Japan: Architecture, Constructions, Ambiances 9783955531676

313 105 15MB

English Pages 184 [178] Year 2012

Japan – a Land of Contradictions?

Architecture and Aesthetic of an Island People

Japan’s Modern Architecture – from the Beginnings to the Present

Geographical Location of Projects

Projects

Botanical Museum near Kochi

Day-Care Centre for Children in Odate

House in Kobe

House in Sakurajosui

Furniture Store in Tokyo

House in Tokyo

House in Nagoya

House in Mineyama

House in Hadano

Weekend House in Karuizawa

House and Studio in Kobe

House and Studio in Tokyo

House near Yamanakako

House in Kyoto

Housing Development in Tokyo

House in Suzaku

House in Hokusetsu

Art House on Naoshima

Stone Museum in Nasu

Sunday School in Ibaraki

Gallery and Guest House in Temple Grounds in Kyoto

Mediatheque in Sendai

University in Saitama

Sports Stadium near Sendai

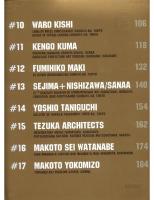

Architects

Authors

Illustration credits

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Christian Schittich (editor)

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

in ∂

Japan Architecture Constructions Ambiances

Christian Schittich (Ed.)

Birkhäuser Edition Detail

in ∂ Japan

in ∂

Japan Architecture, Constructions, Ambiances

Christian Schittich (Ed.)

Edition Detail – Institut für internationale Architektur-Dokumentation GmbH & Co. KG München Birkhäuser – Publishers for Architecture Basel · Boston · Berlin

Editor: Christian Schittich Co-Editor: Andrea Wiegelmann Editorial Services: Thomas Madlener Translation German/English: Ingrid Taylor (pp. 8–31), Robin Benson (pp. 32–55), Peter Green (pp. 56–169), Michael Robinson (pp. 170–175)

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress, Washington D.C., USA Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at . * 2002 Institut für internationale Architektur-Dokumentation GmbH, P.O. Box 33 06 60, D-80066 München und Birkhäuser – Publishers for Architecture, P.O. Box 133, CH-4010 Basel This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, re-use of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in other ways, and storage in data banks. For any kind of use, permission of the copyright owner must be obtained. Printed on acid-free paper produced from chlorine-free pulp (TCF •).

DTP: Peter Gensmantel, Andrea Linke, Cornelia Kohn, Roswitha Siegler Printed in Germany Reproduktion: Karl Dörfel Reproduktions-GmbH, München Druck und Bindung: Kösel GmbH & Co. KG, Kempten

ISBN 3-7643-6757-1 987654321

Contents

Japan – a Land of Contradictions? Christian Schittich Architecture and Aesthetic of an Island People Günter Nitschke

8

14

House near Yamanakako Shigeru Ban Architects, Tokyo

108

House in Kyoto Jun Tamaki/Tamaki Architectural Atelier, Kyoto

110

Housing Development in Tokyo Akira Watanabe Architect & Associates, Tokyo

114

118

Japan’s Modern Architecture – from the Beginnings to the Present Christian Schittich and Andrea Wiegelmann

32

Geographical Location of Projects

56

House in Suzaku Waro Kishi + K. Associates, Kyoto

Botanical Museum near Kochi Naito Architect & Associates, Tokyo

58

House in Hokusetsu Toshihito Yokouchi Architect and Associates, Kyoto 122

Day-Care Centre for Children in Odate Shigeru Ban Architects, Tokyo

62

Art House on Naoshima Tadao Ando Architect & Associates, Osaka

126

House in Kobe Toshiaki Kawai/Kawai Architects, Kyoto

66

Stone Museum in Nasu Kengo Kuma & Associates, Tokyo

130

House in Sakurajosui Toyo Ito & Associates, Tokyo

70

Sunday School in Ibaraki Tadao Ando Architect & Associates, Osaka

134

Furniture Store in Tokyo Kazuyo Sejima & Associates, Tokyo

74

Gallery and Guest House in Temple Grounds in Kyoto Takashi Yamaguchi & Associates, Osaka 142

House in Tokyo Kazuyo Sejima & Associates, Tokyo

78

Mediatheque in Sendai Toyo Ito & Associates, Tokyo

148

House in Nagoya Amorphe Takeyama & Associates, Kyoto

82

University in Saitama Riken Yamamoto & Field Shop, Yokohama

160

House in Mineyama FOBA, Kyoto

86

Sports Stadium near Sendai Atelier Hitoshi Abe, Sendai with Syouichi Haryu Architect and Associates, Sendai

166

Architects Authors Illustration credits

170 175 176

House in Hadano Tezuka Architects, Tokyo

90

Weekend House in Karuizawa Atelier Bow-Wow, Tokyo

94

House and Studio in Kobe Go Yoshimoto Architecture & Associates, Hyogo

98

House and Studio in Tokyo Naito Architect & Associates, Tokyo

104

Japan – a Land of Contradictions? Christian Schittich

Followers of contemporary architecture in Japan are fascinated by its uncompromising concepts. Nowhere else do we see innovative solutions so radically implemented, such tiny ground plans or uninhibited experimentation; and nowhere else are structures pared down so rigorously to the barest of essentials. Avantgarde architecture in this island nation is rich and diverse. It encompasses both Toyo Ito’s media architecture and the minimalist approach of Kazuyo Sejima, as well as the unconditional spatial and structural experiments of Shigeru Ban. Also under this umbrella is the sensory exploration of material as demonstrated by Kengo Kuma, and the quiet, meditative spaces of Tadao Ando. It was Tadao Ando, resolutely starting to tread his own path around 25 years ago, unswayed by the predominant fashions, who became the first Japanese architect to exercise a significant influence on architecture worldwide. In the last ten years contemporary Japanese architecture has enjoyed its highest ever international acclaim. Today a number of its practitioners are leading innovators in the world of architecture. Yet Japan’s architecture has always been slightly different to the international mainstream, as tradition is an ever-present component in this country. On the other hand Japan has traditionally demonstrated great openness to influences from outside. Just as in the past the Japanese adopted many aspects from the culture of China, often refining them in the process (Buddhism, for example, and temple-building techniques, the art of writing and the tea ceremony), and, after the Second World War, from the culture of Europe and America, in the shape of cameras, cars and electrical goods, so, too, they have also willingly accepted and assimilated architectural influences from outside. A land of contradictions? At first the Western observer in Japan is struck by contradictory impressions: aesthetically arranged food, a love of perfection in packaging and the tea ceremony on the one hand, set against the chaos of the cities, the teeming millions in the metropolises and the legendary discipline of the population. But deeper understanding does not come from judging the country, or its architecture, on the basis of our own criteria for evaluation: The entirely different circumstances and culture in Japan require a different approach, a different interpretation. Even though the outward appearance of Japanese architecture may look familiar, he who judges it with the standards of the

West is in danger of overvaluing the aesthetic aspects and thereby literally only scratching the surface. Specific values from Japanese culture still play a large part in its architecture, while principles familiar to us have little weight. This is true also of the dogmas of the modern movement and functionalism (even though, very early on, the modern movement had great influence on architecture in Japan) which in our part of the world are still a key criterion, albeit one that is increasingly called into question: In the Far East, by contrast, these dogmas have little validity as a theoretical guideline. Generally the Japanese take a very sceptical view of dogma. Even their religions – Shintoism and Buddhism – have a more practical orientation, and show great tolerance for other beliefs. Without an appreciation of traditional Japanese values, the Japanese relationship to simplicity and understanding of form, and how these differ from the West, there can be little real insight into today´s architecture in Japan. Again and again the key to understanding contemporary design lies in traditional values and attitudes. These explain a tendency towards contradiction and the love of all things natural or raw, and also the influence of the cyclical and the understanding of authenticity. The early tea masters, for example, with their teahouse and garden architecture, still have a strong influence on aesthetic sensibilities, and today we see all around evidence of an urge to break through the existing order, of a certain love of contradiction: straight paths in a garden are sure to have an arbitrary bend in them, and otherwise perfectly planned and built teahouses or farmhouses will have somewhere an unusually twisted beam, to break the illusion. Equally firmly anchored and now virtually proverbial is the influence of the cyclical on Japanese thought and action. The most striking example of this is perhaps the holy shrines of Ise, which since the seventh century have at regular intervals been dismantled and rebuilt in the same form, but using new wood (see pp 14 ff). In addition to illustrating constant change this example also reveals another inherent aspect (shared throughout almost all of Asia): The conceptual value of a building or an object is often more important than its historical value: the symbolic content of form and colour, and religious significance predominate over age and authentic material.

