Orphan Girl: The Olesnicki Episode: One Body with Two Souls Entwined: An Epic Tale of Married Love in Seventeenth-Century Poland (Volume 85) (The ... in Early Modern Europe: The Toronto Series) 1649590423, 9781649590428

A page-turner featuring one of literature’s earliest female protagonists. Written in 1685, Transaction or the Descript

129 87 3MB

English Pages 120 [121] Year 2021

Cover

Title Page

Contents

Foreword

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Orphan Girl: The Oleśnicki Episode

Commentary

Bibliography

Index

Series Page

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Anna Stanislawska

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

Anna Stanisławska

Orphan Girl:

The Ole´snicki Episode

VE R S E TR A NS L ATI ON, I N TR OD U CTI ON , A N D COMME NTA RY BY

Barry Keane

The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe: The Toronto Series, 85

ONE BODY WITH TWO SOULS ENTWINED

The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe: The Toronto Series, 85

FOUNDING EDITORS Margaret L. King and Albert Rabil, Jr. SERIES EDITOR Margaret L. King SERIES EDITOR, ENGLISH TEXTS Elizabeth H. Hageman

In memory of Albert Rabil, Jr. (1934–2021)

ANNA STANISŁAWSKA

One Body with Two Souls Entwined: An Epic Tale of Married Love in Seventeenth-Century Poland Orphan Girl: The Oleśnicki Episode •

Verse translation, introduction, and commentary by BARRY KEANE

2021

© Iter Inc. 2021 New York and Toronto IterPress.org All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America

This book has been published with the support of the ©POLAND Translation Program.

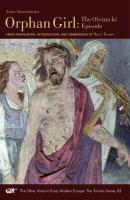

Publication co-financed by the Faculty of Modern Languages of the University of Warsaw. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Stanisławska, Anna, approximately 1651-1700 or 1701, author. | Keane, Barry, 1972- translator, writer of introduction, writer of added commentary. Title: One body with two souls entwined : an epic tale of married love in seventeenth-century Poland : Orphan girl : the Oleśnicki episode / Anna Stanisławska ; verse translation, introduction, and commentary by Barry Keane. Other titles: Transakcyja. Selections. English Description: New York : Iter Press, 2021. | Series: The other voice in early modern Europe: the Toronto series ; 85 | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: “The second of three parts of the unique verse epic account of her three marriages, this one, successful but brief, to famed military hero Jan Zbigniew Oleśnicki, by Polish author Anna Stanisławska”-- Provided by publisher. Identifiers: LCCN 2021021689 (print) | LCCN 2021021690 (ebook) | ISBN 9781649590428 (paperback) | ISBN 9781649590435 (pdf) | ISBN 9781649590442 (epub) Subjects: LCSH: Stanisławska, Anna, approximately 1651-1700 or 1701--Poetry. | Women poets, Polish--17th century--Biography--Poetry. | Wife abuse--Poetry. | Stanisławska, Anna, approximately 1651-1700 or 1701--Translations into English. Classification: LCC PG7157.S73 T7313 2021 (print) | LCC PG7157.S73 (ebook) | DDC 891.8/ 514--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021021689 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021021690 Cover Illustration The cover photo, the effect of a photogrammetric survey of the stuccowork to be found in the Church of the Holy Trinity in Tarłów (a village located north of Sandomierz in the south-east of Poland), has been kindly provided by the Sarmatia Virtualis Project (see sarmatiavirtualis.pl). Cover Design Maureen Morin, Library Communications, University of Toronto Libraries.

Contents Foreword

vii

Acknowledgments

ix

Introduction: One Body with Two Souls Entwined The Other Voice Historical Backdrop Stanisławska’s Early Life The Aesop Episode Oleśnicki A Sacral Legacy Old Poland’s Feminist Zeitgeist An Other (and Yet the Same) Voice: A Note on the Translation

1 1 3 6 7 9 13 14 17

Orphan Girl: The Oleśnicki Episode

19

Commentary

71

Bibliography

93

Index

99

Foreword A lost girl becomes a woman: A first night with a proper man, Who is impossibly handsome, Knowing bodily joy for the first time. (T. XXXIX, S. 357, ll. 5–8) After the experience of her first marriage, an arranged one to a monstrous degenerate, from which she escapes by extraordinary determination, good fortune, and the intervention of powerful friends, Anna Stanisławska will find “bodily joy” for the first time in a marriage to the man she loves—the magnetic, capable, and devoted Oleśnicki, close to her in age and rank and disposition. Here is the perfect end to a story that began badly: a consummation she has earned by the anguish she has suffered and the strength of her desire. It was not an easy road, however; and if we have a love story here in the second of the three episodes of Orphan Girl, the consummation is achieved only after a long series of sometimes comical obstacles are overcome. Those obstacles constitute almost a catalogue of the difficulties besetting those seeking to marry in the early modern world. First, the divorce—technically an annulment, possible because the first marriage (to a spouse who preferred masturbation) was not consummated—had to be finalized. Second, the realization dawns that the lovers are in fact related by blood within a prohibited degree, according to Catholic law, barring marriage—but a dispensation is acquired. Third, as the couple is about to marry, rumors arise that, if true, would rule him out as a spouse: it was said that he had murdered his first wife, and that, to boot, he had a venereal disease. Advised by Anna’s stepmother, they decide to wed nonetheless, fleeing busy Warsaw for a country village to be married by a local priest and to celebrate with a distinctly downscale banquet. And so consummation is achieved. Stanisławska, however, is not fated to be happy. A first disappointment is that the pair of them, however ardent their lovemaking, cannot conceive a child. Then Oleśnicki must go with the Polish army to the eastern borderlands to repel a Turkish invasion, where he performs heroically—and in the aftermath of victory breaks his marriage vows repeatedly with a harem of exotic “local girls.” He returns home, serves in the Polish parliament, or Sejm, then hies off to war again, until called home to tend his father who is seriously ill. There follows the greatest tragedy, and irony, of all: his father recovers, but Oleśnicki falls ill. And dies. And she is bereft; she has lost her lover, and “the ache will remain forever” (T. XLII, S. 464, l. 8). Still young, twice married, fiercely capable, Stanisławska manages the vii

viii Foreword funeral, inherits his property, and will move on: to a third marriage, a tale to be told in the third and final episode of Orphan Girl. In The Oleśnicki Episode, as in The Aesop Episode published in 2016 in the Other Voice series, Barrry Keane’s lucid, witty, and lyrical translation brings vividly to life a true-life story of love, betrayal, and loss from the European heartland more than three centuries ago. His annotations and commentary richly display, moreover, the distinctive social relations and political circumstances that are the dispositive context for this narrative centered on two compelling personalities whose experiences exemplify the restrictions suffered by those seeking to choose or to avoid marriage in a culture bound by traditional norms and religious law. MARGARET L. KING February 18, 2021

Acknowledgments Convinced that the story of Anna Stanisławska speaks challengingly to the uncertain times in which we all find ourselves living, I feel humbled and privileged to have been given the opportunity to continue with the next part of this exceptional poetic text. I have completed both the translation and its accompaniments largely thanks to the cajoling and encouragement of the ever-inspirational Margaret King, who has so generously steered this project through to completion. And also for their continued great efforts and support, I would like to express my sincerest thanks and appreciation to the wonderful Margaret English-Haskin and her production team. As always, I greatly value the encouragement I have received from my department colleagues, Aniela Korzeniowska, Agnieszka Piskorska, and Dominika Oramus, who have helped me in innumerable ways over the years; and I would also like to mention the unwavering support, friendship and guidance of John Dillon and Michael Cronin of Trinity College, Dublin. A special thanks also to friends Tom Galvin, Mick Kenny, Iain Haggis, and Paul McNamara for their reading of scraps and chunks of the manuscript; their ‘keep going’ meant a lot. I must also make a special mention of my mother, Vera, living in Bray, Ireland, and being devotedly looked after by my sisters, Lynn and Orla, and my brother, Declan. At this time of writing, I can only express the hope that I will get home to see them all soon, and when it is safe to do so. With love and thanks to my wife, Agata, and our girls, Julia and Karolina, who are the positivity notes of every day and the inspiration and restorative joy at the heart of everything I do. With sincerest thanks to the Polish Book Institute and the Faculty of Modern Languages of the University of Warsaw for their funding support of this publication. And this gratitude extends also to Karol Czajkowski of the Sarmatia Virtualis Project, who so kindly made available to me the image of the “Family and Death” painting from the Church of the Holy Trinity in Tarłów, which is featured on the front cover of this book.

