British Ethical Theorists from Sidgwick to Ewing (The Oxford History of Philosophy) 9780199233625, 0199233624

Thomas Hurka presents the first full historical study of an important strand in the development of modern moral philosop

129 59

English Pages 320 [325] Year 2015

Cover

British Ethical Theorists from Sidgwick to Ewing

Copyright

Dedication

Preface

Contents

Bibliographical Abbreviations

Henry Sidgwick

Hastings Rashdall

John McTaggart Ellis McTaggart

H.W.B. Joseph

H.A. Prichard

Bertrand Russell

G.E. Moore

E.F. Carritt

W.D. (Sir David) Ross

John Laird

C.D. Broad

A.C. Ewing

Introduction: British Ethical Theorists from Sidgwick to Ewing

1 Minimal Concepts

1.1 Thin Concepts

1.2 Deontic Concepts

1.3 Value-Concepts

1.4 Concepts and Claims

2 `Ought´ and `Good´

2.1 `Ought´ vs. `Good´

2.2 Reducing `Ought´ to `Good´

2.3 Reducing `Good´ to `Ought´: The Fitting-Attitudes Analysis

2.4 The Fitting-Attitudes Analysis: Objections

3 Kinds of Goodness and Duty

3.1 Intrinsic Goodness

3.2 Prima Facie Duty

3.3 Objective vs. Subjective Duty

4 Non-Naturalism

4.1 Moral Realism

4.2 The Autonomy of Ethics: The Open-Question Argument

4.3 The Open-Question Argument: Objections

4.4 Responses to Subjectivism

5 Intuitionism

5.1 Intuition and Self-Evidence

5.2 Sidgwick´s Conditions

5.3 Certainty and Inference

5.4 Levels of Intuition

6 Moral Truths: Underivative and Derived

6.1 False Derivations

6.2 Duty and Self-Interest

6.3 Theorizing Morality: Two Reasons

6.4 Theory vs. Anti-Theory

6.5 Degrees of Theory

6.6 Inherent Explanations

7 Consequentialism vs. Deontology

7.1 Sidgwick: Against Deontology

7.2 Sidgwick: For Consequentialism

7.3 Prichard, Carritt, Ross: Defending Deontology

8 Act-Consequentialism, Pluralist Deontology

8.1 Consequentialism: Act- and Indirect

8.2 Pluralist Deontology: Consequentialist Overlaps

8.3 Pluralist Deontology: Conflicts of Duty

8.4 Pluralist Deontology: Elaborations

9 Non-Moral Goods

9.1 What Is Pleasure?

9.2 Hedonism: For and Against

9.3 Aesthetic Appreciation

9.4 Knowledge and Achievement

9.5 Aggregating Goods

10 Moral Goods

10.1 Virtue: For and Against

10.2 Forms of Virtue

10.3 Personal Love

10.4 Moral Desert

11 Self-Benefit, Distribution, Punishment

11.1 Promoting Your Good

11.2 Distribution: Intrinsic and Instrumental Goods

11.3 Criminal Punishment

12 Historians of Ethics

12.1 Ancient Ethics

12.2 The British Moralists

12.3 Kant´s Ethics

Bibliography

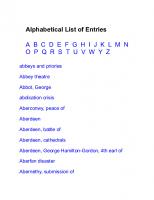

Index

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Thomas Hurka

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

T H E O X F OR D H I S T O R Y O F P H I L O S O P H Y

British Ethical Theorists from Sidgwick to Ewing

TH E O X F O R D HI S TO R Y O F P H I L O S O P H Y

The Lost Age of Reason: Philosophy in Early Modern India 1450–1700 Jonardon Ganeri Thinking the Impossible: French Philosophy Since 1960 Gary Gutting The American Pragmatists Cheryl Misak

British Ethical Theorists from Sidgwick to Ewing Thomas Hurka

1

3

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries # Thomas Hurka 2014 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2014 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2014937977 ISBN 978–0–19–923362–5 Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

In memory of Dennis McKerlie

Preface This book’s origins lie in an ethics seminar I took in 1975 in my last term as an undergraduate at the University of Toronto. Taught by Wayne Sumner, the seminar excited me in part because, whereas I had mostly studied history of philosophy, its readings were often very current. The subject was utilitarianism, but Wayne fairmindedly included material on competing views. Here, however, his choices were more classical. For an alternative to the utilitarian account of the good we read the last chapter of Moore’s Principia Ethica, and for a deontological rival chapter 2 of Ross’s The Right and the Good. To me these readings were the highlight of the course. Moore’s ideal or perfectionist account of the good resonated with what I had read in my historical courses and with views I had grown up with, and his principle of organic unities expressed more clearly ideas in the Hegel I had (unaccountably to me now) done special courses on. I also admired Ross’s sharpness in framing the consequentialist/deontological debate and defending his side of it, and found the philosophical styles of both writers congenial. The seminar converted me to ethics as a branch of philosophy, but when I went to Oxford to do graduate degrees in it there was little call for further study of Moore or Ross. Their non-naturalist metaethics was still widely regarded as decisively refuted, and in any case the primary focus then was on normative ethics, which was enjoying a revival in the wake of works like A Theory of Justice and Anarchy, State, and Utopia. The revival was largely self-contained, seeing itself as starting afresh rather than needing much guidance from writers earlier in the century. Sidgwick, who had just been rediscovered, was seen as an exception, and in him I found many of the same merits as in Moore and Ross; when Rawls listed Rashdall as a perfectionist, I read him and found his work, too, engaging. So my interest in the philosophers of this period continued. But in the late 1970s there was for the most part little profit for a graduate student in studying them and certainly no encouragement to do so. Philosophy goes in cycles, and what one generation finds not worth reading another thinks has too long been undervalued. So in recent years the moral philosophers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries have slowly been regaining prominence. Sidgwick’s status as the greatest of the classical utilitarians has only solidified, and one now more often sees references to Moore on organic unities, Ross on prima facie duties, Prichard on ‘why be moral?’, Broad on self-referential altruism, and Ewing on ‘good’. It therefore occurred to me that a book on an era that made those and other contributions might now meet with interest. The history of philosophy involves facts, and it took me some considerable time to identify and organize the thoughts of nine sometimes very productive philosophers on all the subjects they addressed. Both that work and the writing that followed were

viii

preface

supported by research grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, as well as a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2006–7 and a Killam Research Fellowship from the Canada Council in 2011–13; during those last two years the bulk of the book was written. I am grateful to all three institutions for their generous and patient support. Some material in the book was published previously in ‘Moore in the Middle’, Ethics 113 (2003), ‘Underivative Duty: Prichard on Moral Obligation’, Social Philosophy and Policy 27, no. 2 (2010), and ‘Sidgwick on Consequentialism vs. Deontology: A Critique’, Utilitas 26 (2014). I thank these journals and their publishers for permission to reprint this material. Rob Shaver and Wayne Sumner read drafts of the complete manuscript and gave me doubtless too-uncritical comments on them. I am grateful to them as well as to David Phillips and another, anonymous referee for Oxford University Press. I also benefited from discussions on more specific topics with, among others, Roger Crisp, Jonathan Dancy, Stephen Darwall, Brad Hooker, Derek Parfit, Arthur Ripstein, Holly Smith, Philip Stratton-Lake, Sergio Tenenbaum, and Mark Timmons. My wife Terry Teskey helped me edit the book’s many successive drafts; I relied as always on her sound judgement and decisiveness. And I have a long-term debt to my former colleague at the University of Calgary, Dennis McKerlie. Likewise an Oxford graduate student in the 1970s, he shared my interest in the philosophers of this book’s period, and we had many conversations both about them and about moral philosophy more generally. He was an ideal philosophical interlocutor, often seeing things more clearly than I could; his own work, which he never promoted as much as other philosophers do, was first rate. Regrettably, health problems prematurely ended his philosophical career and then his life; this book is dedicated to his memory.

