On the Edge: Feeling Precarious in China 0231212143, 9780231212144

Charismatic artists recruit desperate migrants for site-specific performance art pieces, often without compensation. Con

125 103 29MB

English Pages 408 [405] Year 2023

Table of Contents

Preface: Trial by Fire

Acknowledgments

Introduction: Grasping the Precarious

1. The Delegators

2. The Ragpickers

3. The Vocalists and the Ventriloquists

4. The Cliffhangers

5. The Microcelebrities

Conclusion: Viral Precarity

Notes

References

Index

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Margaret Hillenbrand

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

ON TH

E

E DG E

Feelin g

P re c a rious in C h ina

MARG A RET HILLE NBRA ND

ON T HE E D G E

On the Edge FEELING PRECARIOUS IN CHINA

Margaret Hillenbrand

Columbia University Press New York

Columbia University Press wishes to express its appreciation for assistance given by the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange and Council for Cultural Affairs in the publication of this book.

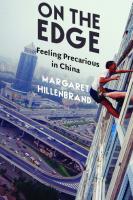

Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester, West Sussex cup.columbia.edu Copyright © 2023 Columbia University Press All rights reserved Cataloging-in-Publication Data available from the Library of Congress LCCN 2023003860 ISBN 978-0-231-21214-4 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-231-21215-1 (paper) ISBN 978-0-231-55923-2 (electronic) Printed in the United States of America Cover design: Chang Jae Lee Cover image: © Li Wei, 29层自由度, “29 levels of freedom,” 2003, Beijing, 150 × 150 cm. www.liweiart.com

For Sam, Max, and Alex

Contents

Preface: Trial by Fire ix Acknowledgments xxi Introduction: Grasping the Precarious 1 i The Delegators 54 i i The Ragpickers 94 i i i The Vocalists and the Ventriloquists 129 iv The Cliffhangers 167 v The Microcelebrities 202 Conclusion: Viral Precarity 247 Notes 267 References 325 Index 361

[ vii ]

Preface Trial by Fire

What greater sorrow than being forced to leave behind my native earth? —E URI PI D E S, EL ECTRA

F

ire is a routine peril in the migrant settlements that fringe the outskirts of Beijing. These perimeter places are tightly packed with people who dwell in cramped, sometimes multiuse spaces alongside chemicals and machines; serviced by outdated, overloaded electric wiring and with communal cookers in the corridor. Once ablaze, a fire can rip explosively through these shanties, leaving scant time or space for refuge. Yet fire itself is not necessarily the cruelest threat posed by conflagration to those who live in China’s urban twilight zones, as residents of the Daxing District 大兴区 on the outskirts of Beijing learned to their cost in the winter of 2017. On the evening of November 18, a blaze broke out in the coldstorage basement of a two-story building in Daxing’s Xinjian 新建 urban village, located just outside the capital’s Sixth Ring Road. At least nineteen people, including eight children, died in the flames.1 Yet in the days that followed, locals had little chance to mourn. Before the gutted building was even fully soused, the local authorities had issued a comprehensive eviction order for Xinjian. Using fire safety as its rationale, the city government essentially condemned the entire settlement.2 Residents, perhaps as many as 250,000 of them,3 were forced to evacuate their homes; workshops and small businesses were shuttered; stock spilled out onto the sidewalk; chaos reigned on the subzero streets (figure 0.1). Bulldozers rolled in and flattened the makeshift structures in which, only days earlier, a dense ecology of people had lived and moved and had their being. Desolate photographs [ ix ]

Figure 0.1 The posteviction streetscape in Xinjian. Source: Reproduced with permission from Shutterstock.

of the freezing posteviction streetscape showed shattered lives and numbed faces, abandoned toys, and pedicabs piled high with hastily packed possessions. For some of these migrants, even a return to their rural roots was impossible, since large-scale land dispossession in the countryside since the 1990s has steadily unraveled that traditional safety net.4 In one sense, the numbed faces and abandoned toys suggest that the Daxing fire and evictions offer an object lesson in what Naomi Klein has called “disaster capitalism”5—although “disaster capitalism with Chinese characteristics” might be a more apt term given the state’s still-stated commitment to socialism. According to this “shock doctrine,” traumatic events, either natural or man-made, crack open exploitable portals of opportunity through which governments can railroad—bulldoze—radical socioeconomic change that their shell-shocked subjects, still reeling from catastrophe, are ill-equipped to fend off. As Klein puts it, “It is in these malleable moments, when we are psychologically unmoored and physically uprooted, that these artists of the real plunge in their hands and begin their work of remaking the world.”6 The district of Daxing had long suffered under what Loïc Wacquant calls “a blemish of place.”7 It warehouses migrants of varied skill sets whose services [ x ] P reface

China’s capital city needs but whose living, breathing personhood it often prefers not to encounter at close quarters.8 I say “needs,” but “needed” might be the more accurate form of the verb since plans to reduce Beijing’s swelling migrant population were already afoot well before the fire9—a point driven home by the fact that no relocation options were apparently offered to the dispossessed after the order to leave.10 Furthermore, if social cleansing formed one part of the eviction agenda, the lucrative possibilities of land requisition and reuse predictably constituted the other. In short, a strong stench of disaster capitalism lingers amid the ashes of the Daxing blaze. Yet Klein’s study of inventive state pillaging includes a quotation from the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano that is perhaps even more pertinent to the case at hand. Galeano asks, “How can this inequality be maintained if not through jolts of electric shock?”11 In citing Galeano, Klein is referring explicitly to the links between torture and predatory neoliberalist policies, but this connection between opportunism and ruin can be extrapolated more broadly. As a ramshackle settlement that abuts the sleek metropolis, a peri-urban site that ministers for a while to the city’s wants but is sealed off from it by a cordon sanitaire, Daxing emblematizes inequality and exclusion. But it did so long before the fire and evictions in November 2017. Like the many other so-called urban villages that have sprung up in semilegal ways on the outer rims of China’s big cities, its status as a site of stigma was already well-established.12 These “island-like slums”13 form notorious archipelagos of disenfranchisement. Their denizens usually lack urban household registration (hukou 户口) and are thus denied access to public services such as local schools, public housing, and health care; they work jobs without contracts in workplaces without security; for a time, the government actually dubbed them the “low-end population” (diduan renkou 低端人口) in policy documents aimed at demographic control.14 As such, they have long been counted among contemporary China’s most precarious people. What kind of change then—what electric jolt—might the evictions mark? Put another way, what does it mean to be officially banished from a place of already de facto exile? When I began this book, I intended it to be a study of the relationship between precarity and cultural practice in China. My aim was to explore precarious life and labor in China through the prism of the vibrant, iconoclastic cultural forms that chronic uncertainty has generated for some years now—from garbage art to protest performance over wage arrears to poetry from the factory floor. I was struck by how precarity, so copiously and P reface [ xi ]

