The Gray Zone: Sovereignty, Human Smuggling, and Undercover Police Investigation in Europe 9781503607668

Based on rare, in-depth fieldwork among an undercover police investigative team working in a southern EU maritime state,

922 47 2MB

English Pages 240 Year 2019

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Gregory Feldman

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

The Gray Zone

Anthropology of Policy

Cris Shore and Susan Wright, editors

The Gray Zone

Sovereignty, Human Smuggling, and Undercover Police Investigation in Europe

Gregory Feldman

Stanford University Press Stanford, California

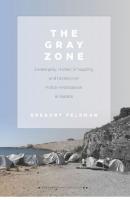

Stanford University Press Stanford, California ©2019 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Feldman, Gregory, author. Title: The gray zone : sovereignty, human smuggling, and undercover police investigation in Europe / Gregory Feldman. Other titles: Anthropology of policy (Stanford, Calif.) Description: Stanford, California : Stanford University Press, 2019. | Series: Anthropology of policy | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018027720 | ISBN 9780804799225 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781503607651 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Human smuggling—European Union countries—Prevention. | Human trafficking—European Union countries—Prevention. | Undercover operations— Moral and ethical aspects—European Union countries. | Police ethics—European Union countries. | Sovereignty—Moral and ethical aspects. Classification: LCC JV7590 .F454 2018 | DDC 363.25/551094—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018027720 ISBN 978-1-5036-0766-8 (electronic) Typeset by Westchester Publishing Services in 10.5/15 Brill Cover photo: Refugee tents on a beach in the Mediterranean. IRIN | Ylenia Gostoli Cover design: Rob Ehle

For John Harriss and Alec Dawson Witty and compassionate colleagues who understand what the job is about For Anna Bailey, Julia Edwards, and Anna Labadze Women of principle, w omen of action For 119 students of International Studies at Simon Fraser University For signing a petition and saying what they think

This page intentionally left blank

The concept of life is given its due only if everything that has a history of its own, and is not merely the setting for history, is credited with life. Walter Benjamin, Illuminations: Essays and Reflections

This page intentionally left blank

Contents

Preface xi The Argument

xvii

Acknowledgments

xix

Introduction: Sovereignties and Their Gray Zones

1

1

The Ambiguity of Truth: The Ephemeral Limits of Security Apparatuses 41

2

Identity and the Investigative Team: Violence, Sovereignty, and Personhood

3 4

The Thinness of Secrecy

107

Sovereign Actions on a Global Stage

137

Conclusion: Alternatives Within: The Appearance of the Second Sovereign Form Despite the First

179

71

References 199 Index 213

This page intentionally left blank

Preface I was always defined as too erudite and philosophical, too difficult. . . . It’s only publishers and some journalists who believe that p eople want s imple t hings. People are tired of simple things. They want to be challenged. Umberto Eco (1932–2016)1

“I trusted you with my gun,” David replied with a mixture of disgust and offense. And indeed he did. Earlier that day, I drove north out of the city with him and four of his colleagues—Brian, Vincent, John, and Frank. They comprise five out of seven members of an undercover investigative team specializing in transnational crime, which usually involves human trafficking and smuggling, along with prostitution, burglary, begging, and pickpocketing. Based in a southern, maritime European Union (EU) member state, they seek not to arrest street-level players. Instead, their investigations hone in on t hose controlling the local operations, who are invariably tied into wider networks operating in the margins, gaps, and ambiguous spaces of the EU’s security-migration apparatus. That afternoon, they took me to a shooting range where they could refresh their skills and teach me how to fire a pistol. The range amounted to nothing more than an expanse of hilly terrain with sandy cliffs to catch stray bullets. The team carries Glocks, a well- known Austrian handgun and the first ergonomically designed sidearm. David provided me with thorough instructions. First, with the pistol’s bullets removed, he explained its design: the sensitivity of the trigger; the catch to release the magazine; the slide giving access to the barrel; and the sights through which to align the barrel with the target. He then specified the two cardinal rules of h andling a gun and made me repeat them. I reiterated dutifully, “One, keep your index fin ger off the trigger u nless you are ready to fire. Until then, it should be extended straight forward alongside the barrel. Two, always keep the gun pointed in a safe direction when it is not in use.” 1. Stephen Moss, “Umberto Eco: The G2 Interview,” Guardian (UK), November 27, 2011. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/nov/27/umberto-eco-people-tired-simple -things. Last accessed May 25, 2016. xi

xii Preface

fter he had coached me through a few rounds without bullets, David then A walked me to a spot twenty feet before the target so that I could fire a gun for the first time in my life. I learned that when shooting, one must slightly bend the knees to stabilize the body, like a shock absorber, from the gun’s discharge. The weak hand steadies the strong hand holding the grip, but with strong thumb on top of the weak thumb. Align the front sight notch so that it appears between the rear sight’s two posts and so brings the target into the line of fire. Gently press the index finger against the trigger: not too strongly and not too weakly. David stood behind my left shoulder. “Relax, Greg. Just breathe.” BANG! Even a relatively quiet pistol startles a first-time shooter, but one regroups quickly with the coach’s encouragement. “Good. Just relax, breathe, and shoot again, Greg.” BANG! And on I went u ntil the fifteen bullets in the magazine had buried themselves in the sandbank behind the target. David continued his instruction. A fter firing the final bullet, first, press the catch to release the magazine from the grip; second, pull the slide back to expose the inside of the barrel, verifying that it is empty; and third, pull the trigger while pointing the gun in a safe direction so that it releases its cocked pressure. David remained unarmed as he instructed me on how to fire his gun. While Brian, Frank, and John milled about, Vincent stood fifteen feet diagonally behind my right shoulder, just outside my peripheral vision. His Glock remained in its holster, perched on his b elt. He kept his arms folded as he stood on guard, ready to defend David should I have gone off the deep end. Cops back up their colleagues much like one chess piece protects the square of another that has advanced toward the opponent’s line. During the car ride to and from the shooting range, they had been telling me stories about breaking laws during countless investigations. I had heard many such stories already during the previous two weeks when I first began fieldwork with them: illegal entries, illegal detentions, illegally accessing information, blackmail, extortion, and so on. Two weeks proves a long time in this type of ethnographic fieldwork if measured in a ctual contact hours. The team spends most of their time on surveillance operations, which last anywhere from three to twelve hours straight. On balance, these operations are excruciatingly boring because their suspects, like most people, do not really move around that much. Most of the operation involves sitting in a car or a café while waiting for suspects to go somewhere to meet someone. So, the hours of downtime are spent talking . . .

