Becoming the dance: Flamenco Spirit 084035844X

Teodoro Morca lives as dance. A composition in movement, a cycle of change. Teodoro Morca, dance, crisp and rhythmic, is

161 55 17MB

English Pages 118 [134] Year 1990

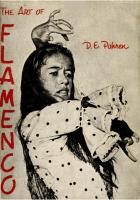

Cover

Half title

Imprint

Dedication

Special Thanks and Acknowledgements

Table of Contents

Foreword

Preface

Flamenco

The Roots Of Teodoro Morca

The Roots Of Flamenco

Flamenco Spirit, a Golden Thread

Zen and the Art of Flamenco

In Respect Of Tradition

Flamenco — Timeless Ongoing — It Is

Technique, Craft and Art

Search for Individuality

Are You a ‘Flamingo’ Dancer?

Flamenco Anatomy

Exercise, an Aesthetic Point Of View

For the Dancer, Flamenco and Your Body

Flamenco for Non-flamenco Dancer

Dancing with Control

Dancing and Age

Dance and Diet

Back to the Basics — the Inner and Outer Dance of Flamenco

Becoming the Dance — ‘Duende?’

Some Thoughts on the Dance

Learning Flamenco Outside Of Spain

The Flamenco Workshop

Beyond Compás

Alegrías — the Joyous Concerto of Flamenco Dance

Bulerías, Viva Tu!

Sevillanas — Arte, Aire y Gracia

Soleares — Arte Grande

La Farruca De Verdad — Inspiration of Earth and Sky

Listening to Flamenco

Interpreting the Cante in Flamenco Dance

Contra-Tiempo — Rhythm's Life Force

The Power Of Subtlety

Footwork, From Noise to Art — “When you Speak, Say Something”

The Art Of Jaleo

Castanets

Costumes and the Dance

Wood that Laughs, Strings that Cry — The Flamenco Guitar

Choreography

From an Audience Point Of View

Flamenco in Concert

Touring Flamenco

Pilar López

Touring Spain and Fine Experiences

Dancing in the Caves Of Nerja

Flamenco Can Happen When You Least Expect It

Café Chinitas — An Experience in Spain

Shoemakers Are Artists Too

Becoming Professional, Being Professional

Inspiration — Carmen Amaya

The Many Other Faces of Spanish Dance — The Folk Tradition

Exploring Another Dance Style — Classical Spanish Dance

Creation of a Style — Interpretive

Flamenco Glossary

About the Author

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Teodoro Morca

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

Becoming the Dance’ FLAMENCO SPIRIT

po ela

Becoming the Dance’ FLAMENCO SPIRIT by Teodoro Morca

€

KENDALL/HUNT 2460

Kerper

Boulevard

PUBLISHING P.O.

Box

539

Dubuque,

COMPANY lowa

52004-0539

Cover photo of Teodoro and Isabel Morca Back cover photo of Teodoro Morca

Copyright O 1990 by Teodoro Library of Congress

Catalog

Morca Card

Number:

90-60628

ISBN 0-8403-5844-X All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Printed in the United States of America 109 8 765 43 2 1

Dedication This book is dedicated to all peoples who

seek a way — not the way, for there are many

ways, buta way —a path to becomingthe dance,

to feel that dance of life, that communication of spirit, of life, of self.

That path that I have found so real isin the art of flamenco. The spirit of flamenco is the dance of life. Flamenco is the essence of creative meaning of life living itself in music, in song, in dance. Flamenco is a creative path to your inner feelings and emotions that surface with human truth. Why, why flamenco? Flamenco was born of the womb of the human soul crying out for eternal freedom of spirit. The art of flamenco is living and expressing this eternal freedom of spirit. The way of flamenco is the art of living each day to its fullest, physically, spiritually, emotionally and mentally as an individual and fulfilling your individuality as a unique creative expression of life.

The body expressing flamenco in movement

and sound

is communication

with the heart,

with the universe, in spirit, soul and in feelings that are feelings of truth and individuality. Yes, flamenco is freedom, flamencoisfreeing the spirit to soar, like on the wings of eagles. Flamenco is a word of unknown origin, yet flamenco is understood throughout the world as the essence of all human feelings and emotions in music, in rhythm, in song, in dance, in art. Flamenco is the un-selfconscious joy, sor-

row, passion, pain, growth, love, fear, fear of

death, fear of not living the who that you are. When you awaken the flamenco within yourself, you awaken your true self. When you can become the dance, climbing into your duende, your aire, your gracia, you will dance the dance of life. You will become the dance and in that moment, you will know the meaning of your life in the purest of truths.

Special Thanks Isabel, my wife, my best and dearest friend and a fabulous creative artist in her own right, has been the inspiration and the guiding ‘push’ behind this book. Whenever my Libra nature procrastinates, she will say, “I will help you, you can do it, go for it.”

I would like to thank her for all of her help, for her multi-faceted talents and for

choreographing the perfect marriage.

Teodoro Morca

Acknowledgements I would also like to acknowledge Juana de Alva and Paco Sevilla, the founders of ‘Jaleo’ the international flamenco magazine.

Typography, Edit and Design by Kathleen Weisel Typesetting, Bellingham, WA

Table of Contents

¡NTRA

lii

Special Thanks and Acknowledgements .....oooononiccnonoconononnoncannnnnonononnonaconnonnonnonncnncnonons 1v FOC WOM

......ssceessscssesssececsssceescssscesessesessssceesecsseceescssneesecsaaeesessseeecesseeesesseeeceseseseceseansessenes vii

¡SERA ¡FEST

viii 1X

The Roots Of Teodoro MOI ca ou... cescssccssscsessscscesscstssseeseecsescsceeseeeecescescesseceaeesseensenseees 1 The Roots Of FLAMENCO ....occnicnocnonnnononnnnnnonaccnnonnonanonccnononocnnnno nooo noncnono conc n conc rro on ncno rra nan nos 3 Flamenco Spirit, a Golden Thread .....conoonicnicnoononninnnccnnonorncnncononnonocrncnncnnoon nono c nono nronon cons 6 Zen and the Art of Flamenco ....cooccconcconnnonnconaconnconnnonncnonannn nooo noonnoonncornroon con nconn con ncannnns ..10 In Respect Of Tradition ......ooncoocnncnncononcononaconcnncnaccnananoncononnnnonacnnnonorononnnn conc cnncnnnonn on rcnn conos 11 Flamenco — Timeless Ongoing — It IS ......oonionocnnccinocionnnacocnconcncccononocororrnnornoonconocononnos 12 Technique, Craft and Art ...oonconccnconicconocncnnocnconocnonnonacnoncanonnoononn non nono corona cnn ron non n conca narcos 15 Search for Individuality ..........oonocnocnonocnonocnnnonnonnonannnnnonanonoconocnnonnornncnnnonannn cocoa ronnnooranooos 19 Are You a ‘Flamingo’ Dancer? .........ccssssesscssesscscsscsscsseeeecescencsaseeseeseeeceasenseaseceaseesses 22 Flamenco AnatOMy .........cccssssscssssscscsessecsesssencssssecscescceseasescsseseessceeseaeeeeeaseessesseseseaeees 23 Exercise, an Aesthetic Point Of View .......oococcnccccnononnnccccncnanncnccnnonoccnnnnnnncnnnnnn sssssescees 26

For the Dancer, Flamenco and Your Body ..ooonnccnnccnocuoccnonancnnnnnnnonnnconaconananccnanannnnonss 28 Flamenco for Non-flamenco Dancer ........cssssscssssssecscscsssecscssescacsccsssssesscsesces sesssesseees 30 Dancing with Control oo...

cscssssscsscessssssscsscescsessscsesssseese sosssssssesssssseseessessesseseeseesees 31

Dancing and Age .........ccssssssssssscsscscsesscsscessssecsceesscessesessessseeesseesesessssessesecsseaseseecsesasesees 3 Dance and Diet...

cc csssssscssessscssesecessssssescesssecssescccsssssesesseseessesseeecaesseeecsesaeseeeeeees 37

