A Comparison of the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene Burials of North Africa and Western Europe: Grim Investigations: Reaping the Dead 9781407306841, 9781407336855

Archaeology has a unique and significant perspective to offer the territorial debate. In the 1970s Saxe and Goldstein ar

207 110 14MB

English Pages [271] Year 2010

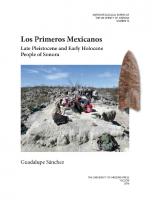

Front Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preface and Acknowledgements

Table of Contents

Abbreviations used in the Appendixes

1. Introduction

2. Exploring Territoriality through Human Remains

3. The Methodology

4. A Summary of the Database

5. Cemeteries and Territoriality in Mesolithic Scandinavia

6. Cemeteries and Territoriality in the Ibéromaurusian and Capsian Maghreb

7. Territoriality – Discussion and Conclusions

8. Appendix A: The Relationship between Cemeteries and Occupation Debris

9. Appendix B: Problematic Cemeteries in the Maghreb

10. Appendix C: Tables from Chapter 2

11. Appendix D: Tables and Figures from Chapter 3

12. Appendix E: Tables from Chapter 4

13. Appendix F: Tables and Figures from Chapter 5

14. Appendix G: Tables and Figures from Chapter 6

15. Appendix H: Tables and Figures from Chapter X

16. Bibliography

Recommend Papers

- Author / Uploaded

- Emma Elder

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

l na tio ne di nli ad l o ith ria W ate m

BAR S2143 2010 ELDER LATE PLEISTOCENE AND EARLY HOLOCENE BURIALS

A Comparison of the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene Burials of North Africa and Western Europe Grim Investigations: Reaping the Dead

Emma Elder

BAR International Series 2143 9 781407 306841

B A R

2010

A Comparison of the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene Burials of North Africa and Western Europe Grim Investigations: Reaping the Dead

Emma Elder

BAR International Series 2143 2010

ISBN 9781407306841 paperback ISBN 9781407336855 e-format DOI https://doi.org/10.30861/9781407306841 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

BAR

PUBLISHING

Dedication For Sandy, Ron and Ben.

relationships over time. This temporal perspective is vital given the inherently dynamic, unstable and unequal nature of power relationships which are continually open to contestation and redefinition. The Saxe-Goldstein hypothesis is flawed, but through exploring the archaeological record of Western Europe and North Africa with an emphasis on two cases studies (Mesolithic Scandinavia and Ibéromaurusian and Capsian Maghreb), this book aims to demonstrate that these flaws can be addressed, leaving us with a remarkably powerful tool.

Preface and Acknowledgements When Meggitt published his ethnographic work on the Mae Enga of Highland New Guinea in 1965 it’s doubtful he knew quite what he was about to unleash. After all, his observation that lineages legitimise their claims over scarce land through appealing to their ancestors during funerary rituals at graveyards did not seem particularly vital or striking. And yet Saxe, an American archaeologist, was so inspired he pounced on that relationship, reformulated it as a link between cemeteries and resource control, and included it as the last of the eight hypotheses he tested in his doctoral thesis, a thesis which (alongside the work of Binford) laid the foundations of processual funerary archaeology. In turn, his theory inspired a second doctoral dissertation, this time by Goldstein who further refined it, leading it to become known as the Saxe-Goldstein hypothesis. Many others went on to apply it to the archaeological record with interesting results. But it was so intimately entwined with Saxe/Binford processual approach to funerary studies that in the 1980s it was rejected as part of the post-processual shift and despite the efforts of several scholars, it has since remained in the graveyard of disused theoretical tools.

What you will find here is my DPhil dissertation, with the only changes being the removal of some figures and the modification of others. I’ve been very fortunate in the support I’ve received during my doctoral research and there are several people I’d like to thank. In particular, I’d like to thank my supervisor, Professor Nick Barton, for his encouragement, guidance and close attention to all the various versions of my thesis. Drs David Lubell, Mary Jackes, Silvia Bello and Louise Humphrey provided information, suggestions and advice, for which I’m grateful. In addition, I’d like to thank Dr Rick Schulting for help with radiocarbon calibrations, advice, and also – along with Professor Chris Gosden – for detailed feedback levelled at earlier versions of two chapters that appear in this book. I’d like to thank Naomi Freud and Drs Renee Hirschon, Tim Clack and Amy Bogaard for their support; I couldn’t have asked for better college advisors. St Peter’s College has been a wonderful place in which to study, and I’m grateful to the college for awarding me the Graduate Teaching Bursary and offering opportunities to present aspects of my research at the Graduate Seminars. Elvira Stadler provided invaluable assistance with my French translations and Jennifer Williams regarding the statistics, for which I’d like to thank them both. (All mistakes and misunderstandings remain my own.)

Nevertheless, here you’ll find a third doctoral thesis based on that same observation Meggitt made 45 years ago. It seems strange to me that it was rejected so forcefully given the things it united – social memory, ritual, power, and the cultural symbols and values associated with space – were so central to the postprocessual position. As this book argues, I’m convinced the hypothesis linking cemeteries and resource control provides an important avenue for investigating territoriality among prehistoric hunter-gatherers. Territoriality is a concept that has been explored by many different disciplines, ranging from biology and geography to psychology and anthropology. Archaeologists, however – particularly prehistoric archaeologists – tend to shy away from it.

However, this book wouldn’t have been possible in any shape or form without my parents. Words can’t ever express just how wonderful and incredible and supportive they are. Thank you so very, very much.

This is a shame because there is a great deal of ethnographic research among contemporary huntergatherers demonstrating that they do utilise territorial strategies, and the concept has been critically and carefully examined, particularly within geography. The work of Sack, for example, provides a political theory of territoriality as a spatial strategy of control that is ideally suited for use by archaeologists because it removes the preoccupation with whether it is an innate, biological imperative, and conceptualises it instead as a form of power. Archaeology has a great deal to offer the territorial debate, not just through answering questions other disciplines have posed, but through positing our own questions and developing our own avenues of enquiry. If we follow Sack as seeing it as a form of social behaviour then we become uniquely placed to study it from a perspective to which no other discipline has access. No other subject has recognised the link between cemeteries and territoriality in the same way, and no other subject has the ability to study change in territorial 2

Contents Page

Abbreviations used in the Appendixes

Page 5

1. Introduction

6

2. Exploring Territoriality Through Human Remains 2.1 The Saxe-Goldstein Hypothesis The Science of Death The Four Horsemen of the (Processual) Apocalypse Resurrecting the Ghost 2.2 Territoriality A Brief History of Territoriality Defining Territoriality The Saxe-Goldstein Hypothesis and the Archaeological Record What is a ‘Cemetery’? 2.3 Personhood 2.4 Social Memory 2.5 Conclusion

8 8 8 9 10 10 11 14 15 16 18 20 21

3. The Methodology 3.1 Funerary Rituals The Catalogue of Human Remains 3.2 Cemeteries and High MNI Sites High MNI Sites Cemeteries 3.3 A Terminology Inhumation vs. Bone Scatter Inhumation Primary Inhumation Secondary Inhumation Cremation Single vs. Group Burials and the Problem of Synchronicity Bone Scatter Bone Scatter type A Bone Scatter type B Bone Scatter type C Bone Scatter type D Bone Scatter and Taphonomy 3.4 Demographic Information 3.5 Cemeteries and Territoriality 3.6 Conclusion

23 23 23 23 24 24 25 26 26 26 26 27 27 27 27 27 27 27 28 28 30 32

4. A Summary of the Database 4.1 Taphonomy and the Database

33 33

5. Cemeteries and Territoriality in Mesolithic Scandinavia 5.1 Are all sites with an MNI ≥ 8 ‘cemeteries’? High MNI sites which are not Cemeteries Sites with an MNI ≥ 8 which are Problematic 5.2 Cemeteries, Settlements and Controlled Resources Did the cemeteries act as territorial markers? What did the cemeteries aim to control? 5.3 Comparing Cemetery with Non-Cemetery Funerary Rituals The Maglemose The Kongemose The Ertebølle Group 1: Eretebølle Sites with an MNI < 8

35 35 36 36 37 38 40 42 42 44 45 46

3

Group 2: Sites with an MNI between eight and 20 Group 3: Skateholm II, Skateholm I and Vedbæk-Bøgebakken Dichotomising Decomposition: Ground and Air, Humans and Animals, and Land and Sea 5.4 Understanding Territoriality in the Scandinavian Mesolithic Change through time in Costs Change through Time in Territorial Behaviour Change through Time in the Settlement-Subsistence System Conclusion