contentiously theorized elsewhere, had only recently begun to enter the conceptual lexicon of China researchers, both inside and outside the country, except in the work of a relatively small number of dedicated labor scholars. Ultimately, I hoped to situate Chinese experience more centrally within our global understanding of precarity by exploring how frayed sureties are shaping multiple practices of culture in one of the world’s most populous nations. This project from its outset, then, was implicitly premised on the notion that Chinese experience, surveyed through a cultural studies lens, would deepen and sharpen the conceptual outlines of precarity as a universal key word of our times. Whether we understand precarity as a condition that arises essentially from labor practices—even as it fans centrifugally outward from work to envelop life more ineluctably—or as an ontological state that besets every person precisely because we are human and thus vulnerable to plague and pain, a study of China-as-precarious, I imagined, would add richer shading and nuance to these reasonably fixed parameters of debate. The Daxing fire and its subsequent evictions, however, cast matters in a different light. They made me wonder instead about the intensifying relationship between precarity and prolix forms of expulsion. Daxing District was a preeminent site of precarity well before the flames and the bulldozers engulfed it. Thereafter, it became something closer to a non-place, which it remains to this day; its former residents, meanwhile, can equally no longer be called by that name because their dwelling places have been demolished. Like the non-place they once inhabited, they were cast by the evictions into a limbo that impinged on their very right to existence. Their fate, as nomads of toil denied a berth in the city and sometimes even barred from return to the countryside, invokes questions about the limits of inequality and exclusion as meaningful descriptors of contemporary social plight. These limits have prompted Saskia Sassen to argue that we are now witnessing “the emergence of new logics of expulsion” in the global political economy.15 This new momentum “takes us beyond the more familiar idea of growing inequality as a way of capturing the pathologies of today’s global capitalism.”16 It recognizes that the language we use to describe immiseration and unbelonging on a systematic scale is too tepid. Crucially, Sassen defines expulsion in broad and open ways that extend from states of liminality to all-out exile: I use the term “expelled” to describe a diversity of conditions. They include the growing numbers of the abjectly poor, of the displaced in [ xii ] P reface

poor countries who are warehoused in formal and informal refugee camps, of the minoritized and persecuted in rich countries who are warehoused in prisons, of workers whose bodies are destroyed on the job and rendered useless at far too young an age, of able-bodied surplus populations warehoused in ghettoes and slums.17 Expanding the semantic reach of expulsion in this way has strong political potential, but it also elides a terminological, and again political, anomaly at the heart of the meaning of exile. To expel is to cast out: that prefix “ex” cannot sit idle if the term’s central meaning is to hold. This point can arguably be dismissed as a linguistic quibble if we simply counter that expulsion is never conceived in spatial terms alone, that casting out always encompasses modes of economic, social, legal, and affective excommunication too.Yet in an age in which national sovereignty norms make cross-border banishment almost impossible, the fact remains that those who are purged from the polis often have no next place to go. They must stick within the bounded territoriality of the nation-state, and often much closer to hand as land dispossession in rural areas across the globe continues apace. This presence-inabsence—this internal exile, by any other name—is a core precondition for my investigation here. The inability of contemporary states to export their surplus population to penal colonies, to cast it beyond a social pale from which there is no feasible return, or to discharge it into the sea like plastic waste means not only that civic death has to morph into new forms (the expanded expulsion of which Sassen speaks) but also that these mutations remain stubbornly visible within the normative social weal. As Matthew Gibney notes, banishment is supposed to be a ritualistically visual process: it “removes the offender from public view and thus decreases the likelihood of a spiral of revenge and retaliation that would upset the civil peace from those who have been harmed by unlawful acts.”18 When banishment cannot be executed in this visual way—which is to say, when society’s outcasts stay within its direct line of sight—the ritual of punitive purging is stymied in ways that do indeed “upset the civil peace.” This disharmony becomes all the more jarring when governments engage in flexi-expulsion: the process whereby people are exiled from the polis until they become useful again, suspended meanwhile in states of civic half-life. To be more precise, widespread internal exile in contemporary China via dispossession, disenfranchisement, and dislocation has created an aberrant socio-legal condition. I call this state of being zombie citizenship, and it P reface [ xiii ]

is a zone in which a significant minority of the nation’s huge population currently languishes. This term, with its explicit invocation of the living dead, is an attempt to conceptualize both the forms of civic nonpersonhood mentioned previously and—just as pertinently—their impact on those who, for now at least, are spared such a fate. The crucial backdrop to this notion of zombie citizenship is Article 1 of the Chinese constitution, which states: “The People’s Republic of China is a socialist state under the people’s democratic dictatorship led by the working class and based on the alliance of workers and peasants.”19 Symbolically enshrined at the vanguard of national life, and nominally protected by a panoply of other legal provisions, Chinese workers technically enjoy full, even special, personhood under the law. Yet many millions actually experience violent cognitive and material dissonance as both the national constitution and the law of the land are stripped of substance and made skeletal, if not spectral, in lives that are eked out in sliding states of expulsion and denuded of substantive safeguards.This, in part, is why their citizenship can be called “zombie.” It is the corroded carcass of the more fully fleshed civic identity accorded to those who belong in the polis by birthright. To an extent, the notion of the zombie citizen shares epistemological space with Susan Greenhalgh’s notion of “stratified citizenship,” with what Jieh-min Wu calls “differential citizenship,” and with Samantha A. Vortherms’s concept of “multilevel citizenship.”20 More generally, civic unbelonging in contemporary China can also be viewed usefully through the lens of denizenship, another spectrum-based category that denotes “partial insiders with limited rights”21—those who “dwell in the territory of the nation-state without formal citizenship status.”22 All are valuable terms, not least because they explicitly register the vital point that belonging and expulsion do not exist as simple in-out binary states but rather occupy a fluid continuum. As definitions, they are also less culturally loaded and inflammatory than “zombie.” Beings without speech, without agency, without free will, without rational thought, resurrected from the dead but devoid of human qualities—zombies epitomize the state of existing in mindless thrall to the dark power of others. In this sense alone, the term is surely an unacceptable usage for China’s already chronically disadvantaged people; it adds gross insult to grave injury. Furthermore, the usage becomes still more fraught at a time when foreign media representations so often harness the trope of brainwashing to describe the mental state of Chinese people in offensively blanket ways. For these twin reasons, I should make it clear from the outset [ xiv ] P reface

that I do not deploy the term “zombie” as a descriptor of people. Instead, I apply it, in the formulation of zombie citizenship, as a deliberately emotive definition of the states of civic abjection into which some people are thrust in our current precarious epoch. It is an enforced zone of existence rather than an embodied identity. Indeed, I settled on the term zombie citizenship because it captures the sense in which many working people in China, like the original zombies of Haitian folklore, are locked in forms of quasi–slave labor and cut adrift from the law, “existing only for the benefit of others and pushed to almost morbid exhaustion.”23 In an obvious sense, this makes their state fearsome because they have every right to seek revenge for the maltreatment they suffer: their insurrection, even if it never comes, always hovers at the edge of the horizon. Just as important, the notion of zombie citizenship is crucial to my analysis here because the zone of the living dead captures in gruesome shape the paradox of banishment when there is no “pale.” It embodies the threat and strife that surge when segments of society are effectively rendered into surplus matter yet cannot be physically purged, either because there is no next place or because their labor might prove useful once more. And finally, the precincts of the undead—not cast beyond borders but always close at hand and harboring the threat of contagion—metaphorize the fear that anyone and everyone in a society that applies the shields and shelter of the law capriciously might find themselves cast into a similar realm of civic half-being. And precisely because this fear is sometimes more hallucinatory than rational, the notion of zombie citizenship is its apt vessel. I argue that this ambient mood of civic jeopardy shapes the contemporary experience of precarity at its very core—and that China is a peerless, standout case study for tracking its outworking in culture. This is not to dispute for a moment that precarious feeling in China is also indissolubly tied both to labor practices and to human vulnerability at the deepest ontological level. On the contrary, it is yoked painfully to both those things. Those exiled to zombie citizenship are by very definition tethered to contingent, casualized work, and their lack of protection from the law leaves them defenseless and exposed in ways that touch excruciatingly on what it means to have, or lack, what Judith Butler calls a “grievable life.”24 But if we are to gain hard purchase on what it means to feel precarious in China over the last couple of decades, it is also crucial to consider the affective impact on society at large of witnessing at close quarters the process whereby state policies have effectively carved out an underclass consigned P reface [ xv ]

