Both Hands: A Life of Lorne Pierce of Ryerson Press 9780773588646

The life and times of a landmark creator of Canadian culture.

136 27 10MB

English Pages 656 [663] Year 2013

Cover

Title

Copyright

Contents

Acknowledgments

Chronology

Introduction

1 Lorne, Mother, and Methodism: Delta, Athens, and Off to Queen's, 1890–1908

2 Visions, Vistas, and Edith: Queen's University, 1908–1912

3 "These Waste Places of God's Great Vineyard": Teaching and Preaching in the Canadian West, 1909–1914

4 Wrestling with "the Gods of the Methodist Discipline": Victoria College, Toronto, and Union Theological Seminary, New York City, 1914–1916

5 Orange Blossoms, the Cloth, and Khaki: Marriage, Ministry in Ottawa, and Army Service, 1916–1918

6 Shining in the Rural Shade: Spreading the Social Gospel in Brinston, 1918–1920

7 A New Career and Health Challenges: Lorne Pierce and Ryerson Press, circa 1920

8 "On The Hop": Lorne's Pierce's Uneasy Apprenticeship at Ryerson Press, 1920–1925

9 A Strike, a Spat, and the Spirit World: Lorne Pierce, E.J. Pratt, William Arthur Deacon, and Albert Durrant Watson, 1921–1924

10 "A Patron of … Optimistic Snorts and Whoops": Lorne Pierce, Bliss Carman, Wilson MacDonald, and Launching the Makers of Canadian Literature Series, 1922–1925

11 Up against the Bottom Line: An "Annus Horribilis" at Home and at Work, 1925–1926

12 "Lyrical Wild Man": Poetry Chapbooks and the Lure of Textbook Projects, 1925–1950

13 On the Long Textbook Trail: The Rocky Road to Success with the Ryerson-Macmillan Readers, 1922–1930

14 Cross-Canada Success for the Ryerson-Macmillan Readers: In the Shadow of Copyright, 1930–1936

15 From Romantic History to Academic History: Publishing C.W. Jefferys and Harold Innis, 1921–1951

16 Through the Depression to Greater Autonomy: Publishing Frederick Philip Grove and Laura Goodman Salverson, 1933–1954

17 Publishing Art History in the Shadow of the Second World War: Ryerson's Landmark Canadian Art Series, 1937–1948

18 Wearing the Heart Out in Wartime: Lorne Pierce, Ryerson Press, and the Second World War, 1939–1945

19 "Tempting Satan and the Bailiff ": Juggling Modernist and Traditional Poetry in the 1940s and 1950s

20 Impresario and Aging Lion: Fielding a New Generation of Critics and Writers, 1940–1960

21 "Near the Exit": Lorne Pierce's Final Decade, 1950–1961

Epilogue

Appendix: Lorne Pierce's Prayer for One Day Only

Notes

Index

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Sandra Campbell

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

Both Hands

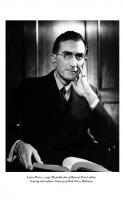

Lorne Pierce, c. 1955: The public face of Ryerson Press’s editor, hearing aid in place. Courtesy of Beth Pierce Robinson

BOTH HANDS A Life of Lorne Pierce of Ryerson Press SANDRA CAMPBELL

McGill-Queen’s University Press Montreal & Kingston ∙ London ∙ Ithaca

© McGill-Queen’s University Press 2013

ISBN 978-0-7735-4116-0 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-7735-8864-6 (ePDF) ISBN 978-0-7735-8865-3 (ePUB) Legal deposit second quarter 2013 Bibliothèque nationale du Québec Printed in Canada on acid-free paper that is 100% ancient forest free (100% post-consumer recycled), processed chlorine free This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Funding has also been received from the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Carleton University. McGill-Queen’s University Press acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Campbell, Sandra Both hands : a life of Lorne Pierce of Ryerson Press / Sandra Campbell. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7735-4116-0. – ISBN 978-0-7735-8864-6 (PDF). – ISBN 978-0-7735-8865-3 (EPUB). 1. Pierce, Lorne, 1890–1961. 2. Publishers and publishing – Canada – Biography. 3. Editors – Canada – Biography. 4. Ryerson Press – Employees – Biography. I. Title.

Z483.P53C34 2013 070.5092 C2013-900362-2

Set in 11/13.5 Adobe Caslon Book design & typesetting by Garet Markvoort, zijn digital

For Duncan and in memory of my parents,

Barbara Van Orden (1917–1986) and

Cornelius J. Campbell (1904–1989), who both, whatever the vicissitudes of life, loved books and reading “Henceforth, listen as we will, The voices of that hearth are still …” – John Greenleaf Whittier, “Snow-Bound”

This page intentionally left blank

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments ∙ ix Chronology ∙ xiii Introduction ∙ 3 1 Lorne, Mother, and Methodism: Delta, Athens, and Off to Queen’s, 1890–1908 ∙ 14 2 Visions, Vistas, and Edith: Queen’s University, 1908–1912 ∙ 40 3 “These Waste Places of God’s Great Vineyard”: Teaching and Preaching in the Canadian West, 1909–1914 ∙ 59 4 Wrestling with “the Gods of the Methodist Discipline”: Victoria College, Toronto, and Union Theological Seminary, New York City, 1914–1916 ∙ 76 5 Orange Blossoms, the Cloth, and Khaki: Marriage, Ministry in Ottawa, and Army Service, 1916–1918 ∙ 103 6 Shining in the Rural Shade: Spreading the Social Gospel in Brinston, 1918–1920 ∙ 122 7 A New Career and Health Challenges: Lorne Pierce and Ryerson Press, circa 1920 ∙ 140 8 “On The Hop”: Lorne’s Pierce’s Uneasy Apprenticeship at Ryerson Press, 1920–1925 ∙ 160 9 A Strike, a Spat, and the Spirit World: Lorne Pierce, E.J. Pratt, William Arthur Deacon, and Albert Durrant Watson, 1921–1924 ∙ 175 10 “A Patron of … Optimistic Snorts and Whoops”: Lorne Pierce, Bliss Carman, Wilson MacDonald, and Launching the Makers of Canadian Literature Series, 1922–1925 ∙ 200

11 Up against the Bottom Line: An “Annus Horribilis” at Home and at Work, 1925–1926 ∙ 225 12 “Lyrical Wild Man”: Poetry Chapbooks and the Lure of Textbook Projects, 1925–1950 ∙ 253 13 On the Long Textbook Trail: The Rocky Road to Success with the Ryerson-Macmillan Readers, 1922–1930 ∙ 272 14 Cross-Canada Success for the Ryerson-Macmillan Readers: In the Shadow of Copyright, 1930–1936 ∙ 291 15 From Romantic History to Academic History: Publishing C.W. Jefferys and Harold Innis, 1921–1951 ∙ 317 16 Through the Depression to Greater Autonomy: Publishing Frederick Philip Grove and Laura Goodman Salverson, 1933– 1954 ∙ 341 17 Publishing Art History in the Shadow of the Second World War: Ryerson’s Landmark Canadian Art Series, 1937–1948 ∙ 360 18 Wearing the Heart Out in Wartime: Lorne Pierce, Ryerson Press, and the Second World War, 1939–1945 ∙ 384 19 “Tempting Satan and the Bailiff ”: Juggling Modernist and Traditional Poetry in the 1940s and 1950s ∙ 409 20 Impresario and Aging Lion: Fielding a New Generation of Critics and Writers, 1940–1960 ∙ 429 21 “Near the Exit”: Lorne Pierce’s Final Decade, 1950–1961 ∙ 460 Epilogue ∙ 495 Appendix: Lorne Pierce’s Prayer for One Day Only ∙ 505 Notes ∙ 507 Index ∙ 627

Acknowledgments

A

s Virginia Woolf wrote with respect to fiction, a biography is attached to life at all four corners. Many people and several institutions helped me to make connections between my research on Lorne Pierce and Canadian life and culture, and I am grateful to all of them. The staff of the Queen’s University Archives, home of the voluminous Lorne Pierce Papers (whose comprehensiveness has been both a blessing and a burden), have been very helpful through the tenure of several archivists – the late Shirley Spragge, the late Donald Richan, and Paul Banfield. I have particularly warm memories of the helpfulness of, first and foremost, archivists George Henderson and Stewart Renfrew – both now enjoying a productive retirement – as well as Gillian Barlow, Heather Holmes, Jeremy Heil, Susan Office, and other staff of that incomparable reading room. Thanks are also due those at the Edith and Lorne Pierce Collection of Canadiana at the Queen’s Library, including its retired head, W.F.E. Morley (who generously presented me with now dog-eared copies of the Frank Flemington bibliography and the Wallace bibliography of Ryerson Press when I began my research), and Barbara Teatero. Elsewhere, I was helped by Carl Spadoni and his staff at the William Ready Archive at McMaster University, by Lorna Knight, then at the National Library of Canada, and by Anne Goddard and Charles MacKinnon (my former Grade 12 teacher at Noranda High) at the National Archives of Canada (now Library and Archives Canada). Phebe Chartrand, then an archivist at the McGill University Archives, shared knowledge and laughter. I also benefited from the personnel and resources of the United Church Archives, Victoria University; the University of Toronto Archives; the Victoria University Archives in the E.J. Pratt Library and the Fisher Rare Book Library at University of Toronto; and the archives at the University of Ottawa. Many individuals took an interest in my work on Lorne Pierce and variously provided most welcome encouragement, hospitality, advice, or information. Any errors or omissions are mine: the largesse is theirs.

