Modigliani: The Primitivist Revolution. Exhibition catalog of the Albertina, Vienna 377743566X, 9783777435664

This richly illustrated volume places Modigliani at the front of the avant-garde. Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920) moved t

126 30 129MB

English Pages 216 [211] Year 2021

Cover

Contents

Foreword

Modigliani, Picasso – The Primitivist revolution. The centenary of an avant-garde artist

Modigliani-Picasso: Two visions of primitivism

Brancusi and Modigliani

Catalog

The birth of the caryatid: The simplification of the subject

Simplification towards a universal model: The load-bearing structure

Expressive intensity

The body in Modigliani’s art

Neck and nose: Their influences

The face and the mask

Chronology

List of exhibited works

Image credits

Recommend Papers

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

/

The

Primitivist

Revolution Edited by Marc Restellini With aforeword by Klaus Albrecht Schroder and essays by Friedrich Teja Bach, Juliette Pozzo, and Marc Restellini

ALBERTINA

HIRMER

This exhibition is made possible through the support of the Musee National Picasso - Paris.

Foreword

Klaus Albrecht Schroder

6

Marc Restellini

11

Modigliani, Picasso - The Primitivist Revolution

Juliette Pozzo

31

Modigliani - Picasso: Two Visions of Primitivism

Friedrich Teja Bach

39

Brancusi and Modigliani CATALOG

Marc Restellini

55

77

99

The Birth of the Caryatid: The Simplification of the Subject Simplification Towards a Universal Model: The Load-Bearing Structure Expressive Intensity

121

The Body in Modigliani's Art

137

Neck and Nose: Their Influences

171

The Face and the Mask

193

Chronology

210

List of Exhibited Works

...

Foreword Cimetiere du Pere-Lachaise. On this final journey, he was accompanied by his friends, the most renowned artists of Montmartre and Montparnasse: Pablo Picasso, Constantin Brancusi, Andre Derain, Max Jacob, Mo'ise On the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of Amedeo Modigliani's

Kisling, Jacques Lipchitz (who made the death mask of the deceased),

death, the Albertina commemorates this remarkable twentieth-century

Andre Salmon, Cha'im Soutine, and Maurice de Vlaminck. All of Montpar-

artist with an extensive exhibition. This is part of a series of exhibitions

nasse lamented the death of its "prince:' Not until 1930 were the remains

put on by the Albertina featuring pioneering artists of modernism. The

of Jeanne Hebuterne exhumed and laid to rest alongside Modigliani.

exhibition is again dedicated to an artist represented in the Albertina's collections with a major work: in this case the Female Semi-Nude from

historian and Modigliani expert Marc Restellini as curator of this exhibition.

the Batliner Collection (cat. 71), painted in 1918 during his exile in Nice.

The author of the soon-to-be published catalogue raisonne of Amedeo

The exhibition, which includes loans from three continents, was

Modigliani's paintings, he has contributed his exceptional expertise on

originally planned for the anniversary year of 2020. Like so many others,

the authenticity of the loaned works. And thanks to his close contacts

it had to be postponed for ayear due to the restrictions brought about by

with numerous important private collectors of Modigliani's rare works,

the COVID-19 pandemic. I am therefore all the more pleased that this

our exhibition has been generously supported by many private collectors

major exhibition dedicated to Amedeo Modigliani will take place at the

from around the world. His decades-long research on Modigliani's oeuvre

Albertina in autumn and winter 2021.

and experience curating some of the most significant exhibitions on this

My deepest gratitude thus goes to all the lenders, in particular the

artist in France, Switzerland, Italy, Russia, and Japan, has enabled him to

Stiftung Jonas Netter, the Paul Alexandre family (represented by Nathanson

contribute a very particular focus in terms of content to the project. In

Fine Art, London), the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Mu-

this exhibition, Marc Restellini has situated Modigliani at the center of

seum of Modern Art in New York, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the

what can be termed a"revolution of Primitivism;' placing him in a line

Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Musee National Picasso in Paris, and all

with the leading members of the Paris avant-garde, from Pablo Picasso

the other museums and private collectors who prefer to remain unnamed.

to Constantin Brancusi to Andre Derain. "Primitivism" here denotes astyle

In the midst of this crisis they have supported us, prepared the loans for

and an epoch, similar to the stylistic terms of"Classicism," "Impressionism;'

us, and provided the artworks now for the new exhibition dates.

or"Fauvism;' notwithstanding the fact that the high art of monarchies-

Modigliani was only thirty-five years old when he died in 1920 from tuberculous meningitis. He is counted among those famous artists who

6

It pleases me enormously that we could count on the French art

from the Khmer to the magnificent artworks of African kingdoms and tribes-provided the sources of inspiration for Western art.

met an untimely death, such as Raphael, who succumbed to the plague

When Modigliani arrived in Paris in 1906 as a young, academically

at thirty-seven; Schiele, felled by the Spanish flu at twenty-eight; or

trained painter, Picasso was there already, just beginning to supplant

Keith Haring, who died of AIDS at only thirty-two. Despite the brevity of

Fauvism and prepare the way for Cubism with his work Les Demoiselles

their lives, they all created extraordinary works of art and rank as great

d'Avignon. Modigliani moved in Picasso's circle at the Bateau-Lavoir on

pioneers.

Montmartre, even if the two solitary artists were not bound by close

Modigliani's early demise was, at the same time, a particularly

friendship or acommon agenda. Under the impact of the Paul Gauguin

tragic event: he died suddenly of consumption-the epidemic disease

retrospective at the Salon d'Automne in 1906, the Fauve painters Matisse,

of the nineteenth century-on January 24, 1920, in the Hopital de la

Vlaminck, and Derain were the first to become seriously interested in the

Charite in Paris. He was overcome unexpectedly, as he had several times

art of foreign cultures brought to Paris by colonialism and which had

before staved off this disease that afflicted him his entire short life. Jeanne

then already been displayed in Paris museums for over thirty years,

Hebuterne, who had a fourteen-month-old daughter with Modigliani,

ignored by contemporary artists. They found in the starkly expressive art

and who had been repudiated by her family for being an unmarried

objects what for them were the essential themes of life, handled with as-

mother, died two days later: she plunged to her death from her parents'

tonishing freedom, and yet had been shunned in Europe. This helped

apartment on the top floor of a building in the rue Amyot, behind the

them address the question of meaning in their own artistic activity, lib-

Pantheon in Paris, when she was eight months pregnant with her and

erating them from the centuries-old principles of the illusionistic repre-

Modigliani's second child. One day later Modigliani was buried at the

sentation of nature. Picasso initially was inspired by prehistoric Iberian

sculpture, before turning to African tribal art, encouraged by Matisse.

tion; instead, it depicts him as a leading avant-garde artist, laboring to

Stimulated by non-European sculpture, Derain began to work in stone in

overcome traditional academic norms through Primitivism.