ix

Introduction: One Body with Two Souls Entwined The Other Voice In 1685, the once-divorced and twice-widowed Anna Stanisławska (1651–1701) sat down, most emblematically and figuratively, to write out in verse an extended autobiographical poetic work entitled Transaction or the Description of the Entire Life of an Orphan by Way of Plaintful Threnodies, Written in the Year 1685—with its abbreviated title for this and the previous publication being Orphan Girl.1 By this undertaking, Stanisławska would engage in the writing of “terrible verses,” where line after line, rhymed octet after rhymed octet (745 of them, each verse with a syllabic meter of eight), she spoke confessionally and unsparingly about her life, from infancy—the remembrance of the loss of her mother—to the hour when she was standing over the open grave of her third husband, feeling faint from an overwhelming sense of grief. The poem is divided into seventy-seven episodes, each titled “tren,” meaning “trenos” or “threnody” (best understood as a dirge or funerary lament). These threnodies differ in length, as the number of octets constituting each varies.2 Also unique to this work is the fact that a quarter of the octets have brief margin glosses located on their left on the manuscript pages, glosses which illuminate what can often be an impenetrable text.3 What is more, the work is bookended by opening and closing poems to the reader. The opening poem, twenty lines long, is notable for its assertion that this work contains a feminine perspective. The closing poem, twelve lines long, is striking for the heartbroken declaration that there is nothing left to live for; and that Stanisławska’s existence as a desolate widow is but a living state of death. 1. Transakcyja albo Opisanie całego życia jednej sieroty przez żałosne treny od tejże samej pisane roku 1685, ed. Ida Kotowa (Kraków: Polska Akademia Umiejętności, 1935). A later edition exists of the Transakcyja, subtitled Fragmenty (Fragments), ed. Piotr Borek (Kraków: Universitas, 2003). English translation: Orphan Girl: A Transaction, or an Account of the Entire Life of an Orphan Girl by Way of Plaintful Threnodies in the Year 1685: The Aesop Episode, ed. and trans. Barry Keane (Toronto: Iter Press; Tempe, AZ: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2016). 2. For discussions of the poem as a lament, see Magdalena Ożarska, “Combining a Lament with a Verse Memoir: Anna Stanislawska’s Transaction (1685),” Slavia 81 (4) (2012): 389–404; and Halina Popławska, “ ‘Żałosne treny’ Anny Stanisławskiej” (“The Doleful Laments” of Anna Stanisławska), in Pisarki polskie epok dawnych (Polish Women Writers of Olden Times), ed. Krystyna Stasiewicz (Olsztyn: Wyższa Szkoła Pedagogiczna, 1998), 89–111. 3. In this translation, the margin notes are to be found on the right-hand side of the poem. For a discussion about Stanisławska’s employment of the glosses, and their potential function, see Magdalena Ożarska “Reading the Margins: The Uses of Authorial Side Glosses in Anna Stanisławska’s Transaction (1685),” in Self-Commentary in Early Modern European Literature, 1400–1700, ed. Francesco Venturi (Leiden: Brill, 2019), 369–94.

1

2 Introduction In terms of its biographical sweep and historical perspective, the ambition of this poem is distinguished by the fact that it was written as an emancipatory act of declarative mourning with a woman’s sensibility for a life that Stanisławska herself regarded as having come to its expiration. The widowhood she chose to embrace for the rest of her days—a widowhood begun in her mid-thirties and embraced by the writing of this poem—would be characterized by a life of patronage, good works, court battles over property, and ultimately a cantankerous withdrawal from the world.4 The work, never published and perhaps solely written as a cathartic exercise, was lost to posterity for centuries, having never in fact seen the light of day. In 1890, while pursuing research in the archives of the Imperial Public Library of St. Petersburg, the Polish Slavic scholar, Aleksander Brückner, discovered the manuscript; revealing to the world three years later that the author of his discovery was Anna Stanisławska, surnamed Warszycka by her first marriage, Oleśnicka by her second, and Zbąska by her third. Brückner adjudged the work to be a vivid account of a momentous life, lived in momentous times.5 Following decades of negotiation, the manuscript was brought to the National Library of Warsaw in 1934, where it was edited and published by Ida Kotowa. Most tragically, the manuscript was destroyed in 1944, in the conflagration of the Warsaw Uprising. Had Stanisławska’s poem been published soon after it had been written, and become embedded in the literary canon, then the reception of the work’s literary qualities would surely have looked askance at the formal deficiencies in favor of marveling at its originality and revelatory nature. Even the censoriously minded may have chosen to hail this preeminent other voice: one that had conceived a unique literary outlet for the conveyance of a woman’s personal feelings and remembrances. Although Anna Stanisławska’s unique contribution to the literary life of her homeland is still unknown to many, Orphan Girl is charged with cutting truths and soulful declarations that reveal a girl, and later a woman, at odds with the course of her life and the age in which she lives, albeit wanting traditional happiness (centered by a grounded spiritual conviction and an engagement with religious 4. See Dariusz Rott, Kobieta z przemalowanego portretu: Opowieść o Annie Zbąskiej ze Stanisławskich i jej Transakcyji albo Opisaniu całego życia jednej sieroty (The Woman from a Repainted Portrait: The Story of Anna Zbąska of the Stanisławski Line and her A Transaction, or an Account of the Entire Life of an Orphan Girl); Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego, 2004), 30–35; Ida Kotowa, “Anna Stanisławska: Pierwsza autorka polska” (Anna Stanisławska: The First Polish Woman Author), Pamiętnik Literacki 1–4 (1934): 267–90; Tadeusz Sinko, “Trzy małżeństwa jednej sieroty” (The Three Marriages of an Orphan Girl), Czas 109 (1935): 5. 5. See Aleksander Brückner, “Wiersze zbieranej drużyny: Pierwsza autorka polska i jej autobiografia wierszem” (Gathered Poems: The First Polish Woman Author and Her Autobiography in Verse), Biblioteka Warszawska 4 (1893): 424–29; Brückner, Dzieje literatury polskiej w zarysie (A Concise History of Polish Culture; Warsaw: Gebethner i Wolff, 1908), 1: 449–50.

Introduction 3 devotion) more than—but not exclusively over—wealth, title and prominence, all of which Stanisławska happened to possess in abundance. This Cinderella hope on the part of the poetess—a hope partly fulfilled on her marriage to her second husband, Jan Zbigniew Oleśnicki, the protagonist of this episode, though tempered by a hard-edged, world-weary matter-offactness—was born of a childhood optimism that what awaited her in life could only ever be joyous. Little did the young Stanisławska know that she would spend much of the life apportioned to her vainly hoping for felicitous outcomes. In fact, it would be her fate to rail against Malign Fortune for taking such pleasure in all the iniquities and calamities that swiped the legs from under her whenever an opportunity presented itself.6

Historical Backdrop Central to the Polish Baroque was Sarmatism, a belief in the idea, derived from religious fervor, that the gentry of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were guardians of the Catholic faith and protectors of the territories where the faith was thought to flourish most. Among the beliefs of the nobility, Poland’s very location, a buffer for Europe against incursions from the idolatrous east, was a part of God’s divine plan. While in Poland the prevailing liberal and heroic spirit championed the individual over monarchical absolutism and shaped viewpoints that were far from the murderous religious intolerance seen elsewhere in Counter-Reformation Europe, the ruling classes became over time swept up in an expression of religious exaltation that led them, convinced of their sanctified position, to accelerate a process of curtailing the mercantile and agrarian classes, from whom during the Renaissance so much creative and intellectual thought had sprung.7 With neglect of craft, trade and agriculture, a prevalent characteristic of local, regional, and national elites, disregard for commercial and agricultural imperatives led to the exploitation of privilege; although this neglect was countered

6. For a discussion on the motif of Fortune in Polish Renaissance and Baroque literature, see Jacek Sokolski, Bogini, pojęcie, demon: Fortuna w dziełach autorów staropolskich (Goddess, Idea, Demon: Fortune in the Works of the Authors of Old Poland; Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego, 1996). 7. For an illustration of Polish Sarmatism pertaining to its characteristics and cultural heritage, see Janusz Tazbir, “The Culture of the Baroque in Poland,” Organon 18–19 (1982–1983): 161–75; Tazbir, Prace wybrane, tom. 4, Studia nad kulturą staropolską (Selected Works, vol. 4, A Study on the Culture of Old Poland; Kraków: Universitas, 2001). See also Maria Bogucka, The Lost World of the “Sarmatians”: Custom as the Regulator of Polish Social Life in Early Modern Times (Warsaw: Polish Academy of Sciences, Institute of History, 1996); and Zbigniew Kuchowicz, Obyczaje staropolskie XVII–XVIII wieku (Old Polish Traditions and Customs in the 17th and 18th Centuries; Łódź: Wydawnictwo Łódzkie, 1974).