Contents Bibliographical Abbreviations

xi

Introduction: British Ethical Theorists from Sidgwick to Ewing

1

1. Minimal Concepts 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4

Thin Concepts Deontic Concepts Value-Concepts Concepts and Claims

2. ‘Ought’ and ‘Good’ 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4

‘Ought’ vs. ‘Good’ Reducing ‘Ought’ to ‘Good’ Reducing ‘Good’ to ‘Ought’: The Fitting-Attitudes Analysis The Fitting-Attitudes Analysis: Objections

3. Kinds of Goodness and Duty 3.1 Intrinsic Goodness 3.2 Prima Facie Duty 3.3 Objective vs. Subjective Duty

4. Non-Naturalism 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4

Moral Realism The Autonomy of Ethics: The Open-Question Argument The Open-Question Argument: Objections Responses to Subjectivism

5. Intuitionism 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4

Intuition and Self-Evidence Sidgwick’s Conditions Certainty and Inference Levels of Intuition

6. Moral Truths: Underivative and Derived 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6

False Derivations Duty and Self-Interest Theorizing Morality: Two Reasons Theory vs. Anti-Theory Degrees of Theory Inherent Explanations

22 22 25 33 40 44 44 50 52 58 65 65 69 78 86 86 93 98 101 108 108 112 117 119 128 128 131 135 138 141 147

x contents 7. Consequentialism vs. Deontology 7.1 Sidgwick: Against Deontology 7.2 Sidgwick: For Consequentialism 7.3 Prichard, Carritt, Ross: Defending Deontology

8. Act-Consequentialism, Pluralist Deontology 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4

Consequentialism: Act- and Indirect Pluralist Deontology: Consequentialist Overlaps Pluralist Deontology: Conflicts of Duty Pluralist Deontology: Elaborations

9. Non-Moral Goods 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5

What Is Pleasure? Hedonism: For and Against Aesthetic Appreciation Knowledge and Achievement Aggregating Goods

10. Moral Goods 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4

Virtue: For and Against Forms of Virtue Personal Love Moral Desert

11. Self-Benefit, Distribution, Punishment 11.1 Promoting Your Good 11.2 Distribution: Intrinsic and Instrumental Goods 11.3 Criminal Punishment

12. Historians of Ethics 12.1 Ancient Ethics 12.2 The British Moralists 12.3 Kant’s Ethics

Bibliography Index

150 150 158 165 172 172 178 183 186 194 194 198 203 205 211 216 216 221 228 232 237 237 244 252 259 259 267 272 281 299

Bibliographical Abbreviations Henry Sidgwick EEM

Essays on Ethics and Method, ed. M.G. Singer, 2000 (where possible Sidgwick’s shorter writings are cited from this volume)

EP

The Elements of Politics, 1891

GSM

Lectures on the Ethics of T.H. Green, H. Spencer, and J. Martineau, ed. E.E. Constance Jones, 1902

M

Henry Sidgwick: A Memoir, eds A. Sidgwick and E.M. Sidgwick, 1906

ME

The Methods of Ethics, 7th ed., 1907; earlier editions abbreviated ME1, ME2, etc.

OHE

Outlines of the History of Ethics for English Readers, 1886

PE

Practical Ethics: A Collection of Addresses and Essays, 1898

Hastings Rashdall ‘CAV’

‘The Commensurability of All Values’, 1902

E

Ethics, 1913

ICE

Is Conscience an Emotion?, 1914

‘LC’

‘The Limits of Casuistry’, 1894

‘PS’

‘Professor Sidgwick’s Utilitarianism’, 1885

‘PTP’

‘The Philosophical Theory of Property’, 1913

TGE

The Theory of Good and Evil, 2 vols., 1907

John McTaggart Ellis McTaggart ‘EHS’

‘The Ethics of Henry Sidgwick’, 1906

‘IV’

‘The Individualism of Value’, 1908

NE

The Nature of Existence, 2 vols., 1921 and 1927

SDR

Some Dogmas of Religion, 1906

SHC

Studies in Hegelian Cosmology, 1901

xii

bibliographical abbreviations

H.W.B. Joseph SPE

Some Problems in Ethics, 1931

H.A. Prichard MW

Moral Writings, ed. J. Macadam, 2002 (all Prichard’s ethical writings are cited from this volume)

Bertrand Russell ‘EE’

‘The Elements of Ethics’, 1910

G.E. Moore ‘A’

‘An Autobiography’, in P.A. Schilpp, ed., The Philosophy of G.E. Moore, 1942

‘CIV’

‘The Conception of Intrinsic Value’, in G.E. Moore, Philosophical Studies, 1922

E

Ethics, 1912

EE

The Elements of Ethics, ed. T. Regan, 1991 (contains the text of lectures given in 1898)

‘GQ’

‘Is Goodness a Quality?’, 1932

‘MME’ ‘Mr. McTaggart’s Ethics’, 1903 ‘NMP’ ‘The Nature of Moral Philosophy’, 1922 ‘P’

‘Preface to the Second Edition,’ in T. Baldwin, ed., Principia Ethica, revised edition, 1993 (written for a proposed second edition around 1921 but left unfinished and not published in Moore’s lifetime)

PE

Principia Ethica, 1903

‘R’

‘A Reply to My Critics’, in Schilpp, ed., The Philosophy of G.E. Moore, 1942

E.F. Carritt ‘AG’

‘An Ambiguity of the Word “Good”’, 1937

EPT

Ethical and Political Thinking, 1947

IA

An Introduction to Aesthetics, 1949

‘MP’

‘Moral Positivism and Moral Aestheticism’, 1938

TB

The Theory of Beauty, 1914

TM

The Theory of Morals, 1928

bibliographical abbreviations

xiii

W.D. (Sir David) Ross A

Aristotle, 1923

‘BO’

‘The Basis of Objective Judgments in Ethics’, 1927

‘EP’

‘The Ethics of Punishment’, 1929

FE

Foundations of Ethics, 1939

‘IME’

‘Is There a Moral End?’, 1928

KET

Kant’s Ethical Theory, 1954

‘NM’

‘The Nature of Morally Good Action’, 1929

RG

The Right and the Good, 1930

John Laird SMT

A Study in Moral Theory, 1926

C.D. Broad ‘A’

‘Autobiography’, in P.A. Schilpp, ed., The Philosophy of C.D. Broad, 1959

CE

Broad’s Critical Essays on Moral Philosophy, ed. D. Cheney, 1971 (where possible Broad’s shorter ethics writings are cited from this volume)

EHP

Ethics and the History of Philosophy: Selected Essays, 1952

EMP

Examination of McTaggart’s Philosophy, 2 vols., 1933 and 1938

FT

Five Types of Ethical Theory, 1930

‘R’

‘A Reply to My Critics’, in P.A. Schilpp, ed., The Philosophy of C.D. Broad, 1959

‘RSE’

‘Symposium on the Relations Between Science and Ethics’, 1941

‘SAP’

‘Are There Synthetic A Priori Truths?’, 1936

A.C. Ewing ‘BET’

‘Recent Developments in British Ethical Thought’, 1957

‘BVG’

‘Blanshard’s View of Good’, in P.A. Schilpp, ed., The Philosophy of Brand Blanshard, 1980

DG

The Definition of Good, 1947

E

Ethics, 1953

MP

The Morality of Punishment, 1929

‘PKE’

‘The Paradoxes of Kant’s Ethics’, 1938

xiv

bibliographical abbreviations

‘RI’

‘Reason and Intuition’, 1941

‘RSE’

‘Symposium on the Relations Between Science and Ethics’, 1941

‘SN’

‘A Suggested Non-Naturalistic Analysis of Good’, 1939

ST

Second Thoughts in Moral Philosophy, 1959

‘U’

‘Utilitarianism’, 1948

VR

Value and Reality, 1973

Introduction: British Ethical Theorists from Sidgwick to Ewing The subject of this book is a group of British ethical theorists active in the last quarter of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth, principally Henry Sidgwick, Hastings Rashdall, John McTaggart Ellis McTaggart, H.A. Prichard, G.E. Moore, E.F. Carritt, W.D. Ross, C.D. Broad, and A.C. Ewing. The group disagreed about some important topics in ethics. Several were consequentialists, believing the right act is always the one with the best consequences; others affirmed deontological duties that make some acts with the best outcome wrong. Sidgwick thought the only intrinsic good is pleasure; others recognized additional goods such as knowledge and moral virtue. Among the latter, some thought it good if a person gets what he deserves while others did not. But they shared other important views, first in metaethics. They were all nonnaturalists, believing moral judgements can be objectively true rather than, say, just expressing emotions, and have a distinctive subject matter, so they are neither reducible to nor derivable from ones about natural science, theology, or metaphysics; no ‘ought’ follows from an ‘is’. They were also intuitionists, believing we can know the moral truth by direct insight or intuition, either about principles or about particular cases. In addition, they shared a general approach to normative ethics. They agreed about which are the fundamental concepts for moral thought and which should be set aside or treated as derivative. They also shared, to differing degrees, a commitment to theorizing morality. They believed that whenever a particular moral judgement is true there is a general principle that makes it true, and a central task of normative ethics is to identify the ultimate such principles. A further view derived from their metaethics. Because of their non-naturalism, they believed that some moral judgements, the most explanatory ones, are underivatively true, in the sense that there is no further explanation, either non-moral or moral, of why they are true. If we ask why pleasure is good or why we have a duty to promote others’ good there may be no answer: it just is and we just do. Truths like these cannot be explained, and to try to explain them, as many philosophers have, is a mistake. This view shaped much of their moral theorizing. Because they thought claims about, for example, other-regarding duty can be underivatively true, they felt

