Alain Delon: Style, Stardom, and Masculinity 9781623567606, 9781501300264, 9781623561574

Few European male actors have been as iconic and influential for generations of filmgoers as Alain Delon. Emblematic of

220 119 7MB

English Pages [220] Year 2015

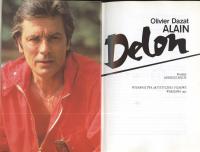

Cover

Half-title

Title

Copyright

Contents

Notes on the Authors

Acknowledgments

Introduction: Alain Delon, Then and Now

1. On the Limits of Narcissism: Alain Delon, Masculinity, and the Delusion of Agency

2. Delon and Performance: Emploi and the Interaction Between Individual, Role, and Character

3. France’s “new Don Juan”: The Representation of Alain Delon’s Youth

4. Dubbing Delon: Voice, Body, and National Stardom in Rocco e i suoi fratelli/Rocco and his Brothers (Luchino Visconti, 1960)

5. Delon/Gabin/Verneuil: Modernity within Tradition

6. Alain Delon, International Man of Mystery

7. The Star’s Script: Delon as Director, Producer, and Screenwriter

8. The Singing Actor: Delon on Record

9. Dressed to Kill: Delon, The Style Icon

10. Toujours Delon: The Script of Aging

Bibliography

Index

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Nick Rees-Roberts

- Darren Waldron (editors)

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

Alain Delon

Alain Delon Style, Stardom, and Masculinity Edited by Nick Rees-Roberts and Darren Waldron

Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Inc

Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Inc 1385 Broadway New York NY 10018 USA

50 Bedford Square London WC1B 3DP UK

www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 Paperback edition first published 2017 © Nick Rees-Roberts, Darren Waldron and Contributors, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN: HB: 978-1-6235-6760-6 PB: 978-1-5013-2012-5 ePub: 978-1-6235-6445-2 ePDF: 978-1-6235-6157-4 Typeset by Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd.

Contents Notes on the Authors Acknowledgments Introduction: Alain Delon, Then and Now Nick Rees-Roberts and Darren Waldron On the Limits of Narcissism: Alain Delon, Masculinity, and the Delusion of Agency Darren Waldron 2 Delon and Performance: Emploi and the Interaction Between Individual, Role, and Character Laurent Jullier and Jean-Marc Leveratto 3 France’s “new Don Juan”: The Representation of Alain Delon’s Youth Gwénaëlle Le Gras 4 Dubbing Delon: Voice, Body, and National Stardom in Rocco e i suoi fratelli/Rocco and his Brothers (Luchino Visconti, 1960) Catherine O’Rawe 5 Delon/Gabin/Verneuil: Modernity within Tradition Leila Wimmer 6 Alain Delon, International Man of Mystery Mark Gallagher 7 The Star’s Script: Delon as Director, Producer, and Screenwriter Isabelle Vanderschelden 8 The Singing Actor: Delon on Record Barbara Lebrun 9 Dressed to Kill: Delon, The Style Icon Nick Rees-Roberts 10 Toujours Delon: The Script of Aging Sue Harris

vi x

1

1

Bibliography Index

13

31

43

59 75 91 111 125 141 159 175 185

Notes on the Authors Editors Nick Rees-Roberts is Professor of Media and Cultural Studies, University of Paris-Sorbonne Nouvelle (Paris III), France. His research focuses on contemporary French cinema, queer theory, and fashion cultures. He is the author of French Queer Cinema (Edinburgh University Press, 2008) and a jointauthored book (with Maxime Cervulle) Homo Exoticus: race, classe et critique queer (Armand Colin, 2010) as well as journal articles on gender, sexuality, film, and fashion. He is currently completing a monograph entitled Fashion Film in the Digital Age (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016). Darren Waldron is a senior lecturer (associate professor) in French screen studies at the University of Manchester. His research focuses on representations of sexuality, gender, and ethnicity in contemporary French cinema, popular film, and audience reception. He is the author of Queering Contemporary French Popular Cinema: Images and their Reception (Peter Lang, 2009) and Jacques Demy (Manchester University Press, 2014) and coeditor (with Isabelle Vanderschelden) of France at the Flicks: Trends in Contemporary French Popular Cinema (Cambridge Scholars Press 2007). He is currently completing a jointauthored monograph (with Chris Perriam) entitled French and Spanish Queer Cinema: Audiences, Communities and Cultural Exchange (Edinburgh University Press, 2016).

Contributors Mark Gallagher is an associate professor (senior lecturer) of film and television studies at the University of Nottingham. He is the author of Another Steven Soderbergh Experience: Authorship and Contemporary Hollywood (University of Texas Press, 2013) and Action Figures: Men, Action Films and Contemporary Adventure Narratives (Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), and coeditor of East Asian Film Noir (IB Tauris, 2015) and Scope: An Online Journal of Film and Television

Notes on the Authors

vii

Studies. He is currently completing a book on the actor Tony Leung Chiu-Wai for the BFI’s Film Stars series. Gwénaëlle Le Gras is an assistant professor of film studies at the University of Bordeaux 3, France. She has published on French stars, gender, and popular cinema, including two books on French stars in 2010: one on Michel Simon (Michel Simon, l’art de la disgrâce, Paris, Scope editions) and one on Catherine Deneuve (Le mythe Deneuve, une “star” française entre classicisme et modernité, Paris, éditions du Nouveau Monde). She has since coedited a volume with Delphine Chedaleux on genre and actors (Genres et acteurs du cinéma français 1930–1960, collection “Le Spectaculaire,” Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2012). She coordinated the dossier entitled “Quoi de neuf sur les stars?” in the online review Mise au point, no. 6, 2014 (http://map.revues.org). She also coedited an edition of Contemporary French and Francophone Studies entitled “stars du cinéma français d’après-guerre” (vol. 19, no 1, January 2015) and the edited book Cinémas et cinéphilies populaires dans la France d’après-guerre 1945–1958 (Paris, editions du Nouveau Monde, 2015). Sue Harris is a reader in French cinema studies at Queen Mary, University of London. She teaches across the Film Studies curriculum with a particular focus on film history and contemporary French cinema. She is the author of a monograph on An American in Paris in the BFI Film Classics series (May 2015) and has written widely on French cinema and popular culture. Her published work includes Bertrand Blier (MUP, 2001); France in Focus: Film and National Identity (edited with Elizabeth Ezra; Berg, 2000); Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination: Set Design in 1930s European Cinema (coauthored with Tim Bergfelder and Sarah Street; AUP 2007); From Perversion to Purity: The Stardom of Catherine Deneuve (edited with Lisa Downing; MUP, 2007). She has been an associate editor of the journal French Cultural Studies since 2001. Laurent Jullier is Director of research at IRCAV (University of Sorbonne Nouvelle Paris) and Professor of Film Studies at the University of Lorraine. He has written articles for Esprit and for Encyclopædia Universalis, as well as a dozen books, some of which several have been translated into English (see www.ljullier.net).

viii

Notes on the Authors

Barbara Lebrun is a senior lecturer (associate professor) in contemporary French culture at the University of Manchester. Her research looks at representations of ethnicity, gender, prestige and nostalgia in French popular music, with an interest in audience reception. She is the author of Protest Music in France. Production, Identity and Audiences (Ashgate, 2009), winner of the 2011 IASPM book prize for Best Anglophone Monograph, and editor of Corps de Chanteurs. Présence et performance dans la chanson française et francophone (L’Harmattan, 2012). She has published articles in France, the United Kingdom, and the United States and is currently working on a monograph contextualizing the career of female singer Dalida. Jean-Marc Leveratto is a professor of sociology at the University of Lorraine, France. His main research interests are in the study of cultural consumption as a “body technique” and in the history and sociology of the cultural industries (particularly theater and cinema). His most recent book publication is Cinéphiles et cinéphilies, coauthored by Laurent Jullier (Armand Colin, 2010).