9

1.2

The town Perhaps the most visible evidence of the process of constant change that underlies Japanese culture is to be found in the cities. Here, nothing is permanent. Buildings that only yesterday were highly prized, may be gone by tomorrow. Even in the past the Japanese did not build their houses for eternity – wood, as a degradable building material, required constant renewal, and the destruction regularly caused by earthquakes, fire and typhoons imposed its own imperative for rebuilding. Today this constant change is fuelled by exorbitantly high prices for land in the inner cities, so high that the actual building costs become almost incidental, thus leading to a fast turnover in property. The urban vision in the European sense has no tradition in Japan and there are no largescale public buildings designed also as prominent urban markers. In the past the little wooden house has been the most common type of building. And still today in the greater urban district of Tokyo, almost half the 30 million or so inhabitants live in small detached houses, sometimes only half a metre apart. Living space in these houses is often less than 80 square metres. The entire Moloch consists of a juxtaposition of super-densely-built urban centres with busy traffic and transport systems, in the midst of a sea of small houses: Designing small houses is still one of the central tasks of Japanese architects (see pp 32ff). What strikes the observer most in Japanese conurbations, is the amazing proliferation of buildings of different shapes and sizes. It all looks like a gigantic confusion that shocks yet also fascinates. Everything is packed so densely and in such a haphazard way that it develops its own aesthetic charm. Particularly surprising is that this chaos has its own order – the Japanese city functions. Nowhere else in the world, for example, are trains so punctual as here, and nowhere else is there a more efficient public transport network (each day more than three million people pass through Tokyo´s busiest station, Shinjuku). Chaos, as a sophisticated system of order, is already well-founded in Far Eastern philosophy. This constant change and tremendous proliferation mean that architects hardly need take account of established structures. Concepts of urban integration, context and regional planning are little developed. As a consequence each individual building project is generally treated as a single, isolated intervention, not as something that relates to the wider urban fabric. The immediate environment is in any case constantly changing, it is too chaotic and too heterogeneous to respond to. A land of unlimited possibilities? The lack of formal restraints imposed by the urban context gives architects in Japan a great deal of scope. Designers are also less hampered by the kind of regulations and technical standards that apply in Germany, for example (although Japan does have strict controls on building stability, fire protection and spacing). Yet those travelling to Tokyo or Osaka to see first-hand the kind of avantgarde architecture published in the magazines, and encountering instead a bewildering mass of diverse structures, will soon deduct that freedom has its flip side: for every outstanding building by a top architect that is beautifully photographed and presented (sometimes too often) in

10

1.3

architectural magazines, there are thousands more that are at best mediocre. Given the number of buildings involved, only a very small percentage of highly committed architects really succeeds in exploiting this greater freedom. In addition to the greater design freedom architects enjoy, a relatively moderate climate and a more carefree approach to energy-consumption permit the use of more filigree constructions. Thermal insulation in roofs and facades, for example, is reduced to a minimum, and avoiding thermal bridges, a problem that so often complicates details for us in Central Europe, is not an issue. Single glazing for windows – with correspondingly thinner frames – is the rule, except in the northernmost parts of the country. Yet, single glazing and uninsulated reinforced concrete walls running from inside to outside do not necessarily mean that energy is wasted, because the Japanese accept a much wider fluctuation in temperature in their homes than people in the West. A temperature of less than 15°C in winter in the living room is not necessarily regarded as unacceptable. The Japanese respond instead, much more than we do, with their clothing, and, more than in the West, they respect the different conditions found in the different seasons. It´s quite common to find houses with no central heating but with air-conditioning systems installed on a room-by-room basis. Energy is used mostly in summer for refrigeration and air-conditioning systems. However, excessive reduction in detail (as published in the magazines) is not always acceptable, even in Japan. Some exponents of minimalism push things so far that signs of degradation begin to appear very soon after construction has been completed. The deep-rooted cycle of creation and degeneration then becomes a little too fast. Not always in Japan can one escape the impression that some buildings are designed solely with publication in mind, for that day when, brand sparkling new, they are presented to the photographers. This is understandable in the context of a country with a well-developed star cult, in a largely conforming and hierarchical society where fame signifies particularly high regard. Day-to-day work in a Japanese architectural office Building projects in Japan are handled mainly by the design departments of big building companies and architectural firms like Nikken Sekkei, some of which have over 1,000 employees. The smaller, independent architectural offices (whose projects are presented in this book) are only involved in a tiny percentage of the overall volume of building work. They are regarded to a certain extent as an exotic species, working at the forefront of design and developing new concepts. Financially things do not look good for this minority. During the 1980s, when the bubble economy was at its peak, ample funding was available for their projects. Public and private clients alike showed a surprisingly keen interest in architecture, and demand for unusual, sometimes even outlandish designs, was high. Great volumes of expensive building materials such as marble, granite and stainless steel were used, young unknown architects unexpectedly received major commissions and were able to give free rein to their imagination in the design. But when the enormous bubble burst, things rapidly returned to a more sober mood. Most of the young architects who trained during the boom years, are 11

1.4

1.5

today fighting for survival. Instead of building big arts centres and company headquarters, they are designing mini-houses. European architects visiting the offices of their professional colleagues in Japan are often surprised at how few people work there. Tadao Ando, who is increasingly involved in large-scale projects outside Japan, and within his country has built one museum after another, manages with just 25 employees. In Toyo Ito´s office it´s much the same. In most of the other practices whose projects are presented in this book, there are only about three to ten architects. One reason for this low number could be the working conditions: a working day that often finishes around midnight is quite common in the leading Japanese practices. One other reason, of course, is that the job of designing the construction details is generally simpler, and also that the final planning and detail work is only to a certain extent in the hands of the architect. Much is left to the construction firms and the skilled trades, and these people also play a responsible part in the planning process. They see it as their job to work with the architect on site to develop sensible solutions for construction details and they do not automatically respond to changes to the specification with excessive surcharges, but take pride instead in implementing any changes to as high a standard as they can. Of course in Japanese architectural practices as in other businesses in Japan, space is tight. It´s not uncommon to find four or five people having to share an office of just twelve square metres in size. To look at, these offices differ little from the ones in the West. Typical Japanese features are the exception. At Ando´s office, accommodated of course in a fair-faced concrete building he designed, there is the customary Japanese threshold where people take off their shoes and slip into the ubiquitous, one-size plastic slippers. But architectural offices in Japan show all the usual variations: chaotic and untidy, ones with rolls of plans spilling out of every corner, and sober CAD workplaces with little paper at all in sight. Toyo Ito´s light, clear rooms seem in many areas to resemble a model-building workshop, where, on our last visit, the final polish was being given to the pavilion for the Serpentine Gallery, using lots of design and detail models. The rough charm and temporary air of Kazuyo Sejima´s office in an old workshop building could just as easily have been found in a converted factory or warehouse in New York or Berlin. Learning from Japan? Thanks to the qualities mentioned at the beginning of this introduction, contemporary architecture in Japan is enjoying great international recognition. This island nation in the Pacific is fast becoming a place of pilgrimage for architects from all over the world. Like few other international journals, DETAIL has been regularly reporting on Japanese architecture for many years. This book is based on that treasure trove of experience and on the many meetings in Japan with leading architects. The focus in this book is on a wide spectrum of building types, and in choosing the selection the emphasis was firmly on variety. Our goal was to properly represent the tremendous breadth of quality architecture in Japan today, in terms of concept, material and construction. As already mentioned