47 48 50 52 55 58 58

6. Cemeteries and Territoriality in the Ibéromaurusian and Capsian Maghreb 6.1 Are all sites with an MNI ≥ 8 ‘cemeteries’? Ibéromaurusian Sites which are Not Cemeteries Ibéromaurusian Sites which are Cemeteries Upper Capsian Sites which are Cemeteries 6.2 The Ibéromaurusian Ibéromaurusian Skeletal Remains Low MNI Sites The Ibéromaurusian and Capsian Cemeteries 6.3 The Capsian Capsian Skeletal Remains Low MNI Locales Capsian Cemeteries 6.4 Cemeteries, Settlements and Controlled Resources: Did the Cemeteries Act as Territorial Markers? Summary 6.5 How the Cemeteries Functioned as Territorial Markers 6.6 Conclusion

60 60 60 60 64 64 65 65 66 68 70 70 71 72 80 81 86

7. Territoriality: Discussion and Conclusions 7.1 What is a ‘Cemetery’? 7.2 Are ‘Cemeteries’ the only Type of High MNI Locale? 7.3 What is the Relationship – if any – between ‘Cemeteries’ and Other Types of High MNI Sites? 7.4 How do Cemeteries Function as Territorial Markers? 7.5 What Kind of Settlement-Subsistence System do Cemeteries tend to be Associated Within? 7.6 What ‘Resources’ do Cemeteries Aim to Control? 7.7 Do Cemeteries Always Give Rise to Mediation of the Same Sorts of Territorial Relationships? 7.8 What Notions of Property were Associated with the Resources? 7.9 What Made Resources ‘Restricted’? 7.10 Some Conclusions: A Return to the Saxe-Goldstein Hypothesis

88 88 90 90 92 93 94 95 95 98 99

8. Appendix A: The Relationship between Cemeteries and Occupation Debris

102

9. Appendix B: Problematic Cemeteries in the Maghreb

109

10. Appendix C: Tables from Chapter 2

116

11. Appendix D: Tables and Figures from Chapter 3

124

12. Appendix E: Tables from Chapter 4

127

13. Appendix F: Tables and Figures from Chapter 5

149

14. Appendix G: Tables and Figures from Chapter 6

180

15. Appendix H: Tables and Figures from Chapter 7

213

16. Bibliography

240

Please note that the CD referred to within the text has now been replaced with a download available at www.barpublishing.com/additional-downloads.html 4

Abbreviations used in the Appendixes For a discussion of the terminology please see Chapter 3. Contexts in which human remains have been discovered: IS Inhumation Single ISP Inhumation Single Primary ISS Inhumation Single Secondary IG Inhumation Group IGSP Inhumation Group Synchronous Primary IGSS Inhumation Group Synchronous Secondary IGDP Inhumation Group Diachronous Primary IGDS Inhumation Group Diachronous Secondary BS A Bone Scatter type A BS B Bone Scatter type B BS C Bone Scatter type C BS D Bone Scatter type D

Demography: A Adult of Unknown Sex AF Adult Female AM Adult Male C Child (100km) over large distances (Rahmani 2004); however, whether they moved as part of the seasonal round or passed through exchange systems is uncertain.

However, Lubell and his collaborators argued instead for settlement seasonality (Lubell et al. 1975, Lubell et al 1976, Lubell et al 1982-3, Lubell et al 1984, Lubell and Sheppard 1997) if for no other reason than the great number of sites (in the hundreds, if not in the thousands) that would have had overlapping catchment territories. Furthermore, if Capsian escargotières were sedentary their density would imply population figures well in excess of those accepted for very prosperous modern hunter-gatherers (Lubell et al. 1975). Both Balout (1955:428) and Pond discussed the possibility of transhumance between the High Constantine Plains and the northern Sahara along the major northeast-tosouthwest valleys of the Saharan Atlas (Lubell et al. 1976:910). Balout (1955) demonstrated the presence of Capsian sites in the Négrine region and emphasised the lack of barriers to movement via the valleys. Furthermore, Grébénart (1978) remarked on the rarity of land snails from sites with Capsian lithic assemblages in the Négrine and Ouled Djellal regions. Lubell et al. (1975) therefore speculated as to whether Capsian groups

As in the Ibéromaurusian, there is evidence that Site 12, Medjez II, Aïn Keda and Mechta el Arbi were associated with base camps (table 6.54). At Medjez II (CampsFabrer 1975), hundreds of bone, flint and limestone tools and debris were found, along with personal ornaments (bone pendants, egg shell beads), engraved stones, a flagstone and ochre. The faunal remains were dominated by hartebeest and gazelle, but the remains of aurochs, Barbary sheep, wild boar, horse, various felines, birds, lizards, tortoise and land snail shells were also present (Bouchud 1975). According to Bouchud (1975), all parts of the skeletons were identified, but no long bone was intact: these, together with the crania, were intentionally fractured to access the marrow and brains. In addition, the numerical relationships between the skeletal parts are 75

Grim Investigations: Reaping the Dead 2003). Two lines of evidence suggest this within the Ibéromaurusian and Capsian: lithics and dental ablation. To begin with the former, Lubell et al. (1984) suggested, based on lithic and skeletal data, that the Ibéromaurusian culture gave rise to the Capsian. There was, they asserted, a sharp increase in interior (Ibéromaurusian) population densities towards the end of a Late Pleistocene phase of aridity (1984:149) due to immigration of coastal groups. Although raised sea levels at the end of the Pleistocene inundated only small portions of the coast (except in the Gulf of Gabés), there is an indication that changing sea levels affected Ibéromaurusian settlement-subsistence systems at sites such as Tamar Hat. As sea levels rose, interior regions became more attractive for animals and humans. Those groups who moved inland would have encountered a range of new adaptive situations, which is reflected in the increased use of edge tools within analysed assemblages. As coastal groups expanded into the interior, coastal homogeneity (maintained by transcoastal contacts) perhaps became more difficult to sustain in areas that presented physical barriers to communication. This, together with the development of distinctive regional lithic styles, and regional differences in the newly occupied areas (e.g. flint resources, ecological conditions) could have caused the emergence of new lithic traditions, including the Keremian, Columnatian and Capsian (Lubell et al. 1984). There is, therefore, a suggestion that, from the Late Pleistocene on, Maghrebian cultures underwent a change in the utilisation of space, giving rise to greater variability between groups. It is possible that something of this can be seen in the evidence for dental avulsion.

rarely preserved, with the femurs and humeris’ comparatively rare (Camps-Fabrer 1975, Bouchud 1975). Mechta el Arbi yielded abundant lithics (Debruge 19231924, Pond 1928) made on a poor quality black flint (perhaps) collected from the nearby stream. A rich bone industry was recovered which included long and short points, awls, needles, bone pins and spatulas. Pendants were made on water worn pebbles, marine bivalves and incised bovidae teeth (Pond 1928). Two Bos phalanges may have been used as whistles (Debruge 1923-1924), and a boar tooth could have been used as a pendant. Seven astragali were found, each of which had a hole in one side; these were also interpreted as whistles. Other finds included ostrich egg shell fragments, red and yellow ochre, hammer stones and chert nodules. The abundant faunal remains included the bones of large and small mammals (Pond 1928, Debruge 1923-1924; Appendix A). Snail shells formed a large part of the assemblage, some of which exhibit perforations from where the cooked snails were removed (Mercier 1907; Debruge 1923-1924, Pond 1928). Similarly, an abundant lithic industry was found in Layer B at Aïn Keda, made on black and white good quality flint (although a few tools on coarse flints are also known). Other finds include three ostrich egg shell fragments, a stone pendant, and bone tools including stone smoothers and needles. Fragments of ochre, lead sulphide and lead ore were also found. Faunal remains were not common, but ruminant, Barbary sheep and gazelle bones were recovered, along with land and fresh water shells (Bayle des Hermens 1955, Camps 1974, Haverkort and Lubell 1999). Little information is available for Site 12 (Pond et al. 1938, Haverkort and Lubell 1999) but it was one of the sites on which Pond drew in his definition of escargotières, and it almost certainly contained lithics, bone tools, faunal remains and a few items of personal adornment in addition to the abundant snail shells. No published information is available (to my knowledge) for Bekkaria (Balout 1954, Roch and Roch 1963).