Back to the Basics — the Inner and Outer Dance of Flamenco. ..........:ccsseseeeeeees 39 Becoming the Dance — ‘Duende?’ 00.0... ee sscsccssssscssessceseesessesscsssesessesecsseescsseeecseeneens 41 Some Thoughts on the Dance «0.0.0... ecsesscrcesceccssesccssescsecsssseeseseeseesscecsessesesesseeeseeseeess 43 Learning Flamenco Outside Of Spain ...oocconcnicnnonocnonncnnnonnnecnnnnncnononnoncnoncnrnnononnoncnnanonoons 45 The Flamenco Workshop .....ooococcocoonocoonnnononanicnononnncnncnnnncnnonononno nooo nono ro conoce noc arnancananncnoss 46 Beyond COMPÁS ..ooonoccccnonncncononnonunonanncnnnonnonannonnoonnoncon nono nonnconn o concen nrnn cacon none on cra cnneracones 49 Alegrías — the Joyous Concerto of Flamenco DaNCe ..oooonconccocicnnioncnnncnonacncnncanononncnnos 51

Dl

Bulerías, Viva Tul ..........occccnnnnninononononononnnannnnononcnonencnnonnoninaciccononononononnononconodo nono nono nneneninoss 54

Sevillanas — Arte, Aire y Gracia .....oooooonccnonnnnoncnononnnconncnnoconannnonnccnnnnno nooo nooo nonn nono conncnnos 57

Soleares — Arte Grande IA

61

La Farruca De Verdad — Inspiration of Earth and Sky .........cscssssssssssessesseseessseseees 63 Listening to Flamenco ....oooononcnnnoninnncnncnnonacanocanonncnanonnnonaconanonanan crono cononona cono ncroo cra rones 65

Interpreting the Cante in Flamenco Dance ......oonionicnicnnonocnnionnnnnnnnnnnnonanononononoooooononocoos 66 Contra-Tiempo — Rhythm's Life Force.........cooocnnonncnocnnocnononnconcononacnnnococononooonoroornoononns 69 The Power Of Subtlety.............oonconmonmonmonm»*mommmmomnommsrros 71 Footwork, From Noise to Art — “When you Speak, Say Something” ................... 73 The Art Of Jaleo ........... cc cecccssseccecssssssccecessessncececeessnaececsessneeseceesenenseceessneeseceesseessceseseessecs 74 CATIA

77

Costumes and the Dance ........oonconcnnocnoncononinonanionononnnanonnoncconananonnonnonconncnconncnnococonccnnnnnonos 79 Wood that Laughs, Strings that Cry — The Flamenco Guitar ......onicnocniconnonnonionocos 81 CHOreOgTapPhy .........cceesscssscsseescesscssesssesscsssssssescsssoscesssssoessesssescssesseescessesssessesesoesseseeees 84 From an Audience Point Of View .......oonooncnoccnnoonnnnnconocacononnonaonnanaconaraconoonnconornonnoonaonconos 86 Flamenco in CONCELSE ....... cc eecessceeseseessesscsssesssonssseeesscsssessscrsessseessseessesssseeseessessoeeesessenens 88

Touring Flamenco ..........ccccecsssessceteesessesscsesssssecssesssssecsseescnsecsesesseseeseesesessseeeaseeseeseness 90 Pilar LÓpezZ ..ooooncoccnicnncnncnconocanonncnnccnnonncnnccanonnonnncnonanonarnnocnnnnrnnrno none rnnorn non ron ron conc rn nooacnness 92 Touring Spain and Fine Experiences .....conconicnoccoononncncccnnnnnonnonnnonacnnonnnonoononnannorneconnnoss 92 Dancing in the Caves Of Nerja ......oooncncninonnonocnonionincnncnnonacononinoncnnncnnonaonncnnonncononanoncrnoss 96 Flamenco Can Happen When You Least Expect It ......oocociononinonommsmmmss9os*”m”eo. 98 Café Chinitas — An Experience in Spain ..ocoonconcnocionnononnnononannnonconananrncanonnonnonconnonnonaso 100 Shoemakers Are Artists TOO .......oooonccnoonicoonnnincnnncanocnonnocanonnonocnononncncnnnnoanoncornnnanonnonaannos 102 Becoming Professional, Being Professional ..............cssscssseseseseseeeneeteeseneeressenenees 103 Inspiration — Carmen AMAya..cooooononnncnconononinnnonncnnccnnorinonnconnoncncn nono non non caro noro noo non ncon eos 106

The Many Other Faces of Spanish Dance — The Folk Tradition.....................o...». 107 Exploring Another Dance Style — Classical Spanish Dance. ...........:seseseseereeeee 110 Creation of a Style — Interpretive ....ooooconcnionnoonnnonononoronccnnnonanonananon nano nonnonnononrancononancnes 113 Flamenco GlOSSALy .........cssccsscssecsscssscssscesscesseeseeeeeeecseensecsaecesecseesseesseenaeerseseseesseen ness 117

vil

Foreword Dance, art, music and

spiritual conscious-

ness have always dominated the life and love of Teo Morca. Teo lives each day full of positive and creative energy, with a spiritual awareness that each day must have meaning, that each day must be lived as though it were our last. Life, talent and art are to give and share. I shall always remember Teo performing his beautiful rendition of Bach’s “Toccata in Fugue in D Minor’, his face aglow with the duende of all of his spiritual ancestors as he explored the utmost of his soul with his great art. In writing this book he has shared with the world of all those who love flamenco, dance, art

and life, the ideas that he has developed or been inspired by — hoping that by this book others will be inspired to improve their art of creative effort. Teo is creative in all facets of his life. When he is not busy dancing, then he is busy thinking of new ideas for choreographies, drawing, writing articles on dance or beautiful poetry, creating a piece of sculpture, helping his son Teo Jr. witha father/son project, cooking a marvelous dinner or just being a wonderful person. As a dancer, Teo Morca is one of those few

who may be called genius. He is possessed with a clean, precise technique and sense of rhythm and counter-rhythm, exciting to listen to and to

watch even more so, because of his ability to

“become the dance”. The audience feels what he isexpressing emotionally and becomes entranced by the strength and energy coming from his artistry so subtly and synergistically. As a teacher of dance, Teo has developed a way of teaching which has method of progression of knowledge behind it. Instead of the ‘stand behind the teacher and copy him’ method used by most flamenco teachers, Teo teaches where the movement comes from, braceo, turns, foot-

work patterns, and most important, the interpretation of the compás. He explains the rhythmic structure for all of the flamenco styles and dances, how to dance with guitar and song ac-

companiment, how toimprovise within the structure of each dance rhythm. In his articles, dance workshops and video tapes he gives to the student all that he has developed as well as technique and knowledge. As a creative artist, Teo possesses a shrewd sense of theatre and what creates interest to the audience. Based on the traditional forms of the dances he creates fanciful and dramatic works. In his “Botas Magtcas’ a shoemaker puts on a pair of boots which cause music to be heard whenever he picks them up. Then they begin to dance a zapateado and he has to follow them wherever they take him even though at one point they go off in opposite directions. In his ‘Semana Santa’ based on the religious processions during Holy Week in Sevilla, he becomesa poor prisoner asking forgiveness from the Virgin Mary as the procession passes his prison cell window. In ‘Los Amantes Sin Futuro’ a smuggler meets his beloved Spanish lady at midnight and they dance their last dance together. As she leaves him her lace mantilla, he recites “My life will be one of aloneness, but your life will be one filled with sorrow”. Teo’s unique ability to design dances which are filled with tragedy, sorrow or humor are a delight to the audiences who can identify with the human conflict within. Apart from his flamenco

choreographies,

Teo

Morca

has

also

explored the vast realm of the classic, theatreballetic Spanish dance school, most admirably in Pachelbel’s ‘Canon in D’, Boccherini’s ‘Gran

Fandango’, Bach's “Toccata and Fugue in D Mi-

nor’, Vivaldi’s ‘Classical Guitar Concerto’, Saint-

Saéns ‘Introduction to the Rondo Cappricioso’, Granado’s ‘Goyescas Suite’ and countless other beautiful works. Teoisa wonderful husband, father and friend.

He eats, drinks and breathes flamenco. He is a

great artist, choreographer and teacher and he gives to the world of Spanish dance a great legacy through his knowledge, sensitivity and unending creativity. Isabel Morca

DMI

Preface This book began many years ago. Its origin was not so much in writing, although much of this book is made up of articles and ideas that I have written for ‘Jaleo’ magazine. Some as essays ona given question that I was asked, others to clarify my opinions and ideas. The opinions are of my personal experience of forty years in Spanish and flamenco dance. It actually started when I began to dance in my teens and immediately began to ask questions — “Why? What? Where? When? How?”