Preface xiii

and talking . . . and talking. The team keeps no secrets from each other, and I had very few left in me by the end of fieldwork. Yet, before then, I was unsure of the amount of skepticism I could show with my questions. That evening at dinner, Brian spoke of a plan, to gain them access to a Chinese-run brothel, that seemed both elaborate and harebrained to me. These brothels are particularly difficult to investigate b ecause they only cater to Chinese clients. Such challenges push the team to the limits of their creative powers, and their l egal ones. Yet, a fter Brian’s idea, I had finally heard one story too many. I yielded to my skeptical impulse, feeling confident that the question I had to ask would neither offend them nor cost me the unusual access they had granted me. In any case, I would have been academically irresponsible to not press them on the matter. I asked incredulously, “How do I know these stories aren’t all bullshit?” To be fair, the stories they tell can hardly be made up. Truth is stranger than fiction, as the saying goes. But enough was enough. Brian and Vincent belted out a hearty laugh at the deadpan delivery of my question. David took it to heart. “Greg, I trusted you with my gun.” Yes, he had, and, unarmed himself, he had taught me how to deliver a fatal gunshot should I ever need to. I could have made him my target. My incredulity offended him: if he trusted me enough to hand over his gun, then why couldn’t I trust what he said? Strictly speaking, he had put his life in my hands, and I gave him skepticism in return. I do not expect this vignette to compel the reader to believe that the team never stretched the truth, or that they never dramatized to impress, or make fun of, the naïve ethnographer. I do expect, however, that this ethnography be held to the same standard as any other. It is tempting to think that an accurate under standing of p eople’s daily routines is harder to obtain when they work clandestinely for the state. However, ethnographic interlocutors of all backgrounds shield, conceal, and partially reveal themselves and their knowledge. Some have secrets to keep; others are more forthcoming. The ethnographer tries to uncover as full an understanding as possible. The bar to cross, basically, is whether the written representation of one’s interlocutors rings true to anyone generally familiar with the issues at hand. Does the writing convey that the ethnographer knows what s/he is talking about? Ethnographers cannot verify each other’s fieldwork as laboratory scientists verify each other’s experiments through replication in contrived conditions. In this regard, the point I wish to make with

xiv Preface

the opening vignette is that, I believe, the bond I established with the team after more than six hundred hours in direct, engaged, face-to-face contact with them (not just hanging out in the general vicinity), plus dozens more hours in various other forms of communication, was sufficiently strong for me to understand what their work is about and how they themselves approach it. I participated in scores of their surveillance runs, ate long lunches with them on a daily basis, socialized with them outside of working hours, visited some of their homes, studied their investigative tactics, interviewed and engaged others in adjacent units in the Immigration Service, and examined a dozen of their open and closed cases. I interviewed them formally and informally, and some of their wives too, and ethnographically studied with them parts of the city and surrounding country where their cases often lead. Another question also comes up, again one that any ethnographer would have to answer: Why did t hese people want me around in the first place? In my case, this question was usually asked as a prelude to the question of whether these investigators hid their real dirty work or only showed me a sanitized version of what they do. Yet, while one never knows what one does not know, the question misses a more pressing point: that my continual presence posed a g reat risk to them. An awkward foreigner is well capable of screwing up a street operation that requires subtlety and discretion. An outsider can also, accidentally or not, go public with information that could deeply embarrass the team and land them in political or legal trouble. The associate director to whom they report, one of four in the national Immigration Service, clarified to me over a two-hour lunch that “no journalist would ever get this access” for fear of cherry- picked stories, unfair biases, and sensationalized headlines. While my presence was their risk, I had no material or political benefit to offer them. They had no professional interest in my research, and t here is nothing I could do to advance or protect their careers. They had no reason to open their professional world to me only to conceal some other “double secret” component of it from my view. Nevertheless, they had one understandable incentive, familiar to ethnographers, which convinced them to bring me on board a fter Brian, upon my request, suggested it to them in spring 2012. (I first met Brian in 2008, during fieldwork for The Migration Apparatus [G. Feldman 2012], and we maintained a correspondence from then on.) It was David again who captured the sentiment. When I asked during my first lunch with them why they had agreed to my project, he replied, “Greg, we’re glad y ou’re interested. This is like therapy for us. We have no

Preface xv

one to talk to but each other and our wives . . . and our wives are sick of hearing it!” Genuine interest, however, is not flattery or callow admiration. Good ethnographers are more than passive stenographers of what they are told and what they see. On this point, Clifford Geertz argued that a compelling ethnography “does not rest on its author’s ability to capture primitive facts in faraway places . . . but . . . to clarify what goes on in such places” (1973: 16). He thought that the ethnographer should not copy raw social discourse, but rather “only that small part of it which our informants can lead us into understanding” (19–20). To get there, ethnographers must ask questions; they must present dif ferent perspectives to force their interlocutors to clarify their own. Per Umberto Eco’s point in the epigraph, I suspect that the team, like p eople in general, want to be challenged with tough, but fair, questions b ecause the challenge draws more insight out of them. They risked bringing me on board b ecause they saw just such a chance. Such chances allow us to speak, clarify, and articulate our own views on the world, and, if we stay open-minded, then we get to enlarge those views through the glorious mess of verbal exchange. We distinguish ourselves through speech, but speaking implies an audience that listens critically. Speech becomes navel- gazing without an audience, and, without a critical one, it amounts to nothing more than an echo chamber, mere navel-gazing in a social setting. A critical audience grants the speaker a worldly reality—a presence in the company of others who are different but willing to fairly examine difference. Through our exchanges in a world of o thers—whom we do not Other—we obtain “being,” that thrill of knowing that the space we share with others depends to some extent on our own particul ar presence, just as our being depends on it. Without this engagement with o thers, we are condemned to our private lives, comfortable though they might be, but certainly isolated. Fieldwork with the team, then, consisted of an ongoing debate and discussion prompted by what Heyman (2003) calls “counterpart ideals”—that is, alternative moral claims in fields of structural power that undercut the position of authority that a given actor occupies. This approach pushed them to both complicate and refine the meaning they ascribe to the sovereign actions they take when imposing themselves on the lives of others, to steal the title from a film about the former East Germany’s secret police. To create a situation in which one’s interlocutors do not feel threatened by the exchange, but rather come to thrive on it, the ethnographer must be willing

xvi Preface

to learn what they do and to hear why they choose to do it the way that they do. The ethnographer must not sacrifice his/her ethical judgment, but neither should s/he rush to judgment about theirs. If the interlocutors are confident that the ethnographer’s judgments are reached in measured steps, then they will enjoy the differences of opinion that emerge. To be sure, had it just been the flattery of my attention, then the team would have grown bored with me before long. The callow admirer has nothing to offer on his own and ultimately cannot stand eye-to-eye with the admired. Had I been unreflectively antagonistic like an overeager journalist, then they would have grown defensive and dismissive. Had I mirrored them and simply tried to be like them to win their ac ceptance, they would have disparaged me as a pretender. Instead, just as they expect from each other, they expected me to be myself and to ask anything I wished as long as I was willing to listen and watch before I judged. In turn, I had to answer their questions and accept their challenges too. Most of these involved their critiques of North American political correctness, which they perceived to inform my own outlook. It must certainly sound like a cliché to hear that I grew tremendously with this project. Yet I did. I do not agree with many opinions the team members expressed, and I question the ethics of several actions they took. However, it is no exaggeration to report that their flexibility of mind, allowing them to comprehend the plurality of standpoints tied to a common situation, like a crime, exceeds that of anyone I have known.

The Argument

eople desire to constitute sovereign spaces through which they come to life as P particular persons. However, such spaces, identified here as the second sovereign form, appear in the shadows of the nation-state, identified as the first sovereign form. These sovereign forms are qualitatively different even if not fully disentangled. The first sovereign form depends upon a vertical arrangement that atomizes and abstracts subjects into equal, homogeneous entities. It thus silences the particular subject by emphasizing a capacity of the mind that operates generically in everyone: the capacity to make abstract, technical judgments through the mind’s faculty of cognition. The second sovereign form depends upon a horizontal arrangement in which p eople appear as different but equal subjects. It empowers the particular person as it requires ethical judgments based on a different capacity of the mind stimulated by the actor’s unique standpoint with respect to o thers. Through the faculty of thinking, we judge situations by examining o thers’ standpoints to decide upon joint actions, which satisfy our consciences. Particular subjects mutually constitute each other, and the sovereign space between them, through t hose joint actions. Each form differently conditions how sovereign agents will conduct themselves in gray zones, for better or worse, where law and custom dissipate and opportunities arise to act without precedent. As the first sovereign form is premised upon p eople as atomized, abstract objects, those agents are more likely to treat Others as stereotyped, voiceless objects. As the second sovereign form is premised upon p eople as mutually constituting subjects, sovereign agents are more likely to treat others as full persons, even when acting against their interests. This argument is demonstrated through an ethnography of an undercover police investigative team in a southern, maritime European Union member

xvii

xviii

The Argument

state. This team focuses on transnational crime, primarily h uman trafficking and smuggling. They occupy a peculiar place in the larger security apparatus from which they can escape the top-down vertical imperatives of first sovereign form and, however fleetingly, conduct action in line with the second sovereign form.

