Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel: Militarism and Feminism in Comics and Film [1° ed.] 0367894696, 9780367894696

This book explores representations of Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel in comics and film, as well as political struggles

217 84 16MB

English Pages 110 [111] Year 2020

Cover

Half Title

Series Page

Title Page

Copyright Page

Contents

List of figures

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1 Gender, violence, and militainment

2 Military service, empowerment, and diversification

3 The othering of adversaries and refugees

Conclusion

Bibliography

Index

Recommend Papers

![Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel: Militarism and Feminism in Comics and Film [1° ed.]

0367894696, 9780367894696](https://ebin.pub/img/200x200/wonder-woman-and-captain-marvel-militarism-and-feminism-in-comics-and-film-1nbsped-0367894696-9780367894696.jpg)

- Author / Uploaded

- Carolyn Cocca

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel

This book explores representations of Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel in comics and flm, as well as political struggles over these works, to illuminate contemporary cultural concerns about gender, sexuality, race, migration, imperialism, and war. It focuses on the only two female superheroes who have long histories grounded in feminist activism and military service, and who have starred in blockbuster origin flms at a time when resurgent progressive activism has been met by an emboldened backlash against movements for equality. Interdisciplinary and intersectional, the book employs insights from political science and political economy, feminist theories, critical race theory, postcolonial theory, and queer theory to explore how these characters’ feminism and militarism render them particularly appealing and proftable in contentious times. This is a concise, accessible text suitable for students and scholars in comics studies, media studies, flm studies, and women’s and gender studies. Carolyn Cocca, PhD, is Professor of Politics, Economics, and Law at the State University of New York, College at Old Westbury. Her Superwomen: Gender, Power, and Representation won the 2017 Will Eisner Comic Industry Award in the Best Academic/Scholarly Work category, and she has written numerous articles and book chapters on female superheroes and the importance of representation. She is also the author of Jailbait: The Politics of Statutory Rape Laws in the United States and the editor of Adolescent Sexuality. She teaches courses in U.S. politics, law, and gender studies.

Routledge Focus on Gender, Sexuality, and Comics Series Editor: Frederik Byrn Køhlert University of East Anglia

Routledge Focus on Gender, Sexuality, and Comics publishes original short-form research in the areas of gender and sexuality studies as they relate to comics cultures past and present. Topics in the series cover printed as well as digital media, mainstream and alternative comics industries, transmedia adaptions, comics consumption, and various comics-associated cultural felds and forms of expression. Gendered and sexual identities are considered as intersectional and always in conversation with issues concerning race, ethnicity, ability, class, age, nationality, and religion. Books in the series are between 25,000 and 45,000 words and can be single-authored, co-authored, or edited collections. For longer works, the companion series “Routledge Research in Gender, Sexuality, and Comics” publishes full-length books between 60,000 to 90,000 words. Series editor Frederik Byrn Køhlert is a lecturer in American Studies at the University of East Anglia, where he is also the coordinator of the Master of Arts program in Comics Studies. In addition to several journal articles and book chapters on comics, he is the author of Serial Selves: Identity and Representation in Autobiographical Comics. Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel Militarism and Feminism in Comics and Film Carolyn Cocca Batman and the Joker Contested Sexuality in Popular Culture Chris Richardson For more information about this series, please visit: www.routledge. com/Routledge-Focus-on-Gender-Sexuality-and-Comics-Studies/ book-series/FGSC

Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel Militarism and Feminism in Comics and Film Carolyn Cocca

First published 2021 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2021 Carolyn Cocca The right of Carolyn Cocca to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Cocca, Carolyn, 1971 author. Title: Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel in comics and film : militarism, feminism, and diversity in the superhero genre / Carolyn Cocca. Description: Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY : Routledge, 2020. | Series: Routledge focus on gender, sexuality, and comics | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: “This book explores representations of Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel in comics and film, as well as political struggles over these works, to illuminate contemporary cultural concerns about gender, sexuality, race, migration, imperialism, and war”— Provided by publisher. Identifiers: LCCN 2020021350 (print) | LCCN 2020021351 (ebook) | ISBN 9780367894696 (hardback) | ISBN 9781000169775 (adobe pdf) | ISBN 9781000169799 (epub) | ISBN 9781000169782 (mobi) | ISBN 9781003019329 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Wonder Woman (Fictitious character) | Captain Marvel (Fictitious character) | Comic books, strips, etc.—United States—History and criticism. | Superhero films—United States—History and criticism. | Literature and society—United States. | Militarism in literature. | Feminism in literature. | Cultural pluralism in literature. | Feminism in motion pictures. | Cultural pluralism motion pictures. Classification: LCC PN6725 .C588 2020 (print) | LCC PN6725 (ebook) | DDC 741.5/973—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020021350 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020021351 ISBN: 978-0-367-89469-6 (hbk) ISBN: 978-1-003-01932-9 (ebk) Typeset in Sabon by Apex CoVantage, LLC

Contents

List of figures Acknowledgments Introduction

vi viii 1

1

Gender, violence, and militainment

24

2

Military service, empowerment, and diversification

42

3

The othering of adversaries and refugees

61

Conclusion

82

Bibliography Index

89 98

Figures

0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4

1.1

1.2

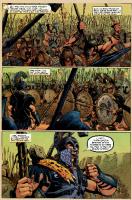

1.3

1.4 2.1

Wonder Woman’s first appearance, 1941 (art by Harry G. Peter, All Star Comics #8). Ms. Marvel’s first appearance, 1977 (art by John Buscema, Ms. Marvel #1). Carol’s new uniform in Captain Marvel #10 (art by David Lopez, 2014). Compare to Figure 0.2, Ms. Marvel #1 (1977), one hundred issues before. Diana’s revised costume with silver accents, higher boots, sword, and bracers in Wonder Woman #29 (art by Cliff Chiang, 2014). Compare to Figure 0.1, All-Star Comics #8, from over seventy years earlier. Captain Marvel flies parallel to bombs with American flags on them, a military weapon herself. We are not shown their target (art by Ed McGuinness 2012, Captain Marvel #3). Captain Marvel and one of her teams, the World War II-era time-displaced Banshees, analogous to the all-male Howling Commandos of comics and film, in fatigues and wielding various military weapons (art by Dexter Soy 2012, Captain Marvel #3). Etta Candy in fatigues and sunglasses, holding a military rifle, strategizing with Wonder Woman in the midst of a conflict in fictional Durovnia (art by Cary Nord 2018, Wonder Woman #60). Wonder Woman with Steve, wearing olive green and aiming a military machine gun on U.S. streets (art by Liam Sharp 2017, Wonder Woman #21). Wonder Woman (Gal Gadot) with her team: Sameer (Said Taghmaoui), Steve (Chris Pine), Chief (Eugene Brave Rock), and Charlie (Ewen Bremner).