— about dance, about Spain, about flamenco,

and aboutall of the myriad things that interested me about the whole art form. Inside, I was trying to bring my mind into synch with my body. I was fortunate to become associated with teachers and friends who encouraged my studies; to read whatever I could

find, to learn as much as I could about the art,

about the peoples and cultures that were the cradle of the dance. There was never enough. I devoured the limited book supply that I could find. Books on the subjects of Spanish and flamenco dance, folkloric dances and other dance forms were very few. From the beginning, I seemed to feel intuitively that I wanted to ‘become’ the dance. I wanted my technique, my craft, to permit me to know my feelings through dance. I kept hearing the word ‘art’ and began to feel that only by becoming completely in tune — through understanding

the forms, dance, music, craft, tech-

nique, culture, art, my attitude, respect, love of what! was doing— would I someday ‘feel’ what art was.

When I went to Spain in the early 1960s, I felt as if I were coming home. I had absorbed so much through my contact with Spanish artists, singers, dancers, guitarists, and other people who helped me in my search, that I felt at one with the ambiente. 1 wanted to just swim in the ambiente of this country that gave birth to the art of flamenco, the dance that was now so mucha

part of my life. My soul was plugged into flamenco. Idid not try to become Spanish, for I felt that flamenco transcended Spain. The feelings and emotions

that I felt were universal love. I felt at one with flamenco — it was me. Believe it or not, I felt this way when I was a boy of 13 working as an auto mechanic. I worked for two men who were great artists of auto repair. They gave me the love and inspiration to take a broken car and, with pride in my workmanship and craft, repair it like new. Doing it well gave me a taste of satisfaction in craft and art.

When I saw my first dance concert, (I was supposed to have gone to a symphony concert, so destiny sort of interrupted), I discovered that

I was a dancer, I knew that it was me. I was

inspired. I knew that I could become a great dancer by the same sort of apprenticeship that had led me to become a fine auto mechanic. An auto mechanic and a Spanish dancer may seem miles apart, but when you search the art, and

look at the how and why, you realize that they are just different facets of our co-creative self. This book can never be finished because as

long as we think and grow, there will be other

ideas and thoughts. We will have new realiza-

tions about dance, about what it is, and about all

that we relate to dance. It has been designed and presented with the idea of being read and looked at many times, opened at any page. There are many repeats throughout the work, many times the same subject is taken up and viewed from a different angle or seen in relation to other matters. “Becoming the Dance - Flamenco Spirit’ is really a search, an awareness of becoming at one with the self, and feeling who you are. As an old Zen master said, “Begin each day with an empty cup so it may fill with living.” If this book has any suggestive value it will be to stimulate independent thought and study; and hopefully it will bring new understanding of the beautiful and exciting world of flamenco. Flamenco to me is living each moment fully. It is the dance of life. This book is for all those who want to continue their search for the dance that they want to become. Teodoro Morca

Bellingham, Washington USA

Segutriyas, Ay ... Seguiriyas

Body exploding, arms reaching, squeezing rhythms into a broken pulse ... Pain that feels no pain, dry tears that claw the throat ... Tension, striking the earth like self burial ... A death that will not live its death ...

Flamenco FLAMENCO

... the art, the music, the song,

the dance,

the way

of life of

Andalucia, of southern Spain, a melting pot of many exciting peoples that over the centuries have blended their cultural heritage into one of the most unique art forms in the world. Flamenco is ancient, yet new, evolving with the times like other great art forms. Like the roots of ‘Jazz’, flamenco was born of peoples expressing their inner feelings and emotions, their joys and sorrows and also their art and beauty as a way of life. Flamenco is an improvised art form within a very complex set of rhythmical structures. There is no written music in flamenco. There is a total inter-play between guitarist, singer and dancer — in music, rhythmical expression, interpretation and inspiration. It is a blending of feelings, emotions, inspirations and art, to experience that feeling of becoming the dance, the song, the music, the all-important duende or inner spirit and soul. The flamenco dancer’s whole body is a musical instrument, visually and audibly expressing the total art of flamenco, a serious art form born of the highest cultures of east and west, a form, like all true art ... of the world.

The Roots of leodoro Morca I was raised in Los Angeles in an ethnically mixed neighborhood — Caucasian, Hispanic, Black, Jewish, Slavic. It was marvelous

to go

down to Adams Boulevard and be able to go froma Jewish delicatessen to some Greek church

or a Black Baptist church. I started to hear Spanish from a Mexican family that lived across the street.

I remember being interested in music and dance. My Hungarian grandmother had an old wind-up gramophone and she’d play Hungarian music. My Aunt Bea used to tell me “You were always wiggling and jiggling.” I always liked to move. A turning point in my life was when I became an auto mechanic at a place run by a fellow named Racey, kind of a Will Rogers type. He was into nature and a real humanitarian. He took me under his wing, he and his partner, an English fellow named Bill Bradshaw, they made me feel part of their family. I started working for him when I was about 10 years old, I loved it. Right away, he started to teach me how to fix cars by showing me how they worked, and how it was an art. He approached auto mechanics like a craftsman, like a sculptor, the old-fash-

ioned way with almost no electric tools. He took greatpridein his work. Everything I did, whether it was sweeping the floor or minimal work on car, everything was, “Do it right. Take it apart right. Make sure everything is clean and right and perfect.” That instilled in me a certain pride in craftsmanship. By the time I was 14 I had my own customers, doing brakes on doctors’ old Lincolns and all kinds of other things. Racey had a nine-acre ranch about 45 miles north of Los Angeles that was his retreat in nature. He built a cabin on it, and started taking me up there with his wife and family. Up until then, at 12 or 13, I was physically sickly, I could hardly eat anything unless it was cooked, and I would catch every cold going around. Then I started going to his ranch, and working, not just playing. I learned how to drive a tractor, we pulled a lot of sage. We picked berries, and we planted the whole nine acres with oranges. In one summer I gained 30 pounds. I’ll never forget when my mother came back froma visit to an uncle in Philadelphia who had

a radio program there. I was supposed to meet her at the train, and she walked right by me, didn’t recognize me. I was tan and my voice had dropped, I was huskier and I had gotten into gymnastics. She couldn’t believe it was me. The ranch was another important point in my life in the sense of quality of life, Racey was into nature and spiritual things. I went to the ranch for 4-1/2 years, until my boss died of a heart attack right there on the ranch, I was there with him. He was the father image that I had lacked, because my dad had died when I was about four. Racey gave me reason to be on a straight and narrow path. Atone point I had been hanging around with some real juvenile-delinquent typesin the neighborhood. Racey basically told me to either shape up or ship out, and I respected him so much that he became a major influence in my life. By the time I got into junior high school, I felt pretty much at one with myself. I wanted to be a good gymnast, 1 was going to be a top auto mechanic; I knew where I was going. If I did go to college I was going to be an industrial arts teacher. I really like to work with my hands. I got to be a very good mechanic, I had a lot of dexterity. They used to give me all the carburetors, distributors,

weird

transmissions,

and

other little things. It was an interesting shop, we used to work on old Packards, Dusenbergs and Pierce Arrows. I’m fascinated to this day with all the old cars that I look back at now. I met some people in junior high and high school who were into music, and I took a music appreciation course when I was about 15. Little did I know, but this probably changed my whole life. I discovered classical music. In the 40s and 50s young people were listening to ‘modern’ music. But I discovered Beethoven and Bachand Scarlatti. We'd listen to symphonies and concertos, and I found it fascinating. I went with a friend to a dance concert by mistake, it was supposed to be a symphony, instead it was a Spanish dance concert, at the Philharmonic Auditoriumin Los Angeles. Anna Maria and her Ballet Español — 1 remember it as if it were yesterday. I was really moved, found it beautiful and exciting and thought it would be fun to do that, this changed my life.