2

british ethical theorists from sidgwick to ewing

no need to derive them from principles that use different concepts and concern some other, supposedly more fundamental topic. Instead, their explanations often cited principles that are continuous with the claim being explained, using similar concepts but at a higher level of abstraction. Because these principles tend to be too close to a more specific conclusion to persuade someone who does not already accept it to do so, the group’s work often focussed more on the inner structure and workings of our moral thought than on providing independent justifications of it. These shared views make the group a distinctive school in the history of moral philosophy, pursuing the subject differently than earlier writers such as Aristotle, Hobbes, and Kant and than many present-day ones. Unfortunately, I do not have a satisfactory name for them. They are sometimes called ‘non-naturalists’, but that refers just to one aspect of their metaethics and ignores their equally important commonalities in normative ethics. ‘Intuitionist’ has both metaethical and normative implications, but in this context the latter are misleading. An intuitionist normative view contains a plurality of duties but no formal rules for weighing them against each other;1 the term therefore does not fit consequentialists such as Sidgwick, Rashdall, McTaggart, and Moore. ‘Underivativist’ would highlight a key shared assumption of the school but is an ugly neologism. I will therefore speak only of the ‘Sidgwick-toEwing school’. The book has three main aims, of which one is just to report or recover the school’s ideas. Some of these are reasonably well known. Sidgwick is now widely regarded as the greatest of the classical utilitarians, and his Methods of Ethics has been the subject of several books.2 The first chapter of Moore’s Principia Ethica is for many the locus classicus for the defence of non-naturalism, and many also know his principle of organic unities. Prichard’s ‘Does Moral Philosophy Rest on a Mistake?’ is famous for rejecting the ‘Why be moral?’ question and Ross’s The Right and the Good for introducing the concept of a prima facie duty. But other aspects of the same writers’ work are less well known, such as Moore’s extreme indirect consequentialism, Prichard’s views on subjective vs. objective rightness, and Ross’s account of what is good; others in the school, such as Rashdall, McTaggart, Carritt, Broad, and Ewing, are barely known or read at all. So the book’s first aim is simply to describe their ethical views and the rich vein of thought they contain; one thing that will emerge is how often what have been regarded as new discoveries of recent moral philosophy were known and widely discussed in this earlier period. A second aim is to demonstrate the school’s unity, by elaborating and illustrating the commonalities mentioned above. That they shared important views has often been recognized, but there has not been a detailed explanation of what those are or how they differ from those of rival approaches such as Aristotle’s and Kant’s.

1 2

For this usage see Rawls, Theory of Justice, p. 34; Urmson, ‘Defence of Intuitionism’, pp. 111–12. Schneewind, Sidgwick’s Ethics; Phillips, Sidgwickian Ethics.

introduction

3

The final aim is to evaluate the school’s views. If they disagreed on some topic, such as consequentialism vs. deontology or hedonism vs. perfectionism, who had the better arguments? If they shared a position, how persuasively did they defend it? The book will not settle all these issues; whether non-naturalism is true, for example, is beyond its scope. But it will try to assess the school’s views and will often treat them sympathetically. In particular, it will argue that their general approach to normative ethics, with its focus on structure rather than external justifications, is more illuminating than the more grandiose projects preferred by many other philosophers. Because of its focus on a unified school, the book will not give a complete history of British moral philosophy in the relevant period. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries a rival and even more prominent approach to ethics was grounded in Idealist metaphysics and promoted by T.H. Green, F.H. Bradley, Bernard Bosanquet, and others. Their ideas will be discussed insofar as they generated critiques of our school and responses from them, but not in their own right; the same holds for naturalist and Kantian views. In the 1930s a challenge arose to nonnaturalism from the emotivism of A.J. Ayer and Charles L. Stevenson, later followed by the prescriptivism of R.M. Hare; these too will be discussed only as they drew responses from our school. The focus will only be on one, though an important, strand in British moral philosophy from around 1875 to 1960. The focus will also be primarily on the nine theorists listed above rather than on everyone who shared their general view. No utilitarians other than Sidgwick will get serious attention, and lesser ideal consequentialists such as Bertrand Russell, John Laird, W.A. Pickard-Cambridge, and H.W.B. Joseph will be mentioned only briefly, when a claim of theirs illustrates some broader consensus; the same is true of lesser deontologists such as J.L. Stocks. The book’s nine main figures were the most influential and philosophically interesting of the school, and there is more than enough to explore in them. The focus on a unified school has also shaped the book’s organization. Its treatment is not chronological, with a chapter on each member and covering all his views. It is thematic, with chapters on the different topics the school addressed and discussing all or most of their views on each. This format is better suited to highlighting their commonalities, topic by topic, and to analysing their differences with each other. Chapters 1 to 3 discuss their views on the moral concepts: which they took to be basic, how they saw the relations between the basic concepts, and how they understood specific forms of them such as intrinsic goodness and prima facie duty. Chapters 4 and 5 examine their metaethics, first their non-naturalism and then their intuitionistic moral epistemology. Chapter 6 discusses their general conception of moral theory, while Chapters 7 and 8 concern the theory of the right, one on the general debate between consequentialism and deontology and the other on the specific versions of those views defended by, principally, Sidgwick and Moore in the one case and Ross in the other. The next two chapters concern the theory of the good, Chapter 9 the non-moral goods of pleasure, aesthetic appreciation, and knowledge

4

british ethical theorists from sidgwick to ewing

and Chapter 10 the moral goods of virtue, personal love, and desert. Chapter 11 discusses duties to oneself, economic distribution and criminal punishment, and Chapter 12 the school’s views of earlier moral philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle, Butler, and Kant. This last chapter rounds out the book, since their criticisms of predecessors often reflected the school’s positive views and set them off by contrast. Like other philosophical movements, the school had a rise, an ascendancy, and then a decline. Its opening work was Sidgwick’s Methods, the first edition of which appeared in 1874. With its concern for precise statement and rigorous argument it reads very differently from earlier writing on ethics and is arguably the first philosophical work in a distinctively ‘analytic’ style. It was well received, as its six subsequent editions attest, and was followed in the 1880s and 1890s by some similar writing, including articles of Sidgwick’s defending his views and his Elements of Politics of 1891, and a series of articles by Rashdall. But those decades were dominated in many British universities by Idealist views with a very different flavour; the school was still emerging. The last years of the 1890s and the first decade of the new century saw a greater number of relevant works: in addition to articles by Rashdall, McTaggart, and Moore there were later publications by Sidgwick, such as his posthumous Lectures on the Ethics of T.H. Green, H. Spencer, and J. Martineau (1902), as well as McTaggart’s Studies in Hegelian Cosmology of 1901, which contained substantial discussions of ethics, Moore’s Principia Ethica of 1903, Rashdall’s Theory of Good and Evil of 1907, and Russell’s ‘The Elements of Ethics’ of 1910. The year 1912 saw Moore’s Ethics and Prichard’s ‘Does Moral Philosophy Rest on a Mistake?’, and 1913 and 1914 Rashdall’s Ethics and Is Conscience an Emotion?, and Broad’s first articles on ethics. The school was on the rise, and its period of ascendancy was the 1920s and 1930s. Those decades saw the publication of, again alongside numerous articles, the two volumes of McTaggart’s The Nature of Existence in 1921 and 1927, the second discussing value theory, Laird’s A Study of Moral Theory in 1926, Carritt’s Theory of Morals in 1928, Prichard’s lectures on ‘Duty and Interest’ and ‘Duty and Ignorance of Fact’ in 1928 and 1932, Ewing’s The Morality of Punishment in 1929, Ross’s The Right and the Good and Broad’s Five Types of Ethical Theory in 1930, Joseph’s Some Problems in Ethics in 1931, and Ross’s Foundations of Ethics in 1939. (Since the latter mostly refined the views of Ross’s first book, Broad gave it ‘the affectionate and accurate nickname of “The Righter and the Better” ’.3) Already, however, new winds were blowing, in the form of general philosophical movements: the logical positivism brought to Britain by Ayer in Language, Truth, and Logic of 1936 and the ordinary-language philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein in Cambridge and, differently, J.L. Austin in Oxford. To the younger philosophers in these movements the school’s approach to ethics was boring and old-fashioned. In a

3

Broad, Critical Notice of FE, p. 239.