10 12 15

17

32

34

35 35 50

Figures 2.2

2.3

2.4

2.5 2.6 3.1

3.2

3.3

3.4

Captain Marvel (Brie Larson) with her team: Talos (Ben Mendelsohn), Nick Fury (Samuel L. Jackson), Maria Rambeau (Lashana Lynch), and Goose the Flerken. Surrounded by Allied soldiers, a Belgian woman reaches out and pulls Diana to her, saying, “Help, please help.” Compare to Carol in Figure 3.3, also kneeling and comforting a refugee. Lt. Col. James “Rhodey” Rhodes and Col. Carol Danvers are an interracial military couple in the comics—until he dies, whereupon Carol holds him in a manner much more commonly seen with male characters holding dead female characters (art by Marco Failla 2016, Captain Marvel #7). Wonder Woman (Gal Gadot) embraces her full Greek god powers and strikes a glowing cruciform pose. Captain Marvel (Brie Larson) embraces her full Kree powers and strikes a glowing cruciform pose. Wonder Woman (Gal Gadot) begins her run across No Man’s Land, her hair streaming behind her, white skin stark against the gray-brown mud, American eagle-themed gold, red, and blue costume providing the only color. Wonder Woman shields brown children and women, some of whom wear head coverings, in Middle Eastern “Qurac” (art by Bilquis Evely 2017, Wonder Woman #20). Carol tries to comfort refugees at a camp apparently sponsored by the Red Cross and United Nations; she kneels and holds the woman’s hand in a manner similar to Diana in the film [see Figure 2.3] (art by Ramon Rosanas 2017, Mighty Captain Marvel #0). Carol is confronted by anti-alien, or anti-immigrant, rallies against her by those who fear her Kree origin (art by Carmen Carnero 2019, Captain Marvel #8).

vii

50

53

56 57 58

70

72

75 79

Acknowledgments

Thank you to, in alphabetical order, Erika Chung, Matthew Costello, Aidan Diamond, Chris Gavaler, Safyya Hosein, Miriam Kent, Christina Knopf, Samantha Langsdale, Anna Peppard, and Adrienne Resha for their comments on the formation of this project, on the proposal, and on the draft (or two, in some of their cases). I met several of them only a few months ago at the Comics Studies Society conference, and am so pleased to now have them in my circle. Errors and omissions within are mine, as all of them gave me excellent feedback. Thank you, as always, to my family: my mom, Anne; my partner, Steve; our kids, Anna, Amelia, and Theo. I could not have completed this project without their support and encouragement, as well as their editorial comments. And to my friend and colleague families as well, from Talking Comics, Batgirl to Oracle, Old Westbury, and Shaker. I write these acknowledgments on International Women’s Day, and during a global pandemic. Both call attention to longstanding structural inequities and injustices due to sexism, racism, heterosexism, religious animus, xenophobic nationalism, ableism, imperialism, and colonialism. I hope that I communicate within that while we can and should celebrate individuals’ successes within such systems, we cannot and should not be diverted from collective organizing for liberation for all.

Introduction

The stories of Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel are not “just comics” or “just movies.” These works circulate globally, engender intense emotions in fans and immense profts for their parent companies, and are embedded in a fraught historical moment in which the hard-fought gains of multiple civil rights movements have been met by an emboldened backlash against equality and equity. Not unlike other popular, prominent, and proftable characters, they are sites of struggle over numerous cultural concerns about gender, sexuality, race, nation, violence, war, migration, imperialism, and capitalism. What makes these two characters so distinctive is their portrayals as simultaneously feminist and military superhero women, and that is the focus of this book. Much has been written about both the discomfort produced by and the disruptive potential of the figures of the female superhero and the female soldier.1 But the combination of the two, the female superhero soldier, is more than the sum of its parts. This is not only because such a figure can reveal multiple cultural narratives and counternarratives about gender and power through a differently focused lens. It is also because of the ways in which Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel’s military affiliations can ease anxieties about their being feminist superwomen, and their being feminist superwomen can ease anxieties about their military affiliations. The spectacle of female characters using violence in alliance with militaries, and the films’ stars working with real-life militaries, can render the characters’ woman-ness more palatable to readers, viewers, and corporate executives who feel uneasy about women entering the overwhelmingly male domains of the superhero or the soldier. As superpowered women, they negate arguments that women aren’t strong enough for combat. As military women, their potentially disruptive superstrength is contained as they act in concert with a hierarchical and disciplined organization made familiar through its regular

2 Introduction depictions in popular culture. At the same time, military violence performed by female characters who show care for vulnerable others, and by female actors who have publicly identified as feminists, can render the characters’ violence more palatable to those who have anxieties about its authoritarian and military use. These independent, strong, capable, and empathetic women bring feminist values into places commonly constructed as hypermasculinized and unfairly exclusionary, that of the superhero and that of the soldier. Because they assuage concerns about disrupting structures through their conformity and at the same time display inspirational individual female strength, these women superhero soldiers are particularly appealing and profitable across the political spectrum. As such, the feminism performed by these characters is highly contestable and illuminates debates about the diversification of both the military and the superhero genre. They embody the success of advocacy for inclusion in the armed forces as a mark of equality, as they are affiliated with and loyal to military institutions that provide women, people of color, and LGBTQ+ people with economic and leadership opportunities and cultivate individual empowerment in service of national and international security. But they also represent other feminists’ critiques that women’s military participation serves an unjust and imperialist nation, as they are affiliated with and loyal to military institutions that discriminate against multiple groups in the U.S. and deploy intimidation and force against multiple peoples abroad. In these ways, and as this book will detail, Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel’s military attachments work both with and against their feminist origins and story histories in ways distinct from their male counterparts. Seen through liberal feminist frames, these characters represent women fulfilling their potential through exerting power in ways that had long been denied to them.2 The diversification of the military and other institutions has come in part from successful progressive and organized pressure from marginalized groups who have long advocated for better representation in order to disrupt longstanding societal inequalities. These contemporary women are no longer confined to auxiliary or nursing roles (like Wonder Woman’s civilian identity, Diana Prince, at her origin) and no longer barred from combat (like Captain Marvel’s civilian identity, Carol Danvers, at her origin) due to gender stereotypes. Rather, they are clearly (super)capable, and they work collaboratively within and alongside these institutions, in teams with other women and men, to end war and protect the vulnerable.

Introduction

3

In parallel ways, companies that produce superhero fiction have been pushed to become more inclusive, to hire more women as creators and actors, and to feature less stereotypical presentations of female characters. Wonder Woman film star Gal Gadot’s having served in the Israeli military with other women, as well as Captain Marvel film star Brie Larsen’s work with female pilots in the United States Air Force, display the increased inclusiveness of these military organizations as well as the increased inclusiveness of superhero media, and are to be celebrated. Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel’s stories can thereby be received as containing pro-civil-rights, pro-feminist, progressive elements in which these female heroes and their diverse allies represent collective liberatory struggles in a still-unequal world. Seen through critical race, queer, disability studies, and postcolonial feminist approaches, these physically fit, force-wielding, young, white, cisgender, nonqueer, nondisabled superhero soldiers are glamorized via their comic and film representations as well as via the actors’ work with personal trainers and military organizations, while the costs of real-world othering, discrimination, violence, and war are downplayed. Such stress on individualized personal transformation can divert attention from the need for cooperative, collaborative, longterm struggles for liberation. The comics and films starring these characters thereby display postrace and postfeminist sensibilities in that they take into account the ideals and gains of twentieth-century liberal movements for race and gender equality, and they celebrate the inclusion and centering of individuals from formerly excluded populations as fictional characters, as actors, and as soldiers. But they do this only insofar as to suggest that we have moved past the need for such movements, and that marginalized people need only make themselves over and “lean in” to succeed. They tend to elide the differences between diversity and equity, and as such, they do not systematically challenge structural and continually produced inequities, such as women and people of color’s persistent underrepresentation in multiple institutions and in leadership positions, as well as their bearing most of the costs of individual and state violence. The two characters’ stories, therefore, may appear in some ways feminist, but they are more aptly described as white hegemonic feminism that privileges certain women at the expense of others.3 Their portrayals serve less as tales of liberation and more as “militainment,” or entertainment that normalizes military-level violence by individuals or military intervention by a state as ordinary and as necessary.4 They are enmeshed in neoliberal rationalities that posit a singular person and her empowerment as primary, along with a neoconservative enterprise

