now free to extend the network of his patrons, including not only Italian lords, but also the king of France, François i, and the emperor Charles v. In Venice, he established a productive collaboration with an innovative printer, Francesco Marcolini (?–1559): Marcolini printed beautiful editions of Aretino’s works, often displaying elegant woodcuts showing Aretino’s portrait.9 This was part of Aretino’s careful strategy intended to multiply his presence and to build a recognizable persona. While in Venice Aretino forged a solid relation with Titian. Aretino often accompanied Titian’s portraits of the great ones of Italy and Europe with ekphrastic sonnets. It was a well-established plan to mutually reinforce each other’s relevance, extolling each other’s craft; to re-instate the arts in a prominent position; and to vaunt the protection of powerful individuals, while also stressing the artists’ role in promoting the public image of those in power.10 In Venice Aretino had to come to terms with the towering

8 9

10

See Bette Talvacchia, Taking Positions: On the Erotic in Renaissance Culture (Princeton, NJ, 1999). On Marcolini see Amedeo Quondam, “Nel giardino del Marcolini. Un editore veneziano tra Aretino e Doni,” Giornale storico della Letteratura italiana, 157 (1980): 75–116; Paolo Procaccioli-Paolo Temeroli-Vanni Tesei (eds.), Un giardino per le arti: “Francesco Marcolino da Forlì.” La vita, l’opera, il catalogo (Bologna, 2009). On Aretino’s portraits see Élise Boillet, “L’autore e il suo editore. I ritratti di Pietro Aretino nelle stampe di Marcolini (1534–1553),” in Harald Hendrix-Paolo Procaccioli (eds.), Officine del nuovo. Sodalizi fra letterati, artisti ed editori nella cultura italiana fra Riforma e Controriforma (Manziana, 2008), 181–201. On Aretino and Titian see Luba Freedman, Titian’s Portraits through Aretino’s Lens (University Park, PA, 1995); Paolo Procaccioli (ed.), In utrumque paratus. Aretino e Arezzo, Aretino a Arezzo: in margine al ritratto di Sebastiano del Piombo, Atti del colloquio internazionale per

6

faini and ugolini

figure of Pietro Bembo. Aretino had long proclaimed his distance from the followers and imitators of Petrarch; Bembo was the most prominent among them. However, Aretino’s attitude toward Petrarch and Petrarchism underwent several changes and adjustments, which eventually led him to share at least some of Bembo’s views on poetry.11 Bembo, besides being one of the leading European intellectuals, had been appointed historiographer of the Most Serene Republic in 1530. His immense cultural and social influence inspired in Aretino a respectful attitude. In 1548, after Bembo’s death, Aretino wrote to his nephew Giovan Matteo, recalling an episode that took place in Rome at the time of Clement vii. After riding with Aretino the whole day, Bembo allegedly told the pope that he was leaving Rome but he was leaving “another me” in the city.12 This identification with the recently deceased cardinal was the peak of a process of approach to Bembo on the part of Aretino. Already in the early 1530s, when the poet Antonio Brocardo wrote some sonnets against Bembo, Aretino had intervened with a series of violent sonnets that allegedly pushed Brocardo to commit suicide (in 1531). Despite praising Brocardo after his death in a series of sonnets, Aretino always boasted to have been the author of the infamous sonnets leading him to his premature death.13 When Bembo was appointed cardinal in March 1539 (he was cardinal in pectore from December 20, 1538), Aretino began to hope that the same honor could befall him. It was probably with this goal in sight that he republished the whole corpus of his devotional works in 1551/52, when the reigning pope was Julius iii (Antonio Ciocchi Del Monte), also from Arezzo. Pivotal to Aretino’s identity as a professional writer was the invention of his correspondence as a literary genre per se. The publication of six volumes of let-