x

Acknowledgments

Thanks to: Kerry Abel, D.M.R. Bentley, Michael Bliss, Anna Chester, Lorne Chester, Gwen Davies, Susan Thomson Dewar, Gwyneth Evans, David and Joan Farr, Paul Fritz, Michael Gnarowski, Joan Gordon, Debby Gorham, Norman Hillmer, Ed Horn, Heather Jamieson, Peggy Kelly, Kelly House Bed and Breakfast, Marianne Keyes, John Lennox, Glenn J Lockwood, Roy MacSkimming, Brian McKillop, Hon. John Matheson, Seymour Mayne, Mary O’Brien, Brian Osborne, Jeremy Palin, Michael Peterman, Susan Pollak, Pauline Rankin, Anne Richard of Rose Cottage Bed and Breakfast, Brian and Gillian Robinson, Mary Rubio, David Russo, Marianne Scott, David Staines, John Taylor, Clara Thomas, Frank Tierney, Collett Tracey, Marie Tremblay-Chenier, Glenna Uline, Pamela Walker, Tracey Ware, and Elizabeth Waterston. Sadly, some generous souls are no longer here to be thanked: the late Mary Beesly, C.H. Dickinson, Robin Farr, John Webster Grant, Pearson Gundy, A.C.H. Hallett, Marshall “Padre” Laverty, Rob McDougall, Lorraine McMullen, Mary Mott, the incomparable Jacqueline Neatby, J.D. “Jack” Robinson, and D.W. Thomson. Marie Tappin expertly formatted the manuscript through waves of WordPerfect. Charlotte Gray generously critiqued all of my chapters in draft form. She unfailingly asked, “And what news of Mr. Pierce?” and, even more crucially, listened to the answer, often over afternoon tea at Zoe’s at Ottawa’s Chateau Laurier, its marble halls a balm and a refuge. Janet Friskney, expert on the Methodist Book and Publishing House, now at York University, did a stint of invaluable follow-up research for me in the Board of Publication Papers at the United Church Archives. My colleagues at the Pauline Jewett Institute of Women’s and Gender Studies at Carleton University were warm and encouraging, especially its two most recent directors, Virginia Caputo and the stalwart Katharine Kelly. Faculty of Arts and Science Dean John Osborne, himself an art historian, was interested in Pierce and Canadian art history, and the Faculty generously gave a publication grant for the book. Above all, this biography was made possible by the courage and candour of Lorne and Edith Chown Pierce’s two children, Beth Pierce Robinson and the late L. Bruce Pierce – the remarkable offspring of remarkable parents. It is not easy to have a biographer rummaging through your family tree. Beth and Bruce were magnanimous and forthcoming, even when the topic was painful or poignant. Beth’s generosity of spirit has meant much to literary history in so many ways.

Acknowledgments xi

It is not easy to have two writers in a household: accordingly, I want to thank my husband, historian Duncan McDowall, who has shared me with Lorne Pierce for many years. Thanks also to the successive spaniels who slept under my desk – in town and at our cottage, where much of this book was written: Phaedra, Miss Black, McNab, Maud, Paget (who in puppyhood chewed through my computer cord one dramatic day), and Lily. I am grateful to all of those who skilfully shepherded the manuscript through the publication process at McGill-Queen’s University Press, including senior editor Donald Akenson, editors Joan Harcourt and Ryan Van Huijstee, and my patient and gifted copy editor, Curtis Fahey. I am particularly grateful to the Press’s two anonymous readers of the manuscript, who made many helpful suggestions for revision. This project was made possible by a SsHRC Research Grant, awarded while I was teaching as a sessional lecturer with the equivalent of a full-time load in the Department of English, University of Ottawa. Earlier versions of some material in this biography were published in the Journal of Canadian Studies, Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada, and Canadian Poetry, as a book chapter in Canadas of the Mind (McGill-Queen’s University Press 2007), edited by Norman Hillmer and Adam Chapnik, and on the website on Canadian publishing history sponsored by McMaster University, the University of Toronto, and Queen’s University Archives. I am grateful to all of the above for permission to include revised material in the biography, effected through the kind offices of Kerry Cannon, Eli MacLaren, David Bentley, Adrian Galwin, and Carl Spadoni respectively. Sandra Campbell Pike Lake, Ontario April 2012

This page intentionally left blank

Chronolog y

T

his listing includes milestones in the life of Lorne Pierce (hereafter abbreviated as lp ) as well as key publications by him. All titles were published by Ryerson Press unless otherwise indicated. 1864

– Births of Harriet Louise Singleton (14 May) and Edward Albert Pierce (28 June), parents of lp .

1886

– Marriage of Harriet Singleton and Edward Pierce

1890

– Birth of lp in Delta, Ontario (3 August).

1892

(1 March).

– Birth of lp’s sister, Sara, in Delta (27 February).

1904–07 – lp attends Athens High School, then stays at home for a year assisting in the family hardware business as his father recuperates from surgery. 1908–12

– Attends Queen’s University as a member of the Arts 1912

1909/10

– Summer teaching in the west, near Moose Jaw,

1912–14

– lp becomes a ministerial probationer in the Methodist

1914

– Enters the Bachelor of Divinity program at the

1915

– Begins his diary while convalescing in Delta (16 June).

1915–16

class.

Saskatchewan.

Church of Canada, serving in Saskatchewan – at Colonsay, Plunkett, and Fillmore.

Methodist Victoria College, Toronto. Invalided out by Christmas, he is later granted an ad eundem Victoria bd (1917).

– Attends Union Theological Seminary, New York City, on scholarship. With courses at New York University (nyu ),

xiv

Chronology

receives a bd (1916) from Union as well as an nyu ma (1916). 1916

– Marries his former Queen’s classmate Edith Chown

1916–17

– Assistant pastor at St Paul’s Methodist Church, Ottawa,

1917

– Enlists (9 April), ultimately serving in the Queen’s Field

1917–18

– Military Service in Kingston, first on infantry course,

1918–20

– Minister in the eastern Ontario hamlet of Brinston,

1920

– Birth of Elizabeth Louise Pierce to Edith and lp,

(b. 1890) in Kingston, Ontario (19 September).

after ordination in Smiths Falls on 8 June 1916. Symptoms of hearing loss, first noticed when he was a Saskatchewan probationer, become marked. Ambulance after working as a recruiting officer in eastern Ontario. Officiates at Sara’s marriage to his Victoria and Union classmate Rev. Eldred Chester, Delta (12 June). then as acting sergeant major at Ongwanada Military Hospital. Medical discharge from service with suspected tuberculosis (March). serving the three-point rural Matilda Circuit. Becomes known for community projects. Kingston (22 July).

– lp hired as literary critic and adviser for the Ryerson

Press division of the Methodist Book and Publishing House; begins work at the House’s Wesley Building, Queen Street, Toronto, on 3 August.

1921

– Publication of lp’s pamphlet Everett Boyd Jackson Fallis

1922

– Awarded doctorate in systematic theology (std) from

about the death of House Book Steward Samuel Fallis’s son in the First World War. lp ’s disseminated lupus diagnosed about this time.

United Theological College, Montreal, with a thesis on Russian literature (done by correspondence). – Conceives Ryerson’s bicultural Makers of Canadian Literature series. – Co-edits the anthology Our Canadian Literature with poet Albert Durrant Watson.

1923

Chronology xv

– Birth of Edith and lp’s son, Bruce (5 January). – Primitive Methodism and the New Catholicism and Albert Durrant Watson: An Appraisal published.

1924

– Blanche Hume, lp’ s long-time secretary and confidante, comes to work for lp at Ryerson Press ( January). – lp makes textbook sales trip to western Canada. – lp begins to set up Canadiana Collection of books and manuscripts at Queen’s University (later known as the Edith and Lorne Pierce Collection of Canadiana). – lp authors Fifty Years of Public Service: A Life of James L. Hughes (Oxford University Press), Albert Durrant Watson (privately printed), and The Beloved Community.