4 Introduction somewhat by the nobility’s readiness to throw themselves selflessly into battle.8 The situation was made more acute by the fact that the freedom of the gentry, and in particular of the magnates, was a freedom that was technically boundless; hence there was constant pushback against the power of the king, who, once having been elected by the chivalrous class, owed too much to too many. It was an Arthurian conundrum; one where notions of round-table equality meant that the king’s “knights” felt that they could go their own way; a sensibility which also impeded the formalization of a standing army. The nobility could declare themselves campaign ready if they felt like it, and it was only their general fervor and the lingering memory of the Swedish invasions of 1655–1660, known as the Potop (“Deluge”), that harnessed this collective responsibility in the face of the grave threats confronting them on the eastern and southeastern borders of the Commonwealth. The potential for calamity had been perceived long before the existential crises of the seventeenth century beset the nation. Writing in 1570, the preeminent poet of Renaissance Poland, Jan Kochanowski, in his tragedy Odprawa posłów greckich (The Dismissal of the Greek Envoys), had much to say about national paralysis, which was already a looming prospect. In the play, Ulysses delivers a speech to the Trojan Assembly, charged with having to decide whether or not to return Helen to the Greeks. In his speech, Ulysses decries the path of moral degradation that Troy has taken: “Their example makes rotten the multitude who follow in their path. / Indeed, they are followed by a suite of parasites. / By their notorious luxury and indolence, they fatten like pigs.”9 First performed in the presence of King Stefan Batory and his queen, Anna Jagiellonka, at the wedding of his royal chancellor, Jan Zamoyski, to Krystyna Radziwiłłówna, the play must have caused quite a stir among those present because of its thinly veiled attack on the Polish system of government and the increasingly corrupt ruling gentry. This same sentiment must also have been present in the ether at the time of the coronation of Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki, an event that took place on September 29, 1669. To the chagrin of Jan Sobieski, the king’s military commander, or hetman, and his cohort of malcontents,10 who had seen the defeat of their favored candidate for the Polish throne, Henri d’Enghien, prince of Condé, Wiśniowiecki emerged victorious in the royal election. Wiśniowiecki had made promises to guarantee the existing state of affairs with regard to the liberum veto, a parliamentary device that gave each member 8. See Jan Stanisław Bystroń, Dzieje obyczajów w dawnej Polsce: Wiek XVI–XVIII (Customs and Traditions in Old Poland: 16th-18th Centuries), vol. 1, 2nd ed. (Warsaw: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1976). 9. Jan Kochanowski, The Dismissal of the Greek Envoys, ed. and trans. Barry Keane (Warsaw: Sub Lupa; London: The Polish Cultural Institute, 2018). 10. Daniel Stone, The Polish–Lithuanian State, 1386–1795 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001), 234.

Introduction 5 of the Sejm, or “Diet,” the right to defeat by his vote alone any measure under consideration. This same vote could both dissolve the Sejm and invalidate all acts passed during its session.11 The new king would display a singular inability to make the kinds of military and administrative preparations that were essential in order to counter the Cossack-Tatar raids threatening to overrun the Polish Right Bank. Sobieski, tasked with the defense of the Commonwealth, was greatly alarmed by the actions of the Cossacks, who, under the leadership of General Petro Doroshenko, had several years earlier accepted the protection and support of the Ottoman Empire. In vain, Sobieski petitioned Wiśniowiecki to strengthen the stronghold of Kamieniec in Podolia, on the Commonwealth’s eastern flank. Although he was able to free thousands of prisoners bound for Turkish slave markets, Sobieski had to sue for peace with the Ottoman sultan, subsequently surrendering Podolia in the Treaty of Buczacz (1672), which stipulated that the Commonwealth would have to pay a hefty annual tribute. The blame for this national humiliation was placed at the feet of Wiśniowiecki, and an incensed Sobieski threatened to march on the royal seat, which by that stage was being propped up by a toothless military confederation. Ultimately, it was the king’s wife, Queen Eleanora, having engaged the papal nuncio and a clutch of senators for support and counsel, who brokered a compromise that entailed Sobieski staying his hand.12 As a component of this peacemaking, the penal terms of the treaty arising from the Podolian capitulation were subsequently rejected by the Sejm. It was generally feared that an occupied Podolia meant that it was only a matter of time before the Ottomans and their proxy forces would launch an incursion deep into the heart of the Commonwealth. War was declared, taxes levied, and an army of forty-thousand strong was raised. The king made declarations that Podolia would be retaken, and that they would rid the Commonwealth of the Ottoman threat once and for all. In terms of Sobieski’s military role in the events that unfolded, it would very much be a case of cometh the hour, cometh the man. Sobieski’s tactics were outstanding and presaged his greater military achievement before the walls of Vienna years later.13 The front tiers of the infantry approached the Ottoman encampment on the evening of November 10, 1673, but held back before the fortifications, actuating cat-and-mouse activity with sporadic rifle engagement and surprise attacks. The disoriented defenders manning the embankments found themselves on tenterhooks; and to make matters worse (for the defenders), they were frozen to the bone, with the temperatures 11. See Paweł Jasienica, Polska anarchia (The Polish Anarchy; Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1988); Adam Zamoyski, Poland: A History (London: Harper Press, 2009), 169–88. 12. See Norman Davies, God’s Playground: A History of Poland, vol. 1: The Origins to 1795 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981; New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), 357–62. 13. For an account of the battle and its aftermath, see Zamoyski, Poland: A History, 189–205.

6 Introduction having plummeted in the night. The conditions were ripe for an attack; and it was precisely in the somnolent hour of dawn that Sobieski at the head of his charging forces stormed through the camp, sending Hussain Pasha, the Ottoman commander, fleeing for his life. The remnants of the retreating Turkish army were pursued as far as the Dniester River, where they desperately attempted to scramble across the only bridge capable of carrying large numbers and attendant burdens. The bridge was ripped to pieces by mortar fire (although it may also have collapsed under the weight); and Sobieski’s army spent the rest of the day chasing down and slaughtering the scattered enemy.14 The seismic nature of the victory, known as the Battle of Khotyn (or Chocim), was mirrored by an equally seismic turn of events. Somewhat late in the day, Wiśniowiecki had decided to make what he must have felt would be a morale-boosting contribution to the campaign by travelling to Lwów in order to review the troops. On his arrival in the city, however, he fell violently ill from food poisoning and died soon after. That Sobieski would lead the Commonwealth to victory the following day cleared the path for him to be elected king in the royal election of 1674. It was understandably felt that the nation was in dire need of an experienced and inspiring political leader, one who would set all military affairs in order. Due to Sobieski’s determination to continue to lead the campaign in the east, however, he would not be crowned king until 1676, one year after the death of his cavalry officer, Jan Zbigniew Oleśnicki, the second husband of Anna Stanisławska.

Stanisławska’s Early Life Anna Stanisławska was born in 1651.15 Her father, Michał Stanisławski, had distinguished himself both as a soldier and in countless other roles in royal diplomacy 14. Tazbir writes (“The Culture of the Baroque in Poland,” 168) that this protracted conflict with the Ottoman Empire and their auxiliary forces of the Tatars and Cossacks ultimately contributed to the Orientalization of Sarmatian (that is, Polish) culture: “Poland’s geopolitical situation made her particularly vulnerable to oriental culture which in the eastern territories of Europe constituted an almost native, not merely imported civilization. Poland’s territorial expansion on the one hand, and the expansion of the Ottoman state, on the other, led to direct contacts with the world of Islam. Many Poles had spent years in Turkish or Tatar captivity. A considerable number of fugitives from justice would go to the south-eastern confines of the Commonwealth, to Zaporozhe, where, living among the Cossacks, they would adopt oriental customs and habits. Lastly, the trade linking the Baltic and the North Sea with the Black Sea led through Poland. The south-eastern Polish voivodships were the gateway through which the influences of Asian culture and art flowed into Poland, and the towns which lay on that route were Brody, Kamieniec Podolski and Lvov.” 15. For biographical accounts of Stanisławska’s life, see Barry Keane, Introduction to Anna Stanisławska, Orphan Girl, 1–16; Kotowa, “Anna Stanisławska”; Maya Peretz, “In Search of the First Polish Woman Author,” The Polish Review 38 (4) (1993): 469–83; Rott, Kobieta z przemalowanego portretu. See also Sinko, “Trzy małżeństwa jednej sieroty,” 5; and Stanisław Szczęsny, “Anny ze Stanisławskich Zbąskiej