Catherine O’Rawe is a senior lecturer (associate professor) in Italian at the University of Bristol. She is the author of Stars and Masculinities in Contemporary Italian Cinema (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014) and has published widely on recent and postwar Italian cinema. She is also the coeditor, with Helen Hanson, of the volume The Femme Fatale: Images, Histories, Contexts (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010). Isabelle Vanderschelden is head of French at Manchester Metropolitan University. Her recent research focuses on contemporary French cinema and film pedagogy. She has published articles on popular French cinema, popular stars, subtitling, transnational films, and comedy. She is the author of a critical study of Jeunet’s Amelie (IB Tauris 2007) and Studying French Cinema (Auteur 2013). She has also coedited with Darren Waldron (University of Manchester) a book on recent trends in French popular cinema France at the Flicks (Cambridge Scholars Publishing 2007). She is currently working on another monograph on French screenwriters with Sarah Leahy (Manchester University Press 2016). Leila Wimmer is a senior lecturer (associate professor) in film studies at London Metropolitan University. She is the author of a study of the critical reception of British cinema in postwar France entitled Cross-Channel Perspectives: the French Reception of British Cinema (Oxford: Peter Lang: 2009). Her interests include

Notes on the Authors

ix

French cinema history, cross-European and cult stardom, film reception, and cinephilia. She has published essays on Billy Wilder’s Mauvaise graine, the reception of Baise-moi, Jane Birkin as a Franco-British star, the cult stardom of Sylvia Kristel, and women’s cinephilia in French fan magazines of the 1930s in the journal Film, Fashion and Consumption in 2015.

Acknowledgments The editors wish to thank Katie Gallof at Bloomsbury for commissioning the book, Mary Al-Sayed for overseeing the production process, and Ginette Vincendeau for her encouragement for the project in its early stages. Nick ReesRoberts and Darren Waldron would especially like to thank Tim Rees-Roberts for logistical support in the final stages, and Nick Rees-Roberts thanks Silvano Mendes for personal support throughout the project. Barbara Lebrun wishes to thank François Ribac, Freya Jarman-Ivens, Kevin Donnelly, and Vladimir Kapor for their helpful advice and support. We also thank Palgrave Macmillan for their permission to reproduce “Alain Delon, International Man of Mystery,” which originally appeared in Transnational Stardom, edited by Russell Meeuf and Raphael Raphael and published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2013.

Introduction: Alain Delon, Then and Now Nick Rees-Roberts and Darren Waldron

Few male European actors have been as iconic and influential for generations of filmgoers as Alain Delon. In his heyday in the 1960s and 1970s, he was emblematic of a modern masculinity and a distinctive European style, a symbol of French elegance. Delon’s appeal has spanned cultures and continents, reaching as far afield as East Asia, where young men have imitated his look and mannerisms. From his break-through as the first onscreen Tom Ripley in Plein soleil/Purple Noon (René Clément, 1960), through two legendary performances for Luchino Visconti in Rocco e i suoi fratelli/Rocco and His Brothers (Luchino Visconti, 1960) and Il gattopardo/The Leopard (Luchino Visconti, 1963), to his roles as the laconic anti-heroes in three of Jean-Pierre Melville’s most celebrated film noirs—Le Samouraï/The Samurai (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1967), Le Cercle rouge/The Red Circle (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1970), and Un flic/Dirty Money (JeanPierre Melville, 1972)—Delon came to embody the flair and stylishness of the European cinema of the period. He was particularly associated with the French polar or crime film; his appearances opposite Jean Gabin in Henri Verneuil’s Mélodie en sous-sol/Any Number Can Win (Henri Verneuil, 1963) and Le Clan des Siciliens/The Sicilian Clan (Henri Verneuil, 1969) and alongside Jean-Paul Belmondo in a nostalgic revision of the Marseille criminal underworld of the 1930s Borsalino (Jacques Deray, 1970) bolstered his image as one of France’s most recognizable and popular film stars. A critical consensus has formed around the myth of Delon as a fragile but cruel beauty. The use of Delon’s photogenic face and slim body to advertise Plein soleil at the start of his career was spectacular. The young actor became a movie star because he was seen as naturally beautiful—his smooth skin, piercing blue eyes, symmetrical face and delicate nose, luscious hair and slim torso, all visually embellished by directors and cinematographers. Delon’s glamorous lifestyle added to his appeal. His tempestuous relationships, particularly with actress Romy Schneider, fuelled the celebrity gossip of the early 1960s. Delon

2

Alain Delon

epitomizes an ambiguous masculinity. His macho roles and archetypal playboy image were mitigated by his refined features and troubling gaze. In contemporary France, Delon is a contested and ambivalent figure, his likeability tarnished by his bombastic declarations, reported extremist politics, and pompous selfpromotion. He made the cover of Le Figaro Magazine in July 2013 and was included in a feature article on shifting models of masculinity, in which the aging star berated the gradual loss of gender differences and the recent French same-sex marriage legislation (Haloche 2013, 32–34). Given its spectacular prominence and problematic nature throughout the actor’s career, the issue of masculinity is a central critical inquiry in this collection. Delon’s youth included a prolonged period of military service in the French army in the early 1950s. He was born on November 8, 1935 in Sceaux, a middle-class suburb south of Paris. Following his parents’ divorce in 1939, he was placed with foster parents and then sent to various Catholic boarding schools, from which he was expelled. A turbulent youth, Delon signed up for military service in the French navy aged 17 and was posted to Saigon toward the end of the Indochina War. Looking back, he claims that this limited, but nevertheless formative, experience of war as a young man shaped his military temperament, providing him with rigor, discipline, and a sense of duty (Jousse and Toubiana 1996, 27–28). On his return to France, he lived in Pigalle in north Paris, allegedly using his charms to make ends meet (Dureau 2012, 11). But it was in the Paris left bank of the postwar years where the ambitious rising star was noticed, where he met young actors Brigitte Auber and Jean-Claude Brialy, with whom he left for the Cannes Film Festival in May 1957. Spotted by David O. Selznick’s talent scout, he was immediately sent to Rome to perform a screen test for the producer, who offered him a golden seven-year studio contract, provided he improved his spoken English. In a surprising decision that later sealed his fate in Hollywood, where he failed to make it in the mid-1960s, Delon returned to Paris, becoming the lover of Michèle Cordoue, the wife of film director Yves Allégret, who cast him in a minor role as the hit-man Jo in Quand la femme s’en mêle/Send a Woman When the Devil Fails (Yves Allégret, 1957). Delon’s early roles, up to his breakthrough in Plein soleil in 1960, tended to emphasize either an element of sexual availability or youthful bravado—he was a playboy in Faibles femmes/Three Murderesses (Michel Boisrond, 1959) and a schoolboy in Le Chemin des écoliers/Way of Youth (Michel Boisrond, 1959). Film scholars Ginette Vincendeau and Guy Austin have argued that Delon’s early persona was a historical product of advertising in the context of postwar

Introduction: Alain Delon, Then and Now

3

economic modernization. Vincendeau situates Delon’s body as a desirable, publicity-driven commodity, a product of 1960s consumerism (2000, 158–195). Austin reads Delon in contrast to his contemporary Jean-Paul Belmondo, highlighting his image as a remote outsider as key to his seductiveness for his audiences (2003, 48–62). Our collection extends the existing scholarship on the Delon persona, which also includes Graeme Hayes’s account of the actor’s spectacular masculinity (2004, 42–53), to consider historical, textual, and theoretical readings of Delon’s career, image, and persona, including a particular focus on the star in the context of transnational cinema culture and on the global reception of his image. Hence, the collection includes contributions, not only on Delon’s iconic performances, his famous affiliations and masculine image but also on less well documented aspects of his career, such as his early films of the 1950s; his international, English-language performances in the mid-1960s; his role as director, producer, and screenwriter; his later career on and off the big screen; his enduring role as style icon and his intermittent contributions to popular music. Before we provide an overview of the book’s rationale and orientation, it is worth situating Delon in relation to existing discourses of stardom and to the critical reception of his career in and beyond France. Austin defines film stars as commodities—“brand names, whose capital is their face, their body, their clothing, their acting or their life style” (2003, 2). Following Richard Dyer’s lead (1998 [1979]), Vincendeau defines them simply as “celebrated film performers who develop a ‘persona’ or ‘myth,’ composed of an amalgam of their screen image and private identities, which the audience recognizes and expects from film to film, and which in turn determines the parts they play” (2000, viii). Dyer’s original account of the golden age of Hollywood stardom emphasized the semiotic values and affective embodiment of classic film stars, their images or personae deriving from the “complex configuration of visual, verbal and aural signs.” Star images, Dyer argued, “function crucially in relation to contradictions within and between ideologies, which they seek variously to ‘manage’ or resolve” (1998 [1979], 38). Dyer’s description of the contrived projections of individual glamor, exclusive lifestyles and conspicuous consumption, juxtaposing the spectacular with the everyday (1998 [1979], 39– 43), drew on a previous account of stardom that had also bound the subject to consumer culture, seeing stars as mythic models of consumption for their fans to imitate. Edgar Morin’s early writing on stardom and popular culture coincided with Delon’s rise to fame in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Morin’s 1962 L’Esprit du