12

Japanese architecture can be little understood without a knowledge of the nation´s culture and history, an area which Günther Nitschke illuminates in an introductory essay on the philosophical and aesthetic foundations of traditional Japanese architecture. A second essay goes on to examine more recent architectural history and current trends. A separate chapter is devoted to the small residential house, because of its continued importance and the many innovative ideas that are emerging in this area. One thing to remark about the detail drawings we publish here, is that they cannot simply be transferred to other cultures and climates. Nevertheless they still give valuable inspiration. In Central Europe in particular (where in many areas technical standards are all too regimented) the carefree and uncomplicated approach of architects in Japan gives food for thought. The same is true of the unconventional spatial concepts of Japanese architects and their ground plans designed for the smallest of spaces, the many different ways of handling intermediate spaces and the attention paid to transitions between outside and inside. Japanese architecture is often just a touch more simple, more uninhibited and more direct …

1.6

Illustrations: 1.1 House in Setagaya, Tokyo, Toyo Ito 1999 1.2 Aura House, Tokyo, FOBA 1996 1.3 Municipal Museum Yatsushiro, Toyo Ito 1994 1.4 Tadao Ando in his office in Osaka 1.5 Office of Fumihiko Maki in Tokio 1.6 Residential house near Tokyo, Shigeru Ban 2000

13

Architecture and Aesthetic of an Island People Günter Nitschke

miyabi, Courtly Elegance yugen, Mysterious Depth wabi, Rustic Simplicity sakui, Individual Creativity

The myth of the princess of the flowering trees and the princess of the eternal rock In the history of Japanese architecture it is a little-mentioned yet deep-rooted fact that up until the adoption of Western building methods in the nineteenth century, not a single building on the Japanese islands was made of stone.1 Even Japan’s countless mighty fortresses are all wooden constructions, except for the thick defensive walls upon which they rest. Why this is so has nothing to do with any inability of the Japanese to copy Chinese stone or brick buildings. Nor with the realisation that low-rise buildings in wood are more earthquake-resistant than similar ones in stone (as we now know). Only an island people, an isolated people, can focus so consistently over two thousand years on a single material, wood, for load-bearing constructions. This indicates a deep-seated preference on the part of the Japanese for the living and the transitory, for the change of the seasons, indeed for things in their raw sftate, as also seen in Japanese cuisine. Still today the traditional Japanese aesthetic is dominated by this preference. Even back in the days of the gods, as related by Japan’s most ancient myths, the first Japanese emperor on Earth, the grandson of the Sun Goddess, chose the beautiful princess of the flowering trees instead of her ugly twin sister, the princess of the eternal rock. Myths often reveal archetypes of the human psyche. And these archetypes are the architects of our human cultures. This attitude can even be seen in Japanese urban architecture. In contrast to the European ideal of a city as urbs aeterna, or eternal city, with its durable architecture and very rigid urban structure, Japanese cities of today still bear witness to a very different urban ideal, a place characterised by dynamic vitality, rapid change, the cyclical renewal of its components and a general tendency to ephemeral structures.2 Europe’s city squares, surrounded by the stone buildings of government or religious institutions, have their counterpart in Japan in chinju no mori, or groves for the deities, small areas of forest that are dedicated to local tutelary gods, and which change their appearance according to the seasons.3 The urban dreams and projects of the Japanese Metabolists of the early 1960s that seem so unusual to Western architects depict nothing new to Japanese eyes.4 To this day, history in Japan is not reckoned in accordance with the linear Christian calendar of the West. The Japanese people of 2002 are living in the year of Heisei 14, because fourteen years ago, the coronation of

the present emperor marked a renewal of space, time and people in Japan. This cyclical consciousness has a farreaching influence on the way people think of the past and also the present. Since the Meiji era, whenever a new emperor comes to the throne, a new nengo, literally name or motto for the year, is announced. Before that era, this happened several times within the reign of one emperor. Every torii or gateway to a Shinto shrine (fig. 2.1) reminds the Japanese of renewal, both in nature and in his society. In terms of architecture, this cyclical thinking and a love of living building material is shown perhaps best in the imperial ancestral shrines in the woods of Ise. These shrines resolve the paradox confronting sacred buildings, in that they must look both ancient and new at the same time. The 115 shrines in the Ise system, most probably created in the seventh century, are dismantled and rebuilt every twenty years (originally every 21 years), and their treasures and the pebbles upon which they rest are replaced.5 This custom was introduced at about the time people discontinued the religious taboo of abandoning the old capital city with the advent of each new emperor, and rebuilding the shrine in another place. Ise architecture reflects the spatial and structural organisation of the imperial court during the Nara era, a system which is known otherwise only from archaeological excavations and hypothetical reconstructions (fig. 2.3, 2.4, 2.25).

2.2

15

Fudo: Climate and culture – a holistic understanding In contrast to Ancient China, which had a long line of successive dynasties, Japan has had only one imperial house, tracing its origins back to the Sun Goddess. For a deeper understanding of Japanese religiousness and the relationship of Japanese buildings to the natural surroundings, it is important to understand that the people of Japan saw themselves as living in a kind of ‘blood relationship’ with the gods, who embody natural energies, according to a theory of Tetsuro Watsuji (1889–1960). A distinction between man, god and nature, typical of the Jewish, Christian and Islamic traditions, was never propagated in Japan, not even by Buddhism. However, with the adoption of Western ways of thinking and the imitation of European architectural forms, from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, the Japanese lost this eco-religious consciousness of a unity with nature in the way they build their houses, the way they live and the way they think. Just as to this day Japan has had only one imperial line, it has also had only one method of construction, characterised by timber frames and the addition of rooms in the horizontal plane. Taking its cue from European style history, Japanese architectural history has for the last one hundred 2.3

16

years or so distinguished between three styles within this single method of construction and spatial organisation. Developments are divided into three stages, each one lasting around four hundred years: the Shinden style (8th–12th century), the Shoin style (12th–16th century) and the Sukiya style (16th–19th century). Up until the advent of modern architecture in the midnineteenth century, architecture in Japan was formed by ‘climate and culture’, to quote a theory by Watsuji in his book of the same name from the 1930s, putting forward the first holistic vision of human culture and climate.6 On Asia’s eastern seaboard, the Japanese live in the monsoon belt. According to Watsuji this climate has shaped their religion, their arts, their clothing and food, and also their architecture. The rainy monsoon climate which down the ages has provided the Japanese and other monsoon peoples with nourishment, is also the source of the Japanese tendency towards passive rather than revolutionary thought and action, he believes. In addition they are afflicted each year by earthquakes, typhoons and floods which regularly destroy all things made and built by man. This demonstration of the transitoriness of all existence has had a strong

