A Human Garden: French Policy and the Transatlantic Legacies of Eugenic Experimentation 9781789205442

Well into the 1980s, Strasbourg, France, was the site of a curious and little-noted experiment: Ungemach, a garden city

215 87 7MB

English Pages 248 Year 2019

Contents

List of Illustrations

Foreword

List of Abbreviations

Introduction

Part I. The Intellectual and Political History of a Human Garden (1880s–1980s)

Part II. Eugenics, Biopolitics and Welfare in a Transatlantic Perspective (1914–1968)

Part III. Eugenics and Developmental Psychology: A Neglected Legacy

Conclusion

Epilogue. Forgetting Eugenics: Back to the Ungemach Gardens

Appendix. Works by Abel Ruffenach, Pseudonym of Alfred Dachert

Archival Sources

Bibliography

Index of Names

Index of Subjects and Institutions

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Paul-André Rosental

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

A Human Garden

BERGHAHN MONOGRAPHS IN FRENCH STUDIES Editor: Michael Scott Christofferson, Associate Professor and Chair of Department of History, Adelphi University France has played a central role in the emergence of the modern world. The Great French Revolution of 1789 contributed decisively to political modernity, and the Paris of Baudelaire did the same for culture. Because of its rich intellectual and cultural traditions, republican democracy, imperial past and post-colonial present, twentiethcentury experience of decline and renewal, and unique role in world affairs, France and its history remain important today. This series publishes monographs that offer significant methodological and empirical contributions to our understanding of the French experience and its broader role in the making of the modern world. Recent volumes: Volume 16

Volume 11

Paul-André Rosental

Jackie Clarke

A Human Garden: French Policy and the Transatlantic Legacies of Eugenic Experimentation

France in the Age of Organization: Factory, Home and Nation from the 1920s to Vichy

Volume 15

Volume 10

Sarah Gensburger

Beth S. Epstein

National Policy, Global Memory: The Commemoration of the ‘Righteous’ from Jerusalem to Paris, 1942–2007

Collective Terms: Race, Culture, and Community in a State-Planned City in France

Volume 14

Volume 9

Nicole C. Rudolph

Frédéric Bozo

At Home in Postwar France: Modern Mass Housing and the Right to Comfort Volume 13

General de Gaulle’s Cold War: Challenging American Hegemony, 1963–1968 Garret Joseph Martin Volume 12

Building a European Identity: France, The United States, and the Oil Shock 1973–1974

Mitterrand, the End of the Cold War and German Unification Volume 8

Shades of Indignation: Political Scandals in France, Past and Present Paul Jankowski Volume 7

France and the Construction of Europe 1944–2006: The Geopolitical Imperative Michael Sutton

Aurélie Élisa Gfeller

For a full volume listing, please see the series page on our website: http://berghahnbooks.com/series/monographs-in-french-studies

A Human Garden French Policy and the Transatlantic Legacies of Eugenic Experimentation

S Paul-André Rosental Translated from the French by Carolyn Avery

berghahn NEW YORK • OXFORD www.berghahnbooks.com

Published in 2020 by Berghahn Books www.berghahnbooks.com This is a translated, adapted and updated version of the original French book Destins de l’eugénisme published by Éditions du Seuil in Paris in 2016. A preliminary version of chapter 6 of this book was published in 2012 in the Journal of Modern European History under the title ‘Eugenics and Social Security in France before and after the Vichy Regime’ (10, 4, pp. 540–561). French-language edition © 2016 Éditions du Seuil Collection La Librairie du XXIe siècle, sous la direction de Maurice Olender English-language edition © 2020 Berghahn Books Translation by Carolyn Avery, with the support of INED (project 11-1-0) and Sciences Po’s Scientific Department, Center for European Studies and Center for History. Every reasonable effort has been made to supply complete and correct credits for images inside and on the cover of this book. If there are errors or omissions, please contact the publisher so that corrections can be addressed in any subsequent edition. All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A C.I.P. cataloging record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Control Number: 2019040082 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-1-78920-543-5 hardback ISBN 978-1-78920-544-2 ebook

I dedicate this book to my cousin Cécile Rosental, time-travel companion, and to the memory of my masters Jean Rivier, Marcel Baleste and Bernard Lepetit.

By means of psychological and economic technique it is becoming possible to create societies as artificial as the steam engine, and as different from anything that would grow up of its own accord without deliberate intention on the part of human agents. Such artificial societies will, of course, until social science is much more perfected than it is at present, have many unintended characteristics, even if their creators succeed in giving them all the characteristics that were intended …. But I do not think it is open to doubt that the artificial creation of societies will continue and increase so long as scientific technique persists. The pleasure in planned construction is one of the most powerful motives in men who combine intelligence with energy; whatever can be constructed according to a plan, such men will endeavour to construct. —Bertrand Russell, Scientific Outlook

Contents

S List of Illustrations

xi

Foreword Theodore M. Porter xiii List of Abbreviations

xvi

Introduction 1 Part I. The Intellectual and Political History of a Human Garden (1880s–1980s) 17 Chapter 1

The Acceptance of a Eugenic Experimentation Chapter 2

The Stone Poem of the Alsatian Ibsen

19 40

Chapter 3

Guinea Pigs or Citizens? From the Reign of the ‘Dictator’ to the Republican Public Policy (1923–1984)

63

Part II. Eugenics, Biopolitics and Welfare in a Transatlantic Perspective (1914–1968) 97 Chapter 4

From Micro- to Macro-History: Ungemach Gardens and the Survival of Eugenics in France after 1945

101

Chapter 5

Stamping out Racism and Reforming Eugenics: A Transatlantic History of Qualitative Demography

121

x Contents

Chapter 6

Qualitative Demography, Reform Eugenics and Social Policies in 1950s France

138

Part III. Eugenics and Developmental Psychology: A Neglected Legacy 157 Chapter 7

Eugenics as a Moral Theory (1): The Theory of Human Capital

159

Chapter 8

Eugenics as a Moral Theory (2): At the Sources of ‘Personal Development’ 174 Conclusion 189 Epilogue Forgetting Eugenics: Back to the Ungemach Gardens

195

Appendix Works by Abel Ruffenach, Pseudonym of Alfred Dachert

199

Archival Sources

201

Bibliography 203 Index of Names

225

Index of Subjects and Institutions

227

Illustrations

S Figures Figure 0.1 Performance of Ungemach Gardens (poster for the 1935 hygiene exhibition in Strasbourg).

3

Figure 1.1 The evaluation of the Schumacher couple.

23

Figure 1.2 Interior architecture of Ungemach houses.

25

Figure 2.1 The broadcasting of the Alsatian Ibsen’s theater play, n.d. [1950s].

45

Figure 2.2 Poster for the performance of Le Val l’Évêque in Paris in November 1921.

46

Figures 2.3 and 2.4 Portraits of Alfred Dachert as a businessman.

48

Figure 2.5 Suzanne Dachert, born Gounelle.

50

Figure 3.1 The preservation of the entry form in the 1980s.

64

Figures 3.2 and 3.3 Assessments of the municipal housing commission (12–13 November 1930): housekeeping grades and observations.

72–73

Figure 3.4 Intentions ‘cast in bronze’. Figure 4.1 ‘Papa Dachert’.

86 104

xii Illustrations

Tables Table 3.1 Declared causes of tenants’ departures from Ungemach Gardens (1934–1938). Table 3.2 The fate of tenants threatened with the termination of their leasing contract during annual visits from 1926 to 1930.

69 74–75

Graphs Graph 4.1 Relative use of the terms ‘eugenics’, ‘birth control’, ‘social insurance’, ‘social classes’ and ‘demography’, in United Kingdom English from 1900 to 1960.

111

Graph 4.2 Relative use of the words natalité, assurances sociales, sécurité sociale, classes sociales, eugénique and démographie in French from 1900 to 1960.