4

Alain Delon

temps (2008), presented as an essay on mass culture, engaged with many of the methodological questions that were to set the (more politicized) agenda for Anglo-American Cultural Studies in the decades to follow: the representation, value, and audience reception of emerging forms of popular culture (Macé 2008, 7–15). Morin’s earlier groundbreaking inquiry from 1957, Les Stars/Stars, had elevated film stars of the silent period to the status of icons, attributing them with quasi-mystical auras, seeing them as early twentieth-century equivalents of ancient divinities (1972, 36–64). The semiotic-cum-anthropological study of screen myths was, for Morin, located somewhere in the gray zone between belief and entertainment. But, as Austin observes, with the advent of sound cinema, there was a gradual shift toward the bourgeois accessibility of stars, “seen in villas, apartments and ranches. Magazine spreads feature their homely lives, their bourgeois interiors, their ordinariness” (2003, 3). Morin’s multidimensional account of stardom attempted to juggle critical attention to form, reception, production, and social context in an endeavor to translate the appeal and worth of individual film stars to audiences and fans. In his preface to the third edition in 1972, Morin retrospectively regarded the 1960s as central to the development of European stars such as Delon, Brigitte Bardot, and Catherine Deneuve, through the postwar economic boom that was conducive to the creation of a local starsystem fashioned around the beauty, glamor, and lifestyles of the chosen few. The on-screen Delon, the icon of a bracingly modern masculinity (following the release of Plein soleil in 1960) became so powerful off-screen through the decade that he was able to launch his own production company (Delbeau, later Adel Productions), coproducing and starring in L’Insoumis/The Unvanquished (Alain Cavalier, 1964), thereby having greater control in choosing his partners, screenwriters, directors, and coproducers. Delon’s financial worth outstripped that of Bardot, Belmondo, and Deneuve, making him the highest earning boxoffice star of French cinema of the decade (Morin 1972, 11). Historically, film stardom has relied for effect on the eroticization of the human face through the technological means of the close-up (Morin 1972, 120). The idea that the young Delon was troublingly beautiful has been articulated by many of the actor’s screen partners: Annie Girardot comments that Delon’s “insolent beauty” did not go unnoticed on the streets of Milan during the filming of Rocco in 1960; other men would turn in admiration at the sight of Delon and co-star Renato Salvatori walking arm in arm like members of a Sicilian clan (Dureau 2012, 29). Claudia Cardinale locates the actor’s beauty in his glacial gaze, restless physique, and ironic character; he was self-confident, sure of his

Introduction: Alain Delon, Then and Now

5

beauty, charm, and sexual allure (Dureau 2012, 38). Critics have concurred that his youthful physique and facial perfection shaped the Delon myth of the performer as a cruel beauty: “the association of Delon’s beauty with sadism is so recurrent that the conclusion is inescapable: it is his beauty itself, in its excess, which is cruel” (Vincendeau 2000, 176). Equally, Austin has described the actor’s fragile face as signaling a move beyond machismo, concerned with doubling and mirroring, notable examples of which include the disavowed homo-narcissism in Plein soleil (Straayer 2001; Williams 2004) but also more subtle takes on narcissism in Mr. Klein (Joseph Losey, 1976) and Jean-Luc Godard’s ultimate statement on the star’s split image in Nouvelle Vague/New Wave (1990), in which he replaced one vulnerable Delon with his more assertive and manipulative twin. Delon’s eroticized image remained “literally self-regarding” (Austin 2003, 62) even in the “gloomy fatalism” of a character like Klein. Losey’s disturbing narrative of doubling and imagery of mirroring balanced a passing nod to the actor’s former pin-up status with a darker revision of Delon’s self-image (it remains self-referential and inward-looking nonetheless), while Godard stripped the preestablished Delon persona away altogether. As a promising (though as yet untested) young actor in the late 1950s, Delon’s natural gifts—his ambivalent gaze, dynamic allure, and magnetic charisma— made him perfect for the charmingly ambiguous killer Tom Ripley in Plein soleil, a disturbed young man obsessed with surface image (Figure 1). He was initially cast as the millionaire playboy Philippe Greenleaf, Ripley’s victim, but convinced the director to risk giving him the lead. The young star’s pretty face was a mask

Figure 1 Delon as Tom Ripley in Plein soleil/Purple Noon (1960)

6

Alain Delon

for the actor’s technical versatility; his angelic boyishness would also suit the naiveté of the good son Rocco, the role he played straight after Ripley. Beyond the combination of tenderness and harshness, it was Delon’s athletic body—his slim silhouette, imposing gait, and agile movements—that evoked the dynamic restlessness associated with a modern model of masculinity based on an ideal of European elegance. The problematic obsession with the actor’s beauty when playing evil characters such as Ripley has led critics to posit an uglier edge, even a quasi-fascistic identification (Darke 1997), echoing Visconti’s inquiry as to whether Tancredi, the character played by Delon in Il gattopardo/The Leopard, would in fact have become a fascist by the early twentieth century.1 The actor was visually striking in the role of the prince’s opportunistic nephew in Visconti’s lavish adaptation of Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s 1958 novel, set in Italy of the mid-nineteenth century (Figure 2). Tancredi first appears on screen as a startling reflection in his uncle’s shaving mirror; the actor’s photogenic face, filmed without make-up, is prominently displayed before his body. The director was allegedly passionate about the actor, placing the relatively peripheral character (the cynical careerist; a man of his time unlike the fading prince) at the political heart of the film (Servat 2000, 73). The idea that Visconti symptomatically sublimated his desire for Delon through the embellishing cinematography of both Rocco e i suoi fratelli and Il gattopardo—as he is said to have done previously with Massimo Girotti in Ossessione/Obsession (Luchino Visconti, 1943)—has been questioned as a reductive assumption, underestimating the more complex ways in which screen technologies direct and codify visual pleasure to stabilize a hetero-normative gaze (Duncan 2000, 103–104). Morin remarked that the stars of 1960s European cinema, such as Delon, Bardot, or Cardinale, were able to move between popular entertainment genres and the contemporary director’s cinema that aestheticized the social life of the period (Morin 1972, 154). But from the 1970s onward, Delon’s box-office success at playing tough guys (either cops or hit men) was such that audiences preferred to lock him into the macho crime genre, thereby undermining his more ambivalent dramatic performances in films such as Mr. Klein, La prima notte di quiete/Indian Summer (Valerio Zurlini, 1972) or Notre histoire/Our Story (Bertrand Blier, 1984), performances for which Delon was cast against type, subverting his popular, assertively masculine persona. The commercial failure of Zurlini’s fatalistic professor or Blier’s alcoholic mechanic was due, in Delon’s account, to the audience’s reluctance to accept him as an unhappy loser. “For my audience,” he laments, “Delon is automatically a hero of good or evil. He must

Introduction: Alain Delon, Then and Now

7

Figure 2 Delon as Tancredi in Il gattopardo/The Leopard (1963)

be a winner, not a loser … . This is the image of Delon that is expected” (Dureau 2012, 77). For Delon as producer, this meant appearing in gunslinger movies to be able to finance the more culturally prestigious films that showed off his considerable acting talents, such as Mr. Klein, for which he lost his investment (Servat 2001, 64). The critical reception of Delon’s career supports the actor’s own perception of an entrenched division between the films he made with a number of “master” directors (his term for the formative collaborations with Clément, Visconti, Melville, and Losey) and a prolific career in genre cinema that maintained his popularity. An account of Delon’s stardom, published in Positif in 2012 (Cieutat 2012), highlighted not only his physical and technical versatility