March 1906; he was followed in this in 1907 by Constantin Brancusi, then

I am profoundly grateful to the numerous lenders, public museums

in 1909 by Modigliani, who drew inspiration from archaic Greek, Egyptian,

as well as private collectors, who have backed our exhibition with great

African, and East Asian art. Each of these artists sought and admired in

interest, have encouraged us in these difficult times, and now for the du-

these different ancient cultures the simplifying of forms, their abstraction

ration of our exhibition have generously handed over their important

and stylization. While from 1909 on Picasso dedicated himself to the evo-

works.

lution of Cubism, Modigliani remained loyal to Primitivism until his early death in January 1920. The visitor to the exhibition can trace the development of the oeuvre of this poignant outsider and artistic lone wolf through more than eighty

My immeasurable gratitude goes again to the exhibition's curator, Marc Restellini. Without his expert advice on the design of the exhibition concept and his indispensable contacts with numerous private lenders, the exhibition would not have been possible in thismanner.

of his works: from the early sculptural work to the "Cubist" portraits of his

My special thanks go to the authors Juliette Pozzo, head of the col-

friends at the Ecole de Parisand of Parisian society-ranging from maid

lection and curator of Pablo Picasso's personal collection at the Musee

to art collector-to the Madonna-like, anonymous female portraits al-

National Picasso in Paris, and professor Dr. Friedrich Teja Bach, editor of

luding to the Italian Gothic and Renaissance, the erotic nudes surrounded

the catalogue raisonne of Constantin Brancusi published in 1987. Despite

by scandal, and the "classicist" late works created during his exile in Nice.

difficult circumstances during the pandemic, they contributed first-rate

Modigliani's oeuvre is contrasted with works by Picasso, Brancusi, and De-

essays on Modigliani's relationships with Picasso and with Brancusi re-

rain, as well as with some examples of non-European and archaic art that

spectively.

the artist could admire in the Paris museums at the time. The influences

At the Albertina the exhibition has been managed by assistant cu-

of art from the most varied world cultures can be identified in Modigliani's

rator Gunhild Bauer. My deepest thanks go to her. Kristin Jedlicka from

oeuvre, art that as a young artist freshly arrived in the art metropolis of

exhibition management deserves many thanks for her professional han-

Paris he was able to study in the Louvre and in the ethnographic museum

dling of the loans and the installation of the exhibition, as do the many

at the Trocadero and whose formal reduction to the essential made such

workers behind the scenes in the departments of conservation, press,

an impact on him. The exhibition thus corrects the conception of the

graphics, and art education. I would particularly like to thank the architect

painter Modigliani as a popular yet moderate artist, committed to the

Martin Kohlbauer, who developed avery unusual and convincing design

ideal of beauty of Italian painting, marked by alcohol and drug consump-

for the complex contextualization of Modigliani'sworks. Prof. Dr. Klaus Albrecht Schroder Director General, The Albertina Museum, Vienna

9

MODIGLIANI. PICASSO The Primitivist Revolution The Centenary of an Avant-Garde Artist

Marc Restellini

reliable, they have been embellished with anecdotes of doubtful accuracy. On the other hand, "apocryphal" sources, often fanciful or romanticized, have brought further grist to the mill of the artist's "legend."1 It is true that the man remains amystery. His writings-his letters in particular-reveal his erudition and profound thinking, while including

Feted by the public at large, the works of Modigliani today figure promi-

ideas that are sometimes incomprehensible. The predominant image is

nently in prestigious collections and in flagship museums worldwide. He

of a man "resurrected;' whose "total dedication [was] to the supreme vo-

remains one of the most sought-after artists on the market, despite ever-

cation that drives him compulsively to paint:'2

more dizzying prices at auction. Although still viewed condescendingly

There is no doubt that Modigliani'swritings can appear surprising,

in academic circles-notably because of the myth of the artiste maudit,

and they clash with asuperficial understanding of the artist, which, based

the artist as cursed and alienated-Modigliani is today hailed as amajor

on photographs, envision him as a mix of distinction and charm, as de-

master. Gathering together an impressive number of his paintings, this

scribed by Lunia Czechowska 3 when they met:

exhibition marking the centenary of his death is held in one of the world's

"In June 1916, Zbo took me to an exhibition of Modigliani's work on

most renowned museums. For the past twenty years or so, there has

rue Huyghens. Coming out, we went to the terrace of the Rotonde with

been asteady stream of spectacular Modigliani retrospectives in institu-

some painter friends. I can still see, crossing the boulevard Montparnasse,

tions around the globe. Since the Paul Guillaume exhibition at the Or-

a very handsome boy wearing a black felt hat, velvet suit, and red scarf;

angerie in Paris in 1993, his work has more and more been put on display,

pencils stuck out of his pockets and he was carrying an enormous drawing

to international acclaim. Between 1993 and 1996, Noel Alexandre, son of

portfolio under his arm. It was Modigliani. He came and sat next to me. I

the collector Paul Alexandre, had his impressive collection of Modigliani

was struck by his distinction, his radiance and the beauty of his eyes. He

drawings exhibited internationally. In 2002, together with a notable aca-

was at once very simple and very noble. How different he was from the

demic committee, I myself organized asubstantial exhibition, Modigliani:

others in his smallest gestures, down to the way he shook your hand ....

L'ange au visage grave, at the Mu see du Luxembourg in Paris. This placed

He had superb hands, very assured in drawing:'4

the artist, who had not yet been counted among the great modernist

In 1924, concerned to leave afaithful testimony of her son'slife, Eu-

painters, on a par with Matisse and Picasso. Almost twenty years later,

genie Garsin, with the help of her daughter Margherita, sent Paul Alexan-

Picasso and Modigliani now share the limelight at the Albertina.

dre some "biographical notes"5 retracing the artist's childhood and ado-

Now that his work is widely appreciated, it is important to recall

lescence. These notes inform us that Amedeo Clemente Modigliani was

Modigliani'srole in the primitivist revolution that shook the foundations

born on July 12, 1884, as the fourth child and last son of Flaminio Modigliani

of modern art in the early twentieth century. With his caryatids and the

and Eugenie Garsin, a descendant of "two families [with] distinctive,

Greek, African, Khmer, and Oceanian influences in his painting, Modigliani

rather strong features, both Italian and Jewish:'6

must undoubtedly be seen as an artist of the avant-garde, and his oeuvre

"The Modiglianis had come from Rome to Livorno some fifty years

can be compared to those of Picasso, Derain, and Matisse. Recent studies

earlier, and were almost all tall, well built, with good posture, enjoying

have placed his relationship with his peers in anew light, and he now ap-

excellent health, unmarked by any hereditary defects, of phlegmatic tem-

pears more often as a source of inspiration than as a disciple or epigone.

peraments, more inclined to enjoy life than to strain their intellects,

Too often portrayed as a mere follower, Modigliani may well be one of

though they were sharp enough .... The Garsins, who originally came

the most accomplished of primitivist painters, one whose work under

from Livorno but had settled in Marseille for almost a hundred years,

this aegis lasted longer and advanced further than that of his contempo-

showed very different physical and intellectual traits: less tall and less

raries.

well-built, almost all with dark hair and very alert, expressive, changeable

But who was Modigliani? To answer this question today seems, at

faces. There had been afew cases of tuberculosis (and of lengthy resistance

first sight, simply impossible. On the one hand, though authentic sources

to the illness) among their ancestors, some liver disease and some psy-

from the artist's contemporaries-based on direct testimony-seem

chological disorders:'7 11

Ruined at about the same time and living ahand-to-mouth existence,

the hotel consider him as a grown man. A light curly growth of beard

the members of the two families shared ahouse. In an"austere atmosphere

added charm to his already expressive face. An English traveller said to

8

of work and self-denial;' Dedo-the nickname the family gave to the

him one day: 'You must paint with intuition, imagination and concentra-

youngest child-spent the first ten years of his life in a protected world,

tion:'lt's all on the programme,' Dedo replied.'I shall keep to it." 117

with little social interaction. Sensing that his health was delicate-he

The painter was undoubtedly just being courteous, as he already

endured several bouts of pleurisy in early childhood- his moth.er refused

had avery high opinion of what an artist and his art should be, as shown

to send him to primary school. "Docile, precociously intelligent, and pen-

by what he wrote to his friend Oscar Ghiglia in 1901:

sive;'9 the child whiled away his days among books, his mind nourished

"As for us, we have different rights from normal people, because

by the conversation of the adults among whom he lived. Learning poetry

we have different needs that place us above-this must be said and be-

(Dante in particular), he engaged in lengthy discussions with his grandfather,

lieved-their morality. Your duty is never to burn yourself up in sacrifice.