11

12 13

il 450° anniversario della morte di Pietro Aretino, Arezzo, 21 ottobre 2006 (Rome, 2008); Raymond B. Waddington, Titian’s Aretino. A Contextual Study of all the Portraits (Florence, 2018); Francesco Sberlati, L’infame. Storia di Pietro Aretino (Venice, 2018), 191–212; Paolo Procaccioli (ed.), «Pietro pictore Arretino». Una parola complice per le arti (Venice, 2019); Anna Bisceglia-Matteo Ceriana-Paolo Procaccioli (eds.), «Inchiostro per colore». Arte e artisti in Pietro Aretino, foreword by Enrico Malato-Eike D. Schmidt (Rome, 2019) ; Anna Bisceglia-Matteo Ceriana-Paolo Procaccioli (eds.), Pietro Aretino e l’arte del Rinascimento, exhib. cat. (Florence, 2019). Paolo Procaccioli, “Pietro Aretino sirena di antipetrarchismo. Flussi e riflussi di una poetica della militanza,” in Antonio Corsaro-Harald Hendrix-Paolo Procaccioli (eds.), Autorità, modelli e antimodelli fra Riforma e Controriforma (Manziana, 2007), 103–129. Lettere v, 81–82. Danilo Romei, “Pietro Aretino tra Bembo e Brocardo (e Bernardo Tasso),” in Angelo Romano-Paolo Procaccioli (eds.), Studi sul Rinascimento italiano—Italian Renaissance Studies: In memoria di Giovanni Aquilecchia (Manziana, 2005), 148–157; Antonello Fabio Caterino, “Ancora sulla polemica tra il Brocardo, il Bembo e l’Aretino: Fasi, documenti e fazioni,” Humanistica. An Internationl Journal of Early Renaissance Studies, forthcoming.

introduction

7

ters by Aretino (from 1538 to the posthumous volume of 1557), accompanied by two volumes of letters addressed to him, was fundamental in his self-fashioning as a crucial figure in the literary and artistic arena as well as in the political world, both in Italy and abroad. Before he died in 1556, Aretino could pride himself on his recognition as an interlocutor to Europe’s political and cultural elites, and as the author of works ranging from verse and prose satires to chivalric romances, from pornographic dialogues to religious and hagiographic writings. From the 1530s onward Aretino’s life was comparatively poor in events, but extremely rich in terms of literary achievements. He established himself in Palazzo Bolani, on the Grand Canal, from where he was able to weave a thick network of cultural and political relations. A curious man, fond of all sorts of arts—painting, music, architecture—Aretino established around himself what he termed an ‘Academy’: a circle of young scholars and writers with whom he entertained often conflicted relations (as was the case with two witty and talented writers, Niccolò Franco and Anton Francesco Doni). Aretino’s literary production was impressive: he tried his hand at almost all contemporary genres. We have already mentioned his satirical writings and his Petrarchan poems. It is worth noting that Aretino would never quit occupying himself in these kinds of poetry. Although he famously rejected the practice of imitating Petrarch (a powerful stance against Pietro Bembo, the major supporter of such practice), Aretino promptly recognized the legitimizing effect that producing Petrarchan poetry could generate in the eyes of contemporary literary society. He was ready to take advantage of the increasing success of printed anthologies of lyrical poetry;14 and as early as 1537 he published a collection of poems in Petrarchan style, the Stanze in lode di madonna Angela Sirena, probably in an attempt to gain attention and recognition by Bembo himself.15 Modern readers are certainly puzzled by Aretino’s production from the 1530s and early 1540s. As a matter of fact, he wrote comedies (Marescalco, a rewriting of the Cortigiana in 1534, Talanta, Filosofo, Ipocrito), chivalric romances (although they remain mostly unfinished) and, most notably, the two dialogues that go under the name of Sei giornate. The Ragionamento della Nanna e della Antonia (1534) and the Dialogo (1536), masterpieces of erotic and pornographic

14

15

See Marco Faini, “Appunti sulla tradizione delle Rime di Aretino: le antologie a stampa (e una rara miscellanea di strambotti),” in Dentro il Cinquecento. Per Danilo Romei (Manziana, 2016), 97–142. On the relationship between Aretino and Bembo see Paolo Procaccioli, “Due re in Parnaso: Aretino e Bembo nella Venezia del doge Gritti,” in Giorgio Patrizi (ed.), Sylva: studi in onore di Nino Borsellino (Rome, 2002), vol. 1, 207–231; Sberlati, L’infame, 179–191.

