The French-Canadian Outlook: A Brief Account of the Unknown North Americans 9780773595033

113 65 17MB

English Pages [114] Year 1964

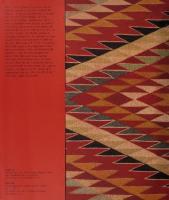

Cover

Title

Copyright

The Carleton Library

Note On The Author

Contents

Preface to the Carleton Library Edition

Preface to the Original Edition

1. New France: 1534-1759

2. The Meeting of French and English: 1760-90

3. Two Peoples Make a Nation: 1790-1867

4. The Conflict of Nationalisms: 1867-1918

5. Growing Pains: 1919-45

6. Quebec Today and Tomorrow

Suggestions for Further Reading

Index

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Mason Wade

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

The French-Canadian Outlook A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF THE UNKNOWN NORTH AMERICANS

BY

Mason Wade WITH A NEW INTRODUCTION BY THE AUTHOR

The Car/eto" Library No. 14 McClelland and Stewart Limited

The following dedication appea red in the original edition:

TO

those Canadians who cheerfully undertook my educa tion, but are not responsible for the results

@ 1964 McClelland and Stewart Limited Reprinted by pennission of the Viking Press

ISBN: 0-77 10-97 14-X

The French-Canadian Outlook by Mason Wade was fi rst published in New York by the Viking Press in August. 1946. and was published on the same day in the Dominion of Canada by the Macmillan Company of Canada Limited.

The Canadian Publishers McClella nd and Stewart Limited , 25 Hollinge r Road, Toron to

Design: Frank Newfeld

Printed in Ca nada by Webcom Limited

THE CARLETON LIBRARY

A series of Canadian reprints and new

collections of source material relating to Canada, issued under the editorial supervision of the Institute of Canadian Studies of Carleton University. Ottawa.

DIRECTOR OF THE INSTITUTE

Pauline Jewett GENERAL EDITOR

Robert L. McDougall EDITORIAL BOARD

B. Carman Bickerton ( History) Michael S. Whittington (Political Science) Thomas K. Rymes (Economics) Gordon C. Merrill (Geography) Bruce A. McFarlane (Sociology) Derek G. Smith (Anthropology)

NOTE ON THE AUTHOR Mason Wade is one of the best known English interpreters of French Canada. Born in New

York in 1913, he studied at Harvard and subsequently held a Guggenheim Fellowship for the purpose of research in Quebec, where he lived

for two years. From 1951 to 1953 he was Public Affairs Officer of the United States Embassy in Ottawa. In 1955 he was appointed to the University of Rochester as Director of the newlyestablished Canadian Studies Program. He has lectured at several Canadian universities, including Laval, Toronto and British Columbi a, and in

1963 was Visiting Fellow at the Institute of Canadian Studies at Carleton University. In 1965 he joined the faculty of the University of Western Ontario as Professor of History. He has written two biographies : Margaret Fuller: Whetstone oj Genius (New York, 1940) and Francis Parkman: Heroic His/orian (New

York, 1942), besides editing the writings of these two figures. The French-Canadian Outlook (New York, 1946) was his first venture into Canadian

history and was followed by the longer The French Canadians, 1760-1945 (Toronto, 1955). More recently he has edited a collection of essays by various writers entitled Canadian Dualism:

Studies oj French-English Relations (Toronto and Quebec, 1960).

CONTENTS

Preface to the Carleton Library Edition Ix Preface to the Original Edition xiii

1. New France: 1534-1759 1

2. The Meeting of French and English: 1760-90 14 3. Two Peoples Make a Nation: 1790-1867 27

4. The Conflict of Nationalisms: 1867-1918 40

5. Growing Pains: 1919-45 57 6. Quebec Today and Tomorrow

78 Suggestions for Further Reading

88 Index

89

PREFACE

The Carleton Library Edition

This book, written in 1945, was designed as a brief interim report 00 a research project on which I had been engaged for five years, and which took five more years to complete. It was written with a seDse of urgency, in the hope of dispelling some of the tensions between English and French Canadians which had arisen during the Second World War, and which came to a head in the conscription crisis of 1944-45. It is now republisbed in the midst of a new crisis in French-English relations, with a tumultuous Quebec questioning the value of continuing Confederation on the prescnt basis, and threatening to leave it unless French-Canadian demands for changes are met. So much water has poured over the Quebec dam since 1945 tbat this book might appear to be completely outdated. Inevitably the passage of time has invalidated some of the observations in the final chapter, while it has confirmed others. I have not attempted to rewrite it, for its picture of the situation in 1945 still helps to explain subsequent developments. But the major part of this book is an account of the French fact .in North America, an outline of the historical reasons why the French Canadians have a different outlook from that of English-speaking North Americans. This account stiB holds good, I believe, and supplies essential background for understanding the present situation, which has deep historical roots.

x - THE FRENCH·CANADIAN OUTLOOK

Mucb bas cbanged in Quebec since 1945, and particularly since 1959, when the death of Premier Maurice Duplessis, who . for fifteen years bad sougbt to resist the currents of social change which were sweeping the province, released a flood of pent-up forces. That flood is still raging today. In 1912 Louis Hernon, in his Maria Chapdelaine, had the voice of Quebec declare: "Nothing changes in Quebec, and nothing should cbange." Today almost everything is cbanging, and there is general agreement that it should change. Quebec is in the midst of a social revolution, all the more explosive for having been long repressed. But one thing bas not cbanged: French Canada's preoccupation with survival, with preserving its own identity, which remains stronger than ever, despite the vastly increased pressure of outside forces upon Quebec in the postwar period. Indeed, the old concern for survival has developed a broader base. Today the French Canadians want not only to be masters in their own house in Quebec, they also want to be accepted as equal partners, not second-class citizens, throughout Canada. There has been a swelling demand from French Canada for a broader biculturalism fro m sea to sea, based upon the spirit rather tban tbe letter of the British North America Act. Expressions of discontent with the present French-Canadian position in Confederation have come not only from leaders of the separatist movements, who have made more noise than disciples, but from Quebec's present premier and leader of the opposition. There have been calls for a complete rewriting of the B.N.A. Act, for its reorientation, and even for its repudiation by Quebec. A considerable number of French Canadians are willing to envisage the end of Confederation as its centennial approaches, disregarding the serious economic consequences to Quebec of independence and the catastrophic consequences for the French minorities in the other provinces. The solid basis of this agi tation, which often tends to be more emotional than rational, is twofold. Since 1960 the Lesage government has embarked upon a sweeping program of economic and social reforms, designed to raise the average Quebec standard of living and the province's social services to the Ontario level. To accomplish its aims, it wants to direct if not to control the province's economy. It wants a larger share of

PREFACE - xl

the revenue from the tax fields taken over by the federal govern~ ment, and more control of federal expenditures in the province. But more politically potent than this militant attitude about economic autonomy and provincial fiscal rights is its desire to assure equality for French Canadians everywhere in Canada, to have Canada become a fully bilingual and bicultural country. On this question the Lesage government's hand is being forced by the opposition, Social Credit, and the separatist movements. which seek power br promising quicker action. The French Canadian has long been convinced that he is discriminated against in business and industry, in the federal civil service, and in the armed services. He has long deplored the incompleteness of Canadian bilingualism and biculturalism, when well over a million of the five and a half million Canadians of French origin live outside Quebec. He has grown weary of the long struggle for recognition of his rights everywhere in Canada, and he now wants immediate action to make Canada more fully a bicultural country in which a French Canadian can enjoy equal opportunities. Quebec is in no mood to stay for an answer, while in several of tbe other provinces the old reluctance to accept biculturalism outside Quebec, except to a limited degree in Ottawa, rem ains strong, despite the real progress that has been made since 1945 toward a broader biculturalism, largely through the leadership of the federal government and the universities. The recently appointed federal Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism has an urgent and difficult task to perform in making recommendations which wilJ at once satisfy Quebec and still not arouse the militant opposition of those Canadians who refuse to accept the French fact as a basic condition of Canada's continued existence. Government policy and action can do much to ease the present crisis. But in the last analysis the Canadian partnership of English and French can only flourish upon the basis of a much more widespread mutual understanding. It is my hope that this book may help in some measure to serve that end. MASON WADE