Acknowledgments

This book would not have been possible without the active support and interest of the members of the undercover investigative team themselves. My thanks and gratitude go directly to them. I hope they find the book a thoughtful and thought-provoking assessment of what they do. I also thank Canada’s Social Science and Humanities Research Council for funding the project through their Insight Grant program. Much of Chapter 1 draws on material published as G. Feldman (2016), “ ‘With My Head on the Pillow’: Sovereignty, Ethics, and Evil among Undercover Police Investigators,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 58 (2), 491–518, published by Cambridge University Press, reproduced with permission. Several students of international studies provided invaluable research assistance throughout the course of the project. I am grateful to Melissa Gregg, Jenna Dixon, Nick Palaj, Sara Sim, and Ogake Angwenyi for their time and capability. Julia Edwards was especially helpful in proofreading drafts of the chapters, combing through various literatures, and ferreting out information from obscure sources. Several colleagues offered important insights that helped me develop, clarify, and refine the book’s empirical and theoretical arguments. They include Samir Gandesha, Elizabeth Cooper, John Harriss, Alec Dawson, Joe Heyman, Naor Ben-Yehoyada, Michael Herzfeld, Andrew Shryock, Manuela Bojadzijev, and William Walters. I thank Merje Kuus for her help with the logistical responsibilities of conducting fieldwork abroad. The ideas conveyed in this book w ere developed and refined through several invited lectures, workshops, and conference presentations. I am grateful to Manuela Bojadzijev for her invitation to present at the Institute for European Ethnology at Humboldt University, Berlin, in 2015. The same gratitude goes to Samir Gandesha’s invitation to present at the Institute for Humanities at Simon Fraser University shortly thereafter. I thank Keally McBride for her 2016 invitation to xix

xx

Acknowledgments

speak at the University of San Francisco. Rohit Jain’s invitation to deliver the keynote address at the 2016 annual conference of Switzerland’s National Center of Competence in Research—The Migration-Mobility Nexus at the University of Neuchâtel came as a great honor. I benefitted tremendously from the side conversations during my stay. I am similarly grateful to Thomas Bellinck, theater director and documentarian, for his use of my first book, The Migration Apparatus, in his musical production Simple as ABC #2: Keep Calm & Validate, and for his invitation to speak at the 2017 Kunstenfestivaldesarts in Brussels. The Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Criminology at the University of Windsor, Ontario, provided me with a rich forum to present this research t oward the final days of fieldwork. I thank Nick Harney and Tanya Basok, in particular, for their engagement and interest. I also thank Maria Stoilkova and Esther Romeyn for bringing me to the University of Florida’s Center for European Studies’s mini- conference “The Provocations of Contemporary Refugee Migration” in 2017. Thanks to Maria, Esther, and the other participants, this event left me with an overload of issues to consider when working out this book’s argument. I also benefitted from colleagues on panels at conferences of the American Anthropological Association, the European Association of Social Anthropologist, and Peace and Conflict Studies in Anthropology. I would like to thank several organizers for their administrative and intellectual input of various kinds. They include Monika Weissensteiner, Nils Zurawski, Mark Maguire, Catarina Frois, Erella Grassiani, Miia Halme-Tuomisaari, Joshua Clark, Winnie Lem, Pauline Gardiner Barber, Anja Kublitz, Lotte Buch Segal, Jeffrey Martin, Heath Cabot, and Sara Shneiderman. As ever, the editorial team at Stanford University Press have been both professional and personable while keeping the publication process on track. I extend particular thanks to Michelle Lipinski. My deep appreciation also goes to Cris Shore and Susan Wright, Anthropology of Policy series editors, and longtime friends and colleagues, who know how to constructively read other people’s drafts. I am grateful to Daniel Sentance and Brian Ostrander for their sharp and thoughtful copyediting. Finally, thank you to Rachel Moxham for meandering conversations and the possibilities that come with them.

The Gray Zone

This page intentionally left blank

Introduction

Sovereignties and Their Gray Zones To be or not to be. That is the question. We will be. Syrian refugee walking with thousands of other refugees from Budapest to the Austrian border, autumn 20151 Have you seen what they do? Go to their offices and see their forms. It changes you. It’s so boring. Legal shit and bureaucracy. Vincent

Two Forms of Sovereignty in Contrast States d on’t do things; p eople do. There are no such things as states, only actions conducted in their name by particular people. This book follows from that premise to better comprehend sovereign action and how it conditions our being in the world with others. The above two epigraphs showcase the very beginnings of two radically different sovereign forms that frame this book’s analysis of action and being human. For the refugee quoting Shakespeare, along with thousands more, the only way to be after Syria and the European Union marginalized them out of political space, for much different reasons, was to constitute a world for themselves through their own initiative. They acted in concert against the police authorities in Budapest’s Keleti train station by marching directly to the Austrian border. In so doing, they entered a gray zone when they stepped outside of Hungarian law to constitute their own sovereign space. The fleeting quality of their actions offers no counterpoint. True, they hardly destabilized the Hungarian state, and their joint action dissipated when they arrived in Austria, where they would be processed objectively through its asylum application system. Moreover, the Hungarian authorities ultimately provided buses to take them to Austria—it solved their problem and the refugees’ problem. Nevertheless, the point remains that politics and action came down to a single and highly personal question expressed through Shakespeare’s famous line: to be or not to be. That question can only be resolved in f avor of the former option through joint action. The particular person can only be in a world that is constituted with 1. J. Domokos, M. Khalili, R. Sprenger, and N. Payne-Frank, “We Walk Together: A Syrian Family’s Journey to the Heart of Europe,” Guardian (UK) video, 17:03, September 10, 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/world/video/2015/sep/10/we-walk-together-a-syrian -familys-journey-to-the-heart-of-europe-video (last viewed 14 October 2015). 1

