Braided Waters: Environment and Society in Molokai, Hawaii 9780520970656

Braided Waters sheds new light on the relationship between environment and society by charting the history of Hawaii’s M

221 16 5MB

English Pages 312 [280] Year 2018

Contents

List of Illustrations

List of Maps and Tables

Foreword

Introduction: Outer Island, In Between

1. Wet and Dry: The Polynesian Period, 1000–1778

2. Traffick and Taboo: Trade, Biological Exchange, and Law in the Making of a New Pacific World, 1778–1848

3. A Good Land: Molokai aft er the Mahele, 1845–1869

4. The Bonanza Horizon: Molokai in the Sugar Era, 1870–1893

5. A Bigger, Better Hawai‘i: Making an American Molokai, 1893–1957

6. From Lonely Isle to Friendly Isle: Economic Struggles in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries and the Future of “the Most Hawaiian Island”

Conclusion: Two Experiences of Settlement

Appendix

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Wade Graham

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

The publisher and the University of California Press Foundation gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Richard and Harriett Gold Endowment Fund in Arts and Humanities.

Braided Waters

WESTERN HISTORIES William Deverell, series editor Published for the Huntingon–USC Institute on California and the West by University of California Press. 1. The Father of All: The de la Guerra Family, Power, and Patriarchy in Mexican California, by Louise Pubols 2. Alta California: Peoples in Motion, Identities in Formation, edited by Steven W. Hackel 3. American Heathens: Religion, Race, and Reconstruction in California, by Joshua Paddison 4. Blue Sky Metropolis: The Aerospace Century in Southern California, edited by Peter J. Westwick 5. Post-Ghetto: Reimagining South Los Angeles, edited by Josh Sides 6. Where Minds and Matters Meet: Technology in California and the West, edited by Volker Janssen 7. A Squatter’s Republic: Land and the Politics of Monopoly in California, 1850–1900, by Tamara Venit Shelton 8. Heavy Ground: William Mulholland and the St. Francis Dam Disaster, by Norris Hundley Jr. and Donald C. Jackson 9. The Other California: Land, Identity, and Politics on the Mexican Borderlands, by Verónica Castillo-Muñoz 10. The Worlds of Junípero Serra: Historical Contexts and Cultural Representations, edited by Steven W. Hackel 11. Braided Waters: Environment and Society in Molokai, Hawai‘i, by Wade Graham

Braided Waters Environment and Society in Molokai, Hawai‘i

Wade Graham

UNIVERSIT Y OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2018 by Wade Graham

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Graham, Wade, author. | Worster, Donald, 1941- writer of foreword. Title: Braided waters : environment and society in Molokai, Hawaii / Wade Graham. Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2019] | Series: Western histories ; 11 | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Identifiers: lccn 2018025160 (print) | lccn 2018032368 (ebook) | isbn 9780520970656 (ebook) | isbn 9780520298590 (cloth : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Human ecology—Hawaii—Molokai. | Political ecology— Hawaii—Molokai. | Nature—Effect of human beings on—Hawaii— Molokai—History. | Water-supply—Political aspects—Hawaii—Molokai. | Molokai (Hawaii)—History. Classification: lcc gf504.h3 (ebook) | lcc gf504.h3 g73 2019 (print) | ddc 304.20969/24—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018025160 Manufactured in the United States of America 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

19

18

contents

List of Illustrations List of Maps and Tables Foreword by Donald Worster Introduction: Outer Island, In Between

vii ix xi 1

1. Wet and Dry: The Polynesian Period, 1000–1778

12

2. Traffick and Taboo: Trade, Biological Exchange, and Law in the Making of a New Pacific World, 1778–1848

44

3. A Good Land: Molokai after the Mahele, 1845–1869

69

4. The Bonanza Horizon: Molokai in the Sugar Era, 1870–1893

99

5. A Bigger, Better Hawai‘i: Making an American Molokai, 1893–1957

126

6. From Lonely Isle to Friendly Isle: Economic Struggles in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries and the Future of “the Most Hawaiian Island”

155

Conclusion: Two Experiences of Settlement Appendix Notes Bibliography Index

194 199 205 235 253

illustrations

1. Fishpond in East Molokai 24 2. East Molokai 48 3. Kaluaaha Ma Molokai engraving of Kalua‘aha in Molokai, created between 1833 and 1843 62 4. Poi making outdoors at Halawa, Molokai, 1888 73 5. Group of Hawaiians on Molokai before 1899 74 6. First leper settlement at Kalawao, looking eastward 101 7. Father Damien with the Kalawao Girls’ Choir at Kalaupapa, circa 1878 102 8. R. W. Meyer Sugar Mill, engine and boiler house, circa 1881 115 9. Pa‘u riders, Kalaupapa, July 4, 1907 127 10. Molokai Ranch Headquarters, 1913 163 11. Inter-Island Airways Sikorsky S-43 in flight past windward Molokai, circa 1935–1940 177 12. Dirt road along Hawaiian homesteads, Ho‘olehua, 1973 181

vii

map s and ta bl es

MAPS

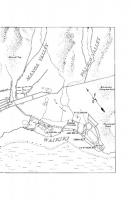

1. Location of Molokai and the Hawaiian Islands in the Pacific Basin 2 2. Map from 1901 showing locations of ahupua‘a land divisions and fishponds 26 3. Molokai map from 1897 prepared for the 1906 Report of the Governor of the Territory of Hawaii to the Secretary of the Interior 80 4. Molokai land use 174 TA B L E S

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Molokai ahupua’a 199 Molokai land transactions, pre-Mahele to 1859 202 Molokai land transactions, 1860–1869 202 Molokai land transactions, 1870–1889 203 Major landholdings on Molokai, 1984 204

ix

foreword Donald Worster

Like the celebrated Galápagos Islands of the South Pacific but far more romantically lush, green, and hospitable to Homo sapiens, the Hawaiian Islands offer an extraordinary window into the planet’s evolution. But Darwin never saw Hawai‘i. After traveling to the Galápagos in the 1830s, he published his masterwork, On the Origin of Species (1859), which launched the science of evolution, the foundational truth of modernity. Evolution tells us a true, if sometimes disturbing, story of species emerging out of competition and through an ancient, merciless struggle for survival. In the Galápagos that story was revealed to Darwin through the mute testimony of finches, tortoises, and swimming iguanas. But if he had gone to Hawai‘i, the story would have become far more complicated. Evolution in Hawai‘i would have to include cycles of people succeeding other people, a process of social and cultural evolution. If Darwin had gone to Hawai‘i instead of the Galápagos, he might have found things too confusing and tangled. He needed a simpler, less-peopled place to suggest questions and provoke a revolutionary theory about the natural order. To understand the more complex intertwining of ecological and social evolution would require the combined efforts of scientists, anthropologists, economists, philosophers, and historians—and even more than Darwinism, that multilayered perspective would lead us beyond science and into questions of ethics and value. We could not avoid asking who or what should triumph, and who or what should lose? This book about Hawai‘i’s history, because of its combined natural and social dimensions, leads us into that maelstrom. Always in that place, and in books about it, we become embroiled in human controversy.