University 0/ Rochester January, 1964

PREFACE

The Original Edition

Those who do not know Quebec at first hand, but only through romantic fiction, the literature of tourist bureaus, and the Quebec myth publicized by some French-Canadian spokesmen, are apt to think of a quaint, picturesque. predominantly rural region which is an island of seveoteenth- and eighteenthcentury France in twentieth-century North America. Such a Quebec, immortalized in the pages of Maria Chapdelaine, still exists in a few backwaters of the province, but it is rapidly disappearing. Another and very different Quebec has appeared of late in newspapers and magazines: a restive, turbulent province, torn by strikes, nationalist demonstrations, and mass meetings against conscription, a centre of great modern industries and restless urban masses. This is Quebec of today, admir~ ably analysed in French Canada in Transition; and out of it, after much more turmoil and verbal violence, will come the Quebec of the future. The French Canadians are no longer an agricultural people; Quebec now has the highest percentage of urban populhtion of any Canadian province, and with Ontario it is the centre of Canadian industry. "Progressive" Ontario bas more farmers than "backward" Quebec, whose urban popul ation increased thirty-seven per cent from 1921 to 1931, and sixteen per cent from 1931 to 1941. The figure for the last five years is not yet

J.iv - THE FRENCH· CANADIAN OUTLOOK

known. but is probably larger than that for 1921-31. thanks to Canada's great wartime industrial development. The Greater Montreal area now includes more than half the population of the province; and Montreal is the metropolis of Canada. These facts are the basis of the recurrent "crises" in Quebec, which are in reality growing pains. A region devoted to the past, and with a great innate resistance to change - which may endanger what a minority group has struggled hard to secure in the past has been subjected to the powerful social forces of industrialization and urbanization, with the process speeded up by the urgent necessities of war. These forces come largely from outside the province and have usually been directed by outsiders, thus arousing opposition from a people whose acute awareness of their minority status has given them a very highly developed group consciousness, and a fear of influences which might endanger the values they hold dear. The natural results have been discontent, protest, and social unrest. These have been sensationally chronicled in the English-speaking press of North America, which is ill-informed about French Canada, as, to a lesser degree, the French press is badly informed concerning English Canada and the United States. Ignorance on each 'S ide of the linguistic and ethnic fence breeds suspicion of the people on the other side; suspicion of the unknown breeds fear; and fear, under certain conditions of tension, such as war or economic crisis, leads to aggressive words or acts. This book is an attempt to show in brief why the French Canadians think and act in ways differing from those of English-speaking North Americans. It is the story of the struggle of a minority group to maintain its cultural identity in the face of all manner of conscious and unconscious pressure to conform to the civilization of other ethnic groups and another culture. It is also in some measure an account of what the French Canadians call the "French fact in North America," for only by tracing out the cultural history of French Canada from its beginnings can the present position of Quebec be understood. The unifying thread of that history is the spirit known as "nationalism," which in this instance is actually a provincialism complicated by ethnic and religious factors. Therefore particular attention will be devoted to the extremists of a generally peaceful people who have a remarkable devotion

PREFACE -

:n'

to the golden mean as a principle of life. The attitudes of minority groups can often be explained only in psychological terms, and French-Canadian attitudes are a good example. Sir Wilfrid baurier, perhaps the greatest French Canadian, once put this fact into words when he said, "Quebec does not have opinions, but only sentiments." So this short history will also be in some measure a psychological study. There are certain advantages in writing the history of a country of which one is not a native. This is perhaps particularly true when writing of Canada, a country divided into two main cultural groups, between whom there is a serious lack of communication and understanding, and whose differences have long blinded the two groups to the intricate interweaving of the histories of Canada and the United States. Because of ancient difficulties and a tradition of diplomatic relations between English and French Canadians, an American, who has much in common with both, often finds that either sort of Canadian will unburden himself more fully to the stranger than he would to his fellow countryman of the other ethnic origin. I am grateful fo r the light thus shed upon the matters with which this book is concerned, which are not exclusively Canadian in nature. While there are three and a half million· French Canadians in Canada, there are also two million Franco-Americans of Quebec and Acadian stock in the United States. These minority groups, which in the past have shown a tendency to stand apart and preserve their separateness from English-speaking North Americans, are thus of common concern to all Americans, whether citizens of Canada or the United States. The problem of understandi ng them is a continental rather th an a national one. I happened to grow up in New Hampshire among the Franco-Americans; I have long had a special historical interest in French Canada; and fo r five ye ars I have been doing research on the subject, in Quebec itself for two years, thanks to the Guggenheim Foundation. It was my good fortune to travel very widely through that province, which is larger than France and Britain combined, meeting and discussing matters with all classes of its people, and learning some of the things which -Five and a half million today.

...

xvi - THE FRENCH · CANADIAN OUTLOOK

cannot be found in books. The present work, which is an epitome of a more detailed and fully documented study still in progress,t is an attempt to present for the general reader the significant facts about French Canada, so far as they could be uncovered by disinterested and objective investigation, without recourse to the wishful thinking that in the past bas made the standard English and French histories of Canada so dissimilar as to suggest that they were histories of two different countries. It is my hope that this book will serve to dispel some of the misunderstandings between English and French North Americans. In the course of writing it. it has been necessary to state some hard truths; this has been done without malice and without any design other than to present the facts. For this book is concerned with what has been and what is, rather than with what should be; and it has been written in accordance with the dictum that the first law of history is not to lie. and the second not to be afraid to tell the whole truth. MASON WADE

Cornish, New Hampshire December 1945

•

1Mason Wade, The French Canadians, 1760·194' (Toronto, 19S5).

1.

New France

'" ...., ....,

1534-1759

The French Canadians live in and on their past to a degree almost inco nceivable to the average Englisb·speaking North American. Quebec's motto is "Ie me souviens" ("I remember"), and this motto is no mere empty formula, for tradition is a stron ger force there today th an anywhere else in North America. The differences which exist in historical points of view between English and French Canadians are in part the result of a tendency toward wishful thinking in both instances, for each group calls itself Canadian and qualifies the Canadian ism of the other. But essentially the differences are due to Canada's division into two main cultures, between which there is at times of economic or political crisis an almost unbridgeable abyss; while a certain amoun t of conscious or unconscious racism, the heritage of ancient English-French enmity, enters into th e thinking of each group about the other. Pierre Chauveau, the first premier of Quebec after Confederation and one of the first French-Canadian literary men, likened Canada to the famous staircase of the Chateau de Chambord, so constructed th at two persons could ascend it without meeting a nd without seeing each other except at