Isaac Garsin, "a man ... highly intelligent, and possessed of great integrity

Your true duty is to keep your dream alive .. .. The man who does not

0

and strong principles;,, who claimed to be a descendant of Spinoza and 11

"loved philosophical speculation:' From that point on, the child "would

individuals-destined to gain strength, to constantly demolish anything

scribble in pencil or with afew coloured crayons anything he could lay his

standing that is old or rotten-is not a man, he is a bourgeois, agrocer,

12

hands on:' "Then, when he was nearly eleven, he started attending the

whatever you like ... Acquire the habit of putting your demands as an

ginnasio [junior high school). He studied classics, though without much

artist above your duties towards men.',,8

enthusiasm, until 1898, when he moved on to the liceo [high school]:'13 At the age of fourteen Amedeo contracted typhoid fever: "For several weeks he hovered between life and death and he was

After Naples, Torre del Greco, and Capri, mother and son returned to Livorno for afew days, and then Modigliani left on his own, no longer

delirious for more than a month. It was during this delirium that Dedo

able to bear "the family routine, the complete absence of any artistic circle:,,9After a few months in Florence, he then left for Rome to spend

said he wanted to study painting. He had never spoken before of this

the winter there, later returning to Florence where he contracted scarlet

and probably believed it was an impossible dream .. .. Although for a

fever. When Uncle Amedeo, who supported him financially, died, the

fourteen year old, he already had a strong, determined personality... .

family"continued to do their best to satisfy Dedo'sdesire to leave Livorno

[H]is sensitive and proud nature also led him to conceal his most intimate

and live in an art metropolis:'20 After a stay in Venice, the artist decided

feelings. It was the long feverish delirium that finally allowed him to

to go to Paris.

speak out. He spoke continually of pictures seen in reproduction .. .. He

This was in 1906, when Modigliani was twenty-two. His portrait is

spoke of one of his nightmares: he missed the train that was supposed to

aglowing one: well-educated, strikingly handsome, aristocratic looking,

take him to Florence to visit the Uffizi Gallery.. .. [H]is mother, who was

uncommonly elegant, a young man exceptionally well up in literature

nursing him, decided she had to satisfy him whatever the cost. One day,

and philosophy. The ill health he had suffered only accentuated the im-

when he was still in the grip of fever and delirium, she clasped his hands

pression of his being exceptional and explains the fascination he was to

and tried to hold his attention. She made him this solemn promise:'When

exert first on his friends and then on his partner, Jeanne Hebuterne.

you are cured, I shall seek out a drawing master for you."'14

Let us turn to some eyewitnesses. First of all, Paul Alexandre, his

While convalescing, Modigliani attended the studio of the Livorno

earliest patron and also a friend.21 "The man was as attractive as his

painter Guglielmo Micheli, where he struck up a friendship with Oscar

works."22 "Although short, he was under five foot three inches, he was

Ghiglia. Lapsing into a bohemian lifestyle, he explored tobacco, women,

very handsome and had great success with women:'23 "He was a born

and above all spiritualism. Like two other students at the studio, who

aristocrat. He had the style and all the tastes:'24 Then Lunia Czechowska:

died shortly afterwards, he also contracted tuberculosis. By September

"Modigliani could only see what was beautiful and pure. I never saw him

1900, the doctors were saying that he too was condemned. This though was not the opinion of Eugenie Garsin: with financial assistance from her brother Amedee Garsin, whose business in Marseille was beginning to

experience jealousy for anyone: I never heard him make aspiteful remark:' "Modigliani had been very well brought up and this showed in spite of his disorderly life:'25 Paul Alexandre adds: "He was truly generous, with

prosper, she took her son away from Livorno. Mother and son set out for

no trace of envy or disparagement of his contemporaries, even though

awhole year,15 Dedo visiting museums and art galleries, Eugenie seeking

they themselves would not bother to look at his work."26

out atmospheric conditions that might cure him.16

12

know how to draw from his own energy new desires and almost new

But his friends also felt his strong personality and his highly exacting

The artist's personality was by now fixed :

ideas about his art. "A very gentle character, he could have extremely

"Already, his slightly haughty air, his rather cold manner, his ability

violent quarrels."27 "[O]f all the romanticized studies written about

to talk intelligently on a wide range of matters, made the few guests in

Modigliani, none has captured his soul or his true personality. I [Lunia

Czechowska] knew him as different from the image they give ... beneath

different from and even superior to other people-as betrayed by the

his bohemian exterior Modigliani concealed treasures only his friends

quotation from D'Annunzio that recurs inthe artist's production, and was

could see. He was a true artist: the common run cannot grasp or under-

even written on his drawings: "Life is a Gift: from the few to the many:

28

stand these beings apart whose soul is racked by torment:' For Paul

from Those who Know and possess to those who neither Know nor pos-

Alexandre: "Modigliani had ataste for danger. He thought that one should

sess."J6 Naturally, such a feeling of superiority could be explained by

not be afraid to risk one's life in order to expand it away. Utterly despising

Modigliani's early confrontation with illness and even death-the Reaper

29

mediocrity, he had pretentions to royal privilege:' "[H]e had an exclusive

had risen before him, but he escaped. This incomparable experience nec-

passion for his art. There was no question of turning aside even for a mo-

essarily left him with a vision of life that was completely different from

ment from his life's work to undertake what were in his eyes menial

that of other people-all those who had not shared it. This was then ex-

tasks:' "He already had a deep-rooted confidence in his own work. He

acerbated by his hypersensitivity as an artist and by the poetry he read.37

knew that he was an innovator rather than a follower:'Jo "Why couldn't

Avision was to haunt him for the rest of his life, as we see in the last mes-

Modigliani do as his friends did? The answer is simply that his view of

sage he wrote to Paul Alexandre on May 6, 1913:

art was too elevated, and nothing in the world would persuade him to

"Flatterer and friend.

1

prostitute it:'J

Happiness is an angel with aserious face. The resurrected:'J8

Modigliani thus exhibited an uncompromising elitism, preferring to "starve to death" than accept Jean Alexandre'soffer to draw for L'assiette

How should such lines be interpreted? The image of bliss materialized

au beurre, a satirical magazine that allowed talented draftsmen to earn

by asad angel- is it not the death from which he, the risen one, returned?

what was at the time a comfortable income. In the artist's eyes, no con-

Naturally, for someone "resurrected,"the encounter with the Beyond and

cession that might degrade his art could be tolerated. This tendency may

the world of death can only be asource of fascination. It lends anew per-

also explain the violent outbursts to which Modigliani was subject, ex-

spective to his writings-with their enigmatic annotations, their deeply

plosions that contributed to his reputation as a violent individual, due,

mysterious meaning or even total lack of any meaning, their mix of mys-

as legend had it, to alcohol and drugs. Lunia Czechowska argues that

ticism, metaphysics, Kabala, alchemy, and spiritualism.J9 He believed

these fits stemmed rather from the lack of understanding he felt in the

himself to be in the thrall of higher, external forces he could not control:

world around him, as illustrated by the following story. One day, in spite

"I myself am the plaything of very powerful energies that are born and

of the artist'sexpress prohibition, Leopold Zborowski, unable to overcome

die."40

his curiosity to see a girl who had come to pose naked, burst into

But Modigliani was aware above all that his art bears a message.

Modigliani'sstudio while he was painting Blonde Nude.The enraged artist

Perhaps he saw himself as ademi urge. Survage records Modigliani as de-

experienced this as a profound drama, as a"violation of ashrine."J2

claring, "We are building a new world using forms and colors, but it is

Modigliani's vision of art could be seen as political or social. In light of Modigliani's own words, as reported by Leopold Survage a decade later, this may indeed seem likely:

thought that is the lord of this new world." 41 The entire correspondence with Oscar Ghiglia seems to confirm this: "I am moreover trying to articulate as lucidly as possible the divers

"I am neither worker nor boss. The artist must be free, without

truths about art and life I have garnered from the beauties of Rome; and,

bonds. An exceptional life. The only normal life, it's the peasant, the

as the links between them surface in my mind, I will try to reveal them

farmer, who leads it ... neither boss nor worker, but master of his own

and to reconstitute their construction-I could almost say, their meta-

powers .. . we are one world, the bourgeoisie is another world-far from us."JJ

physical architecture-in an effort to create my truth about life, beauty and art:'42

The sociopolitical hypothesis, however, has not been proved.