4

Introduction

that embraces the morality of righteous authoritarian warmaking and serve to reify an unequal and often brutal status quo.5 Because of all of this, Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel’s contemporary stories, as well as paratextual materials from their producers and actors, encompass elements that can be received as both progressive and conservative, as both fomenting equity and reinforcing longstanding hierarchies. They center women in their own stories in a manner still unusual in the superhero genre. The characters use their strength, based in love, as they protect friends and vulnerable strangers. They work with diverse coalitions in terms of gender, race, ethnicity, sexuality, and ability; they rely on forged families and communities who seek peace; and their film versions starred women who identified as feminists in interviews and on social media. But these same texts can be viewed as advancing only individual women who conform to dominant cultural narratives and don’t disrupt broader structures. The characters remain among only a small number of privileged superheroes that often act indistinguishably from male superheroes, and they use violence to subdue foreign, alien, othered enemies and to safeguard nameless masses of people of color. They lead their allies and save the day as privileged, empowered individuals; they wear red, blue, and gold as exceptional warrior soldiers for the U.S.; and the film’s stars engaged in elite physical training and praised the U.S. and Israeli militaries in uncritical ways. All of this makes the representations of these two characters, their militarism, their feminism, their allies, and their “others” uniquely illuminating, uniquely contested, and uniquely marketable. To explore these woman superhero soldiers and the numerous anxieties they provoke and assuage, this book employs insights from political science and political economy, multiple feminist theories, critical race theory, postcolonial theory, disability theory, and queer theory, particularly as applied in cultural and media studies and more specifically in comics and film studies.6 It utilizes these interdisciplinary and intersectional approaches because they share concerns about inequalities, and they analyze multiple vectors of discrimination and oppression as well as their multiplicative combinations. Dominant cultural narratives enmeshed in harmful stereotypes have been propagated and circulated in ways that undergird the political, economic, and social marginalization of numerous groups, and these approaches seek to analyze and disrupt such narratives as well as highlight and produce counternarratives centering those historically silenced and stereotyped. These approaches are applied to a data set consisting of Wonder Woman comics from their 2011 reboot to March 2020 (144 issues)

Introduction

5

and the 2017 Wonder Woman film, as well as Captain Marvel comics from their 2012 relaunch to March 2020 (82 issues) and the 2019 Captain Marvel film. The data set also includes paratextual material from interviews with and social media posts by the creative teams behind the characters, including the film actors. The rest of the introduction situates the characters of Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel within the context of the longstanding lack of diverse and authentic representations in superhero comics and films, and the increased but also limited diversification. It discusses the unique origins and contemporary portrayals of these two characters as not just female superheroes but specifically feminist and militaryaffiliated superheroes. These characters are currently much less stereotyped and sexualized than in their pasts, and their military loyalties are more at the forefront. They have more diverse allies than in their pasts, and they continue to demonstrate care for those both like and unlike themselves. The introduction also notes that their particular super-ness is quite exceptional: it is enhanced by their similarities to male characters, their revised origin stories, and their increased use of military violence; and it tends to shore up dominant categories of race, class, sexuality, ability, ethnicity, and nationality. Then, the core of the book is about these superheroes as soldiers, evaluating the comics and films’ centering of female characters and their allies through military and war-related themes. It includes chapters about (1) representations of superhero women’s violence in militainment that employs the aesthetics of military work for entertainment; (2) their personal empowerment and their work with diverse military allies, and these elements’ relation to the increased diversification in the superhero genre and in the U.S. military itself; and (3) the characters’ use of military violence against others via warmaking and other anti-terror actions, as well as their protection of various others such as migrants and refugees. These representations may be read as liberatory due to their inclusiveness and nuance, and their emphasis on the strength of marginalized groups. They may also be read as neoliberal and neoconservative due to their focus on individualized uses of violence against singular othered enemies, and their reinscribing of white savior tropes, in ways that mask multiple structural inequalities. The conclusion is concerned with themes of individualized empowerment versus those of collective liberation in the superhero genre and reflects on how and why, given these two prominent female characters’ portrayals in comics and film, representations and receptions of those themes may change when the central character is a woman. It reflects on the diversity of the superhero genre and of military institutions, and

6 Introduction on the costs of othering and violence to marginalized populations at home and abroad.

Contextualizing the contemporary Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel Female superheroes have been underrepresented, stereotyped, sexualized, and sidelined for most of the history of the superhero genre.7 That one even has to use the descriptor “female” with the word superhero, but would probably not use the modifer “male” in the same way, shows rather quickly that superheroes are assumed male. Given the numbers, this is not an unreasonable assumption. Female characters star in about 15% of superhero comics in 2020, with about the same percentage being written or drawn by a female creator. In 2015 it was about 12%, in 2010 about 6%, and in 2000 about 5%. Women star in about 16% of superhero TV shows on air or in development, and in about 18% of flms scheduled for release or in development.8 However, given that women are 50% of the population, these proportions are quite low. And given that most of the women represented in superhero media are white, cisgender, nonqueer, and nondisabled, they are even more unrepresentative than they at frst appear. From the end of World War II, when women were pushed out of creative roles, almost every comics creator was white and male. While over the last seventy-five years some of these creators produced absolutely excellent stories centering on women, most of them produced stories with small numbers of stereotypical women with their “femaleness” as their main character trait. The 1950s Wonder Woman spent a lot of time entertaining marriage proposals from Steve Trevor, and Batwoman spent a lot of time trying to get Batman to propose to her. The 1960s Sue Storm and Jean Grey designed their teams’ costumes and fainted when they used their powers too much. Wonder Woman was the only woman on the Justice League, Sue on the Fantastic Four, Jean on the X-Men, and Wasp on the Avengers. The 1970s Ms. Marvel would pass out after crimefighting and took time out from it to admire her skintight and skimpy costume in the mirror. Storm, in a similar outfit, would lose control of her weather-based powers when she was emotional. The 1980s Batgirl was the only female superhero in Gotham, and her most famous story was being shot and sexually assaulted in order to show the crimes’ effects on Batman and on her father. Wasp’s most famous story was being hit by her husband, AntMan. The small number of black female superheroes, like Vixen or Storm, were generally exoticized with animal and earth-based powers

Introduction

7

or rendered with Blaxploitation elements like Misty Knight and Monica Rambeau. The small number of female superheroes with Asian heritage or appearance, like Katana or Colleen Wing or Psylocke, tended to use martial arts and swords, and Jubilee used fireworks. In the 1990s and 2000s, these characters and others were posed in tight or scanty clothing and with physics-defying broken backs, more eye candy than hero, still usually the only woman or perhaps one of two on a team. There are of course exceptions to these types of portrayals in terms of certain comic runs’ text and/or art, and these characters and others remain beloved by many for their heroism and strength. But several unfortunate trends stand out when one looks over the long time span: underrepresentation, heteronormativity, Bechdel test failures, stereotyping, fridging, exoticization, and sexualization. All of them are narrative devices that—and all of them are conscious choices to—display women as one-dimensional objects rather than portray them as multidimensional people. Decisions to represent women in this way are political in nature. Just as political are the decisions to repeatedly center and drastically overrepresent white, cisgender, nonqueer, nondisabled males as superheroes. There are costs to these politics, to showing repeatedly that certain people are super, and multifaceted, and powerful, and everyone else is not. People of color, people with disabilities, people who are LGBTQ+, women—most of the people in the world—are dramatically underrepresented on superhero comics pages and onscreen, as they are in positions of power in all of our institutions. When almost all of the stories out there exclude that majority or repeatedly show them as stereotypes, it becomes more difficult to imagine them as heroes and leaders and more difficult for others to see them that way. It is, simply, wrong and harmful. This is why pro-civil-rights groups, for decades, have been pushing for visibility for excluded groups as part of their broader goals for equality and equity. Changes in representations in the superhero genre became both more evident and more contested in the 2010s, the decade in which this book is grounded. This occurred against a background of gains of multiple civil rights movements, the rise of social media and the increase in comics conventions that enabled more interactions between fans and creators, the ability to access superhero films and TV shows and digital comics at home, bookstores and libraries carrying trade paperbacks, and some creators and some fans actively pointing out the underrepresentation and stereotyping noted earlier. The number of women behind the scenes and female characters on the page increased

