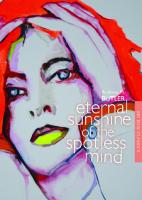

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind 9781838713645, 9781844578351

Imagine you learn that your lover has had you erased from their memory and, in a moment of despair, you have your lover

197 46 39MB

English Pages [101] Year 2014

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Andrew M Butler

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

For Jostein, solnyshko.

6

BFI FILM CLASSICS

Acknowledgments This book would not have been possible without the patience of the baristas, bartenders and barflies at various cafés, the New Inn and the Two Doves. My thanks also go out for help and distractions to Gemma Rowe, Ben Parkinson, Colin Odell, Debbie Moorhouse, Paul March-Russell, Rob McPherson, Tim Long, Mitch Le Blanc, James Kneale, Steve Kerry, Rowland Goodbody, Lisa Claire, Mark Bould, Caroline Bainbridge and executive editor Jostein Albrigtsen Aspelund.

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

Introduction There is a moment in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) when a character Mary Svevo (Kirsten Dunst) quotes the poem that gives the film its title: How happy is the blameless vestal’s lot! The world forgetting, by the world forgot. Eternal sunshine of the spotless mind! Each pray’r accepted, and each wish resign’d[.]1

Mary is an employee of Lacuna Inc, a company that specialises in erasing unwanted memories from its clients’ brains, and on several occasions she recites a quotation that could give the corporation a motto. She ascribes the poem, Eloisa to Abelard (1717), to Pope Alexander, forgetting for a second that it is in fact by Alexander Pope. But she has forgotten something else, as she makes a pass at her boss, Dr Mierzwiak (Tom Wilkinson): not only have the two of them already had an affair, but also her memory of this has been wiped. The germ of the script for Eternal Sunshine came from the French artist Pierre Bismuth. Bismuth was born in Paris in 1963 of North African heritage, and studied visual communication in Paris at École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs, where in part he was taught by tutors who had been radicals in the student-led rising of May 1968. In 1983, he began to study at the Hochschule der Kunst in Berlin, where he became influenced by the artist Joseph Beuys, known for his use of ready-mades and found objects in his work, as well as for performance art. Bismuth moved back to Paris to set up a studio and has lived in Brussels since the start of the 1990s, aside from a five-year spell from 2000 in London when his work was exhibited in the Lisson Gallery. His art attempts to engage with capitalism and the consumerist

7

8

BFI FILM CLASSICS

images produced by capitalism, for example the ‘Newspaper’ series (1991–2001) that reproduces front pages with a double version of their main photograph, ‘Collages for Men’ (2003) in which pornographic models are covered by cut-out white paper clothes and ‘Respect for the Dead – The Magnificent Seven’ (2003) that projects films such as Dirty Harry (1971), but stops them after the first character’s death. Bismuth asked director Michel Gondry what would happen if he were sent a card telling him that someone ‘“had you erased from her memory. Please don’t try to reach her.”’2 Gondry discussed this with screenwriter Charlie Kaufman and they decided to make a film about a relationship that had gone sour. They pitched the idea to a studio, as Being John Malkovich (1999) was in post-production and as Kaufman was commissioned to write what was to become Adaptation. (2002). Eternal Sunshine was thus delayed; in the meantime, Gondry directed Kaufman’s script of Human Nature (2001).3 What emerged was a complex and challenging narrative, musing upon the nature of memory and melancholia, part science fiction, part romantic comedy, and won Kaufman, Gondry and Mary has had the memory of her affair with Dr Howard Mierzwiak erased

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

Bismuth the Academy Award and BAFTA for Best Original Screenplay in 2005, as well as Movie of the Year for the AFI and the Saturn Award for Best Science-Fiction Film. Jim Carrey and Kate Winslet were also nominated for various acting prizes. The narrative of the film’s central characters, Joel Barish (Jim Carrey) and Clementine Kruczynski (Kate Winslet), is echoed by Mary and Mierzwiak’s failed romance. Mary does not know the context for her quotation, Eloisa to Abelard, a heroic verse epistle that drew on a 1713 translation of letters between Abelard, a philosopher and theologian who had an affair with his star pupil, Eloisa. When she becomes pregnant, they secretly marry and she enters a nunnery for safety; Abelard is attacked and castrated. Eloisa has become a bride of Christ while remaining in a loving relationship with a mortal man. She is in an impossible situation and will only be reunited with him after both their deaths. Donald B. Clark suggests that ‘death, the only solution to her conflict, is revealed by the imagery to be erotic satisfaction.’4 Kaufman had read and liked the lines – ‘I read her letters to Abelard. I find them rather exceptionally moving’5 – and had used this story for Craig Schwartz’s street puppet show in Being John Malkovich. Clementine’s first name offers an allusion to a death in its echo of ‘Oh My Darling, Clementine’, a parody of a folk song about the loss of a lover. In the words of the chorus: Oh my darling, oh my darling, Oh my darling, Clementine! Thou art gone and lost forever Dreadful sorry, Clementine!

Some of the details of the song suggest that it is ironic – her size nine shoes made from herring boxes, for example, as well as the ridiculousness of a splinter causing her to trip over and drown in a river – but there is a repetition of the fact of her death. The song inspired the title of John Ford’s Western My Darling Clementine

9

10

BFI FILM CLASSICS

(1946), which uses the music, and Huckleberry Hound’s off-key singing in the Hanna-Barbera cartoons from 1958 onwards. Joel claims not to know the character at the start of the movie, although he sings a couple of bars of it in his remembered/imagined childhood kitchen and then, when he is being bathed in the kitchen sink alongside her, his mother sings the tune too. ‘I’ve never seen you happier, Baby Joel’,6 Clementine tells him. In the scene when they first meet – towards the end of the film – Joel sings the song and says ‘My favorite thing when I was a kid was my Huckleberry Hound doll. I think your name is magical.’7 An instrumental version of the tune plays on the soundtrack as Joel listens to the tapes he recorded as part of the erasure process. The name, as Joel points out on their unwitting reunion at the start of the film, means ‘merciful’ – indeed ‘clemency’ – and forgiveness is significant in the context of death and mourning. While Eternal Sunshine is not about lovers parted by death, Clementine’s decision to have Joel erased from her life – and his subsequent decision to erase her from his – leaves them as if they Joel retreats to happy memories of being bathed in the kitchen sink as a child

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

are dead to each other. Joel, at least, whose reactions the film focuses on, is left mourning her, in a mood that borders on melancholia. Joel’s name means ‘YHWH is God’ and is shared with the second of the twelve minor Old Testament prophets, but it is also an allusion to the author Joel Townsley Rogers, whose The Red Right Hand (1945) is the novel that Clementine was reading at the start of film, although this is trimmed from the final version. Barish seems like a Freudian case study, especially in the confessional tapes he makes of his memories of Clementine. We learn of the experiences that led him to the decision to use Lacuna Inc. Because there is a kind of subjective duration of time in the film, much of the narrative is depicted in reverse order, heading back to Joel’s childhood – or at least memories of it. This is complicated by the opening scene in which Joel and Clementine appear to meet but are being reunited and the actions of Lacuna Inc that threaten to destroy Joel’s identity. The film thus also fits into the genre of the puzzle film, in which the audience is forced to work to untangle the narrative. This is not a standard-issue Hollywood narrative. My discussion of the film is divided into five sections, but the limits of print are such that a decision had to be made about the order in which these were placed. It would only be appropriate to read them in a different sequence. After an analysis of the personae the two main stars bring to Eternal Sunshine, I place the film in the ongoing intertwined careers of Kaufman and Gondry. The next three sections discuss genres: science fiction; romantic comedy; and the puzzle film. The makers of Eternal Sunshine have played with the ways in which the film fits and does not fit into a number of genres. The final chapter is more thematic, focusing upon the psychoanalytic aspects of the film, mourning and melancholia, before moving onto more recent accounts of trauma. The film draws upon and rejuvenates a number of genres. In an era of effects-heavy blockbusters that seem to be male power fantasies, it offers a version of science fiction that is grounded in psychologically complex characters with real human problems,

11

12

BFI FILM CLASSICS

encouraging reflection from the viewer rather than just astonishment at the visuals. It also allows the romantic comedy to move into new territory, although for the last century that subgenre has been tracking the ongoing shifts in the relations between the sexes and has not always been as fixated on happy endings as might be assumed. It marks stages in Gondry and Kaufman’s careers, as critically acclaimed film-makers who do not necessarily make hit films at the box office. While Time Out New York, Entertainment Weekly and The Onion all rated it in the top ten best movies of its decade, it grossed about $70 million worldwide on a budget of $20 million, making it a modest hit. Gondry has continued to make feature films, alongside documentaries, and Kaufman has sought more creative control, both by directing and then by financing his own films. Equally it is significant in the careers of Winslet and Carrey, especially in giving Carrey a chance to grow as an actor beyond the crowd-pleasing antics of his previous films.