"I cannot keep a diary ... because I believe that the innermost

Modigliani seems never to have been receptive to such questions. It is

events of the soul cannot be translated while we remain in their thrall.

even on recordJ4 that the artist did not share the political views of his

Why write when you're feeling? Believe me, only the work at its fullest

brother, Emmanuel, an adept of the Socialist movements current in Italy

stage of gestation, which has taken shape and freed itself from the

in 1898 who was sentenced to six months in prison by a military court.

shackles of all the contingent incidents that helped fecundate and produce

This conception of art, as well as a certain elitism that Modigliani

it, only this work is worth expressing and translating through style ....

propounded to his friend Ghiglia as early as 1901, thus stemmed from a

Every great work of art ought to be viewed like any other work of nature.

personal philosophy founded firstly on the artist'sfeeling of superiority

Firstly, in its aesthetic reality; then from outside, in its development and

as a man, and secondly on the value of his art and the role this should

in the mysteries of its creation, in what motivated and moved its creator.

play in artistic creation.J5 There is no doubt that he was a man who felt

This though is pure dogmatism:'4J 13

The Museum at the Trocadero: ACatalyst?

Fig.11 The Pala is du Trocadero, Paris, before1914

While these thoughts were surely intended to be clear to his friend

"Housed in apalace built for aquite different purpose, dark and unheated,

Ghiglia, the uninformed reader may find it difficult to follow and take

fitted with improvised showcases inadequately protected against dust,

refuge behind the reassuring notion that all this is just artists' chatter.

humidity and insects, with no handling rooms, no workrooms, no store-

But the poetic and philosophical form of Modigliani's words-a form he

rooms, no laboratories, no collection files, the Museum felt more like a

handles with undeniable brio-as well as his phraseology foster amore

'junk shop' in which valuable objects piled up in unlit cupboards stood

44

unremarked by visitors. Labeling was virtually non-existent. Geographical

So this is how he finally appears: a"metaphysical-spiritual" intel-

maps showing object distribution, essential for visitors to understand

lectual, prey to mystical tendencies. It has to be said: this is afar cry from

the artifacts' origins, were non-existent. More importantly, perishable

the traditional image of the painter, which has been rehashed for almost

objects (made of wood, wool, cotton, feathers, etc.) were exposed to de-

a hundred years. Behind the legend of the only artiste maudit of the

struction. Asore lack of warders made security impossible or at least illu-

twentieth century, there stands a visionary artist, possessed-like Pi-

sory. There was no protection against fire or theft.The library, with neither

casso-of aphilosophical conception of art that was extremely advanced

librarian nor catalogue, was, despite its riches, practically unusable."45

poetic and more persuasive reading of these emotionally charged letters.

and innovative. Two visionaries, then, confronted by a similar shock: received in an extraordinary museum of ethnography.

Such is the depressing sketch of the Mu see d'Ethnographiedu Trocadero made by Georges-Henri Riviere and Paul Rivet after they visited it in 1928, the year Rivet took over as its head. In light of such adescription,

14

is"museum" even the right word?What was museum-like in these rooms

and an absence of signage, a visit to the Musee d'Ethnographie du Tro-

in the Palais du Trocadero (fig.1) at that time? Both collections and pres-

cadero at the beginning of the twentieth century was closer to an exotic

entation seemed outdated. The dimly lit display cases offered the im-

expedition or a disturbing experience than an agreeable stroll among

pression of aheap of war trophies, the weapons fanning out, the panoplies

display cases containing exhibits. The state of the museum at that time

and other artifacts arranged so as to presentthe"savagery" of the peoples

needs to be taken into account when analyzing the influence of primitivism

who had made them. The whole enterprise was accompanied by implicit

on those artists who visited it. Picasso's account is symptomatic. In 1907, he stumbled upon the

colonial propaganda that asserted the superiority of the modern Western 46

world over uncivilized populations from elsewhere.

Thus, there was no avoiding the fact that the Musee d'Ethnographie du Trocadero more resembled a"dark cave;' a"shambles;' or even a"dusty

museum "by chance;' as he says-although it seems to have been at Derain'sinstigation-experiencing fascination, fear, and repugnance all at once:

47

mausoleum" than the hallowed ethnographic museum dreamed of in

"When I went to the Trocadero, it was disgusting. A flea market.

1878 by its founder, the anthropologist Ernest Hamy. By the turn of the

The stench. I was all alone. I wanted to get out. I didn't leave. I stayed. I

century, its shortcomings in terms of museography were glaring, and

understood it was really important: surely something was happening to

into the 1930s visitors could gaze at collections languishing in a phantas-

me.... I understood why I was apainter. All alone in this dreadful museum,

magorical, near mystical atmosphere. The scarce photographs of the mu-

with masks, redskin dolls, dusty mannequins."48

seum from that time confirm the reports offered by the occasional visitors. Piled high in serried ranks of display cases (fig. 2), masks, weapons,

Later, one of his partners, Fran~oise Gilot, recorded another version:

totems, and figurines are arranged in large, spectacular compositions

"I wanted to get out fast, but I stayed and studied. Men had made

(figs. 3, 4), or else enthroned in the center of the rooms to catch the eye

these masks and other objects for asacred purpose, a magicpurpose, as

of the aficionado (fig. 5). In accordance with the museographic norms of

akind of mediation between themselves and the unknown hostile forces

the era, the storerooms occupied only a negligible part of the museum's total space, the principle being to display almost every object and series for study, subjecting them to some preconceived scientific classification. With unsatisfactory lighting, pungent woods and fabrics, echoing halls,

Fig. 21 The Americas department at the Musee d'Ethnographie du Trocadero, Paris, ca.1880-89

15

Fig. 3J Thepresentationof objects fromOceaniain the Museed'Ethnograph ie du Trocadero, Paris, ea. 1895

Together with the Khmer works discovered on the site of Angkor, the museum displayed above all large casts the explorer made at the temples during his missions in Indochina in the 1870s. The center of the

that surrounded them, in order to overcome their fear and horror by

gallery was occupied by an imposing cast some 15 meters tall of one of

giving it a form and an image. At that moment, I realized that this was

the multifaced towers from the Bayon temple at Angkor Thom (fig. 6).

what painting was all about. Painting is not an aesthetic operation; it'sa

Another major item was the striking balustrade from the Preah Khan

form of magic designed as a mediator between this strange, hostile uni-

temple representing the nine-headed serpent deity Naga carried forth

verse and us, a way of seizing power by giving form to our terrors as well as our desires.''49

by three gods with many arms (fig. 7). Already impressive enough, the original works 51 were embellished with casts that conveyed an impression

Though there is no such oral testimony for Modigliani, the impact mentions visits made by the artist and of the influences he seems to