introduction

5

1944 reference letter Isaiah Berlin said H.L.A. Hart, whom he thought too influenced by Joseph, would probably not be ‘a really distinguished epistemologico-logical highbrow’ but would produce work like ‘the solid pedestrian tramp of Ewing or Broad’; Hart himself worried that he was ‘a hack like Ewing’.4 This view solidified after the Second World War. In 1945 Sidgwick, Rashdall, and McTaggart were long dead, Prichard was seventy-four, and Moore, Carritt, and Ross were either over seventy or nearing that age. The school did continue to produce work. In 1947 Ewing published The Definition of Good, expanding the ideas in ‘A Suggested Non-Naturalistic Analysis of Good’ of 1939, and Carritt published Ethical and Political Thinking. Moral Obligation, a posthumous collection of Prichard’s writings on ethics, appeared in 1949, while in 1954 Ross published Kant’s Ethical Theory. Broad wrote articles on ethics from the late 1940s through 1964 and Ewing also remained active, publishing, alongside many articles, the trade-market Ethics in 1953 and Second Thoughts in Moral Philosophy in 1959, while Value and Reality, parts of which discussed ethics, appeared after his death in 1973. But these works were now far out of the mainstream, which was dominated by the new movements or descendants of them. And British philosophers of the 1950s were dismissive of the school, rejecting their views with brusque arguments that often rested on misrepresentations. Broad and Ewing experienced this attitude most directly, both because they were still active and because in Cambridge it took an especially virulent Wittgensteinian form. Broad avoided philosophical presentations partly because he did not want ‘to spend hours every week in a thick atmosphere of cigarette-smoke, while Wittgenstein punctually went through his hoops, and the faithful as punctually “wondered with a foolish face of praise” ’ (‘A’ 61). Ewing, who did attend and was treated with contempt by Wittgenstein,5 once said ‘I wish they’d read my books’; his obituarist said, ‘It is a hard fact that the majority of philosophers placed little value on his work’.6 In 1956 Broad commented ruefully, ‘though philosophies are never refuted, they rapidly go out of fashion, and the kind of philosophy which I have practised has become antiquated without having yet acquired the interest of a collector’s piece’ (‘R’ 830). The dismissiveness continued in the 1960s. That decade saw a trio of histories of twentieth-century moral philosophy, all focussed on metaethics and crediting Moore, inaccurately, with having revolutionized the subject with his defence of nonnaturalism in Principia.7 But they did not see Moore’s view as defensible; they thought it had deep flaws that later approaches such as emotivism or neo-naturalism would try to overcome. It had set the agenda for twentieth-century ethics, but by showing what an acceptable view cannot be.

4

5 Lacey, Life of Hart, pp. 117–18, 115. Edmonds and Edinow, Wittgenstein’s Poker, pp. 67–8. Grice, ‘Alfred Cyril Ewing’, pp. 500–1. 7 Mary Warnock, Ethics Since 1900 (1960); G.J. Warnock, Contemporary Moral Philosophy (1970); Hudson, Modern Moral Philosophy (1970). 6

6

british ethical theorists from sidgwick to ewing

In the 1970s and 1980s interest returned to normative ethics, but still with little attention to our school except perhaps to Sidgwick. As time has passed, however, the relevance to current work of, for example, Moore on what is good or Prichard and Ross on duty has been more noticed and references to them have become more frequent; there has also been a revival of non-naturalist metaethical views not far from theirs. This increasing interest makes, I hope, a comprehensive survey of their ideas now timely. If the school shared important assumptions, a natural question is how far this is because later members were influenced by earlier ones and adopted their views. It is not easy to say, partly because they did not cite others’ work as often as philosophers do today and partly because sometimes thinkers reason independently to similar conclusions. Here a relevant example is Franz Brentano. Moore read his Origin of Our Knowledge of Right and Wrong in translation right after finishing Principia and found in it ‘opinions far more closely resembling my own, than those of any other ethical writer with whom I am acquainted’ (PE xi).8 But Brentano, whose book was originally given as a lecture in Vienna in 1889, was not influenced by any British philosophers; he arrived at his views on his own.9 In addressing the question of influence it is useful to divide the school into two main groups. Four of them—Sidgwick, McTaggart, Moore, and Broad—were educated and spent all or most of their academic careers at Cambridge. Rashdall, Prichard, Carritt, and Ross had the same relationship to Oxford, while Ewing was educated and did his first writing at Oxford but from 1931 taught at Cambridge. There were close personal connections among the Cambridge members, all of whom were at Trinity College. Sidgwick taught both McTaggart and Moore as undergraduates, while McTaggart taught Moore and later Broad. Sidgwick was on the committee that awarded McTaggart a six-year fellowship in 1891. (He is reported to have said of McTaggart’s writing sample on Hegel, ‘I can see that this is nonsense, but what I want to know is whether it is the right kind of nonsense’ (Moore, ‘A’ 21).) He was also on the committee that turned Moore down for a similar fellowship in 1897, but in the following year told the philosopher who succeeded him to make sure Moore won, which he did. It was at McTaggart’s urging that Broad won a similar fellowship, and Broad later was McTaggart’s literary executor, overseeing the posthumous publication of the second volume of The Nature of Existence and writing his two-volume Examination of McTaggart’s Philosophy. Sidgwick, McTaggart, and Moore were all members of the secret Apostles discussion society; though Sidgwick was no longer active in Moore’s day, McTaggart was, and the young don and the precocious undergraduate met often outside lectures.

8

See also Moore, Review of Brentano, Origin of the Knowledge of Right and Wrong. Brentano, Origin of Our Knowledge. This book discusses other British philosophers such as Bain, Bentham, Grote, Hume, and the two Mills, but they are ones whose views Brentano, like Moore, rejected. 9

introduction

7

As an Oxford undergraduate Prichard was in a circle influenced by Rashdall,10 and he later had close contacts with Carritt and Ross. He was Carritt’s undergraduate tutor and for many years an active participant, with Carritt though apparently not with Ross, in a weekly Philosophical Tea that had been initiated by John Cook Wilson and involved short papers followed by discussion; Carritt said he talked philosophy with Prichard nearly once a week during term and corresponded with him on philosophical issues through the university mail.11 Prichard also corresponded with Ross and played golf with him; the two were good friends, and seem, with Carritt and perhaps for a time Ewing, whom Carritt taught as an undergraduate, to have interacted regularly while developing their ethical views. As for philosophical influence, Broad attributed McTaggart’s idiosyncratic version of Idealism to the combination of a youthful passion for Hegel with, among other things, ‘the teaching of Sidgwick and the continual influence of Moore and Russell’ (EHP 75). In ethics Sidgwick’s influence may be reflected in McTaggart’s casual acceptance of non-naturalism, which had been a comparative novelty in Sidgwick, and in his consequentialism and commitment to the measurement of value; his perfectionist theory of the good, however, departed from Sidgwick.12 Moore reported that as a student he was not attracted by Sidgwick’s personality and found his lectures dull (‘A’ 16); according to John Maynard Keynes, he thought Sidgwick a ‘wicked edifactious person’.13 But Moore allowed that he ‘gained a good deal’ from Sidgwick’s published works, ‘especially, of course, his Methods of Ethics’, (‘A’ 16), and there are important similarities between the two men’s views, both in metaethics and in their belief that though the correct moral principle is act-consequentialist, in everyday life we should follow simpler common-sense rules; clearly some ideas were transmitted. Moore said his greatest undergraduate influence was McTaggart (‘A’ 18–19), but apart from a brief conversion to Idealism he was most impressed by McTaggart’s insistence on clarity, which was shared by Sidgwick and other Apostles. Moore’s account of what is good was perfectionist like McTaggart’s but again it is hard to assess influence; though both placed high value on personal love, for example, they had very different views of what love is. The final Cambridge figure, Broad, named the dominant influences in his undergraduate days as Russell and Moore, the latter partly through Principia and despite his not then being in Cambridge; he was also influenced by McTaggart, though again more by his method than by his doctrines (‘A’ 49–50). He greatly admired Sidgwick, devoting by far the longest chapter of Five Types to him and calling his Methods of Ethics ‘on the whole the best treatise on moral theory that has ever been written’ (FT 143). 11 Matheson, Life of Rashdall, p. 54. Carritt, ‘Professor H.A. Prichard’, p. 146. In a book on McTaggart, P.T. Geach dismissed his ethics as not worth discussing because it was influenced by Moore’s PE, which he thought ‘a profoundly confused book’ (Truth, Love and Immortality, pp. 174–5). But the claim about influence here is dubious: McTaggart was defending the independence of ‘ought’ from ‘is’ and a version of ideal consequentialism before PE, for example in SHC of 1901. 13 Keynes, Letter to Strachey, quoted in Harrod, Life of Keynes, p. 114. 10 12