to

At about 16 I was

working after school at the auto shop. A girl that knew was taking

some dance classes and she invited me to come and watch a class. It was at RuthSt. Denis’

studio in Hol-

lywood, who, later with Ted Shawn had

developed

the Den-

ishawn Dancers. Later on, I would work at Jacob’s Pillow six times, which was Ted Shawn’s Dance Festival, the oldest in the US. Almostassoonasl

walked

in,

I

was

Tootikian,

who

greeted by an Armenian lady named Karoun

was to become a great

friend. She had an ethnic ballet at that time called the Armenian Dance Ensemble. She

Teodoro Morca dancing to the guitar of Geronimo Villarino at Eduardo Cansino Studio at age 17.

had danced with Ruth St. Denis. At any rate, I watched this class, and Karoun looked at me and said, “Hmmm. We're having a recital and we need a boy, would you mind? You don't have to do much.” It was like today, there were so few boys. I said, “Okay, what do I do?” They were doing a Christmas show for the Armenian Old Folks Home, and I was one of the Three Wise Men, I wore a little

Grecian outfit and carried a plate. That was my introduction to the professional world. I started to go to these studios a little bit and heard about the Cansino family. Eduardo and José Cansino were part of the Cansino family, which was very famous in the 20s. This was a family of Spanish dancers, not so much flamenco, but all-around Spanish dance. Their parents had been a very famous vaudeville group from Alicante, Spain. I had a little poster — in big letters it introduced the Familia Cansino as the opening act, and in very small letters, asa supporting act, was Bob Hope. In his biography, Fred Astaire, gives

a lot of credit to Eduardo Cansino. Today Edu-

ardo is probably best known as the father of Rita Hayworth. I went over and there was a big group of people. I walked in, and they said, “Okay line up” and I just followed along. Then I took lessons from José and started to learn some dances.

I only went Saturdays because I was still going to school and working after school. But I found myself waiting for every Saturday afternoon class. I just loved it. The people I met there had a certain joie de vivre, a certain gracia and liveliness. I’d work all week and my mind would be on the footwork, or castanets, I had these little teeny plastic castanets... Westarted doing recitals. I was still going to

Karoun’s; I was going to Ruth St. Denis’; then I

would go to this flamenco/Spanish class with José. After just one or two little recitals given by

him, in which he used everyone, at the Royal Jubilee Theatre, I said, “This is it!” In my mind I

knew, I wanted to do this all the time.

The Roots of Flamenco Flamenco has two very real meanings. To

most of the world, it is an art form — one of the

most highly developed forms of folk art in existence. To true aficionados, flamenco is a com-

plete way of life. Artistically speaking, flamencoistheevolved song, dance and music of the Spanish Gypsy and the melting pot of cultures that make up Andalucia in southern Spain. It originated from a

balanced mix of Eastern and Western cultures,

and is uniquely cross-cultural in both a visual and an auditory sense. Although the name ‘Gypsy’ is derived from the word egipto, (Egyptian), after that North African land through which they probably wandered, the original Gypsiescame frommuch further east. Legend, passed through generations on the tongues of Gypsy storytellers, suggests that these people began their travels in India, wherecomplex traditions of classical dance and music can be traced back many thousands of years. Around the late 15th century, they began to appear in southern Spain. By that time, Spain already had a rich tradition of regional folk dance and music. This was particularly true of the region known to the Arabs as al-andalus or Andalucia, ‘Land of the Vandals’, where Moor-

ish and Arabic, Semitic and Greek peoples lived side by side. The Gypsies were wandering tribes who, for reasons long ago lost, left their Eastern homeland for another freedom. That is the basis for the Gypsy way of life. Gypsies demand a freedom within nature, a right to be left alone with life, to be able to go wherever their inner voice

tells them, to go ever seeking that hill just beyond. The very nature of this wandering has made the Gypsies tremendously aware of all that they contact, their surroundings and

the

people. Inevery country they pass through, they observe and absorb what they desire, like a creative sponge. Then they squeeze out what they willand thoughagitanado, ‘Gypsy-fication’, it becomes all their own. This is what probably happened in Spain. Over a period

of time, the Gypsies

absorbed

certain elements of the pre-existing cultures, molded them to the Gypsy way of life, and

created a unique Gitano (Spanish Gypsy) culture of their own. Andalucia, the southern region of Spain, became the home of flamenco.

Of all the incongruous elements in flamenco, perhaps the kinship with Indian dance is most interesting. In India, dance is total involvement;

every movement of the body, from the hand motions to the complex footwork, plays an important part in the dance expression. The

same is true with flamenco. What's more, the

roots of both dance traditions are in religious expression.

Beinga very misunderstood people, because

of their individualistic ways, Gypsies have for centuries been persecuted and looked down upon. They have been feared for their cloak of mystery, yet at the same time have been held in awe by many people. A strange, distant respect for them prevails to this day. What holds Gypsies apart from non-Gypsies is their belief in their particular kind of God-given inner spirit, which they call duende. This is one reason for their arrogant pride, a childlike faith that fulfills their desires, whether traveling on the open road or dwelling in caves in Granada’s Sacromonte.

The Mystique of Duende To the Gitanos, who live in a unity with nature and Mother Earth, flamenco is a sacred

ritual. All aspects of life are relived through the song, the music, the dance, and all emotions

surface. And no element of song or dance is more important than the release of one’s inner duende. Duende is ‘becoming’, being ‘possessed’. Duende isa feeling, and as such is difficult to define. It means spirit or soul, but itis more than that. It is a fiery inner demon, one that when released can possess not only a performer but also all the participants and onlookers in a flamenco gathering, or juerga. When a Gitano is possessed by this duende, he believes that he is in rhythm with all of life, in all its aspects. He is in rhythm with the sun that gives us life, and with the earth that goes around the sun. He is in rhythm with the waves of the sea as they crash powerfully upon a rocky beach

over and over again, calling, “Come to me, for I

am your true mother.” He is in rhythm with the

Flamenco Spirit,

a Golden Thread

Spirit is a golden thread whichrunsinand throughall of life, all of creativity. It is a word used often to try to describe something that is higher and more divine than our pure, physical life force, our everyday function and existence. Like the word love,

spirit has an almost endless variety of expressive uses. But its realm of vagaries and explanations sometimes make it an uncomfortable word to

use.

Spirit has been defined as ... the principle in conscious life, identified by breath ... | the vital principle in man, anii; mating the body or mediatbl ing between body and soul A b ... an angel or demon ... an Y inspiring or animating principle such as pervades and tempers thought, feelings and actions ... the divine influence, as an agency working in the heart of man... the dominant tendency and character of everything ... the essence or action, the principle of life force that rises above the physical form. Applied to a creative expression of humanity, spirit can be described as the basic Teodoro and Isabel Morca essence of that creativity in its relation to the individual's creative expression. That could refer to the spiriongoing realm, above the basic movements of tual relationship of any man’s or woman's creadance and of the sound of music and song. tive or expressive or artistic outlets. Indeed, the spirit runs in, through and all The total realm of flamenco isa multi-faceted about flamenco. That is what I explore here, for manifestation of expression, whether we want as nebulous as the search for awareness of the to talk of the art of flamenco or just its basic spirit may be, it appears to be a very important origins in expression of feelings, emotions, and factor — this golden thread that flows with the the personal outpourings of the person or percreative energy — the life force of flamenco sons involved. Since my personal world has itself. been involved with flamenco for so many years, The angels and demons of flamenco guide us if we are indeed in tune with the flamenco spirit. I find it an exciting subject to explore in its zo

| en

&

If flamenco is part of our true soul, then we will connect with the spirit, as it will be our true and

sincere creative outlet. Just as the life force of an

orange tree gives birth to oranges— itisalways true to the orange and never tries to be an apple — so flamenco. The spirit is almost impersonal, for if you plug into it with truth and sincerity, then to your capacity will the spirit flow. Flamenco will do nothing for you; itis what you put into your creativity, your co-creativity with life, that will give you some form of joy and satisfaction with your feelings about flamenco,

and let you rise above the purely physical into a spiritual union with flamenco. The union with flamenco of which I speak is the art of flamenco. It is the facet of flamenco that not only moves you, the performer, but makes you the giver as

others are moved by your expression of flamenco. Art, like the word spirit, is something that

rises above what could be considered the norm. It can be a personal expression so powerful that others are affected in a very positive way, even if not in accord with your feelings. A great painter can be considered universally a great artist, such as was Leonardo da Vinci, but that