xi

xii

foreword

Some four decades ago, I discovered the Hawaiian Islands—not long after I had discovered Charles Darwin so that henceforth the two discoveries would be firmly linked in my mind. After living there nearly a decade, I was forced to leave the islands and escape their devastating mold spores, which for me were deadly allergens blowing down from the rainy highlands on the soft trade winds—a threat I was not naturally well adapted to meet. As one of nature’s “unfit,” I abandoned my ambition to write about Hawai‘i’s complicated evolution through deep time. Now I look back with fond memories on that ravishingly beautiful place, mixed with darker memories of hospital emergency wards but also with a sense of missed opportunity. Someone else, I have had to tell myself, must tell that amazing history of competing waves of migrating plants, animals, microorganisms, and peoples of diverse races and cultures. Now Hawai‘i has found its environmental historian in Wade Graham, an exceptionally talented writer and scholar. He has carefully read the archives, gathered statistics, tracked down travelers’ reports, learned island natural history, and actually lived in the place long enough to know it like a native. His book is rich in theory and insight, and it should stand for a long time as an exceptional piece of history—a provocative tale of evolution. Thousands of miles of Pacific Ocean separate the Hawaiian archipelago from the big continental landmasses so that the first plants had to arrive more or less accidentally by ocean and wind currents and flying birds. Over a period of 27.5 million years, one plant species made it here every 100,000 years. Radiant evolution occurred among those early migrants, until the islands became home to eleven hundred different kinds of plants, along with many species of endemic animals—a lush Garden of Eden but one without a Creator. The first Adams and Eves of this place showed up about one thousand years ago, arriving in Polynesian canoes loaded with still more plants and animals and introducing an all-too human urge to burn forests, plant taro, create artificial fishponds, and kill birds to make brightly hued feather cloaks. Their descendants still believe that they are the “rightful” owners of the place—the kama‘aina, or children of the land, who supposedly have lived for centuries in “harmony” with the rest of nature. For good reason, Graham does not succumb to such a myth, charming though it may be and worthy of some respect. He has gathered plenty of evidence that the First Hawaiians committed ecological destruction, suffered from overpopulation, practiced violence, endured class stratification, and witnessed land monopolization that spoil any notion of idyllic harmony. Like the emperors of Rome and China, like the Medici bankers of Florence, the power elite of Polynesian Hawai‘i could be ruthless, greedy, and cruel, yet they were accepted meekly by those they dominated. Hawai‘i’s archaic state must tell volumes about the course of social evolution. No societies, we learn from comparative study, are immune to internal competition for natural resources. Some may try to limit that competition, but they never

foreword

xiii

stop it completely or achieve a perfect symbiosis between people and the rest of nature. Such a conclusion I take to be the main argument of this book. Graham goes on to theorize that the “thickness” or “thinness” of environments in terms of water, soil, and other resources is a strongly determinative force behind structures of power. Hawai‘i evolved toward “social bigness” because it was richly endowed with natural resources but not so endowed for every valley or shore. In some places “bigness” proved difficult to create or sustain. A rich endowment always brought a higher population density, and eventually, it brought a concentration of power and wealth among those most adept at competition. Thus, Hawai‘i’s native leaders, the ali‘i, managed by the mid-nineteenth century to gain control over some four million acres, including the best lands for accumulating riches. That initial concentration of “bigness” owed little to other later invaders coming from Europe, Africa, America, or Asia. Graham focuses most of his attention on Molokai, a small island situated in the middle of the archipelago, where the habitat was comparatively “thin,” providing only a few small patches of high productivity amid a generally fragmented and stingy set of environments. The Hawaiian elite, therefore, tended to pass over poor Molokai, for it lacked much scope for their aggrandizement, and so did the white settlers who came in the nineteenth century with dreams of religious missions along with sugar, pineapple, and coffee plantations. Molokai proved unsuitable for sugar growing on a modern scale and instead became a primitive grazing frontier for cattle, sheep, and goats. Then there was that small thumb of lava rock jutting below towering sea cliffs, a tiny place named Kalaupapa, which offered a quarantine site for lepers. The rich, powerful, and healthy never found much to attract them there. In part the excellence of this book comes from the author’s skill in moving back and forth among the various scales of history, from the local to the global. He steps back from Molokai to take in the whole island chain and then the entire Pacific Ocean and then the ever-tightening global web of commerce so that what was isolated and local can take on transoceanic and international significance. This mixing of scales is one of environmental history’s greatest contributions to the writing of history, and Graham is masterful in weaving those scales into a single, compelling narrative. The white Americans who led a second major human invasion of the Hawaiian Islands came full of Protestant piety and, paradoxically, smug social Darwinist beliefs. They saw themselves as the “fittest,” morally and intellectually, in any competition. By the 1890s they had managed to overthrow the native monarchy and even get the islands annexed to the United States. After those triumphs, they proved as remorseless—and even brutal—as anyone in history. In their own eyes, and especially in the eyes of the sugar planters, they had to become the “keystone species”; that is, the arbiters of good land use, the rightful heirs of plenty, and the people best equipped to create and maintain a new and better ecology.

xiv

foreword

One of the most ardent of their agents was Harold Lyon, a plant pathologist employed by the Hawaiian Sugar Planters’ Association. Enthusiastically, he served both their self-interest and his own by promoting the wholesale importation of new tree varieties from every part of the world and releasing them onto the islands to create a new and better forest. These imported plants he would pit against each other, letting them “work out their own salvation.” The result, he hoped, would be a tougher, more resilient forest that would stop erosion and runoff and save precipitation that the planters needed for irrigation projects. Lyon’s science was based on the theory of evolution, but for him evolution became a “law” that humans must obey. Islanders should take competitive nature as a model. In focusing on one prominent scientist, Graham moves downscale to illustrate the ideology that many white Americans brought to the islands and tried to implement in the landscape. Evolutionary science and environmental history can, and indeed should, work together to illuminate the past and ground us in reality, not in myth or ideology. But the laws of nature should not dictate how we write history. There is also the matter of what ought to be. Humans, unlike the trees and birds that arrived in the islands without any volition, did a lot of thinking about what separates “right” from “wrong” and distinguishes “ought” from “is.” They came up with competing ethical standards or ideals, primarily aimed at their relations with other humans but also now and then promulgated as guides to managing nature. And writing about that struggle for ethics makes history a moral discipline as much as a scientific one. Wisely, the author does not take a strongly partisan position in current Hawaiian politics of land claims and counterclaims. On the contrary, he skewers all those who cannot see their own moral shortcomings, including not only Lyon but also a few prominent Hawaiian nationalists of our day who want all whites simply to go “home” and leave the islands under their native rule. Molokai, among the most “backward” of the islands economically, has in recent decades become a place of refuge for those nationalists who want to restore the old ways, which supposedly would remedy all perceived injustices. Graham’s book offers a stern antidote to such nostalgic and uninformed politics, which ignores the moral failings of the precontact past and the universal workings of evolution found in all nature and in all societies. At the same time, Graham is clearly sympathetic to the contemporary plight of the common native people, who have for centuries been given a raw deal. Those commoners he portrays as undeserving of their poverty, marginalization, and loss of identity in the currents of change. In short, like many and perhaps most historians, Graham does more than describe the evolutionary changes in environment and society. He suggests that there are moral issues intertwined in this story that need careful sorting through and thinking about, although he does not set forth any rigid set of values by which to judge the past. One wonders indeed whether there is such a moral standard that all people could agree on.

foreword

xv

Living in Hawai‘i, as both the author and I have done, can awaken one’s sympathies for the birds, plants, and people who have been the victims of competitive evolution—the losers pushed aside or now extinct in the race to acquire and reproduce. But what should be our moral compass to complement our scientific truths? If we take Darwin as a guide to writing a deeper, more inclusive kind of history— one that puts people into nature—to whom should we turn for ethical enlightenment? Evolution and ethics can seem like two separate spheres. Historians believe that facts and values should be brought together into a single narrative, but historians are not the arbiters of morality. The study of history may suggest that ethics and moral sensibilities have evolved in unison with or in opposition to changing structures of nature, power, and dominance. We should not build a wall between the many forms of evolution. And the historian must try to ride that narrow cusp separating fact from value. I see this more clearly than ever after reading Wade Graham’s remarkable work about a little piece of land in the vastness of the Pacific Ocean, so far from the world’s attention and yet so valuable for its multilayered lessons. Hawai‘i has long been one of the most inaccessible places on the planet, and for that very reason, it has become one of the most vulnerable and endangered. Always, it forces us to consider what has been right and wrong in the past; to describe as intelligently as we can the age-old competition for habitat, natural resources, and wealth. At the same time, through the practice of history we can find our way toward greater sympathy and responsibility.