8

Introduction

together, and renditions of the latter in general became less objectifying and more nuanced. New characters were launched and old characters were relaunched in comics and on TV. About half of these were women of color, and/or queer and transgender women. New male characters were created as well, such that the proportion of males to females remains roughly the same: out of over 34,000 Marvel and DC characters, there are about three times as many male characters as female characters (Shendruk 2017). Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel were relaunched by their parent companies in 2011 and 2012, respectively. From the relaunch point to 2020, the Wonder Woman comic had eight writers, three of whom were women (38%). Out of thirty pencillers, seven were women (23%). The Captain Marvel comic had six writers or writer-teams, with women represented in each one (100%). Out of twenty-three pencillers, eight were women (35%).9 These percentages are quite high not only compared to other superhero comics, but also compared to past Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel comics, which had been dominated over their roughly eighty- and fifty-year histories by male creators. These teams both picked up on consistent threads in the histories of these characters as well as created new ones. This is also the case with their origin films of the later 2010s. The next section is more specific about the origins of the characters and trends in their portrayals over time, particularly in terms of their military roots, gender stereotypes and subversions in their appearances and personalities, and the diversity of their allies. This serves as background to the core of the book about the military nature of their representations.

Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel’s origins and trends in their portrayals Both Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel were created as feminist and military characters, who worked in military organizations and had military boyfriends and friends. Diana Prince/Wonder Woman would achieve the rank of Major. She would directly work for and/or afliate with the Army, Ofce of Strategic Services, Air Force, Navy, NASA, U.N., U.N. Crisis Bureau, shadowy A.R.G.U.S., Department of Metahuman Afairs, and Justice League, and she would work alongside those on active duty such as her longtime boyfriend, Master Chief Steve Trevor, and best friend Commander Etta Candy. Carol Danvers/Captain Marvel would achieve the rank of Colonel. Her military work would include the Air Force, Air Force Special Operations,

Introduction

9

NASA, Department of Homeland Security, shadowy S.H.I.E.L.D. and S.W.O.R.D., Alpha Flight, and Avengers, and she would work alongside her Air Force Special Operations boyfriend Michael Rossi, current boyfriend Lt. Col. James “Rhodey” Rhodes/War Machine, and an allfemale military unit called The Banshees. In their initial runs in the 1940s and 1970s, times of burgeoning equality for women, both of these characters were physically strong, white, cisgender, nonqueer, nondisabled superheroes who would rescue themselves and others. Both had professional and predominantly military day jobs, both had (white female) friends, both had (white male) love interests, both would challenge men who underestimated them due to their sex, and both basically wore bathing suits with boots over their hourglass figures. Neither had feminine “pose-and-point” powers such as telepathy or magic, but they would use their physicality when necessary. These representations integrated stereotypically female personality traits with stereotypically male ones in one body, or, one could argue, they were just more nuanced characters than many of their female and male counterparts.10 William Moulton Marston believed that women were not only equally capable but also morally superior to men, and he created Wonder Woman as such in 1941. Diana is shaped from clay by her Amazon mother and given life by goddesses, and goes to Man’s World both to return military man Steve Trevor to the U.S. and to teach peace, love, and equality. As seen in Figure 0.1, artist H.G. Peter drew her with a petite, white body, shoulder-length black hair with a tiara, lipsticked mouth, red strapless low-back bustier with gold eagle, blue split skirt (soon to be shorts), red mid-calf skinny-heeled low-back boots, and bracelets. Iconic and beloved, this outfit is simply absurd in ways that male character’s full-coverage spandex is not. It would be uncomfortable in multiple ways and impossible to keep on if active. But it allowed the creative team to show the main character’s comfort with her body in contrast to the judgmental people of Man’s World. Its skimpiness also allowed them to appeal to what they perceived male readers would like. In the World War II years, she uses her courage, diplomacy, bracelets, and lasso of submission, with force as a last resort. Alone, with other Amazons, or with best friend Etta Candy and her sorority sisters, she would subdue male villains and try to redeem female ones. She loves Steve Trevor and works alongside him in the Army, but rejects his marriage proposals so she can continue her mission and resist unequal gender roles. Her allies were white, like Etta and Steve, and nonwhite characters were portrayed in stereotypical ways. This

10

Introduction

Figure 0.1 Wonder Woman’s frst appearance, 1941 (art by Harry G. Peter, All Star Comics #8).

shoring up of heterosexuality and whiteness, along with the contrast between Diana’s slim body and Etta’s more stout and curvy one, softens her challenge to multiple dominant cultural narratives. Many representations of Wonder Woman, particularly those in the mid-to-late 1980s, the 2000s, and late 2010s, would conform to this type of portrayal while also diversifying the cast and further subverting heteronormativity and binary gender roles. This challenge would basically fall away from Marston’s death in 1947, through the forging of the 1954 Comics Code, and through most of the 1960s. The book under Robert Kanigher’s direction would focus on marriage proposals from men, romance with otherworldly creatures, and fighting crime and monsters. He replaced her female

Introduction

11

allies with a confusing “Wonder Family” consisting of Diana at older and younger ages, and declared that Diana had a father lost at sea. New artists replaced her boots with sandals, lengthened her hair, and made her eyes and curves bigger and her shorts smaller. This exaggerated femininity, coupled with an emphasis on fighting rather than subduing, reforming, or teaching, would remain another facet in Wonder Woman’s portrayals, particularly in the mid-1990s, and early and mid-2010s. If Wonder Woman embodied a particular strand of First Wave feminism, Ms. Marvel did the same with Second Wave feminism. In 1977, Gerry Conway wrote Wonder Woman as well as the new Ms. Marvel title. His writing in both engendered fan letters praising his portrayals of these women, and also ones that accused him of producing characters with “man-hating tendencies” (Wonder Woman #240) who acted as a “soapbox for women’s lib” (Ms. Marvel #3). Marston had said that he created Wonder Woman to be both a female and a strong character, because soon the “traditional description ‘the weaker sex’ . . . will cease to have any meaning” (Richard 1942). Conway wrote similarly in Ms. Marvel #1 that the title character, Carol Danvers, was “influenced by the movement toward women’s liberation.” Writer Chris Claremont would create Carol’s backstory: her father would not pay for her to go to college because she was a woman, so she enlisted in the Air Force, getting her education paid for and working her way up through various military jobs. He would also make increasing references to her stubbornness and temper, which differentiated Carol from Diana. Ms. Marvel’s first costume, as seen in Figure 0.2, was a red, gold, and black long-sleeved leotard with a bare stomach and back, with a long red scarf and black gloves. Like Wonder Woman, she had bare legs and boots. Unlike Wonder Woman, Ms. Marvel’s name and outfit derived from that of a male superhero: Captain Marvel. She wore his fullcoverage outfit—minus the stomach, back, and legs. This alien, male, pink (i.e., white) Kree named Mar-Vell had been Carol’s love interest from her introduction as a non-super NASA Security Chief in 1968, and she had received her powers from an exploding Kree machine and Mar-Vell’s Kree DNA while caught between him and his enemy, YonRogg. She lost consciousness and Mar-Vell carried her to safety. This loss of consciousness would recur in her initial adventures—the “feminine” human Carol Danvers would black out to become the “masculine” Kree warrior Ms. Marvel, then wake up later with amnesia. This is similar to perceptions of Wonder Woman as exhibiting “feminine” compassion and care while also being a “masculine” Amazon warrior.