111

Foreword Theodore M. Porter

S ‘Eugenics’ is almost always traced back to the work of Darwin’s cousin Francis Galton, and then forward to programmes of forced sterilization and worse carried out by the Nazis. While episodes such as these are not easily forgotten (and must not be forgotten!), neither should we define away those less extreme or morally ambiguous practices that persisted up to our own time. The history of eugenics extends beyond what scholars have usually recognized, mainly because the forms it has assumed are so diverse. There are, at a minimum, troubling moral ambiguities bound up with any effort to improve the quality of populations by promoting the biological reproduction of particular human traits. Eugenics in its less brutal forms became a part of ordinary life, embraced by scientists, doctors, ministers, writers, politicians, administrators and reformers. Their ambitions and methods were widely depicted as fair and reasonable and as well suited to the needs even of those unfortunate individuals whose reproduction should be restricted for the sake of a healthy, prosperous population. Eugenics can be consigned to a benighted past only by averting our eyes from its most ordinary forms. Paul-André Rosental, known especially for his pioneering researches on the social history of demography, here addresses in a new way the anxieties and ambitions allied to twentieth-century reproductive politics. While the eugenic push for human biological improvement is central to this book, sterilization, whether voluntary or forced, scarcely comes into it. Its lead characters are not geneticists or biologists but planners, officials, teachers and psychologists. Eugenics in this study comes down to the identification of men and women, free of conspicuous defects, who were to be provided with a comfortable apartment in an attractive garden community on the condition that they bear and raise children. Such conditions, far from burdensome, were broadly consonant with reproductive

xiv Foreword

habits of the uncompelled. Unlike Galton, who insisted that the nation was endangered by a scarcity of outstanding statesmen, thinkers and scientists, here it was enough to bear a decent minimum of healthy, normal offspring. There was no insistence on brilliant achievements or of Stakhanovite reproductive efforts. Genetics was not the whole story. Heredity was to be allied to a healthy environment and sound upbringing. The biopolitical focus of this study, the ‘Ungemach Gardens’, was not a site of dramatic struggle, but a collection of quiet apartments. The residents were chosen based on a broadly eugenic point system, a system that combined biological assessments with behavioural incentives. It soon achieved the status of a model institution, and the reactions of its admirers, extending as far as California, lend a global aspect to this microhistorical investigation. But it was never a site of titanic ambition or Sturm und Drang. So quiet an institution, as Rosental points out, was of no special interest to the Nazis. In 1940, when Strasbourg was (again) folded into the German empire, they turned the buildings to other uses. Four years later, after Allied troops drove the German troops from Alsace, the eugenic utopia of Ungemach was restored without fanfare. It endured in this form for about four decades more. The point is not that its proprietors endorsed – or even that they were indifferent to – all the murders and forced sterilizations of the mentally ill, but that brutal interventions of this kind did not then appear relevant to a local initiative to promote healthy breeding. The perpetuation of this eugenic imperative in diverse forms in the decades to follow is a topic full of fascination. It is not as if the Ungemach community could be cut off from the profound economic and social changes of the postwar decades. For example, the rules against mothers working outside the home eventually had to be abandoned. By the time this experiment reached its end, eugenics had been subject to much bitter criticism. By then, however, it had already gone a long way towards reinventing itself as marital and psychological counselling, medical insurance systems and social practices tied to the measurement of ‘human capital’. As this book eloquently demonstrates, it is scarcely possible, in a society so besotted with genetics, to wall off the dreams of eugenics from psychological, educational and economic ideals. Though condemned now by almost everyone, eugenics, in its broader sense, lives on, and remains still a vital subject of research and reflection. Theodore M. Porter is distinguished professor of history at UCLA. His research has emphasized the history of science, especially the interactions of natural and social sciences and bureaucratic as well as scientific uses of data and statistics. His books include The Rise of Statistical Thinking (1986);

Foreword xv

Trust in Numbers: The Pursuit of Objectivity in Science and Public Life (1995); Karl Pearson: The Scientific Life in a Statistical Age (2005) and, most recently, Genetics in the Madhouse: The Unknown History of Human Heredity (2018), all at Princeton University Press.

Abbreviations

S ADBR Archives départementales du Bas-Rhin [Departmental archives of the Lower-Rhine] AES

American Eugenics Society

AMS Archives municipales de Strasbourg [Municipal archives of Strasbourg] AN

Archives nationales [French national archives]

BNF

Bibliothèque nationale de France [National Library of France]

CAC

Centre des archives contemporaines [French Centre for national contemporary archives]

CAFJU Conseil d’administration de la fondation ‘Jardins Ungemach’ [Board of the Ungemach Gardens Foundation] C.C.

Cheminements chinois [Chinese paths; typescript by Alfred Dachert]

CUS

Communauté urbaine de Strasbourg [Urban community of Strasbourg]

ER

Eugenics Review

FFEPH Fondation française pour l’étude des problèmes humains (‘Fondation Carrel’) [French Foundation for the Study of Human Problems, ‘Carrel Foundation’] INED Institut national d’études démographiques [National Institute for Demographic Studies] INOP Institut National d’Orientation Professionnelle Institute for Vocational Counselling]

[National

IUSSP International Union for the Scientific Study of Population

Abbreviations xvii

MSPP Ministère de la Santé publique et de la Population [Ministry of Public Health and Population] SGF

Statistique générale de la France [General statistics of France]

VWW Vom Werden eines Werks [On the becoming of a work; typescript by Alfred Dachert].

Note The manuscripts Cheminements chinois [Chinese paths] and Vom Werden eines Werks [On the becoming of a work] are part of the personal archives of François Dachert that are now available at Institut Mémoires de l’Edition Contemporaine, Fonds Maurice Olender (Rosental, Destins de l’eugénisme, 2016).

Introduction

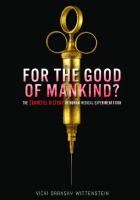

S Several years ago, while going through the archives that the director of the French National Institute for Demographic Studies (INED), François Héran, had just opened for historical research, my attention was drawn to a thick document folded several times. I opened it carefully. Short sentences. Figures. Graphs. A large poster gradually unfolded before me. It was designed to be viewed and read from a distance, or by a small crowd, and was clearly intended for a hygiene exhibition – I would later find out it was for the one that was held in Strasbourg in 1935. Its content, reproduced below (Figure 0.1), was surprising. Entitled ‘The Ungemach Gardens in Strasbourg’, it touted the ‘successful results’ achieved over the past eleven years by a garden city ‘built on a charming site at the outskirts of the city of Strasbourg’. The goal of this ‘creation with eugenic designs was to promote the development of valuable elements of society and to help them advance more quickly than others’, through the ‘deliberate selection of young households in good health’ who could rent a house in the city ‘at a low price while their family grew’. These results were quantified and compared. The garden city of Ungemach had a much higher birth rate than Strasbourg and France. Infant health, measured by the mortality rate for children under two, was ‘above the average’ for the city. As they grew, the children’s height and weight exceeded those of their French and German counterparts. Living in the garden city even improved the parents: their ‘level of orderliness and cleanliness’, which a commission rated annually on a scale of one to ten, had progressed from 7.7 to 9.5 since they had moved there. The data demonstrated the success of the ambitious mission entrusted to the city: to increase ‘the number of valuable elements in the society of tomorrow’ – already quite a task – and even more, to help ‘guide human evolution towards more rapid advancement’. I could have just scoffed or expressed outrage at this eugenic profession of faith. But for a historian, mockery mainly reflects the laziness of

2 A Human Garden

the living in understanding what have become the unclear rationales of the dead. As for indignation, after ironically labelling it ‘holy’, Michel Foucault prophetically warned that ‘experience shows that we can and should reject [its] theatrical role’:1 he thought it better to think and act. This cautionary note is all the more relevant since eugenics, from the very beginning and throughout its history, has been rebutted in other ways than hindsight claims to moral superiority.2 What bothered me about the document was, first of all, that I could not place it. What was this experiment? Why was its presentation to the general public included in the papers of one of the most diligent and creative demographers of the twentieth century, Louis Henry, who founded the discipline of historical demography in the 1950s? The interest of Alfred Sauvy, one of the great ‘modernizing experts’ of France during its postwar economic boom, deepened the mystery. In a letter dated 26 June 1951, the INED director assured the mayor of Strasbourg, Charles Frey (1888–1955), that his institute was following ‘with great interest the results of this interesting creation with eugenic purposes’.3 Five years earlier, in July 1946, one of Sauvy’s officials, Albert Michot, had submitted a flattering account of the city following a visit.4 This correspondence raised a new question. What did this explicit embrace of eugenics mean, six years after the end of the Second World War, in a country like France, which was thought to have remained steadfastly immune to such scientistic and anti-egalitarian ideology? What light does it shed on the work of an author like Sauvy who was then in the process of choosing the title Biologie sociale [Social biology] for the second volume of his magnum opus, Théorie générale de la population [General theory of population]?5 These strange ‘Ungemach Gardens’ had cut me loose from familiar moorings: a rare occurrence in historical research on contemporary France that was unsettling… and fascinating. Initial documentary research assured me that this was more than an anecdotal curiosity. The Ungemach Gardens, a small twelve-hectare garden city located in northeast Strasbourg’s Wacken neighbourhood, were an architectural pride of the city, for their green urbanism and their 140 little houses built shortly after 1920 in a nineteenth-century Alsatian style. They received sustained coverage in interwar architectural journals,6 and have been the subject of numerous and valuable works – research articles, theses and dissertations – by architectural and urban historians in Strasbourg and elsewhere.7 However, with regard to the garden city’s ideology and principles that Alfred Sauvy found so appealing, historiography was mostly silent, or exclusively focused on their pronatalist aspects. They were only seriously

Introduction 3

Figure 0.1. Performance of Ungemach Gardens (poster for the 1935 hygiene exhibition in Strasbourg). CAC 20010307 9 Louis Henry papers.