Introduction 7 and national politics. He was not only voivode, or governor, of Kiev and a magnate in the possession of great wealth, but since his grandmother was Jan Sobieski’s great-aunt, he was also related to Poland’s future king. Stanisławska’s mother was Krystyna Borkowa Szyszkowska, and her family had kindred links with both the powerful Potocki and Zebrzydowski families. By rights, Stanisławska should have had every expectation of a happy childhood, but her mother died when Stanisławska was only three years old. Perhaps as a response to the death of Stanisławska’s infant brother, Piotr, she was sent to live with and be educated by the Dominican nuns in their cloister in Gródek near Kraków, where her great aunt on her mother’s side, Gryzelda Dominika Zebrzydowska, was the prioress. Tragically, the affectionate and attentive Gryzelda died following an outbreak of bubonic plague, and Stanisławska would never experience such motherly affection again. In 1667, Michał removed his daughter from the convent and brought her home to the recently acquired family estate of Maciejowice, located on the right bank of the Vistula River, midway between the southern outskirts of today’s Warsaw and the regal town of Puławy. Rapturous at the prospect, little did the young girl suspect that her being brought home had not been inspired by sentiment, and that her father was not looking to make amends for all the years they had not spent together. A number of years previously, in 1663, Stanisławska’s father had married again, his new wife being Anna Potocka Kazanowska-Słuszka, a confidant of Jan Sobieski and a strong-willed woman who was determined to marry off her stepdaughter as soon as possible. Undoubtedly preoccupied with the turmoil in the country, Michał fell in readily with these plans and found what should have been an ideal candidate for a son-in-law in the person of Jan Kazimierz Warszycki, son of Stanisław Warszycki by his first marriage to Helena Wiśniowiecka. Stanisław was Castellan of Kraków and a distinguished senator. As a magnate of great substance, he was also a church benefactor. Like Stanisławska’s father, Stanisław Warszycki had earned a formidable reputation for military success and martial courage during the Swedish invasions.

The Aesop Episode Both fathers agreed on terms, which must have anticipated the strengthening of bonds between the two great houses. If there had been reports of the young man’s wantonness and comportment, his failings must have been played down or opowieść o sobie i mężach: Glosa do barokowej trenodii” (Anna Zbąska of the Stanisławski Family: A Tale about Her Life and Her Husbands: A Gloss to a Baroque Threnody), in Pisarki polskie epok dawnych (Polish Women Writers of Olden Times), ed. Krystyna Stasiewicz (Olsztyn: Wyższa Szkoła Pedagogiczna, 1998), 69–87.

8 Introduction explained away. Whatever the regret that later followed, this marriage was principally a mercantile decision where factors of political influence and future income predominated, and this ill-considered bartering of his own daughter may have later gnawed at Michał’s conscience, or at least that is what Stanisławska believed had been the case. Stanisławska, too, must have heard of Warszycki’s aberrations; and the poem sees Anna begging her father to release her from the arrangement. But bolstered by the singular determination of his new wife, Michał gave the heartfelt pleadings of his daughter no truck whatsoever. Stanisławska’s disquietude proved justified, for Jan Kazimierz, described throughout the account as Aesop, was a monstrous-looking degenerate who feared only his father’s chastisement and beatings, which were frequent; and must have contributed inevitably to the young man’s physical and psychological ailments. Stanisławska’s father, who as a leader of men and presumably a good judge of character, would come to realize that he had been greatly deceived as to both the suitability of the candidate for his daughter’s hand and to the conditions in which she would live, with it emerging soon after the wedding feast that her newly acquired father-in-law intended to live with the couple; although it may just have been that Stanisław understandably wished to be present in the house in order to protect Stanisławska from his son. With “Aesop” being only capable of self-pleasure, the marriage remained unconsummated. What is more, he was violent and cruel towards Stanisławska, and seems to have settled on a strategy of hounding his wife to death. Stanisławska, in turn, could only hope against hope that her father would rescue her. But disastrously, her father took ill with dysentery on a military expedition in the east and died in Podkamień (modern Ukraine) soon after. The news of her father’s death was deliberately kept from her on the orders of Stanisławska’s father-in-law, who feared that as an heiress to great wealth and lands, Stanisławska might take action to free herself of her marital bond. From what Stanisławska relates, her father had already been considering options to retrieve her, and before his death had appointed Jan Sobieski as Stanisławska’s guardian. Over the course of the next several months, Stanisławska was entangled in a dispute with her stepmother over inheritance rights, and as a result she was able to meet Sobieski under false pretenses. During this meeting, Sobieski advised Stanisławska to mend bridges with her stepmother. It would prove to be sagacious advice, and her stepmother would become her stalwart adviser and companion in the years to come. Although Stanisławska rails against the machinations of Fortune throughout her work, benevolent serendipity played its part when, in June 1669, a royal election was held in Warsaw following the abdication (in 1668) of Jan II Kazimierz Waza, which brought the Waza dynasty to an end. Stanisławska coaxed her fatherin-law into allowing her to join them in Warsaw, perhaps once again claiming

Introduction 9 that the protracted issues pertaining to her inheritance needed further resolution. Having positioned themselves at the very heart of the campaign to elect Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki, who was favored by many of the Polish nobility, the Warszyckis agreed to allow Stanisławska to reside in a nearby convent. Once inside the walls, Stanisławska claimed sanctuary, a move which was then supported by Sobieski, who, as part of the faction of malcontents, threw all his support behind Stanisławska. It could not have been lost on Sobieski that his actions greatly vexed and shamed deeply a family that had singularly been attempting to thwart his ambitions. Free from the clutches of father and son, who planned stratagems to kidnap her, or worse, Stanisławska was free to instigate annulment proceedings. Sobieski appointed lawyers to represent Stanisławska, who argued that she had been married against her will. Witnesses were produced, but the testimony of her stepmother proved crucial. Magnanimously injuring her own reputation, Stanisławska’s stepmother testified to the roles played by herself and her husband in forcing Stanisławska to marry. Her testimony tipped the scales in Stanisławska’s favor and secured the judgment, which was later upheld by Rome. The divorce— for Stanisławska refers to the judgment as such, although clearly an annulment and not a divorce was the available remedy in this instance—created quite a stir in the royal court and elsewhere; indeed, in other times it could have led to soulsearching in many quarters on the legality of arranged marriages. But in spite of the fact that Stanisławska was made the subject of cruel verses, which poked fun at her rather unusual status as maiden (stories about the non-consummation of the marriage must have circulated) and divorcée, few paid attention to the legal technicalities upon which she had won her annulment. Freedom came at a price, however, as Stanisławska was ordered by the court to return a lengthy inventory of gifts which she had received; and her aggrieved ex in-laws made sure that every last trinket was returned.

Oleśnicki For the age in which she lived, Stanisławska was an incomparable memoirist, revealing more of her private life than would even have been deemed prudent until recent times. The foibles, failings and ridiculousness of the people that inhabit her world are laid bare; as are her hopes, unsparing judgments and disappointments. In these terms, the account is unvarnished, and the facts presented unburnished. This is particularly true for her tortuous doubts about the merits and wisdom of marrying again. And though at the beginning of this episode Stanisławska uniquely enjoys the privilege and agency of being able to choose her own future husband, she legitimately wonders what lies behind her suitor’s winning smile and dashing cavalier charm. It is entirely possible she never found a satisfactory answer to this question.