8

british ethical theorists from sidgwick to ewing

Rashdall’s role in the Oxford group is hard to assess, because the later members all rejected his consequentialism. But when Prichard discussed that view in ‘Mistake’ he took Rashdall rather than Sidgwick or Moore as its chief representative (MW 9), while Carritt called The Theory of Good and Evil one of the two works outside ‘the well-known classics’ he was most influenced by (EPT vi). The larger influence on Prichard was Cook Wilson and his philosophical realism, but Carritt reported that whereas Cook Wilson did not think this view required any change in moral philosophy, Prichard did and for that reason concentrated on the subject.14 His defence in ‘Mistake’ of a non-Kantian deontology was largely original, coming as it did when consequentialism was the dominant philosophical view, and he was also the main influence on Carritt and Ross. Many and even most of the views the three shared— about prima facie duties, the independence of rightness from motives, instrumental goodness, and more—were first proposed by Prichard; though one of the other two may have stated them more clearly, they derived ultimately from him. Carritt and Ross readily acknowledged their dependence on Prichard (TM vi, EPT v; RG v), and it was also recognized in Oxford; thus Ayer thought Prichard the most influential Oxford philosopher of the 1920s and 1930s, called Carritt ‘philosophically a paler Prichard’, and said Ross’s books ‘took a position similar to that of Prichard’.15 What about influences between the universities? There was, first, some mutual hostility. Sidgwick wrote sharply critical reviews of works on ethics by Bradley and Green (EEM 185–9, 193–4, 247–58; GSM 1–131) and Bradley responded with a pamphlet attacking Sidgwick’s Methods.16 McTaggart said that on meeting Bradley he felt ‘as if a Platonic Idea had entered the room’ (Moore, ‘A’ 22), but his later Idealist views were very different from Bradley’s, as was his approach to ethics. In his earliest days Moore too was a Bradleyan, but by the time of Principia he was criticizing Idealist views in both metaphysics and ethics. Broad did the same, saying Bradley was as inferior to Sidgwick in ethical and philosophical acumen as he was superior to him in literary style (FT 144) and making two brilliantly vitriolic remarks about Green. ‘Even a thoroughly second-rate thinker like T.H. Green, by diffusing a grateful and comforting aroma of “ethical uplift”, has probably made far more undergraduates into prigs than Sidgwick will ever make into philosophers’ (FT 144).17 And of a paper of Prichard’s criticizing Green: Seldom can the floor have been more thoroughly wiped with the remains of one who was at one time commonly regarded as a great thinker and who still enjoys a considerable reputation

15 Carritt, ‘Prichard: Personal Recollections’, p. 147. Ayer, Part of My Life, pp. 77, 95, 308. Bradley, ‘Mr. Sidgwick’s Hedonism’. 17 Broad was probably responding to an 1884 incident when the economist Alfred Marshall, in an internal Cambridge debate with Sidgwick, contrasted the hundred men who, ignoring examinations, hung on Green’s lips to learn the truth about human life with the handful of exam-takers taking notes from Sidgwick (Sidgwick, M 394). 14 16

introduction

9

in some circles. A large part of the lectures is occupied with disentangling the strands of clotted masses of verbiage, in which inconsistency and nonsense are concealed by ambiguity.18

From the other direction Prichard and Joseph vehemently opposed the use in philosophy of formal methods, especially mathematical logic, as promoted in Cambridge by Russell and others; Prichard’s correspondence also contains hostile comments about Moore’s ethics. But there was mutual influence and admiration between some Oxford and Cambridge members of the school. Rashdall dedicated The Theory of Good and Evil to ‘My Teachers Thomas Hill Green and Henry Sidgwick’, by which he meant his two greatest philosophical influences (TGE vi–vii). We can see his aim as to combine Sidgwick’s methodology, in particular his concern for clarity and his explicit commitment to consequentialism and the measurement of value, with a theory of what has value that is perfectionist like Green’s. He admired Sidgwick, who in turn considered Rashdall one of his ablest critics (ME xi–xiii, EEM 45–6). There was also mutual regard between Rashdall and McTaggart, the latter of whom read and commented on Rashdall’s book in draft (TGE ix) and is often cited in it. Moore initially wrote an ungenerous review of The Theory of Good and Evil but later recommended it to readers of his Ethics as the first work on ethics by a living writer they should read,19 while Rashdall thought Principia ‘brilliant’ (E 63n2). In The Right and the Good Ross said his main obligation was to Prichard, but he also mentioned Moore’s writings as ones from which, despite disagreements, he had ‘profited immensely’ (RG v–vi); certainly his conception of intrinsic value was close to Moore’s. Ross likewise admired Broad, whose account of prima facie duty he borrowed in Foundations of Ethics even though it differed from his own in The Right and the Good (FE 51–3, 79–82). Broad in turn wrote warm reviews both of Prichard, ‘a man of immense ability whom I have always regarded as the Oxford Moore’ (CE 14), and of Ross,20 while Ewing wrote extensively and respectfully of all three. It seems that whereas early members worked to some extent independently, later ones, while not quite seeing themselves as a distinctive school, recognized their commonalities and applauded and shaped each other’s work. Who were these philosophers? Before examining their ideas let us look briefly at their lives and characters. Henry Sidgwick (1838–1900), who is the subject of a recent major biography,21 was educated at Rugby, where he was friends with T.H. Green, and then at Cambridge, where he was much influenced by his membership in the Apostles. He later said the society’s Saturday evening debates seemed the most ‘real’ part of his life at Cambridge and called his membership the ‘strongest corporate bond I have known’; it also pointed him toward ‘the life of thought’ (M 34–5). After firsts in mathematics and classics he was elected to a fellowship at Trinity in 1859, but resigned it ten years 18 19 20

Broad, Critical Notice of Prichard, Moral Obligation, p. 557. Moore, Review of TGE; E 254 (in the Williams and Norgate 1912 edition). 21 Broad, Critical Notices of FE and Moral Obligation. Schultz, Henry Sidgwick.

10 british ethical theorists from sidgwick to ewing later because he could no longer subscribe sincerely to the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England as was required. He explained his decision in a pamphlet titled The Ethics of Conformity and Subscription and later defended a similar view about the clergy in a journal article. Rashdall replied to this article, supporting a more relaxed policy largely on the ground that no one takes the words in a religious formula literally; here the utilitarian layman was stricter about truth-telling than the ordained perfectionist.22 Despite his resignation he continued to lecture at Cambridge, and he resumed his fellowship when the law that led him to renounce it was abolished; in 1883 he became Professor of Moral Philosophy. By then The Methods had made him an esteemed figure in philosophy, and he was also connected to the political and religious establishment through his wife Eleanor, whose brother was Arthur Balfour, later Conservative Prime Minister, and his sister, whose husband became Archbishop of Canterbury. But he never enjoyed the more widespread acclaim of his schoolmate Green, whose work he thought less careful than his own and whose success he somewhat resented. In his journal he wrote that a remark about seeing ‘the splendid zeal with which missionaries rush on to teach what they do not know’ ‘represents my relation to T.H.G. and his work’ (M 395). Though he was generally conservative on economic policy and voted Conservative, he was a liberal within the university. He promoted women’s education, first organizing lectures and examinations for women and then with his wife founding Newnham College, of which she was the second Principal and where the two of them lived from 1894. He also campaigned to modernize the Cambridge curriculum, including by abolishing a compulsory examination in Latin and Greek and introducing technical subjects such as engineering, but with only mixed success. His other main non-philosophical activity was the Society for Psychical Research, which he co-founded in 1882 and which sought empirical evidence for life after death by conducting seances and interviewing purported psychics such as Madame Blavatsky. These ‘ghostological’ investigations had a philosophical basis: because he thought only the existence of a God who rewards virtue in the afterlife can avoid a fundamental contradiction in our practical thought, he needed to know whether such a God exists. The later generation found his fussing about religion depressing; Keynes said Sidgwick ‘never did anything but wonder whether Christianity was true and prove that it wasn’t and hope that it was’.23 He was a lively conversationalist; in later years he grew fond of gardens and flowers and ‘used to walk about meditating in [the Newnham] garden, stroking his beard on the underside and holding it up against his mouth, which was a characteristic gesture of his’ (Broad, EHP 60). He suffered from sleeplessness and depression, the latter of which he largely hid from others, and in early 1900 was diagnosed with cancer. In May he gave his final philosophical presentation, a critique of Green’s 22 Sidgwick, Ethics of Conformity and ‘Ethics of Religious Conformity’; Rashdall, ‘Professor Sidgwick on the Ethics of Religious Conformity’. 23 Quoted in Harrod, Life of Keynes, pp. 116–17.