4 A Human Garden

and fully considered in four pages of the seminal book by the American William H. Schneider on French interwar eugenics,8 as well as two university theses that tried to relate the content of the experience to its urban form.9 An unfortunate amnesia! From their creation in the 1920s through the 1960s, the Ungemach Gardens were nationally and internationally renowned for what they were, that is, a place where a vigorous pronatalist and eugenic policy was being pursued. In 1925 Ungemach served as a showcase for Strasbourg during the visit of French Prime Minister Paul Painlevé. Besides the routine institutional visits it was one of the four sites selected by the Commissioner of the Republic in Strasbourg to receive him.10 Beginning in 1931, the founding journal of British eugenics, Eugenics Review, successively opened its columns to a presentation of the experiment and then of its ‘results’,11 before providing a full translation of the 1935 poster.12 Over the decade the journal included twelve additional references – articles, conference and book reviews and letters to the editor – expressing enthusiasm for this ‘first practical implementation of positive eugenics’, which authors and readers hoped would soon be replicated in the United Kingdom and expanded more broadly.13 In 1933 Paul Popenoe, a well-known popularizer of eugenics in the United States, paid a glowing tribute to Ungemach in the final edition of the most widely read textbook on the issue at the time, Applied Eugenics.14 Six years later, in his fiercely anti-republican pamphlet Pleins pouvoirs [Full powers], the famous writer Jean Giraudoux praised the ‘remarkable efforts undertaken by Strasbourg’ as the main exception to what he considered the unfortunate absence of ‘either an empirical or theoretical state doctrine on eugenics’ in France.15 In 1946 the Californian businessman Charles Matthias Goethe (1875–1966), a pioneer of nature conservation, patron of the University of Sacramento and committed eugenicist, focused on Ungemach Gardens, which he had just toured, in a book advocating for a kind of botanical eugenics.16 In the 1950s and 1960s INED requested annual population statistics from the garden city, which also received sympathetic attention from the Ministry of Public Health and Population. The experiment was started by a non-profit foundation, but the city of Strasbourg took over on 1 January 1950 and, as will be seen, continued to support it until the mid-1980s. By staying on the scientific and political radar for so long at both the national and international levels, the Ungemach experiment, despite its small size – or thanks to it, microhistory would argue – can help to delineate a phenomenon that is extremely difficult to grasp: French eugenics in the twentieth century. Just twenty years ago, the consensus was still that apart from the initiatives of a few zealots around 1900 and the

Introduction 5

introduction of a premarital medical examination by the Vichy regime, France had remained immune to eugenics.17 This idea of a national exception most often referred to conceptual considerations. Republicanism was seen as a safeguard against the non-egalitarian aspirations of this scientistic creed.18 French scientists’ embrace of neo-Lamarckism was not conducive to the acceptance of the Galtonian eugenics invented across the channel that primarily focused on hereditary transmission.19 Another factor, common to all the ‘Latin’ countries, was the Catholic Church’s opposition, which was formalized with the publication of the papal encyclical Casti Connubii on 31 December 1930. Leaving aside the Gospel’s laudatory account of the simple-minded, this aversion reflected one of the watchwords of political Catholicism during the interwar period: the emphasis on ‘Life’ with a capital L placed by pro-family associations went hand in hand with the rejection of eugenic tools such as sterilization and abortion. In England, the birthplace of eugenics, the famous Catholic author Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874–1936) had derided eugenics as a pagan ideology based on a cult of technology and of the state, and on its supporters’ impious assertion of a hierarchy of human beings.20 A second explanation given for France’s opposition to eugenics – an explanation mistakenly believed to automatically bolster the previous one – was the strength of pronatalism. In a country where fertility had started declining at the end of the Old Regime, that is, several decades before the rest of Europe, the conviction that the country’s power depended on its number of births started to spread in the 1860s in response to the Prussian military threat. On the eve, and especially in the aftermath of the First World War, it took hold in the political and administrative spheres and translated into a fledgling demographic policy. The common sense argument was that if France was pronatalist it could not be eugenic, too hastily setting population quantity against quality. As in many other countries,21 the 1980s saw the first challenges to this entrenched view. The Foucauldian exhortation to revisit the ideological genealogy and connotations of knowledge encouraged a critical reassessment of the prevailing heroic history of French public policies, especially on demographic matters. Two overlooked issues suddenly became controversial in the academic community, before being picked up by the media. Significantly, both relate to the criminal record of the Vichy regime, which was also put in the spotlight after a long period of inattention. The first concerns the policy of elimination through starvation to which the insane were allegedly subjected during the Occupation. In 1987 the physician Max Lafont denounced this ‘soft extermination’, tragically embodied in the figure of Camille Claudel, who starved to death in 1943 and was the hero of a 1988 movie by Bruno Nuytten.22

6 A Human Garden

The second controversy, which is not unrelated to the first, concerns the legacy of Alexis Carrel (1873–1944). This French surgeon left to pursue his career in the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century and received a Nobel Prize in 1912, making medical history with the advances he enabled in the critical area of transplants. His 1935 bestseller Man, the Unknown, a scientistic essay on the relations between nature and society, remained a library staple for ‘men of culture’ through the 1960s and was reprinted several times until the very end of the twentieth century. But as Carrel became an icon of the French New Right in the 1970s and ’80s, historiography started denouncing the eugenics of his sociobiological, deterministic and elitist thinking that was merciless towards the ‘weak’. Once again, the Vichy period was at the heart of the debate since the surgeon had returned to France during the Occupation and was entrusted by Marshal Pétain with the leadership of the French Foundation for the Study of Human Problems (FFEPH). This major institute for research and studies popularly known as the ‘Carrel Foundation’ primarily focused on the relations between biology, economics and social sciences.23 And yet again there was both a historiographical and media aspect to the argument. Although some historians tried to put Carrel’s eugenics into perspective, the controversy led the Claude Bernard University in Lyon to rename its Alexis-Carrel medical school in 1996; many French streets were also renamed.24 In the 2000s, the first controversy abated while the second grew. The historian Isabelle von Bueltzingsloewen conducted a thorough investigation of the ‘soft extermination’ and found that the excess mortality of the insane from starvation resulted more from exacerbated conditions of undernourishment in asylums during the Occupation than from a deliberate policy, in the broader context of a breakdown in relations between the families of the insane, doctors and psychiatric institutions.25 Meanwhile, evidence of Alexis Carrel’s ideology was confirmed.26 While he certainly made a significant contribution to science, the doctor from Lyon was part of the generation of Anglo-American scholars who started their careers at the beginning of the twentieth century and adopted an extreme deterministic conception of the transmission of hereditary characteristics. Historian Garland E. Allen described these scholars as an ‘older style eugenics movement’, in contrast to their younger counterparts, who shared many eugenic values but started questioning hereditary determinism in the 1920s.27 Another interesting point is that Carrel was also known to be a devout Catholic, challenging the notion that it is impossible to reconcile these two ideologies.28 This initial double focus on the Vichy regime was only natural. It echoed the most famous and darkest aspects of the history of eugenics,