Along with the Musee d'Ethnographie, where objects and models were composed to form a"picturesque"53 atmosphere, and the Musee ln-

have absorbed there. Modigliani, however, was more attracted by the

dochinois, where the casts played their part in canonizing its "eternal ru-

of the museum on his painting is on record. Several times Paul Alexandre

16

of East Asia as a land of long-lost civilizations.52

west wing of the Pala is du Trocadero, occupied by the Mu see lndochinois,

ins;'54 the Pala is du Trocadero became amajor focus of primitivist inspira-

inaugurated by the explorer Louis Delaporte in 1882. Paul Alexandre re-

tion. This role was all the more crucial in Paris since the displays in better

marks: "It was Modigliani who introduced me to African art, and not the

organized and financed ethnographic museums elsewhere in Europein Great Britain, Germany, Scandinavia, Russia, Italy, and Switzerland55-

reverse. He took me to the Trocadero Museum, where he was in fact more

were far less unsatisfactory. Derain's experience at the British Museum

fascinated by the Angkor exhibition in the west wing. For myself, I have

bears witness to this: the artist was much more impressed by the works

never owned an item of either Cambodian or African art and I am not a connoisseur.'' 50

and their abundance than by the oddness of the venue. In 1906, he wrote to Matisse:"(! have seen] piled up, seemingly at random, get this, Chinese,

the Negroes [sic] of New Guinea, New Zealand, Hawaii, the Congo, the Assyrians, the Egyptians, the Etruscans, Phidias, the Romans, the lndies:'56 The Paris museum betrayed above all how far France lagged behind its European and American counterparts in this respect. Whereas other European cities-both major and smaller ones-had already established ethnographic museums in the 1830s or 1840s, in Paris the museum did not open until 1878, on the occasion of a World's Fair, and then only thanks to Ernest Hamy's tireless efforts at convincing the government of the importance of such an institution. Its rooms, which were meant to appear modern and take their inspiration from the most educationally progressive institutions in the field-the fruit of the universalism to which nineteenth-century European museums aspired by preserving objects from foreign lands57-ultimately fell in with the norms of colonial policy and aclassification by continent. From the 1890s, the Musee d'Ethnographie du Trocadero seemed to have become frozen in time, unable to adapt to the new forms of museography characterizing other ethnographic museums in Europe. Its

Fig. 5IDesire Mathieu Quesnel, World Exposition - The Chief of the Kanaks at the Ethnographic Exhibition in the Palais du Trocadero, 1878 Woodcut, 34.5 x 25.4 cm, Musee Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris

inertia contrasted strikingly with the effervescence bubbling through the art world and museums generally. The Trocadero as an institution seemed left behind by the growing curiosity in the "remote arts"58 then instrumental in widening the remit of the museum-already sorely stretched by the extension of the field of art-thus ceding an ever-growing role to private galleries, which were busy overturning the barriers demarcating the artwork from the ethnographic object. By around 1905, when the primitivists began visiting it, the Trocadero seemed even more outdated. In the United States, students of the famous anthropologist Franz Boas, then curator of the American Museum of Natural History, were devising new ways of understanding "primitive" art. On the other side of the Atlantic, the trend was no longer to collect objects, viewed as an oldfashioned and degrading concept that confined the"primitives" and their works to an archaic stage of human development, in contrast with civilizations that, one might say, allowed the constitution of collections of "readily transportable objects:'59 Thus, by the dawn of the artistic revolution Fig. 41 Display case with masks from New Caledonia, Musee d'Ethnographie du Trocadero, Paris, ca.1880-1926

in modern painting, the museum in the Trocadero resembled atime capsule-a hodgepodge of mid-nineteenth-century bromides bathed in an 17

Fig. 6 I Plaster cast of atower of the Bayon Temple, Angkor Thom, Musee lndochinois du Trocadero, Paris, ca.1900 Fig. 71Frederick Moller, World Exposition - Exhibition Halls of the Trocadero. The Cambodian Giant and the Many-Headed Snake that M. Delaporte Brought Back, 1878 Woodcut, 35 x 25.4 cm, Musee Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris

therefore all the more important since its visitors were primarily enthusiasts and experts, passing travelers, and, above all, artists in search of inspiration. As Europeans and Americans felt themselves more open to "primitive" art, museums of ethnography were tasked with offering an initial, almost visual, or even sensual definition of this art. The highly specific museography of such institutions was based on various ways of exhibiting the "objects by uncivilized peoples." The pre-

ambience almost unimaginable today. Whereas, for half a century, the

historian Felix Regnault pictured such objects as reliable documents pro-

quantity of narratives of exploration and anthropology treatises had been

viding relevant information on the "mores and mentality of a people:'61

increasing steadily, as a social class primitivist artists tended to eschew

Amuseum of ethnography was thus characterized by the motivation to

what were costly publications containing complex, rarely reader-friendly

exhibit artifacts accorded a"documentary status that would offset the

analyses, virtually confined to the then exclusive world of the library.

absence of writing among primitive peoples," in accordance with the

Comments accompanying the occasional illustration of an object in the

theory that such objects are the material transcription of imperatives of

so-called "popular" press were invariably pejorative and condescending,

biology or custom. In other words, parallel to racist definitions of the

60

the productions of "primitives" being judged pitiful or scandalous. The

"primitive" as an individual inferior to the members of a modern society,

Trocadero therefore was the perfect place for artists of modest means to

museums such as the Trocadero instilled in artists searching for inspiration

encounter non-European art.

and aesthetic intensity the idea that ethnographic objects by"primitives"

The very existence of this institution in the capital would justify ex-

serve to transmit messages that compensate for their lack of writing. 62

amining the transformations sparked by the primitivist revolution from

Perhaps the definition of"Primitivism"-or one of them at least-might

the point of view of Parisian artists alone, contrary to the precepts of in-

have arisen from just this perception.

ternational art history, which tends to study European primitivism, especially French and German, as awhole. The influence of the Trocadero was 18

Primitivisms and the Primitivist Revolution

"primitivism" for the arts of Africa and Oceania, then defined by the adjective "tribal;'65 dates only from the 1920s or 1930s. The underlying principles of primitivism appeared in two main stages: Robert Goldwater's

Incontestably, due to the miscellaneous definitions, significations, and

1938 study Primitivism in Modern Painting, 66 the first book on the subject,

characteristics it has accumulated, a notion such as "Primitivism" can no

and William Rubin's exhibition "Primitivism" in 20th Century Art at the

longer be used in the singular today. It has even tended to disappear al-

Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1984 along with the critical writing

together: under the pretext of forestalling unfortunate innuendos and

it subsequently stirred up.

generalizations from another age, it is being replaced here and there by

In 1938, the art historian Robert Goldwater published a ground-

other, supposedly less debatable terms. The preference is now for words

breaking text for the historiography of primitivism that is still studied

63

such as"remote" or"other lands;' expressions like"a vision of" an external

today for its analysis of aesthetics and art. Goldwater's stance was, however,

community of individuals, diplomatically identified as "other" and preceded

purely formalist, and took no account of the historical, social, and cultural

by positive adjectives relating to their past, history, or culture.

issues embedded in any relationship to the "primitive:' For Goldwater,

For the term "Primitivism" is inseparable from the notion of the

primitivism is predicated on the quest for emotional expressivity: artists

"primitive"-a word that Western observers must not use anymore unless

embarked on a project to distil I purely optical qualities so as to create ab-

in scare quotes, freighted as it is with connotations, racism, and prejudice,

solute images, free of all reference to reality, and expressive of the intensity

referring to an "Other;'whose chief characteristics were, on the one hand,

of the (immediate) effect. 67 Simplification is achieved through techniques

intellectual, moral, and civilizational decadence, and, on the other, op-

imitative of nature and in dramatic themes focusing on the "fundamental

position to developed, modern Western normality. "Modern" art-the

passions of existence."68 Paring the subject down to its essentials meant

art of this very modernity-had had recourse to art forms seen as archaic,

confronting viewers with immediate presentation in ararefied space where

ancient, or traditional, or as breaking with the contemporary aestheticism.

only the"symbolic" quality of the figures subsists. Figures are amechanism

To refer to such objects, those coming from (an) "elsewhere;' people spoke of "primitive art" or, in France, of art negre. As the twentieth century pro-

for intensifying images and reducing to a minimum the psychic distance

gressed, the words chosen sought to expunge the social and cultural hi-

figure dominating the whole work, the eye is drawn to the fundamentals.69

erarchy implicit in such terms, though the point of view was always that

The advent of the primitivist style thus has links with the invention of

of the West: the "primitive arts" simply became the"primal arts" and then

new methods of simplifying images-hence the burst of interest in non-

"non-European art:'The more usual subdivisions today are by geographical

European art in the period 1903-6 and up to World War One.