does not mean everyone universally appreciates or loves his work — his art. No matter; art, spirit and love are vital ener-

gies that, once experienced, no matter how little

or how nebulous, change our lives with some sort of meaning and indeed give meaning to life. How does one connect with the spirit? How does one’s spirit connect with the spirit of flamenco? How does the seed of the spirit, the flamenco spirit, grow with the rest of one’s being? First of all, there must be a ‘gut feeling’ that flamenco is indeed some part of your life. You must feel the seed stirring. You must go to it, for it will not come to you. It’s like mining gold — you have to move tons of earth for each gram of gold that it yields. You must be willing to move yourself, to be moved, to give of yourself to the art form with a total desire before it will flicker the spiritual flame, the spiritual life force in your being. There must be a deep respect for your feelings about art, seasoned with humility, reverence and inspiration, no matter how small or how frustrating. There cannot be time and space involved with the awakening of the spirit. When you become involved with the art of flamenco and begin to study, move, train, ex-

press, awaken your body as an expression of flamenco dancing, you will find the inspiration will come in various levels and degrees. You cannot wait for inspiration. You must awaken it by doing, and the doing will give birth to flashes of inspiration. Just as we brush our teeth daily, or eat or walk daily, we must also

have part of our time dedicated to our creative involvement with flamenco. I have frequently been asked, “How does

one become a flamenco dancer, a fine dancer, a

dance artist?” I often want to give a simplistic answer such as the sculptor Rodin gave to someone when asked, “How does one become a sculptor?” He answered, “Oh, it is easy, just acquire a block of stone and knock off what you do not want.” If a person is going to flower into a great dance artist of flamenco — and I’m referring not only to people born into the ambiente of flamenco, which of course gives them an edge in some aspects of this art, but to anyone who is moved by flamenco — that person must act on his initial inspiration. In dance, training the body and mind and, yes, awakening the spirit will ultimately be the sustaining force that will help on the continual search for artistry, ‘becoming the dance’. From initial inspiration can come frustration. As we develop the discipline of training our bodies to express flamenco movement, that movement will relate our truest feelings and

emotions, our selves through flamenco.

Inspiration will dribble in as we awaken

control, as our bodies become tuned, our muscle

memory develops and our movement becomes our own. Our discipline in training will be a beginning indication that our spirit is plugged into the spirit of flamenco — our art form to express, to live, to breathe, to be. Our frustra-

tions will only be a shedding of skin, so to speak, and will ultimately, if we persevere, let us experience a more beautiful form. The discipline in practicing, thinking and studying flamenco will be more than pure willpower

or surface desire. It will be a need,

a

hunger, not for fame or a name in bright lights, but a hunger to know your spirit. It will be craving as strong as a physical hunger for food. It will be food for the soul — that resting-living place of the spirit. There are no shortcuts to spiritual growth or

awareness. We tend to accept the patient growth and awareness of an enlightened spirituality in religion, the priest studying and praying for a lifetime for spiritual guidance, the Buddist monk in daily meditation, the Zen student with no thought of time and space in his meditative search for enlightened spirituality. So itisin thearts, and that is the way it should be. In flamenco, the touch of the ‘demon or angel’, the becoming of the dance for one lightening flash of time, the kiss of duende, usually

comes (if it is going to come) when it is least expected. It may come followinga long period of immersion in flamenco, where desire and love

of the art have become one with your being and a level of technique has taken hold so that you can literally ‘forget’ as it evolves out of your being. This flash of spiritual awareness and enlightenment will be a change in your life forever. Yes, it will be that dramatic when it happens. It will bea ‘high’ that no drug has ever been able to produce. It will be the purpose of your co-creative existence on this earth. Ilike to think that this experience will have a very positive effect on the person. I like to feel that a person in tune with their spiritual, artistic growth will know where their ego is, and know no envy or bitterness or petty jealousies, and be a better person for experiencing a true deep purpose. I’m not naive and I know this is not always the case; but it is the ideal, the positive desire of a spiritual search and awareness. Another compensation for spiritual enlightenment in this beautiful art isa sense of inner joy, the renewing force in life. It is a climactic high as different levels are reached with ongoing continual study and involvement. Everything will have meaning when you dance. Each planta can be an expression of something felt, like the subtle sensation of fine season-

ings. Your search will slowly be for the essence of your feeling of flamenco. It will not be in quantity, but in quality. When the conscious focus on spirituality becomes an unconsciousact and you realize that there is something beyond the steps of dance and beyond the dancer, then your total being will begin to exude this spiritual air. This, then is a very beautiful beginning to the high points of life itself and its purpose. It is nothing that you can or even want to touch or analyze. It will be... We, our total

physical, mental, emotional.and spiritual self, will be as one. We cannot take it for granted, for humility, deep down, will hold our personal perspective of life together. We must not let our being atrophy with disuse or misuse. We must be true to ourselves and our art, our spiritual connection with flamenco. That is what will keep flamenco alive and well, within us and without us.

All of this may seem far-reaching — but why not? Why not reach for the ultimate in ourselves? Nothing is out of reach if your goals are to be yourself in your true capacity. The concept of spirituality as the golden

thread that runs through life, art and love is, of

course, a personal feeling as a concept, superbly special. Everyone has his own explanation of spirit. Almost every culture has a word for the spirit or something higher than ourselves, something valid and worthwhile to ‘plug into’. Flamencocan transport usintoa realm higher than ourselves. The inspiration from a single movement, a musical sound, a verse of song, can

move one to feelings and emotions of ecstasy. Inspiration can come from countless sources within and outside of our being. It is not something you can wait for. Inspiration comes to one with love of life, of the art of life, of enjoying our

co-creativity with life, with flamenco.

Should the time arrive that you know you

have become the dance, the aire of the dance, that

your dance is more than your body movement, then you will be addicted to the art of the dance. Your spirit will be plugged into the meanings of your life. Although the dancer’s body may grow old, the spirit, kept ever-young by the love of life and flamenco, will be able to inspire others and giveinanongoing pattern of co-creative growth. As long as there is one soul on this earth with a true spirit of flamenco, a love of its essence, its art and life force, there will always be flamenco.

Spirit does not die. Spirit is, and therefore flamenco is. The flamenco spirit, like the spirit of life itself, has always been. In the finale, it will be our spirit dancing, moving our being in truth. Again we will know the meaning of life itself. We will become the dance, the dancing spirit, the true spirit of flamenco.

Teodoro Morca stretching to the sky

10

Zen and the Art of Flamenco Our body is the tree of Perfect Wisdom,

And our mind is a bright mirror.

At all times diligently wipe them,

So that they will be free from dust.

— 7th Century Zen verse

As children we were spontaneous. We were able to be ourselves, improvising in play and make-believe. We showed honest emotion and genuine delight in discovering ourselves — our bodies as they learned to move, our minds and feelings as our emotions awakened in laughter and crying. Our “mental cup' was empty, ready and eager to accept new experiences. Zen calls this a ‘beginners mind’. It is well to approach flamenco with the same empty cup, the same readiness to learn who weare, what we

feel and how we do. We seek honesty, spontaneity, freshness, inspiration and, yes, enlighten-

ment.

Zen and flamenco are really one without trying. They are of the same essence. They were born with the same roots. From both Zen and flamenco springs nota philosophy, a doctrine, a set of rules or a line of stone walls, but spontaneity of each moment. Wecan become life itself so that our dance can just dance, our breathcan breathe,

our feelings can feel, so that our individuality is unique yet a part of the whole, like a river blending with the sea. Zen is basically self-enlightenment. We are we, dance is dance, life is life. There’s no deep philosophy, just moment-by-moment living, each day full with spontaneity and calm. Our oneness is with all. There is no separation, no duality of physical and mental, just being. There have been many books and articles written about Zen and its relationship to creative endeavors (archery, martial arts, jogging, tennis, golf, skiing, even motorcycle maintenance). These basically are paths to knowing thyself. Any creative discipline is helpful in learning to become one with your total self. Flamenco enables the dancer to know himself or herself in the most intimate, enlightened

way. When you go to Spain, to the cradle of flamenco, you will see and feel the earth, the sky,

the peoples. You will sense the history, the richness and poverty of cultures, the pain and pleas-

ures, the joys and sorrows, the aire and gracia of

the ambiente that is the womb and the freedom of

the art of flamenco. Flamenco dance is move-

ment that expresses the ambiente. When we study

dance and reach a singularity of being with the compas and the basic disciplines of the technique, we are interpreting all the facets of this

flamenco ambiente.