8

faini and ugolini

literature, are in fact a tremendously effective attempt at reversing the ethical principles set out for European elites by Baldassarre Castiglione in his Libro del Cortegiano (1528), and a biting satire of contemporary society. In them, Aretino ferociously lampoons the members of the clergy, making even more striking the fact that, in the very same years, he was busy elaborating a complex rewriting of the Penitential Psalms (Sette salmi della penitenza di David, 1534); a book on the Passion of Christ (Passione di Gesù, 1534); a book on the humanity of Christ (Umanità di Cristo, in fact a reworking of the Passione, 1535), and a book on the Genesis (Genesi, 1538). Scholars (such as Christopher Cairns, Élise Boillet, and Raymond B. Waddington among others) have long reflected on the nature of these works and of Aretino’s religious inspiration.16 Although the ultimate meaning of these writings is still unclear, it is certainly safe to affirm that when writing these religious works Aretino was not merely trying to please his patrons. Despite being removed from the court of Rome (in those decades probably the main court in Italy) Aretino continued to reflect on the nature of the court and on its effect on the psychology of courtiers, and on their ethical principles. He expressed such reflections on courts and courtiers in the Ragionamento delle Corti (Dialogue on Courts, 1538). Is the court the place for self-affirmation, or is it just a place where one’s true self is brutally effaced? And if the court has, among its nefarious effects, that of pushing courtiers to simulation and dissimulation, how is it possible to understand one’s true identity? Aretino further extended his interest in proto-psychology in a rather neglected work, the Dialogo del giuoco, also known as Carte parlanti (1543).17 A dialogue on the game of cards, in which the cards themselves discuss the various typologies of players, this work resembles an exercise in social physiognomy and psychology. In the 1540s, besides the aforementioned comedies and the Dialogo del giuoco, Aretino wrote three hagiographic works at the behest of his patron Alfonso d’Avalos and of his wife, Maria d’Aragona: La vita di Maria Vergine (The life of the Virgin Mary, 1539); La vita di santa Caterina (The life of the virgin Catherine, 1540); and La vita di San Tomaso d’Aquino (The Life of St Thomas Aquinas, 1543). At the same time, he kept on experimenting with literary gen-

16

17

Christopher Cairns, Pietro Aretino and the Republic of Venice. Researches on Aretino and his Circle in Venice (1527–1556) (Florence, 1985); Élise Boillet, L’Aretin et la Bible (Geneva, 2007); Raymond B. Waddington, Aretino’s Satyr: Sexuality, Satire and Self-Projection in SixteenthCentury Literature and Art (Toronto, 2004) and Subverting the System in Renaissance Italy (Farnham-Burlington, VT, 2013). The most recent edition of the text by Giuseppe Crimi has restored the original title, Dialogo nel quale si parla del giuoco. See Operette politiche e satiriche i.

introduction

9

res, writing a regular tragedy, the Orazia (1546, dedicated to the pontiff Paul iii). Most of all, he continued to write letters, some of which should be considered true masterpieces in the field of literary and art criticism. Aretino died in 1556 and left behind a legacy of attributed works (explored in this volume by Giuseppe Crimi), and a black legend that lasted for two centuries, until the Brescian erudite Giammaria Mazzuchelli (1707–1765) wrote Aretino’s first documented and reliable biography (1741, and 1763).18 In the years to come, the exceptionality of the figure of Aretino would be recognized by some influential scholars. At the end of the 19th-century, Jacob Burckhardt called him “the greatest railer of modern times,” also pointing out that Aretino may be considered the father of modern journalism.19 Burckhardt acknowledged Aretino’s literary talent and capacity for observation, and yet considered him someone not burdened with principles to the point of defining him as a beggar for the favor of the powerful, and stated that Aretino “only reviled the world, and not God,”20 judging his religious writings as mere self-serving attempts at obtaining a cardinal’s hat or at fending off any unwanted attention from the Inquisition. In the twentieth century, the publication of biographies of Aretino in English, Edward Hutton’s Aretino, Scourge of Princes (1922), Thomas Caldecott Chubb’s Aretino: Scourge of Princes (1946), and James Cleugh’s The Divine Aretino (1966) resulted in a renewed interest in his works among Anglo-American scholars. Yet, to many, Aretino remained, and partially remains, the scurrilous and licentious writer of pornographic sonnets and dialogues (suffice it to recall the numerous sexy B-movies dedicated to or inspired by him in Italy in the 1970s),21 and a morally questionable master of the art of blackmailing. It would be impossible, and probably beyond the scope of this Introduction, to assess here the huge corpus of scholarship on Aretino. Suffice it to say that it was only at the end of the nineteenth century that scholars belonging to the so-called “historical school” (scuola storica), fueled by a positivist, although not always unbiased attitude, undertook systematic archival work on Aretino, digging up from local archives and manuscript sources a wealth of information. Alessandro Luzio, Rodolfo Renier, Vittorio Rossi, and Abdelkader Salza are only few of