Joel and Clementine’s first meeting is a reunion

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

1 Actors and Auteurs A film is clearly a collaboration between a large number of people – the lengthy end credits of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind going some way to demonstrate this. While film criticism has sometimes focused on the director when auteur-inflected – situating the film within Michel Gondry’s career – and a more literary approach would be to focus on the scriptwriter as the source of meaning – say, recurrent themes and style in the work of Charlie Kaufman – films are often sold on the strength of their actors. Although some films have posters saying ‘From the producer of –’ or ‘From the director of –’, and Kaufman was a sellable commodity on the back of Being John Malkovich (1999) and Adaptation. (2002), a star actor is a more common way of preselling a film. In casting Jim Carrey and Kate Winslet, Eternal Sunshine benefited from the publicity that the two stars generated. Each actor brings the baggage of his or her previous roles to a new project, a certain expectation on the part of the audience. Oddly, Carrey is largely cast against type here, which risked alienating the audience by failing to give them what they expect, and Winslet felt as if she was, but that underplays the agency that her earlier characters grasped in settings where opportunities for women were more limited. Before examining the careers of Kaufman and Gondry, I want to look at the baggage that the earlier work of Carrey and Winslet brought to their roles. Jim Carrey Canadian Jim Carrey stands in a tradition of film character comedian actors whose performances both sell and transcend specific films. As Philip Drake argues: ‘More than perhaps any other genre, pleasure in comedian comedy relies on our pleasure in watching the star performance.’8 Mixing verbal comedy with physical presence,

13

14

BFI FILM CLASSICS

they frequently acknowledge the audience, by breaking the fourth wall or with an extradiegetic look; in The Mask (1994), the masked Stanley Ipkiss (Carrey) looks at and speaks to the audience, declaring ‘it’s show time’ and very clearly performing and acknowledging that he is performing. According to Steve Seidman, the character comedian would already be familiar to that audience through work in other media – initially theatre, music hall, vaudeville and radio, but more recently television or stand-up – and thus on some level be a known quantity.9 The comedian actor is placed within a film in a number of semantic frames simultaneously: 1 as a fictional character within a given narrative and diegesis; 2 as celebrity and star familiar from news stories and interviews; 3 as recurring actor who has played other roles in other films (and in other narratives); and 4 as a physical body whose mannerisms we recognise.10 In Eternal Sunshine, Carrey ‘is’ Barish – or indeed a number of Barishes according to their position in the story, bitter, spotless or sadder and wiser.11 Carrey would be familiar to audiences from coverage of red carpets at premieres and award shows and his earlier star vehicles such as the Ace Ventura films (see below). Dave Kehr suggests that Carrey is ‘the first major American comic to grow up with television in his bloodstream’,12 noting the significance of the medium in many of his movies, from the alien being educated by TV in Earth Girls Are Easy (1989) to TV as womb in The Truman Show (1998). After struggling in stand-up comedy and gaining a few small roles in films such as The Dead Pool (1988), Carrey became part of the ensemble cast of Keenen Ivory Wayans and Damon Wayans’s sketch show In Living Color (1990–4). His debut leading feature role, Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (1994), establishes the Carrey persona as goofy outsider who never takes those in authority seriously. He pulls and twists his face, throws his body around (and ventriloquises his bottom) as well as speaking in

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

Liar Liar (1997): Carrey’s smile is part of his performance style

Carrey had to tone down his normal style for Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

The Truman Show (1998) was a more serious role

15

16

BFI FILM CLASSICS

exaggerated and nonsensical tones. He is always performing to an audience, real or imagined. When Lt Lois Einhorn (Sean Young) – eventually exposed as the villain – says, ‘Spare me your routine, Ventura’, it can become easy to empathise. In The Mask, special effects transform Carrey into a three-dimensional cartoon character as he dons a magical mask and causes chaos across a city. The sense that the masked version of the character is giving free vent to his desires is undercut by his hyperactivity when not masked. Although in Batman Forever (1995) Carrey had licence to overperform as The Riddler, he allowed ‘himself to be upstaged by Tommy Lee Jones’s more flamboyant performance’13 as Two-Face. As with the career of fellow character comedian Robin Williams, Carrey also took on more serious roles. In The Truman Show, there is a childlike element to his portrayal of Truman Burbank, unwitting reality show star at the centre of a stage set. By keeping his mannerisms in check, he enables the audience to empathise and it is this aspect of his persona that helps us care about Joel’s plight in Eternal Sunshine. In the Andy Kaufman biopic, Man on the Moon (1999), he transforms himself into the comedian, his excessive performance anchored within the earlier character comedian’s personae. Carrey must reel himself in for the more reflective scenes, especially in the later sequences. The Majestic (2001) is an uneasy homage to Capraesque patriotism set against the Hollywood blacklists; Peter Appleton (Carrey) is accused of communist sympathies and crashes his car on his way out of town. Suffering from amnesia, he ends up in a small town, mistaken for a missing war hero. Carrey’s performance makes his character likeable and has all his desires gratified even after his inadvertent deception is revealed. In these films, there is a tension between his star persona and the rather more buttoned-down character that he is required to represent. It is very much this depressive counter to the mania that Michel Gondry was to exploit in Eternal Sunshine. His relatively subdued performance seems all the more so in comparison to, say, Liar Liar (1997) where for much of the film Carrey stays at fever

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

pitch. The combination of gurning, his Jerry Lewis-like movements and his smile is ‘a key signifier in Carrey’s idiolect’.14 A part such as Joel might be in tension with his pre-existing star persona. As Henry Jenkins points out: Most film performances maintain some degree of distance between the star’s image and the film’s character, though certain types of film (comedy, musical) focus audience attention on that gap while others (social problem films, melodramas) efface it as much as possible.15

There is often a shift of gear between ‘acting’ and ‘performance’, the realism of the plot and the comic, knowing exaggeration of the carnivalesque star turn. In some cases, there is an attempt to naturalise and frame the performance – a split personality, possession, the gigs of Andy Kaufman within Man on the Moon (and the films within films of Gondry’s Be Kind Rewind offer a similar alibi for Jack Black), but Carrey’s Fletcher Reede in Liar Liar seems equally unhinged in the courtroom and outside it, under a spell and not. Pleasure derives from his comic performance. Kate Winslet British-born Kate Winslet had won a Best Supporting Actress BAFTA for her role as Marianne Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility (1995), but it was playing upper-class Rose DeWitt Bukater who falls in love with working-class Jack Dawson (Leonardo DiCaprio) in the blockbuster Titanic (1997) that made her an international star. Rose’s sexual awakening opens up the possibility of a life beyond marriage – although as Alexandra Keller notes, ‘Rose has led an adventurous but expensive life’.16 Keller argues that Rose is one in a line of ostensibly feminist protagonists in Cameron’s films: ‘Winslet’s high-spirited, loogey-hocking wannabe heiress (or, more to the point, don’twannabe heiress) is as independent, smart, idiosyncratically beautiful, sexy, powerful, (fill in another complimentary adjective here […]) as Cameron’s previous leading women.’17 For Keller, Rose

17

18

BFI FILM CLASSICS

Poster for Heavenly Creatures (1994)

Titanic (1997) made Winslet a household name

In Iris (2001), Winslet delivered a more liberated performance, but within an historical context