2 Introduction

other particular persons. Since their actions transpired outside the scope of law—in a “gray zone”—it signified a foundational sovereign act, the birth of a new polity, issuing from their own thinking, judging, and action, that is, from their own partial and worldly positions. It neither descended upon them from an ideology’s transcendent heights nor was imposed on them by revolutionary elites or state bureaucrats. For Vincent, one of the seven investigative team members who operate on the street, the work of the office bureaucrat signifies a living death. He sees that figure personified in the desk investigators seated in the adjacent third floor office with whom his team must collaborate. The desk investigators’ job revolves around paperwork, process, and procedures all scripted in advance. While the state does not marginalize Vincent in nearly the same way as it does the Syrian refugees, his fear of the desk investigator’s life is that it will not allow him to be. The sovereign state reproduces itself, both through and despite the agents operating in its name. It carries on regardless of whether any given agent lives or dies. In contrast, the sovereign polity formed by the refugees lasted as long as they could act jointly to keep it alive. The result, however momentary, is the isomorphic appearance of sovereignty, personhood, and action. Vincent’s team contrasts their work against their counterparts in desk investigation because they seek the same experience of being as the Syrian refugees. Sovereign action is not abstract, though it is difficult to imagine a sovereign acting. At best, we can picture an agent of the sovereign, such as a police officer, tax collector, or passport control officer. Yet, if we can pinpoint only the sovereign’s agents, but not the sovereign itself, then we can ask—just as the team ask themselves—if those agents exist in the world as their own particular persons or as empty conduits for the implementation of sovereign authority. If the former, then the agents conscientiously agree with the sovereign; if the latter, then they lack a conscience insofar as they cannot distinguish their own viewpoint from the policy measures they must implement. If the agents disagree with the sovereign and still carry out the action, then they suffer from a crisis of conscience. In any case, the agents can only appear as themselves when in agreement with the sovereign; such agreement cannot happen in e very instance if we acknowledge that each person occupies a subjective standpoint. Yet the sovereign itself cannot be identified, much like the shadowy court that employed two nondescript agents to summon Josef K. in Kafka’s The Trial. As in real life, the

Sovereignties and Their Gray Zones 3

sovereign seems to be an intangible prime mover operating b ehind agents’ backs. However, reality is far more superficial or, at least, surficial. Rather than steering those agents from behind, the sovereign only emerges as the effect, not the cause, of what they do in its name. Overall, then, state sovereignty makes a strange demand on its agents: it asks them to deny themselves as a plurality of speaking subjects in order to create the illusion of its existence as a transcendent authority. This book asks if we—people as a plurality of beings—are limited to living together in this singular form of sovereignty, which apparently cannot survive without the subordination of the particular person. This requirement seems inhuman, literally, because at the end of the day each of us is nothing other than a particular person. This fact raises the question of whether another form of sovereignty exists, one that is premised upon, not against, plurality, which Hannah Arendt (1998: 7) identified as a basic h uman condition. To address this question, the book draws out two opposing forms of sovereignty to convey the radically different possibilities they offer for action, ethics, and being in a world of either Others (per the first sovereign form) or others (per the second sovereign form). I refer simply to these two sovereign modes throughout the book as, respectively, the first and the second sovereign forms. It should go without saying that the first and the second sovereign forms are not mutually exclusive, even though the first pushes the second into marginal spaces. To draw this analytical distinction is not to superimpose categories onto the ambiguities of daily life. Rather, these distinctions allow us to identify significant differences in h uman experience, differences that remain otherwise obscured and entangled in a complicated and messy empirical world. The investigative team’s research significance lies in the fact that while their work is highly conditioned by the usual demands of the traditional sovereign nation-state (the first sovereign form), they often conduct themselves on the street in a much different sovereign mode (the second sovereign form). The way they shift between, and act in, the two sovereign forms highlights how each so differently conditions the experience of being human. The first form, the modern state, dates back roughly to the seventeenth- century rise of the monarchical states of Europe. Short of warfare, it now flexes its muscle most mightily on the intertwined issues of migration and security. It is familiarly expressed at the controlled border crossing point, where travellers appeal to passport control officers for entry onto the state’s sovereign territory.

4 Introduction

The officer swipes the passport through a reader to see if any red flags are attached to the identity indicated in the name page. A few basic questions might be asked to determine if the traveller’s story matches the l egal criteria for entry. If not, then the officer sends the individual to a separate room for a second line of questioning. Strikingly, the w hole process requires precious little from the officers despite their making a decision that can profoundly affect the traveller’s journey, if not life. The officers themselves are replaceable, because of the generic, abstract quality of the task before them. They assess objects—or persons objectified—not living subjects. The border-control system that they are paid to operate minimizes as much of their own thinking assessment as possible (Murphy and Maguire 2015: 172). The decisions they make about who crosses and under what conditions are based on a flowchart of “if-then” steps tantamount to high-school geometric proof. For better or for worse, the officer’s ethical judgment is demoted to the least influential variable in the process. The officer’s task is simply to track a series of logical steps based on the traveller’s responses. Those steps w ill determine whether the traveller can enter and on what terms, or how that traveller is to be detained and returned to their home country. In turn, sovereign agents themselves are increasingly surveilled through similarly mathematical procedures now aptly termed “audit culture” (Shore and Wright 2015; Strathern 2000). The second form of sovereignty is arguably much older than the first. It may even be prehistoric in origin. Unlike the first form, which can proceed without the presence of the particul ar speaking subject, the second form of sovereignty issues directly from the particular persons composing it. It emerges through a human impulse to appear before others so that public space materializes out of people’s mutual recognition of each other (see Arendt 1978: 26–30). Those persons think, judge, deliberate, and jointly act from their particular standpoints. Hence people come to life as political beings through their constitution of the second sovereign form. If those persons are replaced, then that sovereign space invariably takes on a different character, as it would then be recomposed by different persons. The second form is a function of the fact of h uman plurality, while the first sovereign form is a function of the myth of collective homogeneity. The investigative team shifts between these two forms, gravitating to the second with e very chance they get b ecause in it they compose sovereign space as they see the world rather than how the security apparatus compels them to interpret it. Their desire to operate through the second sovereign form

Sovereignties and Their Gray Zones 5

is frequently expressed through their criticism of their colleagues in desk investigation and passport control, whose work they see as quintessentially bureaucratic: boring, repetitive, and soul destroying. Hardt and Negri argue that traditional state sovereignty, along with standard forms of vertical bureaucracy, no longer maintains a stranglehold on populations and territories. Instead, “Empire” operates through globally networked institutions, agencies, and practices that are horizontally arranged and integrated through a singular logic of social reproduction (2000: xi–xii). This book readily accepts that point, particularly demonstrating it in Chapter 4, where the team’s investigations are set in a global rather than a national or even EU context (see also Albahari 2015: 18–19; G. Feldman 2012). However, the effect of the first sovereign form still obtains in the global field of Empire because technocratic logics still replace the particularity of an actor’s ethical judgment. Even though formal bureaucratic hierarchies disperse into globally networked organizations, agencies, and institutions, the actor is still subordinated to the logics of security, social reproduction, and capital accumulation as in the traditional nation- state form. Horizontality only fully accomplishes a shift to the second sovereign form when the particularity of the actors’ judgments on unprecedented situations replaces the dominance of abstract logic as the ultimate mode of governance. I first obtained permission to conduct this fieldwork, and publish research from it, from the team members themselves, then from their immediate superior officer, and finally from the national director of their Immigration Service, a component part of their Ministry of the Interior. Permission came with a trade- off: geographical anonymity. I cannot disclose the southern, maritime EU member state in which they work, because much of the activity I observed was either illegal or not compellingly legal. The team cannot take the risk of exposure, although nothing that I report is unusual, as anyone familiar with law enforcement w ill know. Police units are often reticent to permit ethnographers into their midst. Fassin (2013: 14–21; see also Karpiak 2010: 8) details a litany of challenges confronting his fieldwork in Paris. Prior to recent research on police, anthropologists had been studying covert organizations such as nuclear weapons laboratories (Gusterson 1996, 2004; Masco 2006), military bases (Lutz 2002; Lutz and Enloe 2009; Vine 2009, 2015), counterinsurgency warfare units (Gonzalez 2009), and militarized culture more broadly (Gonzalez 2010; Masco 2014; Price 2011). These, too, presented predictable challenges for ethnographic research,