between artwork and beholder. Presented with a single action, a single

region or period; thus we speak of the "arts of Africa, Oceania, Asia, and

For Goldwater, what was then called art negre reflected a current

the Americas;' or of"traditional African art" for pieces dating from before

of thought in this new strand of aesthetic research. His findings were

the twentieth century from sub-Saharan Africa.

based on Carl Einstein's 1915 book Negerplastik, generally accepted as the

The notion of"Primitivism" is employed today to refer to a range of

first study to draw the attention of Europeans to the arts of Africa. One of

influences-generally between the mid-nineteenth century and the

Einstein'smain ideas centered on the decipherment of space: the illusory

post-World War Two period-of these so-called "primitive" societies on

three-dimensionality of painting and sculpture creates a fiction that ob-

those so-called "modern:' One of the most important of these influences

scures the authentic emotional awareness of the work. Contrariwise,

occurred in the world of art; hence "Primitivism" has also appeared to de-

African sculpture embodies pure form, free from plastic illusion and al-

note an episode in art history. Primitivism is not, however, an artistic

lowing for the creation of a mental space where such a form appears.70

movement, nor a current of thought, nor a form of philosophy whose

Cubist painting no longer constructs a space for the viewer; it offers a

borders are difficult to draw, nor even a media characteristic of certain

multiplicity of points of view that give rise to anew construction of space

works of art. Primitivism is an influence, an imprint, an "aesthetic ap-

that Einstein christened the"logical consequence of plasticity:'n His most

proach,"64 benighted by a lack of any clear or precise definition. The defi-

telling example, the African mask, is not therefore-as was the usual in-

nitions it has amassed over the past decades in the literature justify its

terpretation of the time-an expression of indifference, impersonality,

systematic plural usage today.

or inhumanity, but on the contrary amodel of intensity, of"the elaboration

The appearance of the word "primitivism" as early as in the middle

of apurified structure" capable of generating "a state of frozen ecstasy:' 72

of the nineteenth century derives from the diffusion of the concept of Eu-

In this regard, one of Goldwater's conclusions is that the art of the

ropean "Primitives"-fourteenth- and fifteenth-century artists from

"primitives" deploys the mask, but not the portrait. Hence, the focus no

Flanders and Northern Italy in whom painters of the second half of the

longer has to be on the psychological characterization of a human sitter,

nineteenth century sought inspiration. The generalization of the term

but, on the contrary, they should be presented as impersonal, anonymous 19

Fig. 8IPablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, 1907 Oil on canvas, 180 x 230 cm Museum of Modern Art, New York, Bequest of Lillie P. Bliss

even, so as to become a figure or symbol. 73 Thus, this early definition of 74

20

museum held an exhibition entitled "Primitivism" in 20th Century Art:

primitivism construes it as "an attitude productive of art." Its study

Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern, and a catalog with the same title

entails an understanding of the transformations affecting vision in that

was published on the occasion. The impact of both was tremendous.

period and of how reference to other cultures served as a means of re-

Giving widespread currency to the words "primitivism" and "primitivist;'

vealing the limits of a society in upheaval. The African, Oceanian, and

the aim of this blockbuster was to furnish ahistorical approach to the en-

Amerindian arts thus served as catalysts for intrinsically modern aesthetic

counter between Western modern art and so-called "primitive" productions.

ideas, the link between these artifacts and the primitivist painters being

In the US, however, its chief consequence was to fuel a debate on the

solely metaphorical, with any sense that they were derivative or indulging

question of primitivism that spawned numerous rebuttals, notably James

in formal borrowing amounting to an error of judgment. In this context,

Clifford's The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography,

Modigliani's caryatids, Picasso's "magic"75 faces, and Brancusi's marble

Literature, and Art in 1988.

sculptures appear as the results of formal serendipity, aestheticrenewal,

From the outset, William Rubin was widely criticized for, firstly, the

and individual identity being liberated by the shock of the creator's con-

choice of the word "primitive" itself, the use of which requires at least an

frontation with non-European art.

awareness of what it conveys, that is, the domination of one society and

Here is where Goldwater's theses fall down: if his ideas on the in-

culture over another-or rather over several others;76 and secondly, the

tensification of the image and the simplification or generalization of form

methodological and theoretical preconceptions on which the exhibition

culminating in early abstraction still hold today, his remarks on the un-

was based. 77 Due to the curator's explicit, indeed brazen ethnocentrism,

derstanding of the non-European arts remain stuck in the late 1930s,

and in spite of the term "Primitivism" in its title, the show paid homage

marred by a Eurocentric definition of art, in which its "primitive" manifes-

solely to Western art influenced by the "primitive" arts, with no real ap-

tations are only considered as"art" once the West has appropriated them.

preciation of the African, Oceanian, and Indigenous American pieces on

Almost fifty years later, similar rebukes were articulated aboutthe approach

display. For Rubin, primitivism is the posture of reevaluating traditional

to primitivism proposed by William Rubin, curator at MoMA. In 1984, the

and archaic art forms to encourage the emergence of a more natura l

sensibility and to combat academism, and so it "refers, not to the tribal arts in themselves, but to the Western [artists'] interest in and reaction to them:178

Fig. 9I Henri Matisse, The Dance/, 1909 Oil oncanvas, 259.7 x 390 cm Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller in honor of Alfred H. Barr

The methodology the curator opted for was placed under scrutiny: modernism is presented as the search among "primitive" peoples for"prin-

art in the debate on primitivism. Since the passive posture presupposed

ciples" that transcend culture, politics, and history-"common denomi-

that creativity came from appropriation, the question was, in consequence,

nators," as they are called in the exhibition. Presented in a room of

irrelevant.81The "Primitivism" exhibition enshrined the radical distinction

"affinities;'itself highly contentious, these "common denominators"were

between discourses of aesthetics and anthropology-not only because

one of the scientific aberrations of the exhibition, as has been repeatedly

the art world tended to neglect the scientific study of "primitive" objects,

79

pointed out. The many accusations leveled at the exhibition coalesced

but also because anthropologists generally showed scant interest in the

round the seminal issue of cultural appropriation. If, for its curator, prim-

visual qualities of the objects they collected and studied.82

itivism is a Western art concept of reflection and creativity inspired by

Despite the slew of criticism it received even while it was on, the

the outward appearance or form of some "primitive" object-leaving

MoMA exhibition did take a fresh look at primitivism, complementing

aside its anthropological, social, cultural, and religious dimensions-

the definition proposed by Goldwater and offering much evidence of the

other art historians, such as Thomas McEvilley, consider that to amount

profound if allusive "affinity" that developed between the Primitive and

to nothing less than appropriation, fulfilling Western art's need to renew

the Modern. Rubin proved that Goldwater's metaphorical connection did

its aesthetics in line with the sensitivities of the time.

80

not go far enough and showed what the historical European avant-gardes

At the time, the question was all the more topical, since in 1983,

had lifted wholesale from non-European art-from African, Oceanian,

shortly before the opening of the Mo MA exhibition, Jean Clair, curator of

and Indigenous American art in particular. 83 Above all, the exhibition

the graphic art department at the Centre Pompidou, published an essay

opened up the thorny historiographical question of the "primitive" that

in which he denounced the systematically passive character of"primitive"

persists to this day. By the late 1980s it was clear that the reduction by 21

critics and dealers of the "primitive" arts to an art of influence had to be resisted and the annexation of primal art by Western art opposed. To mount, in the early 2020s, an exhibition centering on the idea of "Primitivism" to honor the centennial of Modigliani's death inevitably means leaving oneself open to all sorts of accusations-indeed to many of the same that dogged Rubin's MoMA show in the late 1980s: that of promoting "affinities" between diverse forms of extra-European art to the detriment of the distinctions studied and reaffirmed for the last thirty years; that of reigniting the European-centered vision of art history, that guardian of the definition of"the artS:'which only deigned to include objects by "primitives" in the notion of art in the early twentieth century thanks to the intermediary of "primitivist" influences; that of running roughshod over the most recent approaches (in the social and political history of art, in post-colonial studies, in the transnational history of art) by retelling the old story of the ebb and flow between countries, artists, schools, and periods-methodologies that today'sart historians are regularly called upon to jettison as research and interpretation advance. It is, however, difficult to imagine how an exhibition commemorating the centenary of an artist'sdeath could be mounted without placing the I

stress on that artist, and, in the case of Amedeo Modigliani, without adopting the facile solution of the headline-grabbing solo show. Perhaps his relationship to primitivism might offer a new way of viewing hisart.