Figure 0.2 Ms. Marvel’s frst appearance, 1977 (art by John Buscema, Ms. Marvel #1).

Introduction

13

It also recalls the old trope of women fainting when exerting themselves. Within a year, her personas were unified, and her costume was changed by artist Dave Cockrum to a sleeveless, high-necked black leotard with a lightning bolt replacing the Kree star, thigh-high boots, and the red scarf around her waist. Working at Woman magazine after leaving NASA (where Wonder Woman was briefly in the late 1970s), she has a few female friends, and she goes on dates with a few different men. As in Wonder Woman, all of these characters were white and heterosexual. In the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, the two characters would continue to have parallels. George Pérez’s Wonder Woman returned the character to her mythological roots, surrounding her with a more diverse set of Amazons who he explained to be the reincarnated souls of those killed by intimate partners. He implied that some were in queer relationships, created new female allies for Diana, and made Steve and Etta a couple. In these ways, he did not conform to the prevailing trends in the superhero genre toward hyperviolence and hypersexualization, although her mid-1990s stories as drawn by Mike Deodato did. With the Ms. Marvel title cancelled in 1979, Carol would appear in Uncanny X-Men and in Avengers, where she was put through multiple trials: rape and impregnation, having her memories stolen, increased powers due to aliens’ experimentation on her, alcoholism, more instances of a split personality. Like Wonder Woman, in the 1990s and 2000s she would become more violent and more sexualized, posed in unnatural ways with her curves more prominent and her costume covering less. Both would work in military and security capacities at government agencies in the mid-2000s, Diana at the Department of Metahuman Affairs, and Carol at the Department of Homeland Security. Both would have memorable stories: for Wonder Woman, as written by Phil Jimenez, Greg Rucka, and Gail Simone, in ways similar to Pérez and Marston; for Ms. Marvel, in Avengers as written by Kurt Busiek and drawn by Pérez and others, and in a new eponymous title by Brian Reed in ways similar to Claremont. Outside of the main titles, though, different renditions of the characters in the 2000s received more attention: for Wonder Woman, this was the Justice League cartoon, and the Kingdom Come, OMAC Project, and New Frontier comics. These works picked up more from 1950s, 1960s, and 1990s interpretations of Diana as less about peacemaking and more about fighting; less the teacher and more the warrior. Not only are her powers greatly ramped up, but also, she kills people, which she had not before done. The way Carol was written in the Super Hero Squad and Avengers cartoons, as well as the prominent

14 Introduction comic Civil War, was similar: extremely physically strong, more willing to use force, and rather humorless and strident.

Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel in the 2010s It is their 2010s portrayals, after their titles relaunched, that are the heart of this book. Within the context of a broader and more vocal fanbase, new writers and artists with diferent sensibilities, and companies looking to incorporate new customers, the new portrayals of the characters would show them much less often drawn as a “bad girl” or a “sexy lamp,” more often surrounded by diverse allies of women and men, more physically powerful than ever before, and generally centered and heroic in their own stories. The nature of the relaunches was specifc to the companies involved, but both were received with excitement by some and consternation by others.11 For Wonder Woman, the major changes were the initial desexualization of her portrayal albeit still in her usual outfit, the rewriting of her origin story, and her increased use of violence. For Captain Marvel, it was a desexualized portrayal in a new full-body costume, the rewriting of her origin story, and the shedding of the moniker of “Ms.” for that of “Captain.” A small number of vocal fans criticized the character’s shorter hair and covered body; presumably, this was the same population who would feel similarly threatened by actor Brie Larson’s unsmiling face on film posters, and by her statements about equality in media coverage and pay, such that they criticized her as well. But most old fans embraced the modernized Carol, and new and enthusiastic fans were made. Many clearly embraced the 2010s comics and film portrayals of both of these characters, as can be seen in increased sales of comics and record-breaking film ticket numbers, coverage of both characters and their fans not only in comics journalism but also in mainstream media, cosplay and interactions with their creators at conventions, and the volume of social media posts about them. Captain Marvel’s new uniform is grounded in her history as it resembles that of the first (male) Captain Marvel. It was produced by collaboration between editor Steve Wacker, writer Kelly Sue DeConnick, and artist Jamie McKelvie for a military-inflected outfit that covered her body and connoted authority, and in which girls could cosplay. The cover to Captain Marvel #10/100 by David Lopez (Figure 0.3), an homage to Ms. Marvel #1 by John Buscema (Figure 0.2), makes the differences in uniform and content clear: her body is now fully covered and her chest-to-waist ratio more realistic, she is posed on the left standing in a flight suit near a jet rather than seated on a desk, her

Figure 0.3 Carol’s new uniform in Captain Marvel #10 (art by David Lopez, 2014). Compare to Figure 0.2, Ms. Marvel #1 (1977), one hundred issues before.

16 Introduction allies on the right are not all white adults, and instead of promising just “All-Out Action!” the later cover promises “All-Action!” that is “All-American!” But it is also the case that the look of a navy blue costume with red accents and a bright mid-chest star, along with prominently shooting light/energy out of her hands and being close to James Rhodes (pictured at right in Figure 0.3), combine elements of Captain America and Iron Man. The new Captain Marvel is more her own woman than she’s ever been in many ways, with a high-level power set, appealing greatly to fans wanting a strong but not perfect woman for whom they can root. But some of her appeal is probably tied to her resemblances to these very popular white, male, heterosexual superheroes. Similarly, Wonder Woman’s post-2011 clothing by Jim Lee references her origin, with her powers and weapons more recent. The costume was basically the same except the accents were silver instead of gold, the red and blue were darker in hue, and her knee-covering boots were blue. For her eponymous title, artist Cliff Chiang said in multiple interviews that he took care to greatly desexualize the character as compared to her past portrayals. The costume was modified in 2016 by Tony Daniel, based on the Batman v Superman movie’s design, with a small paneled skirt, over-the-knee red boots, and again-gold accenting. Her post-relaunch powers make her quite similar to Superman in strength and invulnerability and to Thor in her control of lightning. Further, since this relaunch, she has regularly been depicted with a sword and with bracers from wrist to elbow. These offensive weapons contrast with her original ones, which were defensive: a lasso and small bracelets. This increases her appeal to those who specifically want to see a strong and sexy but not sexualized woman, and to those who find a strong woman more palatable when she utilizes “male” superpowers and weapons and still wears a skimpy outfit. Their origins had changes as well. DeConnick wrote in 2012 that Carol time-traveled to the moment of the Kree machine explosion and chose to allow herself to get the powers via the machine and the male Kree Mar-Vell, giving her some agency in the matter. A more substantial revision, by Margaret Stohl in 2018, was that Carol’s mother was herself Kree, such that the explosion awakened Kree powers within Carol. As the Kree are constructed as a warrior monoculture, this explains somewhat Carol’s tendency to use violence more readily than others; it is “natural” to her. It also ties her more closely to her mother, and her powers now come from a woman rather than a man. The film merges these ideas: Carol is near the machine because of her female

Figure 0.4 Diana’s revised costume with silver accents, higher boots, sword, and bracers in Wonder Woman #29 (art by Clif Chiang, 2014). Compare to Figure 0.1, All-Star Comics #8, from over seventy years earlier.