2 - THE FRENCH -CANADIAN OUTLOOK

intervals: "English and French, we climb by a double flight of stairs toward the destinies reserved for us on this continent, without knowing each other, without meeting each other, and without even seeing each other, except on the landing of politics. In social and literary terms, we are far more foreign to each other than tbe English and French of Europe.'" As Canada has developed into a more coherent nation, the problem of communication has become more serious, since the English and French groups, which must. co-operate for the common welfare, for the most part grow up in separate compartments and rarely achieve much firsthand knowledge of each other until their distinctive mentalities have been formed and their emotional reactions have been determined by heredity and environment. The ancient tradition of unrealistic diplomatic relations between English and French Canadians no longer suffices; each group of necessity must achieve a better knowledge and understanding of the other. If English Canadians and Americans, instead of talking with a certain implication of superiority about the "French-Canadian problem," should adopt the term used by the French - "The French fact in North America" - and face that fact, instead of trying to controvert it, a considerable advance toward understanding would be made. For tbeir part, the French Canadians might dwell less on ancient difficulties and give greater recognition to the inescapable logic of their geographical and economic situation. But a majority has a greater obligation to do justice to a minority than vice versa. What does "Je me souviens" mean to the French Canadian? Above all, it means that he remembers the days of New France, the heroic period of the French in America. The story of New France has been told too often and too well - most ably in English by Francis Parkman:! - to be retold once more, but its salient features must be recalled here because of their bearing on the present. Some of the strongest forces in contemporary French Canada derive directly from the seventeenth century: the religious zeal of the Counter Reformation or Catholic Revival, the cultural tradition of classicism, the political idea of absolutism or benevolent despotism, and a semifeudal, hierarchical concept of society. To this golden age of French Canada its own historians have devoted dispropor-

NEW FRANCB - 3

tionate attention; every aspect of the French period has been fondly discussed and re-discussed, while many important phases of the English period (1760-1867 ) and the Canadian period (1867 to the present) have been left untouched and unconsidered. The French Canadian tends to console himself for an uncomfortabJe position in the present by dwelling upon the glories of his past. This very understandable psychological reaction also explains the tendency of his historians to romanticize the history of New France, which is in itself so romantic as to need no added colouring. Many English-speaking writers have been moved by the same subject to romantic excesses. This general tendency has had the effect of spreading a golden haze of glorious legend which clouds the facts . It is a legend, however, which is very real for the French Canadian, whose most popular historianS has made familiar the phrase "Notre maitre, Ie passe" ("Our master, the past"). and established it as a principle for action in the present and the future. The recent observation of a popular English-Canadian historical writer4 that the history of Canada begins in 1867, with tbe Confederation of the British North American provinces, grated on the French Canadians' pride in their past, and tended to confirm their belief that they arc the only true, as well as the oldest, Canadians. New France was founded during the Reformation. when theological controversy and wars of religion racked the European world. Bloody religious strife was carried across the sea to New Spain, New France, and New England; in their infancy the struggling young French and E nglish colonies were opposed by religion, with the French excluding Protestants from Canada and the Puritans barring Catholics from New England. The religious clement was never absent from the second Hundred Years' War which the French and English waged against each other in America until the downfall of New France. This

'*'

Pierre J. O. Chauveau, L'/tulructlon publique ou Canada (Queb«:, 1876), p. 33S • • In his seven-part France and Englan d in Norlh America. The Old Regime In CaJlada is an ucellent summary o f the socinl history of the French regime. • Canon Lionel Groulx. 'The late Stephen Leacock.

1

4 - TH E FRENCH·CANADIAN OUTLOOK

fact has left its mark on the French-Canadian mentality, wbich weds the concept of nationality to th at of religion and asserts its separateness from E nglish-speaking North America on both counts. The destiny of New France was also shaped by the fact that in the seventeenth century, the great age of the Catholic Revival or Counter Reformation in France, the renewed energy of the Church found in America an outIet from the restraints imposed at home by the dominance of the State und er Louis XIV. The new religious spirit found heroic exp ression in the missionary activity of the Jesuits and Recollects ~ who saw to it th at the Cross accompanied the fleur-de-lis from the Atlantic almost to the Rockies, and from Hudson Bay to the Gulf of Mexico, as the French explorers bared the heart of the continent to which Jacques Cartier's "river and road" of the St. Lawrence waterway led them. And while the missionaries made their black and grey robes familiar to two-thirds of a continent, devoted bands of religious and pious layfolk cultivated the seeds of civilization on the banks of the St. Lawre nce, where the fur traders had established only semipermanent posts. From the earliest days of settlement, edu cation and the care of the sick and needy were included in the province of the Church. whose missionaries also performed governmental functions as dip lomatic agents among the Indians and as financial agents in France for the struggling colony. Thus the Church played a vital role in the life of New France, and a theocracy developed wh ich startled worldly visitors. Through these theocratic pioneers two great ecclesiastical disputes of the age of Louis XlV left a lasting mark on tbe French-Canadi an mentalit y: the stri fe between Jesuit and Jansenist, and the struggle between Gallican and Ultramontane. The dominance of the Jesuits in New France gave short shrift to the doctrine of their enemy Cornelius Jansen, but nevertheless his ascetic and piet istic influence was felt through the close connections of the nuns of Quebec and Montreal with the circles most affected by his thought in France. F renchCanadian Catholicism has ever since had a strai n of J ansenism in it, as North American Protestantism bas a strong flavour of the rather similar Puritanism. Then the strife between Louis XlV and Pope Innocent XI over the relations of Church and State was reflected in New France by bitter quarrels between

NEW PRANCE - ,

bishop, governor, and intendant under the three-headed autocratic system of French colonial administration. But two of the four fundamentals of Gallicanism were reversed in the colony, where in things temporal the civil authority came to be considered subject to the spiritual power, and where the Pope's authority was regarded as supreme and nol subject to the interference of the State or the usages of a national church. While Gallicanism carried the day in Louis XIV's France, Ultramontanism triumphed in New France under the vigorous championship of autocratic Bishop Laval, who vanquished a series of Gallican-minded governors and intendants. Ever since that time French Canada has remained a stronghold of clericalism, and very conscious of its spiritual dependence upon the Holy See.' When New France was founded, France stood upon the threshold of its greatest age, with a population three times as large as that of England and Wales, and a military establishment as great as that of the Roman Empire at its peak. Macaulay has admirably epitomized the French hegemony of the period : "France had, over the surrounding countries, at once the ascendency which Rome had over Greece, and the ascendency which Greece had over Rome."7 Louis XIV was the military master of Europe, while his brilliant court made French civilization the model of tbe Western world. Latin at last yielded to French as the language of scholarship and diplomacy; and French authority became supreme even in such minute matters as dress, cuisine, and dancing. France was also united as was no other European nation of the period; under the first three Bourbons the monarchy had become so powerful that Louis XIV could justly say "I am the State," and be supported in this declaration by Bossuet, the greatest contemporary spokesman of the Church in France. New France had an

"*'

'An ascetic braneb of the Franciscans. 'The wide display of papal nags and portraits In Quebec - they arc more prevalent there than in Rome ltseU - is in part an asse rtion o f tb.is ,plrituaJ dependence, and in part an assertion of the Freneh C!ln!ldian's distinctive tradition, like h is own display of the French Tricolor and the English Canadian's display of the Union Jack. The French Canadlnns have been the leaders In the demand for n distinctive Canadino nng, whose adoption wns proposed by Mackenzie King In 1945. , T . B. Macaulay. Hi-fI. 0/ England (Boston, 1899), H, 116.