Introduction 7

namely the way the movement unfolded in various states that practised forced sterilization in insane asylums – there was a thin line between compulsory sterilization by doctors and ‘voluntary’ sterilization consented to by patients and their family – and, of course, the mass extermination policies of Nazi Germany.29 Although the great historian Paul Weindling has shown that the eugenic path does not necessarily lead to Nazism,30 it is obvious that extermination ideology was closely based on eugenic arguments believed to be backed by science, and that its massive appeal resulted from the easy but devastating combination of these arguments with ways of thinking developed over what might be called the ‘racial century’ that began around 1850.31 Following this first critical review phase, over the past twenty years a series of works have undertaken the difficult task of extricating the vast body that eugenics represented in the twentieth century from its criminal uses. The task is difficult in several respects. First of all, other manifestations of eugenics that were retrospectively obscured are akin to a geological repository and require working through the archaeology of knowledge and policy. In an initial assessment of this extrication process made in 1998, the sinologist Frank Dikötter underscored its global nature: ‘soft approaches, which combined an emphasis on the environment with hereditarian explanations, were far more widespread than previously suspected … . Neo-Lamarckian notions were more important than strictly Mendelian explanations, an emphasis that supported a preventive approach to eugenics in which the environment had to be cleansed of all deleterious factors damaging racial health’ (bearing in mind that at the beginning of the twentieth century the semantic range of the word ‘race’ extended from outright racism to sanitary concerns about impacting the public health of a nation). As there is now mounting evidence of the importance of neo-Lamarckism in such diverse countries as Russia, Brazil, China and France between the two world wars, Dikötter continues, a radical reassessment of its scientific and political meanings seems seriously overdue. A fresh historical appraisal of the available material that included countries outside Europe might reveal that the hard Mendelian eugenics familiar from studies of Britain and Germany was not a dominant approach in many developing parts of the world.32 The Dutch historian rightly added that in order to understand the degree of support for eugenics in the interwar period, this reassessment required a shift away from simply focusing on the movement’s leaders towards studying its ‘anonymous supporters’ and its dissemination in popular culture.33

8 A Human Garden

This double change in emphasis had major implications. The idealist history of ideas created an analytical classification of the arguments involved – distinguishing between eugenics and social Darwinism for example34 – that was essential but not sufficient. Eugenics is a set of ideological discourses that originated in certain elites’ fear of being demographically overwhelmed by undesirable groups due to the latter’s higher fertility rates. These often-repetitive discourses were dramatic and sensationalist, even by today’s standards, and too easily provoke contemporary ‘repulsive fascination’.35 But it is harder, if one takes a step back from the tragic extremes of mass murder and forced sterilization, to pinpoint the actual role of eugenics in public and private action. The process requires carrying out the difficult task of tracing a social history of scientific and political ideas – or, to use the elegant and accurate expression of Jean-Claude Perrot, a concrete history of abstraction.36 A review of the literature is not enough. The dissemination of ideas needs to be tracked, as does their appropriation by people, environments and various institutions, their reformulation following exposure to other theoretical frameworks, and especially the reality check provided by their implementation. In so doing, ‘ideas’ no longer remain neatly contained in analytically organized drawers, but rather reveal their infinite plasticity and their ability to produce ‘rationally’ improbable arrangements. They become ‘malleable through time, space and the contingency of events’ to the extent that ‘even the most doctrinaire of ideologies still constitutes a potentially ephemeral internal coalition of ideas – its indeterminacy and pluralism cannot be overridden for too long’.37 The gap between formulated thought and emerging thought – I am transposing Bruno Latour’s famous dichotomy here38 – certainly applies to the history of political ideas in general. However, it is a particular challenge for eugenics. Since its emergence in the first two decades of the twentieth century in the United Kingdom, eugenics took distinct paths following different timelines in various countries. But in all cases, from the outset it met strong opposition that was equal parts knee-jerk and theoretical. The aversion to eugenics, its non-egalitarianism and its coercive thrust with regard to marriage and procreation is attributable to the entrenchment of political liberalism in the anthropology of contemporary Western societies. In countries like France, the United Kingdom and the United States, eugenicists deplored and denounced the mocking of their ideal in a number of texts: ‘The picture of society organized as a studfarm arouses disgust. It is sometimes feared that the Eugenic programme would involve the destruction of normal family life and the mutual affection upon which it is based. To favour the “successful types” it may be argued, would result in the evolution of hard, unlovely characters’.39

Introduction 9

This rejection may have been beneficial for civil society, but in retrospect has proven costly for the historian: depending on the country, era, environment and terms of expression, the history of doctrinaire eugenics appears at times to be a lot of talk, and at others, deliberate concealment. The best example of the latter during Vichy is the history of the Carrel Foundation. While it was free of the constraints of publicity that a parliamentary democracy and free press ordinarily entail, the Foundation was reluctant to display the combination of eugenics and heredity in the presentation of its programmes.40 An example of the consequent difficulty in understanding the contours of this subject is the political and scientific programme that was self-described as ‘Latin eugenics’ in the 1930s. This programme extended from Romania to Argentina, including France, Italy, Mexico and much of South America, and culminated in a meeting in Paris in 1937.41 It requires a shift in emphasis to more diffuse, more diverse and less sensational – but still structuring – ways of addressing the ‘quality of the population’.42 Analysis of Latin eugenics reveals ‘new’ social spaces, covering health, social, demographic and other applications, where eugenics was manifested in less spectacular ways: not just doctors and geneticists but also statisticians and economists; not just eugenic societies but also those focusing on biotypology; not just sterilizations but also academic guidance, occupational health, urbanism, marriage counselling, sexual education, prenatal care, sorting of foreign and internal migrants, treatment of ethnic minorities and so on.43 The difficulty here is to exhibit the subject without either hypostatizing or diluting it, to understand its coherence (in terms of doctrine as well as scholarly and expert networks) while observing its amalgamation and transformation in a vortex of racist, hygienist, nationalist, progressive, feminist and other aspirations. In some respects, this contrast between a coercive eugenics with high visibility and a more discreet preventive eugenics recalls the opposition between ‘negative’ or punitive eugenics oriented towards eliminating undesirables (through murder or sterilization, as well as disincentives to marriage and procreation) and ‘positive’ eugenics characterized by social hygiene measures. However, one should be wary of this ideal dichotomy, which was created by a follower of Francis Galton, the man who founded eugenics in 1883, or more precisely, who thus labelled and systematized a body of doctrines that had been developing throughout the nineteenth century.44 Be it ‘positive’ or ‘negative’, eugenics must be considered as a whole,45 initially conceived as one of the last retaliatory responses in the (not always latent) civil war that unfolded for over a century in the aftermath of the French Revolution.46 As a product of the growing authority of science, it represented an attempt at a reasoned argument against the

10 A Human Garden

principle of equality among citizens that progressively spread in liberal democracies during the nineteenth century, a time of arduous struggle for universal male suffrage and the dismantling of legal barriers to social mobility. A case in point is the argument of the Oxford philosopher Ferdinand Schiller (1864–1937), proponent of a ‘eugenic aristocracy’: the real argument for political equality is not that men are born equal, but that they are born so unequal in so many ways, and that society requires such a variety of services, that the only practicable form of political organization is to ignore their inequalities and to give votes to all, and then to trust to the intelligent few to manipulate or cajole the many into abstaining from fatal follies.47

This served as a basis for a wide variety of ideological uses. Just as eugenics might equally well promote ‘the improvement of the quality of the population’ or condemn its ‘degeneration’, it was conducive to both creating biologically based social hierarchies and advancing social reform projects. While eugenics most often served conservative and reactionary movements seeking to ‘scientifically’ legitimize the social order, it also helped to support progressive approaches seeking to ‘improve the quality’ of dominated populations, or even to challenge the social reproduction of elites with a hierarchy based on merit and the inherent potential of individuals. However, underlying these various appropriations is a deeper substrate that cannot be ignored: in all cases eugenics presupposes that people or groups are of different value, which is deemed measurable and, through a wide variety of means, improvable – or to the contrary, degradable to the point of violating ethical principles of preservation of life.48 Beyond the fact that it has proven to be a protean concept across a range of historical situations, eugenics arguably did not begin as a primarily biological theory but rather as a social theory, or even, as will be seen, a moral theory based on three axioms: (1) there is a difference in the quality of human beings; (2) this difference can be measured by certain scholars and experts; (3) it is subject to change at the scale of populations. One of the thrusts of this book will be to explore how theories and policies that implicitly or explicitly rank people came to be implemented and legitimized in a political democracy based on the principle of equality. This process will be complicated by the difficulty of determining the boundaries of eugenics as well as a challenge that one might call civic. To treat eugenics as a subject of history precludes both simple condemnation and blind euphemization. To avoid these two pitfalls, I will follow the ‘pragmatic’ and quasi-ethnographic approach used in many contemporary social science studies, starting with microhistory. Born