to zombie citizenship. To watch this process is to apprehend its menace. It is to wonder: Who is next? A growing body of scholarship on contemporary China has shown that a sense of trepidation—sometimes faint but difficult to dispel—trails the witching hours of even those who by certain measures should feel more privileged and secure but instead face an anxious mismatch between long-held expectations and their actual living or working conditions: university graduates, entry-level trainees, small-scale entrepreneurs, cultural creatives, IT employees, white-collar workers.25 This trepidation can be usefully conceptualized as a fear of the cliff edge: the slow slide or sudden tumble downward into states of penury, risk, and civic threat. And as it looms, the imminent fall exacts a socio-affective toll, breeding strife and friction between social classes. This besetting unease, and the conflict it stirs, is by no means exclusive to China, just as expulsion itself is a logic that runs rife across the planet. Yet Chinese experience can illuminate the condition of surety under siege in vivid, telling ways, and for a series of interlinked reasons. The vast size, and thus unmissable visibility, of China’s underclass; the dark memories, either firsthand or inherited, of the class violence that blazed during China’s still relatively recent socialist past; the strategic silencing of class as a category of political action even as a de facto caste system has steadily hardened, together with the sense of unease that such suppression of evident truths so often foments; the huge policy power wielded by the authoritarian Chinese state, a power, when it turns its hand to expulsion, that inevitably affects the most vulnerable the most absolutely; the long-term propagation of prejudicial discourses about “human quality,” and its supposed lack, which works to segregate China’s people into the civically deserving and the not; the emergence of a social credit system that proliferates the protocols for citizenship while remaining subject to potentially devastating algorithmic error; and the ever-tighter web of surveillance that monitors conduct and misconduct—this matrix of factors makes contemporary China an almost unparalleled site for the study of the cliff edge as a perniciously divisive structure of feeling. Here, once again, the Daxing fire and its aftermath are instructive. As several commentators have noted,26 the evictions caused real outrage across the social spectrum, sparking a petition submitted to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress,27 open letters with many signatories,28 WeChat posts, and social media furore.29 Eva Pils even argues that the case “marks a rare moment when advocates from different spheres of China’s segregated society came together to find a shared language of citizenship.”30 [ xvi ] P reface

If so, it was heartfelt anxiety over the civic death that had been meted out to the Daxing residents that animated this exceptional solidarity, as the petition made clear. That document argued that government actions had violated five constitutional rights (wu xiang xianfa quanli 五项宪法权利) of Chinese citizens, including “land rights, individual or private economic rights, private property rights, the right to the inviolability of human dignity, and housing rights.”31 As Pils puts it, “in calling for (greater) respect and inclusion of the evicted Daxing residents, their fellow citizens seemed to be articulating a civic ideal denied not only to these evictees, but also to Chinese citizens more widely, as well as a shared anxiety about the precarity of their rights as Chinese citizens.”32 Significantly, this outrage and solidarity also took filmic form, in the shape of a rough-hewn documentary by the artist-activist Hua Yong 华涌, titled After the Great Fire (Dahuo zhi hou 大火之后, 2017), that tracked the horror of the evictions in real time. Since 2017, a scholarly consensus has begun to settle around the idea that the evictions, despite the violent dislocation they enacted, also fostered fledgling shoots of civic awareness, social conscience, and interclass fellowship even as the prevailing political winds in China grew harsher. This, moreover, is a burgeoning that is constitutively cultural at its core, whether we understand this in terms of the petition and the claims it staked within public culture or in terms of an aesthetic movement, as exemplified by Hua Yong’s documentary. In many ways, this argument about a culture of solidarity is beguiling. It’s also a rallying cry with parallels across the globe in the work of the many scholars, activists, and artists who see shared precarity as the banner under which the divided multitudes can come together. In this book, however, I suggest a counter case. My argument begins here with the Daxing evictions of 2017, but in subsequent chapters it journeys back across the last two decades to amass a freight of cultural evidence that unsettles the notion that fear and dread of zombie citizenship will naturally tend to alchemize into camaraderie. In the case of Daxing, claims of broad solidarity with the evicted have arguably been overstated. So far scholarly attention has focused on the vibrant support for the evictees that was articulated on social media, often ingeniously as anti-eviction activists sought to outwit the cyber censors. But vital as this solidarity was, it tells only part of a sometimes bleaker story. For example, responses posted on WeChat and Weibo news accounts of major national and municipal media outlets that covered the story also reveal startlingly strong and varied popular support for the evictions. At the kinder end of the spectrum, netizens argued that buildings in Daxing P reface [ xvii ]

were unsafe and illegal and that demolishing them was the only way to prevent further loss of life.33 Others offered lavish praise to the municipal government for its strict enforcement of the law, while commiserating with officials for the tough job they do.34 Others again supported the evictions because Daxing residents were squatting against the law in a city already overrun with migrants who sully its image as China’s high-spec capital.35 Even harsher voices taunted, “Why don’t you just go home?” and “Lowend workers should just get out of Beijing.”36 All in all, out of 111 responses to twenty-one news articles, nearly 72 percent of posts and comments that I viewed on these mainstream news websites backed the Beijing municipal government’s decision to eject the fire-stricken residents of Daxing into a wintry November night. Of course, it’s more than reasonable to counterargue that these sites are precisely the kind of online spaces routinely targeted by China’s so-called 50 cent party, the virtual troops who pepper-spray cyber discourse with fake pro-state messaging. Indeed, a more extensive survey of 168 responses—this time scanning the comment sections of news articles posted on a broader range of sites, including Chinese major search engine Baidu 百度, as well as Guancha 观察, Epoch Times, Caixin 财新, and Sohu 搜狐—brings the picture closer to 50/50.37 Yet these numbers still throw significant shade on the rosy vision of surging multilateral solidarity. My aim is not to deny that the condition of zombie citizenship in China has the power to foster fellow feeling. Evidently, it can and does stir esprit de corps, and that sentiment holds intense, important value. But the focus on sincere support across class lines that has dominated analysis of the evictions—and plenty of scholarly work on other subaltern cultures in China—may be skewed disproportionately toward hopefulness. This bias, however well-intentioned, is epistemologically unhelpful; it forestalls a fuller analysis of how fear of the cliff edge can also eat away at our social sinews. In this book, I balance this rosiness with a different set of proofs, drawn from cultural practice, about the toll that state-sanctioned forms of expulsion can take on all its citizens. The case studies I present suggest that the ambient mood of jeopardy referred to earlier can also curdle into social poison as the specter of zombie citizenship begets strain and strife between social groups. China, its citizens are continually told, is a “harmonious society.” Indeed, the class struggle that wracked the Maoist years has been so thoroughly vanquished that even the very word “class” (jieji 阶级) has been rendered unsayable in what Lin Chun calls “a titanic act of symbolic violence on the part of the Chinese state.”38 Yet the conjunction of a society supposedly [ xviii ] P reface

without class and a huge caste of de facto untouchables is an anomaly so stark that propaganda can at best only paper it over. Precarity, as I define it here, spawns dark feelings that do not conveniently dissipate amid state hype about social harmony, and culture is a core space in which such emotions break cover. The threat or reality of the cliff edge is now a significant force shaping contemporary culture in its raw materials, its personnel, and its practices. In the chapters that follow, I explore ethically dubious performance art, the aesthetics of waste, poetry from the factory floor, suicidal protest movements, and short video and livestreaming apps. All are cultural forms created in the crucible of Chinese precarity and its fraught and divisive affects. More than this, these modes of culture are novel or breakout in terms of genre, shape, and emphasis. As such, they reveal how cultural expressions morph under the threat of zombie citizenship and the social frictions it stirs. But these cultural practices never merely represent class tension. They do not simply reflect it in some supposedly freestanding mirror of art. Culture, I demonstrate throughout this book, is a key site where class strife is physically staged in China, as precarious feelings turn garbage dumps and construction sites into vital vectors of the contemporary moment in which art and life cannot be disaggregated from each other. Crucially, these practices are born not of isolatable class categories—urban middle-class, rural-city migrant, and so on. Rather, they emerge from the generative clash between competing interests in an era when the loud rhetoric of the China dream is shot through with sotto voce intimations about how some must suffer, or even be sacrificed, if that fantasy is to be made real. As Elizabeth Perry has noted, divide-and-rule has always served the Chinese Communist Party well—and citizens themselves, partitioned into “separate state-created categories,” are schooled “to accept these divisions as a normal part of the political order.”39 If society is indeed harmonious, this is a tense and fragile peace predicated on a highly prejudicial pecking order in which everyone is racing to avoid the bottom rung. In this context, the works I explore can be understood as fractious forms: cultural expressions that emerge from tense encounters between different class actors under the fear or fact of zombie citizenship. Unfolding as they do in the zone of intersubjectivity, these cultural works always harbor the potential for fellowship. But just as often, they are the means via which rivalry, exploitation, protest, and control are articulated, and through which class difference is directly or obliquely asserted.These practices are frequently P reface [ xix ]