influence on the Japanese, in both a practical and a philosophical way. Here, too, lies one of the roots of their understanding of cyclical change. Virtually the only thing which has lasting value is land, the plot on which a building stands. The characteristic features of traditional Japanese architecture that are evident in all phases of history are, briefly: • Floors that are raised one or two feet above the ground, enough to protect against ground moisture and give good air-circulation in this hot, damp climate, while remaining in contact with the earth. • Wide, overhanging pitched roofs made of reed, shingles or tiles above the main building; around the perimeter a veranda, mostly under a separate roof, for protection against the sun and rain, insulation and light-modulation. • Empty rooms, i.e. rooms with no free-standing chairs, tables, cupboards or carpets; the entire floor area, laid with compressed rice straw mats, is the ‘chair’, as it were. • A horizontal, additive arrangement of space, almost always without an upper storey or a cellar; rooms are divided by means of movable panels and temporary installations, not solid walls. Watsuji described the traditional Japanese sense of space in their homes as a ‘bringing together without distance’6, as all partitions can be either removed entirely or shifted aside. • Perfection in detail and in building type. In Japan, up until the introduction of the North American timber frame, there were virtually no wooden buildings with badly fitting connections. The culture of an island people is oriented inwards and not outwards. • A clear distinction between load-bearing and spacedividing elements in the construction, which facilitates replacement or renovation of areas and components within the building. This distinction also makes the structure easy to dismantle and reconstruct in another location (fig. 2.5, 2.6). • Multifunctional use of the built space – a consequence of the limited amount of building land available on the Japanese islands. SHINDEN: Feminine accent and feminine elegance in the classical period of Japanese architecture, 8th to 12th centuries In a well-observed caricature by a Japanese architect, the most important of the above-mentioned features are wittily summarised in a kind of ‘evolutionary history from the chair to the house’ (fig. 2.2). As shown in the sketch of stage one, there are many haniwa or grave goods of clay from the tumulus era from 250 to 552 A.D. depicting figures seated on high chairs or thrones. The second stage shows buildings on high pillars, known from the Yayoi era as rice stores or buildings of the ruling elite. The next stage shows the beginnings of shrine and temple building, as seen in the Ise shrine, for example, and the fourth stage is the fully developed form of a palace, but also of a domestic home. The building has symbolically taken over the role of the chair. A fifth stage, added by the author to the original caricature, shows modern living in Japan – a house that has completely lost its relation to the ‘climate’, and in most cases also its connection with ‘culture’, because of its closed exterior and solid interior walls. People live in an air-conditioned environment, in a ‘machine for living’. The chair has been intro-

2.4

17

duced from the West, and the rooms are filling up more and more with domestic items and furniture. Another speciality of early Japanese architecture is also expressed in this caricature – the division of a building into two parts: a moya, or mother building, and an attached hisashi, the ‘veranda rooms’. The oldest example of such a spatial arrangement comes from the Nara era; a reconstruction by Masaru Sekino can be seen in the palace of the ruler of Fujiwara, Toyonari (fig. 2.7). Developed structurally and spatially to its full extent, this principle can be seen in the sumptuous palaces of the Heian era, and, on a smaller scale, in urban homes and farmhouses. 2.5

2.6

Although smaller than its model, the first shishinden or ‘purple palace’ of the Japanese emperor in the eighth century was strongly influenced by the Chinese imperial palace, in both construction and name. This building became the prototype of a style of architecture that came to be known as the Shinden style, or ‘sleeping palace style’, typical of the buildings of the aristocracy during the Heian era. Although at this time column spacing did vary, excavations of the imperial palace in Heiankyo (later to become Kyoto) have revealed spans of three metres. Never again was secular and religious architecture in Japan to achieve such openness towards the outside, and such inner flexibility of space (fig. 2.8, 2.10). A key factor in the spatial impression of the imperial palace is the use of round columns and sliding, not fixed walls. Shitomido, or horizontally opening grid-like shutters on the south facade afford a unique, broad panoramic view of the whole south garden. The upper half of the shutters could be pivoted upwards and fixed under the eaves, and the lower half removed entirely – an effect that was never again to be repeated in Japanese architecture. On cold winter days, however, the panels remained in place, which virtually blacked out the whole hall. This was without doubt one of the reasons why later the sliding door and sliding window were invented. In the Heian era, interior layouts could be altered in many ways using partition walls, folding screens, fabric hangings, reed blinds and transparent or solid double doors, which were sometimes also painted. Narrative scroll paintings from the twelfth to fourteenth centuries give a very lively impression of these interiors. A number of recent exhibition concepts and projects by contemporary Japanese architects such as Toyo Ito have their roots here. The tatami, a 5 to 10 cm thick mat of compressed straw, was at this time still moved around as required. With its raised form it indicated social status and was not, as in later periods, merely a floor covering. The scroll paintings also give the impression of a predominantly ‘feminine’ orientation and elegance in society and the arts; the highest ‘priest’ in the Shinto liturgy at the imperial ancestral shrines in Ise, for example, was a woman. A distinct form of Japanese literature was developed in this period by women. Miyabi or ‘courtly or effeminate elegance’ is a description used then and now in Japanese for this aesthetic in the Heian era.

2.7

18

Architectural space in Shinden architecture can thus not be viewed in terms of the outside, with its imposing construc-

tion, but in relation to the inside, with its space-defining elements of decorated fabric and wall paintings of seasonal blossom. In other words it had a ‘feminine’ aspect. Contrasting with this is the rigorously ‘male’ interior in the medieval period, influenced strongly by the samurai and Zen priests. On the scroll paintings of the Heian era, men merge into the female surroundings in both gesture and clothing. The throne is no imposing, showy Chinese Dragon Seat, but a simple straw mat draped with airy fabric hangings (fig. 2.14). FUSUI: Sino-Japanese geomancy – an early design theory In terms of overall layout, Shinden architecture is additive in arrangement, and in almost all cases set out on a 120 ≈ 120 m plot, the size of a typical block in Kyoto. Covered and open corridors link the separate buildings. The aristocrats of the time imitated the building style used by the emperor. Just as in Chinese geomantic tradition the emperor as the ‘Son of Heaven’ lives in the north on Earth – like the North Star in the sky – and looks south towards his subjects, so, too, all Shinden palaces are oriented north-south. The way Japanese domestic architecture opens up to the south is therefore not only based on rational climatic reasons, but also has religious significance, in its reflection of the Chinese-Japanese view of the world. North and south determine the East Asian city both socially and architecturally. People in the south are at the lowest end of the social scale in a rigid class society. To the south of the actual ‘sleeping palace’ is a broad open space laid out with white pebbles. Adjoining this, on the south side, is a large garden. Together this was known in Japanese as niwa, the word nowadays used to mean ‘garden’ in general. And indeed this was the first Japanese garden with pond, island, rivers and hills that could be reconstructed from descriptions. However, no original examples have survived (fig. 2.12).

2.8

2.9

Sino-Japanese geomancy determined the placement and orientation, both physical and social, primarily of all built objects: graves, farms, palaces and capital cities.8 The ideal arrangement was like an armchair ‘shaped’ out of the surrounding mountains and hills: the west, east and north were protected against uprisings, and, gently sloping land to the south opened up to the warmth of the sun. Such a landscape configuration was also chosen for the capital city of Kyoto. In planning the layout of the imperial palace in the city, the ideal natural situation was created using buildings set out to form the outline of an armchair. As the social order dictated, the central imperial throne was the single focus of the rigorously symmetrical complex. However, not only palaces and cities were built in this first great wave of Chinese cultural influence in the Sui-Tang Dynasty, but also Buddhist temples, and finally also Shinto shrines (fig. 2.13). The armchair figure as a design principle was taken up, too, in the large temple complexes in Nara and the impressive Amida Buddha complexes in Kyoto that were to follow, with their gardens designed to represent ‘Pure Lands’ or paradise on Earth, in the Buddhist sense. Both complexes show the same symmetrical layout, with covered corridors surrounding a large courtyard to the south of the Buddha hall. This courtyard was used in the Nara era and afterwards for large-scale religious ceremonies, but in

2.10

19

the Amida temples in Kyoto it was laid out with extensive gardens featuring hills, ponds and islands. Architecturally and symbolically all religious buildings in Japan – as also in China and Korea – take their cue from the seat of the only secular world power in this era, the palace of the ‘Son of Heaven’ (fig. 2.11).