6 Introduction

challenges for which these anthropologists compensated in a variety of ways (see Gusterson 1997; Gonzalez 2012; in non-security contexts see G. Feldman 2011; Nader 1972; Ortner 2010). Yet, for my project, permission came smoothly and quickly, with no substantial barriers to access, an experience similar to Marx in his earlier study of police in the United States (1988: xxii). Senior officers trusted the team’s judgment, and I stressed to the relevant authorities that I was not conducting investigative journalism. The national director of the Immigration Service gave his written approval. My field notes w ere handwritten (illegible to anyone but me), then transcribed into e-files stored on two local computers, which were not networked into any system, and a flash drive. My field notes do not identify the p eople described or quoted or give an indication of the fieldwork location. I give everyone in this ethnography English pseudonyms to prevent hinting at the country through linguistic similarities. I refer to this southern maritime EU member state itself as the “country,” to its citizens as “nationals,” and to the cosmopolitan city in which the team lives and works as the “city.” This access requires that I generalize many of this country’s and city’s particularities for the sake of maintaining anonymity. Yet the team’s actions, discussions, and daily routines are documented in rich detail, rendering the ethnographic context as the way in which they act in the gray zone with the sovereign authority bestowed upon them. Context and action meld into one. This approach—enforced by the conditions of fieldwork—prevents their historical and geographic circumstances from speaking for the team, as it w ere. Distinguishing context from actor risks rendering the actor a passive and dependent variable on the context. Agency would be denied. The key question, then, becomes how the team uses the context as they sense it, rather than how an a priori context preconditions the team. Despite their differences, countries such as Italy, France, and Spain, for example, are squarely premised upon the European nation-state form, which is made an ethnographic reality in the actions that sovereign agents themselves take in the state’s name. In pursuing the question of what conditions enable the second sovereign form, this book also asks several derivative questions specific to the investigative team: How do the team shift back and forth between the first and second sovereign forms? What makes those shifts possi ble? And why do those shifts obtain such significance for them?

Sovereignties and Their Gray Zones 7

Contributions to the Current Critique of Sovereignty Sovereignty, personhood, and action are phenomena that mutually compose each other. The difference between the two sovereign forms lies in whether and how the person can act in the company of o thers. For example, per the first sovereign form, Louis XIV could not have said it better when he proclaimed (or is regarded to have proclaimed), “L’état, c’est moi” (I am the state). Louis’s person became isomorphic with the territorial space of his kingdom as he took action to reconstitute it so substantially that he could don the mantle of Sun King. All life depends upon the sun. That sovereign space rendered his person a worldly reality; without that space, there would be no Louis. However, Louis’s fusion with French political space left no room for the plurality of voices in the kingdom. His sovereign presence denied it as one’s public appearance required deference to Louis’s (sove)reign. The nation-state’s replacement of the monarchical state— inspired by the French Revolution—still retains that silencing effect. While the absolute monarch is a particular person whose sovereign authority marginalizes the particular people in the kingdom, the nation is a homogenizing abstraction, one that marginalizes the citizenry b ecause no particular citizen embodies the nation. This conceptual matter does not deny the well-established point that such sovereign authority never fully takes hold (Appadurai 1996; Bonilla 2017; Davis 2010; Goldstein 2010; Hansen and Stepputat 2006: 297; Jaffe 2015; Rutherford 2012). Clearly, the state has never fully effected what its own etymology claims: a static sovereign land u nder absolute control. Rather, the modern state has always been a work in progress, as the pivotal early modern political philosophers, like Bodin and Hobbes, well recognized (see Jennings 2011: 29). The point is that the modern sovereign’s drive for absolutism remains the project with which we all must contend, so its contours must be exposed for the sake of conceptualizing and identifying genuine alternatives. The second sovereign form keeps alive the equation of sovereignty, personhood, and action, though with the significant difference that it empowers, rather than silences, the plurality of persons that compose it. In other words, the second sovereign form amounts to a space negotiated among equal but different people ever ready to reorganize the terms of their coexistence when they confront unprecedented quandaries for which law, norm, or custom offer little guidance. Their particularity necessarily materializes through their mutual recognition of each other in the course of their speech and action. Without that

8 Introduction

space, none would have a world in which to appear; through that space, they necessarily constitute a polity as joint sovereigns as long as their action continues. Holding the first and second sovereign forms in comparison presents an opportunity to expand and deepen the current critique of sovereignty in anthropology and the critical social science more broadly (Bonilla 2017; Jennings 2011; Kauanui 2017). In keeping with the current critique, there is no question that the European state form has worked violence and degradation on p eoples worldwide through colonialism and imperialism (Anghie 2007; Bonilla 2017; Scott 1999). We should add that the state form has also imparted such violence on Europeans themselves throughout the centuries of its tortured and tortuous history. Moreover, our efforts to understand the political life of the colonized are impaired by the unreflective use of state sovereignty as a Western category of political understanding (Asad 2013; Trouillot 2003). Such habits of thought similarly preclude our understanding of alternative political movements in the global North, movements that seek not only justice on a given issue but also altogether new modes of organizing political life. Thus, the modern state, while functioning as a vehicle to concentrate global power in Europe, has also taken its toll on Europeans themselves as a plurality over the last five hundred years of its development. This point does not equalize the suffering endured in the colonies with that of Europeans. I attempt no absurdly quantitative comparison. I make this point because in order to retain the explanatory power of the concept of sovereignty, we cannot reduce it to the particular result of Europe’s centuries-long struggles with sovereign action, i.e. the modern state. Rather, per the genealogical method of historical inquiry, we must ask what animated that struggle, which could have led to a range of other, now forgotten, possibilities. Similarly, to argue for a nonsovereign politics is a non sequitur. We need to retain that concept because sovereignty is the mode through which the h uman political capacity is either expressed or denied. As biological life is unimaginable with air and food; political life is unimaginable without sovereignty. The dominant view of sovereign power, a view which also limits the current critique, reduces sovereignty to the prerogative of extralegal violence, and so to absolute domination over the body politic. However, as much as sovereign power finds expression in this prerogative, familiarly known as the state of exception (Agamben 1998; Schmitt 1985), it does not capture the full essence of what compels us to sovereign action: the human capacity to inaugurate new beginnings. More concretely, sovereign action materializes the struggle to (re)constitute

Sovereignties and Their Gray Zones 9

political space as it exists between people and break from the old order. (Thus, while violence may transpire in a state of exception, the character of that vio lence will differ significantly relative to the first and second sovereign forms, as discussed in Chapter 2.) In juridical parlance, the capacity to constitute po litical space anew is known as constitutive power, in contrast to constituted power, which subsequently governs that space according to a legal frame (see Jennings 2011: 29). Whether sovereignty materializes through the first or the second form, replete with radically different implications for violence and personhood, is the subsequent question. Hannah Arendt understood better than most that the challenge is to establish “a constituted political order that does not destroy the constitutive power that created it” lest that order destroy people’s capacity to reconstitute political worlds as new circumstances require (40). Hence Jennings (52) stresses the urgency of Arendt’s work in this regard. Sharing that sentiment, Arendt’s oeuvre will inform the analysis that follows. However, one point must be cleared up. Arendt herself appears to argue that the options are, in fact, between sovereignty and nonsovereignty, rather than between two alternative sovereign forms, when the question of how to obtain a genuinely plural political space is asked. With respect to the American Revolution, which she regarded quite favorably, Arendt (2006c: 144) writes that “the great and, in the long run, perhaps the greatest American innovation in politics as such was the consistent abolition of sovereignty within the body politic of the republic, the insight that in the realm of h uman affairs sovereignty and tyranny are the same.” Yet Elshtain (2008: 152–57) correctly notes that Arendt was critiquing a sovereign form as it would appear in centralized European nation- states. To boot, American jurists, contra Arendt, have made continuous reference to sovereignty through the country’s history, even if they thought of it as a foreign concept in the early decades. Stepping back, we see that Arendt’s full oeuvre seeks a central place for joint action in our understanding of the political and of being. It does not dwell on eliminating the sovereignty concept per se (though see 1998: 234–236). For Arendt, political action is the only venue through which being is possible, because it creates public space where we mutually recognize each other as particul ar beings in a shared polity. In this regard, being fully h uman and political action are inseparable. What distinguishes politics for Arendt is not the right of violence and domination, but rather the power to constitute—and reconstitute—that po litical space anew. To put it in near hyperbole, a plurality of p eople acting in