Dental avulsion is a ritual practice observed in the Ibéromaurusian and Capsian involving the extraction of healthy teeth for reasons other than ‘medical care’. This results in a considerable, though variable, degree of absorption of the alveolar border; and while in the upper jaw a gap of considerable size usually remains, in the lower jaw it nearly always shrinks to smaller proportions, and sometimes closes entirely due to mass migration forwards of the remaining dentition (Briggs 1955). According to Briggs (1955) the operation never caused any serious infection as the shrunken area of alveolar absorption is cleanly and smoothly healed in all cases but one (an adult male at Afalou bou Rhummel). However, while infection was rare, the impact of dental avulsion on the emergence and wear of the remaining teeth, and the cranio-facial structure of the individual, is widely documented.

The nature of the material utilised at these sites as locally available, together with their character as assemblages accumulated through the activities of all members of the social group, may indicate the existence of base camps. The length of occupation is less certain. According to table 6.35, Mechta el Arbi and Medjez II were the largest escargotières of the region in which they were found, and were substantially larger than Aïn Misteheyia, which was analysed by Lubell (2004a, b) to argue for a pattern of seasonal mobility. A similar interpretation – based on the available information – seems at least reasonable for the base camps associated with the Capsian cemeteries. 3.

Ferembach et al. (1962) observed in individuals at Taforalt that removal of the upper central incisors allowed the lower incisors to rise beyond their normal occlusal level. As there is no occluding tooth, the lower incisors often show evidence for less wear than the rest of the individual’s dentition, and is associated with a distinctive shift of masticatory and non-masticatory functions to the posterior teeth (Bonfiglioli et al. 2004). Indeed, the alteration of the normal occlusal plane and uneven wear patterns this creates is so identifiable that it is sometimes regarded as evidence for ablation even in

There may be evidence for regionality within the Ibéromaurusian and Capsian.

Regionality refers to increased group identification, and differentiation between groups, and is often expressed – among other means – by material culture, and associated with reduced mobility over smaller areas (Bergsvik 76

6. Cemeteries and Territoriality in the Ibéromaurusian and Capsian Maghreb associated with adult males, it is not clear how significant this pattern is. Intriguingly, a higher percentage (67%) of individuals found as bone scatter type A and B exhibit avulsion (table 6.57). Unfortunately, only two could be sexed (although it is interesting that ablation was documented in the male but not the female) and, as with the inhumations, only adults exhibit evidence for this activity. If we combine tables 6.56 and 6.57 (table 6.58) it becomes clear that while the number of adults who could be sexed is comparatively small, 67% of females show no evidence for avulsion whereas 100% of males do. The practice is conservative and tends to focus on the upper central incisors (table 6.59) and while there is variation in the number of teeth removed (table 6.60), most tend to lack only two.

the absence of associated maxilla (Humphrey and Bocaege 2008:111). Intentional removal of the anterior teeth during adolescence also has a marked affect on the cranio-facial morphology and on the mandibular-maxillar configuration (Hadjouis 2002, 2003), usually involving a reduction in facial height. Based on an analysis of crania recovered from Afalou bou Rhummel, Hadjouis (2003) found the resultant asymmetries in the facial architecture rendered the practice very noticeable, even without the visual impact of several missing teeth. Most studies are concerned to identify differences in practices between males and females, the age at which ablation occured (Camps 1974, Briggs 1955, CampsFabrer 1975, Chamla 1978) and change through time (Humphrey and Bocaege 2008), but interpretations remain contradictory. If we begin with the Ibéromaurusian, Boule and Vallois studied crania from Afalou bou Rhummel and found the dentition of four children aged 3-6 years and three adolescents aged 12-16 years exhibit no evidence for avulsion, while two remaining adolescents did. They therefore concluded that tooth knocking was practiced around puberty (summarised in Briggs 1955). Conversely, Hadjouis (2003) argued that two children (5-6 years) found at the same locale do exhibit evidence for the removal of the higher left central milk incisor. He further states that good citratization of the free edge of the jawbone of AbR 19 demonstrates the ablation of a tooth at an even younger age and therefore concludes this was an activity conducted pre-puberty, between 5-12 years. This interpretation concurs with that of Camps-Fabrer (1960), and Briggs (1955). Permanent incisors erupt between six to nine years, therefore – if this interpretation is correct – further analysis is required on the relationship of avulsion to milk and permanent dentition.

The cemeteries yielded evidence for an individual character of dental ablation. At Afalou bou Rhummel, there is a significant difference between males and females (table 6.61) as while 100% of the former exhibit evidence for avulsion of at least one tooth, only 71% of the latter had a tooth removed during life (Camps 1974, Hadjouis 2003). At Columnata (table 6.62) the percentage of individuals who exhibit avulsion is lower: 50% of males and 42% of females (Cadenat 1957, Maitre 1967, Hachi 2006, Chamla et al. 1970). Table 6.63 presents the available data for Taforalt, based on Camps (1974). Unfortunately he only describes dental removal for 8 (out of 31 or 25% of) females and 10 (of 39 or 25% of) males, and if these figures are accurate it would imply a very low rate of avulsion. However, Ferembach et al. (1962) comment that all adults from Taforalt show evidence for the removal of one or both upper middle incisors so these figures might be misleading. At Afalou bou Rhummel (table 6.61) there is variation in which teeth were removed: although ablation of the two upper median incisors is most common for males and females (70%), five other patterns were also described. Similarly, the removal of the two median incisors was most common at Taforalt (table 6.62) but there is a far lesser degree of variation. By contrast, Columnata shows a wider pattern of tooth removal (table 6.63) but the most common (60%) involved the ablation of all eight incisors. A chi-square test found the pattern at this cemetery and Afalou to be significantly different (table 6.64). Interestingly, a chi-square test found no difference in the percentage of females subjected to dental ablation at Afalou bou Rhummel and Columnata, but there is a significant difference in the percentage of males who did, and did not, have teeth removed (table 6.65, 6.66 and 6.67) with males much more likely at the former than the latter to exhibit avulsion.

However, the Ibéromaurusian individuals included in my database span a period of at least 7000 years (Medig et al. 1996, Barton et al. 2008), therefore, do not represent a single cultural group. It is unclear to what extent the differences in opinion reflect diachronic and synchronic variation. The low MNI sites shed little light on the question. It was suggested (Balout 1954, Camps-Fabrer 1960) that an individual at Champlain had a tooth removed upon reaching 14 years, but it is unclear what evidence this interpretation is based on given the mandible was not aged (Balout 1954, Camps-Fabrer 1960); indeed, there are no known crania of individuals aged between 10 and 20 years for the non-cemetery sites (see database). Therefore, it is uncertain at what age dental ablation was practiced; and we cannot exclude the possibility that the age varied, both between groups and over time.

Many scholars have searched for unifying trends in Ibéromaurusian practices of dental avulsion (e.g. Camps 1974) but what emerges from our examination of the data is not homogeneity but heterogeneity: the cemetery populations show internal commonalities that contrast in some manner with one another and with low MNI sites. It is uncertain whether the same is true of the Capsian cemeteries, given their smaller size and uneven quality of

Many adults at low MNI Ibéromaurusian locales (table 6.55, 6.56, 6.57, 6.58) show evidence for ablation. This includes 47% of buried individuals (table 6.56); intriguingly, however, while all males (MNI = 5) show removal of at least one tooth, only one female (of two) yielded evidence for avulsion. Given the suggestions made above that inhumation at low MNI sites was 77

Grim Investigations: Reaping the Dead It is possible the heterogenous practices of dental avulsion at the Ibéromaurusian and Capsian cemeteries represent symbolisation of group identity. This interpretation rests on an assumption that within each culture the graveyards were contemporary (and that the differences do not reflect change over time). Although the Ibéromaurusian human remains span around 7000 years (Medig et al. 1996, Barton et al. 2008), the cemeteries belong to the end of the period. The Ibéromaurusian deposits at Columnata were assigned to c.8800 BC, and the Columnatian to 6200 BC (Close 1980:163, Lubell 2001), which is slightly later than the results from Afalou bou Rhummel (Lubell 2001) and Taforalt (Lubell et al. 1992) where the bulk of the burials were interred between 10,000 and 8000 BC. (Note, however, that few radiocarbon analyses were undertaken – Hachi 1996, Lubell et al. 1992, Close 1980, 1984 – and we do not know when use of the cemeteries began and ended.) As for the Capsian, there are radiocarbon dates for only two cemeteries: Medjez II (Lubell 2001, Close 1980:164, Camps-Fabrer 1975) and Site 12 (Close 1984:19). At the former, determinations from the levels which yielded the human remains range from 5950±180 to 5080±160 bc (6900-3200 cal BC), which are comparable to results at the latter, which range from 5830±250 to 5360±390 bc (c.6000 BC) on materials in upper and lower levels (Close 1984:12). With regards to Bekkaria, Mechta el Arbi and Aïn Keda, I was unable to find chronological information aside from stratigraphic associations with Upper Capsian industries (Balout 1954). Based on the available material, we can tentatively suggest that three Ibéromaurusian (Afalou bou Rhummel, Columnata, Taforalt) and two Capsian cemeteries (Site 12 and Medjez II) were broadly contemporary, thus rendering an interpretation of dental ablation as a signifier of group identity at least feasible. This may support an argument of regionalisation. No geographic patterning could be identified in the low MNI avulsion practices; but direct radiocarbon dates on bone would clarify the issue. It would also be interesting to know whether the lithics (Sheppard 1987, Close 1977) and personal ornaments (Camps-Fabrer 1960) show similar evidence.