6 - THE FRENCH-CANADIAN OUTLOOK

unequal share in the glories of the mother country's greatest age, but the spirit of that age has survived tenaciously in Quebec. The seigneurs, the much-romanticized petite noblesse of New France, had little in common with the great French nobles: in lineage, wealth, and power they were as nothing compared with the brilliant figures of the court. Canada was a refuge for younger sons and those whose titles were grander than their purses. The haute noblesse had little to do with the colony, and few came to it, although some were fitfully interested in the fur trade and others gave moral and financial support to the missionaries·. Although New France was often neglected by a monarchy far more concerned with Europe than with America, the prevailing French absolutism, which was tempered by paternalism, affected every aspect of the life of the colony. After the fiasco of Jacques Cartier's "Canadian gold" and "Quebec diamonds" - which proved to be iron pyrites and quartz crystals - the treasure-seeking Valois lost interest in the New World, while Canada played a minor part in the preoccupations of the Bourbons. Under both Louis XIII and Louis XIV Canada was commonly regarded in worldly France as the last resort of the ruined, the alternative to a prison cell, long before Voltaire dismissed its casual cession to England in 1763 as the loss of only "some acres of snow." Though the Bourbdns left a lasting mark on New France, their influence was not as great as that of the Church, whose encouragement of the colony was less fickle than that of king and court. After the disruptive religious wars of the sixteenth century. which checked exploitation of Cartier's discoveries, Henry IV gave to Protestant and Catholic alike patents to develop New France; if tbis example had bee'n followed by his successors, the scantily-populated colony might have profited by an influx of Huguenots driven from France by the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. But it was the intention of Richelieu and the Jesu its that Canada be a wholly Catholic land. free of the rel igious quarrels and scandals of France. The great Cardinal tried to give the French traders of the northern seas the same support wh ich the English and the Dutch provided for their merchants of the Indies; but the monopolists of the

NEW FRANCB - 7

fur trade failed to fulfill their promises of colonization, and the misfortunes which beset the successive trading companies led to piecemeal and inadequate development of the colony. At the outset of his reign Louis XIV gave the colony more support than it had formerly received from the rulers of France; then European ambition replaced his colonial zeal. Colbert, the administrative genius behind the glory of the Sun King, left his mark on the colony through the able intendant Talon, but, amid aU his European concerns, could never really give it the attention it deser·ved. During the seven years after 1663, when royal government replaced the monopolistic trading companies which had hitherto controlled the colony, New France was made over in the image of Louis XIV's France. The first Quebec Council, which included an element of representative government, was replaced by an autocratic Sovereign Council, at once administrative, legislative, and judicial, which was dominated by bishop, governor, and intendant. Their dissensions had been foreseen by an absolutist monarchy which wanted no supreme ruler in the colony. The way of life of New France was to be radically altered, for Colbert had ordained that it was "much more advantageous to the colony that the inhabitants devote themselves to cultivating and clearing the land, rather than to hunting, which can never be of use to the colony." Colonization. long discouraged by its incompatibility with the fur trade, was at last really launched. Despite the insistence of French-Canadian historians upon contrasting a spiritual-minded New France with a materialistic New England, the French were the first great exploiters of the natural resources of northeastern America. Furthermore, the missionary effort of 1615-73 was closely related to the necessity of winning the support of the Indians, whose good will was vital to the fur trade, the economic lifeblood of the colony. Fortunately the French had fallen upon one of the three great natural entrances to the interior of the continent, a treasure house of the furs then so much in demand, and their search for the Western sea and a route to the Indies made available for exploitation natural resources almost as rich as the Spanish mines to the south. New France was not primarily a mission field, as the French-Canadian historians suggest, but the scene of a commercial enterprise conducted by Frenchmen from

8 - THE FRENCH· CANADIAN OUTLOOK

France for the material benefit of Old France. On the other hand, the Engl ish colonists to the south had turned their backs upon their mother country, and, checked by the Appalachian barrier from immediate penetration of the continent, had set about the creation of a New England by a colonization effort which dwarfed that of the French. Only later, after that foundation had been securely laid, did they turn to trade overland with the Indians and by sea with the West Indies and the French colonies, neglected by a European-minded monarchy which nonetheless insisted on keeping complete control of colonial development. Colbert was the first great French mercantilist, and at his behest Truon attempted to stimulate Canadian economic activity in fields other than the fur trade, and to develop a measure of self-sufficiency in the colony, while avoiding competition with the mother country. But Talon was soon distracted by dreams of a great empire dominating all North America, and he failed to heed Colbert's warning that it would be better "to restrict yourself to an ext~nt of territory which the colony will itself be able to maintain than to embrace so much land that eventually a part may have to be abandoned." The longdelayed consolidation of the St. Lawrence settlements suffered from an expansionism which laid claim to all the hinterland beyond a great crescent stretching from the mouth of the St. Lawrence to that of the Mississippi. The English settlements were hemmed in on the Atlantic seaboard by the French claims, which moved Governor Dongan of New York to remark: .. 'Tis a bard thing that all Countryes a Frenchman walks over in America must belong to Canada." Yet there were only some seven thousand people in Quebec, and less than five hundred in Acadia by 1675, despite royal encouragement of immigration, early marriage, and large families during the previous decade. 8 There were not then, and never were to be, enough men to implement the French claims to the vast expanses labelled New France on the map of North America. Between the Atlantic seaboard and the Appalachian barrier were confined the much more numerous and substantial Anglo-American settlements, and when the great struggle for the continent opened in 1689, two hundred thousand English faced ten thousand French. In the final stage. the Seven Years' War,

NEW FRANCE - 9

two million Anglo-Americans were arrayed against seventyfive thousand French North Americans. The simple facts of population, plus the influence of recently developed British sea power, settled the fate of New France. Only the audacity of French leadership, the use which the · French made of Indian allies to supplement their scanty numbers, and their technical superiority at forest warfare - an invisible asset developed by exploration and the f ur trade enabled them to delay the fin al decision for as long as they did. Despite the daring efforts of Frontenac, Iberville, and a host of lesser partisan leaders, the major factor contributing to the long-delayed decision was the disposition of almost all the Indian lribes except the Iroquois Confederacy to side with the French, who from both religious and commercial motives had always cultivated the friendship of the Indians, whereas the Englisb had sought chiefly to exterminate them. From the beginning the French were dependent upon the Indi ans, who guided their explorations and acted as middlemen in the fur trade; whiJe the English, intent at first upon agricultural colonization, warred relentlessly upon the ancient occupants of the land, and developed Indian alliances only when they began to trade west of the Appalachian barrier. For commercial reasons Champlain was forced to incur the eomity of the Iroquois, whose savage counter-attacks almost destroyed New France in its infancy and whose potent aid enabled the English to develop along the Hudson and Mohawk Valleys a rival trade route to the St. Lawrence .

• Two thousand settlers, largely (rom the no rthern and western p rovin ~ of France, were sent out to Canada in the decade ruter 1663, many of them veteran soldie rs wbo were induced to become colonists by special concessions. Colbert, through T alon, told the people that "their prosperity, their subsistence, and all that is dear to them depend UraD a general resolution, never (0 be departed from, to many youths a t eighteen or nineteen years and girls at fourteen or fi£leen." Bachelor· dam was penalized, while early marriages and la rge families were rewarded. Shiploads of carefuUy selected poor ar orPhaned royal wards were sent out 10 provide wives in a land where while women were rare. Thus was established the F rench-Canadian tradition or early marriage and large families . one of the strongest forces in the remarkable vitality o r this people. Though Ii:abilities in the m other country, large families were assets in the expanding economy of New France, which was an agricullural rather than an industrial society, and bad land 10 spare.