18 19 20 21

Giammaria Mazzuchelli, La vita di Pietro Aretino (Padova, Giuseppe Comino: 1741; Brescia, Pietro Pianta: 1763). Jacob Burckhardt, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (1st edition 1860; London, 1995), 107. On this point, see also Raymond B. Waddington’s essay in this volume. Burckhardt, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, 110. On Aretino’s fortune see Sberlati, L’infame, esp. last chapter, and Harald Hendrix’s essay (“Aretino’s Troubled Afterlife”) in this volume.

10

faini and ugolini

the scholars who contributed to the rediscovery of Aretino. Paul Larivaille’s 1972 dissertation, L’Aretin entre Renaissance et Manierisme, 1492–1537, represented a turning point in recent scholarship.22

2

The Companion to Pietro Aretino Project: Aims and Scope

Although recent decades have witnessed a renewed interest in Aretino’s works, a lot remains to be done to overcome the scholarly prejudice that has for a long time relegated Aretino’s writings to the field of marginal—or often even amoral—literature, and reduced this complex figure to stereotypes. The Edizione Nazionale of Aretino’s complete works, which was begun in the early 1990s, is now almost complete. The entry devoted to Aretino in the recent Catalogue of the autographs of the Italian writers has allowed to map Aretino’s autographs as well as to better understand Aretino’s strategies of publication (manuscript versus or along print) and to shed light on some crucial episodes of his life.23 At the same time, new documents have emerged from local archives that have improved our knowledge of Aretino’s familial background.24 The discovery and publication of previously unknown or neglected works, and new editions of well-known works in philologically accurate versions offer scholars the opportunity to reconsider Aretino’s literary contributions—contributions that until recently have often been available only in unreliable or incomplete editions. Aretino has raised an increasing interest also in the English-speaking world: Raymond B. Waddington’s monograph Aretino’s Satyr (2004) was crucial when it appeared, as was Bette Talvacchia’s Taking Positions. On the Erotic in Renaissance Culture (Princeton, 1999). Equally influential were Paul Larivaille’s biography titled Pietro Aretino (Rome, 1997), and Paolo Procaccioli’s numerous studies and editions of texts by and on Aretino (especially of his correspondence). Almost all of these scholars have contributed an essay to our companion. The Companion to Pietro Aretino intends to participate in this lively and renewed scholarly interest in Aretino’s works by gathering some of the most 22 23

24

Partially translated into Italian: Pietro Aretino fra Rinascimento e Manierismo (Rome, 1980). Paolo Marini, “Pietro Aretino,” in Matteo Motolese-Paolo Procaccioli-Emilio Russo (eds.), Autografi dei letterati italiani, vol. 1: Il Cinquecento (Rome, 2009), 13–36; Paolo Procaccioli, “Le carte prima del libro: di Pietro Aretino cultore di scrittura epistolare,” in Guido Baldassarri et alii (eds.), «Di mano propria»: gli autografi dei letterati italiani (Rome, 2010), 319–377. Teresa D’Alessandro Camaiti, “Documentazione locale su Pietro Aretino,” in In utrumque paratus, 55–76.

introduction

11

influential European and American scholars of Aretino’s writings In bringing together scholars from Europe and from the Unites States, working in different fields (literary criticism, history of religion, history of art, musicology, and history of the book) we are hoping that the combination of their different backgrounds, approaches, and methodologies will produce fresh insights and new interpretations. We have attempted to cover all aspects of Aretino’s multifarious literary production. This Companion was also born with the aim to explore previously neglected or little-studied areas of Aretino’s literary and biographical identity: in particular, his religious writings and their fortune, his relationship to music, his use of his private and domestic space as a way of self-fashioning, and his creation of his public persona as both a polemist and a polemical target. The essays here collected support the current scholarly trend that no longer considers Aretino merely as a pornographer with no religious sentiment, but interprets his work in the light of the contemporary religious debate and cultural crisis.