introduction

11

metaphysics to the Oxford Philosophical Society where he was ‘in brilliant form’ (EHP 61), and died in August of that year. Hastings Rashdall (1858–1924) was not only a philosopher but also a historian and a clergyman and theologian; he had three simultaneous careers. After a disappointing second in Greats at Oxford in 1881 he remained there for two years reading philosophy and theology and writing an essay on the medieval universities, for which he won the Chancellor’s prize. He later expanded that essay into his threevolume Universities of Europe in the Middle Ages of 1895, which is a standard historical work and still in print today. After briefly teaching outside Oxford he returned in 1888, as a fellow first of Hertford College and later of his undergraduate college, New. Ordained a priest in 1886, he would preach sermons in Oxford and elsewhere, often on theological subjects, where he had very liberal views. He denied that there will be retributive punishment in the afterlife, said an Anglican clergyman need not believe in the virgin birth, and denied that Jesus ever claimed to be divine. His major theological work was a set of Bampton Lectures on the atonement given in 1915 and published in 1919 as The Idea of Atonement in Christian Theology; he argued that Christ’s life reconciles sinning humanity with God only in that he is an exemplar by knowing whom we can improve our moral lives. When Warden Spooner of New College was asked about Christian Socialists in Oxford, he said there were only Rashdall and himself, ‘and I’m not very much of a Socialist, and Dr Rashdall isn’t very much of a Christian’. But Rashdall was very religiously minded and said that made his position difficult: ‘You see I am on the left wing of the Church and the right wing of the philosophers’.24 In metaphysics he was a ‘personal idealist’, believing reality is entirely spiritual but contains many individual souls rather than one Absolute Spirit; his view here was close to McTaggart’s. From 1885 on he published a series of articles on ethics and by 1897 was trying to expand them into a book. Unfortunately the process took ten years, so The Theory of Good and Evil did not appear until four years after Moore’s Principia, which took a similar ideal consequentialist line. At first Rashdall’s book received considerable attention, but over time Moore’s came to be seen as the canonical presentation of their shared theory even though on many topics Rashdall’s discussion was fuller. He was a lively writer, with a gift for striking examples. He was also a vigorous controversialist, as shown in his aggressive attacks on Bradley and an entertaining discussion of the German thinker Georg Simmel (TGE II 103–6); Joseph attributed his combativeness in part to a chivalrous desire to help those he thought in the minority, such as liberals in the Church.25 He was popular with students studying for exams because he would lay out a case in numbered arguments, but apparently took that trait into everyday life: he was once overheard saying to his wife at the end of a walk, ‘Now thirteenthly, my dear’.26 He was also stereotypically absent-minded, forgetting 24 26

Matheson, Life of Rashdall, p. 78. Blanshard, ‘Autobiography’, p. 29.

25

Matheson, Life of Rashdall, p. 253.

12 british ethical theorists from sidgwick to ewing appointments, inept at sports—he played field hockey with thirty-four other dons and said he was not even in the third eleven—and ignorant about machinery. Informed once that the back tyre of his bicycle was flat, he started to blow up the front one and, when alerted to his mistake, asked, ‘Don’t they communicate?’27 He was an enthusiastic cyclist, for whom ‘one of his ideas of heaven was riding down Boar’s Hill with his feet up and the view of Oxford before him’.28 After being passed over for an Oxford professorship in 1910 he began to spend more time on theological issues and in 1917 accepted a full-time ecclesiastical appointment as Dean of Carlisle. His health began to deteriorate in 1921 and he died in 1924. At birth John McTaggart Ellis McTaggart (1866–1925) had the last name ‘Ellis’, but his family added the second ‘McTaggart’ to secure an inheritance from his maternal uncle. He was precocious, becoming an atheist as a child and reading Kant at thirteen. After earning the only first in Moral Sciences at Cambridge in 1888 he was elected to a six-year Trinity Prize Fellowship in 1891; his dissertation for it was published as Studies in Hegelian Dialectic in 1896 and he became a lecturer at Trinity in 1897. Hegel was long an inspiration and also the subject of Studies in Hegelian Cosmology (1901), A Commentary on Hegel’s Logic (1910), and many articles. But McTaggart’s intellectual character, dedicated to clarity of expression and rigour in argument, was very different from Hegel’s, and Broad and Moore doubted that the interesting views he claimed to find in Hegel were really there. Broad said he ‘produced an extremely lively and fascinating rabbit from the Hegelian hat’, whereas other commentators produced ‘nothing but consumptive and gibbering chimeras’, and his achievement was all the more impressive since ‘the rabbit was, in all probability, never inside the hat, whilst the chimeras perhaps were’ (EHP 75; also Moore, ‘A’ 19). McTaggart found the other British Idealists aside from Bradley annoyingly high-minded, calling them ‘the sort of people who wanted to believe that they ate a good dinner only in order to strengthen themselves to appreciate Dante’ (EHP 79). He himself was an avid drinker and thought every undergraduate should get drunk at least once a year to prove to his tutor he was not a teetotaller. He presented his own metaphysical views, free of Hegelian trappings, in The Nature of Existence and is best known for his argument that time is unreal, first given in Mind in 190829 and distinguishing an A-series of times involving the concepts ‘past’, ‘present’, and ‘future’ and a B-series involving ‘earlier’ and ‘later.’ He thought reality is entirely spiritual, involving a plurality of individual minds each loving one or more others, and love was his highest value. It was reflected in his intense loyalty to institutions, especially his public school, Trinity, and England; he was a fierce nationalist in the First World War and, less admirably, helped secure Russell’s expulsion from Trinity in 1916 for his pacifism. He was gay, and read an influential paper to the Apostles defending homosexual love, under the title ‘Violets or Orange 27 29

Matheson, Life of Rashdall, pp. 61, 81. McTaggart, ‘Unreality of Time’.

28

Carritt, Fifty Years a Don, p. 30.

introduction

13

Blossom?’ When he surprised his friends by returning from a trip to New Zealand with a wife, he told them she shared his interests in metaphysical discussion and schoolboys. Moore called him a ‘very strange and fascinating personality’.30 He had a distinctive crab-like walk, moving sideways and often keeping a wall behind him; some thought he had developed this practice to avoid being kicked by bullies at school.31 He rode a custom-built tricycle around Cambridge, because he had become too fat to manage a bicycle.32 He would entertain students at his home for breakfast or lunch but sometimes became so lost in philosophical thought he forgot to serve any food. Though he was an atheist he strongly supported the Church of England and opposed its disestablishment; he loved ritual and insisted on strict attention to detail in Cambridge ceremonies. A conservative in national politics, he was a liberal inside the university and went beyond Sidgwick in supporting full membership for women. Moore and Broad both praised his writing, the latter calling him a master of English philosophical prose alongside Hobbes, Berkeley, and Hume (EHP 71).33 But his metaphysical system-building was already out of fashion by the first decade of the new century, when Broad said he had many admirers but almost no disciples (‘A’ 50).34 He reached retirement age in 1923 but was still lecturing and writing when he fell ill and died in 1925. At his request, the memorial brass for him in Trinity chapel, which is beside Sidgwick’s, contains no specifically Christian references. After excelling in mathematics and classics H.A. (Harold) Prichard (1871–1947) was elected an Oxford college fellow in 1895. He was a devoted tutor, often extending his students’ one hour per week to two, three, or more and discussing their essays with them line-by-line. The strain this involved contributed to a breakdown in his health that led him to resign his fellowship in 1924; in 1928 he was elected to a Professorship of Moral Philosophy that was less demanding. In ethics he published just two journal articles, ‘Mistake’ in 1912 and one on Aristotle in 1935, and two lectures; in epistemology just Kant’s Theory of Knowledge (1909), described as ‘a very good book about Prichard’s theory of knowledge, but not such a good one about Kant’s’,35 and a handful of articles. As a result the two posthumously published collections of his writings, Moral Obligation and Knowledge and Perception, contained many items that had not before appeared in print. In later years he worked on a book about ethics that Carritt thought would rank with The Methods of Ethics 36 but he never finished it; two partial drafts appear in his Moral Writings as ‘Manuscript on Morals’ and ‘Moral Obligation’. Despite his limited output he was an active and influential philosopher and often conducted philosophical discussions by correspondence. Many of his letters survive, partly because he would ask his

30 32 34 36

Moore, ‘Death of Dr. McTaggart’, p. 271. Geach, Truth, Love and Immortality, p. 12. Also Woolf, Sowing, p. 133. Blanshard, ‘Autobiography’, p. 61.

31 33 35

Geach, Truth, Love and Immortality, p. 10. Also Moore, ‘Death of Dr. McTaggart’, p. 271. Price, ‘Harold Arthur Prichard’, p. 343.