grimmer than many humanists would like cultural forms to be. But at the same time, they also testify acutely to culture’s role as a paramount space in which the political happens. And if culture can exercise this role so vividly, presumably at some point it might also exercise it more solidly for the good, as the latter is conventionally conceived.Yet perhaps such practices—despite or even because of their rebarbative character—should also be understood as vibrant expressions of agency among those who experience, or fear they will experience, a deadening of their capacity for will and action and subjecthood. At a time when the resourceful capacity of precarious people in China to manage their emotions is drawing scholarly attention, and when the notion of apathy-as-protest has gained ground,40 the fractious forms I examine in this book restore a sense of the unmanageable to precarity as a condition. They acknowledge that undisciplined feeling—antagonism of different kinds, in fact—is a legitimate response to the cliff edge as threat or reality. Dark feelings are creative, and never more so than when the right to civic belonging is at stake.

Acknowledgments

M

any people and institutions have helped, encouraged, and supported me in the writing of this book, and it is a pleasure to have the chance to thank them now. I owe a tremendous debt to the British Academy and the Leverhulme Trust for awarding me two consecutive fellowships that allowed me to work on this book for three uninterrupted years. The opportunity to focus solely on research and writing during that time enabled me to finish a project that would otherwise have taken me many more years to bring to completion. The KS Fund at Oxford made it possible for me both to conduct fieldwork in China and to convene an ongoing seminar series on Chinese visual culture at my institution, which helped to shape the direction of this book. I am also very grateful indeed to the friends and colleagues who invited me to present parts of the book through lectures, workshops, and conferences, both online and in person. Carles Prado Fonts and Xavier Ortells Nicolai invited me to Barcelona to give two talks on the project at an important moment for me. Barbara Mittler, Lena Henningsen, Sun Peidong, and Damian Mandzunowski organized a wonderful lecture series during the pandemic, and I very much appreciated their invitation to take part in it. I also thank Lennart Riedel for acting as such an insightful discussant for that talk. Conferences and lecture series convened by Ying Qian, Debashree Mukherjee, Laliv Melamed, Pang Laikwan, and Pamela Hunt allowed me to sharpen my thinking on the project in key ways, as did a wonderful [ xxi ]

symposium on “Fragile Lives” held at Ca’Foscari, University of Venice in 2022. I also thank Dolores Martinez, David Alderson, Carlos Rojas, Bo Ærenlund Sørensen, Mai Corlin, Chris Lupke, Maki Fukuoka, Peter Gries, Shiqi Lin, and Mei Li Inouye for inviting me to give lectures or join panels at which I learned a great deal. Astute comments from Clare Harris, Wu Ka-ming, Peter Cave, and Yomi Braester after these talks have made their way into this book. I am hugely grateful to Gloria Liu for superbly professional and multi-skilled research assistance, particularly in the latter stages of this project, when her contributions were crucial. Chris Berry, Michel Hockx, Jie Li, and Carlos Rojas gave me exceptional support at key moments (Michel on more than one occasion), for which I will always be grateful. I thank Wang Yi, Pan Yiyan, and Fang Zhilan for valuable input, advice, and discussions. Fabrizio Massini and I swapped chapters, and I suspect I learned more from our subsequent discussions than he did. Nicolas Lin offered valuable bibliographic suggestions, and Chen Ziru helped me get hold of some vital books, as well as offering insights into my research. Matthew Johnson read and talked to me about my previous work in ways that I very much appreciated, both now and then. Chris Mittelstaedt has kindly helped me many times with technological matters. Carwyn Morris shared unpublished work with me, and many stimulating exchanges on the subject of precarity.The same is true of Harriet Evans, who has been a longterm friend and mentor to me. For their friendship, inspiration, and kindness during the writing of this book, I thank—in addition to the friends and colleagues already mentioned—Gordon Barrett, Angela Becher, Paul Bevan, Keru Cai, Chow Yiu Fai, Irena Hayter, Erin Huang, Heather Inwood, Paul Kendall, Jeroen de Kloet, Song Hwee Lim, Qian Liu, Jason McGrath, Dirk Meyer, Astrid Møller-Olsen, Chloe Starr, Shelagh Vainker, Nicolai Volland, Justin Winslett, Jiwei Xiao, and Fan Yang. My current and recent graduate students Billy Beswick, Aoife Cantrill, Chen Ziru, Kate Costello, Annabella Massey, Flair Donglai Shi, Wang Hao, Wu Xiaochu, Yeo Min-Hui, and Zhu Linqing have created a warm and exciting research atmosphere in our field at my institution, and I have learned so much from all of them.Warm thanks go to Rosanna Gosi for being such a kind friend and colleague over the years. I owe a special debt of gratitude to colleagues who engaged with this book in unusually constructive and supportive ways. Patricia Thornton read large chunks of the manuscript and commented on them with her usual insight, erudition, and generosity, saving me from several missteps. Maghiel van Crevel read the whole thing and offered truly transformative advice, [ xxii ] A cknowledgments

encouragement, and inspiration, as well as unstinting practical help with everything from references to typos. Earlier versions of chapters 2 and 4 appeared in Prism:Theory and Modern Chinese Literature and Cultural Politics, respectively. I thank Duke University Press for permission to reuse that material. Thank you also to the anonymous readers at Columbia University Press, whose astute comments and suggestions on the book helped me to improve it. At the press, I have been very fortunate indeed to work with Christine Dunbar, whose expertise and efficiency have smoothed the way for this book, and with Christian Winting, whose patient advice has been invaluable. I am also very grateful to Ben Kolstad, for managing the project with such care, and to Kay Mikel for meticulous copyediting. As ever, my friends and family have supported me more than words can say. Thank you to my “big birthday” friends; to Ruthie and my parents— especially my father, who read every page; to my husband and best friend, Tom; and to my three sons, Sam, Max, and Alex, to whom this book is dedicated with much love.

A cknowledgments [ xxiii ]

ON T HE E D G E

Introduction Grasping the Precarious

We live in a class society in which the discourse of class has almost disappeared. — WAN G HUI , “TWO K I ND S O F NE W PO OR A N D T HEIR FU T UR E”