3

Themes and Structure

Our Companion to Pietro Aretino is comprised of seven sections, each of which explores a specific side of Aretino’s literary production, and connects it to the most relevant features of the culture of his time. The first section, “Selfhood and the Public Sphere,” investigates Aretino’s construction of his public figure, and his relationship to paramount historical events of the sixteenth century. In the opening essay, titled “Inventing the Celebrity Author,” Raymond B. Waddington explores how Aretino became a celebrity. While the fame of writers of the earlier generation, like Baldassarre Castiglione or Ludovico Ariosto, rested on their major opus, Aretino’s fame was first and foremost based on his persona. Waddington explores Aretino’s efforts at constructing a series of personae for his campaign of self-representation, and at becoming a popular character with a much-publicized life thanks to the help of the newly created printing press. Harald Hendrix’s essay, “Aretino At Home,” proceeds along the same lines by investigating how Aretino used his private life as an instrument of self-fashioning. Hendrix focuses on Aretino’s two Venetian residences, and analyses how these private residential spaces were arranged as ways for Aretino to project a precise, well-constructed image of himself. The second section, “Criticism and Satire,” focuses on Aretino’s well-known and often controversial activity as a satirist and his ambition to claim for himself the role of censor of contemporary social and political events. In “ ‘Pietro Aretino, the Ferocious Prophet,’ and Pasquino,” Chiara Lastraioli investigates

12

faini and ugolini

Aretino’s activity as an author of pasquinate in early-sixteenth-century Rome. Lastraioli illustrates how Aretino appropriated the mask of Pasquino—thus contradicting the previous tradition of anonymity of pasquinesque poetry— and how later in his career he kept adapting it to different cultural contexts. Paola Ugolini’s contribution (“Aretino and the Court”) is centered on Aretino’s complex relationship with the world of the court. A central topic of all Renaissance literature, the courtly world was paramount in Aretino’s production, either as a point of reference or as a satirical target. Ugolini’s essay sheds light upon the evolution in Aretino’s representation of the court, from his early years in Rome, to his condemnation of the courtly servitude in opposition to Venetian “freedom.” Ian Frederick Moulton’s essay, “Two or Three Things I Know about Her: Aretino’s Ragionamenti,” analyses the cultural economy of Aretino’s Ragionamenti by placing Aretino’s work in dialogue with Jean-Luc Godard’s film Two or Three Things I Know About Her (1967), underlining how in both works prostitution serves as a key to understand and critique shifting social relationships—personal, political, and economic. Aretino’s relationship with painting and sculpture is the center of the third section of the Companion, “Arts,” which includes an investigation of Aretino’s musical interests. In “Aretino and the Painters of Venice” Philip Cottrell focuses on a series of letters which Aretino wrote to Titian’s Venetian rivals between 1548 and 1549 in order to shed light on the real motives underlying such letters, and, more broadly on the status of the relationship between Aretino and Titian in those same years. The relationship with music is investigated by Cathy Ann Elias in the essay “Veritas Odium Parit: Uses and Misuses of Music in Aretino’s Sei giornate.” Elias explores the use of sound effects (from descriptions of noises of the environments and of the voices of the protagonists), and the use of musical performances in the Sei giornate in connection with the topic of pornography. The fourth section of the Companion to Pietro Aretino, “Literary Genres,” reassesses the role of Aretino with respect to the most prominent literary genres of the Renaissance: lyric poetry, chivalric romance, and theater. Angelo Romano’s essay, “Pietro Aretino, Poet” investigates Aretino’s poetic activity throughout his long and diverse career, paying particular attention to Aretino’s eagerness to experiment with different literary genres, and to the intertwining of the genres of satire and of encomiastic poetry. Maria Cristina Cabani’s “A Knot of Barely Sketched Figures: Pietro Aretino’s Chivalric Poems” explores Aretino’s attempts at providing a sequel to Ludovico Ariosto’s chivalric poem, Orlando Furioso. Cabani studies Aretino’s four chivalric romances (Marfisa, Angelica, Orlandino, Astolfeida), focusing on their main stylistic features, whilst also connecting them to Aretino’s biography. Deanna Shemek and Jane Tylus

introduction

13