Flamenco has been called a ‘mature’ form of dance. Federico Garcia Lorca noted its depth and profoundly ‘black rhythms’. This may be so in part, but it is also inborn in children. Watch children, any children, and you can see true spontaneity, inspiration and uninhibited improvisation. Before there was even the word, flamenco people were expressing themselves in flamenco movement, singing flamenco songs and beating out the many accented rhythms that are now called flamenco compas. I personally have seen some of the most moving, mature and pro-

foundly dramatic flamenco dancing done by

children. Children of the ambiente are great teachers of the essence of the art. When flamenco moves you to its beck and

call, you start out childlike in your feelings and

movements. You may be backward in your search, running on pure inspiration. Withempty cup, your instinct and intuition will shine the

way. You will find movement that you will

study, practice and count out. You will become mentally awake and even analytical, and witha

strong awareness and desire, develop a tech-

nique that will speak flamenco. One day when you least expect it, you will dance and come full circle. Your enlightenment will be in a flash, a child reborn. Your empty cup will have overflowed with the essence. You will be flamenco, you will have become the dance. It will be inspired, spontaneous and improvised with a knowledge learned of the soul, the soul of

the ambiente that gave it all birth.

11

In Respect of Tradition Tradition: Time honored, cultural continuity. A base for creative inspiration. Tradition gives meaning, even when stretched to its limits. The word tradition or traditional has a great sound to it, a marvelous ring of purpose, integrity and worth. It sounds old, but worthy of being new because it has lasted. In reality it is ongoing, forever new. Tradition is forged from expression and inspiration. In the case of an art form, it is forged from the art of individuals and groups that had an almost divine power or purpose, giving birth to something unique and worth following by others. Tradition is a seed that becomes a taproot in the creative arts. Flamenco’s long, deep taproot was sent down through generations by many peoples and cultures. It expresses a truth of feeling, emotion, art and creativity. Knowledge of tradition is a beginning, a springboard to finding one’s own connection to that tradition. In the 20th century, flamenco has branched and traveled from its native Spain to all corners of the world. People from almost every country have grown to accept flamenco music, song and dance as not only Spanish, but as a worldly art form. They have accepted the fact that you need not be Spanish to study the timeless tradition of this art, influenced by many cultures. Flamenco

is now influencing many cultural art forms, from contemporary music to jazz dancing. Webster’s Dictionary says that tradition means “time-honored, cultural continuity”. The time-honored flamenco tradition, with its long continuity froma birthplace ina rich fountain of culture, deserves great respect. It has surpassed itself in its speciality, its worth, its art, its sub-

stance. Time-honored does not mean stagnant;

rather, it is a perpetual fountain, an oasis, for-

ever giving new purpose. In modern times, this tradition is a stepping stone to one’s own indi-

viduality. When one respects what is and has been, one can be true to the art and true to one’s self as an individual expressing that art. Tradition has many facets. I think of tradi-

tion when I read Frederico Garcia Lorca’s dissertation on duende. When Lorca tells the story of

Pastora Pavon, ‘La Nina de Los Peines’, the fa-

mous flamenco singer singing for an elite group of flamenco aficionados, he writes, “After singing a few songs there was mostly silence, muted applause, and one person sarcastically shouted ‘Viva Paris!’ with intended guasa (sarcasm). With this challenge, she again sang, bypassing her own technique — her own muse, and ripped her voice to reveal the true duende, which also revealed the true marrow of flamenco.” This primary birth is the meaning of flamenco in the first category, raw tradition to the core. In this day and age with so many artists, so many people stretching flamenco in all directions (flamenco can be stretched and still reveal its traditions), where can we find this tradition to

respect? With so many rock arrangements, electric guitars, organs and interpretations resem-

bling all forms of rock and roll, where can we get

to the source? Where can we study tradition and get past the steps and really get to the roots so we can understand the art form better in its natural form, in its intended uniqueness? Obviously, there is no single answer. It’s a question thatall those studying flamenco should ask themselves. They should start to use their instinct, intuition and desire to find it for them-

selves. It may be necessary to go to the source, to the ambiente of flamenco — to the back alleys of southern Spain. I have always felt the importance of going to the flamenco ambiente, to the birthplace of the

tradition. This, along with the instruction of knowledgeable artists and a strong inquisitive nature,

will help bare the roots of flamenco.

More osmosis than pure analysis, it isexperiencing the why, what, where and how by doing — not only by asking or studying. Respect

for tradition

seems

obvious,

but

many times we bypass this foundation because we get caught up in the now, the immediate titillation of movement.

Tradition gives substance to the now. It is the backbone of today’s flamenco. All great artists who have found their unique style and expression of flamenco have started with a deep

12

immersion in tradition. Then, using tradition as a base, they have found their own path and in reality have expanded tradition, giving new life in a multi-faceted, ever-changing expression.

I often find that when I am choreographing

and trying to be inspired and creative in movement and individuality, I ask myself, “What is this solea por bulerías? What is its tradition saying to me personally?” Usually this helps me to hear it, feel it, and express it with truth and integrity and with better understanding. I keep going back to the source. Some people have had an almost divine awareness, a power of purpose that creates tra-

dition. The ancient Greeks had it, they inspire thinkers and artists to this day. Individuals have had

it, like

Michelangelo,

da

Vinci,

Bach,

Beethoven and Carmen Amaya, Martha Graham, Balanchine. The list is endless and ongoing. When one is inspired by a tradition and by people who make tradition, this is the springboard for personal artistic growth. This is the ongoing addition to the tradition of the art. Each person who expresses the tradition of flamenco in his or her own way, with respect to the source, adds to that art, just as each drop of rain adds to the ocean.

In today’s flamenco, there are some hard-

core traditionalists — people who want no

change at all from the flamenco world of long ago. On the other side of the coin are those who feel anything ‘old’ is out of date, worn out, of no

present use. They believe that ‘modern’ is what

is ‘in’, and should be representative of flamenco in today’s age of electricity, computers, namebrand fast food and clothing. I feel that both of these approaches are black-and-white, with no

room for a gray-scale. First of all, no one truly knows the flamenco of long ago, nor even how the bulk of present-day forms were crystallized.

Flamenco tradition breathes and is alive, is old and new, for these are the head and tail of the

same art form. So-called ‘modern’ dance is very healthy because itis an art formin search of itself through its interpretation. It is a healthy union of old and new

that breathes life into life, into art, into

flamenco. It is the gray area, the shining gray of a stallion, a healthy, living and breathing breed of flamenco which respects its ancestors, its traditions. Yet it rides with an age-old aire y gracia y orgiillo (hauty pride) into today’s world, where flamenco

is now,

where

it is born and born

again, forever new, with a living love that sings “Ay!”

Flamenco — Timeless Ongoing — It Is I would be surprised to meet anyone not in

awe of the wormy caterpillar which eats for a while then spins a cocoon and later emerges asa stunning butterfly, ready to fly, transformed into a creature of timeless beauty. A parallel can be drawn within the world of

flamenco. Here too, there is timelessness and constant change, both in the person and in the

art form as a whole. Flamenco’s unchanging taproot is planted deep ina very old tradition of many cultures, with many feelings and emotions. Like a very old and handsome tree that is strong of trunk and root, it is forever growing new branches, each one reaching out and away,

adding to the total quality of the tree, but still

drawing on the power of the deeper roots for its very survival. We often hear mention of ‘old style’ and

‘modern style’ flamenco, referring to the form and content of guitar playing, dancing, and also singing. Many times Iam asked whether I dance new or modern flamenco, and does such-and-

such guitarist play in the new style or old style, as if one style of an entire art form were better than the other. Wecontinually hear a differentiation between ‘old flamenco’ and ‘new flamenco’, but in reality it is all the same flamenco in an ever-changing form. As if one facet of the evolution of the art could encompass the content of the whole, or the origin should be disregarded as too old-fashioned and no longer representative of the art. When getting into the so-called styles, old or new, it is important to study as many aspects as possible. It is much like the turning of a kaleidoscope