1925

– Launches the Ryerson Chapbook Poetry series. – Marjorie Pickthall: A Book of Remembrance. – Publishes Frederick Philip Grove’s controversial novel Settlers of the Marsh.

1926

– Death of Albert Durrant Watson (3 May), lp’s friend and

1927

– Begins to personally edit and issue The Ryerson Books

1928

– Awarded Honorary lld by Queen’s University.

mentor. – Elected to the Royal Society of Canada (26 May) after the awarding of the Society’s first Lorne Pierce Medal, donated by lp the previous year. – The Pierces move to 233 Glengrove Avenue from their first Toronto home, 56 Wineva Avenue ( June). – Writes five booklets for Ryerson Canadian History Readers series: John Black, James Evans, John McDougall, Sieur de Maisonneuve, and Thomas Chandler Haliburton. of Prose and Verse, first in a very successful series of textbooks. – In Conference with the Best Minds (Nashville, tn: Cokesbury Press). – An Outline of Canadian Literature (Montreal: Carrier). – Edits William Kirby’s Annals of Niagara, published by Macmillan.

xvi

1929

Chronology

– Death of Edward Pierce, Delta (4 January), during the near-fatal illness of lp ’s son, Bruce. – Death of Bliss Carman (8 June). – Ryerson and Macmillan initiate a highly successful

joint reader series, The Canada Books of Prose and Verse (elementary and high school texts). – Begins publication of The Canadian Treasury Readers (elementary school texts). – Toward the Bonne Entente. – William Kirby: The Portrait of A Tory Loyalist (Macmillan). – Edits The Chronicle of A Century, 1829–1929, The Story of Canada, and the Canadian section of the empire literary anthology The New Countries compiled by Hector Bolitho (London: Jonathan Cape). 1930

– On medical leave from House after collapse from

1931

– New History for Old. – Edits Bliss Carman’s Scrap-Book and Carman’s The Music of

overwork and the pressures of a copyright controversy over one of his textbooks (February–March).

Earth.

1932

– Death of Book Steward Samuel Fallis, who is succeeded by Donald Solandt.

– lp awarded an honorary d.litt by Laval University. – Unexplored Fields of Canadian Literature. 1933

– Three Fredericton Poets.

1934

– lp and Edith move to 5 Campbell Crescent in York Mills

1935

– lp edits The Complete Poems of Francis Sherman and the

1936

– Death of Book Steward Donald Solandt, who is

1937

– Master Builders, lp’s booklet on freemasonry.

(which they christen “La Ferme”) and tour Europe in July and August. poetry anthology Our Canadian Literature (new edition, co-edited with Bliss Carman, who had worked on the poetry section before his death in 1929).

succeeded in June 1937 by Rev. C.H. Dickinson.

Chronology xvii

1938

– lp and his sister, Sara Chester, compile In an Eastern

1938–39

– lp assumes ownership of the magazine The Canadian

1939

– Co-founder of Queen’s Art Foundation. – J.E.H. MacDonald: A Postscript, 1873–1932.

1940

Window: A Book of Days, a tribute to their mother, Harriet Pierce. Bookman.

– Death of Harriet Louise Pierce, Delta (9 January). – Co-founder of Canadian Society for the Deaf (now the Canadian Hearing Society). – Establishes Ryerson Fiction Award.

1942 1943

– Thoreau MacDonald.

– Booklet Jacques De Molay. – The Armoury in Our Halls. – Death of Sir Charles G.D. Roberts (26 November). – Plagued by writers’ cramp and chronic fatigue, lp ceases keeping a diary around this time.

1944 1945

– Queen’s University Art Foundation. – Prime Ministers to the Book. – A Canadian People.

1946

– Member, with his friend Harold Innis, of the United

1947

– Christianity and Culture in Our Time.

1949 1951 1953 1954

Church’s Commission on Christianity and Culture (reported 1950).

– E. Grace Coombs, Artist.

– The Royal Tour in Canada, 1951. – On Publishers and Publishing. – Canada at the Coronation.

– Death of Edith Chown Pierce (23 April) after a four-year battle with breast cancer.

– The House of Ryerson.

xviii

Chronology

– Anthology Canadian Poetry in English (co-edited with Bliss Carman and V.B. Rhodenizer). – Edits The Selected Poems of Bliss Carman. 1955

– lp moves to apartment 309, 49 Glen Elm Avenue, his last

1957

– lp to Caribbean (March). – Edits The Selected Poems of Marjorie Pickthall. – Booklet Memorial Windows: St. George’s United Church

address.

(privately printed).

1958 1959 1960

– Early Glass Houses of Nova Scotia (privately printed). – lp to Caribbean (March).

– lp retires in January as general editor of Ryerson Press. – lp in Mexico (March). – A Canadian Nation.

1961

– lp dies of lupus-related heart disease, Toronto (27

1970

– Sale of Ryerson Press to McGraw-Hill Canada by the

November) and is interred beside his wife, Edith, in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, Toronto.

United Church of Canada.

Both Hands

This page intentionally left blank

Introduction

The problems of publishing in this country are economic ones, but the importance of publishing in the life of Canada is cultural before it is anything. Ontario Royal Commission on Canadian Publishers and Canadian Publishing, 19711

No one involved in the production or reception of literary texts – from the writer to publisher to bookseller to reader – is free of the boundaries that get drawn by editors in privileged positions. Canadian writer Roy Miki 2

N

ear the end of his long and illustrious career as editor of Ryerson Press, Lorne Pierce summed up the sense of mission that had always driven him. His editorial desk, he declared in a letter to a prospective successor, was “a sort of altar at which I serve … as one very much concerned about the entire cultural life of Canada.” His mission, he believed, was one of “planning a high destiny for our people” – with French-English entente always in view. Pierce was frank about the power of the post and about his commitment to his self-appointed mission. He emphasized to his prospective successor: “You would choose the spokesmen and interpreters best equipped to write for you. You would look back as I now do, and thank God that this power was placed in your hands for so much good.”3 Dramatic words. Canadians need to understand better the influential figure who wrote them. Scholar Maria Tippett has emphasized that “culture is made as much by the critics and the scholars who write about it, the galleries who collect and exhibit it, and the patrons who buy it, as by the artists themselves.”4 Tippett was writing about Canadian art, but her insight also illuminates the crucial role of the country’s editors and publishers in the shaping of Canadian book culture from its beginnings to the present, a power emphasized in the two quotations that begin this Introduction.

4

BOTH HANDS

As Roy Miki so vividly phrases it, in the production and reception of literary texts, no one is free of the boundaries that get drawn by editors in privileged positions. However, as the Ontario royal commission on Canadian publishing pointed out, the role of Canadian publishers in shaping Canada’s culture has in fact been little appreciated – and, until recently, even less analyzed. That is to say, the men (and usually they have been men) who have been major players in Canadian publishing have not to date received scholarly attention commensurate with their importance, for better and for worse. Lorne Pierce (1890–1961), unquestionably one of the most influential publishers in Canadian literary history, is no exception. Pierce, from 1920 to 1960 editor of Ryerson Press, a division of the United Church Publishing House (before 1925 the Methodist Book and Publishing House), was Canada’s leading publisher for four decades. Contemporaries recognized his importance. Historian Donald Creighton characterized Ryerson Press under Pierce as one of the most important Canadian publishing companies active between the two world wars and beyond. Creighton observed: “Ryerson Press [was] … the very liberal and catholic descendant of the old Methodist Book and Publishing House … [its] chief editor, Lorne Pierce, was a man of strongly independent views and wide sympathies.”5 Yet today, almost four decades after Creighton’s provocative verdict, few Canadians remember Lorne Pierce. Not many even recognize the name of Ryerson Press. Moreover, Pierce has received little attention from Canadian literary historians, despite honourable exceptions in the work of scholars George L. Parker, Janet Friskney, Laura Groening, and a few others. In other words, time has clouded our cultural memory. As Pierce himself ruefully observed, “time … dims, and gives everything a feathery edge.”6 Even in works devoted to the book trade, Pierce is often sketched as a more simplistic figure, or a more grandiose one, than he really was – often both at once. In The Perilous Trade: Publishing Canada’s Writers (2003), for example, Roy MacSkimming’s history of the Canadian book trade during the post-1960 period, the evidence presented suggests that, some fifty years after Pierce’s death, his image has been distorted into stereotype. For example, MacSkimming writes that Jack McClelland, Pierce’s younger competitor in the 1950s, damned Pierce with faint praise: “[Pierce’s] successor a generation later in promotional zeal, Jack McClelland, remembered Pierce as ‘a sort of wild, strange fellow’ who ‘always seemed to be in a hurry’ but was ‘a very good publisher.’”7