8

Alain Delon

as a performer—the good looks, elegant movements, and precise gestures— but also the surprisingly broad range of roles across a career spanning some 50 years: from the ambitious heroes and fragile victims to the more overlooked comic roles, such as his early light-footed performance in a comedy about Italian anarchism, Quelle joie de vivre/The Joy Of Living (René Clément, 1961). The cinéphile reception of Delon’s career dates back to an initial homage to the actor’s work hosted by the Paris cinémathèque in 1964, for which Henri Langlois raised the actor to the status of “greatness.” A later retrospective held in 1996 was an opportunity for the intellectual film journal, Cahiers du cinéma, to assess Delon’s singular place within the landscape of French and international cinema; the actor was perceived as the only French male film icon of the postwar period, known locally as the “French James Dean.” In terms of roles in classic films, Delon was on par with his near contemporary Marlon Brando, whose instinctive technique and gestural precision were similarly influenced by an earlier actor, John Garfield, the modern precursor of method acting, also known for playing brooding rebels (Jousse and Toubiana 1996, 27). Delon’s naturally graceful way of gliding through the frame broke with the more overtly theatrical style of 1950s French screen acting; in his debut role in Quand la femme s’en mêle in 1957, his slim body and edgy movements marked him out from the established leading men of the 1950s such as Jean Marais or Henri Vidal. The incongruous sequence in Plein soleil in which Delon is filmed strolling nonchalantly around Naples fish market documented the actor’s idiosyncratic presence on the French cinema screen of the period, much like his female contemporary, Bardot, whose physicality and fashion-sense also marked her out for audiences as resolutely modern (Figure 3). An out of character sequence spliced into the narrative for no reason other than visual pleasure, the scene illustrates how the actor’s early films enshrined him as a rising star simply by documenting his spontaneous presence in front of the camera. It was this subtle illusion of naturalness—a performance that seemed to position the actor at the creative center of the film—that marked Delon out (in the eyes of Langlois) as an enduring star.2 However, Delon has not always been held in such high esteem. In 1982, critic Serge Daney attacked the actor’s formulaic star-vehicle, the crime thriller Le Choc/The Shock (Robin Davis, 1982) as symptomatic of the implosion of the French star system, one in which Delon’s apparent narcissism overwhelmed the entire production. Rather than relying on the classic close-up to illuminate his stardom, Delon no longer bothered acting at all (according to Daney) but

Introduction: Alain Delon, Then and Now

9

Figure 3 Delon out of character at Naples fish market (Plein soleil, 1960).

rather reproduced his familiar screen repertoire in a film structured as a series of adverts to showcase his versatility (Daney 1998, 159). The idea that Delon had become a caricature of himself (widely known for immodestly talking about himself in the third person) is one that gained currency as the star’s glory waned through the 1980s and early 1990s, despite notable roles in auteur films such as Nouvelle Vague that self-reflexively deconstructed his persona as a quotable text (Morrey 2005, 174). The middle and later stages of Delon’s career were indeed punctuated by a series of complex dramatic roles (particularly the overlooked performances in La prima notte di quiete and Mr. Klein in the 1970s) that actively sought to dismantle the cliché of fatal beauty and spectacular narcissism so redolent of his earlier work and the macho archetype of his crime films. Delon’s talent as a dramatic actor was only belatedly recognized through the César award for best actor in 1985 for his character study of the wayward mechanic Robert in Blier’s absurdist comedy-drama Notre histoire, which exposed him to a younger generation of actors such as Nathalie Baye, Gérard Darmon, JeanPierre Daroussin, and Vincent Lindon. Yet, while the international distribution of Delon’s later films focused almost entirely on his work for acclaimed directors, his enduring image in France has been sustained by regular appearances in more popular genres, particularly roles in comedies such as Le Retour de Casanova/The Return of Casanova (Edouard Niermans, 1992) and Une chance sur deux (Patrice

10

Alain Delon

Leconte, 1998), sharing the screen once more with Jean-Paul Belmondo, and in a self-mocking cameo playing Julius Caesar in the third installment of the live-action Asterix franchise, Astérix aux jeux olympiques/Asterix at the Olympic Games (Frédéric Forestier and Thomas Langmann, 2008). Since the start of the century, Delon’s public profile has extended beyond cinema to include roles on the Paris stage, co-starring with his daughter in Une journée ordinaire/An Ordinary Day in 2011 and in TV mini-series Fabio Montale (2002) and Frank Riva (2003–2004), which both echoed and perpetuated his established cinematic image as the solitary cop or tough guy. The fictionalization of his screen persona in Benjamin Berton’s humorous novel Alain Delon est une star au Japon/Alain Delon is a Star in Japan in 2009, in which two crazed fans kidnap their idol, and his surprising cameo appearing as himself in a Russian seasonal rom-com, новым годом, мамы!/ Happy New Year, Moms! (Sarik Andreasyan, Artyom Aksyonenko and Anton Bormatov, 2012) both acknowledge the star’s continued appeal beyond Western Europe. One of the key concerns of this book, beyond our historical examination of the star’s evolving place within French cinema, is to illustrate the inherent limitations of a singular approach to film stardom by considering Delon’s work beyond France as well as domestically. The collection begins with two chapters that engage theoretically with Delon’s career in terms of image, agency, and performance. Darren Waldron tackles the question of male objectification and narcissism attendant to the representation of beautiful male film stars like Delon, using an existentialist understanding of “agency” to inquire how some of the actor’s most emblematic roles might be read as attempts to negotiate his own problematic positioning as an object of desire. Laurent Jullier and Jean-Marc Leveratto also reference Delon’s mythical status as pin-up but situate his career in relation to the sociological concept of emploi, or the tension between the embodiment and identity of the individual performer, the role he is playing and the audience’s own framing of his persona. The following four chapters proceed roughly in chronological order, offering textual and historical investigations of different locations and periods of Delon’s career: Gwénaëlle Legras examines Delon’s early media profile, showing how he was positioned between the generic traditions of French cinema of the late 1950s and the modernity that he was seen to represent both physically and stylistically. Catherine O’Rawe takes Visconti’s Rocco as an extended case study of the young Delon within the cross-cultural context of Franco-Italian coproductions of the period, with their practice of dubbing the original voice-tracks into Italian.

Introduction: Alain Delon, Then and Now

11

O’Rawe unpacks the cultural and linguistic factors involved in dubbing to assess how the practice supported or undermined the director’s famous objectification of Delon. Leila Wimmer focuses on Delon’s crime persona in the popular films he made partnering the most emblematic French male screen icon of the prewar era, Jean Gabin, highlighting the question of generational transmission through two conflicting representations of masculinity of the 1960s. Mark Gallagher examines Delon’s career outside of French national contexts. Combining industrial analysis with performance, Gallagher addresses the circulation of Delon’s persona beyond the context of French cinema of the 1960s and 1970s, using his English-language roles as evidence of a truly cosmopolitan (as opposed to a simply national) screen icon. The next three chapters shed light on Delon’s activities beyond acting, examining his roles as director, producer, screenwriter, singer, and fashion icon. Isabelle Vanderschelden argues that the launch of Delon’s production company was symptomatic of the star’s desire to take full control of his career by changing his image, to transcend the urban clichés of the popular crime flicks he was most famous for, and to test the ambivalence of his star persona, constantly attempting to position himself across the critical divide between auteur and popular cinemas. Barbara Lebrun analyses how Delon’s sung performances (most famously accompanying the pop icon Dalida) have sought to modify his star image particularly in relation to the question of gender, itself a central preoccupation of fashion culture, the focus of Nick Rees-Roberts’ chapter on the heritage of the star as a global style icon. Rees-Roberts brings Delon into the twenty-first century by addressing the House of Dior’s strategic manipulation of his image to project a timeless brand of French elegance. Finally, Sue Harris tackles the question of aging by addressing Delon’s late career, situating the now veteran 80-year-old actor within recent French film and television, in which he has largely reiterated rather than revitalized his image. As a collection of interventions on Alain Delon, this volume seeks to consider his image and persona as it relates to the cinema as well as to other areas of cultural production and consumption, including fashion and music. It attempts to paint as holistic a picture as possible of the forms and meanings of Delon’s image, in which his acting talents are recognized along with his acknowledged self-appreciation and promotion. Moreover, its focus on an actor understood as emblematic of a certain idea of modernity, even if this was within a period now confined to history, allows the volume to enter into a dialogue with contemporary issues—to bring together the “then and now,” both of the configurations and

12

Alain Delon

significations of Delon’s star persona and of the time periods during which he has enjoyed celebrity. Whether the object of reverence or ridicule, of desire or disdain, Delon remains a unique figure who continues to court controversy and fascination more than five decades after he first achieved international fame. That he has recurrently been recalled and revived by subsequent generations of pop stars (from Morrissey to Madonna) and consumer brands (from Dior to Krys) confirms the indelible mark that he has left on contemporary popular and visual culture. It is perhaps because of this that Delon can be placed alongside some of the groundbreaking international stars with whom he was compared when he first started acting in the late 1950s. It is Delon’s iconicity and longevity that render a scholarly investigation into his career, persona, and image both timely and necessary.