13

makes a myriad of complex patterns, with only seven pieces of glassinit, each subject to individual interpretation. The basic rhythms and structures of flamenco have been well established for a very long time; within these rhythms, there is an infinite series of possible rhythmic patterns. It is always exciting to see and hear the creative process of guitarist and dancer in search of another rhythmical pattern, another series of contra tiempos — perhaps a (tongue-in-cheek) search for the ‘ultimate contra tiempo’ or for the dancer, the ‘ultimate desplante’. It is this very search that gives flamenco its dynamics of change. For the dancer, it is a search for other ways of movement within the tradition. There is so much to draw from. I really feel that flamenco offers unlimited creative growth potential, being such a varied and complete dance form with so much room for personal creative search. With so much history, so many cultures, each adding to the whole, the dancer can forever blossom. Much of the change that has taken place in the dance of flamenco has been in the technique — both the movement of the whole body and in the audible rhythms such as footwork and palmas. Most of this change comes from very strong, creative individuals whose influence has been such that their styles have forever altered the flamenco styles for the rest of us. One very strong influence for the male dancer

would think while watching the waves come in and go out that they never repeat the same shape, always assuming different patterns and rhythms, yet coming from the same ocean — the same water, but always changing. I would think that when dancing flamenco, try to let it be everchanging, letting the soul search for new means of expression within the boundaries of whatever rhythm I was doing. It is always exciting to see the changes in trends of flamenco, especially in the dance or the costuming, to see the pendulum swing back and forth between style or approach, and to see who is influencing the dance at any particular time. A few years ago, when it was the style to dance extremely slowly, the soleares of a great artist like Maria Soto was pure dramatic joy. It was a slow style that very few people could do because it required tremendous inner understanding and strength. To dance really slowly with knowledge and control, your art really has to be in order. Everyone in the early 1960s was dancing super slow. There were periods before that when it was the style to dance super fast. You could see bulerias done at 100 miles an hour. There have been trends of footwork only, where the rest of the body has been sacrificed, or trends of standing for long periods of time, doing just braceo, emoting much drama. There were trends of just dancing in contra-tiempos,

individual who was loved by many and thought crazy by others. Without a doubt, he was one of the strongest and most influential forces in the evolution of male flamenco dancing. He was a scholar who wrote books about his thoughts on dance, drew very modern and abstract drawings of his dance styles, and set down in writing a sort of “Ten Commandments’ of flamenco dance. He considered himself the tower and pillar of old and profound flamenco, yet it is interesting that this very style was the greatest influence for Antonio Gades, whose styleis very contemporary and has influenced much of the male flamenco dancing of recent years. I remember when I was touring Spain with Pilar López. We were on the Mediterranean coast during the summer festivals, and almost every day I would go to the beach in the morning for some sun and a swim. I would think of the stories of Carmen Amaya, how she had said that the sea was such an influence on her. And I

for the women and street suits for the men. Now the trend is to dance a very set ‘routine’, with steps set beat-by-beat with the falsetas of the guitar, much like composing music. You almost have to be working with the same guitarist for a very long time and also have great control over your emotions, trying to reach the exact same effect every time you dance. All trends show a search. They are good for flamenco, non-stagnant. From a total blend of trends and fads comes much creativity and that is what all art is about. I use the word ‘art’ as the ultimate creative expression of flamenco, yet never changing in original feeling, in the original purpose of expressing man’s highest ideals of his being. If one studies as many types of flamenco as possible, then by absorbing as much inspiration as possible from each, absorbing the depth and energy fromoneand the complicated techniques of another, a complete individual artist will be

was the late, great Vicenté Escudero, a unique

and trendsincostuming, with very short dresses

14

formed. Over a long period of time and through constant study of the subtleties and evolution of the art, you will stay timeless, not old or new, but an artist of the present, a blend of all, and you

will be fresh, honest and you! If we always think of flamenco as a whole, its totality in energy, feeling and emotion, with dynamics and expression coming through the techniques, then no matter what the style — simple, complex, fancy, old or new — it will be true and ‘say’ something.

menco

in his own

way.

Art, feeling, emotion,

and energy do not change — only their expressions change. When one approaches flamenco asa performing art which includes dancer, singer and guitarist, one approaches the tradition of flamenco at its roots. The base of flamenco is the compás, not only each rhythm and its style, but its interpretation,

None of this is old or new, but timeless fla-

its feeling and emotion, always in its totality. Dancer being sensitive to musicand song; singer being sensitive to music and dance; musician being sensitive to singer and dancer. With a

Gastor, Paco de Lucia, Nino Ricardo or Sabicas,

interpretation together, a solid understanding takes place of the tradition of the roots of flamenco. [learned long ago that being Spanish or non-

menco. The essence of flamenco is a timeless expression of all human feeling brought out through an art form. This timelessness goes for the guitar also; whether the player is Diego del

they are all playing and expressing a different and individual facet of the whole art of flamenco. The cante is the most timeless part of flamenco and, whether the singer is El Chocolate or Camaron, it is cante flamenco, period, no matter the individual style or approach to compás. Many of the older transitions in flamenco dance are coming back, and to me that is beautiful, for tradition is the glue that holds much of the art together while it grows with inspiration and intuitive and imaginative evolution. For example, a few years ago when I was dancing in Spain, I asked a guitarist to play the old ida transition of alegrías to bulerías, a noncountable bit that the guitarist plays while the dancer does a set series of movements to this ida. He laughed at me and said that “was really too antique.” Now, I see it revived everywhere, from the teachers at Amor de Dios to the National Ballet of Spain. There is no limitation to this beautiful growing art; it is life itself, ever moving.

Flamenco

cannot change — it is! It is the individual interpretation that changes and each person that is involved in flamenco will express and live fla-

foundation of learning flamenco technique and

Spanish is a frame of mind when approaching

flamenco. Flamenco in its totality is a creative and expressive art form and therefore, universal to all who want to absorb and feel and live it. The point is that flamenco is total involvement, physically, spiritually, emotionally and mentally. Until one learns to lose himself, he cannot find himself. When you can become at one with all of the facets of your being with innate understanding, and become the dance,

the music, the song — then the word duende will have meaning. Let us take this beautiful tradition and not stop its flow by limited understanding and narrow-minded criticisms. But let us take tradition as a base for individual creative growth. If you feel like lifting your arms to the sun, like the wings of an eagle, then stretch with inner joy. If feeling comes over you, then feel — feel your feelings. If movement comes over you — move. Be sensitive to the compás, to the song. Be bathed in the totality of flamenco —which in all essence and reality is really the dance of

life, the song of life, the music of life in all of its

glory.

15

Technique, Craft and Art Having taught and performed for many years, lam often asked the question, “How long does it take to become a dancer?” and specifically, “How long does it take to become a flamenco dancer?” I find myself at a loss for words to this question. Trying to answer it in a few short sentences invariably leaves the other person just as mystified as before they asked. What does it take, what is becoming a flamenco dancer? If I give the answer in the number of years of study — 10 years, as most ballet teachers say — then 10 years of what? What is at the end of 10 years? Flamenco by its very nature hits an emotional chord in most people who first discover it. It can even look easy in its subtle moments. Years ago, I was teaching in Los Angeles in the days when Spanish dance companies passed through quite regularly; companies like José Greco, Roberto

Iglesias, Carmen

Amaya,

or

Jiménez-Vargas. I would get phone calls from people who had seen the concerts and ‘loved it’ and ‘felt it’ so much that they wanted to dance that flamenco.

They wanted to dance one of those ‘tarantos,’ as

one girl put it. Some of these people would come to dance class, and when

they found out that

there was much more to it than a few quick and easy lessons, they would melt away. Some of these people told me that they ‘felt it’ so much that they did not need or want technique, or want to bother learning the music or steps. I found myself saying, “Fine, when you go out on stage and ‘feel’ and ‘emote’ in front of an audience for five minutes, then what? What are you going to do for the rest of the performance?” It is the then what that I want to talk about here. Whether you are an aficionado wanting to do a few steps in a fiesta or a dedicated professional, it is desirable to understand technique,

craft and art. Good technique is essential to any craft. Through technique, one can eventually unleash the art that is the essence of flamenco. A good foundation can be developed by working on and understanding the basics of movement,

as applied

to flamenco.