I

n her 2016 novella, Folding Beijing (Beijing zhedie 北京折叠), Chinese sci-fi writer Hao Jingfang 郝景芳 conjures an ingenious idiom for zombie citizenship.1 The story reimagines China’s capital as a collapsible structure that “folds” every twenty-four hours, like concrete origami, so each of the city’s three segregated social classes can have their waking, working time while others slumber in pharmaceutical pods. The stinger is that these moments in the sun are divided in horribly inequitable ways. The ruling class—the five million residents of “first space”—can enjoy the earth for twenty-four hours, while the epsilons of “second space” and “third space,” with far vaster populations, have inversely proportional access to air, food, and remunerated work. Those from “first space” are coiffed and smooth-skinned in their driverless cars, whereas the third-spacers, such as the novella’s hero Lao Dao 老刀, are famished waste pickers whose jobs lie under imminent threat of automation. In an interview, Hao Jingfang told the New York Times that the novella is about the idea that “people live together but can’t see one another.” Her aim in writing, she said (perhaps tactically), was to make readers “realize that there are so many invisible people in their lives.”2 I would suggest the exact opposite reading of Hao’s text. This is not a literary work about unseeable others. Rather, it ponders the dilemma of their extreme and confounding visibility. The collapsible city Hao imagines in Folding Beijing is a brutal futurist solution to the contemporary conundrums of banishment: namely, where can states warehouse [1]

their surplus human population in an era of strictly patrolled national borders? How might governments “cold storage” their social dross until their hard labor is needed once again? Folding Beijing deals laterally with this impasse in ways that echo Saskia Sassen’s expanded definition of expulsion as the subterranean logic of our times. Since space cannot invisibilize those who are unwanted, either temporarily or forever, let us turn to time for a solution. For some years now there has been a looming recognition that precarity as an experience of the labor market involves a violent shrinking and stretching of the temporal margins. As Tsianos and Papadopoulos put it, “precarity means exploiting the continuum of everyday life, not simply the workforce . . . [it] is a form of exploitation which operates primarily on the level of time.”3 In real terms, this tends to refer to the short duration of a job, the exhausting length of its shifts, the last-minuteness of a zero-hours gig, and so on. But Hao Jingfang explodes these conventional parameters of time to make access to the sunlit hours the mechanism through which a kind of flexi-expulsion can be executed. Workers are summoned when they’re needed and banished again when they’re not; their physical presence blights the eyeline for not a moment longer than necessary. The immiserated in Folding Beijing are literally out of time, zombified in cocoons for long stretches of the day until their shift—in which they slave for others—rolls around and they are reanimated once more. Technically, time keeps turning on its linear axis, but in practice it has become as territorially spatialized as a gated community within a social system that acknowledges the use value of its underclass only on a part-time basis. I begin with Folding Beijing here because, like the Daxing fire discussed in the preface, it captures in tight microcosm—this time within the realm of storytelling—the nexus of concerns that shape this book. At the heart of this nexus is the de facto underclass, which has been legislated into existence in China since the 1990s, and this introductory chapter opens with both a definition of this vast cohort and a rationale for dubbing it an underclass. I then discuss how this underclass has been carved out, focusing on how state policies have not simply institutionalized zombie citizenship but executed this process in ways that almost appear crafted to induce cognitive dissonance among China’s migrant workers in particular—a group whose size, relative youth, and labor potential gives them heightened visual prominence. China’s migrants endure psychic disjuncture on multiple fronts: neither rural nor urban, both vital to growth and made superfluous to it, they are [ 2 ] I N T RO D U C T I O N

told repeatedly that they lack “human quality” (suzhi 素质) even as superhuman demands are made on their stoicism, fortitude, and sacrificial labor power. This contradictory assault on subaltern personhood paves the way for practices of expulsion, in which long-familiar forms of inequality and exclusion cross over into more radical states of civic exile.With this in mind, I explore expulsion in contemporary China as a flexible and hydra-headed thing. It ranges from forced eviction to life-changing workplace injuries to the extraction of back-breaking labor without pay, but it is consistent in the way it deepens estrangement from the polis for those already condemned to lesser life. Small wonder, then, that China’s censors are nervy about the presence in popular culture of zombies—avatars of drudgery, social apartheid, and contagion—and have taken steps to exorcise the living dead from films and video games. Ultimately, zombie citizenship stirs disquiet because it emblematizes the riddle of indisposable waste. This is the paradoxical process whereby segments of society are rendered surplus yet remain within the body politic, either because it is no longer possible, as in olden times, to transport them overseas or across sovereign borders or, more commonly, because they retain on/off use value for the neoliberal authoritarian state despite their assigned status as social debris. Chinese society is already rife with many of the standard determinants of precarity. In this context, the growing number of social subjects—those cast into zombie citizenship—who remain acutely visible even as they are effectively excommunicated compels a deeper consideration of the relationship between feeling precarious and the fact or fear of expulsion. To reflect on this question is, on one level, to situate China more assertively within already-existing discourses on precarity, from which Chinese experiences have been perplexingly absent or at best underrepresented until quite recently. I consider why this lack has occurred, but I also argue that China and its experiences need to be understood not tangentially but as a central starting point for the conceptualization of precarity as a master term for the present. These experiences throw harsh light on the relationship between corroded certainties and civic exile. For a tight and specific set of reasons, they illuminate the pathway between precarity and expulsion in ways that have few direct global comparators. Above all, conditions in China offer a grim assemblage of insights into precarity as a sense, both intuited and grounded in the immediately observable world, that a life without access to core rights looms like a precipice I N T RO D U C T I O N [ 3 ]

not just for the few but potentially for the many. That feeling of menace is rooted in the vagaries of the law. From labor legislation that is among the strictest in the world but often does little to protect actual workers, to household registration reform that promises improved equality but makes mostly cosmetic changes on the ground, the law of the land can appear fatally fickle both to China’s underclass and to others who witness its surely strategic nonenforcement. This is not to suggest that the state is willfully indifferent or callous about the plight of China’s underclass. As I make clear, the picture is much more fluid and nuanced, and the reasons for the caprice of the law can be complex. Furthermore, the Chinese government is increasingly aware of the perils of unchecked inequality as recent leveling-up initiatives demonstrate. Yet the anxiety stirred by an ongoing sense of caprice is nonetheless a core constituent of the structure of feeling I probe in this book. This apprehension throws a shadow, I argue, that darkens the cast of social relations in China at a historical juncture in which class tension is already taboo. This shadow forms the backdrop to the surge in dark feelings the Daxing evictions unleashed alongside the heartwarming—and much betterdocumented—solidarity that has emerged. In this introduction, I acknowledge the vital role that NGOs, politically engaged researchers, public intellectuals, lawyers, students, and artist-activists have played, and continue to play, in bolstering commonality both across the class divide and within social cohorts. I also try to navigate a path through the minefield of what Sherry Ortner has called “dark anthropology”: academic work that looks so long and hard at “the harsh and brutal dimensions of human experience” that it can become almost rubbernecking in its scrutiny.4 Yet the fact remains that contemporary Chinese society poses a well-documented quandary, and the dark and divisive feelings I parse here may illuminate this in certain ways. Only a century ago, China was fomenting socialist revolution on a globally epic scale. As new-left thinker Wang Hui has argued, the “general societal mobilization” and vast sociopolitical change that the nation experienced across key decades of the twentieth century arose in no small part “at the boundaries between classes where they overlapped . . . it was the product of crossing the boundaries between classes.”5 Activists traversed caste lines to incite political action, and that crisscrossing movement fostered a solidarity that was often radically transformative. Today China is home to the largest underclass in human history, and it is physically concentrated in the cities of the eastern seaboard and thus logistically well-primed for concerted action. [ 4 ] I N T RO D U C T I O N

But the people who make up that huge dispossessed group remain mostly unaligned, if not actively disunified, and cross-class solidarity, beyond a small number of well-documented projects, is in limited supply. In the era of the China dream, amid mantras about the harmonious society and the elimination of chronic poverty, tensions between different castes and cohorts are, in fact, rife and rising. This abrasive socio-emotional texture both links and segregates classes, and it is the focus of my case studies in this book. I suggest that zombie citizenship—as a lived reality for some, as a more or less imminent peril for others—seeds divisiveness as much as indictments of it bolster unity across society. In part, the limits of solidarity have been laid bare by the actually occurring contagion of several core traits of zombie citizenship into populations that might previously have considered themselves secure. China’s aspirant middle classes, in particular, face new travails: slum dwelling, informal work, bruisingly long hours, and concomitant sleep deprivation so acute that it has become a media phenomenon. Marginalized workers hooked on mostly unfulfillable dreams of climbing up the ladder, and a middle class consumed by entirely plausible fears that they will plummet downward, produce social conditions that may be congenitally inhospitable to solidarity, both within and still more acutely between different groups.6 In its place, enmity rises. Sociologists and anthropologists have begun to document this surge of rage and resentment in postmillennial China using the modes of inquiry specific to their disciplines: ethnography, participant-observation, in-depth interviews, and so on. In contrast, I propose an approach which argues that cultural forms offer an equally relevant purview of the social toxins that foment zombie citizenship. Artworks, photography, poetry, film, performance, and social media are material forms in which the affective dynamics of the cliff edge are made concrete. They are artifacts on which zombie citizenship lays heavy traces, and for that reason they are crucial tools for the analysis of expulsion as a determining logic in China today. My case studies show that, in a party-state that wants to prescribe happiness and proscribe hostility, cultural practices often serve as a stage on which stifled class tensions burst through. These practices, surfacing across many different media, become spaces of volatile encounter in which different class actors face each other in postures of grievance, anger, resentment, rivalry, or disdain. These stances do not tell us anything close to the full story of how people menaced by zombie citizenship in China interact with one another. I N T RO D U C T I O N [ 5 ]