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

ends up reinforcing the values of patriarchy and the ruling class. Nevertheless, this ensured Winslet was a box-office draw, allowing her more freedom in her choice of roles as well as attracting audiences to Eternal Sunshine. Before Titanic, and after, as she returned to lower-budget films, she has tended to be in historical dramas: as Juliet Hulme in Heavenly Creatures (1994), based on the real-life Hulme–Parker murder of Parker’s (Melanie Lynskey) mother (Sarah Peirse); as a mother finding herself in 1970s Marrakech in Hideous Kinky (1998); in the aforementioned Austen adaptation Sense and Sensibility; as Hester Wallace in the World War II drama Enigma (2001) and as the young author Iris Murdoch in Iris (2001). Prior to Eternal Sunshine, her contemporary roles were rare – the exceptions being Holy Smoke (1998), in which she portrays a young Australian who is rescued from an Indian cult against her will by her family and The Life of David Gale (2003), as Bitsey Bloom, a tough journalist. Most of her roles have involved conflict between her character’s desires and the decorum of their era. In her film debut (Heavenly Creatures), her character has a tempestuous relationship with Pauline Parker, disapproved of by both their families, and the girls retreat into a fantasy world of their own imagining, Borovnia. The tone grows darker as their friendship is forbidden, culminating in the murder of Parker’s mother. The character is clearly capable, like Clementine, of asserting her own desires and protecting them when others condemn them – although this is Joel’s imagined version of Clementine rather than a direct depiction of the character. The same is true of Julia in Hideous Kinky, who takes her children away from their neglectful poet father in London to Marrakech, in search of her own enlightenment. The exotic open spaces and Moroccan people are very different from the barely lit interiors of a sinking ship in Titanic, although Julia does have recurrent nightmares of running down darkened alleyways and corridors in search of lost loved ones. As Ruth Barron, in Holy Smoke, and as Iris Murdoch, she is firmly in charge of her desires. Barron is forced to meet with P. J. Waters

19

20

BFI FILM CLASSICS

(Harvey Keitel), who has been employed to deprogramme her from the cult, but she is able to use her sexual allure to allow him to seduce her. As this is a film by Jane Campion, a feminist director, what risks being a male wish-fulfilment fantasy is instead about a woman assuming agency. Again, in Iris, it is her character who decides that she will start a physical relationship with John Bayley (Hugh Bonneville), along with others both male and female. The characters she has played have been far from passive, even in films set in eras when women were expected to be subservient to men. This pattern continues in Eternal Sunshine, when she is the one who chooses to start a relationship with Joel and refuses to be limited or defined by him. It is implied that she is unfaithful to him – although Joel accuses her in his testimony to Lacuna Inc of having sex simply to feel wanted because she is insecure. Her changing hair colour – especially the striking blue, orange, red and green – make her stand out and represent the antithesis of any feminine (and dated) modesty, and show she is in charge of her appearance. Just as Carrey’s characters’ extroversion often mask an inner insecurity, so Joel senses that her persona disguises the fact that she is ill at ease. With the film’s focus on Joel’s drama, we rarely get to see Clementine on her own rather than through Joel’s perceptions. She does decide to start a relationship with Patrick (Elijah Wood) and then decides to break it off, and she also decides when she is and is not in a relationship with Joel. Charlie Kaufman Kaufman was born in New York in 1958 and educated at West Hartford, Connecticut, Boston University and New York University. After a brief period working for a newspaper in Minneapolis, he moved to Los Angeles, contributing to comedy programmes such as Get a Life (1991–2), The Edge (1992–3), The Trouble with Larry (1993), Misery Loves Company (1995), The Dana Carvey Show (1996), Ned and Stacey (1996–7), as well as writing film scripts such as an unproduced adaptation of American science-fiction writer

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly (1977). Kaufman felt the existing adaptations ‘pilfer Dick’s ideas and the crudest part of his stories – the science-fiction stuff – and they throw away the gold, which is the quirkiness’.18 The different levels of reality, with ambiguity as to whether each of the imagined diegeses should be regarded as true – did this happen or was it a hallucination? – and the use of the author as a character can be traced in both Dick and Kaufman’s works. Dick’s protagonists, like Kaufman’s, are never heroic, usually slightly at odds with mainstream society and their wives or girlfriends are rarely sympathetic and frequently belittle them, with Dick’s male characters tending to turni to a feisty, younger female for solace. The protagonist also confronts an older, more successful patriarch, too ambivalent to be labelled an antagonist, similar to characters Kaufman imagined for his films. Kaufman has admitted that ‘Dick has certainly been very influential on my work […] I like the fact that his science fiction isn’t really science fiction at all.’19 In 1997, Kaufman was commissioned to adapt the memoir of television producer and self-alleged CIA assassin, Chuck Barris, Confessions of a Dangerous Mind (1984). This eventually became George Clooney’s directorial debut. Barris (Sam Rockwell) alternates Kaufman wrote an adaptation of A Scanner Darkly (2006). The film was eventually made by Richard Linklater, but from a different script

21

22

BFI FILM CLASSICS

between introverted and extroverted, with Clooney intercutting brief testimonies from real people who knew Barris with the rather tall tales of murder. Kaufman was reportedly unhappy with Clooney’s version, and decided to try to keep more creative control in future. The Kaufmanesque juxtaposition of reality and performance remains, however, with Barris haunted by studio sets that recall his childhood and his killings. Television clips are intercut with film narrative. Even in Clooney’s version it remains ‘obvious that he [Kaufman] has only one subject, the mind, and only one plot, how the mind negotiates with reality, fantasy, hallucination, desire and dreams’.20 While Kaufman – certainly if we believe his alter ego Charlie Kaufman in Adaptation. – is suspicious of genre, his ‘work and approach to filmmaking has been transformed into its own genre’.21 From his outsider, frustrated, protagonists, we gain the sense that ‘We are others to ourselves – separated, divided, alienated’.22 This is the case with puppeteer Craig Schwartz (John Cusack) in Being John Malkovich, whose puppetry gives him a grace in performance he does not have in real life. Working as a file clerk, he discovers a portal that gives access into the head of actor John

In Being John Malkovich (1999), the award-winning actor’s mind can be entered via a portal behind a filing cabinet

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

Malkovich. As Malkovich, he becomes attractive to co-worker Maxine (Catherine Keener), but she is also sexually excited by Craig’s wife Lotte (Cameron Diaz) as Malkovich. Malkovich becomes Craig’s ultimate puppet and Maxine his lover, but the achievement of his desires sours when she becomes pregnant. Jonze and Kaufman reunited for a second film, Adaptation., an apparent dramatisation of Kaufman’s struggles to write a screenplay of Susan Orlean’s bestseller, The Orchid Thief (1998). Kaufman inserts himself into the script alongside a (fictional) twin brother, Donald (both played by Nicolas Cage), who is killed during the course of the film. Charlie’s anxieties about avoiding formulae are balanced by Donald’s embrace of them, along with the dictates of script guru Robert McKee (Brian Cox). The film undercuts the kind of cliché that Kaufman despises. Each of these three films adapts the biographies of real people – Barris, Malkovich and other Hollywood stars, Orlean (Meryl Streep) and the eponymous thief (Chris Cooper) – and autobiography – Charlie Kaufman most obviously, but Schwartz and Barris as surrogates for him and Barris’s memoir. The real/nonreal uncannily blurs. Kaufman is himself a character in Adaptation. (2002)

23

24

BFI FILM CLASSICS

Meanwhile, Kaufman made the first of his two collaborations with Gondry. Human Nature is loosely inspired by a Franz Kafka short story, ‘A Report to an Academy’ (1917) in which a chimpanzee, Red Peter, talks about how he learned to imitate human beings and became a vaudeville entertainer. The film’s equivalent of Red Peter is Puff (Rhys Ifans) who had been raised as an ape and is trained by Nathan Bronfman (Tim Robbins), himself brought up by strict, behaviourist parents. Nathan romances Lila Jute (Patricia Arquette), who had run away to the woods because her body was covered in thick hair. The characters are subject to the influences of nurture and nature, fighting for free will and agency against both. In Eternal Sunshine, their second collaboration, Kaufman uses a number of intertexts – the Pope reference I have already discussed, but Clementine’s allusions to Margery Williams’s The Velveteen Rabbit (1922) and Rogers’s The Red Right Hand are cut from the finished film, although the latter is acknowledged in the closing credits. Rogers’s novel is a hallucinatory one, narrated by Dr Harry N. Riddle Jr who is not quite a witness to the disappearance and possible murder of oil millionaire S. Inis St Erme. The novel hints that Riddle is the murderer: ‘it didn’t mean that, just because I was a doctor, he [an expert in murderers] would find a murderer in me’.23 The word ‘lacuna’ appears on the second page of the novel – ‘was there something darker than a mental lacuna and a moment of sleepwalking on my part?’24 – and Riddle and St Erme’s fiancée are unknowingly near neighbours in New York, like Clementine and Joel. Theatre director Caden Cotard’s (Philip Seymour Hoffman) attempt to stage an epic play of his own life is central to Synecdoche, New York (2008), Kaufman’s directorial debut. Such a detailed attempt to represent the world echoes the life-size map in Lewis Carroll’s Sylvie and Bruno Concluded (1893) ‘“on the scale of a mile to the mile!”’,25 which has never been unfolded because it would cover the land, ‘“So we now use the country itself as its own map.” ’26 The film was a critical but not a financial success.