Introduction 11

of the historiography of the early modern era, microhistory has to my knowledge rarely been applied to twentieth-century mass politics, even though its recent application to the history of the Shoah has demonstrated its insightfulness.49 Despite the rich historiographical discussion of the 1990s,50 references to ‘microhistory’ and ‘games of scales’ are too often used to re-legitimize the monograph – a worthwhile but more restricted approach. Yet the two are quite different. Microhistory goes beyond the ‘grassroots’ by selecting both ‘exceptional and normal’ elements to observe that are often out of step with the most common social forms; understanding these elements requires and facilitates illuminating entire swathes of the society within which they operate. This constraint does not allow for the application of a preset model. In the present case it will lead me to focus more on the history of institutions and knowledge, including literature since the Ungemach Gardens project was largely written in the language of tragic theatre. The history of the eugenic garden city (and of its creator) will be the subject of one of this book’s three parts. It will to a large extent form my ‘field’, but not my subject: I will rather seek to build on its heuristic and one might say experimental interest. This interest does not only lie in the fact that the British followers of Galton saw the Ungemach Gardens as the first ‘practical’ realization of ‘positive’ eugenics. It also and primarily lies in a double paradox. First, while a German- and English-speaking businessman, Alfred Dachert, developed the concept of the Ungemach Gardens in the first two decades of the twentieth century in German Alsace, the project was actually implemented in France – except during the Second World War – with the support of national and municipal public authorities. The garden city’s history thus tests one of the boundaries of the history of eugenics, that is, the opposition between the ‘social hygienist’ Latin eugenics I briefly outlined and the more hereditarian basis of original eugenics, which took root in the United States and Northwestern Europe, spanning the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Germany and Scandinavia. There were certainly different styles of national eugenics that portrayed themselves as such and distinguished themselves or even explicitly opposed each other,51 but historiography, especially when focusing on practices, points to the limitations of the dichotomy between a preventive and environmental Latin world and a hereditarian and punitive Nordic world.52 One of my goals will therefore be to figure out how the modus operandi of a residential area designed according to British eugenics principles was grasped, accepted and even endorsed by the French government. The issue is all the more relevant considering that the experiment began as a privately managed one in 1923, but had a long run under city

12 A Human Garden

management after the Second World War, with the support of the state in both cases. This brings us to the second paradox of the history of the Ungemach Gardens: for the most part – forty years – it unfolded after the collapse of the Third Reich, which one would have thought had completely discredited eugenics. My subject will gradually take form in the resolution of this double paradox. Transatlantic and Western European eugenics as well as, and perhaps especially, the expansion of public policies, the creation of social security, and more generally the conscious effort to remake society during the twentieth century, will shape this book’s scope of thought. I am obviously not claiming that I will exhaustively address such broad topics. My more modest goal is to attempt to use the history of a eugenic neighbourhood in Strasbourg as a means to raise a number of issues that haunt our history and cloud our perception of the present.

Notes 1. Michel Foucault, ‘Face aux gouvernements, les droits de l’homme’, in Dits et écrits, Paris, Gallimard, 2001, vol. 2, pp. 1526–27 [orig. ed. 1984]. 2. Franz Boas, ‘Eugenics’, The Scientific Monthly, 3, 5, 1916, pp. 471–78. 3. Strasbourg urban community archives [Arch. CUS], 269 W 64 and National archives, INED collection [French national institute for demographic studies], Louis Henry papers, 20010307/9. 4. Albert Michot, Rapport sur la fondation “Les Jardins Ungemach”, à Strasbourg, Paris, INED library archives, 1946, no 3071. 5. Alfred Sauvy, Théorie générale de la population, vol. 2, Biologie sociale, Paris, PUF, 1954. 6. Jean Porcher, ‘Les “Jardins Ungemach” à Strasbourg’, L’Architecte, 4, 1927, pp. 33–38; Stéphane Claude, ‘La “Cité-Jardins Ungemach” à Strasbourg’, Urbanisme, 1, 1932, pp. 182–85. 7. Jeanne Boulfroy, Le Problème de la ville moderne: la cité jardin, doctoral thesis supervised by Étienne de Groër, Institute of Urbanism at the University of Paris, 1940; Stéphane Jonas, ‘Les Jardins Ungemach à Strasbourg: une cité-jardin d’origine nataliste (1923– 1950)’, in Paulette Girard and Bruno Fayolle Lussac (eds), Cités, cités-jardins: une histoire européenne, Talence, MSHA publications, 1996, pp. 65–85; Jonas, ‘Les Jardins Ungemach: une cité-jardin patronale d’origine nataliste’, in L’Urbanisme à Strasbourg au XXe siècle. Actes des conférences organisées dans le cadre des 100 ans de la cité-jardin du Stockfeld, City of Strasbourg, 2010, pp. 50–64. Also see this Introduction, n. 9. I was not able to review the architecture thesis of Anne Staub, Cités-Jardins à Strasbourg, 1976, the first part of which is devoted to Ungemach garden city. 8. William H. Schneider, Quality and Quantity: Eugenics and the Biological Regeneration of Twentieth-Century France, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1987, here pp. 124–28. Also see Jean-Noël Missa and Charles Susanne (eds), De l’eugénisme d’État à l’eugénisme privé, Paris and Brussels, De Boeck Université, 1999, p. 17, n. 30.

Introduction 13

9. Catherine Lavanant, La cité-jardin Ungemach à Strasbourg, 1923–1929, Master’s thesis in art history for the University of Strasbourg supervised by François Loyer, 1991, call number MAIT/1991/LAV at the University of Strasbourg and, more impressionistically, Gina Marie Greene in the fifth chapter of Children in Glass Houses: Toward a Hygienic, Eugenic Architecture for Children during the Third Republic in France (1870-1940), doctoral thesis in architecture supervised by Edward Eigen, Princeton University, 2012. 10. Cf. ch. 1, n. 49. 11. Alfred Dachert, ‘Positive Eugenics in Practice: An Account of the First Positive Eugenic Experiment’, Eugenics Review [ER], 23, 1, 1931, pp. 15–18; Dachert, ‘Les Jardins Ungemach: Child Development’, ER, 23, 4, 1932, p. 336; Dachert, ‘Les Jardins Ungemach’, ER, 25, 2, 1933, p. 105. 12. ‘Les Jardins Ungemach’, ER, 27, 3, 1935, pp. 230–31. 13. R. Austin Freeman, ‘Segregation of the Fit: A Plea for Positive Eugenics’, ER, 23, 3, 1931, pp. 207–13; ‘Notes of the Quarter’, ER, 23, 1, 1931, pp. 3–6; Charles Wicksteed Armstrong, ‘Positive Eugenics in Practice’, ER, 23, 2, 1931, p. 188; Armstrong, ‘The Insufficiency of Education’, ER, 23, 4, 1932, pp. 316–17; R. Austin Freeman, ‘Social Decay and Eugenical Reform’, ER, 24, 1, 1932, pp. 47–49; ‘The Society’s Further Projects’, ER, 24, 1, 1932, pp. 12–13; ‘Notes of the Quarter’, ER, 24, 2, 1932, pp. 83–86; George Short, ‘Eugenics and Socialism’, ER, 24, 2, 1932, pp. 164–65; Charles Wicksteed Armstrong, ‘A Eugenic Colony Abroad: A Proposal for South America’, ER, 25, 2, 1933, pp. 91–97; J.H. Marshall, ‘A Scheme of Practical Eugenics’, ER, 30, 2, 1938, pp. 154–56; Charles Wicksteed Armstrong, ‘A Scheme of Practical Eugenics’, ER, 30, 3, 1938, p. 226; Armstrong, ‘Eugenic Garden City’, ER, 31, 1, 1939, p. 77. 14. Paul Popenoe and Roswell Hill Johnson, Applied Eugenics, New York, Macmillan, 1933 [orig. ed. 1918]. On the popularity of this book, see Will B. Provine, ‘Geneticists and the Biology of Race Crossing’, Science, 182, 4114, 1973, pp. 790–96, here p. 791. 15. Jean Giraudoux, Pleins pouvoirs, Paris, Gallimard, 1950 [orig. ed. 1939], pp. 33–34. 16. Charles M. Goethe, War Profits… and Better Babies, Sacramento, CA, Keystone Press, 1946. 17. See the historiographical overview provided by Anne Carol in the introduction to her Histoire de l’eugénisme en France, Paris, Seuil, 1998 (as well as chapter 13 on the history of the prenuptial certificate). 18. Pierre-André Taguieff, ‘L’introduction de l’eugénisme en France: du mot à l’idée’, Mots, 26, 1991, pp. 23–45. 19. Yvette Conry, L’Introduction du darwinisme en France au XIXe siècle, Paris, Vrin, 1974; Jacques Léonard, ‘Le premier congrès international d’eugénique (Londres, 1912) et ses conséquences françaises’, Histoire des sciences médicales, 17, 2, 1983, pp. 141–46. 20. Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Eugenics and Other Evils, London, Cassell, 1922. 21. Lene Koch, ‘Past Futures: On the Conceptual History of Eugenics – A Social Technology of the Past’, Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 18, 3–4, 2006, pp. 329–44. Major works created in this context include Daniel J. Kevles, In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1985; Richard A. Soloway, Birth Control and the Population Question in England 1877– 1930, Chapel Hill, North Carolina University Press, 1982. Among the major contemporary documentary resources, cf. Alison Bashford and Philippa Levine (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2010; Patrick Tort (ed.), Dictionnaire du darwinisme et de l’évolution, Paris, PUF, 1996. Also see the effective summary by Jakob Tanner, ‘Eugenics before 1945’, Journal of Modern European History, 10, 4, 2012, pp. 458–79.