10 Introduction From June until September in 1669, while Stanisławska was waiting out her time in the cloister, still living in fear of what her now ex father-in-law may plot and do, she began to receive a number of amorously presented proposals of marriage, with suitors writing poetry and serenading her from beneath her window. But one innamorato, Jan Zbigniew Oleśnicki, stood metaphorically head and shoulders above the rest in terms of his vigorous suitability, his station, and his determination to bag his bride.16 Belonging to a venerated lineage,17 his home was the estate of Szczekarzowice, situated not far from Stanisławska’s estate of Maciejowice. In any other circumstance, it could almost have been a case of local boy meets local girl.18 Oleśnicki was Sobieski’s dashing chief cavalry officer and a young widower who was reputed to have poisoned his first wife. Aside from the rumors of him having committed uxoricide, there was also a cloud of venality and dissolution hanging over Oleśnicki’s reputation: not necessarily frowned upon, but certainly gossiped about. In literary association, thinking of the devious character in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, Anna could be said to wonder: Is he a Wickham?; And will the charm morph into something else once they are married? From what Stanisławska relates, there was every reason to suspect that there were skeletons in her beloved’s closet, and that something unseemly was lurking beneath the veneer of his magnetism. Even though Stanisławska initially rejected his proposal of marriage, by the year’s end Oleśnicki had settled his betrothed’s debts, this following a preambular agreement signed in Kraków on October 10, 1669 in the company of families and guardians.19 They would be married sometime in June 1670, but not before having had to go to great lengths to secure a dispensation from Rome following the discovery that they were blood-related. Here was yet another juicy tidbit for the gossiping aristocracy attending the engagement celebrations. Ultimately, on the 16. Bystroń maintains that serenading was not uncommon; Dzieje obyczajów w dawnej Polsce, 162. 17. For a history of the Oleśnicki line, see Jacek Pielas, Oleśniccy herbu Dębno w XVI–XVII wieku: Studium z dziejów zamożnej szlachty doby nowożytnej (The Oleśnicki Family of the Dębno Herb in the 16th and 17th Centuries: A Study of the History of a Wealthy Noble Family; Kielce: Wydawnictwo Akademii Świętokrzyskiej im. Jana Kochanowskiego, 2000). On the importance of lineage amongst the Polish nobility, see Bystroń, Dzieje obyczajów w dawnej Polsce, 166. 18. For a descriptive account of courtship and marriage in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Poland, see Alojzy Sajkowski, Staropolska miłość: Z dawnych listów i pamiętników (Love in Old Poland: From Letters and Diaries; Poznań: Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, 1981); see also Kuchowicz, Obyczaje staropolskie XVII–XVIII wieku, 256–69, and Bystroń, Dzieje obyczajów w dawnej Polsce, 119–55. 19. For a discussion on prenuptial contracts in this era, see Anna Penkała, “Szlacheckie kontrakty małżeńskie jako źródła do badań biograficznych i majątkowych na przykładzie intercyzy przedślubnej Antoniny Rzewuskiej i Piotra Miączyńskiego” (Artistocratic Marital Contracts as Sources for Biographical and Property Research, Based on the Prenuptial Contract of Antonina Rzewuska and Piotr Miączyński), Rocznik Lubelskiego Towarzystwa Genealogicznego 6 (2014/2015): 153–69.

Introduction 11 advice of Anna’s stalwart stepmother, both bride and groom thought it best to exchange vows in a village setting, with no invitees; meaning, no wagging tongues. Also prior to their exchanging of vows, Stanisławska had insisted on writing a prenuptial agreement, signed in Warsaw on May 4, 1670, which stated that her husband would entail all his wealth and estate upon her in the event of his death. Whatever may have been thought or said of his waywardness and inconstancy, Oleśnicki seems to have been genuinely enamored with the object of his cupidity. From what we may discern from the account, Stanisławska was also greatly taken with her paramour, and was more than happy to list his virtues and all the characteristics of his pleasant demeanor. They also settled into their various roles: unsurprisingly given what we know of her emancipatory nature, Stanisławska ran both estates with what we may colloquially describe as a “handson approach,” which included day-to-day management and patronage of the local churches and schools. That said, Anna’s engagement with the estate is only ever mentioned in passing, in keeping with the Sarmatian outlook which looked askance at farming activity on the part of the nobility. In fact, there is little in the work that evokes or celebrates either the pastoral or the agrarian idyll.20 There followed several years of connubial happiness, during which time Anna and her husband were of “One body with two souls entwined” (Dwie dusze w jednym ciele; T. 39, St. 355). Their happy marriage, however, failed to produce a child. And yet, during this period, Oleśnicki was the essence of congeniality itself, and when home (which was rare) and not ill (which was not infrequent), he was a man at one with the community that he had ascendancy over; and clearly, Stanisławska was most pleased to be sharing her life with someone possessed of such a pleasant and winning disposition; and one who was also as capable and invested as her father had been when it came to discharging the affairs of state. Oleśnicki also accompanied Sobieski on numerous campaigns aimed at halting the Ottoman incursions in Ukraine. As a result of his bravery and selfless dedication to the cause, he was hailed universally as someone who epitomized the Commonwealth’s chivalrous outlook, a conviction confirmed by his martial feats during the Battle of Khotyn; in recognition of which Oleśnicki was asked to lead the subsequent victory celebrations. However, when away on these military campaigns, he was less than chivalrous when it came to the preservation of his marital vows of constancy and fidelity. One instance of his waywardness is recounted, but it may have not been the only such occasion. Stanisławska is never to be found pining for her absent husband; and indeed the independence she claims for herself is likely to have been a contributory factor in the deterioration of their marriage. (It is significant that Stanisławska fails in 20. For more on the Sarmatian relationship with the land and its cultivation, see Bystroń, Dzieje obyczajów w dawnej Polsce, 154–58.

12 Introduction this account to relate the course of her own life and daily existence on its own terms.) Such self-empowerment,21 determinedly free of family intervention, was probably what her father-in-law looked upon most with disapproval. If Oleśnicki’s inconstancy when away at war was in accord with the cultural norms of the time, one that allowed men the freedom to indulge in extramarital dalliances,22 it was the fact that what he got up to had become universally known and gossiped about that must have soured affections; and it was more than likely that Stanisławska was exasperated by the notion that her cuckolding husband—who was from her perspective only “the worse for wear”—expected to be waited on hand and foot on his return home. That she wasn’t the attentive nurse was perhaps her own way of responding to the humiliation. The ailing Oleśnicki, for example, upbraids his wife in the account for the inept performance—or the deliberate neglect—of her nursing duties with respect to both his father and himself. Towards the close of 1674, when Oleśnicki was on a military expedition with Sobieski, his father fell ill and was presumed to be nearing his end. Typical of the humanity accorded to Sobieski in this account, he orders Oleśnicki home so that he may pay his last respects; but no sooner does the son arrive than his father rallies. Jan himself falls ill, and following several days of being at death’s door, sometime in mid-January 1675, he passes away. Certainly her father-in-law holds a great deal of bitterness towards Stanisławska; and the unreasonable behavior towards his daughter-in-law by both himself and other members of the family as Oleśnicki slips from life may have had its justification; from his perspective at least. There followed for Stanisławska a period of understandable shock and sadness at the passing of her husband, but she had almost no time for feelings of desolation as it transpired that Oleśnicki’s father, with whom she already had fractious relations, wanted his son to be interred in the family chapel located in the Benedictine Monastery of the Holy Cross on the slopes of the mountain of Łysa Góra in the Świętokrzyskie Mountains. Stanisławska resisted, being determined to have Oleśnicki interred in the more local Church of the Holy Trinity in Tarłów, the adornment of which both she and her husband had funded. More pain would follow for Stanisławska when Oleśnicki’s surviving relatives made recourse to the courts, and threats, in order to reclaim the estate and lands of Szczekarzowice.

21. Alina Kowalczykowa would describe the choice on the part of Stanisławska not to mention her dayto-day accomplishments as characteristic of women’s self-portrayal to leave certain things unsaid; see “Zniewolenie i ślady buntu—czyli autoportrety kobiet: Od Claricii do Olgi Boznańskiej (Constraint and Rebellion—the Self-Portraits of Women: From Claricia to Olga Boznańska),” Pamiętnik Literacki 97 (1) (2006): 146. 22. See Maria Bogucka “Marriage in Early Poland,” Acta Poloniae Historica 81 (2000): 59–65.