Telling the full story, if such a thing were possible, would require multisited, multimethod, multidisciplinary, multiauthored work. Rather, this study presents a series of detailed, focused snapshots taken from the field of culture that I hope might counterbalance other kinds of research findings that point to a different picture: heartening, cordial, more humane. I document these fractious forms in part because their disturbing energies may make them less agreeable objects of study than the work of culture-oriented NGOs seeking to empower dispossessed groups in China. In the field of cultural studies— particularly research on migrant workers—a discernibly upbeat tone has shaped the production of knowledge about cross-class relations in recent years. As a ballast to this, the case studies here quite deliberately work with a darker data set. I also document these fractious forms because they demonstrate that cultural practices do more than simply represent social strain under the regime of zombie citizenship. As orchestrated encounters between different class actors, these practices actively combust tension in interventionist and immediate ways. They are sites in which art and politics collide fractiously, even transformatively. As such, they often take novel or unconventional form because the vehement encounters they stage are not always easily containable within established formats. Full of friction and unorthodox in form, these works unsettle harmony, and for that reason, they are often subject to discipline or regulation. But plenty also enjoy success, and those successes suggest that audiences have a felt need to witness the playing out of the person-to-person conflicts these practices perform. Indeed, these conflicts are tellingly horizontal in the sense that the sentiments to which they give cultural voice are directed not at the state—wherein much responsibility for the cliff edge surely lies—but at fellow members of society. This directionality may appear counterintuitive. But it makes more solid sense when we consider that a certain tolerance for the logic of sacrifice—in particular, the forced martyrdom of the powerless—is a core feature of societal understandings of China’s rise and its human costs. And in the struggle not to be culled, those nearest to hand are one’s most obvious opponents. Yet this antagonism is also multivalent, and although the cultural practices I explore are often bleak in their symbolic or actual violence, I conclude that their force of feeling asserts the vivid agency of precarious people—and their inalienable, furious right to resist that precarity.

[ 6 ] I N T RO D U C T I O N

All in a Name Whatever their aesthetic form, the works I discuss here all stem from the same precondition for zombie citizenship and the angst it generates: the carving out of a de facto underclass in China. The creation of this underclass—even though it tends to go by other, more socially acceptable names—shows that a cliff edge divides those who are citizens from those whose hold on rights is tenuous. Moreover, this precipice is not a naturally occurring geological formation so much as it is an artificial edifice constructed in significant part by governmental policy since the 1990s. China’s underclass, as I define it here, consists of laid-off workers dismissed from state-owned enterprises; landless peasants; those with disabilities and unable to work; unpensioned retirees; others who have fallen into homelessness or indigence, including recipients of the minimum livelihood allowance (dibao 低保); and, perhaps most important, the rural-to-urban migrants who work in factories, on construction sites, and in various branches of the service industry.7 In Chinese-language discourse, both official and academic, these social groups are often collectively dubbed “lowest stratum” or “subaltern” (diceng 底层), although the euphemism “disadvantaged communities” (ruoshi qunti 弱势群体) has gained traction since the millennium.8 Rural-to-urban migrants, who numbered more than 290 million in 2019 according to the National Bureau of Statistics, are known by several further monikers: “peasant workers” (nongmingong 农民工), “those who sell their labor,” mostly as migrants (dagongzhe 打工者), and “new workers” (xin gongren 新工人), each with specific socio-semantic connotations.9 To argue that these varied and amorphous groups constitute an underclass is inevitably a contentious claim, and not simply because this terminology chafes against the naming grain in China itself. Just as significant, the usage is controversial because of the taint of infamy that routinely sticks to the word “underclass.” As Michael Katz notes of the U.S. context, the term conjures “a mysterious wilderness in the heart of America’s cities; a terrain of violence and despair; a collectivity outside politics and social structure, beyond the usual language of class and stratum, unable to protest or revolt.”10 It is a shadowland in which hustlers, criminals, drifters, addicts, and dropouts loiter. By close association, it is the natural habitat of the lumpenproletariat as Marx defined them in The Eighteenth Brumaire: “vagabonds, discharged

I N T RO D U C T I O N [ 7 ]

soldiers, discharged jailbirds, escaped galley slaves, swindlers, mountebanks, lazzarone, pickpockets, tricksters, gamblers, maquereaux (pimps), brothel keepers, porters, literati, organ grinders, ragpickers, knife grinders, tinkers, beggars—in short, the whole indefinite, disintegrated mass.”11 As Charles Murray, controversial new-right proponent of the term, puts it, “underclass is an ugly word,” in large part because of this “whiff of Marx and the lumpenproletariat.”12 Underclass implies an ill-assorted horde, disconnected from productive activity, devoid of class consciousness, in thrall to whim rather than driven by political agency. It is not surprising that the term has been variously critiqued, and perhaps most salient is the accusation that it has lost its socioeconomic structural valence and become instead a cipher or dog whistle for behavioral “deviance,” often with a racist tinge.13 But it is precisely this waylaying of the term from its origins in social structure that provides the path to its reclamation, and most strikingly so in the case of China. The much-circulated usage of diceng (subaltern) is in its own way another weasel word for the realities of systemic socioeconomic disenfranchisement. This phrase deploys the character ceng, meaning stratum or layer, to imply an inclusive social escalator in which the prefix di, meaning low, is merely a current predicament. In a society organized into interconnected tiers, mobility is the organizing doctrine. There is no such thing as being outside, let alone beneath, the system; everyone belongs on the inside and can move up if they try hard enough. In lived reality as opposed to official discourse, however, a state of quasi-permanent externality is precisely the fate endured by the groups I have mentioned to whom even the bottom rung of the ladder upward can seem structurally foreclosed. It is in this sense that the term underclass is not just appropriate but in urgent need of rehabilitation, because it is the only descriptor that both acknowledges the hard logic of expulsion and does so on the basis of class as a mechanism for discriminatory segregation—a notion that, as I will discuss in more detail later, has been effectively outlawed in contemporary China. If social stain can be expunged from underclass as a term, its blunt descriptive realism—its refusal of euphemism in a discursive context determined by doublespeak—may possess exactly the utility required to begin to investigate zombie citizenship as both fact and fear. This is because underclass, if parsed literally, captures the anomalous condition whereby certain people can be “of ” society without being “in” society. Unlike other semi-equivalent terms, underclass brings the cliff edge into view. Small wonder that the [ 8 ] I N T RO D U C T I O N

closest Chinese equivalent for the term underclass (xiaceng jieji 下层阶级) is not in common use in state and public media. But this lexical squeamishness makes the space below, a zone under the rest of society, no less fearsome. As Li Qiang 李强—a leading sociologist based in China who does frequently deploy the term underclass—has noted, this group forms an inverted “T-shape”: an orthographic figure whose right angles recall the cliff edge, even if Li’s meaning is rather different. Using data from China’s fifth national census of 2000, Li argues that as much as 64.7 percent of China’s working population occupies “an extremely low” socioeconomic position, thus creating not the standard “pyramid” or “olive” social structures familiar elsewhere but a tense formation consisting of a narrow pillar of people with rising privileges and a vast underclass below bleakly differentiated from the favored few (figure I.1).14 And in the years since that millennial census, inequality has only deepened.15 This leaves unaddressed the other major criticism leveled at the term underclass: namely, that it performs a blanket homogenization of marginalized groups who are too disparate to group meaningfully together. China’s migrant workers, for example, subdivide into many smaller groups whose access to citizens’ rights shuffles down a sliding scale: from long-term urban