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

Meanwhile he has worked on a crowd-funded animated version of his pseudonymous Anomalisa (2005), written as Francis Fregoli for composer Carter Burwell’s Theatre of the Ear, with Duke Johnson and Kaufman directing. The intention is to be free of studio interference and have artistic freedom – although the bloated nature of Cotard’s everlasting performance may caution against this. Michel Gondry For four films Kaufman had worked with directors who, like David Fincher, Brett Ratner and McG before them, had cut their filmic teeth in music videos. Jonze had made videos for Sonic Youth, Teenage Fanclub, Beastie Boys, R.E.M. and Björk, among others; Gondry for Björk, Kylie Minogue, the White Stripes, the Chemical Brothers, Radiohead and more. Gondry was born in Versailles on 8 May 1963 and had made short films and played in a punk band with his brother, Oliver. Gondry formed a second band, Oui Oui, with school friend singer-guitarist Étienne Charry in 1983, and it is the films he made for this band that brought him to the attention of Icelandic Synecdoche, New York (2008): the author dramatises his own life

25

26

BFI FILM CLASSICS

singer-songwriter Björk; together they made ‘Human Behaviour’ (1993). The song was an attempt to empathise with the animal point of view of humans, with a stop-motion animation hedgehog and a person dressed up as a toy bear. Gondry blends live action, models, animation and back-screen projections to create a fairytale-like feel. Gondry’s meticulous results are often produced in camera rather than relying on computer trickery. Carol Vernalis notes that Eternal Sunshine ‘divides into segments that work like inset music videos, each organized by unique visual and aural principles’.27 A glance aesthetic means that we must note and interpret repeated images of alcohol, birds/flight, American flags, ice and so on, even when they may only be on screen for a couple of frames. Yet, in the age of the digital, Gondry appears resolutely analogue, and this aesthetic carries on into his films and documentaries such as Dave Chappelle’s Block Party (2005), L’Épine dans le Coeur (The Thorn in the Heart, 2009) and Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy? (2013). He also collaborated with artist Pierre Bismuth on The All-Seeing Eye (The Hardcore Techno Version) (2008), a film from a camera that rotates within an apartment, where the furnishings and other decorations disappear one by one, leaving an empty white cube. The film was shown in galleries and at the BFI Southbank with a rotating projector: The careful alignment of projected space and space of projection makes the two rooms appear almost spatially coextensive, encouraging viewers to feel that they have entered the set. [… It] is not immediately apparent that the set is a scaled-down model.28

Among the objects in the ‘room’ was a television set, showing a clip from Eternal Sunshine. Human Nature was Gondry’s feature debut, although he had rewritten a script for The Green Hornet in 1997. Gondry used similar techniques to those in his video productions, with some of the sequences in the woods echoing ‘Human Behaviour’ and the use of 8mm stock for flashback sequences. Roger Ebert notes the film’s

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

‘manic whimsy’,29 and the movie is playful – as well as thoughtful – risking self-indulgence. While Eternal Sunshine is hardly more streamlined in plot terms, the style shifts serve the narrative. Several of the chase/escape sequences for Joel and Clementine seem to echo the metamorphoses from Gondry’s ‘Smarienbad’ (1998) commercial for Smirnoff – a young couple are pursued in a surreal chase through a bar, a hotel bedroom, a boat, trains, in cars across a desert, a street and the same bar, each edit melding via a shot through the vodka bottle. La Science des Rêves (The Science of Sleep, 2006) was an original screenplay by Gondry, inspired by a story told to him by the then ten-year-old actor Sam Nessim. Returning to Paris after the death of his father, Stéphane Miroux (Gael García Bernal) falls in love with Stéphanie (Charlotte Gainsbourg). The realistic mise en scène is juxtaposed with worlds constructed from cardboard or cellophane, real experiences drifting into dream imagery. In Be Kind Rewind, a film written by Gondry that turns into a star vehicle for character comedian Jack Black, a video-rental store faces closure. Jerry (Black) accidentally erases the videos and so he and the clerk The Science of Sleep (2006) blurs fantasy and reality

27

28

BFI FILM CLASSICS

Matt (Mos Def, who had been in Block Party) recreate the Hollywood movies on camcorders with amateur actors. These ‘Sweded’ movies within the movie are the film’s highlights and an over-saccharine ending is avoided by a sense of ambiguity over the store’s future. Gondry then made ‘Interior Design’, a segment of the portmanteau film Tokyo! (with Leos Carax and Boon Joon Ho, 2008). Inspired by Gabrielle Wood’s graphic novel Cecil and Jordan in New York, Hiroko (Ayako Fujitani) and Akira (Ryô Kase) are a young couple trying to find an apartment in Tokyo. As Akira appears to be finding success with his sf films, Hiroko feels alienated and invisible, metamorphosing into a chair. There is a disjunction here between the sense of fulfilment she feels as something that is sat on and the extreme passivity this suggests. Akira’s sf film is glimpsed briefly, and should be taken less seriously than Matt and Jerry’s efforts in Be Kind Rewind. Gondry then embraced Hollywood with The Green Hornet (2011), a bromance superhero film co-written by and starring Seth Rogen. Despite attempts to subvert the genre, it is full of 3D effects,

Gondry, here on the set of Be Kind Rewind (2007), often adopts a lo-fi aesthetic

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

stunts and noise. Peter Bradshaw suspected ‘Gondry’s original conception, [was] weeded out and blandified by the studio’.30 It is very different from The We and the I (2012), largely set on a bus on the last day of school in the Bronx. The naturalistic conversations between teenagers – about their days, their pasts and their immediate and longterm futures, chatting each other up, falling out, sending text and video messages and so on – are intercut with flashbacks, mobile-phone footage and a cardboard model of the bus. The tragic ending risks seeming like the intrusion of too much reality into a rather more mundane scenario. His most recent film at the time of writing is L’Écume des jours (Mood Indigo, 2013), an adaptation of Boris Vian’s novel Froth on the Daydream (1947), co-written by Luc Bossi. The wealthy Colin (Roman Duris) meets Chloé (Audrey Tautou) at a party and they fall in love, but after they marry, Chloé falls seriously ill and can only recover if she is surrounded with flowers. In the meantime, Gondry has been attached to an adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s Ubik (1969). As in Dick and Kaufman’s work, Gondry’s films blur reality and fantasy, and all three invite philosophical responses to their art. Another French director, Jean-Pierre Gorin, co-founder with JeanLuc Godard of the Dziga-Vertov Group (1968–72) of radical filmmakers, had met with Dick in 1974 to discuss adapting the novel, but had been unable to raise the finances. Others have tried over the following decades, including Tommy Pallotta, the producer of A Scanner Darkly, and Celluloid Dreams in association with Electric RoboCop is one of the films that has to be remade in Be Kind Rewind

29

30

BFI FILM CLASSICS

Shepherd, the production company of Dick’s estate. In April 2014, Gondry suggested in an interview to Télérama that he did not think it had the right dramatic structure for a film,31 although a few days later he told a website that ‘Ubik wouldn’t be his next film […] but he did give us a hint as to what his next project might be. It is, he said, “A kids’ story about a road trip in France.”’32 It might yet be that Gondry will return to science fiction.