Introduction 5

McClelland’s appraisal, made in an interview decades after Pierce’s death, offers a construct of Lorne Pierce – not for the first time by any means in modernist and postmodernist chronicles – as a hyperactive and uncritically patriotic church publisher. In other words, Pierce as a publisher was, as MacSkimming puts it, a “Methodist scholar with [five] university degrees,” an earnest man of the cloth. The Perilous Trade touches upon Pierce’s career in the course of an analysis whose main focus is the post-1960 publishing scene, which, it is emphasized, was a more libidinous and sophisticated age. MacSkimming writes of forerunner Pierce: “Pierce nurtured a notion called Canadian literature. He published copious amounts of it, commissioned critical studies of it, edited school readers bursting with it, and wrote, lectured, and pamphleteered about it. There was an evangelical industry about the man.”8 Happily, MacSkimming chooses exactly the right quote from Pierce himself to crystallize Pierce’s significance. Looking back at his career, Pierce situated himself as a major cultural nationalist, an ardent patriot with ideals similar to those of two of his major Canadian publishing contemporaries, John McClelland (1877–1968) of McClelland and Stewart and Hugh Eayrs (1894–1940), long-time president of Macmillan of Canada. Pierce recalled the orientation of this de facto triumvirate during the 1920s, the first decade of his Ryerson editorial career: “We were at the beginnings of things as a nation and we felt under obligation to assist as many spokesmen of our time as we could … It was simply that a birth, and then possibly a rebirth, of Canadian letters had to begin somewhere, and it might as well begin with us.”9 This biography of Pierce examines his life and work. Its title, Both Hands, is taken from Pierce’s favourite complimentary closing in letters to kindred spirits in Canadian cultural nationalism, a sign-off adopted from the correspondence of William Withrow, his eminent nineteenthcentury predecessor at the Methodist Book and Publishing House (hereafter “the House”). The “both hands” image captures Pierce’s unstinting energy and heartfelt (dare one say “two-fisted”?) enthusiasm for cultural nation making throughout his editorial career. Nevertheless, this biography is mindful – like all responsible biography – of the variable degree to which posterity can and cannot accept its subject at his own estimate, or that of his friends and rivals. Pierce was both a product of and a maker of his era in Canada, a duality this study addresses by studying the social and cultural forces that shaped Pierce’s values both inside and outside the publishing world.

6

BOTH HANDS

The value-shaping contexts of Pierce’s seventy-one years of life began with his staunchly Methodist upbringing in the eastern Ontario hamlet of Delta and his secondary education in the nearby village of Athens. Pierce’s post-secondary education was formidable, especially for the day: he obtained degrees from Kingston’s Queen’s University (ba , 1913), Toronto’s Victoria College (bd , 1917), New York City’s Union Theological Seminary (bd , 1916) and New York University (ma , 1916), and Montreal’s United Theological Seminary (std , 1922). He was ordained into the Methodist ministry in 1916 after circuit riding as a ministerial probationer in pioneer Saskatchewan on the eve of the First World War. His wartime military service was bracketed by urban and rural Ontario pulpits before he changed careers to spend forty years in the editorial chair at Ryerson Press. In this biography, the image Pierce projected of himself as an impassioned cultural nationalist will be both qualified and deconstructed. There can be no doubt of the importance of Pierce’s work as editor and publisher, a field in which he won prominence as the influential proponent of a certain very particular version of Canadian cultural nationalism – an idealistic, bicultural, whiggish, assimilative, and dynamic nationalism rooted in elements of Methodism and the idealism of Queen’s University philosopher John Watson. Moreover, in terms of both reach and longevity, Lorne Pierce was unquestionably primus inter pares among such publishing contemporaries as Hugh Eayrs and John McClelland. For one thing, unlike either of the latter, Pierce consistently functioned as a hands-on book editor throughout his career, personally editing scores of seminal Ryerson publications – many with a nationalist agenda.10 He also personally developed and edited hugely successfully elementary and high school readers, series that dominated the English textbook market for over three decades from about 1930, perhaps his most overlooked major achievement as a cultural nationalist. Additionally, Pierce published and championed Canadian writers and artists, including Harold Innis, C.W. Jefferys, the early E.J. Pratt, Donald Creighton, J.E.H. MacDonald, and many others, thereby indelibly shaping the book and art culture of his times. Of course, publishers like Eayrs and the McClellands, father and son, also championed Canadian writers. Yet, in his Ryerson career, Pierce differed from his peers in another important respect, one that makes him an even more significant cultural figure of mid-twentieth-century Canada. Pierce never functioned as the administrative head of his publishing

Introduction 7

house; this role was filled by the book steward (during Pierce’s tenure, the reverends Samuel Wesley Fallis, Donald Solandt, and C.H. Dickinson successively). As a result, he was able to devote himself more intensively to the literary/intellectual aspect of publishing in a way that his peers at other publishing concerns could not. Pierce began his editorial career in 1920 resolved, as he confided to his diary, to take on the “real he-man’s task” of making Ryerson Press “the cultural mecca of Canada.”11 Pierce faced daunting challenges, however. The story of his life is also the story of his relentless adult struggle against the depredations of disseminated lupus and of profound hearing loss. Lupus meant Pierce battled lung infections, exhaustion, heart disease, joint pain, and other ailments throughout his career, periodically collapsing from illness and overwork. His deafness limited his ability to socialize and give speeches, networking activities that are usually key to a publisher’s success. Especially in light of his health challenges, Pierce’s editorial energies were prodigious. But his achievements were costly in terms of both his wellbeing and his family life, as his colleagues, as well as his wife, Edith Chown Pierce (1890–1954), and their two children were well aware. Pierce differed from his contemporaries in publishing in another respect. Unlike Eayrs and the McClellands, Pierce himself was a prolific author. During his Ryerson career, he was the author of a score of biographies and monographs, including works on poet Marjorie Pickthall and novelist William Kirby as well as an influential early (1927) study of Canadian literature and a spate of booklets on Canadian nationalism. Uniquely, he became well known as an advocate and critic of Canadian nationalism in the period 1920 to 1960 as both author and publisher. Above all, for forty years, Lorne Pierce shaped the book lists of Ryerson Press according to his vision of Canadian literature and culture. Moreover, the House was throughout Pierce’s tenure Canada’s largest publisher, and the only one with an in-house printing and production plant. Thanks to such a platform, Pierce speedily became a powerful and influential Canadian cultural figure. Moreover, whatever the liabilities for Pierce and Ryerson Press of being part of a church publishing house (for example, a prim public image, and the requirement to print in-house, often economically disadvantageous), the benefits of Ryerson’s status as part of the publishing arm of a large and prosperous church were considerable. Pierce enjoyed a blend of security and autonomy as publisher that free-standing rivals like McClelland and Stewart or branch-plant operations like Macmillan of Canada

8

BOTH HANDS

lacked. Thanks to church backing and informal cross-subsidization made possible by his own successful textbook series, Pierce orchestrated the country’s largest Canadian trade book lists during his career. From the creation of the imprint in 1919, “The Ryerson Press” (as it was formally designated on the title page of Ryerson publications) formed part of a large printing and publishing operation. Located within the so-called trade division of the House, Ryerson Press, with Pierce as its general editor, published the House’s original Canadian imprints, that is, both educational and mass-market books written and edited in Canada. Undoubtedly, compared to the large volume of agency titles for which the House imported or printed Canadian editions under the Ryerson imprint (an area that was never Pierce’s responsibility), the proportion of Ryerson’s original Canadian titles to the total number of books issued by the House was small (about 10 per cent). However, the influence of that list in the small Canadian book world was disproportionately large. (By the 1940s, a Canadian novel might sell on average about 2,500 copies, a best-seller about 5,000 copies.12) Overall, for most of its existence, Ryerson Press was identified with Lorne Pierce, and vice versa. In 1920 Pierce was recruited from a rural pastorate in eastern Ontario to be the Press’s “Literary Critic and Advisor” (he was formally named editor in 1922), a year after “The Ryerson Press” imprint was created by House Book Steward Samuel Fallis.13 Pierce’s arrival almost coincided with Ryerson’s creation and it did not long survive him. In 1970, amid nationalist controversy, the United Church of Canada sold Ryerson to the Canadian subsidiary of American publisher McGraw-Hill. Ryerson Press effectively disappeared, but for forty years Pierce had done much to make it a major force in Canadian publishing. Given Pierce’s major importance as publisher of Canadian books, an understanding of his life – boyhood, education, early experiences, and literary career – is vital to understanding the evolution of Canadian culture in the period 1920 to 1960. His values shaped Ryerson’s policies and influenced its authors and publications through a blend of editorial and personal power. A biography of Pierce is therefore needed. The charismatic, eloquent, well-dressed man so long seated in the editor’s chair, disarmingly fiddling with his hearing aid and wittily satirizing his own Irish heritage or his “Continuing Methodism,” has become in the twenty-first century an éminence grise. We need to turn up the lights and examine what manner of man Lorne Pierce was and how he helped shape key parts of Can-