Figure I.1 Li Qiang’s inverted T-shape, aka the cliff edge. I N T RO D U C T I O N [ 9 ]

residence permit holders, to legitimate temporary residents, to so-called ghost workers (youling gongren 幽灵工人)—“either unregistered in the local population governance system and/or uncovered by the social insurance system”16—to those who are downright illegal, sans papiers, or falsely registered. On this basis, Jieh-min Wu argues for the notion of “differential citizenship” among migrants, or a “pattern of segmented . . . allocation of citizens’ rights and entitlements.”17 Just as pertinent, migrant workers and the long-term urban indigent hardly share a seamless identity, and they may even nurture hostility toward one another. Mun Young Cho, for example, has explored the volatile tensions between these two groups on the streets of Harbin and argues that their increased intermixing and shared privation have mostly proved divisive.18 What’s more, they “voice their grievances not against the state but against one another.”19 This friction is rooted in difference and the threat it carries. Unlike laid-off workers, retirees, and the disabled, many rural migrants are employed, young, and without disabilities. They travel to the cities full of hope and energy and labor power.20 They are as many as 300-million-people-strong and thus surely harbor the potential for class formation. Indeed, it is partly in realization of this fact that one of the descriptors for rural-to-urban migrants—“new workers”—has gained ground in certain circles over the last decade or more. As promoted by worker/scholar-activists such as Sun Heng 孙恒, Lü Tu 吕途, and Wang Dezhi 王德志, the term is linked to self-empowerment, the dignity and sovereign value of labor, and the desire to foster class consciousness—as well as marking a clear semantic break with both the pejorative overtones of other terms and the “old workers” of the command economy.21 But despite this heterogeneity, the constitutive presence of new workers within the underclass remains central to my argument about civic dispossession. Migrants may not experience the denial of rights identically, but they are alike in that they endure the exclusionary bent hardwired within citizenship regimes in China. As Wu puts it, the “differentiating principle serves as a driving force in lieu of the universalizing principle widely recognized in the context of typical market capitalist societies” (emphasis in the original).22 This means that “it is a long, bumpy road for a migrant to achieve full urban citizenship, a road that few travel.”23 Furthermore, a major part of the tension between newcomers and the impoverished urban old guard stems from the intense struggles they experience precisely because they are castaways from the circle of rights. Cho argues, in fact, that their pauperization is managed on the ground by municipal policies that actually, if [ 10 ] I N T RO D U C T I O N

not always purposefully, divide these people from one another as a strategy of rule.24 And last, new workers should arguably be counted within the underclass not despite but because of all the visibly potent attributes they possess—qualities that so far have proved unable to lift them securely and consistently over the bar into full civic belonging. As such, it might even be argued that the new workers most starkly emblematize zombie citizenship in all of its paradoxes: they show how some of the nation’s most vigorous people can still routinely be made surplus—kept external to the system— even as that system keeps on extracting blood, sweat, and tears from them. This, after all, is the insistent antilogic of the zombie, who toils for others while being denied the stable civic rights labor should entail. And when catastrophe strikes, it is China’s migrant workers who find themselves instantly cast adrift, their small gains wiped out—whether this is in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, when unemployment in this group skyrocketed;25 or during the Covid-19 pandemic, which exposed “a serious mismatch between workers covered by the social safety net and those who really need it . . . [and] exacerbated the preexisting inequalities along the household registration system line.”26 No doubt other arguments could be marshaled against the term “underclass,” and I use the descriptor in full awareness of that fact, despite the rationales previously set out. Part of the reason euphemisms, contested nomenclature, and new coinages abound in the description of marginalized people in China is because no term exists that can encompass these groups in fully satisfactory ways. Any portmanteau descriptor can only falter in the face of such dense demographic complexity. Ultimately, the term underclass may commend itself not because of empirical or theoretical accuracy but because it captures the affective tenor that the presence of so many disadvantaged groups in a given society summons during an era in which many others sense the tenuousness of their own hold on rights and livelihood. Partly because it is evidentially flawed and emotionally inflammatory (rather like “zombie,” in fact), underclass catches that visceral fear of falling, the shaky sense that a space yawns below. That fear may not seem entirely rational, not least because state rhetoric of upward mobility and the Chinese dream explicitly denies it. But it is no less intense for that, as the case studies I explore attest. For a project such as this, which explores how civic threat and social strife reach for expression within the more free-form spaces of culture, a term is required that can gauge or grasp at this freight of tense, unpredictable feeling. Indeed, as I discuss next, both cognitive disjuncture I N T RO D U C T I O N [ 11 ]

and emotional strain are crucial to the experiences of zombie citizenship and its passage into culture.

Untermensch, Übermensch At the core of this sense of tension is the strategic illogicality through which China’s underclass experiences its disenfranchisement. I argue that the government policies that have helped to create the cliff edge—in particular, the rolling back of the command economy and the inequities of the household registration system—have not simply resulted in what Sassen calls a “savage sorting:”27 that is, the division between the “haves” and the “have-nots” of material wealth and, more tellingly, the “ares” and the “are-nots” of full citizenship. This partition is, of course, the core determinant of zombie citizenship. But it is not, in itself, enough to explain the latter as a divisive structure of feeling. Zombie citizenship is not simply about the withholding of rights; it is also shaped by the implementation of that denial—by the sometimes disingenuous ways in which the excommunicated are made to process their exile from the law and its protections. These make zombie citizenship very much a matter of mind and emotion. This is why it can readily catalyze into interpersonal strife and distrust, and this is also why it is insufficient to document state policies in empirical terms alone. In this connection, I argue that the cliff edge has been constructed in ways that militate toward states of cognitive dissonance: the condition of jarring mental instability that results when a subject holds beliefs or values that clash with one another, or when personal convictions and lived actions or experiences do not align with one another. This psychic disjuncture, consistently applied, intensifies the impact of zombie citizenship. In this section, I sketch the state policies that have carved out the cliff edge and focus, in particular, on the cognitive dissonance these policies induce. As is well known, the era of reform and opening up that began in 1978 created a nexus of push-and-pull factors that, over the following decades, caused Chinese peasants to surge to the cities in sustained waves of migration unparalleled in human history.The journeys these rural people made to the megalopolises of the eastern seaboard seemed to be a stunning affirmation of their freedom of movement and were undertaken with that express purpose in mind. But the realities of China’s household registration system cracked open a chasm between physical kinesis and its social variant. Under [ 12 ] I N T RO D U C T I O N