Introduction Outer Island, In Between

What does the history of Molokai have to tell us? Molokai is an island of the Hawaiian chain, located in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and physically average in most respects. It is the fifth largest of the group at 38 miles long and 10 miles wide at its widest point, with an area of 260 square miles and a coastline of 100 miles. It has a representative mix of the astonishing variety of environments typical of the larger Hawaiian Islands: rain forest, mesic forest, semiarid grassland, high mountain bogs, sheer sea cliffs, broad alluvial fans, sandy and rocky coastlines, and fringing coral reefs. It sits squarely in the middle of the eight main islands of the Hawaiian chain: 25 miles east of O‘ahu, the capital and metropolis of the archipelago; 8.5 miles west of Maui; and 9 miles north of Lana‘i (see map 1). On a clear day, it is in sight of five of them (only Kauai and Ni‘ihau are out of sight, below the western horizon). Molokai is also an exception: even occupying its central position, Molokai was always marginal to the political, military, and economic affairs of the Hawaiians, and it has remained marginal in the modern US territorial and statehood periods. For centuries, it has been known as a place of failure—politically, economically, militarily—and as a place of depopulation, emigration, and exile. It has borne much of the worst social and environmental damage in Hawai‘i and continues to lead the state in indicators of malaise such as unemployment, welfare dependency, invasive species, and erosion. It was known to the ancient Hawaiians as Molokai o Pule o‘o (Molokai of the Powerful Prayer), a place of sorcery, poisons, and misty, remote places of refuge, an island easy to subjugate by invading armies but difficult to fully subdue or incorporate into social and economic orders imposed from outside. It has been known for the last several generations of people in Hawai‘i as “the 1

2

Introduction

0

300 km

map 1. Location of Molokai and the Hawaiian Islands in the Pacific Basin.

lonely isle,” a place most often passed by; to most of the world, it is known simply as “the living grave,” where the lepers were banished to wait for death. In all of these senses, Molokai defines the limit of what is called “outer island” Hawai‘i— peripheral and rarely visited. But in physical terms, it is not on the periphery but dead in the center of the group, its cliff-edged, wind-scoured coasts marking off the four most important channels and sea routes in the archipelago—a position that may have been memorialized in its name: as molo means gathering or braiding together, and kai means ocean waters.1 (The use of the glottal stop, Moloka‘i, is likely a modern mistake, possibly the invention of singers catering to tourists in Honolulu in the 1930s tailoring syllables to rhyme in their verses.)2 Molokai is in the middle; to go anywhere between the islands of Hawai‘i, Maui, Lana‘i, Kaho‘olawe, and O‘ahu, one must pass Molokai.3 With its several verdant farming

Introduction

3

valleys and a long shoreline studded with rich fish ponds during the precontact Polynesian period, the island was an opportunity for more powerful outsiders to come conquer and exploit. Hawaiian armies up to King Kamehameha’s in the early nineteenth century had little choice but to stop and fight over the island, often laying it to waste, en route to larger battles elsewhere. After the violence was suppressed, Molokai remained a lure to outsiders looking for land and wealth, who were always more powerful than the few dispersed inhabitants. Molokai is an outer island in between, the near far away, an other place just next door; a place marginal to the main events of history and yet never entirely apart from them, transformed by them and yet filtering their impacts through its own conditions and structures. And, it is the contention of this study that this is not a defect from the point of view of writing history. Indeed, Molokai’s marginality, relative to its larger neighbors and to the larger outside world, gives it a focused explanatory power, like a small lens that refracts and reflects back bigger processes and wider histories with which it has intersected, thereby illuminating them in invaluable ways. Because it is more isolated and simplified in comparison to larger, more central places, certain processes are more visible, their outlines less blurred by complexity. To understand the history of this marginal place is to go a long way toward understanding the history of Hawai‘i, the United States, the Pacific, and the world. One reason I chose Molokai to study is because it is a small, marginal, unimportant place within a somewhat larger, somewhat more consequential place, Hawai‘i—itself at the center of the world’s largest ocean and so a critical junction of Pacific and world history during the past two and a half globalizing centuries, as well as an active frontier of American expansion. Like a doormat, it has been at the center of a lot of action, and like a doormat, it has been really beaten up. And you can see the scuff marks pretty clearly; the island is just lying there open to view, essentially untouched by the modern development that has buried so many of the traces of history on the larger islands beneath hotels, subdivisions, and parking lots. But it is important not to focus exclusively on the island’s negative markers. It is also a place of remarkable endurance, resistance, and cultural resilience. Molokai people gained their reputation for sorcery through a millennium of resistance to powerful outside forces. They were celebrated for fierce independence from the demands of higher-status outsiders in a society rigidly ordered by caste and for an ethos that we might think of in modern terms as nature-centered and communitarian. Since the coming of the rest of the world to the Hawaiian Islands over the last two and a half centuries, Molokai almost alone has maintained many of the values and ways of the old Hawaiians, from the ‘ohana extended family, rooted in the soil of a small valley, to traditional forms of farming and fishing that help sustain a community-based lifestyle that has mostly vanished elsewhere. This is true in large part because the island has been, on the whole, a place of economic stagnation and persistent business and administrative failures. In ancient and modern

4

Introduction

Hawai‘i equally, Molokai was and is thought of as a land of regret for its failures and of longing for what it has preserved. Molokai as a case study has many advantages from a historian’s point of view. It has a well-developed archaeological record, well spread over the island’s breadth, including a trove of groundbreaking work on one of the earliest and longest continuously inhabited Polynesian settlements, at Hālawa Valley. Historical traces are very visible on the island because there has been very little modern agricultural or urban development compared with the other Hawaiian islands. Because it has been marginal to the political and economic development of Hawai‘i in the postcontact period, there has been a retardation of historical effects: what may have happened on O‘ahu in the early nineteenth century might have happened on Molokai in the late nineteenth or even early twentieth, making such events easier for historical methods to see. As a place near but peripheral to the center, O‘ahu, Molokai is a better theater in which to view environmental and economic history than political, diplomatic, or military history or the social history of the elites in Hawai‘i. Because of this— and the fact that these last subjects have been extensively worked over by other historians—this study takes as its focus the nexus between environment and society. It looks at how the land and ecosystems have changed over time with human intervention and at how social structures; land tenure; market conditions; definitions of common resources; and technologies such as irrigation, aquaculture, and new crops, including genetically modified organisms in the twenty-first century, have changed over time and have in turn affected the land. It looks for patterns, relationships, sequences of causation, cascade effects, and scale effects—especially spatial ones—in order to understand how these factors have worked on and with one another and how they have shaped the history of communities in Molokai. Molokai’s exceptionalism has much to do with scale—but not in a straightforward or one-dimensional way. It is comparatively small and so is at a comparative disadvantage in population and resources to other islands. But scale does not work in a simple way: in many ways, the island is large. There are the obvious physical ways: it has the tallest sea cliffs in the world, up to three thousand feet, the longest fringing reef in the Hawaiian Islands, and once had the largest fishpond aquaculture complex in the Polynesian Pacific. And there are other, less obvious ways that have to do with the local, perceived relationships between people and things, which we will explore in this study. Molokai has a bit of everything, such as a representative mix of climates and terrains, as has been noted. It has a thoroughly mixed population, with the largest per capita percentage of native Hawaiians in the state cohabiting with transplanted Europeans and mainland Americans, Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, and many others. Economically, it has supported at one time or another all of the components of Hawai‘i’s history: fishing, irrigated farming, dryland farming, fishpond aquaculture, ranching, sugar, coffee, pineapple, diversified