2.11

2.12

2.13

But this symmetrical and formal composition was soon to be broken up in Japan. The individual buildings in a Shinden-style complex were essentially large single rooms erected for a specific function. There was no spatial division by means of fixed walls, and suspended ceilings were only rarely found. The buildings were linked by covered corridors. Towards the end of the Heian era and at the beginning of the Kamakura era, this clear composition was replaced by a merging of buildings and their roofs into a continuous sequence of spaces. Corridors sometimes developed into separate rooms. Also lost was the principle of symmetry in design that had originally been copied from China (fig. 2.15). This break with symmetry cannot, however, be ascribed to the typical Japanese preference for the asymmetrical, as originally proposed by Toshiro Inaji.10 The original complex should be regarded as the basic form. Asymmetrical compositions developed over the course of time, as a result of external constraints, like for example when lack of space dictated that only one half of an ensemble could be built. Meditation and the sword: Feudalism as a form of state organisation and discipline as religion In 1185, to the south of Tokyo, an independent military government was founded in the city of Kamakura, which gave its name to the Kamakura era in Japanese history. The shogun ruled the country from this city, although Kyoto was to remain the official capital for several centuries more and the emperor remained at least as the ceremonial head of state. An era dominated by men was ushered in. These men were the shogun and the warrior class of the samurai, and also the priests. Linking these diverse classes was their shared emphasis on discipline: the samurai and their discipline of killing and loyalty to the feudal lords, the Zen priests and their discipline of meditation and obedience to their master. The Zen school is one of the schools of meditation in the Far East that is based on the Indian tradition of yoga. It is no coincidence that even in India the gods of yoga were male, and all famous practitioners of this way of meditation, like Buddha himself, came from the warrior class. By contrast, the gods of the Tantric path of devotion from India and Tibet were depicted either as female or as a couple. In the first phase of the introduction of Zen from China in the thirteenth century, the Japanese monks withdrew into their new monasteries on remote mountains, in order to escape the ‘temptations of the flesh’ and political influence. Yet as early as the fourteenth century, the first inner-city Zen temples were founded in Kyoto. The Daitokuji and Myoshinji temples, both belonging to the Rinzai sect, were built in the Muromachi era in accordance with Chinese models. In these large-scale complexes, which took up whole districts in the city of Kyoto, the hojoshoin of the various abbots were to become the new centres of culture.

20

The Kamakura and Muromachi eras experienced a second wave of influence from China. Karamono, meaning literally ‘Chinese things’, even became the word for ‘modern’. Delicate porcelain and tea-making utensils, incense burners, vases, pottery of all kinds and especially landscape paintings in ink became the most important art objects, proudly brought back by the Zen monks from their excursions to the realm of the Middle Kingdom. The SHOIN: Architecture for men, warriors and priests in the Japanese medieval period, 12th to 16th centuries With the country’s shift towards a medieval feudal society, its architecture also changed. Two forms emerged, both closely linked: the buke-shoin, or villas of the shogun and samurai and the hojo-shoin, the living quarters of the abbots in the large Zen temple complexes. Like the earlier Shinden palaces, both forms of shoin have a garden, albeit much smaller, on the south side. However, they have no centrallylocated focus like the imperial seat that determined all the symmetry in the complex.11 The spatial and social centre of a shoin building is the most important corner of the main room; this focus is always eccentrically located. The name ‘shoin’, originally a term used for small writing niches, was not used until the middle of the nineteenth century. The shogun and the samurai in this period did not consciously try to develop a new style of architecture. On the contrary – they imitated down to the last detail the ideal of the Shinden style of the Heian aristocracy, although on a more modest scale. The round columns of the Shinden palaces were gradually replaced by square ones, which

enabled better connection details with the sliding doors and windows that were gaining ground. The fold-up shutters, too, were only used where they could function as a status symbol in architecture for the aristocracy, on the main or south facade of the residence hall. This process of change from round to angular columns and from folding shutters to the now archetypical sliding doors and windows of Japanese architecture is seen best on the much quoted reconstruction of the villa of the Ashikaga shogun Yoshinori in the Muromachi district of Kyoto (fig. 2.15). KE and HARE: Spatial and social differentiation in Shoin architecture One important architectural development in the late Heian era was to subdivide the original single-space structure of the Shinden palace (fig. 2.16). This articulation was not undertaken in an arbitrary fashion, but linked to the construction; it also reflected the rigid social differentiation in the feudal society of the time. From then on the original single large space could be split north-south by a wall directly below the ridge line or it could be divided east-west, in three strips. It was not long before both options were combined. Although it cannot be proven, this subdivision of the large space was probably only made possible by the invention of the suspended ceiling. In the religious architecture of the time – the Buddhist temples – the large halls or Buddha halls started to be split into a front room for the believers, and a back room for the actual statues of Buddha, the ritual accessories and the decoration. Such a horizontal differentiation took place on the principle of the differentiation of all built space and social behaviour in ke and hare

2.14

21

(fig. 2.19). This Japanese principle corresponds roughly to the better known polarity of yin and yang. Although hare originally meant fine weather and ke bad weather, today hare, in the social context, means the public, or formal area, and ke the private, more informal area. For Japanese organisation of space this difference is shown clearly by a south-facing L-shaped building, laid out in Shinden style and with an entrance in the east. The whole eastern part of the complex was for public use, the west for the private sphere.12 The lower a man’s position in the social hierarchy, the closer he sat to the door on social occasions. Through placement and orientation the shoin reflected social position. In the Shinden and Shoin styles the whole building was a status symbol, from the imposing entrance gates to the tatami border. Ordinary people were forbidden under pain of death to imitate even the Shinden-style shutters on their own house. The hojo-shoin, the living quarters of the abbots of the great Zen temples in medieval Kyoto, were arranged around a line of enormous gates, Buddha halls and lecture halls used by all the monks. These quarters were very simply designed. The main hall of the Daisen-in temple (Great Hermits Temple) inside the Daitokuji complex of the Rinzai sect, for example, shows the aforementioned division of a large room into two north-south-oriented zones and three east-west strips. Also, unusually, the shoin is surrounded on all sides by a karesansui, a dry landscape garden. Temple and garden are said to have been erected around 1513 by the priest Kogaku Shuko (fig. 2.18). Some of the room-dividing sliding doors are decorated with ink paintings by Soami (d. 1525). Thus in the room itself, one is in the midst of two kinds of ‘nature’: the painted nature inside the room and the planned ‘nature’ outside. The middle room contained a statue of Buddha. This entirely new type of garden from the Kamakura and Muromachi eras is not a pleasure garden or a promenade garden with artificial lakes and mountains, suchas was a part of Heian palace architecture. It was designed to be contemplated from very specific rooms within the building, and thus was composed as an integral part of the architecture.

2.15

2.16

22

Two types of dry garden developed in connection with Shoin architecture in Zen temples. One was an abstract composition and the other a composition in miniature of a scene from nature. The garden of the Daisen-in is of the second type. It depicts a highly impressive sequence of scenes from natural landscapes and at the same time symbolises human life in the form of a dry ‘river’ of sand. Arising in the stormy peaks, it flows over deceptive waterfalls and through rapids into a quiet sea of sand, signifying the possibility of enlightenment and deepest insight. This drama begins in the north-eastern corner of the garden and ends in the southwest, under a Buddha tree. In stark contrast to the courtly décor and feminine elegance of Heian art and architecture, the gardens, rooms and paintings of Shoin architecture ushered in a new aesthetic ideal in Japan. Termed yugen, this ideal seeks out the beauty that is in the mysterious, the hidden and the profound. The arts no longer revolved around a naturalistic,

2.17

23

colourful representation of seasonal change and the annual feasts and ceremonies of a courtly society, but reflected instead the kind of sadness we feel when confronted with the realisation of the transience of all existence. Yohakuno-bi, an appreciation of the beauty of empty rooms, of barren spaces, is also a part of the aesthetic of this time. It can be sensed not only in the empty spaces in ink paintings and dry Zen gardens, but also in the quiet, calm style of dancing and in the peacefulness of the music of Noh theatre. Zeami, the father of today’s Noh theatre or senutokoro-omoshiroki, says it is ‘the places that are not there that are of special interest’. 2.18