this system, most migrants have been historically unable to access employerprovided health care; many do not receive pensions and other work-related benefits; their children cannot attend local schools; they cannot settle meaningfully in the city.28 Thus, although permitted and indeed encouraged to leave the countryside en masse, most rural migrants have found their new workplaces—urban factories, mines, construction sites, and so on—to be sites of social stasis in which prejudicial policies prevent them from substantively improving their life chances. Enticed to the cities by a welter of state messaging about the promise of a modern identity deliverable only in the cities,29 migrants have experienced cognitive dissonance as a sharp disjuncture between physical and social mobility, between the bait of middleclass belonging and the steel trap of underclass drudgery. Their determined quests for personhood overwhelmingly end in actualized nonperson status. This disjuncture is registered in the name most commonly used to describe China’s migrant workforce: peasant worker. This term is a brazen oxymoron, a hybrid of peasant/rural and worker/urban that once again seems tailored to entrench cognitive dissonance—this time via repeated semantic befuddlement—because it is impossible to till the soil in one’s native village while at the same time assembling parts on a Foxconn short-cycle production line.30 The oxymoron is even more grating given that the peasant hinterland is now so often a place of no return: devoured by land grabs while simultaneously slip-sliding into what Miriam Driessen calls “rural voids,” places “denigrated in people’s minds as being empty of significance and meaning . . . [that] signify the contempt for, and neglect of, rurality in an urban-centered world.”31 Below this lies a deeper split that touches on the very project of statestewarded mass migration from the countryside. Ann Anagnost skewers the dilemma as follows: “Uprooted from collectivized agriculture, China’s migrant labor becomes the condition of possibility for capitalism’s renewal even as it represents the antithesis of development.”32 Put another way, migrant workers in China labor under the joint burden of intense market demand and acute social disdain. They are both wanted and unwanted, essential and supernumerary, useful because of their vast numbers yet for that same reason individually nugatory within the grand calculus of worth. More than this, they emblematize the problem of zombie citizenship because of a split between cost and profit in which “the undervaluation of migrant labor is what allows for the extraction of surplus value enabling capital accumulation.”33 This is Kam Wing Chan’s point when he calls rural I N T RO D U C T I O N [ 13 ]

migrants China’s “special forces” but also a group whose labor has been “super-cheapened.”34 This is a double-vision, split-screen reality in which cognitive dissonance thrives. To complete the picture, migrant workers are the long-standing target of twin propaganda drives seemingly contrived to enhance this already existing sense of disorientation. On one hand, migrants have low “human quality,” and so must do the nation’s “3D” jobs: dirty, dangerous, and demeaning. But on the other, they are the titanic master builders of postsocialist China, the workforce on whose superhuman strength, endurance, and selflessness the nation’s ascent to superpower status relies. Cognitive dissonance for migrant workers, then, is the state of being both mobile and gridlocked, neither rural nor urban, simultaneously crucial and surplus, at once Herculean and abject. Collectively, these symptoms flesh out the central paradox of zombie citizenship, in which workers are granted certain attributes of life in the polis—principally the right to toil—but are deprived of the agency required to make that life “full,” in Giorgio Agamben’s terms.35 In a sense, therefore, they are natural successors to the cognitive dissonance China’s laid-off workers endured in a slightly earlier epoch. The tens of millions of urban workers who were dismissed from their positions in state-owned enterprises during the 1990s became disadvantaged, as Dorothy Solinger has noted, “not by chance or by any fault of their own, but intentionally as a result of state decree” (emphasis in the original): they were “officially appraised as unsuited to participation in the modern industrial giant China is striving to become, and so were deliberately severed from their work posts in the interest of industrial restructuring and upgrading.”36 But Solinger is also correct to note that these former workers have acquired, as a kind of sour compensation for their many losses, a truer sense of where they really stand in the polity. Once upon a time in the Maoist era, these workers were “manipulatively socialized”37 into believing that they were the rulers of the socialist universe, even though they were living and laboring under conditions that blatantly gave the lie to that conviction. In the postsocialist present, in contrast, they have been liberated not just from their livelihoods but from false consciousness too—cognitive dissonance by any other name. These two large groups within China’s underclass—the vast migrant workforce and the legions of the laid-off—show that there is a road map to cognitive dissonance, with the fate of the latter foreshadowing the even bleaker future of the former. We see this path unfolding in recent incidents such as the Daxing fire, in which migrants were physically expelled from settlements because they had outlived their usefulness, in a move even more [ 14 ] I N T RO D U C T I O N

brutal than the laying off of workers from industrial plants in the 1990s when their value to China’s modernity had expired. Indeed, laid-off workers now endure “enlightened” destitution, as the illusion of political supremacy that once sustained them has been snatched away, while migrants whose labor has been accorded almost no quantifiable dignity at all are expected to swallow dogma in state and public media that eulogizes them “as willing, docile, laboring bodies contributing to urban development.”38 Meanwhile, those who watch the evolving fate of migrant workers from their own unsteady perches in the middle classes—subsisting in the gig economy although possessed of advanced degrees they were told would bring steady, wellremunerated employment—can glimpse their own expendability ahead. Cognitive dissonance, as a condition with a genealogy that reaches back into the socialist period, arises initially from a sense of trust in the powers that be. But as belief and action begin to bifurcate, and split consciousness sets in, that faith can oxidize into the sense of social threat that animates the cultural practices I investigate here.

Surplus-ing as Strategy Ultimately, that threat solidifies around the knowledge that underclass status in contemporary China can sometimes bring outcomes more extreme than inequities in health care, benefits, education, unemployment, and poverty. These injustices brought about by the household registration system and the brutal shift to the global market unquestionably disqualify members of the underclass from full citizenship, but they still arguably belong with the recognizable remit of inequality and exclusion. What’s more, as Xiang Biao has pointed out, workers in China would never have left their rural homes in the first place unless they both anticipated and later realized at least some value from that risky endeavor, however limited or unpredictable such benefits might turn out to be.39 But for some, the risk does not pay off. And to gain full purchase on zombie citizenship, we need to move beyond the familiar landscape of inequality and exclusion to the spaces below. These are the zones of expulsion, into which many Chinese workers—already marginalized, long beset by cynical mixed messaging—find themselves cast. These domains of expulsion may be temporary or permanent, but their most salient feature is their range and the pressure this variety applies to standard definitions of casting out. In this section, I set out some examples I N T RO D U C T I O N [ 15 ]

of expulsion, with a view toward offering snapshots of this state rather than an exhaustive panorama. In some cases, expulsion in contemporary China occurs along the standard spatial axis, as the events in Daxing show all too clearly. In one sense, those evictions of 2017, newsworthy though they were, can be seen as yet another iteration of what has become a perennial policy of upheaval enforced on marginalized people in China. Demolition and relocation, or chaiqian 拆迁, is a state-endorsed process of aggressive gentrification in which lowincome residents—laid-off workers, street vendors, service workers—are “cleansed” from poor-quality accommodation often situated in high-value urban locales. These dwellers receive notice that their homes have been earmarked for demolition, and they are offered either financial compensation or the chance to move to alternative housing. In practice, chaiqian all too often exemplifies Sherry Ortner’s point that “neoliberalism seems to foster a kind of contemptuous attitude toward the working classes and the poor beyond the necessity for profit.”40 Thus the compensation offered is unduly meager; the alternative accommodation is half-built or lies many bus rides away; and most troubling, those who resist are subjected to the threat or reality of violent removal (yeman chaiqian 野蛮拆迁): cut off from water, electricity, and gas, dragged from their homes, even assaulted by wrecking crews. As You-Tien Hsing has noted, residency never simply denotes one’s place of dwelling. Rather, it is “the physical anchor for the quotidian support networks of job, family, community, and urban services”—what Hsing describes as “life-worlds.”41 The loss of residency through chaiqian is, therefore, to bludgeon that delicately veined human ecology. The urban historian Qin Shao is gesturing toward the same kind of tragic liquidation when she coins the term “domicide” to describe chaiqian in Shanghai since the 1990s,42 as is Harriet Evans when she dubs it “a process of physical, spatial, and social erasure of local lives.”43 To an extent, these interventions pick up Saskia Sassen’s gauntlet that “the spaces of the expelled cry out for conceptual recognition.”44 But the Daxing evictions also shine a light on chaiqian as a specific, although not exclusive, migrant experience. As is amply documented, much migrant housing in China is already marginalized, hazardous, and marked by social stain. It is situated mostly on the ragged urban fringe; basement, tunnel, cellar, and other forms of damp, dark, and crowded underground dwelling are common; and scarcity has even forced some migrants to make their homes in shipping containers or civil air defense shelters transformed into [ 16 ] I N T RO D U C T I O N