14 A Human Garden

22. Max Lafont, L’Extermination douce: la mort de 40 000 malades mentaux dans les hôpitaux psychiatriques en France, sous le régime de Vichy, Le Cellier (44), Éd. de l’AREFPPI, 1987. 23. Alain Drouard, Une inconnue des sciences sociales: la Fondation Alexis Carrel, 1941–1945, Éd. Maison des sciences de l’homme, 1992; Paul-André Rosental, Population, the State, and National Grandeur: Demography as a Political Science in Modern France, Berne, Peter Lang, 2018, ch. 3 [orig. ed. 2003]. 24. See Lucien Bonnafé and Patrick Tort, L’Homme, cet inconnu? Alexis Carrel, Jean-Marie Le Pen et les chambres à gaz, Paris, Syllepse, 1992. 25. Isabelle von Bueltzingsloewen, L’Hécatombe des fous: la famine dans les hôpitaux psychiatriques français sous l’Occupation, Paris, Aubier, 2007. 26. Andrés H. Reggiani, God’s Eugenicist: Alexis Carrel and the Sociobiology of Decline, New York, Berghahn Books, 2007; Marie Jaisson and Éric Brian, ‘Les races dans l’espèce humaine’, in Maurice Halbwachs, Alfred Sauvy et al., Le Point de vue du nombre (1936), critical edition by both authors, Éd. de l’INED, 2005, pp. 25–51, here pp. 46–49. 27. Garland E. Allen, ‘The Misuse of Biological Hierarchies: The American Eugenics Movement, 1900–1940’, History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences, 5, 1983, pp. 105–28, here pp. 125–26. 28. Alexis Carrel’s spiritual writings include Prayer, London, Hodder & Stoughton, 1947; The Voyage to Lourdes, New York, Harper & Brothers, 1950; Reflections on Life, New York, Hawthorn Books, 1952. For a broader review of the Catholic Church’s attitude towards eugenics (and marriage), see Étienne Lepicard, ‘Eugenics and Roman Catholicism. An Encyclical Letter in Context: Casti Connubii, December 31, 1930’, Science in Context, 11, 3–4, 1998, pp. 527–44 and, for detailed analyses of the content and limitations of accommodations between eugenicists and Catholics, see Sharon M. Leon, ‘“Hopelessly Entangled in Nordic Pre-suppositions”: Catholic Participation in the American Eugenics Society in the 1920s’, Journal of the History of Medicine & Allied Sciences, 59, 1, 2004, pp. 3–49; Donald J. Dietrich, ‘Catholic Eugenics in Germany, 1920–1945: Hermann Muckermann, S. J. and Joseph Mayer’, Journal of Church & State, 34, 3, 1992, pp. 575–600; Britta McEwen, ‘Welfare and Eugenics: Julius Tandler’s Rassenhygienische Vision for Interwar Vienna’, Austrian History Yearbook, 41, 2010, pp. 170–90. 29. Ian Dowbiggin, The Sterilization Movement and Global Fertility in the Twentieth Century, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2008; Paul A. Lombardo (ed.), A Century of Eugenics in America: From the Indiana Experiment to the Human Genome Era, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 2011; Mark A. Largent, Breeding Contempt: The History of Coerced Sterilization in the United States, New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press, 2008; Gunnar Broberg and Nils Roll-Hansen, Eugenics and the Welfare State: Sterilization Policy in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Finland, East Lansing, Michigan State University Press, 2005; Randall Hansen and Desmond King, Sterilized by the State: Eugenics, Race, and the Population Scare in Twentieth-Century North America, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2013; Paul Weindling, ‘International Eugenics: Swedish Sterilization in Context’, Scandinavian Journal of History, 24, 2, 1999, pp. 179–97; Alexandra Minna Stern, ‘Esterilizadas en nombre de la salud pública: raza, inmigración y control reproductivo en California en el siglo XX’, Salud Colectiva, 2, 2, 2006, pp. 173–89. 30. Paul Weindling, Health, Race, and German Politics between National Unification and Nazism, 1870–1945, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1989. 31. A. Dirk Moses, ‘Conceptual Blockages and Definitional Dilemmas in the “Racial Century”: Genocides of Indigenous Peoples and the Holocaust’, Patterns of Prejudice, 36, 4, 2002, pp. 7–36. For a longer historical perspective, see Maurice Olender, Race and Erudition, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 2009.

Introduction 15

32. Frank Dikötter, ‘Race Culture: Recent Perspectives on the History of Eugenics’, American Historical Review, 103, 2, 1998, pp. 467–78, here pp. 473–74. 33. Ibid., p. 475. On the dissemination of this eugenic culture, cf. Susan Currell and Christina Cogdell (eds), Popular Eugenics: National Efficiency and American Mass Culture in the 1930s, Athens, OH, Ohio University Press, 2006. 34. Unlike Galtonian eugenics in particular, Darwinism is not strictly hereditarian. Furthermore, the concept of ‘social Darwinism’ encompasses a cluster of theories that are Darwinian in name only, the tendency being to retain the Spencerian notion of ‘struggle for life’. Cf. Pierre-André Taguieff, ‘Eugénisme ou décadence? L’exception française’, Ethnologie Française, 24, 1, 1994, pp. 81–103; Daniel Becquemont, ‘Une régression épistémologique: le “darwinisme social”’, Espaces Temps, 84–86, 2004, pp. 91–105. 35. Marcel Gauchet and Gladys Swain, La Pratique de l’esprit humain: L’institution asilaire et la révolution démocratique, Paris, Gallimard, 1980, p. 153. 36. Jean-Claude Perrot, Une histoire intellectuelle de l’économie politique, XVIIe–XVIIIe siècles, Paris, Éds de l’EHESS, 1992. 37. Michael Freeden, Liberal Languages: Ideological Imaginations and Twentieth-Century Progressive Thought, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2005, p. 132. 38. Bruno Latour, Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers through Society, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1987. 39. C.J. Hamilton, ‘The Relation of Eugenics to Economics’, ER, 3, 4, 1912, pp. 287–305, here p. 291. Among countless others, the sexologist Havelock Ellis recognized that forbidding a fraction of the population from marrying ‘was clearly an impracticable demand, scarcely to be allowed by social opinion …. The inevitable result was that eugenics was constantly misunderstood, ridiculed’ (Havelock Ellis, ‘Birth Control and Eugenics’, ER, 9, 1, 1917, pp. 32–41, here p. 35). 40. Cf. ch. 4, n. 56. 41. Premier congrès latin d’eugénique, Paris, 1er–3 août 1937, Paris, Masson, 1938. 42. Francesco Cassata, Building the New Man: Eugenics, Racial Science and Genetics in Twentieth-Century Italy, Budapest, Central European University Press, 2011; Andrés H. Reggiani, ‘Dépopulation, fascisme et eugénisme “latin” dans l’Argentine des années 1930’, Le Mouvement social, 1, 2010, pp. 7–26; as well as the (premature?) synthesis by Marius Turda and Aaron Gillette, Latin Eugenics in Comparative Perspective, London, Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 43. Nancy L. Stepan, The ‘Hour of Eugenics’: Race, Gender and Nation in Latin America, Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press, 1991; Julia Rodriguez, Civilizing Argentina: Science Medicine and the Modern State, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2006; Belén Jiménez-Alonso, ‘Eugenics, Sexual Pedagogy and Social Change: Constructing the Responsible Subject of Governmentality in the Spanish Second Republic’, Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, 39, 2, 2008, pp. 247–54; Andrés Reggiani and Hernán González Bollo, ‘Dénatalité, “crise de la race” et politiques démographiques en Argentine (1920–1940)’, Vingtième Siècle, 95, 3, 2007, pp. 29–44; Alexandra Minna Stern, ‘Responsible Mothers and Normal Children: Eugenics, Nationalism, and Welfare in Post-Revolutionary Mexico, 1920–1940’, Journal of Historical Sociology, 12, 4, 1999, pp. 369–97; Joel Outtes, ‘Disciplining Society through the City: The Genesis of City Planning in Brazil and Argentina (1894–1945)’, Bulletin of Latin American Research, 22, 2, 2003, pp. 137–64; Yolanda Eraso, ‘Biotypology, Endocrinology, and Sterilization: The Practice of Eugenics in the Treatment of Argentinian Women during the 1930s’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 81, 4, 2007, pp. 793–822; Marisa A. Miranda, ‘La biotipología en el pronatalismo argentino (1930–1983)’, Asclepio, 57,

16 A Human Garden

44.