18 Introduction Kree mentor Mar-Vell, and she chooses to set off the explosion; this increases her agency and ties her to female power. Wonder Woman’s revised origin from 2011 was more controversial. Instead of being born from clay shaped by a loving mother, she is in comics and film the product of her mother’s affair with king of the gods Zeus. Instead of being raised by peace-seeking and loving Amazons, she grows up among Amazons who dislike and fear her, who rape and kill sailors to reproduce, and who keep female babies and sell the males into slavery. Instead of the god of war Ares being her arch-nemesis, he is her mentor. Instead of earning the title of Wonder Woman by working to become the best of the Amazons with their encouragement, she is such because of her demigod powers and Ares’s mentorship, and in spite of how poorly the Amazons have treated her. Her queer, peaceful, and matriarchal origin, unique among all superheroes, was replaced by one that renders her little different from others and makes her increased use of violence, like Captain Marvel, only “natural.” Long-time fans, and particularly self-described feminist fans, were aghast; others felt it was not a big deal, and still others found her more easily understandable due to the male god parentage explaining her birth and her powers. This move was meant to boost sales to men: writer Gail Simone noted that she was constantly pushed to write more male characters into the title when she was writing it for that reason (Simone 2017 (12 July) tweets). The revised origin also undercut longstanding perceptions of Wonder Woman as queer. Before that, as she was from an harmonious all-female island of immortal women, it seemed rather likely that at least some of these women were having relationships with one another. That she fell in love with the first man she saw, Steve Trevor, and continues to be coupled with him on and off through to the present, undercuts her queerness for some but doesn’t erase it. For others, Steve is her primary relationship, and until quite recently she had only been shown with other men, underlining her heterosexuality. From the late 1980s with George Pérez, and then with Jimenez, Simone, and Rucka in the 2000s, other Amazons were implied or shown to have relationships with other women, including Diana’s mother with the black general Philippus. In the late 2010s, Rucka wrote Etta Candy—still stout, still curvy, still military, now African American— as being in a relationship with the white Dr. Barbara Ann Minerva, aka Cheetah. He said in interviews that of course Diana was queer. In text he has Diana tell Steve that she had “someone special” named Kasia. Nicola Scott draws the white and blond Kasia kissing Diana on the cheek, as a few other Amazons say that they assume Diana

Introduction

19

had a relationship not only with Kasia, but perhaps with two other women as well (Wonder Woman #10 and #2, 2016). One can also read these two issues as not providing evidence for a romantic relationship. The same is true of the film, when Diana tells Steve that she has read “Clio’s treatises on bodily pleasure” so she knows that “men are essential for procreation, but when it comes to pleasure, unnecessary.” This may mean she has acted on this knowledge, or would like to, or perhaps not. Writer G. Willow Wilson introduced the character of “Atlantiades of the Erotes, the living image of desire and union, both male and female” (Wonder Woman #70, 2019). They flirt with Diana, who seems not entirely uninterested but says in reference to Steve, “I’m already in love with someone else. A soldier.” Atlantiades, as a demigod, was surprised to be “rebuffed for a mere man” but accepted this and became a great ally of Diana’s. So while Diana can be viewed as a reader chooses, on-panel depictions of a same-sex romantic or sexual relationship for the character are, across her eighty years, miniscule to non-existent. Her relationships with other women, new or longstanding, are featured in some runs and jettisoned in others. She has addressed female characters as “sister” for decades, which can be read in a variety of ways as well.12 Carol Danvers, in her fifty years of comics, has not been depicted on-panel with a female partner. Some have read her as queer in the film due to her loving relationship with Maria Rambeau, and Maria’s daughter Monica stating that they are “family.” Some have read her as queer in comics due to her loving relationship with Jessica Drew/ Spider-Woman. Before her relaunch she was paired briefly with a few men, most notably Air Force Special Operations man Michael Rossi, and since that point has been mostly coupled with Lt. Col. James “Rhodey” Rhodes, aka War Machine or Iron Patriot. While this conforms to a heteronormative frame, they are also an interracial couple, which goes uncommented on by the other characters. In contrast to Wonder Woman’s one interracial relationship from the early 2000s, at which time writer Phil Jimenez got negative letters about his pairing Diana with U.N.-worker Trevor Barnes, the Carol-Rhodey relationship seems to have been taken in stride by fans, perhaps because of increased societal acceptance of such relationships, perhaps because they are both military, and/or perhaps because Rhodey is a familiar and prominent character in comics and films. Diana and Carol, on the whole, have not been sexualized or stereotyped or sidelined in their 2010s comics, although there have been exceptions in some Wonder Woman stories. Their romantic lives are basically nonqueer, and they are relationships of respect and care more

20 Introduction nuanced than in their earlier stories. These trends, given the history of female superheroes’ representations, are not to be taken for granted. The moves toward the diversification of characters in the 2000s and the 2010s noted earlier has been carried through the supporting casts for both characters as well, which is analyzed in more detail in the chapters following this introduction. Both of the characters also remain privileged white women who are further centered by their leadership of diverse teams and thereby shore up a racialized status quo while softening their own gendered challenges to power. They tend to use force in ways that position male superhero characters’ hypermasculine responses to threats as a norm. They threaten to question broader structures, but mostly react to and temporarily quash individualized threats from individual villains. All of this embodies postfeminist and postrace sensibilities, or a more neoliberal and white feminism, that celebrate a singular women’s empowerment through self-actualization, as she works in service of the status quo and coexists with other gendered, raced, classed, etc., structural inequalities. At the same time, such characters embody feminist, anti-racist, and queer potential, in their being centered in non-sexualized and nonstereotypical ways in their own stories, in their building of communities of marginalized people as their allies, in their standing up for the vulnerable and against injustices. These are great strides for these characters, but producers of superhero media have far to go to reach parity in their qualitative and quantitative treatment of female superheroes as opposed to male superheroes.

Superwomen as soldiers The next three chapters focus on Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel as both feminist and military women, and the complexities that such an identity engenders. The frst explores gender and violence as portrayed in texts and flms that can be considered militainment, and how such violence might be produced and received diferently when it is employed by a female as opposed to a male military protagonist. The second examines portrayals of military service in the comics and flms in terms of their focus on self-empowerment along with teamwork, the particular diverse teams with which Diana and Carol work, and the implications of increasing diversity in institutions. The third analyzes the ways in which enemy leaders, armies, and terrorists are generally othered in order to reduce sympathy for them, and also notes the ways in which in multiple stories, vulnerable refugees are othered as well,

Introduction

21

even as they are protected by the superheroes. These chapters are followed by a conclusion that refects on the promise and peril of these elements of the portrayals of women superhero soldiers.

Notes 1 See, for instance, Brown (2011, 2015), Cocca (2016), Madrid (2009), Enloe (2000), Knopf (2015, 2016), Mesok (2016), Runck (2006), Tasker (2011). 2 I understand feminism as a movement for equality and equity, and against systemic inequalities, inequities, and oppressions, with numerous internal debates as to how to do so, and so, numerous types of feminism. Liberal feminism describes a standpoint that advocates for equal access and opportunities in terms of institutions and rights and laws. But in varying degrees it has tended to privilege the perspective of white, nonqueer, nondisabled, middle-class, professional women of the Global North, and it has also tended to promote and evaluate individual women’s inclusion in formerly all-male institutions as marks of success. Because of this, more intersectional feminists, who take into account the multiplicative efects of various types of oppressions, may label liberal feminism as white feminism, hegemonic feminism, and Western feminism. These terms have different emphases, are not entirely interchangeable, and are more favored in certain disciplines than others. See, e.g., Abu-Lughod (2013), Chowdhury and Philipose (2016), Cohen (2010), Crenshaw (2011, 2013), Eisenstein (2017), Enloe (2000, 2004), hooks (2013), Kanai (2020), Mohanty (2003, 2013), Riley, Mohanty, and Pratt (2008), Shehabuddin (2011), Spivak (1985). 3 I employ the term postfeminist not as referring to a type of feminism (although part of its appeal lies in its “entanglement” with some feminist discourses) but rather as parallel to the term postracialist, or postrace. These are sensibilities that reject the necessity of movements for collective liberation and the necessity of a more robust welfare state because they claim that movements for equality have done enough, such that we have progressed to the point of living in a merit-based, gender-blind, colorblind world. These sensibilities operate in the context of neoliberalism, an ideology sufused in market-based discourses of responsibility and choice, in which we are all entrepreneurial individuals responsible for our own successes or failures, and to assert otherwise is an uppity and unfair imposition on those who are successful. Postfeminist and postrace sensibilities intersect in some ways with what have been labeled neoliberal, popular, celebrity, corporate, and faux feminisms, which have some commonalities with the terms mentioned in note 2: white feminism, hegemonic feminism, and Western feminism. Namely, that they center the most privileged women and tout their successes in ways that not only may harm the less privileged, but also detract from further collective organizing for those less privileged. See Banet-Weiser (2018), Banet-Weiser, Gill, and Rottenberg (2019), Butler (2013), Crenshaw (2011), Gill (2007, 2016, 2017), Gill and Scharf (2011), Gray (2013), hooks (2013), McRobbie (2004, 2009,