The development of a modular arrangement of space and prefabricated construction The Muromachi era lasted from 1336 to 1573. It was a time of civil war, murder and devastation of the towns. In the middle of the fifteenth century Kyoto was also destroyed. And yet it was during this period that the foundation stone for modern Japanese culture was laid, as it was at this time that the architecture, garden style and many new arts that we today feel to be typically Japanese first emerged. These include the tea ceremony, Noh theatre and a separate academy of Japanese painting. In terms of architecture it was the karesansui or dry gardens of the Zen temples and the treatment of space in Shoin buildings. In the interiors, fully developed Shoin architecture at the end of the sixteenth century showed a range of new spatial and decorative qualities that had originally developed independently of each other. Typical of a classical Shoin room is the joza-no-ma, or literally ‘the room with the raised level’, such as the guest hall of the Kojoin Temple inside the larger Onjoji temple complex in Otsu (fig. 2.21). The individual elements of this room are: • Tsuke-shoin, a low wooden writing table, built into a niche with sliding windows and often projecting onto the veranda; amazingly this ‘study corner’ has lent its name, like a pars pro toto, to the whole of Muromachi architecture. • Tokonoma, a windowless niche, raised by one column’s width and often painted, in which a flower arrangement or scroll painting was displayed, the most important decoration in the whole room. Two elements contributed to the formation of this social and spiritual focus in the home: on the one hand the toko, a slightly raised floor as a status symbol, and the oshi-ita, a shelf on which to display valuable works of art. Still today, even in the simplest house, the seating arrangement in relation to the tokonoma is of utmost importance. • Chigaedana, a windowless niche with overlapping shelves and drawers, a place to display valuable books and artistic utensils belonging to the tea ceremony. • Chodaigamae, painted, opaque wooden doors that enabled the master of the house easy access to the shoin from a room that was otherwise kept secret. • Fusuma and shoji, sliding doors with unpainted or painted surfaces, and grid-like wooden doors covered with translucent Japanese paper are now common but they were developed first in the Muromachi and Momoyama eras (fig. 2.21, 2.22). Social status was highlighted by raising the tatami floor by around 15 cm. In many shoins there was not only a jodan, a room of highest status, and a gedan, a room of lowest

24

2.19

25

status, but also a chudan, a room of intermediate status (fig. 2.19, 2.22). Other height gradations do not occur in traditional Japanese architecture. It is these tatami, or compressed straw mats – nowadays synonymous with the floor itself – that since the Muromachi era have blended the entire room together into a single visually balanced unit, both in terms of modular arrangement and proportion. In this modular system – called kiwari-jutsu in Japanese, which means literally a system of dividing wood – there was never an attempt to impose a single construction system on all buildings. There were five types of construction, each clearly separate: gateways, Shinto shrines, Buddhist monastery complexes, pagodas and houses. In Japanese domestic architecture there has long been an attempt with the kiwari system to achieve aesthetic proportions for all parts of a building. Column spacings, prefabricated wooden components and the modular requirements of the tatami system all had to be carefully tuned to each other. The Japanese ken, or column spacing, changed not only with the continually changing Japanese system of measurement, but also with the search for standardised dimensions in timber which could facilitate prefabrication and connections. Finally a column spacing of 197 cm was agreed for the towns and 181 cm for the countryside. In the classic kiwari system, which we know from the shomei carpenters manuscript of 1608, the size of the column cross-section, too, was fixed – at one tenth of the column spacing, or ken. With this all other dimensions and proportions in a building could be scaled up or down accordingly. Of course, modifications to the size of tatamis also had a significant influence on the universal ken. The size of a tatami derived originally from the proportions of the human body, and not for any reasons determined by material. As it was not possible to find an ideal tatami size, two tatami modules were developed, to match the two column spacings: one for the town measuring 190 cm ≈ 95.4 cm, and one for the countryside measuring 181 cm ≈ 90.9 cm. The cross-section of wooden columns was also standardised. On entering a traditional Japanese house with tatami mats the untrained eye will hardly notice the tiny differences in modular construction. But the system does not call for perfection. It is based on handcraft work and not industrially prefabricated components of always identical dimensions. Tatamis that differed in size from the norm were made by hand, small boards then filled in the gaps in the flooring. Castles and teahouses: Golden splendour and rustic simplicity in the 16th century From the middle of the sixteenth century, the daimyo princes fought each other in a series of opposing alliances. Only around the turn of the century, in 1703, did a new central power emerge in Edo, today’s Tokyo, brought about by the princes Oda Nobunaga (1534–82) and Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536–98) under the shogun Tokugawa Leyasu (1542–1616). While marking the beginning of 250 years of peace, this dynasty also spanned a period of total isolation 26

for Japan from the outside world. Edo became the new political and cultural centre of Japan, with the emperor, now totally deprived of power, residing in Kyoto until the middle of the nineteenth century. This short transition period from 1573 to 1600, often referred to as a golden age, is called the Azuchi-Momoyama era, named after the most important castles of Nobunaga and Hideyoshi. The fortress castles of the daimyo took on the role in Japanese architecture that had previously been filled by the palaces of the nobility, the shogun villas and the priests quarters from the Heian to the Muromachi eras.

2.20

The joka-machi, or towns that sprung up around a castle, developed into new centres of creativity in secularised art and architecture, characterised by the rising class of wealthy traders, businessmen and craftsmen. Around 95 percent of Japanese towns today can trace their origins back to the castle-towns of this period. The power- and pomp-loving shoguns Nobunaga and Hideyoshi surrounded themselves with the best paintings of the period, significantly on gold-leaf backgrounds. They also showed a strong interest in nature, simplicity and asceticism. For both of them the tea master Sen-no-Rikyu (1522–91) was the highest cultural advisor. He was the founder of wabi-cha, the simple, natural tea ceremony, soan, the plain, grass-hut style teahouse, and roji, the associated ‘dewy path’ or tea garden.

2.21

2.22

Wabi is the highly individual Japanese aesthetic of simplicity, naturalness and reserve, expressed by Sen-no-Rikyu in a particular way of preparing and drinking tea, in the utensils used and in the teahouse and its garden. The essence of this wabi aesthetic is perhaps best captured in the master’s words: ‘Never forget that the Way of Tea is nothing more than boiling water, making tea and drinking tea’; and: ‘The tea ceremony conducted in the smallest of spaces serves primarily the practice of meditation and its goal is enlightenment.’ Better than all the leading Buddhist teachers of that time, Sen-no-Rikyu, a Zen layman, managed to redefine meditation, by instilling consciousness into the simplest of actions people carry out in their daily lives. For him no learned prayer or recitation of holy texts could bring forth such heightened human alertness. Herein lie the origins of Japanese integration of thought and action, and of the aesthetic of handcrafted objects (fig. 2.20). In Japan the garden has traditionally always been a part of the architecture, and the architecture a part of the garden. It is perhaps useful here to consider the relationship between the tea garden, a completely new prototype of the Japanese garden, and the teahouse, also a new type of building. Originally the tea garden was a functional, modest path that led to the tea arbour. It was set out neither as a walk through nature, nor for serious contemplation from a fixed viewing point within the building, such as was the case in the two previous examples of Japanese gardens from the Heian and Muromachi eras. The model for the roji is a lonely mountain path which leads us out of our day-to-day trials and tribulations and into the peace and seclusion of nature. 27