Introduction 9

adian culture during the Roaring Twenties, the Depression of the 1930s, the Second World War, and the 1950s, as well as two successive waves of cultural modernism from the 1920s to the 1960s. How do questions of class, gender, ethnicity, race, and historical moment figure in the life of Lorne Pierce, in his publishing policies and loyalties, and in his relations with readers and authors? How did Pierce’s beliefs and policies shape the making of the Canadian literary canon between the First World War and the beginning of the 1960s, a period that embraced the first and second waves of modernism in Canada? Both Hands addresses these important questions. To do so, it examines Pierce’s life and values, and analyses the background, impact, and career of a man whose ideological involvement with Canadian literature, art, publishing, and education played a key role in fostering the strong sense of cultural nationalism that emerged in English-speaking Canada between the First World War and the 1967 Centennial of Confederation. Lorne Pierce’s life and values were in fact shaped by several major factors: the spiritual and ethical training inculcated by his parents, Edward and Harriet Pierce (especially his mother), in particular their zealous Methodist faith, which he absorbed during an eastern Ontario village boyhood at the beginning of the twentieth century. He was also shaped by the freemasonry into which he was initiated by his father on the eve of the First World War. For Pierce father and son, the Masonic brotherhood constituted a fraternal organization which emphasized moral idealism and community involvement, one rooted in white Protestant male solidarity. Pierce also absorbed the nationalism and idealism that infused the Queen’s University undergraduate arts program in the early twentieth century. That dynamic set of values was reinforced in his struggles as student teacher and Methodist probationer to effect social cohesion via the establishment of churches and schools amid the immigrant polyglot of the Saskatchewan prairie before the Great War. Pierce’s outlook was also shaped by the ecumenism and excitement of his 1915–16 studies at New York City’s Union Theological Seminary, as well as by the rigours – present to some degree even on the home front, where he served – of military service during the First World War. Pierce was both haunted and inspired by Canada’s role in the war, including the legacy of the Battle of Vimy Ridge, where he lost a beloved cousin in a battle which, like many of his contemporaries, he came to see as seminal to the forging of Canadian national consciousness. Furthermore, Pierce’s ordination to the Methodist ministry in 1916 imbued him with a sense of

10

BOTH HANDS

mission and “set-apartness” which never left him, even when he turned from the active ministry to a crusade in Canadian publishing at Ryerson Press. He was convinced, as he told one correspondent, that his editorial work “extend[ed] [my] mission as an ordained man beyond anything you can imagine.”14 The Toronto of the 1920s – the era when Pierce arrived to take up his post in the House’s imposing red brick headquarters on Queen Street – resonated with currents of theosophy as well as with the cultural nationalism of the Group of Seven. Both ideologies animated circles in which Pierce moved, for example, the Arts and Letters Club. Pierce’s involvement with poet and physician Albert Durrant Watson and with Group of Seven member J.E.H. MacDonald – both leading theosophists and nationalists – helped inspire his early patriotic publishing ventures like the landmark Makers of Canadian Literature series of the 1920s. All of these forces, physical, spiritual, and intellectual, animated Pierce’s policies as publisher. In a similar manner, his family life – graced by the devotion of his wife, Edith, who functioned as an “angel in the house” wife and mother while Pierce relentlessly toiled for success as editor and cultural nationalist – is intertwined with his mission in the publishing world. Pierce himself recognized this link, writing in 1956 (not without guilt) at the end of his official account of his years at Ryerson Press: “Every decision made from 1916 on, every major move of any sort, and all my work of every description owes so much to the inspiration, wisdom and loyalty of my wife, that she must be regarded as a silent partner in everything done or attempted. I owe more than I can say to the mind and heart, the affection and devotion, the integrity and stamina and vision of Edith Chown Pierce.”15 Of course, the relationship between Pierce’s career and his family was even more complex than that. For example, Pierce’s mother’s idealism and boundless ambition for him fostered her son’s relentless drive, while his wife’s domestic and social skills made it possible for him to devote his energies to his career to an astonishing degree. Arguably, a detailed appreciation of Pierce’s commitments – to country, to church, to family, to freemasonry, to alma mater – are vital to an understanding of his achievements as editor and publisher. It is necessary to assess where Lorne Pierce triumphed and where he fell short in his goals and ideals, as every human being inescapably does. Pierce himself understood the importance of biography to an understanding of

Introduction 11

human endeavour and cultural genesis. As he put it, biography “sums up an age for you … [its] atmosphere [and] standards.”16 In fact, Pierce himself assembled and donated the comprehensive collection of documents which makes the writing of a full biography possible. The rich and voluminous Lorne Pierce Papers at Queen’s University Archives – most deposited by Pierce himself – includes extensive records relating to his family, his education, his career, his associations, his friendships, and his own writing and editing projects. The Lorne Pierce Papers and related collections encompass dozens of boxes of diaries, personal and business correspondence, manuscripts, speeches, sermons, articles, books, photographs, scrapbooks, memorabilia, and other material. Such a formidable trove has been both a blessing and a burden for this biographer. The archival bounty is rich, but, given its bulk, it is not surprising that earlier would-be biographers found it too daunting. The biography of a pack-rat workaholic publisher with a finger in every Canadian cultural pie over four decades is a challenge to research and write. A Pierce biography is a prospect the subject himself viewed with ambivalence. At the end of his life, troubled by how, in his view, he had neglected the emotional needs of his family in favour of his career, Pierce declared that he wanted no biography to be written.17 But, with the subtlety and ingenuousness so typical of him (qualities beautifully captured in the Wyndham Lewis pastel portrait18), he made sure to preserve extensive records of his life and work, perhaps the most complete we have for any cultural figure in Canadian history. He apparently destroyed little (though he did have his former assistant Blanche Hume go through all his correspondence before it was sent to Queen’s19). Thus, even as he protested that no biography should be written, Pierce secured for posterity a comprehensive and tantalizing record of a major career in Canadian letters. Accordingly, this biography – made possible by the gracious and unstinting cooperation of Lorne and Edith Pierce’s daughter, Beth Pierce Robinson, and their son, the late L. Bruce Pierce – delves into Pierce’s life and work, analyzing the light and shadow of a major Canadian life in the context of the cultural and social milieu of the day. Of course, responsibility for the portrait penned here is mine alone. Pierce’s life records and the vast Edith and Lorne Pierce Collection of Canadiana housed at Queen’s in fact constitute an important gift to

12

BOTH HANDS

posterity as a record of the literary and publishing scene in Canada, the more so because, until recently, Canadian publishing history has been a sadly anaemic field. During the last decade, with the publication of the weighty three-volume History of the Book in Canada, completed in 2007, and Roy MacSkimming’s Perilous Trade, our picture of Canadian publishing has been fleshed out somewhat, building on George L. Parker’s seminal The Beginnings of the Book Trade in Canada (1985) as well as material in The Literary History of Canada (1965) and the background papers prepared for the Ontario Royal Commission on Canadian Publishers and Canadian Publishing in the early 1970s. Valuable studies by such scholars as Carl Spadoni, Bruce Whiteman, Ruth Panofsky, Janet Friskney, Jack King, Michael Gnarowski, Carole Gerson, and others in the last two decades have also helped illuminate the world of Canadian publishing, as have memoirs by such key figures in the book trade as Jack Gray, head of Macmillan of Canada from 1946 to 1973, and Marsh Jeanneret, head of University of Toronto Press from 1953 to 1977.20 However, the aforementioned books, articles, and memoirs relating to Canadian publishing are still only nebulae in a dark sky. We have few studies of major Canadian publishing companies, and even fewer biographies of publishers. For one thing, the relevant records, despite the joys of publishing-related collections such as those at Queen’s and McMaster universities, tend to be either dauntingly voluminous or frustratingly absent. Moreover, to the extent that Canadian scholars have devoted attention to our writing culture, we have understandably, until recent years, tended to focus on the publishing history of individual writers rather than on the editors and publishers who make publication possible and whose tastes and priorities have so greatly affected the shaping of the Canadian literary canon. However, in a country where book publishing has always faced both the formidable supply and marketing challenges attendant on great geographical size and scattered population and same-language foreign competition from two imperial anglophone cultures (Britain and especially the United States), the role of a relatively small number of Canadian editors and publishers has been crucial. The roster includes, in the nineteenth century, John Lovell of Montreal and the Reverend Egerton Ryerson of Toronto’s Methodist Book and Publishing House, as well as, at the turn of the twentieth century, William Briggs of the Methodist Book and Publishing House and, a little later, John McClelland and his contemporaries, Samuel Gundy of Oxford University Press and Hugh