Fig.10 I Amedeo Modigliani, Head in Profile, 1907 Oil on canvas, 35.5 x 29.5 cm, Private collection

The idea is not new: in 2002, I made a start by venturing to assert that Modigliani was an avant-garde painter on a par with many of his contemporaries, at a time when he was disdained by art historians and dis-

but, in their different ways, both came to the fore during this period of

paraged as a kitsch artist of marginal interest. Indeed, like Picasso with

diverse influences and affected one another's oeuvres. They were two

his figures in Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (fig. 8), Matisse with his dancers

artists who, by simplifying and intensifying their forms, participated in

(fig. 9), or Derain with his Bathers (cat. 60), Modigliani embarked on

"primitivism" as defined by Goldwater, and who, by borrowing directly

similar analytical research into the figure, preferably feminine and naked,

from non-European works, were also part of the "primitivism" promoted

84

the result being his Caryatids (cats. 21, 24).

by Rubin; and who, entranced by the ethnographical collections in the

Almost twenty years later, while studies on "Primitivism" and its

Trocadero, lived through a period of European colonial expansion and

offshoots have blossomed in France, Europe, and the United States,

witnessed the attendant influx of African, Oceanian, and Indigenous

Modigliani still has not been accepted as a major contributor to this

American artifacts. They were two artists, in short, with apassion for the

artistic turning point. As his "rediscovery" gathers pace-at a time mu-

"primitive;' because, paradoxically, their society both exalted and disdained

seums such as the LaM in Villeneuve d'Ascq and Tate Modern in London

the "primitive." 87 If "the primitive artist"is no longer an acceptable entity

are staging major retrospectives of his oeuvre and forgeries have never

because, in the singular, primitivism has lost all meaning, perhaps "prim-

been hunted down so vigorously-a centennial tribute should be treated

itivist revolution" might be used to describe the transformations, influences,

as an opportunity to reassert his image as aforward-looking painter.

and various "primitivisms" inflecting art in France and in Germany.

No better stratagem could be devised than to place him in direct contrast with Picasso-his contemporary, friend, colleague, and rivalwho was the epitome of an artist under"primitivist"influence, the "hero"85

Two Artists of the Avant-Garde

86

to whom the "modernist revolution" is sometimes solely attributed.

22

Both men, Modigliani and Picasso, paid heed to influences from

We have talked about the periods and sources of inspiration, the aesthetic

"elsewhere" and for a number of years, though their methods were at

theories followed by the primitivists, and the issues of borrowing and ap-

odds, they treated them in a very similar manner. Both have to be seen

propriation. It is now time to study the primitivist revolution in light of

in light of their primitivist contemporaries, Brancusi, Matisse, and Derain;

the transformations it brought about in the oeuvres of Modigliani, Picasso,

and some of their contemporaries. In order not to lapse back into presenting non-European art as passive in its relationship with European art on the question of primitivism, the emphasis must be placed on individual pieces of art in order to assert their unchallenged role as models or benchmarks. Rather than choosing awide range of objects and studying them cursorily, a limited quantity must be examined more thoroughly. In the same spirit, the extra-European artifacts should not be studied alongside their cultural peers in the forlorn hope of highlighting "affinities:' Finally, one must avoid studying "modern" pieces back-to-back with "primitive" pieces with the aim of showing which "modern" piece was directly inspired by which "primitive" artifact. Instead, the focus should be on one artwork's overarching visual qualities, corresponding to the general definitions of primitivism outlined above: discourse, simplification, intensity, borrowing, iconography. Struggling to free themselves from the shackles of Western classical art, modern artists started taking an interest in works from Africa, Southeast Asia, Oceania, the Americas, and even from European antiquity. How each artist treated these arts depended, however, on the individual, each primitivist being in their own manner unique. Sharing perhaps the same sources and influences, above all their lives were intertwined: able to see each other's paintings and sculptures, the ceaseless cultural and in-

Fig.12 IAndre Derain, Portrait of the Artist's Father, 1904-5 Oil on canvas, 28.5 x 23.7 cm, Musee des Beaux-Arts, Chartres

tellectual ferment that characterized this group of artists transpires in every piece, despite the variety of primitivist influences. One thing is certain: Modigliani is an avant-garde artist. Between

1906 and 1914, his artistic research clearly resembles that of his contemporaries:88 the parallels in Modigliani and his contemporaries, notably Picasso, as regards women, the theater, and the use of alcohol and narcotics, were extremely close. Atthat time, the aesthetic explorations of the avant-garde centered entirely on analytical research into the figure-the naked female, primarily. Frequent in the history of art over several centuries, the theme of the bathers reached its artistic zenith between the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century. First Renoir then Cezanne produced countless variations on the theme. The latter studied every conceivable analogy between woman and landscape, analyzing the interaction of form from every angle. Then Braque and Derain took up the theme of the bathers, the former in 1907, the latter from 1905 to 1909. The climax was attained with Picasso and Les Demoise/les d'Avignon, painted in Paris in 1907 and traditionally taken to herald the birth of Cubism. By ahistorical quirk, this canvas was painted shortly before Picasso's visit to the Trocadero's ethnographical collections, at atime when he claimed to know nothing about African art. 89 Whatever he might allege, Picasso was already influFig.11 IAndre Derain, Portrait ofV/aminck, 1905 Oil on canvas, 41 x 33 cm, Musee des Beaux-Arts, Chartres

enced by his contemporaries and by primitivist precursors such as Cezanne. After his wanders through the Trocadero, the inspiration in his paintings

23

yet familiar with the work of the Fauves. Thus, his artistic approach and research had led him to the same conclusions as those of his contemporaries, as further illustrated by the extraordinary portrait of Paul Alexandre's father, Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with Crucifix (fig. 13): the face displays the same expressive force as Derain's Portrait of the Artist's Father, as if the aesthetic characteristics of the two patriarchs were identical. Modigliani was also enthralled by the other great theme of the Paris avant-garde at that time: the theater. In the summer of 1906, while Picasso was pursuing his fascination with the stage in G6sol, a village in the hills of Catalonia,92 Modigliani and Paul Alexandre were going to the theater in Paris: "Modigliani loved the theatre, which presents life in a way that blends dream and reality. At the theatre it seemed to us that we were living through a waking dream. A whole series of his drawings was inspired by the theatre. Stage-lighting, with its intensity, its color, its strangely placed sources (at that time footlights were still in use) was so unnatural that to his trained eye it gave the impression of a dream. In the old 'Gaite-Rochechouart; because of mirrors placed on the side walls, spectators, in certain seats (which we always chose), saw the spirited and thrilling image of Miss Lawler, which was so often reproduced, multiplied into alegion of small Miss Lawlers. At other times the stage would Fig.13 I Amedeo Modigliani, Jean-BaptisteAlexandre with Crucifix, 1909 Oil on canvas, 92 x 75 cm, Musee des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

seem to be a brilliant rectangle at the end of a long, dark corridor with its four walls blazing with colourful humanity."93 In this intensely creative period, Modigliani produced dozens of

becomes more obvious and the spatial construction follows the principles set out by Goldwater. Highly cultivated, Modigliani was always searching, making dis-