Introduction

5

fruit and vegetables, light manufacturing, and tourism. It has had irrigation both on a small scale, supporting traditional Hawaiian farms, and on a large scale, watering thousands of acres of industrial plantations. It has had (and continues to have) both a subsistence economy of small farms and homesteads and a huge, outsidecapitalized export agribusiness sector employing cheap immigrant labor. Both have been materially aided by significant state and federal interventions, and both have coexisted on one island—though each mostly has had to itself one very different half of it. The distribution of these features has largely been imposed by environmental variation: wet versus dry, level versus steep, rocky versus fertile. The environment is critical to everything in Molokai, both as constraint and as opportunity: some places are “thick” with natural resources, making them potentially prosperous and so coveted by outsiders; some are resource “thin” and so impoverished and ignored. Water, in abundance or scarcity, has from the beginning of settlement there fundamentally structured human social and economic possibilities and thus how people have restructured the natural environment to suit their aims. Hawai‘i is shaped by a fundamental wet/dry dichotomy, due to the permanent trade winds that produce rainfall on the windward sides of each island and arid rain shadows on the leeward sides. Some of the wettest places on Earth are just a few miles as the crow flies from extremely dry places; this situation is common on all of the large islands, and even on the smallest, precipitation, or the lack of it, is a basic environmental fact. Unavoidably, in Hawai‘i, water is the fundamental organizing principle of both the human and the natural worlds, of the landscape and the social body that lives on it, and of their intersections. Water orders and differentiates production, reproduction, politics, and religion as well as their disorders in the forms of drought, erosion, warfare, and conquest—and in between these extremes, the thread of Hawaiian history unspools. This is a long-range study, of a very long durée, from the antecedents of the arrival of Polynesians in Molokai around the year AD 1000 to our own era. A big part of what is observed is how the settlement and colonization of a remote island archipelago works. In one thousand years, the Hawaiian Islands were settled, in the simplest accounting, twice: once by Polynesians and again after discovery by the outside world in 1778. Really, they were settled many times, over and over again: landfall was made in Hawai‘i by Polynesians many times and by people from nearly everywhere on Earth countless times, bringing with them animals, plants, parasites, pathogens, tools, techniques, ideas, and religions. In both, or all, cases, depending on one’s arithmetic, this amounted to plugging into the world and setting off each time what are effectively the processes of globalization. Thus, our socioenvironmental history is also the history of an environment and society under near-constant stress from outside settlement, colonization, extraction, and the attendant processes of change.

6

Introduction

A key finding of this study is that clear patterns of interactions between people and their environment are visible across Hawaiian history, from the appearance of Polynesians to our own era. Discerning these patterns begins with looking at water. Because water is so unevenly distributed, access to water resources is key to life: irrigated agriculture was at the base of Polynesian Hawai‘i’s economy, religion, and competitive social order. The control of water is everything: from its control flow the control of land, labor, and therefore, power. Under an intensely competitive social order, the control of water in Hawai‘i tends toward—because it strives for—monopoly control of water and thus the rest, as well as a continuous intensification of production for surplus to support that monopoly control and people and resources. Forms of monopoly control of water are clearly and repeatedly visible in both the Polynesian period and in the postcontact period, where water remains at the center of the economic and therefore political and social life of both the nineteenth-century Hawaiian kingdom and the twentieth-century American territory and state. It is also clear from the historical record that monopoly control of water and land resources exacerbates and drives the feedback loop of environmental degradation; the destruction of common resources; and the decline of small, subsistencebased communities, further reinforcing intensification and the control of monopolists. This helps to explain the rapid social change and very high degrees of agricultural development in both the Polynesian and postcontact periods and helps to explain the rapid and severe environmental degradation seen in both periods. This apparent repetition is striking. I refer to it as a historical isomorphism: the similarity of form or structure between two things or organisms with different ancestry, arrived at through convergence. This word is important. It does not mean that the same thing happened twice, or that history repeated itself in Hawai‘i, but that something similar happened (at least) twice, to different people, at different times—but in the same place. In evolutionary biology this is known as convergent evolution, where unrelated organisms assume similar forms while adapting to similar or the same environmental constraints. Seeing this isomorphism in Molokai indicates that deep structures unique to the place pushed apparently very different human societies at very different times toward assuming similar forms. The challenge is to explicate, first, what those deep structures of place are and how they work and, second, how the nature of the societies—their cultures—are worked on by them and work on them in turn. What is revealed? Not, as might be expected, or feared, environmental determinism, where physical geography determines human social outcomes. Instead, the history of Molokai shows a dynamic interaction between different types of environment and different types of social orders, which is not random but shows distinct patterns across long spans of time and is thus suggestive of a strong role of environment in social outcomes—and an equally strong role of social structures

Introduction

7

and values in determining the fate of the environment. Discerning these patterns and how they work is important because in both cases, most of the time, both the environment and a plurality of the members of society came out the worse in the deal, becoming significantly impoverished over time and falling under the control of narrow, monopolizing elites defined largely by heredity. We see that countervailing patterns exist, at the same time, of environmental and social structures that resist control and impoverishment, and yet they are limited, by the same factors that enable the opposite outcome in most cases, across Hawaiian history. A challenge for this study is to make the history of one small island relevant to the larger world. The history of Molokai must be embedded in the history of the milieu (Hawai‘i); in the region (the Pacific); in America, of which it becomes a part; and in the world; hopefully, by learning about the processes that have shaped Molokai, we will learn something about the larger world. Hopefully, it can also be a case study that casts light on and encourages the study of similar places: small, out-of-the-way, marginal, minor places. In 1975, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari called for the study of “minor literature” in its own right, as necessary as the study of the great books and without which the great books cannot make sense.4 This study is informed by the desire to write the history of a minor place because the world is made up of them, and their history shapes the fates of big, major places far more than historians have been willing to allow. It is not a microhistory because it does not assume that Molokai is a microcosm but rather that it is a distinct place with a history linked at all levels with contexts greater and smaller, from the largest stories of human history—migration, discovery, and globalizations—to the intimate histories of families. This study looks at Molokai, but always in context, never in isolation. These contexts range from Hawai‘i to North America to China to Europe. They are considered not simply to illuminate events on Molokai but also to examine how events on Molokai have affected them; all are parts of a continuum, and all share a space-time. There are many general histories of Hawai‘i; most are primarily concerned with the progress of political events. There are many more studies of Hawaiian natural history, since it is one of the great laboratories of evolution on the planet, rivaling the Galápagos in the amount of literature developed. Very few authors have looked at its environmental history—and then not in sufficient relation to the economic and the social. Historiography tends to portray Hawaiian history as primarily a political process—just one more instance of a small, weak Aboriginal grouping succumbing to the irresistible pressures of European and American imperialism. Demographic, economic, and eventual political collapses are seen as inevitable given the progress of world history. The role of the environment is not considered adequately. Yet Hawaiian history is to a great extent a saga of physical and biological changes, of radical transformations in its landscapes and inhabitants, beginning with processes set in motion by the first Polynesian colonizers. From 1778