Notes 1 See David Forgacs’ audio commentary to the BFI DVD re-issue of the film (2004). 2 Henri Langlois quoted in Alain Delon, Editions de la Cinémathèque française: Paris, 1996, 9.

1

On the Limits of Narcissism: Alain Delon, Masculinity, and the Delusion of Agency Darren Waldron

In classical mainstream cinema, the male has been objectified despite himself, as if unaware that he is offered for the erotic pleasures of the audience. However, in the case of Alain Delon, as many commentators have observed, his early image was predicated upon the “narcissistic display of his face and body” (Vincendeau 2000, 174) (Figure 1.1). In the early films in which he starred, such as Plein soleil/Purple Noon (René Clément, 1960) and La Piscine/The Swimming Pool (Jacques Deray, 1969), the narrative flow is briefly suspended to afford a contemplation of his striking, sensual beauty. The actor embraced this pervasive camera, famously boasting that he was an homme idéal (ideal/perfect man) (in Jousse and Toubiana, 1996, 31), although Vincendeau characterizes him as an homme fatal that functions as “both object of the gaze and narrative agent” (2000, 177). And yet, the extent to which Delon can be described as an agent in the broader sense can be questioned. His characters are frequently marked by their inability to gain mastery over their existence, resulting in or caused by their alienation from the world, a lack of power that can be broadened out as a commentary on his star image as a whole. This discussion explores the narcissistic mode of representing men and of male stardom with specific reference to Delon’s emblematic gigolo roles as Tom Ripley in Plein soleil and Jean-Paul in La Piscine. It attempts a reading of Delon’s early image through the prism of Simone de Beauvoir’s discussion of narcissism in the “justifications” section of the second volume of Le Deuxième Sexe/The Second Sex (1949). Such an approach carries obvious tensions, given Beauvoir’s focus on the “condition” of woman. Yet, the homme-objet (male object) raises issues with regard to subjectivity not dissimilar from its female counterpart. This chapter probes how, in colluding in his construction as a male object and ideal,

14

Alain Delon

Figure 1.1 Delon in his prime as Tom Ripley in Plein soleil (1960)

Delon grants power in affirming his subjectivity to the objectifying other, that is filmmakers and the audience.

Narcissism and the delusion of agency The term narcissism, as is popularly known, originates in Greek and Roman mythology. Variations of the original myth exist, with the most popular casting it as a tragic tale of non-consummated self-love.1 Ovid’s version from his third book of Metamorphoses (8AD) frames the myth as a story of revenge between Narcissus and Echo, a mountain nymph doomed to repeating the words of others. After Narcissus spurns Echo, she spends the rest of her existence heartbroken, which Nemesis avenges by having Narcissus fall in love with his reflection in a pool of crystal clear water and then die through grief at not being able to consummate his erotic urges toward himself. Other interpretations, such as that recounted in Robert Graves’s “complete and definitive” edition of the Greek myths, have Narcissus commit suicide; after sending a sword to ward off Ameinius, one of his (male) suitors, Artemis punishes Narcissus for his vanity by making him fall in love with his image and stab himself. As Graves asks rhetorically, “how could he endure both to possess and yet not to possess?” ([2011] 1955, 287–88). In more modern times, narcissism has been attached to certain “personality” or “character” disorders, in which outer love of the self is often seen as a marker of inner low self-esteem. According to Freud, narcissism constitutes a “normal”

On the Limits of Narcissism

15

phase of child development and is concerned with self-preservation. Primary narcissism refers to the infant’s love of itself (ego libido), in which, the child, in effect, represents for himself his own ideal (ideal ego). When the adult takes another person as the object of their libidinal energies, primary narcissism is diluted, but secondary forms of narcissism can still surface, partly as a consequence of repression (1998, 151). As the growing child becomes aware of the criticisms of others and those that come from within “him,” “he” seeks to “recover” the “narcissistic perfection of his childhood” in the “new form of an ego ideal” (1998, 151). Narcissism constitutes an erotic investment in the self, unlike sublimation, which “consists in the instinct’s directing itself toward an aim other than, and remote from, that of sexual satisfaction” (1998, 152). Freud’s account of narcissism (and those of the many scholars that build on it) can offer fruitful resources for interpreting Delon’s childhood and youth as they are reported in the press and biographies. In his self-proclaimed “unauthorized” study of the star’s life, Bernard Violet reveals how the infant Delon was first indulged by his mother and then, seemingly, rejected (2000, 13; 17). Following her second marriage, Édith Boulogne (Mounette) gave birth to a daughter, baptized with the first names of both parents to symbolize the reciprocity of their relationship (Paule-Édith). Delon, having been born to Mounette’s previous husband (Fabien Delon), still bore the name of his father. Delon misbehaved and was dispatched to foster parents and sent to boarding school, which he is reported as having experienced as a rejection (Violet 2000, 19). Carrying a sense of excess to the requirements of his parents in their new relationships, Delon continued to rebel and was apparently expelled from numerous religious educational institutions (Violet 2000, 19). His unruly behavior could thus be interpreted as the product of someone forced to elevate themselves as compensation for their sensed alienation from the external world. It was allegedly during this period that Delon became aware of his potential to disarm through his looks (Violet 2000, 20). Projections of omnipotence derived from a narcissistic valorization of his erotic appeal would feature among the most prominent markers of Delon’s star persona. Yet, such assertions of apparent power can constitute affectation and this is made clear in the frequent obvious signs of vulnerability and selfdoubt that traverse Delon’s career and image. Striking resonances emerge between Delon’s reported personal life and public image, and what Wilhelm Reich labeled as the “phallic-narcissistic character” (1933, 217–25). For Reich, the phallic narcissist is often raised by a strict mother and “his” desire for vengeance is then played out in “his” sadistic and selfish

16

Alain Delon

attitudes in “his” relationships with women. “He” tends to be “self-assured, sometimes arrogant, elastic, energetic, often impressive,” while “his” physique is “predominantly an athletic type” but often accompanied by “feminine, girlish features” (1933, 217). “His” narcissistic sensitivity leads to “sudden vacillations from moods of manly self-confidence to moods of deep depression” (1933, 221). Much of “his” behavior is concerned with defending against “anal and passive tendencies” and can thus be triggered by repressed homosexual urges (1933, 221). Some of this behavior is attributed to Delon, as evidenced in the recollections of former peer and friend Jean-Claude Brialy, who remembers his violent and/ or indifferent behavior toward his female partners, including Brigitte Auber and Romy Schneider, as well as his domineering attitude toward Brialy himself (2000, 131–32; 143–46). The idea that mastery of the self can be achieved through narcissistic forms of self-affirmation of the kind that Delon is said to have engaged in is delusory—or rather self-delusory. It is here that we might fruitfully turn away from psychoanalysis and to existentialism in order to elucidate better how this delusion/self-delusion plays out in material terms. Narcissism can be understood as a form of bad faith in the existentialist sense in that it allows us to avert our attentions away from the not-yet-known of our future lives and preoccupy ourselves within the already-known of our present (and past). As such, it is a means of evading the freedom to self-determine that existentialists believe characterizes human existence. As Jean-Paul Sartre famously argues in L’Être et le néant (1943), as human beings endowed with consciousness, we can transcend our current situations and act for ourselves. Although we may feel inhibited by our past experiences and current circumstances, to use these as justifications for not choosing our freedom is to engage in bad faith. While perhaps not narcissistic in its purest sense, the behavior of the café waiter famously described by Sartre illustrates this cogently. For Sartre, as the waiter invests meticulous attention in executing his duties perfectly, he plays at being a waiter. Although he might believe that he affirms mastery through his behavior, ultimately, his actions serve to limit his existence to a being-in-itself as a waiter (1943, 94). Owing some philosophical debt to Sartrean existentialism, as well as to phenomenology and Marxism, Simone de Beauvoir pursues these ideas further in her examination of narcissism and the “condition” of “woman.” Patriarchy, according to Beauvoir, works to bind woman to certain roles and situations, mainly marriage and motherhood, thereby imprisoning her within a realm of