publication, but it is a possibility the available information does not contradict. There are hints of a difference in practice seen at the Capsian high and low MNI sites, although its significance remains uncertain: no reference is made to avulsion in many burial reports, and it is unclear whether this is indicative of its absence, poor preservation or inattention to the question. If we consider the demography of individuals who do and do not show evidence for dental avulsion found in inhumations (table 6.68) and as bone scatter type A, B and C (table 6.69) at the low MNI locales, there is no difference. When the data are combined (table 6.70) it is equally clear that there is a significant difference between males and females: all females show evidence for the removal of at least one tooth, whereas none of the males exhibit ablation. This might suggest it was a gendered ritual associated only with women. However, the cemeteries complicate the picture. If we exclude Mechta el Arbi and consider only Bekkaria, Aïn Keda, Site 12 and Medjez II (table 6.71), three females show evidence for the removal of a tooth while another three do not; and while most males (MNI = 5) do not show evidence for dental ablation, at least one (at Site 12; Balout 1954) does. Evidence for avulsion at Mechta el Arbi is complicated (see tables 6.72 and 6.73) as there is confusion in the literature (partly a result of application of different numbering systems to skeletal remains) but just as not all of the females at this cemetery were subjected to dental avulsion, some of the males do show evidence for ablation. Unfortunately, the cemeteries are too small and the published literature insufficient to allow a statistical comparison of avulsion at the cemeteries (Camps-Fabrer 1975, Bayle des Hermens 1950, Roch and Roch 1963, Balout 1954). However, although the patterning of tooth removal at the low MNI sites (table 6.74) seems more variable than at the high MNI locales (table 6.75), there are tentative indications among the latter to suggest a similar degree of variability existed between the Capsian disposal grounds, as among the Ibéromaurusian. What could explain this?

4. Dental ablation is a practice documented ethnographically among the Eke, Aka and Twa pygmies of the Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of Congo (A. R. Gould et al. 1984), the Luvale, Luchazi and Mbudna tribes in Zambia (Jones 1992) and the Mano and Gio tribes of Liberia (Scwab 1947). The reasons vary, but include puberty rituals (Goose 1963, Talbot 1967, Pindborg 1969) and to facilitate speech (Goose 1963), improve hunting prowess (Jones 1992) and enhance attractiveness (Schwab 1947, Bohannan 1956, Jones 1992); and as a means of symbolising tribal or cultural affiliation. For example, groups in Nambia modify their dentition to signal group affiliation (Van Reenen 1978), as do the Ngangela of Angola (Jones 1992) and the Nuer and Dinka of Sudan (Willis et al. 2008, Finucane et al. 2008).

The environmental features of the cemeteries.

Archaeologists have increasingly recognised that Mesolithic hunter-gatherers sometimes achieved a high level of cultural complexity, particularly those situated with respect to marine resources (Erlandson 2001, Yesner 1980, J. E. Arnold 1995, Sassaman 2004, Bailey and Milner 2002). In these contexts (Chapter 2), it is possible to argue for territorial control. But what about inland societies founded on terrestrial economies? Can these groups be associated with resources sufficiently abundant to warrant the ideological legitimisation of claims (cf. Dyson-Hudson and Smith 1978)? The material recovered from Aïn Keda, Columnata, Mechta el Arbi, Medjez II, Site 12, Taforalt and Afalou bou Rhummel was variable and is documented for all (except Bekkaria for which there is no published information) in Appendix A. All show an association between cemeteries and base camps (tables 6.54 and 6.76) and tended to be situated with 78

6. Cemeteries and Territoriality in the Ibéromaurusian and Capsian Maghreb in the valleys, oaks in the mid-altitudes and fir trees and cedars above 1200m altitude (Hachi et al. 2002), and is likely to have been forested during the period of occupation. The Oued Agrioun runs close to the site from the mountains into the sea and the cave would have overlooked a now inundated coastal plain (Lubell 2001); thus, the prehistoric environment encompassed a mixed landscape of mountains, forest and coastal plains. Coastal plains tend to support complex wetland ecosystems with high biodiversity (Nicholas 1998), and it is not impossible this cave provided access to such resources.

respect to the resources provided by wetland contexts (rivers, streams, coasts and chotts). There have, to my knowledge, been no reconstructions of the environmental context in which they were situated, but it is possible to speculate as to what they could have controlled given what we know of their archaeology and modern surroundings. Grotte des Pigeons, Taforalt, is located in Eastern Morocco at an altitude of 750m in the mountainous massif of Beni Snassen (a limestone ridge connected to the western chain of the Atlas mountains) and is near to the entry of the Zegzel valley (Roche 1953a, b). The upper section of the Zegzel-Cherraa hydro-system by which Taforalt is located – the ‘Haut Zegzel’ – is located upstream in a mountainous forest. The stream is fed by Liassic springs (Laghlalcha, Aïn Bourbah and Aïn Hallouma) and although the stream in its entirety is known as an ‘ephemeral river’, this upper section only occasionally runs dry. Temperatures are more stable than downstream and today’s bordering vegetation include laurel, willows, reeds, ferns, pomegranates, plum and fig trees and poplars (Melhaoui 2004). The upper reaches of the river support large populations of native fish (e.g. Barbus marocanus), and has a high biodiversity of mollusca and mammals. The flora also includes medicinal and herbal plants (e.g. Mentha, Rosmarinus), provides natural fibres and timbers, and is home to migratory birds (Melhaoui 2004).

The environmental context of Columnata is equally speculative. Located close to the Upper Capsian site of Aïn Keda (discussed below) in Sidi Hosni (Waldeck Rousseau), in the Tell Atlas mountains, Columnata is today located at the junction of three vegetation zones (the Mediterranean evergreen oak belt, the woodland steppe, and the shrub or tree pseudo-steppe and woodland) on the boundary of steppic North Africa and the Northern Sahara (Lubell 2001). To the north is found the Chelif, a river whose source is located in the Tell Atlas and which discharges into the Mediterranean via a fertile valley. A high plateau is found to the south with level terrain on which water collects during the wet season to form large, shallow lakes. On this plain are today located the Chott el Hodna and the Chott’ech Chergui (the second largest chott in North Africa) between which Columnata is located at equidistance. An extensive and enclosed depression containing permanent and seasonal saline, brackish and freshwater lakes and pools together with hot springs, chotts are home to diverse habitats, including steppic areas, aquatic lakes, salt marshes and brackish wetlands. It forms a remarkable feature of an arid region where water is often temporary (Masgidi and Islam 2005). The climatic and environmental conditions during the Ibéromaurusian and Caspian were different from today, but Masgidi and Islam (2005) make several pertinent points: Mediterranean wetlands are second only to the tropics in terrestrial biodiversity; they are abundant and diverse in the terrestrial and marine life they support; and were home to many of the agricultural, horticultural and medicinal plants that became important in later periods. While the configuration of the ecosystem(s) to which Columnata provided access was different, the Chott’ech Chergui is representative of Mediterranean wetlands in general (Masgidi and Islam 2005), and it is possible similar contexts were present and exploited by those who lived at Columnata.

Given the environmental changes that have occured since the Ibéromaurusian ended (discussed above), it is unclear how closely the contemporary ecology of Taforalt reflects the Late Pleistocene (Lubell 2001). However, riparian zones along river networks are among the most complex forms of ecosystem and support a bio-diversity and productivity far in excess of their spatial context (Nicholas 1998), and while the precise combination of available resources was probably different to that of today, there is no reason to think it was not as abundant. In addition, the cave provided access to both coastal plains and steppes of the Hauts Plateaux. The cave is next to Aïn Taforalt, a spring which reportedly never runs dry; and according to Roche (1972b) its large size, good light, proximity to food resources, easy defence and excellent views of the surrounding area would have made it especially favourable for habitation. Finally, the cave is positioned on the crossing of two natural routes of communication in an east-west and a north-south direction (Roche 1972b). All of these factors could have made the locale favourable enough to warrant territorial marking.