10 Introduction

concert are capable of creating something out of nothing—a public space that has not existed before and that reflects their own struggles, desires, judgments, and actions. This phenomenon characterizes any revolutionary movement that liberates itself from an old order but not necessarily in constituting a new one in its place. The perennial problem that Arendt wished to solve—and argued that the American Revolution nearly solved—is how to institutionalize the revolutionary spirit after the republic is founded. This trick requires us not to reduce government to the mere governance of bodies, lest the sovereign state become the agent of degradation, but rather to locate the power of reconstitution in participatory democratic government itself. In short, if political action is the basic requirement for being human, qua particul ar speaking subjects, then sovereignty must reside in the plurality of subjects composing the polity. Sovereignty is firstly about the original act of constituting political space; it is only secondly, and not necessarily, about the absolute domination of other people. That it has shown itself to be about the latter is, strictly speaking, an accident of history. To expand the current critique of sovereignty, we must extend the genealogy of sovereignty back before the early modern period and recognize what Arendt and Elshtain saw in it. We see that an emphasis on the power of natality and the promise it offers precedes the emphasis on absolutism, which is followed by fatalism and the loss of all purpose. Sovereignty begins its career not as a territorial concept but as a moral one that recognizes God as the creator of all t hings (Elshtain 2008: 2). Augustine reasons through the Trinity that God’s absolute power of creation offers the possibility for people to rise up (but never fully reach) God’s level of wisdom and goodness, symbolized through acceptance of the Trinity’s second figure, Jesus Christ. Augustine maintained, though theologians after Thomas Aquinas would dispute, that each of the Trinity’s three parts—Father, Son, and Holy Ghost—were equals, which gives p eople the hope of fully realizing their true being. As God loves his creation, so he wills not to dominate it but rather to offer it a proximate experience of godliness through the figure of Christ (8–9). From here, he reasoned that no force could exude sovereign power over the bodies of the earthly realm (9). Hence, Augustine’s point in City of God that “[God] did not wish the rational being, made in his own image, to have dominion over any but irrational creatures, not man over man, but man over the beasts” (Augustine 2003: 874). This statement lets us infer that man’s dominion over man, the social configuration of modern state sovereignty, results in the bestialization of all men (Foucault cited in Agamben 1998: 3). The quin

Sovereignties and Their Gray Zones 11

tessential capacity of h umans, the only creatures rendered in God’s image, is the capacity to inaugurate new beginnings and so change the direction of time. That capacity is sovereign b ecause it reflects God’s unbound power to create worlds out of nothing just as God created the earth and all living beings out of nothing. Thus, if humans are created in God’s image, then humans are creators. The birth of each person into the world signifies the birth of one who is a beginner, that is, one who can begin things anew, and not merely a novice to be trained. Arendt thus reads Augustine as offering us a principle of freedom in this regard (Arendt 1998: 177; see also 2006a: 165–66; 1978: 216–17; Elshtain 2008: 4). Hence God’s sovereign power finds its highest expression in the power of creation not arbitrary destruction. This sovereign capacity meant not that h umans were equal to God but that they could construct worldly cities consistent with God’s grace and love. In reverse, God could not impose arbitrary w ill—a Divine version of the modern state of exception—because p eople cannot follow an inconsistent God; they can only fear his unpredictable wrath. Parallel to the juridical interplay between constitutive and constituted power, God is unbound with absolute power, opening all possibilities of action except those that would have him contradicting himself, but is also bound with ordained power, which renders God reliable, regulated, and integral to the worldly political life (Elshtain 2008: 21). From the writings of Augustine in late antiquity to, and including, those of Thomas Aquinas in the late medieval era, this interplay among God, pope, king, emperor, and people never endorsed a singular sovereign with the absolute power of domination. Instead, the relationship between God and people amounts to dialogue in which the power to create is absolute for God and, to a lesser extent, for people, but so are the responsibilities to love and be just. Rather than originating in a transcendent realm, sovereign authority thus flows from two sources, God and people; any king who strove to rise to the level of God above the people would lose legitimacy from both (15). The premodern concept of sovereignty could not accommodate kings, like Louis XIV, seeking to unite both legal and sacred power in their persons as it would have granted them absolute dominion, transcendence in effect. The connotation of absolutism in sovereign m atters initially appears in thirteenth-century France, when monarchies struggled to centralize their rule against the pope’s plenitudo po testati. This tenet granted the pope the power to make and unmake kings; it became a formal creed with Pope Boniface VIII’s bull of 1302, Unam Sanctum (23–24). In response, the monarchs of Christendom aimed for full sovereign powers in

12 Introduction

their respective territorial kingdoms, powers that paralleled, but did not depend on, God’s sovereign power in the Divine realm. They sought freedom from the Divine Law that upheld papal authority. While sovereignty as absolute power over territory and its inhabitants entered the debate in late medieval Europe, it did not dominate that debate until absolute monarchies became a fixture in the political landscape by the seventeenth century. This extended genealogy shows that sovereignty, rather than being the power of absolute domination, begins its c areer as the absolute power of creation. As Arendt insisted that political action was central to our own being in the world, then so must we recognize sovereignty as equally central as it signifies that which most centrally defines us: our ability to inaugurate new beginnings. This comparison of sovereignty on e ither side of early modern Europe is critical for imagining an alternative politics, a politics that is f ree from the tyranny of the state form. It does not matter that we have reached an understanding of this difference through a Euro-Christian historical trajectory. Stripped of its historical particularities, we find the common problem of people striving to establish a constituted political order without destroying the constitutive power that enabled it in the first place (see G. Feldman 2015; Graeber 2009: 214–217). Put differently, the prob lem becomes how to define basic tenets of political life that take on the aura of sacredness, but not to the extent that they cannot be agreeably redefined when new dilemmas call for it. This problem emerges most fully when an old order collapses, or is at least suspended in a state of exception, and a new beginning has yet to take place (Arendt 2006c: 197). Multiple directions are possible in the gray zone that composes this gap in time. The crucial question becomes which sovereign form will materialize when a new order is constituted. The answer depends upon the prevailing view of equality during the interim.