Introduction 13

A Sacral Legacy A rather grandiose expression of Oleśnicki’s family credentials had been the church in Tarłów, which, as a familial patron of the church, it had fallen upon Jan to adorn. Yet although the duty was his, it would prove to be a labor of love and commitment to which his wife would devote herself wholeheartedly over the course of several years, and well beyond the duration of their marriage. It is likely that in the time between Oleśnicki’s death and her marriage to Jan Zbąski, less than a year later, Stanisławska devoted a great deal of energy to overseeing the completion of the artwork in the chapel, which involved commissioning artists—most likely from Kraków—and settling with these artists on an overarching vision. Throwing her all into the undertaking, her engagement and singularity of purpose also reflects the extraordinary drive which would be manifested in the writing of Orphan Girl several years hence. Today, as one walks into the Oleśnicki family chapel,23 the after-presence of Stanisławska is palpable, so interlinked are the artworks with the cornerstone themes and factual events of Orphan Girl. It is all especially and impeccably foregrounded in the motif of Danse Macabre, or the Dance of Death, signifying that death unites all.24 Not only in one work, but in a series of interlinked mural paintings, the personification of Death, a decaying cadaver, is seen placing his hand on the shoulders of young and old. One of these paintings, titled “Family and Death” (featured on the cover of this book), seems to be an allegorical representation of Anna and Jan; as he is being led away by Death (that the figure is Jan is denoted by the presence of the Oleśnicki crest). In the painting we see Jan holding Anna’s hand; and he is unwilling to let it go. His anguish is clear in the wretchedness of his countenance, and as he looks back, husband and wife hold each other’s gaze for the last time. Tears can be seen flowing down Anna’s cheek. More heartbreakingly still, the child they never had, or would have, is to be seen pulling at Jan’s robe. An idiosyncratic absence in these paintings—commensurate with their already discussed absence in Orphan Girl—is that of serfs, or the representatives of the mercantile classes: an assurance to the nobility, perhaps, that in spite of the fact that death is the great leveler, their moment of passing from this life to the next would not have to be shared with lowly unfortunates. The locals attending mass may have been chagrined (or relieved) to find that Death was not coming for them: yet their absence was never redressed by Stanisławska, indicating that 23. A fascinating description of the chapel’s artworks and motifs is provided by Aleksandra KoutnyJones, “A Noble Death: The Oleśnicki Funerary Chapel in Tarłów,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 72 (2009), 169–205. 24. For further reading, see Aleksandra Koutny-Jones, Visual Cultures of Death in Central Europe Contemplation and Commemoration in Early Modern Poland-Lithuania (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 16–90.

14 Introduction her independence of mind did not negate the fact that she was a Sarmatian noblewoman who saw no purpose or gain in the mollification of anyone. The Oleśnicki family crypt is located directly under the chapel. It was opened in 2005, and the coffin of Anna was found lying beside that of her congenial cavalier.

Old Poland’s Feminist Zeitgeist As a perceived matriarch of women’s literature in Poland since the discovery of the manuscript by Aleksander Brückner, Stanisławska the historical figure has always been best known for “The Aesop Episode” of Orphan Girl, which so comedically depicts her heroic efforts to secure a divorce from her deranged first husband. The poem’s biographical accounts of Stanisławska as Lady Oleśnicka or Zbąska are less well known, recounting as they do her comparatively more conventional marriages. Yet these episodes have their own quality of importance as they presage later literary accounts by women of a similar stature and station who understood, or at least expected, marital love to be a cradle of mutual affection and a meeting of minds. Given that Stanisławska’s opus remained an unknown work in its era and beyond, we may also say that the feminist spirit of the age that it encapsulated with respect of women’s emancipatory outlook managed to survive. Across the subsequent decades, that spirit was as though ethereally transposed to settle like evening mist over the meadows of early eighteenth-century estates, where creative women thought very seriously about the changes they could bring about which would ameliorate, alleviate, and elevate their circumstance.25 One such figure was Franciszka Urszula Radziwiłłowa (1705–1753),26 who brought to both her poetry and plays, which were privately performed for diversion in her marital residence of Nieśwież (modern Lithuania), the worldview of aristocratic women. That worldview principally proffered cautionary advice to young ladies on the well-trodden paths and hard-earned insights of marital existence, while also providing a confessional perspective, in particular about 25. For further reading, see Maria Bogucka, Women in Early Polish Society, Against the European Background (Aldershot, Hampshire, UK: Ashgate, 2004); Karolina Targosz, Sawantki w Polsce XVII wieku: Aspiracje intelektualne kobiet ze środowisk dworskich (Savantes in 17th-Century Poland: The Intellectual Aspirations of Courtly Women; Warsaw: Retro-Art, 1997); Andrzej Wyrobisz, “Staropolskie wzorce rodziny i kobiety—żony i matki (Old Poland’s Models of the Family and Women—Wives and Mothers),” Przegląd Historyczny 3 (1992), 405–21. Insightful views on this topic can also be found in Bożena Popiołek, Kobiecy świat w czasach Augusta II: Studium z mentalności kobiecej czasów saskich (The Female World in the Era of Augustus II: A Study of Female Mentality in the Saxon Era; Kraków: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Akademii Pedagogicznej, 2003). 26. See Franciszka Urszula Radziwiłłowa, Selected Drama and Verse, eds. Patrick John Corness and Barbara Judkowiak, trans. Corness, introduction by Judkowiak (Toronto: Iter Press; Tempe, AZ: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2015).

Introduction 15 the challenging position of married life for a woman surrounded by the “spying” eyes of court. Perhaps because of her close relations with her enlightened parents, Franciszka had spurned foppish, pitiful suitors and chosen instead a husband who made an “impetuous advance.” In every sense, it was love at first sight. The fortunate individual was Prince Michał Radziwiłł (1702–1762), who was both governor of Vilnius and Field Commander of Lithuania; who in fact had had to overcome his mother’s disapproval of the match. Like Stanisławska, Radziwiłłowa was an heiress to a massive fortune, and she and her promesso sposo would sign a prenuptial agreement, bequeathing to one another all of their sizable properties. The marriage was a tender affair at the beginning, founded on strong emotions and mutual regard. In time, Franciszka would harbor warranted suspicions about her husband’s fidelity, and conveyed to him in epistolary writings and dedicated poetry complaints about his neglect and indiscretions: “Men often break faith, so I have heard tell.”27 Unlike Stanisławska, who seems to have been locked into the orbits of her marriages, even when, for example, her first husband wanted to throttle her in the bath, Franciszka would lament the fact that a woman in her position had to think of her honor and fidelity. The tenor of her digression boiled down to the idea that a satisfyingly vengeful tryst, or indeed a bevy of gallant lovers, would provide both an overdue redress and a long-awaited sexual release—after all, were wives to wait for their husbands to come home: and when home, would they be up to the task? Ultimately, while the freedom to love is wistfully dismissed in favor of the moral option “to quell the heart,” the married woman was doomed to social entrapment. For Radziwiłłowa, however, this destiny did not mean that the boundaries of connubial limitations should not be extended to their extendable limits: beginning with the insistence on a spouse’s fidelity. It was never going to be either a winnable argument or a plausible expectation. And so, ultimately, Franciszka resigned herself to the undeniable fact that legal unions generally corrode emotional bonds. At such a revelatory juncture, Stanisławska, wife to Oleśnicki, would have interjected to say that the rot starts when the husband is too handsome for his own good. And that unfortunate circumstance is made all the worse when his inevitable conceit is married to soldiering—both on and off the battlefield. A contemporary of Radziwiłłowa, who also possessed a life experience and outlook comparable to that of Stanisławska, was Elżbieta Drużbacka (1695– 1765),28 best known for her Opisanie czterech części roku (A Description of the Four

27. See Radziwiłłowa, Selected Drama and Verse, “Response to a husband,” 357. 28. See Krystyna Stasiewicz, Elżbieta Drużbacka: Najwybitniejsza poetka czasów saskich (Elżbieta Drużbacka: The Greatest Woman Poet of the Saxon Era; Olsztyn, Poland: Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Pedagogicznej, 1992).

16 Introduction Seasons, 1752).29 A collection of descriptive paeans to nature’s beauty, Opisanie earned the poetess the epithets of Slavic Sappho and Sarmatian Muse. Drużbacka also left an epistolary legacy that outlined her biography, which tells us that she received a courtly education and married the courtier Kazimierz Drużbacki in 1720, with whom she had two daughters. Following her husband’s death in 1740, a passing that also inspired her to write both poetry and creative prose, she chose to be a governess at several courts, but ended her days self-confined in a Bernardine convent. Tragically sharing the fate of the manuscript of Orphan Girl, the original manuscripts of Drużbacka were destroyed in the Warsaw Uprising. Drużbacka’s musings on marriage, echoing the experiences of Stanisławska and reflecting the misgivings of Radziwiłłowa, were formulated along the familiar lines of mutual affection and a sincerity arising from blinkered amorous purpose, and a scenario that precludes the consideration of material aggrandizement. Beyond the circumstances by which an ideal match may come about, Drużbacka invested a great deal of thought in the resolving of one of the most pressing issues of human relations: the prolongation of happiness within marriage. She was able only to arrive at solutions that came up against numerous impediments, such as husbands finding diversion and occupation with people with whom they had no business associating. That said, for all of Drużbacka’s concerns, she maintained that divorce flew in the face of God’s will, and that the veneer of respectability had to be maintained at all costs. There could be no association or veneer of respectability where Salomea Pilsztynowa (1718–1763?)30 was concerned. Her combustible nature, independence of mind, and scandal-filled life cry out for comparison with Stanisławska, who, as we know, was not without her share of scandalous appendages, often for simply refusing to share the fate of so many of her female contemporaries. Also, like the historical legacy of Stanisławska, Pilsztynowa’s lost memoir was discovered at the end of the nineteenth century in the most fortuitous of circumstances.31 What is more, Pilsztynowa, given her reputation of being the first female doctor in Polish history, is also a matriarchal figure of female endeavor. Born in Nowogródek, a small town in today’s Belarus, Pilsztynowa was of the burgher class, and when she 29. See Elżbieta Drużbacka, Wiersze wybrane (Selected Poems; ed. Krystyna Stasiewicz, Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Neriton, 2003). 30. Salomea Regina Pilsztynowa, The Istanbul Memories in Salomea Pilsztynowa’s Diary “Echo of the Journey and Adventures of My Life,” 1760, ed. and trans. Paulina D. Dominik (Bonn, Germany: Max Weber Stiftung–Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, 2017); Pilsztynowa, My Life’s Travels and Adventures: An Eighteenth-Century Oculist in the Ottoman Empire and the European Hinterland, ed. and trans. Władysław Roczniak (New York: Iter Press, 2021). 31. The manuscript was found by Ludwik Glatman in the repository of the Czartoryski collection, located in Puławy. See Ludwik Glatman, “Doktorka medycyny i okulistka polska w XVIII wieku w Stambule” (A Polish Lady as a Doctor and Oculist in Istanbul in the 18th Century), Przewodnik Naukowy i Literacki (1894), 926–46.