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

2 Science Fiction While Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is not just a sciencefiction film – no film ever belongs to just one genre – it does fit within the parameters of the genre. The origins of sf lie in the work of writers such as Mary Shelley, Edgar Allan Poe, Jules Verne, H. G. Wells and others, with its formalisation as a genre in the pulp-fiction magazines of the early twentieth century. One of the French cinema pioneers, Georges Méliès, produced a number of films that could be seen as science fiction, including Le Voyage dans la lune (A Trip to the Moon, 1902). These trick films exploit the simple special effect of what would happen if filming is interrupted and an object placed before or removed from the field of view before recommencing. This technique has been exploited both physically and digitally by Gondry in his films and videos, with cast and crew sometimes removing or adding objects (including costumes) between shots or when out of shot – when Joel sees himself in the Lacuna Inc office, this was achieved by Carrey changing costumes and running around the back of the camera before it panned to where he was sitting. The sequence in the childhood kitchen is achieved through sets, camera angles and forced perspectives. Various versions of Joel’s disintegrating memories, such as the decaying of the beach house, are sometimes achieved through stop-motion photography. J. P. Telotte suggests that Méliès developed an aesthetics that ‘delighted in a new-found plasticity and fragmentability, a sense that our technologies were making it possible to compartmentalize, rework, and reshape our world’.33 This encapsulates the sf film – a series of strange effects that acts as a spectacle. Part of Gondry’s technique is to abandon continuity editing at various moments, thus disorienting the viewer’s map of the diegetic space; match cuts can move a character from place to place or present to past, from the

31

32

BFI FILM CLASSICS

Charles River to Grand Central Station, apparently seamlessly. The camera moves from the bookstore with Joel to the Eakins’ house; later the interior of the bookstore is visible from the restaurant, as if they are a continuous space. Gondry sometimes also uses a tight focus on Carrey, blurring out and distancing him from the background, or uses artificial light on him while his surroundings are darkened. While written sf is the literature of ideas, in science-fiction film at times the ‘spectacle seems to overpower the speculation’.34 The science-fiction writer Philip K. Dick, someone both Kaufman and Gondry have attempted to adapt for the cinema, attacked such films: ‘For all its dazzling graphic impact, Alien (to take one example) had nothing new to bring us in the way of concepts that awaken the mind rather than the senses.’35 This was written in the context of him feeling left out of the production process of Blade Runner (1982), and is perhaps blind to the pleasures of the spectacle and the sublime in their own right. Susan Sontag had already argued that ‘in place of an intellectual workout, they can supply something the novels can never provide – sensuous elaboration’.36 Ideally the imagery triggers some kind of thought process, allowing the real world to be viewed with fresh eyes. Science and Technology John Brosnan begins his history of the sf film by ‘stating that science fiction must involve science in some way. It is not fiction necessarily about science but fictions that invariably use science as a basis for extrapolation.’37 This should be contrasted with Sontag’s view that ‘Science fiction films are not about science’,38 although her insistence that ‘They are about disaster’ seems less relevant to Eternal Sunshine other than on the level of the personal disaster. Science is less important to science-fiction film than the characteristics of scientists and the implications of their discoveries or inventions. Scientists are frequently represented as absent-minded at best and mad at worst, and it is the impact of the technology that develops from their

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

discoveries that normally forms the mechanism of the science-fiction plot. The scientist at the heart of Eternal Sunshine is Dr Howard Mierzwiak, an apparently kindly figure offering what appears to be a much-needed service, but who is also paternalistic and has used his invention to cover up his affair. Science-fiction film foregrounds technology and, through the spectacle of that technology, foregrounds the technology of representation and the act of looking. Some effects efface themselves and attempt to be invisible, whereas others – in part because of their sheer impossibility – announce themselves as being special, often pausing the narrative flow to allow for a moment of wonderment. In the sequence in Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), the characters watch the arrival of the alien mothership in awed silence, some of them dropping to their knees as if to pray. However, Gondry’s special effects aspire less to a quasirealism, if anything adding to the spectacle by ensuring that cardboard models could not be mistaken for reality in La Science des Rêves, The We and the I and, for comic reasons, Be Kind Rewind. On the one hand, technology must be dangerous to the protagonists as plots demand problems and complications – the creation malfunctions or cannot be controlled, the Earth (or another location) is threatened, the technology allows someone to terrorise others and so forth. Bruce F. Kawin, comparing sf to horror film, suggests that the latter works to discredit curiosity by demonstrating its dangers. He claims that science fiction is more open to otherness than horror: Both horror and science fiction open our sense of the possible (mummies can live, men can turn into wolves, Martians can visit), especially in terms of community […] Most horror films are oriented toward the restoration of the status quo rather than toward any permanent opening.39

There are things with which humans are not meant to meddle; the horror narrative punishes characters who step out of line. Sf, in

33

34

BFI FILM CLASSICS

general, has a more approving relationship with the quest for scientific knowledge and of difference: it ‘is open to the value of the inhuman, one can learn from it, take a trip with it’.40 Christopher Grau asserts that ‘Eternal Sunshine, unlike some science-fiction films, is not in love with the new technology it showcases.’41 I would argue in fact that much sf film is ambivalent about technology – with the exception of spaceships and other transportation, which are often futuristic substitutes for cars, trains and aeroplanes – despite its deployment of technology in the production of the images. While Gondry embraces a lo-fi aesthetic at times, the list of effects technicians on the credits of Eternal Sunshine and other films demonstrates some reliance on CGI – the way in which the people vanish from Grand Central Station suggests more than start-stop filming. On the other hand, because plots demand spectacle, the technology may appear wondrous – the creation transports the protagonists through space or time, transforms them or creates marvels. In Being John Malkovich, for example, the portal between the back of the filing cabinet, Malkovich’s perception system and the

The portal into Malkovich’s brain in Being John Malkovich

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

New Jersey turnpike is hardly explicable by science. The film has much in common with fantasy, whether in terms of the magic associated with much of that genre or with wishfulfilment for its characters or its audience. The contingent genres of horror and fantasy have attracted psychoanalytic readings; this book will continue that tradition. Amnesia and Anamnesia The technology in Eternal Sunshine is focused on memory and artificially induced amnesia. The exploration of memory is a theme that has been especially prominent within sciencefiction film for the last thirty years or more, with Blade Runner an early example. The androids or replicants have been implanted with artificial memories in order to give them an emotional base. Rachael (Sean Young), for example has no idea that she herself is not human. For some of the replicants, their ‘memories’ are represented in photographs, insistent proof of the existence of their pasts, and it is unclear whether the pictures on Deckard’s (Harrison Ford) piano are from Rachael’s or his own family history. There has been speculation over the years that Deckard is also a replicant and does not know this. The implication is that without a past to anchor us, we are adrift in the present. Joel is certainly traumatised when he wakes up without part of his past and Clementine does not seem to be making rational decisions. Blade Runner was based upon Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968), a novel by Philip K. Dick, whose stories sometimes Paycheck’s memory-erasing machine was inadvertently echoed by the one used by Lacuna Inc in Joel’s apartment

35

36

BFI FILM CLASSICS

also deal with false memories and may have been an influence on Kaufman. In ‘I Hope I Shall Arrive Soon’ (1980), a spaceship’s computer attempts to keep Victor Kamming, one of its passengers, occupied with false memories as the cryogenic equipment has failed. The computer draws on real memories, but each one in turn becomes traumatic. By the time the passenger reaches his destination, he believes reality to be a hallucination. In this case, Kamming’s underlying psychological make-up breaks through whatever memories have been grafted onto him, suggesting that there is a sense of identity that is not linked to memory. Encounters with people and objects that he has known trigger recall of earlier behaviour patterns. This also seems to be the case in Eternal Sunshine, where Joel becomes the shy and nervous but attracted suitor when seeing Clementine again. As Frederika Shulman argues, ‘Artifacts […] transmit who and what we are via social and cultural myths, memories and practices. Even if such objects are relegated to the status of repository of memory they necessarily convey a history

Deckard and Rachael both have their memories in Blade Runner (1982)