The area in which the Upper Capsian was present may, similarly, have been abundant in food resources during the Early Holocene. There are no major rivers but throughout the area are found marshes, seasonal pans and wadis which contain water throughout the year (Sheppard 1987). Precipitation was higher than today and Sheppard (1987:46) notes that in the summer of 1978 water ran through two wadis in, and adjacent to, the small Télidjene valley south of Tébessa. These are fed by springs, and in an area of 2,475km2 around Garet et Tarf there are over 250 springs, not including the lake (Garet et Tarf) itself.

Afalou bou Rhummel is situated on the eastern coast of Bejaia Bay, c.300km east of Algiers. It forms part of a vast karstic network that stretches along the Mediterranean, belonging to the Tellian area of caves and shelters of the Beni Segoual in the Babors massif (Merzoug and Sari 2008). Today the area receives 10002000mm of rain during 100-125 days of the year, with the maximum between November and February. The area is forested, with cork oak, elms, ashes and poplars present 79

Grim Investigations: Reaping the Dead There is one further aspect of the environment worth considering. The introduction of a pressure flaking technique at the Typical-Upper Capsian transition (Rahmani 2004) was associated with climate change and a shift in fauna from larger to smaller, aridity adapted species (Jackes and Lubell 2008). This is based on stratigraphic information from, for example, Relilaï (Vaufrey 1934-5), Kef Zoura D, Aïn Misteheyia (Jakes and Lubell 2008), El Mekta, Bortal Fakher (Rahmani 2004) and Aïn Dokkara (Tixier 1976) together with radiocarbon dates (Close 1980, 1984, 1988). The majority of human remains are associated with the Upper Capsian, including the cemeteries (Balout 1954). Although the act of burial is, first and foremost, a rite of passage, it is nevertheless interesting that Mechta el Arbi, Medjez II, Bekkaria, Aïn Keda and Site 12 were created and utilised after the shift to aridity and the alteration in the resource base. It is possible that, if we are justified in seeing the Capsian cemeteries as markers of control, there was a rearticulation of the relationship between communities and the resources they relied on in the face of environmental change. The cemeteries may represent control over increasingly scarce resources, or even a territorial expresson against the changing environment (cf. Larson 2003).

This area could have provided a habitat for the ungulates whose remains were found in deposits associated with the cemeteries. Ungulates live in small herds in a restricted range. In areas where grazing and water are adequate, hartebeest (a large portion of many faunal assemblages) can form herds of four to 15 and sometimes up to 30 animals (Sheppard 1987). He compared this archaeological data with that for the modern !Kung San (Africa) and ethno-historic Wintu (North America) and concluded that the Capsian, while representing a mid-way point in terms of resource availability, occupied a region with relatively spatially predictable, abundant populations of game. If we consider the specific locations of the Upper Capsian cemeteries this picture is reinforced. Aïn Keda rock shelter is situated in an east-west cliff that forms part of the Djebel Ghezoul. It is associated with a spring and its orientation is such that it receives morning sunlight and provides shelter from northerly and westerly winds (Bayle des Hermens 1955). As with Columnata, the site would have provided access to the Sersou Plateaux. Although part of the high steppes, it is today unusually well watered as it is traversed by several water courses (notably the Oued Mina and the Nahre Ouassel) and acts as a fertile antechamber to the vast semi-arid expanse of the Haut Plateaux, an undulating steppe that is today so dry it is sometimes considered part of the Sahara. However, it is crossed for most of the year by the Chelif as a chain of marshes and muddy pools and in the context of a higher rate of precipitation and cooler temperatures of the Early Holocene may have formed a more abundant region. It would also have been possible to cross the Ouarsensif Massif from the Sersou Plateaux to the Chelif Plaine via the Theniet al-Haad (Rushworth 2004:86).

Summary This section argued: 1. 2.

The escargotières of Medjez II, Mechta el Arbi and Site 12 are situated on the Constantine plain (Camps-Fabrer 1975, Balout 1954, Haverkort and Lubell 1991). Separated from the sea by a mountain range, the plain differs to the Haut Plateau in its higher level of precipitation and the presence of salt marshes. The majority of wadis flow in the direction of the salt marshes rather than to the Mediterranean Sea. There are also a series of playa basins that were almost certainly shallow lakes during the Early Holocene (Mussi et al. 1995). Slightly to the south, Lubell et al. (1975:46) commented that although the Télidjène Basin is semi-arid and characterised by steppe-grassland at the steppe-desert boundary, the water table has lowered considerably since the Roman period and the current ecology is a recent phenomenon. The more humid habitats – e.g. along the courses of perennial wadis and near springs – support poplars, willows, tamarisk, oleander, rushes and various thistles, and it is possible these plants, together with others such as oak, pine and juniper, are more characteristic of Early Holocene conditions. The mammalian remains from these escargotières include aurochs (Bos primigenius) which would be expected under the moister and cooler conditions likely to have prevailed at these higher altitudes (Mussi et al. 1995).

3. 4.

5.

6.

7.

80

The Ibéromaurusian and Capsian cultures may have utilised mobile settlement-subsistence strategies. Cemeteries of both periods were associated with occupation debris perhaps indicative of base camps. These base camps may have been occupied on a seasonal or multi-seasonal basis. The heterogeneous practices of dental avulsion within the two periods (Humphrey and Bocaege 2008) may point to its use as a means of symbolising group identity (Finucane et al. 2008); this, in turn, could indicate regionality. Literature discussed in Chapter 2 (e.g. DysonHudson and Smith 1978, Baker 2003, Sack 1986, Cashdan 1983) suggests that contemporary huntergatherers exhibiting a similar pattern of mobility to the Ibéromaurusian and Capsians were territorial (Sheppard 1987). Although the available faunal lists are difficult to compare, it is probable that Ibéromaurusian and Capsian subsistence strategies were somewhat different. The former had a coastal orientation (Brahimi 1978), but although some sites show evidence for the exploitation of marine foods, it is clear terrestrial resources were predominantly important (Camps 1974, Merzoug and Sari 2008, Roche 1963:152-4, Arambourg et al. 1934, Hachi 2006). The latter was a culture with an inland focus (Lubell et al. 1971, Lubell 2004a, b). Nevertheless, the Ibéromaurusian and Upper Capsian cemeteries are similar in their proximity

6. Cemeteries and Territoriality in the Ibéromaurusian and Capsian Maghreb

8.

For example, three pairs of scars were identified on the parietal bones of a c.20 year old female (‘bone scatter type A’) at Gambetta (table 6.77; Balout and Briggs 1949), each of which – based on the degree of healing – was made at a different time. The middle pair were produced around two weeks before death; the uppermost pair were caused first, around five years before death; and the lowermost pair were made at some point in between. The transverse and longitudinal sections suggest they were produced by sawing with a bevelled edge tool (Briggs 1955). Afalou bou Rhummel and Taforalt yielded crania with partially healed perforations interpreted as evidence for trephination (Dastugue 1962, 1975, Crubézy et al. 2001). The interpretation is equivocal, but these examples remain interesting given the parietal bone of a young child (‘bone scatter type A’) at El Bachir exhibits a perforation made by a flint tool a few weeks before death (Briggs 1955). There is a high incidence of cranial bones among the bone scatter type A (table 6.18), and at Ifri n’Ammar the head of a small child was detached from, and buried with the body (Ben-Ncer 2004a). Columnata shows a parallel as the head of an adult woman (H 08/a) was removed from, and buried with, the body (Cadenat 1957). If it is fair to see the head as a locus of bodily symbolisms, it is clear they were manipulated as a part of living and deceased identities.

to highly productive wetland habitats (Nicholas 1998) such as the coast, rivers, salt lakes and chotts, and well-watered plains, all of which are locales at which game would have been abundant and (perhaps) predictable. Several (Taforalt, Columnata and Aïn Keda) were located on natural communication routes, many are found in the vicinity of lithic raw materials, and all (from the cave opening and/or overlooking reaches) provided excellent views of the surrounding landscape (table 6.76). Upper Capsian cemeteries may be associated with a restriction of resources caused by an environmental shift.