On the Limits of Narcissism

17

immanence and denying her transcendence. Somewhat controversially, Beauvoir reveals how women, as well as men, perpetuate this unequal distribution of power through an internalization of patriarchy’s values via gendered forms of bad faith, of which narcissism is a prime example (1949, 519–84; see also Boulé and Tidd 2012, 4–5). As Linnel Secomb notes, transcendence assumes a specific meaning for Beauvoir, it “involves reaching beyond the constraints of immanence, beyond entrapment within biology, social convention and repetitive domesticity, embracing freedom through active involvement in the public world” (2012, 87). The female narcissist embarks upon a strategy of selfdeception wherein she overinvests in her beauty and attractiveness, and seeks to convince herself that she achieves agency and power by virtue of her physical appeal. Such an endeavor is self-delusory because it involves attempting to affirm a free, transcendent subjectivity through the apprehension of the self as both subject and object, which for Beauvoir is impossible: “it is not possible to be for self positively Other and grasp oneself as object in the light of consciousness” ([1949, 520] 2009, 684). That Beauvoir was writing about the situation of woman in no way makes her points meaningless when discussing the situation of certain men. As a film star, Delon derives acclaim from putting himself, intentionally, in the public domain.2 Moreover, given that the substance of that stardom derives, in his early performances in particular, from his status as erotic male on display, he can be described, like the female narcissist, as a prisoner of that existence. Although not in the section that specifically addresses narcissism, Beauvoir uses the example of the female Hollywood star to illustrate the limitations of celebrity, reminding us that, while “she” thinks “she” enjoys some form of autonomy, “she” is nonetheless always someone else’s object (1949, 396; see also Boulé and Tidd 2012, 5–6). According to Beauvoir, that someone else is the producer, but, as we know, the star is also beholden to the audience’s wishes, expectations, desires, and fantasies (Dyer 1998 [1979], 19–22). Many stars are trapped within an externally defined identity, incarcerated within a realm of contingency determined by others. Like Sartre’s waiter and Beauvoir’s female narcissist, though, they are complicit in this entrapment; it is not that they are unable to escape their situation, but through their actions of seeking to reaffirm and revive their appeal, they perpetuate their dependence, arguably despite knowing the stifling impact of such a status for selfdetermination. The implications of this for Delon’s image and its manifestations within his performances in Plein soleil and La Piscine will be examined in detail in the next section.

18

Alain Delon

Plus ça change …: Delon’s gigolo persona and its implications As commentators have noted, Delon’s early persona was closely associated with the figure of the international playboy and/or gigolo (Vincendeau 2000, 175; Bruzzi and Church Gibson 2008, 165), and this is perceived as a convergence of his roles with his real life as reported in the press. Though semantically distinct—the playboy might be perceived as more independent than the gigolo, who lives from his erotic relationships with well-heeled and usually older women—both sustain their existence, attain a sense of self and attempt to affirm agency through an investment in their physical allure. Nowhere is this embodiment of the playboy/ gigolo figure more obvious than in Delon’s two iconic roles as Tom Ripley and Jean-Paul. In fact, La Piscine bears a complementary relation to Plein soleil; JeanClaude Carrière recalls that Plein soleil was a constant presence in the minds of the film crew during the shooting of La Piscine (DVD extras) and such congruence is evident in the casting of Delon and Ronet as rivals, the former as killer, the latter as his victim, murder plot narrative and southern European settings. The adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley (Patricia Highsmith, 1955), Plein soleil centers on Tom Ripley (Delon), a man of limited finances, who has been dispatched to Italy to bring Philippe Greenleaf (Ronet) back to America by Greenleaf ’s father, for $5,000. Tom envies Philippe’s playboy lifestyle, while Philippe exploits Tom’s dependency; during a yacht trip, he abandons Tom in a dinghy in the blazing sun and casts his girlfriend Marge’s (Marie Laforêt) manuscript on Italian Renaissance painter Fra Angelico into the sea. Tom attempts to avenge and affirm mastery over his friend by stabbing Philippe, dumping his body in the sea, and assuming his identity. However, his endeavors are frustrated by the suspicions of Philippe’s friend, Freddie Miles (Billy Kearns), whom he also murders, and chief inspector Riccordi (Erno Crisa). Realizing that his plan has failed, Tom fakes Philippe’s suicide by forging a letter as Philippe in which he bequeaths his estate to Marge. Tom seduces Marge, but even the compromise of attaining wealth through romance is, it seems, denied him. As he smugly sips his drink while basking semi-naked in the sun (Figure 1.2), the film crosscuts to shots of the yacht being winched from the sea, with Philippe’s corpse seemingly attached to the propeller and, later, of Riccordi waiting to seize and arrest him. Tom’s envy of Philippe is mirrored and extended in Jean-Paul’s jealousy over Harry (Ronet) in La Piscine. Jean-Paul is a writer in a relationship with his wealthy girlfriend Marianne (Romy Schneider), with whom he is staying

On the Limits of Narcissism

19

Figure 1.2 Tom Ripley basking in the sun at the end of Plein soleil (1960)

at her summerhouse in the south of France.3 Harry, Marianne’s playboy ex-lover, visits for a few days, accompanied by his daughter Penelope (Jane Birkin). After seducing Penelope, Jean-Paul drowns a drunken Harry in the pool, which he then portrays as an accident. When inspector Lévêque (Paul Crauchet) suspects that he is Harry’s killer, Jean-Paul confesses to Marianne, who later denies his involvement to Lévêque. Beyond actor, plot and location, the sensual display of Delon’s face and body at a time when men were not commonly represented as erotic objects closely binds both films. As Bruzzi and Church-Gibson remark “Delon was one of the first male heroes to be stripped and fetishized on screen” (2008, 165), an image that the actor had partially honed for French audiences in his first film appearances. Where the crystal clear waters of a Greek spring reflected Narcissus’s beauty back to him, the deep azure of the Mediterranean Sea that laps against the shores of southern Italy in Plein soleil and the shimmering, translucent waters of a swimming pool in the south of France in La Piscine frame and illuminate Delon’s delicate facial features and toned and tanned body.4 The first time the audience sees Delon’s naked torso in Plein soleil comes during the yacht excursion with Philippe and Marge. When Philippe asks Tom to steer the vessel so that he and Marge can make out in the galley, Tom swiftly rips off his shirt to reveal his chiseled chest and stomach. The camera films him in medium long shot, the impression of voyeurism enhanced by its position behind the ladder leading down from the deck. For an instant, Tom stands

20

Alain Delon

motionless, as if wittingly exhibiting his body for the enjoyment of others. Marge and Philippe are, very momentarily, silent, their apparent surprise inscribing within the narrative the possible astonishment of the spectator as s/he witnesses this unexplained exhibition of naked male corporeality. Tom’s strip to his waist foreshadows what is arguably the film’s most famous sequence, in which Delon is sat, upper body exposed, behind the yacht’s large wheel, a version of which was used for the film’s poster. The intertextual linking of La Piscine to Plein soleil through the display of Delon’s physique is instantly evident in the later film’s opening sequence. A tracking shot slowly glides over the water’s surface to Delon in deep repose, basking in the bright sun, dressed only in his tight swimming trunks, before Marianne awakens him from his semi-slumber. Recollections of Tom/Delon sunbathing in the final shots of Plein soleil are immediately triggered, but the sexual connotations of the earlier images are intensified as Delon, his head resting on the slabs of the poolside patio, opens his mouth and empties a glass of juice into it (Figure 1.3). In such shots and scenes, Delon might be said to embody, seemingly without scruple, the epitome of the homme-objet, as defined by Laurent Jullier and Jean-Marc Leveratto: while the male subject “exists” … in other words, he perpetually projects himself outside of the materiality of his organs by torturing himself in his quest to know what great life decisions he should make based on their consequences, the male object has stopped paying a philosophical price. He delivers the merchandise, he rests in peace: his body speaks for him (2009, 6—my translation).