22

4 5

6

7 8

9 10

Introduction 2011), Mohanty (2013), Mukherjee (2016), Mukherjee, Banet-Weiser, and Gray (2019), Negra and Hamad (forthcoming), Negra and Tasker (2007), Renninger (2018), Rottenberg (2014, 2017), Springer (2007). See, for instance, Enloe (2000, 2004), Monnet (2018), Pardy (2016), Shigematsu, Bhagwati, and Paintedcrow (2008), Stahl (2009), Thomas (2009). Neoliberals employ language such as equal opportunity, freedom, personal responsibility, choice, hard work, and merit. Such language is anything but neutral, as its deployment is grounded in backlash to civil rights movements that expanded not only awareness but also oversight of discriminatory institutions. Neoliberals seek to free these institutions and privileged individuals from government attempts to engender equity, describing those attempts as unfair and harmful to blameless, successful (white, cisgender, male) people. Support for such freedom from government comes not only from elites, but also from struggling people looking for success through their own individual work and choices, and from those who fnd resonant racialized, xenophobic, sexist explanations for their precarity. In privatizing risk through deregulation, in exhortations to individual responsibility for oneself and family, and in eroding support for the public redress of injustices by blaming marginalized individuals for their struggles, neoliberal discourses and policies mask structural inequalities and reinscribe hierarchies of gender, race, class, sexuality, ethnicity, nationality, religion, and disability. In buttressing these hierarchies, neoliberalism dovetails with neoconservatism and is in return supported by neoconservative praise of tradition and its sanctioning of authoritarian uses of force domestically and internationally. See Brown (2005, 2006, 2019), Duggan (2003, 2019), Hall (2011), Harvey (2005), Mohanty (2013). I employ postcolonial, queer, and critical race theories, in conjunction with socialist feminisms, feminist disability theories, feminist international relations theories, and feminist security studies because I seek to foreground transcultural and transnational feminist solidarities, rather than assume a notion of sisterhood that elides diferences and decontextualizes specifcities of historical experiences. I do not, within, make major distinctions between comics and flms but treat them as distinct texts with the same, albeit fexible characters. This history of female superheroes is covered in much greater detail in Cocca (2016). See also Cocca (2020). Percentages computed by the author from Marvel and DC January 2020 solicits: 21 out of 140 comics star a female character, and 23 out of 140 with a female writer or artist. Almost half of those twenty-three were written by just three women. Six shows out of thirty-eight on TV and nine flms out of ffty star female characters. Adding in media with ensemble casts that have roughly equal numbers of women, the percentages become approximately 20% for comics, 30% for TV, and 25% for flms. Comics numbers from 2015, 2010, and 2005 were compiled from www.comichron.com; see Cocca (2016). TV and flm numbers compiled from various websites. Percentages computed by the author. There is a much more detailed history of these two characters from their origins to the early 2010s in Cocca (2016).

Introduction

23

11 These relaunches, particularly fan reactions to them, are covered in more detail in Cocca (2016). 12 While Wonder Woman has always referred to Amazons and other women she encounters as “sisters,” it is a fraught word for feminists. In calls for sisterhood from the 1970s, and particularly for sisterhood to be global, historical contexts and intersectionalities were often elided in favor of privileging white, Western/Global Northern, middle-class, and professional concerns. The concept of “solidarity” rather than that of “sisterhood” tends to be more embraced as requiring listening about and across diferences and forging alliances based on ending sexist oppressions as they intersect with imperialism, racism, homophobia, xenophobia, and ableism.

1

Gender, violence, and militainment

This chapter discusses the subversiveness of feminist characters such as Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel using violence that has much more often been the province of male characters, and the ways in which that subversiveness might be eased for those uncomfortable with seeing women use violence. It then discusses in more depth one of those means—surrounding the female fgure with military aesthetics including settings, weaponry, and personnel—and how the actors playing the characters on flm also contributed to alleviating such discomfort. All of this contributes to the characters’ popularity and the flms’ recordbreaking fnancial success, as their simultaneous feminism and militarism invites multiple readings of the politics of the comics and flms’ texts and paratexts.

Gender and violence in the superhero genre Despite cultural narratives of gender that essentialize women as more peaceful than men, or qualify women’s use of violence as deviant or as “personal rather than political,” women have indeed engaged in political violence around the world, particularly anti-colonial violence (Sjoberg 2015: 443). As Enloe has noted, “Most feminists have never said that women can’t be militaristic” (2004: 133). Whether in the name of defense, pre-emption, retribution, protection, democratization, justice, or imperialism, military women and superhero women almost by defnition use violence and the threat of violence to force others to submit. The superhero genre was born in resistance to fascism in the 1930s and yet retains fascist aesthetics for its protagonists, as superheroes tend to be “violently patriotic” in their use of “anti-democratic authoritarian violence” (Gavaler 2016: 82, 85n1). Indeed, “it remains rare for a superhero comic published by Marvel or DC not to feature at

Gender, violence, and militainment

25

least one fight, or for the resolution of their stories not to involve violence” (Wanner 2016: 177; also Davis 2018: 23). It is a “romanticized vigilantism” and a “romanticized authoritarianism” that is presented as “justified reprisal against immoral behavior,” and it therefore serves “the redemptive function of retributive violence” (Gavaler 2018: 25, 81, 124; Coulthard 2007: 165; see also Brown 2017: 74). Such characters, like in the war and Western genres, “maintain and reinforce specific patterns of masculinity, American exceptionalism, and the notion that violence solves problems” (Kvaran 2017: 222). Most of these media have historically starred white, cisgender, heterosexual men, and through repetition have collapsed these four categories into a singular demographic profile and imbued it with the attributes of “masculine,” “American,” “exceptional,” and “violent.” If male superheroes are exceptional figures, then female superheroes are even more so. Their small numbers reveal cultural concerns about them, why they are sometimes described by a vocal minority in unflattering and even misogynistic ways, and why they carry tremendous weight as representing all women. The same can be said of women in the military. Indeed, female characters star in about 15–18% of superhero media, and females make up about 16–18% of U.S. military personnel.1 Such individuals, who triumph over adversity with their strength and with righteousness, can be very attractive, particularly for those who have been marginalized. The use of violence by female characters onscreen has been written about mostly in terms of its subversiveness of dominant cultural narratives of gender, as well as in terms of viewers’ pleasure and feelings of empowerment. Jeffrey Brown has written that, “Everyone loves an underdog, and to see macho men or superior forces beaten to a pulp by an unassuming character,” particularly a young woman, “is vicariously satisfying” (2017: 217). These works show viewers that “women are capable of being their own heroes” (Brown 2017: 11; see also Cocca 2016; Inness 2004). Tung recounts the reactions of her students watching action films starring women, such as “‘I felt powerful watching those women’” and “‘I don’t really see it as violence . . . I like their . . . power’” (2004: 103). McCaughey writes of her own exhilaration watching the character Sarah Connor in Terminator 2: “I realized that men must feel this way after seeing movies—all the time. . . . I could understand the power of seeing one’s sex made heroic on-screen and wanted to feel that way more often” (quoted in Stuller 2010: 29). Ginn says of Marvel’s Black Widow, Gamora, Melinda May, and Peggy Carter that “these characters live in worlds where women do not have to be afraid of men, where women have agency, where women have