Introduction 17 came of age, and following what must have seemed at the time to be a sensible arrangement, she was forced by her parents into a marriage with a physician who was a great deal older than she was. This episode marks the last time, however, when anything was forced on Pilsztynowa. What follows in the memoir is an account of her emancipation by way of her attainment of a professional occupation, having acquired from her husband a knowledge of apothecarial and medical practice. The account is all the more colorful for the fact that she accompanies her husband to Istanbul, where she becomes his equal, if not superior: she saves him, for instance, from an accusation of malpractice, which could have led to his execution, and relishes the opportunity of being able to conduct her life on what could be understood as a professional footing far removed from the confinements of her own country and society. Once Pilsztynowa gains a taste for freedom, she flourishes and wins a license to practice, and her interests multiply and dazzle like light through a prism. She explores many aspects of healing and gains respect and status in her newly adopted home. Pilsztynowa would combine her medical knowledge with local practices, and even incorporate occult elements into her diagnostic preliminaries, such as astrology. Throughout Pilsztynowa’s story there are romances, more marriages, and near-death adventures. And in many respects, while it is delightful to juxtapose her experiences and worldview with those of her female contemporaries, she most certainly resembles the male figure of Oleśnicki—one who, as we may imagine, would have had no compunction in abandoning a spouse and embracing a life of unbridled adventure. A speculative conceit, no doubt: but the coalescence of the spirit of the age, in what was a creative and lived sense, could only ever lend itself to such flights of fancy. All options were on the table, and for the first time everything was technically possible. Even if there was a price to be paid, be it individual or collective.

An Other (and Yet the Same) Voice: A Note on the Translation My translation is based on Ida Kotowa’s 1935 edition of the work. Continuing from my efforts with “The Aesop Episode,” I have remained convinced that the power of the account is predicated on the poetic form and a conjuring up of the direct voice of Stanisławska. She was imaginatively present to me for all the years at my keyboard translating this work, and my entire creative input is based on how I imagined her to be as a person. To this end, I emulated the metrical and rhyming scheme of the poem whilst also looking to accentuate the poem’s narrational imperative. I took this judgment further and divided “The Oleśnicki Episode” into smaller titled episodes, a division intended to foreground the poem’s epic and historical sweep and also to support the reading of what is a lengthy poem. Also worth drawing attention to are the gloss margin notes, which can inform and

18 Introduction confuse in equal measure. In this regard, it is important to be mindful of the fact that they are Stanisławska’s contemporaneous explanations of past events; and so, for example, Sobieski is often referred to as “today’s king.” This is because he was king at the time of Stanisławska’s writing of the poem, but in the events that the poem describes, Sobieski’s coronation was some way off. This episode ends at the point where Stanisławska has buried her husband, has been attacked by his relatives, and is despairing of the age where death takes us all. One further episode—or marriage, as the case may be—awaits translation. It is a work that I hope to complete in its entirety. But cognizant of the time it took to complete the first two episodes, I can only hope the coming years will be kind, and that Stanisławska’s Fortune will look benevolently on the endeavor (Stanisławska would not be hopeful). Finally, it remains for me to reiterate that this translation could not have been completed without drawing on the research which has been written on Orphan Girl; and it is certainly my hope that “The Oleśnicki Episode” not only celebrates the legacy of the larger work itself but also the work of the many scholars who have thrown light on the ways and means by which the poetess came to relate both her life’s story and the dolorous distresses of her age.

ANNA STANISŁAWSKA

Orphan Girl: The Oleśnicki Episode

The Old Man and His Malevolence

(continuing from “The Aesop Episode”)

Threnody XXIX (Stanzas 274–75) 274. I remain pinned to this precipice, Left abandoned and with no choices. The papers I hold in my hands May ring-fence estates and lands, And allow me to step outside; But I have much to think about: With a coronation to be held, I could be the entertainment. 275. This would normally be an event That I would happily attend: To join the ranks amongst my own. Yet I know well what the old man Is plotting, as does King Michał: Having heard the spleen and vitriol, He decrees that the warring parties Should desist from settling scores.

The coronation takes place.

King Michał sends a letter to Master Krakowski.

The Heart Awakens and Hope Stirs Threnody XXX (Stanzas 276–83) 276. As the old man stews in his spite, There is some comfort in the thought “That the good Lord crowns a man’s life Not with death, but a faithful wife!” And though the point may be heartening To those who barter and bargain For the bride and her dowry, I doubt if it applies to me.

21

The will of God.

22 ANNA STANISŁAWSKA 277. I could be that perfect spouse, But firstly I’d have to say “yes.” But will he knock on my door again? Doesn’t he know the rules of the game, Where a “no” is but the first step In the merry dance of courtship? I’ll send to Our Lady this prayer: Let him bang louder on the door!

Oleśnicki takes to the road, having made an offering to Our Lady.

278. In Jaworów, ever-bustling, He meets with my guardian. And on asking about the judge’s Strictures concerning the divorce, He travels to Jaworów He proceeds to pour his heart out: to see today’s king. “She’s free to marry, is she not? So I would be greatly obliged If you gave the lady a nudge. 279. I’ve serenaded and implored. But she has made up her mind, And her answer is a firm ‘no.’ Now I’m a sensible fellow, But the call of love overrules Logic, and sings the song of fools. So I beg for your winning voice; Otherwise, I won’t stand a chance.”

He asks the king to intervene.

280. The serene one listens and nods: His head is bowed; his eyes are closed. He puts himself in the boots Of this hapless suitor, whose plots His Highness, today’s And trysts have left him clutching at straws. king, promises to help He’ll need letters and advice: him in his cause. There can be no beating about The bush, for the lady may not wait.

Orphan Girl: The Oleśnicki Episode 23 281. He sends a flurry of letters, Splurging his heart out on the pages, Saying that once the Sejm has convened, If the Lord is merciful and kind, He will travel here with the hope Of a second crack at the whip. I shall have less to say this time; I won’t even interrupt him!

He writes letters, asking me to give him hope.

282. If I were to give thought to his Suitability, I’d say this: He hails from an esteemed lineage Of soldiers and aristocrats, Whose lands, an occasion of pride, Offer harvests and a fat yield. It boasts a line of strong women Who’ve anchored family and home.

His merits.

283. I meet him not far from Kraków: Such serendipity! My life There and then! Finding my gallant Lost for words. He may be tongue-tied, But he’s dying to blurt something out! Oh wouldn’t it be wasted effort To propose marriage on bended knee, When you need more than just a ring!

The Old Man Is Put in His Place and They Conspire to See Me Married Threnody XXXI (Stanzas 284–96) 284. The great and the good have gathered Where the king-elect will be crowned. Everyone is minding their Ps and Qs, And not slinging insults in my face.

They all descend on Kraków.

24 ANNA STANISŁAWSKA If I’m no longer the harlot, I’m still the one he calls a slut. The old man cannot hold his peace, Decrying life’s great injustice.

Master Krakowski rants and raves.