Although everything in the tea garden – gateways, stone lanterns, stepping stones, ponds and even the toilets – seems to have been designed and built with the greatest of care, there was in fact originally nothing particular to admire or discover. At least at the time of Senno-Rikyu, the garden was very natural. This changed, however, with his successors. The only design principle that was subsequently added to the tea garden was miegakuri, or the succession of ‘attractions’ alternately hidden or revealed to the eye. The tea garden cannot be taken in at one glance, but opens up, often in the tiniest of spaces, as a series of surprising miniature views and glimpses that can be experienced while stepping over the tobi-ishi, or selected stepping stones that direct movement through and views of the garden. These modest experiments with a new building and garden type and the mie-gakuri design technique were the precursor of the later promenade gardens of the daimyo princes and the shoguns. These park-like gardens with teahouses and pavilions were the largest ever seen in the history of Japan. Viewed from the outside the tea arbour of the Wabi Way of Tea seems like a humble hermit’s hut, but one nevertheless senses that everything in it has been carefully designed. Crawling through the official entrance, the nijiri-guchi, a small sliding door about 60 cm ≈ 60 cm in size, one enters a tiny space. Often this space is only two tatami mats in size, the materials used inside all being left in their natural state: wooden pillars, earth walls, bamboo ceiling and paper windows. There is no view of the garden. Attention is therefore focused on the host, the sound of the boiling water, the taste of the tea and on the people themselves.13 SUKIYA: The free plan – individual creativity in pre-modern Japan, 17th to 19th centuries Amazingly, it was this rustic grass hut with its modest tea garden and tea path that was to release Japanese architecture from the dictates of a formal tradition, giving it new freedom in design and utilisation. In the twentieth century, it was then to influence modern European architecture (fig. 2.24). Basically this new architecture, called sukiya-zukuri, meaning sophisticated or elegant building style, was to do away with overwrought ornamentation and usher in the free ground plan, bring light into the whole of the interior and penetrate the building with views of the surrounding garden scene. In stark contrast to the small, closed teahouse, where attention was directed entirely inwards, these new Sukiya buildings opened out towards the garden, and indeed are unthinkable without this aspect.12

2.23

28

But Sukiya architecture was also imbued with a new consciousness, described by Itoh Teiji in his monograph on Sukiya architecture.13 This new consciousness, or sakui, ‘individual intention in creativity’, thus no longer reflects the pursuit of a formal tradition which is monitored by a craftsmen’s guild. Just as personal style and expression of even the most insignificant action, such as the way in which a tea bowl is cleaned with a cloth, is now important, so the names of master builders are now linked with their buildings. Sen-no-Rikyu was honoured as a man

of great originality and creativity, as every aspect of his tea ceremony, garden design and teahouse architecture bore witness to sakui. It could even be said that the tea masters of the Momoyama era were the first individualists ever in Japanese arts. The highest goal in the way of tea was no longer the copying of old forms, but innovation. Teahouses and buildings in the Sukiya style were therefore never copied. However, this respect for individual creativity was to disappear again for about one hundred years, with the imitation of European building styles in the second half of the nineteenth century. At the end of the sixteenth century the Sukiya building style brought forth a new form of ensemble, composed of the formal shoin building, a modest rustic teahouse and the actual Sukiya building. This ensemble, together with the garden, came to be known as the Sukiya style. The design technique of mie-gakuri used initially in the tea garden was then also used effectively for linking the individual buildings of the new ensemble together. Charming vistas and complex visual interplays resulted. The Katsura Villa in Kyoto is probably the most mature example of Sukiya architecture. Its present diagonal form developed over a period of forty years, starting with a small ‘teahouse in a melon field’, and growing to include the Old Shoin (fig. 2.17; 1620) of Prince Toshihito, the later Middle Shoin (1641), Music Instrument Room and the New Shoin (both between 1640 and 1650) of Prince Noritada (fig. 2.24). The Japanese word for this style of

jagged diagonal layout is ganko-kei, which literally means goose-flight formation. This formation is actually only the last logical step in the development of a ground plan that had begun with the Shinden Palace of the Heian era and its perfectly symmetrical armchair figure without a single dominating central point, and developed through the medieval period with the Shoin style of the warrior class and the Zen priests towards an L-shaped or one-armed chair figure, with eccentric focus. From the sixteenth century onwards, this then emerged into an open, flexible, expandable and free ground plan, with an asymmetric and multifocal character. Looking at overall composition, the history of traditional Japanese architecture traces a development from an embracing of the garden to an interpenetration with it (fig. 2.23). The Sukiya style of building, released from any obligations of status or religious ornament, is the quintessence of the Japanese architectural preference mentioned at the beginning of this essay for the natural, the living and the raw. Now untreated wood is again being used for columns, floors, ceilings, sometimes even with the bark still on it, such as in teahouses. This new aesthetic seeks to reveal, through the hand of man, the natural beauty of the materials themselves, not to hide it through ornament. Lightness pervades all aspects of Sukiya architecture. In fact it’s difficult to use the word ‘style’ here. On reaching the end of a long development process and path of learning, playfulness is the only style, to paraphrase Paul Scheerbart.

2.24

29

Notes/Literature: 1. Nitschke, Günter, ‚ISHI – Der Stein im japanischen Garten, Material oder Lebendes Wesen‘, archithese 6, Zurich, Dec. 2000, pp. 20–25 2. Nitschke, Günter, ‚rockflower – Transience and Renewal in Japanese Form‘, Kyoto Journal, Kyoto, May 2002 3. Nitschke, Günter, ‚CHINJU NO MORI – Urbane Götterhaine (Urban Deity Groves)‘, Daidalos 15, Berlin 1997, pp. 70-9 4. Nitschke,Günter, ‚EKI – Im Bewusstsein des Wandels: Die japanischen Metabolisten‘, Bauwelt 18/19, Berlin 1964, pp. 499–515 5. Nitschke, Günter, First Fruits Twice Tasted – Renewal of Time, Space and Man in Japan‘, From Shinto to Ando, London 1993, pp. 8–31 6. Watsuji, Tetsuro, FUDO – Wind und Erde, Der Zusammenhang von Klima und Kultur, Darmstadt 1997, pp. 117-38 7. Nishia, K. and Hozumi, K., What is Japanese Architecture, Tokyo 1985 8. Nitschke, Günter, Japanische Gärten – Rechter Winkel und Natürliche Form, Cologne 1999, pp. 32–61 9. Inoue, Mitsuo, Space in Japanese Architecture, Tokyo 1985, pp. 66–87 10. Inaji, Toshiro, The Garden as Architecture, Tokyo 1998, pp. 1–60 11. Hashimoto, Fumio, Architecture in the Shoin Style – Japanese Feudal Residences, Tokyo 1981 12. Yoshida, T., Das japanische Wohnhaus, Berlin 1969 13. Teiji, Ito and Yukio Futagawa, The Elegant Japanese House – Traditional Sukiya Architecture, Tokyo 1978, pp. 44–84