14

british ethical theorists from sidgwick to ewing

correspondents to return his original letter to him with their reply, so he could consult it when replying back to them. Ross said his letters ‘often exhibit the firmness and subtlety of his thought as forcibly as anything that he published’;37 they also show he often changed his mind. Having long held views like those in Ross’s The Right and the Good, he began to see flaws in them after that book was published and to develop an alternative. He was a deep thinker, often giving our school’s distinctive views their most forceful statement, but he could also tie himself in knots about what seem trivialities. Thus he denied that the ground of your obligation to do an act can be the fact that, if you did it, it would have certain properties, arguing that from a hypothetical premise only a hypothetical conclusion can follow; none of Ross, Broad, and Carritt could see the difficulty here.38 He was combative in philosophical debate and had a not undeserved reputation for dogmatism. In 1933 a committee he was on decided that none of the candidates who had written the examinations for the John Locke Prize, including the young Austin and Ayer, deserved to win it. Ayer attributed this decision largely to Prichard, saying, ‘As quite often happens, even with good philosophers, he could see no merit in views that differed radically from his own’. Ayer also called the general tone of Oxford philosophy in the period of Prichard’s dominance ‘surly and unadventurous’ and Prichard himself ‘philosophically gifted, but narrow and dogmatic’.39 But Austin, despite not sharing Prichard’s views, admired ‘the single-mindedness and tautness of his arguments, and the ferocity and the total lack of respect for great names with which Prichard rejected obscurity and lack of consistency in philosophy, ancient and modern’.40 H.H. Price’s obituary of him says, ‘The ruling passion of his life was the desire to discover the truth about ultimate questions’,41 and while one expression of that can be intellectual modesty and an openness to differing opinions, another can be passionate commitment to what you think you have discovered is true. Prichard spoke in short staccato sentences, and his favourite retorts included ‘I don’t know what is true, but whatever is, that isn’t’ and ‘Now you are wrapping it up in cotton-wool’.42 His prose was direct and free of jargon but often hard to read because of the density of its argumentation. He was short, wiry, and athletic and had played tennis for Oxford as an undergraduate. He was a lifelong and enthusiastic golfer, and his golf game was said to be like his philosophy: ‘his shots were sometimes short, but they were always straight’.43 He reached retirement age from his Professorship in 1937 and died ten years later. G.E. (George Edward, though he hated those names) Moore (1873–1958) arrived in Cambridge in 1892 and in his first year met Russell, who with McTaggart’s support 37 Ross, ‘Preface’ to Prichard, Knowledge and Perception; also Price, Critical Notice of Knowledge and Perception, pp. 103–4. 38 Prichard, letters to Ross of 10.5.40 and to Broad of 4.3.43; Carritt, Fifty Years a Don, pp. 27–8. 39 40 Ayer, Part of My Life, pp. 152, 77–8. Berlin, ‘Austin and the Early Beginnings’, p. 2. 41 Price, ‘Harold Arthur Prichard’, p. 332. 42 Price, ‘Harold Arthur Prichard’, p. 333; Carritt, Fifty Years a Don, p. 26. 43 Price, ‘Harold Arthur Prichard’, p. 332.

introduction

15

had him elected to the Apostles and persuaded him to switch from classics to philosophy. To Russell he ‘fulfilled my ideal of genius. He was in those days beautiful and slim, with a look almost of inspiration, and with an intellect as deeply passionate as Spinoza’s. He had a kind of exquisite purity.’44 He soon became the dominant figure among the Apostles, as Sidgwick had been before. After an undergraduate first he applied in 1897 and 1898 for the same Prize Fellowship McTaggart had had, submitting two versions of a dissertation on Kant’s ethics. It was sent to referees and their reports on it survive; those by Sidgwick and Bosanquet are especially interesting, since they found similar strengths and weaknesses but differed in which they emphasized. A little disappointed by the dissertation, Sidgwick said its merit ‘seems to lie in promise rather than performance: but I judge it to be very promising’. But Bosanquet said that while promise may suffice for an undergraduate first, a fellowship candidate should have begun to turn his promise into performance, which Moore had not. Bosanquet objected especially to a part of the dissertation arguing that the objects of thought are independent of our thought and unaffected by it; he thought that view had been refuted by Idealism. He concluded, ‘if [this piece] had been sent me for review by “Mind” . . . I should have treated it respectfully as a brilliant essay by a very able writer, but should have endeavoured to point out that its positive stand-point and consequently its treatment of the subject were hopelessly inadequate’. Moore nonetheless won the Fellowship and in a way got back at Bosanquet. He cut the offending part out of the dissertation and submitted it (of course) to Mind, where it was published in 1899 as ‘The Nature of Judgment’.45 His fellowship ran for six years, and though he later accused himself of laziness in this period (‘A’ 24–5), he published numerous papers and reviews, wrote the lectures later published as The Elements of Ethics, and then revised and expanded them into Principia. This book was rapturously received by the younger Apostles who later formed the Bloomsbury group. Lytton Strachey told Moore his book had ‘wrecked and shattered all writers on Ethics from Aristotle and Christ to Herbert Spencer and Mr Bradley . . . I date from Oct. 1903 the beginning of the Age of Reason’.46 Keynes called it ‘exciting, exhilarating, the beginning of a renaissance, the opening of a new heaven on a new earth’, and said Moore’s account of the good became the group’s ‘religion’. Looking back, he thought they had ignored Moore’s concern for the effects of acts on other people, instead pursuing the good just in their private lives. But through the Bloomsbury circle Principia influenced much of English art and culture.47 In 1904 Moore applied for a follow-up Research Fellowship at Trinity but was turned down, in part because of another negative report from Bosanquet. He then lived outside Cambridge for

44

Russell, Autobiography, vol. 1, p. 64. On the dissertation and referees’ reports see Regan, Bloomsbury’s Prophet, pp. 68–70, 99–103; the documents are in The Moore Papers, Trinity College Library, Cambridge. 46 Letter from Strachey to Moore of 11.10.1903, The Moore Papers, Cambridge University Library. 47 Keynes, ‘My Early Beliefs’, pp. 52–5. 45

16

british ethical theorists from sidgwick to ewing

seven years on a private income before returning as a lecturer in 1911; given his stature in twentieth-century philosophy, it is startling to learn that he did not have a permanent academic post until he was thirty-eight. Once in it, however, he was a dedicated lecturer, taking no sabbaticals in the next twenty-eight years and writing all his lectures afresh each year. In 1925 he became Professor of Philosophy and from 1921 to 1944 was the editor of Mind, a job he handled on his own; he confessed later that he sometimes accepted an article from a famous writer despite thinking its quality below what he would require from someone unknown (‘A’ 36). Both his philosophy and his writing changed from his earlier to his later years. Principia had great confidence in its judgements and, reflecting that, was brisk and forceful in its prose, but his later style, with its labourious repetitions and qualifications, was that of a man for whom deciding had become difficult. R.B. Braithwaite said that although Moore’s principal interest from around 1910 on was the philosophy of perception, he never published a book on it because ‘he saw the reasons against any view so clearly that he could never make up his mind which was on the whole the most defensible’.48 There are many testimonials to his character. Leonard Woolf thought him the only great man he had met or known, saying he ‘resembled Socrates in possessing a profound simplicity’,49 and he was often called innocent or childlike, for example by Wittgenstein.50 His modesty shines through his ‘Autobiography’ and is reflected in his travelling to Norway in 1914 to act in effect as secretary to Wittgenstein, whom he thought cleverer and more profound than himself (‘A’ 33), and in his taking and then publishing notes on Wittgenstein’s lectures of 1930–3.51 Many noted what Braithwaite called his ‘single-minded and passionate devotion to the search for truth’.52 He was a constant pipe-smoker, despite numerous efforts to quit, and entertained his friends by singing Schubert’s and other Lieder while accompanying himself on the piano. He reached the retirement age for his Chair in 1939 and spent 1940–4 in the United States, away from the dangers of war. When he returned to Cambridge he was too ill to attend philosophy papers or appear often in public; he died in 1958 just before his eighty-fifth birthday. E.F. (Edgar) Carritt (1876–1964) was a fellow of University College, Oxford from 1899 until after the Second World War; his 1960 typescript memoir Fifty Years a Don is in the college library. As an undergraduate at Hertford College he dined opposite a portrait of Hobbes, and ‘the study of his face convinced me that mischief, not vagueness, produced his famous ambiguity: “It is a Law of Nature that Men keep their covenants made” ’.53 He modestly attributed his first in Greats to the good luck of getting a question on Plato’s aesthetics, which he had been studying, and aesthetics remained a major philosophical interest. His first publication was an article on the

48 50 52

Braithwaite, ‘George Edward Moore’, p. 298. Malcolm, Wittgenstein: A Memoir, p. 80. Braithwaite, ‘George Edward Moore’, p. 305.