Introduction 13

Eayrs and John Gray of Macmillan of Canada. Pierce is one of this pantheon of influential publishers. Whether planning a nationalistic art or literature series, or bending over books of illustrations of Canadian art with C.W. Jefferys or Thoreau MacDonald, or scheming with Harold Innis to publish seminal Canadian historical works by Innis, Donald Creighton, or Arthur Lower, or debating with E.J. Pratt, Northrop Frye, E.K. Brown, or Earle Birney over literary manuscripts, Lorne Pierce was a seminal figure over forty years of Canadian cultural publishing. Not only that, Pierce’s own elementary and high school textbooks, best-sellers in Canadian schools from the late 1920s to the 1960s, laid the groundwork for the explosion of interest in Canadian culture in the mid-twentieth century. Lorne Pierce was thus inescapably a “Maker of Canada,” the creator and promoter of a potent construct of the nation. He acted on the basis of mid-twentieth-century conceptions of nation, gender, ethnicity, and class, ones that exalted a Protestant male construct of nation which valorized French-English entente and immigrant assimilation to a precisely defined national ideal. Pierce’s life and work constitute a key thread in the shaping of the culture of twentieth-century Canada. Providing answers to how, why, and to what end Lorne Pierce became such a key figure in our cultural history lies at the heart of this biography. He – and the country – deserve no less.

1 Lorne, Mother, and Methodism Delta, Athens, and Off to Queen’s, 1890–1908 Lorne’s first words were “mother” and “Jesus” and at eighteen months … Lorne began to preach. Harriet Pierce, early 1892, childhood journal kept for her son1

[A mother’s love] never loses its faith, never loses sight of a child’s perfectability.

Lorne Pierce, in an article about mothers for the Christian Guardian, 10 May 1922, inscribed “For my Mother” in his clipping book

I

n the eastern Ontario village of Delta, on gables and eaves atop the rosy brick of the old buildings, sheets of patterned tin siding sold by Edward Pierce’s hardware business still gleam in the sun. The sheeting was installed long ago, some of it by the merchant’s son Lorne well before the First World War. The former storefront of the Pierce hardware business, which the elder Pierce sold to his neighbour Austin Sweet in 1923 – its handsome facade and white-framed windows little altered, although the premises are shabby now – can still be seen. The storefront is part of the most substantial commercial edifice on Delta’s winding Main Street – the two-storey brick Jubilee Business Block, erected in 1897.2 Delta lies in the verdant, rolling mixed farmland of Leeds County, along the St Lawrence River just northwest of Brockville – in the former Bastard Township (now part of Rideau Lakes Township). Lithographs of Queen Victoria and other long-dead worthies still look down sombrely from the walls of the meeting room of Delta’s town hall,3 beneath the pressed tin ceiling of the room. Nearby lies a brace of churches and the substantial old stone grist mill, now a museum. During

Lorne, Mother, and Methodism 15

Lorne Pierce’s boyhood in the 1890s, the mill machinery filled the gravel streets of the village with humming. Not far away is the red-brick Methodist church – since 1925, Delta United Church – the centre of spiritual and social life for Lorne Pierce’s mother, Harriet Singleton Pierce, and her family from the 1880s.4 Stained-glass windows, pulpit, and communion table, all the gift of Lorne and his sister, Sara, in honour of their parents, grace the interior of the present structure, which dates from 1888–89. Beyond Delta’s meandering Main Street is Lower Beverley Lake, where Lorne Pierce summered all his life. On Main Street, a creek a stone’s throw wide once flowed beneath a solid stone bridge, connecting Upper and Lower Beverley Lake and turning the old mill wheel. The swampy upper lake was actually created by the dam for the grist mill. The dam flooded 2,000 acres above the town in 1815: hence the name Delta for a settlement first called Stevenstown by its Vermont pioneers, then Stone Mills (1807) and Beverly (1823).5 In summer, the village can still suggest a sunshine sketch of late-nineteenth-century Ontario reminiscent of Stephen Leacock’s Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town (1912).6 The Mariposa air of Delta is augmented by a frame grandstand at the old dirt racetrack on the village fairgrounds – its venerable wooden buildings still home to one of Ontario’s oldest country fairs, founded in the 1830s. Late in Queen Victoria’s reign and into Edward VII’s, the Delta Fair, with its horseracing and drinking, was anathema to Methodist wives and mothers like Harriet Pierce. At the close of the nineteenth century, Delta was a hamlet of about five hundred people, in an area with an economy based on mixed farming, cheese and maple-syrup production, and lumbering. Its heyday as a bustling hamlet with tanneries, a working grist mill, and a small foundry was slowly coming to an end. Its modest pretensions (for it had no high school) were soon to be further eclipsed by the advent of the automobile and the economic synergy of the more dominant farming centre of Athens to the east and the nearby county seat of Brockville, a rail and water centre on the St Lawrence. But, in the 1890s, Delta was one of those well-rooted, distinctly defined villages that were the pride of late-nineteenth-century Ontario, even if the flow of migration to the opening west from the played-out farmland of eastern Ontario was underway. In adult life, Lorne Pierce, Delta’s most famous son, never forgot either its homogenous sense of community or the attendant narrowness.

16

BOTH HANDS

Edward Pierce and his wife, Harriet Singleton Pierce, not long after their marriage in 1886. Courtesy of Beth Pierce Robinson

He returned regularly to the “quaint hamlet” to visit his parents and to holiday at the cottage.7 But, after both of his parents were dead, Pierce evoked Delta’s more repressive aspects, wryly labelling it “Sleepy Hollow immersed in [both] pious Victorianism” and “embalmed Puritanism.”8 Lorne Pierce was born in Delta on 3 August 1890. Delta and his family shaped him in important ways. There his mother and father gave him a particular sense of community, a distinct identity, a sense of the nation, and a strong spiritual faith. Above all, his upbringing instilled in him a drive and work ethic that formed the nucleus of his being. That drive was at once his blessing and his curse, and the engine of his future contributions to the culture of Canada as editor and man of letters.

In Delta, the respectable red-brick house trimmed in dark-painted

wood on Mathew Street where Lorne Pierce was born is just a short stroll from Main Street. Lorne was the elder of two children born to Edward Albert Pierce (1864–1929) and his wife Harriet Louise Singleton (1864–1940). Both parents came from large families with strong roots in eastern Ontario, roots put down by sets of grandparents from Ireland’s County Wexford who had settled in Leeds County early in the nine-

Lorne, Mother, and Methodism 17

teenth century. Born on 28 June 1864, three years before Confederation, Edward Pierce had grown up some thirteen miles west of Delta, in the hamlet of Newboro, a lock station on the Rideau Canal about halfway between Ottawa and Kingston. Harriet Singleton was born on 14 May of the same year to John Singleton and his wife, Sara Donahue. Hattie, as she was nicknamed, was the youngest of a large family. She grew up a couple of miles away from her future husband – just outside Forfar near the crossroads at Crosby – then called Singleton’s Corners. At the crossroads, one can turn toward Ottawa, Brockville, Kingston, or Westport – and on the Brockville Road lies Delta, a lesser centre, some ten miles away, just west of the village of Athens. John Singleton had an ample home for his large family, one of Upper Canada’s classic Georgian stone farmhouses. Such a dwelling was in the 1860s the pride of a wellestablished farmer of the second generation of Irish settlers. The Singleton house (which still stands) was set in the rolling fields around Crosby, shaded by an elm or two, with an ample verandah. There were many relatives to welcome to its wide rooms. Little Hattie had two Singleton uncles who had similar stone houses nearby. Her father and her mother, who was John Singleton’s second wife, nurtured their large brood of fifteen children (Hattie’s nine half-siblings and five full siblings) with ample servings of farm produce and Methodism. Both John and Sara Singleton were staunch Methodists – leaders in a congregation that also numbered Edward Pierce’s family – and usually boarded the minister. John Singleton was a powerful personality, a contrast to his more reserved, refined, and high-minded wife. Lorne remembered his grandfather vividly, writing in his diary: “He was a short, thick set Irishman, rosy face, blue eyes, ready wit. A great Bible student, [he] made phrenology [a craze of the day] his hobby, boasted that he could throw any man in the county, had tossed every minister on the circuit over his shoulder … Each of his children he saw well established, each son with a farm.”9 Harriet’s mother, Sara Singleton – Lorne’s lone grandparent with Scottish blood in this Hibernian family tree – was dignified and, Lorne remembered, “quiet yet at times very jolly. Her presence was a benediction. Falsehood could not exist in her presence, sham shunned. Her church was her home, her home a sanctuary … My mother [Harriet] was the nearest like her of all her children.” Harriet Pierce’s behaviour in married life was to suggest, however, that she combined her mother’s devoutness and dignity with her father’s dynamism. She had an interest in