45.

46. 47. 48. 49. 50.

51. 52.

1, 2005, pp. 189–218; Alexandra Minna Stern, ‘From Mestizophilia to Biotypology: Racialization and Science in Mexico, 1920–1960’, in Nancy P. Appelbaum, Anne S. Macpherson and Karin Alejandra Rosemblatt (eds), Race and Nation in Modern Latin America, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2003, pp. 187–210. Francis Galton created a definition of eugenics in his Inquiries into Human Faculty and its Development, London, Macmillan, 1883, p. 17, n. 1. For more on his specific contribution, see the critical review by John C. Waller, ‘Ideas of Heredity, Reproduction and Eugenics in Britain, 1800–1875’, Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Science, 32c, 3, 2001, pp. 457–89 and Diane B. Paul and Benjamin Day, ‘John Stuart Mill, Innate Differences, and the Regulation of Reproduction’, Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, C39, 2008, pp. 222–31. ; Ted Porter, Genetics in the Madhouse: The Unknown History of Human Heredity, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2018. The essayist Caleb W. Saleeby, in Parenthood and Race Culture: An Outline of Eugenics, London, Cassell, 1909, p. 172, claims to have created the dichotomy between positive eugenics and negative eugenics that was ‘approved by Mr. Galton’. In his mind, ‘the two are complementary, and are both practiced by Nature: natural selection is one with natural rejection. To choose is to refuse’ [my emphasis]. Furet, François. The French Revolution: 1770–1814, Oxford, Blackwell, 1996; Arno Mayer, The Persistence of the Old Regime: Europe to the Great War, New York, Pantheon Books, 1981. Ferdinand C.S. Schiller, ‘Eugenics as a Moral Ideal’, ER, 22, 2, 1930, pp. 103–9, here pp. 107–8. Also see Bertrand Russell, Marriage and Morals, New York, H. Liveright, 1929. Richard Weikart, ‘Darwinism and Death: Devaluing Human Life in Germany 1859– 1920’, Journal of the History of Ideas, 63, 2002, pp. 323–44, here p. 334. Tal Bruttmann et al. (eds), Pour une microhistoire de la Shoah, Paris, Seuil, coll. ‘Le Genre Humain’, 2012. Bernard Lepetit (ed.), Les Formes de l’expérience: une autre histoire sociale, Paris, Albin Michel, 1995; Jacques Revel (ed.), Jeux d’échelles: la micro-analyse à l’expérience, Paris, Gallimard-Seuil, 1996; Revel, ‘L’histoire au ras du sol’, Preface in Giovanni Levi, Le Pouvoir au village, Paris, Gallimard, 1989, pp. i–xxxiii. Liliane Crips, ‘Les avatars d’une utopie scientiste en Allemagne: Eugen Fischer (1874– 1967) et l’“hygiène raciale”’, Le Mouvement social, 163, 1993, pp. 7–23 also shows how in Germany ‘“social hygiene” experts saw France as a basket case’ (p. 17). Cf., among many references, Maria Bucur, Eugenics and Modernization in Interwar Romania, Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2002; Wendy Kline, Building a Better Race: Gender, Sexuality, and Eugenics from the Turn of the Century to the Baby Boom, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2001; Ivan Crozier, ‘Havelock Ellis, Eugenicist’, Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 39c, 2, 2008, pp. 187–94; Paul Weindling, ‘The “Sonderweg” of German Eugenics: Nationalism and Scientific Internationalism’, British Journal for the History of Science, 22, 1989, pp. 321–33.

Part I

The Intellectual and Political History of a Human Garden (1880s–1980s)

S Human laboratory, experiential landscape, breeding ground for the ‘elite class’ – this is how you should see the garden-city Ungemach. —Suzanne Herrenschmidt, speech at the awarding of Alfred Dachert with the Legion of Honor, Strasbourg, 11 December 1947

Chapter 1

The Acceptance of a Eugenic Experimentation

S A Socialist Paradise for the Middle Class On Sunday 5 October 1923, a new neighbourhood was publicly unveiled in Strasbourg – ‘Ungemach Gardens’, a subdivision of forty houses that was built in the northeastern part of the city, barely two kilometres away from the cathedral, on the Wacken lands that the military had liberated.1 The site was ‘crossed by a small river – the Aar – and the water and old trees gave the site a picturesque and relaxing feel’.2 In line with both the latest standards of comfort – running water, bathroom and laundry room – and the popularity of regional architecture at the time,3 ‘the detached houses, with their terracotta colour, large rooves, outside staircase and white shutters, resembled the houses of small Alsatian cities from 1830’.4 The crowds came. Two hundred and ninety-two households submitted applications during this first phase to rent out forty houses. Interest did not wane as one hundred additional houses were built in the following years. Granted, the city offered young ‘middle-class’ couples rents that were a quarter cheaper than those of the city of Strasbourg’s housing office, not to mention free benefits like the garden. At first glance, the Ungemach Foundation’s generous offer was among a raft of initiatives seeking to address the shortage and high cost of housing. The Great War’s destruction aside, Strasbourg saw its population triple during Germany’s annexation (1871–1919). Before the war, the reformist mayor Rudolf Schwander had seen through the creation

20 A Human Garden

of new, wider roads in the city, embellishment and improved sanitation of buildings.5 After the city’s return to France in 1918, Jacques Peirotes, the city’s first socialist mayor, increased housing aid. Over his sixteen years at the helm, he proved to be ‘the biggest builder of the century in Strasbourg’.6 After Paris and Lille, Strasbourg was the third French city to secure, under the law of 21 July 1922, the reclassification of four-fifths of the former fortified city – in this case a real estate holding of over five hundred hectares. The Cornudet law of 1919 directed each city to implement a development plan:7 while the reclaimed space was to be devoted to a ‘green belt’ non aedificandi,8 the municipality greenlighted the full array of the era’s social housing – low-rent housing known as Habitations à Bon Marché (HBM), allotments and garden-cities.9 Ungemach Gardens was among the latter. The mayor provided the land free of charge and built the roads. In return, the Ungemach Foundation committed to maintaining low rents and transferring the housing development property to the city on 1 January 1950.10 Initial rents, which tracked the municipal cost of living index, ranged between 2,760 and 3,200 F annually. The target market was the small middle class: at the time, the average monthly salary in France was 2,135 F.11 The Peirotes policy was favoured by a legal framework that was specific to the reintegrated French Alsace. Resulting from the Gemeindeordnung of 6 June 1895,12 it provided greater flexibility than national legislation13 and allowed the mayor to pursue broad economic and social interventionism.14 Social housing played a major role here. A generation before the institution of social security in 1945 would relegate it to playing second fiddle, social housing was heir to an era when the ‘social question’ was primarily an urban issue. Since the middle of the nineteenth century, concerns about containing the vices of the working class and regulating rural emigration to the cities and new industrial basins focused on housing policies. In contrast to the degrading assistance provided to the ‘destitute’, these policies were meant to help the ‘working poor’ build an independent and responsible life. This social policy choice was reflected in an 1894 law that offered access to affordable housing through ownership rather than tenancy, principally via municipal and private funding. The moderate socialist Peirotes represented the left wing of the reform network that had been developing and coordinating this policy since the 1890s. He was one of the figureheads of municipal socialism,15 wherein housing played a key role for redistributive and health purposes, as well as for pork-barrel politics. Held up to public obloquy by the communists for his ideological positioning to the right of his party, the French