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

much larger than themselves.’42 This explains why the memoryerasing process has both an inner and outer component. Clients are instructed to gather together any objects that are connected with the loved one: photos, clothing, gifts, books, CDs and journal entries. A personalised mug or a potato doll is an uncanny double of Clementine; Joel’s encounters with such objects will conjure up Clementine. Similarly, Patrick’s gift of some jewellery, which Joel has bought for but not given to Clementine, make her begin to fall in love with the technician. An object offers anamnesia, unforgetting. Shulman notes ‘even though these objects have been displaced from their original context in Joel’s collection, the memories they embody remain ever present’.43 The jewellery is not enough to convince Clementine fully – Joel as object is missing – nor is it immediately clear how Joel and Clementine’s return to Montauk is triggered. For Joel, it may be the bird-house mobile hanging in his bedroom window that has an association with the beach house. Objects as triggers are also present in Dick’s story ‘Paycheck’ (1953), filmed by John Woo in 2003. Here an electronic engineer works on a secret project under a contract that requires his memory to be wiped afterwards, and his payment turns out to be a number of everyday objects. Each of these objects leads him out of trouble with the secret services and towards a better financial reward. Woo’s film transforms a minor Dick story into a thriller, with a memory-wiping helmet that was inadvertently echoed by the one in Eternal Sunshine: Memory in commodity form: the personalised mug is a concrete memory of Clementine

37

38

BFI FILM CLASSICS

‘this machine they had on his head is exactly the one they designed for Eternal Sunshine’.44 False or occluded memories were also central to ‘We Can Remember It for You Wholesale’ (1964) – a very loose inspiration for the two versions of Total Recall (1990, 2012). Doug Quail approaches Rekall, Inc, to purchase the memory of a vacation on Mars. In rewriting his memories, it transpires that Quail has actually been to Mars, and the collision of real with falsified memories will cause psychological breakdown. They overlay his memories with an unlikely wish-fulfilment experience, where Quail has saved the Earth from an invasion by mice-like aliens, only to discover that this too appears to have happened. Again, the filmed versions are action thrillers rather than philosophically nuanced examinations of identity. Yugin Teo argues that the replicant memories of Blade Runner, the implanted but authentic memories of Total Recall, the recorded memories of Strange Days (1995) and the induced amnesia of Dark City (1998) are driven by ‘the commodification of memory, with the use of technology in creating false or prosthetic memories’.45 But Teo underplays the role of objects – shared or gifted commodities – in the memory-erasure process in Eternal Sunshine. Lacuna Inc is a business not a charity. Mary insists to a client that three times in one month is too many erasure processes, but from this it is clear that Lacuna Inc will sell the service more than once. The Fantastic In Eternal Sunshine, we move between the imagined world of the diegesis and worlds imagined or remembered within the diegesis. We have to make strategic decisions about the reality status of the various scenes we are watching: is this meant to be real or imagined? We have to distinguish between the Joel who is going have his memories wiped (or has had them wiped) and the Joel of his memories. Joel himself is sometimes aware of the memory-erasing procedure and Clementine – more precisely Joel’s image of Clementine – sometimes knows she is part of his memories, hiding from the erasure. We witness Joel’s

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

memories, his visit to (or his memory of his visit to) Lacuna Inc, Stan (Mark Ruffalo), Patrick, Mary and Howard erasing his memories and so on. Joel also appears as himself in some of these sequences, interacting with Howard. Joel’s hyper-fictional memories collide with the fictional erasing procedures at which he is present. He cannot see all of the scenes – he waits in the car when Clementine is in her apartment, Mary resigns from Lacuna and Stan and Hollis (Deidre O’Connell) interact outside Joel’s apartment – but these could be figments of his imagination. We see his memories from outside – in Being John Malkovich we do see what Malkovich sees. Sometimes we are unable to decide the status of what we are watching. This undecidability of what is real or imagined is characteristic of what Bulgarian-born literary theorist Tzvetan Todorov labels the fantastic. He describes as marvellous those stories in which cloaks of invisibility, seven-league boots and selective memory-wiping are to be considered possible. The reader engages in a willing suspension of disbelief – in film terms the diegesis is to be taken as real. In other narratives, such unlikely objects or events have a rational explanation – it was all a dream, a hallucination or a con trick. Todorov labels this genre, a little awkwardly as it echoes a rather different Freudian term, ‘the Uncanny’. When the audience cannot decide between marvellous and uncanny interpretations, we are in the realm of the fantastic. Todorov chose Henry James’s novel The Turn of the Screw (1898) as his key, perhaps even his only, exemplar, with more familiar genre fantasies notably absent. The work of David Cronenberg, David Lynch and Terry Gilliam fit in this category, and Kaufman’s script for Confessions of a Dangerous Mind does not want to confirm Barris as assassin or impostor. Sf may be marvellous: The initial data are supernatural: robots, extraterrestrial beings, the whole interplanetary context. The narrative movement consists in obliging us to see how close these apparently marvellous elements are to us, to what degree they are present in our life.46

39

40

BFI FILM CLASSICS

At the same time, since science offers potential rational explanations, sf may be uncanny. The ambiguity allows for fantastic readings. Alongside Joel’s image of Clementine, we also have his image of Clementine’s self-image. In the Shooting Script for Eternal Sunshine, Clementine’s favourite book is The Velveteen Rabbit, a story of a toy rabbit who becomes real through being loved: Confessions of a Dangerous Mind (2002) hovers between memoir and fantasy; Clementine’s dolls are Freudian uncanny doubles of herself

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

‘by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joints and very shabby. But these things don’t matter at all, because once you are Real you can’t be ugly.’47

By the end of the tale, the worn-out toy has become a real rabbit. Gondry did not feel this scene worked; ‘It’s a pivotal moment, but it wasn’t playing,’48 Kaufman admitted. In the re-edited speech, Clementine talks about her dolls: ‘My favourite is this ugly girl doll who I call Clementine and I keep yelling at her, “You can’t be ugly, be pretty.” It’s weird. Like if I can transform her, I would magically change too.’ This holds out the hope that love can uncannily make her real – although this is Joel’s Clementine talking and there may be no such doll. At the end of Eternal Sunshine, after their reconciliation, we see Joel and Clementine on the beach at Montauk. It is ambiguous as to whether this is a subsequent excursion, part of their unknowing reunion, one of Joel’s memories or a memory that may well be erased. There is no certainty that Joel has had the erasing device removed and the ending could be a wish-fulfilment fantasy. The ending is open rather than closed. Once a hallucination has been experienced, it may not be clear when it has ended. This is not the only science-fiction film where we may entertain such doubts. Deckard falls asleep at his piano in Blade Runner, so all of the events that follow may be a wishfulfilment dream, in Videodrome (1983), Max Renn (James Woods) is seen donning the virtual-reality headset but not removing it and at the end of Total Recall, the characters speculate that they might be part of Quaid’s dream. It might be noted that all of these films are about male dreams and rememberings – Joel appears to be the only male character to have his memory erased in Eternal Sunshine.49 In fictional works, we make a distinction between the shared world of the creator and their audience and the world depicted within the text, the diegetic world. When characters dream, hallucinate or themselves look at films, television programmes, plays or books, we have a further world, fiction within the diegesis. It is tempting to see these different frames as being like nested Russian

41

42

BFI FILM CLASSICS

dolls, one inside the other – reality, fiction, metafiction – but with the realisation both that there may be metametafictions and beyond – dreams within dreams within dreams, a vertiginous mise en abîme – and the worrying possibility that the audience themselves may not be privileged observers but are themselves fictional characters. This is dramatised in Welt am Draht (World on a Wire/World on Wires, 1973) and The Thirteenth Floor (1999), when characters using what we would now call virtual reality discover that they themselves are part of a fictional world. Dick was renowned for such set-ups, for example, Time Out of Joint (1959), in which Ragle Gumm, an apparent layabout who solves a daily newspaper competition ‘Where will the Little Green Man appear next?’, discovers the whole town around him has been constructed to contain his trauma. This offered loose inspiration for Andrew Niccol’s script of The Truman Show, in which Truman Burbank (Jim Carrey) is unwittingly at the heart of a television reality show. The audience for Eternal Sunshine may well bring this memory of Carrey’s oeuvre to the film. Aside from the vanishing text and blurring faces, each ‘level’ of world within Eternal Sunshine looks very similar – (fictional) real Quaid dreams of a life on Mars in Total Recall (1990) – but it isn’t necessarily a dream. Or maybe it is …?