10 - THB FRENCH·CANADIAN OUTLOOK

Because the early history of French Canada was for many years written exclusively by clerics, the reJigious basis of the French tie with the Indians has been overstressed at the expense of the economic and political factors; yet even when this is taken into consideration, the religious influence remains obviously strong. Schools and hospitals in New France were open to savage and white alike - the French had none of the English colour prejudice - and the missionary effort of the French completely overshadowed that of the English colonies. In return the semi-Christianized Indians became useful allies to the slender French forces in time of war. French missionaries, particularly in Acadia, developed a curious confusion of nationalistic and religious motives, which did nothing to calm the "anti-popery" agitation so prevalent in the American colonies in the eighteenth century. The New England settler felt he had no greater enemy than the mission Indians who sacked the frontier villages under French leadership, and when opportunity offered. he returned the compliment, as Robert Rogers did at St Francis with the aid of the Stockbridge Indians. By the early years of the eighteenth century New France had developed a social organization very different from that of the mother country. It was an adaptation of the Frencb tradition to the North American way of life. The basic social unit, in the absence of institutions of local government, was the parish, which had much of the same primary importance for its inbabitants as tbe New England township. Talon's model villages near Quebec, based upon the nucleated type long traditional in France, did not meet the needs of the colonists, who evolved their own pattern of settlement. The use of watecw'ays for transport and communication, the necessity of close settlement for defence against the Iroquois, and the gregarious nature of the people combined to give the French-Canadian village its special arrangement. Land holdings were laid out in long narrow strips stretching back from the river, while the houses were set close together along the river, and later the road, which connected them with the church and presbytere (rectory) which were the communal centres. The cures, who were the only educated men in many districts, since many seigneurs were nonresidents, assumed a number of nonclerical functions, such as dispensing unofficial justice, conducting schools, and

NEW FRANCS - 11

drawing up notarial acts for the disposition of property.' Thus they acquired an unrivalled -prestige and influence in their parishes; and thus the theocratic tradition was reinforced. The State sought for its own ends to give the cures permanent status as in France, but Bishop Laval and his successors insisted on making them subject to recall at the episcopal will. In the absence from the parish of any secular official except the militia captain, who like his New England counterpart had certain judicial and administrative functions as well as military ones, the Church was in closer touch with the people than was the State. The stubborn individualism of the original settlers thus survived, while the self-sufficient family did not favour the growth of public spirit. Much has been written of the feudalism of New France, but actually the seigneurial system developed along new and only semifeudal lines in the colony, where the environment was so different from that of France. The society of New France was not stable and closed, but constantly evolving, and the social ladder was available to anyone who had the energy and the will to climb it. The seigneurs were by no means all of noble birth. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, habi· tants held a third of the seigneuries, and many others belonged to ecclesiastical corporations, officials, and merchants. No seigneur could live in idleness on his small rents and feudal dues, which often went unpaid as the habitants developed an independence of spirit, as well as a degree of prosperity, not commonly found among French peasants. The French·Cana· dian habitant was as different from the French peasant as the New England settler from the English tenant farmer. The Semi· nary of Quebec, the Jesuits, and the Sulpicians were the most successful seigneurs, for they carried on the work of settlement and agricultural development without the interruptions caused by the secular seigneur's frequent participation in the expeditions aga inst the English or the Iroquois and by his efforts to get rich quick in the fur trade. Because the trade was the gold mine of the colony, demanding neither capital nor training, and because a majority of the

'"

• Justice was (ree in New France, s.lnce lawyers werc banned from the colony, and notarics wcrc fcw.

12 - THE FRENCH-CANADIAN OUTLOOK

immigrants were soldiers, adventurers, and artisans rather than farmers, agriculture long languished and did not really come into its own until the eighteenth century. Not until the English took over the fur trade, and the call of the pays d'en haul (hinterland) waned, did Quebec become primarily an agricul~ tural region. It is part of the French-Canadian legend that this people displayed from the first a peculiar and dominant genius for agricultural pioneering, but only one and a half acres were cleared in the fint twenty years of the colony's life, and in 1754 almost a quarter of the population was urban, while the officials were striving to check the still-growing movement toward the towns, as they had tried to check the earlier dispersion of the colonists over the great network of fur-trading routes and posts in the interior of the continent, where coureur-de-bois and voyageur led a life very different from that sanctioned in the theocratic settlements of Quebec, Trois-Rivieres, and Montreal. During the thirty years of armed truce from 1713 to 1744, the governor and intendant sought to develop a broader and more stable economy than that which had prevailed under the fur trade's customary cycle of poverty and plenty. But official corruption, the shortage of manpower and capital, the difficulties of communication and transport, and absen tee control all combined to prevent success in this effort. Isolation, indignation against grafting by French officials and profiteering by French merchants, the absence of any share in the government. and the differences between a new and old culture all contributed to the development of sbarp distinction and ill feeling between French Canadian and Frenchman. This split first became evident late in the seventeenth century, grew rapidly. and, with the rivalry between Montcalm and the Canadianborn Governor Vaudreuil, played its part in the final downfall of New France. There were really only two classes in New France: the ruling elite, made up of transieDt officials, of a clergy still largely recruited from France, and of the noble seigneu rs; and the mass of the people. The elite were French, or French by adoption; the people called themselves Canadians, were jealous of Frenchmen, and felt no great loya lty to a government in which they had no part ex.cep t to take orders. This social division was to survive tenaciously in French Canada, and to set it apart

NEW FRANCE - 13

from English-speaking North America, whose greatest social strength lies in a dominant middle class which has no counterpart in the traditional French-Canadian scheme of things, and in a democratic way of life distinct from the hierarchical society evolved in the New France of Louis XlV and Bishop Laval.

2.

The Meeting of French and English -:t -:t -:t

1760-1790

An important part of the French Canadian's special outlook arises from bis consciousness of belonging to a conquered, or at least a minority, people. He may deny this, and is sure to protest that his ancestors were abandoned by the French ratber than conquered by the English, whenever some arrogant "Anglo-Saxon" prefaces a denial of French-Canadian claims with: "After all, we conquered you." But the state of mind, conscious or unconscious, is still there, for the French Canadian is encircled by an Englisb-speaking world which clashes with his owo in many respects, and he is constantly reminded that it was not ever thus. Historical teaching in Quebec, with its undue emphasis on the French period and the difficult years from 1760 to 1867, when the French Canadians were struggling for survival as a distinct group, is largely responsible for the prevalence of this state of mind and for all the accompanying manifestations of an inferiority complex, including an emotional opposition to anything "Anglo-Saxon" and a preference

THE MEETING OF FRENCH AND ENGLISH -

}j:

for values which may be considered "French." That is why the French Canadian is still preoccupied today with the problem of survival, long after survival has been assured; why he is still on the defensive, and consequently inordinately sensitive to any threat to his cherished faith, language, laws, and customs, when

these are so firmly established that they actually represent a threat, in some regions bordering on Quebec, to the equally cherished cultural complex of his compatriots of different origin. The period of transition from French to British rule is naturally rich in divergent interpretations. The French Canadian remembers with pride Montcalm's capture of Fort Witliam

Henry in 1757 and his defeat of Abercromby at Carillon (Ticonderoga) in 1758. Amherst's capture in 1758 of Louisbourg, the key to the S1. Lawrence, and Wolfe's victory on the

Plains of Abraham in 1759 are more familiar to the English Canadian. The latter is apt to forge t that Uvis defeated Murray at Ste. Fay and almost retook Quebec the following spring, before the appearance of a British fleet in the river and Amherst's advance on Montreal settled the fate of New France. While the change from French to British rule is referred to as the "Conquest" by English Canadians, it is called the "Cession" by French Canadians, as Southerners in the United States prefer "War Between the States" to "Civil War." French-Canadian

historians tend to paint the early days of British rule in dark colours which contrast sharply with the bright tints of their picture of New France. It is still possible to start a bitter con-

troversy in Quebec by pointing out that the British did Dot attempt to crush the French Canadians under the military government which lasted until the peace treaty became effective

in 1764, but on the contrary befriended them against the swarms of camp followers and Anglo-American commercial adventurers who descended upon Quebec like a cloud of locusts. Murray, with the professional soldier's contempt for militiamen and traders, resented the "most inveterate fanaticks" from New England and New York, and soon sent home the American militiamen who were most imbued with "anti-popish" feeling, as well as ~vith a hereditary hatred of their northern neighbours - antagonisms born of years of bitter border warfare. The Engl ish troops and the French Canadians lived together