285. I’d just risen from my slumbers And was rubbing sleep from my eyes, When there was a knock and a call; Before me a man with a scroll, The divorce is official. Sealed by both court and magistrate; A parchment that reveals my fate, Freeing me entirely of blame, Whilst thrashing my father’s good name. 286. The good Lord sends tongues of fire To those who are banging at the door, In their eagerness to share tidbits Of counsel and unwanted advice. Her Highness, the But it is the serene princess, mother of the king, The mother of he who wears the crown, fought hard to secure Who makes touching annunciations my divorce. In support of this helpless wretch. 287. She takes the bull by the horns, And promises to right all wrongs. She won’t take a “no” or a “yes” For an answer. And her letters Will leave no room for confusion. She sternly instructs the old man With a fine choice of expressions: That he practice the art of silence. 288. He promises to end his attacks, But can’t keep himself in check. He thinks that he can use his envoy To make my life a misery.

Master Krakowski promises, but continues with his shenanigans.

Orphan Girl: The Oleśnicki Episode 25 He who’ll smile and glad-hand the lot, Marking time, plotting God knows what! Quite the leap! From lowly servant To esteemed man of the Diet.

Master Krakowski’s representative, a deputy at the coronation, does his dirty work.

289. He’s good at serving, but politics Requires a different set of skills. Finery can give some substance To those who carry airs and graces, But power bestowed is easily lost; Especially for jangled puppets. The old man shows him a new trick, Master Krakowski beats When he thrashes him with a stick. his representative. 290. This esteemed man of the Diet, Stripped to the bone of all pride, Knows that his lot is little more Master Krakowski is Than the fate of a bridled mare: fined for the thrashing. All he can do is trot when bid, And gallop when his rump is whipped. Loyalty is no longer due When you’ve been beaten black and blue! 291. No one is free to thrash an envoy, And the old man is forced to pay A fine, and suffer opprobrium For his actions. This doesn’t stop him Master Krakowski orders me to discuss From showing up at the convent; terms with the And how greatly he is burdened! representative. “My man shall remain in the Diet, And you’ll say nothing about it!” 292. The courts have put him in his place: He can shout till blue in the face, But we must follow our agreement As if it were a sacred contract. Yet there will be stubborn progress,

26 ANNA STANISŁAWSKA With me enclosed in four walls. If life’s a search for what we’ve lost, Then it’s best not to count the cost. 293. Only the Lord senses our needs, When we stumble on bended knees Before the vagaries of chance, Where hope is that broken promise. Feeding festive days, the plate Should be a delight to the palate, But my fate’s a fool’s complement That leaves my lot both numb and spent. 294. My family and guardian Are resolute in their opinion That we should exchange vows as soon As possible: to strike while the iron I agree to marry Oleśnicki. Is hot! I agree to all persuasions, But not without some reluctance. Oh, I listen and nod my head, But I’m knotted and tongue-tied. 295. Their counsels would prove persuasive: “Are you to remain a captive? Juicy gossip can always be found, If you follow someone around. As long as you’re vulnerable, That man will always be able To shout at you in every place. Matrimony will shut those gates!” 296. If sincere advice is given, Then surely it should be taken. I must take what is a bold step, To be steps ahead of Aesop. Is he not in his tower as I speak, Counting the fortune I gave back!

All debts have been paid.

Orphan Girl: The Oleśnicki Episode 27 I wish him well with all his tricks: The papers I hold say we’re quits!

My Love Is My Relative Threnody XXXII (Stanzas 297–301) 297. My wedding day is imminent: And I’m at sixes and sevens. They say I’m listless and confused: But I would call it second thoughts! And now I’m left parrying arguments That trumpet the benefits. What is the rush, for heaven’s sake?! Are our holy priests short of work? 298. They pooh-pooh my protestations As a woman’s “stuff and nonsense.” My guardian plans a banquet, But suddenly thinks better of it When it’s discovered that bride And groom are closely related. The ringing of joyous bells are hushed: Some unions should never be blessed.

His Highness, he who is king today, had planned to hold a wedding banquet for us, but then we discovered that, as cousins, we needed a dispensation from the nuncio.

299. Dispensations cannot be secured For either love or minted gold. So we must send our plea to Rome. The city chosen for the What a shame to send our guests home , engagement celebrates Those who would witness our union, like it’s a wedding. As we would surely spoil their fun. When a king is paying the bill, Guests will eat and drink their fill! 300. This was an engagement banquet To remember: for all the great Had prepared speeches in advance;

28 ANNA STANISŁAWSKA Written with grace and eloquence. The Marshall treated every guest To oratory that few would forget. Wine can give speech a certain tone; And pliant ears will gulp it down.

Today’s Marshall gave back a great ring.

301. One day he will renounce his ring, But today he is in full song. With a flourish, he takes his seat; But not before he lists his titles. And then the Chancellor’s son rises And speaks of a life in holiness. He of the Koryciński lineage Moves all with weepy nostalgia.

I Am Told Horror Stories about My Distant Cousin Threnody XXXIII (Stanzas 302–11) 302. And when we manage to ascertain The crux of the protestation: That cousins should not be wedded, We send letters to Rome. We know that steps must be followed. Letters of great intricacy Are sent to the eternal city: What a lot of stuff and bother; Sure we hardly know each other! 303. Juicy gossip can always be found, If you follow someone around. And our guests find themselves in heaven By this heaven-sent occasion; They tell me all sorts of things about him. To make notes on his countenance Out of concern. And trade their salacious rumors. Oh how they bandy gossip about To willing souls eager for spite!

Orphan Girl: The Oleśnicki Episode 29 304. Now I’d brush this gossip aside, But I am filled with disquiet. If there’s truth to half the stories, I should be saddling a swift horse And fleeing into the blessed night. My enquiries, cautious and discreet, Reveal a riot of revulsions That leaves me with palpitations.

My sense of alarm increases.

305. Guests have the bit between their teeth; With each story worse than the last. “Sure isn’t he a vile sort of a man, They tell me he Having laced his wife’s drink with poison; poisoned his wife, and And stood by as she grabbed her throat.” that he has a venereal And they don’t want to tell me, but . . . disease. Well he carries the kind of disease That’s a mark of carnal disgrace. 306. But how to believe a single word; In this, the age of falsehood? Truth and lies serve the convenience Of every blessed circumstance. This lot can be smiling to my face, But plotting all sorts of deviousness. Are not piety and prayerfulness Always credible witnesses? 307. They spread gossip and hatch their plots, And now the bride is in their sights. He’s told that I’m apoplectic, And acting like a lunatic. Indeed, never have they seen A more ill-suited pairing! When you are the victim of malice, You understand the power of lies.

They continue with their warnings.

30 ANNA STANISŁAWSKA 308. They clamor for us to break faith With the declarations we’ve made; But when a mob is baying for blood, It’s best to grasp what’s left of truth, And remember that people’s concerns Are often the sport of mud-slinging. Oh how they love to give advice . . . And then swear us to secrecy! 309. I have not revealed the turmoil Stirring in my heart, but flight is all That I can contemplate at this time. And that would show the lot of them! Those with their smiles and smugness; I should flee far from here. So confident in their advice; Thinking that they could matchmake: That they would match and I would take. 310. Truth be told, I could have stood firm; So I must share some of the blame. But I have learned a hard lesson: I’ll share my thoughts with no one! I have no one to share my feelings of Keeping your own counsel serves best desperation with. When there’s no one you can trust. Let my feelings be mine to keep: I’ll banish their plots and gossip. 311. My world is a world of nightmares, Filled with the screams of night terrors, A poor creature to be pitied, Stared at; laughed at . . . and talked about. And even intimidated. As when a man whom I’d never met, And not wanting to say who he was, Urged me to ride far from this place.

He was a deputy of the Sejm.

Orphan Girl: The Oleśnicki Episode 31

My Stepmother Makes Me See Sense Threnody XXXIV (Stanzas 312–20) 312. I ride to the nearest estate, And when I arrive, I am met By my stepmother, who, being so My stepmother was by Anxious that I consider my choices, my side. Wants to be upbeat and excited. Fussing over her flustered bride, She babbles on about future joys With sincerity in her voice. 313. But I’m impervious to the guff That would see me playing blind man’s bluff! They and their schemes and false promises! Do they really think that the answers Are awaiting me at the altar, Making vows to obey a monster! I’m sure he’s all pleased with himself, But I should really call it off. 314. Afflicted by anxiety, Feeling frayed of mind and body, Swirling in a faintness of grief On the road I fall ill. And a weakening of resolve, I’m at a loss about what to do. Yes, I should; but do I want to?! My stepmother asks She senses that something is amiss; what ails me. “Sure isn’t she marrying by choice?” 315. A burden shared is all about truth: But I should really spare us both! Well if truth’s a bitter pill, Let her be prepared for every ill Deed. Didn’t good people swear blind That my beloved is a diseased

I confide in her.