The Acceptance of a Eugenic Experimentation 21

Section of the Workers’ International, the socialist Peirotes was forced to seek a constituency beyond working-class voters.16 Just like the social democratic party across the Rhine,17 he turned to the ‘middle class’ that had become a vibrant force due to both the active political mobilization of artisans in Alsace,18 and the growing power of new worker categories: managerial staff in industry, skilled service workers, and women employed in new business sectors. These worker groups were akin to self-employed workers in terms of their standard of living, but differed in their work status, tax situation and right to social benefits.19 In the bilingual Alsace of the 1920s, housing policies also played an important role in transforming the plural expression ‘classes moyennes’ [middle classes] into the equivalent German singular ‘Mittelstand’ [middle class].20 In 1922 Peirotes created and presided over the City of Strasbourg’s Office of Low-Rent Housing,21 which enjoyed a remit that ‘only rivalled that of Paris and Lille’22 in France. He thus deepened a segmented and hierarchical housing policy, ranging from the elimination of slums to homeownership access. The Ungemach Foundation initiative crowned his strategy: it offered the middle class a highly valued proposition, a ‘garden city’. The principle of a garden city had been formalized by the British Ebenezer Howard (1850–1928) in a book published in 1898, Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform, and had spread throughout Europe and North America.23 As both a utopic and practical solution, the garden city was a response to problems raised by cities’ exploding populations, offering ‘the working-class elite’24 the possibility of accessing what was considered to be the most politically stabilizing form of housing: an individual house surrounded by a garden that, in addition to its contribution to the domestic economy, would channel the worker’s free time into virtuous activities.25 By 1910 the city of Strasbourg had incorporated the garden city into its collective ‘mid-tier’ rental programmes via the Stockfeld ‘suburbgarden’.26 At the end of Peirotes’ term, this garden was joined by the Alexandre Ribot (1930–1932) garden city, and then the Robertsau garden city, launched in 1934.27 Ungemach Gardens was part of this wave of city-supported initiatives, but it differed from the others in one respect: rather than provide access to homeownership, it offered residents rentals. This apparently minor difference might appear to be attributable to a ‘social’ mission, but it actually masks a very particular approach that went hand in hand with an unprecedented regulation of residents’ lives.

22 A Human Garden

The Selection Ungemach Gardens was not a social housing initiative like the others, although they regularly claimed to be so in order to ensure their continued existence. They were conceived and implemented as an experiment – as a human laboratory seeking to shape the ‘quality of the population’ via a scientific selection of its residents, who contractually committed to meeting childbearing objectives. The initial selection and obligation to procreate were intended to turn the garden city into a ‘breeding ground for elites’, and on a broader scale to test the hypothesis that natural selection mechanisms can be influenced by housing. The centrepiece of this enterprise was its ranking system for candidate households, built on the bedrock principle of selection. This term should be understood in a specific sense: it linked the scholarly concept of ‘natural selection’ popularized by Darwin with an administrative approach to ‘sorting’ and ‘classifying’ households applying for rentals. The Ungemach Foundation wanted to demonstrate that placing well-selected couples in suitable conditions enables the ‘domination of valued elements in the generation of tomorrow and allows these elements to overtake those of lesser value’.28 It is worth examining these selection criteria from the perspective of the applicants by comparing Eugène and Marthe Schumacher, who were selected when they first applied in 1927, and Jean and Marie Simon, who experienced three failures before they gained the right to live in the garden city.29 The two couples shared many traits. The women were both born in 1901 and identified themselves as housewives, which was typical of ‘middle-class’ households at the time. Eugène was born in 1897 and was an office worker at the time of application. His annual salary of 14,655 F was double the French average.30 Jean was four years younger and higher up in the services sector. In 1933, when he and his wife finally gained admission, his job as a customs comptroller was bringing in an annual salary of 20,000 F. This relatively high income penalized the Simons by placing them in the upper middle class. Based on a purportedly scientific approach, the application included fifteen questions and followed a precise methodology to measure what could be called the ‘potential fertility’ of households. First, how many children were they likely to have? The question was approached with an array of data points, starting with the applicants’ ages: husbands had a point removed for each year over thirty years of age; the threshold was lowered to twenty-five years of age for wives. The length of marriage was also taken into account on a sliding scale: young couples were awarded

Figure 1.1. The evaluation of the Schumacher couple. © Municipal Archives in Strasbourg. 99 MW 199.

The Acceptance of a Eugenic Experimentation 23

24 A Human Garden

a bonus (six points if they were in their first year of marriage, four for second-year marriages, two for third-year marriages), whereas each year beginning with the fourth one resulted in a two-point deduction. Each child already brought into the world was awarded twenty points, but this total was divided by the length of marriage to measure what one might call the rhythm of descendant creation. Thus, the three Schumacher children, born within four years of marriage, provided fifteen points to their parents (that is, 3 times 20 divided by 4). One of the Foundation’s objectives was to minimize the uncertainty linked to the drivers of human procreation: the financial support provided to ‘quality households’ was to be repaid through a virtual guarantee that they would bring many descendants into the world. For this reason, each of the spouses’ living brothers and sisters yielded the applicants a bonus point. This award for what demographers prosaically call ‘useful births’, that is, the births of individuals who survive long enough to reach the age of reproduction, was based on the premise that fertility and life expectancy are both inheritable. This deterministic hypothesis is of a piece with the ‘original’ eugenics – the one that was established in England at the end of the nineteenth century; so was the idea that marriages later in life produce less robust children.31 For the same reasons, poor health was an eliminating factor in practice: fifty points (question 14) were removed if the couple provided a medical certificate, likely because they thought they would improve their odds by providing one. From the outset, this set apart the Foundation’s eugenics approach from the era’s social initiatives. The application then pivoted to intentions. Plans to hire help, house third parties or, for the wife, to practise a profession, were frowned upon, and resulted in applicants being docked fifty points. Herein lay the explanation for the Simon couple’s failure when they first applied in March 1926: ‘the woman works at the prefecture’, a Foundation employee tersely noted. Indeed, the experimentation paired with a clear social gender divide. The mother was expected to be devoted to her children in a complete (no professional activity), direct (no domestic help) and exclusive (no housing of third parties) way. These criteria were loosened at the margins after lessons were drawn from the first wave of rentals: a maid would be ‘tolerated’ for families with four or more children,32 as would be the presence of dependent grandparents in the home. The houses’ interior architecture reflected these criteria. As the local press boasted, the houses ‘were designed with a view to sparing the mother of the family, who must raise many children without the help of a housekeeper, any unnecessary exertion’. Specifically, ‘a laundry room, which also served as a bathroom, was placed next to the dining room so

The Acceptance of a Eugenic Experimentation 25

Figure 1.2. Interior architecture of Ungemach houses. © Municipal Archives in Strasbourg. 843 W 607/4.

26 A Human Garden

that the mother could, without moving, simultaneously take care of her children, meal cooking and laundry’.33 Even more than panoptic will, this showed the era’s interest in the rationalization of domestic activities. Far from being limited to the Fordist factory, taylorization applied to homes,34 in a bid to minimize parents’ physical effort and ‘stress’. The respective treatment of the two parents was therefore not entirely asymmetrical. Indeed, the garden city first aimed to free the husband from ‘housing concerns’ by ensuring ‘a serene, healthy and calm environment’ to support his professional activity.35 Reflecting the era’s theories about ‘fatigue’ and the ‘human motor’,36 the expectation was that this environment would be conducive to higher professional productivity. But allowing the mother to ‘prepare dinner while also doing laundry without having to run around and without losing sight of her children’,37 and ensuring ‘maximum order for every effort’38 via numerous closets and storage, paradoxically reflected a recognition of her domestic work. During the interwar period, she was provided ‘home delivery of milk, bread, groceries and meat’ so that she would not have to bother ‘getting dressed to run errands’39 and expend energy on ‘useless and tiring movements, waits and chatter’.40 This is also why a kindergarten was built in the garden city in 1928. Protecting the parents’ serenity was a means to encourage them to bring many children into the world and raise them in the best conditions. What appears here is one of this book’s main themes. Eugenics was not just a biological theory. Maximizing the ‘quality’ of children involved taking into account psychological factors. The couples’ behaviour therefore constituted a major assessed element. The invitation to produce names of references (question 13), paired with guaranteed elimination (100-point deduction) in the event of inaccurate information (question 12), was a classical way to test the reliability of applicant couples. But ‘order and cleanliness’ were also verified (question 15). An ad hoc commission visited the homes of preselected applicants: it assessed the insides of homes and administered a ‘questionnaire’, to come up with a score between one and ten.41 A fifty-point deduction was applied for any ‘uncleanliness, disorder or bedbugs’, making them fatal flaws. The visiting commission worked with the disinfector Tschoeppé, who created a business in 1919 that still exists today. For reasons that remain unclear, it was the home visit that sank the Simon couple’s third application. While some of these selection practices were widespread at the time, the Ungemach experiment is an original and exceptional one because it drew on publicly declared eugenic principles that were widely supported

The Acceptance of a Eugenic Experimentation 27