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

New York and Montauk, (fictional) remembered New York and Montauk – because the film-makers are using identical camera and editing techniques to depict them. The film depicts both reality and illusion within its diegesis or diegeses. The paintings of René Magritte are similarly metafictional, for example, La Condition humaine (The Human Condition, 1933) that depicts a painting of a landscape on an easel in front of a window, through which part of that landscape is visible. As I have argued As the painting-within-a-painting is made of the same materials as the painting itself, how can we tell that any painting by Magritte – or any artist, for that matter – is not a painting-within-a-painting, with the borders of both coinciding? Both paintings are constructed from the same paint and are painted on the same surface; it hardly makes sense to talk of a primary and secondary painting.50

How can we tell that a scene is real rather than part of Joel’s memories or imagination? In the end, none of it is reality – in Eternal Sunshine, these are all parts of a film. Gondry’s use of hand-held or The Truman Show: Truman is part of his own fantasy – and television’s

43

44

BFI FILM CLASSICS

slightly moving cameras in Joel’s real life, memories and imagination and in scenes from which he is absent does not offer a convenient means of distinction. The ending, whether real or fantasised, is a familiar generic one for the sf film, where the protagonists leave the city with its alienations of law, order and capitalism and retreat to the utopian countryside – in Blade Runner, Deckard and Rachael fly off into the sunset from a rainy, dark metropolis, possibly to live happily ever after and in Brazil (1985), Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce) and Jill (Kim Griest) drive to a bucolic, pastoral world, although the closing shots undermine this. The precogs in Minority Report (2002) and the lovers Michael Jennings (Ben Affleck) and Dr Rachel Porter (Uma Thurman) and their friend Shorty (Paul Giamatti) in Paycheck all find a better life outside the city, while John Murdoch (Rufus Sewell) in Dark City makes the conceptual breakthrough to discover where he really is by reaching Shell Beach and being reunited with Emma/Anna (Jennifer Connelly). Pleasant times for Joel and Clementine on the beach at Montauk, at the eastern side of the Hamptons, take them away from New York. Love can be found in the green world outside the city.

The end of the beach is ambiguous – reality, memory or fantasy?

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

3 The Comedy of Remarriage Like most popular genres, such as science fiction, comedy is regarded with a degree of suspicion by critics, perhaps because of a long-held suspicion that its pleasures are too easily acquired. It is perceived to be merely entertainment, offering no serious commentary on the human condition. Aristotle’s Poetics argues ‘comedy aims at representing men as worse than they are nowadays, tragedy as better’,51 but the prejudices against comedy still hold two millennia on. Aristotle’s extension of Plato’s model of art as mimesis links comedy to the ugly and the deformed, rather than to the beautiful, with a class-based division of tragedy invoking the fall of great men, whereas comedy is either more plebeian or involves people from outside the city (who are thus supposedly uncouth). A product of a more democratic age, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind does offer many pleasures, some of them comic, as well as spectacle, but it also allows an exploration of human nature and desire. While the nuances of narrative structures will be discussed in the next chapter, in this I want to discuss some of the subgenres of comedy, in particular, romantic comedy and the comedy of remarriage. Traditionally, narratives begin with a disruption of the social order – something inconveniencing the protagonist, ideally deriving from a flaw in their character – and end with a social ritual, depicted or implied, restoring the rule of law. In tragedy, this tends to be a funeral; in comedy, a marriage, both restoring the rule of law and serving the needs of patriarchy. The Romantic Comedy One subgenre of comedy is the romantic comedy. The situation where two people argue with each other until they finally realise that they are in love is not original to film – Beatrice and Benedick in

45

46

BFI FILM CLASSICS

William Shakespeare’s Much Ado about Nothing (c. 1598) and Elizabeth Bennet and Fitzwilliam Darcy in Pride and Prejudice (1813) spring to mind – but the genre had flourished with the sound cinema of the 1930s. Writers, directors, actors and audiences took pleasure in pushing the possibilities of synchronised sound to the limits, glorying in rapid, sharp and even overlapping dialogue. Tamar Jeffers McDonald sees the characters’ speech as part of the seduction process: ‘While sex was postponed, the couple had to engage in verbal foreplay which substituted for, forecast and enticed the other towards, the final act.’52 The Motion Picture Production Code forbade the depiction of on-screen sexual intercourse, so it was necessary for it to take place off screen and ideally post-film. The film might follow the characters to the altar or to the bedroom door, but no further. At the same time, the form was not necessarily conservative – it put strong female leads such as Katharine Hepburn, Myrna Loy and Irene Dunne into positions of quasi-equality with or even superiority over the male characters. Romantic comedy traces the shifting power relations between the sexes, sometimes granting more power to the men, sometimes to the women. The process of coupling may be questioned – as it is in Eternal Sunshine with Clementine’s (apparently rehearsed) speech that men are not there to complete her and Joel’s cruel assertion that she offers to have sex with people so that they will like her. Romance as fulfilment implies a sense of a lack in the lovers. The cynicism of the 1970s has largely given way to a more traditional, even more conservative, resurgence of romantic comedy where happiness for the man outweighs the needs of the woman – as it might with Joel. Marriage is once more seen as completion and, despite the introduction of gay, bisexual and transgender characters, mainstream romantic comedy remains focused on heterosexual relationships. Steve Seidman notes that there are several variations of sexual confrontation in the Hollywood romantic comedy: ‘carefree female versus misanthropic male, decadent male versus sexually repressed

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

female, husband versus wife, ex-husband versus ex-wife [… but the romantic comedy] reaffirms marriage as a culturally important institution’.53 Despite the outrageous behaviour of Reede in Liar Liar (1997), his ex-wife Audrey (Maura Tierney) and son Max (Justin Cooper) take him back. Clementine and Joel fit best into the first of these variants – although Clementine insists in her apartment that she is going to marry him, there are two moments that echo the words of the marriage service. Joel, when returning to his apartment, says ‘Oddly enough, I do’ to Clementine and she responds, ‘I guess that

‘I do’

47

48

BFI FILM CLASSICS

In search of a missing bone in Bringing Up Baby (1938)

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

means we’re married’54 and later, recalling their trespass at the Laskins’ beach house, Joel says ‘I wish I’d stayed. I do.’55 The two ‘I dos’ perform the ceremony that make them husband and wife. The strictures of the Motion Picture Production Code emphasised the tension between desire and consummation of desire in the romantic comedies of the classical Hollywood period. While Susan Vance (Hepburn) and David Huxley (Cary Grant) can play any number of games in Bringing Up Baby (1938), desire can only be symbolised obliquely through Huxley’s lost (dinosaur) bone and even when Henri Rochard (Cary Grant again) has married Catherine Gates (Ann Sheridan) in I Was A Male War Bride (1949), the consummation of their union is postponed. But the relaxation of the Code and decline of the studio system during the 1960s reduced the taboo against fornication. Brian Henderson argues that: romantic comedy is about fucking and its absence, this can never be said nor referred to directly. [… Romantic comedy] implies a process of perpetual displacement, of euphemism and indirection at all levels, a latticework of dissembling and hiding laid over what is constantly present but denied.56

By 1978 – and certainly by 2004 – there was little problem representing sex. It can be assumed that Joel and his earlier girlfriend Naomi have had a sexual relationship, we are discreetly shown Joel and Clementine, Joel makes it clear that Clementine has fucked other people, presumably including Patrick, and Mary has had sex with both Stan and Howard. Even so, moments of Joel and Clementine getting together are delayed – the scene cuts from Clementine going to get her toothbrush so that she can go back to Joel’s place to a post-erasure moment, the erasing processes themselves delay matters and then, when reconciliation seems likely, the tape of Joel’s recollections hurts Clementine. Delayed gratification remains a part of the narrative. In romantic comedy, a distinction has emerged between casual and committed sex, one just a way of getting someone else to like you and being about personal pleasure and the other a more empathic,