18

BOTH HANDS

moulding character that left her father’s phrenology far behind. Rather than feel her children’s skulls for clues to their destiny, she implanted her values in their skulls for the same purpose. (For his part, phrenologist Grandfather Singleton loftily assured young Lorne that he had the “mouth of an orator” and “the nose of a general or a bishop.”10) A web of Singletons and Pierces had settled throughout eastern Ontario by the late nineteenth century. It was a family tree that Lorne Pierce later exuberantly, if with slight exaggeration, described as “all Irish – four generations untainted.”11 His overwhelmingly Irish heritage was to be ideologically significant to him as a publisher in a country whose anglophone culture often tended to kowtow to the British tradition or to be framed in terms of the Loyalist myth. (In 1932, in Toronto, when asked by a snobbish interviewer about his ancestry, Pierce startled her by chortling: “Irish, thank God.”12) Lorne Pierce grew up on the margins of Loyalist myths and ideologies and usually viewed them skeptically (Loyalism was strong among the numerous “u .e .l .” descendants of Leeds County). Instead, he was weaned on great draughts of John Wesley, a dash of John Ruskin, and a generous dollop of the cultural glories of Ireland. For her part, as she matured in a newly created and expanding Canada, Harriet Singleton displayed a wit and verve that bespoke her Irish ancestry, qualities she was to pass on to her son. Lorne found her tales of her maternal grandfather, Thomas Singleton, secretary to an Anglo-Irish baronet, whatever their accuracy, especially spellbinding. The latter had allegedly eloped to the bush of British North America about 1817 with Sarah Anne Butler, his pupil and the daughter of Sir Pierce Butler.13 The first church built at Singleton’s Corners had been a Methodist Church, and scores of Harriet Pierce’s letters (she wrote two letters a week to each of her children for over a generation14) attest that the little girl’s mind and soul had been shaped for life in that first frame church.15 Edward and Harriet Pierce – Ed and Hattie, as their circle called them – knew each other all their lives, growing up as they did in adjoining hamlets (Newboro was the post office for Singleton’s Corners until 1890).16 Both families attended the little Methodist church at Crosby. In fact, Harriet Singleton’s older sister Lucinda lived in Newboro after her marriage – to Ed Pierce’s brother John.17 Ed and Hattie Pierce were married in Crosby’s wood-frame Methodist Church on 1 March 1886 (they now rest side by side in its cemetery). Their married life began in

Lorne, Mother, and Methodism 19

neighbouring Delta, a village close enough to Crosby that the nearby Canadian National Railways station at Forfar served both Crosby and Delta. By the time he chose a wife, Ed Pierce had begun to establish himself in Delta as a hardware and tin merchant – a business bought from William Singleton, a connection of his future wife’s – and as a pillar of Delta Methodist Church.18 The proud husband brought his bride there after their wedding trip to Niagara Falls, already a popular honeymoon destination.19 When the minister, the Reverend William Barnett, looked out at the congregation on the Sunday the Pierces made their debut as newlyweds, his glance might have lingered on bride and groom. He would already have taken twenty-two-year-old Ed Pierce’s measure – reliable, devout, quiet, upright, yet with a twinkle in his hazel eyes. A man of “infinite patience, sweet temper and few words,”20 Ed Pierce was known as a good businessman, stalwart member of the Masonic Order, and staunch Conservative, a merchant coping with the financial uncertainties and nerve-wracking business cycles which were the lot of a village businessman in late-nineteenth-century Ontario. A good citizen as well as a good Methodist, Ed Pierce also played in the town band.21 Calm, fair-skinned, and handsome in a quiet way, he had already displayed thrift, probity, and sobriety in the course of building a business and selecting a wife. Certainly, Ed Pierce was representative of the aspiring middle-class Methodists whom the church sought to serve in the Ontario of the day. Moreover, Delta was in the heart of an area where “flatout” Methodism camp meetings with dramatic conversion experiences attended by struggling pioneers in the semi-wilderness were becoming a memory as Methodism adapted itself to the emerging middle classes and vice versa.22 For her part, Mrs Barnett, the minister’s wife, might have been struck by the diminutive frame, upright carriage, and determined air of twentytwo-year-old Hattie Pierce. The new bride was black-eyed, dark-haired, vivacious, intelligent, principled, religious, artistic, and bookish. She was speedily to prove a power to be reckoned with in Delta. In fact, were it not for the restrictions of gender in the spheres of education and vocation, restrictions that channelled a woman’s life in late-nineteenthcentury Canada, Hattie Pierce might well have been in the pulpit in a Methodist church that spring day. If Delta had something of the torpor

20

BOTH HANDS

of Washington Irving’s fictional Sleepy Hollow, as Lorne Pierce came to believe, there was certainly nothing sleepy about Harriet Singleton Pierce or the home that she created. By the time Hattie Pierce’s three-month-old son was christened Lorne Albert Pierce by the Reverend William Rilance in Delta Methodist Church in 1890,23 the force of his mother’s personality and principles had touched not only her home but also her church and village. She played the organ for services, led the choir, and was prominent in the Sunday School where she and her husband taught. She was also a leading figure in other activities: the Epworth League (a Methodist youth group) and the Temperance Society. In the village, she was known to Methodists, Baptists, a Catholic or two, and the odd non-believer alike for charitable works. She was a friendly and capable presence behind the counter in the Pierce store when her other duties permitted. By the time Lorne’s sister was born in February 1892, Mrs Pierce was widely respected (and a little feared) as one of Delta’s most active Methodist matrons. Mind you, certain Delta residents also remarked that there was a “highfalutin” side to Mrs Pierce. Lorne and Sara were allowed to play only with certain children, principally those of the minister and the doctor.24 Some mused that it was a pity that such a dynamic and religious woman as Mrs Pierce, who brooked no gossip in her house during her frequent musical, church, and temperance gatherings, was hard of hearing, in later life having to use an ear trumpet. Her good friends, such as her fellow church worker Stella Cheetham Green,25 were apt to cluck their tongues sympathetically when Hattie had one of her dreadful migraines. (Her son was to inherit both the migraines and the deafness.) Mrs Pierce had not just banned gossip. In addition, no dancing or card playing (“the devil’s picture book”) were allowed in this pious household. The parlour bookshelves, while full, held no plays at all – not even Shakespeare’s – and only the most high-minded fiction. Dun‑coloured volumes of fiction reviewed in the Christian Guardian, the redoubtable magazine of Canadian Methodism, rubbed shoulders with Sunday School staples of the time like Elsie Dinsmore and Pilgrim’s Progress.26 Delta children (the select few allowed in the house) knew that the pressed-glass tumblers in the Pierce kitchen never held even ginger ale. Mrs Pierce believed that the name of that ostensibly innocuous beverage was too reminiscent of alcohol to allow it in her house.27 But visiting children soon forgot to pine for ginger ale when Mrs Pierce, charismatic and a born teacher, declared, “I think you’ll like this,”28 and began to

Lorne, Mother, and Methodism 21

play a song on the keyboard or tell a story with her droll Irish wit. Her volumes of Scripture and Ruskin lay close at hand, as did her sheets of hymn tunes and classical music for the organ (later a piano). Long after, one little girl recalled her influence: “Lorne’s mother was an important teacher in my life. My first memory was a group of three very small children in our living room, Lorne, [Sara], and my very little self – We had been seated quietly, about our organ – and she played – ‘The Battle of Waterloo’ – telling us the parts as advanced in the music – I can still hear her say – ‘Lamentation.’”29 Needless to say, a cradle rocked by Hattie Pierce had a lot of momentum. Lorne was programmed by his mother to be not simply a good person and a good Methodist but an outstanding Methodist minister. From the moment she proudly placed the infant Lorne in his willow cradle lined with pink cambric, she never lost sight of this goal, although there appears to have been more than one occasion when her son himself wanted to. At his birth, Hattie began to write a journal for him, an inspirational record which she kept up-to-date until she presented it to him on his fifteenth birthday, 3 August 1905. In later life, Lorne Pierce referred to this journal, not without irony, as “mother’s love tale of [my] early years.”30 The journal confirms that Hattie was a paradigm of the turn-of-the-century Methodist mother.