8

Introduction

onward, it becomes a story of the steady retreat of native Hawaiian people and nature. Politically centered history, riveted by the confrontation between Hawaiian rulers and foreign usurpers, has done a poor job of addressing or understanding these changes. Given that Hawai‘i remained a sovereign monarchy until 1893, it was a unique situation in the island Pacific: not colonial—though perhaps paracolonia—and thus a product as much of internal dynamics as of external ones.5 Land and water are at the center of these internal dynamics and so should be put at the center of Hawaiian history. While the major twentieth-century authors recognize, to varying degrees, the role of environmental stresses, such as deforestation, erosion, desertification, disease, and the myriad effects of species invasion and extinction, little is understood by historians about the mechanisms and extent of these.6 Among professional historians, Ralph Kuykendall and Gavan Daws did the best jobs of acknowledging the role of environment and disease, but they ascribed few motivations and isolated few consequences. Answers to questions as fundamental as what caused the Hawaiians’ demographic decline were based on shaky estimates or guesses drawn from early accounts. Others, such as Lilikala Kame‘eleihiwa, elide nature altogether, dismissing it by positing an eternal “harmony” between Hawaiians and their ‘aina (land), before turning all attention on the cultural chasm that separated the understandings and experience of Hawaiians and haoles (foreigners). This elision ignores copious evidence that the Hawaiians, while certainly living in greater “harmony” with nature than do we in our modern, industrial society, were quantifiably ruinous to aspects of the low-elevation environment of the islands, including forests and birds. Part of the problem is that historians have relied on traditional documentary sources that, when they took any note of the physical world around them, tended to do so in a fragmentary way. A major shortcoming is a lack of attention to scientific studies, from archaeology, paleobiology, geomorphology, and other fields, which have the potential to fill in the wide blanks in the historical documentation. In addition, since the publication of most existing Hawaiian histories, the volume and quality of such work has multiplied enormously.7 This study has relied on several layers and registers of evidence, from traditional historic documents to recent research in the natural and social sciences to visual evidence such as images and mapping, in order to try to reconstruct and diagram physical changes in the islands; to provide a kind of moving picture of the sensible Hawaiian world; and to analyze these changes against the broader social, economic, and political canvasses. The major signal exception to the foregoing complaints is the work of Patrick V. Kirch, one of the world’s leading Pacific archaeologists, and Marshall Sahlins, one of the world’s leading Pacific historical anthropologists, on the relation between Hawaiian social structure and history. Their 1992 collaboration, Anahulu: The Anthropology of History in the Kingdom of Hawaii, a two-volume study of a valley

Introduction

9

in Waialua District, windward O‘ahu, is a synthesis and pairing between archaeological and ethnohistorical investigations of the history of the Anahulu River valley, from precontact up to the aftermath of the Mahele, or land revolution of the mid-nineteenth century. By linking changes in the environmental and the social and insisting that historical analysis map both registers onto one another, this approach illuminates riddles that would otherwise have remained opaque. For example, the authors found, through archaeological excavation, a vast extension of irrigated taro pondfield and ditch construction in the upper valley, about which historical documentation had contained barely a hint. This building boom coincided with King Kamehameha’s second garrisoning of O‘ahu from 1795 to about 1810. They deduced that the king, having seen his first attempt at occupying the island collapse as famine spread under the pressure of his armies, resolved to install a self-sufficient warrior-farmer garrison that could endure indefinitely by settling his Hawai‘i-island fighters and their families on new taro lands high in the watershed. From 1810 to 1825, these lands were gradually abandoned as the ascendant Ka‘ahumanu faction of the ali‘i shifted its corvée demands away from agricultural produce to sandalwood cutting. Briefly, after 1829, there was a new burst of activity, ending with the total collapse of sandalwood resources.8 These discoveries confirm the basic interrelatedness of the natural and the social. Another example of interest is the evidence Anahulu presents of devastation caused by crop and plant diseases, blights, and animal invasions to the productive capacity of rural Waialua District, ultimately contributing to its social and demographic collapse. Kirch and Sahlins tried, in their words, to “bring down the history of the world to the Anahulu river valley.”9 This study takes theirs as an inspiration, but it differs in that its Hawaiian location is larger, its time span longer, and its analytical framework focused on the reciprocating interactions between environment, economy, and society moreso than on the social structure as the driver of these. Several works from American environmental history have helped to guide this study. A general model of how an environmentally literate history can illuminate larger historical questions is Alfred W. Crosby’s Ecological Imperialism.10 Applied to Hawai‘i, Crosby’s approach would benefit from a greater attention to diverse scientific and social scientific literature, to historical geography, and to the native Hawaiian side of the story, expressly including the history of processes begun by Polynesians that then continued, often in radically accelerated form, after 1778. In this regard, William Cronon’s book Changes in the Land and Stephen J. Pyne’s work, including Fire in America and Burning Bush, are excellent examples of how indigenous practices powerfully shaped land and water long before European arrivals.11 The work of Jeremy Adelman, Stephen Aron, and Richard White on borderlands and frontiers is directly applicable to the history of Hawai‘i, which, in the period from contact in 1778 to the American-led overthrow of the monarchy in 1893, while remaining nominally sovereign, was nevertheless a borderland between

10

Introduction

competing imperial powers in the Pacific and a place where a diverse mixture of people from all over the world shared space with native Hawaiians in a complex, shifting “middle ground” between overlapping, rivalrous sets of political, economic, military, cultural, and environmental worldviews and practices.12 Donald Worster’s lifelong focus on how structures of class, expertise, and power interact in the settlement of marginal landscapes and, not coincidentally, his focus on the links between irrigated agriculture and political domination, inform this study throughout.13 Indeed, the United States Bureau of Reclamation, which he chronicled in Rivers of Empire, played a central role in the transformation of West Molokai into a terrain of industrial agriculture in the second half of the twentieth century (as will be seen in chapter 5). In Molokai and elsewhere in Hawai‘i, the Bureau of Reclamation and other government agencies at both the state and federal levels actively intervened on behalf of large landowners and commercial interests by imposing policy, fiscal, and legal frameworks that aided their capture of resources, often to the detriment of smaller, local interest groups and communities. This aspect of Hawai‘i’s history underscores its commonalities and continuities with the experience of the American West, including Alaska, with state and federal lands and environmental agencies and policies. The recent work of Jared Diamond has brought wide attention to many of the insights of environmental historians by synthesizing their work and that of numerous scientific investigators in some of the fields previously listed into large-scale, panoramic histories of human experience, using comparisons between large and small social and physical entities, sometimes widely separated in time and space.14 His book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed proposed to link environmental factors with the historical failures or the collapse of societies. Diamond’s initial premise was that factors such as soil fragility, aridity, small size, extreme climatic conditions, and climate change contributed greatly to the likelihood of failure of societies. But in his survey of case histories, it is clear that the environment is rarely the determining factor. Severe cases of collapse occur both on small islands, such as Easter and Henderson in the South Pacific, and in large continental regions, such as the American Southwest and Central America. While all seem to share one or more types of ecological marginality, there are many different variables. Diamond tirelessly cataloged and sorted natural structures and factors according to rubrics such as fragility versus resilience or eight kinds of degradation, including deforestation, soil degradation, overhunting or overfishing, population growth, and so on. Yet, given his inclusion of so many dissimilar places, no pattern emerged that convinces one that environmental damage is a programmatic, comprehensible factor in the success or failure of different societies in different places at different times. Diamond allowed as much in his introduction to the volume, admitting, “I don’t know of any case in which a society’s collapse can be attributed solely to environmental damage: there are always other contrib-