49

50

BFI FILM CLASSICS

shared connection. Henderson divides romantic comedy into old and new love – the former of married couples whose marriages are under strain, the latter of people meeting for the first time, becoming friends and having sex: ‘In comedies of old love, the unspoken question is “Why did we stop fucking?” In comedies of new love, it is “Why don’t we fuck now?” ’57 In post-classical Hollywood, there seems little reason to stop or against starting. The Green World In a number of Shakespeare’s romantic comedies, the characters have to leave the repressed and uptight city to go to the countryside to resolve their relationships. The usual rules of decorum are suspended in favour of a free-flowing set of desires, from which new relationships emerge. Northrop Frye argues ‘the action of the comedy begins in a world represented as the normal world, moves into the green world, goes into a metamorphosis there in which the comic resolution is achieved, and returns to the normal world’.58 Freed from the dictates of work and the opinions of neighbours, the lovers are able to choose their best match, liberated from common sense. The green worlds in Eternal Sunshine are Montauk Beach and, to a lesser extent, the frozen Charles River near Boston. Joel’s former lover, Naomi, remains unseen, behind in the city, as he goes to the carnival space of a party on a beach. Clementine breaks into his standoffish mindset and helps herself to his chicken, breaking the bounds of decorum, but also sharing an act of communion. It is on the perilous ice that Joel and Clementine really come together – he risks hurt to let himself fall in love – and Clementine realises that Patrick is not the one for her. However, it is back at the beach that their reunion takes place. In the tangled time scheme, the memory of their first meeting is also the moment when remembering Joel and remembered Clementine decide to reunite, but the movement between worlds is preserved. As part of Frye’s association of genres (comedy/romance/tragedy/irony and satire) with the cycle of the seasons (spring/summer/autumn/winter), the green world allows for

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

The beach operates as a green world where Joel can learn to play

51

52

BFI FILM CLASSICS

‘the symbolism of the victory of summer over winter’,59 but the irony of Eternal Sunshine with its Valentine’s Day and November settings, the frozen river and the snow-covered beach questions this triumph of romantic comedy. The Comedy of Remarriage Some of the reviews of Eternal Sunshine locate it as an example of Stanley Cavell’s genre of the comedy of remarriage. David Edelstein suggests Kaufman’s revisioning of the screwball genre is The Awful Truth turned inside-out by Philip K. Dick, with nods to Samuel Beckett, Chris Marker, John Guare – the greatest dramatists of our modern fractured consciousness. But the weave is pure Kaufman. No one has ever used this fantastic a premise to chart the convolutions of the human brain in the throes of breakup and reconciliation.60

A. O. Scott notes Edelstein’s linkage and claims that Kaufman is using the genre to explore ‘a set of ethical puzzles and epistemological conundrums of the sort illuminated in the work of sages like Plato, Emerson, Wittgenstein and Kant’.61 Scott’s reading of Cavell argues that Eternal Sunshine echoes the 1930s and 40s comedies of remarriage that advocate we strive through grace, self-knowledge and luck to be true to our loved ones rather than to be perfect for them. In Eternal Sunshine, what appears to be new love is in fact old love. The encounter at the beach and on the train at Montauk is of two people who had already been together for two years and have erased the memory of their relationship. Their actual first meeting on the beach as remembered by Joel serves to be the location for their conversation about getting back together again – or, rather, Joel deciding that he wants to reunite with Clementine. The fact that Clementine is either the seducer, or imagined to be the seducer, in fact looks back to the 1930s screwball romantic comedies: ‘Much like classic screwballs such as Bringing Up Baby (1938), the film reveals

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

how the pursuit by the female aggressor works to liberate the stuffy, reserved or reticent male partner.’62 The tension here is that while the female character is the active agent of the narrative, the film becomes about the man’s emotions. Cavell repeats Henderson’s distinction between old and new love, ascribing it to Frye: New Comedy stresses the young man’s efforts to overcome obstacles posed by an older man […] to his winning the young woman of his choice, whereas Old Comedy puts particular stress on the heroine, who may hold the key to the successful conclusion of the plot.63

The heroine is likely to be married, may be disguised as a boy and ‘may undergo something like death and restoration’.64 Cavell identifies and discusses a number of films from the 1930s and 1940s – It Happened One Night (1934), The Awful Truth (1937), Bringing Up Baby, The Philadelphia Story (1940), His Girl Friday (1940), The Lady Eve (1941) and Adam’s Rib (1949) – where the narrative drive ‘is not to get the central pair together, but to get them back together, together again’.65 The films centre upon a number of pairings that are being driven apart by a quarrel, despite the fact that the couples have ‘known one another forever, that is from the beginning […] before history’.66 They have – or create – a childhood together, as if they are sister and brother who have discovered sexuality together, although presumably the literalness of this has to be limited by the incest taboo that that would break. Cavell suggests that these films are reworkings of the sort of narrative present in Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale (c. 1611), told as fairytales in the context of the 1930s Depression when there was a group of actors (Claudette Colbert, Irene Dunne, Katharine Hepburn, Rosalind Russell, Barbara Stanwyck and Merle Oberon) of appropriate age and skill to play the married heroine. The rural Bohemia of The Winter’s Tale is the Shakespearean green world identified by Frye, and Cavell sees such spaces in his comedies of remarriage:

53

54

BFI FILM CLASSICS

this locale is called Connecticut. Strictly speaking, in The Lady Eve the place is called ‘Conneckticut,’ and it is all but cited as a mythical location, since nobody is quite sure how you get there, or anyway how a lady gets there.67

The choice of that location may be to do with the perceived ease of marriage there – in The Red Right Hand, the novel read by Clementine in the Shooting Script, the narrator notes ‘Even people who lived in New York all their lives are apt to think of Connecticut an elopers’ paradise, perhaps because Greenwich is the first railroad station in that state, and its name is confused with Gretna Green’,68 suggesting that the choice of location for the comedies of remarriage is dictated by assumptions of easy marriage. Montauk and the Charles River offer green worlds for Eternal Sunshine and it is a mystery as to how Clementine knows to go to the beach after the erasure processes; when she is in her apartment with Patrick while Stan is erasing Joel, she suggests first going to Montauk and then to the Charles River; in the pretend goodbye scene in Joel’s imagination she whispers to him ‘Meet me in Montauk’, although this is not in the Shooting Script.69 Christopher Grau notes that the comedy of remarriage features ‘a separated couple ultimately getting back together through rediscovering why they fell in love in the first place. Eternal Sunshine follows that pattern, but with the novel twist of memory removal facilitating the “reunion.”’70 This is a little misleading – given it is either a flawed erasure process or coincidence that leads to the reunion in Montauk. Grau focuses on the morality of forgetting; while the removal of traumatic experiences might lead to greater happiness and be a utilitarian process, it would be a false kind of living. As in the science fiction of Dick, an authentic experience of dystopia is preferable to an ersatz illusion of utopia. Grau argues ‘our concern with knowing the truth comes into tension with our desire for happiness’.71 Remarriage, although Grau does not state this, is presumably best built upon uncomfortable truths rather than comfortable lies that may, in time, crack.

ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

Michael J. Meyer explores the ethics of reconciliation in remarriage. He attempts to locate Eternal Sunshine within Cavell’s genre but notes that a marriage is necessary first for remarriage to occur: ‘between Joel and Clementine there is neither marriage nor divorce nor remarriage’,72 missing the film’s uses of the marriage vow, ‘I do’. To sidestep this issue, Meyer redefines marriage as a close, committed friendship rather than as a legal institution that is often sanctioned by a religious ceremony. Remarriage is here a recommitment to the friendship, in the knowledge that it is a risk. The happy ending that marriage would imply is an uneasy one, not to be trusted. Meyer rightly pays attention to Mary – ‘a tragic if ultimately avenged subplot’73 – whose relationship with Dr Mierzwiak may be repeated through ignorance of her past and does not lead to reconciliation. Her lack of knowledge leads to poor judgment in this relationship, averted only by the arrival of Dr Mierzwiak’s wife, Hollis. There is an imbalance in their case, of course, as Mary is ignorant and Mierzwiak has knowledge of their affair; Joel and Clementine are both ignorant of what has happened. Meyer argues that their remarriage reconciliation puts an ‘emphasis on self-aware and mutual acceptance of personal and shared anxiety regarding the couple’s past and future friendship’.74 There is for Meyer an assertion that successful marriages are made from friendships built upon trust. William Day is critical of Meyer’s account, suggesting in effect that he has misunderstood by omitting ‘the central feature of the genre, the couple’s ongoing remarriage conversation’.75 Day notes the speechless nature of the coda set on Montauk beach that Meyer offers as ‘a symbolic spatial location for ethical transformation’, identifiable with Cavell’s (and Frye’s) green world.76 The reconciliation has happened on the beach: once in Joel’s unconscious mind and once in their unknowing reunion. The status of the coda is problematic – is it analeptic, proleptic or purely imaginary? Day argues that Eternal Sunshine’s ‘contribution to the genre is the story of coming to discover what it means to have memories together as a

55

56

BFI FILM CLASSICS