The Differences Between Equality, Mind, and Others in the Two Sovereign Forms During a slow afternoon at headquarters, the team discussed conduct in the gray zone. The conversation moved quickly to two related issues: thinking for themselves and the endorsement of each as independent judges on the other’s conduct. As we had just been talking about bribery, David explained that “if Brian or John saw me take a bribe, then they would lose trust in me. They wouldn’t tell on me, but they would lose their trust in me. That is a huge consequence of messing t hings up in the gray zone.” How does one know what is the right thing

Sovereignties and Their Gray Zones 13

to do in the gray zone? Brian answered, “Sometimes it is hard to know. You know when you are in the black because you are formatted in the white. You know there is black and white. You have to find out for yourself that t here is gray.” John added that “conscience defines the gray zone . . . when I am past the law,” but he also agreed with Max, who explained that “my colleagues must approve any decision I make about g oing into the gray zone.” As officers of the law, this conversation contains within it the interconnected issues of personhood, relations with others, and sovereignty. To illuminate how these issues unfold in lived experience, we must distinguish between two understandings of the word equality. The characteristically modern principle of equality waivered early in its career between two definitions. Equality in the first sovereign form, which now dominates our understanding of the term, refers to the sameness of all citizens. Since all citizens are the same qua nationals, then all must be treated (nominally) the same. One citizen must neither be distinguished from another nor distinguish him/herself from the others for the sake of guaranteeing the same basic conditions for everyone’s life chances. Leaders must closely resemble the led, lest they be regarded as inauthentic, illegitimate, or elitist. Hence a politician should dress folksy like a neighbor, not regal like a king. The demand for an equality of sameness also conditions how we bring our minds to bear upon the technocratic work of maintaining and stabilizing mass society. If we are all the same, then we will be compelled to deploy our abstract reason—the work of the mind’s faculty of cognition—to manage particular problems rather than our own particular judgment (G. Feldman 2015: 55–61). Such reason sustains the equality of sameness because all people reason the same way, or can be trained to do so, as long as they accept the premise from which reason’s logical steps begin. If we accept a number system based on ten, then we will all conclude, once the logic is demonstrated, that 2 + 2 = 4. From that point, one person can perform the calculation as well as another. Hence, all are equal. To stay with our original example, the passport control officers’ if-then decisions are technical judgments based on the logical steps in a flowchart. Once the professional training is complete, one agent can conduct the work as well as another, and so all are replaceable. Recent leaps in border-control technology accentuate the point: algorithmic passport scanners replace the officers, much like automated checkout in grocery stores has replaced cashiers. The replacement of the human with the machine clarifies what was already apparent in the officer’s routine responsibility: that the sovereign “state” requires those

14 Introduction

authorized to act in its name to sacrifice their particularity for the sake of universal reason. Their capacity to think and to ethically judge from their particular standpoint gives way to the logic of sovereign order. Hence the security apparatus’s efficiency demands an equality that renders everyone identical and replaceable as long as they have been properly trained. (This situation parallels the reduction of the laborer to a replaceable extension of the machine, as Marx spotlighted at the beginning of industrialization. For this reason, interviews with state officers so often begin with them first asking, “Do you want to know what I think or what I have to tell you?”) To be sure, the passport control officer determines how any given person or situation falls under one category or another within that template and decides how vigorously to apply the rules and to whom. This wiggle room grants the officer some measure of agency. However, it hardly signifies a challenge to traditional state sovereignty—they are still prescribed the criteria for deciding how to classify any given traveller. The ethical premise of the whole operation remains untouched because the universality of technical judgments replaces the particularity of ethical judgments. The price of the system’s efficiency is the dumbing down of its officers to the point of rendering them dispensable. Work becomes a bore interrupted occasionally by the thrill of a security breach. Equality in the second sovereign form appears as the equal empowerment of different p eople rather than as the protection of ostensibly homogeneous people. Those differences are initially manifested through the faculty of thinking, not the faculty of cognition. Rather than the tracking of logical steps, thinking amounts to the inner two-in-one dialogue with the self about how to live in the world. We seek agreement with ourselves for the sake of settling our consciences, John’s guide for action in the gray zone. Thinking is unavoidably subjective and stimulated by our receptiveness to the world. No two people can think alike—that is, no two p eople can ethically assess situations exactly the same way, because no two p eople occupy the same standpoint in the world (Arendt 1971, 1978, 1992; G. Feldman 2015: 55–61). Thinking persons constitute sovereign space by making ethical judgments about how to act upon unprecedented situations, situations that they cannot address by appealing to existing standards (in the shape of laws, moral codes, flowcharts, or rote bureaucratic procedure). Through persuasion and consensus among a diversity of judgments, thinking subjects jointly act to (re)constitute space so that living in it does not generate a crisis of conscience. Sovereign power manifests in the joint action itself.

Sovereignties and Their Gray Zones 15

The second sovereign form guarantees each participant’s presence in the com pany of one’s peers, all as constituent members of the polity. We are more likely to regard o thers as different but equal because our own particularity likewise gains a worldly presence through their recognition of ourselves. This phenomenon of mutual recognition decreases the likelihood of us degrading others, b ecause o thers would then confirm us to be the very person we wish to avoid: one who degrades others. Our worldly appearance would then create a contradiction in the two-in- one thought dialogue, leaving us at odds with ourselves and suffering a crisis of conscience. Without mutual recognition, all actors become alienated for lack of others with whom to constitute shared space in which they establish themselves as political subjects. The argument is not simply that we adopt a more open- minded attitude toward other people, be they neighbors, colleagues, or strangers. Rather, we are less likely to degrade o thers because our appearance before them is how we necessarily constitute ourselves as beings in the world. Although the second sovereign form allows the particular person to be, as it w ere, it is not a liberal form of sovereignty, because it does not assume the a priori existence of the individual subject. Again, subjects can only obtain a worldly existence through mutual recognition. Without such recognition, one cannot exist in the world, if by “world” we mean a shared, if contested, space of meaning. The public that emerges in that shared space, then, yields not a h omogeneous “people” or “nation” but rather the appearances of particular persons whose speech and action conjured them into existence. The second sovereign form is a direct effect of a plurality of people being together as political equals. Hence the elderly Syrian refugee insists not that the liberal “I will be” but rather that the phenomenal “we w ill be.” The difference between the first and the second sovereign forms spotlights the conditions through which we can appear in the world through the particularity of our own phenomenal being. To understand the difference between being human in the first and second sovereign forms respectively, it helps to revisit Aristotle’s distinction between the human qua animal and the human qua political actor. The former (zöe) need only reproduce its generic, biological existence through a field of social relations with other identical specimens of the human-animal. Biological reproduction works in tandem with social reproduction among a collective of identical, indistinct, and equal subjects. The latter (bios) requires a venue in which it can distinguish itself through speech and action with o thers. The former assumes that all persons are essentially the same, while the latter assumes that all persons are qualitatively different.

16 Introduction

The different implications that each realm holds for political life could not be more decisive. This clarification allows us to better conceptualize two terms that are central to understanding action and central to much current anthropological literature as well (Chapter 2). First, ethical refers to actions a person takes to reach inner agreement—through the faculty of thinking—about how to live in the world with others. Put differently, ethics begin with the two-in-one thought dialogue, which divides the erstwhile unitary subject into two separate voices that the subject tries to align in order to s ettle the conscience. Ethics in this regard does not mean living according to social norms and expectations with which one might justifiably agree. Rather, inspired by thought and judgment, ethics materialize in the world through original, extraordinary actions to intervene in ongoing processes of which the actor cannot tolerate being a constituent part. As Cabot shows, one’s ethics can blend with the technical judgments that asylum adjudicators make, as one example, while t hose actors might reflect on wider social narratives, particular encounters, and different forms of knowledge to reach a decision. Hence the application of law cannot be reduced to law itself (2014: 2–3, 7–8; see also Coutin 2000; Maguire 2015; Maguire and Fussey 2016). Yet ethics alone do not inherently challenge the basis of sovereign power, even if they empower us to manipulate law, bureaucracies, and apparatuses. Ethics inspire in dividual actions, which, unlike joint action, cannot result in the (re)constitution of sovereign space, because space only emerges between multiple persons. Second, political refers to joint actions among different but equal people to constitute a shared space in line with their ethical judgments and allows them to reconstitute that space when deemed necessary. Political h ere refers neither to Machiavellian strategies for securing one’s hold on power nor to Marxist notions of reproducing structures of inequality that privilege one group over another. To hold leverage over others does not grant one freedom of being (see G. Feldman 2015: 13–14). On the contrary, it can further isolate us from the world, just as the tyrant is the strongest and the loneliest player in the game. In short, this book will regard politics not as the advancement of self-interest but rather as the struggle to establish our sovereign presence in a world we necessarily constitute with o thers. The political enhances and institutionalizes the ethical for as long as p eople decide that it applies to the status quo. Ethical actions occur in synchronous moments. Political action moves beyond the synchronous moment by establishing direct bonds between subjects that last through time through shared memory (i.e., lasting beyond the participation of those sub-