Because Lorne ’s childhood was so interwoven with the Methodism

his mother embodied and his father embraced, it is necessary to set forth briefly the nature of the religion he experienced as a child through the prism of the journal Hattie kept for her son. That journal is crucial to understanding the boy’s evolving values – both those he accepted wholeheartedly and those he subverted and adapted as he matured. The view of childrearing prevalent in late-nineteenth-century middleclass Methodist homes was rooted in religious values. The cornerstone of Methodism is justification by faith, that is, “conversion as a conscious and responsible act,” leading to “a total subjugation of the self to the will and love of God.” As for childrearing, the conception of Christian perfection at the heart of Methodism made it but a short step for Methodist mothers to become perfectionists in all spheres. Accordingly, children in Methodist homes in this era were viewed as “buds of piety,” who from the age of four or five could be actively encouraged and educated as developing “candidates for the kingdom.” They were to be led to resist sin and accept Christ. Religious decision was encouraged by parents,

22

BOTH HANDS

teachers, and the church as early as possible. What has been called “an optimistic view of the moral status of childhood” justified “direct control over the young”31 in order to swell the ranks of the young in the Methodist Church – from 1850 the largest Protestant denomination in Ontario32 – and reform society. The great Canadian divine and educational reformer Egerton Ryerson (later to be a kind of patron saint for Lorne Pierce the publisher) taught that education infused with a dedication to “order and discipline as the foundation of good character” was the key to training the developing child.33 The Methodism Lorne Pierce experienced at home, church, and Sunday School was typical of the time – dynamic, strongly middle class, outward-looking, and reform-oriented in both individual and social terms. Lorne and his sister were urged to avoid evil companions and unedifying books. Both home and Sunday School (and his parents were central to both) trumpeted the love of God and the need to avoid sinful ways, epitomized by alcohol, that “most perfidious and dangerous device of the devil.”34 On the Pierce bookshelves, as well as the Bible, books of sermons and devotional tomes, and titles by Ruskin, Edmund Burke, Robert Browning, and Sir Walter Scott, there were tracts attacking Darwin, T.H. Huxley, and the “higher criticism.” But to Lorne’s parents, the most outward and visible enemy was not natural selection or the higher criticism or even dancing, card playing, or tobacco – Enemy No. 1 was alcohol. Their antipathy was understandable. After all, the problems of liquor in turn-of-the-century Canada were all too evident. One had only to walk by the licensed local hotel most afternoons or evenings, never mind lie awake on raucous late nights during the Delta Fair, to see the inebriation and attendant problems wrought by what was then known as “the liquor traffic.” If church and tavern were the two great voluntary institutions of Victorian small-town Canada,35 Hattie Pierce knew which institution she favoured and which she deplored. Temperance was a religious and social cause célèbre of the day, and one of the earliest causes of Methodists, of women, and of maternal feminists, as the career of Nellie McClung, a small-town near-contemporary of Hattie Pierce, suggests.36 The temperance movement in Canada had in fact begun in Delta in 1828, with a sermon preached by Dr Peter Schofield.37 Lorne was early taught by his mother to abhor alcohol, an aversion strengthened in all the Pierces by embarrassing visits from a relative often “under the influence.”38 Lorne’s childish printing is found on a pledge of abstinence signed in May 1897 when he was not yet seven, a

Lorne, Mother, and Methodism 23

pledge he was conscious of throughout his life.39 It was not unusual for a boy’s mother to “sign him up” at a tender age. For example, Samuel Dwight Chown, in later life a leading Methodist clergyman and a Lorne Pierce in-law, took the pledge at the age of four. Moreover, Harriet Pierce was the local Women’s Christian Temperance Union (wctu ) president. Young Lorne never had a prayer of encountering King Barleycorn in his own home – unless he caught a whiff of his bibulous relative’s breath. Lorne’s signed pledge (accompanied by a badge which read “Tremble King Alcohol we will grow up”) is still tucked in the small, blue-bound leather journal his mother kept for him. In that crucial document, Lorne emerges as a lively, precocious, largely tractable, and intelligent child. Hattie Pierce comes across as a loving but exacting Methodist mother zealous to inculcate in her offspring the saving concepts of purity, righteousness, and “sacrificial service.”40 Lorne’s first overnight outing (at eleven months) was a family camping expedition to Robertson’s Landing on Lower Beverley Lake with the Methodist minister and his family. Several months later, his mother proudly depicted Lorne at eighteen months old: “Lorne began to preach. Auntie McAdam would get him on a stool and there he would lay it down with hands and voice altho’ the words were not very distinct, but then a baby of one and a half years could not be expected to speak very plainly.”41 Even the birth of Lorne’s sister did not distract Mrs Pierce from her sense of mission toward her son. While she extended her sense of maternal duty to her daughter, her son’s development remained primary in her eyes. For her part, Sara was to grow into a strong woman, with four children of her own.42 In Delta, she was raised in the tradition of another maxim of the day: “a daughter is a daughter all of her life.” She certainly was a devoted daughter, but she was also a loving sister. Sara was to follow Lorne to Queen’s, to the west to teach, and to Victoria College to study. The two were to share accommodation at times in all these places. Later, Lorne, in military uniform, officiated at Sara’s wedding to the Reverend Eldred Chester during the Great War. Brother and sister both summered on Lower Beverly Lake – the two families sharing a cottage on Whiskey Island for twenty years. In short, Lorne and Sara enjoyed bonds unbroken until Lorne Pierce’s death in 1961. By the time Lorne was six years old and Sara four, his mother clearly felt that her moral nurture was bearing fruit in both children. An evangelist arrived in the village in December 1896 for five weeks of revival services. It was, after all, the heyday of Ira Sankey and Dwight Moody,

24

BOTH HANDS

Lorne Pierce and his sister, Sara, c. 1896. Courtesy of Beth Pierce Robinson

professional evangelists who sought to evoke and update, for the emerging middle classes of late-nineteenth-century Ontario, a religious spirit of repentance and renewal that harked back to the early days of Methodism in Upper Canada. Of the Delta revival, Hattie Pierce jubilantly recorded in the journal: “Lorne and Sara gave their hearts to Jesus again as Mamma had often taught them before. They were wonderfully blest on Jan 5th 1897. Lorne gave his first public testimony. ‘I love Jesus.’”43 Did Harriet Pierce regard this incident as a highlight of a crucial conversion experience in her son? Was it part of an emphasis on such conversions that was at the emotional heart of the evangelical rural Methodism

Lorne, Mother, and Methodism 25

in which she herself was raised in the eastern Ontario of the 1860s and 1870s? The journal indicates that she did see Lorne as in the grip of childhood conversion, although by 1897 Methodism was moving from an evangelistic emphasis on individual salvation and dramatic childhood conversion to an advocacy of social progressivism of the sort that Mrs Pierce was foreshadowing in her temperance and charitable community work. In the 1890s, the need for, and even the value of, eliciting from young children such dramatic “testimony for Jesus” was increasingly less emphasized within the Methodist faith. The new trend was to produce young Methodists who could, in the words of John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, “serve the present age” in their life and work.44 And Harriet Pierce was even keener on the notion of service than on the imperative to testify for Jesus. Her Methodism in fact typified the blend of evangelical emotionalism giving way to social activism that was manifest in the domestic and religious roles of Methodist women of the day. Her tutelage of her son exemplifies a way of believing on the part of late-nineteenth-century Methodist women that probably began with her own more dramatic “conversion” in girlhood. One scholar notes: [Conversion for women was] the beginning of a commitment to nurturing the Christian life that involved intensive selfexamination of daily activities and “useful” social involvement. … Women’s work in Sunday schools, missionary societies, reform movements, and charitable organizations gave them opportunities to influence life outside the domestic sphere [while d]aily life was invested with religious significance as men and women aspired to conform their personal behaviour, homes and communities to evangelical ideals.45 The passage crystallizes Mrs Pierce’s values. But, by the time Lorne was born, dramatic conversion experiences in children were less the norm and less sought after by devout parents.46 Looking back on his childhood, Lorne himself expressed distaste for dramatic childhood conversions. The emotionalism of revivalism was a traumatic memory: “I remember,” he wrote in 1920, “Father holding me up to the 1/2 painted windows of the old Russell Store [in Delta] where a Revival was in progress and seeing a huge poster in red with white letters reading ‘Hell or Heaven – which?’”47 Lorne was brought even

26

BOTH HANDS