Introduction

11

uting factors. When I began this book, I didn’t appreciate those complications, and I naively thought the book would be about environmental damage.” He designated five sets of factors: environment, climate change, hostile neighbors, friendly trading partners, and each “society’s response to its environmental problems.”15 On completing the study, he found that only the last factor “always proves significant”; the first four “may or may not prove significant.” In spite of the exhaustive taxonomies of factors, no hierarchy organizes all the many variables, and no set of rules orders them into a global logic or a set of criteria that would be useful for prediction. Each case study is a good description and is unique, like an address— or a history. In the end, Diamond succeeded in writing a series of fascinating histories—a venerable and valuable narrative art form to be sure—but fell short of his goal of finding a kind of science of the failures of societies. What was missing, even from the point of view of satisfying narratives, was an appreciation for culture, a thing much maligned among historians and scientists alike, apparently because of its high-profile career among the anthropologists in the twentieth century. But it is inescapable. Even in the case of the smallest, most resource-impoverished places that Diamond described, it is easier to place blame for the failure of long-term colonization on the shortcomings of the social structure involved than on the environment there. In each case, the moves that precipitated a collapse were cultural failures to adapt or respond adequately to environmental challenges rather than simply these challenges themselves. In each case Diamond narrated, culture was the man behind the curtain: decisions were made—economic, military, legal, reproductive, even aesthetic—that had an impact on the tendencies, trajectories, and outcomes of the societies under the microscope. Cultural categories were often the fundamental, causative problems such as elite competition and unaccountability, warmaking, religion, dictatorship, and the most powerful and environmentally (and socially) damaging of these, the “lust for power.” We hardly need an environmentally centered history to tell us this. And such a history, focused on cataloging and understanding physical factors, is not sufficient to get to the bottom of the story. What is needed is a catalog of cultural factors alongside physical ones and an analysis of their dynamic interaction where historical outcomes are produced. What Collapse proved is that while environment is hugely important in influencing historical outcomes, environment is not destiny; it is just a set of constraints and limitations on which and within which human social structures and values work and are in turn worked on. The lesson is that it takes two to tango, and neither partner—environment or society—always or necessarily leads the dance. This study of Molokai is an effort to write a history of a Hawaiian island and, through it, of the Hawaiian Islands, that combines the optics of nature and culture into a more integrated practice of history than we have generally seen in this reach of the ocean.

1

Wet and Dry The Polynesian Period, 1000–1778

The moment that the first Polynesian canoes touched Hawaiian beaches, around AD 1000, marked one of the culminating achievements of the greatest seaborne colonizing society in the premodern world.1 Over a two-thousand-year period, Polynesians perfected techniques of long-range ocean voyaging and permanent agricultural settlement that allowed them to claim small islands and thrive in an archipelagic realm covering a quarter of the globe. Contrary to earlier theories that held that these mariners must have been descendants of migrants into the region from as far away as Asia or India, archaeologists now believe that “becoming Polynesian took place in Polynesia,” in the words of Patrick Kirch, the preeminent Pacific archaeologist and professor at the University of California, Berkeley. According to this view, ancestral Polynesian culture evolved in situ first, from Melanesian and “Austronesian” Southeast Asian antecedents, up to thirty-five hundred years ago in what is called the Lapita cultural cradle area in eastern Melanesia. From there, these peoples reached Fiji and then Tonga and Samoa by perhaps 880 BC, where, over the next millennium, the fully formed Polynesian cultural complex incubated. It was a lifestyle based on crops—the Melanesian suite of vegetatively propagated roots such as aroids (taro, or kalo in Hawaiian) and yams—supplemented with orchard crops, such as coconuts and breadfruit, and fish and other products of the surrounding sea. In maintaining links between these neighbor islands, Polynesians effectively created a “voyaging nursery”: the small, outrigger canoes of Melanesia and Southeast Asia became large oceangoing vessels equipped with double hulls and lateen sails, sailed by large crews and guided by a supple science of navigation by stars, winds, currents, swells deflected between islands, and the signs of birds and other creatures.2 In the face of the near-constant easterly trade 12

Wet and Dry

13

winds at this latitude, Polynesians perfected the art of sailing upwind to remote landfalls and then returning to their islands of origin. When, after one thousand years, the cultural conditions coalesced in favor of purposefully searching for new lands to colonize, the skills and technologies required were in place, allowing Polynesians to reach nearly every (not yet populated) inhabitable island in the Pacific Ocean and establish themselves on them. The first waves of settlement out from the Fiji-Tonga-Samoa-Futuna core reached the Society group and the Marquesas; later migrations traced northward up the Line Islands to Hawai‘i; eastward to Easter (Rapa Nui); and southward to Mangareva, the Southern Cooks, and finally, New Zealand (Aotearoa) by AD 1200–1300—making it “one of the last places on earth to be settled by preindustrialized humans,” in Kirch’s words.3 The addition of the South American sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) to the crop repertoire of the last-settled islands also indicates Polynesian contact with that continent.4 Polynesians went—and stayed— everywhere, occupying even rocky, inhospitable Pitcairn and Henderson in the Eastern Pacific, and remote islets like Necker and Nihoa in the Hawaiian chain northwest of Kaua‘i, for as long as six hundred years.5 Linguistic and material evidence shows that they maintained links between islands across formidable distances for centuries, before isolation returned for unknown reasons.6 When Europeans ventured into Polynesia in numbers in the eighteenth century, they immediately recognized that the widely dispersed people they encountered, from Tahiti to Easter Island to New Zealand to Hawai‘i, belonged to a single group closely related by race, language, religion, technology, and cultural patterns and organization from agriculture to architecture. This expansion was not just a question of boats and navigation: the islands of the Pacific east of the Solomons had few edible plant or animals species, especially on atolls.7 Prospective settlers had to bring almost everything with them, providing a textbook example of what the anthropologist Edgar Anderson called “transported landscapes” and the historian Alfred Crosby called a “portmanteau biota”: all the biological resources necessary to long-term survival, without which the technological and cultural skills of the voyagers would have proven useless.8 Settlers in Hawai‘i would eventually import dogs, pigs, chickens, rats, and the Hawaiian horticultural complex (differing only in emphasis from that of elsewhere in Polynesia): taro (kalo), sweet potato (‘uala), yam (uhi), banana (mai‘a), sugarcane (kō), breadfruit (‘ulu), coconut (niu), paper mulberry (wauke), kava (‘awa), gourd (ipu), ti (ki), arrowroot (pia), turmeric (‘olena), and bamboo (‘ohe).9 All across Polynesia, the colonizers adapted to fit the diverse environmental circumstances they found. In a general sense, these can be divided into the three principal kinds of islands in the Pacific: atolls, makatea islands, and high islands. Their origins can be either from “arc” islands or “hot spot” islands. All Pacific islands are volcanic or tectonic in origin; most on its western margin are arc islands, accretive