26 Gender, violence, and militainment power. And that gives hope to us all” (2017: 4). Mainstream media articles, blogs, Instagrams, and tweets recounted stories of women crying while watching the Wonder Woman movie. They describe being overcome by seeing themselves as potentially powerful through the strength and prowess of the diverse Amazons (many of whom were played by professional athletes and stuntwomen), and by Wonder Woman’s run across No Man’s Land to liberate a Belgian village. For those for whom the subversion of gendered norms is discomfiting, the palatability or popularity of female violence may lie in conforming such characters to raced and classed notions of gender performance, in presenting them as similar to male characters and as seemingly naturalized to such behavior because they are born to it, and in surrounding them with familiar military tropes and trappings. Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel’s 2010s stories contain each of these elements. First, most female action heroes and female superheroes, like Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel, are white, conventionally attractive, and almost always portrayed as heterosexual—not women of color, not working-class, not impoverished, not disabled, not queer, not transgender. In this way, female violence is “entwined with discourses of idealized feminine whiteness” (Coulthard 2007: 158; see also Brown 2017; Cocca 2016; Helford 2002; Inness 2004; Springer 2007; Tasker and Negra 2007; Tung 2004). This type of protagonist may not travel so easily across racial boundaries in that a “fierce kickass black woman is more likely read as hyperaggressive, wild, untamable, and vicious rather than as an admirable warrior woman breaking down age-old stereotypes that white women invoke” (Tung 2004: 110, 111; see also Browder 2006; Brown 2015; Helford 2002; Langsdale 2020). Perhaps representations of black female anger are eased for apprehensive white audiences when such roles are supporting rather than starring, or when such characters have subjected themselves to the discipline of the military, as with Maria Rambeau in the Captain Marvel movie and the now African American Etta Candy in Wonder Woman comics (see., e.g., Tasker 2011: 108, 117). These two are supportive sidekicks to the white heroines and can be seen as fulfilling a “black best friend” trope, but they are also fully formed characters working in the U.S. military who use violence to protect their families, their colleagues, their country.2 A second component to the acceptability of female violence may lie in presenting characters not only as increasingly similar to male superheroes, but also as naturalized to such behavior because via their 2010s revised origin stories they are “born” to it through an othered

Gender, violence, and militainment

27

and exoticized monoculture—Captain Marvel as Kree, and Wonder Woman as Greek god. These moves explain and soften their exceptionality in the male-dominated superhero universe. Captain Marvel has become akin to Captain America in that both now wear a fullcoverage military “dress blues” uniform with red accents and a star in the middle of the chest, like the star painted on all U.S. military vehicles and used in its ads and merchandise. Both have the honorific of Captain and both are called “Cap” by their allies. They sometimes call each other “Army” and “Air Force” in ways that reinforce their military attachments, and their individual stubbornness and strength of character show in their unwillingness to stay down in a fight: one says “I could do this all day” and the other thinks “Always get up.” She has also become increasingly akin to Iron Man Tony Stark, in terms of their confidence bordering on arrogance, hotheadedness, diffusion of tension with humor, closeness to Lt. Col. James “Rhodey” Rhodes, affiliations with the U.S. government and military, living with alcoholism, ability to fly, and shooting beams of light/energy out of their hands. Wonder Woman, over time and with her revised origin, is now much more like both Superman and Thor. While at her origin she was strong and could run fast and jump far due to her Amazon training, her powers were increased so much over time that, akin to Superman, she now flies and is so strong as to seem undefeatable except by aliens or gods. Her new origin explains these powers in a way that her gender and training apparently could not: she is now the demi-god daughter of the consistently violent and occasionally peacemaking king of the gods, Zeus. Like him and like Thor, she can call lightning to her and then redirect it at others. While Thor carries a hammer and axe, Wonder Woman now carries a sword and uses her newly enlarged bracers as her second weapon. These female characters’ powers and their levels of violence are then rationalized as they are not only framed as similar to popular male characters, but also as they are merely like others of their non-human races. With the former, they have entered the institution of male superheroes and conformed to it; with the latter, their abilities and behavior are explained through their genetics. The two do usually approach the use of violence differently. Captain Marvel is prone to anger and impatience, and tends to use violence first and ask questions later. Iron Man describes her as liking “Star Wars and punching things” (DeConnick and D. Lopez 2015, Captain Marvel [hereafter CM] #1). She agrees, “It’s not that I’m a violent person. It’s just that some things really, really need punching. And I am very good at punching things” (M. Fazekas and T. Butters, and

28 Gender, violence, and militainment K. Anka 2016, CM #1). But after her origin was rewritten, her Kree mother explains to her, “We taught you to love, not to fight. To use your heart, not your fists. . . . But in my heart I knew we were keeping you from who you really were, and I hated it.” Further, she says, “What humans see as Kree powers are just our biological adaptations to a life of combat” (M. Stohl and C. Pacheco 2019, Life of Captain Marvel [hereafter LoCM] #4). This Carol loves stars and wars and is prone to anger and violence because she was born that way; this is who she “really” is, given her biology. This subverts the gendered association of violence as constructed as natural only to male bodies, but at the same time explains away her choosing to use violence through her female body. A “life of combat” and her Air Force training contain at least somewhat her impulsiveness and potential disorderliness. Wonder Woman, from her origin eighty years ago, has almost always been framed as using violence only as a last resort: a unique superhero whose power was rooted in her ability to stop violence through compassion rather than through further violence. This characterization, in line with gender stereotypes but also with a feminist approach to security that promotes dialogue, empathy, subjectivity, and empowerment (Sjoberg 2008: 7, 8) was employed by writers Rucka, Fontana, Orlando, and Wilson in their 2010s comics. The idea of her and the Amazons using diplomacy first and violence only last—the opposite of Captain Marvel—was summarized famously by writer Gail Simone: “We have a saying, my people. Don’t kill if you can wound, don’t wound if you can subdue, don’t subdue if you can pacify, and don’t raise your hand at all until you’ve first extended it” (2008, Wonder Woman [hereafter WW] #25). Rucka writes her as shielding civilians while being asked why she will not allow the men who threatened those civilians to be killed. Because, she says, “We do not kill when we can subdue” (G. Rucka and B. Evely 2017, WW #20; see also #12). Similarly, Wilson writes General Antiope as cautioning her Amazon troops, “Remember our training—do not kill if you can wound, do not wound if you can subdue!” (G. Wilson and C. Nord 2019, WW #75). In stories by Rucka, Wilson, and Orlando, Diana extends a hand to villains Veronica Cale, Barbara Ann Minerva/Cheetah, and Mayfly even as they work against her and physically fight her repeatedly. Her Amazon military training, and later her U.S. military training, keep her potentially unruly woman’s violence in check. However, around half of Wonder Woman issues in the 2010s, by writers Azzarello, Finch, and Robinson, have shown her using violence much more readily, even as they nodded to her as being motivated by love or wanting to end conflict. This follows from her rewritten

Gender, violence, and militainment

29