But theater is also about masks. What is a mask? It isa face super-

coveries, learning, absorbing. Arriving in Paris in 1906, the artist started

imposed on another face: the first hides, or protects, the second- the

assimilating the work of Cezanne on show at Bernheim's and admired

real, invisible face. On the stage a mask obscures the actions of players

the carvings by Gauguin unveiled at the Salon d'Automne. He also showed

who appear in aform different from what they are in reality; it also con-

an interest in African, Oceanian, Khmer, Etruscan, archaic Greek, and

stitutes an art form in itself, as with commedia dell'arte and Japanese

Indian art, from which he derived "his ideal female figure": the caryatid.

theater. The mask in art can represent other symbols: in African tribal art,

90

Unlike Picasso, of whose Demoisel/es d'Avignon he must have heard talk,

it conceals the sorcerer during a ceremony (fig. 14); in Egyptian art, it

Modigliani pushed his study of and research into the"ideal female figure"

adorns the mummified real face of the Pharaoh or symbolizes one of

to the extreme-much further than other artists of his generation concerned with the theme. 91

their gods. For the artist- for Modigliani, for Picasso-the dual reference

Thus, even if Modigliani had little connection with the artists of the

The mask was thus a "structure, chosen by the wearer either to

Parisian avant-garde, his stylistic preoccupations run along parallel tracks,

cover his true face, or to foresta ll the incongruity and disintegration of

to the theater and to non-European art isheavy with significance.

as evidenced by the small Head in Profile he brought to rue du Delta in De-

his features, or to ward off some external power.. .. If Picasso returned

cember1907 and later dedicated to Paul Alexandre (fig.10): the treatment

to G6sol and to the primitive life there, it was also so as there to unearth

of the texture (the background particularly) is very close to certain Fauvist

some of its secrets."% As Picasso confirmed after seeing the masks in the

works by Derain, such as the Portrait of Vlaminck of 1905 (fig. 11) or even

Musee d'Ethnographie du Trocadero the following year:

the Portrait of the Artist's Father of 1904-5 (fig.12). And this portrait itself

"Masks, they're not sculptures like the others. Not at all, they were

recalls the treatment of the background in Modigliani's painting Woman's

magical things .. . were intercessors. I've known the word in French since

Head with Beauty Spot. Intriguingly, it iscertain that at the time the artist

that time. Against everything: against unknown, threatening spirits ... . I then understood why I was a painter:'97

executed these portraits, probably before his arrival in Paris, he was not 24

drawings, often of the same subject, in a quest for a"high degree of intensity"94 that would allow him to assertthat"Fulfillment is on its way."95

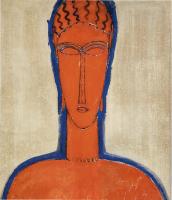

For Modigliani, this "theory of the mask" attains its acme in his caryatids. The caryatid is none other than a face, from the front or in profile, deliberately inexpressive and highly hieratic: it is a mask hiding the true nature of the individual. Modigliani's quest has only one purpose: to find the ideal sculptural figure-the one allowing the most profound human introspection by presenting anonymous and inexpressive faces. Two works exemplify this fact: The Red Bust against a black ground and the Large Red Bust (cat.1) of the former Netter collection. The undeniable power of these works, the intense presence of the subject in spite of the featurelessness of the figure, demonstrates a total mastery of the introspective research into the human soul at work in Modigliani's painting. Physically frail, Modigliani was unable to attain similar mastery in carving, since he soon found it beyond his strength, as Paul Alexandre described: "In these drawings there is invention, simplification and purification of the form. This is why African art appealed to him. Modigliani had reconstructed the lines of the human face in his own way by fitting them into primitive patterns. He enjoyed any attempt to simplify line and was interested in it for his personal development. .. . This search for simplification in drawing also delighted him in certain paintings by Douanier Rousseau or in Czobel's figures from fairground stalls. His major works of the pre-war period developed after a long period of gestation .... When a figure haunted his mind, he would draw feverishly with unbelievable speed, never retouching, starting the same drawing ten times in an evening by the light of acandle, until he obtained the contour he wanted in a sketch that satisfied him .... He sculpted in the same way. He drew for along time, then he attacked the block directly. If he made amistake,

Fig.14 I Mask, Fang, Gabon, before 1906, Painted wood, 42 x 28.5 x 14.7 cm Musee National d'Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris, Bequest of Mme Andre Derain, formerly in the collection of Andre Derain

he would take another block and start again. The labour of trimming to size bruised and exasperated him. His dream was to have an assistant to trim his blocks. He gave up sculpture because he found the physical effort

than the others to these kinds of sensations, was in bliss. As for Picasso,

of direct carving too great. In his whole life he sculpted just over twenty

seized by a nervous fit, he was shouting that he had discovered photog-

big figures. Almost all of them are in effect the same statue started over

raphy, that he may as well kill himself, that he had nothing left to learn:'102

and over again, as he tried to achieve the definitive form-which I

It was not until the tragic death of the German painter Karl-Heinz Wiegels

believe he never attained:'

98

that Picasso ceased these experiments:"after an eventful evening during

Finally there remained drink and drugs. There seems not much left

which he [Wiegels) had successively taken ether, hashish, and opium, he

to say about "Modigliani, the drug addict and alcoholic:' But even here

lost all sense of self, never coming to his senses, and in his lunacy, a few

the image of the artist has been distorted by the legend of the peintre

days later, hanged himself:'103

maudit. Who knows that Picasso took up smoking opium, introduced to

"Hashish sessions;' and even of other drugs, were thus common

it by acouple he bumped into in the Closerie des Lilas in 1905?99 According

practice at that time and one did not have to be an artiste maudit to

to Pierre Daix, although it is difficult to tell whether the paintings of this

indulge in them, as Paul Alexandre, who took credit for introducing

period bear the traces, the absentminded air of the Boy with aPipe seems

Modigliani to the effects of hashish, himself remarked:

100

to indicate that he is smoking something other than tobacco. Likewise, a drug formula appears in his Carnet Catalan.

101

"Asmall group of us also occasionally had 'hashish sessions;for ex-

Picasso's companion at

perimental and artistic purposes. Hashish produces extraordinary visions

the time, Fernande Olivier, recalls ahashish party one evening in autumn

and it'sfascinating for a painter. It was my friend Le Fauconnier who in-

1907:

troduced me to hashish. He organized the firs.t session in his studio in the "Apollinaire was howling madly with joy at being in the b[rothel]

rue Visconti with his friend Georges Bonamour, a stylish fellow who had

where he thought he was. In a corner, Max Jacob, better accustomed

first initiated him .... Le Fauconnier had painted arather interesting por-

25

everything beforehand, because the image he creates on paper or canvas appears prefigured on his retina. Most of the time, he simply records what he can already see. His nature is energized, excited to apeak by the drug; the images become sharper, clearer:'106 "Picasso'sart was visionary. He has the ability to see otherwise than with normal sight. Vision is, according to Webster's also: 'the act or power of perceiving mental images (as those formed by the imagination):"101 "Modigliani's art is revelatory, and, according to Webster, 'to reveal' means 'to unveil,' to 'discover:''108 Modigliani may then have discovered how, by the use of drugs and alcohol, he could attain an ideal state of "plenitude" and engage in introspection conducive to the creation of art. Contrary to legend, Modigliani was neither an alcoholic nor adrug addict.109 He did not create under the influence of narcotics or drink: like a"seer,'' he needed them to fathom the depths of the human soul, to penetrate the other and discover what lay hidden within himself:"Alcohol insulates us from the exterior, it helps us delve into our inner self, all while making use of the outside world:'110 "[1]t's the human being that interests me. Its face is the supreme creation of nature.

Fig. 15 I Amedeo Modigliani, Paul Alexandre, 1909 Oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm, Private collection