49 51 53

Woolf, Sowing, pp. 131, 137. Moore, ‘Wittgenstein’s Lectures in 1930–33’. Carritt, Fifty Years a Don, p. 6.

introduction

17

sublime,54 and he later wrote The Theory of Beauty (1914), What is Beauty? (1932), and An Introduction to Aesthetics (1949); he also gave what Bradley told him were the first lectures at Oxford on aesthetics not about Aristotle’s Poetics. His aesthetic views were influenced—some thought overly so—by Benedetto Croce’s and took a similar ‘expressive’ line. After taking up his fellowship he attended the Philosophical Tea, where ‘perhaps the most stimulating dialectics were those between Prichard, Joseph, and Professor J.A. Smith, the first a convert to Realism, the last an Idealist and Joseph a cross-bencher’. He ‘sometimes thought the controversies of Prichard and Joseph—for instance on the meaning of “whole” or “same”—would have made a popular music-hall turn’.55 He was known for an extremely compressed prose style; in a letter to Ross, Prichard said, ‘I expect I have carried brevity beyond even the extent to which Carritt carries it’.56 Brand Blanshard thought Carritt’s writing was influenced by the idea that in a perfect work of art there are no excrescences and everything contributes to the whole; he found the result at times elliptical and even crabbed.57 Carritt’s obituarist said his counterexamples were often devastating, ‘but many readers will fail to notice it because he does not waste unnecessary words hammering a nail home. For him it was enough to tap it once in the right place. If he could do so with light irony, so much the better.’58 Certainly his ethical writings often make novel points so briskly one can easily miss them. In politics he was a socialist, according to Blanshard ‘on moral grounds’, and the most left-wing member of the school. He was not a communist but his wife and five sons were; one became an editor of The Daily Worker and another died in the Spanish Civil War. Carritt participated in the ‘pink lunch’, a gathering of left-wing dons at his college that heard visiting speakers. He also gave the first Oxford lectures on dialectical materialism; an older philosopher asked him why he had given his lectures so queer a title, which no one had heard of. But his interest in this topic was characteristic. He thought that just as a true aesthetic theory should not change our particular judgements of beauty, so philosophy in general should not affect our conduct—and Marx’s metaphysical theory claimed to do so. He was a fine teacher and also physically energetic. As an undergraduate he rowed stroke for his college boat club and he continued to enjoy exercise throughout his life. When visiting with Blanshard for a year at the University of Michigan he ran around the block every morning before breakfast, and when the two came to a river on a walk would strip and jump in. To Blanshard he was ‘a new type of man. Comfort, clothes, and money meant little to him; beauty in art and nature meant much; and duty meant most of all.’ He continued writing well past his retirement and died in 1964. Alongside his work in ethics, W.D. (later Sir David) Ross (1877–1971) was also and even primarily a scholar of ancient philosophy, as distinguished as any in the 54 56 58

Carritt, ‘The Sublime’. Prichard, Letter to Ross of 11.12.36. Raphael, ‘Edgar Frederick Carritt’, p. 447.

55 57

Carritt, Fifty Years a Don, p. 26. Blanshard, ‘Autobiography’, p. 72.

18

british ethical theorists from sidgwick to ewing

twentieth century. Elected a fellow of Oriel College in 1902, he soon after became editor, at first jointly and then alone, of the Oxford translations of Aristotle, which appeared between 1908 and 1931. He himself contributed translations of the Metaphysics and Nicomachean Ethics, arguably the two most important Aristotelian works, and gave editorial guidance to the others. He prepared Oxford Classical Texts of six works of Aristotle and did complete editions, with introductions and commentaries, of five; his Aristotle of 1923 is a standard work, though more expository than critical, and Plato’s Theory of Ideas appeared in 1951. In a hugely successful academic career he was Provost of Oriel from 1929, president of the British Academy from 1936 to 1940, and vice-chancellor of Oxford University from 1941 to 1944. While he was Academy president many Jewish scholars fled central Europe; he did much to help them, both officially and unofficially, and welcomed several into his home. During the First World War he worked in the Ministry of Munitions and so impressed officials that he served on a succession of government boards over the next thirty years, often concerned with setting minimum or other wages. From 1947 to 1949 he chaired a Royal Commission on the Press, which recommended the creation of a Press Council that then governed the industry until the phone-hacking scandal of 2011. Largely because of his government work he was made OBE in 1918 and knighted in 1938. From early in his career he lectured on ethics, and when the Professor of Moral Philosophy fell ill in 1923 he was chosen to fill in as Deputy, which he did until 1928. It was during this period that he did his main work in ethics, publishing a series of journal articles that led to The Right and the Good. Raised a Scots Presbyterian, Ross was taciturn and even severe in character, disliking idle conversation and hating gossip; Ayer complained that he turned the Oriel Senior Common Room into ‘a stronghold of puritanism’.59 He did, however, enjoy playing charades. He was extremely conscientious. When the Moral Philosophy Chair fell open in 1928 he did not let his name stand; among his reasons were that a Deputy may be unfairly favoured by a selection committee and therefore should not in general stand, and that Prichard was a better moral philosopher than he and a better philosopher generally.60 In the event Prichard was selected. Ross’s many successes rested on talents for hard work, quick decision, and concentration on the task at hand, the latter allowing him to move easily from one task to another. A former student described visiting him at Oriel and finding him deep in writing the lectures that became Foundations of Ethics. The student was welcomed and his issues dealt with quickly and courteously, but as he left the room he could hear Ross’s pen racing across the paper again before he reached the door.61 In all his work, from his Aristotle commentaries to the government boards, Ross showed sound judgement and good sense. It was said of him, ‘He is not only an Aristotelian scholar, but he also has an Aristotelian frame of mind—moderate, critical, balanced, thorough, and above all, 59 61

Ayer, Part of My Life, p. 308. Blanshard, ‘Autobiography’, p. 60.

60

Clark, ‘Sir David Ross’, p. 534.

introduction

19

judicious’.62 A tall man, he held himself with natural dignity and played golf and tennis regularly. After enjoying robust good health he died in 1971, aged 94. As a Cambridge undergraduate C.D. (Charlie Dunbar) Broad (1887–1971) first studied natural science but in his last two years switched to philosophy. After an especially high first, he in 1911 won the six-year fellowship both McTaggart and Moore had had; his dissertation for it was published as Perception, Physics, and Reality in 1914. Before the fellowship was announced, however, he had accepted a teaching job at St Andrews. He decided to keep both positions, teaching most of the year in Scotland and spending a few months each summer at Trinity. This gave him two incomes, and with his Trinity funds ‘began that course of saving and investment which has been one of my main sources of interest and satisfaction in life’ (‘A’ 52). During the First World War he avoided military service, of which he was terrified, by doing chemistry research in Scotland for the Ministry of Munitions, and in 1922 returned to Trinity to replace McTaggart as lecturer in philosophy. He would write his lectures out in full in advance, and while lecturing read each sentence out twice; his lectures were the origin of all his later books, including Scientific Thought (1923), The Mind and Its Place in Nature (1925), Five Types (1930), and the twovolume Examination of McTaggart’s Philosophy (1933 and 1938). In 1933 he was appointed to the Professorship Sidgwick had held, but did not enjoy the position. It involved teaching graduate students, whom he liked less and the value of whose research he questioned; in addition, he ‘no longer believed in the importance of philosophy’ and ‘took little interest in its later developments’, thinking he had ‘shot [his] bolt’ (‘A’ 60–1). Yet he continued to produce incisive papers and reviews. From 1920 on he belonged to Sidgwick’s Society for Psychical Research, serving as its President in 1935–6. He did not have Sidgwick’s motive for involvement, hoping in fact that there is no afterlife, but thought the issue important enough to be tackled with the best, empirical, methods. He was utterly unathletic, unable to dance, swim, play any sport, or drive a car; his main outside interest was building elaborate model railways, which he did in some friends’ garden while a lecturer in Cambridge. He lived in rooms in Trinity—the same ones Newton had had—and ate in college. He was gay, though less flamboyantly so than McTaggart, and ended his ‘Autobiography’ by mentioning his ability ‘to make friends with the kind of young men whom I like and admire, despite great disparity in age’, saying he ‘derived more happiness from this than from any one other source’ (‘A’ 68). In politics he mixed distrust of democracy, Plato’s objections to which he thought conclusive, with distrust of a pure market economy, for destroying natural beauty and exploiting wage earners. By the 1950s, however, he thought the political balance had swung too far toward labour and was voting Conservative: ‘I cannot imagine myself at home in that collection of bone-heads unequally yoked to eggheads and decorated with a broad lunatic fringe,

62

Blanshard, ‘Autobiography, pp. 60–1. The quoted remark is from A.K. Stout.

20

british ethical theorists from sidgwick to ewing