14

Wet and Dry

products of plate margin subduction, wherein pieces of crust sitting atop the diving plate are scraped off onto the overriding plate. Arc islands, such as New Zealand, Fiji, and New Caledonia, are often large and mountainous. In the mid-ocean, including most of Polynesia, islands are products of midplate hot spots—plumes of molten magma rising from the earth’s mantle that pierce the crust to form volcanic shields; as the plates move over the stationary plume, islands string out like beads on a necklace, leaving lines, arcs, or clusters of islands diminishing in size as they recede in distance and time from their point of origin and erode back into the sea. High islands, such as Tahiti, Rarotonga, and the main Hawaiian islands, are examples of relatively recently formed hot-spot islands. Built of volcanic basalts and lavas, younger islands often lack surface water because of extreme rock porosity and lack fringing reefs because of steep slopes into the surrounding depths. Older high islands, removed by plate motion from the building process of the hot spot, gradually erode, developing deeply incised stream valleys, broad coastal flats, and fringing or barrier reefs. Atolls are formerly high islands that have been lowered, through a combination of erosion and subsidence under their own weight, to near or below sea level, leaving fringing reefs surrounding a volcanic core that eventually disappears, leaving no dry rock, just a barrier reef surrounding a lagoon. Makatea islands are older atolls or subsided high islands where previously submerged portions have been partially raised above water, either by falling sea levels or by tectonic forces. Typically, the uptilt is caused by the weight of a nearby, related volcanic shield formation. Makatea means “white stone,” after the exposed limestone of former reefs elevated to become limestone ramparts and plateaus. These are often marginal environments for cultivation because rainfall disappears into their porous limestone karsts and thin soils. Mangaia and Henderson, both islands with histories of socioenvironmental stress, are examples.10 Within environmental limits, most Polynesian societies thrived—and evolved. The ability of Polynesian societies to adapt their main crop, taro (Colocasia spp.), to highly varying circumstances is the most significant “event” in Polynesian prehistory, second only to success at voyaging. All of these adaptations involved the control of water. On atolls, which are typically dry zones because of high soil porosity and low rainfall, taro was grown by pit cultivation: digging down through the sand or coral to the thin freshwater lens overlying the seawater. On high islands and makatea islands with swampy coastal valleys, it was by raised-bed cultivation: digging drainage canals through the swampy flats and heaping the spoils up into mounds where taro, yams, sugarcane, and other crops were planted. On high islands with well-developed stream valleys, irrigated pondfields were constructed, with streams diverted through barrages and ditches to a series of linked, walled paddies, in which flooding and drainage were controlled by means of headgates. Several writers have pointed to a seeming paradox of Polynesians’ existence: though accomplished at seafaring and fishing, the majority of them derived their

Wet and Dry

15

subsistence from the land. The dominance of the land over the sea would have profound effects on the history of Hawai‘i, as we will see later; here I will list just a few examples. E. S. and Elizabeth Handy, with Mary Kawena Pukui, in their classic study Native Planters in Old Hawaii, cite much evidence that most common Hawaiians were farmers, not fishers.11 Suggestively, the word for an island or a division of land, moku, is also that for a ship or a boat. The sea as highway is a frequent metaphor in legend and oral tradition, and it is even reported that some Polynesian navigators talked about the moving sea passing by the stationary canoe.12 In an agricultural society with a severely limited land base that practiced a form of primogeniture, younger sons would be pushed to sea in search of tillable land: as it was for many of the Scandinavian Vikings who sailed off in search of new lands, oceanic expansion was a farmer’s imperative.13 NAT U R A L H I S T O RY O F T H E PAC I F IC I SL A N D S

The discoverers of Hawai‘i found the largest piece of unclaimed island real estate in the Pacific, excluding New Zealand: an area of 16,692 square kilometers (6,424 square miles) 30 percent larger than Connecticut.14 It was also the most remote: 2,557 miles from Los Angeles, 5,541 miles from Hong Kong, 3,847 miles from Japan, and 5,070 miles from Sydney.15 The insularity of the Hawaiian Islands, together with their geologic history, accounts for much of their physical—and in certain ways, their social—destiny. From its origin over a stationary, midplate hot spot now under the island of Hawai‘i, the Hawaiian chain extends 2,449 miles westward toward Kure Atoll, where the eroding volcanoes submerge, then carries on northward as the Emperor Seamounts, ending at Meiji Seamount, beyond which the Pacific Plate subducts into the Kuril Trench off Kamchatka. The oldest seamounts date to seventy-five million to eighty million years; the islands’ life span above water varies from eight million to fifteen million years.16 Active volcanism is limited to the zone directly over the hot spot: three volcanoes on the island of Hawai‘i—Mauna Loa, Hualalai, and Kilauea—and Haleakala volcano on Maui, have erupted historically (since 1778). Mauna Loa last erupted in 1984, while vents on Kilauea have erupted continuously since that year. The island-making process continues: Loihi, a new, actively building, submerged volcano southeast of the Big Island, is expected to surface in roughly one hundred thousand years. On these islands, age is fundamental to form. The Big Island of Hawai‘i, so new that its surface rocks are no more than a million years old, has no significant stream valleys with developed soils, except on its northernmost and oldest coasts, Kohala and Hamakua. Offshore, its slopes drop precipitously into deep water, and consequently, the island has no fringing coral reefs. By the same token, as islands increase in age, erosion gradually changes their character: at the other end of the main group, five-million-year-old Kaua‘i is typified by deep canyons, broad

16

Wet and Dry

and swampy coastal valleys, and more generous fringing reefs than on the other islands. As age equals geomorphology in a general sense, topography is fundamental to climate at the local level, and variation is tremendous. Ten percent of the main island area is above 7,000 feet, with relatively cold temperatures; Mauna Kea volcano on Hawai‘i reaches 13,796 feet and boasts ancient glaciers and a seasonal snowcap. Precipitation varies abruptly and radically depending on local topography, with the main dynamic being orographic rain produced over windward mountains by the prevailing trade winds from the northeast and compensatory rain shadows in their lees: Mount Waialeale on Kaua‘i receives up to 486 inches of rain, more than forty feet, the highest total in the world; not far away, in its rain shadow, is a desert. The northeasterly trades are so predictable—blowing at or above twelve miles per hour 50 percent of the time in summer and 40 percent of the time in winter—that the windward/leeward (ko‘olau/kona) distinction orders climate, vegetation, and land use a priori in Hawai‘i.17 With the exception of areas too low to create orographic clouds (below about one thousand feet) and that are therefore largely arid—such as West Molokai and much or all of Lana‘i, Kaho‘olawe, and Ni‘ihau—windward areas are wet, and leeward ones are dry, irrespective of elevation. Windward coasts (with the previous exceptions) are well watered yet see some sunshine most days. With increasing elevation, windward ranges are wetter and more often cloud shrouded, clothed in deep forest dominated by ohi‘a lehua (Metrosideros collina), until the alpine zone, above eight to ten thousand feet. At higher elevations, the flanks and lees of mountains are covered in mixed mesic, or medium rainfall, forest dominated by koa (Acacia koa). Low leeward areas once grew a distinctive, variegated dry forest, though this has been very nearly wiped out since human colonization and replaced with grasslands. Precipitation gradients are commonly extreme, as much as 118 inches in a mile, though more typically 25 inches per mile.18 Nearly every main island has rain forests just around the corner, so to speak, from semiarid zones or neardeserts that see fewer than 20 inches per year. In between can be found a representative of every climate zone on Earth from subtropical to alpine, save true tropical humidity and polar cold. Mark Twain wrote in 1866 that if a person were to stand at the top of Mauna Loa, “he could see all the climes of the world at a single glance of the eye, and that glance would only pass over a distance of eight or ten miles as the bird flies.”19 Indeed, on the Big Island of Hawai‘i, one can deliberately select one’s preferred weather conditions by simply driving for five to twenty minutes. Even so, fully half the islands’ area is below two thousand feet, with a stable year-round temperature ideal for cultivating the oceanic crop suite: temperatures average 77 degrees Fahrenheit at sea level and vary seasonally about 5 degrees Fahrenheit at Hilo and 6.5 degrees at Honolulu. Below five thousand feet elevation, the seasonal variation does not exceed 9 degrees, and this is almost exclusively where the precontact Hawaiians lived and worked.20