16 - THE FRENCH -CANADIAN OUTLOOK

"in perfect harmony and good humour" - witnessed by the prevalence of intermarriage - in the midst of the misery which

war had brought. Quebec City stood shattered after two months' bombardment; the lower St. Lawrence had been systematically devastated by the conquerors as they advanced; and the com-

mercial classes were ruined by the French legacy of $8,200,000 of inflated paper money on which payment had been suspended,

and which was only partially redeemed years later. The old economy of the colony was shattered by the amputation of

Labrador and the North Shore, which were attached to Newfoundland, and of the western hinterland, which was established as an IndiilD reserve. The position of the French Canadians was indeed desperate, and few contemporaries would have wagered much on their national survival . The New France which had been so utterly dependent upon the mother country throughout its existence was now separated and isolated from the France which had supplied its rulers, its apostles, its educators, its ideas, and its books. If the French Canadians were to remain French under the aegis of a foreign power whose language, religion, laws, and customs were very different, they would have to do so on the strength of their own resources. This foreign power had been the traditional enemy of the conquered people ever since the first seeds of settlement had been sown, and might have been

expected to exploit its victory to the full. But the peaceful transition of Quebec from French to British rule is noteworthy today, when whole peoples have been ruthlessly suppressed by their conquerors. Pending the determination of the peace, the victors showed remarkable tolerance toward the faith, laws, and customs of

the French Canadians. Though eighteenth-century England was strongly "anti-papist," the practice of the Catholic religion was not interfered with, save that recruiting by the Jesuits and the Sulpicians was forbidden, and the large estates of the former order were impounded . Government was carried on through the old institutions in French, with the military governor filling the roles of both governor and intendant under the old regime, and with the French-Canadian militia captains acting as local magistrates. All went so smooth ly that few besides French

THE MEETING OF FRENCH AND ENGLISH - I7

officers and officials took advantage of the privilege of returning 10 France which was given 10 them by the treaty.' When civil government was established in 1764, with the avowed program of remaking an old French colony into a new English one, Murray tempered the wind to the shorn Iamb. Since an anti-Catholic form of oath was required, the governor was obliged to form a cou ncil whose members were drawn largely from the army, though they soon became known as the "French parly," because of the sympalhy they displayed for the natives of the country. Judges, magistrates, and jurors also had to be chosen from among the British officers and merchants, according to Murray's instructions, and the only participation by the people in government which had developed since the conquest - the justice of the peace function of the militia captains - was thus eliminated. All these measures had the effect of uniting the French (who had assumed the role of "havenots") aga inst the British (who had become Ibe "haves"), and of reviving that "nation ~ l antipathy" which Murray had congratulated himself on eliminating during the period of military rule. But the governor, refusing to call an assembly in which only English merchants could sit, because of the anti-Catholic oath required, sent one of his Swiss aides, Cramahc, to London to urge a revision of policy in the interest of the French Canadians. In 1765 the law officers of the Crown decided that the anti-Catholic penal laws of England did not apply in Canada, while the Privy Council ordered that all discrimination against Canadians as lawyers or jurors should cease. In the following year a thorough revision of the judici3l system was drafted in London, after the law officers had condemned an administration of justice "without the aid of the natives, not merely in new forms, but totally in an unknown tongue," and the attempt to abolish "all the usages and customs of Canada with the

I

The legend of a wholesale exodus of the t:lite has long since been shatlered. (Cr. J udges Georges Baby, L'Exode de: cJasleJ dlrlgeante: d la cession du Canada, Monneal, 1899. ) But it is lJ"ue that of the t:lite only the clerg:y maintained its prestige undiminished by the conquest. Contrary to a myth on which rests the tremendous innuence of the clergy in French Canada, it was not they but the merchants who took the lead in the struggle for national survival.

18 - THE FRENCH -CANADIAN OUTLOOK

rough hand of a conqueror." Though reform in Canada had to await the outcome of English political struggles, Murray's behaviour as governor did much to father the great Quebec legend that Scots are sympathetic to the French Canadians, while the English are racial enemies. 2 Guy Carleton, Murray's Anglo-Irish successor, had the natural sympathy of a professional soldier and a member of the landed gentry for a semifeudal society; so he was gradually drawn to the "French party" in the council, after favouring at the outset of his administration the British merchants who had brought about Murray's recall. His hatred of graft and corruption led him to reform the system of fees by which, in lieu of salaries, officials were remunerated. This system had caused great discontent among both French and English, for under the old regime justice had been free, while the merchants were exasperated by exactions which surpassed anything they had ever known, either in England or in the American colonies. Carleton continued Murray's policy of refusing to call an assembly, despite the merchants' agitation for one. He agreed with his legal adviser Maseres, a brilliant Huguenot with a strong anti-Catholic bias, that the Canadians did not desire an assembly which was totally foreign to their traditions, and that it was eagerly sought only by the "English adventurers" for whom neither official had much regard. Carleton, whose wife had been brought up at the court of Versailles, saw New France through eyes blurred by impressions of the old. Aristocratic and autocratic himself, be regarded the seigneurs and clergy as the real leaders of the French Canadians, and tried by favouring them to establish a feudalism which had never existed in Canada. He proposed that "three or four of their principal gentlemen" should be added to the council, and that French-Canadian military units should be formed, for "as long as the Canadians are deprived of all places of trust and profit, they can never forget tb at they are DO longer under the dominion of their natural sovereign; tho' this immediately concerns but few, yet it affects the minds of alt, from a national spirit whic.h ever interests itself at the general exclusion of their countrymen." This group consciousness, which Carleton remarked so soon after the conquest, has remained a vital factor in the French-Canadian mentality down to the present

THE MEETING OF FRENCH AND ENGLISH - 19

day. London long displayed an ability to make use of it by such measures as Carleton suggested, whenever crises arose in Canada. Today, whenever Ottawa neglects this technique of government, it is urgently reminded that Canada is a nation made up not of one people but of two. Carleton also secured the support of the Church by approving the nomination of a Canadian-born coadjutor bishop, with the right of succession to Bishop Briand, whose consecration had been favoured by Murray, though no Catholic bishop was then tolerated in England. Murray had recognized the vital role of the Cburch in the French-Canadian world; Carleton saw the opportunity to attach the Canadians to Britain by reversing the old preference shown to priests of French rather than Canadian origin. By this step and by restrictions on the immigration of new priests from France, he removed the possibility of French ecclesiastical domination in Canada after French political rule had ceased. But in his preoccupation with clergy and seigneurs Carleton neglected the welfare of the mass of the people. This was assured by the Quebec Act of 1774, whose origin lay in Murray's protests against the system established in 1764, but which was the work of many minds, both in Canada and in England. The threat of war with the colonies and their possible secession precipitated the Quebec Act, but did not cause it, as the Americans assumed when they learned that the OhioMississippi hinterland, now becoming of interest to them, was restored to Quebec, that the French Canadjans were granted the whole of their civil law, almost to the exclusion of English common law, and that the Catholic Church was virtually established in Quebec, while representative government was withheld. These measures in favour of their ancient enemies irritated the Americans almost as much as the penal acts which the same parliament passed against the seaboard colonies, then smoldering with rebellion. England retained her hold upon the portion of North America which was to remain British by allowiog it to remain both French and Catholic, but by doing

.

I

The assimilation by the French Canadians of the Hlahlanders. who were settled ::dler the conquest at Murray Bay and Rivl~re-du-Loup to secure the St. Lawrence, also played an important part in the development of this leaend.