Though many archaeologists, particularly Camps (1974), Grébénart (1978), Lubell et al. (1975), Balout (1955) and Morel (1974), for example, have achieved much in advancing our understanding of Ibéromaurusian and Capsian settlement-subsistence systems, further analysis is required to strengthen and nuance our interpretations. This could involve comparative zooarchaeological studies, techno-functional lithic analyses (cf. Merzoug and Sari 2008), and application of isotopic and radiocarbon techniques. It is therefore recognised my argument that the Ibéromaurusian and Capsian cultures provided a context in which territoriality was a feasible strategy of control is not as robust as one might wish; but, based on the available literature, it seems reasonable. Through returning to the high and low MNI sites outlined in the preceding discussions, the following section suggests the nature of territoriality in the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene Maghreb was of a very different order to that found in Mesolithic Scandinavia.

This symbolic system bears a loose parallel to those regarding the land/sea, decomposition and its avoidance, and humans/dogs identified for the Kongemose and Ertebølle in Chapter 5. However, unlike their Scandinavian counterparts, the Ibéromaurusian cemeteries do not present identifiable evidence for the ritual manipulation of symbolic dichotomies in the way discussed by Bell (1992). It remains unclear whether this is an accurate reflection of past realities or a failure to recognise ritual manipulations. Given the (archaeological) intangibility of behaviours associated with funerals, the latter is possible. Furthermore, the Moroccan and Algerian material was investigated in the early decades of the twentieth century in a colonial setting, and studies were abandoned for many years as a result of political events. Although new research is being conducted (e.g. Mikdad et al. 2002, Barton et al. 2008, Hachi 2006, Ben-Ncer 2004b), and although some early publications are exemplary (e.g. Arambourg et al. 1934), the quality as a whole is uneven, and in some cases (e.g. Taforalt) important information was lost. Despite these problems the available literature is, I think, sufficiently detailed that were symbolic dichotomies present at the low MNI sites, and manipulated via material culture at the cemeteries, they would be identifiable. That they were not recognised may suggest communities at Afalou bou Rhummel, Columnata and Taforalt legitimised their territorial control via different means. It is argued here that Ibéromaurusian groups mobilised their funerary rituals in a more direct manner.

6.5. How the Cemeteries Functioned as Territorial Markers If we are justified in arguing that Ibéromaurusian communities claimed resources, then who were the controllers and the controlled, and how did cemeteries function as territorial markers? As can be seen in the evidence for dental avulsion (Humphrey and Bocaege 2008), the head/mouth/teeth held symbolic importance as an identity marker, and one may legitimately wonder where this practice was performed and what happened to the removed teeth: were they thrown away, worn as ornaments or buried in ritual deposits? It is possible they were used as adornment – we have evidence for this in the Capsian at Bortal Fakher (Camps-Fabrer 1960) and a Columnatian child (H 21) at Columnata may have been buried with three human molars (Cadenat 1957) – but no such objects have been found for the Ibéromaurusian (Balout 1954). Indeed, isolated teeth are rarely recovered as disarticulated items (see table 6.18), which is interesting given they are among the most durable elements of the skeleton. Whatever was done to the extracted dentition may have been undertaken away from both high and low MNI sites. Intriguingly, there are other indications of the symbolic importance of the head.

As discussed above, there are several contrasts between the low and high MNI sites. There is a statistically significant difference in demography (table 6.78): 50% of those at the latter are children, but only 21% at the former 81

Grim Investigations: Reaping the Dead links with a static and ‘known’ past, but more as a means of reconstructing perceptions of the past in response to contemporary concerns … (H. Williams 2003:90).

died at an age younger than 20 years. Furthermore, group burials dominate the cemeteries but are absent at the low MNI sites (table 6.79; e.g. Arambourg et al. 1934, Cadenat 1955, 1957, Roche 1953a, 1953b, Balout 1954, Barton et al. 2008, and see database). Most graves at low MNI sites tend to consist of shallow (natural) pits (Camps 1966, Barton et al. 2008, Ben-Ncer 2004b, Barbin 1910, 1912; but see Camps 1966, Mikdad et al. 2002); by contrast, stone constructions are common at Columnata (Cadenat 1955, 1957), there is evidence at Taforalt for the use of Barbary sheep horns (Roche 1953a, 1953b) and although at Afalou bou Rhummel there is no sign of intentional grave cuts, the fact that two graves were used repeatedly for the deposition of large numbers of bodies (Arambourg et al. 1934, Hachi 2006) points to the existence of markers to advertise their position.

If Ibéromaurusian cemeteries were utilised as a platform for the ideological legitimisation of territorial control through an explicit engagement with the past that did not involve manipulating symbolic dichotomies, it seems possible such claims were made on collective levels, perhaps by lineages and/or residential groups (or on a wider ethnic/clan basis) against other lineages and/or residential groups. This is an argument based on several convergent lines of reasoning. 1.

The cemetery activities represent an explicit engagement with the past through emphasising children and group burial. It may be that these elements focused the participants’ attention on the social associations between individuals; in particular, the children could have emphasised generational linkages, providing a symbolicstructural connection with the past. In this sense, it is difficult to identify the subtlety of manipulations involving ritual dichotomies as argued for Mesolithic Scandinavia, but as Bell (1992, and see Appadurai 1981, Fentress and Wickham 1992) noted, even on a general level the past is both a context for action and a medium for manipulation. Connerton (1989) argued that some forms of social memory are created and maintained by bodily interactions and performances. The interaction between bodies in death, together with the interaction between participants at the funerals, may have provided an explicit engagement with the past as a legitimising force for maintaining control. It is worth quoting H. Williams, who in the context of an examination of AngloSaxon mortuary rites, considered the relationship between social memory (cf. Connerton 1989) and funerary practices:

‘Ritual masters’, as outlined by Bell (1992), and the Ibéromaurusian.

Ritual mastery is the ability – not equally shared, desired or recognised – to take and remake cultural schemes, deploy them in the formulation of a privileged ritual experience, and impress them upon agents able to recreate them in circumstances beyond the circumference of the rite (Bell 1992:116). Bell (1992:130-135) argued the authority of ritual masters was based on the intrinsic importance of ritual as a means of mediating relations between human and non-human powers. When strategies of ritualisation are dominated by a special group recognised as experts, the reality they objectify acts to maintain the authority of the experts themselves. However, correctness of a ritual performance is critical to its effectiveness, and others have the right to pass judgement. Consequently, Bell (1992:134) argued that, “the power to do the ritual correctly resides in the specialist’s officially recognised or appointed status (office), not in the personhood or personality of the specialist.” Thus, while ritual mastery is an unevenly shared ability, a ‘ritual master’ is also a culturally recognised position within the society in question. This does not necessitate the existence of status inequalities but it does imply a level of differentiation of personhood and the recognition of (semi-formalised) identities achieved through ability. Such individuals are ethnographically documented in hunter-gatherer communities (Seligman and Seligman 1911). As the evidence stands, it is debateable as to whether there were (semi-formalised) culturally defined roles in the Ibéromaurusian. On the one hand, there are indications of the deliberate selection of adults for burial at the low MNI sites and a greater focus on children at the cemeteries; and Mariotti et al. (2004) interpreted differences in male and female activities based on skeletal muscle markers at Taforalt. However, these seem based on age and gender, and there is no evidence in the burials for an elaboration of particular (achieved) socially recognised identities. Given the complex relationship between life and death, we cannot take the dead as a direct mirror for the living (Parker-Pearson 1999); but Lubell (2001:131) notes that among the occupation debris, “there is little or no evidence for internal

For many societies, rituals surrounding death, disposal and commemoration can have a particularly poignant role in the way the past is remembered through both inscribing and embodying practices. There might be numerous reasons for this. Funerals connect the past and present because they focus on constructing and mediating relations between the living and the dead. They are also times when emotional and ritualised behaviour is heightened and hence society’s attitudes to the past, myths of origin and cosmologies are more likely to take overt and discursive form. Yet, first and foremost, mortuary practices are rites of passage aimed at transforming the social, cosmological and ontological status of both the dead and the living. In this sense, they need to be considered less as rituals aimed at maintaining the social order and 82

6. Cemeteries and Territoriality in the Ibéromaurusian and Capsian Maghreb boundaries (Cashdan 1983). Again, this is not a context the ethnographic literature suggests would give rise to individual claims (Chapter 2).

community organisation other than the presence of hearths [and] concentrations of debris …” and though there is evidence for adornment (Camps-Fabrer 1960), nothing in its context of discovery suggests anything other than an egalitarian form of display. At present there is no contextual evidence supportive of an argument of ‘ritual masters’ as described by Bell (1992) within the Ibéromaurusian. This does not, however, undermine claims of territoriality: it is a highly variable form of behaviour (Chapter 2) ethnographically documented in hunter-gatherer communities of variable complexity and economic activities (Turner and Jones 2000, Barnard 1992, Cashdan 1983, Turnbull 1968, Grøn et al. 2008, N. M. Williams 1982, Johnson 1988, C. S. Fowler 1982, Dyson-Hudson and Smith 1978). 2.