Wet and Dry

17

Insularity and isolation, more than any other factors, have shaped Hawai‘i’s natural history. Because of the “volcanic conveyor belt,” habitats have continuously evolved, fragmented, and disappeared as new islands have arisen, and old ones have eroded and disappeared.21 As specks of land in the mid-Pacific ocean, any animals or plants that reached Hawai‘i had to do so over vast expanses of water— limiting potential immigrants to those that could fly or ride exceptionally well. There were no reptiles, amphibians, or land mammals, save one species of bat, in Hawai‘i prior to human settlement. This lack of representation of groups common on more varied continental areas is called disharmony and extended even to types of insects and birds that presumably had better chances of colonization, so great was the difficulty of successfully establishing a population. Hawaiian flora and fauna is disproportionately made up of members of a handful of families. In fact, the prehuman Hawaiian flora of eleven hundred species can be accounted for by just 275 successful immigrants over 27.5 million years, a rate of one introduction every 100,000 years.22 A corollary of disharmony is impoverishment of diversity— that is, a biota made up of less than the full complement of species that made up the ecosystem in which the immigrant organism evolved: competitors, congeners, predators, and parasites. Successful immigrants into a depauperate environment are then free to move into and adapt to open habitat niches, a process called radiation, often rapidly speciating into a variety of new forms unprecedented in their ancestry. As an archipelago of continuously transforming high islands with radical climatic gradients over short distances, Hawai‘i presented successful colonists with a dizzying array of different habitat types, resulting in stunning biodiversity and a level of endemism unknown elsewhere in the world. Among plants, insects, spiders, moths, birds, freshwater fish, shrimp, and snails adapted to trees, land, and freshwater, evolution produced not only new species but entire genera unique to Hawai‘i. Among the forest birds is the most spectacular example, the Drepanidae, or Hawaiian honeycreepers, with forty-two historically known species exhibiting an extraordinary diversity of color, form, and lifestyle, all descended from a single ancestor.23 Had Darwin landed in Hawai‘i before the Galápagos, he might have had the evidence he needed to come out with his theories decades earlier. Yet in the process, it is typical of colonizing organisms to lose the extraordinary powers of dispersal that got them to the islands and shed defensive characters that no longer serve any purpose. With no herbivorous animals, Hawaiian plants generally have no thorns or toxic compounds: mints have lost their oils and raspberries, their spines. This loss of defenses would come back to have devastating consequences when Hawai‘i was suddenly “reconnected” with continental flora and fauna with the advent of Polynesians and later, Europeans and Asians.24 Molokai had its share of unique species, including, in the historic period, the endemic birds kākāwahie, or Molokai creeper (Paroreomyza flammea); ō‘ō, or

18

Wet and Dry

Molokai or Bishop’s ō‘ō (Moho bishopi); mamo, or black mamo (Drepanis funerea); and numerous plant species, including the lo‘ulu palms Pritchardia forbesiana and P. lowreyana and the tree hibiscus Kokia cookei. SE T T L E M E N T O F M O L O KA I

Molokai, the fifth largest of the eight main islands, is 38 miles long and 10 miles wide at its widest point, with an area of 260 square miles and a coastline of 100 miles. It lies 25 miles southeast of O‘ahu, 8.5 miles northwest of Maui, and 9 miles north of Lana‘i—a position in the center of the archipelago and thus at the locus of four of the archipelago’s most important channels and essential sea travel routes. This location may have been memorialized in its name, as molo means “to interweave and interlace,” and kai means “sea” or “seawater.” Or the name is of unknown, ancient origin and cannot be translated—though this seems unlikely given the wealth of layered linguistic tradition around names in Hawai‘i and Polynesia, generally. (The use of the glottal stop, Moloka‘i, is likely a modern mistake, possibly the invention of singers in Honolulu in the 1930s who tailored syllables to rhyme in their verses.)25 The island is an amalgamation of two originally separate volcanoes; topographically and climatically, they retain their differences. The eastern half of the island is dominated by steep mountains; the tallest is the 4,970-foot Kamakou peak. Its north shore, the Ko‘olau district, consists of precipitous sea cliffs, at 3,000 feet the highest in the world, plunging into deep water. At its center is a large collapsed caldera, drained by three deep, steep-sided valleys open to the sea: Waikolu, Pelekunu, and Wailau. All are heavily forested and virtually inaccessible except by sea—and even then sometimes only in the summer months, when the giant northerly swells and the high trade winds that make landings impossible much of the rest of the year subside. At the eastern tip of the island is a narrow bay opening into another long valley, Hālawa, which can be reached overland from the south. East Molokai’s south slope, the Kona district, known locally as mana‘e side to the east of Kamalō (from mana‘e, east, versus malalo, or west of Kamalō), is deeply dissected by roughly fifty sets of alternating narrow valleys and ridges, some nearly vertical in the upper reaches, where they are known collectively as the canyon country. The higher elevations are forested, while, moving downward and southward, rain shadow progressively dries the landscape. Some perennial streams exist here and, at the immediate coast, abundant groundwater surfaces near shore or just offshore in shallow sea water. The south side, sheltered from trade swells by mountains and from southerly winter kona storms by Lana‘i, has some of the most developed fringing reefs in the islands. The middle portion of Molokai is a gradually sloped shield formed by lava from the eastern volcano and the alluvial outwash plains from both ancient volcanoes, becoming progressively more arid toward the west. The West End is dominated by the

Wet and Dry

19

remnants of Mauna Loa, now reduced to 1,381 feet. Its landscape is arid or semiarid except for the peak itself. There are sandy beaches facing fringing reefs on the south side but only isolated beaches, without developed reefs, on the west and north sides. As on the East End, the West End’s north coast consists mainly of sea cliffs exposed to the rough waters of the open ocean. Midway along, extending seaward at the base of the cliffs, is Kalaupapa Peninsula, a more recent volcanic product shaped liked a low lava table, or, as its name indicates, a stone leaf lying on the sea. Probably the earliest Hawaiian settlement site known for Molokai was found in the backshore dunes at the seaward entrance to Hālawa Valley, likely settled by AD 1200–1400.26 While the first archaeologically recorded Hawaiian sites, such as the Bellows dune site on windward O‘ahu, came earlier, perhaps as early as AD 800, the initial settlement at Hālawa was presumably typical of Hawaiian subsistence patterns in the colonization period.27 Excavation of this stratified site revealed the long-term occupation of a small, nucleated fishing camp consisting of several dwellings and hearths, loosely grouped and probably inhabited by a small group of people. Artifacts recovered indicate direct affinities with the material culture of the Marquesas, according with the broad archaeological consensus that the initial colonization of Hawai‘i originated in that island group.28 Hālawa has many advantages that would have made it ideal for early Hawaiians, and judging from the archaeological record, it is exemplary of how early Polynesian settlers fit their economy and culture into Hawai‘i’s physical environment and how that environment in turn shaped the development of Hawaiian culture. Three kilometers long, the valley is nearly one kilometer wide at the coast, narrowing to less than half a kilometer inland. Unlike the other large valleys on the north coast, where plunging sea cliffs and exposure to winter surf make access difficult, Hālawa is somewhat sheltered in a bay, with a headland to the north and a cape to the southeast blocking swells and a navigable river mouth and estuary easily accessible to canoes. The bay and shoreline have abundant invertebrates and fish. Fossil remains from the earliest period show a preponderance of mollusks and inshore fish in the diet—though no tuna or other deepwater species—as well as pigs, dogs, and rats.29 Hālawa’s name means both “curve,” perhaps in reference to the bay, and plenty (lawa) of stems (ha), either of kalo, sugarcane, coconut, or banana—indicating its potential for Polynesian agriculture.30 Everywhere in Polynesia, where conditions allowed, well-watered but sunny windward valleys, ideal for kalo cultivation, were the first locations settled. These have been called the “salubrious cores” that sustained settlers until they could multiply and expand out into less favorable environments. The Hālawa Stream is reliably perennial, draining a large watershed in the high mountains of East Molokai through four tributaries. Rainfall high in the watershed is above one hundred inches and above sixty inches at the head of the

20

Wet and Dry