A

total-

movement approach is important before one should think of getting too complicated. If one

can do simple things perfectly, itis possible to do difficult techniques easily. Talking about technique in relation to flamenco is like talking about religion or politics, there are as many opinions as people. Some would say too much technique takes away from the art. Technique is the vehicle that expresses the art; just as a hammer and nails are not the house, but tools used to build the house. There is no such thing as too much technique if its purpose is a sincere approach to artistic expression.

Flamenco is visual movement. Flamenco is the bloodstream of dance,a form involving every part of the body, with no one part of the body moving without another. Flamenco has all of the facets of every other dance art and more, it calls for a total approach from the beginning. It is not just grabbing a skirt or vest and pounding away at a footwork combination. It is a posture of the body that sings of the ages, of proud races of people, past and present. It is arms moving, expressing a reach for love, life, death, challenge and rebirth. Itisa head held high, like the phoenix rising; it is earth and sky. It is movement

and

non-movement,

like the

appearance of a distant star that, though it appears still, is moving through eternity. It is audible music, footwork interplaying with a joyous surface, a love — the making of sound against sound, of palmas (hand clapping), footwork, pitos (fingers snapping), caressing our listening senses with passion and life. Your craft comes from rehearsing, practicing and more practicing until your technique has flow. Using your technique to ‘say something’ comes from the good fortune of many things, such as properambiente to learn the meaning and understanding of what flamenco is to you, studying with teachers of dance who are sensitive to your individuality and to all of the other elements of the music and song. It comes from understanding individuality, phrasing, clarity and all of the qualities that enable you to become one with the music, the dance, the song, and the

total feeling of that you have Much has used are often

flamenco — the personal feelings in regard to flamenco. been written on art. The words the same words used to discuss

16

love. Art is difficult to explain in words; it is more easily expressed in feelings. Itis the craftof

an art form that is most often seen, not the art

itself. It is this beautiful difficulty of just “turning on the art’ that makes art so rare and precious and worth striving for. Professional performers, performing night after night, traveling hundreds of miles and then giving a concert, often rely on their craft to present the art form in as beautiful and exciting a manner as possible. The audience sees a very controlled and exciting display of technique, of music, song and dance, ‘turned on’

by many years of experienced craft, even though the performer might be tired or sick. I was told an interesting story by a very fine guitarist who was visiting Sevilla. A Gypsy

dancer was performing atone of the tablaos. This. dancer was well known for his ‘great art’ when conditions were ‘just right’ ... but the right conditions were very unpredictable. The guitarist went night after night to see this

dancer for a week, he saw the dancer perform

nicely, but nothing to really excite the bloodstream. The guitarist was getting ready to leave Sevilla, but decided to go one more night to see the dancer of whom he had heard so much, and

it happened. He told me, “The soleares he danced

made people rise out of their chairs, the air was like a vacuum ready to explode, the dancer was possessed and in turn possessed the audience who could not even breathe.” It was the most moving ofall experiences, it was dance that transcended dance, it was Art.

Dance becomes art when it transcends technique, when craft carries movement to greater heights where it intertwines with the soul, the meaning of all creativity. Art is a giving process. Everyone has some creative expression of nature, of life. When a person who carries a bit of dance in his being followsa path of creative growth, then the flower of art will appear in his dance, and he will know the meaning of creative life.

In-tune with Technique

The human body is indeed a remarkable instrument, with the ability to express a wide range of feeling, expression, emotion and communication. With today’s many categorizations, the art of human expression can be labeled bal-

let, mime, sports, modern, post-modern, folk,

ethnic, jazz, tap, etc. With many shadings of technique to express any one particular labeled

category.

The human being is one of the only creatures on earth that has sucha wide range of adaptable expressions. Before today’s categorization, men and women expressed themselves and their feelings with dance. The techniques of flamenco dance have evolved from many sources that are unique and have become more unique in their blending. The total involvement of the body in such a blended abstract way is only rivaled by the dances of India. The approach to flamenco technique should be, every part of the body saying something, not favoring one part over any other. I have read, “Flamenco dance is based on the

footwork.” That would be limiting, like saying that ballet dancing is based on standing on your toes. Without frills, in its basic traditional ap-

proach, flamenco is an expressive blend of the

total body, communicating its visual and audible feelings and emotions. To have so beautiful an art form dissected — “he has good arms but lousy feet,” or “she grabbed the skirt and did some nice footwork, but her upper body lacked,” — may be valid critiques, but I feel that we should approach flamenco technique from all angles, from the first moment of study. Flamenco technique should involve the total body and this can best be approached from the upper body working down, like gravity. Just as a guitarist finds a good position of the hands to properly execute good fingering techniques, a dancer can start witha good posture so that this centering can relate to the rest of the flamenco body. Good posture is primary for the flamenco look, which will relate to the flamenco

feeling expressed with this look, this positioning. One of the main differences in look, from style to style and different dance forms, is the position of the head, shoulders and back. The initial aire and look of flamenco is a head held straight, not stiff, but back from the chin,

like the look and position of a proud eagle. Tilting the head gives it a classical look which changes total character. Shoulders are down and natural, giving the feeling of presence, of a secure estampa. When at a diagonal, the downstage shoulder could be slightly higher than the

17

up-stage shoulder. This keeps you from looking stiff and at the same time maintains the look of flamenco. I cannot completely explain this look, but itis the total proper positioning of the body that best represents a particular flamenco style. Over many years, when dancers have become involved almost exclusively with the footwork of flamenco, the habit of looking down has become popular. This habit breaks one of the most important flamenco lines — the head; the

head has to do with the focus, that all-important focus of the eyes. If you looks down asif concentrating on the footwork patterns, then look down with only the eyes, thus keeping the beautiful

line of the head held up, held in the position that

gives strength of focus and not a hunchbacked effect.

The back should be a total, natural curve

from lifting the torso; not a swayback with the behind stuck out. Our behind is already prominent by the way we are built. If you lift the torso, tummy in with shoulders back and down, the hips held naturally, you will best find the flamenco back, the line that lets you move naturally flamenco. One of the most exciting discoveries in flamenco technique is finding your personal asentao position. It is not only your bent knees, but it is that opposition in movement that lets your uplifted torso float, your hips move and adjust smoothly and releases your legs so that your movements, your footwork, will work the best

for your body. No one can tell you how far to bend, because this position should be completely integrated with the rest of the body. It is exciting to explore the techniques of flamenco that come from obvious natural movement. For example, walking, where your arms

move in opposition to your legs. It is interesting that many times in flamenco walking movements this naturalness will be ignored and will give the appearance of a stiff movement. Natural opposition is a great beginning in line and linear movement which lend immediately to the basic movements that flamenco tries

to express. There is nothing more exciting to a

teacher than seeing a student respond to the basics and make them work personally. There is a snowball effect when studying flamenco technique in a totally integrated way.

Once we get the basics all moving together within the realm of our own bodies and within

the realm of the various flamenco forms, then

the muscle memory starts to work along with our physical, spiritual, emotional and mental self. It is beautiful to see and experience. It is very interesting that in many of the

Oriental martial arts, (which have similar roots

and approaches as flamenco), that when one promotes to a technically higher level in degree

of understanding, whether absolute beginner or

grand master of many years training, the basics are the same. The promotional movements and techniques are the same for beginners as for advanced. The basics are all important and the so-called more advanced student is expected to do the basics with more understanding, more perfection, more simplicity and economy. This is indeed profound when one thinks that in the arts,

in flamenco, it is the ability to stand still with art, it is that quest for the essence of technique in its purest form to speak flamenco truth. Why do some of the greatest artists, flamenco artists, do the least physical movement?

Because they have learned to ‘become the dance’ — totally. Every facet of their self has been

focused to that essence, that personal reflection of flamenco art in its purest form. This, of course,

can encompass a lifetime of your personal involvement in and your approach to flamenco. When one is born into the ambiente of flamenco, there is a much more natural osmosis,

absorption and adaptability to the technique, which is part of the total mannerisms of the cultures that gave birth to flamenco. For people who are not born in Spain or into other pockets

of flamenco, there is still that universal element that is in all art; the love and need for that art

form to be a necessary part of our lives.

Working from the Top Down