Figure 1.3 Delon’s body on display in the opening of La Piscine (1969)

On the Limits of Narcissism

21

Such rendering of the male body as a source of erotic stimulation can be seen as progressive in that it opens up potential sexual gratification from visual culture to audiences irrespective of gender and sexual orientation. Moreover, as Jullier and Leveratto note, it divests the male of the pressures, incumbent with dominant masculinities, to affirm an active and authoritative subjectivity by allowing him to take pleasure in himself as an object of desire. This voluntary objectification departs from the “privileged” position that, according to Beauvoir, men have enjoyed as transcendent subjects within patriarchy: “man who feels and wants himself to be activity and subjectivity does not recognize himself in his immobile image; it does not appeal to him since the man’s body does not appear to him as an object of desire” ([1949, 521] 2009, 685). In the case of the homme-objet, the reflected image appears indivisible from its material source and agency (if we recall Beauvoir) is displaced. For Christopher E. Forth and Bertrand Taithe, Beauvoir’s conceptualization of “man” in Le Deuxième sexe is monolithic (2007, 3). Yet, it is nonetheless predicated upon common qualities that have been advanced, across the centuries, as ideals of masculinity, grounded in notions of activity and power, courage and valor, will, and determination.5 It is in accordance with such models that men have been compelled to construct their identities and, quite simply, exist in the world. The importation of globalized consumerism and perceptions of broadening wealth in France from the early 1950s spawned new models of male identity that inspired young, middle-class men to dream about the rapid acquisition of wealth and the hedonistic pursuit of instant pleasure. Individualism was valued, and, as commentators have noted, this broader backdrop provided the perfect environment within which an actor such as Delon achieved international stardom (Vincendeau 2000, 184; O’Shaughnessy 2007, 195). Delon constitutes one of the most apposite embodiments of the “new” modes of masculinity, which is emphasized in films such as Plein soleil and La Piscine by explicitly juxtaposing him with more traditional representations of men, principally associated with the preceding generations. The final shots of Plein soleil make this generational dissonance obvious through the crosscutting between a semi-naked Tom passively sipping his drink and sunbathing, his skimpy swim-shorts emphasizing his body on display, and the other male characters (Mr. Lee (actor uncredited)), the purchaser of the yacht, Mr. Greenleaf (actor uncredited), Riccordi, and his deputy (Leonello Zanchi) cutting a deal and leading a police investigation, covered, from head-to-toe, in their suits. Masculinity in the egocentric narcissistic mode, represented here in transient

22

Alain Delon

pleasures and an arrogant disregard for received authority and morality, cannot be countenanced by traditional patriarchy for it risks compromising the male privilege of which Beauvoir wrote. Tom and Jean-Paul must be punished, not only for their crimes, rebellion and arrogance, but also because they reflect back to Riccordi and Lévêque their own complicity in a system that, ultimately, delineates their existence and, thus, subordinates them. They have not only failed to seize the freedom that, according to existentialists, inheres in human existence, but they also defend the very system that forecloses that freedom. Yet, while both films end with the assumed punishment or containment of the errant and conceited young male, they also tantalizingly deny patriarchy its traditional role as judge and jailer. Plein soleil stops short of actually depicting Tom’s arrest (and he evades lasting punishment in Highsmith’s literary series) while Marianne prevents Lévêque from acting on his suspicions by denying Jean-Paul’s involvement in Harry’s murder. Interestingly, then, particularly given the dubious portrayals of women in both films, actual power is transferred from aged patriarchs and male upstarts to upwardly mobile young women. Although an unwitting and possibly unwilling participant in this transformation, Marge shifts from melancholy girlfriend to proprietor and deal broker, highlighted as she enters the traditionally masculine space of negotiation to sell her yacht. Marianne already enjoys material power as the owner of the summerhouse in which the narrative of La Piscine unfolds and is endowed with actual omnipotence as the custodian of Jean-Paul’s future/fate. The problem, though, is that such a redistribution of power does not transcend the conventional active/passive structure that governs social and gender stratification. Consequently, although the casting of the male as an object of desire may well be democratic, rather than allowing men—and indeed women—greater freedom and autonomy, the broadening out of the bodies that can be eroticized transfers, onto men, the stasis of contingency and immanence that have, according to Beauvoir, constrained women. Whereas for Beauvoir it was patriarchy that denied woman agency, from the 1950s in particular, globalized forms of capitalism stifle self-determination for both men and women. In being an homme-objet, men, like women, are compelled to work toward the commodification of themselves as an end in itself. Consumerism encourages the complacent and misguided belief that self-affirmation can be gained through vanity and personal wealth, but narcissism serves as a decoy to an autonomous subjectivity and a fulfilled existence. It is precisely this dilemma that Delon’s image as object and gigolo represents; as mentioned, any sense of

On the Limits of Narcissism

23

mastery over his existence is a delusion since he is reliant upon his erotic appeal in order to sustain his status. The constraints of narcissism and its threats to an autonomous subjectivity are implicitly conveyed in the much commented upon mirror scene in Plein soleil and then developed in the narrative as a whole. While Philippe and Marge embrace in the sitting room, Tom is dispatched to the bedroom where he dons Philippe’s stripy blazer, parts his hair and stares at himself in the mirror uttering in affected tones, as if Philippe, “ma Marge, mamie, m’amour” and then kisses his own reflection. By striving to “be” Philippe, Tom could be said to restrict his future existence to an already known entity—a (convincing) fake (even if, as Rees-Roberts notes in this volume, his performance as his rival constitutes an improvement on the original)—rather than seizing his potential for achieving autonomous selfhood. The mirror scene also has obvious significations for how Delon apprehends himself and his own image. Although he was not yet a star when he made Plein soleil, as we watch Tom as he revels in his reflection, we cannot help but think about Delon’s own autoerotic gratification in observing himself. As he moves in to embrace his reflection, his eyes slowly close as if in amorous thrall at the possibility of kissing, and being kissed by, himself. For Joël Magny, his contemplation of his reflection constitutes a form of schizophrenia, in which the inter-subjective dynamic of the gaze is averted, and this provides the basis for how Delon appreciates himself throughout his career: “from then on, Delon watches himself perform ‘Delon,’ through a series of interposed directors” (1996, 21).6 Remarks attributed to the actor substantiate such an interpretation; for instance, in 1999, he is quoted as saying “I surprise myself and am fascinated by myself ” (Violet 2000, 371). Yet, since it is impossible to hold the self up as object and, through that self-objectification, enjoy autonomy, Delon, rather like Sartre’s waiter, achieves a “being-in-itself ” as “Delon.” The doubling of the mirror scene later in the narrative, when Tom interrupts Marge as she plays the guitar and kisses her hand, illustrates the implications of this narcissism for the star’s image. Via a shot reverse-shot sequence of close-ups of both Marge and Tom’s eyes, the response his amorous act elicits in Marge preoccupies Tom and overrides the erotic pleasure he may gain from the visceral sensation of his lips coming into contact with her skin. Here, then, Marge serves as the affirmation of the sensual impact of Tom’s perceived erotic allure and, for the viewer, as a gauge of the danger he ultimately embodies. The issues with regards to Delon’s image and status remain the same; just as Tom requires Marge’s desires for him so that he can access her wealth, Delon needs the audience to

24

Alain Delon

invest erotically in him to secure his promotion from actor to star. Moreover, while he may appreciate his performances and elevate himself as unique, he sets the benchmark against which “Delon” will subsequently be evaluated, thereby cultivating a subjectivity that can only be confirmed by others and whose value comes from a retrospective comparison between what he is now and once was. Plein soleil and indeed La Piscine inscribe this sense of doomed and immanent selfhood within the sequencing of their scenes. Images of Delon as erotic spectacle precede, coincide with and follow moments where the precariousness of his situation is brought to the fore. In Plein soleil, shots of him steering the yacht with his chest exposed occur moments before Philippe casts him off in the dinghy. Later, when Riccordi visits Tom in Rome to question his statement about Philippe, the ubiquitous image of Delon’s torso framed by an open shirt reappears, here in the form of a pajama top. Tom’s momentary vulnerability is conveyed by the three-shot composition in which a suspicious Riccordi is shown leaning against the wardrobe on the right with Tom’s reflection coming into view on the left as the door opens to reveal Philippe’s incriminating blazer in the center. Furthermore, if we are to believe what is suggested by the narrative, although the ending does not confirm whether Tom is actually arrested, his murderous plan appears to have been foiled, the very last images showing him nonchalantly walking toward his presumed condemnation, again his shirt-jacket open, its tails fluttering slightly in the warm breeze. La Piscine renders the precariousness of such an identity even more explicit in that Jean-Paul’s whole being is confined, from the outset, to his role as the emotional, financial, and sexual dependent of his female lover. He is reliant upon his ability to seduce and satisfy Marianne, whose behavior reflects and reinforces his dependency. At times, Jean-Paul attempts to reaffirm a complacently macho identity, casually sitting back in a deckchair and feigning indifference in gruff tones when Marianne informs him of her ex-lover Harry’s impending visit, for instance. Yet, for all Jean-Paul’s attempts at appearing disinterested, it is he who is shown to seek out Marianne’s attentions and who strives to please her, scratching her back, kissing her arm, and caressing her legs. In an early scene, he orders Marianne not to undo her hair and then proceeds to untie it himself. He embraces her and then leaves her, torso naked, arms outstretched, against a trellis, before taking a branch from a shrub and, at first, tickling and then whipping her back with it. Sadomasochistic symbolism abounds, but rather than master to Marianne’s slave, it is Jean-Paul who is required to satisfy his female lover’s sexual needs by performing the acts she requires of him.