Sovereignties and Their Gray Zones 17

jects and getting inherited by others through a new tradition). The polity, then, outlasts the participation of any given member and so assumes a quasi-immortal status (Arendt 1998: 17–20). Therefore, ethics and politics are things of action through which actors become subjects who constitute worlds. We undertake sovereign action to effect the world (and not simply affect it) b ecause we strive for being—a human existence only obtainable in the company of equal but differ ent people. Any examination of how polities are constituted invokes “migrants” because the term invariably refers to “others” through and against whom we constitute ourselves (Cabot 2014: 8). However, our relations with others need not proceed on the basis of abstract, categorical types (in a word, stereotypes), in which case the other becomes the Other, or the particular person crossing a border mysteriously becomes a categorical “migrant,” “alien,” “temporary laborer,” and so forth. In the ethnography that follows, I do not dwell on the extent to which the investigative team’s actions indicate the ethical or the political as the difference is one of degree not kind. The question that needs attention is how the second sovereign form materializes at all in a world so thoroughly dominated by the first.

Conceptualizing the Gray Zone of the First Sovereign Form Like state sovereignty, the gray zone is an effect of human relations, not a preexisting netherworld into which people arrive from elsewhere. The gray zone is a point in space-time free of the constraints and contours of moral code and law, which is where sovereign power expresses itself in the original act of (re)constitution. Sovereignty and the gray zone are inextricably linked as the latter is a precondition of the former, and the former can only reveal itself fully in the latter. State sovereignty, despite its mythical reputation, never materializes in a totalizing objective presence, for the simple reason that persons, who by definition are subjective beings, are the agents who materialize it. “Subjective” means nothing more than occupying particular standpoints. Even the sum total of those standpoints reaches not a transcendent, universal order but only a historically contingent, global order ever vulnerable to contestation and transformation. By analogy, Vincent demonstrated the illusion of transcendent state sovereignty through the metaphor of an inkjet printer, which prints, for example, a black square, composed of countless microscopic dots, on a white sheet of paper. Held from a distance, that black square appears to fully enclose a bounded area within an undefined expanse of limitless, uncultivated white space. The

18 Introduction

boundary between emptiness and order—between inside and outside—appears cleanly at the juncture of perfectly white space and perfectly black space. Under a microscope, however, the picture looks much different: the ink does not totally cover that apparently bounded area; instead, the innumerable black dots only resemble total incorporation, but they neither fully blot out the white space nor establish an impermeable border against it. The white space infiltrates the black space by design and conditions how it appears on the page. Thus, like the black space, state sovereignty as an objective reality is an optical illusion. But this point does not deny its reality. Rather, it calls out sovereignty as a subjective real ity, meaning it appears out of the practices of situated persons authorized to act in the name of the state. No objective reality can truly emerge from subjective beings, otherwise known as human beings. As Herzfeld (2008: 87) puts it, “The state is . . . emergent in practice; while it does ‘exist’, our knowledge of it comes from our practical engagements with its various realizations in bureaucracy, law, and surveillance.” Recent academic literature overwhelmingly understands the gray zone, along with the associated concept of sovereignty, through Agamben’s (1998) “state of exception” and his term homo sacer. This perspective addresses the sovereign’s prerogative to suspend the law, which then grants it impunity to deal directly with the security threat. As the sovereign establishes the constitution, it can suspend the laws that emerge from it, b ecause the sovereign is logically prior to the constitution. We can detect echoes of Foucault (2007: 261–67), who flags the irony that the coup d’état (the suspension of legal order to suppress a threat to the sovereign) is the prerogative of the raison d’état (the responsibility of the state to provide legal order). Hence the coup d’état is the expression of the raison d’état in full force. When targeting the threatening subject, the sovereign removes the l egal protection that this subject has hitherto enjoyed, thus rendering it homo sacer. (This term means “sacred [hu]man,” but it signifies an entity that is simply outside of mundane order rather than part of the Divine realm.) Hence homo sacer becomes a subject who can be killed with no consequence for the killer. Agamben’s most radical and insightful point, however, is that sovereign order is premised upon homo sacer ’s ambiguous position relative to the sovereign: this figure is both the foundation of state sovereignty (as the embodiment of the mass “people” in whose name sovereign state exists) and also that which the state may exclude if the sovereign calls for a state of exception. The generic “people” underpin state sovereignty, but any particular person can be dis-

Sovereignties and Their Gray Zones 19

missed at no risk to the sovereign. In brief, the sovereign gets it both ways with respect to homo sacer. The upshot is that the first sovereign form begets the figure of homo sacer because sovereignty is premised upon an abstraction (i.e., it is premised upon the “people,” who by definition cannot speak; only actual persons can speak). Hence the p eople, or a subcategory of them, cannot defend themselves from being dismissed, b ecause they themselves are not sovereign, but rather sovereignty is simply issued in their categorical name. Agamben argues that the state of exception becomes permanent when the concentration camp fully materializes. Short of that moment, full-scale sovereign authority is dispersed about the social configuration that embodies the state (or status quo). This dispersion does not qualitatively eliminate the state of exception but rather dilutes its dehumanizing effects, because law and custom more reliably protect the individual subject. This contradiction—state sovereignty premised upon an abstract entity that the sovereign can simultaneously exclude—does not appear in the second sovereign form, because particular persons themselves instantiate their sovereignty through their joint action. No action; no sovereignty. Cecilia, the only woman on the investigative team, readily grasped the irony “that the state d oesn’t care about me even when I arrest a criminal. The law cares, but not the state. If the state cared about us, then we would not be taking pay cuts for the last three years.” Among other interlocutors in Agamben’s analysis is Carl Schmitt, whose unfortunate association with Nazism makes it difficult today to appreciate what motivated his inquiry into the state of exception. Pinpointing what led Schmitt into a dead end spotlights what we need to know to better understand the second sovereign form. Oddly, Schmitt’s analysis seeks to recapture an under standing of sovereignty as the empowerment of people to inaugurate new beginnings rather than domination per se. It ultimately falls on his mistaken identification of plurality as a descriptor of states rather than actual persons. As Schwab notes (1985: xlii), Schmitt lamented the rise of technocracy and its elimination of the personal from political space. The modern state, Schmitt writes, “seems to have become what Max Weber envisioned: a huge industrial plant. Political ideas are generally recognized only when groups can be identified that have a plausible economic interest in turning them to their advantage” (65; see also 27–28). He adds that “what we can still call the state t oday must inversely be defined and understood from the political” (cited in Strong 2005: xv, italics added). The state’s hyperformality(i.e., its unwavering commitment to the rule

20 Introduction