20 - THE FRENCH-CANADIAN OUTLOOK SO she revived the old sectional rivalry of the American Hundred Years' War. It was not wholly a coincidence that the American Revolution entered the phase of organized violence at Lexington and Concord two weeks before the Quebec Act took effect. The Quebec Act is the Magna Carta of the French Canadians. It revoked the whole tentative system of civil, judicial, and ecclesiastical government launched in 1764 with the aim of assimilating the French Canadians in an English colony governed under English law in English fashion. Catholicism was no longer tolerated out of expediency; Catholics were assured the free exercise of their religion, which was no longer to be an obstacle to their preferment to any office or position, since a new form of oath was provided which offended none of their principles. The Catholic clergy were assured their rights and dues from Catholics, while the- tithes of nonCatholics were to be devoted to tbe support of a Protestant clergy.s All disputes relating to property and civil rights were to be determined according to the "laws and customs of Canada," the old French civil law derived from Roman days, although the Crown retained the right to grant lands under the English rather than the French system of tenure, and wills might be made according to English law if so desired. On the other band. the English criminal law was estabJishcd, to the exclusion of the French. Since it was still judged "at present inexpedient to can an Assembly," the power to legislate for the peace, welfare, and good government of the province was given to an enlarged council, acting with the consent of the governor, and subject to the approval of the home government. A separate bill, the Quebec Revenue Act, established a schedule of duties and license fees to be applied to the support of the civil government and the administration of justice." Thus, within a decade after the cession of Canada to Britain - as an alternative, incidentally, for the island of Guadeloupe - the survival of the French Canadians as a separate cultural group was assured. Of the four cherished essentials of survival, only the question of language was left unsettled. It really had not yet arisen, save in the courts, for before the Quebec Act, as after it, "all proclamations were published in both French and English, and ordinances were

THE MEETING OF FRENCH AND ENGLISH - 21

passed in the same manner."s Since French was the only language understood by all the members of the new council, debate was carried on in that tongue, although minutes were kept in English. This situation, and the increased power of the Crownappointed council, added to the grievances of the AngloAmerican merchants, who bewailed being deprived of such traditional English rights as the habeas corpus, trial by jury, English mercanliJe law, and representative government. For the withholding of an assembly, the unruly behaviour of the American colonies was as much to blame as the lack of French-Canadian interest in representative government. The merchants' demands for an assembly had a tone which in London smacked too much of the seditious sentiments rife in the American representative bodies. Then, too, the French Canadians, who in the first decade after the conquest had attained the highest birth rate ever recorded for a white people, while tbe English rem ained a minute minority, could not fairly be excluded from an assembly; and London was not anxious to entrust power to a newly conquered people, when colonies whicb had been British from the beginning were seething with revolt. According to the governor's secret instructions, many of the merchants' grievances were to be appeased by a gradual modification of the French laws through ordinances of the council; but pending this process, the merchants' "strong Bias to Rep ublican principles," which Carleton had noted with distaste, was reinforced. Their loyalty was soon tested and found wanting during the American invasion of 1775-6; while the seigneurs and clergy. whose position was reinforced by the Quebec Act, displayed their gratitude by the notable part they played in resisting that effort to make Quebec tbe fourteenth American colony.

'*

'The tithe had been fixed in Canada since 1667 :1S one twenty-sixth of grain crops. The rate was thus (wo and a half times less than that in Britain, where all produce of the land and the profits of personal industry were subject to a t.'lX of one-tenth. 'This was the first step in the introduction of taxation, which was foreign to the tradition o f the French Canadians. Under the old regime, save during the last decade, they had paid no direct taxes, the expenses of the colonial administration being in part offset by the income from the monopolits of the fur trade and fisheries, which were farm ed out. 6 A. L. Burl, The Old Province 0/ Qu.ebec (Minneapolis, 1933), p. 238.

22 - THE FRENCH-CANADIAN OUTLOOK

Much has been made by French-Canadian historians of how their people saved Canada for Britain in 1775-6, but actually the masses, none too pleased by the Quebec Act's resanctioning of tithes and feudal dues which to some extent had fallen into disuse since the conquest, assumed a neutral role. Their bias was affected by the varying fortunes of the opposing parties in what must have seemed an "Anglo-Saxon" family quarrel to a very newly British people. Some habitants were won to the American cause by the Congress' propaganda and by the agitation conducted by Anglo-American merchants of Montreal; more were impressed when Ticonderoga, Crown Point, and St. Johns, the bastions of the traditional invasion route, fell rapidly into American hands. Others remembered the antiCatholic fanaticism of their ancient enemies the Bostonnais, and this consideration had much to do with keeping the majority neutral, particularly when it was reinforced by the clergy's and seigneurs' demonstration of the bypocrisy of Congress, which made a violently "anti-popish" protest to England against the Quebec Act just five days before it appealed to the French Canadians to join in a peaceful union of Protestants and Catholies against British tyranny_ Bishop Briand echoed Carleton's call to arms in a pastoral letter, but the popular response was not enthusiastic. Disgruntled habitants remarked that the bishop's function was to make priests and not militiamen, while the overzealousness of Anglophile seigneurs in recruiting defeated their object and brought on local revolts against mobilization. The American-minded Montreal merchants did not fail to point out to the perplexed habitant that he would be breaking the oath of loyalty taken after the conquest if he bore arms against the invaders, who were lumped with the English as "les Anglais" in the popular speech. At the base of the people's neutrality was the fact that the French Canadians were worn out by a century of continental warfare against heavy odds, when all men between sixteen and sixty had been liable for military service, and by the long effort to explore a continent and carry on a continental trade with inadequate manpower. The greater number of them had become sedentary folk whose world was bounded by the parish limits, who were deeply attached to their land and wished only to dwell on it undisturbed by war. This attitude has long remained

THE MEETING OF FRENCH AND ENGLISH - 23

part of the French-Canadian mentality, and the roots of modern opposi tion to conscription may be found in the resistance to mobilization in 1775. Two French-Canadian regiments were raised by the Americans, however, among the habitants of the Richelieu Valley, with its militant tradition established by the Carignan-Salieres soldier-pioneers, while numerous militiamen in Montreal and Quebec espoused the loyalist cause. Neither leader was under illusions as to tbe general sentiment of the French Canadians; Carleton observed : "I think there is nothing to fear from them while we are in a state of prosperity, and nothing to hope for while in distress," wh ile Montgomery, the American leader, judged that they "will be our friends as long as we are able to maintain our ground." When the tide turned against tbe Americans after the unsuccessful assault on Quebec on New Year's Eve, and friction arose between the invaders and the people most notably when cash ran out and the Americans resorted to requisition or payment in inflated paper all too reminiscent of the French regime - French-Canadian support gradually shifted to the British side. Benjamin Franklin met one of his rare diplomatic defeats in Montreal the following spring when he attempted to win back French-Canadian sympathies, while his colleague, the French-educated Jesuit Father John Carroll, was repulsed by the rigidly loyalist clergy, who had refused the sacraments to American sympathizers. The headlong American retreat after the arrival of British reinforcements at Quebec brought out the largest number of French Canadians who had yet demonstrated their loyalism by volunteering; but Carleton had lost confidence in them, and annoyed the loyalists by making no distinction between them and American sympathizers. With the Franco-American alliance of 1778, and the constant threat of a joint expedition against Canada from then until the end of the war, Quebec was troubled by the intrigues and the propaganda of American and French sympathizers; and relations between British and French were poisoned by a suspiciousness which strengthened the "national antipathy." Carleton was replaced in 1778 by Haldimand, the Swiss military governor of Trois-Rivieres after the conquest, a man who did Dot have his predecessor's confidence in the loyalty of the clergy and the seigneurs under the altered circumstances. He deported