4.

In Chapter 5 I suggested that a high incidence of trauma to the crania, evidence for weapons embedded in bone and a focus on adult males might indicate warfare. As can be seen in tables 6.77 and 6.81 there is little evidence that would support a comparable interpretation in the Ibéromaurusian Maghreb. There are some signs of close contact violence and violence committed at a distance: at Columnata an adult male (H10/a) was killed by two flint weapons (Chamla et al. 1970) and a second adult male (H33/a) was shot with an arrow (Camps 1974). There are also signs of cranial trauma (Briggs 1955, Ben-Ncer 2004a, Dastugue 1962, 1975), but when considered as a whole there are few persuasive indications of widespread inter-group aggression. Trauma to the head is found in a low proportion of the population (3% or 9/335), and a greater number of individuals (5%, 17/335) exhibit injuries to the body and limbs; weapons are documented but rare (0.6% or 3/335); and the female: male ratio is more balanced (2:3) than seen in Scandinavia. This pattern strongly resembles that identified by Jackes in Mesolithic human remains found at the middens along the Muge River in Portugal. In this region trauma to the crania (2%, 6/282) and evidence for weapons embedded in bone (0.4%, 1/282) is rare and injuries tend to be located on the body and limbs (7%, 19/282). She interpreted these injuries as deriving from childhood accidents, injuries involved in hunting, aggression in a domestic setting and perhaps some activity that placed stress on the elbows and forearms of young males. Unfortunately the material from Ibéromaurusian sites in Morocco and Algeria has not been studied as recently (Arambourg et al. 1934, Camps 1974, Chamla et al. 1970, Dastague 1962, Dastague 1975) but given the similarities in the parts of the body affected by trauma, the percentage of the population afflicted, and the female: male ratio, it is possible a similar situation to that in Portugal may apply. There is, therefore, no skeletal evidence for warfare. Violence tends to be associated with practices of exclusive land use involving defended boundaries (Baker 2003), and although its absence in the Ibéromaurusian may indicate the existence of other ways of expressing and resolving inter-group antagonisms (Turnbull 1968, Radcliffe Brown 1952, Keesing and Strathern 1998), the pathological data nevertheless finds congruence in an interpretation of territorial claims made on a collective level in a context of non-exclusive use.

The nature of the funerary rituals and (possible) collective forms of control.

The funerary rituals at Taforalt (Roche 1953a, b), Columnata (Cadenat 1955, 1957) and Afalou bou Rhummel (Arambourg et al. 1934, Hachi 2006) are dominated by group burials. If an aim of those who oversaw the rituals (the ‘controllers’) was to establish a link with the past and emphasise social relations between the dead and the living (through the physical placement of multiple bodies in the same grave), it seems difficult to understand how individual, rather than collective claims could be made visible to the participants in this context. It remains uncertain as to whether there were explicit, visual linkages of these cemeteries with resources under control. A link was argued for Skateholm in Chapter 5 through a discussion of fish bones discovered in the graves (Jonsson 1988). It is possible the Barbary sheep horns at Taforalt (Roche 1953a, b), for example, provided a link with a hunted resource, but it is difficult to evaluate the importance of this animal at the site as Roche (1963) only published presence/absence lists with regards to the faunal remains. It seems reasonable that reference to contended materials could be made during archaeologically invisible aspects of the rites – perhaps feasting activities involving the resources took place away from the burials – but the funerary emphasis on group interment points in general to collective claims. As an aside, claims made on an individual level (e.g. Turner and Jones 2000) would be more likely in a community in which ritual masters (Bell 1992) were present. 3.

The pathological evidence.

The association of cemeteries and base camps situated in seasonal settlement subsistence systems.

Detailed analyses of the faunal material and isotopic studies of the human bones from cemetery and noncemetery sites would clarify our understanding, but if it the above interpretation of seasonality is reasonable, ethnographic analogies render exclusive control over defined areas demarked by defended boundaries unlikely (Baker 2003). Communities with a degree of mobility (e.g. Dyson-Hudson and Smith 1978, C. S. 1982, N. M. Williams 1982) tend to operate more flexible forms of territorial control with restriction to resources via social

Therefore, there is contextual evidence for territorial control independent of the cemeteries within the Ibéromaurusian, but the nature of those claims fell somewhere along the middle of the ‘territorial behavioural spectrum.’ Claims were collective, made by lineages, residential groups or clans, or some mixture of the three, against other lineages, residential groups or clans, or some mixture of the three. There may have been a mix of social-boundary and spatial perimeter defence 83

Grim Investigations: Reaping the Dead bone made with a sharp object (Briggs 1955). This is a low level and while it may reflect the general good health of the Upper Capsian population, it is also possible there have been too few analyses concerned to identify such features.

(cf. Cashdan 1983) as mechanisms providing access to the resources. Baker (2003:132) identified five points along a spectrum of territoriality (see Chapter 2). The second and third (midway) points were, respectively: geographically stable territories with open access where groups maintain exclusive use of spatial areas but leave some land unclaimed and undefended; and home ranges wherein groups maintained territories but ownership is not exclusive. Based on the nature of the cemeteries and the way I believed they functioned as territorial markers, together with the base camps and the wider evidence for the settlement-subsistence system, I think the Ibéromaurusian communities who interred their dead at Taforalt, Columnata and Afalou bou Rhummel lie somewhere between these two points, perhaps falling closer to the latter. This is intriguing, and would suggest that ‘cemeteries’ are not a feature exclusive to huntergatherer societies who maintain exclusive ownership of geographically stable territories (cf. Baker 2003), but were a form of control utilised in a wide range of contexts. A similar picture may be true for the Capsian.

As with the Ibéromaurusian, there is evidence in the Capsian for cultural symbolisms focused on the head. This is seen in the unusual placement of crania in a single inhumation at Mechta el Arbi (Balout 1954), group inhumations at Aïn Keda (Bayle des Hermens 1955), and secondary inhumations at Site 12 (Haverkort and Lubell 1999). There is evidence for the removal of the head at Site 12 (Haverkort and Lubell 1999) and Daklat es Saâdane (Tixier 1955); the bone scatter type A is dominated by crania (table 6.41); at Mechta el Arbi, Medjez II and Columnata, crania were turned into masks (Balout 1954, Camps-Fabrer 1975); and at Faïd Souar II (Laplace 2004, Vallois 1971) a cranial mask was buried with the body. Practices of dental avulsion at cemetery and non-cemetery sites suggest the importance of the mouth; the presence of certain teeth seems to have been as important as the absence of others, as suggested by the prosthetic tooth found in a cranium at Faïd Souar II (Vallois 1971); and, at Bortal Fakher, a second upper incisor was utilised as an ornament (Gobert 1957). This material, however, presents a marked contrast to the Ibéromaurusian: in the Capsian there is evidence for the deliberate post-mortem manipulation of human bone.

Ibéromaurusian and Capsian funerary rituals are very similar, perhaps reflecting continuity (Lubell et al. 1984). The demography of those in single inhumations (table 6.82), their body position where known (table 6.83), associated grave structures (table 6.84) and the number (table 6.85) and type (table 6.86) of grave goods show no significant differences. The same is true of the parts of the body found as bone scatter type A (table 6.87). There is, however, one obvious dissimilarity (table 6.88) that remains true if we compare only the low (table 6.89) and high (table 6.90) MNI sites: the contexts from which human bones were recovered. The Ibéromaurusian – as a result of the cemeteries – is dominated by group burial, whereas single inhumation is more common during the Capsian and intentional modification of human bone known. The Capsian, therefore, not only marked a shift inland and a reorganisation of subsistence practices (Lubell et al. 1984) but possibly also a transformation in the understanding of identity. There are also hints that the method – if not the nature – of territorial legitimisation changed, too.