Japanese eras EARLY PERIOD Asuka Era Nara Era Heian Era

552–710 710–794 794–1185

MEDIEVAL PERIOD Kamakura Era Muromachi Era Azuchi-Momoyama Era

1185–1392 1392–1773 1573–1600

PRE-MODERN PERIOD Edo Era

1600–1868

MODERN PERIOD Meiji Era Taisho Era Showa Era Heisei Era

1868–1912 1912–1926 1926–1988 since 1988

30

Illustrations: 2.1 Gateway to a Shinto shrine, with a ‘sacred rope’, Shiga prefecture. Photo: Keiko Uehara 2.2 Caricature on the development of traditional Japanese architecture. 2.3 Inner shrine of Ise. Old shrine next to New Shrine. Aerial photo from 1973 2.4 Ground plan and elevations of the mikeden, Hall of the daily food sacrifice within the compound of the Outer Shrine of Ise. After Toshio Fukuyama from 1940, from: G. Nitschke, From Shinto to Ando, 1993, p. 25 2.5 Perspective section of a typical single-storey house, from: Yoshida, T., Das Japanische Wohnhaus, Verlag Ernst Wasmuth, Berlin 1969, pp. 71, 131 2.6 Perspective ground plan of a typical single-storey house, from: Yoshida, T., Das Japanische Wohnhaus, Verlag Ernst Wasmuth, Berlin 1969, pp. 71, 131 2.7 Palace of the ruler of Fujiwara, Toyonari, from the mid-8th century. Reconstruction by Masaru Sekino 2.8 Hypothetical spatial organisatiaon in a Shinden-style palace, from: Yoshida, T., Das Japanische Wohnhaus, Berlin 1969, p. 26 2.9 Todaiji in Nara, erected in the Nara era. The present construction dates from the Edo era and its proportions are about one third smaller than the original. 2.10 Shishinden, as it looks today, with ceremonial courtyard. Last reconstruction in the Edo era 2.11 Sketch of a geomantically ideal location for anything built in a natural setting, of Kyoto and, on a smaller scale, of the imperial palace. 2.12 Oldest perspective reconstruction of a Shinden complex by an architectural historian from the late Edo era, 1842 2.13 Todaiji, the Great Buddha Temple in Nara in the 8th century, 18th-century woodcut. 2.14 ‘Feminine’ spatial quality in the Shinden style, from: kasuga gongen kenki e-maki, an illustrated scroll of 1309 about the wonders of the Kasuga Gongen, National Museum, Tokyo 2.15 Hypothetical subdivision of the Shinden residence of the Ashikaga shogun Yoshinori in Kyoto. Round columns in the front, formal area, angular ones in the rear, private zone 2.16 Social and spatial stratification in Shoin architecture 2.17 Old Shoin, view into the room with the irori fireplace 2.18 The Daisen-in as a shoin, surrounded by dry garden, 16th century. 2.19 Villa of the shogun on a rakuchu-rakugai, ‘Folding screen with representations of Kyoto inside and outside the city limits’ in the Uesugi version of 1574. Uesugi Museum of the City of Yonezawa 2.20 Japanese teahouse, three tatamis in size, with a 2/3 tatami area for the host: A: guest entrance, B: tokonoma niche, C: fireplace, D: host 2.21 Joza-no-ma of the guest hall in the Kojoin temple, Otsu 2.22 L-shaped raised area in the kyusui-tei, the far pavilion in the Shugakuin villa 2.23 Development of traditional Japanese architecture: from Shinden to Shoin and Sukiya styles 2.24 Katsura Imperial Villa, interior of the Shokintei teahouse 2.25 Inner Shrine at Ise, during reconstruction in 1993

2.25

31

Japan’s Modern Architecture – From the Beginnings to the Present Christian Schittich and Andrea Wiegelmann

Utopia and Obstinacy – Its Development up to the Present Modern Japan arose out of the continual interplay of Eastern and Western influences as the country increasingly opened itself to the West. At the end of the 19th century, the government of the Meiji dynasty (1868–1912) ended the empire’s total isolation, which had lasted roughly two centuries. As it did so, it created the conditions for the Japanese to study the cultural and political structures of Europe and Northern America. In order to accelerate the country’s economic and technical development, engineers and scientists – including building experts and architects – were brought in from abroad. Receiving government commissions, they erected public buildings and modernised the education and training of architects. At the same time, Japanese architects travelled abroad, some with the intention of working and studying at leading offices in Paris, Berlin and Vienna. A period of historicist construction ended when, between 1910 and 1920, a young generation of architects set about creating a contemporary Japanese style. During these years, modernist European currents – first German Expressionism, then the de Stijl movement, the Bauhaus, and Le Corbusier – became increasingly influential. Frank Lloyd Wright was a further source of inspiration. Wright travelled to Japan for the first time in 1905. In 1911 he was commissioned to design the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, which was completed in 1923. Even more influential on Japanese architecture than Wright (who incorporated ideas from traditional Japanese architecture into his own designs) was Antonin Raymond, Wright’s Czech collaborator on the Imperial Hotel. Raymond stayed in Japan for forty years and conceived a language of forms that combined traditional elements with modern principles of construction and technology and modern ways of living. He modelled his approach on Le Corbusier’s rationalist architecture. In 1933 Bruno Taut emigrated to Japan, where he spent three years closely studying traditional architecture. Taut saw in the formal and spatial concept of the Villa Katsura (see p. 29ff.) a great affinity with the architecture of the Modern Movement. In the many writings and papers he published in Japan, Taut propagated a modern style of architecture that drew on the Japanese tradition and never tired of drawing attention to the positive qualities of traditional modes of construction. Which said, he remained completely opposed to the mere copying of forms handed down from the past.

At the very same time, independently of Taut, and initially unnoticed by him, a number of Japanese architects also began to return to their own tradition. They drew on ideas dealing with both spatial composition and structure. Isoya Yoshida, for example, attempted to reform traditional construction and – like Antonin Raymond – to adapt his principles of spatial division and structure to changing social conditions and changing principles of construction. The interiors of his residential buildings are based on large areas, with apertures and recesses introduced to lend emphasis. He separated structure from function, thus responding to the potential offered by the new materials, namely: steel and concrete. The 1950s – The Origins of Modern Architecture The Second World War put an abrupt end to the development of an independent modern Japanese architecture. After 1945, under the overwhelming influence of the USA, the victorious power, it took Japanese architects some time to link up again with the process that had begun earlier. That this happened was due, above all, to Kunio Maekawa and Junzo Sakura (both of whom had worked with Le Corbusier); they succeeded in taking up the thread and combining traditional spatial concepts with modern architectural approaches. However, the outstanding architect of the time was Kenzo Tange, a former pupil of Maekawa’s. His Memorial Museum, the Hiroshima Peace Center (1956), is rightly seen as one of Japan’s first independent contributions to modern architecture (fig. 3.4). Here, Tange combines the formal language of his idol, Le Corbusier, with concepts borrowed from

3.2

33

3.3

3.4

3.5

34

modern architecture. This unpretentious and somewhat bleak building, which rests on slender reinforced-concrete pillars, was supposed to embody the duality between East and West. Tange’s life work culminated in sports halls for the Tokyo Olympics, held in 1964 (fig. 3.5). These halls were designed as expressive buildings in steel and concrete, and displayed a formal affinity with the architecture of Eero Saarinen, Pier Luigi Nervi and Jørn Utzon. This design put Japanese architecture on the international stage. Apart from designing countless individual buildings, mostly of rough fair-faced concrete, Tange increasingly devoted his attention to the problems facing the city. His answer to the uncontrolled expansion of the urban environment is revealed in his master plan for Tokyo (1960), which envisages a linear development extending down to the sea and building over a part of Tokyo bay. This concept brought him close to a group of young architects and designers who had come together at the time of the International Design Conference in Tokyo in 1961. They called themselves the Metabolists, and had a profound influence on the architectural scene during the following decade. The 1960s – Metabolism and Urban Utopias Metabolism (the term is borrowed from biology) arose as a protest movement. It sought to create alternatives to the increasing urbanisation (a result of the economic boom) of the coastal region around Osaka and Tokyo and to the country’s growing westernisation. In an age of great utopias and an unbroken faith in technology (man had just began to conquer space), the Metabolists responded to the aforementioned problems with futuristic models of the city and flexible structures that displayed a formal affinity with the contemporary ideas of Archigram in England and those developed by some of the members of Team 10. Systematic planning methods applied during the design and construction phases thematised aspects of an urban-planning and architectural programme that was based on prefabrication and sought to direct growth processes in a rapidly developing society. Three years before the group was founded, Kiyonori Kikutake had already demonstrated, in his own home in Tokyo (Sky House, 1958), the basic principle behind Metabolism: cyclical growth plus renewal. The one-storey house, which rests on four slender concrete slabs and is composed of a single room subdivided into sleeping, cooking and sanitary cells, seems to float above the ground. The cells can be replaced or moved as desired, and additional rooms added for children. Inspired by the model of the human organism, which produces cells when needed and subsequently allows them to die, the load-bearing structure for this building is filled with replaceable modules (fig. 3.3). Even though the group of Metabolists did not work out a uniform position with respect to form – the works of the tendency’s individual representatives differ in character – they nonetheless shared a vision of organic growth. Another common feature is that almost all of their designs have remained utopias, as revealed, for example, by Helix City (1961) by Kisho Kurokawa, who collaborated on Tange’s project to build over the Bay of Tokyo, and Arata Isozaki’s Cluster in the Sky of the same year (fig. 3.2). Hardly any large-scale projects were realised. One of the few projects the group completed was the Nagakin Capsule Tower in Tokyo (1972), by Kurokawa. In this building,140 standardised,

3.6

3.7