24 - THE FRENCH . CAN'ADIAN OUTLOOK

one French Sulpician who advocated Canada's return to France and two others who bad entered the province in disguise; and he jailed a handful of French-born notables whose eloquent protests have given him an unjustified name as a bigot and a tyrant. Yet Haldimand, whose mother tongue was French, saw that French and English might be drawn more closely together in Canada if their cultures were shared, and so be established the first public library in Canada, half English and half French in its contents. G This French Swiss considered the Canadians "bigoted in their laws and usages," and accused the clergy of an "attachment for France, concealed under their zeal for the Preservation of their Religion." Haldimand's Protestant bias must be discounted, but there is evidence of a certain con~us ion by the French Canadians of mild racism and nationalism with religion, a confusion which was to increase with the years. It was a natural reaction to the prevailing "anti-popish" attitude of the English-speaking world, and its development was fostered by the fact that the lower clergy were active in the FrenchCanadian struggle for survival as a separate national and cultural group. In terms of the racist mythology which later developed in Quebec, it is one of the ironies of history that the autocratic absolutism of the "French" Haldimand furthered the development in Quebec of the "Anglo-Saxon" democratic ideas implanted during the American invasion. The French Canadians united with the British merchants to bring about his recall, and with the return of Carleton (now Lord Dorchester) a new stage of Canadian development began. Actually it was not the governor, but the chief justice, the American Tory William Smith, who was the chief figure in the new administration. Smith, who had been chief justice in New York when Carleton was commander-in-chief there, drafted a plan for the reorganization of what remained of the British colonies after the peace treaty of 1783. H~ urged a united British North America, with Carleton as viceroy, a more powerful council, and an assembly, with the Quebec Act retained for the time being. Smith, who had seen peoples "addicted to foreign laws and usages and understanding none hut a foreign Janguage" absorbed to the English way of life in the American colonies, was confident that the French Canadians could like-

THE MEETING OF FRENCH AND ENGLlSH - :u

wise be assimilated. The influence of such Tory American loyalists as Smith, Jonathan Sewell of Massachusetts, and Sir John Johnson of the Mohawk Valley, who were rewarded for their loyal ism by high office in Canada, has been somewhat neglected. Like the Bourbons, they learned nothing from revoluti9n and forgot nothing; in Canada they followed the tenets of the autocratic system in which they had been bred, and provoked the same popular reaction. Their early environment was anti-French and anti-Catholic, and the attitudes engendered by these influences, united to their political creed, hardened the division between English Protestants and French Catholics, between the haves and the have-nots. Another Canadian aftermath of the American Revolution was the split created between the elite, who clung to the old order restored by the Quebec Act, and the masses, who had been deeply influenced by the American doctrines of democracy, liberty, and the self-determination of peoples. Perhaps the most important contribution which the American Revolution made to French Canada was the introduction into Quebec of some seven thousand American loyalists - professed loyalists at least, though undoubtedly the loyalty of many was merely to the free lands and special concessions offered them in Canada.' Their number, which continued to increase until 11l 15, amounted to nearly a tenth of the French Canadians. They did not settle among the old inhabitants, except at

• The French-Canadian legend that Canada never felt the influence of Voltaire and the Encyclopedists has been disproved by the discovery of their works in Quebec libraries both before and after the c.onquest. The semiofficial and bfHngual Quebec Gatette, established in 1764, frequently printed selections fro m these authors, :1nd a Volt:1irean :1cademy flourished in M ontreal in 1778. Voltaire, Rousseau, and Montesquleu were widely read in both England and Amerie:1 nt this period, and their vogue in Quebec. c.annot be considered, as sometimes nlleged, an English conspiracy to win the French Canadians from their faith . These authors were not really frowned on in Quebec until the middle of the nineteenth century, when a new tide of Jansenistic and conservative reaction set in, after the social consequences of their doctrines had become apparent to the clerical leaders of the French Canadians. Cf. Marcel Trudel, L'!n{luence de Voltaire au Canada (Montreal, 1945) . , Major Andres executioner was discovered taking out land at Kingston as a loyalist.

26 - THE FRENCH-CANADIAN OUTLOOK

Sorel. but rather along the hitherto unsettled upper St. Lawrence, the southern Gaspe coast, and later in the Eastern Townships, a natural extension of the Vermont and New Hampshire from which many of them came. Their coming completed the conquest of New France: Canada was not to be French. but French and English. Their demand for British institutions also caused the virtual repeal of the Quebec Act by the grant of representative government and the division of British North America into Upper (English) and Lower (French) Canada. 8 The new constitution, drafted in traditional terms by the English Tories, took effect in 1791 and was greeted by French and English alike at public dinners where such untraditional toasts were drunk as "The French Revolution, and true liberty throughout the universe," "The abolition of the feudal system," and "The Constitution, and may the unanimity among all classes of citizens cause all distinctions and prejudices to disappear, make ilie country flourish, and render it always bappy."

• This terminology was later dropped, but the stubborn persistence of the psychological attitudes appropriate to it bas aroused much ill feeling in Quebec.

3.

Two Peoples Make a Nation ..., '*' ..., 1790-1867

The differences between French and English Canadians were Dot to subside with the coming of representative government, but rather to increase. The French were offended by the incongruously English names given to the twenty-one counties

into which Quebec was then divided. The first elections produced some ethnic strife, and more arose from the fact that the English population, a fifteenth of the total, had almost a third of the seats in the assembly and a majority in both the legislative and executive councils. The French-Canadian mem-

bers of the two latter bodies were carefully chosen among anglophilc seigneurs and those dependent on the government. Their interests were by no means those of the popular majority in the assembly, which included habitants and representatives of the rising class of lawyers and notaries along with seigneurs

and merchants. There was friction in the assembly over the election of a speaker and over the official use of French, but after a sharp struggle a French speaker was elected and

28 - THE FRENCH-CANADIAN OUTLOOK

bilingualism was recognized in fact, although it did not attain full legal status until Confederation. Thus representative government was used at the outset by the French Canadians to insure the last of the essential conditions of their national survival: the free use of their language in the official world. French and English party spirit soon developed, with English dominance in the councils offsetting French control of the assembly. Division along English vs. French, and Protestant vs. Catholic, lines was fostered by the development of the "Chateau clique," a group of placemen from England and American Tories, who proceeded to feather their own nests from the public funds and Crown lands under a smoke screen of pious loyalism . Suspicion was cast by these highhanded worthies upon the French Canadians as J acobins and potential traitors because their origin was the same as that of the French of revolutionary and Napoleonic France, who aroused intense alarm in England. The French Canadians merely sought to obtain the rights of British subjects through the unfamiliar institutions of representative government, which they came to interpret more and more as the Americans had done. There was a major cultural conflict between the English, who wanted state-controlled schools, and the French, to whom education was a religious matter which should be left to the Church, as in the past. A lasting source of contention between tbe two groups was created in 180 I by the diversion of the revenues of the Jesuit estates (traditionally devoted to educational purposes) actually to the general government funds. althougb nominally to the support of the state-controlled school system devised by the Anglican Bishop Mountain under the name of the Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning.) The conflict between the popular majority on the one hand and the alliance of the "Chateau clique" and the merchants on the other resulted in the tragically long deferment of the establishment of a general primary school system. This conflict continued on many fronts, with the Tory oligarchy consistently trying to offset Pitt's effort in 1790 to give Lower Canada a government adapted to the customs and traditions of the French Canadians. In constitutional terms, it was a battle between the appointive councils and the elected assembly; in religious terms, a battle between the Anglican and Catholic

TWO PEOPLES MAKE A NATION - 29