On the Limits of Narcissism

25

The implications of this for Jean-Paul and masculinity more broadly, as well as for Delon’s star image, are implied in a subsequent shot, which shows him, again in medium close-up, lying, again torso naked, on the bed, his preoccupied gaze directed off screen. His apparent gloomy look can be interpreted as the expression of his existential ennui, his frustration at not being able to break free from his present contingency. As in the mirror scene in Plein soleil, this moment has resonances for Delon’s own self-appreciation. If, as Austin states, he is always “self-regarding” (2003, 62; see endnote 6), his distracted, troubled look implies Delon’s awareness of his paralysis and precariousness. Again, he is Delon in the immanent mode, pure object, locked in a delimited space, existing for others, and not able to exist for himself. As the ineluctable knowingness of his look implies, he is acting in bad faith. The fictional villa might have all the trappings of luxury, as did, we assume, Delon’s life at the time, but it remains, ostensibly, a prison, with Marianne as symbolic jailer serving as an allegory for those who, ultimately, control his celebrity and status (producers, filmmakers, audiences). That Delon implied in interviews that he would not continue in the public eye later in life (Servat 2001, 57) illustrates the extent to which he appeared aware of his dilemma. While it may be true that he displayed considerable acting talents, witnessed in his appearances in Italian movies Rocco e i suo fratelli/Rocco and His Brothers (Luchino Visconti, 1960), L’eclisse/The Eclipse (Michaelangelo Antonioni, 1962), and Il gattopardo/The Leopard (Luchino Visconti, 1963), and took on bigger roles later in his career, as in Mr. Klein (Joseph Losey, 1976), forging a public persona that withstood objectification proved difficult. Moreover, when his ventures outside of acting enjoyed limited, if any, success, including organizing boxing championships, horse racing and collecting art, he courted celebrity once again. In fact, his screen reappearances, even when they appear to constitute self-derision, appear to be intended to remind the audience of his past importance and to rekindle what he once represented.

Escape without issue: Rebranding “Delon” and parodying the gigolo The reconfiguration of Delon’s persona from the mid-1960s to project a supplementary image7 as a cooler, tougher and more virile gangster/flic figure (Vincendeau 2000, 179) failed to enable him to transcend his earlier associations with vulnerability and dependency. While these characters, as famously

26

Alain Delon

illustrated in Le Samouraï/The Samurai (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1967) and Le Cercle rouge/The Red Circle (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1970), exude silent aloofness and thus represent one of the most ubiquitous constructions of hegemonic masculinity, they also embody weakness and an inability to act for themselves. As Forth and Taithe note, “masculinity is always subject to scrutiny, lapses, and failed performances, and is thus forever in a contested state” (2007, 4). Such a “failed performance” is central to these roles, seen most obviously in Delon’s incarnation of Jef Costello in Le Samouraï. Costello’s inability to express and exteriorize his emotions portrays him as prisoner, again locked in and paralyzed, unable to escape himself, hard, but empty. He survives, but does not exist, and resigns himself to his fate, literally leading himself to his place of execution in the final sequence in which he strives to carry out orders and shoot a nightclub pianist (Cathy Rosier) in front of her audience. When she asks why, he replies that he has been “paid to do it” thus figuring himself as a killing machine, a being unable to choose his own course of action and which, like the gigolo, exists initself and for-others. Interestingly, Delon emphatically identified with Costello, declaring “le Samouraï, c’est moi” (Austin 2003, 59), which could be said to serve as the ultimate bad faith statement since it implies the actor’s belief that he cannot be the architect of his own existence. Self-mockery, which would feature more heavily later in Delon’s career, has also had limited success in establishing a rupture between his earlier image and his later persona. An example is Delon’s performance of Émile, the remote lover who endures his partner C’s (Annie Cordy) lamentable monologue about her unrequited love for him in Jean Cocteau’s Le Bel Indifférent (1939), adapted for French television by Marion Saraut and broadcast on January 14, 1978. Émile never utters a word, which may mock through excess the silent gangster figure for which Delon was most famous in France, but the play really satirizes his gigolo persona. Cocteau’s stage notes implicitly refer to the immanence of the gigolo role, describing Émile as a “magnificent gigolo” who is about to lose his looks ([1939] 1989, 85). The play thus ironically gestures toward the very precariousness of Delon’s situation at precisely the point when he appears to deride his persona. Conscious and playful derision of the self can be seen as a form of selfpromotion, a means of trying to keep an image alive when its constitutive components appear to be on the wane. Delon projects himself as capable of accepting criticism and of holding himself lightly, but it is he and those with a vested interest in his image who set the parameters of that playful mockery.

On the Limits of Narcissism

27

His appearance in the advertising campaign for Krys spectacles in 2011 illustrates this. Here he is seen, at the age of 75, rehearsing for an imaginary audition. Struggling with his lines in the waiting room, uttering “he used to be intimidating,” pacing up and down and then stating “he used to be … he used to be, what was that again?” we see him recall “he used to be Alain Delon” before putting on his spectacles and adding “but that was before.” It could be argued that Delon’s performance manages to assert the distinction between the actor’s (past) image and the man behind that image, while parodying the parody of him on the television show Les Guignols de l’info (see Jullier and Leveratto in this volume). However, in exploiting those features that are perceived as the fundamental core of his image (his looks and third person mode of self-referencing/addressing), he can be said to perpetuate the links between present and past self rather than undermining them (see Harris in this volume). The advertising campaign, then, epitomizes his difficulties in affirming real mastery over his image and, by extension, symbolizes the star’s struggle to assert control over his situation.8

Concluding thoughts Offering men up for erotic contemplation constitutes a democratization of images and pleasures, as the shots of Delon in Plein soleil and La Piscine attest. And yet, although we might enjoy looking at his face and body in these films, the anxieties generated by such images are inescapable. When Delon displays himself for his diegetic and non-diegetic onlookers, it seems, crisis either lurks around the corner or stares him—us—in the face. Such crisis manifests itself in the obstacles represented by narcissism for achieving actual agency. It plays out in Delon through the concurrent vacillation between his gigolo and gangster/flic personas. Delon may have been compelled to perform different identities, either from within or without, but his failure to move on completely from his object status, despite various attempts, illustrates the contingency of an existence based upon a star subjectivity. Delon thus represents a recurring conundrum of celebrity culture; even when their popularity has waned, many of those in the public eye seem helpless in preventing themselves from continuing to court the attention and affirmation they think they once enjoyed. Narcissism and self-sublimation are clear drivers here; the lure of the unquestioned adulation of others, either because of their apparently striking physicality or assumed talent, or both, is what perpetuates such urges to return

28

Alain Delon

to the limelight, alongside financial incentives and external pressures from audiences and the industry. But, in succumbing, such individuals, and Delon is a prime example, foreclose creative becoming and allow their past selves to control their present and future subjectivities. According to Servat, Delon never hid his fascination for asocial characters, bandits and adventurers/defenders of lost causes (2001, 58). Yet, despite the promise he represented in the 1960s, since the passing of that moment, he has been compelled to uphold the status quo. Much like the inspectors Ricordi and Lévêque, who serve as the gatekeepers of the very patriarchal system that delimits their ability to claim a free subjectivity, Delon keeps alive the same structure that maintains him as its prisoner. To fail to defend that system could be seen as an avowal of the existential “bad faith” with which his persona and career appear to have been managed. This may be why he is drawn to speak out against evolutions in social morality, as evidenced in, for example, his castigation of France’s introduction of same-sex marriage laws. The paradox here derives not so much from the veracity or not of rumors about his sexuality, but from the fact that he ends up supporting a conservatively patriarchal set of values that, throughout his career, he often claimed to stand against.

Notes 1 2

3

4