Skulls and long bones were utilised at high and low MNI sites (Camps-Fabrer 1960, 1975, Pond et al. 1938, Balout 1954, Gobert 1957, Vallois 1971) in the production of material culture (tables 6.41, 6.53 and 6.94). There is an even split between the crania and the long bones, and it is interesting that various parts of the body were treated differently. The former were rubbed with ochre and transformed into masks; the latter were shaped into ‘tools’. Although it would be facile to distinguish between ‘symbolic’ and ‘functional’ uses of different objects, it is possible they transformed the living body in alternative ways (C. Fowler 2004). Masks disembody the embodied soul and through obscuring the face alter a person’s agency (as deriving not just from the living but also ‘deceased’ sources of knowledge, power and capacity). By contrast, the tools (Dobres and Robb 2000) are a more subtle mediator of identity as they extend a persons agency, rather than substantially altering it. If we compare them further it can be seen that while both masks and tools were made from human remains, the latter were treated in a manner analogous to faunal material while the former were not. Fabricators were made on animal bones (Camps-Fabrer 1960) and it is conceivable those made on human material (Pond et al. 1938, Camps-Fabrer 1975) were produced by individuals skilled in working the former and used in similar contexts. In this sense, they possessed the capacity to ritualise contexts normally associated with non-ritual activities through blurring the distinction between ‘humans’ and ‘animals’. By contrast, there are no known examples of masks made from animal skulls. Pond et al. (1938:123) commented that these objects were found in

With regards to the Capsian, it is more difficult to identify differences between the high and low MNI sites other than in the number of persons present (table 6.91). The demography of individuals differed at each of the high MNI locales (Haverkort and Lubell 1999, Bayle des Hermens 1955, Balout 1954, Camps-Fabrer 1975, Roch and Roch 1963) but, generally, there is no significant contrast between cemetery and non-cemetery sites (table 6.92) as adults tend to be more common than children at both. This is true of the children’s age structure (table 6.93), and of the evidence for pathology (table 6.77). Two individuals at low MNI sites (an adult male at Aïn Misteheyia and an adult female at Faïd Souar II) exhibit dental caries (Meiklejohn et al. 1979, Vallois 1971); while at Mechta el Arbi (Balout 1954) a six year old child (1927/I) shows evidence for brachycephaly, two individuals (1927/II, 1927/III) suffered from abscesses, and an adult male (1912/III) exhibits a hole in the parietal 84

6. Cemeteries and Territoriality in the Ibéromaurusian and Capsian Maghreb (Camps 1974, Lubell 2001, Merzoug and Sari 2008, Balout and Briggs 1949, Lubell 2004a, 2004b); but based on the available literature, there is no evidence in the Capsian for geographically stable regimes wherein land use is exclusive and spatial boundaries defended (Baker 2003), the context where we would expect to find evidence for both ‘ritual masters’ (Bell 1992) and claims made at an individual level (e.g. Turner and Jones 2000, C. S. Fowler 1982, Gottesfeld 1994, Dyson-Hudson and Smith 1978). Indeed, there is little evidence for pathology in the Capsian, and almost no evidence for violence (Haverkort and Lubell 1999, Bayle des Hermens 1955, Balout 1954, Camps-Fabrer 1975, Roch and Roch 1963) and, again, while this does not mean alternative mechanisms were not utilised in the mediation of inter(and intra-) group antagonisms, it fits a picture of territoriality similar to that defined for the Ibéromaurusian, as something close to the mid-point of Baker’s (2003) spectrum: home ranges in which groups maintained territories (of controlled resources) but ownership was not exclusive and access was through a mixture of spatial perimeter and social boundary defence (Cashdan 1983), perhaps with a tendency towards the latter.

deposits identical to those made on animal bone, an observation echoed by later discoveries (e.g. CampsFabrer 1975). There is, however, no recognisable difference in this material at the high and low MNI sites. Crania dominate the bone scatter type A at both low (60%) and high (75%) MNI sites (table 6.94). Grave goods interred with the deceased are similar at cemetery and non-cemetery sites: the average number tends to be low (0.52 and 0.91 respectively; table 6.95) with a similar degree of variation in which ochre was the most common. There is no evidence for an association by sex, although they were found more often with adults than children. Of the inhumations, there is no significant difference in demography. There is, however, a hint of a difference in the sex ratios as while females and males are equally likely to be found at the cemeteries, males are twice as common as females at the non-cemetery sites. Furthermore, there is a significant difference in the contexts from which human remains were recovered (table 6.96). Group inhumations are absent at noncemetery locales; by contrast, they are present at cemeteries. Furthermore, only 36% of individuals were placed in a burial at the former whereas 55% of those at the latter were interred. However, this percentage may have been much higher as the number of individuals at Mechta el Arbi (Balout 1954) described in the database as inhumations erred on the side of caution. We know that secondary activities took place at the low MNI sites (Laplace 2004, Tixier 1955); but we have yet to find evidence for secondary burial of deliberately reduced cadavers in the ground. If we compare only inhumations, the non-cemetery locales suggest the rite involved the placement of fleshed cadavers in single graves; by contrast, at cemeteries there was variation in who was interred and how (primary/secondary; single/group). This is in part (as discussed above) a reflection of the variable and individual character of the cemeteries.

As to who the ‘controllers’ and ‘controlled’ were, it is difficult to speculate. Individual primary and secondary burials are documented at all cemeteries (Balout 1954, Haverkort and Lubell 1999, Roch and Roch 1963, Camps-Fabrer 1975) except Aïn Keda (Bayle des Hermens 1955). The potential for individual control through the linkage of interred persons with resources existed; there is evidence, for example, at Medjez II (Camps-Fabrer 1975), for the placement of faunal remains in graves. However, territorial claims made by an individual tend to be documented ethnographically in communities (e.g. Turner and Jones 2000) that are sedentary, or semi-sedentary; that show evidence for formalised identities by ability, as well by as age and gender, and perhaps even status differentiation; they tend to utilise spatial boundary forms of defence; and they usually exhibit exclusive control and concepts of ownership (Cashdan 1983, Dyson-Hudson and Smith, Baker, Sack 1986). This picture is not supported by the Capsian evidence. The nature of the burials as ‘individual’ is too tangential an argument alone to repudiate and invalidate the alternative interpretation – collective forms of control – which is based on a wider synthesis of information from burial and habitation contexts. Though speculative, it seems possible that Capsian cemeteries were utilised as platforms for the legitimisation of claims made by, for examples, lineages, residential groups and/or clans.

Given the overwhelming similarity of the high and low MNI sites, it is possible that – as in the Ibéromaurusian – symbolic dichotomies were not manipulated at Capsian cemeteries in the (re)construction of a world order legitimising territorial claims (cf. Bell 1992). There is no evidence in the burials for differentiation in social identities and, although the dead are not a direct mirror for the living (Parker Pearson 1999), there is no evidence from the occupation debris for internal community organisation (Camps 1974, Lubell 2001), and nothing in the context from which items of adornment were recovered (Camps-Fabrer 1960) to suggest anything other than egalitarian relationships with identities based on age and gender. This is not a context in which we would expect to see ‘ritual masters’ (cf. Bell 1992). The evidence for the settlement-subsistence system points to a pattern of seasonal movement (see above), and this is supported by the archaeological debris contained within sites interpreted as base camps, which tend to lack any evidence for structures (energy investment) other than burials and hearths (Pond et al. 1938, Balout 1958, Camps 1974, Lubell 2001). As discussed above, the Capsian economy differed to that of the Ibéromaurusian

It is not clear how burials were advertised in the periods between funerary rituals. Although some cemeteries are described as lacking grave structures (Haverkort and Lubell 1999, Bayle des Hermens 1955), one of the burials (group 2) at Aïn Keda was surrounded by four large stones (Bayle des Hermens 1955), and stones surrounded an interment at Medjez II (Camps-Fabrer 1975). Similarly, a burial at Aïn Dokkara (Balout 1958) was 85

Grim Investigations: Reaping the Dead According to Sack’s (1986) theory territories do not need to be physically defended and the controllers do not need to be present within the territory or, indeed, anywhere near it to exert their control so long as their claim is communicated in a recognisable manner; fences, walls, no trespass signs – or any other widely understood marker – are sufficient. The placement of burials in the midden deposits would have articulated a direct relationship between the group territorialising its claims and the resources under control through depositing the remains of the dead directly in the remains of that which gave the community life. Although there is no evidence for subtle manipulations of symbolic dichotomies (Bell 1992), it is possible that, as in the Ibéromaurusian, a direct and explicit engagement with the past through bodily performances in the creation of social memory continued to form the main mechanism (Appadurai 1981, Fentress and Wickham 1992, Connerton 1989) for (re)creating the world order to ideologically legitimise claims. The combination of midden and grave marker could have communicated this to out-group members.